Abstract

Background

Most community-based participatory research (CBPR) projects involve local communities defined by race, ethnicity, geography, or occupation. Autistic self-advocates, a geographically dispersed community defined by disability, experience issues in research similar to those expressed by more traditional minorities.

Objectives

We sought to build an academic–community partnership that uses CBPR to improve the lives of people on the autistic spectrum.

Methods

The Academic Autistic Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education (AASPIRE) includes representatives from academic, self-advocate, family, and professional communities. We are currently conducting several studies about the health care experiences and well-being of autistic adults.

Lessons Learned

We have learned a number of strategies that integrate technology and process to successfully equalize power and accommodate diverse communication and collaboration needs.

Conclusions

CBPR can be conducted successfully with autistic self-advocates. Our strategies may be useful to other CBPR partnerships, especially ones that cannot meet in person or that include people with diverse communication needs.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, process issues, autism, autistic community, self-advocacy, disability, remote collaboration, atypical communication

CBPR approaches have revolutionized the science of health care disparities. Most CBPR projects, however, have involved local communities defined by race, ethnicity, geography, or occupation.1 This paper describes lessons learned from creating a community–academic partnership with a geographically dispersed community of autistic self-advocates.

AASPIRE (www.aaspire.org) evolved from an informal “journal club” composed of autistic self-advocates and parents of autistic children. The more research studies the group reviewed, the more frustrated members became with problematic issues in the autism literature: A misalignment between researchers’ priorities and those of the autistic community; a lack of inclusion of autistic individuals in the research process; use of demeaning or derogatory language and concepts; threats to study validity derived from miscommunication between researchers and participants; and the use of findings to advance agendas that opposed community values.

For example, the group reviewed a paper about an functional magnetic resonance imaging study2 whose results were popularized as proving that autistics do not daydream.3 These reports angered many autistic self-advocates who knew that they daydreamed and felt the research questions were less pressing than other issues affecting their lives. They questioned the validity of the results, noting that the protocols did not take into account literal interpretation of language or challenges related to task switching. They also felt the deficit-based language in the research paper was stigmatizing and the conclusions reinforced dehumanizing stereotypes. They argued that had they been asked, they would have chosen more useful research questions and created protocols that took into account the way that autistic individuals process information.4

One of the parents, a health-services researcher conducting CBPR with African-American and Latino communities, recognized the similarity between these frustrations and those expressed by other marginalized communities. One of the self-advocates, a graduate student with an interest in complex systems, recognized the complex sociocultural dynamics that deprive autistic individuals from having influence in how autism research is conducted or how findings are used. The two decided to form an academic–community partnership to conduct research to improve the lives of people on the autistic spectrum.

Although the group’s criticisms of traditional autism research were similar to the arguments that led to the creation of CBPR, applying the principles of CBPR to this specific situation brought new challenges. One should consider the community as a unit of identity,5 but how do we define the autistic community? CBPR should be conducted with local communities,5 but what if the community is located virtually? How do we implement CBPR—an approach that relies heavily on interpersonal interactions and communication—with partners whose disability is defined by atypical social interaction and communication? Four years later, AASPIRE has created a strong infrastructure for collaboration and is conducting several funded research projects. Herein we have outlined some of the early lessons learned and questions that persist.

METHODS

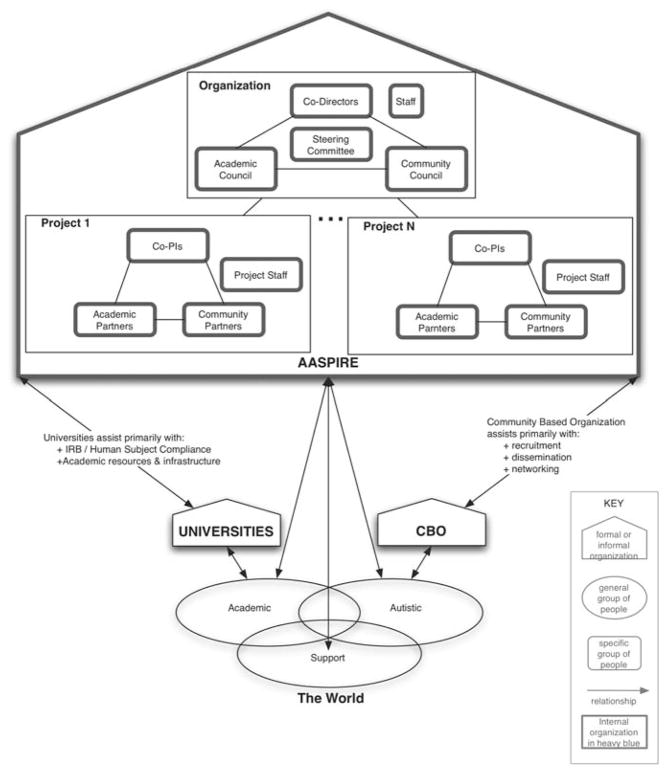

AASPIRE is an academic–community partnership composed of health services and disability researchers, autistic self-advocates, health care providers, disability service professionals, and family members. It is co-directed by its founding members, one representing the academic and support communities and the other representing the autistic community. The two women work closely together on a daily basis to run the organization. They share all decisions and jointly create all materials, from policies and grant proposals to agendas and internal memos. A Steering Committee, which includes the co-directors and three additional members (representing the academic, autistic, and support communities), primarily resolves disputes and makes decisions that do not have time to be addressed by the full team. Most high-level organizational decisions, such as what to study, how to compensate members given limited funding, or what to communicate with the public, are made by the full AASPIRE team, which includes an academic and a community council (Figure 1.) The full team is also invited to co-author papers such as this one, with both academic and community partners contributing concepts, text, and edits. Each individual research project is co-led by an academic and a community principal investigator, and includes a team of both academic and autistic research partners.

Figure 1.

AASPIRE’s Infrastructure

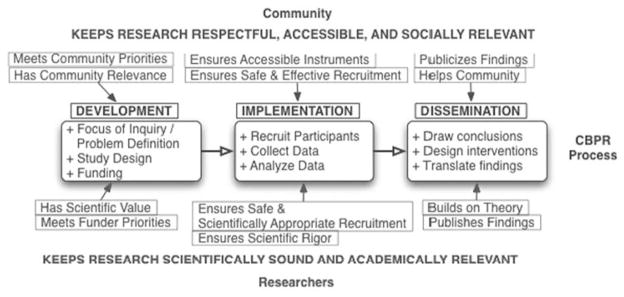

As shown in Figure 2, academic and community members serve as equal partners in all phases of the research. Each partner brings his or her own professional and personal expertise. Throughout the entire research process, the community ensures that the research is respectful, accessible, and socially relevant. The scientists ensure that the research is scientifically sound and academically relevant, that the work has the proper rigor, and that it advances academic goals. All AASPIRE team members work together to decide what to study, selecting from topics that community members feel are important. One challenge has been that community partners are interested in more topics than what we can actually study. We have had to work together to narrow the topics to a smaller subset that is feasible given available academic expertise and funders’ priorities. As we work together to obtain funding, community partners ensure that each study meets the community’s priorities and has community relevance, and academic partners ensure that it meets funders’ priorities and has scientific relevance.

Figure 2.

The CBPR Process

We then collaborate to design protocols, develop and adapt instruments and consent materials, recruit participants, collect and analyze data, and disseminate findings (Figure 2). For example, when designing survey studies, after the whole group has decided which constructs to measure, academic partners identify potential instruments that might be used and inform the group about their psychometric properties. Community partners inform the group about potential offensive or unclear language or assumptions. Together the group chooses which instruments to use and then collaborates on adapting them to make them accessible to autistic individuals—eliminating ambiguity, adding specificity, and adding “hot links” to potentially confusing terms. We use a similar process to collaboratively create study protocols, recruitment and consent materials, and interview guides. We also collaboratively analyze and interpret data. For example, in our qualitative studies, two investigators—one autistic and one non-autistic—formally code interview transcripts. The full team finalizes themes and interpretations. The academic and community co-principal investigators then jointly implement the team’s decisions, either by themselves or with the help of research staff, a majority of whom are on the autistic spectrum or are parents of autistic individuals.

We are currently conducting several studies, including an online, mixed-methods study to assess health care disparities and to understand autistic adults’ health care experiences and recommendations. Another study examines Internet use, connectedness, and well-being. We are also collaborating with others on a registration system for ongoing research (the Gateway Project) and a large observational study funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention about the relationship between violence victimization and health in people with developmental disabilities. Academic and community partners have co-presented at national and international meetings and co-authored this and other manuscripts.

LESSONS LEARNED

Who Is “the Community”?

Over the past few decades, there has been growing recognition of disability cultures6,7 and of distinct communities— such as the deaf community—that are defined by disability.8 In the United States, the autism self-advocacy movement has grown out of the disability rights movement.9,10 Communities of autistic individuals now exist internationally.11,12 Like other minority communities, they have their own culture, support systems, leaders, shared values, social spaces, annual events, organizations, conferences, and terminology.9,12–14

Most minority communities follow a pattern whereby individuals are born into families of the same minority status (e.g., race, ethnicity). The autistic community, like the lesbian/ gay/bisexual/transgendered and deaf communities, follows a different pattern, where community members come from predominantly non-autistic, heterosexual, or hearing families, respectively.15 This pattern creates challenges for defining the unit of identity in CBPR, because family members are important stakeholders, but their values or priorities can at times be in opposition to the values or priorities of the minority community. For example, many parent- and professional-run autism organizations have historically directed their efforts toward finding a “cure” for autism, blaming factors such as vaccines for harming their children, or emphasizing the devastating effect they perceive autism to have on families. A 2008 analysis of major funders by the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee showed that of $22,459,793 private and federal monies, 37% went to questions of “what caused this to happen and how can this be prevented,” 24% to “which treatments and interventions will help,” and 18% to “how can I understand what is happening.”16

Many autistic individuals contend that some messages by parent-run organizations are dehumanizing and harmful. For example, they strongly criticized the Autism Speaks’ “I am Autism” video for portraying autistic people as burdens or objects of fear and pity.17 They also argue that the research priorities do little to address their real-life concerns.18–20 Only 5% of 2008 research dollars were allocated to questions related to “what does the future hold” and only 1% were allocated to questions surrounding “where can I turn for services.”16 Autistic self-advocacy organizations have asked for research and programs to improve quality of life for people on the autistic spectrum, for example, by improving health care, reducing violence and bullying, increasing access to alternative communication, disproving false stereotypes, or increasing employment opportunities.21

AASPIRE has chosen to focus on the priorities of the self-advocacy community and has created a mission statement reinforcing this ideal (Table 1). We welcome family members as important stakeholders, as long as they are interested in supporting the mission of the partnership. One might question our decision to focus specifically on the autistic self-advocacy community. However, our decision is similar to what health disparities researchers might make if partnering with other minority groups that follow an individual membership pattern. For example, if a group wanted to conduct research on improving health care for gay men, they would primarily work with gay men and their allies. Although there may be gay men or family members who believe that homosexuality is immoral or should be “cured,” it is unlikely that those individuals would join the project or that the project team would spend significant time debating the morality of homosexuality. Similarly, family members who have expressed interest in working with us do so because they believe in the importance of our mission. We generally do not spend time debating autism politics, other than to be aware of how they may affect our ability to recruit as wide a range as possible of autistic participants. For example, after an interesting discussion where both autistic and non-autistic team members indicated their preference for the term “autistic adults” and strong dislike of the term “adults with autism,” the group decided to use the less politicized term “adults on the autistic spectrum” in recruitment materials. More often, we spend our time discussing the details of our work, such as why a particular survey item is confusing and how it should be adapted.

Table 1.

AASPIRE Mission Statement

| To encourage the inclusion of adults on the autistic spectrum in matters which directly affect them. |

| To include adults on the autistic spectrum as equal partners in research about autism. |

| To answer research questions that are considered relevant by the autistic community. |

| To use research findings to effect positive change for people on the autistic spectrum. |

What If the Community Is Not Local?

CBPR typically focuses on local communities. Although AASPIRE started in Portland, Oregon, the original autistic partners felt stronger ties to the international online autistic community than to any local group. As has been commonly noted, “the impact of the Internet on autistics may one day be compared in magnitude to the spread of sign language among the deaf.”22 The Internet can equalize communication for autistic adults who may experience challenges interpreting body language, who cannot process auditory language in real time, or who require longer response times in conversations.23–26 Additionally, the Internet enables ready communication for sparse, geographically dispersed populations who otherwise may have little means to even find each other, let alone interact often enough to develop a sense of community. AASPIRE has community partners from across the United States and one from Germany.

Both the physical dispersal and communication needs of the autistic community have led AASPIRE to work primarily via remote collaboration. We knew from the start that many of our autistic team members would find it difficult or impossible to communicate over the telephone, so we hold our meetings with text-based Internet chat. Such meetings have at times been challenging for some of the non-autistic academic and support community partners, but the experience has also helped to increase empathy for what it is like to have to communicate in a non-preferred mode. We have learned to provide accommodations (e.g., telephone calls) for some of our non-autistic team members. Autistic partners have at times assisted non-autistic partners with learning how to use remote collaboration tools and become comfortable with basic “netiquette” (online rules for interaction). We have an e-mail list-serve for communication between meetings and for individuals who find real-time discussion insufficient for getting their ideas across. Given the team’s diverse communication preferences, AASPIRE offers all partners—both autistic and non-autistic—the option to review and provide feedback to materials and contribute to decision making via e-mail, text-based chat, telephone, or, for those in Portland, in-person meetings.

Remote collaboration can at times be slow and large group meetings are not always appropriate for the work that needs to be done. A small group in Portland, including the two co-directors, the academic and community council chairs, and the research staff, regularly meet in person to implement the decisions made by the larger team and facilitate inclusive day-to-day operations.

How Can We Balance Power and Ensure Full Inclusion of All Team Members?

CBPR attempts to equalize power between academics and members of marginalized or oppressed communities. In our case, it is the autistic self-advocates who have been most marginalized and oppressed by greater society. Many of our collaboration strategies were chosen to equalize power and enable full participation by members of the self-advocacy community. As above, our use of a primarily text-based, online medium has greatly increased the power of our autistic members, who in general are more proficient in this medium than the non-autistic members. However, other challenges have arisen. We regularly try new strategies for improving communication and balancing power, seeing ourselves as a “learning organization”27 that continuously adapts to its members’ needs and strengths and evolves to meet new challenges and solve old problems.

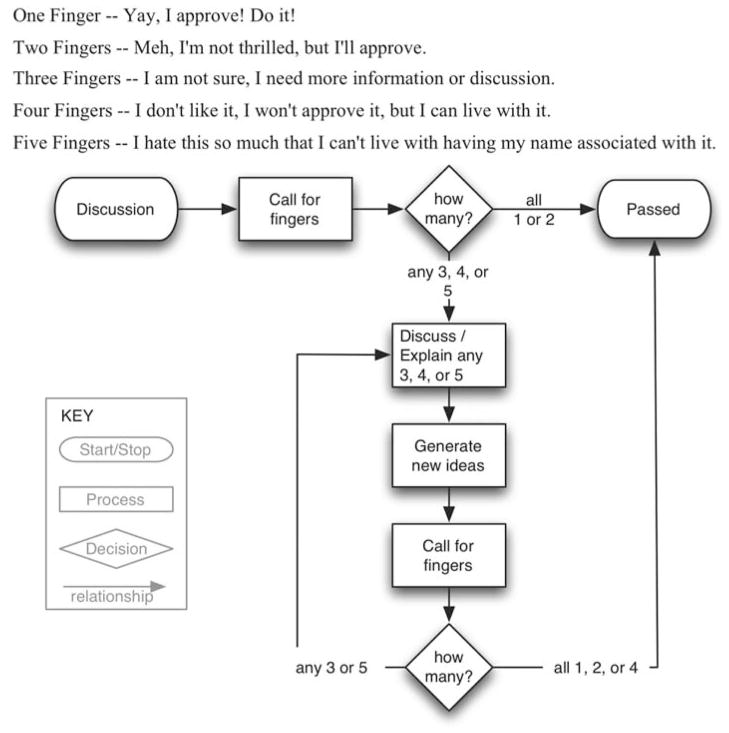

First, we have had to find a way for a very diverse group of individuals to come to consensus on important decisions. We did not feel a traditional vote would be adequate, because we did not want to disregard the voices of those in the minority. We were concerned that more “vocal” members may dominate the conversation and wanted to make room for everyone to be heard. We also sometimes were challenged by long, interesting e-mail threads that did not result in clear decisions or plans of action. We thus adapted the five finger method for making decisions or reaching consensus (Figure 3.) We have found this method invaluable for ensuring everyone has a chance to contribute and all members have a clear understanding about what is being decided.

Figure 3.

The Five-Finger Discussion/Decision Method

Second, some partners find off-topic discussions confusing or need additional time to process information. The community co-director thus moderates all meetings, ensuring that we are sticking to agendas, clearly noting changes in topic, and allowing 30 to 60 seconds to elapse after the last comment before moving to a new topic so that everyone has had a chance to read, understand, and type out their input.

Third, some community partners felt overwhelmed by vague or complex e-mail messages. Based on an autistic partner’s suggestion, we now use a standard message format, which lists the purpose of the e-mail message, the expected actions, and the deadline for responding, before elaborating on details organized by structured topic headings. This strategy had an enormous positive impact for the whole team, with non-autistic partners indicating that they have benefited just as much from the more structured e-mail approach as have the autistic partners.

Last, we have struggled to balance people’s desire for ongoing discussion with the need to implement decisions so we can move forward in our work. We now have a policy that after the group comes to consensus, discussion is closed. Members can ask to reopen discussion, but need to specifically state why they believe it is necessary to do so.

Like any community–campus partnership, we still have areas for improvement. Given the extra time that our communication accommodations require, and the academic partners’ intensely busy schedules and propensity for producing materials very close to submission deadlines, a particularly challenging issue has been how to allow community partners adequate time to review materials. Academic partners are working to establish new timelines for their work.

CONCLUSIONS

It is possible and desirable to use a CBPR approach with the autistic self-advocacy community. Autistic self-advocates represent a true community that can be considered a unit of identity for conducting CBPR. They are capable of working as equal partners in CBPR. Including autistic self-advocates as equal partners in CBPR requires significant attention to infrastructure and practices that equalize power and accommodate diverse needs. This work has the potential to transform the field of autism research and improve the lives of autistic adults. Like any CBPR partnership, effective collaboration entails a constantly evolving process to meet each new challenge. Although not all communication may be ideal for all partners all the time, everyone has always been willing to meet each other half way and to be patient and forgiving of each other’s challenges and needs.

Aside from its stated goals, AASPIRE has had a significant personal and professional effect on its members. Community partners have gained important skills and connections that have in some cases directly led to employment opportunities. Parent members have gained invaluable insights from autistic partners and have often used these insights to better relate to their autistic children. Working with AASPIRE has not only resulted in grants and publications, but it has also led to major career shifts and new opportunities for our academic partners and their students who care about socially relevant research. All of us have developed strong, meaningful friendships.

There remain some unanswered questions. For example, although many of our autistic partners find communicating with speech challenging or impossible, they can communicate using text-based media. If we want to improve the health of all individuals on the spectrum, how do we include autistic individuals who do not have Internet access or who cannot communicate well in writing? In our upcoming studies, we plan on recruiting participants from two samples—a national sample of Internet users and a local sample of adults who do not use the Internet. We are still exploring effective means for including non-Internet users on the research team. Moreover, it is unclear how, or if, our partnership will be able to directly include individuals who cannot communicate via writing, speech, or sign language. At this point, we must rely largely on the insights of people who regularly support these individuals, but it is not known how accurately supporters can represent their views. Many CBPR partnerships begin with more connected or organized members of marginalized communities. As others have done, we hope to identify ways to be increasingly more inclusive over time.

Our next steps are to create and test interactive tools that autistic adults, supporters, and primary care providers can use to increase patient-centered care and improve health outcomes. We hope that our work not only improves the lives of autistic adults, but also reinforces the idea that autism research should be conducted with, not just about, autistic people.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health grant (K23MH073008), Portland State University, Oregon Health and Science University, and the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (OCTRI), grant number UL1 RR024140 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

The authors thank all the AASPIRE academic and community partners, interns, and research staff, including Angie Mejia, MS, Michael Higginbotham, Melanie Fried-Oken, PhD, CCSP, Ari Ne’eman, Roberta Delaney, Jane Rake, Kim Goldman, Rhonda Way, Colleen Kidney, Aubrey Perry, and Sally Ison. We appreciate the support of the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, especially for their help with recruitment and dissemination efforts.

References

- 1.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Gartlehner G, Lohr K, Grifith D, et al. Carolina RI-UoN. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy DP, Redcay E, Courchesne E. Failing to deactivate: Resting functional abnormalities in autism. Biol Sci–Neurosci. 2006;103:8275–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600674103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearson H. Autistic brains may daydream less. [cited 2010 Sep 6]. Available from: http://www.nature.com/news/2006/060508/full/news060508-3.html.

- 4.Raymaker D. Review of “Daydreaming” paper. Asperger Syndrome Livejournal Community; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters S. Is there a disability culture? A syncretisation of three possible world views. Disability Society. 2000;15:583–601. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters S. Disability culture. In: Albrecht G, editor. Encyclopedia of disability. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2006. pp. 412–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corker M. Deafness/disability–Problematising notions of identity, culture and structure. In: Riddell S, Watson N, editors. Disability, culture and identity. London: Pearson; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertson SM, Ne’eman AD. Autistic acceptance, the college campus, and technology: Growth of neurodiversity in society and academia. Disability Studies Quarterly. 2008;28(4) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro J. Times Books. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamak B. Autism and social movements: French parents’ associations and international autistic individuals’ organisations. Sociol Health Illn. 2008;30:76–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinclair J. Autism network international: The development of a community and its culture. [cited 2010 Sep 6]. Available from: http://www.autreat.com/History_of_ANI.html.

- 13.Bumiller K. Quirky citizens: Autism, gender, and reimagining disability. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 2008;33:967–91. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson J. Autistic culture online: Virtual communication and cultural expression on the spectrum. Social & Cultural Geography. 2008;9:791–806. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz P. Building alliances: Community identity and the role of allies in autistic self-advocacy. In: Short S, editor. Ask and tell: Self-advocacy and disclosure for people on the autism spectrum. Shawnee Mission (KS): Autism Asperger Publishing Co; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office of Autism Research Coordination. Autism spectrum disorder research 2008 portfolio analysis report. [cited 2010 Sep 6]. Available from: http://iacc.hhs.gov/portfolio-analysis/2008/index.shtml.

- 17.Wallis C. ‘I am autism’: An advocacy video sparks protest. [Accessed 6 September 2010];Time. 2009 Available at: http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1935959,00.html.

- 18.Kaufman J. Campaign on childhood mental illness succeeds at being provocative. [cited 2010 Sep 6]. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/14/business/media/14adco.html?_r=1&ref=business.

- 19.Ne’eman A. Victory! The end of the ransom notes campaign. [cited 2010 Sep 6]. Available from: http://www.autisticadvocacy.org/modules/smartsection/item.php?itemid=23.

- 20.Wallis C. ‘I am autism’: An advocacy video sparks protest. [cited 2010 Sep 6]. Available from: http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1935959,00.html.

- 21.Ne’eman A. Testimony to the interagency autism coordinating committee. Paper presented at the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee Full Committee Meeting; 2008; Washington (DC). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blume H. Autistics, Freed from Face-to-Face Encounters, Are Communicating in Cyberspace. [Accessed 15 March 2011];The New York Times. 1997 Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/1997/06/30/business/autistics-freed-from-face-to-face-encounters-are-communicating-in-cyberspace.html?src=pm.

- 23.Jordan CJ. Evolution of autism support and understanding via the world wide web. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2010;48:220–7. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-48.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson S. Information technology & the autistic culture: Influences, Empowerment, & progression of it usage in advocacy initiatives. Paper presented at Autreat; June 2007; Johnstown, Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biever C. Web removes social barriers for those with autism. New Scientist. 2007:26–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray D, Aspinall A, Getting IT. Using information technology to empower people with communication difficulties. London: Jessica Kingsely Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senge P. The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday/Currency; 1990. [Google Scholar]