Abstract

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are important factors in gliomas since these enzymes facilitate invasion into the surrounding brain and participate in neovascularization. In particular, the gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9), and more recently MMP-25, have been shown to be highly expressed in gliomas and have been associated with disease progression. Thus, inhibition of these MMPs may represent a promising non-cytotoxic approach to glioma treatment. We report herein the synthesis and biological evaluation of a series of 4-butylphenyl(ethynylthiophene)sulfonamido-based hydroxamates. Among the new compounds tested, a promising derivative, 5a, was identified, which exhibits nanomolar inhibition of MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-25, but weak inhibitory activity towards other members of the MMP family. This compound also exhibited anti-invasive activity of U87MG glioblastoma cells at nanomolar concentrations, without affecting cell viability.

Keywords: Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors, hydroxamic acids, antiglioma agents, MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-25

1. Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) represents the most malignant of the primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors that aggressively infiltrate the surrounding brain tissue [1]. Two protease families, in particular, the serine proteases of the plasminogen activator/plasmin system and the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), seem to be implicated in tumor invasion.

MMPs are a group of structurally related zinc-dependent endopeptidases involved in the degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components and a diverse array of non-ECM proteins. Twenty three human MMPs have been identified so far, which have been classified into subgroups based on their structure and substrate specificity as follows: collagenases, gelatinases, stromelysins, matrilysins and membrane-type MMPs (MT-MMPs). Among the members of the MMP family, MMP-2 (gelatinase A) and MMP-9 (gelatinase B), are thought to play a key role in degradation of type IV collagen and gelatin, the two major components of ECM [2]. Increased expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 is reported in many human tumors, including ovarian, breast and prostate tumors, and melanoma [2]. Elevated levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 have also been found in human glioblastoma tissue samples, compared with low-grade brain tumors and normal brain tissue [3]. MMP-2, in particular, is highly expressed in gliomas and its expression, at both the mRNA and protein level, increase with tumor progression [4]. It has been shown that MMP-2 is localized in both tumor and vasculature cells, thus indicating multiple roles for this enzyme in tumor progression, including angiogenesis [5]. MMP-2 expression is also known to be associated with tumor invasion and metastasis [6]. Thus, gelatinase inhibition represents a promising non-cytotoxic approach to glioma treatment.

Unfortunately, clinical trials with MMP inhibitors (MMPIs) in cancer patients conducted over the past years failed to show a significant therapeutic response, mostly because the majority of patients enrolled had advanced metastatic disease [7]. Moreover, most clinical trials were carried out using broad-spectrum MMPIs, such as marimastat 1 (BB2516) [8], prinomastat 2 (AG3340) [9]and CGS27023A [10] 3 (Figure 1), which caused undesired side effects.

Figure 1.

Broad spectrum MMPIs used in clinical trials for cancer.

In fact, the use of broad-spectrum MMPIs in clinical trials was greatly limited by muskoloskeletal syndrome (MSS) side effects, which required a drug dose reduction and the consequent reduction of beneficial effects.

It is important to emphasize that not all MMPs contribute to tumour progression. Recently, it has been demonstrated that some MMPs are involved in innate immunity and host defence against cancer, others inhibit tumour growth and malignant transformation, and others exert antiangiogenic effects [11]. Therefore, some MMPs are considered to be anti-targets for cancer therapy [12]., Inhibition of MMP-1 and MMP-14, in particular, has been hypothesized to cause the MSS observed clinically with broad-spectrum inhibitors application [13], while MMP-8 [14]and MMP-3 [12]exhibited anti-tumor properties and, consequently, their inhibition may be counterproductive. Hence, both the side effects and the poor outcome due to wide inhibition of MMPs could be avoided by the use of selective MMP-2 and MMP-9 inhibitors. Therefore, the aim of our study was to identify new compounds to selectively inhibit the gelatinases, without significantly affecting the activity of other MMPs, which could potentially be used as anti-glioma agents.

Most MMPIs are based on a chelating moiety interacting with the catalytic zinc ion and a hydrophobic portion protruding into the hydrophobic S1′ subsite, which is a pocket situated in proximity to the catalytic zinc ion. Widely utilized zinc-binding groups (ZBGs) include: hydroxamic acids, carboxylic acids, pyrones [15]and pyrimidinetriones. The most used of these is the hydroxamate group [16] since it has excellent chelating properties. In this paper, we describe the synthesis and biological evaluation of a series of 4-butylphenyl(ethynylthiophene)sulfonamido-based hydroxamates, 4-7. Previous studies on carboxylate MMPIs [17]had shown that the presence of an elongated hydrophobic substituent in P1′ like 4-butylphenylethynylthiophene could ensure good inhibitory activity toward the gelatinases, sparing other enzymes like MMP-1, -3 and -7. In fact, the gelatinases have a deep S1′ pocket while MMP-1 and MMP-7 present a shallow pocket in the catalytic site [18]. For this reason, we chose to maintain this type of substituent in the sulfonamido moiety and to change the ZBG in an effort to improve the selectivity also over other deep-pocket MMPs, such as MMP-8 and -3. In fact, as previously shown by Cohen [19], selectivity of action against some deep-pocket MMPs can also be dependent on the nature of the ZBGs, that have different chelating geometries and different pKa values.

With the aim of increasing selectivity and based on our previous results on MMPIs [16a,20], we planned to introduce in the new inhibitors structural constraints able confer a major degree of rigidity to the system by using a combination of the appropriate chelating moiety (for instance the hydroxamate) with a rigid P1′ sulfonamide chain (like a 4-substituted phenyl(ethynylthiophene) chain), and with a lengthened P1 substituent. Therefore, starting from the un-substituted secondary sulfonamide 4, derivatives 5a-d bearing various (R) aryl-alkyl chains in position α of the hydroxamate were synthesized according to the hypothesis that the selectivity profile could be also affected by the presence and structure of the α-chain (P1 group), as previously observed by Hanessian et al. [21]. The scaffold was further rigidified by introducing α-chains fused with the sulfonamido moiety, thus affording cyclic compounds 6 and 7 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

a) Evolution of the new 4-butylphenylethynyl-thiophene derivatives scaffold. b) Schematic representation of the new compounds substituents (P1′, P1), interacting with the principal binding pockets of MMPs (S1′, S1).

The effects of these substitutions on MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity and selectivity were examined in vitro using a fluorometric assay on purified enzymes. The compounds 5a-d, 6, 7 were then tested for their ability to inhibit in vitro invasion of U87MG glioma cells through matrigel and to inhibit cell growth. Finally, these compounds were evaluated as inhibitors for MMP-25, a recently discovered target in glioma progression.

2. Chemistry

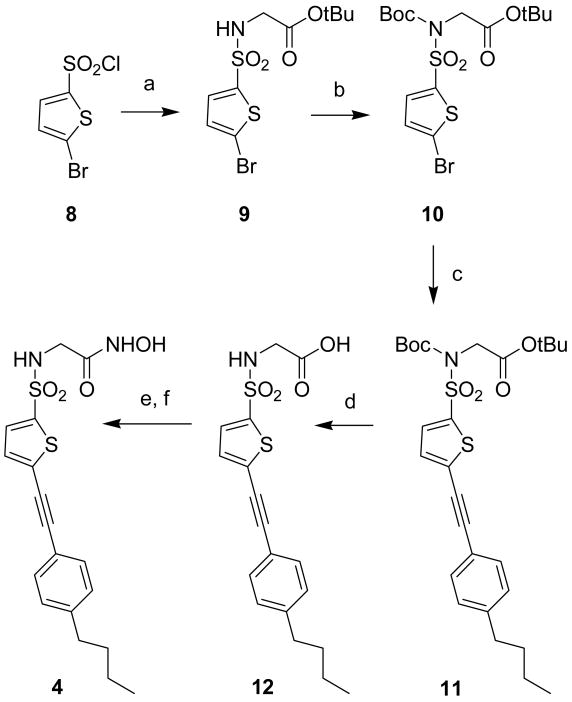

Scheme 1 shows the synthesis of compound 4. 5-bromothiophene-2-sulfonyl chloride 8 was converted into sulfonamide 9 by reaction with glycine tert-butyl ester hydrochloride in water and dioxane in the presence of triethylamine. Compound 9 was then protected as a Boc-sulfonamide by treatment with di-(tert-butyl)dicarbonate in CH2Cl2 using 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) as acylation catalyst [22]. The N-protected intermediate 10 was submitted to the Sonogashira reaction [23,24] in the presence of Pd(II), CuI, triphenylphosphine and triethylamine to afford the acetylenic derivative 11. Acid hydrolysis with TFA allowed to deprotect the carboxylic acid and the sulfonamidic nitrogen in a single step. Finally, the condensation of carboxylate 12 with O-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)hydroxylamine in the presence of N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) followed by acid cleavage yielded the desired hydroxamate 4 [25].

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) glycine tert-butyl ester HCl, Et3N, H2O, dioxane; (b) (Boc)2O, Et3N, DMAP, CH2Cl2; (c) 1-butyl-4-ethynyl-benzene, CuI, Et3N, Pd(Ph3)2Cl, PPh3, THF, 70 °C; (d) TFA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C; (e) TBDMSiONH2, EDC, CH2Cl2; (f) TFA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C.

For the synthesis of the α-substituted compounds 5a-d and 6, 7, an improved shorter route was followed (Scheme 2 and 3). Carboxylates 13a-d and 18, 19, obtained by reaction of 5-bromothiophene-2-sulfonylchloride with the appropriate commercial non-natural amino acid, were first converted into protected hydroxamates 14a-d and 20, 21 by condensation with O-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)hydroxylamine (THP-hydroxylamine) [26] in the presence of EDC and then submitted to the Sonogashira coupling. The reaction conditions were optimized and the reaction was faster with improved yields with the use of microwaves [27,28]. After mild hydrolysis with 4N HCl [26], tetrahydropyranyl intermediates 15a-d and 22, 23 afforded hydroxamates 5a-d and 6, 7.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (i) appropriate D-amino acid, Et3N, H2O, dioxane; (ii) THPONH2, HOBT, NMM, EDC, DMF; (iii) 1-butyl-4-ethynyl-benzene, CuI, Et3N, Pd(Ph3)2Cl, PPh3, THF, microwaves, 300 W, 60 °C, 10 min; (iv) 4N HCl, dioxane, MeOH.

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 5-bromothiophene-2-sulfonyl chloride, Et3N, H2O, dioxane; (b) THPONH2, HOBT, NMM, EDC, DMF; (c) 1-butyl-4-ethynyl-benzene, CuI, Et3N, Pd(Ph3)2Cl, PPh3, THF, microwaves, 300 W, 60 °C, 10 min; (d) 4N HCl, dioxane, MeOH.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. MMPs inhibition

The newly synthesized hydroxamates 4-7 were tested in vitro for their ability to inhibit human recombinant MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-8, MMP-9, and MMP-14 by a fluorometric assay, which uses a fluorogenic peptide [29]as the substrate. The broad-spectrum inhibitor 3 was taken as reference compound (Table 1).

Table 1.

In vitroa activity (IC50 nM values) of 4-butylethynylthiophene derivatives 4, 5a-d, 6, 7 and the reference compound 3.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R | MMP-1 | MMP-2 | MMP-3 | MMP-8 | MMP-9 | MMP-14 | MMP-25 |

| 4 | H | 13000 | 1.5 | 46 | 200 | 79 | 700 | 34 |

| 5a |

|

4800 | 2.3 | 180 | 490 | 63 | 2100 | 38 |

| 5b |

|

37000 | 4.0 | 84 | 440 | 50 | 6600 | 340 |

| 5c |

|

2300 | 6.0 | 93 | 280 | 77 | 1700 | 76 |

| 5d |

|

56000 | 17 | 320 | 1700 | 650 | 23000 | 220 |

| 6 | 21000 | 2.5 | 38 | 500 | 21 | 1600 | 170 | |

| 7 | 6700 | 1.3 | 11 | 30 | 4.3 | 112 | 3.4 | |

|

| ||||||||

| 3 | 56 | 25 | 16 | 7.7 | 4.8 | 23 | 1.5 | |

Enzymatic activity data are mean values for three independent experiments performed in duplicate. SD were within ±10%.

As can be seen from Table 1, the introduction of various (R) aryl-alkyl chains in α position of the hydroxamate did not substantially affect activity toward MMP-2 compared with the un-substituted derivative 4. In fact, all α-substituted compounds displayed nanomolar inhibitory activity for MMP-2 (IC50 values between 1.3 and 17 nM) comparable to compound 4 activity (IC50 = 1.5 nM). As expected, these data confirmed that the inhibitory activity toward MMP-2 was mainly determined by the P1′ group, a 4-butylphenylethynylthiophene substituent, which is common to all compounds. On the contrary, the selectivity profile was greatly affected by the presence of the α-chain (P1 group). The cyclic derivatives 6 and 7, bearing a thiazolidine and a tetrahydroisoquinoline ring respectively, were poorly selective over the anti-target MMPs (MMP-3 and MMP-8)., The tetrahydroisoquinoline derivative 7, in particular, was the least selective of the series, exhibiting nanomolar activity toward all tested enzymes, except MMP-1. Among the non-cyclic inhibitors, the benzyloxy benzyl derivative 5a was the most active toward both MMP-2 and MMP-9 (IC50 = 2.3 nM and 63 nM, respectively), showing the highest selectivity over MMP-1, -3, -8 and -14. This compound exhibited a 2000-fold selectivity for MMP-2 over MMP-1, a 1000-fold selectivity over MMP-14, a 200-fold selectivity over MMP-8 and a 80-fold selectivity over MMP-3. This very good selectivity is probably due to the presence of an elongated α-chain compared to the other derivatives. The benzothienyl derivative 5d was the weakest inhibitor of MMPs, on all tested enzymes.

3.2. Molecular Modeling

Inhibitor 5a was docked into the MMP-2 active site using the crystal structure available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB code: 1QIB [30]). The calculation was performed with the aid of Glide 5.5 in the extra-precision mode (XP) while Glidescore was used for poses scoring. The docking experiment resulted in only one pose, in which the hydroxamic acid moiety coordinates the catalytic zinc atom in a bidentate fashion, and establishes an H-bond with the A165 carbonyl oxygen (Figure 3). The sulfonamide moiety of 5a forms a bifurcated H-bond with L164 and A165 backbone NH and allows the 4-butylphenylethynylthiophene moiety to plunge deeply into the large S1′-specificity pocket. In here, the butylphenyl ring is engaged in multiple hydrophobic interactions with L197, A217, L218, A220, T227, F232 and L234 side chains. The ethynyl group is found sandwiched between Y223 and H201, whereas the thiophene moiety is flanked by lipophilic residues such as L164 and V198. On the other side of the molecule, the benzyloxy-benzyl branch reaches out for the S3 pocket where the terminal phenyl ring forms aromatic-aromatic interactions with F168 and Y155 side chains. Clearly, all these interactions endow 5a with a low nanomolar inhibitory activity toward MMP-2. Looking at the SARs herein developed, it is clear that MMP-2 can tolerate extremely different P1 groups ranging from long and flexible substituents, such as the benzyloxy-benzyl (5a), to relatively long and rigid groups, such as the benzophenone (5b) or to backbone-fused substituents (6-7) without a substantial difference in IC50. However, the P1 group seems to be useful in increasing the inhibitors selectivity at least toward some MMPs. For example, with respect to 4, compound 5a is less active toward MMP-3, -8, and -14 and, at least for MMP-8, and -14, this effect could be ascribed to the fact that these MMPs have a Ser and a Thr instead of the MMP-2-Y155, respectively. Moreover, from Table 1, it is also evident that compounds 4 and 7 are the most active toward MMP-2, but generally speaking they are also the least selective. This lack of selectivity could be attributed to a better chance for the hydroxamic acid to find the most favourable chelating geometry, either when only a hydrogen is present in the alpha position (4), or when there is a proper backbone cyclization, respectively (6-7). Compound 5b has a slightly higher IC50 with respect to 5a and this seems to be due to a greater rigidity of the P1 group. In fact, in order to preserve the interaction pattern with the S3 cavity, the benzophenone moiety adopts an energetically unfavourable conformation. On the other hand, 5c and 5d, both possessing a P1 group not long enough to interact with F168 and Y155 S3 pocket residues, are less active toward MMP-2 than 5a. Of note, the indole ring of 5c can be superimposed to the first benzene of the benzyloxy-benzyl branch of 5a, whereas the pyrrole establishes a π-interaction with the H211. Substitution of the NH group with sulfur in 5d induces a certain clash with the aforementioned residue side chain which results in a change in the thiophene position in the active site and further loss of activity. Moreover, according to the binding mode found for 5c, the P1 group seems to be partially exposed to the solvent and, in this environment, the indole ring (5c) is certainly more suitable than the benzothiophene ring.

Figure 3.

Docked conformation of 5a (cyan) in the MMP-2 active site shown as an orange ribbon. The Zn(II) ion has been represented as violet sphere. Interacting residues are displayed as orange sticks. H-Bonds are displayed as blue lines.

3.3. Effect of MMPIs on U87MG glioma cell invasion and viability

We evaluated the ability of the newly synthesized gelatinase inhibitors 4-7 and the reference compound 3 to inhibit invasion of U87MG cells through Matrigel (Table 2). The number of invading cells, quantified by counting the cells on the lower surface of the transwell membrane after fixing with p-formaldehyde and staining with crystal violet, showed a marked reduction (p<0.0001) after treatment for 24 h, with 5 nM of inhibitor. This effect was not due to MMPI cytotoxicity because, as shown in Table 2, at 5 nM the inhibitors showed no effect on glioblastoma cell viability (p>0.05), as ascertained by the Trypan Blue exclusion assay, over a 24 h period.

Table 2.

Effect of compounds 4-7 and reference compound 3 on U87MG glioblastoma cell viability and invasion through Matrigel.

| Compd | Dead Cells (%) | Inhibition of Cell Invasion (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| DMSO | 10.0±1.04 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 11.5±0.20 | 39.5±1.55 |

| 5a | 12.3±0.44 | 42.6±0.97 |

| 5b | 9.38±2.77 | 27.5±1.66 |

| 5c | 6.80±1.24 | 48.4±2.80 |

| 5d | 14.4±0.07 | 34.0±1.45 |

| 6 | 17.8±1.28 | 16.0±0.60 |

| 7 | 13.6±4.15 | 35.9±1.45 |

|

| ||

| 3 | 10.8±1.81 | 28.3±0.40 |

Percent inhibition of cell invasion observed at 5 nM of compound, corrected for cell death by subtracting the percentage of dead cells which, on average, did not exceed ∼15%, as shown in column 2.

Taken together, these results identify a new series of MMPIs with anti-invasive activity towards U87MG glioblastoma cells in the nanomolar range, without causing cytotoxic effects. Furthermore, all compounds, except the cyclic derivative 6, were more active than the broad-spectrum inhibitor 3. As shown in Figure 4A and 5, compounds 5c and 5a, in particular, were the most effective invasion inhibitors (48 and 43%, respectively). As depicted in figure 4B, compound 5a showed a dose dependent effect on cell invasion, at concentrations of 1, 5, 25, 125 nM, yielding a IC50 =12 nM. These data suggest that MMP-2 is not the only enzyme implicated in U87MG cell invasion through Matrigel, since all the compounds tested showed similar inhibitory activity towards MMP-2 (Table 1) but yet exhibited widely different invasion inhibitory activities (ranging from 16 to 48% inhibition at 5 nM).

Figure 4.

Effect of MMPIs on U87MG cell invasion. (A) Treatment of cells with compounds 4-7, and the reference compound 3 (5 nM), for 24 h reduced glioma cell invasion. (B) Dose-dependent cell invasion inhibition following treatment of compound 5a for 24 h. The IC50 value represents the compound concentration that caused a 50%reduction of tumor cell invasion. The results are expressed as the mean value of the percentage of cell invasion inhibition after treatment with the MMPIs compared with untreated control cells. *** = statistically significant result (p<0.0001).

Figure 5.

Effect of 5a, 5c and 3 on U87MG cell invasion. Cell invasion was ascertained using the Matrigel basement membrane transwell assay, as described in the Experimental Section. Photographs of the invasive cells treated with vehicle (DMSO), compounds 5a, 5c and the reference compound 3, at 200× magnification.

3.4. MMP-25 inhibition

The newly synthesized compounds 4, 5a-d, 6, 7 and the reference compound 3 were also tested on human recombinant MT6-MMP (known as MMP-25) by fluorometric assay. This enzyme is a membrane-type MMP that is anchored to the plasma membrane via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) moiety, and is highly expressed in human neutrophils [31]. MMP-25 can degrade various extracellular matrix components, including type IV collagen, gelatin, fibrin, fibronectin, and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan [32]. The body of work on GPI-MT-MMPs today is still surprisingly limited when compared to other MT-MMPs. Recently however, elevated MMP-25 mRNA expression was found in several human cancers including brain (anaplastic astrocytomas and glioblastomas) [33], colon [32] and prostate cancer. In gliomas, expression of MMP-25 mRNA was suggested to contribute to disease progression [34]. Thus, we decided to evaluate the inhibitory activity of the compounds toward this enzyme, to ascertain whether the anti-invasive effect on U87MG cells could be correlated with MMP-25 inhibition. As reported in Table 1, compounds 5a and 5c, which displayed the highest invasion inhibitory activity were potent MMP-25 inhibitors (IC50 = 38 and 76 nM, respectively). However, compound 6 which exhibited the worst anti-invasive activity displayed only a slightly lower binding affinity (IC50 = 170 nM). Moreover, compounds with very similar anti-invasive activity on cells, like 5b and 3, exhibited a very different inhibitory potency toward MMP-25 (IC50= 340 and 1.5 nM, respectively). Thus, similarly to MMP-2, there is not direct correlation between MMP-25 inhibition and anti-invasive activity of U87MG glioblastoma cells through Matrigel, for the MMPIs herein reported. Of note, the MMP-25 sensitivity to this class of inhibitors resembles that of the gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) as opposed to the collagenases including MT1-MMP, lending credit to the hypothesis that the GPI-anchored MT-MMPs exhibit unique inhibitor sensitivities, which may correlate with their physiological functions. Further studies are needed to better ascertain the role of MMP-25 in glioma progression.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a series of new 4-butylphenyl(ethynylthiophene)sulfonamido-based hydroxamate inhibitors selective for MMP-2, relative to MMP-1 and MMP-14, was designed, synthesized and tested for their ability to inhibit glioma cell invasion in vitro. Among these compounds, a very promising derivative was identified (5a) with nanomolar activity for MMP-2 and good selectivity over the anti-targets MMP-8 and MMP-3, by fluorometric assay on isolated enzymes. The effect of these new compounds on cell viability and invasion through Matrigel was evaluated using human U87MG glioblastoma cells. No cytoxicity was detected in the nanomolar range (5 nM) and compound 5a inhibited cell invasion, with a IC50 = 12 nM. This compound exhibited nanomolar inhibitory activity towards MMP-25, a GPI-anchored MMP that may be involved in glioma progression. After the disappointing clinical results of broad-spectrum MMPIs in cancer therapy of the last years, we hope that our findings, and those of others [35], will contribute to accelerate the discovery of novel and more selective MMPIs with potent anti-invasive activity to be used individually or in combination with cytotoxic compounds [36,26]. The use of more specific and effective inhibitors should allow a reduction of the doses necessary to have therapeutic efficacy without the side effects typically associated with broad-spectrum MMPIs.

5. Experimental section

5.1. Chemistry

Melting points were determined on a Kofler hotstage apparatus and are uncorrected. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were determined with a Varian Gemini 200 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million downfield from tetramethylsilane and referenced from solvent references. Coupling constants J are reported in hertz; 13C NMR spectra were fully decoupled. The following abbreviations are used: singlet (s), doublet (d), triplet (t), double-doublet (dd), broad (br) and multiplet (m). Where indicated, the elemental compositions of the compounds agreed to within ±0.4%of the calculated value. Chromatographic separations were performed on silica gel columns by flash column chromatography (Kieselgel 40, 0.040–0.063 mm; Merck) or using ISOLUTE Flash Si II cartridges (Biotage). Reactions were followed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on Merck aluminum silica gel (60 F254) sheets that were visualized under a UV lamp and hydroxamic acids were visualized with FeCl3 aqueous solution. Evaporation was performed in vacuo (rotating evaporator). Sodium sulfate was always used as the drying agent. Microwave-assisted reactions were run in a CEM Discover LabMate microwave synthesizer. Commercially available chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. D-amino acids were purchased from Bachem. Compound 3 was synthesized as reported in literature [37].

5.1.1. tert-Butyl 2-(5-bromothiophene-2-sulfonamido)acetate (9)

5-bromothiophene 2-sulfonyl chloride 8 (500 mg, 2.21 mmol) was added to a solution of glycine tert-butyl ester hydrochloride (372 mg, 2.21 mmol) in H2O (2.20 mL) and dioxane (2.20 mL) containing Et3N (0.61 mL, 4.42 mmol). The reaction was stirred overnight at room temperature, then dioxane was evaporated and the residue was taken up with EtOAc and washed (x3) with water and brine. Organic layers were then collected, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated in vacuo. The crude was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 8:1) and a yellow solid was obtained (568 mg, 1.77 mmol, 80%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.43 (s, 9H); 3.78 (d, J=5.3 Hz, 2H); 5.14 (t, J=5.3 Hz, 1H); 7.08-7.10 (m, 1H); 7.38-7.40 (m, 1H).

5.1.2. tert-Butyl 2-(5-bromo-N-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)acetate (10)

tert-Butyl ester 9 (560 mg, 1.75 mmol) was dissolved in dry CH2Cl2 (2.18 mL) and DMAP (21.4 mg, 0.175 mmol) and Et3N (0.27 mL, 1.92 mmol) were added. A solution of di-(tert-butyl)dicarbonate (439 mg, 2.01 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (3.04 mL) was added dropwise to the tert-butyl ester solution and the mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The solution was diluted with CH2Cl2, and treated with HCl 1N, water and brine. Organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated in vacuo to give a yellow oil (648 mg, 1.54 mmol, 88%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ:1.45 (s, 18H); 4.41 (s, 2H); 7.06-7.08 (m, 2H); 7.61-7.63 (m, 1H).

5.1.3. tert-Butyl 2-(N-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-5-((4-butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)acetate (11)

To a solution of 10 (400 mg, 0.95 mmol) in dry THF (19 mL), 1-butyl-4-ethynyl-benzene (0.2 mL, 1.14 mmol), Et3N (0.26 mL, 1.9 mmol), triphenylphosphine (12.6 mg, 0.048 mmol), copper(I) iodide (9.14 mg, 0.048 mmol), and dichlorobis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(II) (33.4 mg, 0.048 mmol) were added. The mixture was stirred refluxing at 70 °C under Ar atmosphere for 24h, then it was diluted with water and extracted with EtOAc. Organic phases were washed with HCl 1N, brine and with a saturated solution of NaHCO3, dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (n-hexane/ EtOAc 14:1) using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge to yield a brown oil (131 mg, 0.25 mmol, 26%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 0.93 (t, J=6.9Hz, 3H), 1.33-1.41 (m, 2H); 1.40 (s, 18H), 1.53-1.68 (m, 2H), 2.59 (t, J=7.8 Hz, 2H), 3.32 (br s, 2H), 7.17-7.23 (m, 3H), 7.42-7.46 (m, 2H), 7.55 (d, J=4.0 Hz, 1H).

5.1.4. 2-(5-((4-Butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-hydroxyacetamide (4)

tert-Butyl ester 11 (330 mg, 0.62 mmol) was dissolved in freshly distilled CH2Cl2 (4.82 mL) and TFA (2.71 mL, 35.24 mmol) was added dropwise to the chilled solution. The reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 5h, the solvent was evaporated and the crude product was triturated with Et2O. The product was used in the next step without further purification. Carboxylate 12 (218 mg, 0.58 mmol) was suspended in dry CH2Cl2 (15 mL) and O-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)hydroxylamine (85 mg, 0.58 mmol) and 1-[3-(Dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethyl carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (166 mg, 0.87 mmol) were added. The reaction was stirred at room temperature overnight, diluted with CH2Cl2, washed with water, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (n-hexane/EtOAc 5:2) to give the pure O-silyl-intermediate as a yellow oil (87.3 mg, 0.17 mmol, 30%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 0.17 (s, 6H); 0.92 (t, J=6.9Hz, 3H); 0.94 (s, 9H); 1.29-1.40 (m, 2H); 1.52-1.67 (m, 2H); 2.62 (t, J=7.9Hz, 2H); 3.71 (br s, 1H); 3.96 (br s, 1H); 6.00 (br s, 1H); 7.15-7.19 (m, 3H); 7.40-7.44 (m, 2H); 7.48-7.50 (m, 2H); 8.835 (br s, 1H).

TFA (0.75 mL, 9.79 mmol) was added dropwise to a 0 °C solution of O-silyl-intermediate (87 mg, 0.17 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (2 mL), and the reaction was stirred at 0 °C for 5h. Trituration with Et2O and further purification by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 1:12) gave the pure hydroxamate 4 as a white solid (33.4 mg, 0.09 mmol, 50%yield). Mp 145-147 °C; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 0.89 (t, J=7.14 Hz, 3H); 1.22-1.33 (m, 2H); 1.48-1.62 (m, 2H); 2.62 (t, J=7.7 Hz, 2H); 3.45 (s, 2H); 7.26-7.30 (m, 2H); 7.42-7.44 (m, 1H); 7.48-7.52 (m, 2H); 7.54-7.56 (m, 1H); 8.94 (br s, 1H); 10.62 (br s, 1H).

13C-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 14.3, 22.3, 33.4, 35.7, 41.2, 86.5, 92.7, 120.1, 122.2, 127.0, 127.8, 132.2, 138.3, 166.2. Elemental Analysis for C18H20N2O4S2: Calculated: %C, 55.08; %H, 5.14; %N, 7.14, Found %C, 55.13; %H, 5.17; %N, 7.10.

5.1.5. General procedure for the synthesis of carboxylates 13a-d, 18, 19

5-Bromothiophene-2-sulfonylchloride (1g, 4.43 mmol) was added to a solution of the appropriate non-natural commercial amino acid (4.43 mmol) in H2O (4.43 mL) and dioxane (13.3 mL) containing Et3N (1.24 mL, 8.86 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight, the dioxane was evaporated and the residue was treated with EtOAc and washed with HCl 1N and brine. Organic layers were then collected, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated in vacuo.

5.1.6. (R)-3-(4-(Benzyloxy)phenyl)-2-(5-bromothiophene-2-sulfonamido)propanoic acid (13a)

The title compound was prepared from H-D-Tyr(Bzl)-OH following the general procedure. The crude product was triturated with Et2O and n-hexane to yield carboxylate 13a as a yellow solid (56%yield). 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 2.90 (dd, J1=4.95 Hz, J2=13.55 Hz, 2H); 3.35-3.40 (m, 1H); 5.04 (s, 2H); 6.80-6.84 (m, 2H); 7.04-7.08 (m, 2H); 7.25-7.46 (m, 7H).

5.1.7. (R)-3-(4-Benzoylphenyl)-2-(5-bromothiophene-2-sulfonamido)propanoic acid (13b)

The title compound was prepared from H-p-Bz-D-Phe-OH following the general procedure. The crude product was triturated with Et2O and n-hexane to yield carboxylate 13b as a yellow solid (28%yield). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 3.01-3.26 (m, 1H); 3.26-3.35 (m, 1H), 4.25-4.37 (m, 1H); 7.10-7.12 (m, 1H); 7.25-7.27 (m, 1H); 7.33-7.38 (m, 1H); 7.42-7.46 (m, 2H); 7.53 (t, J=1.83 Hz, 1H); 7,57-7.64 (m, 2H); 7.67-7.71 (m, 2H); 7.76-7.81 (m, 2H).

5.1.8. (R)-2-(5-Bromothiophene-2-sulfonamido)-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid (13c)

The title compound was prepared from H-D-Trp-OH following the general procedure. The crude product was triturated with Et2O and n-hexane and further purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (CHCl3/MeOH 9:1) to give 13c as a green oil (71%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 3.16-3.41 (m, 2H); 4.28-4.40 (m, 1H); 5.23 (d, J=8.23 Hz, 1H); 5.49 (br s, 1H); 6.77 (d, J=3.67 Hz, 1H); 6.97 (s, 1H); 7.08-7.21 (m, 3H); 7.35 (d, J=7.87 Hz, 1H); 7.50 (d, J=7.87 Hz, 1H); 8.05 (s, 1H).

5.1.9. (R)-3-(Benzo[b]thiophen-3-yl)-2-(5-bromothiophene-2-sulfonamido)propanoic acid (13d)

The title compound was prepared from H-β-(3-Benzothienyl)-D-Ala-OH following the general procedure. Clear oil (76%yield). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 3.18-3.30 (m, 1H); 3.39-3.51 (m, 1H); 4.29-4.40 (m, 1H); 6.85 (d, J=4.0 Hz, 1H); 7.05 (d, J=4.0 Hz, 1H); 7.37-7.43 (m, 2H); 7.46 (s, 1H); 7.78-7.83 (m, 1H); 7.90-7.95 (m, 1H).

5.1.10. (R)-3-(5-Bromothiophen-2-ylsulfonyl)thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (18)

The title compound was prepared from D-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid 16 following the general procedure. The crude product was triturated with Et2O and n-hexane to furnish 18 as a yellow solid (55%yield). 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 3.11-3.15 (m, 2H); 4.45 (d, J=10.5 Hz, 1H); 4.72 (d, J=10.5 Hz, 1H); 4.77-4.80 (m, 1H); 7.48 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H); 7.74 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H).

5.1.11. (R)-2-(5-Bromothiophen-2-ylsulfonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (19)

The title compound was prepared from D-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid 17 following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 1:1) to give 19 as a yellow oil (71%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 3.21 (d, J=4 Hz, 2H); 4.61 (dd, J1=15.2 Hz, J2=27 Hz, 2H); 4.96 (t, J=5 Hz, 1H); 7.00 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H); 7.07-7.24 (m, 4H); 7.33 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H).

5.1.12. General procedure for the synthesis of 2-(5-bromothiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)acetamides 14a-d, 20, 21

Carboxylates 13a-d, 18, 19 (1.46 mmol) were dissolved in dry DMF (2.21 mL) and O-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)hydroxylamine (530 mg, 4.53 mmol), N-methylmorpholine redistilled (0.48 mL, 4.38 mmol), hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT) (237 mg, 1.75 mmol), and 1-[3-(Dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethyl carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (392 mg, 2.04 mmol) were added under N2 atmosphere. After stirring for 2 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc and washed with water, saturated solution of NaHCO3, and brine. The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo.

5.1.13. (2R)-3-(4-(Benzyloxy)phenyl)-2-(5-bromothiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)propanamide (14a)

The title compound was prepared from carboxylic acid 13a following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 3:1) to yield a yellow foaming oil (74%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.58 (br s, 4H); 1.78 (br s, 2H); 2.86-3.09 (m, 2H); 3.55-3.60 (m, 1H); 3.72-3.90 (m, 2H); 4.73-4.83 (m, 1H); 5.04 (s, 2H); 5.22 (br s, 1H); 6.83-6.88 (m, 2H); 6.95-6.99 (m, 3H); 7.15-7.19 (m, 1H); 7.36-7.42 (m, 5H); 8.69 (br s, 1H).

5.1.13. (2R)-3-(4-Benzoylphenyl)-2-(5-bromothiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)propanamide (14b)

The title compound was prepared from carboxylic acid 13b following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 2:1) to furnish a yellow oil (67%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.58 (br s, 4H); 1.78 (br s, 2H); 3.01-3.24 (m, 2H); 3.55-3.63 (m, 1H); 3.78-3.92 (m, 1H); 3.98-4.08 (m, 1H); 4.79 (br s, 1H); 5.34 (br s, 1H); 6.99 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H)); 7.18-7.25 (m, 3H); 7.45-7.64 (m, 3H); 7.70-7.81 (m, 4H); 8.69 (br s, 1H).

5.1.14. (2R)-2-(5-Bromothiophene-2-sulfonamido)-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)propanamide (14c)

The title compound was prepared from carboxylic acid 13c following the general procedure. Yellow foaming solid (95%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.56 (br s, 4H); 1.77 (br s, 2H); 3.11-3.35 (m, 2H); 3.47-3.53 (m, 1H); 3.72-3.90 (m, 1H); 4.02 (br s, 1H); 4.70-4.80 (m, 1H); 5.21 (br s, 1H); 6.75-6.79 (m, 1H); 7.02-7.22 (m, 4H); 7.34-7.38 (m, 1H); 7.43-7.47 (m, 1H); 8.10 (br s, 1H); 8.69 (br s, 1H).

5.1.15. (2R)-3-(Benzo[b]thiophen-3-yl)-2-(5-bromothiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)propanamide (14d)

The title compound was prepared from carboxylic acid 13d following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 5:2) to furnish a yellow oil (83%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.57 (br s, 4H); 1.79 (br s, 2H); 3.11-3.27 (m, 1H); 3.42-3.69 (m, 2H); 3.62-3.93 (m, 1H); 3.99-4.09 (m, 1H); 4.83 (br s, 1H); 5.29 (br s, 1H); 6.62-6.66 (m, 1H); 6.96-7.02 (m, 1H); 7.21 (s, 1H); 7.36-7.40 (m, 2H); 7.62-7.68 (m, 1H); 7.82-7.98 (m, 1H); 8.82 (br s, 1H).

5.1.16. (4R)-3-(5-Bromothiophen-2-ylsulfonyl)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)thiazolidine-4-carboxamide (20)

The title compound was prepared from carboxylic acid 18 following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 3:1) to furnish a foaming clear oil (83%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.62 (br s, 4H); 1.83 (br s, 2H); 2.63 (s, 1H); 2.80-2.93 (m, 1H); 3.42-3.52 (m, 1H); 3.64-3.70 (m, 1H); 3.93-4.06 (m, 1H); 4.42-4.62 (m, 1H); 4.97-5.01 (m, 1H); 7.16 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H); 7.42 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H); 9.27 (s, 1H).

5.1.17. (3R)-2-(5-Bromothiophen-2-ylsulfonyl)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide (21)

The title compound was prepared from carboxylic acid 19 following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 3:1) to furnish a clear oil (70%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.58 (br s, 4H); 1.73 (br s, 2H); 2.75-2.85 (m, 1H); 3.21-3.31 (m, 1H); 3.49-3.60 (m, 1H); 3.85-3.92 (m, 1H); 4.46-4.57 (m, 2H); 6.96-7.01 (m, 1H); 7.11-7.24 (m, 4H); 7.26-7.28 (m, 1H); 9.09 (br s, 1H).

5.1.18. General Procedure for the synthesis of 2-(5-((4-butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)acetamides 15a-d, 22, 23

A mixture of the appropriate 5-bromo-derivative 14a-d, 20, 21 (0.37 mmol), 1-butyl-4-ethynyl-benzene (0.08 mL, 0.45 mmol), Et3N (0.1 mL, 0.74 mmol), triphenylphosphine (4.85 mg, 0.019 mmol), copper(I) iodide (3.52 mg, 0.019 mmol), and dichlorobis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(II) (4.85 mg, 0.019 mmol) in dry THF (2.96 mL) was submitted to microwave irradiation at 60 °C for 10 min (power 300W, 250 psi). The reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted with EtOAc. The organic phase was washed with HCl 1N, brine, NaHCO3 saturated solution, dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo.

5.1.19. (2R)-3-(4-(Benzyloxy)phenyl)-2-(5-((4-butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)propanamide (15a)

The title compound was prepared from the 5-bromo-derivative 14a following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 5:2) to furnish a brown solid (25%yield). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 0.93 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.26-1.45 (m, 2H); 1.54-1.67 (m, 8H); 2.66 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 2H); 2.96-3.06 (m, 2H); 3.46-3.63 (m, 1H); 3.83-3.99 (m, 1H); 4.73 (br s, 1H); 5.09 (s, 2H); 4.74-4.77 (m, 1H); 6.85-6.91 (m, 2H); 7.09-7.47 (m, 14H); 10.39 (br s, 1H).

5.1.20. (2R)-3-(4-Benzoylphenyl)-2-(5-((4-butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)propanamide (15b)

The title compound was prepared from the 5-bromo-derivative 14b following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 5:2) to furnish a yellow oil (66%yield). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 0.93 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.26-1.40 (m, 2H); 1.54-1.68 (m, 8H); 2.66 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 2H); 2.94-3.06 (m, 1H); 3.12-3.24 (m, 1H); 3.45-3.58 (m, 1H); 3.80-3.98 (m, 1H); 4.17-4.24 (m, 1H); 4.74-4.77 (m, 1H); 7.19-7.27 (m, 3H); 7.37-7.71 (m, 10H); 7.75-7.78 (m, 2H); 10.43 (br s, 1H).

5.1.21. (2R)-2-(5-((4-Butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)propanamide (15c)

The title compound was prepared from the 5-bromo-derivative 14c following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 2:1) to furnish a yellow oil (55%yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 0.93 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.29-1.46 (m, 6H); 1.54-1.76 (m, 4H); 2.63 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 2H); 3.21-3.25 (m, 2H); 3.42-3.56 (m, 1H); 3.72-3.82 (m, 1H); 4.74-4.77 (m, 1H); 5.34 (br s, 1H); 6.89-6.93 (m, 1H); 7.02 (s, 1H); 7.08-7.49 (m, 9H); 8.16 (br s, 1H); 8.79 (br s, 1H).

5.1.22. (2R)-3-(Benzo[b]thiophen-3-yl)-2-(5-((4-butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)propanamide (15d)

The title compound was prepared from the 5-bromo-derivative 14d following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 5:2) to furnish a yellow oil (54%yield). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 0.93 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.30-1.42 (m, 2H); 1.52-1.66 (m, 8H); 2.67 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 2H); 3.14-3.25 (m, 1H); 3.32-3.43 (m, 1H); 3.47-3.59 (m, 1H); 3.82-3.98 (m, 1H); 4.17-4.29 (m, 1H); 4.76 (br s, 1H); 7.02 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H); 7.29-7.52 (m, 9H); 7.74-7.83 (m, 1H); 7.88-7.96 (m, 1H); 10.44 (br s, 1H).

5.1.23. (4R)-3-(5-((4-Butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophen-2-ylsulfonyl)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)thiazolidine-4-carboxamide (22)

The title compound was prepared from the 5-bromo-derivative 20 following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 3:1) to furnish a yellow oil (50%yield). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 0.92 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.30-1.45 (m, 2H); 1.57-1.74 (m, 8H); 2.67 (t, J=7.7 Hz, 2H); 2.97-3.07 (m, 2H); 3.25-3.33 (m, 1H); 3.49-3.55 (m, 1H); 3.99-4.10 (m, 1H); 4.70-4.84 (m, 2H); 4.98 (br s, 1H); 7.29-7.32 (m, 2H); 7.44 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H); 7.48-7.53 (m, 2H); 7.76 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H); 10.67 (s, 1H).

5.1.24. (3R)-2-(5-((4-Butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophen-2-ylsulfonyl)-N-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide (23)

The title compound was prepared from the 5-bromo-derivative 21 following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 3:1) to furnish a yellow oil (62%yield). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 0.92 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.26-1.40 (m, 4H); 1.51-1.66 (m, 6H); 2.60 (s, 2H); 2.66 (t, J=7.7 Hz, 2H); 3.07-3.12 (m, 1H); 3.42-3.57 (m, 1H); 3.82-3.98 (m, 1H); 4.67-4.82 (m, 3H); 7.15-7.19 (m, 3H); 7.27-7.30 (m, 2H); 7.45-7.49 (m, 2H); 7.56-7.59 (m, 1H); 10.48 (br s, 1H).

5.1.25. General procedure for the synthesis of 2-(5-((4-butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-hydroxyacetamides 5a-d, 6, 7

Protected Hydroxamates 15a-d, 22, 23. (0.33 mmol) were dissolved in dioxane (0.6 mL) and a solution of HCl 4N (5.94 mL) was added dropwise followed by MeOH (1.32 mL). After stirring for 30 min, the reaction was evaporated in vacuo.

5.1.26. (R)-3-(4-(Benzyloxy)phenyl)-2-(5-((4-butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-hydroxypropanamide (5a)

The title compound was prepared from the THP-protected hydroxamate 15a following the general procedure. The crude product was triturated with Et2O and n-hexane to furnish a light brown solid (99%yield). Mp 201-203 °C; 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 0.92 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.26-1.45 (m, 2H); 1.53-1.68 (m, 2H); 2.65 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 2H); 3.00 (dd, J1=5.9 Hz, J2=7.9 Hz, 2H); 3.96-4.08 (m, 1H); 5.09 (s, 2H); 6.84-6.88 (m, 2H); 7.07-7.47 (m, 13H); 8.11 (br s, 1H); 10.39 (br s, 1H). 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 14.45, 23.23, 34.47, 36.41, 57.90, 70.65, 81.73, 115.64, 128.58, 128.75, 129.46, 129.90, 131.50, 132.57, 132.70, 132.90, 138.71, 145.75, 158.97. Elemental Analysis for C32H32N2O5S2: Calculated: %C, 65.28; %H, 5.48; %N, 4.76, Found %C, 65.30; %H, 5.53; %N, 4.71.

5.1.27. (R)-3-(4-Benzoylphenyl)-2-(5-((4-butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-hydroxypropanamide (5b)

The title compound was prepared from the THP-protected hydroxamate 15b following the general procedure. The crude product was triturated with n-hexane to give a light yellow solid (75%yield). Mp 179-181 °C; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 0.89 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.20-1.39 (m, 2H); 1.48-1.63 (m, 2H); 2.60 (t, J=7.7 Hz, 2H); 2.80-2.97 (m, 2H); 3.86-3.98 (m, 1H); 7.19-7.33 (m, 8H); 7.47-7.70 (m, 7H); 8.70 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 1H); 9.00 (br s, 1H); 10.77 (s, 1H). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 13.75, 21.67, 32.74, 34.67, 55.47, 80.45, 95.67, 118.11, 127.44, 128.32, 128.59, 129.32, 129.40, 129.52, 131.20, 131.29, 135.02, 137.04, 142.05, 142.41, 144.14, 166.57, 195.02. Elemental Analysis for C32H30N2O5S2: Calculated%C, 65.51; %H, 5.15; %N, 4.77; Found %C, 65.57; %H, 5.19; %N, 4.70.

5.1.28. (R)-2-(5-((4-Butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-hydroxy-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanamide (5c)

The title compound was prepared from the THP-protected hydroxamate 15c following the general procedure. The crude product was triturated with Et2O and n-hexane to furnish a light gray solid (92%yield). Mp 90-91 °C; 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 0.93 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.26-1.40 (m, 2H); 1.54-1.69 (m, 2H); 2.67 (t, J=7.7 Hz, 2H); 2.99-3.09 (m, 1H); 3.20-3.29 (m, 1H); 4.05-4.16 (m, 1H); 6.96-7.38 (m, 8H); 7.48-7.52 (m, 2H); 10.04 (br s, 1H). 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 14.45, 23.25, 34.48, 36.43, 56.74, 112.54, 119.32, 119.84, 122.38, 125.09, 129.93, 135.57. Elemental Analysis for C27H27N3O4S2: Calculated: %C, 62.17; %H, 5.22; %N, 8.06; Found: %C, 62.21; %H, 5.24; %N, 8.00.

5.1.29. (R)-3-(Benzo[b]thiophen-3-yl)-2-(5-((4-butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophene-2-sulfonamido)-N-hydroxypropanamide (5d)

The title compound was prepared from the THP-protected hydroxamate 15d following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 2:1) to furnish a yellow oil (25%yield). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 0.93 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.28-1.41 (m, 2H); 1.58-1.66 (m, 2H); 2.67 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 2H); 3.16-3.27 (m, 1H); 3.34-3.44 (m, 1H); 4.16-4.27 (m, 1H); 6.91 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H); 7.28-7.32 (m, 2H); 7.35-7.43 (m, 4H); 7.48-7.52 (m, 2H); 7.74-7.79 (m, 1H); 7.88-7.92 (m, 1H); 8.46 (br s, 1H); 10.42 (br s, 1H). 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 13.96, 22.71, 33.93, 35.90, 55.29, 80.98, 96.40, 119.69, 122.09, 123.46, 124.59, 124.81, 125.70, 129.41, 131.27, 131.89, 132.02, 139.01, 140.92, 142.09, 145.22, 167.76. Elemental Analysis for C27H26N2O4S3: Calculated: %C, 60.20; %H, 4.86; %N, 5.20; Found: %C, 60.28; %H, 5.00; %N, 5.10.

5.1.30. (R)-3-(5-((4-Butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophen-2-ylsulfonyl)-N-hydroxythiazolidine-4-carboxamide (6)

The title compound was prepared from the THP-protected hydroxamate 22 following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 2:1) to furnish a yellow solid (25%yield). Mp 152-154 °C; 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 0.94 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.28-1.49 (m, 2H); 1.56-1.72 (m, 2H); 2.69 (t, J=7.7 Hz, 2H); 3.00 (dd, J1=7Hz, J2=10.5 Hz, 1H); 3.30 (dd, J1=4 Hz, J2=8.5 Hz, 1H); 4.65 (d, J1=10.5 Hz, 1H); 4.79 (d, J1=10.5 Hz, 1H); 4.69-4.76 (m, 1H); 7.29-7.32 (m, 2H); 7.44 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H); 7.75-7.77 (m, 2H); 7.76 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H); 8.22 (br s, 1H);10.57 (br s, 1H). 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 13.90, 14.43, 23.21, 34.43, 35.32, 36.40, 53.28, 64.95, 98.22, 119.84, 129.95, 131.83, 132.61, 133.61, 134.78, 137.78, 146.05, 160.62. Elemental Analysis for C20H22N2O4S3: Calculated: %C, 53.31; %H, 4.92; %N, 6.22; Found: %C, 53.40; %H, 4.96; %N, 6.18.

5.1.31. (R)-2-(5-((4-Butylphenyl)ethynyl)thiophen-2-ylsulfonyl)-N-hydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide (7)

The title compound was prepared from the THP-protected hydroxamate 23 following the general procedure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a Isolute Si (II) cartridge (n-hexane/EtOAc 2:1) to furnish a yellow semi-solid (32%yield). 1H-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 0.92 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 1.26-1.40 (m, 2H); 1.52-1.68 (m, 2H); 2.65 (t, J=7.7 Hz, 2H); 2.92 (dd, J1=4 Hz, J2=20 Hz, 1H); 3.16 (dd, J1=8 Hz, J2=20 Hz, 1H); 4.52-4.72 (m, 3H); 7.14-7.30 (m, 6H); 7.45-7.49 (m, 2H); 7.58 (d, J=4 Hz, 1H); 8.08 (br s, 1H); 10.42 (br s, 1H). 13C-NMR (Acetone-d6) δ: 13.83, 14.38, 23.14, 34.35, 36.32, 46.92, 55.72, 81.08, 97.41, 119.86, 127.33, 127.62, 128.27, 129.07, 129.84, 130.70, 132.48, 133.17, 133.41, 133.48, 133.68, 139.58, 145.83, 167.57. Elemental Analysis for C26H26N2O4S2: Calculated: %C, 63.13; %H, 5.30; %N, 5.66; Found: %C, 63.20; %H, 5.32; %N, 5.60.

5.2. MMP inhibition assays [38]

Recombinant human MMP-14 catalytic domain was a kind gift of Prof. Gillian Murphy (Department of Oncology, University of Cambridge, UK). Pro-MMP-1, pro-MMP-2, pro-MMP-3, pro-MMP-8, and pro-MMP-9 were purchased from Calbiochem.

Proenzymes were activated immediately prior to use with p-aminophenylmercuric acetate (APMA 2 mM for 1 h at 37 °C for MMP-2 and MMP-8, APMA 2 mM for 2 h at 37 °C for MMP-1, 1 mM for 1 h at 37 °C for MMP-9). Pro-MMP-3 was activated with trypsin 5 μg/mL for 30 min at 37 °C followed by soybean trypsin inhibitor 62 μg/mL. For assay measurements, the inhibitor stock solutions (10 mM in DMSO) were further diluted, at 7 different concentrations for each MMP in the fluorometric assay buffer (FAB: Tris 50 mM, pH =7.5, NaCl 150 mM, CaCl2 10 mM, Brij 35 0.05%and DMSO 1%). Activated enzyme (final concentration 0.5 nM for MMP-2, 1.3 nM for MMP-9, 1.5 nM for MMP-8, 5.0 nM for MMP-3, 1.0 nM for MMP-14cd, 2.0 nM for MMP-1) and inhibitor solutions were incubated in the assay buffer for 2 h at 25 °C. After the addition of the fluorogenic substrate Mca-Arg-Pro-Lys-Pro-Val-Glu-Nva-Trp-Arg-Lys(Dnp)-NH2 (Sigma) for MMP-3 and Mca-Lys-Pro-Leu-Gly-Leu-Dap(Dnp)-Ala-Arg-NH2 (Bachem) for all the other enzymes in DMSO (final concentration 2 μM), the hydrolysis was monitored every 15 s for 15 min, recording the increase in fluorescence (λex =325 nm, λem =395 nm) with a Molecular Devices SpectraMax Gemini XS plate reader. The assays were performed in duplicate in a total volume of 200 μL per well in 96-well microtiter plates (Corning black, NBS). The MMP inhibition activity was expressed in relative fluorescent units (RFU). Percent of inhibition was calculated from control reactions without the inhibitor. IC50 was determined using the formula: vi/vo =1/(1 +[I]/ IC50), where Vi is the initial velocity of substrate cleavage in the presence of the inhibitor at concentration [I]and Vo is the initial velocity in the absence of the inhibitor. Results were analyzed using SoftMax Pro software [39]and GraFit software [40].

5.3. Molecular Modeling. Docking simulations

Molecular docking of 5a into the X-ray structure of MMP-2 (PDB code: 1QIB) was carried out using the Glide 5.5 program [41]. Maestro 9.0.211 [42]was employed as the graphical user interface and Figure 4 was rendered by the Chimera software package [43].

5.3.1. Ligand and Protein Setup

The inhibitor structure was first generated through the Dundee PRODRG2 Server [44]. Then, CM1 atomic charges [45,46]were computed via single-point AM1 calculations using OPLS-AA [47]optimized geometries and the BOSS program [48,49]. The target protein was prepared through the Protein Preparation Wizard of the graphical user interface Maestro and the OPLS-2001 force field. Water molecules were removed, hydrogen atoms were added, a +2 charge was assigned to the zinc ion in the active site and minimization was performed until the RMSD of all heavy atoms was within 0.3 Å of the crystallographically determined positions. The binding pocket was identified by placing a 20 Å cube around the catalytic ion.

5.3.2. Docking Setting

Molecular docking calculations were performed with the aid of Glide 5.5 in extra-precision (XP) [50,51]mode, using Glidescore for ligand ranking. A constraint that forced the interaction with the metal ion was included. For multiple ligand docking experiments, an output maximum of 5000 ligand poses per docking run with a limit of 100 poses for each ligand was adopted.

5.4. Cells and Reagents

Cell culture media and growth supplements were obtained from Cambrex Bio Science Walkersville, Inc. (Walkersville, MD). Non-essential amino acids (1%) were from GIBCO (Milan, Italy). Trypan blue was from Sigma/RBI (Natick, MA). All other reagents were from standard commercial sources. The human GBM cell line U87MG was obtained from the National Institute for Cancer Research of Genoa. It was maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10%foetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 1% non-essential amino acids, at 37 °C in humidified atmosphere composed of 5%CO2 and 95%O2.

5.4.1. Cell treatment

U87MG cells were seeded at 30,000 cells/cm2 in serum-free medium and incubated in the absence (control) or presence of the MMPIs for 24 h. The MMPIs were tested at a single concentration (5 nM). Compound 5a was also assayed at concentrations of 1, 5, 25, 125 nM to ascertain its effect on cell invasion through Matrigel. The vehicle (DMSO) in which the compounds were dissolved never exceeded 1%of the final volume of culture medium.

5.4.2. Trypan Blue exclusion assay

Cell viability was ascertained in serum free medium containing 5 nM of the various compounds, using the Trypan Blue exclusion assay, as previously reported [36,52]. Briefly, after 24 h incubation, lightly trypsinized cells were collected by centrifugation at 800 x g for 5 min, stained with Trypan Blue dye (0.4%solution in 0.9%NaCl), and counted using a haemocytometer chamber (Burker counting chamber).

5.4.3. Invasion assay of U87MG glioblastoma cells through Matrigel

The effect of MMPIs on cell invasion through Matrigel was evaluated using a human glioblastoma cell line (U87MG) as follows: the surface of the transwell (24 Transwell 6.5 mm diameter 8.0 μm pore size polycarbonate filters, Costar, Corning, NY) was coated with 25 μL of Matrigel basement membrane matrix (BD Biosciences) (0.32 mg/mL) at room temperature overnight to form a genuine reconstituted basement membrane. The U87MG cells were suspended in serum free medium (60,000/400 μL), treated with 5 nM of each MMP inhibitor, and added to the upper compartment of the transwell, while 200 μL of RPMI containing 10%foetal bovine serum was added to the lower compartment. The cells were allowed to invade through the matrices at 37 °C for 24 h. The number of invading cells was quantified by counting the cells on the lower surface of the transwell membrane after fixing with p-formaldehyde and staining with crystal violet. Non-migrating cells on the upper surface were removed with a cotton bud. Pictures of randomly picked light microscope fields were taken (5 fields for each filter), and cells were counted using ImageJ Software[53]. Each compound concentration was tested in duplicate, and the experiments were repeated at least three times.

Statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA (with Bonferroni post-test) by using the GraphPad Prism computer program [54]. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data are presented as the mean ±S.E.M., derived from at least three independent experiments done in duplicate.

5.5. MMP-25 inhibition assay

The catalytic domain of MT6-MMP (MMP-25) was expressed in house, in E. coli followed by purification and refolding. Fluorescence was measured with a Photon Technology International (PTI) spectrofluorometer, equipped with the RadioMaster™ and FeliX™ hardware and software, respectively. The assays were carried out at 25 oC and the cuvette holder was thermostated at the same temperature. Excitation and emission band passes of 3 and 3 nm, respectively, were used. Fluorescence measurements were taken every 4 s. The enzymatic activity of MMP-25 was monitored with the fluorescence-quenched substrate MOCAcPLGLA2pr(Dnp)AR-NH2 at excitation and emission wavelengths of 328 and 393 nm, respectively. Fluorogenic substrate was obtained from Peptides International, Inc. (Louisville, KY). For competitive inhibition, initial rates were obtained by adding enzyme to a mixture of fluorogenic substrate and varying concentrations of inhibitor in buffer R (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.01%Brij-35, and 5% DMSO) final volume 1 mL, and monitoring the increase in fluorescence with time for 10 minutes. The initial velocities were determined by linear regression analysis of the fluorescence versus time traces using FeliX™. The initial rates were fitted to Eq. 1, where vi and v0 represent the initial velocity in the presence and absence of inhibitor, respectively, using the program SCIENTIST [55].

| (Eq. 1) |

Finally, MMP-25 inhibition data expressed as Ki have been converted in IC50 values, according to the equation:

Research highlights.

MMP-2, MMP-9 and MMP-25 have been recognized to be highly expressed in gliomas.

A series of sulfonamido-based hydroxamates was designed and synthesized.

Derivative 5a was found to have nanomolar activity toward MMP-2, MMP-9 and MMP25.

This compound also proved to have anti-invasive activity on U87MG glioma cell line.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Scientific Research (PRIN 2007) and by NIH/NCI grant CA100475 to Professor Rafael Fridman. The authors thank Dr. Marina Fabbi from National Institute for Cancer Research of Genoa for providing the human U87MG cell line.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Koutroulis I, Zarros A, Theocharis S. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in the pathophysiology and progression of human nervous system malignancies: a chance for the development of targeted therapeutic approaches? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:1577–1586. doi: 10.1517/14728220802560307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roomi MW, Monterrey JC, Kalinovsky T, Rath M, Niedzwiecki A. Patterns of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in human cancer cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:1323–1333. doi: 10.3892/or_00000358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao JS. Molecular mechanisms of glioma invasiveness: the role of proteases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kargiotis O, Chetty C, Gondi CS, Tsung AJ, Dinh DH, Gujrati M, Lakka SS, Kyritsis AP, Rao JS. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of siRNA against MMP-2 mRNA results in impaired invasion and tumor-induced angiogenesis, induces apoptosis in vitro and inhibits tumor growth in vivo in glioblastoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:4830–4840. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 5.Forsyth PA, Wong H, Laing TD, Rewcastle NB, Morris DG, Muzik H, Leco KJ, Johnston RN, Brasher PM, Sutherland G, Edwards DR. Gelatinase-A (MMP-2), gelatinase-B (MMP-9) and membrane type matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MT1-MMP) are involved in different aspects of the pathophysiology of malignant gliomas. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1828–1835. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6990291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Komatsu K, Nakanishi Y, Nemoto N, Hori T, Sawada T, Kobayashi M. Expression and quantitative analysis of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 in human gliomas. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2004;21:105–112. doi: 10.1007/BF02482184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coussens LM, Fingleton B, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and cancer: trials and tribulations. Science. 2002;295:2387–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1067100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Beckett RP, Davidson AH, Drummond AH, Huxley P, Whittaker M. Recent advances in matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor research. Drug Discov Today. 1996;1:16–26. [Google Scholar]; (b) Levin VA, Phuohanic S, Yung WKA, Forsyth PA, Del Maestro R, Perry RJ, Fuller GN, Baillet M. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of marimastat in glioblastoma multiforme patients following surgery and irradiation. J Neurooncol. 2006;78:295–302. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-9098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorbera LA, Castaner J. Prinomastat: oncolytic, matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor. Drugs Fut. 2000;25:150–158. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levitt NC, Eskens FA, O'Byrne KJ, Propper DJ, Denis LJ, Owen SJ, Choi L, Foekens JA, Wilner S, Wood JM, Nakajima M, Talbot DC, Steward WP, Harris AL, Verweij J. Phase I and pharmacological study of the oral matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, MMI270 (CGS27023A), in patients with advanced solid cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1912–1922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konstantinopoulos PA, Karamouzis MV, Papatsoris AG, Papavassiliou AG. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as anticancer agents. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1156–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overall CM, Kleifeld O. Tumour microenvironment - opinion: validating matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets and anti-targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:227–239. doi: 10.1038/nrc1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker DP, Barta TE, Bedell LJ, Boehm TL, Bond BR, Carroll J, Carron CP, Decrescenzo GA, Easton AM, Freskos JN, Funckes-Shippy CL, Heron M, Hockerman S, Howard CP, Kiefer JR, Li MH, Mathis KJ, McDonald JJ, Mehta PP, Munie GE, Sunyer T, Swearingen CA, Villamil CI, Welsch D, Williams JM, Yu Y, Yao J. Orally active MMP-1 sparing α-tetrahydropyranyl and α-piperidinyl sulfone matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitors with efficacy in cancer, arthritis, and cardiovascular disease. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6653–6680. doi: 10.1021/jm100669j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.López-Otín C, Palavalli LH, Samuels Y. Protective roles of matrix metalloproteinases: from mouse models to human cancer. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3657–3662. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.22.9956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Puerta DT, Mongan J, Tran BL, McCammon JA, Cohen SM. Potent, selective pyrone-based inhibitors of stromelysin-1. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14148–14149. doi: 10.1021/ja054558o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Puerta DT, Griffin MO, Lewis JA, Romero-Perez D, Garcia R, Villarreal FJ, Cohen SM. Heterocyclic zinc-binding groups for use in next-generation matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors: potency, toxicity, and reactivity. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Regarding the debate on the use of hydroxamates as ZBG for metalloenzymes see: Nuti E, Panelli L, Casalini F, Avramova SI, Orlandini E, Santamaria S, Nencetti S, Tuccinardi T, Martinelli A, Cercignani G, D'Amelio N, Maiocchi A, Uggeri F, Rossello A. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and NMR studies of a new series of arylsulfones as selective and potent Matrix Metalloproteinase-12 inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2009;52:6347–6361. doi: 10.1021/jm900335a.Flipo M, Charton J, Hocine A, Dassonneville S, Deprez B, Deprez-Poulain R. Hydroxamates: Relationships between Structure and Plasma Stability. J Med Chem. 2009;52:6790–6802. doi: 10.1021/jm900648x.

- 17.(a) Tamura Y, Watanabe F, Nakatani T, Yasui K, Fuji M, Komurasaki T, Tsuzuki H, Maekawa R, Yoshioka T, Kawada K, Sugita K, Ohtani M. Highly selective and orally active inhibitors of type IV collagenase (MMP-9 and MMP-2): N-sulfonylamino acid derivatives. J Med Chem. 1998;41:640–649. doi: 10.1021/jm9707582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kiyama R, Tamura Y, Watanabe F, Tsuzuki H, Ohtani M, Yodo M. Homology modeling of gelatinase catalytic domains and docking simulations of novel sulfonamide inhibitors. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1723–1738. doi: 10.1021/jm980514x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Terp GE, Cruciani G, Christensen IT, Jorgensen FS. Structural differences of matrix metalloproteinases with potential implications for inhibitor selectivity examined by the GRID/CPCA approach. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2675–2684. doi: 10.1021/jm0109053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Aureli L, Gioia M, Cerbara I, Monaco S, Fasciglione GF, Marini S, Ascenzi P, Topai A, Coletta M. Structural bases for substrate and inhibitor recognition by matrix metalloproteinases. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:2192–2222. doi: 10.2174/092986708785747490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agrawal A, Romero-Perez D, Jacobsen JA, Villarreal FJ, Cohen SM. Zinc-binding groups modulate selective inhibition of MMPs. Chem Med Chem. 2008;3:812–820. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossello A, Nuti E, Carelli P, Orlandini E, Macchia M, Nencetti S, Zandomeneghi M, Balzano F, Uccello Barretta G, Albini A, Benelli R, Cercignani G, Murphy G, Balsamo A. N-i-Propoxy-N-biphenylsulfonylaminobutylhydroxamic acids as potent and selective inhibitors of MMP-2 and MT1-MMP. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:1321–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanessian S, MacKay DB, Moitessier N. Design and synthesis of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors guided by molecular modeling. Picking the S(1) pocket using conformationally constrained inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2001;44:3074–3082. doi: 10.1021/jm010096n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neustadt BR. Facile Preparation of N-(Sulfonyl)carbamates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:379–380. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonogashira K, Tohda Y, Hagihara N. Convenient Synthesis of Acetylenes: Catalytic Substitutions of Acetylenic Hydrogen with Bromoalkenes, Iodoarenes, and Bromopyridines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;50:4467–4470. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirakawa E, Sato T, Imazaki Y, Kimura T, Hayashi T. Cobalt-catalyzed cross-coupling of alkynyl Grignard reagents with alkenyl triflates. Chem Commun. 2007;43:4513–4515. doi: 10.1039/b711884h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nuti E, Orlandini E, Nencetti S, Rossello A, Innocenti A, Scozzafava A, Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrase and matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Inhibition of human tumor-associated isozymes IX and cytosolic isozyme I and II with sulfonylated hydroxamates. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:2298–2311. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker DP, Villamil CI, Barta TE, Bedell LJ, Boehm TL, Decrescenzo GA, Freskos JN, Getman DP, Hockerman S, Heintz R, Howard SC, Li MH, McDonald JJ, Carron CP, Funckes-Shippy CL, Mehta PP, Munie GE, Swearingen CA. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of beta- and alpha-piperidine sulfone hydroxamic acid matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors with oral antitumor efficacy. J Med Chem. 2005;48:6713–6730. doi: 10.1021/jm0500875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng SL, Reid S, Lin N, Wang B. Microwave-assisted synthesis of ethynylarylboronates for the construction of boronic acid-based fluorescent sensors for carbohydrates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:2331–2335. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shook BC, Chakravarty D, Jackson PF. Microwave-assisted Sonogashira-type cross couplings of various heterocyclic methylthioethers. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1013–1015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neumann U, Kubota H, Frei K, Ganu V, Leppert D. Characterization of Mca-Lys-Pro-Leu-Gly-Leu-Dpa-Ala-Arg-NH2, a fluorogenic substrate with increased specificity constants for collagenases and tumor necrosis factor converting enzyme. Anal Biochem. 2004;328:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhanaraj V, Williams MG, Ye QZ, Molina F, Johnson LL, Ortwine DF, Pavlovsky A, Rubin JR, Skeean RW, White AD, Humblet C, Hupe DJ, Blundell TL. X-ray structure of gelatinase A catalytic domain complexed with a hydroxamate inhibitor. Croat Chem Acta. 1999;72:575–591. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pei D. Leukolysin/MMP25/MT6-MMP: a novel matrix metalloproteinase specifically expressed in the leukocyte lineage. Cell Res. 1999;9:291–303. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun Q, Weber CR, Sohail A, Bernardo MM, Toth M, Zhao H, Turner JR, Fridman R. MMP25 (MT6-MMP) is highly expressed in human colon cancer, promotes tumor growth, and exhibits unique biochemical properties. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21998–22010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701737200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Velasco G, Cal S, Merlos-Suárez A, Ferrando AA, Alvarez S, Nakano A, Arribas J, López-Otín C. Human MT6-matrix metalloproteinase: identification, progelatinase A activation, and expression in brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:877–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nuttall RK, Pennington CJ, Taplin J, Wheal A, Yong VW, Forsyth PA, Edwards DR. Elevated membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases in gliomas revealed by profiling proteases and inhibitors in human cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:333–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sohail A, Sun Q, Zhao H, Bernardo MM, Cho JA, Fridman R. A unique set of membrane-anchored matrix metalloproteinases: properties and expression in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:289–302. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Krüger A, Arlt MJ, Gerg M, Kopitz C, Bernardo MM, Chang M, Mobashery S, Fridman R. Antimetastatic activity of a novel mechanism-based gelatinase inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3523–3526. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bonfil RD, Sabbota A, Nabha S, Bernardo MM, Dong Z, Meng H, Yamamoto H, Chinni SR, Lim IT, Chang M, Filetti LC, Mobashery S, Cher ML, Fridman R. Inhibition of human prostate cancer growth, osteolysis and angiogenesis in a bone metastasis model by a novel mechanism-based selective gelatinase inhibitor. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2721–2726. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hoffman A, Qadri B, Frant J, Katz Y, Bhusare SR, Breuer E, Hadar R, Reich R. Carbamoylphosphonate matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors 6: cis-2-aminocyclohexylcarbamoylphosphonic acid, a novel orally active antimetastatic matrix metalloproteinase-2 selective inhibitor - synthesis and pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic analysis. J Med Chem. 2008;51:1406–1414. doi: 10.1021/jm701087n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lee M, Celenza G, Boggess B, Blase J, Shi Q, Toth M, Bernardo MM, Wolter WR, Suckow MA, Hesek D, Noll BC, Fridman R, Mobashery S, Chang M. A potent gelatinase inhibitor with anti-tumor-invasive activity and its metabolic disposition. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;73:189–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabelloni P, Da Pozzo E, Bendinelli S, Costa B, Nuti E, Casalini F, Orlandini E, Da Settimo F, Rossello A, Martini C. Inhibition of metalloproteinases derived from tumours: new insights in the treatment of human glioblastoma. Neuroscience. 2010;168:514–522. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacPherson LJ, Bayburt EK, Capparelli MP, Carroll BJ, Goldstein R, Justice MR, Zhu L, Hu S, Melton RA, Fryer L, Goldberg RL, Doughty JR, Spirito S, Blancuzzi V, Wilson D, O'Byrne EM, Ganu V, Parker DT. Discovery of CGS 27023A, a non-peptidic, potent, and orally active stromelysin inhibitor that blocks cartilage degradation in rabbits. J Med Chem. 1997;40:2525–2532. doi: 10.1021/jm960871c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knight CG, Willenbrock F, Murphy G. A novel coumarin-labelled peptide for sensitive continuous assays of the matrix metalloproteinases. FEBS Lett. 1992;296:263–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.SoftMax Pro 4.7.1 by Molecular Devices.

- 40.GraFit version 4 by Erithecus Software.

- 41.Glide, version 5.5. Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maestro, version 9.0.211. Schrödinger, L.L.C.; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera - A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuttelkopf AW, van Aalten DM. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:1355–1363. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904011679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Storer JW, Giesen DJ, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. Class IV charge models: a new semiempirical approach in quantum chemistry. J Comput-Aided Mol Des. 1995;9:87–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00117280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson JD, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. Parameterization of charge model 3 for AM1, PM3, BLYP, and B3LYP. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:1291–1304. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jorgensen WL, Maxwell DS, Tirado–Rives J. Development and Testing of the OPLS All-Atom Force Field on Conformational Energetics and Properties of Organic Liquids. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:11225–11236. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jorgensen WL. BOSS Version 4.6. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Udier-Blagović M, Morales De Tirado P, Pearlman SA, Jorgensen WL. Accuracy of free energies of hydration using CM1 and CM3 atomic charges. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1322–1332. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shelley M, Perry JK, Shaw DE, Francis P, Shenkin PS. Glide: A new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Repasky MP, Frye LL, Greenwood JR, Halgren TA, Sanschagrin PC, Mainz DT. Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6177–6196. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruan S, Okcu MF, Pong RC, Andreeff M, Levin V, Hsieh JT, Zhang W. Attenuation of WAF1/Cip1 expression by an antisense adenovirus expression vector sensitizes glioblastoma cells to apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea and cisplatin. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.ImageJ Software, version 1.41o. USA: [Google Scholar]

- 54.GraphPad Software, version 4.0. San Diego, CA: [Google Scholar]

- 55.MicroMath Scientific Software. Salt Lake City, UT: [Google Scholar]