Abstract

With the continued failures of both early diagnosis and treatment options for pancreatic cancer, it is now time to comprehensively evaluate the role of the immune system on the development and progression of pancreatic cancer. It is important to develop strategies that harness the molecules and cells of the immune system to treat pancreatic cancer. This review will focus primarily on the role of immune cells in the development and progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). We will evaluate what is known about the interaction of immune cells with the tumor microenvironment and their role in tumor growth and metastasis. We will conclude with a brief discussion of therapy for pancreatic cancer and the potential role for immunotherapy. We hypothesize that the role of the immune system in tumor development and progression is tissue specific. Our hope is that better understanding of this process will lead to better treatments for this devastating disease.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, immune response, immunotherapy, immune

Section I: Introduction

Pancreatic cancer has a fatality rate of 95%. Early detection is rare and the majority of patients present with locally advanced or metastatic disease with no real hope of an effective treatment. With the current treatment strategies, the median life expectancy is 6–10 and 3–6 months for patients presenting with locally advanced disease or metastatic disease, respectively.

For the purposes of this review we will be discussing the Immunology of PDAC, the major type of pancreatic cancer. We hypothesize that the role of the immune system in tumor development and progression is tissue specific. Our hope is that better understanding of the immunological aspects of PDAC will lead to better treatments for this devastating disease.

Basic Immunology Review

1. THE INNATE IMMUNE RESPONSE

Several cell types of the innate immune system can recognize “danger”, i.e., pathogens, tumors and damaged tissues. These include neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cell (DCs), mast cells and natural killer (NK) cells. NK cells can also be involved in recognizing cells infected with intracellular pathogens that down-regulate major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens and express viral antigens or altered self-antigens. Activated cells of the innate immune system can release molecules such as cytokines [interferons (IFNs), interleukins (ILs), colony stimulating factors (CSF)] and chemokines (CC). These molecules can lead to cell migration, local and systemic inflammation, and ultimately alert the adaptive immune system.

2. THE ADAPTIVE IMMUNE RESPONSE

While the specificity of the innate immune response is limited to toll-like receptors (TLRs) and several other conserved molecules that NK cells recognize, the cells of the adaptive immune response have enormous diversity and can recognize tens of millions of antigenic determinants or epitopes. A DC that has taken up an antigen matures as it leaves the site of a wound or infection, and completes its journey to the regional lymph node. DCs can degrade large antigens and present peptides or lipids in human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules of either the Class I or Class II types or in CD1 molecules. In the first instance, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTL or Tc) are activated and in the second, CD4+ T helper (Th) cells are activated. Mature Tc cells can kill infected cells directly. The activated Th cells can interact with naive B cells that also recognize the corresponding specific epitope(s) on the native molecule and provide co-stimulation for further differentiation. Both Tc and Th cells make cytokines that interact with B cells so that they eventually produce antibodies that are specific for epitopes on that antigen. Th cells are also responsible for controlling affinity maturation and isotype switching so that the antibodies produced are highly effective at eliminating a pathogen. This antibody can neutralize, opsonize and/or kill infected cells and pathogens.

3. TUMOR IMMUNOLOGY

Immune response against tumor cells can involve both innate and adaptive immune responses. An effective anti-tumor immune response involves recognition of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) by the immune system and the generation of T or B cell responses that will kill the tumor cells but not damage life-sustaining normal tissue. Tc cells can kill the tumor cells directly. Paradoxically, both Tc and Th cells produce cytokines that can inhibit or enhance the growth of the tumor. They also help B cells differentiate into memory cells as well as plasma cells that make antibodies against the tumor. These antibodies can kill or opsonize the tumor cells, stimulate or inhibit their growth or actually block Tc cells from killing the tumor cells. As in other tumor models, the immune system in patients with PDAC appears to have several roles. One role is to prevent tumor development by recognizing and removing abnormal cells arising from normal pancreatic cells. In this situation the immune system exerts an “anti-tumor response”. But, the immune system can also provide a “pro-tumor response”, whereby components of the immune response can stimulate the growth of tumor cells directly or indirectly by dampening the anti-tumor immune response.

Section II: The Role of Immune System - “Anti versus Pro-Tumor Response”

PDAC is an exocrine tumor that develops from the epithelial cells that line pancreatic ducts. However, it is a complex environment composed of many cell types including immune cells, pancreatic stellate cells (fibroblasts), vascular endothelial cells, endocrine cells and nerve cells. These cells can interact with tumor cells to disrupt the normal tissue architecture to form the dense stroma and the dynamic environment found in PDAC. Although it is currently well accepted that the immune response is determined by an invading pathogen or “danger” signal, Matzinger et al. (2011) have recently provided a new perspective on how immune responses are determined. The authors suggest that the tissue rather than the pathogen itself determines the type of immune response. The idea that the tissues control the effector phase of the immune response has arisen from a better understanding of immunologic phenomena of immune-privilege sites, oral tolerance and oral vaccination1. This concept is slowly gaining support. The basic understanding of tissue-specific factors that control immune function may be critical in fully understanding the immune response not only for invading pathogens, but also for tumor development and progression. Exploration of this new hypothesis may shed light on the highly variable immune responses observed when tumors arise from different organs. However, unless we truly understand the epidemiology (i.e., genetic pre-disposition, chronic inflammation, viral infection) of a cancer we will never fully understand the role and complexity of the immune response to that tumor. Nevertheless we are making progress towards defining the role of the immune system in regulating the growth of malignant cells as recently reviewed by Schreiber et al. (2011)2.

Lymphocytes are considered the main effector cells for the anti-tumor immune response. The lymphocytic cell populations are predominantly found in the stroma surrounding the tumor mass with few or no lymphocytes in the actual tumor mass3,4. This surrounding stroma has a large population of CD4+ T lymphocytes and macrophages with a small population of B lymphocytes and plasma cells3. In patients with PDAC, no correlation was found between the numbers of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and the number of circulating lymphocytes. However, PDAC patients tend to have decreased numbers of circulating lymphocytes as compared to healthy individuals and individuals with chronic pancreatitis4.

The role of CD4+ T cells in PDAC immunity is poorly understood but depending upon the cytokine environment, CD4+ T cells can differentiate into Th1, Th2, Th17 or Treg cells. Th1 cells produce IL-2 and IFN-γ and induce B cells to make opsonizing antibodies. Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5 and IL-6 and induce B cells to make neutralizing antibodies. In cancer, as a general trend, the main immune response is mediated through Th2 cells. Currently, therapy for PDAC focuses on cellular immunity and “direct tumor cell killing” but humoral immunity could be just as important. Hence, understanding this complex balance between Th1 and Th2 responses in PDAC is crucial in developing better therapies for this disease. There are a few reports of the CD4+ T cell responses in PDAC. Tassi et al. (2008) compared CD4+ T cell responses in patients with PDAC to those of healthy donors and found that the former had impaired anti-carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)-specific but not anti-viral specific CD4+ T cell immunity5. Interestingly, in healthy donors CEA -specific CD4+ T cell immunity was significantly higher and produced mainly granulocyte-macrophage CSF (GM-CSF) and IFN-γ, whereas CD4+ T cells from patients with PDAC produced IL-5. However, there was no difference in the anti-viral CD4+ T cell response between the two. This study suggests that in PDAC CD4+ T cell immunity is skewed towards a Th2 type immune response and that this is locally mediated at the tumor site5. On the other hand, some studies support a more systemic Th2-like cytokine expression profile following CD4+ T cell activation6. A possible explanation for this discrepancy may be best explained by the stage of disease of the patients in the studies. In the former study, the patients were at an earlier stage of disease either stage 1 or 2 but in the later study, the majority of patients where at later stages of disease either stage 3 or 4. We assume that in tumor progression the immune response is initially capable of eliminating tumor cells and is therefore most likely a Th1-skewed response, because this response is activated by intracellular “danger” signals (altered self-proteins produced by tumor cells) and leads to cell mediated immunity (IFN-γ and activation of macrophages) to eliminate tumor cells. However, it is also possible that an early Th2 response occurs, an adaptive immune response more effective at removing extracellular “danger signals” that lead to IL-4 production and neutralizing antibodies. Hence, the two responses could be competing with or potentially enhancing each other, ultimately leading to the development of Treg cells which dampen the response as a protective measure to prevent autoimmunity. Therefore, understanding the type and function of immune cells in PDAC as well as the time line of the immune response, will facilitate the development of immunotherapeutic strategies to use at different stages of disease. For example, if at early stage of disease in PDAC, both Th1 and Th2 responses are active there might be a more effective anti- tumor response. However, at later stages of disease if Th2 responses are more beneficial the best strategy might be to shift the balance towards a Th2 response. The role of the immune system in the development and progression of pancreatic cancer is a powerful and dynamic tool that we must understand and apply strategically to promote anti-tumor responses at specific stages of disease.

In contrast to the direct anti/pro-tumor activity of Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cells, Th17 and Treg cells can regulate all T-cell responses. The differentiation of CD4+ T cells into either Th17 or Treg cells appears to involve a precarious balance between the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β)- driven expression of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) expression (which drives the development of Treg cells) and the production of TGF-β/IL-6 which favor the development of Th17 cells and inhibits the development of Treg cells. Th17 cells secrete IL17, a pro-inflammatory cytokine that mediates several effects on several different cell types7,8. In contrast, Treg cells inhibit the proliferation of T cells and dampen anti-tumor immunity.

Research on the Th17 CD4+ T cell lineage in PDAC is limited, but recent studies have shown that if the cytokine balance of the tumor environment is tipped in favor of the development of the Th17 cell lineage by inducing IL-6 or depleting the Treg cells an anti-tumor effect is achieved9,10. The role of Th17 cells in cancer is currently under investigation. There is no definitive answer as to whether Th17 cell enhance or inhibit tumor growth. However, it has been suggested that the role of Th17 cells may change depending on the cause, type, location and stage of the tumor11. If this were correct, it would further support the hypothesis that the role of the immune system in tumor development and progression is tissue specific and that an individual immune profile of each PDAC patient should guide therapy.

The role of Treg cells in PDAC is better understood. Both circulating Treg cellsand PDAC tissue-specific Treg cellsare significantly increased in patients with pancreatic cancer as compared to healthy controls. The presence of Treg cells in the tumor tissue correlates with the stage and progression of disease12,13. Treg cellsare known to induce tolerance against TAAs and suppress the anti-tumor activity of T cells14,15. In vivo studies suggest that a decrease or depletion of Treg cells in PDAC results in inhibited tumor growth and promotion of tumor-specific immune responses16,17 and that the increase in Treg cells in PDAC is dependent upon tumor derived TGF-β18,19.

PDAC has been characterized by the presence of few tumor-specific CD8+ T cells, B cells and tumor-reactive antibody producing plasma cells in the tumor mass. Antigens on PDAC cells can elicit either cellular or humoral immune responses, and in some instances, both. Tumor antigens that are recognized by the immune system and induce a response become tumor immunogens, and these are important for immune responses. However not all tumor antigens are immunogenic. A few of these PDAC cell antigens are being explored as targets in clinical trials. Immunogens in PDAC include α-enolase (ENOA)20, coactosin-like protein (CLP)21, mesothelin22, mucin 1 (MUC1)23–25, mutant kirsten rat sarcoma virus oncogene (KRAS)26–28, cadherin 3 (CDH3)/P-cadherin29, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)30, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/neu)31, prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA)32,33 and mutant p5334,35. The peripheral blood from PDAC patients contain a high frequency of functional tumor-reactive T cells that can ultimately lead to tumor antigen-specific T cell responses36. The bone marrow also contains tumor cell- reactive memory T cells36. Moreover, when evaluated together, the presence of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in malignant PDAC tissues correlates with a better prognosis than the presence of either alone37. Although this suggests that there is an anti-tumor response, unfortunately it is not enough. A possible explanation for the failure of the anti-tumor response may be provided by recent identification of the antibody independent functions of B cells. Thus, effector and regulatory B cells may regulate T cell immune responses by promoting the production of effector and memory CD4+ T cellsas well as the proliferation and survival of Treg cells38.

Natural killer (NK) cells are a subset of cytotoxic lymphocytes that only recently received attention for their role in tumor development. NK cells do not express unique antigen- specific receptors, but they play an important role in innate immunity and anti-tumor immunity39. They can induce target cell killing as a result of the complex integration of inhibitory and activating signals40. NK cells can produce IFN-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), GM-CSF and IL-341. Initially in PDAC research, subsets of NK cells were not distinguished, but now they are divided into two phenotypically and functionally distinct types of cells. The majority expresses low densities of CD56 (CD56lo), secrete low levels of cytokines and exert potent effector cell cytotoxicity. In contrast, the minority group expresses high levels of CD56 (CD56hi) and IL-2 receptor alpha chains (CD25), secrete high levels of cytokines and are poorly cytotoxic40. NK cells in PDAC have been reported to mediate tumor cell lysis42 and high levels of NK cells lead to a better prognosis43. However, even in early stage of disease, NK cell activity is impaired and worsens with advancing disease44,45. Interestingly, CD56hi NK cells exhibited potent reactivity on several pancreatic cancer cell lines in addition to autologous tumor cells46 that were identified from a pancreatic cancer patient undergoing immunotherapy with ipilimumab (a therapeutic antibody against CTLA-4, a T cell co-inhibitory molecule)46. Although anti-CTLA-4 antibodies block the activity of CTLA-4 and sustained immune responses in T cells, this patient had an anti-tumor response with potent NK cell activity. This supports the possibility that the activation of NK cells as well as CD4/CD8+ T cells can lead to the killing of tumor cells. Several groups have evaluated the effect of modulating NK cell activity as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activity by administering IL-2 to patients, to try and promote anti-tumor responses43,46–49.

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes or neutrophils are often a neglected cell type in the tumor microenvironment, but a better understanding of their impact in tumor development is beginning to emerge. Neutrophils are the most abundant type of leukocyte found in the blood and are not usually found in normal tissues. In response to the production of IL-8 and C5a during acute inflammation, neutrophils can produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), serine proteases, and metalloproteases to kill invading pathogens. The activity of neutrophils is thought to follow a linear progression and when recruited into the tumor microenvironment can induce both pro- and anti-tumor responses50. Although the active states of neutrophils are not clearly defined, it has been proposed that moderate neutrophil activity in the tumor microenvironment can promote tumor growth and invasion due to the production of ROS and proteases. In contrast, robust neutrophil activity can be toxic to tumor cells and promote an anti-tumor response50.

Only a few studies have evaluated the potential role of neutrophils in PDAC. In two separate studies, it was found that an elevated neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is a predictor of decreased patient survival51,52. In in vitro studies, it was found that activated neutrophils promote the adhesion of PDAC cells to microvascular endothelium53 possibly promoting tumor migration and extravasation. Furthermore, in vivo studies have found that tumor-infiltrating neutrophils produce matrix metalloprotease type 9 (MMP-9) a potent vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-independent angiogenic factor that mediates the initial angiogenic switch in PDAC54,55. Much more remains to be learned with regard to the role of neutrophils in PDAC. However, one might predict that by targeting tumor-associated neutrophils or their production of ROS and proteases, tumor invasion and growth might be inhibited.

Mast cells are typically studied in the context of type I hypersensitivity and autoimmunity. However, in a recent review by Khazaie et al. (2011) the role of mast cells as positive and negative regulators of the immune response in tumor development and progression is discussed56. Mast cells typically surround blood vessels and nerves and are activated by inflammation, cross-linking of IgE, or complement proteins. Following activation, mast cells can release several mediators including histamine, serine proteases, platelet activating factor and, importantly, VEGF57. In addition, mast cells can also produce cytokines typical of Th1 cells (GM-CSF, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) and Th2 cells (IL-4 and IL-13)56. Thus mast cells can play a pivotal role in both innate and adaptive immunity as well as modifying the tumor microenvironment by producing pro-inflammatory and angiogenic factors.

There are few studies involving the role of mast cells in PDAC. In one study by Esposito et al. (2004), mast cells were associated with lymph node metastasis as well as increased tumor microvessel density suggesting that their presence promotes an angiogenic phenotype58. However, this study did not find a correlation between mast cell number and patient survival58. In a subsequent study by Strouch et al. (2010) mast cell infiltration was significantly increased in pancreatic cancer as compared to normal controls and correlated with higher-grade tumors, as well as decreased recurrence-free and disease-specific survival59. In contrast to the previous study, Strouch et al. (2010) did not find a correlation between the number of mast cells and lymph node status. The discrepancies between these two studies may again be explained by the grade of tumor evaluated, or the heterogeneity between pancreatic tumors. Hence, in the former study, higher-grade metastatic tumors were studied, whereas in the later study all tumors were grade 3 or less. Strouch et al. (2010) also evaluated the in vitro mechanism by which mast cells can contribute to the poor prognosis in patients with PDAC. They found that in the absence of direct tumor cell contact, mast cells, mediated tumor cell migration, proliferation and invasion via MMPs59. These studies provide evidence that mast cells are emerging as promoters of angiogenesis and tumor progression in patients with PDAC.

Gabrilovich et al. (2009) have recently reviewed myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and their role as regulatory cells in the immune system60. MDSCs consist of myeloid progenitor cells and immature myeloid cells with immunosuppressive activity in cancer and other diseases60. In cancer, MDSCs are characterized by the expression of CD33 and the lack of expression of markers for mature myeloid or lymphoid cells61. Increased numbers of MDSCs have been associated with high levels of GM-CSF62 or VEGF63 in the circulation. However, these MDSCs do not differentiate in a normal way64. Once activated, MDSCs can serve as immunosuppressive cells by up-regulating arginase 1, nitric oxide synthase and increasing nitric oxide production from M-MDSCs and ROS production by G-MDSCs60,65–67. MDSCs can also inhibit the function of T cells in several ways that are not yet entirely clear. However, there are reports that they can down-regulate T cell mediated antigen-specific responses68, down-regulate TCRs/CD3-zeta chains69 and promote the development of Treg cells70,71. Other mechanisms of MDSCs immunosuppression include secretion of TGF-β72, up-regulation of cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX-2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)73 as well as negatively regulate NK cells by inhibiting effector functions72. These issues are discussed in recent reviews60,66,74.

Several in vivo studies of pancreatic cancer have shown increased numbers of MDSCs in the tumor microenvironment75–77. In one study of spontaneous pancreatic carcinoma, it was shown that not only are the MDSCs increased in frequency but they also have arginase activity and suppress T-cell responses76. Moreover, by evaluating the suppressive mechanisms from tumor inception throughout tumor development results suggests that the suppressive mechanism exists in early pre-malignant lesions and increase during tumor progression76. In another study, of mouse pancreatic cancer, the number of MDSCs inversely correlated with CD8+ T cells infiltrates and MDSCs were present in both the primary and metastatic lesions and not merely correlated with chronic inflammation77. It is easy to appreciate that therapeutic strategies designed to either inhibit MDSCs, their products or possibly promote their differentiation should be considered to treat tumor development and progression.

Most cells in the immune system have both pro-and anti-tumor activity. Macrophages can induce T cell recruitment and activation at the tumor site, as well as promote tumor cell growth, angiogenesis and immunosuppression. Tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) are derived from blood monocytes in response to tumor -derived signals such as macrophage-CSF (M-CSF), chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), VEGF and Angiopoietin-278–83. TAMs are functionally divided into two subtypes M1 and M2. TAMs M1 are activated in response to IFN-γ or microbial products and are characterized by production of high IL-12, IL-23, toxic intermediates and pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α. The M2 subset is induced by IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, glucocorticoids and immunoglobulin (Ig) complexes. They produce TGF-β and IL-10 and promote adaptive Th2 immunity, angiogenesis, tissue remodeling and repair83.

In PDAC, the role of macrophages is beginning to be explored. Macrophages are significantly more numerous in PDAC than in normal pancreatic tissue, and their accumulation does not correlate with chronic pancreatitis-like features in the surrounding tissue58. The TAM M2 subtype has been associated with a poor prognosis84. In an in vivo mouse model when large numbers of human monocytes were co-engrafted with human tumor cells, tumor growth was enhanced. However, when a low ratio of human monocytes were co-grafted with human tumor cells inhibition of tumor growth was observed85. This group has shown that repeated contact of monocytes with tumor cells leads to decreased production of cytotoxic molecules (TNF-α, reactive oxygen intermediates and IL-12) and increased production of immunosuppressive cytokine IL-1085,86. This suggests that there may be a maximum ratio of monocytes to tumor cells and a threshold of the molecules they produce that when exceeded no longer has anti-tumor effects. In an in vitro study by Baran et al. (2009), the production of TNF-α by TAMs lead to an increased number of pancreatic tumor cells as well as macrophage motility, ultimately inducing phenotypic tumor cell changes characteristic of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)87. These studies support the hypothesis that the increase in number of TAM and their products such as TNF-α in PDAC, may overcome a certain threshold and switch from an anti-tumor to a pro-tumor response, but further studies are needed to better understand the significance of the number and type of TAMs that play a role in PDAC.

The field of tumor immunology as applied to pancreatic cancer is in its infancy but several studies support the notion that immune cells are actively engaged in eliminating tumor cells and generating anti-tumor memory cells but that the response is either not robust enough to control tumor growth or potentially, too robust and causes damage that triggers immunosuppression and subsequent tumor growth. In a review by Sica et al. (2008) the role of M1/M2 macrophages in tumor development was hypothesized. The authors hypothesized that early in the course of tumor development, macrophages with an M1 phenotype (high IL-12, IL-23, toxic intermediates and TNF-α production) dominate and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and toxic intermediates support tumor formation. Once the tumor is established macrophages with the M2 phenotype (TGF-β, IL-10 production) dominate, thereby impairing the anti-tumor Th1 response and promoting tumor growth83. This supports the hypothesis of an early active Th1 response (production of anti-tumor T cells, NK cells, antibodies and cytokines) that becomes less effective as the disease progresses. This is accompanied by increased numbers of Treg cells and Th2 cytokine production. However, the time line of the immune response in PDAC is questionable. Clark et al. (2007) studied the immune response in pancreatic cancer from early disease to invasive cancer in a murine model of spontaneous PDAC. They found that early on there were few effector T cells and that the majority of infiltrating cells were macrophages, MDSCs and Treg cells77. Their findings suggest that from the inception of PDAC the immune system is suppressed and is never able to mount a robust anti-tumor response77,88. This might represent normal immune tolerance to self-tissue since most antigens on tumor cells are not recognized as foreign. Moreover, due to the vast heterogeneity seen in PDAC, both an early active Th1 response and suppression may occur. The balance between the two effects could be dependent upon the etiology of the disease as well as the immune system of the patient in question.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are responsible for the recognition of “danger”, i.e. pathogens as well as damaged tissue, activation of immunity and preservation of tolerance to self-antigens89. They constitute the critical link between the innate and adaptive immune systems since they can traffic from damaged/invaded tissue sites to regional lymph nodes and present antigen to T cells. Once this occurs the adaptive immune system is activated. DCs play a critical role in initiating the immune response against developing tumors. However, tumor progression and the influence of the tumor microenvironment can inhibit DC recruitment, differentiation, maturation and survival90. In a recent review by Ma et al. (2010) the mechanisms by which tumor cells regulate dendritic cells are thoroughly discussed. In brief, several factors are involved in the dendritic cell-tumor cell cross-talk including GM-CSF, VEGF, TGF-β, IL-10 and ROS90. Tumor cells can produce or express various metabolites or proteins that can prevent DCs from engulfing, recruiting, differentiating, migrating, activating, and cross-presenting antigens, thereby inhibiting a tumor-specific T cell response90. Furthermore, tumor cell death may either establish tumor-induced tolerance or enhance immune responses by exposing “cell death-associated patterns” that can ultimately induce a variety of innate immune responses90.

In PDAC, DCs are rare but when present, are located on the outside margin of the tumor91. A study evaluating the influence of circulating myeloid DCs (c-m-DCs), circulating lymphoid DCs (c-l-DCs) and DCs within the tumor on patient survival, it was found that a high percentage of c-m-DCs or high numbers of DCs in the tumor prolonged survival92. Other studies found that blood myeloid DCs in PDAC were only “partially mature” and the change in their expression of surface markers led to an impairment of their immunostimulatory function93. This change was also observed in patients with chronic pancreatitis suggesting that systemic inflammatory factors may play a role in this change93,94. In addition, it appears that preservation of mature blood DCs correlates with disease control and prolonged survival93,94. Several therapeutic strategies involve the vaccination of enhanced DC number and function in combination with other immune modulators and/or chemotherapy.

The future of immunotherapy will be dependent upon elucidating the roles of immune cell subtypes and their capacity to function or dysfunction at various stages during the development of pancreatic tumors.

Section III: Immune Interaction with Microenvironment

PDAC is a hypoxic environment with a dense stroma, which can comprise up to 90% of the tumor volume95–97. It is now understood that this dense stroma is derived from overgrowth of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and can “protect” and enhance tumor development by forming a barrier against both chemotherapeutic drugs as well as the immune system98. The production of fibroblast growth factor type 2 (FGF-2), epidermal growth factor (EGF) as well as the EGF receptor (EGFR)99, transforming growth factor alpha and beta type 1 (TGF-α100, TGF-β1), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) and VEGF by both tumor cells, immune cells and other stromal cells contribute to stromal production as well as tumor cell survival and growth99,101–105.

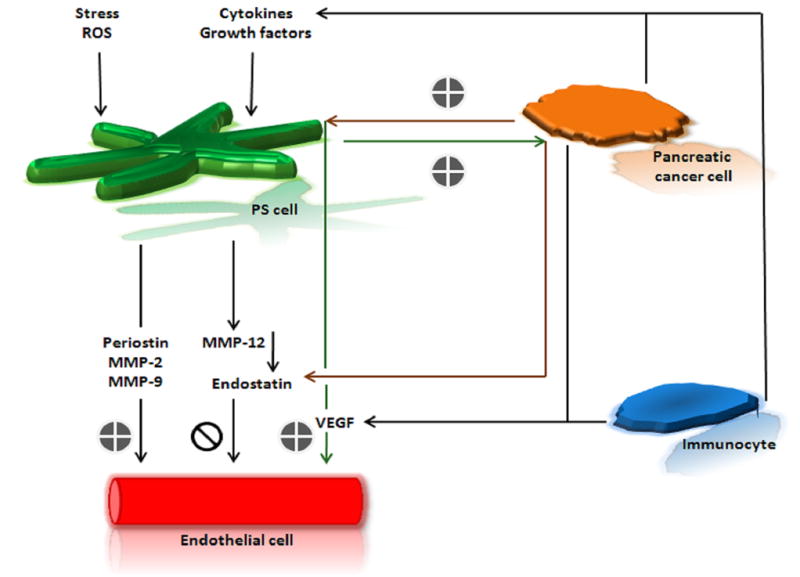

Pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) are myofibroblast-like cells and considered to be the main pancreatic cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts. These cells are recognized to be the key players in the development of desmoplasia as recently reviewed by Duner et al. (2011)106. When PSCs are activated by stress, cytokines or growth factors they become ECM protein-producing fibroblasts. In addition to producing ECM protein, stellate cells secrete periostin107, as well as produce MMP-2/gelatinase-A, MMP-9/gelatinase-B108 and MMP-12109. Periostin is a protein that enhances the fibrogenic activity of PSCs while promoting endothelial cell growth and motility107,109. MMP-2, MMP-9 can break down components of the basement membrane and help promote angiogenesis, ultimately leading to local invasion and disease progression108,110,111. On the other hand, MMP-12 can induce the production of an anti-angiogenic molecule, endostatin. Endostatin is a cleavage product of type XVIII collagen and can inhibit the proliferation of endothelial cells and ultimately, angiogenesis112. PSCs are the main producers of VEGF in the tumor microenvironment107. In a study of tumor cell-stellate cell interactions in PDAC by Erkan et al. (2009), it was found that while tumor cells induce secretion of VEGF by PSCs, PSCs increase endostatin production of tumor cells109. Although this balance between pro- and anti-angiogenic effects probably involves a variety of factors in addition to VEGF and endostatin, it is useful in understanding the stimulatory and inhibitory forces at play in the PDAC microenvironment (Figure 1A). Pancreatic stellate cells provide a promising target for pancreatic cancer therapy. A recent study has shown that the specific up-regulation of hedgehog receptor smoothened (SMO) gene expression activates the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts but not in normal pancreatic tissue113. This finding led to the development of SMO antagonists to target stromal fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. This is a challenging approach that relies heavily on interstitial fluid pressure for drug delivery. However, with the improved penetration of chemotherapeutic drugs into the tumor mass along with anti-angiogenic agents that help stabilize local vasculature SMO antagonists may find clinical utility for the treatment of PDAC.

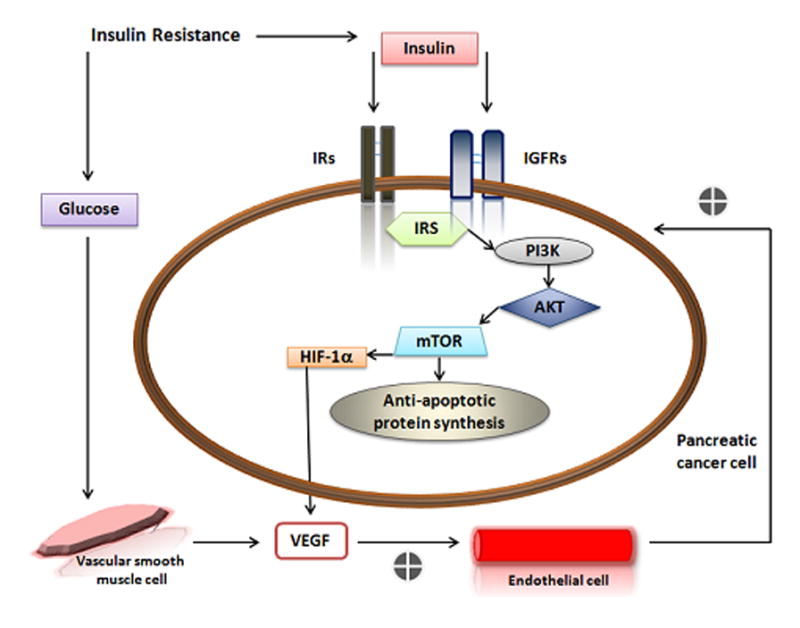

Figure 1. A–B Interaction between PDAC and the Microenvironment.

A. The pro- and anti-angiogenic function of Pancreatic Stelate (PS) cells. Immunocytes can release cytokines and growth factors that promote neo angiogenesis as well as activate PS cells. Upon activation by stress, ROS, cytokines and/or growth factors PS cells can secrete periostin to mediate endothelial cell adhesion and migration as well as secrete MMPs. MMPs can both promote neo angiogenesis through basal membrane destruction (MMP-2, MMP-9) or inhibit neo angiogenesis by triggering production of endostatin (MMP-12). Pancreatic cancer cells can also promote neo angiogenesis by stimulating PS cells to secrete VEGF or inhibit neo angiogenesis by increasing endostatin secretion. B. Relationship between insulin resistance and pancreatic cancer development and survival. Insulin resistance can lead to increased insulin and glucose in the blood. When the level of IGF-1 is low in the tumor microenviroment, IGFRs and IRs that can be overexpressed on cancer cells are free for insulin to bind and stimulate cancer cell growth. Furthermore, downstream signaling of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway can sustain cellular survival through the synthesis of anti-apoptotic proteins. Under hypoxic conditions, insulin can mediate VEGF secretion from pancreatic cancer cells via expression of HIF-1α. Elevated levels of blood glucose may also stimulate VEGF.

AKT (protein kinase B); HIF-1 α (hypoxia inducible factor-1α); IGFR (insulin-like growth factor receptor); IR (insulin receptor) IRS (insulin receptor substrate); MMP (matrix metalloprotease); mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) PI3K (Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases) ROS (reactive oxygen species) VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor).

Endothelial cells line all blood vessels and without a constant blood supply tumors cannot enlarge beyond 1–2 mm and cannot grow at distal sites103. Hence, angiogenesis involves the growth of these cells. The factors that can promote angiogenesis are VEGF, FGF-2, TGF-β1 and PDGF102–105. The most potent of which is VEGF type A, a soluble growth factor commonly known as VEGF. Soluble VEGF binds to the VEGF tyrosine kinase receptors type 1, 2, 3 (VEGFR-1, 2, 3). VEGFR-2 is restricted to endothelial cells. VEGF/VEGFR2 complexes on endothelial cells can result in several downstream events that promote angiogenesis103. Neuropilin-1 (NRP-1) and neuropilin-2 (NRP-2) are co-receptors for VEGFRs on endothelial cells114. Recently, it was reported that NRP-1 and NRP-2 are expressed on tumor cells115 and their expression correlates with a more malignant phenotype116,117. In vivo, decreased expression of NRP-2 in PDAC slowed tumor growth. The inhibition of tumor growth was attributed to indirect effects on angiogenesis as opposed to anti-proliferative effects on tumor cells111, making NRP-2 a potential therapeutic target as recently reviewed by Muders et al. (2011)118,119. This study, as well as others, support the idea that the normal balance between pro- and anti-angiogenic effects can be lost in PDAC. Although PDAC is not considered a “vascular” tumor, it has areas of enhanced endothelial cell proliferation with significant correlations between blood vessel density and disease progression suggesting that anti-angiogenic targets might be attractive candidates for anti-tumor therapy. Moreover, although anti-angiogenic strategies that target VEGF alone have not yet shown efficacy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer, some anti-angiogenic molecules have been shown to reduce the immunosuppression associated with cancer120. In a review by Tartour et al. (2011) the link between angiogenesis and immunity is discussed120. In brief, anti-angiogenic molecules can decrease immunosuppressive cells (MDSC, Treg cells), immunosuppressive cytokines (IL-10 and TGF-β), as well as inhibitory molecules (PD-1)120. This suggests that anti-angiogenic therapy may be most beneficial when used in conjunction with immunotherapy.

Endocrine cells play a role in the development and progression of pancreatic cancer has not been well established. In vitro studies have demonstrated that insulin can enhance the growth of pancreatic tumor cells121. However, in patients with PDAC the association of hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia is questionable122. Although the link between endocrine disturbances such as diabetes and pancreatic cancer is still under debate122 it is hypothesized that increased proliferation and function of beta cells as a result of systemic insulin tolerance is involved in the progression of pancreatic cancer123. Patients with type II diabetes become unresponsive to insulin and the pancreas compensates by producing more insulin. Insulin can act as a tumor growth factor when tumor cells over express both insulin receptor substrates, 1 and 2, as is the case for pancreatic cancer124,125. Insulin can also act as a growth factor when circulating IGF-1 is low126 and the IGF-1 receptor is available to bind to insulin. Moreover, IGF-1R activation also leads to the activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) -mediated PI3K/Akt pathway, providing anti-apoptotic signals to the cell127. Thus the inhibitions of IGF-1/IGF-1R activity as well as mTOR are potential therapeutic targets for pancreatic cancer127. In addition, under hypoxic conditions insulin can also stimulate the expression of hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) in pancreatic cancer cells128,129 thereby promoting angiogenesis and further tumor development. Moreover, hyperglycemia can stimulate the expression of VEGF by human vascular smooth muscle cells130. This demonstrates a potential role for hyperglycemia in endothelial cell dysfunction130. Patients with type II diabetes can have impaired immune cell functions, particularly with regard of neutrophils and cytokines leading to an immunosuppressive state. Thus, endocrine cell dysfunction and its relationship to the development and progression of PDAC may be more closely related then is currently appreciated (Figure 1B).

Section IV: Immune Failure and Tumor Escape in PDAC

Tumor cell escape involves a complex network of dynamic interactions among cells of the tumor, the immune system and the stroma. Although we assume that the immune response in PDAC has the potential to eliminate tumor cells, during cancerogenesis, it is possible that the immune system is activated but fails to eliminate the tumor. For example:

The tumor antigens are not recognized as foreign or dangerous.

The activation of the response is either not rapid or robust enough to eradicate the tumor cells in early stages. In late stages, tumors grow too rapidly to be controlled by Tc cells.

Antigens, to which an immune response has been generated, signal cytokine overproduction that alter the immune response or actually suppress/kill cells of the immune system.

The immune system can also provide a “pro-tumor response”, whereby components of the immune response can stimulate the growth of tumor cells themselves or dampen (alter) the anti-tumor immune response.

The products of the immune system such as antibodies, activated T cells and cytokines might also have many collateral effects on normal tissues causing immune dysregulation as well as tissue damage.

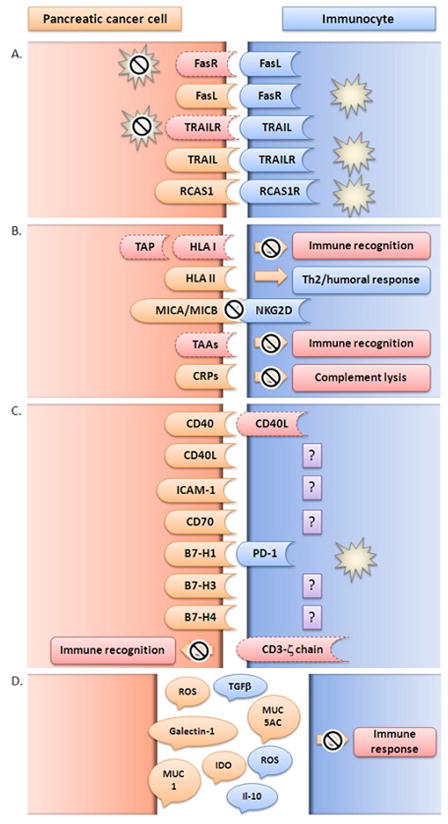

Clearly, there are a variety of other mechanisms that might also be involved in the ability of tumor cells to evade or circumvent the immune system either during the activation phase or the effector phase of the immune response. This is not a new concept and it has been extensively reviewed131–133. However, the likelihood for several more mechanisms that have yet to be elucidated is high. A general view of tumor escape in pancreatic cancer is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Mechanisms of tumor escape in PDAC development and survival.

A. Pancreatic cancer cells avoid apoptosis induced by immune cells and/or induce apoptosis in immunocytes. cancer cells manipulate ‘extrinsic’ apoptotic pathways through up-regulation of apoptotic inducing ligands (FasL, TRAIL, RCAS1) or down-regulation of apoptotic receptors (Fas, TRAILR, RCAS1R); B. Pancreatic cancer cells avoid immune detection and the effector phase of the immune response. Cancerogenesis is a dynamic sum of multiple genomic and proteomic alterations with the final result of vast heterogeneity in expression of molecules responsible for immune regulation such as HLA, MICA/MICB, TAA or CRP; C. Pancreatic cancer cells promote suppression and/or alteration of immune response. Aberrant expression of immune co-stimulatory molecules (CD40, CD40L, CD70, B7 family molecules) and adhesion molecules (ICAM-1) as well as loss of molecules necessary for immune recognition (CD3-ζ) by cancer cells leads to disruption of the immune response allowing tumor progression and invasion; D. Pancreatic cancer cells and immunocytes secrete immunosuppressive factors (TGF-β, IL-10, MUC1, MUC5AC, IDO, Galectin-1, ROS) that can dampen the immune response in the tumor microenvironment.

B7-H1 (PD-L1, programmed death-1 ligand, PD-L1); B7-H3 (CD276, co-stimulatory molecule belonging to B7 family); B7-H4 (co-stimulatory molecule belonging to B7 family); CD3-ζ (T cell co-receptor-zeta chain); CD40 (tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 5); CD40L (CD40-ligand, CD154); CD70 (tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 7); CRP (complement regulatory protein); FasL (Fas ligand, CD95L); FasR (Fas receptor, CD95, Apo-1 tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6); ICAM-1 (inter-cellular adhesion molecule 1CD54); IDO (Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase); IL-10 (interleukin 10); HLA (human leukocyte antigen); MICA/MICB (major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related genes A and B; MUC1 (mucin 1); MUC5AC (mucin 5AC); NKG2D (natural killer cell receptor); PD-1 (programmed death 1); RCAS1 (receptor-binding cancer antigen 1); RCAS1R (receptor-binding cancer antigen 1 receptor); ROS (reactive oxygen species); TAA (tumor-associated antigen); TAP (tumor-associated antigens); TGF- β (transforming growth factor beta); Th2 (T helper type 2 lymphocytes); TRAIL (tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand); TRAILR (tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor).

Pancreatic tumor cells can “escape” immune surveillance by several mechanisms. They can avoid apoptosis, immune detection and the effector phase of the immune system, and kill tumor specific Tc cells. Moreover, pancreatic tumor cells can migrate to other tissues and promote immune suppression and dysregulation. This raises the question of whether “tumor escape” is a true failure of the immune system to recognize an altered normal cell and mount an anti-tumor response or whether the tumor cells silence and/or attack the immune system. Indeed both might occur.

Tumor Cells Avoid Undergoing Apoptosis and Induce Apoptosis in Other Cells

Apoptosis is natural programmed non-necrotic cell death. It plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis as well as immune-mediated cell killing. PDAC cells have developed several mechanisms to avoid undergoing apoptosis and or induce apoptosis in immune cells (Tc cells) and surrounding normal epithelial cells. Either mechanism could promote tumor progression. Samm et al. (2010) extensively reviewed the role of apoptosis in the pathology of pancreatic cancer demonstrating a correlation between disease occurrence with failures in apoptotic mechanisms134. This section will review the key apoptotic evasion strategies employed by PDAC cells.

Apoptosis can normally occur through ‘extrinsic’ or ‘intrinsic’ pathways. Death receptors (DRs), Fas (CD95, Apo-1), TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor, (TRAILR, Apo-2) and TNF receptor, and their corresponding ligands FasL, TRAIL and TNF-α mediate the extrinsic pathway. Pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules of the mitochondria mediate the intrinsic pathway. Molecules involved in apoptotic pathways are ideal targets for killing tumor cells particularly if they are over-expressed. However in PDAC, tumor cells have developed mechanisms to down-regulate apoptotic receptors and/or up-regulate the apoptosis-inducing ligands as well as mutate regulatory apoptotic pathways.

The FAS System is comprised of Fas ligand (FasL) that when bound to Fas receptor (CD95) can induce apoptosis in cells that express functional Fas receptor135. Tumor escape can be achieved through down-regulation or loss of Fas, dysfunctional Fas signal transduction or expression of functional FasL136,137. In PDAC, Fas is expressed on the majority of established cell lines. However, most are resistant to Fas-ligand-mediated apoptosis137–139. This resistance can be attributed to Fas-associated phosphatase-1, an inhibitor of Fas signal transduction, that is over-expressed in Fas-resistant pancreatic cancer cell lines137,140. However, several pancreatic cancer cell lines and surgical specimens express functional FasL allowing these tumor cells to induce apoptosis in activated Tc cells137,141,142 as well as other FasR expressing cell types.

TRAIL can induce apoptosis in susceptible cells through interaction with membrane receptors DR4 and DR5143 and decoy receptors DcR1 and DcR2144. The TRAIL death receptor pathway is regulated by inhibitory proteins such as bcl-2-related proteins, bcl-2, bcl-xL and fas-like IL-1 converting enzyme (FLICE)-like inhibitor protein and stimulated by Bax145. Pancreatic cancer cell lines are heterogeneous in their expression of TRAIL, its receptors DR4, DR5, DcR1 and DcR2 as well as regulatory proteins Bax and bcl-2 and bcl-xL146. Therefore, some pancreatic cancer cell lines are susceptible to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis whereas others are completely resistant146. The cell lines that express TRAIL can induce apoptosis in tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) as well as other TRAIL-receptor expressing cell types. This provides TRAIL- expressing tumor cells with a way to escape the immune system. It also confers a growth advantage for an aggressive tumor cell by eliminating the less aggressive clones146,147. In addition, this promotes metastasis through the apoptosis of surrounding normal cells148. Initially, TRAIL-based therapy was postulated to be a good treatment option for PDAC considering that high TRAIL expression correlated with an increased apoptotic index149,150. Unfortunately, primary human tumors are often resistant to TRAIL-induced apoptosis despite the expression of TRAIL receptors, DR4 and DR5 as well as the mediators for the pathway151–155. Several proteins that can promote resistance to TRAIL-mediated killing in PDAC have been identified and these include: histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2)154, STAT3156, CUX1157, cFLIP158–160, XIAP161–165, MCL1156,166, bclXL156,167,168 or surviving169, and SKP2155. Due to the heterogeneity in tumors from different patients immunotherapy targeted to TRAIL could be beneficial in some, but not all patients with pancreatic cancer.

RCAS1 (receptor-binding cancer antigen 1) was identified from cancer cells and can induce apoptosis in immune cells that express RCAS-1-receptor (RCAS1R)170. Although evidence for the role of RCAS1 in PDAC is limited, a few studies have found trends in tumor cell positivity and up-regulation of RCAS1, correlating to histopathologic grade and poor patient prognosis, respectively171–173. This suggests that up-regulation of RCAS1 may play an important role in PDAC progression by evading the immune system. However, further investigation is warranted. In addition, increased serum levels of RCAS1 correlated with tumor stage and when compared to CA19-9, RCAS1 showed greater fidelity as a diagnostic marker for pancreatic cancer. However, when used together, diagnostic efficiency was enhanced172.

Both pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules of the mitochondria mediate the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. In PDAC, alterations of the Bcl-2 protein family regulated intra-mitochondrial signal transduction pathway have been reported134. Tumor cells promote their own survival, progression and metastasis by manipulating both ‘intrinsic’ and ‘extrinsic’ apoptotic pathways.

Tumor Cells Avoid Immune Detection and the Effector Phase of the Immune System

Normal cells undergo many alterations in the progression to adult cancer cells. These alterations can be advantageous to the tumor cell and lead to down-or up-regulation of various genes and their corresponding expression of molecules such as HLA, TAAs or complement regulatory proteins (CRPs). In addition, alterations can lead to expression of abnormal genes and proteins that can provide specific targets for therapy.

Dysregulation of HLA

For the immune system to initiate a response against a tumor, DCs must transport tumor antigens to the regional lymph nodes. Tumor antigens are processed with the help of transporter for antigen presentation (TAP), and presented to T cells by HLA class I and class II molecules on the surface of DCs. For the tumor cells to be killed by the resulting Tc cells, they must express the specific tumor antigens in class I molecules. In PDAC, tumor cells down-regulate or lose expression of HLA class I, its associated β2-microglobulin174 and TAP175. Therefore, some tumor cells no longer present antigen to immune cells and avoid immune detection as well as killing by Tc cells. Although this does render them sensitive to NK cell-mediated killing, NK cells are far less effective in eliminating tumor cells.

Tumor cells can express HLA class II molecules de novo175. This suggests that tumor cells are promoting a Th2/humoral immune response, by influencing the type of HLA molecule expressed on their cell surface. Ultimately, this can have detrimental effects on tumor cell killing by preventing cellular immunity, i.e. Tc cells, and promoting humoral immunity, i.e. Th cells. Interestingly however, it has been reported that HLA class I and TAP expression can be re-induced in PDAC cell lines in vitro by treatment with IFN-γ175 thus providing a possible means of altering the balance between cellular and humoral immunity by promoting Th1/cell-mediated immunity.

HLA related molecules, MHC class I chain-related genes A and B (MICA/MICB), are intestinal surface glycoproteins that can be up-regulated in response to stress or by epithelial tumors176. MICA/MICB are ligands for the NKG2D activating receptor found on NK and gamma delta T cells of the immune system. NK cells can recognize cells that either down-regulate MHC antigens or completely lose HLA class I molecules. In PDAC, cells express MIC and sera from PDAC patients contain elevated levels of soluble MIC (sMIC) that correlate to tumor stage and differentiation177. Moreover, sMIC in the sera of patients with PDAC can inhibit the cellular cytotoxicity of NK and gamma/delta T cells, thereby inhibiting the ability of the innate immune response to eliminate PDAC cells177.

Down-regulation of TAAs

Tumor cells can up-regulate normally expressed molecules as well as express abnormal self-molecules. These phenomena are some of the main factors driving the development of targeted immunotherapy. Unfortunately, after tumor cells “escape” from immune surveillance, they often become “resistant” to TAA-specific induced immune effector cells. In addition, as the more aggressive tumor cells differentiate, the expression of TAAs can mutate or decrease to a point of complete loss of expression from the surface of the remaining tumor cells.

Expression of CRPs

Complement inhibitors CD46 (membrane cofactor protein), CD55 (complement decay accelerating factor), and CD59 (protectin) can protect tumor cells from lysis by activated complement178–180. PDAC cell lines express high levels of these molecules on their surface (unpublished results, Pop, Vitetta et al.). This suggests that tumor cells are able to regulate complement- dependent effector functions. Hence anti-tumor antibodies made by the host or administered therapeutically (e.g., anti-CA19.9) would fail to kill the tumor cells by C’ mediated lysis181.

Tumor Cells Promote Immune Suppression and Immune Dysfunction Co-stimulatory Molecules

Interestingly, in tumor progression, tumor cells can also aberrantly express T cell co-stimulatory molecules. These molecules are typically limited to cells of the immune system and are involved in lymphocyte signaling pathways. The over-expression of these molecules by tumor cells can lead to either amplification or dampening of local immunity with devastating consequences for normal body physiology. For example, tumor cells that express inhibitory co-stimulatory molecules can suppress or eliminate specific anti-tumor immunocytes, thereby allowing the tumor to progress. On the other hand, tumor cells that express activating co-stimulatory molecules can enhance the immune response such that the inflammatory milieu causes damage to the surrounding normal tissue and results in further progression of tumor growth.

The B7 super family are co-stimulatory molecules expressed on antigen presenting cells that included; B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) and their receptors CD28 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), as well as the B7-homolog molecules B7-H1, B7-DC (B7-DC), B7-H2, B7-H3 and B7-H4. In the immune response, T cells and antigen-MHC complexes determine specificity whereas the co-stimulatory molecules of the B7 family determine the magnitude and type of immune response. Therefore, the B7 ligands can provide an activating or inhibitory signal depending upon the receptor bound and the influence of the local environment182.

The B7/CD28 and B7/CTLA-4 systems are T cell co-stimulatory pathways that act on antigen-presenting cells and T cells. The B7/CD28 interaction promotes T and B cell activation, Th1/Th2 differentiation, cell migration, and homeostasis of CD25+CD4+ Treg cells183. In contrast, B7/CTLA-4 interactions downregulate T cell function and ongoing immune responses as well as help maintain peripheral tolerance183. By blocking co-stimulatory pathways, specific clones of activated T cells are turned off183. This pathway has been explored in developing strategies for immune intervention therapies (discussed in the therapy section).

B7-H1 (Programmed death-1 ligand, PD-L1; CD274) and B7-DC (PD-L2; CD273) are cell surface ligands for programmed death-1 (PD-1) receptor that is expressed on activated T cells, B cells and monocytes184–188. The expression of B7-H1 is induced by IFN-γ on several cells types189,190. The expression of B7-DC is limited to DCs and activated macrophages and induced by IL-4 and IL-13191. Both ligands can induce PD-1 to negatively regulate both cellular and humoral immune responses184,188,189,192. However, the interaction of B7-DC with PD-1193 also has stimulatory effects suggesting another receptor interaction or influence of other environmental factors189,194. B7-H1 inhibits anti-tumoral T-cell immunity by interacting with PD-1 on T cells resulting in tumor-specific T cell apoptosis or impaired cytotoxicity and cytokine production by activated T cells195–198. In addition, ligation of B7-H1 to T-cells can result in the preferential production of IL-10199,200. IL-10 is an immunosuppressive cytokine that can inhibit Th1 type immune responses201,202 by modulating antigen presenting cells (APCs) and DC function and promoting Treg cell responses203,204. In PDAC, the expression of both B7-H1 and IL-10 is up-regulated as compared to normal tissues. The expression of B7-H1 correlates with advanced tumor stage and poor prognosis and is inversely correlated with TILs188,205. This suggests that tumor cells are expressing B7-H1 to suppress the anti-tumor immune responses while promoting the production of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10. Furthermore, in an in vivo mouse model of pancreatic cancer, blocking the B7-H1, B7-DC206 or the PD-Ls/PD-1 pathways188 with MAbs can induce anti-tumor effects and promote infiltration of T cells into the tumor188,206. This is important because it identifies specific molecules in pathways that can be therapeutically targeted in order to restore the anti-tumor immune response. Moreover, the B7-DC blockade decreases IL-10 and FoxP3 levels whereas B7-H1 blockade increases IFN-γ and FoxP3 in the tumor site206. Thus further demonstrating the important role of each ligand not just as specific Tc cell inhibitors but also as general immunosupressors involving Treg cells. As we better understand the mechanisms by which tumor cells inhibit anti-tumor response, we can design more effective therapies.

Although no studies to date report the expression of B7-H2 (CD275) on pancreatic cancer cells it would not be surprising if it were expressed.

The role of B7-H3 (CD276) in anti-tumor immunity was recently reviewed by Loos et al. (2010) and will be briefly discussed in this section207. B7-H3 is expressed on several non-immune cell types throughout the body. However, its expression can be induced on activated DCs, monocytes, T cells and some tumor cell lines208–211. The role of B7-H3 in immune regulation is controversial due to the fact that both stimulatory and inhibitory immune functions have been reported and possibly attributed to two distinct receptors207–216. However, only one receptor has been identified, it is the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM)-like transcription 2 (TLT-2)217. The interaction of B7-H3 with TLT-2 on T cells enhances T cell activation, proliferation, cytokine production and cytotoxicity217. In PDAC, B7-H3 tumor- related expression has been reported to be significantly higher than in non-cancer tissue or normal pancreas218. Its expression correlated with lymph node metastasis and advanced pathologic stage218. In an in vivo mouse model of pancreatic cancer, B7-H3 blockade promoted CD8+ T cell infiltration into the tumor and induced substantial anti-tumor effects that were synergistic with gemcitabine218.

B7-H4 is expressed predominantly on human epithelial cells of the female genital tract, kidney, lung and pancreas with low/no expression on other cell types219,220. Although the receptor for B7-H4 is unknown, the expression of B7-H4 can be induced on monocytes, macrophages and myeloid DCs by both IL-6 and IL-10 and down-regulated by GM-CSF and IL-4221–223. Much remains to be elucidated concerning the role of B7-H4 in immune regulation. However, studies have shown that B7-H4 inhibits the proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as cytokine production by inducing cell cycle arrest224–226. B7-H4 is highly expressed on several human cancers219,220 and although data are limited, one study has investigated the expression of B7-H4 in PDAC. B7-H4 was expressed more often than p53, a potential marker for pancreatic cancer, and B7-H4 positive tumor cells were inversely correlated to tumor grade227. These findings suggest an early induction followed by loss of B7-H4 expression leading to a decrease in tumor-associated immunogenicity in higher-grade tumors227. The role of B7-H4 in normal pancreatic tissue has not been investigated. However B7-H4 interactions in normal pancreas may block T cell-mediated immunity where as in PDAC, this protection may be lost due to B7-H4 expression227.

CD40 is a membrane glycoprotein member of the TNF receptor family. It is expressed on several cell types including B lymphocytes, DCs and monocytes228–230. Its ligand, CD154 (CD40L), is expressed on the surface of T cells. The interaction of CD40+ B cells with CD154+ T cells induces B cell proliferation, immunoglobulin production, somatic hypermutation of B cell receptors and immunoglobulin class-switching231–234. The interaction of CD40+ DCs, and CD154+ T cells leads to up-regulation of co-stimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86) on APC cells to help T cell activation, proliferation and cytokine expression235. The normal expression and interaction of CD40 and CD154 by immune cells results in the proliferation of the immune response with the potential to ultimately affect anti-tumor immunity. In a recent study by Shoji et al. (2011) it was found that both CD40 and CD154 are expressed by PDAC cell lines and patient specimens and although the study did not directly evaluate TILs they found the frequency of CD154 expression on TILs to be low in their xenograft model236. These findings suggest that PDAC cells can potentially use CD40 and CD154 expression as an autocrine mechanism to promote tumor cell proliferation as well as potentially alter CD154 expression on TILs. This alteration may be explained by the ligation of CD40 on PDAC cells inducing the secretion of several types of pro and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, IL-12) as found by Shoji et al. (2011). Moreover, studies on other malignant cell types support the secretion of cytokines following CD40 ligation237–239. The balance of pro-versus anti-tumor immune response can tip in favor of either response or remain in equilibrium based upon the expression of surface molecules by tumor cells, immune cells, stromal cells as well as the factors that they release. A good example of this was the finding that very high expression of CD154 in patient specimens correlated with a favorable prognosis236. On the one hand, PDAC cells promote their own growth with the expression of CD40-CD154 and immune cell suppression with secretion of IL-10. The ligation of CD40 on these tumor cells leads to the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-12 that could ultimately result in an anti-tumor response. These seemingly contradictory findings within the same study best illustrate the complexity of the tumor-immune system interactions. Moreover, when pancreatic cancer patients were treated with an agonist CD40 antibody and gemcitabine chemotherapy tumor regression was observed240. When Beatty et al. (2011) evaluated this effect in a mouse model of PDAC they found that CD40-activated macrophages but not T cells nor gemcitabine infiltrated tumors and mediated tumor regression and depletion of tumor stromal cells240.

CD54 (inter-cellular adhesion molecule 1, ICAM-1) exists in both membrane-bound and soluble forms. The adhesion molecule CD54 is expressed on several different cell types241–243 and can be secreted as soluble CD54 (sCD54) by mononuclear cells, endothelial cells, keratinocytes, hepatocytes and some tumor cells244. The regulation of sCD54 is not well understood, but TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1 can induce the expression of membrane-bound CD54 while, glucocorticoids are the most well known inhibitors241–243. CD54 binds to the β2 integrins lymphocyte function-associated antigen (LFA-1; CD11a/CD18) and macrophage 1 (Mac-1; CD11b/CD18) on leukocytes, as well as sialophorin (CD43) on leukocytes and platelets and soluble fibrinogen242,245,246. It functions predominantly as an adhesion molecule, but it can elicit a variety of effects including T cell and NK cell activation and leukocyte migration242,245,246. CD54 is associated with disease states characterized by local or systemic inflammation247,248 and although CD54 is not tumor specific and is expressed on many normal cells in humans, it can play a crucial role in the tumor microenvironment. It has been hypothesized that CD54 dictates the metastatic potential and lethality of many types of cancer cells249. The over-expression of CD54 at the leading edge of tumor invasion has been correlated with a poor patient prognosis250. Although no published studies have evaluated the role of CD54 in pancreatic cancer, our unpublished data derived from pancreatic cell lines suggest that its expression is down-regulated or lost on some PDAC cell lines.

CD70 (TNFSF7) ligand is a member of the TNF superfamily that interacts with CD27. The interaction of CD70 ligand with CD27 regulates long-term maintenance of T cell immunity as well as B-cell activation and immunoglobulin synthesis251–260. CD70 expression is normally limited to antigen-activated T and B lymphocytes254,261,262 and is found infrequently in a few other normal cell types263,264. However, aberrant expression of CD70 has been reported in several tumor types including pancreatic cancer cells265–269. Since CD70 expression has a limited normal distribution and aberrant cell surface expression in tumors, CD70 makes an attractive target for therapy269. In an in vivo model of human pancreatic cancer, mice were treated with an anti-CD70 drug conjugate (SGN-75) all 7 mice treated showed a delay in tumor growth with 2 of 7mice showing a complete and sustained regression269.

Loss of CD3-zeta Chain Expression

The T cell receptor (TCR)/CD3-zeta chain is a crucial component in the T cell signal transduction complex. Although it is important for the initial activation of Tc cells in the regional lymph node, and not in the effector function of Tc cells at the tumor site, it is important to note that specimens from PDAC patients have shown significant down-regulation or loss of TCRs/CD3-zeta chains on TILs137. The significance of this finding has yet to be determined but it is proposed that environmental factors such as ROS and arginase produced by macrophages in tumor sites can decrease the expression of TCRs on effector T cells such that they can no longer recognize the tumor antigens expressed in HLA class I molecules. Thus, the effector T cells in the tumor microenvironment might not recognize their target cells and hence, not kill them.

Production and Secretion of Immunosuppressive Factors

A more global mechanism of PDAC tumor escape is the production and secretion of immunosuppressive molecules. In addition to several preciously mentioned immunosuppressive molecules, PDAC cells can produce and secrete TGF-β, MUC1, MUC5AC, Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase (IDO), Galectin-1 (Gal-1), and ROS.

The role of TGF-β270 in blocking the activation of lymphocytes and monocytes has been covered in other sections of this review. However, its role in tumor cells will be addressed here. In PDAC, TGF-β has been shown to up-regulate proteases such as MMP-2 and urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA)271, to down-regulate cell surface CD54272 and to stimulate the secretion of VEGF by tumor cells271. These effects can result in degradation of the extracellular matrix, thereby promoting tumor cell invasion and metastasis while providing an angiogenic stimulus to promote further development. Moreover, TGF-β2 has been shown to induce PDAC cells to express functional Foxp3, possibly allowing tumor cells to mimic the function of Treg cells273. This suggests another mechanism by which tumor cells can suppress anti-tumor responses, by functioning as suppressor cells themselves.

MUC1 is an epithelial cell membrane-bound glycoprotein that is approximately 80% carbohydrate274,275. It is associated with the progression of normal pancreatic ductal cells to infiltrating ductal carcinoma and has been shown to enhance the invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells by inducing an epithelial to mesenchymal transition276–282. MUC1 is also an immunogen that elicits CD8+ T cell responses23 and induces the production of anti-MUC1 antibodies of both the IgM and IgG isotypes24,25. Increased serum levels of anti-MUC1 antibodies correlate with increased patient survival25. Tumor-derived mucin has been shown to profoundly affect the cytokine repertoire of monocyte-derived DCs, producing regulatory APCs (IL-10highIL-12low) that lead to a Th1 immune response283. Again, this supports the hypothesis that the tumor cells do elicit an anti-tumor immune response. However, it is either not robust enough or is quickly thwarted by other escape mechanisms employed by tumor cells. To better elucidate the immunosuppressive effects of MUC1, Tinder et al. (2008) compared pancreatic tumors that expressed MUC1 to those that lacked MUC1 expression in a mouse model of spontaneous PDAC284. The tumors derived from MUC1+ mice expressed higher levels of COX-2 and IDO compared with tumors from MUC1− mice especially during early stages of development. In addition, MUC1+ mice had an increased pro-inflammatory milieu with elevated levels of Treg cells and myeloid suppressor cells within the tumor and draining lymph nodes284. In subsequent in vivo studies, Besmer et al. (2011) showed that MUC1− mice have significantly slower tumor progression and rates of metastasis285. Moreover, from their in vitro studies it is suggested that MUC1 is necessary for MAPK activity and oncogenic signaling285. MUC1-mediated mechanisms can enhance the onset and progression of the disease, which in turn, regulate the immune response284. It is possible that early in disease MUC1 expression is recognized by the immune system and initially promotes a robust Th1 anti-tumor immune response. However, over time the progressive inflammation can evoke an immunosuppressive response established either by the efforts of the immune system to maintain balance or the attempts by the tumor cells to suppress the response.

MUC5AC, another glycoprotein from the mucin family, is over-expressed only by PDAC cells and not by normal pancreatic cells. A recent study revealed that by knocking down MUC5AC expression of wild-type MUC5AC positive pancreatic cell lines by siRNA, there was a decrease in tumorigenicity and tumor development286. This suggests that MUC5AC expression may play an important role in the development of PDAC as well as provide a potential tumor specific target for therapy.

The up-regulation of enzymes or proteins crucial for immune cell function can be an important mechanism by which tumor cells control the tumor environment and prevent tumor specific immune responses. IDO is an IFN-γ induced immune regulatory enzyme that catabolizes tryptophan287. IDO can create an immunosuppressive environment by deleting tryptophan, a crucial metabolite for T cells undergoing antigen-dependent activation, ultimately leading to T cell arrest, anergy or death288–291. In PDAC up-regulation of IDO in tumor cells is associated with an increased number of Treg cells289. Recently, another immunoregulatory molecule secreted by pancreatic tumor cells and activated pancreatic stellate cells, Gal-1 was identified292. Gal-1 is a carbohydrate- binding protein that is thought to be a regulator of T cell homeostasis, survival and inflammation293,294. Up-regulation of Gal-1 was suggested to induce apoptosis in T cells, activation of DCs, regulate immune cell trafficking and promote proliferation and invasion of tumor cells294,295. Thus PDAC cells can employ basic nutrient metabolism and secretion of immunosuppressive factors to locally regulate the immune response.

Although ROS is mainly implicated to promote cell death and is a key component of immune defense against invading microbes296–299 there is increasing evidence to suggest that it also plays a role in cell survival and signaling300–304. We previously reviewed ROS as products of neutrophils as well as macrophages. However, PDAC cells have been reported to produce ROS as well305. In a study by Vaquero et al. (2004), when PDAC cells were stimulated by IGF-I or FGF-2 they produced ROS which protected the cells from apoptosis305. It has been proposed that tumor cells require the presence of chemotactic molecules for growth, invasion and metastasis. Ultimately these “homing factors” may promote immune escape.

Strong expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 has been reported to correlate with advanced pancreatic cancer306. There is much more that remains to be uncovered about the role of CXCR4 and other chemotactic molecules in PDAC.

Unfortunately, tumor escape from normal immunity is not the main or only mechanism by which tumor cells survive. Genetic alterations and microenvironment factors that both promote tumor cell development and eliminate less robust tumor cells ultimately produce immortal cells with an infinite capacity for reproduction, if nutrients are available. In this regard, the precursors of cancer stem cells can evolve into new blood vessel progenitors307 and adult cancer cells, especially in hypoxic states, can induce and sustain new blood vessel formation that ensures nutrient supply for further tumor growth. Moreover, one of the most potent angiogenic factors, VEGF, is also an immunosuppressive molecule secreted by tumor cells308. Thus, as a part of the extraordinary innate and acquired abilities of tumor cells to defeat the host, they develop a variety of ‘escape’ mechanisms that can overcome almost any anti-tumor approach. However, the lessons learned from the various ways tumor cells continually adapt to ensure their survival should be used to develop rational multi-targeted immunotherapies.

Section V: A role for Immunotherapy in PDAC

The dismal prognosis of PDAC is due to late detection and limited treatment options. It is often diagnosed at an advanced stage of disease when the tumor is inoperable and frequently resistant to standard therapy. Clinical trials in patients with PDAC have focused on improving both surgery and radiation therapy as well as determining better drug-treatment combinations. Despite this, PDAC is almost uniformly fatal.

Several biological approaches have been studied for the treatment of pancreatic cancer, e.g. gene therapy, signal transduction modulators, anti-angiogenics, MMP inhibitors, oncolytic viral therapy, as well as immunotherapy. However, these have not improved patient survival as recently reviewed by Wong et al. (2008)309. It is important to note that clinical trials with targeted biologics are used in all patients with disease regardless of whether or not they express the target, making conclusions difficult and potentially erroneous. Several proposals have been made to address this issue by selecting patients with the appropriate targets on their tumors or in the tumor microenvironment310. Therefore, there is a need to establish the genetic and proteomic profile of the tumor cells in each patient as well as understand the key molecules involved in multi-drug resistance and use this information to successfully target the most effective agents to cells. This profile can be used to determine the treatment regimen as well as monitor responses to treatment. Ultimately, the hope is that by using this profile to screen study patients for the expression of the target in question in clinical trials with targeted therapeutics, we may actually begin to see clinically meaningful responses.

The rationale for immunotherapy is to augment a patient’s natural immune response to their pancreatic cancer or introduce components of an immune system to slow disease progression. The consequences of impaired immune function are significant. Tumor cells are capable of functioning as immunocytes with the ability to secrete immunosuppressive cytokines, ultimately impairing the immune system’s function to recognize TAAs and destroy tumor cells.

Currently, immunotherapy for PDAC is only available in clinical trials. There are several ongoing clinical trials to evaluate single-agent as well as combined cytotoxic therapy and combinations of targeted therapies (including MAbs)311. However, considering how refractory to conventional agents this disease is, clinical trials may offer the best treatment option as well as teach us how to define specific combinatorial therapy guidelines (e.g., dosing, timing, route of administration, adjuvant therapy, etc). Unfortunately, the benefits of immunotherapy have yet to meet initial expectations. Clinical studies have yielded undesirable results such as the stimulation of incorrect immune responses, cytokine storm, tumor progression and metastasis. From a mechanistic point of view, the failure of immunotherapy in treating pancreatic cancer is a consequence of the genomic instability inherent in cancer cells, which allow them to highjack immune defenses. Moreover, the potential existence of cancer stems cells may help explain tumor rescue and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a phenomena believed to play a role in tumor progression and the ineffectiveness of current therapy. PDAC research should accelerate the understanding of the rescue mechanisms (tumorigenicity, invasiveness and resistance to therapy, angiogenesis, etc.) that tumors employ through the self-renewal “stem cell” subpopulations. Understanding these cell types can provide a new avenue for cancer-targeted therapeutics, as well as identify the patients with high-risk of unfavorable disease evolution or recurrence.