Abstract

Chronic stress in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) underlies many degenerative and metabolic diseases involving apoptosis of vital cells. A well-established example is Autosomal Dominant Retinitis Pigmentosa (ADRP), an age-related retinal degenerative disease caused by mutant rhodopsins 1, 2. Similar mutant alleles of Drosophila rhodopsin-1 also impose stress on the ER and cause age-related retinal degeneration in that organism 3. Well-characterized signaling responses to ER-stress, referred to as the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) 4, induce various ER quality control genes that can suppress such retinal degeneration 5. However, how cells activate cell death programs after chronic ER-stress remains poorly understood. Here, we report the identification of a signaling pathway mediated by cdk5 and mekk1 required for ER-stress-induced apoptosis. Inactivation of these genes specifically suppressed apoptosis, without affecting other protective branches of the UPR. Cdk5 phosphorylates Mekk1, and together, activate the JNK pathway for apoptosis. Moreover, disruption of this pathway can delay the course of age-related retinal degeneration in a Drosophila model of ADRP. These findings establish a previously unrecognized branch of ER-stress response signaling involved in degenerative diseases.

Three branches of the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) are particularly well characterized in mammals and conserved in Drosophila 4. In brief, these pathways involve transmembrane proteins ATF6, IRE1 and PERK, respectively, that can sense stress in the ER lumen. ATF6 is a transcription factor anchored to the ER membrane that translocates to the nucleus after ER-stress triggers its proteolysis, and IRE1 is an endonuclease that activates the transcription factor XBP1 through an unconventional mRNA splicing mechanism. PERK is an ER-stress responsive kinase that mediates the translational activation of the transcription factor, ATF4. The predominant effect of these pathways is to reduce stress in the ER and help the cells return to their normal physiological state. Consistently, the major targets of these transcription factors include genes that encode ER chaperones, anti-oxidant proteins and those involved in misfolded protein degradation 6–8.

Our in vivo model for ER-stress-induced apoptosis is based on a mutant Drosophila Rhodopsin-1 (Rh-1) allele, Rh-1G69D, which is similar in nature with human rhodopsin mutants that underlie retinal degeneration in Autosomal Dominant Retinitis Pigmentosa (ADRP) 9, 10. While the endogenous allele causes late-onset retinal degeneration without affecting the external eye morphology, overexpression of this encoded protein in larval eye imaginal discs (during photoreceptor differentiation) led to an easily identifiable adult eye phenotype by eclosion (Figure 1A, B, Supplementary Figure S1B). The adult eye was abnormally small, indicative of massive cell loss, and the surviving eye tissue showed a glassy surface that was devoid of ommatidial structures. The effect of Rh-1G69D overexpression can be attributed to excessive ER-stress for the following reasons: The Rh-1G69D overexpression phenotype was suppressed by the co-expression of Drosophila hrd1 (Supplementary Figure S1C), which encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase dedicated to degrading misfolded ER proteins 5. In addition, we detected signs of ER stress using two independent reporters. One is the XBP1-EGFP reporter, which expresses EGFP in frame only when ER-stress stimulates IRE1-dependent XBP1 mRNA splicing 3. This reporter was activated in Rh-1G69D misexpressing imaginal discs while not active in control tissues (Supplementary Figure S1D, E). We were also able to detect signs of ER-stress through an antibody against Drosophila ATF4. This protein is encoded in the cryptocephal (crc) locus 11. As in mammals 12, we found that the Drosophila ATF4 expression was induced after ER stress (Supplementary Figure S1F, G, H). Expression of Rh-1G69D in eye imaginal discs also increased the level of endogenous superoxides as evidenced by Dihydroethidium (DHE) labeling (Supplementary Figure S1J, K), consistent with previous reports of elevated ROS in stressed ER 13–17. Co-expressing Hrd1 suppressed such induction of ATF4 and ROS (Supplementary Figure S1I, L), indicating that these markers appear as a result of misfolded protein overload in the ER.

Figure 1. Cdk5 and its regulatory subunit p35 (Cdk5alpha) are required for Rh-1G69D-induced apoptosis.

(A–C) External adult eye phenotypes caused by overexpressing Rh-1G69, together with lacZ (A), or with inverted repeat (IR) transgenes to knockdown lacZ (B) and cdk5 (C). Note a partial recovery of eye size upon cdk5 knockdown. (D–F) cdk5 knockdown does not affect the rough eye phenotype caused by p53-overexpression (E, F). (D) is a control fly eye with normal morphology. (G–J) Apoptosis in larval eye discs assessed through TUNEL (magenta). Misexpression of Rh-1G69D led to massive apoptosis (G), which was suppressed by knocking down cdk5 (H). Rh-1G69D-triggered apoptosis (I), was also suppressed in a p35 (cdk5alpha) −/−background (J). (K–M) cdk5 knockdown does not affect the degree of ATF4 protein induction (red) in response to Rh-1G69D misexpression. Shown are; a control eye disc (genotype, y, w) (K), a disc misexpressing Rh-1G69D together with a control lacZ transgene (L), or with a cdk5-IR transgene (M). (N–P) cdk5 knockdown does not affect the degree of XBP1 pathway activation, as assessed through the XBP1-EGFP reporter (green). Shown are; a control eye disc expressing XBP1-EGFP alone (N), or together with Rh-1G69D and lacZ (O), or with Rh-1G69D and cdk5-IR (P). (Q, R) Rh-1G69D-induced apoptosis in ATF4 (crc) −/− discs. TUNEL (magenta) shows Rh-1G69D-triggered apoptosis in crc+ (Q) and crc1 −/− discs (R). (S, T) Rh-1G69D-induced apoptosis (magenta) in ire1 −/− clones (marked by the absence of green). The image is a magnified view of the region overexpressing Rh-1G69D. TUNEL positive cells are found within the ire1 −/− clones. The scale bar in (G) represents 100 μm for panels (G–R). (S, T) 20 μm. Error bars show ±SEM. Genotypes: gmr-Gal4, UAS-Rh-1G69D/UAS-lacZ;UAS-dicer2/+ (A, G, L), gmr-Gal4, UAS-Rh-1G69D/UAS-lacZ-IR;UAS-dicer2/+ (B), gmr-Gal4, UAS-Rh-1G69D/UAS-cdk5-IR;UAS-dicer2/+ (C, H, M), gmr-Gal4/+ (D), gmr-Gal4,UAS-p53/+;UAS-dicer-2/+ (E), gmr-Gal4, UAS-p53/UAS-cdk5-IR;UAS-dicer2/+ (F), gmr-Gal4/UAS-Rh-1G69D;+/+ (I), gmr-Gal4, Df(p35)C2;UAS-Rh-1G69D, Df(p35)20C (J), y,w (K), gmr-Gal4/+;UAS-xbp1-EGFP/+ (N), gmr-Gal4, UAS-Rh-1G69D/UAS-lacZ;UAS-dicer2/UAS-xbp1-EGFP (O), gmr-Gal4, UAS-Rh-1G69D/UAS-cdk5-IR;UAS-dicer2/UAS-xbp1-EGFP (P), gmr-Gal4/UAS-Rh-1G69D (Q), gmr-Gal4, crc1/crc1, UAS-Rh-1G69D (R), gmr-Gal4, ey-flp/+; UAS-Rh-1G69D/+; FRT82, ire1f02170/FRT82, ubi-GFP (S, T).

An easily detectable adult eye phenotype allowed us to conduct an in vivo RNAi screen to identify genes required for Rh-1G69D-induced toxicity. We specifically focused on kinases and phosphatases that could serve as signaling proteins potentially linking the distressed ER and the apoptotic machinery. Of the196 protein kinases and 66 protein phosphatases encoded in the Drosophila genome 18, we were able to target 119 kinases and 39 phosphatases through RNAi mediated knock down, using a total of 276 inverted repeat transgenes available from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (Supplementary Information, Table 1). We found three lines that strongly suppressed the adult eye phenotype, two of which (VDRC35855 and VDRC35856) targeted Drosophila cdk5 (Figure 1C). Cdk5 is an atypical cyclin-dependent kinase with established roles in differentiated postmitotic cells, such as neurons, adipose tissue and pancreatic beta-islet cells 19–22. In mammals, Cdk5 is reportedly activated by various stress conditions, including those that disrupt ER function 23. Excessive activation of Cdk5 contributes to neurotoxicity in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Diseases models 24, 25. We found that cdk5 knockdown did not affect an independent cell death phenotype caused by p53-overexpression in the eye (Figure 1E, F). These results indicate that cdk5 mediates a specific signaling response to mutant Rh-1, rather than affecting the general cell death machinery. When eye imaginal discs were inspected, we noticed a dramatic reduction of TUNEL positive cells, indicating that cdk5 is required for apoptosis in this assay (Figure 1G, H). To test whether Cdk5 has a conserved role in mammals, we used mouse Min6 cells, which readily succumb to apoptosis when treated with tunicamycin (Supplementary Figure S2), a compound that inhibits protein glycosylation and cause stress in the ER 26. Knockdown of Cdk5 strongly suppressed tunicamycin-induced apoptosis, as assessed through TUNEL labeling (Supplementary Figure S2). Cdk5 levels did not change in response to Rh-1G69D expression (Figure 1U, V), suggesting that the protein is regulated by post-transcriptional mechanisms. In fact, Cdk5 activity is often regulated through its regulatory subunit, p35 (also known as Cdk5alpha)27. In a loss of function p35 (Cdk5alpha) background, the amount of apoptosis induced by Rh-1G69D expression was significantly reduced (Figure 1I, J), further confirming the role of Cdk5 in apoptosis.

To determine if the cdk5 knockdown condition suppresses apoptosis by reducing the overall stress levels in the ER, we labeled imaginal discs with the anti-ATF4 antibody. The degree of ATF4 induction in Rh-1G69D overexpressing eye discs was not affected by cdk5 knockdown (Figure 1K–M). We also assessed the extent of IRE1/XBP1 pathway activation, using the XBP1-EGFP reporter. Again, knockdown of cdk5 did not affect the degree of this ER stress reporter activation in response to Rh-1G69D expression (Figure 1N–P). These observations indicate that cdk5 mediates Rh-1G69D-induced apoptosis without affecting the overall levels of misfolded protein load in the ER. To further test if the ATF4 and IRE1/XBP1 pathways contribute to Rh-1G69D-induced apoptosis, we examined the degree of cell death in mutants that disrupt these pathways. In the loss of function ATF4 condition, crc −/− 32, the degree of Rh-1G69D-induced apoptosis was similar to those of the crc+ background (Figure 1Q, R). In the ire1 −/− mosaic clones, the degree of Rh-1G69D-induced apoptosis was increased (Figure 1S, T). Overall, these results show that ATF4 and IRE1 are not required for Rh-1G69D expression to induce apoptosis.

Independently, we performed a gene overexpression screen with Epgy2 lines 28 for modifiers of the gmr-Gal4 driven Rh-1 overexpression phenotype (Supplementary Figure S3). While a wild type Rh-1 transgene was used in this experimental setup, the system drives the expression of Rh-1 beyond the folding capacity of the imaginal disc cells, as indicated by the activation of ER stress reporters 5. We specifically screened 400 lines with insertions in the 3rd chromosomes that were associated with genes with annotated function and scored a total of six suppressors. Among these suppressors were expected ones, including a line associated with hrd1 (P{EPgy2}sip3[EY11980]), whose effect on the Rh-1G69D misexpression phenotype was independently validated in Supplementary Figure S1. Another expected suppressor line was P{EPgy2}th[EY00710], with P{EPgy2} element inserted upstream of the anti-apoptotic gene, Drosophila IAP1 (Diap1) 29, indicating that excessive apoptosis contributes to the Rh-1 overexpression phenotype.

We also identified an enhancer of the Rh-1 overexpression phenotype, EY02276, associated with the mekk1 locus. Previous studies have characterized mekk1 as an osmotic stress response gene that lies upstream of JNK and p38 kinases 30, 31. This line did not show any overexpression associated phenotype on its own, but enhanced the Rh-1 overexpression phenotype when co-expressed (Supplementary Figure S3). Conversely, the Rh-1G69D misexpression phenotype was suppressed in the mekk1ur-36 −/− background (Figure 2A–C). Upon inspection of imaginal discs, we found that the mekk1ur-36 −/− background almost completely suppressed apoptosis triggered by Rh-1G69D-overexpression (Figure 2D–F). To determine if mekk1 affects the overall levels of stress in the ER, we assessed the degree of XBP1-EGFP and ATF4 activation in eye imaginal discs overexpressing Rh-1G69D. We found no discernible difference between the mekk1+ and mekk1UR-36 −/− discs in the level of these ER stress reporters (Figure 2G–L), indicating that mekk1 specifically mediates the pro-apoptotic signaling response without affecting the degree of ER-stress. To further test the role of mekk1 in ER-stress-induced toxicity, we subjected mekk1 −/− adults to an independent assay, in which the flies were fed tunicamycin and their survival rate was monitored. While control wild type flies were vulnerable to this regimen, with only 15.7% of the flies surviving after 7 days of tunicamycin feeding, the survival rate of mekk1 −/− flies was much higher under identical conditions (57.8%). Three independent trials of this assay gave a statistically significant difference in the survival rate of mekk1 mutant flies (p=0.0062) (Figure 2M).

Figure 2. Drosophila Mekk1 is required for Rh-1G69D to trigger apoptosis.

(A–C) External adult eyes. A control adult eye with wild type morphology is shown in (A). The degree of eye ablation as a result of Rh-1G69D misexpression (B), was suppressed in a mekk1ur-36 −/− background (C). (D–F) Apoptosis in eye discs as assessed through TUNEL labeling (magenta). A control eye disc shows little apoptosis (D). Massive apoptosis caused by Rh-1G69D misexpression (E), is strongly suppressed in a mekk1ur-36 −/− background (F). (G–I) The degree of ER-stress as estimated through the xbp1-EGFP reporter (green). Control eye discs show little signs of ER stress (G). The degree of xbp1-EGFP reporter activation by Rh-1G69D misexpression is similar between mekk1+ discs (H) and mekk1ur-36 −/− discs (I). (J–L) anti-ATF4 antibody labeling (red) is not affected by mekk1. A control disc (J). ATF4 is induced in Rh-1G69D expressing discs (K), and is not affected in a mekk1 −/− background (L). (M) mekk1 mutants are more resistant to Tunicamycin (Tm) feeding. 4–5 days old male flies (20 –25 flies in each vial) were allowed to feed for 7 days with standard cornmeal medium supplemented with 5 ug/ml Tm. The percentage indicates the number of flies survived from feeding with Tm (n = 3, p = 0.0062). The scale bar in (D) represents 100 μm for all panels. Error bars show ± SEM. Genotypes: gmr-Gal4/UAS-Rh-1G69D;+/+ (B, E, K), gmr-Gal4/UAS-Rh-1G69D;mekk1ur-36/ mekk1ur-36 (C, F, L), y, w (D), gmr-Gal4 /UAS-xbp1-EGFP;+/+ (G), gmr-Gal4, UAS-Rh-1G69D/UAS-xbp1-EGFP;+/+ (H), gmr-Gal4, UAS-Rh-1G69D/UAS-xbp1-EGFP;mekk1ur-36/mekk1ur-36 (I), gmr-Gal4/+ (J).

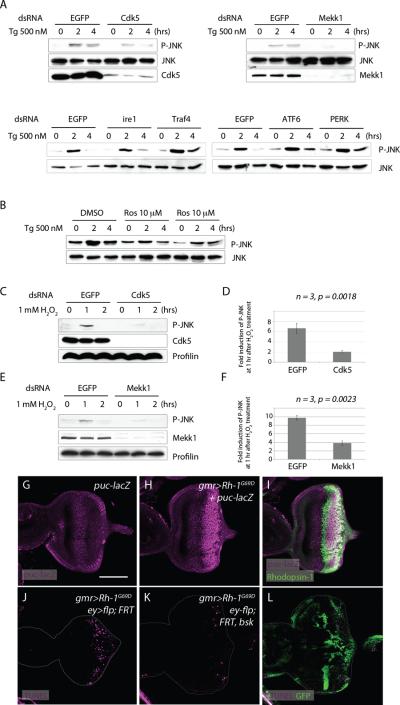

As previous studies have placed mekk1 genetically upstream of JNK 30, we examined the relationship between JNK, Mekk1 and Cdk5. For this, we exposed Drosophila S2 cells to thapsigargin (Tg), a SERCA inhibitor that is widely used to cause ER stress in cells32. Phospho-JNK appeared after 2 hours of Tg treatment (Figure 3A), and this induction of JNK phosphorylation was suppressed upon knockdown of cdk5 or mekk1 (Figure 3A), or when cells were treated with the Cdk5 inhibitor, roscovitine (Figure 3B). On the other hand, knockdown of other known mediators of the UPR, such as ire1, traf4, perk and atf6 had no discernible effects on JNK phosphorylation (Figure 3A). Among other stress conditions tested, H2O2 treatment generated a similar outcome (Figure 3C–F). H2O2's ability to induce JNK phosphorylation was significantly reduced in S2 cells pretreated with dsRNA targeting cdk5 or mekk1. While H2O2 treatment resulted in a more than six fold increase in phospho-JNK levels in control cells, cdk5 knocked down cells had on average only a two fold increase in phospho-JNK induction (Figure 3D)(n=3, p=0.018). Likewise, mekk1 knockdown reduced the extent of phospho-JNK induction in a statistically significant manner (Figure 3F)(n=3, p=0.0023).

Figure 3. Mekk1 and Cdk5 mediate JNK signaling activation in response to stress.

(A) Thapsigargin (Tg) treatment induces JNK phosphorylation dependent on cdk5 and mekk1. Cells pre-treated with dsRNA against EGFP (negative control) show anti-phospho JNK blots after 2 hours of Tg treatment. Pre-treatment of dsRNAs against cdk5 or mekk1 reduces JNK phosphorylation, while dsRNAs against ire1, traf4, atf6 and perk do not have obvious effects. (B) The role of cdk5 was further assessed by pre-treating cells with the Cdk5 inhibitor, Roscovitine (Lanes 4–9). Control cells were pre-treated with DMSO (Lanes 1–3). (C–F) cdk5 and mekk1 mediates JNK phosphorylation in response to H2O2 treatment. (C) H2O2 induced JNK phosphorylation analyzed in cells pretreated with dsRNAs either against EGFP (Lanes 1–3) or cdk5 dsRNA (Lanes 4–6). Anti-Cdk5 blot (middle panel) shows the degree of Cdk5 knockdown by RNAi. (D) Quantification of anti-phospho JNK bands after 1 hour of H2O2 treatment, with either a control dsRNA against EGFP or against cdk5, shows a statistically significant change (n=3, p=0.0018). (E) H2O2 induced JNK phosphorylation in cells pre-treated with dsRNAs against either EGFP (lanes 1–3) or mekk1 (4–6). Anti-Mekk1 blot (middle panel) shows the degree of Mekk1 knockdown by RNAi. (F) Quantification of phospho JNK bands after 1 hour of H2O2, from cells pretreated with dsRNA against either EGFP or mekk1, shows a statistically significant difference (n=3, p=0.0023). (G–I) Rh-1G69D expression (green) activates JNK signaling in eye imaginal discs, as evidenced by the JNK reporter puc-lacZ (magenta) (H, I). (H) shows the anti-betaGal single channel of (I). (G) is a negative control without Rh-1G69D expression. (J–L) The requirement of bsk (Drosophila JNK) in Rh-1G69D-induced apoptosis. A control bsk+ disc expressing Rh-1G69D shows many TUNEL positive cells (magenta) (J), which is suppressed in discs with bsk −/− mosaic clones (K, L). bsk −/− clones are marked by the absence of GFP (green). The scale bar in (G) represents 100 μm. Genotypes: gmr-Gal4/+; pucE69/+ (G), gmr-Gal4,UAS-Rh-1G69D/+; pucE69/+ (H, I), gmr-Gal4, ey-flp/+;UAS-Rh-1G69D/ ubi-GFP, FRT40;+/+ (J), gmr-Gal4, ey-flp/+;bsk170B, FRT40, UAS-Rh-1G69D/ ubi-GFP, FRT40;+/+ (K, L).

Consistent with the results from S2 cells, Rh-1G69D misexpressing imaginal discs showed signs of JNK signaling activation, as assessed through the puc-lacZ reporter (Figure 3G–I). To test if JNK is required for ER-stress-induced apoptosis, we generated loss-of-function mosaic clones of the Drosophila JNK gene, basket. When Rh-1G69D was overexpressed in imaginal discs harboring basket −/− clones, the number of apoptotic cells as assessed through TUNEL labeling was significantly reduced, with the remaining apoptotic cells primarily within the basket+ mosaic clones (Figure 3J–L). We noticed that many apoptotic cells were found at the clonal boundaries. This property was also observed in mutant mosaic clones of dronc (Supplementary Figure S4), which is an essential initiator caspase for apoptosis33,34. These observations support the idea that ER-stress activates Cdk5/Mekk1-mediated JNK signaling to cause caspase-dependent apoptosis.

Using a phosphorylation site prediction program (http://scansite.mit.edu), we detected two consensus Cdk5 phosphorylation sites within the Drosophila melanogaster Mekk1 protein sequence, T157 and S1127. The putative phosphorylation sites within Mekk1were conserved in other Drosophila species, suggestive of its functional significance (Figure 4A). To test if Mekk1 is in fact phosphorylated by Cdk5, we generated antibodies directed against the putative phospho-residues (see Methods). Using one of these, an antibody directed towards the phosphorylated S1127 residue, we were able to detect Mekk1 phosphorylation by Cdk5 in vitro (Figure 4B). We also detected phosphorylation of this residue in cultured HEK293T cells transfected with flag-tagged Mekk1 (Figure 4C). Notably, the intensity of the phospho-S1127 band increased significantly in cells when Cdk5 was co-transfected, and further enhanced when those cells were stressed with H2O2 (Figure 4C lanes 3, 4). On average, the degree of Mekk1 phosphorylation increased more than three fold after H2O2 treatment (Figure 4C, n=3, p=0.0003). We confirmed that this band corresponds to phospho-S1127, as the signal did not appear when the Mekk1 S1127 residue was mutated (Figure 4D lane 5, 6). Furthermore, the anti-phospho-Mekk1 failed to detect any band when the immunoprecipitate was treated with the lambda phosphatase (Figure 4E). Moreover, the two proteins physically interacted, as evidenced by co-immunoprecipitation assays. Interestingly, the interaction was enhanced when the cells were pre-treated with H2O2 (Figure 4F). Taken together, these genetic and biochemical experiments support the idea that Cdk5 and Mekk1 form a pathway to activate JNK signaling in response to ER-stress.

Figure 4. Cdk5 phosphorylates Mekk1.

(A) Conserved Cdk5 consensus phosphorylation sites within Mekk1 of various Drosophila species. (B) Cdk5 phosphorylates Mekk1WT on the S1127 residue in vitro. Immunopurified Mekk1 was incubated with recombinant Cdk5 and p35, and subsequently probed with an antibody against phospho S1127 residue of Mekk1 (anti-p-Mekk1S1127). Anti-Flag blots show total Flag-tagged Mekk1 levels (lower panel). (C) Phosphorylation at Mekk1 in transfected cells. The Flag-tagged Mekk1 was immunoprecipitated and probed with the anti-p-Mekk1S1127 antibody. The average intensities of phospho Mekk1 bands are shown in a graph underneath the blot. Only Cdk5 tranfected cells show a statistically significant increase in Mekk1 phosphorylation after H2O2 treatment (n=3, p=0.0003). (D) Validation of the Mekk1 phosphorylation sites. HEK 293T cells were transfected with Cdk5, together with the indicated expression plasmids marked above the blot. Phospho-Mekk1 bands do not appear when a mutant Mekk1 plasmid lacking the putative phosphorylation sites are transfected (lanes 5, 6). Anti-Flag blots show Flag-tagged Mekk1 levels (middle blot), while anti-HA bands show transfected Cdk5 levels (lower blot). (E) Mekk1 phosphorylation bands disappear after phosphatase treatment (lane 4).

Immunoprecipitated complex were either untreated or treated with λ-phosphatase (PP) prior to western blot analysis. (F) Coimmunoprecipitation of Cdk5 and Mekk1. 293T cells were transfected with Flag-tagged Mekk1WT, together HA-tagged Cdk5WT. The protein complexes were immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag antibody and analyzed by western blotting using anti-HA antibody. The interaction between Cdk5WT and Mekk1WT was enhanced when cells were pretreated with H2O2 (lanes 2).

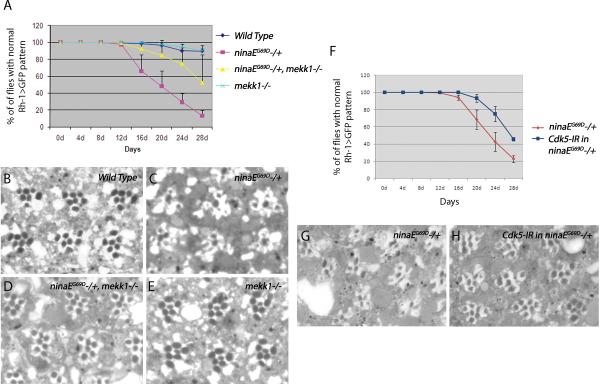

To test if this pro-apoptotic signaling pathway is also relevant to an age-dependent disease process, we turned to the Drosophila model for ADRP, where an endogenous mutant allele of the Rh-1 gene, ninaEG69D, causes late-onset retinal degeneration phenotype associated with ER stress9, 10. To track the course of retinal degeneration in live flies, we used the ninaEG69D/+ condition combined with a Rh-1>GFP reporter 35. Nearly 90% of ninaEG69D/+ flies lost the regular ommatidial array by day 28 after eclosion, indicative of age-related retinal degeneration. Those ninaEG69D/+ flies in a mekk1ur-36 −/− background showed a delayed course of retinal degeneration, with only about half of the examined flies with disrupted Rh-1>GFP patterns (Figure 5A). Knockdown of cdk5 in the photoreceptors also delayed the course of retinal degeneration to a similar degree (Figure 5F). This result was further validated through tangential sections of 20 day old fly retina. Wild type flies showed regular ommatidial arrays (Figure 5B), while the ninaEG69D/+ retina by this age showed disorganized ommatidia (Figure 5C, G). This phenotype was largely rescued in the backgrounds of mekk1ur-36 −/− (Figure 5D), or in cdk5 knockdown conditions (Figure 5H).

Figure 5. The course of late onset retinal degeneration of ninaEG69D/+ flies is delayed upon knockdown of Cdk5, or in the mekk1ur-36−/− background.

(A) Quantification of the degeneration process using the Rh1>GFP fluorescence. For each genotype, the percentage indicates the number of flies with intact ommatidial arrays as evidenced by Rh>GFP pattern, from an average of eight independent crosses. Loss of mekk1 function delays the course of retinal degeneration of ninaEG69D/+ flies (n = 8, p = 0.0062). (B–E) Representative images of 20 day old adult eye tangential sections. Genotypes are as indicated in the panels. Wild type flies show clusters of seven rhabdomeres (stained as black circles) in a trapezoidal pattern within each ommatidia. While this pattern is disrupted in the ninaEG69D/+ retina, this degenerative phenotype is suppressed in ninaEG69D/+ with a mekk1ur-36 −/− background. (F) The knockdown of Cdk5 suppresses late onset retinal degeneration of ninaEG69D/+ flies (n = 5, p = 0.0004). (G, H) Representative images of 20 day old adult retina downregulating Cdk5 in the ninaEG69D/+ background.

These results indicate that the pro-apoptotic ER-stress response mediated by mekk1 and cdk5 are relevant to understanding age-related photoreceptor degeneration in ADRP. Moreover, our results suggest that Cdk5/Mekk1/JNK forms a pathway that is independent of those UPR branches. While it is unclear what lies upstream of Cdk5 in our experimental system, we note that among the previously characterized Cdk5 activating signals include ROS, calpains and Cam kinase II23, 25, 36, 37, which have been also associated with ER-stress 16, 38. Thus it is possible to envision a model where chronic proteotoxicity in the ER sends Cdk5 activating signals to the cytoplasm, perhaps via ROS or Ca2+ mediated signaling. Once Cdk5 is activated, it may send pro-apoptotic signals to the nucleus through the Mekk1/JNK pathway (Supplementary Figure S5).

Many terminally differentiated cells without regenerative potential are known to acquire resistance to apoptosis during differentiation. In Drosophila, such apoptotic resistance can be attributed to the epigenetic silencing of major pro-apoptotic gene loci during development 39. A recent study showed that one of the consequences of stress-induced Mekk1-signaling is to induce the expression of genes that are normally silenced through epigenetic mechanisms31. Based on these observations, we think it is possible that terminally differentiated photoreceptors may have their pro-apoptotic loci in heterochromatin-like states, and stress-induced Cdk5/Mekk1 pathway contributes to neurodegeneration by restoring those loci to an open chromatin state, an idea that needs to be tested through future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ed Giniger, Kunihiro Matsumoto, Masayuki Miura, the VDRC and Bloomington stock centers for reagents, Edith Robbins, Michele Pagano and Ester Zito for technical advice, and David Ron for discussions and critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01EY020866. H.D.R. is an Ellison Medical Foundation New Scholar.

Footnotes

Author Contributions M. K and H.D.R. designed the experiments. J.C. carried out the EP screen. All other experiments were performed by M. K. H.D.R. wrote the paper and all authors read and edited the manuscript.

Reference

- 1.Dryja T, McGee TL, Reichel E, Hahn LB, Cowley GS, Yandell DW, Sandberg MA, Berson EL. A point mutation of the rhodopsin gene in one form of retinitis pigmentosa. Nature. 1990;343:364–366. doi: 10.1038/343364a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung CH, Davenport CM, Hennessey JC, Maumenee IH, Jacobson SG, Heckenlively JR, Nowakowski R, Fishman G, Gouras P, Nathans J. Rhdopsin mutations in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:6481–6485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryoo HD, Domingos PM, Kang MJ, Steller H. Unfolded protein response in a Drosophila model for retinal degeneration. Embo J. 2007;26:242–252. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to hemeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang M-J, Ryoo HD. Suppression of retinal degeneration in Drosophila by stimulation of ER-Associated Degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:17043–17048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905566106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell. 2000;101:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harding HP, et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell. 2003;11:619–633. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto K, Sato T, Matsui T, Sato M, Okada T, Yoshida H, Harada A, Mori K. Transcriptional induction of mammalian ER quality control proteins is mediated by single, or combined action of ATF6alpha and xbp1. Dev. Cell. 2007;13:365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colley NJ, Cassill JA, Baker EK, Zuker CS. Defective intracellular transport is the molecular basis of rhodopsin-dependent dominant retinal degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:3070–3074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurada P, O'Tousa JE. Retinal degeneration caused by dominant rhodopsin mutations in Drosophila. Neuron. 1995;14:571–579. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewes RS, Schaefer AM, Taghert PH. The cryptocephal gene (ATF4) encodes multiple basic-leucine zipper proteins controlling molting and metamorphosis in Drosophila. Genetics. 2000;155:1711–1723. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Wek R, Schapira M, Ron D. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marciniak SJ, et al. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3066–3077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li G, Scull C, Ozcan L, Tabas I. NADPH oxidase links endoplasmic reticulum stress, oxidative stress and PKR activation to induce apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2010;191:1113–1125. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song B, Scheuner D, Ron D, Pennathur S, Kaufman RJ. Chop deletion reduces oxidative stress, improves beta cell function, and promotes cell survival in multiple mouse models of diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3378–3389. doi: 10.1172/JCI34587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timmins JM, Ozcan L, Seimon TA, Malagelada C, Backs J, Backs T, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Anderson ME, Tabas I. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II links ER stress with Fas and mitochondrial apoptosis pathways. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:2925–2941. doi: 10.1172/JCI38857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tu BP, Weissman JS. Oxidative protein folding in eukaryotes: mechanisms and consequences. J. Cell Biol. 2004;164:341–346. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison DK, Murakami MS, Cleghon V. Protein kinases and phosphatases in the Drosophila genome. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:57–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.2.f57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connell-Crowley L, Le Gall M, Giniger E. The cyclin-dependent kinase cdk5 controls multiple aspects of axon patterning in vivo. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:599–602. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai LH, Delalle I, Caviness VS, Chae T, Harlow E. p35 is a neural-specific regulatory subunit of cyclin-dependent kinase 5. Nature. 1994;371:419–423. doi: 10.1038/371419a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi JH, Banks AS, Estall JL, Kajimura S, Bostrom P, Laznik D, Ruas JL, Chalmers MJ, Kamenecka TM, Bluher M, Griffin PR, Spiegelman BM. Anti-diabetic drugs inhibit obesity-linked phosphorylation of PPARgamma by Cdk5. Nature. 2010;466:451–456. doi: 10.1038/nature09291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei FY, Nagashima K, Ohshima T, Saheki Y, Lu YF, Matsushita M, Yamada Y, Mikoshiba K, Seino Y, Matsui H, Tomizawa K. Cdk5-dependent regulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Nat. Med. 2005;11:1104–1108. doi: 10.1038/nm1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saito T, Konno T, Hosokawa T, Asada A, Ishiguro K, Hisanaga S. p25/cyclin-dependent kinase 5 promotes the progression of cell death in nucleus of endoplasmic reticulum-stressed neurons. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:133–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrick GN, Zukerberg L, Nikolic M, de la Monte S, Dikkes P, Tsai LH. Conversion of p35 to p25 deregulates Cdk5 activity and promotes neurodegeneration. Nature. 1999;402:615–622. doi: 10.1038/45159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qu D, Rashidian J, Mount MP, Aleyasin H, Persanejad M, Lira A, Haque E, Zhang Y, Callaghan S, Daigle M, Rousseaux MW, Slack RS, Albert PR, Vincent I, Woulfe JM, Park DS. Role of Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of Prx2 in MPTP toxicity and Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2007;55:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elbein AD. Inhibitors of glycoprotein synthesis. Methods Enzymol. 1983;98:135–154. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)98144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connell-Crowley L, Vo D, Luke L, Giniger E. Drosophila lacking the Cdk5 activator, p35, display defective axon guidance, age-dependent behavioral deficits and reduced lifespan. Mech. Dev. 2007;124:341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rorth P. A modular misexpression screen in Drosophila detecting tissue-specific phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:12418–12422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hay BA, Wasserman DA, Rubin GM. Drosophila homologs of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis proteins function to block cell death. Cell. 1995;83:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue H, Tateno M, Fujimura-Kamada K, Takaesu G, Adachi-Yamada T, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Irie K, Nishida Y, Matsumoto K. A Drosophila MAPKKK, D-Mekk1, mediates stress response through activation of p38 MAPK. EMBO J. 2001;20:5421–5430. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seong KH, Li D, Shimizu H, Nakamura R, Ishii S. Inheritance of stress-induced, ATF-2-dependent epigenetic change. Cell. 2011;145:1049–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lytton J, Westlin M, Hanley MR. Thapsigargin inhibits the sarcoplasmic or endoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase family of calcium pumps. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:17067–17071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chew SK, Akdemir F, Chen P, Lu WJ, Mills K, Daish T, Kumar S, Rodriguez A, Abrams JM. The apical caspase dronc governs programmed and unprogrammed cell death in Drosophila. Dev. Cell. 2004;7:897–907. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu D, Li Y, Arcaro M, Lackey M, Bergmann A. The CARD-carrying caspase Dronc is essential for most, but not all, developmental cell death in Drosophila. Development. 2005;132:2125–2134. doi: 10.1242/dev.01790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pichaud F, Desplan C. A new visualization approach for identifying mutations that affect differentiation and organization of the Drosophila ommatidia. Development. 2001;128:815–826. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.6.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee MS, Kwon YT, Li M, Peng J, Friedlander RM, Tsai LH. Neurotoxicity induces cleavage of p35 to p25 by calpain. Nature. 2000;405:360–364. doi: 10.1038/35012636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dhavan R, Greer PL, Morabit MA, Orlando LR, Tsai LH. The cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activators p35 and p39 interact with the alpha-subunit of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and alpha-actinin-1 in a calcium-dependent manner. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:7879–7891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-07879.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakagawa T, Yuan J. Cross-talk between two cysteine protease families. Activation of caspase-12 by calpain in apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:887–894. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Lin N, Carroll PM, Chan G, Guan B, Xiao H, Yao B, Wu SS, Zhou L. Epigenetic blocking of an enhancer region controls irradiation-induced proapoptotic gene expression in Drosophila embryos. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:481–493. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.