Abstract

Objective

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is a neuroinflammatory disease of spinal cord and optic nerve associated with serum autoantibodies (NMO-IgG) against astrocyte water channel aquaporin-4 (AQP4). Recent studies suggest that AQP4 autoantibodies are pathogenic. The objectives of this study were to establish an ex vivo spinal cord slice model in which NMO-IgG exposure produces lesions with characteristic NMO pathology, and to test the involvement of specific inflammatory cell types and soluble factors.

Methods

Vibratome-cut transverse spinal cord slices were cultured on transwell porous supports. After 7 days in culture, spinal cord slices were exposed NMO-IgG and complement for 1–3 days. In some studies inflammatory cells or factors were added. Slices were examined for GFAP, AQP4 and myelin immunoreactivity.

Results

Spinal cord cellular structure, including astrocytes, microglia, neurons and myelin, was preserved in culture. NMO-IgG bound strongly to astrocytes in the spinal cord slices. Slices exposed to NMO-IgG and complement showed marked loss of GFAP, AQP4 and myelin. Lesions were not seen in the absence of complement or in spinal cord slices from AQP4 null mice. In cultures treated with submaximal NMO-IgG, the severity of NMO lesions was increased with inclusion of neutrophils, natural-killer cells or macrophages, or the soluble factors TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β or interferon-γ. Lesions were also produced in ex vivo optic nerve and hippocampal slice cultures.

Interpretation

These results provide evidence for AQP4, complement- and NMO-IgG-dependent NMO pathogenesis in spinal cord, and implicate the involvement of specific immune cells and cytokines. Our ex vivo model allows for direct manipulation of putative effectors of NMO disease pathogenesis in a disease-relevant tissue.

INTRODUCTION

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is a neuroinflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system affecting primarily spinal cord and optic nerve, leading to paralysis and blindness.1, 2 A defining feature of NMO is the presence of serum immunoglobulin autoantibodies (NMO-IgG) against astrocyte water channel aquaporin-4 (AQP4).3, 4 NMO lesions are characterized by granulocyte and macrophage infiltrates, loss of AQP4, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and myelin, and perivascular complement deposition.5–7 Indirect evidence has suggested that NMO-IgG is pathogenic in NMO.8 NMO-IgG seropositivity is highly specific for NMO, and serum NMO-IgG titer often correlates with NMO disease activity.9, 10 Therapies that reduce circulating NMO-IgG or cause B-lymphocyte suppression often reduce clinical signs of NMO.11, 12 Elucidation of the determinants of NMO disease pathogenesis is important for development of new therapies. For example, if NMO-IgG binding to AQP4 is the initiating pathogenic event in NMO, then blocking this interaction by small molecules or monoclonal antibodies may be of therapeutic utility in NMO.

Recent data in rodent models suggest that NMO-IgG is pathogenic. Human NMO-IgG exacerbates neuroinflammatory lesions in rats with pre-existing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis13–15 or after treatment with complete Freund’s adjuvant.16 Naïve mice injected intracranially with human NMO-IgG with complement develop NMO-like lesions with CD45+ cell infiltrates, perivascular complement deposition, myelin loss, and reduced astrocyte GFAP and AQP4 immunoreactivity.17 Though these data suggest a causative role for NMO-IgG in NMO disease pathogenesis, their interpretation is subject to the caveat that significant lesions were produced in brain, which is minimally affected in NMO, and they required significant pre-existing neuroinflammation or intracerebral complement administration.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the pathogenicity of NMO-IgG in producing NMO lesions in an NMO disease-relevant tissue, the spinal cord. For these studies we established organ culture slice models of spinal cord, brain and optic nerve in which putative effectors of NMO pathology, including NMO-IgG, complement, immune cells and soluble inflammatory mediators, could be added under defined conditions.

METHODS

NMO-IgG

Recombinant monoclonal NMO antibody (NMO-rAb) and control-rAb were generated from clonally-expanded plasmablasts in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of a seropositive NMO patient as described.13 For some studies, NMO-IgGserum was purified from NMO human sera using a Melon Gel IgG Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) and concentrated using Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter Units (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Spinal cord slice cultures

Wild type and AQP4 null mice18 in a CD1 genetic background were used to prepare spinal cord slice cultures. Protocols were approved by the University of California San Francisco Committee on Animal Research. Organotypic spinal cord slice cultures were prepared using a modified interface-culture method.19 Postnatal day 7 mouse pups were decapitated and the spinal cord was rapidly removed and placed in ice-cold Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS, pH 7.2, Invitrogen). Transverse slices of cervical spinal cord of thickness 300 μm were cut using a vibratome (VT-1000S; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Individual slices were placed on transparent, non-coated membrane inserts (Millipore, Millicell-CM 0.4 μm pores, 30 mm diameter) in 6-well (35 mm diameter) plates containing 1 mL culture medium, with a thin film of culture medium covering the slices. The culture medium, consisting of 50% minimum essential medium (MEM), 25% HBSS, 25% horse serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 0.65% glucose and 25 mM HEPES, was changed every 3 days. The slices were cultured in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 7–10 days.

Ex vivo NMO models

In a three-day model, NMO-IgG (NMO-rAb or control-rAb, each 10 μg/ml), or purified IgG (NMO-IgGserum or control-IgGserum, 300 μg/ml) and/or human complement (10 %, pooled normal human complement serum, Innovative Research, Novi, Michigan) were added on day 7 to the culture medium (bathing the undersurface of the porous membrane). Slices were cultured for another 3 days, and then fixed for immunostaining. In a one-day model, NMO-IgG and/or complement were added to both sides of the porous membrane, with 1 mL medium added above the porous filter to fully immerse the slice. For cell studies, 5×106 neutrophils, 106 natural killer cells (NK-cells) or 106 macrophages were added only to the solution above the porous filter bathing the slice. LPS (1 μg/mL, Sigma), human neutrophil elastase (hNE, 1 μg/mL, Innovative Research), recombinant mouse IL-6 (100 ng/mL, Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA), recombinant mouse TNFα (100 ng/mL, Invitrogen), recombinant mouse IL-1β (100 ng/mL, GenScript, Piscataway, NJ), recombinant mouse IFN-β (2000 U/mL, PROSPEC, East Brunswick, NJ), recombinant IFN-γ (1000 U/mL, PROSPEC) or Sivelestat (200 μM, Enzo life science, Plymouth Meeting, PA) were added 24 h before NMO-IgG and/or human complement.

Scoring of spinal cord slices

AQP4 and GFAP stained spinal cord slices were scored for lesion severity using the following scale: 0, intact slice with intact GFAP and AQP4 staining; 1, intact slice with some astrocyte swelling (seen from GFAP stain) with weak AQP4 staining; 2, at least one lesion with complete loss of GFAP and AQP4 staining; 3, multiple lesions with loss of GFAP and AQP4 staining in > 30 % of slice area; 4, extensive loss of GFAP and AQP4 staining affecting > 80% of slice area. AQP4 null slices were scored only on the basis of GFAP staining.

Optic nerve culture

Optic nerves were isolated from adult mice and transferred immediately to oxygen-bubbled artificial CSF (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 glucose bubbled with 95% O2, 5% CO2, pH 7.4. In some experiments NMO-IgG and complement were added to the solution, and optic nerves were fixed after 24 h incubation. Samples were post-fixed for 24 h in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed in paraffin. Longitudinal sections of 7-μm thickness were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded ethanols. After epitope retrieval with citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6, 30 min, 95–100 °C), sections were immunostained as described in Supplementary Methods. Scoring was done as described above for spinal cord slices.

Hippocampal brain slice culture

Organotypic hippocampal tissue cultures were prepared from 7-day old mice and maintained using the interface culture method as described above. Slices of thickness 300 μm were placed on Millicell membrane inserts. Cultures were maintained in the same medium used for spinal cord slices. NMO-IgG and complement were added to the medium at day 7, and the slices were fixed after incubation for 3 days. Scoring for NMO lesions was done as for spinal cord slices.

RESULTS

Characterization of spinal cord slice cultures

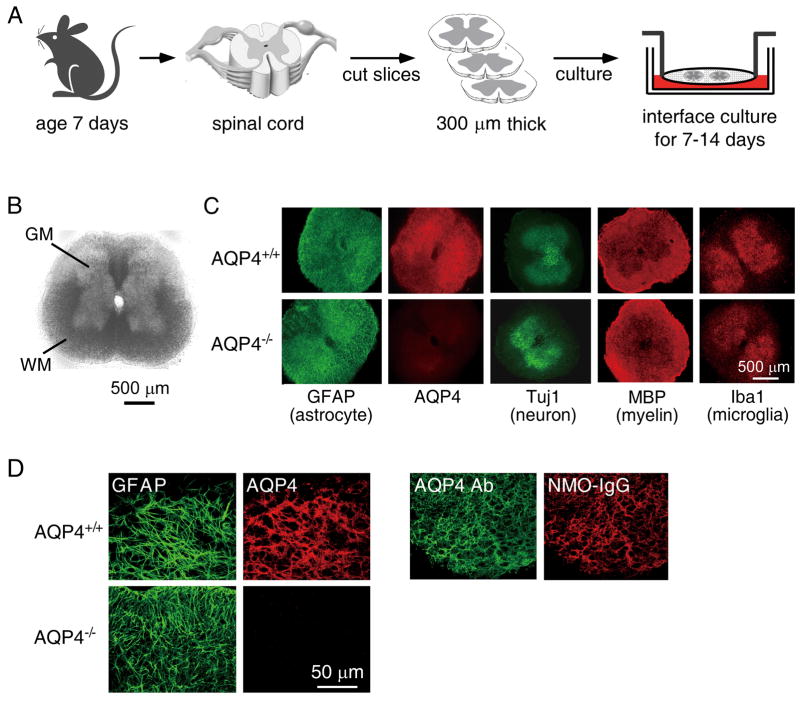

Spinal cord slices were maintained on semiporous membranes at an air–medium interface as diagrammed in Fig 1. The slices received oxygen from the air above and from the medium below. After 7 days in culture ex vivo, slice thickness was reduced from 300 μm to 100–150 μm, but the characteristic cytoarchitecture of spinal cord, with white matter surrounding grey matter, was preserved (Fig 1B). Slice viability was confirmed by lactate dehydrogenase release and live/dead cell staining (Supplementary Fig 1). The cultures also retained good cellular differentiation, with Fig 1C showing astrocytes stained for GFAP and AQP4, neurons in grey matter stained for Tuj1, myelin in white matter stained for myelin basic protein (MBP), and resting microglia in grey matter stained for Iba1. Similar structure was seen in slice cultures from wild type and AQP4 nullmice. High-magnification confocal microscopy showed colocalization of AQP4 and GFAP in astrocytes of spinal cord slices from wild type mice (Fig 1D, left). A recombinant monoclonal NMO-IgG (NMO-rAb) that strongly binds to the extracellular domain of AQP4 colocalized with an anti-AQP4 antibody that recognizes the intracellular AQP4 C-terminus (Fig 1D, right).

Figure 1.

Characterization of spinal cord slice cultures. A. Schematic showing spinal cord slices cultured on a semi-porous membrane at an air-medium interface. B. Bright-field image of a spinal cord slice cultured for 7 days. GM: grey matter, WM: white matter. C. Immuno-fluorescence of 7-day spinal cord slice cultures from wild type (AQP4+/+) and AQP4 null (AQP4−/−) mice for GFAP, AQP4, Tuj1, MBP and Iba1. D. AQP4 expression and NMO-IgG binding. High-magnification confocal fluorescence microscopy showing colocalization of: (left) GFAP (green) and AQP4 (red), and (right) NMO-IgG (red) and Ab (green).

NMO-IgG and complement produce NMO-like lesions in spinal cord slices

Three-day model

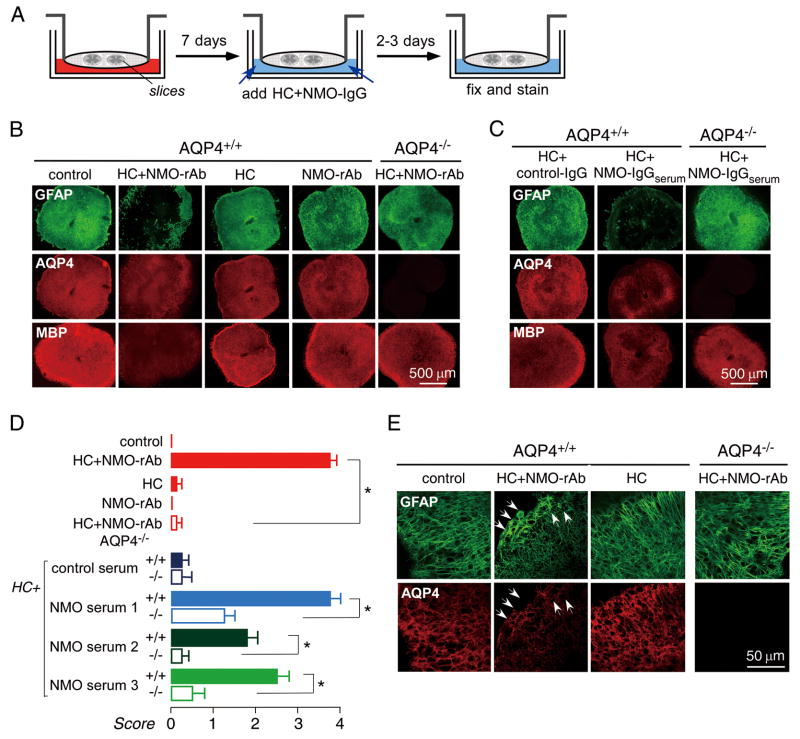

NMO-IgG binds to AQP4-expressing cells and activates complement, producing cell damage through the classical complement pathway. NMO-rAb (10 μg/mL) and human complement (10 %) were added to the medium on the undersurface of the semiporous membrane after spinal cord slices were cultured for seven days. Exposure of slices to NMO-rAb and human complement by diffusion through the porous membrane produced progressive NMO pathology. After three days of culture, most slices were affected, showing marked loss of GFAP and AQP4 staining, as well as marked myelin loss as seen by reduced MBP staining (Fig 2B). Pathology was not seen in slices incubated with human complement or NMO-rAb alone, or in slices from AQP4 null mice incubated with complement and NMO-rAb together. Similar pathology was seen with NMO-IgG purified from NMO patient serum (NMO-IgGserum,300 μg/mL) (Fig 2C). Fig 2D summarizes lesion scores for slices studied using NMO-rAb or NMO-IgGserum, showing that lesion development required NMO-IgG, complement and AQP4. Fig 2E shows by confocal microscopy that incubation of slices with NMO-rAb and complement for two days produces a submaximal response with astrocyte swelling and partial loss of GFAP and AQP4.

Figure 2.

Three-day NMO model. A. Schematic showing 7-day culture of spinal cord slices followed by 3-day incubation with NMO-IgG and/or human complement (HC). B. Immunofluorescence for GFAP (green), AQP4 (red) and MBP (red) at low magnificent in spinal cord slices incubated for 3 days with human complement (10 %) and/or NMO-rAb (10 μg/mL) as indicated. ‘Control’ indicates no added NMO-IgG or HC. C. Immunostaining of slices incubated with IgG isolated from control or NMO-IgGserum (300 μg/ml). D. Scoring of NMO lesion for studies done as in B and C (mean ± S.E., 8–12 slices per condition, * P < 0.001). E. Confocal fluorescence microscopy showing GFAP and AQP4 immunofluorescence at 2 days after NMO-rAb/HC addition. Arrows indicate swollen astrocytes with reduced AQP4 immunofluorescence.

One-day model

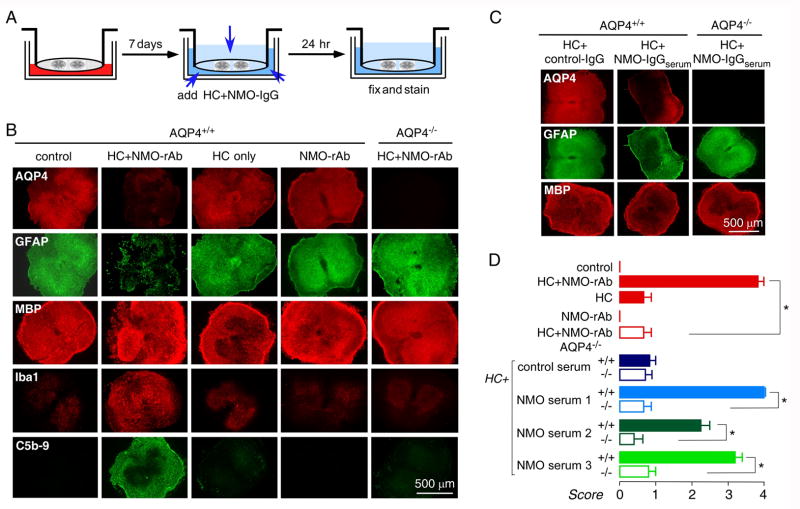

An alternative model was created in which NMO-IgG was added to both sides of the membrane in order to overcome the slow diffusion of NMO-IgG when added only to the medium on the undersurface of the membrane and for investigation of the role of inflammatory cells. In the one-day model the slice was covered with a thin layer of fluid (Fig 3A). Fig 3B (see Supplementary Fig 4B for confocal microscopy) shows that 24 h incubation with NMO-rAb (10 μg/mL) and human complement (10 %) produced marked loss of AQP4 and GFAP staining, as well as microglial activation as seen by Iba1 staining, and complement deposition as seen by C5b-9 staining. Cell cytotoxicity was seen as well (Supplementary Fig 1). However, there was minimal myelin loss (MBP) at one day in this model. MBP staining was validated using an alternative oligodendrocyte marker, CNPase (Supplementary Fig 4A). NMO-IgGserum (300 μg/mL) produced similar lesions (Fig 3C, D). Similar lesions were also produced in longitudinal spinal cord slice cultures exposed to NMO-IgG and complement (Supplementary Fig 2).

Figure 3.

One-day NMO model. A. Schematic showing 1-day incubation with NMO-IgG/HC after 7 days in culture. B. Immunofluorescence for GFAP (green), AQP4 (red), MBP (red), Iba1 (red) and C5b-9 (green) after incubation with HC (10 %) and/or NMO-rAb (10 μg/mL), as indicated. C. Immunofluorescence of slices incubated with IgG from control or NMO-IgGserum (300 μg/ml). D. Scoring of NMO lesion for studies done as in B and C (mean ± S.E., 8–12 slices per condition, * P < 0.001).

Inflammatory cells exacerbate NMO-like lesions

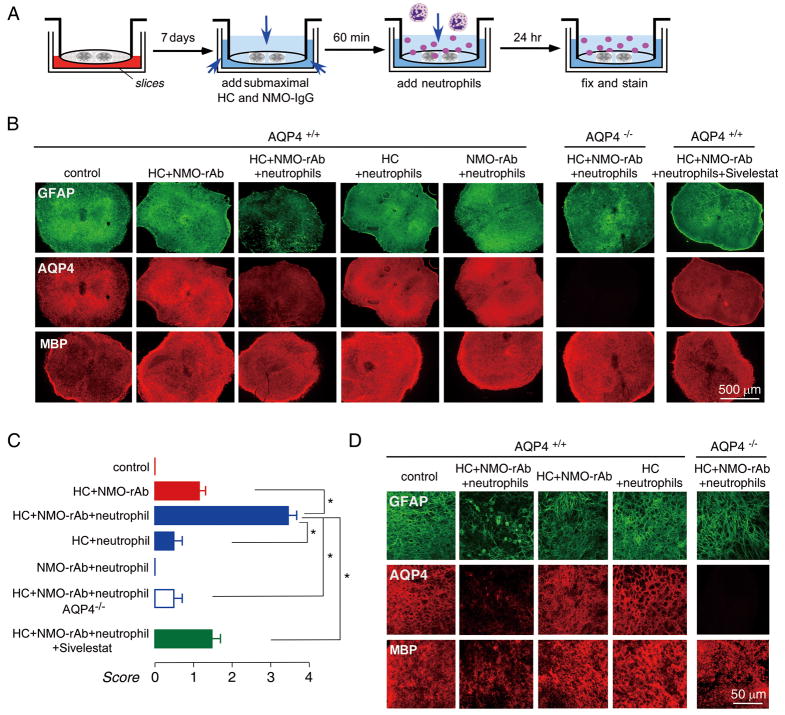

Infiltration by granulocytes (neutrophils and eosinophils) is seen in human NMO lesions.5 The effect of neutrophils was tested by addition of 5×106/well freshly isolated murine bone marrow neutrophils to the solution overlying the spinal cord slice in the one-day model, where neutrophils are able to contact the slice directly (Fig 4A). In the presence of submaximal NMO-rAb (5 μg/mL) and complement (5 %), which produced relatively mild lesions, addition of neutrophils greatly increased lesion severity, producing marked loss of GFAP and AQP4 staining (Fig 4B). The lesion was NMO-IgG and complement-dependent, as little effect was seen with when neutrophils were added with NMO-rAb or complement alone. Sivelestat, a neutrophil protease inhibitor, significantly reduced the severity of the lesion (at 200 μM) produced by neutrophils in the presence of NMO-rAb and complement (Fig 4B, C). Confocal imaging showed astrocyte swelling and loss in slices exposed to neutrophils in the presence of NMO-rAb and complement (Fig 4D).

Figure 4.

Neutrophils potentiate the development of NMO lesions in spinal cord slice cultures treated with NMO-IgG and complement. A. Schematic showing addition of submaximal HC/NMO-IgG after 7 days in culture, followed by neutrophils. B. Immunofluorescence of GFAP, AQP4 and MBP in slices incubated with HC (5 %) and/or NMO-rAb (5 μg/mL) and/or 5×106/well neutrophils, as indicated. Sivelestat (200 μM) was added with HC, NMO-rAb and neutrophils where indicated. C. Scoring of NMO lesion for studies done as in B (mean ± S.E., 6–8 slices per condition, * P < 0.001). D. Confocal fluorescence microscopy showing GFAP, AQP4 and MBP immunofluorescence under indicated conditions.

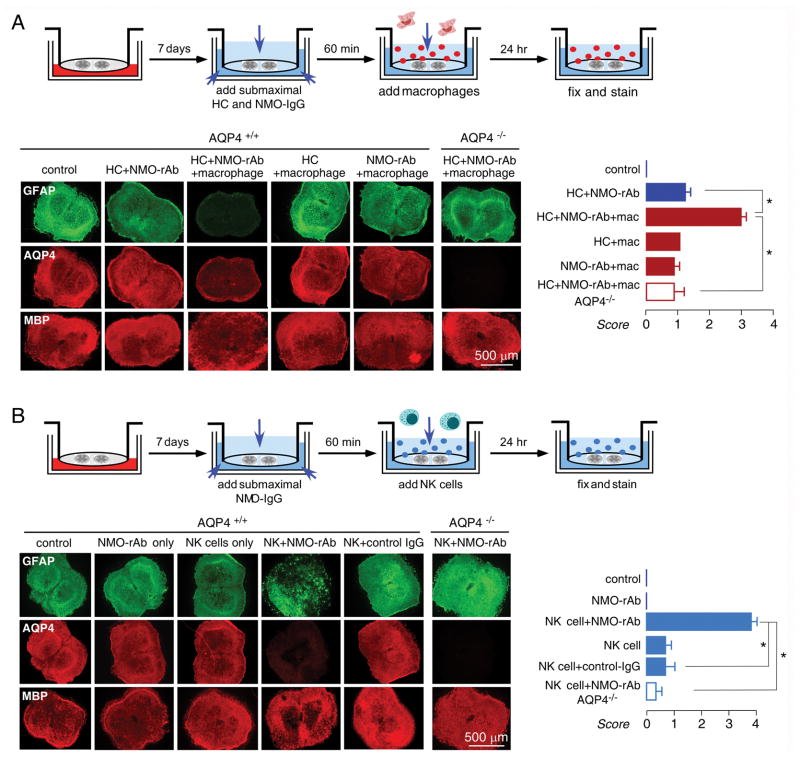

Macrophages are also seen in chronic NMO lesions in humans.5 We used bone marrow-derived mouse macrophages that were cultured in the presence of rm-CSF and activated for 24 h by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). As done to study neutrophil effects, 106/well macrophages were added to slice cultures together with submaximal NMO-rAb (5 μg/mL) and human complement (5 %). Fig 5A shows significant exacerbation of the lesion in the presence of macrophages, which required the presence of NMO-rAb, complement and AQP4.

Figure 5.

NK-cells and macrophages potentiate NMO lesions in spinal cord slice cultures treated with NMO-IgG and complement. A. (top) Schematic showing HC/NMO-IgG addition after 7 days in culture, followed by macrophages. (bottom, left) Immunofluorescence of GFAP, AQP4 and MBP in slices incubated with HC (5 %) and/or NMO-rAb (5 μg/mL) and/or macrophages (106/well) as indicated. (bottom, right) Scoring of NMO lesion (mean ± S.E., 6–8 slices per condition, * P < 0.001). B. (top) Schematic showing HC/NMO-IgG addition after 7 days in culture, followed by NK-cells. (bottom, left) Immunofluorescence of GFAP, AQP4 and MBP in slices incubated with HC (5 %) and/or NMO-rAb (5 μg/mL) and/or NK-cells (3×106/well) as indicated. (bottom, right) Scoring of NMO lesion (mean ± S.E., 6–8 slices per condition, * P < 0.001).

Natural-killer cells (NK-cells) are involved in antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC), though the possible involvement of NK-cells in NMO pathology in humans is uncertain. To test whether NK-cells could produce NMO-pathology in spinal cord slices in the absence of complement, 3×106/well NK-92 cells were added to slice cultures together with NMO-rAb (5 μg/mL). Fig 5B shows marked loss of GFAP and AQP4 staining, and some myelin loss, in slices exposed to NK-cells and NMO-rAb, which was not seen with NK-cells or NMO-rAb alone or with control IgG or in slices from AQP4 null mice. NMO pathology can thus be produced in the absence of complement.

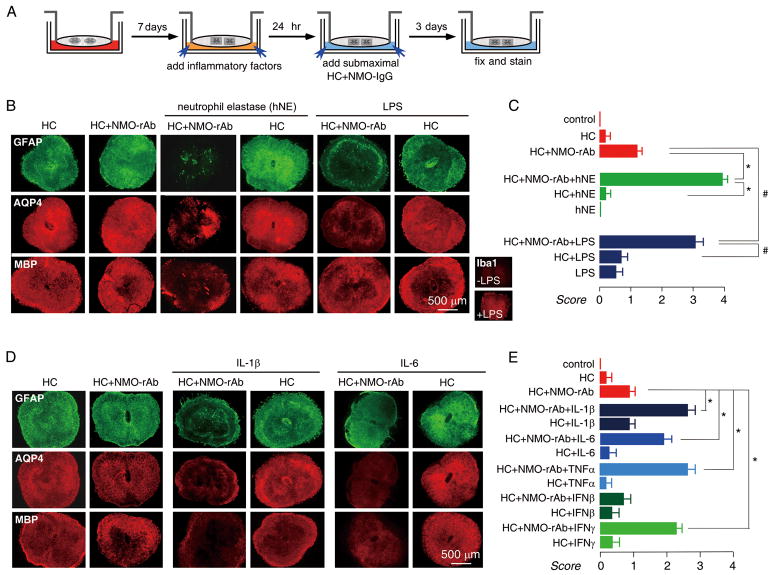

Inflammatory mediators exacerbate NMO-like lesions

The spinal cord slice model was used to test a series of soluble inflammatory mediators, as diagrammed in Fig 6A, in which mediators were added prior to submaximal NMO-rAb and complement. We first studied neutrophil elastase, a serine protease released from the primary granules of neutrophils. Based on the neutrophil and Sivelestat protection data in Fig 4, we postulated that the deleterious neutrophil effects may be mediated by neutrophil elastase. Using the three-day model, human neutrophil elastase (hNE, 100 ng/mL) in the presence of submaximal NMO-rAb and complement remarkably exacerbated the lesion, with near complete loss of GFAP, AQP4 and MBP, which was not seen in the absence of NMO-rAb. These data support the involvement of neutrophil proteases in NMO pathology and myelin loss.

Figure 6.

Inflammatory mediators potentiate NMO lesions in spinal cord slice cultures treated with NMO-IgG and complement. A. Schematic showing HC/NMO-IgG addition after 7 days in culture, followed by inflammatory factors, added individually. B. Immunofluorescence of GFAP, AQP4 and MBP in slices incubated with HC (5 %) and/or NMO-rAb (5 μg/mL) and/or human neutrophil elastase (hNE, 100 ng/mL) or LPS (1 μg/mL) as indicated. Inset shows Iba1 staining of slices without and with LPS. C. Scoring of NMO lesion (mean ± S.E., 6–8 slices per condition, * P < 0.001, hNE group; # P < 0.001, LPS group). D. Immunofluorescence of GFAP, AQP4 and MBP in slices incubated with HC (5 %) and/or NMO-rAb (5 μg/mL) and/or IL-1β (100 ng/mL) or IL-6 (100 ng/mL) as indicated. E. Scoring of NMO lesion (mean ± S.E., 6–8 slices per condition, * P < 0.001).

Microglia are resident macrophages in the central nervous system, which, like peripheral macrophages, can be activated by LPS to undergo morphological changes and release cytokines. We found that preincubation of slices with LPS (1 μg/mL), which strongly activated microglia throughout the slice (Fig 6B inset), significantly exacerbated the lesion produced by submaximal NMO-rAb and complement. LPS had little effect by itself or with complement alone. In additional experiments, we found that microglia activation was not necessary for lesion development, as similar NMO-IgG and complement-dependent lesions were found in microglia-depleted spinal cord slice cultures (Supplementary Fig 3).

Recent studies show a unique cytokine profile in NMO patient serum and CSF, including greater interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in NMO compared to multiple sclerosis and other neurological disorders.20 The involvement of these and other cytokines in NMO pathogenesis is unknown. We used the spinal cord slice model to study IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interferon-beta (IFN-β) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), by addition of cytokines, individually, prior to addition of submaximal NMO-rAb and complement. As shown in Fig 6C, IL-1β (100 ng/mL), IL-6 (100 ng/mL), TNFα (100 ng/mL) and IFN-γ (1000 U/mL) exacerbated the NMO-IgG dependent lesion, though IFN-β (at 2000 U/mL) had no effect. Specific cytokines are thus able to independently exacerbate NMO lesions produced by NMO-IgG and complement.

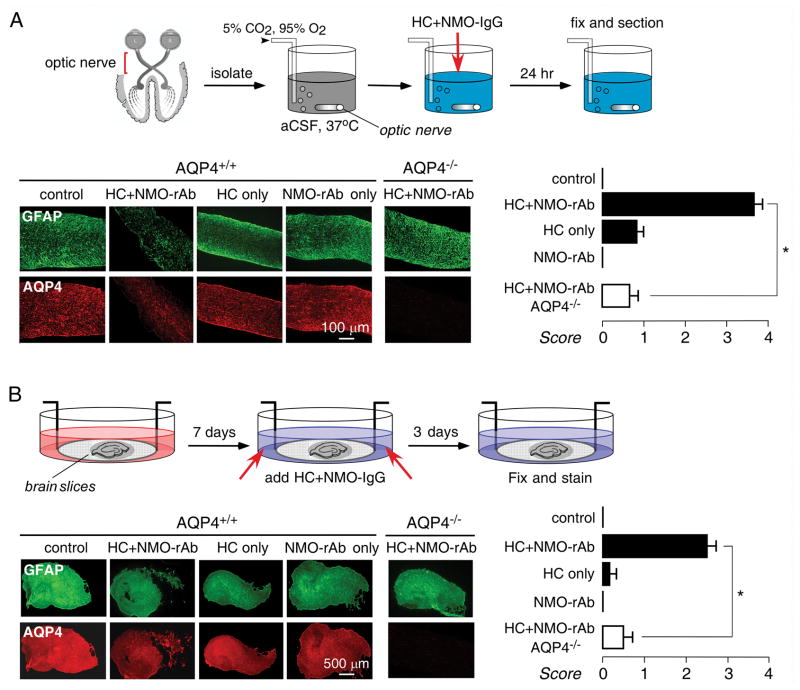

NMO lesions in ex vivo optic nerve and hippocampal slice cultures

The other major sites of pathology in NMO are optic nerve, and, to a lesser extent, brain. To investigate the utility of ex vivo NMO models of these tissues, optic nerve and brain slice cultures were studied. We found high level GFAP and AQP4 expression in optic nerve, though cellular viability was very sensitive to culture conditions and could be maintained reproducibly only for 24 h after isolation. Fig. 7A shows marked loss of GFAP and AQP4 staining in optic nerve when the media contained NMO-IgG (10 μg/mL) and complement (5 %), which was not seen with NMO-IgG or complement alone, or in optic nerve from AQP4 null mice. In hippocampal brain slice cultures, addition of NMO-IgG (10 μg/mL) and complement (10%) produced relatively mild lesions in a three-day model, compared to those seen in spinal cord cultures, with considerable heterogeneity in different areas of slices and variability from slice to slice. As in spinal cord, lesion development required NMO-IgG, complement and AQP4.

Figure 7.

Optic nerve and brain slice culture models of NMO. A. (top) Schematic showing 24 h incubation of freshly isolated optic nerves. (bottom, left) Immunofluorescence of GFAP and AQP4 in longitudinal thin sectins of optic nerve cultures incubated with HC (5 %) and/or NMO-rAb (10 μg/mL) as indicated. (bottom, right) Scoring of NMO lesion (mean ± S.E., 8–12 sections from 3 mice per condition, * P < 0.001). B. (top) Schematic showing 7 day incubation of hippocampal brain slices, following by HC and NMO-IgG addition. (bottom, left) Immunofluorescence of GFAP and AQP4 in brain slice cultures incubated with HC (10 %) and/or NMO-rAb (10μg/mL) as indicated. (bottom, right) Scoring of NMO lesion (mean ± S.E., 6–8 slices per condition, * P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Our results establish an ex vivo slice culture model to study NMO lesions in spinal cord. The model indicated the requirement of NMO-IgG, AQP4 and complement (or NK-cells) for lesion development, and demonstrated lesion-potentiating effects of neutrophils, macrophages and certain cytokines. We chose to focus on spinal cord rather than brain slices because NMO is a disease primarily of spinal cord, not brain. Though brain slice cultures also showed NMO-IgG, complement and AQP4-dependent lesions, they were of lesser severity than those in spinal cord slice cultures. Lesions were also seen in optic nerve cultures, though the technical difficulty and limited viability of optic nerve cultures limited their practical utility. Spinal cord from mice was used because of the availability of AQP4 null mice as a key control for the AQP4-dependence of lesion development, as well as the availability of various other disease-relevant transgenic mouse models. We used a purified monoclonal human NMO-IgG for most experiments to ensure reproducibility and avoid confounding factors present in human serum, though similar results in key studies were verified using IgG isolated from human NMO serum. Following characterization of spinal cord slices cultures, culture times and conditions were chosen in which NMO-IgG exposure produced clear-cut pathological lesions.

We found characteristic NMO lesions in spinal cord slice cultures from wild type mice that were treated with NMO-IgG and complement. Lesions were not seen in wild type mice treated with NMO-IgG or complement alone, or in AQP4 knockout mice treated with NMO-IgG and complement together. NMO-IgG by itself did not produce measurable pathology in our ex vivo model, even when added at very high concentration (NMO-rAb, 30 μg/mL, data not shown), which is contrary to an earlier report focused on primary astrocyte and mixed glial cultures.21 Our data support a mechanism in which NMO-IgG binds to AQP4 at the cell surface of astrocytes, resulting in complement activation, astrocyte cytotoxicity, and consequent loss of GFAP, AQP4 and myelin. Though myelin was largely intact in the one-day model, it was greatly reduced in the three-day model, suggesting that NMO-IgG does not produce oligodendrocyte damage directly, but more likely as a secondary effect following astrocyte damage.21 Since lesions developed in spinal cord slice cultures in vitro, we conclude that NMO-IgG, complement and AQP4 are necessary and sufficient for the development of lesions, though additional factors, such as inflammatory cells and mediators, can modulate lesion severity.

The finding of heterogeneity (focality) in submaximal lesions is a consistent and interesting observation, highlighting the stochastic nature of lesion development. Various factors may contribute to the focality of lesions, including spatial heterogeneity in the expression of AQP4 and various regulatory proteins, and in anatomical structures, as well as stochastic, positive-feedback phenomena. These same factors may be responsible for the focal initiation of NMO lesions in affected individuals.

The appearance of pathological lesions required AQP4, as lesions were not seen under any condition in spinal cord slices from AQP4 null mice. AQP4 is expressed in astrocytes throughout the central nervous system, including in brain, spinal cord, optic nerve, and various sensory organs.18 AQP4 expression is often polarized to astrocyte foot-processes that make contact with microvascular endothelia, but can be found throughout astrocyte plasma membranes. AQP4 is not expressed in other cell types in the central nervous system. Phenotype analysis of AQP4-deficient mice has implicated the involvement of AQP4 in brain22 and spinal cord23 water balance, astrocyte migration24 and K+/extracellular space dynamics during neuroexcitation.25 In addition, AQP4 appears to have an intrinsic pro-inflammatory role in brain by a mechanism that may involve increased cytokine release by astrocytes and localized cytotoxic edema.26 Structural data indicate that AQP4 monomers, each containing six helical transmembrane domains, form stable tetramers that assemble in square crystalline arrays called orthogonal arrays of particles.27 The determinants of NMO-IgG binding to AQP4, as well as the cellular processing of NMO-IgG, are subjects of active investigation. While there is good evidence that NMO-IgG binding to cell surface AQP4 on astrocytes causes complement-mediated cytotoxicity, the relative importance of cell-mediated cytotoxicity is unclear, as is the reason why NMO lesions are much more prevalent in spinal cord and optic nerve compared to brain, and absent in peripheral AQP4-expressing organs such as kidney, lung, skeletal muscle and stomach.

Our results suggest the involvement of neutrophils, macrophages and NK-cells in NMO pathology. Neutrophils are relatively short-lived cells that extravasate and degranulate in response to complement components C3b and C5a that act on neutrophil complement receptors.28 Neutrophils are present in human NMO lesions,1 as well as in early NMO-like lesions produced in mouse brain by intracerebral injection of NMO-IgG and human complement.29 We found that neutrophil addition to spinal cord slice cultures potentiated the severity of lesions produced by submaximal NMO-IgG and complement. The protective effect of Sivelastat and the lesion-potentiating effect of hNE implicate the involvement neutrophil elastase in neutrophil-dependent NMO lesions, and support the proposed utility of neutrophil protease inhibition in NMO therapy.29

Macrophage infiltration is a common feature in human NMO lesions,5 and a relatively late manifestation of NMO in a mouse model.17 Macrophages also express complement receptors30 and so can respond to complement activation with increased phagocytic activity. Microglia are resident macrophages in brain and spinal cord that express complement receptor CR3/MAC-1. Activated microglia show increased complement receptor expression, which is thought to facilitate the clearance of damaged cells in the brain.31 We found here that addition of macrophages, or LPS, which activates endogenous microglia, strongly potentiated the lesions produced by NMO-IgG and complement. Although various factors produced by macrophages might exacerbate neuroinflammatory injury, we found that addition of macrophages did not produce pathology unless complement and NMO-IgG were also present. These data support a prominent role of macrophages and activated microglia in the pathogenesis of NMO lesions. We also found that NK-cells, without complement, produced NMO lesions when NMO-IgG was present. As NK-cells are relatively rare in human NMO lesions,1 further investigation is needed to define their role and the role of ADCC in NMO.

As a neuroinflammatory disease, many proinflammatory cytokines are increased in the CSF in NMO, including TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β and IFN-γ; interestingly, IL-6 and IL-1β are increased in NMO but not in multiple sclerosis or other neuroinflammation diseases.20 In our model each of these cytokines, added individually, potentiated the lesions produced by NMO-IgG and complement, but did not by themselves cause pathology. The potentiating effect of these cytokines may involve a positive-feedback cycle of increased cytokine and chemokine secretion, or perhaps the down-regulation complement inhibitory regulators on the astrocytes such as CD59 and CD55.32 IL-1β also up-regulates complement C3 expression on astrocytes,33 which could also potentiate complement-mediated astrocyte damage. In contrast to the cytokines mentioned above, IFN-β did not potentiate lesion development in our model. IFN-β is involved in antigen presentation and T-cell proliferation, which has been found to have clinical benefit in multiple sclerosis but not in NMO.34

Advantages of our ex vivo model over models involving inducing NMO lesions in brain in vivo include tissue relevance and the ability to study effector actions under defined conditions. In addition the low cost and technical simplicity of our model allows for rapid screening of candidate effectors of NMO lesion development. However, there are limitations of any in vitro model of neuroinflammation. An in vitro slice model cannot recapitulate some of the potential determinants of neuroinflammation, such as multi-factorial cell and soluble mediator recruitment from the periphery, and influences of the blood-brain barrier and the intact vasculature. Unlike the environment in vivo, the exposure of spinal cord slices to a relatively large reservoir of culture media allows for dilutional washout of pro-inflammatory factors from the extracellular space. Last, we acknowledge that although the major cellular components in spinal cord remain viable in the slice culture, the precise cord anatomy is incompletely preserved with vascular structures largely absent. Notwithstanding these caveats, the ability of in vitro spinal cord slices to recapitulate many of the key pathological features of NMO provides an opportunity to address questions that cannot be easily studied using in vivo models, such as the role of individual cellular and soluble factors in the genesis of NMO lesions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, National Multiple Sclerosis Society (RG4320), and grants the National Institutes of Health (EY13574, DK35124, EB00415, DK86125, DK72517, HL73856).

References

- 1.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, et al. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:805–15. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarius S, Wildemann B. AQP4 antibodies in neuromyelitis optica: diagnostic and pathogenetic relevance. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:383–92. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lennon VA, Wingerchuk DM, Kryzer TJ, et al. A serum autoantibody marker of neuromyelitis optica: distinction from multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2004;364:2106–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17551-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lennon VA, Kryzer TJ, Pittock SJ, et al. IgG marker of optic-spinal multiple sclerosis binds to the aquaporin-4 water channel. J Exp Med. 2005;202:473–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucchinetti CF, Mandler RN, McGavern D, et al. A role for humoral mechanisms in the pathogenesis of Devic’s neuromyelitis optica. Brain. 2002;125:1450–61. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misu T, Fujihara K, Kakita A, et al. Loss of aquaporin 4 in lesions of neuromyelitis optica: distinction from multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2007;130:1224–34. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roemer SF, Parisi JE, Lennon VA, et al. Pattern-specific loss of aquaporin-4 immunoreactivity distinguishes neuromyelitis optica from multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2007;130:1194–205. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinson SR, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, et al. Pathogenic potential of IgG binding to water channel extracellular domain in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2007;69:2221–31. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000289761.64862.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi T, Fujihara K, Nakashima I, et al. Anti-aquaporin-4 antibody is involved in the pathogenesis of NMO: a study on antibody titre. Brain. 2007;130:1235–43. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarius S, Aboul-Enein F, Waters P, et al. Antibody to aquaporin-4 in the long-term course of neuromyelitis optica. Brain. 2008;131:3072–80. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cree BA, Lamb S, Morgan K, et al. An open label study of the effects of rituximab in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2005;64:1270–2. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159399.81861.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyamoto K, Kusunoki S. Intermittent plasmapheresis prevents recurrence in neuromyelitis optica. Ther Apher Dial. 2009;13:505–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2009.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett JL, Lam C, Kalluri SR, et al. Intrathecal pathogenic anti-aquaporin-4 antibodies in early neuromyelitis optica. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:617–29. doi: 10.1002/ana.21802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradl M, Misu T, Takahashi T, et al. Neuromyelitis optica: pathogenicity of patient immunoglobulin in vivo. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:630–43. doi: 10.1002/ana.21837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinoshita M, Nakatsuji Y, Kimura T, et al. Neuromyelitis optica: Passive transfer to rats by human immunoglobulin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;386:623–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinoshita M, Nakatsuji Y, Kimura T, et al. Anti-aquaporin-4 antibody induces astrocytic cytotoxicity in the absence of CNS antigen-specific T cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394:205–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saadoun S, Waters P, Bell BA, et al. Intra-cerebral injection of neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G and human complement produces neuromyelitis optica lesions in mice. Brain. 2010;133:349–61. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma T, Yang B, Gillespie A, et al. Generation and phenotype of a transgenic knockout mouse lacking the mercurial-insensitive water channel aquaporin-4. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:957–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stoppini L, Buchs PA, Muller D. A simple method for organotypic cultures of nervous tissue. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;37:173–82. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90128-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uzawa A, Mori M, Arai K, et al. Cytokine and chemokine profiles in neuromyelitis optica: significance of interleukin-6. Mult Scler. 2010;16:1443–52. doi: 10.1177/1352458510379247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marignier R, Nicolle A, Watrin C, et al. Oligodendrocytes are damaged by neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G via astrocyte injury. Brain. 2010;133:2578–91. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papadopoulos MC, Verkman AS. Aquaporin-4 and brain edema. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:778–84. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0411-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solenov EI, Vetrivel L, Oshio K, et al. Optical measurement of swelling and water transport in spinal cord slices from aquaporin null mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;113:85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00481-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC, Watanabe H, et al. Involvement of aquaporin-4 in astroglial cell migration and glial scar formation. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5691–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Binder DK, Yao X, Zador Z, et al. Increased seizure duration and slowed potassium kinetics in mice lacking aquaporin-4 water channels. Glia. 2006;53:631–6. doi: 10.1002/glia.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, Zhang H, Varrin-Doyer M, et al. Proinflammatory role of aquaporin-4 in autoimmune neuroinflammation. FASEB J. 2011;25:1556–66. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-177279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang B, Brown D, Verkman AS. The mercurial insensitive water channel (AQP-4) forms orthogonal arrays in stably transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4577–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dale DC, Boxer L, Liles WC. The phagocytes: neutrophils and monocytes. Blood. 2008;112:935–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-077917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saadoun S, MacDonald C, Waters P, et al. Neutrophil protease inhibition greatly reduces NMO-IgG-induced inflammation and myelin loss in mouse brain. 2011 (submitted) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlesinger LS, Horwitz MA. Phagocytosis of Mycobacterium leprae by human monocyte-derived macrophages is mediated by complement receptors CR1 (CD35), CR3 (CD11b/CD18), and CR4 (CD11c/CD18) and IFN-gamma activation inhibits complement receptor function and phagocytosis of this bacterium. J Immunol. 1991;147:1983–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rotshenker S. Microglia and macrophage activation and the regulation of complement-receptor-3 (CR3/MAC-1)-mediated myelin phagocytosis in injury and disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2003;21:65–72. doi: 10.1385/JMN:21:1:65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers CA, Gasque P, Piddlesden SJ, et al. Expression and function of membrane regulators of complement on rat astrocytes in culture. Immunology. 1996;88:153–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maranto J, Rappaport J, Datta PK. Regulation of complement component C3 in astrocytes by IL-1beta and morphine. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2008;3:43–51. doi: 10.1007/s11481-007-9096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimizu J, Hatanaka Y, Hasegawa M, et al. IFNβ-1b may severely exacerbate Japanese optic-spinal MS in neuromyelitis optica spectrum. Neurology. 2010;75:1423–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f8832e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.