Abstract

Biomarkers are an important aspect of research linking psychosocial stress and health. This paper aims to characterize the biological pathways that may mediate the relationship between socioeconomic position (SEP) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) and address opportunities for further research within the Panel Study for Income Dynamics (PSID), with a focus on psychosocial stressors related to SEP. We review the literature on CVD biomarkers, including adhesion and proinflammatory molecules (IL-6, other cytokines, C-reactive proteins, fibrinogen, etc.) and microbial pathogens. The impact of socioeconomic determinants and related psychosocial stressors on CVD biomarkers mediated by behavioral and central nervous system pathways are described. We also address measurement and feasibility issues including: specimen collection methods, processing and storage procedures, laboratory error, and within-person variability. In conclusion, we suggest that PSID consider adding important assessments of specific CVD biomarkers and mediating behavioral measures, health, and medications that will ultimately address many of the gaps in the literature regarding the relationship between socioeconomic position and cardiovascular health.

Introduction

Many have argued that joint biological and social data are needed for proper specification of the linkages among social environment, psychosocial stressors, and physical health.(Seeman and Crimmins 2001; Kristenson, Eriksen et al. 2004) Identification and measurement of biomarkers has become a key component of much research in this field, particularly important to research linking psychosocial stressors and health. Within this context, this paper aims to characterize the biological pathways that may mediate the relationship between socioeconomic position and cardiovascular health, and address opportunities for further research within the Panel Study for Income Dynamics (PSID), with a particular focus on psychosocial stressors related to SEP. We focus on psychosocial stressors related to socioeconomic position because that is the greatest area of strength for the PSID. We concentrate our analysis on cardiovascular disease (CVD) in light of its significant impact on public health worldwide. In terms of biomarkers, we focus primarily on those that may link exposure to low socioeconomic position (SEP) and psychological stressors to cardiovascular health (i.e. immunological and thrombolytic rather than conventional biomarkers such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes). We discuss issues related to the definition and measurement of stress and what is known regarding the pathophysiological relationships among these biomarkers. This allows for a more informed discussion of the utility of these markers for testing hypotheses of the relationship between stress and physical health. Identification of stress-mediated biological pathways may be important in targeting interventions and designing policies for improving cardiovascular health, but we emphasize that reducing sources of stress is probably more important. The overall purpose of this paper is to ensure that hypothesized pathways are specified and properly supported by our current understanding of psychosocial and biological mechanisms, that measurement error is minimal, and that the right samples at the right time are collected and rigorously processed. Although there are many crucial ethical concerns regarding collection of biomarkers, they are substantive enough to warrant a separate, thorough examination and will not be discussed here.

I. Defining stress

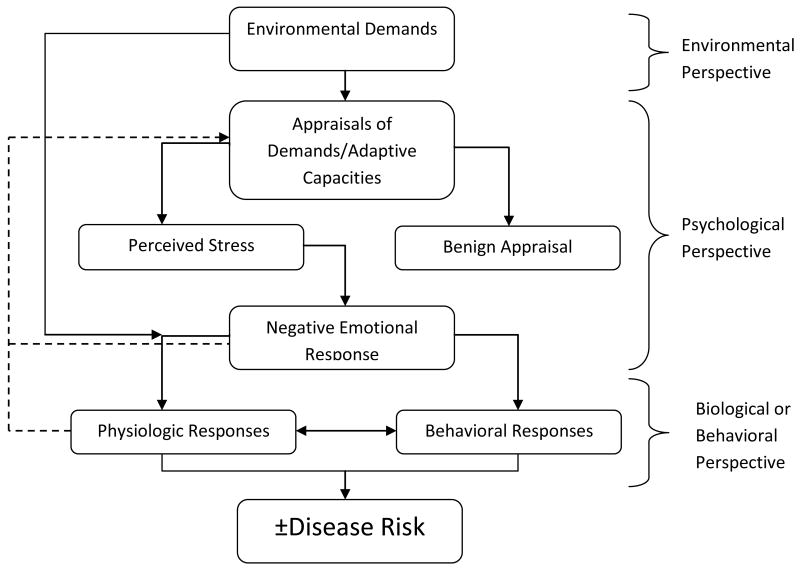

The study of stress and physical health must by necessity begin with a discussion of the various definitions of “stress.” The varied uses of the terms are reminiscent of both a speech by Humpty Dumpty in Through the Looking Glass and the story of the blind men and the elephant. ‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said, in a rather scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean, neither more nor less.’ and the blind men who, as you recall, have very different views of exactly what this thing called an “elephant” is. Generally speaking, there are three main ways in which the term stress is used: as a marker of events that are presumed to be stressful (stressors) and that require action or adaptation, as a marker of processes of appraisal of such events often with an affective component, and as a physiological response to all of the above. Figure 1 (Adapted from (Cohen, Kessler et al. 1995)) illustrates the interconnections between these three views of stress.

Fig. 1.

Three Views of Stress (Cohen, Kessler et al. 1995)

There are a number of issues that follow from the conceptualization shown in Figure 1 and that are relevant to the study of stress and health in the PSID. Stressors, and the consequent processes that follow, can be characterized as either acute or chronic. At first glance this seems a straightforward characterization, yet there is no clear demarcation between what constitutes an acute or chronic stressor. In addition, acute stressors can be one time or recurrent events, with the latter sometimes indistinguishable from chronic events.

Since the work of Selye (and before), it has been observed that the events that follow a stressor are dynamic and potentially involve cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physiological processes that are interconnected and occur over time. While appraisal processes are emphasized in the psychological literature, the measurement of such processes, as opposed to their emotional sequelae, is difficult and without any gold standard.(Cohen, Kessler et al. 1995)

Stressors may have direct physiological, and perhaps behavioral, effects without the appraisal process and its affective component. Environmental stressors, for example, can have direct physiological consequences. Appraisal processes can be shaped by many factors including the current emotional state of the individual and the meaning they attach to stressors. The former can be assessed with a variety of instruments the latter is more difficult to assess. (Cohen, Kessler et al. 1995)

Understanding the links between stress and health outcomes requires a clear understanding of the nature of each endpoint. Some outcomes such as self-rated health or depressive symptoms may be sensitive to short term variations in stress.(Cohen, Kessler et al. 1995) However, for most chronic diseases the impact of stress must be understood within a framework that includes the factors associated with the initiation of the underlying physiologic processes, progression to clinically observable disease, self-treatment, access to and quality of care, transition to complications, etc., all of which generally occur over long periods of time.

PSID, SEP and pathways to health

The PSID has extensive information on economic status and household composition/changes. It currently collects very little data that is useful in characterizing stress appraisal processes or emotional states. While the PSID might be able to implement collection of data on emotional well-being, it is questionable whether it could do so comprehensively enough to add to the existing literature on stress and health. The PSID is, however, extremely well-positioned to look at the impact of SEP and family composition, and changes/trajectories of both, on health outcomes. For these reasons, we believe that focusing on psychosocial stressors (stressful life events) related to specific measurements of SEP such as individual and household economic situation and changes in family composition provides the greatest potential for expansion in the PSID. While there are many other stress-related areas of interest that would be useful to pursue, that is not where the comparative advantage of the PSID lies.

Importantly, the PSID has considerable strength in being able to distinguish between acute stressors such as economic shocks and chronic stressors associated with mid- and long-term economic position. The long time series of carefully collected socioeconomic data puts the PSID in a unique position to examine the relationship between acute and chronic economic stressors, health outcomes, and the intervening biological pathways and their biomarkers. Many of the socioeconomic variables that have been examined in relation to biomarkers of CVD in other populations are available in the PSID (See Table 1). More recently, studies have begun to examine how socioeconomic trajectories within or across generations influence hemostatic and immune biomarkers of CVD but the data is limited. For example, lower SEP over the life course was associated with increased fibrinogen in a large study of Finnish middle age men.(Wilson, Kaplan et al. 1993) More recently, Tabassum et al. showed that cumulative low social class from birth to midlife was associated with increased levels of fibrinogen and C-reactive protein as an adult.(Tabassum, Kumari et al. 2008) The design of the PSID, with multiple survey follow-up and economic measures, represents an important resource for identifying how well-measured temporal changes in socioeconomic determinants influence these and other biomarkers of CVD.

Table 1. SEP and Biomarkers related to CVD.

Table 1 Notes: CRP-C-reactive protein,t-PA-tissue plasminogen activator antigen, immunoglobulin E,, vWF-von Willebrand factor, WBC-white blood cells, HbA1c-glycosylated hemoglobin, IgE-total immunoglobulin E, IL-1R-interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, IL-6-interleukin-6, TNF-α-tumor necrosis factor-α, APC-activated protein C, ET-1-endothelin-1, PHA-phytohemagglutinin, MCP-1-monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, sICAM-1 -soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1, IFN-γ-interferon-γ. Results shown for any significant results - no distinctions were made for race , gender or other stratification variables. Fully adjusted models were used when available, unadjusted shown otherwise. For a comprehensive review of SEP and CRP, the reader is referred to Nazmi and Victora.(Nazmi and Victora 2007). *Measured in children or teens.

II. Cardiovascular Biomarkers

CVD is a wide-ranging class of diseases, including coronary heart disease and atherosclerosis as well as less common manifestations such as endocarditis. Despite the large number of conditions that fall under this classification, all involve the cardiovascular system (i.e. heart and/or blood vessels) and have underlying similarities in causes and/or mechanisms. CVD is the leading cause of death in the US.(Anderson and Smith 2005) By the year 2020, CVD is expected to be the most prevalent, disabling disease across the globe.(Lopez and Murray 1998) Given the extent of this disease and the breadth of information available on its biology, we have chosen CVD as our primary focus in demonstrating the link between socioeconomic position and physical health.

Cardiovascular disease is considered an immune-mediated condition with numerous hormonal, immunological, and metabolic alterations that influence the disease process. A main mechanistic feature of atherosclerosis is the deposition of lipids and other materials in the arterial wall leading to plaque formation. Although the process is generally silent, it manifests clinically at plaque rupture and ensuing thrombosis, aneurysm, arterial stiffness and reduced elasticity of blood vessels.(Dotsenko, Chackathayil et al. 2008) Dysfunction of the endothelium leads to immunological alterations including activation, adhesion, and aggregation of platelets to areas of damage.(Dotsenko, Chackathayil et al. 2008) Platelets, in turn, release granulocytic contents, express cellular surface receptors, and produce procoagulant molecules. At the site of damage, cell adhesion molecules (e.g. ICAM, VCAM, ECAM, etc) and selectins (e.g. E, P, etc.) are produced.(Tesfamariam and DeFelice 2007; Dotsenko, Chackathayil et al. 2008) These adhesion molecules modulate circulating monocyte attraction where they become macrophages. A review by Dostenko et al. indicates that cholesterol is oxidized in the subendothelium. In its oxidized state, cholesterol becomes toxic and is therefore phagocytized by macrophages in the vessel wall (Dotsenko, Chackathayil et al. 2008). This process induces an inflammatory response through cytokines, including TNF-alpha and IL-1. Chemokines and growth factors are also involved, including soluble CD40 ligand and platelet derived growth factor among others. The immune response results in continued activation and recruitment of macrophages and inflammatory proteins to the damage site. Importantly, some ruptured plaques never lead to thrombosis. Thus, other unspecified immune mediated factors may ultimately be found to modulate the occurrence of clinical cardiovascular events(Dotsenko, Chackathayil et al. 2008).

Several proinflammatory molecules, including cytokines (e.g. IL-6, IL-1B, IFN-gamma, TNP-alpha, etc), chemokines, and acute phase proteins have been implicated in CVD.(Kuller, Tracy et al. 1996; Ridker, Cushman et al. 1997; Danesh, Collins et al. 1998; Hak, Stehouwer et al. 1999; Koenig, Sund et al. 1999; Ross 1999; Zhang, Cliff et al. 1999; Danesh, Whincup et al. 2000; Ford and Giles 2000; Rader 2000; Ridker, Hennekens et al. 2000; Ridker, Rifai et al. 2000; Torzewski, Rist et al. 2000; Libby 2001) Cytokines and acute phase proteins, act as regulators of the immunological response to infection, injury and repair.(Kuby 1997) There are multiple functional characteristics of cytokines, including pleiotropy, redundancy, synergy and/or antagonism and the relationship among these markers is complex.(Kuby 1997) Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is generally considered a pro-inflammatory cytokine and plays a direct role in the initiation of other inflammatory factors' synthesis, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen. Both Interleukin-6 and CRP have been shown to predict cardiovascular disease among generally healthy individuals in population-based studies.(Wilson 2004) CRP is synthesized in the liver as an immunological endpoint in the classical complement pathway for responding to infection and injury. CRP primarily appears to take part in the earlier stages of atherosclerosis in the inflammatory response of the vascular epithelium. (Vallance, Collier et al. 1997; Fichtlscherer, Rosenberger et al. 2000) It has also been shown to amplify inflammation by inducing monocyte activation (Cermak, Key et al. 1993; Torzewski, Rist et al. 2000) and leukocyte recruitment to the endothelial layer via synthesis of adhesion molecules.(Pasceri, Willerson et al. 2000) Furthermore, CRP is involved in the formation of fatty streaks and plaque in the arterial wall.(Ross 1999; Zhang, Cliff et al. 1999; Torzewski, Rist et al. 2000) Nevertheless, there is still debate as to the specific role that CRP plays in CVD pathophysiology. It is possible that higher CRP may be a marker for instability and rupture of preexisting atherosclerotic plaques rather than an inducer of pathology.(Casas, Shah et al. 2008) Another inflammatory mediator is Serum Amyloid A (SAA) an apolipoprotein molecule. Like CRP, SAA is an important component of the acute phase inflammatory response and is produced in the liver upon infection, injury and immune insults. In regards to CVD pathways, SAA is secreted from High Density Lipoproteins (HDL), replaces apolipoprotein A on cholesterol particles, and modifies cholesterol delivery to cells.(Johnson, Kip et al. 2004) SAA has been shown to be an independent predictor of future cardiovascular risk among diseased and non-diseased subjects, but results are mixed.(Ridker, Hennekens et al. 2000; Johnson, Kip et al. 2004; Wilson 2004)

Fibrinogen is considered an inflammatory marker of thrombogenesis. It acts as a signal for expression of cytokines and stimulates smooth muscle proliferation/migration and platelet aggregation.(Folsom, Wu et al. 1997) Fibrinogen contributes to thickness and clotting of blood and has been recognized as an essential molecule in thrombolytic events triggering myocardial infarction and stroke.(Wilhelmsen, Svardsudd et al. 1984) It has also been identified as a factor involved in plaque formation.(Folsom, Wu et al. 1997) Other important blood markers that are generally not considered under the immune and inflammatory category, include oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL), apolipoprotein A and B, and reactive oxygen species. LDL is a major cholesterol carrier in human plasma and like CRP, it is produced in the liver. ApoA on the other hand, is present on HDL and has anti-atherogenic properties, including removal of arterial cholesterol.(Chiesa and Sirtori 2003) Cellular exposure to oxidative stress causes oxidation of LDL into OxLDL.(Itabe 2003; Itabe 2008) OxLDL is a well studied risk factor for CVD and has been identified in atherosclerotic plaques.(Holvoet, Lee et al. 2008) After stimulation by OxLDL, endothelial cells in the cardiovasculature begin to produce chemoattractants which guide monocytes to the intima. Macrophages then bind to and uptake OxLDL. Upon uptake macrophages develop into foam cells, catalyzing the process of intima thickening.(Itabe 2003) Reactive oxygen species can be organic or inorganic molecules, including oxygen ions, peroxides, and free radicals, such as superoxide, and their production from endothelial cells are induced by cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL-1 and IL-6.(Tolando, Jovanovic et al. 2000) To our knowledge, the relationship between SEP and markers such as apoA, B, oxLDL, and reactive oxygen species has not been well explored.

In addition to the markers mentioned above, several microbial pathogens have also been linked to cardiovascular disease in animal models and human epidemiological studies.(Zhu, Quyyumi et al. 2000; Epstein 2002) The implicated infectious agents include cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) and Chlamydia pneumoniae (C. pneumoniae), but relationships have not always been consistent.(Zhu, Quyyumi et al. 2000; Epstein 2002) Animal models have shown that persistent pathogens may cause direct or secondary pathological damage to cardiovascular tissue by acting as pro-inflammatory stimuli resulting in endothelial tissue damage.(Muhlestein, Anderson et al. 1998; Takaoka, Campbell et al. 2008) Although conclusions regarding the association between individual pathogens and cardiovascular disease in human populations have been conflicting, recent studies have more consistently identified associations between multiple persistent pathogens and cardiovascular disease processes.(Zhu, Nieto et al. 2001; Georges, Rupprecht et al. 2003) The hypothesized mechanisms by which infection with multiple pathogens may contribute to cardiovascular disease include induction of a systemic pro-inflammatory cytokines and CRP or potential direct pathophysiological damage to cardiovascular tissue.(Epstein 2002)

Many of the biomarkers that are involved in or produced by atherosclerotic processes are listed in Table 2. We also present a description of the biological materials and methods that are required for their collection and laboratory analysis. In terms of intervention targets, the most useful biomarkers are those that occur at the earliest periods during the development of cardiovascular disease. Mechanistic research that maps out the temporal aspects and pathways involved in these physiological analytes is needed. For example, glucocorticoids stimulate production of IL-6 and IL-6 in turn induces CRP synthesis in the liver(Pradhan, Manson et al. 2001). Therefore, when interpreting the relationship between SEP and biomarkers it is also important to consider how the biomarkers relate to one another. Such endeavors would help better specify the kinds of pathways that are most pertinent to a particular socioeconomic measure and physiological response related to cardiovascular disease manifestation, and clarify the reasons for observed association with increased CVD risk.

Table 2.

Atherosclerosis (plaque formation and progression)

| Process | Biomarker | Material tested | How Sample Analyzed | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation | Oxidized LDL-C | Serum | ELISA | (Miller, Freedland et al. 2005; Huang, Mai et al. 2008) |

|

| ||||

| apoA, apoB | Serum | ELISA, immunoturbidimetry, nephelometry | (Cerne, Ledinski et al. 2000; Ashavaid, Kondkar et al. 2005) | |

|

| ||||

| CRP* | Serum | ELISA, immunoturbidimetry, nephelometry | (Sisman, Kume et al. 2007; Gori, Cesari et al. 2008; Wettero, Nilsson et al. 2008) | |

|

| ||||

| Cytokines (IL-6*, IL-1B, -10, TNFa) | Serum, PBMCs | ELISA, flow cytometry, | (Napoleao, Santos et al. 2007; Profumo, Buttari et al. 2008; Souza, Oliveira et al. 2008) | |

|

| ||||

| sCD40L | Serum | ELISA | (Napoleao, Santos et al. 2007) | |

|

| ||||

| Chemokines (MCP-1, IL-8) and their receptors | Serum | ELISA, lateral flow immunoassay | (Kim, Park et al. 2006) | |

|

| ||||

| Serum amyloid A | Serum | Nephelometry, ELISA | (Rifai, Joubran et al. 1999; Johnson, Kip et al. 2004) | |

|

| ||||

| PECAM-1 | Serum | flow cytometry | (Bernal-Mizrachi, Jy et al. 2003; Pirro, Schillaci et al. 2006) | |

|

| ||||

| Adiponectin | Serum | ELISA, radioimmunoassay | (Cheng, Hashmi et al. 2008) | |

|

| ||||

| Thrombogenesis/Lysis | Cell adhesion molecules (E-selectin, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, P-selectin)( L-selectins) | Leukocytes, serum | fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, ELISA | (Glowinska, Urban et al. 2005; Napoleao, Santos et al. 2007; O'Brien, Ling et al. 2008) |

|

| ||||

| Fibrinogen | Serum (plasma) | Fibrinogen Analysis (Coagulation analysis) | (Green, Foiles et al. 2008) | |

|

| ||||

| sCD40L | Serum | ELISA | (Napoleao, Santos et al. 2007) | |

|

| ||||

| Lp(a) | Serum (plasma) | ELISA | (Ranga, Kalra et al. 2007) | |

|

| ||||

| Endothelial dysfunction/damage | LDL-C, oxidized LDL-C | Serum | Homogeneous LDL-C assay, ELISA | (Nauck, Graziani et al. 2000; Miller, Freedland et al. 2005; Koba, Hirano et al. 2006) |

|

| ||||

| Cell adhesion molecules | Leukocytes, serum | fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, ELISA | (Glowinska, Urban et al. 2005; Napoleao, Santos et al. 2007; O'Brien, Ling et al. 2008) | |

|

| ||||

| ROS | Monocytes and Granulocytes | Flow cytometry, chemiluminescence | (Eid, Lyberg et al. 2002) | |

|

| ||||

| Microbe antigens: Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)*, Cytalomegalovirus (CMV)* | Serum | Microimmunofloursescence, ELISA | (Schumacher, Seljeflot et al. 2005) | |

|

| ||||

| Inflammatory cytokines (IL-6*, IL-18, CRP*) | Serum | ELISA, flow cytometry | (Souza, Oliveira et al. 2008) | |

|

| ||||

| Oxidative Stress | Oxidized LDL-C | Serum | ELISA | (Miller, Freedland et al. 2005) |

|

| ||||

| ROS | Monocytes and Granulocytes | Flow cytometry, chemiluminescence | (Eid, Lyberg et al. 2002) | |

Table 2 Notes: ROS – reactive oxygen species; ICAM-1 – intercellular adhesion molecule 1; VCAM – vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; sCD40L – soluble CD40 ligand; TNF-α – tumor necrosis factor α; IL-6, -8, -10, -interleukin -6, -8, -10 ; MCP-1 – monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; PECAM – platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule; LDL-C – low density lipoprotein cholesterol; CRP – C-reactive protein; TGF- β – transforming growth factor – β;lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 – Lp-PLA2; t-PA – tissue type plasminogen activator; PAI-1 – plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; Lp(a) – lipoprotein (a).

Can be assessed by blood spot techniques

The majority of the biomarkers of atherosclerosis shown in Table 2 can be assayed in serum and therefore require a venipuncture. Some, such as CRP and antibodies to infection (HSV and CMV), now have standardized methodologies for assessment in minimally invasive blood spots. (McDade, Williams et al. 2007) Other markers, however, require whole blood (eg. IL-6, IL-1a, TNF-α). For many of the markers laboratory assays are standardized, relatively simple, low cost, and commercially available. It is important to note that most of the assay techniques include ELISA, which is a simple and standard method for analyzing blood specimens and spots. Further discussion regarding sample collection and analysis are found in section IV.

III. Pathways between SEP and biomarkers of CVD

Kaplan and Keil (Kaplan and Keil 1993) summarized the available data on the association between various measures of socioeconomic position and a variety of CVD endpoints. In addition to strong relationships, they found that most risk factors for CVD were inversely related to income, education, and other markers of SEP. Since then the list of SEP measures that are associated with increased CVD risk has grown. For example, investigators have observed that childhood socioeconomic circumstances are related to adult CVD (Galobardes, Smith et al. 2006), as is socioeconomic disadvantage over the life course.(Wamala, Lynch et al. 2001) In addition, we now know that job loss, a major economic shock, is associated with increased CVD risk (Gallo, Teng et al. 2006), as is living in a poor neighborhood.(Diez Roux, Merkin et al. 2001)

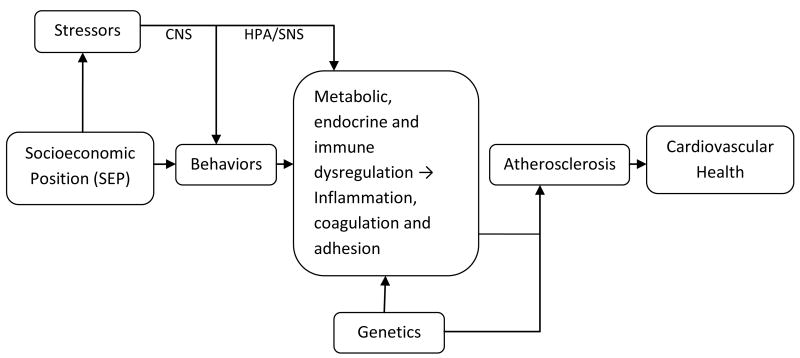

Socioeconomic position may influence cardiovascular health through several pathways, including behaviors and psychosocial stress levels, both of which may influence biological markers of inflammation, coagulation, and adhesion. Alterations in these biomarkers may be a consequence of hormonal and metabolic dysregulation resulting from changes in stress-related behaviors or direct effects of stress exposures on the central nervous system, HPA and SNS activity (see Figure 2). There are also other important biological pathways between SEP and CVD not shown in Figure 2, including increases in cholesterol and hypertension. Comprehensive reviews on the relationship between SEP and hypertension have been published previously.(Pickering 1999; Grotto, Huerta et al. 2008)

Fig. 2.

Pathways between SEP, biomarkers, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular health CNS=Central Nervous System, HPA=Hypothalmic-pituitary-adrenal axis, SNS=Sympathetic Nervous System

Socioeconomic Position and Biomarkers Related to CVD

There is accumulating evidence supporting a relationship between socioeconomic position and inflammatory, coagulation, adhesion, and other immune biomarkers of CVD (see Table 2). Chronic and systemic inflammatory upregulation has been shown to play a central role in atherosclerosis. There is strong evidence that individuals living in poverty have higher CRP levels, even after controlling for numerous potential confounding factors, such as age and gender and curent health status.(Alley, Seeman et al. 2005; Nazmi and Victora 2007) A comprehensive review of 32 studies examining the relationship between SEP and CRP reported that the majority identified an inverse association between CRP levels and SEP.(Nazmi and Victora 2007) Several of the studies reviewed were population-based studies and were mainly conducted in high-income countries. Of note, there was great variability in covariate adjustment across the studies.(Nazmi and Victora 2007) Indeed, some of the studies did not adjust for other facytors at all and several adjusted for potential mediators such as BMI and smoking.(Nazmi and Victora 2007) Even after adjustment for mediators (potentially over-adjustring), the relationship between SEP and CRP remained in a number studies, suggesting that other pathways, possibly through psychosocial stress effects on immune function, may influence CRP levels.

Elevated levels of inflammatory markers have been associated with low SEP at multiple life stages, suggesting that life course SEP exposures may lead to chronic long-term changes in inflammatory biomarker levels. For example, lifetime exposure to low education and social class has been shown to be significantly associated with elevated levels of CRP and higher white blood cell counts.(Pollitt, Kaufman et al. 2008) More recently, a study by Janicki-Deverts et al. showed that having a history of unemployment at year 10 of their study was associated with higher C-Reactive Protein (CRP) levels at year 15, adjusting for age, race, BMI, year 7 CRP levels, year 15 unemployment, and average income across years 10–15.(Janicki-Deverts, Cohen et al. 2008) A few studies suggest that low adult SEP is more strongly correlated to high CRP than childhood SEP.(Pollitt, Kaufman et al. 2007; Pollitt, Kaufman et al. 2008) Elevated CRP has been linked to several SEP markers, including lower adult occupational status, lower educational attainment, receipt of welfare )Kaplan et al. AJPH), and lower income levels (Table 1).(Loucks, Sullivan et al. 2006; Muennig, Sohler et al. 2007; Nazmi and Victora 2007; Pollitt, Kaufman et al. 2007; Tabassum, Kumari et al. 2008) Occupation and education levels have also been associated with a number of other inflammatory biomarkers, including cytokines such as TNF-a, IL-1Ra, and IL-6.(Steptoe, Owen et al. 2002; Ranjit, Diez-Roux et al. 2007) However, the behavioral, stress-related and biological mechanisms by which SEP may lead to increases in CRP and cytokines has been less well studied. Therefore, the likely contribution of behaviors, diet, obesity, or stress as mediating factors is still unclear. Moreover, the behaviors and health factors accounted for in many of the available studies shown in Table 1 vary widely. In addition, few have controlled for factors that could alter immunity and may be differential by SEP, such as medication use and autoimmune conditions.

Several studies also support a relationship between SEP, fibrinogen and adhesion molecules. One of the first studies to examine the relationship between life course SEP and fibrinogen was conducted in Finland among middle age men.(Wilson, Kaplan et al. 1993) After adjusting for alcohol consumption, body mass index, physical fitness, smoking, coffee consumption, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood leukocyte count, and prevalent disease (at least one sign of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, or previous stroke), there was a persistent association between low education, low current income, or lifetime occupation and increased fibrinogen.(Wilson, Kaplan et al. 1993) Given that many of these factors are mediators, these data suggest that life course SEP may influence fibrinogen through other pathways. Analysis of the joint effect of childhood and adult socioeconomic status indicated that those who were economically disadvantaged at both times had the highest fibrinogen levels, but the fibrinogen levels of those who were not poor as adults had no variation by childhood socioeconomic status.(Wilson, Kaplan et al. 1993) In a more recent study of more than 10,000 men aged 50-59 years who were initially free of CHD, low SEP was associated with significantly higher fibrinogen levels (Yarnell, Yu et al. 2005); this relationship held whether SEP was measured in terms of years of education or employment level. Similarly, a study of 639 men ages 50 and older showed that, among non-smokers, there was a significant, inverse relationship between occupational class and fibrinogen level, with those in the highest class showing the lowest levels.(Rosengren, Wilhelmsen et al. 1990) In addition to SEP-based studies, some studies have documented a relationship between stress and fibrinogen levels, with increasing job stress levels associated with increasing fibrinogen concentrations in men.(Markowe, Marmot et al. 1985; Steptoe, Kunz-Ebrecht et al. 2003)

In contrast to the results available for adults, data collected from children and adolescents shows no association between SEP and fibrinogen levels. In one study of children ages 10-11 years in the U.K., fibrinogen was shown to be unrelated to the participants' town or to the occupational social class of the participants' parents.(Cook, Whincup et al. 1999) Similarly, lower parental education was not associated with higher fibrinogen levels when measured among 887 adolescents in the U.S.(Goodman, McEwen et al. 2005) These data suggest that differences in fibrinogen by SEP may be difficult to detect in younger cohorts or that these disparities do not manifest themselves until older ages.

In addition to inflammatory and thrombolytic markers discussed above, recent data suggest that there are strong socioeconomic differentials in pathogens that have been implicated in cardiovascular disease. (Dowd, Haan et al. 2008; Dowd, Aiello et al. 2009; Simanek In press; Zajacova, Dowd et al. In press; Aiello Under review) The primary hypothesized mechanism is that the implicated pathogens may also influence inflammatory biomarkers of CVD. Some studies have investigated socioeconomic differences in infections with individual pathogens that have been implicated in cardiovascular disease (Xu, Schillinger et al. 2002; Schillinger, Xu et al. 2004; Staras, Dollard et al. 2006; Dowd, Aiello et al. 2009), but fewer studies have examined differences in cumulative pathogen burden by SEP. Recent work has shown that increased pathogen burden, including HSV-1, CMV, Hepatitis B virus, and H. pylori, was significantly associated with lower income and education in a US nationally representative study.(Zajacova, Dowd et al. In press) An earlier study from the UK reported that employment grade was related to pathogen burden (sum of seropositive status to CMV, HSV-1 and C. pneumoniae.).(Steptoe, Shamaei-Tousi et al. 2007) Examining the role of psychosocial stressors as a mediator of the impact of SEP on infection is also important, given the observed associations of chronic stressors with susceptibility to novel infections and reactivation of persistent pathogens such as CMV and HSV.(Glaser, Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 1985; Cohen, Frank et al. 1998; Stowe, Mehta et al. 2001) More recently, Simanek, Dowd and Aiello, reported that CMV infection partially mediates the relationship between SEP and cardiovascular disease history in a large US representative population.(Simanek In press) Together, these studies suggest that persistent pathogens may reside on the pathway between SEP and cardiovascular health.

Psychosocial stress and biomarkers of CVD

Various measures of psychosocial stress, often associated with lower SEP, have been shown to be significantly correlated with increases in systemic inflammatory markers associated with cardiovascular disease, including C-reactive protein (CRP), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF- α).(Appels, Bar et al. 2000; Glaser, Robles et al. 2003; Kiecolt-Glaser, Preacher et al. 2003; Graham, Robles et al. 2005; Kiecolt-Glaser, Loving et al. 2005; Miller, Freedland et al. 2005; Miller, Freedland et al. 2005) In a population of elderly individuals, chronic stress related to caregiving for a spouse with dementia, was significantly predictive of a four times faster rate of IL-6 increase over a six year period compared to non-caregivers.(Kiecolt-Glaser, Preacher et al. 2003) Other studies have demonstrated a relationship between chronic stress, glucocorticoid production, cytokines, and various measures of cellular immune function.(Herbert and Cohen 1993; Pariante, Carpiniello et al. 1997; Vedhara, Cox et al. 1999) The reported associations between various psychosocial stressors and inflammatory biomarkers of CVD have not always been consistent. It is likely that the relationship varies with types of stressors (e.g. acute vs. chronic) and across demographic characteristics. Moreover, measurement and adjustment for potential confounders and mediators often vary across studies making it difficult to synthesize findings.(Di Napoli, Schwaninger et al. 2005)

Central nervous system (CNS)

Socioeconomic conditions contribute to levels of chronic and acute stressors. Factors that are likely to increase psychosocial stress levels include exposure to adverse social environments, discrimination and structural disadvantage, such as crowding, neighborhood crime, pollution, and exposure to institutionalized racism.(Baum, Garofalo et al. 1999) The notion that exposure to psychosocial stressors is linked with morbidity and mortality has been recognized throughout history.(Sternberg 1997) There is considerable evidence showing a link between stressors and psychopathology, hormonal alterations and immunological functioning.(Herbert and Cohen 1993; Herbert and Cohen 1993) Pathways that may link psychosocial stressors and alterations in hormonal biomarkers include activation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) via CNS responses to stress exposures.(Herbert and Cohen 1993; Herbert and Cohen 1993) Activation of HPA and SNS modulates the release of hormonal biomarkers such as cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, which are important mediators of an immune response.(Herbert and Cohen 1993; Herbert and Cohen 1993) Sustained cortisol response can lead to increases in risk factors for CVD such as, insulin resistance, obesity, increased lipid accumulation, coagulation and hypertension.(Girod and Brotman 2004) Changes in levels of cortisol may also directly influence immune function leading to alterations in cellular processes and the regulation of cytokine production, including IL-6, TNF-α and IFN-γ, which have important mediating effects on cardiovascular health.(Vedhara, Fox et al. 1999; Glaser and Kiecolt-Glaser 2005; Soderberg-Naucler 2006) The biological relationship between CNS and the immune system most likely consists of a bidirectional feedback mechanism producing interactions between endocrine hormones, cytokines and other immunotransmitters.(Glaser and Kiecolt-Glaser 2005) Although chronically elevated cortisol is one commonly suggested mechanism through which low SEP may affect health, the findings regarding this relationship have been inconsistent.(Brandtstadter, Baltes-Gotz et al. 1991; Owen, Poulton et al. 2003; Strike and Steptoe 2004; Ranjit, Young et al. 2005; Dowd and Goldman 2006; Doyle, Gentile et al. 2006) A major hurdle associated with cortisol assessment in population-based samples is measurement error. Human cortisol follows a circadian rhythm resulting in substantial within-individual variations, requiring multiple sample compliance throughout the day for valid assessments.(Young, Abelson et al. 2004; Adam, Hawkley et al. 2006; Levine, Zagoory-Sharon et al. 2007) In addition to cortisol, researchers have begun to explore assessment of immune and inflammatory biomarkers that may lie within the pathway between SEP and cardiovascular disease (See Table 1).

Behavioral Pathways

SEP has been shown to be associated with lower levels of physical activity, poorer diets, alcohol use, and obesity.(Baltrus, Lynch et al. 2005) In turn, these behavioral factors may lead to increased risk for metabolic conditions, poorer immune functioning and higher levels of peripheral inflammatory markers related to cardiovascular disease, including CRP, IL-6 and others. Studies have also shown that the relationship between SEP and behaviors may be mediated by exposure to psychosocial stressors. Indeed, individuals exposed to psychosocial stressors are also more likely to demonstrate behavioral risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including smoking, lack of exercise, poor diets, obesity, and alcohol abuse.(Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire et al. 2002; Cohen 2005) For example, adverse social environment, low educational level and unemployment are significantly associated with adult alcohol abuse and smoking.(Kestila, Koskinen et al. 2006; Kestila, Martelin et al. 2008) Smoking has been widely cited as a risk factor involved in cardiovascular diseases.(Hae Guen, Eung Ju et al. 2008; Rudolph, Rudolph et al. 2008) The pathway through which smoking may affect cardiovascular health likely involves the cholinergic system, initiation of oxidative stress, and inflammation.(Park, Lee et al. 2007; Huang, Okuka et al. 2008; Rudolph, Rudolph et al. 2008) Smoking also increases CVD-related coagulation factors such as fibrinogen (Folsom, Wu et al. 2000) and inflammatory markers including CRP.(Mendall, Patel et al. 1996)

Obesity is a major predictor of CRP (Hak, Stehouwer et al. 1999; Visser, Bouter et al. 1999; Yudkin, Stehouwer et al. 1999; Tracy 2001), as well as many inflammatory cytokines.(Cacciari 1988; Ferguson, Gutin et al. 1998; Shea, Isasi et al. 1999) Adipose tissue contributes to the synthesis of IL-6 and adipokines.(Mohamed-Ali, Goodrick et al. 1997; Bastard, Jardel et al. 1999) Epidemiological evidence supports the assertion that physical activity is inversely and strongly associated with CVD, possibly through its effects on reduction in adiposity among other mechanisms.(Blair, Kampert et al. 1996; Manson, Hu et al. 1999; Myers, Prakash et al. 2002; Kokkinos 2008; Kokkinos, Myers et al. 2008) Although the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which exercise can improve CVD-related outcomes are not currently well understood, physical activity may promote CVD-protective events such as increased antioxidant defenses and nitric oxide (NO) bioactivity, reduced oxidative stress, and reduction of free-radicals.(Leaf, Kleinman et al. 1999; Leeuwenburgh and Heinecke 2001; Steinberg and Witztum 2002; de Nigris, Lerman et al. 2003; Napoli, Williams-Ignarro et al. 2004; Ignarro, Balestrieri et al. 2007) With respect to diet, individuals who eat high fat diets are at increased risk of CVD (Yu-Poth, Zhao et al. 1999); conversely, individuals with diets high in fruits and vegetables often have a lower prevalence of CVD risk factors such as hypertension, obesity, and type 2 diabetes.(Ignarro, Balestrieri et al. 2007) As with physical activity, the biologic mechanisms by which diets high in fruits and vegetables exert their protective effects is not currently well understood; nutrients and phytochemicals in these items, such as fiber, potassium and folate, may contribute both independently and jointly to a reduced risk of CVD.(Bazzano, Serdula et al. 2003; Houston 2005)

IV. Measurement/Feasibility issues

Measurement and feasibility are major concerns in studies of biomarkers in population-based samples. There are a number of factors that can influence validation and this area has been reviewed by others.(Tworoger and Hankinson 2006) There are four common sources of measurement error that should be considered when examining biomarkers in population-based studies: biological specimen collection methods; processing and storage procedures; laboratory error (i.e. intra-assay and inter-assay variability); and within-person variability over time.(Tworoger and Hankinson 2006)

Biological specimen collection, or sample collection, involves a number of considerations that can impact measurement error. Although many types of specimens are theoretically available for collection from willing participants, including white or red blood cells, tissue biopsies, and saliva, it is critically important to choose the type of sample based first upon hypotheses of interest, and second upon the feasibility and ease of collection.(Tworoger and Hankinson 2006) Regarding the latter, sample collection for a particular biomarker can in some instances be completed by study participants without assistance, including saliva or urine. In these cases, the cost of the sample collection may be low, but may be counterbalanced by a higher level of error as the collection protocol would be implemented by many, perhaps even thousands, of individuals rather than one or a few trained clinical research assistants. Regarding the former, the biomarker under consideration should be selected in consultation with the laboratory staff to determine which type of sample is best suited to the biomarker assay of interest, as well as the appropriate method to process and store the sample. For example, if an investigator is interested in collecting blood specimens in order to test cytokine levels via ELISA, it is important to determine the time period within which samples need to be processed in order to retain their integrity, as well as the type of anticoagulant to use, as both of these factors have been shown to impact assay results.(Flower, Ahuja et al. 2000) Sample collection and storage issues become increasingly complex in screens involving multiple biomarkers, which may require that different types of samples be collected under different conditions. In these cases, extensive pilot studies that assess collection feasibility can help to reduce measurement error.(Tworoger and Hankinson 2006) Inflammatory and infectious markers such as CRP, IL-6, and herpesvirus IgG antibody levels have been shown to be relatively stable over repeat measures and in frozen serum.(Zweerink and Stanton 1981; Rao, Pieper et al. 1994; Macy, Hayes et al. 1997; Breen, McDonald et al. 2000; McDade, Stallings et al. 2000; McEwen 2000; Ockene, Matthews et al. 2001; Aziz, Fahey et al. 2003; Kvarnstrom, Karlsten et al. 2004; Rosa-Fraile, Sampedro et al. 2004)

For some biomarkers, there may be multiple types of biological samples that can be used to assess circulating marker levels. For example, cortisol can be assayed from saliva, plasma, and urine. Although there have been strong associations between levels of plasma free cortisol and salivary samples (Kirschbaum and Hellhammer 1994; Levine, Zagoory-Sharon et al. 2007), the correlations between salivary and urinary levels are inconsistent.(Yehuda, Halligan et al. 2003) This may also be an issue for other biomarkers such as cytokines which can be measured in plasma and serum.(Kropf, Schurek et al. 1997; Jankowiak, Zamzow et al. 1998) Thus, correspondence between biological samples is an important consideration when comparing results across or within studies.

Laboratory error represents an additional important source of variation that can contribute to measurement error. Intra-assay variability is an inherent component of most biomarker assays, such that replicates of the same specimen will always yield a distribution of results, rather than a single, repeated value.(Tworoger and Hankinson 2006) In contrast, inter-assay variability occurs when conducting a separate run or batch of an assay contributes an additional amount of variation to the value being measured. Both inter- and intra-assay variability can lead to a bias in effect estimates towards the null and reductions in statistical power.(Vineis 1997) Technological improvements can mitigate some of these problems, producing greater accuracy and precision in both intra- and inter-assay testing; for example, in a multi-center study of cytokine levels in serum and other fluids, a recently developed electrochemiluminescence-based assay showed low inter-laboratory and intra-assay variation, and was among the most discriminative of all the seven platforms that were tested in the study.(Fichorova, Richardson-Harman et al. 2008) In addition, running the assay in duplicate or more, using the same technician, conditions, and techniques, as well as increasing the sample size, can also minimize bias. The inclusion of quality control samples provides a further opportunity to assess assay variability, both within and between runs.(Tworoger and Hankinson 2006)

Biological variation in biomarkers within an individual over time represents a third important source of variation that can contribute to measurement error in biomarker-based studies. In this case, a single measurement of the biomarker within an individual may fail to accurately depict that individual's long-term exposure to a particular disease or condition. An important example is cortisol. There is large diurnal variability in cortisol secretion and significant within-person variation in the diurnal pattern. Thus, rather than collecting data on cortisol at a single time point, some have employed collection of repeated saliva measurements over one or more days.(Hruschka, Kohrt et al. 2005; Adam, Hawkley et al. 2006; Hellhammer, Fries et al. 2007; Levine, Zagoory-Sharon et al. 2007) Importantly, CRP and inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, are more stable throughout the day. Nevertheless, acute infections, autoimmune condition, and other serious conditions can lead to fluctuation of these markers.(de Maat, de Bart et al. 1996; Breen, McDonald et al. 2000; McDade, Burhop et al. 2004; Wong, Freiberg et al. 2008)

Multiple measurements over time can also assist in detecting significant effects that may otherwise be missed even with accurate, single time point measurements. For example, initial responses to experimentally-induced psychological stress was shown to be similar among low-, medium- and high SEP participants, as measured by Factor VIII, plasma viscosity and blood viscosity levels; however, 45 minutes after the stressor was applied, these markers remained more elevated in lower SEP participants.(Steptoe, Kunz-Ebrecht et al. 2003) This finding is significant in that, over many years of differential stress exposure, these small but detectable differences in the duration of activation of procoagulant pathways could translate into increased cardiovascular disease risk among low SES individuals.(Steptoe and Marmot 2002) Without multiple measurements of these biomarkers over even a relatively short period of time, these significant differences may have been missed.

Acute bacterial or viral infections, recent injury, autoimmune disease, chronic health conditions and medication use may influence results from biological sample testing. To assess the effects of these factors on biological markers of interest, it is important to obtain a medical history and record concurrent medication data from the time of biological sample collection. Trained interviewers should inspect all prescription and over-the-counter medications, identify and code them according to standard drug data base systems. A list showing some examples of medications that may be associated with variability in cellular and inflammatory markers of interest are presented in Table 3. This table displays some of the major classes of drugs that: (i) may be associated with treatment of acute infection or that (ii) have been associated with minimal to profound effects on immune functioning and inflammatory parameters.(Basterzi, Aydemir et al. 2005; Busti, Hooper et al. 2005; Barnes 2006; Greenwood, Steinman et al. 2006; Rogatsky and Ivashkiv 2006; Steffens and Mach 2006) There are different types of medication coding programs, such as Medispan™ system, which may be used to organize medication information obtained from participants. Each drug in these programs is associated with a code that is added to a directory of general drug categories and sub-categories (e.g. analgesic, statin, anti-infective). For analytical purposes, one would want to create groups of drugs as outlined in Table 3 (ie. infectious disease, autoimmune disease, etc.) for adjustment in statistical models.

Table 3.

Medications, immune function, and inflammation.

| Conditions | Example Agents | Example medications |

|---|---|---|

| Infectious diseases | Anti-infectives, Anti-fungals, Antiviral agents, Over-the counter medications (decongestant, expectorant, analgesic, antihistamine) | Antiretrovirals (efavirenz, atazanavir+ritonavir), Antivirals (acyclovir, ganciclovir, etc.); Antibiotics (Penicillins, Cephalosporins, Tetracycline, etc.); Cough/Cold/Allergy medications (pseudoephedrine, phenylpropanolamine, phenylenphrine, guaifenesin. |

|

| ||

| Autoimmune disease | Disease-modifying antirheumatic and anti-inflammatory agents | Methotrexate, Azathioprine, Leflunomide, D-penicillamine, hydroxychloroquine, TNF-α receptor antagonists, Anakinara, Tacrolimus, Cyclopsorine, etc |

|

| ||

| Inflammatory, cardiovascular, or psychological conditions | Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents, Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors, statins, anti-depressants | Diclofenac, naproxen, indomethacin, etc.; celecoxib, rofecoxib, valdecoxib, etc; simvistatin, pravistatin, etc.; mao-inhibitor, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (prozac, celexa, paxil, etc.) |

|

| ||

| Inflammatory states | Corticosteroids | Cortisone, prednisone, dexamethasone etc. |

Another factor which may influence the results of biological sample testing is fasting status. Depending on the type of test, fasting may be recommended for 8-12 hours or more. In most cases, subjects are asked to continue medications during the fasting period as prescribed unless otherwise determined by their medical doctor. In a study of more than 30 of the most common blood tests conducted at Helsinki City Hospitals, the majority of blood tests demonstrated statistically significant variability among fasting versus non-fasting samples.(Leppanen and Dugue 1998) In a study by Dugue et al, (Dugue and Leppanen 1998) significant decreases in the concentration of interleukin-6 were observed following the consumption of breakfast. Therefore, it is essential to develop protocols regarding fasting versus non-fasting requirements. Additionally, for the purposes of analysis, it is important to record the time and date an individual consumed anything other than water prior to biological sample collection and to control for such deviations from protocol in statistical models.

The collection of biological samples also raises important ethical issues related to respondent burden.(Finch, Vaupel et al. 2001) In any given population, respondent burden will vary depending on many factors, including, but not limited to: an individual's perception of the risk versus benefit of providing a sample, the method of sample collection, fasting requirements, the amount of time/travel required, an individual's prior experience with research or sample provision, individual fear or anxiety levels related to clinical procedures, religious/cultural values, and health status. There are many protocol measures one can employ to help reduce respondent burden. For example, studies can provide ethical incentives for participants, travel to an individual's home/business for sample collection, utilize highly accessible collection sites, and reimburse travel expenses. In addition, it is important to explain the ‘bigger picture’ of the research, involve respected community leaders in the research process, provide counseling to participants, and highlighting the maintenance of anonymity provided by numerically-coded labeling of collected specimens. In addition, offering an alternate method of collection to individuals who initially decline consent may reduce burden and increase participation levels. For example, when collecting blood, an individual refusing venipuncture, which involves the insertion of a needle into the vein, may consent to a blood spot, in which the tip of the finger is pricked, when presented with this alternative.

V. Conclusions and Applications of Biomarkers in PSID

The relationship between SEP, psychosocial stress and health outcomes, and their intermediate biological pathways, is complex. It is worth thinking about where the PSID can be most useful in understanding this relationship. In particular we draw a distinction between large studies such as the PSID which view this relationship from “20,000 feet” and smaller studies that have the ability to measure behavioral and biological pathways with precision and detail. We have argued earlier that with its exquisite measurement of socioeconomic position and family composition over long periods, and changes in both, the PSID is exceptionally well-suited to assess the associations between the SEP-related psychosocial stressors associated with these and other health outcomes such as risk of death. The longitudinal nature of the PSID could also be very useful in analyzing not only the impact of SEP and related psychosocial pathways on health, but also the extent to which socioeconomic resources mitigate or amplify the impact of exogenous shocks (job loss due to recession, disasters, etc,) on biomarkers and health outcomes. With adequate waves of biomarker data collection, subsequent effects of biomarkers and health conditions could also be assessed. In our review of life course SEP studies, the majority utilized retrospective recall of early life SEP. Indeed, Galobardes et al. and Kauhanen et al. have found that adult recall of SEP measures from childhood tend to systematically underestimate the true association between objective measures of childhood SEP and adult CVD outcomes(Kauhanen, Lakka et al. 2006; Galobardes, Lynch et al. 2008). Thus, the PSID can help fill this gap by providing a large range of SEP measures that are not based solely on retrospective reports. Going beyond such analyses, to a finer characterization of stress, the critical behavioral and biological pathways, and more specific health outcomes carries with it challenges that must be addressed in the PSID and other studies like it.

While the size of the PSID sample and the quality of its data are compelling, one cannot help but focus on some of its limitations. For example, generally there is no consistent pattern of data collection on the important psychological and behavioral pathways that are critical in interpreting any observed association between life-course SEP, psychosocial stressors and health outcomes, or their biological pathways. In addition, while self-reported measures of medically diagnosed health conditions can be valuable they are also biased by access to medical care, health literacy, and generally non-specific. Parenthetically, while self-rated health status is widely used as an outcome in social science, its general nature means that observed associations between it and biological pathways linking stress and health outcomes is not likely to be very informative. In addition, the lack of clinical detail in self-reported health data, compared to examination-based or record linkage-based information, makes it difficult to interpret observed associations with psychosocial stressors. Indeed, where there are carefully measured biomarker data, the quality of such data may be so superior to the behavioral, psychological, and health data as to make for very confusing results. In addition, where the biomarker data are not collected with the level of control and precision available in smaller studies, the connection of these biomarkers to health outcomes may be severely compromised. Finally, while there is often great biological plausibility and enthusiasm associated with the importance of many biomarkers, the evidence for their associations with psychosocial stressors is often far from conclusive, as is the evidence relating them to clinically significant health outcomes.

In our view, links between stress and health can, with the above provisos, be studied in the PSID, but the inclusion of biomarker data should be very carefully considered. We do not view the PSID as an appropriate venue for exploring stress-health links and the underlying biological pathways for novel markers. However, assuming that criteria for measurement, transport, assay, and storage can be met, that the psychological and behavioral pathways linking stress to specific health outcomes are well understood from smaller focused studies, and that the links between biomarkers and well-characterized health conditions are known, then the PSID can add considerably to our knowledge of the ways in which psychosocial stressors associated with socioeconomic position and family composition are linked to poorer health and some of the biological pathways.

In conclusion, the PSID should consider assessments of biomarkers of CVD discussed here. We suggest specifically those measures reported to be relatively stable over time, such as IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, fibrinogen, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, P- and L-selectins , CMV, and HSV, and not those that are subject to acute context effects or that require multiple measurements throughout the day. We also suggest that PSID consider adding important assessments of mediating behavioral measures, health, and medication assessments that will ultimately address many of the gaps in the literature regarding the relationship between SEP and biomarkers of cardiovascular health.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Narayan Sastry, Bob Schoeni, and Kate McGonagle for their assistance with this project and for the invitation to participate in the 2008 PSID Biomeasure conference. We also thank all of the researchers and staff who participated in the 2008 PSID Biomeasure conference for helpful discussions and assistance.

Financial Support: The Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) supported this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Adam EK, Hawkley LC, et al. Day-to-day dynamics of experience--cortisol associations in a population-based sample of older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(45):17058–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605053103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello AE, Diez-Roux A, Noone AM, Ranjit N, Cushman M, Tsai M, Szklo M. Socioeconomic and Psychosocial Gradients in Cardiovascular Pathogen Burden and Immune Response: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Brain Behav Immun. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.12.006. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alley DE, Seeman TE, et al. Socioeconomic status and C-reactive protein levels in the US population: NHANES IV. Brain Behav Immun. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RN, Smith BL. Deaths: leading causes for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2005;53(17):1–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appels A, Bar FW, et al. Inflammation, depressive symptomtology, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):601–5. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz BB, Brenner SO, et al. Neuroendocrine and immunologic effects of unemployment and job insecurity. Psychother Psychosom. 1991;55(2-4):76–80. doi: 10.1159/000288412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashavaid TF, Kondkar AA, et al. Lipid, lipoprotein, apolipoprotein and lipoprotein(a) levels: reference intervals in a healthy Indian population. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2005;12(5):251–9. doi: 10.5551/jat.12.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz N, Fahey JL, et al. Analytical performance of a highly sensitive C-reactive protein-based immunoassay and the effects of laboratory variables on levels of protein in blood. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10(4):652–7. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.4.652-657.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltrus PT, Lynch JW, et al. Race/ethnicity, life-course socioeconomic position, and body weight trajectories over 34 years: the Alameda County Study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1595–601. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.046292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1995;311(6998):171–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ. Fetal origins of cardiovascular disease. Ann Med. 1999;31 1:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Corticosteroids: the drugs to beat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533(1-3):2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastard JP, Jardel C, et al. Evidence for a link between adipose tissue interleukin-6 content and serum C-reactive protein concentrations in obese subjects. Circulation. 1999;99(16):2221–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basterzi AD, Aydemir C, et al. IL-6 levels decrease with SSRI treatment in patients with major depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(7):473–6. doi: 10.1002/hup.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum A, Garofalo JP, et al. Socioeconomic status and chronic stress. Does stress account for SES effects on health? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:131–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzano LA, Serdula MK, et al. Dietary intake of fruits and vegetables and risk of cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2003;5(6):492–9. doi: 10.1007/s11883-003-0040-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Mizrachi L, Jy W, et al. High levels of circulating endothelial microparticles in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2003;145(6):962–70. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair SN, Kampert JB, et al. Influences of cardiorespiratory fitness and other precursors on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women. JAMA. 1996;276(3):205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstadter J, Baltes-Gotz B, et al. Developmental and personality correlates of adrenocortical activity as indexed by salivary cortisol: observations in the age range of 35 to 65 years. J Psychosom Res. 1991;35(2-3):173–85. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(91)90072-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen EC, McDonald M, et al. Cytokine gene expression occurs more rapidly in stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7(5):769–73. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.5.769-773.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busti AJ, Hooper JS, et al. Effects of perioperative antiinflammatory and immunomodulating therapy on surgical wound healing. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(11):1566–91. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.11.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciari E. [Obesity as a risk factor in children] An Esp Pediatr. 1988;29 32:267–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas JP, Shah T, et al. C-reactive protein and coronary heart disease: a critical review. J Intern Med. 2008;264(4):295–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermak J, Key NS, et al. C-reactive protein induces human peripheral blood monocytes to synthesize tissue factor. Blood. 1993;82(2):513–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerne D, Ledinski G, et al. Comparison of laboratory parameters as risk factors for the presence and the extent of coronary or carotid atherosclerosis: the significance of apolipoprotein B to apolipoprotein all ratio. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2000;38(6):529–38. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2000.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M, Hashmi S, et al. Relationships of adiponectin and matrix metalloproteinase-9 to tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 ratio with coronary plaque morphology in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24(5):385–90. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70602-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa G, Sirtori CR. Recombinant apolipoprotein A-I(Milano): a novel agent for the induction of regression of atherosclerotic plaques. Ann Med. 2003;35(4):267–73. doi: 10.1080/07853890310005281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Keynote Presentation at the Eight International Congress of Behavioral Medicine: the Pittsburgh common cold studies: psychosocial predictors of susceptibility to respiratory infectious illness. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12(3):123–31. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1203_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Frank E, et al. Types of stressors that increase susceptibility to the common cold in healthy adults. Health Psychol. 1998;17(3):214–23. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kessler RC, et al. Strategies for measuring stress in studies of psychiatric and physical disorders. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. 1995:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cook DG, Whincup PH, et al. Fibrinogen and factor VII levels are related to adiposity but not to fetal growth or social class in children aged 10-11 years. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(7):727–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesh J, Collins R, et al. Association of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, albumin, or leukocyte count with coronary heart disease: meta-analyses of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279(18):1477–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.18.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesh J, Whincup P, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae IgG titres and coronary heart disease: prospective study and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2000;321(7255):208–13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7255.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Maat MP, de Bart AC, et al. Interindividual and intraindividual variability in plasma fibrinogen, TPA antigen, PAI activity, and CRP in healthy, young volunteers and patients with angina pectoris. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16(9):1156–62. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.9.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nigris F, Lerman A, et al. Oxidation-sensitive mechanisms, vascular apoptosis and atherosclerosis. Trends Mol Med. 2003;9(8):351–9. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(03)00139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentino AN, Pieper CF, et al. Association of interleukin-6 and other biologic variables with depression in older people living in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(1):6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Napoli M, Schwaninger M, et al. Evaluation of C-reactive protein measurement for assessing the risk and prognosis in ischemic stroke: a statement for health care professionals from the CRP Pooling Project members. Stroke. 2005;36(6):1316–29. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000165929.78756.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):99–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djordjevic VB, Stojanovic I, et al. Serum neopterin, nitric oxide, inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels in patients with ischemic heart disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46(8):1149–55. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotsenko O, Chackathayil J, et al. Candidate circulating biomarkers for the cardiovascular disease continuum. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(24):2445–61. doi: 10.2174/138161208785777388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd JB, Aiello AE, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in the seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the US population: NHANES III. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137(1):58–65. doi: 10.1017/S0950268808000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd JB, Goldman N. Do biomarkers of stress mediate the relation between socioeconomic status and health? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(7):633–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.040816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd JB, Haan MN, et al. Socioeconomic gradients in immune response to latent infection. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(1):112–20. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle WJ, Gentile DA, et al. Emotional style, nasal cytokines, and illness expression after experimental rhinovirus exposure. Brain Behav Immun. 2006;20(2):175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugue B, Leppanen E. Short-term variability in the concentration of serum interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor in subjectively healthy persons. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1998;36(5):323–5. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1998.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid HM, Lyberg T, et al. Reactive oxygen species generation by leukocytes in populations at risk for atherosclerotic disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2002;62(6):431–9. doi: 10.1080/00365510260389985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein SE. The multiple mechanisms by which infection may contribute to atherosclerosis development and course. Circ Res. 2002;90(1):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson MA, Gutin B, et al. Fat distribution and hemostatic measures in obese children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67(6):1136–40. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.6.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichorova RN, Richardson-Harman N, et al. Biological and technical variables affecting immunoassay recovery of cytokines from human serum and simulated vaginal fluid: a multicenter study. Anal Chem. 2008;80(12):4741–51. doi: 10.1021/ac702628q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtlscherer S, Rosenberger G, et al. Elevated C-reactive protein levels and impaired endothelial vasoreactivity in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2000;102(9):1000–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch CE, Vaupel JW, et al. Cells and Surveys: Should Biological Measures Be Included in Social Science Research? National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flower L, Ahuja RH, et al. Effects of sample handling on the stability of interleukin 6, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and leptin. Cytokine. 2000;12(11):1712–6. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom AR, Wu KK, et al. Determinants of population changes in fibrinogen and factor VII over 6 years: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(2):601–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.2.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom AR, Wu KK, et al. Prospective study of hemostatic factors and incidence of coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation. 1997;96(4):1102–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.4.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Giles WH. Serum C-reactive protein and fibrinogen concentrations and self-reported angina pectoris and myocardial infarction: findings from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo WT, Teng HM, et al. The impact of late career job loss on myocardial infarction and stroke: a 10 year follow up using the health and retirement survey. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(10):683–7. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.026823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B, Lynch JW, et al. Is the association between childhood socioeconomic circumstances and cause-specific mortality established? Update of a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(5):387–90. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.065508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B, Smith GD, et al. Systematic review of the influence of childhood socioeconomic circumstances on risk for cardiovascular disease in adulthood. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(2):91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges JL, Rupprecht HJ, et al. Impact of pathogen burden in patients with coronary artery disease in relation to systemic inflammation and variation in genes encoding cytokines. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(5):515–21. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00717-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girod JP, Brotman DJ. Does altered glucocorticoid homeostasis increase cardiovascular risk? Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64(2):217–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(3):243–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, et al. Stress, loneliness, and changes in herpesvirus latency. J Behav Med. 1985;8(3):249–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00870312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Robles TF, et al. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1009–14. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.10.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowinska B, Urban M, et al. Soluble adhesion molecules (sICAM-1, sVCAM-1) and selectins (sE selectin, sP selectin, sL selectin) levels in children and adolescents with obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. Metabolism. 2005;54(8):1020–6. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E, McEwen BS, et al. Social inequalities in biomarkers of cardiovascular risk in adolescence. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):9–15. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000149254.36133.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori AM, Cesari F, et al. The balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines is associated with platelet aggregability in acute coronary syndrome patients. Atherosclerosis. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JE, Robles TF, et al. Hostility and pain are related to inflammation in older adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D, Foiles N, et al. Elevated fibrinogen levels and subsequent subclinical atherosclerosis: The CARDIA Study. Atherosclerosis. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood J, Steinman L, et al. Statin therapy and autoimmune disease: from protein prenylation to immunomodulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(5):358–70. doi: 10.1038/nri1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotto I, Huerta M, et al. Hypertension and socioeconomic status. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2008;23(4):335–9. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3283021c70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hae Guen S, Eung Ju K, et al. Relative contributions of different cardiovascular risk factors to significant arterial stiffness. Int J Cardiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hak AE, Stehouwer CD, et al. Associations of C-reactive protein with measures of obesity, insulin resistance, and subclinical atherosclerosis in healthy, middle-aged women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(8):1986–91. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.8.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellhammer J, Fries E, et al. Several daily measurements are necessary to reliably assess the cortisol rise after awakening: state- and trait components. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(1):80–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert TB, Cohen S. Depression and immunity: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 1993;113(3):472–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert TB, Cohen S. Stress and immunity in humans: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 1993;55(4):364–79. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz I, Rosso R, et al. Serum levels of anti heat shock protein 70 antibodies in patients with stable and unstable angina pectoris. Acute Card Care. 2006;8(1):46–50. doi: 10.1080/14628840600606950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holvoet P, Lee DH, et al. Association between circulating oxidized low-density lipoprotein and incidence of the metabolic syndrome. JAMA. 2008;299(19):2287–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.19.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]