Abstract

Background

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) provides public reporting on the quality of hospital care for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). CMS Core Measures allow discretion in excluding patients because of relative contraindications to aspirin, beta-blockers and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. We describe trends in the proportion of AMI patients with contraindications that could lead to discretionary exclusion from public reporting.

Methods

We completed cross-sectional analyses of three nationally-representative data cohorts of AMI admissions among Medicare patients in 1994–5 (n=170,928), 1998–9 (n=27,432), and 2000–2001 (n=27,300) from the national Medicare quality improvement projects. Patients were categorized as ineligible (e.g. transfer patients), automatically excluded (specified absolute medical contraindications), discretionarily excluded (potentially excluded based on relative contraindications), or ‘ideal’ for treatment for each measure.

Results

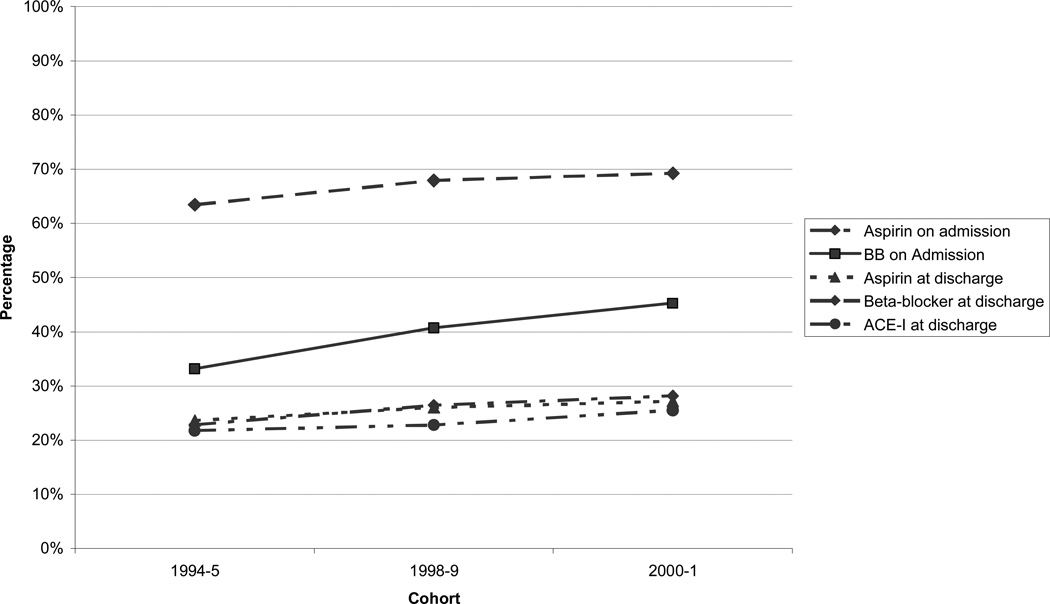

For 4 of 5 measures the percentage of discretionarily excluded patients increased over the three time periods (admission aspirin 15.8% to 16.9% and admission beta-blocker 14.3% to 18.3%, discharge aspirin 10.3% to 12.3%, and ACE-I 2.8% to 3.9%, p<.001). Of patients potentially included in measures (those who were not ineligible or automatically excluded), the discretionarily excluded represented 25.5 % to 69.2% in 2000–01. Treatment rates among patients with discretionary exclusions also increased for 4 of 5 measures (all except ACE-I).

Conclusions

A sizeable and growing proportion of AMI patients have relative contraindications to treatments that may result in discretionary exclusion from publicly-reported quality measures. These patients represent a large population for which there is insufficient evidence as to whether measure exclusion or inclusion and treatment represents best care.

Background

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in collaboration with the Hospital Quality Alliance, collects and disseminates quality measures for over 4000 US hospitals as a part of required reporting by hospitals for payment updates.1–3 Through use of the Hospital Compare Web site, which provides public access to CMS Core Measures data, one may judge an individual hospital’s performance on numerous quality metrics or directly compare institutions. Reported rates of compliance with the processes of care measured by CMS have improved over the past several years coinciding with public reporting of the measures.4–6 Furthermore, given the continued and growing interest of payers and policymakers in linking healthcare payment to measures of quality, performance on Core Measures will likely become ever more critical to hospitals.7

Many Core Measures do not, however, assess care for all patients. Measures of processes of care for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), including the use of aspirin and beta-blockers at admission and at discharge and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for patients with low left ventricular systolic function, allow physicians considerable discretion in excluding patients from reported metrics in order to account for potential contraindications to measured treatments.8 Prior work has shown that the overall prevalence of contraindications to AMI treatments is substantial and increasing over time.6, 9 However, the only patients uniformly excluded from process of care measures are those with specified absolute contraindications to AMI treatments (e.g. medication allergies). Most potential contraindications do not lead to automatic exclusion from a measure; instead process of care measures allow for individualized discretionary exclusions based on documentation of the medical team’s decision not to give the treatment, such as not giving a beta-blocker to an AMI patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.8 Differential use of these discretionary exclusions across hospitals may undermine the utility of these metrics for comparing quality of care across institutions. Despite this concern, the prevalence and trends in the proportion of patients with relative contraindications resulting in discretionary exclusion has not been characterized, because prior studies have not differentiated between the absolute contraindications that automatically result in exclusion versus the relative contraindications that may result in discretionary exclusions.

In order to assess the extent to which rates of relative contraindications and their resultant discretionary exclusions may affect interpretation of quality metrics, we determined trends in the proportion of patients with AMI in several time periods between 1994–2001 with characteristics that would lead to their inclusion, or potential exclusion from current publicly-reported quality measures, as well as trends in the treatment of these patients. Using chart-review data from three national Medicare quality improvement projects, we sought to describe trends in the proportion of Medicare patients presenting with AMI with a) specific exclusions to a given drug therapy (“automatic exclusions” group) b) those with relative medical contraindications (“discretionary exclusions” group), and c) those with no contraindications (“ideal candidates”), and to describe trends in the rates of treatment for each of these groups.

Methods

Data Source and Study Sample

The data for this study were from three Centers for Medicaid and Medicaid Services (CMS) quality improvement projects. The first, the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project (CCP), collected chart-reviewed data on all fee-for-service Medicare patients admitted with a diagnosis of AMI (based on ICD-9 codes) between February 1994 and July 1995 (n=234796).10 The subsequent projects, the National Heart Care Project (NHC) and National Heart Care Remeasurement (NHC-R) collected data from April 1998 – March 1999 and October 2000 – June 2001 respectively. For the NHC and NHC-R, a systematic sample from each state based on age, race and hospital was used to obtain up to 850 representative discharges for AMI per state (n=35,713 for NHC and 35,407 for NHC-R). Details of these studies have been reported elsewhere.10–15

Patient characteristics and performance measurement were obtained from medical records reviewed by trained data abstractors using standardized software, with data quality assessed via random record review. Variable definitions relevant to this analysis were consistent across the three studies. All charts had the same data fields abstracted regardless of treatment decisions. The abstractors had high level of agreement on abstracted data.11

Patients with AMI were identified based on principal discharge ICD-9 codes for AMI (410.X0 or 410.x1). In each of the AMI quality improvement projects, the diagnosis of myocardial infarction was confirmed using a combination of laboratory and electrocardiographic data. We excluded patients whose AMI was not confirmed (31186 (13.3%) for CCP, 4255 (11.9%) for NHC, 3647 (10.3%) for NHC-R), patients less than 65 years old (17593 (7.5%) for CCP, 3009 (8.4%) for NHC, 3038 (8.5%) for NHC-R), and later AMI admissions for the same patient within the time period of data collection (27498 (11.7%) for CCP, 2125 (6.0%) for NHC, 2068 (5.8%) for NHC-R), as well as those patients for whom vital status or correct state code was undetermined (4 for CCP, 21 for NHC, 423 (1.2%) for NHC-R). 50,229 patients met one or more of the above criteria, leaving a final cohort of 255,660 patients (170,928 from CCP, 27,432 from NHC, and 27,300 from NHC-R).

Definition of candidacy for Performance Measures

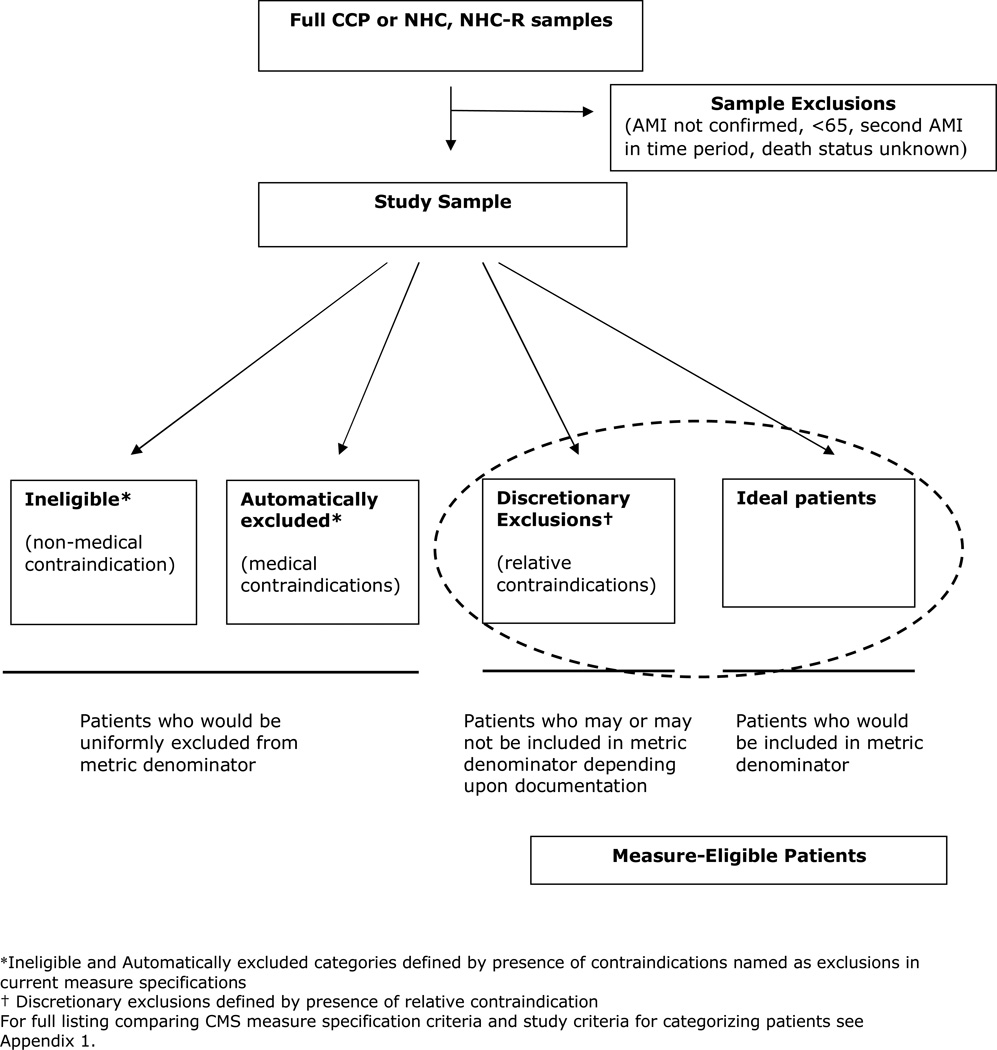

We examined trends for 5 AMI quality measures: use of aspirin at admission, use of beta-blocker at admission, prescription of ACE-I at discharge for patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, prescription of aspirin at discharge, and prescription of beta-blocker at discharge. Drawing from the current CMS/Joint Commission (CMS/JC) quality measure definitions, patients were categorized as ineligible, automatic exclusions, discretionary exclusions, or ideal candidates for treatment (See Figure 1), although these measures were not publicly reported at the time of initial data collection. We defined ineligible patients (our terminology) as cases who would be ineligible and therefore excluded from current measures for non-medical reasons that either preclude assessment of quality of care or appropriate assignation of the responsible hospital, such being transferred out on the day of admission. Patients were categorized as automatic exclusions for a quality measure if they had a medical contraindication (i.e. medication allergy) for the therapy as defined by current CMS/JC measure specifications. Patients categorized as ineligible or automatically excluded are those who would uniformly be left out of the denominator in calculating rates of treatment for publicly reported data.

Figure 1.

Schematic of Sample and Patient Categories

We defined the discretionary exclusions group as those patients who may or may not be included in quality measures under current specifications, due to relative contraindications to treatment. To identify potential contraindications to categorize this group we compiled a list of the relative contraindications used by CMS prior to the current public reporting era.16 These are patients who could be excluded from a measure based on the CMS criteria allowing any patient to be excluded from a measure for "other reasons documented by a physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant for not prescribing" the given treatment. (A complete list of comparing current CMS/JC measure specifications and the criteria used to categorize patients for this study can be found in Appendix Table 1). Finally, patients who did not fit into any of the above categories were considered ideal candidates for therapy (no contraindications).

Outcome variables

Treatment with measured processes of care was based on chart-reviewed data from each of the cohorts.

Statistical Analysis

We compared the clinical characteristics of patients from each of the three cohorts and then determined the distribution of patients classified as excluded, ineligible, discretionary, or ideal candidates for each of the five quality indicators. We also calculated the number of patients ideal for 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 of the drug therapies for each cohort.

We compared rates of use of medical therapies for patients in the excluded, discretionary, and ideal group. Patients classified as ineligible were not assessed because their exclusion from process of care measures is most often related to logistics of their admission and not medical reasons to withhold a particular therapy.

All comparisons between groups were done using survey data analysis methods with chi-squares test in cross table analyses for dichotomous variables and F-test in ANOVA model analyses for continuous variables. All analyses were done with SAS Version 9.1 (SAS institute, Inc. Cary, NC). Analysis of the CCP, NHC, and NHC-R databases was approved by the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee. Dr. Bernheim was supported by a training grant from the National Institute on Aging (T32AG1934) when initially working on this study. Saif Rathore is supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality dissertation grant (1R36HS018283-01). The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses and drafting and editing of the paper.

Results

Characteristics of study samples

The mean age of the 3 cohorts increased significantly over time, ranging from 76.3 years (1994–1995 cohort) to 78.0 years (2000–2001 cohort, p<0.001). Each cohort had high rates of comorbidities with significant increases over time, including hypertension, prior heart failure, and previous cardiac interventions. By contrast, measures of clinical severity at admission, such as rates of ST-segment elevation MI, cardiac arrest, shock, and pulmonary edema at admission, decreased over time (Table I).

Table I.

Patient Characteristics and Outcomes* by Time Period

| Description | 1994–1995 | 1998–1999 | 2000–2001 | Overall P |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | ||

| All | 170928 | 100.00 | 27432 | 100.00 | 27300 | 100.00 | |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age: mean (SD) | 76.30 | 7.34 | 77.40 | 16.83 | 77.99 | 18.25 | <0.001 |

| Female | 82741 | 48.41 | 13446 | 50.31 | 13470 | 50.17 | <0.001 |

| Non-white | 16529 | 9.67 | 4103 | 13.54 | 4591 | 14.84 | <0.001 |

| Medical history | |||||||

| Prior MI | 49477 | 28.95 | 9436 | 35.04 | 9947 | 37.17 | <0.001 |

| Prior HF | 35603 | 20.83 | 7125 | 27.55 | 7975 | 30.98 | <0.001 |

| Prior PTCA | 11564 | 6.77 | 3204 | 11.48 | 3756 | 14.14 | <0.001 |

| Prior CABG | 21254 | 12.43 | 4418 | 16.63 | 4691 | 17.66 | <0.001 |

| Prior CVA | 23612 | 13.81 | 4625 | 17.32 | 5152 | 19.56 | <0.001 |

| COPD | 34756 | 20.33 | 6097 | 22.85 | 6609 | 24.62 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 52167 | 30.52 | 8704 | 32.58 | 9112 | 34.38 | <0.001 |

| Clinical Presentation | |||||||

| Shock | 4364 | 2.55 | 513 | 1.81 | 313 | 1.15 | <0.001 |

| Hemorrhage | 5251 | 3.07 | 1030 | 3.85 | 1051 | 4.11 | <0.001 |

| CHF/Pulmonary edema | 48025 | 28.10 | 6136 | 23.71 | 5563 | 21.84 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate: mean (SD) | 87.43 | 24.50 | 88.57 | 54.38 | 88.70 | 58.15 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure: mean (SD) | 143.55 | 32.76 | 142.78 | 71.78 | 141.97 | 76.63 | <0.001 |

| Respiratory rate: mean (SD) | 22.23 | 6.58 | 22.06 | 14.16 | 21.85 | 14.95 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine: mean (SD) | 1.38 | 0.96 | 1.45 | 4.02 | 1.49 | 2.62 | <0.001 |

| ST-elevation | 54608 | 31.95 | 8412 | 30.15 | 6905 | 24.47 | <0.001 |

| Assessment of LVEF | |||||||

| Without the measure | 60845 | 35.60 | 9017 | 30.69 | 7989 | 27.69 | <0.001 |

| With the measure | <0.001 | ||||||

| Normal | 46667 | 42.39 | 7914 | 41.37 | 8494 | 42.04 | |

| Mild/mild moderate/decreased | 27517 | 25.00 | 4327 | 23.62 | 4476 | 23.73 | |

| Moderate/moderate severe/low | 20438 | 18.57 | 3325 | 18.78 | 3372 | 17.79 | |

| Severe/very severe/very low/poor | 15461 | 14.04 | 2849 | 16.24 | 2969 | 16.44 | |

| Outcomes | |||||||

| Length of stay: mean (SD.) | 8.36 | 7.22 | 7.24 | 13.90 | 7.11 | 15.15 | <0.001 |

| 30-Day mortality from discharge | 8843 | 5.17 | 1733 | 6.46 | 1756 | 6.73 | <0.001 |

| One-year mortality from discharge | 29782 | 17.42 | 5524 | 20.75 | 5688 | 22.19 | <0.001 |

Results from survey analysis for % and P value are shown here.

Trends in candidacy for drug-therapy

A large proportion of the patients in all three cohorts were ineligible for inclusion for each of the five quality of care measures (Table II). For admission use of aspirin and beta-blocker, 20–33% were ineligible, largely because they were transferred in or out, discharged on the day of admission, or died. Up to 85% of patients were ineligible for treatment with ACE-I because their left ventricular systolic function was not assessed or measured as greater than 40% ejection fraction. The proportion of ineligible candidates increased significantly over time for the admission measures (20% in 1994–5, 28% in 2000–1), while it decreased slightly for the discharge measures.

Table II.

Performance Measures by Time Period

| Description | 1994–1995 | 1998–1999 | 2000–2001 | Overall P |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | ||

| All | 170928 | 100.00 | 27432 | 100.00 | 27300 | 100.00 | |

| Medication on admission | |||||||

| Aspirin | <0.001 | ||||||

| Ineligible | 34441 | 20.15 | 7458 | 25.97 | 8190 | 27.75 | |

| Excluded | 18540 | 10.85 | 3327 | 12.55 | 3290 | 12.73 | |

| Discretionary | 26964 | 15.78 | 4402 | 16.49 | 4457 | 16.94 | |

| Ideal | 90983 | 53.23 | 12245 | 44.98 | 11363 | 42.58 | |

| BB | <0.001 | ||||||

| Ineligible | 34441 | 20.15 | 7458 | 25.97 | 8190 | 27.75 | |

| Excluded | 62620 | 36.64 | 9318 | 35.19 | 8584 | 33.03 | |

| Discretionary | 24518 | 14.34 | 4339 | 16.06 | 4764 | 18.31 | |

| Ideal | 49349 | 28.87 | 6317 | 22.78 | 5762 | 20.91 | |

| Medication at discharge | |||||||

| Aspirin | <0.001 | ||||||

| Ineligible | 56570 | 33.10 | 8645 | 31.51 | 8640 | 31.81 | |

| Excluded | 39558 | 23.14 | 6301 | 22.82 | 6486 | 23.72 | |

| Discretionary | 17669 | 10.34 | 3248 | 11.97 | 3306 | 12.25 | |

| Ideal | 57131 | 33.42 | 9238 | 33.71 | 8868 | 32.22 | |

| BB | <0.001 | ||||||

| Ineligible | 56570 | 33.10 | 8645 | 31.51 | 8640 | 31.81 | |

| Excluded | 46298 | 27.09 | 8906 | 31.87 | 9860 | 35.34 | |

| Discretionary | 43167 | 25.25 | 6710 | 25.06 | 6092 | 22.88 | |

| Ideal | 24893 | 14.56 | 3171 | 11.56 | 2708 | 9.97 | |

| ACEI | <0.001 | ||||||

| Ineligible | 146212 | 85.54 | 23098 | 82.97 | 22778 | 82.68 | |

| Excluded | 2535 | 1.48 | 456 | 1.95 | 473 | 1.71 | |

| Discretionary | 4824 | 2.82 | 883 | 3.44 | 1032 | 3.93 | |

| Ideal | 17357 | 10.15 | 2995 | 11.64 | 3017 | 11.68 | |

Results from survey analysis for % and P value are shown here.

The proportion of patients with medical contraindications that would lead to automatic exclusion from the measures also increased slightly for most measures from 1994–5 to 2000–1, with the largest increase for the measure of beta-blocker at discharge (27% vs. 35%) and a slight decrease for beta-blocker at admission.

In the 2000–01 cohort, 41% of patients (admission aspirin) to 85% (ACE-I) would be uniformly excluded from any given measure denominator because they were either ineligible or had a medical contraindication leading to automatic exclusion. The proportion of patients that were either ineligible or had an automatic exclusion significantly increased for three of five measures over time, aspirin at admission (30.9% either ineligible or excluded for aspirin in 1994–95 vs. 40.5% in 2000–2001), beta-blocker at admission (56.7% 1994–1995 vs. 60.8% in 2000–2001) and beta-blocker at discharge (60.2% 1994–95 vs. 67.1% 2000–2001).

For all measures, except beta-blocker at discharge, the proportion of patients in the discretionary group, i.e., those with relative contraindications that are not automatic exclusions but which could lead to an individualized discretionary exclusion, increased significantly over time. The proportion of candidates in the discretionary group for aspirin on admission increased from 15.8% in 1994–1995 to 16.9% in 2000–2001. For beta-blocker on admission, the increase was greater (14.3% in 1994–1995, 18.3% in 2000–2001.) Moreover, when the proportion of patients that could be discretionarily excluded was calculated as a proportion of measure-eligible patients, i.e., patients who are not automatically excluded or ineligible, the patients with potential discretionary exclusions represented 25.5% of eligible patients for ACE-I, and 69.2% for discharge beta-blocker in 2000–2001. The percentage of discretionary exclusion patients among measure-eligible patients increased over time for all measures.

The combined increases in ineligible, automatically excluded and discretionary patients led to a decrease in the proportion of ideal candidates for each measure except ACE-I at discharge. In turn, the proportion of patients who are ideal for no measures (ineligible, excluded or discretionary for all groups) increased from 29.8% in 1994–5 to 37.1% in 2000–2001, and the proportion of patients who were ideal for all measures was less than 1% in all cohorts. (Table III)

Table III.

Number of Ideal Performance Measures by Time Period

| Description | 1994–1995 | 1998–1999 | 2000–2001 | Overall P |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | ||

| N (%) | 170928 | 100.00 | 27432 | 100.00 | 27300 | 100.00 | |

| Number of Ideal Performance Measures | <0.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 50891 | 29.77 | 9772 | 35.35 | 10284 | 37.08 | |

| 1 | 43242 | 25.30 | 6828 | 24.98 | 7112 | 26.42 | |

| 2 | 45683 | 26.73 | 6663 | 23.99 | 6176 | 22.69 | |

| 3 | 19934 | 11.66 | 2933 | 11.24 | 2701 | 9.87 | |

| 4 | 10587 | 6.19 | 1167 | 4.20 | 984 | 3.77 | |

| 5 | 591 | 0.35 | 69 | 0.23 | 43 | 0.17 | |

Results from survey analysis for % and P value are shown here.

Trends in Drug Therapy

Use of all five drug therapies increased for automatically excluded, discretionary and ideal candidates, except for ACE-I use in automatically excluded and discretionary patients (Table IV) The use of aspirin and beta-blocker at admission and discharge was substantial and increased significantly for both automatically excluded and discretionary patients, that is to say, patients with potential medical contraindications to treatment. For example, admission use of aspirin went from 83% to 89% (p<0.001) among the discretionary patients and 60% to 73% use among excluded patients. Beta-blocker use at discharge among patients excluded from measures and among discretionary patients increased dramatically over this time period (excluded 40% in 1994–5 to 71% in 2000–2001, discretionary: 26% to 61%).

Table IV.

Use of Medications Among the Corresponding Performance Measures by Time Period

| Description | 1994–1995 | 1998–1999 | 2000–2001 | Overall P |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | ||

| Medication on admission or during hospital | |||||||

| Aspirin | 140774 | 82.36 | 24338 | 88.09 | 24429 | 88.81 | <0.001 |

| Excluded | 11169 | 60.24 | 2385 | 70.97 | 2434 | 72.79 | <0.001 |

| Discretionary | 22252 | 82.52 | 3992 | 90.23 | 4033 | 89.21 | <0.001 |

| Ideal | 80961 | 88.98 | 11593 | 94.20 | 10793 | 94.66 | <0.001 |

| BB | 84353 | 49.35 | 18337 | 66.81 | 20993 | 77.41 | <0.001 |

| Excluded | 25331 | 40.45 | 5582 | 59.74 | 6397 | 74.77 | <0.001 |

| Discretionary | 11127 | 45.38 | 2844 | 65.57 | 3581 | 75.70 | <0.001 |

| Ideal | 32535 | 65.93 | 5212 | 82.97 | 5067 | 88.24 | <0.001 |

| Medication at discharge | |||||||

| Aspirin | 87200 | 51.02 | 16569 | 58.86 | 17316 | 61.16 | <0.001 |

| Excluded | 20931 | 52.91 | 3870 | 58.48 | 4267 | 63.10 | <0.001 |

| Discretionary | 11946 | 67.61 | 2509 | 74.49 | 2612 | 76.78 | <0.001 |

| Ideal | 43627 | 76.36 | 7748 | 83.13 | 7625 | 84.42 | <0.001 |

| BB | 49345 | 28.87 | 12638 | 45.93 | 15383 | 55.75 | <0.001 |

| Excluded | 18555 | 40.08 | 5390 | 60.73 | 7014 | 71.19 | <0.001 |

| Discretionary | 11382 | 26.37 | 3061 | 45.66 | 3702 | 60.62 | <0.001 |

| Ideal | 12503 | 50.23 | 2267 | 71.18 | 2157 | 78.87 | <0.001 |

| ACEI | 43298 | 25.33 | 9617 | 34.93 | 10815 | 38.97 | <0.001 |

| Excluded | 1279 | 50.45 | 238 | 51.00 | 227 | 47.77 | 0.695 |

| Discretionary | 1886 | 39.10 | 371 | 39.49 | 387 | 35.87 | 0.260 |

| Ideal | 10761 | 62.00 | 2092 | 70.07 | 2213 | 71.48 | <0.001 |

Results from survey analysis for % and P value are shown here.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that an increasing proportion of older patients with AMI have medical conditions that could lead to their exclusion from publicly-reported process of care measures. Indeed, of the patients that could be included in a given quality measure (that is, of those that are not uniformly excluded) up to 69% were in the discretionary category based on chart-abstracted data in 2000–01; they did not have a specified contraindication that would automatically lead to their exclusion from the measure, nor were they ideal for the given treatment. We found, additionally, that rates of treatment with medications for which these patients had potential contraindications also increased. These results highlight the uncertainties surrounding the best care for older patients with relative contraindications to treatment: it is unclear whether inclusion and treatment or discretionary exclusion represents the better care.

Our results build upon prior work that described the growing proportion of older AMI patients with coexisting conditions and potential contraindications to treatment for AMI.6, 9 A study by Masoudi et. al. indicated, for example, that the proportion of patients ideal for aspirin at admission dropped from 67% to 47% over 10 years, with similar drops found for other measured drug therapies. In our study, less than 1% of Medicare patients were ideal candidates for all 5 process of care measures in 2001, which is to say that for nearly every Medicare beneficiary presenting with an AMI, a complex decision has to be made about whether to provide at least one standard medical treatment.

These findings echo concerns about the evidence-base for current quality measures for older patient groups.17, 18 Although the CMS process measures for AMI are based upon substantial clinical evidence, older and sicker patients are rarely included in clinical trials that established standards of care. A number of observational studies have supported the use of aspirin, beta-blocker and ACE-I in older patient populations,19–21 but these generally have also excluded patients with potential contraindications to care. Without the inclusion of such patients in treatment studies it is difficult to judge what treatment decisions are in the patients’ best interest, thus leaving clinicians with challenging medical decisions.

Our findings also raise questions about how best to account for patients with relative contraindications when measuring quality of care. An earlier approach delineated a comprehensive list of potential contraindications for each therapy and excluded all such patients, whether or not they received treatment.9 In more recent efforts, CMS and the Joint Commission, recognizing the potential overriding benefit of treatment for many patients with relative contraindications, now specify a much narrower set of absolute exclusion criteria. This approach supports more individualized decision-making about care, but the allowance for discretionary exclusions complicates interpretation of publicly reported data. First, the use of discretionary exclusions are invisible to the health care consumer, so the public can not discern to what extent the quality measures are representative of the full population of patients seen at the hospital. Second, use of discretionary exclusions may vary greatly between hospitals and thus limit the comparability of measures. Furthermore, the combined factors of 1) discretion about whether to include patients with contraindications and 2) the lack of evidence about what is best for such patients create a situation that may give hospitals an incentive to treat patients despite relative contraindications, and thus hospitals could seemingly receive credit for care whether or not it is in the patient’s best interest. Indeed, we found rates of treatment for patients with potential contraindications have increased over time.

Finally, the exclusion of large numbers of patients from quality indicators raises broader questions about quality measurement. If a substantial proportion of patients are not represented in quality measures, because they are excluded or ineligible, we cannot provide any definitive assurances regarding the care they receive. This is particularly disconcerting because exclusion and ineligibility for process of care measures cluster in older, sicker patients who are more medically vulnerable and are being missed by quality of care measurement. This also has implications for our ability to ascertain quality at institutions when a notable proportion of patients, typically a sicker cohort, are not included in their overall assessment of quality.

There are a number of potential implications of our work. The first, as described, is the need for more evidence upon which to base treatment decisions for older patient groups with multiple coexisting conditions. Second, quality reporting for older patients may be improved by reporting outcomes or quality of life, as opposed to processes of care. Clinical outcomes could include all patients after risk-adjustment for clinical differences between populations and may be more meaningful to patients. Finally, more detailed information on the portion and characteristics of included patients should be reported for currently reported process measures.

A number of factors must be taken into consideration when interpreting of our work. First, we examined older data and cannot determine what course the observed trends in treatment have taken in more recent years. However, these data permitted detailed analysis of coexisting illnesses and treatment. We know of no other nationally representative source of chart-review data on AMI care. Second, we cannot be sure that all of the increases in discretionary exclusions are due to changes in the AMI population; it is possible that some of these changes represent changes in documentation. However, data collection was done prior to the era of public reporting and we know of no national effort to better document relative contraindications to care at that time. Third, our study is based on applying current measure criteria to patient populations prior to the era of public reporting. Thus, although we illuminate important changes in the populations of AMI patients that could be excluded from the measures, we do not know how this would translate into actual practice. The goal of this work was to highlight the growing population of AMI patients that could be excluded and the lack of transparency around these exclusions. Finally, our categorizations of patients were based on variables selected for prior quality improvement projects and do not precisely match current CMS/Joint Commission criteria. However, it is unlikely that this would dramatically change the trends described.

Important progress has been made in the last decade toward making care provided by hospitals to AMI patients more transparent. Most indications suggest that there has been simultaneous improvement in the quality of care provided to AMI patients. Our work identifies ongoing challenges with performance measurement in this population by revealing potential limitations of process measurements that incorporate discretionary exclusion of patients. Despite allowing for patient-specific decision-making, discretionary exclusion may lead to variability in patient populations included in measures across hospitals. Public quality reports, by failing to indicate who is excluded from measures, do not reflect the care provided to a large group of older patients whose inclusion or discretionary exclusion is invisible to the healthcare consumer.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients with discretionary exclusions among measure eligible patients

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

Comparison of CMS measure specification with study cohort specifications for patients identified as ineligible, excluded or discretionary

| CMS MEASURE SPECIFICATIONS | STUDY COHORT SPECIFICATIONS |

|---|---|

| ADMISSION MEASURES | |

| Excluded for all admission measures | Ineligible for all Admission Measures |

| <18 years of age | [Cohort includes >65 y.o only] |

| Patient transferred to another acute care hospital or federal hospital on day of or day after arrival | Transferred out on the day or the day after admission |

| Patient discharged on day of arrival | Discharged on the day or the day after admission |

| Patient expired on day of or day after arrival | Expired on the day or the day after admission |

| Patients who left AMA on day of or day after arrival | Left AMA on day of or day after admission |

| Patients with comfort measures only documented by a physician, APRN or PA | Patients with terminal illness |

| Patients received in transfer from another hospital or ER | Patient received in transfer or admission source unknown |

| ASPIRIN ON ADMISSION | |

| Additional exclusions for ASA on admit | Absolute Contraindications |

| Aspirin allergy | Aspirin allergy |

| Active bleeding on arrival or within 24 hours after arrival | Bleeding on arrival or within 48 hours prior to arrival |

| Coumadin as pre-arrival medication | Coumadin prior to admission |

| Any other reason documented by PA/MD for not giving ASA on admission | Relative Contraindications |

| Bleeding risk | |

| History of internal bleeding | |

| History of bleeding disorder | |

| Chronic liver disease | |

| First platelet count drawn within 24 hours of arrival < 100×109/L | |

| Anemia | |

| History of peptic ulcer disease | |

| Renal insufficiency on admission | |

| BETA-BLOCKER ON ADMISSION | |

| Additional exclusions for Beta-blocker on admission | Absolute Contraindications |

| Beta-blocker allergy | Beta blocker allergy |

| Bradycardia (HR < 60) on arrival or within 24 hours after arrival while not on a beta-blocker | Bradycardia on admission without taking a beta blocker |

| Heart failure on arrival or within 24 hours after arrival | Heart failure at admission |

| CHF/pulmonary edema on admission | |

| Pulmonary edema on chest x-ray within 24 hours of arrival | |

| CHF on chest x-ray within 24 hours of arrival | |

| Shock on arrival or within 24 hours after arrival | Shock on admission |

| 2nd or 3rd degree heart block on ECG on arrival or within 24 hours after arrival and does not have a pacemaker | Heart block |

| 2nd or 3rd degree heart block | |

| first degree PR interval > 240 milliseconds on arrival EKG | |

| Right bundle block and left fascicular block on arrival EKG | |

| ICD-9-CM heart block codes | |

| Any other reason documented by PA/MD for not giving Beta-blocker on admission | Relative Contraindications |

| Heart failure at admission | |

| History of HF | |

| Previous LVEF < 50 and LVEF not equal to missing | |

| COPD | |

| History of COPD | |

| ICD-9-CM COPD codes | |

| Asthma | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | |

| Hypotension | |

| Renal insufficiency | |

| DISCHARGE MEASURES | |

| CMS Exclusions for all discharge measures | Ineligible for all discharge measures |

| < 18 years of age* | [Cohort includes >65 y.o only] |

| Patients who left AMA * | Patients who left AMA |

| Patients discharged to hospice* | Terminal Illness |

| Patients with comfort measures only documented by a physician, APRN or PA* | Terminal Illness |

| Patients transferred to another acute care hospital or federal hospital | Patient transferred out of the hospital |

| Patients who expired | Patient dead at discharge or discharge status unknown |

| ASPIRIN ON DISCHARGE | |

| Additional exclusions for ASA at discharge | Absolute Contraindications |

| Aspirin allergy | History of allergy to ASA or reaction to ASA during hospitalization |

| Active bleeding on arrival | Bleeding on admission |

| Active bleeding during hospital stay | Bleeding during hospitalization |

| Coumadin prescribed at discharge | Warfarin prescribed at discharge |

| Any other reason documented by PA/MD for not giving ASA on discharge | Relative Contraindications |

| Bleeding risk | |

| History of internal bleeding | |

| History of bleeding disorder | |

| Chronic liver disease | |

| Low platelet count | |

| Anemia | |

| History of peptic ulcer disease | |

| Acute UGI disorder during index admission | |

| Renal insufficiency | |

| BETA-BLOCKER AT DISCHARGE | |

| Additional exclusions for BB at discharge | Absolute Contraindications |

| Beta-blocker allergy | History of allergy to beta blockers or reaction to beta blockers during hospitalization |

| Second or third degree heart block on ECG on arrival or during hospital stay and does not have a pacemaker | Heart block |

| 2nd or 3rd degree heart block | |

| first degree PR interval > 240 milliseconds on arrival EKG | |

| Right bundle block and left fascicular block on arrival EKG | |

| Heart block second or third degree on any EKG during hospital stay | |

| Right bundle block and left fascicular block during hospital | |

| ICD-9-CM heart block codes | |

| Bradycardia (<60bpm) on day of discharge or day prior to discharge while not on beta blocker | Bradycardia |

| Bradycardia during hospital stay | |

| Last pulse documented < 60 and did not take beta blocker on discharge | |

| Any other reason documented by PA/MD for not giving beta-blocker on discharge | Relative Contraindications |

| Heart failure and (LVEF<50 or unknown) | |

| Heart failure on admission | |

| CHF on chest x-ray within 24 hours of arrival | |

| Heart failure during stay | |

| ICD-9-CM heart failure codes | |

| LVEF unknown or less than 50 | |

| LVEF less than 30 | |

| Shock | |

| Shock on arrival | |

| Shock during stay | |

| ICD-9-CM shock codes | |

| Hypotension | |

| Hypotension during stay | |

| Last systolic BP < 100mm Hg and did not take beta blocker on discharge | |

| COPD | |

| History of COPD | |

| ICD-9-CM COPD codes | |

| Asthma | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | |

| ACE-I USE AT DISCHARGE | |

| Additional Exclusions for ACE-I at Discharge | Ineligible |

| Chart documentation of an LVEF < 40% or a narrative description of LVS function consistent with moderate or severe systolic dysfunction | LVEF not between 0 and 40 |

| Absolute Contraindications | |

| ACE-I allergy | History of allergy to ACE or reaction to ACE during hospitalization |

| Moderate or severe aortic stenosis | Aortic stenosis |

| Aortic stenosis | |

| Cardiac cath aortic stenosis | |

| ICD-9-CM aortic stenosis codes | |

| Any other reason documented by PA/MD for not giving ACE-I on discharge | Relative Contraindications |

| Creatinine > 2 on admission or during hospitalization | |

| Hypotension at discharge and did not have ACE at discharge | |

Appendix Table 2.

Number and proportion of patients with given contraindications

| Characteristics | Total | 1994–1995 | 1998–1999 | 2000–2001 | Overall P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | ||

| ASA at Admission | |||||||||

| Ineligible | |||||||||

| Discharged/left AMA/transferred out/died on admission day or day after | 23849 | 11.05 | 16975 | 9.93 | 3279 | 11.27 | 3595 | 12.13 | <0.001 |

| Terminal illness | 726 | 0.24 | 624 | 0.37 | 64 | 0.22 | 38 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Transferred in | 27316 | 14.05 | 18005 | 10.53 | 4411 | 15.51 | 4900 | 16.73 | <0.001 |

| Excluded (medical contraindication) | |||||||||

| Aspirin allergy | 9827 | 6.96 | 7398 | 4.33 | 1199 | 10.79 | 1230 | 10.43 | <0.001 |

| Active bleeding on arrival or within 48 hours | 7332 | 3.64 | 5251 | 3.07 | 1030 | 3.85 | 1051 | 4.11 | <0.001 |

| Coumadin/Warfarin as pre-arrival medication | 16226 | 8.42 | 11411 | 6.68 | 2344 | 9.26 | 2471 | 9.82 | <0.001 |

| Discretionary (Relative contraindication) | |||||||||

| Bleeding risk | 24035 | 12.12 | 16673 | 9.75 | 3505 | 12.89 | 3857 | 14.11 | <0.001 |

| History of internal bleeding | 20327 | 10.17 | 14147 | 8.28 | 2870 | 10.39 | 3310 | 12.13 | <0.001 |

| History of bleeding disorder | 1423 | 0.77 | 905 | 0.53 | 263 | 0.99 | 255 | 0.84 | <0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 791 | 0.31 | 649 | 0.38 | 69 | 0.26 | 73 | 0.28 | 0.0031 |

| First platelet count drawn within 24 hours of arrival < 100×109/L | 2585 | 1.44 | 1701 | 1.00 | 468 | 1.87 | 416 | 1.55 | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 13704 | 7.51 | 9388 | 5.49 | 1952 | 7.79 | 2364 | 9.55 | <0.001 |

| History of peptic ulcer disease | 29976 | 12.93 | 22961 | 13.43 | 3557 | 12.77 | 3458 | 12.49 | <0.001 |

| Renal insufficiency on admission | 8388 | 4.37 | 5843 | 3.42 | 1187 | 4.56 | 1358 | 5.28 | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker on admission | |||||||||

| Ineligible | |||||||||

| Discharged/left against AMA/transferred out/died on the admission day or the day after | 23849 | 11.05 | 16975 | 9.93 | 3279 | 11.27 | 3595 | 12.13 | <0.001 |

| Terminal illness | 726 | 0.24 | 624 | 0.37 | 64 | 0.22 | 38 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Transferred in | 27316 | 14.05 | 18005 | 10.53 | 4411 | 15.51 | 4900 | 16.73 | <0.001 |

| Excluded (medical contraindication) | |||||||||

| Beta-blocker allergy | 1332 | 1.10 | 846 | 0.49 | 193 | 1.57 | 293 | 2.26 | <0.001 |

| Bradycardia (heart rate less than 60 bpm) on arrival or within 24 hours after arrival while not on beta-blocker | 15020 | 6.03 | 11717 | 6.85 | 1732 | 5.86 | 1571 | 5.25 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure on arrival or within 24 hours after arrival | 79745 | 35.44 | 61221 | 35.82 | 9536 | 36.11 | 8988 | 34.43 | 0.0018 |

| CHF/pulmonary edema on admission | 59724 | 24.73 | 48025 | 28.10 | 6136 | 23.71 | 5563 | 21.84 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary edema on chest x-ray within 24 hours of arrival | 25841 | 13.29 | 19654 | 12.75 | 3424 | 15.30 | 2763 | 12.15 | <0.001 |

| CHF on chest x-ray within 24 hours of arrival | 51710 | 26.48 | 39457 | 25.60 | 6213 | 27.34 | 6040 | 26.76 | <0.001 |

| Second or third degree heart block on ECG on arrival or within 24 hours after arrival and does not have a pacemaker | 16050 | 7.52 | 11576 | 6.77 | 2222 | 7.91 | 2252 | 8.01 | <0.001 |

| 2nd or 3rd degree heart block | 2845 | 1.18 | 2295 | 1.44 | 282 | 1.05 | 268 | 0.99 | <0.001 |

| first degree PR interval > 240 milliseconds on arrival EKG | 1670 | 3.14 | 782 | 2.95 | 888 | 3.31 | |||

| Right bundle block and left fascicular block on arrival EKG | 5055 | 2.38 | 3753 | 2.20 | 637 | 2.53 | 665 | 2.47 | 0.0052 |

| ICD-9-CM heart block codes | 8509 | 3.15 | 6961 | 4.07 | 850 | 2.83 | 698 | 2.39 | <0.001 |

| Shock on arrival or within 24 hours after arrival | 5190 | 1.87 | 4364 | 2.55 | 513 | 1.81 | 313 | 1.15 | <0.001 |

| Discretionary (Relative contraindication) | |||||||||

| Heart failure at admission | 56411 | 29.34 | 39350 | 23.02 | 8067 | 31.14 | 8994 | 34.87 | <0.001 |

| History of HF | 50703 | 26.17 | 35603 | 20.83 | 7125 | 27.55 | 7975 | 30.98 | <0.001 |

| Previous LVEF < 50 and LVEF not equal to missing | 14473 | 8.83 | 8820 | 5.16 | 2525 | 9.75 | 3128 | 12.15 | <0.001 |

| COPD | 53789 | 25.53 | 39408 | 23.06 | 6973 | 26.18 | 7408 | 27.76 | <0.001 |

| History of COPD | 47462 | 22.49 | 34756 | 20.33 | 6097 | 22.85 | 6609 | 24.62 | <0.001 |

| ICD-9-CM COPD codes | 35613 | 16.86 | 26341 | 15.41 | 4535 | 17.24 | 4737 | 18.16 | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 4158 | 2.06 | 2868 | 1.68 | 619 | 2.15 | 671 | 2.40 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 160 | 0.09 | 111 | 0.06 | 22 | 0.08 | 27 | 0.14 | 0.0613 |

| Hypotension | 16847 | 7.67 | 12520 | 7.32 | 2097 | 7.51 | 2230 | 8.20 | <0.001 |

| Aspirin on discharge | |||||||||

| Ineligible | |||||||||

| Patients transferred to another acute care hospital or federal hospital | 41191 | 17.90 | 31265 | 18.29 | 5049 | 17.96 | 4877 | 17.41 | 0.0795 |

| Patients who died | 31239 | 13.27 | 24596 | 14.39 | 3322 | 12.53 | 3321 | 12.65 | <0.001 |

| Patients who left AMA | 314 | 0.23 | 181 | 0.11 | 67 | 0.31 | 66 | 0.29 | <0.001 |

| Patients with unknown discharge status | 676 | 0.67 | 148 | 0.09 | 173 | 0.61 | 355 | 1.38 | <0.001 |

| Terminal illness | 726 | 0.24 | 624 | 0.37 | 64 | 0.22 | 38 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Excluded (medical contraindication) | |||||||||

| History of allergy to ASA or reaction to ASA during hospitalization | 10019 | 4.58 | 7537 | 4.41 | 1217 | 4.65 | 1265 | 4.72 | 0.0955 |

| Active bleeding on arrival or during hospital stay | |||||||||

| Bleeding on admission | 7332 | 3.64 | 5251 | 3.07 | 1030 | 3.85 | 1051 | 4.11 | <0.001 |

| Bleeding during hospitalization | 39807 | 18.79 | 29215 | 17.09 | 4914 | 18.34 | 5678 | 21.12 | <0.001 |

| Coumadin/Warfarin prescribed at discharge | 24609 | 11.41 | 19169 | 11.21 | 2826 | 12.13 | 2614 | 11.05 | 0.0045 |

| Discretionary (Relative contraindication) | |||||||||

| Bleeding risk | 24035 | 12.12 | 16673 | 9.75 | 3505 | 12.89 | 3857 | 14.11 | <0.001 |

| History of internal bleeding | 20327 | 10.17 | 14147 | 8.28 | 2870 | 10.39 | 3310 | 12.13 | <0.001 |

| History of bleeding disorder | 1423 | 0.77 | 905 | 0.53 | 263 | 0.99 | 255 | 0.84 | <0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 791 | 0.31 | 649 | 0.38 | 69 | 0.26 | 73 | 0.28 | 0.0031 |

| Low platelet count | 2585 | 1.44 | 1701 | 1.00 | 468 | 1.87 | 416 | 1.55 | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 13704 | 7.51 | 9388 | 5.49 | 1952 | 7.79 | 2364 | 9.55 | <0.001 |

| History of peptic ulcer disease | 29976 | 12.93 | 22961 | 13.43 | 3557 | 12.77 | 3458 | 12.49 | <0.001 |

| Acute UGI disorder during index admission | 910 | 0.47 | 668 | 0.39 | 108 | 0.49 | 134 | 0.54 | 0.0214 |

| Renal insufficiency | 16476 | 8.25 | 11791 | 6.90 | 2226 | 8.52 | 2459 | 9.56 | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker on discharge | |||||||||

| Ineligible | |||||||||

| Patients transferred to another acute care hospital or federal hospital | 41191 | 17.90 | 31265 | 18.29 | 5049 | 17.96 | 4877 | 17.41 | 0.0795 |

| Patients who died | 31239 | 13.27 | 24596 | 14.39 | 3322 | 12.53 | 3321 | 12.65 | <0.001 |

| Patients who left AMA | 314 | 0.23 | 181 | 0.11 | 67 | 0.31 | 66 | 0.29 | <0.001 |

| Patients with unknown discharge status | 676 | 0.67 | 148 | 0.09 | 173 | 0.61 | 355 | 1.38 | <0.001 |

| Terminal illness | 726 | 0.24 | 624 | 0.37 | 64 | 0.22 | 38 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Excluded (medical contraindication) | |||||||||

| Beta-blocker allergy | 2267 | 1.11 | 1505 | 0.88 | 307 | 0.98 | 455 | 1.48 | <0.001 |

| Bradycardia (heart rate less than 60 on day of discharge or day prior to discharge while not on a beta-blocker) | 93199 | 44.84 | 66604 | 38.97 | 12431 | 45.11 | 14164 | 51.24 | <0.001 |

| Bradycardia during hospital stay | 88839 | 43.60 | 62574 | 36.61 | 12216 | 44.37 | 14049 | 50.82 | <0.001 |

| Last pulse documented < 60 and did not take beta blocker on discharge | 14818 | 4.87 | 12930 | 7.56 | 1028 | 3.55 | 860 | 2.98 | <0.001 |

| Second or third degree heart block on ECG on arrival or during hospital stay and does not have a pacemaker | 24809 | 11.21 | 18547 | 10.85 | 3064 | 11.13 | 3198 | 11.68 | 0.0050 |

| 2nd or 3rd degree heart block | 2845 | 1.18 | 2295 | 1.44 | 282 | 1.05 | 268 | 0.99 | <0.001 |

| first degree PR interval > 240 milliseconds on arrival EKG | 1670 | 3.14 | 782 | 2.95 | 888 | 3.31 | |||

| Right bundle block and left fascicular block on arrival EKG | 5055 | 2.38 | 3753 | 2.20 | 637 | 2.53 | 665 | 2.47 | 0.0052 |

| Heart block second or third degree on any EKG during hospital stay | 8950 | 3.38 | 7372 | 4.31 | 769 | 2.78 | 809 | 2.84 | <0.001 |

| Right bundle block and left fascicular block during hospital | 11317 | 5.12 | 8638 | 5.05 | 1287 | 5.06 | 1392 | 5.24 | 0.6213 |

| ICD-9-CM heart block codes | 8509 | 3.15 | 6961 | 4.07 | 850 | 2.83 | 698 | 2.39 | 0.0000 |

| Discretionary (Relative contraindication) | |||||||||

| Heart failure and (LVEF<50 or unknown) | 93241 | 42.19 | 70710 | 41.37 | 11265 | 42.40 | 11266 | 42.95 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure on admission | 59724 | 24.73 | 48025 | 28.10 | 6136 | 23.71 | 5563 | 21.84 | <0.001 |

| CHF on chest x-ray within 24 hours of arrival | 63042 | 28.37 | 48026 | 28.10 | 7705 | 29.28 | 7311 | 27.87 | 0.0056 |

| Heart failure during stay | 96159 | 43.91 | 72744 | 42.56 | 11434 | 43.49 | 11981 | 45.80 | <0.001 |

| ICD-9-CM heart failure codes | 89659 | 40.72 | 68159 | 39.88 | 10771 | 41.02 | 10729 | 41.40 | 0.0003 |

| LVEF unknown or less than 50 | 162509 | 71.25 | 124160 | 72.64 | 19528 | 71.30 | 18821 | 69.63 | <0.001 |

| LVEF less than 30 | 21299 | 10.63 | 15499 | 9.07 | 2842 | 11.23 | 2958 | 11.85 | <0.001 |

| Shock | 18424 | 7.87 | 14387 | 8.42 | 2084 | 7.73 | 1953 | 7.37 | <0.001 |

| Shock on arrival | 5190 | 1.87 | 4364 | 2.55 | 513 | 1.81 | 313 | 1.15 | <0.001 |

| Shock during stay | 16370 | 12.71 | 12683 | 7.42 | 1857 | 24.88 | 1830 | 22.36 | <0.001 |

| ICD-9-CM shock codes | 11538 | 4.98 | 8988 | 5.26 | 1280 | 4.75 | 1270 | 4.86 | 0.0040 |

| Hypotension | 66620 | 30.15 | 49529 | 28.98 | 8264 | 29.44 | 8827 | 32.11 | <0.001 |

| Hypotension during stay | 57708 | 27.48 | 41424 | 24.23 | 7803 | 27.84 | 8481 | 30.82 | <0.001 |

| Last systolic BP < 100mm Hg and did not take beta blocker on discharge | 21714 | 6.30 | 19936 | 11.66 | 955 | 3.26 | 823 | 2.93 | <0.001 |

| COPD | 53789 | 25.53 | 39408 | 23.06 | 6973 | 26.18 | 7408 | 27.76 | <0.001 |

| History of COPD | 47462 | 22.49 | 34756 | 20.33 | 6097 | 22.85 | 6609 | 24.62 | <0.001 |

| ICD-9-CM COPD codes | 35613 | 16.86 | 26341 | 15.41 | 4535 | 17.24 | 4737 | 18.16 | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 4158 | 2.06 | 2868 | 1.68 | 619 | 2.15 | 671 | 2.40 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 160 | 0.09 | 111 | 0.06 | 22 | 0.08 | 27 | 0.14 | 0.0613 |

| ACE-I at discharge | |||||||||

| Ineligible | |||||||||

| Patients transferred to another acute care hospital or federal hospital | 41191 | 17.90 | 31265 | 18.29 | 5049 | 17.96 | 4877 | 17.41 | 0.0795 |

| Patients who died | 31239 | 13.27 | 24596 | 14.39 | 3322 | 12.53 | 3321 | 12.65 | <0.001 |

| Patients who left AMA | 314 | 0.23 | 181 | 0.11 | 67 | 0.31 | 66 | 0.29 | <0.001 |

| Terminal illness | 676 | 0.67 | 148 | 0.09 | 173 | 0.61 | 355 | 1.38 | <0.001 |

| Patients with unknown discharge status | 726 | 0.24 | 624 | 0.37 | 64 | 0.22 | 38 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| LVEF not between 0 and 40 | 177111 | 76.74 | 134930 | 78.94 | 21245 | 75.71 | 20936 | 75.17 | <0.001 |

| Excluded (medical contraindication) | |||||||||

| History of allergy to ACE or reaction to ACE during hospitalization | 2344 | 1.20 | 1474 | 0.86 | 365 | 1.26 | 505 | 1.52 | <0.001 |

| Aortic stenosis | 15049 | 6.91 | 11339 | 6.63 | 1871 | 7.27 | 1839 | 6.92 | 0.0225 |

| Aortic stenosis | 5845 | 5.10 | 4246 | 4.44 | 794 | 5.63 | 805 | 5.38 | <0.001 |

| Cardiac cath aortic stenosis | 2522 | 2.29 | 2198 | 3.88 | 169 | 1.71 | 155 | 1.33 | <0.001 |

| ICD-9-CM aortic stenosis codes | 10454 | 5.09 | 7550 | 4.42 | 1449 | 5.49 | 1455 | 5.51 | <0.001 |

| Discretionary (Relative Contraindications) | |||||||||

| Creatinine > 2 on admission or during hospitalization | 38490 | 18.82 | 27878 | 16.31 | 4968 | 18.94 | 5644 | 21.54 | <0.001 |

| Hypotension at discharge and did not have ACE at discharge | 22156 | 6.62 | 20095 | 11.76 | 1036 | 3.50 | 1025 | 3.57 | <0.001 |

REFERENCES

- 1.Jha AK, Li Z, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Care in U.S. hospitals--the Hospital Quality Alliance program. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jul 21;353(3):265–274. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa051249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hospital Quality Alliance. [Accessed July 23, 2009]; http://www.hospitalqualityalliance.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services. Hospital Compare homepage. [Accessed June, 23, 2009]; http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/Hospital/Home2.asp?version=alternate&browser=IE%7C6%7CWinXP&language=English&defaultstatus=0&pagelist=Home.

- 4.Williams SC, Schmaltz SP, Morton DJ, Koss RG, Loeb JM. Quality of care in U.S. hospitals as reflected by standardized measures, 2002–2004. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jul 21;353(3):255–264. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindenauer PK, Remus D, Roman S, et al. Public reporting and pay for performance in hospital quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2007 Feb 1;356(5):486–496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masoudi FA, Foody JM, Havranek EP, et al. Trends in acute myocardial infarction in 4 US states between 1992 and 2001: clinical characteristics, quality of care, and outcomes. Circulation. 2006 Dec 19;114(25):2806–2814. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.611707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White House. [Accessed July 24, 2009]; http://www.whitehouse.gov/MedicareFactSheetFinal/.

- 8.Quality Net. [Accessed March 29, 2009];Specifics manual 2.5. http://qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&cid=1203781887871. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rathore SS, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Ordin DL, Krumholz HM. Quality of care of Medicare beneficiaries with acute myocardial infarction: who is included in quality improvement measurement? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 Apr;51(4):466–475. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marciniak TA, Ellerbeck EF, Radford MJ, et al. Improving the quality of care for Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. JAMA. 1998 May 6;279(17):1351–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burwen DR, Galusha DH, Lewis JM, et al. National and state trends in quality of care for acute myocardial infarction between 1994–1995 and 1998–1999: the medicare health care quality improvement program. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Jun 23;163(12):1430–1439. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.12.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jencks SF, Cuerdon T, Burwen DR, et al. Quality of medical care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries: A profile at state and national levels. JAMA. 2000 Oct 4;284(13):1670–1676. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jencks SF, Huff ED, Cuerdon T. Change in the quality of care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–1999 to 2000–2001. JAMA. 2003 Jan 15;289(3):305–312. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellerbeck EF, Jencks SF, Radford MJ, et al. Quality of care for Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction. A four-state pilot study from the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. JAMA. 1995 May 17;273(19):1509–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jencks SF, Wilensky GR. The health care quality improvement initiative. A new approach to quality assurance in Medicare. JAMA. 1992 Aug 19;268(7):900–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rathore SS, Mehta RH, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Effects of age on the quality of care provided to older patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2003 Mar;114(4):307–315. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST, Jr, Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 30;351(27):2870–2874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb042458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005 Aug 10;294(6):716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottlieb SS, McCarter RJ, Vogel RA. Effect of beta-blockade on mortality among high-risk and low-risk patients after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998 Aug 20;339(8):489–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krumholz HM, Radford MJ, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Aspirin in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction in elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Patterns of use and outcomes. Circulation. 1995 Nov 15;92(10):2841–2847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krumholz HM, Chen YT, Wang Y, Radford MJ. Aspirin and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors among elderly survivors of hospitalization for an acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2001 Feb 26;161(4):538–544. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]