Abstract

The goals of this study are to explore whether health condition is an antecedent extraneous factor for the relationship between health care system distrust and self-rated health among the elderly, and to investigate if the associations among these variables are place-specific. We used logistic geographically weighted regression to analyze data on an elderly sample residents in the Philadelphia metropolitan area. We found that the health conditions of the elderly account for the association between high distrust and poor/fair self-rated health and that the distrust/self-rated health relationship varied spatially. This finding suggests that a place-centered perspective can inform distrust/self-rated health research.

Keywords: self-rated health, health care system distrust, elderly, geographically weighted regression, Philadelphia metropolitan area

1. Introduction

There is a growing interest in the relation between health care system distrust (hereafter distrust) and seeking medical care, maintaining appropriate health care, and adhering to medical advice (Mollborn et al., 2005; Thom et al., 2004; Whetten et al., 2006). While the level of trust with health providers has received much attention in the literature (Hall, 2006), recent attention has focused on associations between distrust and several health outcomes; in particular self-rated health (Yang et al., 2011). Self-rated health is an overall assessment of health perception and is a known predictor of long-term health outcomes even after controlling for other factors (Jylha, 2009; Lyyra et al., 2009). Importantly, recent studies not only distinguished actual health from self-rated health, but also utilized the former to predict the latter (Damian et al., 2008; Molarius and Janson, 2002; Sargent-Cox et al., 2008). While the determinants of self-rated health have been extensively studied (Jylha, 2009), the question of whether self-rated health is associated with distrust among the elderly, the population that interacts with the health care system more than any other groups, remains unclear

It is important to define distrust (Cunningham et al., 2007; Hall et al., 2001). Distrust is not only the lack of trust but it can also incorporate a negative belief that trustees will act against an individual's best interest (Hall et al., 2001). That is, distrust implies a stronger level of resistance than low trust or the lack of trust. In some previous studies, distrust in personal health providers (i.e., specific doctors or facilities) was the focus. Less attention, however, has been paid to the distrust in the health care system as a whole (Hall, 2006; Rose et al., 2004).

A few studies have examined the association between distrust and self-rated health. A US and a Swedish study found poor self-rated health was associated with low trust of the health care system (Armstrong et al., 2006; Mohseni and Lindstrom, 2007) and their findings were robust after controlling for access to health care, care-seeking behavior, trust in primary physicians, and other socioeconomic variables. A more recent study employed multilevel analysis and found that distrust and neighborhood social environment were determinants of poor/fair self-rated health (Yang et al., 2011).

Theoretically, distrust should be associated with the frequency as well as the cost of interaction between individuals and providers, and especially for those who are medically vulnerable, such as the elderly. People with poor health, relative to healthier counterparts, may experience frustration with the health care system, leading to high levels of distrust (Corbie-Smith and Ford, 2006). In turn, high levels of distrust may complicate the delivery of health care services, including the dissemination and adoption of useful information on treatment and the maintenance or continuity of treatment (Hardin, 2001; Lewicki and Bunker, 1996). High distrust, therefore, should be associated with poor self-rated health (Armstrong et al., 2006).

However, the theoretical relationship between self-rated health and distrust may not hold among the elderly. This is because health conditions may be the dominant determinant of self-rated health in this population. In this paper, we hypothesize that health condition is a shared determinant of self-rated health and distrust and that once the individual health condition is considered, distrust will not be associated with self-rated health. We elaborated our position as follows. On the one hand, the elderly tend to have higher health care demands, resulting in part from more frequent and diverse interactions, than other groups and this group may experience frustration or satisfaction when health care providers fail to meet or exceed their needs for quality services (Armstrong et al., 2006; Corbie-Smith and Ford, 2006). The health conditions of the elderly, thus, become a determinant of distrust. On the other hand, studies have concluded that individuals with chronic disease report worse self-rated health than healthy counterparts (Damian et al., 2008; Goldstein et al., 1984; Molarius and Janson, 2002). Also, depression symptoms and impaired instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) have been found to be negatively associated with self-rated health among the elderly (Damian et al., 2008; Han, 2002; Lee and Shinkai, 2003). Thus, it can be that health conditions are a predictor of self-rated health after controlling for socioeconomic and demographic features (Goldman et al., 2004; Sargent-Cox et al., 2008) and, as such, health conditions may be an antecedent extraneous factor for both distrust and self-rated health. We note that this type of relationship ought to be observed in an elderly sample.

The first goal of this study is to test the hypothesis that, controlling for health conditions, there is no significant association between self-rated health and distrust in general. In addition, this study explores the local – i.e., place specific – association between distrust and self-rated health. Yang and colleagues (2011) suggested that the associations between distrust and self-rated health vary across neighborhoods and that the distrust/self-rated health relationship may be spatially non-stationary (though this was not tested). Thus, the second goal of this study is to further investigate the locally varying pattern of the distrust/self-rated health relationship in an elderly sample living in the Philadelphia metropolitan area (a five-county area in southeastern Pennsylvania).

The core county, Philadelphia County, includes over 1.5 million residents of which almost 60 percent are minority (US Census Bureau, 2010). The remaining metropolitan counties – Bucks, Chester, Delaware and Montgomery – contain a total of approximately 2.3 million residents. Outside of the core county, the proportion minority in Delaware County is almost 30 percent and in the other three counties approximately 15 percent. The Philadelphia metropolitan area is the fifth largest metropolitan area in the US and because of the within and between county heterogeneity in socioeconomic and race/ethnic structure, it is an ideal study site for studying the relationship between distrust and self-rated health. Also our study is unique in that prior studies of distrust have largely ignored place and they have tended to focus on groups resident in central city locations and not on a diverse metropolitan area. While parts of our study area may appear ‘rural,’ our study area is decidedly metropolitan; in Bucks County the population exceeds 410,000 and the population density is 435 persons per square mile (US Census Bureau, 2010).

Place-centered perspectives have drawn increasing attention as they can provide new insight in health research (Goovaerts, 2008; Kearns and Gesler, 1998; Young and Gotway, 2010). However, all previous research on distrust/self-rated health assumes the relationship is stationary across space. While multilevel modeling is the more traditional method used to incorporate both individual and neighborhood level data, this approach does not explicitly take spatial structure into account and the estimates of parameters are subject to predefined neighborhood units (Brunsdon et al., 1998). Instead, we adopt a single-level exploratory technique, geographically weighted regression (GWR) (Fotheringham et al., 2002). As such our study is among the first to address spatial non-stationarity in distrust among the elderly.

2. Design and Methods

2.1. Data

We use the elderly supplement file (age 60+) of the Philadelphia Health Management Corporation's (PHMC) 2008 Southeastern Pennsylvania Household Health Survey. The PHMC data used here are all drawn from a five-county area (the Philadelphia metropolitan area). The biannual PHMC survey collects information on a range of health behaviors, health status, and health care, as well as demographic and socioeconomic variables (PHMC, 2008). Using a stratified sampling frame and random-digit dialing methodology, the PHMC survey is representative of the population within the survey area, and has been found to closely resemble demographic profiles of other surveys such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (PHMC, 2008). Importantly for this study, the PHMC survey oversampled residents over age 60. The questions in the oversampling focus on respondent's physical functional status and access to health care.

2.2. Spatial Randomization

To explore the local association between distrust and self-rated health with individual-level data requires detailed residential information or a geocode. However, for confidentiality reasons, this type of health data is rarely available, and typically the lowest level of geographic identification in individual-level data is a respondent's residential area such as census tracts (i.e., the geocode is for a zone). While insights on some major public health concerns can arise from analyzing aggregated respondent health information, the use of spatially aggregated data may be of little benefit (Curtis et al., 2006; Fefferman et al., 2005) especially if scale and aggregation issues – the modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP) – influence results and undermine validity (Openshaw, 1984). Studies have attempted to solve the MAUP (Besag and Newell, 1991; Gatrell et al., 1996) but perhaps the only real solution is to work from point-based individual-level data (Weeks, 2004). With a zonal geocode, we lack individual point locations. In such a case, it is common practice to assume every observation is located at the zone centroid, but doing so would minimize spatial variation; crucial in an analysis where distances between observations is expected to be important (i.e., GWR). To address this, we use spatial randomization to randomly place each respondent within their residential zone and this allows us to fit distance-based kernel density function.

The census tract where the respondents live is the smallest geographic unit in the PHMC data. Thus, we prepared a tract-level boundary file covering the entire study in a geographic information system (GIS) and then randomly assigned coordinates to each individual record, checking to ensure that the each generated point was contained within the boundary of the individual's residential tract. This step was repeated until all survey respondents were placed randomly within their residential census tracts.

2.3. Measures

The dependent variable is self-rated health. PHMC respondents were asked to assess their overall health as excellent, good, fair, or poor. We dichotomized responses into excellent/good (reference group) and fair/poor. This binary self-rated health measure is widely used, facilitating comparison with earlier studies (Mohseni and Lindstrom, 2007; Molarius and Janson, 2002; Subramanian et al., 2002).

Our independent variables capture four domains of interest. First, distrust in the PHMC was a 9-item scale developed and tested for reliability by Shea et al (Shea et al., 2008). These nine items can be further grouped into two sub-scales to capture different dimensions of distrust. Using factor analysis with varimax rotation, we generated two factor scores based on the regression method: values distrust and competence distrust (eigenvalues were 3.30 and 1.12 respectively and the variance explained, 53%). The regression method accounted for both the factor correlations and factor loadings in calculating factor scores. Since these two scores measured the same concept (Shea et al., 2008), their average was used in the analysis as a single indicator of individual distrust. Combining these two dimensions yielded a measure of overall health care system distrust which has been used elsewhere (Armstrong et al., 2008). About 10 percent of the distrust scale items were missing. We excluded the respondents who did not answer any of the nine distrust questions, and imputed missing values based on an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm for continuous variables (Hill, 1997). Imputed scores for distrust were rounded to the nearest whole number to reflect the coding system designed in the original scale. The EM missing data imputation has been used and validated (Schafer and Graham, 2002).

The second domain includes demographic and socioeconomic predictors. Gender was a dummy variable where males served as the reference group. Age was reported by the respondents and treated as a continuous variable in the analysis. Race was divided into White, Black, and Others (reference group). Marital status was classified as single, married, widowed, and divorced; where single was treated as the reference group and three dummy variables were created. Poverty status was based on the 2008 federal poverty guideline with those whose income was below the poverty line classified as poor (reference group). Among the elderly, health and employment are correlated (about 65 percent were retired and 5 percent unable to work). We included a dummy variable for employment status (employed serving as the reference group). Educational attainment was categorized into five levels (four dummy variables): did not graduate high school (reference group), high school diploma, some college, an associate or bachelor degree, and post college diploma.

We also included several variables related to the third domain of interest, health care resources. The elderly were asked if they have regular sources of care; those answering “no” served as the reference group. Health insurance status was captured by two dummy variables based on no health insurance (reference group), government insurance, and private insurance.

The final domain of interest relates to an individual's health condition. The elderly were asked if they had any health problems that required medical treatment or hospitalization on a regular basis; those answering “yes” serve as the reference group. A dummy variable was created based on a response regarding high blood cholesterol; the reference group was those told by a doctor or other health professional that s/he had high blood cholesterol. The 2008 PHMC used the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) to measure depression among the elderly (Radloff, 1977). The reliability and validity of CES-D have been compared with other depression scales and reported elsewhere (Irwin et al., 1999; Lyness et al., 1997). A variable, depression, was created based on the respondents’ responses to these questions. Depression was treated as a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 10 with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression. The final measure of individual health condition was the impaired instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). Seven activities of daily life are identified: using the telephone, going places out of walking distance, shopping, preparing meals, doing the housework, taking medicine, and handling money. The elderly were asked whether they can complete each activity without any help. We summed up the activities participant needs help to complete, and the total number of activities was used as the IADL variable, ranging from 0 (all activities can be done without help) to 7 (help needed for all activities).

All variables above are widely used in self-rated health research and our approach adopted the most common classifications used in the literature. For example, similar, if not identical, treatment of age, race, marital status, education, health insurance, chronic diseases, high cholesterol, and IADL, can be found (Cagney et al., 2005; Damian et al., 2008; Finch and Vega, 2003; Goldman et al., 2004; Subramanian et al., 2002).

We also pay attention to the multicollinearity among the independent variables. While conditional index can be used to detect multicollinearity, a recent criticism suggests misleading conclusions can be drawn when the variations among independent variables are small (Lazaridis, 2007). We use the variance inflation factor (VIF), a more precise indicator, to detect whether multicollinearity is a potential problem among the independent variables (Mansfield and Helms, 1982). The square root of the VIF of an independent variable indicates how much larger the standard error of this independent variable is in contrast to what it would be if this variable were uncorrelated with the other covariates in a model. In general, if a VIF is greater than 10, multicollinearity is a concern (Kutner et al., 2004).

2.4. Analytic Strategy

Our dependent variable (self-rated health) is binary and thus a logistic GWR approach was employed (Fotheringham et al., 2002). The model can be expressed as:

where yi is self-rated health for each individual i, (ui,vi) denotes the coordinates of individual i, xni represents a set of explanatory variables (n=1,...,k) for individual i, and βni represents the estimated effect of variable n for individual i.

Modeling was implemented with the iteratively reweighted least squares method in GWR 3.0 (Fotheringham et al., 2003). The coefficient of an independent variable in the logistic GWR indicates the change in the log odds of the response given a unit change in that variable. Taking the exponentiation of the coefficient yields the odds ratio corresponding to a unit change in the variable. GWR 3.0 estimates both global and local GWR logistic models. Neither the Monte Carlo and Leung tests for non-stationarity are implemented in logistic GWR (Fotheringham et al., 2003; Leung et al., 2000). Summarizing local estimates and mapping the local estimates and p-values is the appropriate method to demonstrate non-stationarity (Fotheringham et al., 2002). Below we report the global estimates, summarize the local estimates, and visualize the local association between distrust and self-rated health.

The kernel is the bi-square weighting function and the bandwidth (the number of nearest neighbors to be included in the bi-square kernel) is determined with an adaptive method. That is, the bandwidth is selected based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), where the bandwidth with the lowest AIC is used in analysis. AIC was first developed by Akaike (1974) to take the number of parameters estimated in a model into consideration and is a diagnostic for model comparison; models with low AICs are preferred. While the fixed bandwidth method is available, it may generate large variances and insufficient modeling power when data are spatially sparse and overlook subtle local variations when data are geographically dense. By contrast, the adaptive method provides optimal bandwidths based on the density of spatial points across areas (Fotheringham et al., 2001). In the Philadelphia metropolitan area context, this is important as population density varies from over 11,000 (Philadelphia County) to 435 (Bucks County) people per square mile.

With the bi-square kernel and bandwidth, the logistic GWR uses a distance-based weighting scheme to assign weights. Specifically, the kernel density function is centered on a data point, and the distances between this focal point and other observations within the bandwidth are calculated. In principle, the magnitude of weight decays as distance increases. Note GWR is relatively insensitive to the choice of kernel functions, such as Gaussian and bi-square (Fotheringham et al., 2002).

Both non-spatial and spatial exploratory data analyses tools were used before our analysis based on logistic GWR. Our strategy was to first implement a model including only distrust, demonstrating its relationship with self-rated health. The second model added socioeconomic, demographic, and health care resources covariates. This model was expected to duplicate findings in the literature, showing that high distrust is related to poor/fair self-rated health even after controlling for these covariates. To determine if health condition is an antecedent factor that can explain the association found in the second model, the variables related to health conditions are then added in the third model. If the inclusion of these covariates makes the relationship between self-rated health and distrust disappear then we have evidence health condition may be an antecedent factor. All three models above were re-run using logistic GWR. This strategy helps us to understand whether the local modeling approach improves the overall model fit for our data, and whether the association between self-rated health and distrust among the elderly varies across space within the study area.

3. Results

3.1. Non-spatial descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the non-spatial descriptive statistics of each variable in our analysis. For those dummy variables, their mean values can be interpreted as the proportions of those coded as the reference group. Across the study area, over 70 percent of elderly assessed their health as excellent/good. Variation across the five counties was substantial. For instance, the percentage of reporting poor/fair health in Philadelphia County was twice that of Chester County. Interestingly, the elderly in Philadelphia County reported the highest distrust score, with their counterparts in Chester the lowest. This finding, in part, suggests that the association between distrust and self-rated health differs across space.

Table 1.

Non-spatial descriptive statistics of the variables in this study (by county)1

| Overall2 | Bucks2 | Chester2 | Delaware2 | Montgomery2 | Philadelphia2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Respondents | 3,231 | 353 | 409 | 452 | 690 | 1,327 |

| Dependent Variable | ||||||

| Self-rated Health | ||||||

| Poor/Fair | 0.286(0.452) | 0.233(0.423) | 0.178(0.383) | 0.272(0.446) | 0.242(0.429) | 0.360(0.480) |

| Excellent/Good | 0.714(0.452) | 0.767(0.423) | 0.822(0.383) | 0.728(0.446) | 0.758(0.429) | 0.640(0.480) |

| Independent Variables | ||||||

| Health Care System Distrust | 0.000(0.707) | -0.072(0.683) | -0.153(0.743) | -0.003(0.694) | -0.079(0.671) | 0.118(0.708) |

| Demographic Variables | ||||||

| Race (ref = others) | ||||||

| White (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.750(0.433) | 0.935(0.246) | 0.892(0.310) | 0.830(0.376) | 0.902(0.298) | 0.551(0.498) |

| Black (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.196(0.397) | 0.031(0.173) | 0.056(0.231) | 0.137(0.344) | 0.056(0.230) | 0.375(0.484) |

| Gender (1= males, 0 = females) | 0.327(0.469) | 0.317(0.466) | 0.347(0.477) | 0.303(0.460) | 0.360(0.480) | 0.315(0.465) |

| Age | 70.834(8.248) | 70.236(7.986) | 70.511(8.413) | 71.270(8.427) | 71.082(8.260) | 70.817(8.197) |

| Marital Status (ref = single) | ||||||

| Married (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.441(0.497) | 0.548(0.498) | 0.567(0.496) | 0.451(0.498) | 0.519(0.500) | 0.330(0.470) |

| Widowed (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.298(0.457) | 0.244(0.430) | 0.244(0.430) | 0.314(0.465) | 0.268(0.443) | 0.338(0.473) |

| Divorced (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.105(0.307) | 0.098(0.298) | 0.100(0.301) | 0.088(0.284) | 0.102(0.303) | 0.115(0.320) |

| Socioeconomic Variables | ||||||

| Poverty (1=poor, 0=non-poor) | 0.073(0.259) | 0.042(0.201) | 0.022(0.147) | 0.044(0.206) | 0.032(0.175) | 0.127(0.333) |

| Employment (1=employed, 0 = not employed) | 0.263(0.440) | 0.284(0.451) | 0.330(0.471) | 0.294(0.456) | 0.301(0.459) | 0.207(0.405) |

| Educational Attainment (ref = no high school) | ||||||

| High School Graduation (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.393(0.489) | 0.388(0.488) | 0.296(0.457) | 0.394(0.489) | 0.359(0.480) | 0.442(0.497) |

| Some College (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.179(0.384) | 0.205(0.404) | 0.169(0.375) | 0.190(0.393) | 0.177(0.382) | 0.173(0.379) |

| College (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.173(0.378) | 0.188(0.391) | 0.276(0.448) | 0.170(0.376) | 0.218(0.413) | 0.115(0.319) |

| Post-college (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.135(0.342) | 0.132(0.339) | 0.183(0.387) | 0.164(0.370) | 0.176(0.381) | 0.090(0.286) |

| Health Care Resources | ||||||

| Without Regular Source of Care | 0.054(0.226) | 0.039(0.195) | 0.054(0.226) | 0.044(0.206) | 0.042(0.200) | 0.068(0.251) |

| Insurance Status (ref=no insurance) | ||||||

| Governmental Insurances (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.778(0.397) | 0.718(0.372) | 0.691(0.317) | 0.768(0.384) | 0.722(0.362) | 0.854(0.423) |

| Other Private Insurances (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.205(0.448) | 0.277(0.457) | 0.296(0.477) | 0.219(0.456) | 0.266(0.448) | 0.121(0.431) |

| Health Conditions | ||||||

| Chronic Diseases (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.332(0.471) | 0.289(0.454) | 0.269(0.444) | 0.350(0.477) | 0.331(0.471) | 0.356(0.479) |

| High Blood Cholesterol (1= yes, 0 = no) | 0.452(0.498) | 0.419(0.494) | 0.445(0.498) | 0.409(0.492) | 0.474(0.500) | 0.465(0.499) |

| Depression Symptoms | 1.339(1.833) | 1.070(1.607) | 1.044(1.476) | 1.135(1.696) | 1.261(1.760) | 1.608(2.025) |

| IADL | 0.476(1.102) | 0.334(0.960) | 0.291(0.864) | 0.423(1.049) | 0.406(0.992) | 0.625(1.246) |

We reported the mean values of each variable in this table. Note that for categorical variables, the mean values represent the proportions of those coded 1. Multiplying the proportions by the total number of respondents yields the frequency.

Standard deviations are in the parentheses.

In PHMC, about two-thirds of the elderly were females and mean age was roughly 71. Seventy-five percent of respondents were white and 20 percent African American (reflecting the race/ethnic structure of the entire metropolitan area). The modal category for marital status was married, though 30 percent of the elderly were widowed and 11 percent divorced. The poverty rate was seven percent and a quarter was employed. Completing high school was the most common educational attainment level, with three out of ten residents earning at least an associate degree. Only 5 percent of participants lacked a regular source of care. Ten percent had private insurance and most of the remainder had governmental health insurance (i.e., Medicare or Medicaid). Regarding health conditions, more than 30 percent of the elderly reported having chronic diseases or high blood cholesterol levels, though the prevalence of depression symptoms (>2 depressive symptoms) and IADL (1 limitation) was relatively low.

3.2. Spatial descriptive maps

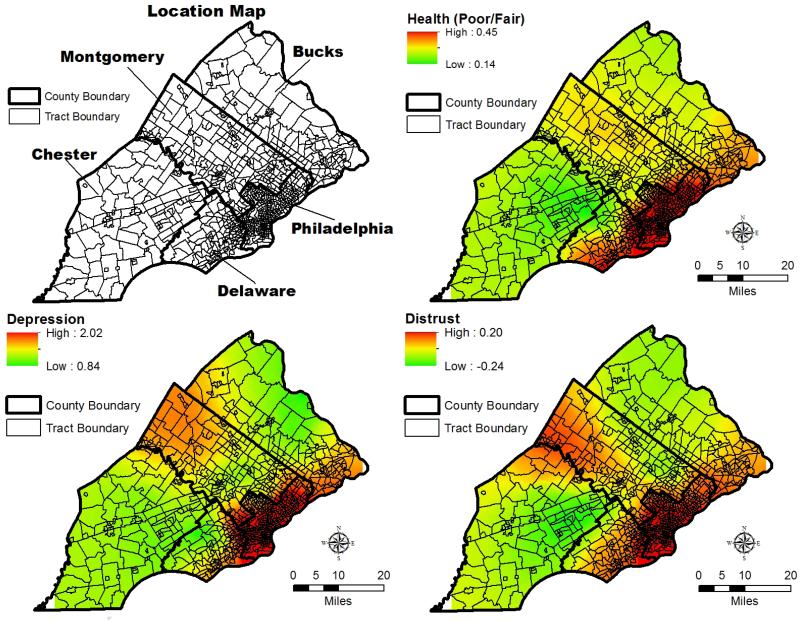

The geographically weighted descriptive univariate maps with a bandwidth of 519 are presented in Figure 1. The location map shows the patterning of census tracts within counties. Each local GWR model includes data on 519 residents (bandwidth); or on respondents from more than one county except in those cases where the model is based on residents in parts of Montgomery and Philadelphia counties (see Table 1). For the purpose of discussion we focus on distrust, self-rated health, and depression (other maps are available upon request).

Figure 1.

Spatial distributions of distrust, self-rated health, depression and IADL (Bandwidth = 519)

The highest level of distrust was concentrated on central city areas of Philadelphia (Philadelphia County) and Delaware County. Montgomery County also has relatively high distrust scores compared to the more suburban Bucks and Chester counties. Also, spatial variation within a county was evident (e.g. internal variation with Chester County, the county with the lowest average distrust). As earlier studies found (Armstrong et al., 2006; Mohseni and Lindstrom, 2007), distrust was associated with poor/fair self-rated health. The high prevalence of fair/poor self-rated health was found in Philadelphia County, and in the central and western parts of Montgomery County. The pattern of self-rated health was similar to that of distrust.

Depression revealed a similar spatial pattern to distrust. Explicitly, as argued in this study, health condition may be an antecedent extraneous factor. The geographically weighted descriptive maps in Figures 1 help convey the value of our approach. That is, our spatial exploratory data analysis suggested health conditions may confound the relationship between self-rated health and distrust. Also, these maps confirmed distrust varies spatially across southeast Pennsylvania. People living in or near central city areas have more distrust in the health care system than those living in suburban areas. The interpretations thus far are only based on univariate analysis. It is necessary to conduct regression analysis where competing explanations are considered so as to identify any spatially varying association between distrust and self-rated health.

3.3. Explanatory analytic results

Table 2 includes the non-spatial logistic regression results of three models (explained below) and in Figure 2 we present the spatially varying relationships between distrust and self-rated health after controlling for other covariates (GWR results). In Table 2, the VIFs among the independent variables indicate that multicollinearity is not biasing our estimates. The largest VIF is below 4. Note that the models in Table 2 are global models that describe the overall relationships between the independent and dependent variables. The appropriate way to demonstrate the local associations is to visualize the local estimates. We summarize our non-spatial modeling results below, followed by the interpretations of Figure 2.

Table 2.

Non-spatial logistic regression results of self-rated health (N=3,231)

| Model I | Model II | Model III | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | VIF | Coefficient | S.E. | Sig. | Odds Ratio | Coefficient | S.E. | Sig. | Odds Ratio | Coefficient | S.E. | Sig. | Odds Ratio |

| Constant | -.923 | .039 | *** | .397 | .342 | .486 | 1.408 | -1.377 | .560 | * | .252 | ||

| Distrust | 1.083 | .248 | .055 | *** | 1.281 | .266 | .061 | *** | 1.305 | .131 | .068 | 1.140 | |

| Demographic Variables | |||||||||||||

| White | 3.917 | -.007 | .190 | .993 | .029 | .216 | 1.030 | ||||||

| Black | 3.821 | .399 | .200 | * | 1.490 | .503 | .227 | * | 1.654 | ||||

| Male | 1.104 | .287 | .092 | ** | 1.332 | .415 | .102 | *** | 1.514 | ||||

| Age | 1.619 | -.006 | .006 | .994 | -.002 | .007 | .998 | ||||||

| Married | 2.278 | -.332 | .124 | ** | .718 | -.249 | .137 | .779 | |||||

| Widowed | 2.304 | -.011 | .131 | .989 | -.077 | .146 | .925 | ||||||

| Divorced | 1.523 | .054 | .161 | 1.056 | -.060 | .182 | .942 | ||||||

| Socioeconomic Variables | |||||||||||||

| Poverty | 1.148 | .408 | .151 | ** | 1.504 | .283 | .172 | 1.327 | |||||

| Employed | 1.325 | -.916 | .120 | *** | .400 | -.659 | .131 | *** | .517 | ||||

| High School Graduation | 2.808 | -.525 | .126 | *** | .592 | -.432 | .141 | *** | .649 | ||||

| Some College | 2.262 | -1.046 | .152 | *** | .351 | -.984 | .170 | *** | .374 | ||||

| College | 2.267 | -1.064 | .157 | *** | .345 | -.989 | .175 | *** | .372 | ||||

| Post-college | 2.114 | -1.301 | .180 | *** | .272 | -1.305 | .201 | *** | .271 | ||||

| Health Care Resources | |||||||||||||

| Without Regular Source of Care | 1.013 | .136 | .174 | 1.146 | .327 | .190 | 1.386 | ||||||

| Governmental Insurances | 1.195 | .225 | .123 | 1.253 | -.008 | .140 | .992 | ||||||

| Other Private Insurances | 1.601 | -.081 | .119 | .923 | -.084 | .133 | .920 | ||||||

| Health Conditions | |||||||||||||

| Chronic Diseases | 1.085 | 1.377 | .094 | *** | 3.961 | ||||||||

| High Blood Cholesterol | 1.046 | .353 | .093 | *** | 1.423 | ||||||||

| Depression | 1.179 | .201 | .025 | *** | 1.223 | ||||||||

| IADL | 1.178 | .412 | .044 | *** | 1.510 | ||||||||

| Non-spatial AIC | 3879.650 | 3576.271 | 3028.968 | ||||||||||

| GWR AIC | 3811.793 | 3568.959 | 3024.086 | ||||||||||

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.006 | 0.105 | 0.245 | ||||||||||

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

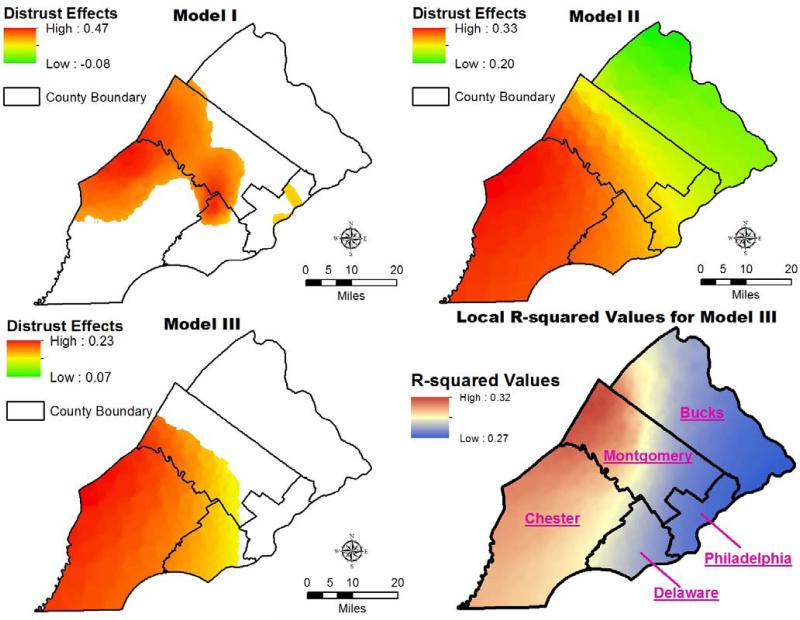

Figure 2.

The GWR spatial associations between health care system distrust and self-rated health

First, Model I (Table 2) shows that distrust had a significant association with self-rated health, without controlling for other covariates. Specifically, given a unit increase in the distrust score, the odds that a respondent reported fair/poor increased 28 percent (exp(0.248) - 1). Note the increase in the odds is not a linear function of the distrust score. For instance, a two unit increase in distrust leads to 64 percent increase (exp(0.248)^2 - 1) in the odds of reporting fair/poor health. The magnitude of the coefficient of distrust remained relatively stable in Model II in which socioeconomic, demographic, and health care resources variables are introduced.

Second, Models I and II replicate other published findings showing high distrust is associated with poor/fair self-rated health when taking demographic, socioeconomic, and health care resources variables into account. However, in Model III, when health condition variables are added, the global relationship between distrust and self-rated health was not significant. That is, the change between Model II and III is consistent with our first argument: the inclusion of health condition variables, in general, accounts for the distrust/self-rated health association among the elderly. The lack of significance for the distrust measure in Model III is only partial confirmation of our hypothesis. To more fully confirm our argument, health condition variables must also correlate with self-rated health. As shown in Table 2, all health condition variables in Model III were statistically significant predictors of self-rated health. Elderly with chronic diseases were almost 4 times more likely to report fair/poor health than did those without chronic diseases. Having high blood cholesterol had a relatively weak association with self-rated health compared to chronic diseases. The odds that a respondent reported fair/poor health increased over 40 percent with the presence of high blood cholesterol. Similarly, one reported depression symptom and daily limitation could result in a 22 percent and 51 percent increase in the odds of having fair/poor health, respectively. Coupled with the non-significant association between distrust and health in Model III, these results confirm the hypothesis that health condition is a shared determinant of self-rated health and distrust and explain their positive relationship (high distrust is associated with high likelihood of reporting poor/fair health).

Third, with respect to health care resources, there was no evidence they were related to self-rated health among the elderly. Compared to those having regular source of care and insurance, those without were more likely to report fair/poor health, but these associations were not statistically significant. One possible explanation is that in the PHMC 2008 data, the variations in health care resources were narrow. Over 95 percent of the elderly had regular sources of care and were covered by either governmental or private insurances (Table 1). A study in Chicago (Cagney et al., 2005) not only reported comparable numbers for the residents aged 55 and over, but also found the non-significant association between insurance coverage and self-rated health. Similarly, several studies reported no significant difference in self-rated health between the insured and the uninsured (Browning and Cagney, 2002; Finch and Vega, 2003).

Fourth, the model diagnostic statistic, AIC, indicated that the GWR models were preferred across the three nested models. When the AIC difference between two models are greater than 4, the one with higher AIC should be regarded as receiving considerably less statistical support and may not be considered in making inferences (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). With the inclusion of different sets of variables, both global and local AICs declined. The decrease in AICs implied that our explanatory variables improved the precision and complexity of the models. AICs declined with the inclusion of health condition variables (Model III). In other words, health conditions are important to include in studies of self-rated health, especially for the elderly.

Fifth, while the GWR models were preferred, we are unable to include all estimates from the analysis due to space constraints. However, we have summarized the local estimates for each regression model in Table 3, including minimum, median, and maximum values, as well as the percentage of significant local estimates. In addition, following Fotheringham et al.'s suggestion (2003), in Figure 2 we map the local associations of distrust with self-rated health each GWR model (I-III), and the local pseudo R-squared values for the final model (Model III). Note that the maps are designed to report only where local relationships are significant (i.e., p-value<0.05).

Table 3.

Summaries of the local estimates from the logistic GWR models of self-rated health (N=3,231)

| Model I† | Model II† | Model III† | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Min. | Med. | Max. | % Significant | Min. | Med. | Max. | % Significant | Min. | Med. | Max. | % Significant |

| Constant | -1.641 | -0.873 | -0.402 | 100% | 0.143 | 0.517 | 1.015 | 0% | -1.851 | -1.371 | -0.496 | 57% |

| Distrust | -0.083 | 0.184 | 0.473 | 22% | 0.200 | 0.274 | 0.328 | 100% | 0.067 | 0.131 | 0.227 | 34% |

| Demographic Variables | ||||||||||||

| White | 0.018 | 0.046 | 0.210 | 0% | 0.067 | 0.104 | 0.116 | 0% | ||||

| Black | 0.383 | 0.419 | 0.666 | 73% | 0.487 | 0.557 | 0.667 | 97% | ||||

| Male | 0.227 | 0.310 | 0.334 | 99% | 0.378 | 0.453 | 0.502 | 100% | ||||

| Age | -0.024 | -0.008 | -0.002 | 5% | -0.017 | -0.006 | 0.001 | 0% | ||||

| Married | -0.723 | -0.317 | -0.258 | 99% | -0.608 | -0.220 | -0.150 | 17% | ||||

| Widowed | -0.412 | 0.043 | 0.143 | 0% | -0.421 | -0.011 | 0.116 | 0% | ||||

| Divorced | -0.096 | -0.001 | 0.281 | 0% | -0.222 | -0.141 | 0.302 | 0% | ||||

| Socioeconomic Variables | ||||||||||||

| Poverty | 0.324 | 0.457 | 0.482 | 98% | 0.185 | 0.334 | 0.358 | 26% | ||||

| Employed | -1.061 | -0.893 | -0.847 | 100% | -0.815 | -0.590 | -0.559 | 100% | ||||

| High School Graduation | -0.668 | -0.473 | -0.454 | 100% | -0.852 | -0.331 | -0.268 | 73% | ||||

| Some College | -1.094 | -1.036 | -0.942 | 100% | -1.325 | -0.936 | -0.922 | 100% | ||||

| College | -1.271 | -0.923 | -0.896 | 100% | -1.317 | -0.838 | -0.806 | 100% | ||||

| Post-college | -1.594 | -1.099 | -1.060 | 100% | -1.741 | -1.055 | -0.998 | 100% | ||||

| Health Care Resources | ||||||||||||

| Without Regular Source of Care | 0.050 | 0.087 | 0.454 | 0% | 0.217 | 0.317 | 0.615 | 9% | ||||

| Governmental Insurances | -0.017 | 0.015 | 0.529 | 5% | 0.031 | 0.055 | 0.519 | 2% | ||||

| Other Private Insurances | 0.119 | 0.221 | 0.272 | 7% | -0.259 | 0.013 | 0.076 | 0% | ||||

| Health Conditions | ||||||||||||

| Chronic Diseases | 1.283 | 1.311 | 1.605 | 100% | ||||||||

| High Blood Cholesterol | 0.252 | 0.395 | 0.426 | 100% | ||||||||

| Depression | 0.185 | 0.201 | 0.222 | 100% | ||||||||

| IADL | 0.388 | 0.405 | 0.527 | 100% | ||||||||

Min. = minimum; Med. = median; Max. = maximum; % Significant = percentage of local estimates with p-values smaller than 0.05.

Without controlling for other covariates, the local magnitude of the correlations of distrust and self-rated health in Model I varied from 0.47 to -0.08 across the research area (see Table 3). However, not all local associations were statistically significant. The significant (and positive) relationships between distrust and poor/fair self-rated health were observed in the western regions of the Montgomery and north Chester County. Somewhat surprisingly, only two pockets of Philadelphia County had significant distrust/self-rated health relationships. Roughly 22% of the respondents (see Table 3) lived in these areas. The finding suggests that the association of distrust with self-rated health can be very localized, if no other independent covariates are considered.

Model II revealed different GWR results. With the inclusion of demographic, socioeconomic, and health care resources variables, distrust was found to be positively correlated with self-rated health, and local relationships were statistically significant over the entire study area. Though, note the magnitude of the association does vary across the study area (ranging from 0.33 to 0.20, Table 3), with the lowest values in the far north peaking in the central southern area. The finding that all local estimates of distrust were significant in Model II seemed to echo global model results (Table 2), and confirmed our expected theoretical distrust/self-rated health relationship.

As we anticipated, including health conditions in Model III changed the results. The magnitude and range of the relationship between distrust and health was reduced (with a maximum of 0.23 and minimum of 0.07) and the statistical significance of the estimates changed. Unlike Model II where the associations were statistically significant and pervasive across the study area, in Model III only the southwestern region had significant local statistics. That is, the relationships between distrust and self-rated health were strongest in the western part of the study area, specifically in Chester County (Figure 2 and Table 3).

Also we observed a spatial trend when comparing the final model, and Tables 2 and 3. The percentages of significant local estimates (Table 3) were all higher than 57% for covariates that were significant in the non-spatial logistic models (Table 2). As suggested (Fotheringham et al., 2002), the logistic GWR approach serves as a “spatial microscope” that may provide a clearer picture of where the relationships between independent and dependent variables are stronger/weaker across space. We note that the pseudo R-squared value for Model III in Table 2 is approximately 0.25, whereas the local pseudo R-squared values for the same model with logistic GWR ranges between 0.27 and 0.32 (Figure 2). That is, our final model seems to fit the data better in the Western Philadelphia metropolitan area (i.e., Chester and Montgomery Counties, the two counties with the lowest minority populations) than other areas. Table 3 and Figure 2 confirm the local spatial analysis perspective can help explain why the likelihood of reporting poor/fair health among the elderly differs spatially.

4. Discussion

We believe this study provides a substantive contribution to the study of health care system distrust. We replicated findings of earlier studies suggesting distrust is positively related to fair/poor self-rated health and in addition we contribute new substantive insights by investigating the role of health conditions. Controlling for health conditions among the elderly reveals a confounding relationship between distrust and self-rated health. The elderly with more health problems are not only more likely to report fair/poor health but also experience the frustrations or poor quality of health care services, increasing their levels of distrust (Armstrong et al., 2006; Corbie-Smith and Ford, 2006; Lee and Shinkai, 2003; Molarius and Janson, 2002). The average distrust score, for instance, for the elderly with one or more IADL (0.056) is higher than that of those without any (-0.015), and the difference in mean distrust scores is statistically significant (p-value < 0.05). While health condition of the elderly has been found to affect self-rated health (Damian et al., 2008; Sargent-Cox et al., 2008), it has not been used to account for the distrust/self-rated health relationship. In addition, our non-spatial logistic models confirmed our argument that health condition is an antecedent extraneous factor to which self-rated health and levels of distrust are related, especially among the elderly.

We also demonstrate the non-stationary relationships between distrust and self-rated health. Although distrust was not a significant predictor for self-rated health in the final non-spatial logistic regression model, the map of the GWR results showed distrust was significant among the elderly living in the southwest of the study area. Moreover, the spatial exploratory data analyses (Figure 1) confirmed our hypothesis that distrust varies across space; a result that no other study has tested. Only an explicit spatial perspective and model can reveal the complex relationships between self-rated health and distrust (corresponds to a recent study suggesting that place could matter in distrust studies (Yang et al., 2011)).

We offer two potential explanations for the spatially non-stationary association between distrust and self-rated health. The first relates to the difference in neighborhood socioeconomic conditions. Several recent studies indicated that the elderly living in an affluent neighborhood reported better psychosocial and physical well-being than their counterparts from a disadvantaged community (Everson-Rose et al., 2011; Walter Rasugu Omariba, 2010). However, other studies, including one focused on the Philadelphia County, did not find evidence for this (Fox et al., 2011; Yang and Matthews, 2010). Given the mixed findings in the literature, it is plausible the spatial non-stationarity revealed in this study may be due to the difference in residential composition (e.g., poverty rate) across neighborhoods within the Philadelphia metropolitan area and that the distrust/self-rated health relationships only holds for one-third of the respondents.

Variability in contextual factors, such as the local health care infrastructure (e.g., heavy traffic, physician offices, and health centers), is also a possible explanation for the non-stationarity in distrust and self-rated health. In general, the Philadelphia metropolitan area is well served by medical infrastructure, with the central city including some of the best hospitals in the state of Pennsylvania (US News and World Report, 2011). The four suburban counties each has at least six major hospitals and many more health clinics, community hospitals, and physician offices (ARF, 2009-2010). In general, the Philadelphia metropolitan area provides residents with high quality hospitals and medical professionals but there is inevitable variation in access to these health resources. Information on health care infrastructure was not included in this study. Future studies could explore not just health infrastructure but also other contextual variables associated with transportation and other built environment measures that may impact the elderly (Yang and Matthews, 2010).

As indicated above, spatial non-stationarity may lead to future research where linkages between individuals and contexts are clarified and that re-emphasizes the impacts of the uneven distribution of local resources (both social and tangible) on health (Ellaway et al., forthcoming). It should be noted that other analytic approaches (e.g., multilevel modeling) would be more appropriate than the single-level GWR models when the goal is to incorporate both compositional and contextual variables in analysis.

This study has several limitations. First, the PHMC and its elderly supplement data are cross-sectional and specific to the elderly residing in southeast Pennsylvania. Our interpretations are focused on associations rather than causal relationships, and we cannot generalize findings to other populations/areas. Second, measures of health care system distrust vary across studies. While we employ the latest distrust scale, different measures of distrust may yield different conclusions and also may find no spatial variation in the relationships between variables. Third, while the spatial randomization used in this study fits the distance-based kernel function more appropriately than using centroids, future analysis could be expanded by incorporating multiple imputation into the spatial randomization process. The multiple imputation approach may generate stable local estimates and permit more reliable inferences. Fourth, while GWR is a good exploratory tool for spatial non-stationarity, it has limitations, such as potential multicollinearity among local estimates, and lack of tests for non-stationarity in geographically weighted generalized linear regression models (Griffith, 2008; Wheeler and Tiefelsdorf, 2005).

Several implications could be drawn from our findings. The non-stationary association between distrust and self-rated health echoes the argument that “place” has not been adequately incorporated in health research (Goovaerts, 2008; Young and Gotway, 2010). The spatial non-stationarity observed in this study may serve as a tool for place-specific targeting and/or the tailoring of health and policy intervention. For example, the areas where distrust remains a significant predictor among the elderly could be prioritized for interventions that help reduce the likelihood of reporting poor/fair self-rated health and thus improve measures of population health. While physical health condition appears to be the antecedent extraneous factor accounting for the relationship between self-rated health and distrust, this association does not hold for one-third of the respondents who lived in the southwest of the Philadelphia metropolitan area. Individual's experience with health care system and studies of how the elderly utilize the local medical services (Mollborn et al., 2005) in this area may contribute to our understanding of the distrust/self-rated relationship. We note that detection of significant non-stationarity of distrust and self-rated health in some areas but not others implies that the formation of distrust among the elderly seems to be associated with factors beyond individual characteristics. These issues deserve further study.

Highlights.

High distrust is related to poor self-rated health, excluding health conditions.

High distrust is related to poor self-rated health, excluding health conditions. Taking health condition into account explains this association among the elderly.

Taking health condition into account explains this association among the elderly. The relationship between high distrust and poor self-rated health varies spatially.

The relationship between high distrust and poor self-rated health varies spatially. The distrust/self-rated health relationship holds for one-third of the respondents.

The distrust/self-rated health relationship holds for one-third of the respondents. GWR may be a useful exploratory tool in health applications.

GWR may be a useful exploratory tool in health applications.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Tse-Chuan Yang, The Social Science Research Institute The Population Research Institute The Pennsylvania State University 803 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16801 USA.

Stephen A. Matthews, Department of Sociology The Population Research Institute The Pennsylvania State University 601 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16801 USA. matthews@pop.psu.edu

References

- Akaike H. New Look at Statistical-Model Identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 1974;AC19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- ARF . Area Resource File. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions; Rockville, MD: 2009-2010. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K, McMurphy S, Dean LT, Micco E, Putt M, Halbert CH, Schwartz JS, Sankar P, Pyeritz RE, Bernhardt B, Shea JA. Differences in the patterns of health care system distrust between blacks and whites. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:827–833. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0561-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K, Rose A, Peters N, Long JA, McMurphy S, Shea JA. Distrust of the health care system and self-reported health in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:292–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besag J, Newell J. The Detection of Clusters in Rare Disease. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series a-Statistics in Society. 1991;154:143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Cagney KA. Neighborhood structural disadvantage, collective efficacy, and self-rated physical health in an urban setting. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43:383–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunsdon C, Fotheringham S, Charlton M. Geographically weighted regression-modelling spatial non-stationarity. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series D (The Statistician) 1998;47:431–443. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cagney KA, Browning CR, Wen M. Racial disparities in self-rated health at older ages: What difference does the neighborhood make? Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:S181–S190. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.s181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Ford CL. Distrust and poor self-reported health - Canaries in the coal mine? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:395–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00407.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C, Sohler N, Korin L, Gao W, Anastos K. HIV status, trust in health care providers, and distrust in the health care system among Bronx women. AIDS care. 2007;19:226–234. doi: 10.1080/09540120600774263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis A, Mills J, Leitner M. Spatial confidentiality and GIS: re-engineering mortality locations from published maps about Hurricane Katrina. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2006:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-5-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damian J, Pastor-Barriuso R, Valderrama-Gama E. Factors associated with self-rated health in older people living in institutions. BMC Geriatrics. 2008;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellaway A, Benzeval M, Green M, Leyland A, Macintyre S. “Getting sicker quicker”: Does living in a more deprived neighbourhood mean your health deteriorates faster? Health & Place. forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Everson-Rose SA, Skarupski KA, Barnes LL, Beck T, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF. Neighborhood socioeconomic conditions are associated with psychosocial functioning in older black and white adults. Health & Place. 2011;17:793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fefferman NH, O'Neil EA, Naumova EN. Confidentiality and confidence: Is data aggregation a means to achieve both? Journal of Public Health Policy. 2005;26:430–449. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch B, Vega W. Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003;5:109–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023987717921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham AS, Brunsdon C, Charlton M. Scale issues and geographically weighted regression. Modelling scale in geographical information science. 2001:123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham AS, Brunsdon C, Charlton M. Geographically Weighted Regression: The Analysis of Spatially Varying Relationships. Wiley; Chichester: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham AS, Brunsdon C, Charlton M. GWR 3.0: Software for Geographically Weighted Regression. GWR Manual. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Fox K, Hillsdon M, Sharp D, Cooper A, Coulson J, Davis M, Harris R, McKenna J, Narici M, Stathi A. Neighbourhood deprivation and physical activity in UK older adults. Health & Place. 2011;17:633–640. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatrell AC, Bailey TC, Diggle PJ, Rowlingson BS. Spatial point pattern analysis and its application in geographical epidemiology. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 1996;21:256–274. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N, Glei DA, Chang MC. The role of clinical risk factors in understanding self-rated health. Annals of Epidemiology. 2004;14:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein MS, Siegel JM, Boyer R. Predicting Changes in Perceived Health-Status. American Journal of Public Health. 1984;74:611–614. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.6.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goovaerts P. Geostatistical analysis of health data: state-of-the-art and perspectives. geoENV VI-Geostatistics for Environmental Applications. 2008:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DA. Spatial-filtering-based contributions to a critique of geographically weighted regression (GWR). Environment and Planning A. 2008;40:2751–2769. [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. Researching medical trust in the United States. Journal of Health Organization and Management. 2006;20:456–467. doi: 10.1108/14777260610701812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Quarterly. 2001;79:613–639. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B. Depressive symptoms and self-rated health in community-dwelling older adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:1549–1556. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin R. Conceptions and explanations of trust. In: Cook K, editor. Trust in Society. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hill M. SPSS Missing Value Analysis 7.5. SPSS; Chicago: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, Artin KHH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult - Criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159:1701–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylha M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns RA, Gesler WM. Putting health into place: Landscape, identity, and well-being. Syracuse Univ Pr. 1998.

- Kutner M, Nachtsheim C, Neter J. Applied Linear Regression Methods. MCGraw-Hill/Irwin; Chicago: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis A. A note regarding the condition number: the case of spurious and latent multicollinearity. Quality and Quantity. 2007;41:123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Shinkai S. A comparison of correlated self-rated health and functional disability of older persons in the Far East: Japan and Korea. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2003;37:63–76. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(03)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung Y, Chang-Lin M, Wen-Xiu Z. Statistical tests for spatial nonstationarity based on the geographically weighted regression model. Environment and Planning A. 2000;32:9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki R, Bunker B. Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships. In: Kramer R, Tyler T, editors. Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lyness JM, Noel TK, Cox C, King DA, Conwell Y, Caine ED. Screening for depression in elderly primary care patients - A comparison of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale and the geriatric depression scale. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157:449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyyra TM, Leskinen E, Jylha M, Heikkinen E. Self-rated health and mortality in older men and women: A time-dependent covariate analysis. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2009;48:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield ER, Helms BP. Detecting multicollinearity. American Statistician. 1982:158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni M, Lindstrom M. Social capital, trust in the health-care system and self-rated health: The role of access to health care in a population-based study. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1373–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molarius A, Janson S. Self-rated health, chronic diseases, and symptoms among middle-aged and elderly men and women. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2002;55:364–370. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00491-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollborn S, Stepanikova I, Cook KS. Delayed care and unmet needs among health care system users: When does fiduciary trust in a physician matter? Health Services Research. 2005;40:1898–1917. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00457.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw S. The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem. Geobooks; Norwich, England: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- PHMC . Philadelphia Health Management Corporation. The 2008 Household Health Survey; Philadelphia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rose A, Peters N, Shea JA, Armstrong K. Development and testing of the health care system distrust scale. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent-Cox KA, Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA. Determinants of Self-Rated Health Items With Different Points of Reference. Journal of Aging and Health. 2008;20:739. doi: 10.1177/0898264308321035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological methods. 2002;7:147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea JA, Micco E, Dean LT, McMurphy S, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K. Development of a revised health care system distrust scale. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:727–732. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0575-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SV, Kim DJ, Kawachi I. Social trust and self-rated health in US communities: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2002;79:S21–S34. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.suppl_1.S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom DH, Hall MA, Pawlson LG. Measuring patients’ trust in physicians when assessing quality of care. Health Affairs. 2004;23:124–132. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau 2010 Census Demographic Profiles. 2010.

- US News and World Report . Best Hospitals in Philadelphia, PA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Walter Rasugu Omariba D. Neighbourhood characteristics, individual attributes and self-rated health among older Canadians. Health & Place. 2010;16:986–995. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks JR. The role of spatial analysis in demographic research. In: Goodchild M, Janelle DG, editors. Spatially Integrated Social Science: Examples in Best Practice. Oxford University Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler D, Tiefelsdorf M. Multicollinearity and correlation among local regression coefficients in geographically weighted regression. Journal of Geographical Systems. 2005;7:161–187. [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K, Leserman J, Whetten R, Ostermann J, Thielman N, Swartz M, Stangl D. Exploring lack of trust in care providers and the government as a barrier to health service use. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:716–721. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TC, Matthews SA. The role of social and built environments in predicting self-rated stress: a multilevel analysis in Philadelphia. Health & Place. 2010;16:803–810. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TC, Matthews SA, Shoff C. Individual Health Care System Distrust and Neighborhood Social Environment: How Are They Jointly Associated with Self-rated Health? Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88:945–958. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9561-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LJ, Gotway CA. Using Geostatistical Methods in the Analysis of Public Health Data: The Final Frontier? geoENV VII-Geostatistics for Environmental Applications. 2010;16:89–98. [Google Scholar]