Abstract

Friedreich’s ataxia (FRDA) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that has been linked to defects in the protein frataxin (Fxn). Most FRDA patients have a GAA expansion in the first intron of their Fxn gene that decreases protein expression. Some FRDA patients have a GAA expansion on one allele and a missense mutation on the other allele. Few functional details are known for the ~15 different missense mutations identified in FRDA patients. Here in vitro evidence is presented that indicates the FRDA I154F and W155R variants bind more weakly to the complex of Nfs1, Isd11, and Isu2 and thereby are defective in forming the four-component SDUF complex that constitutes the core of the Fe-S cluster assembly machine. The binding affinities follow the trend Fxn ~ I154F > W155F > W155A ~ W155R. The Fxn variants also have diminished ability to function as part of the SDUF complex to stimulate the cysteine desulfurase reaction and facilitate Fe-S cluster assembly. Four crystal structures, including the first for a FRDA variant, reveal specific rearrangements associated with the loss of function and lead to a model for Fxn-based activation of the Fe-S cluster assembly complex. Importantly, the weaker binding and lower activity for FRDA variants correlate with the severity of disease progression. Together, these results suggest Fxn triggers sulfur transfer from Nfs1 to Isu2, and that these in vitro assays are sensitive and appropriate for deciphering functional defects and mechanistic details for human Fe-S cluster biosynthesis.

Keywords: crystal, structure/Fe-S, cluster, biosynthesis/frataxin/Friedreich’s, ataxia/kinetics

Friedreich’s ataxia (FRDA) is an autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disease caused by reduced amounts of the protein frataxin (Fxn) (1). The loss of Fxn results in a complex phenotype that includes increased iron in the mitochondria, deficiencies in Fe-S cluster enzymes, and enhanced sensitivity to oxidative stress (2). FRDA patients typically present symptoms during adolescence such as progressive limb and gait ataxia and often die prematurely from cardiomyopathy. There is currently no cure. The majority (>95%) of FRDA patients are homozygous for an unstable GAA trinucleotide repeat expansion in the first intron of the FXN gene (3). The number of repeats range from 7 to 40 for normal individuals and from 66 to >1700 for FRDA patients (3, 4). Importantly, larger numbers of GAA repeats correlate with lower Fxn expression and an earlier age of disease onset (5, 6). A small fraction of FRDA patients are compound heterozygotes with an expanded GAA repeat affecting one allele and a missense or nonsense mutation affecting the other allele (7). For compound heterozygote patients, the Fxn protein levels do not necessarily correspond to the age of onset (3, 8).

Most researchers agree that Fxn has a critical role in iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster assembly (9, 10). Eukaryotic Fe-S cluster biosynthesis occurs in the matrix space of the mitochondria and involves at least a dozen proteins (11). [2Fe-2S]2+/1+ clusters and, possibly, [4Fe-4S]2+/1+ clusters are assembled on the monomeric Isu2 scaffold (12). Nfs1, which forms a functional complex with Isd11 (13–15), catalyzes the PLP-dependent breakdown of cysteine to alanine and produces a transient persulfide species on a mobile loop (16, 17). The sulfur from this persulfide species is then transferred to Isu2 and becomes the inorganic sulfide of the Fe-S clusters. After iron incorporation and Fe-S cluster synthesis, chaperones interact with the scaffold protein and assist in delivering intact Fe-S clusters to their apo targets (18–20). Many potential roles for Fxn in this process have been suggested, which is complicated by the presence of multiple Fxn proteolytic products (21–27). The 14 kDa monomeric form (referred to as Fxn in this manuscript) includes residues 81–210 and is commonly thought to function as an iron chaperone in Fe-S cluster biosynthesis (28). Both in vivo and in vitro data support pairwise physical interactions between eukaryotic Nfs1, Isd11, Isu1/2, and Fxn (13, 14, 29–33). Recently, biochemical evidence was provided for Nfs1, Isd11, and Isu2 (SDU) and Nfs1, Isd11, Isu2, and Fxn (SDUF) Fe-S cluster assembly complexes (34, 35). This work also identified Fxn as an allosteric activator of Fe-S cluster assembly that increases the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) for the cysteine desulfurase component of SDUF and the rate of Fe-S cluster biosynthesis (34).

The FXN missense mutations present in compound heterozygous patients likely cause at least partial defects in Fxn function that may provide additional insight into the role of Fxn in Fe-S cluster biosynthesis. Therefore, the human FRDA mutations I154F and W155R and related Fxn variants were investigated using our recently developed biochemical assays, combined with determination of X-ray crystal structures. The data indicated that these mutations and variants have defects in binding and activating the SDU complex. The relative effects of the I154F and W155R mutations in vitro correlate with the reported age of onset in patients. In addition, structure-function properties for the W155A, W155R and W155F variants contribute to a model for how Fxn triggers direct sulfur transfer from Nfs1 to Isu2 for Fe-S cluster assembly.

Experimental Procedures

Protein Preparation

The QuikChange method (Stratagene) was used to introduce point mutants (I154F, W155A, W155Rand W155F) into a pET11a plasmid containing human Fxn (Δ1–55) (34), and the mutation sites were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Plasmids containing the Fxn variants were individually transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3), and the cells were grown at 16 °C. Protein expression was induced at an OD600 of 0.6 with 0.5 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested 16 hours later and the Fxn variants were purified as previously described for native Fxn (34). The Fxn variants spontaneously truncate to a form that includes residues 82–210, based on N-terminal sequencing. The protein expression and purification of native Fxn, Isu2, and the Nfs1/Isd11 (SD) complex were performed as previously described (34). Protein concentrations for I154F, W155A, W155Rand W155F were estimated by their absorbance at 280 nm using extinction coefficients of 26030, 21430, 20340, and 21430 M−1cm−1, respectively.

Cysteine Desulfurase Activity Measurements

Reaction mixtures (800 µL) containing SD (0.5 µM), Isu2 (1.5 µM), PLP (10 µM), DTT (2 mM), Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 (5 µM), Fxn variants (1.5 µM), 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, and 250 mM NaCl were incubated in an anaerobic glovebox (10~14 °C) for 30 minutes (34, 36, 37). The cysteine desulfurase reactions were initiated by addition of 100 µM l-cysteine at 37 °C. Sulfide production was typically linear for the first 30 minutes and an incubation time of 10 minutes was chosen to generate sufficient product for detection. Assays were quenched by addition of 100 µl of 20 mM N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine in 7.2 N HCl and 100 µl of 30 mM FeCl3 in 1.2 N HCl, which also initiated the conversion of sulfide to methylene blue. After a twenty minute incubation at 37 °C, the absorption at 670 nm due to methylene blue formation was measured and compared with a Na2S standard curve to quantitate sulfide production. Units are defined as µmol sulfide/µmol SD per minute at 37 °C. The rates for the cysteine desulfurase reaction were also examined in the presence of 10 equivalents of Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 and with increasing amounts of Fxn to determine the number of equivalents, or the saturating amount, that are required to maximize the cysteine desulfurase activity. Batch one of Nfs1/Isd11 (cysteine desulfurase activity of 8.3 min−1) was used for the initial Michaelis-Menten kinetics for all of the variants and the determination of the binding constants for the native Fxn, I154F and W155R variants. A second batch of SD with lower activity (4.8 min−1) was used for determining the binding constants of the W155A and W155F Fxn variants.

An alternate cysteine desulfurase activity assay that monitored cysteine in solution (38) was used to verify the rate enhancement upon addition of Fxn variants. In this assay, reaction components were prepared at the same concentrations as the methylene blue assay (above), but at a final reaction volume of 50 µL. After incubation in the anaerobic glovebox for 30 minutes, the cysteine desulfurase reaction was initiated with the addition of 100 µM l-cysteine at 37 °C and quenched after 20 minutes using 50 µL acetic acid. Next, 50 µL of acid ninhydrin reagent 2 (stock solution was made by dissolving 25 mg ninhydrin in 600 µL acetic acid and 400 µL HCl) was added to the reaction mixtures, the sample were boiled for 10 minutes, rapidly cooled on ice, and diluted to 1 mL in 95% ethanol. The amount of cysteine reacted was quantitated using an extinction coefficient of 27.6 mM−1cm−1 at 560 nm (38) and compared to a sample that lacked enzyme.

Fe-S Cluster Formation on Isu2

Assay mixtures contained 8 µM SD, 24 µM Isu2, 24 µM Fxn variants, 5 mM DTT, 200 µM Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2, 100 µM l-cysteine, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, and 250 mM NaCl in a total volume of 0.2 mL. Isu2 was incubated with 5 mM DTT in 50 mM Tris pH 8, 250 mM NaCl in an anaerobic glovebox for 1 hour prior to mixing with the remaining assay components in an anaerobic cuvette. The reaction was initiated by injecting l-cysteine to a final concentration of 100 µM with a gas-tight syringe. Fe-S cluster formation was monitored at 456 nm at room temperature and then the first 1000 seconds were fit as first-order kinetics using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software). The rate was converted to the activity of Isu2 using an extinction coefficient of 9.8 mM−1cm−1 at 456 nm, previously determined for a presumed [2Fe-2S]2+ cluster bound to the human scaffold protein (39). Units are defined as the amount of Isu2 required to produce 1 µmol of [2Fe-2S]2+ cluster / µmol SDU complex per minute at 25 °C.

Michaelis-Menten Kinetics for Fxn Variants in SDUF Complex

The saturating amounts of the different Fxn variants were separately added to a standard reaction mixture (0.5 µM SD, 1.5 µM Isu2, 10 µM PLP, 2 mM DTT, 5 µM Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, and 250 mM NaCl) and incubated anaerobically for 30 minutes. The cysteine desulfurase activities were measured after initiating the reaction with the substrate l-cysteine (0.01 to 1 mM). Reaction rates as a function of cysteine concentration were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation using KaleidaGraph. The kcat was also measured as a function of Fxn concentration and fit as a type II allosteric activator (40) to equation [1] using KaleidaGraph. In equation [1], Kd is the binding

| [1] |

constant, kSDU is the kcat in the absence of Fxn, and kSDUF∞ is the kcat with saturated amounts of Fxn.

Protein Crystallization, Data Collection, and Refinement

Protein crystallization trials were initiated with hanging-drop vapor diffusion methods by mixing 2 µL of protein and 2 µL of reservoir solution, followed by incubation at 22 °C. Native Fxn at 15 mg/mL in a 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5 buffer that included 50 mM NaCl was crystallized after a one month incubation with 30% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol, 0.1 M sodium citrate pH 5.6, and 0.2 M ammonium acetate. The crystals were flash frozen without additional cryoprotection. The W155R variant was concentrated to 25 mg/mL in a 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5 buffer and then crystallized after a three-day incubation with 16% PEG monomethyl ether 2000 and 0.1 M MES pH 6.0. Single crystals were transferred to a cryoprotection solution that included the reservoir solution plus 16% ethylene glycol for ~1 minute and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Initial crystallization conditions for the W155A variant at 10 mg/mL in a 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 buffer included 2.0 M ammonium sulfate, 0.2 M potassium sodium tartrate tetrahydrate, and 0.1 M sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate pH 5.0. These initial crystals were used for microseeding experiments using the same reservoir solution except the ammonium sulfate concentration was lowered to 1.8 M. Crystals of the W155F variant at 10 mg/mL in a 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 buffer were generated after incubation for a few months with a reservoir solution of 0.2 M sodium acetate trihydrate, 0.1 M Tris hydrochloride pH 8.5, and 30% PEG 4000. Single crystals of the W155A and W155F variants were transferred to a cryoprotection solution that included their respective reservoir solutions plus 20% glycerol for ~0.5 minutes and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data for native Fxn, W155Rand W155F crystals were collected at SSRL beamline 7-1 (ADSC Quantum-315R CCD detector), whereas diffraction data for the W155A variant was collected at APS beamline 23-ID-D (MAR 300 CCD detector). The images were integrated and scaled with iMosflm (41) and Scala of the CCP4 suite (42). Phases were determined by molecular replacement with Phaser (43), using a previously refined structure of human Fxn (44) as a search model (PDB code: 1EKG). Difference electron density and omit maps were manually fit with the XtalView package (45), and refined in Refmac5 (46) with all of the diffraction data, except for 5% used for Rfree calculations (47). PDB codes are 3S4M for native Fxn, 3S5E for W155R3S5D for W155A, and 3S5F for W155F.

RESULTS

Diminished Allosteric Activation for Fxn Variants

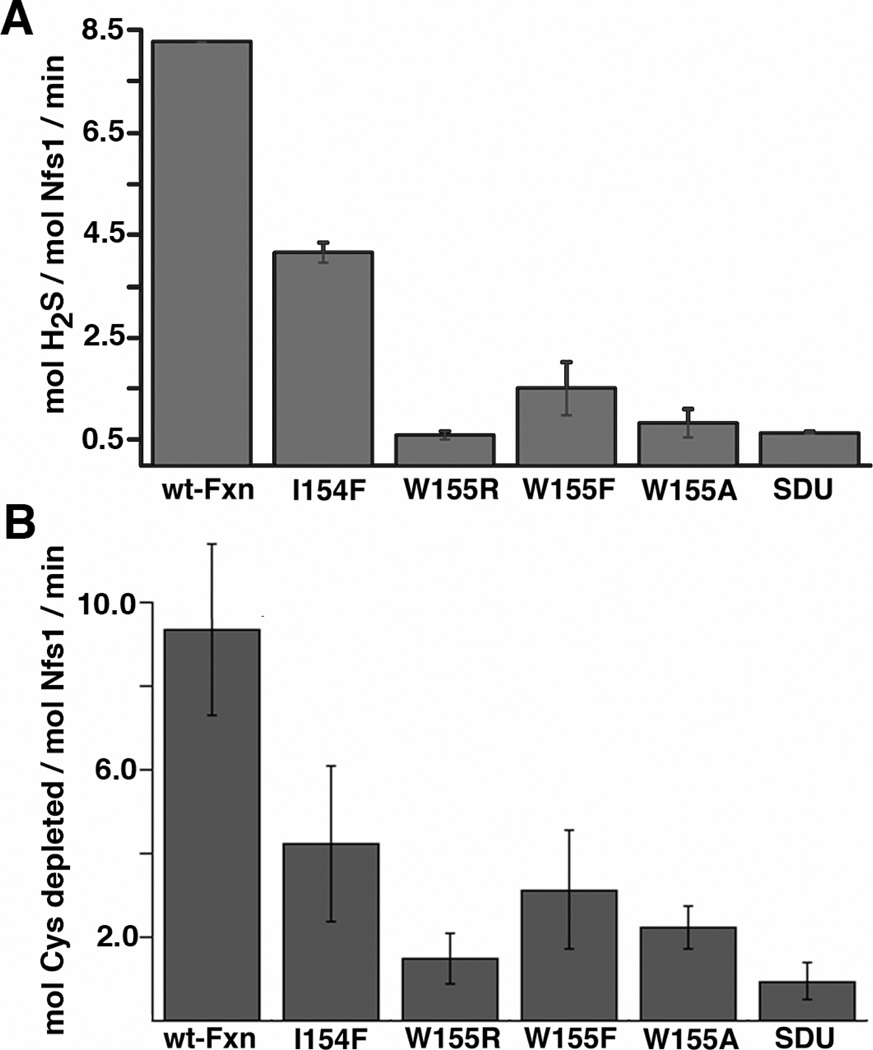

Previously, human Fxn was shown to bind to the Nfs1, Isd11, Isu2 (SDU) complex and to stimulate sulfide production and Fe-S cluster biosynthesis (34). Here we tested the ability of purified recombinant I154F and W155R FRDA mutants as well as the related W155A and W155F variants to activate the SDU complex. These biochemical assays were performed using 3 equivalents of each Fxn variant, a cysteine concentration of 0.1 mM, which was chosen to mimic physiological conditions (48), and 10 equivalents of ferrous iron, which further stimulates the rate of sulfide production for the SDUF complex (34). Each of the mutants exhibited a lower level of activation than native Fxn (Fxn > I154F > W155F > W155A > W155R), with the W155R mutation being most similar to a SDU sample that lacked Fxn (Fig. 1A and Table 1). A separate control assay monitored the depletion of cysteine and confirmed the Fxn-based activation and the diminished activity for the Fxn variants (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Fxn variants show diminished ability to activate cysteine desulfurase activities for the Fe-S assembly complex. Cysteine desulfurase activity was determined spectrophotometrically in the presence of 1 equivalent of the Nfs1/Isd11 complex, 3 equiv of each Fxn variants, 3 equiv of Isu2, and 10 equiv. of ferrous iron. A) Activity was determined by converting generated sulfide to methylene blue. B) Activity was determined by reacting cysteine in solution with ninhydrin. Error bars are for at least three independent measurements.

Table 1.

The Rate of Fe-S cluster formation and Binding and Rate Constants for Nfs1 Activity with Fxn Variants

| Complex | Nfs1 activity (min−1) |

Fe-S cluster formation (min−1) |

Fxn Kd (µM) |

kcat (min−1) | KMCys(mM) |

kcat/KM (M−1s−1) |

Age of onset1 |

Fxn expression1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDU + Fxn2 | 8.25 ± 0.90 | 12.3 ± 0.4 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 9800 ± 1700 | NA | 100 |

| SDU + I154F | 4.14 ± 0.20 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 0.63 ± 0.14 | 6.6 ± 0.4 | 0.025 ± 0.004 | 4400 ± 800 | 16 | 18 |

| SDU + W155R | 0.60 ± 0.07 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 6.73 ± 1.28 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.013 ± 0.003 | 2300 ± 500 | 4 | 18 |

| SDU + W155A | 0.83 ± 0.28 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 6.12 ± 1.36 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 0.012 ± 0.003 | 5600 ± 1600 | NA | NA |

| SDU + W155F | 2.09 ± 0.51 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 1.78 ± 0.31 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 0.018 ± 0.003 | 4100 ± 800 | NA | NA |

| SDU2 | 0.65 ± 0.02 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | NA | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 25 ± 3 | NA | NA |

Diminished Fe-S Cluster Biosynthesis for Fxn Variants

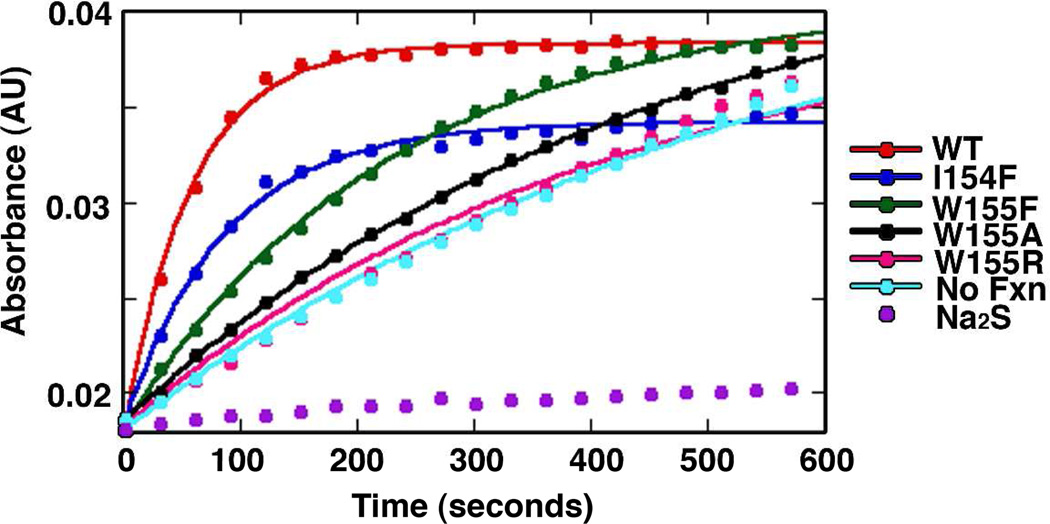

Next, the rate of Fe-S cluster assembly on Isu2 was determined for each Fxn variant by monitoring increases in absorbance at 456 nm (39, 49). The SDUF complex with native Fxn exhibited an activity of 12.3 µmol [2Fe-2S] / µmol SDU per minute (Fig. 2), which is similar to the 6 µmol [2Fe-2S] / µmol per minute reported previously using the Thermotoga maritima NifS enzyme as the sulfur source and slightly different experimental conditions (39). All Fxn variants displayed lower Fe-S cluster assembly activities than native Fxn, with the W155R variant rate similar to a sample that lacked Fxn (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Control assays with 100 µM sulfide rather than cysteine exhibited significantly slower rates than any of the other samples indicating that efficient Fe-S formation was not mediated by sulfide in solution (Fig. 2). Overall, the relative activities for the different Fxn variants in the Fe-S cluster biosynthetic assay mirrored their ability to activate the cysteine desulfurase component of the assembly complex (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Fxn variants exhibit diminished Fe-S cluster assembly activity. Fe-S cluster formation was monitored by an increase in absorbance at 456 nm as a function of time. Assays included Nfs1/Isd11 with 3 equivalents of Isu2 and 3 equivalents of Fxn variants. The lines through the data are the fits using first-order kinetics. Control samples without Fxn and with Na2S rather than cysteine are included.

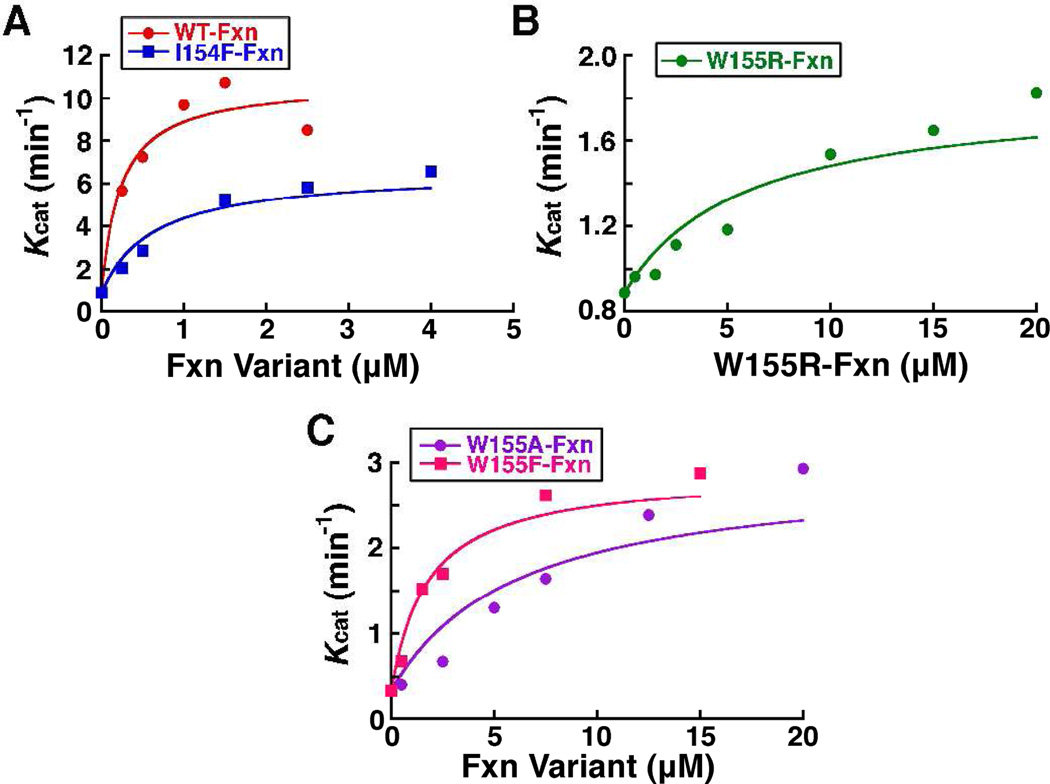

Binding Constants for Fxn Variants

The activation defects of the Fxn variants could be due to defects in variant binding to SDU. We therefore determined binding constants for the Fxn variants by measuring the rates of sulfide production as a function of L-cysteine at different concentrations of added Fxn. The resulting kcat values were plotted against the Fxn concentration and the data were fit as a type II allosteric activator to equation [1] (Fig. 3). A Kd of 0.22 µM was determined for native Fxn binding to SDU, which was similar to the 0.4 µM binding constant reported for the association of the Fxn homolog CyaY to the IscS/IscU complex (50); the prokaryotic IscS/IscU complex is analogous to the eukaryotic SDU complex. Each Fxn variant exhibited weaker binding to the SDU complex than native Fxn by a factor of 3 (I154F), 8 (W155F), 28 (W155A), and 30 (W155R) (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

Figure 3.

Determination of binding constants for Fxn variants. The kcat was determined at different Fxn concentrations. The lines through the data are the fits as a Type II allosteric activator to equation [1]. The R2 values are 0.925, 0.947, 0.899, 0.882, and 0.964 for the Fxn, I154F, W155RW155A, and W155F variants, respectively.

Kinetic Parameters for Fxn Variants

The Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters for the cysteine desulfurase reaction were determined for the SDUF complex with the different Fxn variants. To compensate for weaker binding of the different Fxn mutants, cysteine desulfurase activities were measured as a function of added Fxn. The cysteine desulfurase activity maximized, or saturated, after the addition of 3 equivalents of Fxn, 8 equivalents of I154F, 30 equivalents of W155F, 40 equivalents of W155A, and 40 equivalents of W155R (data not shown). Saturating amounts of the different Fxn variants were then added to the SDU complex and the rates of the cysteine desulfurase reaction were measured as a function of the L-cysteine concentration. The four Fxn variants exhibited lower kcat values, but similar KM values compared to native Fxn (Table 1). The most significant change was observed for the W155R variant, which lowered the kcat/KM by a factor of four.

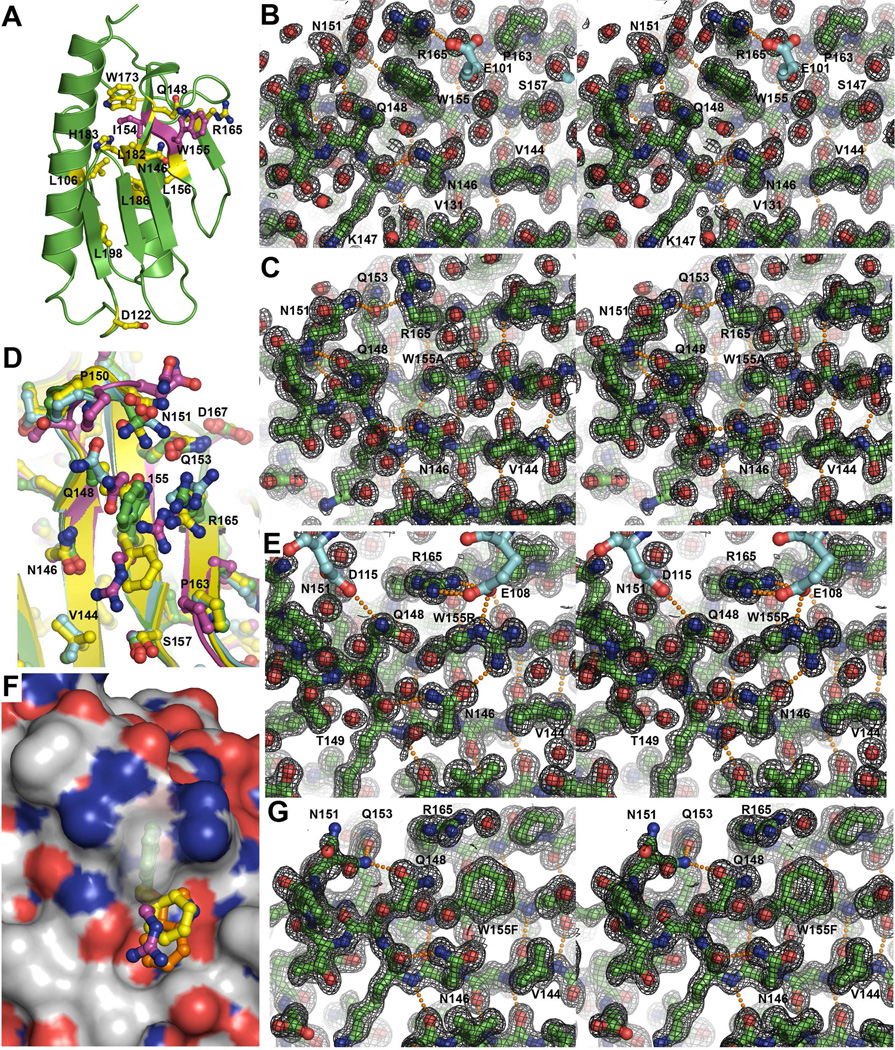

Crystal Structures of Fxn Variants

High-resolution crystal structures were determined for native Fxn, plus the W155RW155A, and W155F variants to understand the structural basis for the altered functional properties (Table 2). The 1.30 Å resolution native human Fxn structure contains N- and C-terminal α-helices that pack against an antiparallel β-sheet (Fig. 4A), as previously described (44, 51). Overall, the structures of the W155A, W155Rand W155F variants displayed very similar backbone conformations with each exhibiting a Cα RMSD of < 0.5 Å compared to native Fxn. The primary structural differences were due to side-chain conformational changes near the mutation sites.

Table 2.

X-ray Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| Fxn Variants | WT | W155A | W155R | W155F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | SSRL BL7-1 | APS BL23-ID-D | SSRL BL7-1 | SSRL BL7-1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97945 | 1.03315 | 0.97945 | 0.97945 |

| Space Group | P212121 | C2 | P212121 | P21 |

| Unit cell (Å and °) | 42.9, 44.8, 69.0 90°, 90°, 90° |

87.5, 32.3, 44.8 90°, 91.4°, 90° |

38.9, 49.2, 67.1 90°, 90°, 90° |

47.7, 53.1, 48.5 90°, 112.3°, 90° |

| Resolution (Å) | 44.86-1.30 | 44.797-1.50 | 39.68-1.31 | 34.27-1.50 |

| Outer shell (Å) | 1.37-1.30 | 1.58-1.50 | 1.38-1.31 | 1.58-1.50 |

| Observations | 258690 | 147672 | 476216 | 237470 |

| Unique Observations | 33576 | 20101 | 31647 | 35399 |

| Redundancy | 7.7 | 7.3 | 15.0 | 6.7 |

| Completeness (%)* | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.3 (98.6) | 99.8 (99.7) | 97.7 (97.2) |

| Mean I/(σI)* | 14 (2.6) | 12.0 (6.6) | 22.2 (5.6) | 13.8 (2.2) |

| Rsym (%)*† | 8.2 (62.4) | 13.8 (48.3) | 6.4 (41.3) | 7.2 (88.4) |

| Refinement | ||||

| Residues not in model | 82–88, 210 | 82–89 | 82–87, 209–210 | 82–84, 210 |

| Solvent atoms | 201 | 101 | 169 | 138 |

| Ligand | SO4 | Mg | Mg | |

| Rwork/Rfree (%)‡ | 15.3/18.7 | 16.9/19.2 | 15.1/19.7 | 16.4/21.3 |

| r.m.s.d. bond lengths (Å) | 0.032 | 0.029 | 0.023 | 0.023 |

| r.m.s.d. bond angles (°) | 2.7 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | ||||

| Protein | 16.8 | 9.9 | 13.2 | 22.2 |

| Water | 60 | 34.6 | 60 | 40 |

| Ramachandran (%) | ||||

| Most favored | 93.4 | 91.5 | 93.4 | 94.8 |

| Additional allowed | 6.6 | 8.5 | 6.6 | 5.2 |

| Generous | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Disallowed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PDB code | 3S4M | 3S5D | 3S5E | 3S5F |

Values in parentheses are the statistics for the highest resolution shell of data

Rsym = S | Ihkl − <I> | / S <I>, where <I> is the average individual measurement of Ihkl.

Rwork = (S |Fobs−Fcalc|) / S|Fobs|, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively. Rfree is calculated the same as Rwork, but from the data (5%) that were excluded from the refinement.

Figure 4.

Crystallographic structures of Fxn and the W155A, W155Rand W155F variants. A) FRDA missense mutations (yellow) mapped onto the structure of Fxn. The I154F and W155R mutants are shown in magenta. Stereo images with 2Fo-Fc electron density contoured at 1 sigma for (B) Fxn; (C) W155A; (E) W155R; and (G) W155F structures. Symmetry molecules are shown without electron density in cyan. Panel D displays an overlay of native Fxn (green), W155A (cyan), W155R (magenta), and W155F (yellow) structures. Panel F displays a molecular surface of native Fxn along with the side-chain for the W155R (magenta), W155F (yellow), and a modeled conformer of W155 (orange). Residue W155 is shown with a semi-transparent molecular surface.

In the native human Fxn structure, electron density maps revealed that the W155 side chain is constrained by a hydrogen bond between the indole ring nitrogen and the side-chain oxygen of Q153 as well as van der Waals interactions with the side chains of R165 and Q148 (Fig. 4B). Q153 also forms a hydrogen bond to D167. The position of R165 is reinforced in the crystal structure by a hydrogen bond to residue E101 of a symmetry molecule in the P212121 space group. Residue Q148 is the first residue in a class I-αRS α-turn (52) that connects β-strands 3 and 4, and its side-chain oxygen forms a hydrogen bond to the nitrogen of the N151 side-chain. Residues I154 and L156 are oriented in the opposite direction on β-strand 4 compared to W155, and make up part of the hydrophobic core of Fxn. Notably, there is a water-filled pocket on the Fxn surface near W155 that is on the opposite face of β-strand 4 from L156 (Figure 4B).

The W155A variant, which crystallized in the C2 space group, resulted in minor side chain rearrangements for residues N151 and R165 to form hydrogen bonds with Q153 (Fig. 4C). These new hydrogen bonds replaced the hydrogen bond to Q153 that was eliminated due to the loss of the indole ring. Residue Q153 maintained the native Fxn conformation and hydrogen bond to the D167 side-chain. A rearrangement of the N151 side-chain to interact with Q153 resulted in loss of the hydrogen bond between the N151 and Q148 side-chains observed in the native Fxn structure (Fig. 4D). Instead, the Q148 side-chain underwent a slight rearrangement to form a hydrogen bond to the backbone amide of residue 151 (Fig. 4C).

The FRDA mutation W155R crystallized in the P212121 space group and exhibited a significant side-chain reorganization compared to native Fxn (Fig. 4D). A minor rearrangement for the side-chains of residues Q148 and N151 resulted in formation of hydrogen bonds with D115 of a symmetry molecule, whereas a conformational change for residue R165 resulted in formation of a salt bridge with E108 of a symmetry molecule (Fig. 4E). The FRDA mutant underwent a side-chain rotation for residue 155 to fill a cavity on the surface of Fxn (Fig. 4F) and formed hydrogen bonds to N146 and to E108 of a symmetry molecule. A ~1.5 Å translation of the Q148- N151 α-turn between the third and fourth β-strand was also observed (Fig. 4D).

The W155F variant crystallized in the P21 space group with two Fxn molecules in the asymmetric unit. The W155F structure revealed rearrangements to form a hydrogen bond between residues Q153 and N151 (Fig. 4G). The electron density for N151 indicated multiple side-chain conformations. A conformational change for residue R165 resulted in the formation of a hydrogen bond to the D139 carbonyl oxygen of an adjacent Fxn molecule (not shown). The W155F side-chain exhibited a rotated conformer compared to native Fxn and the phenylalanine filled the same cavity as the W155R side-chain (Fig. 4D and 4F). In addition, residue V144 underwent a rearrangement to better pack against the W155F side-chain. Together, these crystal structures showed minor rearrangements outside of the mutation site (Fig. 4D) and provided hints to the correlation between structural changes and the altered Fxn binding affinity and ability to function as an allosteric activator.

DISCUSSION

FXN missense mutations present in compound heterozygous patients were investigated to provide additional insight into the role of Fxn in Fe-S cluster biosynthesis, as these missense mutations likely cause at least partial defects in Fxn function. Here the results showed that the FRDA missense mutations I154F and W155R and the related W155 variants W155A and W155F are impaired allosteric activators both for sulfide formation and for Fe-S cluster biosynthesis by the SDU complex. For the clinical mutations, W155R was much more defective in vitro than I154F. The clinical phenotype for patients with the I154F missense mutation and a GAA expansion are indistinguishable from individuals that are homozygous for the GAA repeat expansion (1, 6, 7). In contrast, individuals with the W155R missense mutation and a GAA expansion exhibit early onset FRDA pathogenesis (3, 53). Thus, the level of severity of the defects in vitro correlates with the clinical phenotypes.

In patients, several lines of evidence suggest that the I154F and W155R missense mutations could be compromised due to low in vivo protein levels similar to the effect of GAA repeat expansion (8, 54): the I154F and W155R mutants in vitro have decreased thermodynamic stability and a tendency to precipitate upon iron binding (51, 55, 56); the I154F mutation may (24) or may not (57) have slower in vivo maturation kinetics; and residues I154 and W155 are near K147, which is important for the ubiquitin-based degradation of Fxn (58).

Regardless of any defects in protein concentrations, previous in vivo data as well as in vitro data presented here suggest that the I154F and W155R additionally possess biochemical defects. The I154F mutation rescues the lethality of FXN−/− mice, but also resulted in a FRDA-like phenotype that included loss of iron-sulfur cluster enzyme activity (59). The Saccaharomyces cerevisiae yfh1 alleles W131A, W131F, and I130A (equivalent to human FXN variants W155A, W155F, and I154A) also cause cellular growth defects on high-iron media and diminish aconitase activity similar to a deletion of YFH1 that could be rescued by overexpression of yfh1-W131F, but not yfh1-W131A or yfh1-I130A (60). The Fxn variants tested here all had equivalent defects in the cysteine desulfurase (Fig. 1) and Fe-S cluster assembly (Fig. 2) assays relative to native Fxn, ranging from ~2-fold for I154F to ~14-fold for W155R (Table 1). As these in vitro assays cannot distinguish between mutants that do not bind the SDU complex from those that bind but cannot activate, the binding constants of the Fxn variants were determined (the I154F, W155F, W155A, and W155R variants bind 3-, 8-, 28-, and 30-fold weaker than native Fxn, respectively; Table 1). Weaker binding is consistent with previous pull down assays that reveal I154F and W155R Fxn variants have diminished binding to Isd11 (30), that the I154F mutant, but not the W155A or W155R variants, is capable of interacting with Nfs1 and IscU (35), and S. cerevisiae studies that indicate W131F, but not W131A, is able to interact with Isu1 (60). In addition, the recombinant Fxn variants exhibited 2- to 4-fold decreases in kcat/KM for cysteine turnover by the SDUF complex (Table 1). Weaker or non-productive binding by these mutants would exacerbate any effects of lower protein levels.

The Fxn binding constant and protein concentration in the mitochondria appear appropriately matched for a Fxn role in regulating Fe-S cluster biosynthesis. Although Fxn levels in human lymphocytes (61, 62), and buccal cells or whole blood (8) are known (in pg Fxn/µg total protein), the concentration of Fxn inside mitochondria from any human cell type, to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported. The concentration of Fxn has been estimated in yeast mitochondria to be 0.3 µM (63), based on global expression studies (64). Assuming this 0.3 µM frataxin concentration estimate is also accurate for human mitochondria, then the fraction of Fxn bound in the SDUF complex (equation [2]) with a Kd of 0.22 µM (Table 1) would be 58%. The concentration

| [2] |

of Fxn for FRDA patients was determined to be 4–29% (65), 29% (66), 21% (8), 27% (62), and 36% (54) of control Fxn levels. Lowering the Fxn level, for example, to ~25% of the normal Fxn concentration would decrease the activated SDUF fraction from 58% to 25%. Thus, the measured binding constant for native Fxn and the estimated level of Fxn in the mitochondria could explain the loss of Fe-S cluster activity for individuals with the GAA repeat expansion.

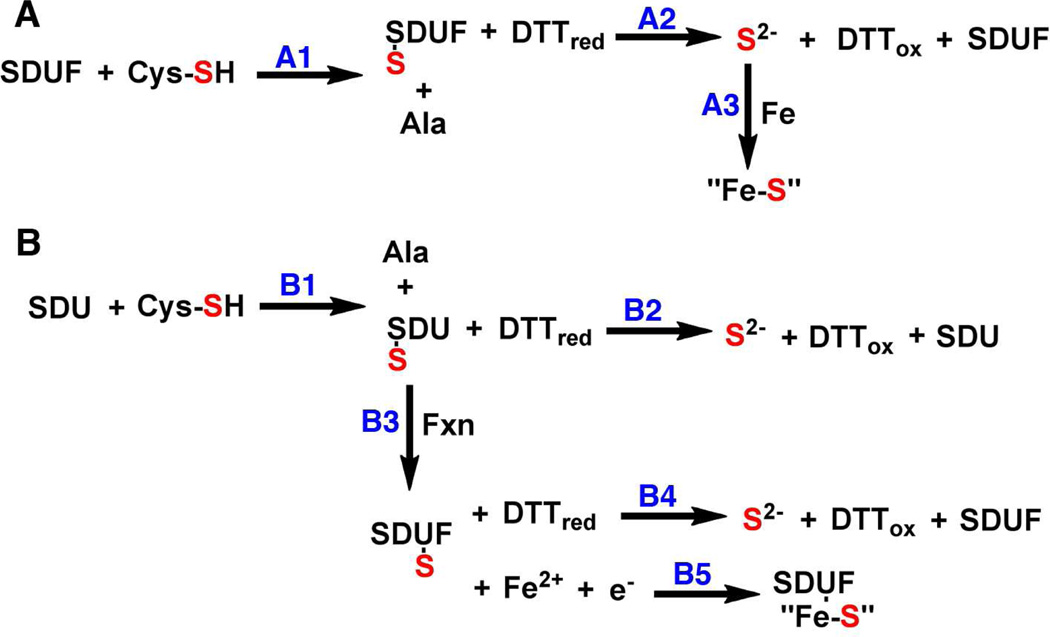

Interestingly, our results indicate that the cysteine desulfurase and Fe-S cluster activities appear to be correlated for the Fxn variants (Table 1). One explanation for this correlation is that the different Fxn variants affect the rate of persulfide cleavage from Nfs1 (Fig. 5A reaction A2) and the released sulfide combines with iron (in solution or on Isu2) to form Fe-S clusters (reaction A3). Two pieces of data argue against this model. First, substitution of 100 µM sulfide for the 100 µM cysteine in the Fe-S cluster [2] assembly assay resulted in no significant increase in absorbance in the time frame of the experiment (Fig. 2), inconsistent with reaction A3 (Fig. 5A). Second, the Fe-S assembly activities (determined at 25 °C) are faster than the cysteine desulfurase activities (measured at 37 °C) (Table 1). In scheme A, the rate of sulfide production reaction A2) is required to be as fast or faster than that for Fe-S cluster formation reaction A3). Together this data indicates the correlation for the cysteine desulfurase and Fe-S assembly activities is not due to differences in the ability of Fxn variants to facilitate DTT-induced release of sulfide from Nfs1.

Figure 5.

Alternate schemes for in vitro sulfide production and Fe-S cluster assembly by the human assembly system. See text for details.

An alternate explanation for this activity correlation is that Fxn induces rapid internal sulfur transfer from Nfs1 to Isu2. In this scheme (Fig. 5B), cysteine is converted to alanine by the SDU complex (reaction B1) and the resulting persulfide species on Nfs1 can be cleaved by DTT to produce sulfide (reaction B2). In the presence of Fxn, sulfur is transferred from the mobile loop on Nfs1 to generate a persulfide species on Isu2 (reaction B3). This persulfide species on Isu2 can then be reductively cleaved by DTT (reaction B4) or used for Fe-S cluster assembly (reaction B5). The Fxn-induced rate enhancement for the cysteine desulfurase reaction can be explained if Fxn induces rapid sulfur transfer from Nfs1 to Isu2 (reaction B3) and DTT cleavage of the persulfide on Isu2 (reaction B4) is faster than on Nfs1 (reaction B2). Moreover, the activity correlation for the Fxn variants could be explained by the common Fxn-induced sulfur transfer step (reaction B3) that depends on both Fxn binding and a Fxn-induced conformational change. In this model, the rate of Fe-S cluster formation (reaction B5) must be faster than sulfide release from Isu2 (reaction B4); otherwise the added DTT in the Fe-S cluster assay would cleave the persulfide prior to Fe-S cluster formation. Together the kinetic data suggest that Fxn affects the internal sulfur transfer (reaction B3) rather than the DTT-induced cleavage of a persulfide on Nfs1 (reaction A2). We therefore hypothesize that Fxn binding induces a conformational change that facilitates rapid sulfur transfer from Nfs1 to Isu2 for Fe-S cluster formation.

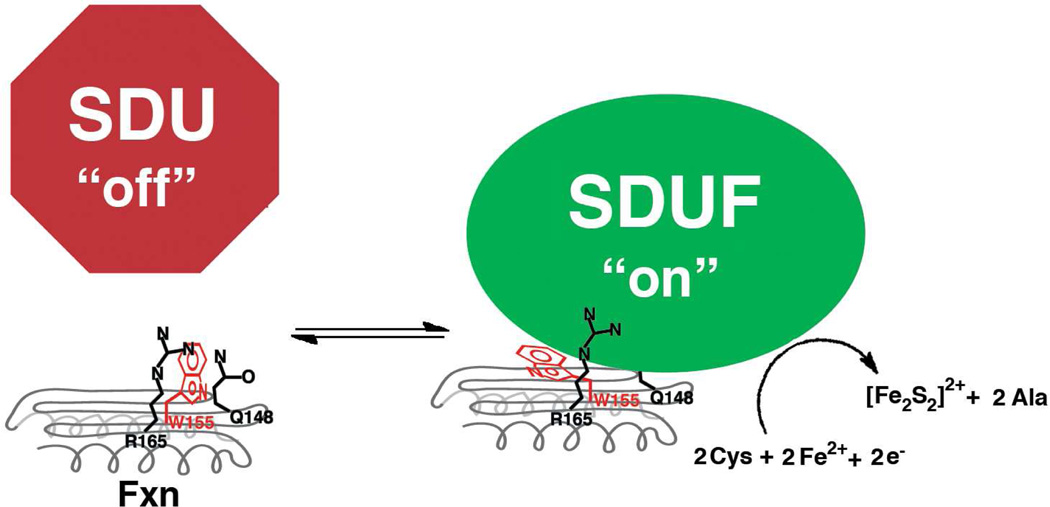

There is currently limited structural data for how Fxn interacts with the other components of the human Fe-S assembly complex. Here a comparison of native Fxn and W155A (Fig. 4B, 4C and 4D) variants revealed very minor structural differences, yet these variants have a 28-fold difference in binding affinity (Table 1). Tryptophan residues often participate in protein-protein interfaces through hydrophobic, π-π, and cation-π interactions (67, 68). W155 is stacked in a positively charged pocket on the surface of Fxn between R165 and Q148 (Fig. 4B and 4F). The W155A substitution diminishes a W155-dependent protrusion on the surface of Fxn (Fig. 4C) that could be part of the Fxn binding interface with the SDU complex. Alternately, W155 could undergo a conformational change, which would have minor steric clashes for an energetically favorable rotomer (Fig. 4F; orange), and fill a pocket on the surface of the protein that is on the opposite face of the β-sheet from L144 (Fig. 4B), which is occupied by the side-chain of residue 155 in the W155R (Fig. 4E) and W155F (Fig 4G) structures. This induced-fit model (Fig. 6) might provide a protein partner with opportunities for hydrophobic and π-stacking interactions with the indole ring of W155 that are not available in the native structure of Fxn. We hypothesize that the aromatic ring for W155 (and W155F) occupies this surface pocket on Fxn and interacts with a residue of SDU through π-π or cation- π interactions. In our working model, this interaction is important for both Fxn binding to the SDU complex and also in favoring a conformational change in Isu2 that positions a cysteine residue appropriately for sulfur transfer from Nfs1. The positively charged pocket between Fxn residues R165 and Q148 could form a separate interaction site in the Fe-S assembly complex. This scenario would explain the relative binding affinities of the W155 variants (Fxn > W155F > W155A, W155R), but requires evaluation through additional structure-function experiments. This hypothesis is also consistent with NMR studies of the Yfh1 homolog that suggests the Isu1 scaffold protein interacts primarily with residues of the N-terminal α-helix and the first three β-strands (69). Notably, the equivalent of Fxn W155R for the E. coli system, CyaY W61Ralso compromises protein function, despite the fact that CyaY is proposed to function as a suppressor rather than an activator of Fe-S cluster biosynthesis (70). Together these results highlight the importance of W155 in the SDU-Fxn interface and the differing roles Fxn-like regulators in the prokaryotes and eukaryotes that require further investigation.

Figure 6.

Cartoon of induced-fit model for Fxn binding and activating the SDU complex.

In summary, we provide evidence that Fxn functions as a positive allosteric activator that may regulate human Fe-S cluster biosynthesis. The measured Fxn binding constant is similar to the estimated concentration of Fxn in mitochondria, which allows changes in Fxn levels to readily switch the Fe-S assembly complex on or off. The ~3–5 fold decrease in Fxn levels measured for FRDA patients would be expected to greatly decrease the amount of activated Fe-S assembly complex and explain the observed loss of activity for Fe-S containing enzymes in vivo. The FRDA W155R and I154F missense mutants exhibit decreased catalytic efficiency as allosteric activators and weaker binding to the Fe-S assembly complex that are consistent with the more severe pathogenesis of the W155R mutation. In our working model, Fxn undergoes a conformational change at residue W155 that triggers sulfur transfer from Nfs1 to Isu2 for Fe-S cluster assembly. Future studies are aimed at understanding the molecular basis for Fxn-induced sulfur transfer and providing additional mechanistic details for human Fe-S cluster biosynthesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Chris Putnam and James Vranish for helpful discussion and suggestions, Andrew Winn for making the W155F and W155A variants and assisting in crystal optimization, and Nick Fox for assistance in the ninhydrin experiments. Start-up funds from Texas A&M University are gratefully acknowledged. This project was supported in part by grant A-1647 from the Robert A. Welch foundation and grant 11BGIA5710009 from the American Heart Association. Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Abbreviations

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- FRDA

Friedreich’s ataxia

- Fxn

frataxin

- HEPES

N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N’-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PLP

pyridoxal-5’-phosphate

- S. cerevisiae

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- SD

Nfs1 Isd11 protein complex

- SDU

Nfs1, Isd11, Isu2 protein complex

- SDUF

Nfs1, Isd11, Isu2 and frataxin protein complex

- Tris

Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by Texas A&M University, grant A-1647 from the Robert A. Welch foundation and grant 11BGIA5710009 from the American Heart Association.

References

- 1.Campuzano V, Montermini L, Moltè MD, Pianese L, Cossee M, Cavalcanti F, Monros E, Rodius F, Duclos F, Monticelli A, Zara F, Cañizares J, Koutnikova H, Bidichandani SI, Gellera C, Brice A, Trouillas P, De Michele G, Filla A, De Frutos R, Palau F, Patel PI, Di Donato S, Mandel JL, Cocozza S, Koenig M, Pandolfo M. Friedreich's ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science. 1996;271:1423–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5254.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmucker S, Puccio H. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of Friedreich Ataxia to develop therapeutic approaches. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R103–R110. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santos R, Lefevre S, Sliwa D, Seguin A, Camadro J-M, Lesuisse E. Friedreich's Ataxia: Molecular Mechanisms, Redox Considerations and Therapeutic Opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:651–690. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schöls L, Amoiridis G, Przuntek H, Frank G, Epplen JT, Epplen C. Friedreich's ataxia. Revision of the phenotype according to molecular genetics. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 12):2131–2140. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.12.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dürr A, Cossee M, Agid Y, Campuzano V, Mignard C, Penet C, Mandel JL, Brice A, Koenig M. Clinical and genetic abnormalities in patients with Friedreich's ataxia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1169–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610173351601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filla A, De Michele G, Cavalcanti F, Pianese L, Monticelli A, Campanella G, Cocozza S. The relationship between trinucleotide (GAA) repeat length and clinical features in Friedreich ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:554–560. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cossee M, Dürr A, Schmitt M, Dahl N, Trouillas P, Allinson P, Kostrzewa M, Nivelon-Chevallier A, Gustavson KH, Kohlschütter A, Müller U, Mandel JL, Brice A, Koenig M, Cavalcanti F, Tammaro A, De Michele G, Filla A, Cocozza S, Labuda M, Montermini L, Poirier J, Pandolfo M. Friedreich's ataxia: point mutations and clinical presentation of compound heterozygotes. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:200–206. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199902)45:2<200::aid-ana10>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutsch EC, Santani AB, Perlman SL, Farmer JM, Stolle CA, Marusich MF, Lynch DR. A rapid, noninvasive immunoassay for frataxin: Utility in assessment of Friedreich ataxia. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;101:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muhlenhoff U, Richhardt N, Ristow M, Kispal G, Lill R. The yeast frataxin homolog Yfh1p plays a specific role in the maturation of cellular Fe/S proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2025–2036. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.17.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stehling O, Elsässer H, Brückel B, Muhlenhoff U, Lill R. Iron-sulfur protein maturation in human cells: evidence for a function of frataxin. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:3007–3015. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouault TA, Tong W-H. Iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis and human disease. Trends Genet. 2008;24:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster MW, Mansy SS, Hwang J, Penner-Hahn JE, Surerus KK, Cowan JA. A Mutant Human IscU Protein Contains a Stable [2Fe2S]2+ Center of Possible Functional Significance. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6805–6806. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adam AC, Bornhövd C, Prokisch H, Neupert W, Hell K. The Nfs1 interacting protein Isd11 has an essential role in Fe/S cluster biogenesis in mitochondria. Embo J. 2006;25:174–183. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi Y, Ghosh M, Tong W-H, Rouault TA. Human ISD11 is essential for both iron-sulfur cluster assembly and maintenance of normal cellular iron homeostasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3014–3025. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiedemann N, Urzica E, Guiard B, Müller H, Lohaus C, Meyer HE, Ryan MT, Meisinger C, Muhlenhoff U, Lill R, Pfanner N. Essential role of Isd11 in mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster synthesis on Isu scaffold proteins. Embo J. 2006;25:184–195. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng L, White RH, Cash VL, Jack RF, Dean DR. Cysteine desulfurase activity indicates a role for NIFS in metallocluster biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2754–2758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lill R. Function and biogenesis of iron-sulphur proteins. Nature. 2009;460:831–838. doi: 10.1038/nature08301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoff KG, Silberg JJ, Vickery L. Interaction of the iron-sulfur cluster assembly protein IscU with the Hsc66/Hsc20 molecular chaperone system of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7790–7795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130201997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uhrigshardt H, Singh A, Kovtunovych G, Ghosh M, Rouault TA. Characterization of the human HSC20, an unusual DnaJ type III protein, involved in iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3816–3834. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Füzéry A, Tonelli M, Ta D, Cornilescu G, Vickery L, Markley J. Solution Structure of the Iron-Sulfur Cluster Cochaperone HscB and Its Binding Surface for the Iron-Sulfur Assembly Scaffold Protein IscU. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9394–9404. doi: 10.1021/bi800502r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavadini P, Adamec J, Taroni F, Gakh O, Isaya G. Two-step processing of human frataxin by mitochondrial processing peptidase. Precursor and intermediate forms are cleaved at different rates. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41469–41475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006539200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmucker S, Argentini M, Carelle-Calmels N, Martelli A, Puccio H. The in vivo mitochondrial two-step maturation of human frataxin. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3521–3531. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long S, Jirku M, Ayala FJ, Lukes J. Mitochondrial localization of human frataxin is necessary but processing is not for rescuing frataxin deficiency in Trypanosoma brucei. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13468–13473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806762105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koutnikova H, Campuzano V, Koenig M. Maturation of wild-type and mutated frataxin by the mitochondrial processing peptidase. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1485–1489. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.9.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branda SS, Cavadini P, Adamec J, Kalousek F, Taroni F, Isaya G. Yeast and human frataxin are processed to mature form in two sequential steps by the mitochondrial processing peptidase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22763–22769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Condo I, Ventura N, Malisan F, Rufini A, Tomassini B, Testi R. In vivo maturation of human frataxin. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1534–1540. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon T, Dizin E, Cowan JA. N-terminal iron-mediated self-cleavage of human frataxin: regulation of iron binding and complex formation with target proteins. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2007;12:535–542. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stemmler TL, Lesuisse E, Pain D, Dancis A. Frataxin and mitochondrial Fe-S cluster biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26737–26743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.118679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerber J, Muhlenhoff U, Lill R. An interaction between frataxin and Isu1/Nfs1 that is crucial for Fe/S cluster synthesis on Isu1. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:906–911. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shan Y, Napoli E, Cortopassi GA. Mitochondrial frataxin interacts with ISD11 of the NFS1/ISCU complex and multiple mitochondrial chaperones. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:929–941. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramazzotti A, Vanmansart V, Foury F. Mitochondrial functional interactions between frataxin and Isu1p, the iron-sulfur cluster scaffold protein, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2004;557:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01498-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon T, Cowan J. Iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis. Characterization of frataxin as an iron donor for assembly of [2Fe-2S] clusters in ISU-type proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6078–6084. doi: 10.1021/ja027967i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang T, Craig EA. Binding of yeast frataxin to the scaffold for Fe-S cluster biogenesis, Isu. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12674–12679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800399200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai C-L, Barondeau DP. Human frataxin is an allosteric switch that activates the Fe-S cluster biosynthetic complex. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9132–9139. doi: 10.1021/bi1013062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmucker S, Martelli A, Colin F, Page A, Wattenhofer-Donzé M, Reutenauer L, Puccio H. Mammalian Frataxin: An Essential Function for Cellular Viability through an Interaction with a Preformed ISCU/NFS1/ISD11 Iron-Sulfur Assembly Complex. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marelja Z, Stöcklein W, Nimtz M, Leimkühler S. A novel role for human Nfs1 in the cytoplasm: Nfs1 acts as a sulfur donor for MOCS3, a protein involved in molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25178–25185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804064200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegel LM. A direct microdetermination for sulfide. Anal Biochem. 1965;11:126–132. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(65)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang J, Cowan JA. Iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis: role of a semi-conserved histidine. Chem Commun (Camb) 2009;21:3071–3073. doi: 10.1039/b902676b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Cera E. Kinetics of Allosteric Activation. Methods in Enzymology, Vol 466: Biothermodynamics, Pt B. 2009;466:259–271. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)66011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leslie AGW. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Joint CCP4 + ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 42.The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dhe-Paganon S, Shigeta R, Chi YI, Ristow M, Shoelson SE. Crystal structure of human frataxin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30753–30756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McRee DE. XtalView/Xfit A Versatile Program for Manipulating Atomic Coordinates and Electron Density. Journal of Structural Biology. 1999;125:156–165. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winn MD, Murshudov GN, Papiz MZ. Macromolecular TLS refinement in REFMAC at moderate resolutions. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:300–321. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brunger AT. The Free R value: a Novel Statistical Quantity for Assessing the Accuracy of Crystal Structures. Nature. 1992;355:472–474. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Furne J, Saeed A, Levitt MD. Whole tissue hydrogen sulfide concentrations are orders of magnitude lower than presently accepted values. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1479–R1485. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90566.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agar J, Krebs C, Frazzon J, Huynh BH, Dean DR, Johnson M. IscU as a scaffold for iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis: sequential assembly of [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] clusters in IscU. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7856–7862. doi: 10.1021/bi000931n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prischi F, Konarev PV, Iannuzzi C, Pastore C, Adinolfi S, Martin SR, Svergun DI, Pastore A. Structural bases for the interaction of frataxin with the central components of iron-sulphur cluster assembly. Nat Commun. 2010;1:95. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Musco G, Stier G, Kolmerer B, Adinolfi S, Martin SR, Frenkiel TA, Gibson TJ, Pastore A. Towards a structural understanding of Friedreich's ataxia: the solution structure of frataxin. Structure. 2000;8:695–707. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pavone V, Gaeta G, Lombardi A, Nastri F, Maglio O, Isernia C, Saviano M. Discovering protein secondary structures: classification and description of isolated alpha-turns. Biopolymers. 1996;38:705–721. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199606)38:6%3C705::AID-BIP3%3E3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poirier J, Pandolfo M. A missense mutation (W155R) in an American patient with Friedreich Ataxia. Hum Mutat. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saccà F, Puorro G, Antenora A, Marsili A, Denaro A, Piro R, Sorrentino P, Pane C, Tessa A, Brescia Morra V, Cocozza S, De Michele G, Santorelli FM, Filla A. A combined nucleic Acid and protein analysis in friedreich ataxia: implications for diagnosis, pathogenesis and clinical trial design. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17627. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Correia AR, Adinolfi S, Pastore A, Gomes CM. Conformational stability of human frataxin and effect of Friedreich's ataxia-related mutations on protein folding. Biochem J. 2006;398:605–611. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Correia A, Pastore C, Adinolfi S, Pastore A, Gomes C. Dynamics, stability and iron-binding activity of frataxin clinical mutants. FEBS J. 2008;275:3680–3690. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gordon DM, Shi Q, Dancis A, Pain D. Maturation of frataxin within mammalian and yeast mitochondria: one-step processing by matrix processing peptidase. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2255–2262. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.12.2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rufini A, Fortuni S, Arcuri G, Condo' I, Serio D, Incani O, Malisan F, Ventura N, Testi R. Preventing the ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent degradation of frataxin, the protein defective in Friedreich's Ataxia. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calmels N, Schmucker S, Wattenhofer-Donzé M, Martelli A, Vaucamps N, Reutenauer L, Messaddeq N, Bouton C, Koenig M, Puccio H. The first cellular models based on frataxin missense mutations that reproduce spontaneously the defects associated with Friedreich ataxia. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leidgens S, De Smet S, Foury F. Frataxin interacts with Isu1 through a conserved tryptophan in its beta-sheet. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:276–286. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boehm T, Scheiber-Mojdehkar B, Kluge B, Goldenberg H, Laccone F, Sturm B. Variations of frataxin protein levels in normal individuals. Neurol Sci. 2011;32:327–330. doi: 10.1007/s10072-010-0326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steinkellner H, Scheiber-Mojdehkar B, Goldenberg H, Sturm B. A high throughput electrochemiluminescence assay for the quantification of frataxin protein levels. Anal Chim Acta. 2010;659:129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hudder B, Morales J, Stubna A, Münck E, Hendrich M, Lindahl P. Electron paramagnetic resonance and Mössbauer spectroscopy of intact mitochondria from respiring Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2007;12:1029–1053. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ghaemmaghami S, Huh W-K, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O'Shea EK, Weissman JS. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Campuzano V, Montermini L, Lutz Y, Cova L, Hindelang C, Jiralerspong S, Trottier Y, Kish SJ, Faucheux B, Trouillas P, Authier Fo, Dürr A, Mandel JL, Vescovi A, Pandolfo M, Koenig M. Frataxin is reduced in Friedreich ataxia patients and is associated with mitochondrial membranes. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1771–1780. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.11.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Willis J, Isaya G, Gakh O, Capaldi R, Marusich M. Lateral-flow immunoassay for the frataxin protein in Friedreich's ataxia patients and carriers. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ma B, Elkayam T, Wolfson H, Nussinov R. Protein-protein interactions: structurally conserved residues distinguish between binding sites and exposed protein surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5772–5777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1030237100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gallivan JP, Dougherty DA. Cation-pi interactions in structural biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9459–9464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cook JD, Kondapalli KC, Rawat S, Childs WC, Murugesan Y, Dancis A, Stemmler TL. Molecular details of the yeast frataxin-Isu1 interaction during mitochondrial Fe-S cluster assembly. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8756–8765. doi: 10.1021/bi1008613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adinolfi S, Iannuzzi C, Prischi F, Pastore C, Iametti S, Martin S, Bonomi F, Pastore A. Bacterial frataxin CyaY is the gatekeeper of iron-sulfur cluster formation catalyzed by IscS. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:390–396. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]