Abstract

Combinations of medications that control HIV viral replication are called antiretroviral therapy (ART). Regimens can be complex, so medication adherence is often suboptimal, although high rates of adherence are necessary for ART to be effective. Social support, which has been directly and indirectly associated with better treatment adherence in HIV-infected individuals, influences negative affect, including depression and anxiety. Our study assessed whether current anxious and depressive symptoms mediated the relationship between general social support and recent self-reported medication adherence in HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM; N = 136; 65% White, 15% Black/African American). Results revealed no direct effect, but an indirect effect of depressive (95% CI [−.011, −.0011]) and anxious symptoms (95% CI [−.0097, −.0009]), between social support and medication adherence. Greater levels of social support were associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety, which in turn were associated with lower ART adherence.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, HIV, medication adherence, men who have sex with men, MSM, social support

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens—combinations of medications that inhibit viral replication of HIV through a variety of biological mechanisms—revolutionized HIV care in 1996 and have been associated with significant reductions in HIV-related deaths (Chesney, Morin, & Sherr, 2000). ART regimens control but do not cure HIV; in order to receive the full benefits of ART and avoid developing resistance to the medication, research suggests that patients may have to engage in levels of adherence at 90% or greater (Chesney et al., 2000). This can be challenging for patients who must take these medications every day for an indefinite length of time. These circumstances, along with the negative side effects of ART regimens, contribute to the difficulty faced by patients trying to maintain optimal levels of adherence. Much research has focused on identifying methods to increase adherence (Simoni, Pearson, Pantalone, Crepaz, & Marks, 2006), although more research is needed to develop and test effective interventions.

Social support has been associated with greater treatment adherence in individuals infected with HIV and may be a key component of adherence interventions (Catz, Kelly, Bogart, Benotsch, & McAuliffe, 2000; DiIorio et al., 2009; Simoni, Frick, & Huang, 2006). Research has also indicated that greater social support is associated with increased medication adherence through several mediators (e.g., Cha, Erlen, Kim, Sereika, & Caruthers, 2008). That is, social support appears to be related to adherence through one or more indirect paths.

Simoni, Frick, and Huang (2006) provided empirical support for a cognitive-affective model identifying specific constructs that mediated the effects of social support on ART adherence. Using structural equation modeling, these authors created a latent variable (negative affect) comprising depression, anxiety, and life stress. In their study (Project HAART), they found that social support was associated with less negative affect, which, in turn, was associated with greater self-efficacy to adhere, and greater self-efficacy to adhere was associated with higher rates of medication adherence. Simoni, Frick, and Huang (2006) tested this model in a sample of men and women (N = 136, 45% women) infected with HIV in the Bronx, New York. Most (83%) identified as being exclusively heterosexual, and most (85%) identified their race/ethnicity as either African American or Puerto Rican. The study used the UCLA Social Support Inventory (Schwarzer, Dunkel-Schetter, & Kemeny, 1994) to assess social support. This inventory had not been normed on chronically ill populations and may not have effectively tapped into aspects of social support that were more relevant to individuals infected with HIV (i.e., support for HIV disclosure or medication-taking).

DiIorio and colleagues (2009) found similar results in a sample of mostly Black/African American men and women (67% men; sexual orientation not reported) infected with HIV in a large southeastern U.S. city. In their study, depression, which had a significant association with self-efficacy, mediated the relationship between social support and ART adherence. Their measure included only four social support items, with each question appearing to assess a different dimension of social support. One consequence may have been that the measure did not accurately capture the full range of social support received by the participants. Using a measure with so few items would be limited by its ability to inquire about a full range of experiences and support behaviors. Further, DiIorio and colleagues’ (2009) measure of ART adherence assessed reasons for missing medications rather than directly assessing pill-taking behaviors.

The Simoni, Frick, and Huang (2006) and DiIorio and colleagues (2009) studies were both well conducted and added significantly to the growing literature on adherence. Each identified a similar mental health pathway by which social support increased adherence. Our aim was to replicate and extend these and similar studies by (a) employing social support measures more relevant to people infected with HIV, and (b) attempting to assess medication adherence by including a variety of aspects of pill-taking behavior. We also planned to extend the existing research by assessing the aforementioned relationships in a sample comprised exclusively of men who have sex with men (MSM) infected with HIV. Our project aimed to replicate previous findings that depression (Cha et al., 2008; DiIorio et al., 2009; Simoni, Frick et al., 2006) and anxiety (Simoni, Frick et al., 2006) mediated the relationship between social support and medication adherence. Much of the extant literature has assessed depression, rather than anxiety, as a mediator of this relationship. Our intent was thus to extend prior models by assessing anxiety in addition to depression in order to identify an alternative pathway by which social support could have affected ART adherence. Anxiety is important to assess in a sample of HIV-infected individuals as previous literature has suggested that high levels of anxiety in this population (e.g., Orlando et al., 2002) and anxious symptoms have been shown to play a role in self-care behaviors, including medication adherence, that are required of a person on ART (Beusterien, Davis, Flood, Howard, & Jordan, 2008). We chose to explore the ways in which the social support and negative affect constructs were associated with ART adherence among MSM infected with HIV because MSM have the highest incidence and prevalence of HIV in the United States, above and beyond any other group (bCenters for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010b). We used secondary data analysis from our existing dataset to evaluate whether previous models generalized to participants in a sexual minority sample.

According to Simoni, Frick, and Huang’s (2006) and DiIorio and colleagues’ (2009) frameworks, social support is mediated by cognitive and affective variables, rather than directly affecting medication adherence. Based on this, our primary research aims were:

Aim 1: To assess whether current depressive symptoms mediated the relationship between social support received and recent medication adherence.

Aim 2: To assess whether current anxious symptoms mediated the relationship between social support received and recent medication adherence.

Methods

Procedures

Data from HIV-infected MSM (N = 178) were collected from two outpatient HIV clinics within the University of Washington medical system in Seattle, Washington, in 2006–2007. Referrals came from a social worker at the Virology Clinic and a research nurse at the Madison Clinic who routinely met with each patient at medical visits. The study, known as Project LEAP (Life Experiences Affecting Prognosis), involved participation in a one-time, computer-based interview, and was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. Eligibility criteria required that participants (a) were active patients at one of the clinics, (b) were at least 18 years of age, (c) were biologically male at birth, (d) were English-speaking, (e) reported recent sex with a man, and (f) signed an informed consent form agreeing to participate in the computerized interview and to allow the researchers access to information contained in their electronic medical records. Participants were paid $20 and given a list of free or low-cost social service resources in the community geared toward people infected with HIV.

Measures

Well-validated measures with established psychometric properties were administered whenever possible through a computerized interview using ci3 software (Sawtooth Technologies, Skokie, IL). We used the following measures to asses our main variables.

Demographics

Basic demographic information about the sample was collected through a series of investigator-created questions about age, race, income, level of education, employment, disability status, gender identity, sexual orientation, and sexual behavior.

Social support

The 19-item Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support survey (MOS-SS; Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991) was used to assess the frequency by which respondents perceived the availability of various types of general support when they needed it. This measure was developed with a chronically ill sample, and has been used in many samples of people infected with HIV (e.g., Burgoyne & Renwick, 2004). Participants were asked, How often is each of the following types of support available to you if you need it?; response choices ranged from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time). Items included, for example, Someone to confide in or talk to about yourself or your problems, and Someone to do something enjoyable with. The total social support score (Cronbach’s α = .97) comprised the average of the responses. As recommended by the measure’s authors, total scores were transformed on a 0–100 scale (100 = the highest amount of perceived support possible). No published data have reported on a clinically significant cutoff for this measure of social support.

Depression

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Center for Epidemiological Study-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). This commonly used instrument asked respondents to rate the frequency with which they experienced any of 20 depressive symptoms during the previous week. Sample items included, I thought my life had been a failure and I had crying spells. Response choices ranged from one (rarely or none of the time; less than 1 day/week) to 4 (most or all of the time; 5–7 days/week). This measure was operationalized as the sum of the items endorsed. As recommended by the measure’s authors, a score of 16 or higher was the cutoff for likelihood of meeting criteria for clinical depression in the general population. However, Hedayati, Bosworth, Kuchibhatla, Kimmel, and Szczech (2006) found that a score of 18 or higher on the CES-D may have been a more valid measure of clinically significant depressive symptoms in patients with a chronic disease, as this group typically endorsed more symptoms on the somatic subscale, artificially elevating the total score. In our study, we retained all 20 items (α = .92).

Anxiety

Participants filled out the state anxiety subscale (10 items) of the State-Trait Personality Inventory (STPI; Spielberger, 1979). Respondents were asked to report to what extent they feel calm, for example, at the moment of the interview. We used state anxiety rather than trait anxiety in our analyses because our interest was on current symptoms (similar to the measure of current depressive symptoms). Response choices ranged from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much so). In the analyses, this measure was operationalized as the sum of the 10 items (α = .91). No published data report on a clinically significant cutoff for this measure of anxious symptoms.

HIV medication adherence/non-adherence

Because there were no standard measures of adherence in HIV research, adherence to HIV medications was assessed by six investigator-created questions based on recommendations by a systematic review of self-reported ART adherence measures (Simoni, Kurth et al., 2006). Of the six questions that measured adherence, one item assessed pill-taking behavior in the previous 7 days (number of missed doses), and the following five items assessed cognitive and affective constructs related to adherence (yes/no):

In general, sometimes if you feel worse, do you stop taking your HIV medicines?

In general, do you ever forget to take your HIV medicine?

In general, are you careless at times about taking your HIV medicine?

In general, if at times you feel psychologically or emotionally worse, do you stop taking your HIV medications?

In general, do you sometimes stop taking your HIV medications because you just do not want to take them?

In these analyses, we followed Simoni, Kurth, and colleagues’ (2006) recommendations to create a composite measure of adherence. For the item asking about the number of missed doses in the previous 7 days, we dichotomized this item to reflect either 100% adherence (no missed doses, coded as 0 in the composite measure), or less than 100% adherence (one or more missed doses, coded as 1 in the composite measure). We made this decision to increase validity of the measure, as recommended in the literature; continuous self-report adherence measures are highly skewed and non-normal (e.g., Simoni, Pearson et al., 2006). Our composite measure (α = .81) resulted in an ordinal rating of adherence, ranging from zero (more adherent; reflecting higher/better adherence) to six (less adherent; reflecting lower/worse adherence).

Analysis

Baron and Kenny’s (1986) statistical mediation model has been used frequently to identify mechanisms or indirect pathways (i.e., called either mediators or indirect effects) to explain the relationship between an independent and dependent variable. However, their model has also been critiqued as being too conservative with its necessary criterion (normal distribution, relationship between independent & dependent variables, etc.), having lower power, and exhibiting higher Type I error rates than other more contemporary statistical methods that test for indirect effects (e.g., Hayes, 2009). Therefore, we followed guidelines set forth by Fairchild and MacKinnon (2009) in their test of indirect effects, using PRODCLIN statistical software (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007). This procedure has been shown to have lower Type I error rates and higher statistical power than other tests of indirect effects, including Baron and Kenny’s (1986) method (e.g., MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007).

We measured and entered the unstandardized beta coefficients and standard errors for both paths A (social support predicts either depressive or anxious symptoms) and B (either depressive or anxious symptoms predict medication adherence) using multiple linear regressions. We then entered the correlation between the independent and dependent variables (r = −.154, p = .10) from Aims 1 and 2 and set the significance level at p < .05. The PRODCLIN software output included confidence intervals for each regression equation but no test statistic; the result was significant if the lower and upper confidence limits did not include zero.

Results

Participants

Participants enrolled in Project LEAP were 178 HIV-infected MSM, of whom 42 participants were excluded from this analysis. Reasons for exclusion included not being on an ART regimen (10), not completing the necessary questionnaires for analyses (24), having experienced technical difficulties (4), or answering with an improbable response pattern (1). We excluded an additional three male-to-female transgender participants to maintain a sample of individuals who all identified as men (see Table 1). These exclusions resulted in a final analytic sample of 136. Every participant indicated that one of his recent sex partners had been a man and most of the men in the sample either identified as being “only” or “mostly” gay (85%). The average depression score for this sample (M = 19.7, SD = 12.7) was above the threshold for clinically significant depressive symptoms for both the general population (cutoff score = 16; Radloff, 1977) and samples with chronic illness (cutoff score = 18; Hedayati et al., 2006; see Table 2). On a continuous scale of being 0–100% adherent to ART in the previous 30 days, men in this sample reported relatively high rates of medication adherence (M = 93%, SD = 13.2). The mode of the ordinal composite adherence measured was zero, indicating that most participants in this sample reported the highest adherence possible.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample of HIV-infected MSM (N =136)

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (years) | M = 44.4 | SD = 8.1 |

| Racial Background | ||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 9 | 6.6 |

| Black or African American | 20 | 14.7 |

| White | 89 | 65.4 |

| More than one race | 9 | 6.6 |

|

| ||

| Currently Employed | ||

| Yes | 24 | 17.6 |

| No | 111 | 81.6 |

|

| ||

| Personal Monthly Income | ||

| $0–552 | 39 | 28.7 |

| $553–738 | 24 | 17.6 |

| $739–1477 | 50 | 36.8 |

| $1478–2214 | 12 | 8.8 |

| $2215–2731 | 1 | 0.7 |

| $2732–3500 | 4 | 2.9 |

|

| ||

| Current steady sexual or romantic partner | ||

| Yes | 51 | 37.5 |

| No | 83 | 61.0 |

Note. Percentages do not equal 100 because of missing responses.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among the Variables

| Variable | Social Support | Depressive Symptoms | State Anxiety | HIV Medication Adherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Support | -- | −.219a | −.219a | −.154 |

| Depressive Symptoms | -- | .706b | .352b | |

| State Anxiety | -- | .304b | ||

| HIV Medication Adherence | -- | |||

| Mean | 61.3 | 19.7 | 18.9 | Mode = 0 |

| Standard Deviation | 27.1 | 12.7 | 7.0 | -- |

| Observed Range | 0–100 | 0–52 | 10–38 | 0–6 c |

| Possible Range | 0–100 | 0–60 | 10–40 | 0–6c |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .001.

0 (more adherent—higher/better adherence) to 6 (less adherent—lower/worse adherence).

Analyses

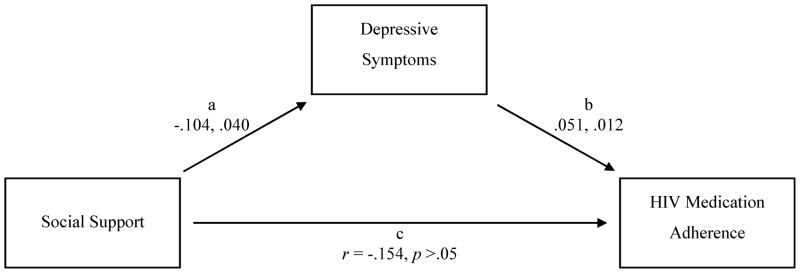

Aim 1 was to assess whether depression explained an indirect effect between social support and medication adherence. Our results indicated a significant indirect effect for depression in the hypothesized model, 95% CI [−.011, −.0011], such that current depressive symptoms mediated the relationship between social support and recent medication adherence (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Path model of depressive symptoms as an indirect effect between social support and medication adherence for Aim 1, 95% CI [−.011, −.0011]. Unstandardized coefficients and standard errors are listed, respectively, for paths a and b. Both paths were significant at p < .05.

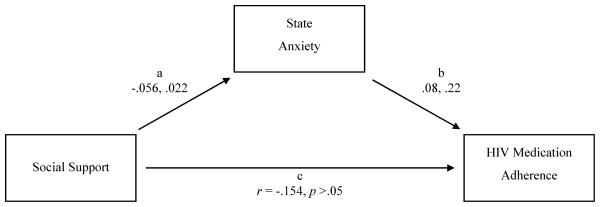

Aim 2 was to assess whether anxiety explained an indirect effect between social support and medication adherence. Our results showed a significant indirect effect for anxiety in the hypothesized model, 95% CI [−.0097, −.0009], such that the relationship between social support and recent medication adherence appeared to be mediated by current anxious symptoms (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Path model of anxious symptoms as an indirect effect between social support and medication adherence for Aim 2, 95% CI [−.0097, −.0009]. Unstandardized coefficients and standard errors are listed, respectively, for paths a and b. Both paths were significant at p < .05.

Discussion

To evaluate the role that social support plays in helping individuals infected with HIV to adhere to their ART regimens, we assessed for two intervening variables, current depressive and anxious symptoms, that could have facilitated an indirect relationship between general social support received and HIV medication adherence, a pathway previously supported by both Simoni Frick, and Huang (2006) and DiIorio and colleagues (2009). In our sample, composed of HIV-infected MSM engaged in comprehensive HIV care in Seattle, our results suggested that both depressive symptoms and anxious symptoms did, indeed, contribute to the indirect path between social support and medication adherence.

Aim 1

There was no statistically significant relationship between social support and medication adherence, which would have indicated a direct effect for these variables. However, as we predicted, these factors appeared to be related through negative affect, namely, depressive symptoms (Aim 1). This finding replicated other published research in this area (Cha et al., 2008; DiIorio et al., 2009; Simoni, Frick et al., 2006). Greater levels of social support were associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms (path A). This finding seemed plausible, considering that social support was a construct that affected, and was affected by, depressive symptoms, such that at least one evidence-based treatment for depression aims to increase social support or interpersonal skills as a primary therapeutic objective (e.g., interpersonal therapy; Lett, Davidson, & Blumenthal, 2005).

Further, lower levels of depressive symptoms were associated with better adherence (path B). Given that the presence of significant depressive symptoms could make it difficult for an individual to adhere to ART (i.e., low energy, impaired memory, and pessimistic thoughts about the future may make it difficult to take medications in the present), having fewer depressive symptoms was associated with better adherence in this and previous samples (Cha et al., 2008; DiIorio et al., 2009; Simoni, Frick et al., 2006). Thus, we found that greater levels of social support were associated with greater levels of medication adherence through an indirect path of fewer depressive symptoms in this sample of HIV-infected MSM, a group not captured by previous work in this area. Our results lend preliminary support to the notion that ART adherence interventions should aim to increase and maintain high levels of social support in this population.

Aim 2

Our second aim was also supported by these data. Much research has focused on depression, and not anxiety, as a mediator between social support and adherence (e.g., Cha et al., 2008; DiIorio et al., 2009). Our anxiety findings were consistent with the model by Simoni, Frick, and Huang (2006), such that anxiety significantly explained part of this relationship. Greater social support was associated with less state anxiety (path A).

Given that epidemiologic data have shown a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders in HIV-infected individuals (Orlando et al., 2002) compared to HIV-uninfected peers, we can hypothesize that some reports of anxiety in our sample may have been related to the present situation of living with HIV. Individuals infected with HIV may experience anxiety about decreased life expectancy, medical problems associated with HIV disease, side effects of ART or other co-morbid conditions, disclosure of HIV status to others including romantic/dating partners or family members, or social stigma associated with HIV (e.g., Beusterien et al., 2008). It seems plausible that having more social support would result in less anxious symptoms, especially those related to interpersonal relationships (i.e., less fear of HIV status disclosure in the context of a generally supportive social network). We can expect that receiving more emotional support, such as encouragement or validation, and more tangible support, such as a ride to the doctor or child care, would decrease anxiety about living with and managing this chronic illness.

In our study, lower levels of anxiety were associated with better adherence (path B). Anxious symptoms may manifest cognitively with excessive worrying and preoccupation. Regardless of the content of such worries, these anxious symptoms may increase the possibility that an individual would forget to take medications. Other anxious symptoms are somatic or physiologic, such as having stomach aches or physical feelings of tension, and these symptoms might make a patient less likely to adhere for fear that the medicine would exacerbate existing physical complaints (e.g., erroneously thinking that somatic complains were a side effect of the medicine when, in fact, they were related to the patient’s anxiety). With less social support, coping with these and other difficulties associated with HIV may be more challenging and could result in more anxious symptoms, potentially interfering with ART adherence. Therefore, it makes sense that we found that individuals who reported higher levels of social support also reported experiencing less anxiety and better ART adherence. Our study provided additional support for previously published findings that higher levels of social support were associated with more reports of medication adherence through negative affect and preliminary support for this relationship in a sample of sexual minority men.

Conclusions

Our results, paired with those of published research, have implications for future HIV medication adherence interventions. While HIV incidence in the United States is highest for Black and African American individuals of any sexual orientation compared to White and Hispanic/Latino individuals of any sexual orientation, (CDC, 2010a), MSM currently have the highest prevalence and incidence of HIV across sexual orientation groups (CDC, 2010b). As HIV is more common among MSM than other demographic and sociocultural groups—and since this has been true since the early days of the epidemic (Gottlieb et al., 1981)—it may be that it is better accepted and less stigmatized and, thus, more social support is available for HIV-infected MSM compared to other individuals living with the virus. HIV-infected MSM may be more likely to disclose their HIV status to their peers and, therefore, may be in a better position to access various types of social support from their networks. Greater community support and, consequently, less negative affect about these issues may be one key pathway to greater medication adherence.

Based on our findings and those of other researchers (Cha et al., 2008; DiIorio et al., 2009; Simoni, Frick et al., 2006), medication adherence interventions could utilize the normalization of HIV and strength of social support networks in MSM communities to enhance social support networks for HIV-infected individuals. Some studies have shown promising findings (e.g., Simoni, Pantalone, Plummer, & Huang, 2007) but more work is needed to improve the effectiveness of social support-enhancing interventions.

Limitations

In our study, a significant limitation was that our data were collected cross-sectionally, so the pathways we identified may not hold up over time or may occur in a different order. While a rigorous systematic review of adherence measures indicated that self-report items similar to ours were valid measurements of medication adherence (Simoni, Kurth et al., 2006), a more objective measure of pill-taking medication adherence behavior would be an unannounced pill count or an electronic data monitoring system that compiles an electronic record when a pill bottle is opened between assessment points. In addition, several variables as measured in our sample were skewed. For example, it is likely that, since our sample was engaged in routine comprehensive HIV care, they may have reported higher rates of medication adherence due to the effect of a social desirability bias.

Research Implications

Future studies should replicate assessing for anxiety, in addition to depression, to comprehensively evaluate the indirect relationships between social support and medication adherence. Future work might improve upon our work by using electronic data monitoring systems to measure adherence, and also by assessing negative affect variables and medication adherence within the same timeframe (i.e., past 30 days). While our study replicated past findings in a demographically different sample, more research is necessary to determine if these findings are maintained across different HIV-infected samples (i.e., different racial groups or sexual orientation groups). Researchers studying these pathways should explore these concepts in a variety of people with HIV infection who are less consistently adherent to ART or less engaged with HIV care, as those individuals may benefit from adherence interventions based on social support. More medication adherence intervention research should aim to increase social support, decrease negative affect, and target HIV-infected individuals not engaged in care.

Clinical Considerations.

Patients engaged in comprehensive HIV care (including a primary care provider, social worker, pharmacist, etc.) self-report high levels of ART medication adherence.

HIV-infected patients who report more negative affect may also be less adherent, so it is important for providers to screen for and address related anxiety and depression.

It may help to encourage patients who report less social support or suboptimal medication adherence to (a) join support groups, (b) expand their social networks, (c) focus on increasing social skills to improve social support networks, and (d) address negative affect symptoms by engaging in mental health treatment to improve ART adherence.

-

Clinicians may wish to screen for symptoms of anxiety and depression using the measures employed in this study.

At least one study has suggested that the CES-D is an adequate screener for depression for patients in primary care (Zich, Attkisson, & Greenfield, 1990) and, therefore, would likely be a good, brief depression screener for HIV-infected patients, although the scores may be elevated because of the somatic subscale.

We are not aware of any published literature that indicates that the State Anxiety Subscale of the STPI is an adequate anxiety screener for HIV-infected patients. However, the measure is commonly used in research, is brief, and is easy for patients to fill out. Thus, it could serve as a brief screener for anxiety in HIV-infected patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by National Institute of Mental Health grant #F31-MH71179.

Footnotes

Disclosures. The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article (including relationships with pharmaceutical companies, biomedical device manufacturers, grantors, or other entities whose products or services are related to topics covered in this manuscript) that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Eva N. Woodward, Doctoral Student in Clinical Psychology, Suffolk University, Boston, MA, USA.

David W. Pantalone, Assistant Professor of Psychology, Suffolk University, Boston, MA, USA.

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beusterien KM, Davis EA, Flood RR, Howard KK, Jordan JJ. HIV patient insight on adhering to medication: A qualitative analysis. AIDS Care. 2008;20(2):251–259. doi: 10.1080/09540120701487666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne R, Renwick R. Social support and quality of life over time among adults living with HIV in the HAART era. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:1353–1366. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00314-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catz SL, Kelly JA, Bogart LM, Benotsch EG, McAuliffe TL. Patterns, correlates, and barriers to medication adherence among persons prescribed new treatments for HIV disease. Health Psychology. 2000;19(2):124–133. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among African Americans. 2010a Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/aa/index.htm#ref1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM) 2010b Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/msm/index.htm#ref2.

- Cha E, Erlen J, Kim K, Sereika S, Caruthers D. Mediating roles of medication-taking self-efficacy and depressive symptoms on self-reported medication adherence in persons with HIV: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008;45(8):1175–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Morin M, Sherr L. Adherence to HIV combination therapy. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50(11):1599–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, McCarty F, DePadilla L, Resnicow K, Holstad M, Yeager K, Lundberg B. Adherence to antiretroviral medication regimens: A test of a psychosocial model. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(1):10–22. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AJ, MacKinnon DP. A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prevention Science. 2009;10(2):87–99. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0109-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb MS, Schroff R, Schanker HM, Weisman JD, Fan PT, Wolf RA, Saxon A. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and mucosal candidiasis in previously healthy homosexual men: Evidence of a new acquired cellular immunodeficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 1981;305:1425–1431. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198112103052401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76(4):408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Kuchibhatla M, Kimmel PL, Szczech LA. The predictive value of self-report scales compared with physician diagnosis of depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney International. 2006;69:1662–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lett HS, Davidson J, Blumenthal JA. Nonpharmacologic treatments for depression in patients with coronary heart disease. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S58–S62. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000163453.24417.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39(3):384–389. doi: 10.3758/BF03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Burnam A, Beckman R, Morton SC, London AS, Bing EG, Fleishman JA. Re-estimating the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a nationally representative sample of persons receiving care for HIV: Results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2002;11(2):75–82. doi: 10.1002/mpr.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Dunkel-Schetter C, Kemeny M. The multidimensional nature of received social support in gay men at risk of HIV infection and AIDS. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1994;22(3):319–339. doi: 10.1007/BF02506869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne C, Stewart A. The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Frick P, Huang B. A longitudinal evaluation of a social support model of medication adherence among HIV-positive men and women on antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychology. 2006;25(1):74–81. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(3):227–245. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Pantalone DW, Plummer MD, Huang B. A randomized controlled trial of a peer support intervention targeting antiretroviral medication adherence and depressive symptomatology in HIV-positive men and women. Health Psychology. 2007;26(4):488–495. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Crepaz N, Marks G. Efficacy of highly active antiretroviral therapy interventions in improving adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load: A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;43:S23–S35. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248342.05438.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Unpublished manuscript. University of South Florida; 1979. State-Trait Personality Inventory (STPI), preliminary manual. [Google Scholar]

- Zich JM, Attkisson C, Greenfield TK. Screening for depression in primary care clinics: The CES-D and the BDI. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1990;20(3):259–277. doi: 10.2190/LYKR-7VHP-YJEM-MKM2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]