Abstract

TNF (designated as TNF-α under previous nomenclature) is the preeminent activator of MMP-9 generation from a variety of cells including eosinophils. We have previously established that TNF strongly synergizes with IFN-γ and IL-4 for eosinophil synthesis of Th1- and Th2-type chemokines respectively. Thus, we sought to determine if TNF-induced synthesis of MMP-9 would be enhanced by the presence of Th1, Th2, or the eosinophil-associated common beta chain (βc) cytokines. Human blood eosinophils were cultured with TNF alone or in combination with either IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-3, IL-5, or GM-CSF. Concentrations and activities of MMP-9 in eosinophil culture supernates were measured by ELISA and gelatin zymography, mRNA transcription and stabilization by quantitative real-time PCR, and signaling events by immunoblotting and intracellular flow cytometric analysis. Singularly, TNF, GM-CSF, or IL-3, but not IL-4 or IFN-γ, induced relatively small (<0.2 ng/ml) but statistically significant quantities of MMP-9. Remarkable synergistic synthesis of MMP-9 (ng/ml levels) occurred in response to TNF plus IL-3, GM-CSF or IL-5, in the order of IL-3>GM-CSF>IL-5. Zymography revealed that eosinophils release MMP-9 in its pro-form. Eosinophil stimulation with the combination of IL-3 plus TNF led to increased steady-state levels of MMP-9 mRNA, prolonged mRNA stabilization, and enhanced activation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Inhibition of NF-κB, MEK kinase, or p38 MAP kinase, but not JNK signaling pathways, diminished IL-3/TNF-induced MMP-9 mRNA and protein production. Thus, the synergistic regulation of eosinophil MMP-9 by IL-3 plus TNF likely involves cooperative interaction of multiple transcription factors downstream from ERK, p38, and NF-κB activation as well as post-transcriptional regulation of MMP-9 mRNA stabilization. Our data indicate that within microenvironments rich in βc-family cytokines and TNF, eosinophils are an important source of proMMP-9 and highlight a previously unrecognized role for synergistic interaction between TNF and βc-family cytokines, particularly IL-3, for proMMP-9 synthesis.

Keywords: IL-3, IL-5, GM-CSF, MMP-9, mRNA stability, MAP kinase

1. Introduction

MMP-9 is a proteolytic enzyme involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation and turnover accompanying tissue injury and remodeling. MMP-9 is released from most cells as a 92 kDa zymogen, which is then activated by removal of the prodomain via other proteases such as MMP-2, -3, -7, -10, and -13, cathepsin G, plasmin, and trypsin [1–3]. Active MMP-9 may participate in acute inflammation by facilitating cellular migration and be instrumental in ECM degradation and tissue destruction [4]. Paradoxically, MMP-9 may also play a role in tissue remodeling by enzymatically releasing sequestered profibrotic factors, activating latent TGF-β, inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and contributing to angiogenesis [4–7]. Interestingly, a recent report demonstrated an association between MMP-9+ eosinophils and tenascin-C in skin diseases [8].

Ex vivo, eosinophils can release MMP-9 in response to TNF [9,10], 5-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid [11], complement C5a [12], or platelet activating factor [13]. The contribution of βc-family cytokines (IL-5, GM-CSF, and IL-3) to eosinophil MMP-9 generation has not been established. Early reports showed little or no MMP-9 release following eosinophil stimulation with IL-5 or IL-3 [10,14]. However, Okada et al. demonstrated that eosinophil migration through ECM was mediated by MMP-9 and was induced by eosinophil exposure to the combination of IL-5 and platelet activating factor [13]. These data suggest that for optimal production of MMP-9 in response to IL-5, eosinophils may require additional signals such as those that would be present in an inflammatory environment.

We have previously established that TNF provides a potent synergistic signal with IL-4 and IFN-γ for eosinophil release of Th2 and Th1 chemokines, respectively [15]. Compared with other cell types such as monocytes and macrophages, eosinophils were unique in their requirement for both TNF and IFN-γ for generation of Th1-type chemokines CXCL-9/MIG and CXCL-10/IP-10 [15]. Based on the strong synergistic activation of eosinophils by TNF and reports that TNF, and in some studies IL-5, could induce secretion of low levels of MMP-9 by eosinophils, we hypothesized that the combination of TNF and IL-5 would enhance eosinophil generation of MMP-9 to physiologically relevant concentrations. Since signal transduction from the IL-5, IL-3, and GM-CSF receptors is mediated through βc (CD131), this family of cytokines tends to have similar effects on eosinophils [16]. Thus, we sought to determine the relative contribution of βc-family cytokines and TNF to MMP-9 release and gene expression in human eosinophils. Finally, we explored the potential signaling mechanisms underlying the induction of eosinophil MMP-9 synthesis and the role of mRNA stability in accumulation of MMP-9 mRNA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Human subjects

The study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Health Sciences Human Subjects Committee. Informed written consent was obtained from each subject prior to participation. Peripheral blood for purification of circulating eosinophils was donated by allergic volunteers (skin prick test positive with a history of allergic rhinitis) ranging in age from 18 to 58 years. None of the subjects took medications that would affect the study results or had evidence of a respiratory infection within the previous four weeks.

2.2 Eosinophil purification

Eosinophils were purified from heparinized blood as previously described [15]. Briefly, the granulocyte fraction was obtained by centrifugation over Percoll (1.090 g/ml), RBCs were lysed with water, and extensive negative depletion was performed with anti-CD16, -CD3, and -CD14 immunomagnetic beads (AutoMac system, Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA, USA). Eosinophil purity was >99%.

2.3 Cell culture, ELISA, and zymography

Eosinophils were cultured at 2×106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) or 2% human serum albumin (HSA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and stimulated with 10 ng/ml of IL-4, IFN-γ, IL-3, IL-5, or GM-CSF alone or in combination with TNF for up to 72 hours as indicated. For experiments assessing the synergistic effect of IL-3 plus TNF, a checkerboard type experiment was performed using 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 ng/ml of IL-3 and TNF. The synergistic effect of IL-3 plus TNF became apparent at 1 ng/ml of each cytokine and was maximal at 10 ng/ml. Due to donor-to-donor variability, three concentrations of the pharmacological inhibitors SB203580 (0.5, 1, and 2 µM), U0126 (2, 5, and 10 µM), JNK inhibitor II (5, 10, and 20 µM), and BAY11-7052 (1, 2, and 4 µM) and equivalent concentrations of corresponding analogues were used for each donor. Cells were pretreated with inhibitors for 1 hour and cultured for an additional 24 hours. The concentrations of MMP-9 in culture supernates were analyzed by an “in-house” sandwich ELISA as previously described [17], utilizing mouse anti-human MMP-9 coating antibody (Ab) (clone 36020), biotinylated goat anti-human MMP-9 Ab, and recombinant human MMP-9 protein standard purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The assay detects both pro and active forms of MMP-9 and has a sensitivity of <3 pg/ml. To distinguish between pro and active MMP-9, zymography was performed as we have previously described [17]. Culture supernates (20 µl per well) were resolved by electrophoresis on 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide (SDS-PAGE) gels copolymerized with 3 mg/ml porcine gelatin. The 1.5 mm minigels were renatured and developed, and gelatinase activity was visualized using an imaging system (Alpha Innotech/ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Application of 20 µl of two-fold dilutions of recombinant proMMP-9 established a linear range of sensitivity from 6000 to 25 pg per well.

2.4 Quantitative real-time PCR

Levels of MMP-9 gene expression were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) as previously described [15]. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from cultured eosinophils (1×106 cells per treatment) using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), reverse transcription was performed using the Superscript III System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and MMP-9 mRNA levels were determined by qPCR in the Applied Biosystems (ABI/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) 7500 Sequence detector. Human MMP-9 (reference sequence NM_004994.2, ABI ID Hs00234579_m1) and the β-glucuronidase (GUS, reference sequence NM_000181.2, ABI Assay ID Hs99999908_m1) specific primers and TaqMan hydrolysis probe were obtained from ABI. The relative expression of MMP-9 was expressed as fold change using the comparative cycle threshold (Ct) method (ΔCt = Ct of the MMP-9 gene - Ct of GUS; ΔΔCt = ΔCt of stimulated cells at the indicated time points - ΔCt of unstimulated cells at 0 hours; and fold change = 2−ΔΔCt). The efficiency of transcription for GUS and MMP-9 were 89 and 99%, respectively. The quantification cycle for GUS was approximately 25 at 0 hours, was highly consistent among experiments, and did not change with treatment.

2.5 Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described [15] on cell lysates from eosinophils stimulated for 5 min (the optimal time point was determined by a pilot kinetic study of 5, 15, and 30 min). Ab included rabbit anti-phospho-p38 MAP kinase (Genetel Laboratories, LLC, Madison, WI, USA), rabbit anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (pTpY185/187, Biosource/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), phospho-JNK1/2 (Genetel), rabbit anti-phospho-STAT5 (Tyr694, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and total IκB-α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Immunoreactive bands were visualized with Super Signal West Femto chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal protein loading with the same cell lysates was determined by simultaneous probing of each well with β1-integrin Ab (Chemicon/Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Bands were visualized using the FluorChem® Q Imaging System (Alpha Innotech/ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.6 Intracellular flow cytometric analysis

Intracellular flow cytometric analysis was performed as previously described [15]. Briefly, after stimulation, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 37°C, permeabilized with 90% methanol on ice for 30 min, and incubated for 45 min with PE-conjugated NF-κB p65 (pS529) or mouse IgG isotype control. For analysis, 10,000 events were collected using a BD Immunocytometry Systems FACSCalibur, and data analyses were performed using the CellQuest software package (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

2.7 mRNA decay

MMP-9 mRNA stabilization studies were performed as previously described [18] with the following changes. Eosinophils were treated with IL-3 or TNF alone and in combination for 15 h, actinomycin-D (50µg/ml) was then added and cells were harvested at the indicated time points. MMP-9 mRNA levels were determined by qPCR as described above, and mRNA levels at the addition of transcription inhibitor (T = 0 h) were set to 100%.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Results are summarized as mean ± SEM. Mixed-effects ANOVA models were used to compare different treatments or time points. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed in the R environment (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1 Synergistic induction of eosinophil MMP-9 by TNF in combination with βc-family cytokines

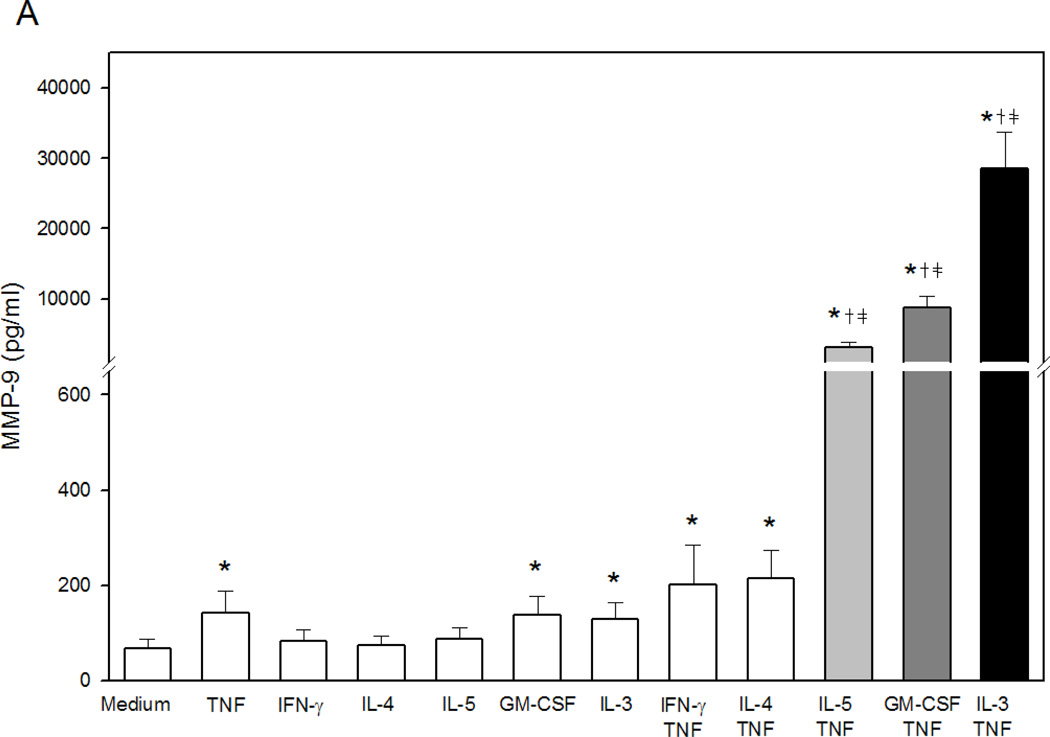

Stimulation of eosinophils with Th1 or Th2 cytokines for up to 72 h did not induce MMP-9 generation. TNF, GM-CSF, or IL-3 alone induced statistically significant but small concentrations of MMP-9 (Fig. 1A). When combined with TNF, each βc-family cytokine synergistically induced large amounts of MMP-9 with IL-3>GM-CSF>IL-5 (Fig. 1A). The robust effect of IL-3 versus IL-5 or GM-CSF was evident as early as 24 h and peaked at 48 to 72 h (Fig. 1B). MMP-9 release in response to TNF plus βc-family cytokines was confirmed utilizing recombinant cytokines prepared in E. coli and insect cells from various vendors (data not shown). Since the most potent stimulus for eosinophil MMP-9 generation was the combination of IL-3 plus TNF, subsequent experiments were performed with IL-3 in the presence or absence of TNF.

Figure 1. βc-family cytokines plus TNF-induced eosinophil proMMP-9.

(A) Concentrations of total MMP-9 in supernates from eosinophils (2×106 cells/ml) stimulated 72 h (n=11 subjects, p<0.05, verses *medium, †TNF, or ‡respective single cytokine). (B) Kinetics of MMP-9 generation by eosinophils (2×106 cells/ml) cultured for 3, 24, 48, or 72 h with medium alone, TNF plus IL-5, GM-CSF, or IL-3, respectively (p<0.05, verses *medium, †TNF, or ‡respective single cytokine).

The synergistic effect of IL-3 plus TNF does not appear to be due to an effect on cell viability. When eosinophils were cultured for 72 h, the addition of TNF did not affect the enhanced viability induced by IL-3 alone. Eosinophil viability was <2 % when cells were cultured for 72 h in medium alone or TNF alone, 87 ± 2 % in IL-3 alone, and 86 ± 2 % in IL-3+TNF (mean ± SD for 5 subjects).

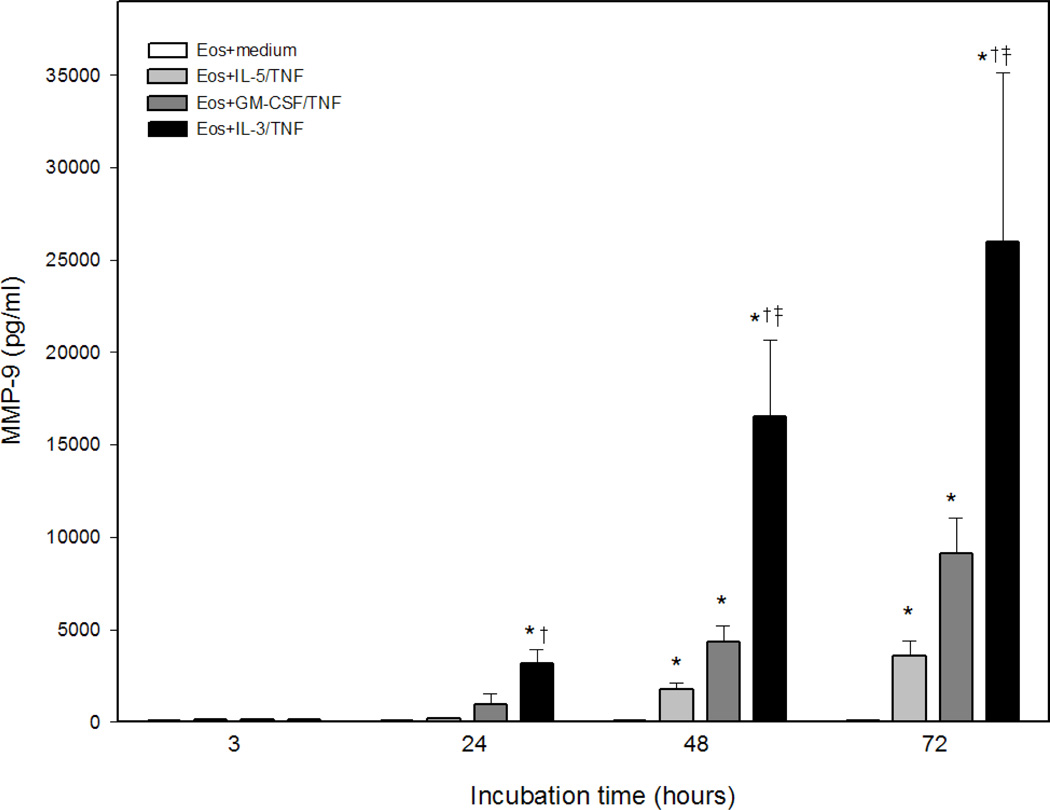

Eosinophils or neutrophils cultured in serum-free medium have been reported to release MMP-9 within minutes of stimulation with TNF, suggesting rapid release from intracellular stores [9,19]. In contrast to a previous report [9], we did not detect rapid release of copious amounts MMP-9. In fact, highly purified human blood eosinophils stimulated with TNF ± IL-3 for 1 h released only very small amounts of proMMP-9 as detected by zymography (Fig. 2A). The presence of endogenous gelatinase activity in cell-free medium containing serum (FBS) (Fig. 2B) obscured detection of eosinophil-derived MMP-9 enzymatic activity. However, when cells were stimulated in serum-free medium containing albumin (HSA) as a protein source, a small amount of eosinophil-derived MMP-9 enzymatic activity could be detected within 1 h (Fig. 2C). Conversely, at 72 h, addition of IL-3 to TNF highly increased proMMP-9 levels when eosinophils were cultured in medium containing either HSA or FBS (Fig. 2B). At variance with reports showing the presence of the active 84 kDa form of MMP-9 in supernatant fluids from eosinophils stimulated to undergo basement membrane transmigration [12,13,20], in the present studies the combination of IL-3 plus TNF did not lead to eosinophil conversion of proMMP-9. Importantly, the lack of activity corresponding to complexes of MMP-9 with neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin indicates an absence of contaminating neutrophils in our eosinophil preparations.

Figure 2. Early (1 h) and late (72 h) release of MMP-9 by eosinophils.

(A and C) Concentrations of total MMP-9 (pg/ml of supernate) or (B and D) gelatinase activity in 20 µl supernate from eosinophils (2×106 cells/ml) stimulated with TNF ± IL-3 (10 ng/ml) for 1 or 72 h in medium containing human serum albumin or fetal bovine serum. Recombinant proMMP-9 (MW=92 kDa) was used as a positive control in lane 1 of the zymograms. (Representative of 2 subjects.)

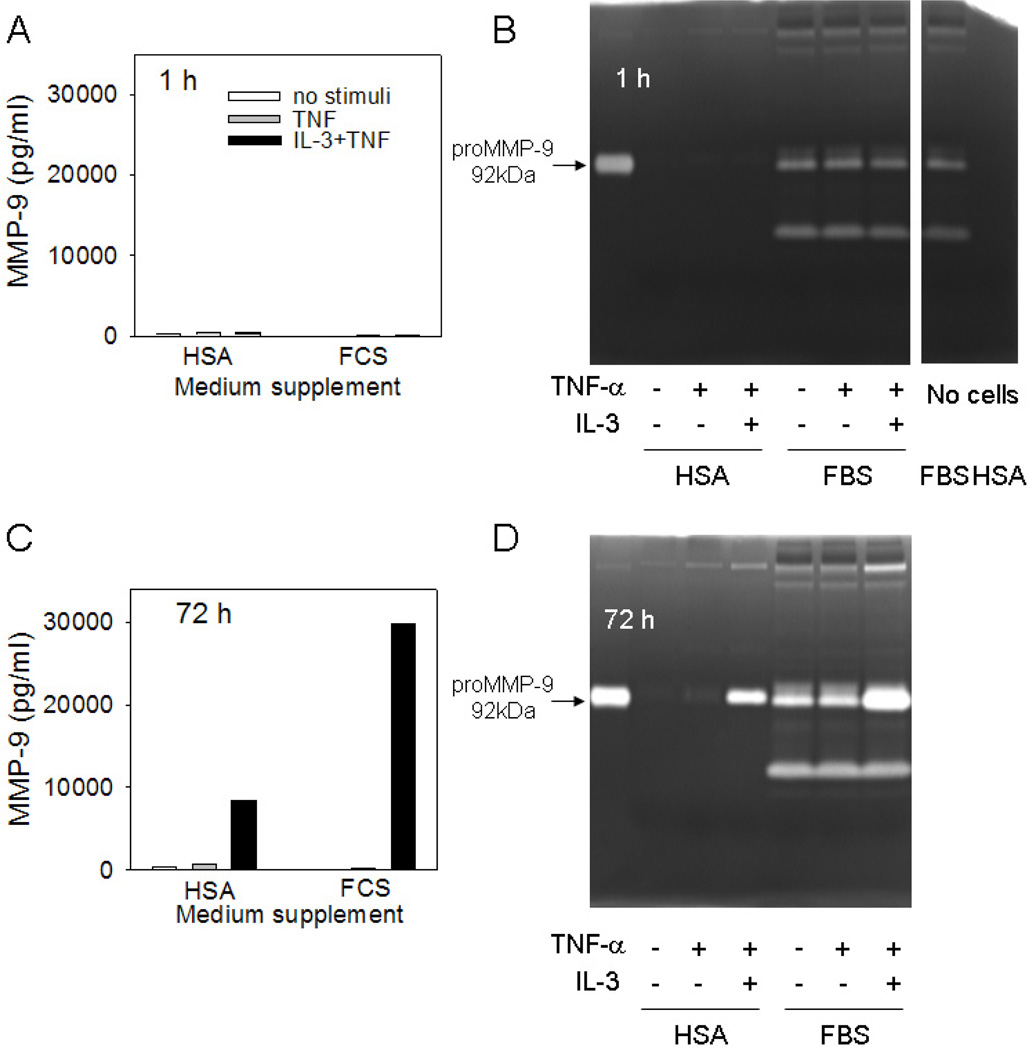

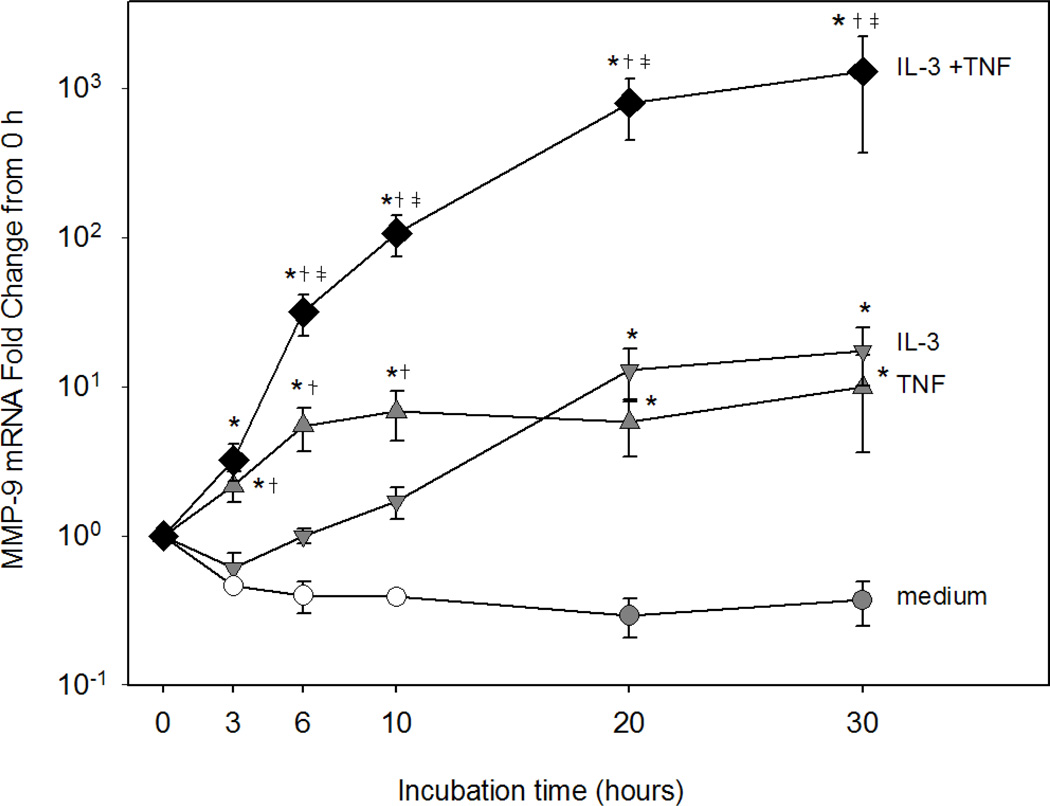

3.2 Kinetics of eosinophil MMP-9 gene expression in response to IL-3 plus TNF

MMP-9 gene expression was assessed by reverse transcription and qPCR. IL-3 or TNF alone induced statistically significant but modest levels of MMP-9 mRNA compared to the medium control (Fig. 3). MMP-9 mRNA expression was significantly increased as early as 3 h and peaked at 6 h in eosinophils treated with TNF alone. With IL-3 treatment, there was no significant increase in MMP-9 mRNA until 20 h. However, remarkable synergistic expression of MMP-9 mRNA occurred when eosinophils were stimulated with IL-3 plus TNF. Enhanced MMP-9 gene expression was detected within 3 h, and by 6 h, mRNA levels were significantly greater in eosinophils treated with IL-3 plus TNF compared to those treated with either cytokine alone. Notably, with the combination treatment, levels of MMP-9 mRNA continually increased for at least 20 h and enhanced MMP-9 gene expression was sustained for at least 30 h. The combination of TNF with either IL-5 or GM-CSF also induced significantly greater levels of MMP-9 mRNA compared to stimulation with medium or either cytokine alone (data not shown).

Figure 3. IL-3 plus TNF-induced eosinophil MMP-9 mRNA.

Eosinophils were cultured with medium (circles), IL-3 (down triangles), TNF (up triangles), or IL-3 plus TNF (diamonds). MMP-9 mRNA levels were determined by qPCR and normalized to β-glucuronidase and expressed as fold change (2-ΔΔCt). Data are mean ± SEM of 4–5 subjects (closed symbols) or two subjects (open circles). p<0.05, versus *medium, †IL-3, or ‡TNF.

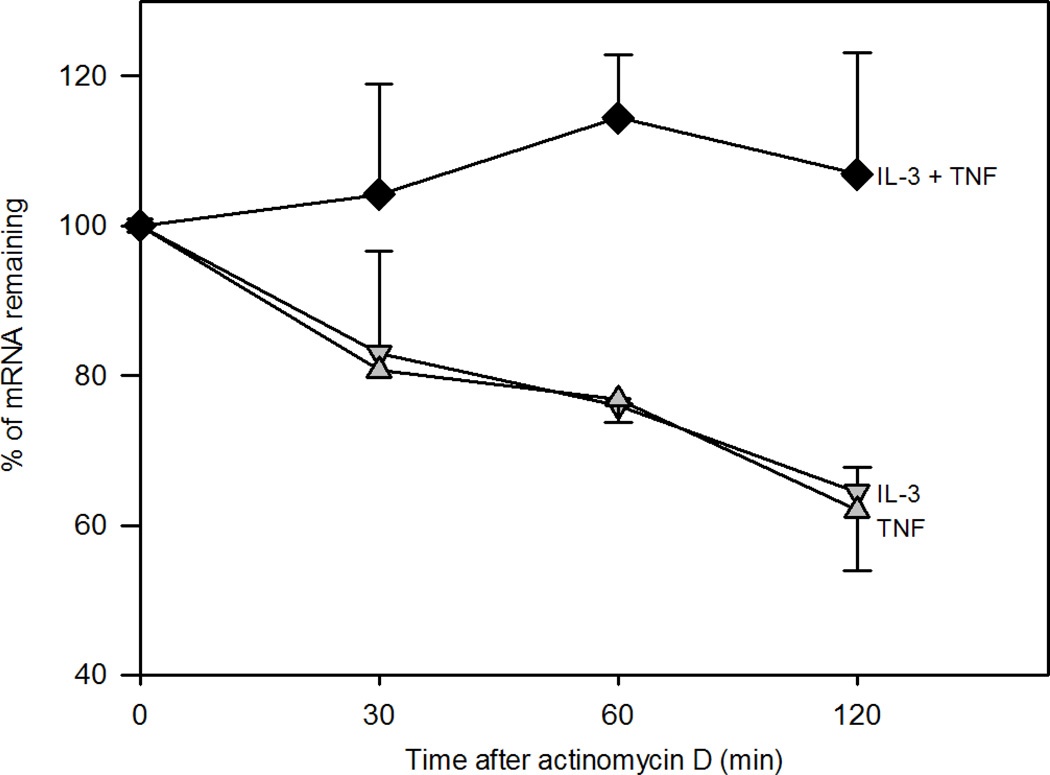

3.3 IL-3 plus TNF stabilizes MMP-9 mRNA

To determine if the synergistic effect of IL-3 plus TNF on MMP-9 synthesis involves mRNA stabilization, we assessed MMP-9 mRNA decay after blocking de novo transcription with actinomycin D. In contrast to eosinophils activated with TNF or IL-3 alone, no MMP-9 mRNA decay was observed for up to 2 h after activation with IL-3 plus TNF (Fig. 4). These data suggest that the accumulation of eosinophil MMP-9 mRNA in response to IL-3 plus TNF is due at least in part to mRNA stabilization.

Figure 4. Effect of IL-3 plus TNF on MMP-9 mRNA stability.

Eosinophils were cultured for 15 h with IL-3 (down triangles), TNF (up triangles), or IL-3 plus TNF (diamonds). Cells were harvested at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min after addition of actinomycin D, and MMP-9 mRNA was quantified by qPCR. Data were normalized to β-glucuronidase and expressed as the % of mRNA remaining compared to T0. Data are mean ± SEM of 3 subjects.

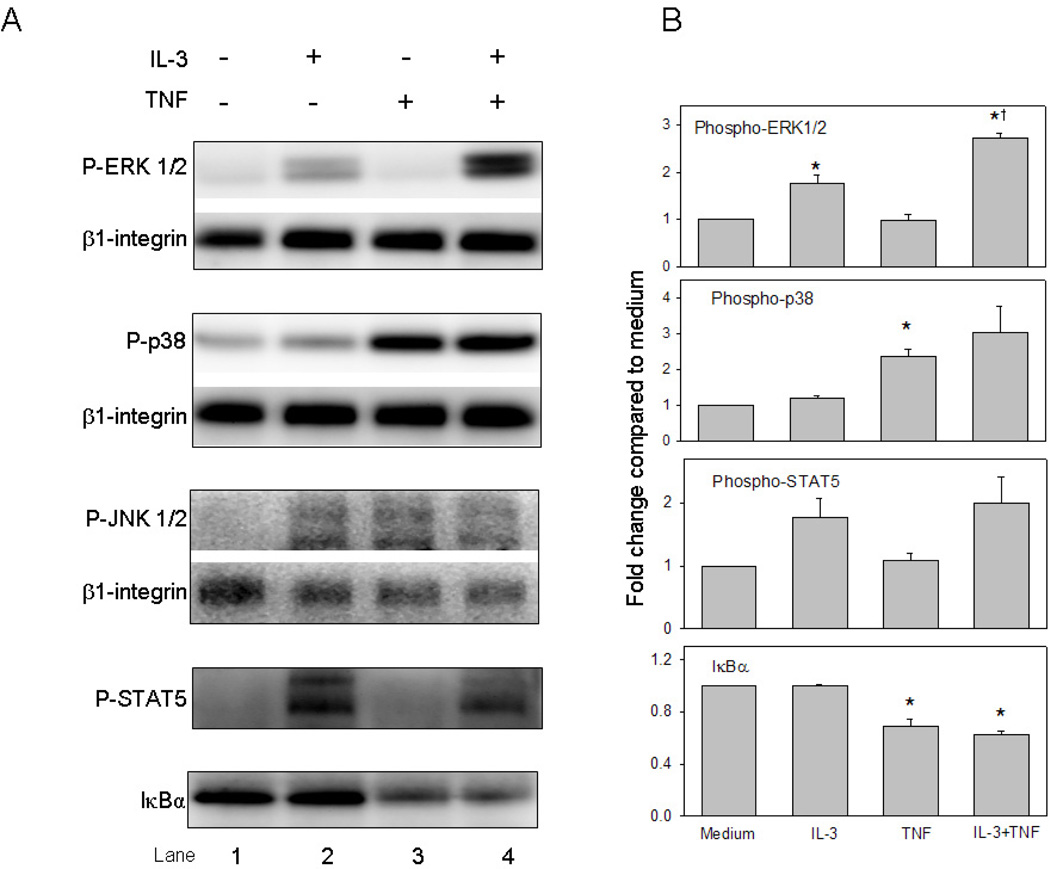

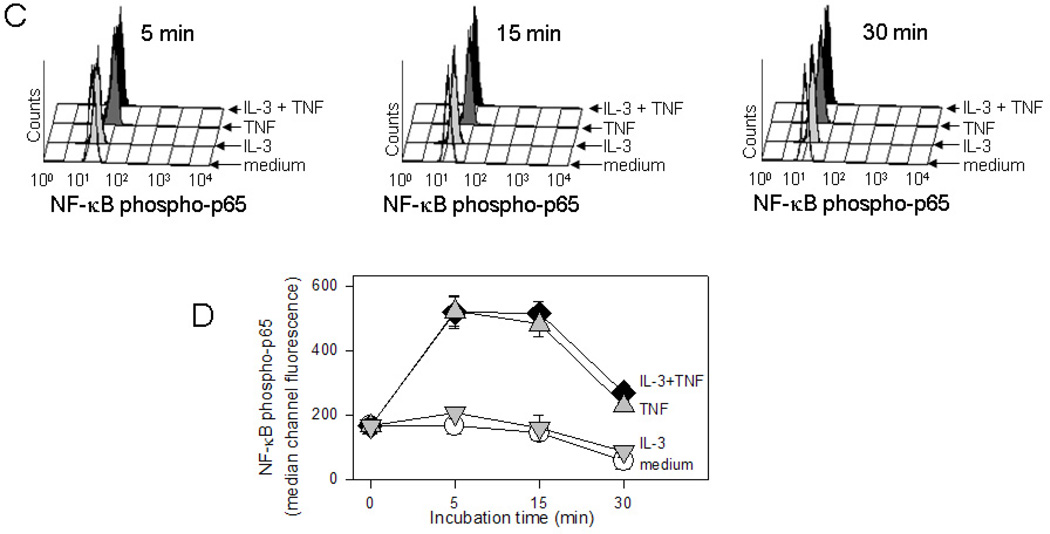

3.4 Enhanced ERK1/2 phosphorylation by IL-3 plus TNF

Immunoblot analysis was used to determine activation of MAP kinases, STAT5, and NF-κB signaling pathways elicited by eosinophil stimulation with IL-3 ± TNF. Consistent with previous reports [21–23], ERK1/2 and STAT5 were activated within 5 min by IL-3 whereas p38 MAP kinase and NF-κB were activated by TNF (Fig. 5A and B). Compared to either cytokine alone, the combination of IL-3 plus TNF enhanced ERK1/2 phosphorylation; there was no significant augmentation of p38 MAP kinase or further degradation of the NF-κB inhibitory factor IκB-α. Similar results were observed at 15 min (data not shown). Detection of phospho-JNK1/2 in eosinophils was poor despite using an antibody previously validated on fibroblast lysates. Since immunoblot analysis did not indicate a trend toward increased degradation of IκB-α in the presence of TNF plus IL-3, the kinetics of phosphorylation of the p65 subunit of the NF-κB transcription factor was assessed utilizing the technique of intracellular flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 5C and D). TNF-induced eosinophil NF-κB p65 activation was detectable at 5 min, subsided within 30 min, and was not affected by the addition of IL-3. Thus, within the time frame studied, only ERK1/2 activation was further enhanced by eosinophil stimulation with the combination of IL-3 plus TNF.

Figure 5. Signaling cascades initiated by IL-3 plus TNF.

(A) Representative immunoblots and (B) immunoblot densitometric analysis (n=3 subjects; p<0.05, versus *medium or †IL-3) of phosphorylated MAP kinases, phospho-STAT5, and IκBα in eosinophils cultured for 5 min. (C) Representative three-dimensional histograms for detection of NF-κB phospho-p65 by flow cytometric analysis. Eosinophils were cultured for 5, 15, and 30 min with medium alone (no color), IL-3 (light gray), TNF (dark gray), or IL-3 plus TNF (black). (D) Summarized median channel fluorescence (MCF) from 4 individual subjects are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

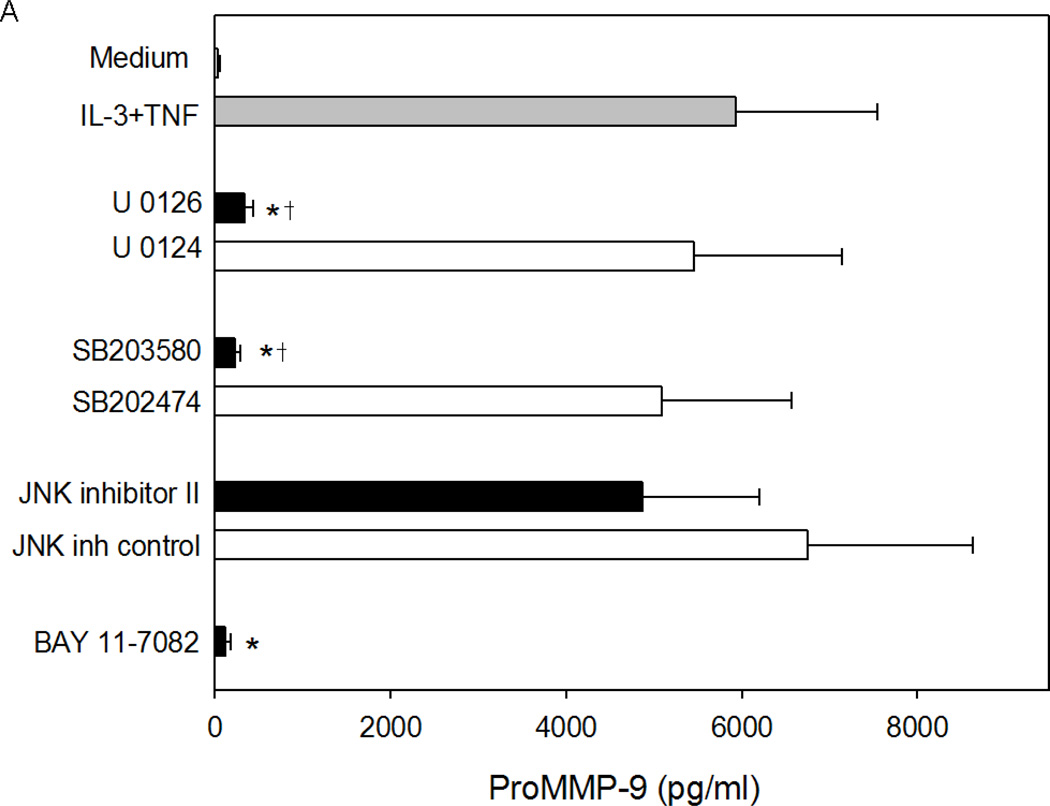

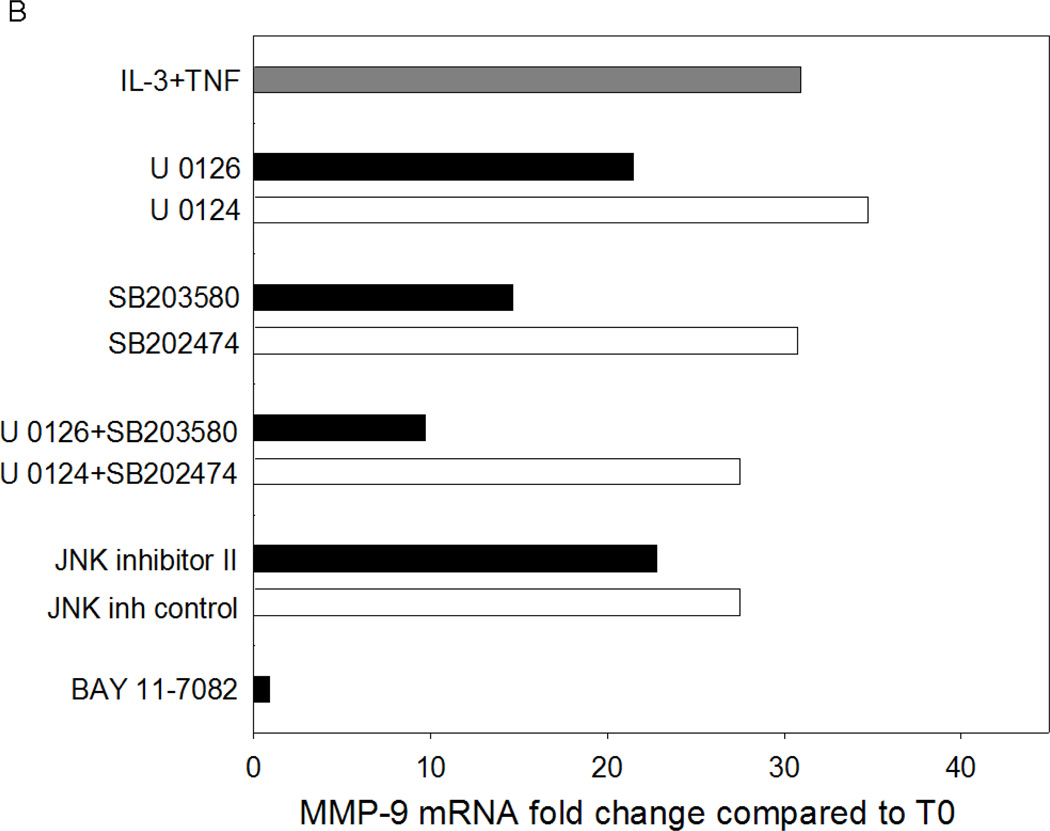

Based on the signaling cascades induced by IL-3 and TNF, the related chemical inhibitors were used to determine the contribution of MAP kinases and/or NF-κB to the synergistic induction of eosinophil MMP-9 protein and mRNA by IL-3 plus TNF. At the protein level, IL-3 plus TNF-induced eosinophil MMP-9 was nearly abolished by the MEK kinases inhibitor (U0126), p38 MAP kinase inhibitor (SB203580), or IκB-α phosphorylation inhibitor (BAY 11-7082), whereas inhibition of JNK had little or no effect (Fig. 6A). A similar pattern of inhibition was seen at the mRNA level (Fig. 6B); however, the magnitude of the reduction was less than with MMP-9 protein. Simultaneous blockade of ERK and p38 kinases resulted in more than 60% inhibition, but did not obliterate MMP-9 mRNA (Figure 6B) detection, suggesting that MAP kinases might also have a role in proMMP-9 accumulation downstream of mRNA expression. Thus, the MEK kinases, p38 MAP kinase, and NF-κB pathways are all required for the synergistic synthesis of MMP-9 in response to eosinophil stimulation with IL-3 plus TNF.

Figure 6. Effect of MAP kinase and NF-κB inhibitors on IL-3 plus TNF-induced eosinophil MMP-9.

Eosinophils were preincubated for 1 h as indicated with the MEK kinase inhibitor U0126 or its inactive analogue U0124, the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 or its inactive analogue SB202474, the JNK inhibitor II or its inactive analogue, or the NF-κB inhibitor BAY 11-7082 and then stimulated with IL-3/TNF. (A) MMP-9 protein at 24 h (mean ± SEM of 5 subjects; p<0.05, versus *IL-3/TNF alone or †its inactive analogue). (B) MMP-9 mRNA at 6 h (average of 2 subjects).

4. Discussion

We have demonstrated that βc-family cytokines, notably IL-3, in combination with TNF synergistically induced the synthesis of profuse amounts of proMMP-9 by human eosinophils. The profound synergistic effect of IL-3 and TNF on MMP-9 gene expression is sustained for a minimum of 30 h and is due at least in part to increased stabilization of MMP-9 mRNA. We also established that IL-3/TNF-induced MMP-9 requires NF-κB and the MAP kinase pathways involving ERK1/2 and p38 but not JNK. Thus, the mechanisms regulating IL-3/TNF-induced MMP-9 synthesis by human eosinophils are likely controlled by complex interaction(s) of these signaling events that lead to stabilization of MMP-9 mRNA and sustained release of proMMP-9.

Our observation that IL-3 acts synergistically with TNF for eosinophil MMP-9 synthesis is a unique finding that, to our knowledge, has not been described for eosinophils or other cell types. TNF is the prototypic inducer of proMMP-9 synthesis by a variety of cells [24] including monocytes, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, fibroblasts, T cells, tumor cells, and in some studies eosinophils [9,10]. While we did detect low levels of proMMP-9 in response to eosinophil stimulation with TNF alone, we did not see release of substantial amounts of either preformed [9] or newly synthesized MMP-9. In contrast, we observe a striking synergistic effect of TNF plus IL-3 that was not detected until 24 h. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that a portion of the IL-3/TNF-induced MMP-9 secreted at 72 h is from preformed stores, the synergistic accumulation of MMP-9 mRNA for at least 30 h and decreased decay of MMP-9 mRNA are consistent with de novo synthesis of MMP-9.

A particularly novel aspect of our work is the observation that, among the βc-family cytokines, IL-3 was the most potent inducer of MMP-9 in synergy with TNF. The apparent differential response of eosinophils to IL-3 was somewhat unexpected as all three cytokines signal through βc, and the cytokine-specific alpha chains are not thought to have signaling capability beyond JAK2/JAK1-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of βc [16]. The more robust activity of IL-3 compared to IL-5 and GM-CSF could be due to differential effects of TNF on IL-3 receptor density and/or ligand affinity. Other possible factors affecting IL-3 potency include induction and utilization of a previously unidentified alternative signaling chain, and/or a heretofore unrecognized contribution of the IL-3Rα chain to cell signaling events. An IL-3-specific signaling chain different from βc has been described in mice [25]. In addition, IL-3 was shown to signal via immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)–mediated interaction of the IL-3 βc chain and the Fc receptor common gamma chain [26]. Potential interactions between IL-3Rα and other receptors or between βc and ITAMS have not been explored in human eosinophils. The relatively weak synergistic signal provided by IL-5 may be related to specific downregulation of IL-5Rα that we have previously observed within hours of eosinophil stimulation with IL-5 [27].

The potent synergist effect of IL-3 plus TNF on eosinophil synthesis and release of proMMP-9 did not lead to detectable activation of proMMP-9. This might be expected based on observations that proMMP-9 has been detected in eosinophil lysates [14], is reportedly located in eosinophil granules [12], and is most often secreted from other cell types in a non-fully activated form [2]. However, eosinophil conversion of proMMP-9 to the active form has been reported when eosinophils were stimulated to transmigrate across artificial basement membranes [12,13,20]. It is plausible that signals induced by eosinophil chemotaxis and/or interaction with ECM result in the expression of factors that allow catalysis of the MMP-9 prodomain. Rapid release and autologous activation of pre-stored MMP-9 from eosinophils would provide an immediate supply of MMP-9 necessary for cell migration during acute inflammation. In chronic inflammatory states, IL-3 plus TNF may induce eosinophil synthesis of proMMP-9 in the tissues. MMP-9 would be available to contribute to ECM turnover and release of sequestered growth factors. MMP-9 activation may be tightly regulated in the local milieu by oxidation and/or nitrosylation [3], plasmin [20], or other metalloproteinases [2].

This is the first study evaluating MMP-9 mRNA decay in human eosinophils. No MMP-9 mRNA decay was observed when the cells were treated with the combination of IL-3 plus TNF. We demonstrated that in contrast to the relatively rapid turnover of MMP-9 mRNA in rodent cells [28,29], MMP-9 mRNA derived from human eosinophils is relatively stable. The very high stability of MMP-9 mRNA in human eosinophils compared to rodent cells was possibly due to differences in the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of MMP-9 [28,29]. Many post-transcriptionally regulated mRNA require the presence of adenosine-uridine (AU)-rich elements in their 3’ UTR [30,31]. It is important to note that rodent MMP-9 mRNA displays multiple AU-rich motifs in its 3’ UTR, but there are no AU-rich elements present in the human MMP-9 3’ UTR (NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_004994.2). Although less commonly studied, motifs other than AU-rich elements have been reported to be involved in mRNA stabilization including UC- or U-rich regions [32,33]. Intriguingly, the 3’ UTR of human MMP-9 mRNA contains five ‘CUU’ motifs (NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_004994.2). This motif has been shown to mediate stability of c-fms mRNA [34]. Further investigation is required to confirm the UTR elements and corresponding binding proteins that regulate MMP-9 mRNA decay in IL-3/TNF-stimulated eosinophils.

In discerning the individual contributions of specific signaling pathways, we observed that inhibitors that target the pathways mediated by NF-κB and the MAP kinases ERK1/2 and p38, but not those targeting JNK, diminished IL-3/TNF-induced MMP-9 mRNA and protein. The unique observation that multiple signaling pathways are required for the synergistic induction of eosinophil MMP-9 by IL-3 plus TNF is in contrast to reports on other cell types, particularly those for which MMP-9 was induced solely by TNF in an NF-κB-dependent fashion [24]. In eosinophils, rapid release of stored MMP-9 by TNF or fMLP required p38 [9,11], whereas p38 and ERK1/2 were required for 5-oxo-ETE-induced MMP-9 synthesis [11]. A number of regulatory elements have been identified in promoter/enhancer regions of the human MMP-9 gene including consensus sequences for the binding of NF-κB, SP1, TIE, AP-1, and Ets-1 and -2 transcription factors [35]. Additionally, Zhao et al. recently demonstrated transcriptional activation of MMP-9 gene expression by multiple co-activators including CBP/p300, PCAF, CARM1, and GRIP1 [36]. We suspect that regulation of MMP-9 synthesis in response to the combination of IL-3 plus TNF involves the interaction of diverse signaling pathways leading to the cooperation of multiple transcription factors and co-activators. Identification of such multiprotein/DNA-binding complexes will require extensive analysis of the MMP-9 promoter following eosinophil stimulation with IL-3/TNF.

In conclusion, we demonstrated a previously unrecognized role for βc-family cytokines, most remarkably IL-3, in eosinophil generation of exuberant amounts of MMP-9. We established that the synergistic induction of eosinophil MMP-9 by IL-3 plus TNF is due to active and prolonged synthesis that is associated with enhanced mRNA stabilization and requires the interaction of the MAP kinases and NF-kB-dependent signaling pathways. The potent synergistic effect of IL-3 plus TNF suggests that targeting these factors may be a therapeutic approach to impede MMP-9-mediated tissue injury/remodeling and inflammatory cell infiltration.

Highlights.

IL-3 in combination with TNF induces exuberant amounts of eosinophil MMP-9.

The synergistic effect of IL-3/TNF is due to MMP-9 synthesis by eosinophils.

Enhanced mRNA stabilization is associated with the synergistic induction of MMP-9.

MMP-9 synthesis requires the interaction of multiple signaling pathways.

Targeting IL-3/TNF may impede MMP-9-mediated tissue injury/remodeling.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by an institutional Specialized Center of Research grant (NIH HL56396), a Program Project grant (NIH HL088594), the University of Wisconsin General Clinical Research Center grant (NIH M01RR03186), and a University of Wisconsin Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1RR025011). The authors thank the staff of the Eosinophil Core facility for blood eosinophil purification, our research nurse coordinators for subject recruitment and screening, our technician Jami Hauer, B.S. for editorial assistance, and the Biostatistics and Medical Informatics Department for assistance with data analysis.

Abbreviations

- Ab

antibody

- βc

common beta chain

- Ct

comparative cycle threshold

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase

- GUS

glucuronidase

- MAP

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEK

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- qPCR

quantitative real time PCR

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lin Ying Liu, Email: lliu6@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Stephane Esnault, Email: sesnault@medicine.wisc.edu.

Beatriz Helena Quinchia Johnson, Email: beatrizq@msn.com.

Nizar N. Jarjour, Email: nnj@medicine.wisc.edu.

References

- 1.Vempati P, Karagiannis ED, Popel AS. A biochemical model of matrix metalloproteinase 9 activation and inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37585–37596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zitka O, Kukacka J, Krizkova S, Huska D, Adam V, Masarik M, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:3751–3768. doi: 10.2174/092986710793213724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadler-Olsen E, Fadnes B, Sylte I, Uhlin-Hansen L, Winberg JO. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase activity in health and disease. FEBS J. 2011;278:28–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly EA, Jarjour NN. Role of MMPs in asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2003;9:28–33. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan TK, Zheng G, Hsu TT, Wang Y, Lee VW, Tian X, et al. Macrophage matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in vitro in murine renal tubular cells. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1256–1270. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebrahem Q, Chaurasia SS, Vasanji A, Qi JH, Klenotic PA, Cutler A, et al. Cross-talk between vascular endothelial growth factor and matrix metalloproteinases in the induction of neovascularization in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:496–503. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.080642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin CY, Tsai PH, Kandaswami CC, Lee PP, Huang CJ, Hwang JJ, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 cooperates with transcription factor Snail to induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:815–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth N, Stadler S, Lemann M, Hosli S, Simon HU, Simon D. Distinct eosinophil cytokine expression patterns in skin diseases - the possible existence of functionally different eosinophil subpopulations. Allergy. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiehler S, Cuvelier SL, Chakrabarti S, Patel KD. p38 MAP kinase regulates rapid matrix metalloproteinase-9 release from eosinophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwingshackl A, Duszyk M, Brown N, Moqbel R. Human eosinophils release matrix metalloproteinase-9 on stimulation with TNF-alpha. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:983–989. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langlois A, Chouinard F, Flamand N, Ferland C, Rola-Pleszczynski M, Laviolette M. Crucial implication of protein kinase C (PKC)-delta, PKC-zeta, ERK-1/2, and p38 MAPK in migration of human asthmatic eosinophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:656–663. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0808492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiScipio RG, Schraufstatter IU, Sikora L, Zuraw BL, Sriramarao P. C5a mediates secretion and activation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 from human eosinophils and neutrophils. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1109–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okada S, Kita H, George TJ, Gleich GJ, Leiferman KM. Migration of eosinophils through basement membrane components in vitro: role of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:519–528. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.4.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujisawa T, Kato Y, Terada A, Iguchi K, Kamiya H. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 in peripheral blood eosinophils. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1999;120 Suppl 1:65–69. doi: 10.1159/000053598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu LY, Bates ME, Jarjour NN, Busse WW, Bertics PJ, Kelly EA. Generation of Th1 and Th2 chemokines by human eosinophils: evidence for a critical role of TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 2007;179:4840–4848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez-Moczygemba M, Huston DP. Biology of common beta receptor-signaling cytokines: IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:653–665. doi: 10.1016/S0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly EAB, Busse WW, Jarjour NN. Increased matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 in the airway following allergen challenge. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1157–1161. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9908016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esnault S, Shen ZJ, Whitesel E, Malter JS. The peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1 regulates granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor mRNA stability in T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2006;177:6999–7006. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pugin J, Widmer MC, Kossodo S, Liang CM, Preas HL, Suffredini AF. Human neutrophils secrete gelatinase B in vitro and in vivo in response to endotoxin and proinflammatory mediators. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:458–464. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.3.3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langlois A, Ferland C, Tremblay GM, Laviolette M. Montelukast regulates eosinophil protease activity through a leukotriene-independent mechanism. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Groot RP, Coffer PJ, Koenderman L. Regulation of proliferation, differentiation and survival by the IL-3/IL-5/GM-CSF receptor family. Cell Signal. 1998;10:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(98)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong CK, Zhang JP, Ip WK, Lam CW. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-kappaB in tumour necrosis factor-induced eotaxin release of human eosinophils. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;128:483–489. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Y, Bertics PJ. Chemoattractant-induced signaling via the Ras-ERK and PI3K-Akt networks, along with leukotriene C4 release, is dependent on the tyrosine kinase Lyn in IL-5- and IL-3-primed human blood eosinophils. J Immunol. 2011;186:516–526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van den Steen PE, Dubois B, Nelissen I, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Opdenakker G. Biochemistry and molecular biology of gelatinase B or matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;37:375–536. doi: 10.1080/10409230290771546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoh N, Yonehara S, Schreurs J, Gorman DM, Maruyama K, Ishii A, et al. Cloning of an interleukin-3 receptor gene: a member of a distinct receptor gene family. Science. 1990;247:324–327. doi: 10.1126/science.2404337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hida S, Yamasaki S, Sakamoto Y, Takamoto M, Obata K, Takai T, et al. Fc receptor gamma-chain, a constitutive component of the IL-3 receptor, is required for IL-3-induced IL-4 production in basophils. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:214–222. doi: 10.1038/ni.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu LY, Sedgwick JB, Bates ME, Vrtis RF, Gern JE, Kita H, et al. Decreased expression of membrane IL-5Rα on human eosinophils: II. IL-5 down-modulates its receptor via a proteinase-mediated process. J Immunol. 2002;169:6459–6466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akool e, Kleinert H, Hamada FM, Abdelwahab MH, Forstermann U, Pfeilschifter J, et al. Nitric oxide increases the decay of matrix metalloproteinase 9 mRNA by inhibiting the expression of mRNA-stabilizing factor HuR. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4901–4916. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4901-4916.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eberhardt W, Akool e, Rebhan J, Frank S, Beck KF, Franzen R, et al. Inhibition of cytokine-induced matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha agonists is indirect and due to a NO-mediated reduction of mRNA stability. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33518–33528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw G, Kamen R. A conserved AU sequence from the 3′ untranslated region of GM-CSF mRNA mediates selective mRNA degradation. Cell. 1986;46:659–667. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Esnault S, Malter JS. Primary peripheral blood eosinophils rapidly degrade transfected granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor mRNA. J Immunol. 1999;163:5228–5234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wein G, Rossler M, Klug R, Herget T. The 3′-UTR of the mRNA coding for the major protein kinase C substrate MARCKS contains a novel CU-rich element interacting with the mRNA stabilizing factors HuD and HuR. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:350–365. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez de Silanes I, Zhan M, Lal A, Yang X, Gorospe M. Identification of a target RNA motif for RNA-binding protein HuR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2987–2992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woo HH, Zhou Y, Yi X, David CL, Zheng W, Gilmore-Hebert M, et al. Regulation of non-AU-rich element containing c-fms proto-oncogene expression by HuR in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28:1176–1186. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan C, Boyd DD. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:19–26. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao X, Benveniste EN. Transcriptional activation of human matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene expression by multiple co-activators. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]