Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the study was to describe the mode, frequency, duration, and intensity of physical activity among pregnant women, to explore whether these women reached the recommended levels of activity, and to explore how these patterns changed during pregnancy.

Methods

This study, as part of the third phase of the Pregnancy, Infection, and Nutrition Study, investigated physical activity among 1482 pregnant women. A recall of the different modes, frequency, duration, and intensity of physical activity during the past week was assessed in two telephone interviews at 17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation.

Results

Most women reported some type of physical activity during both time periods. Child and adult care giving, indoor household, and recreational activities constituted the largest proportion of total reported activity. The overall physical activity level decreased during pregnancy, particularly in care giving, outdoor household, and recreational activity. Women who were active during the second and third trimesters reported higher levels of activity in all modes of activity than those who became active or inactive during pregnancy. The majority did not reach the recommended level of physical activity.

Conclusion

These data suggest that self-reported physical activity decreased from the second to third trimester and only a small proportion reached the recommended level of activity during pregnancy. Further research is needed to explore if physical activity rebounds during the postpartum period.

Keywords: exercise, guidelines, leisure activities, reproduction

Introduction

Regular physical activity is recommended for pregnant and postpartum women for maternal, fetal, and neonatal wellbeing (1, 4, 10, 30). Health benefits of physical activity during and immediately after pregnancy include possible prevention of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and chronic musculoskeletal conditions, support of healthy weight, and improved mental health (1, 4, 10, 19, 30). Moreover, regular exercise helps maintain cardiorespiratory fitness levels throughout pregnancy and can facilitate postpartum recovery (4, 10, 19). Thus, for the many short and long term health benefits of physical activity, it is important to study physical activity behavior among pregnant women. Pregnancy is a life changing event that can initiate an adverse change in physical activity.

Previous retrospective and prospective studies indicate that physical activity among pregnant women declines for recreational (9, 15, 20–22, 25, 34, 35), occupational (9, 20), and overall (9, 29) physical activity. The largest changes occur in the duration and intensity of physical activity in the third trimester, as compared to the activity levels at pre-pregnancy or during the first trimester (9, 14, 21, 22, 25, 28, 33, 35). It seems that women replace strenuous activities with lighter intensity activities as their pregnancy progresses, which leads to increased duration of light activity (9, 28, 37) or decreased total volume of activity (21, 28). The scientific literature has concentrated on reporting exercise or recreational physical activity during pregnancy, while occupational, household, or transportation activity is often not included in the same study, with only a few exceptions (7, 9, 20, 33).

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that pregnant women engage in moderate-intensity exercise for at least 30 minutes on most, if not all, days of the week (1). We found only three studies (12, 25, 26) that documented the percentage of pregnant women reaching physical activity recommendations, though none them used the ACOG definition of activity and all three studies measured only recreational physical activity, ignoring other types of activity that may contribute to health. Only Pereira et al. (25) provided information on the change in percentage of recreational activity during pregnancy and on which gestational week the activity level was measured.

Most previous studies describing physical activity during pregnancy have various limitations including retrospective or cross-sectional design, small sample size, or inadequate measurement of activity (6, 8, 16, 28). Measurement of physical activity should assess frequency, duration, and intensity in overall activity and in different modes, such as in occupation and transportation (23). To address these limitations, we investigated physical activity among pregnant women, documented whether these women reached the recommended levels of activity, and explored how these patterns changed during pregnancy.

Methods

This study was part of the third phase of the Pregnancy, Infection, and Nutrition Study (PIN3), a prospective study that examined whether physical activity or stress was associated with preterm birth. The participants were pregnant women seeking services from prenatal clinics at the University of North Carolina Hospitals (Chapel Hill, NC) and were identified by study staff through a review of all medical charts of new prenatal patients. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol, and the participants gave their written informed consent. Study staff recruited the women at their second prenatal visit if they were less than or equal to 20 weeks’ gestation. Exclusions for the recruitment included women under the age of 16 years, non-English speakers, those not planning to continue care or deliver at the study site, women carrying multiple gestations, or women who did not have a telephone from which they could complete phone interviews. Recruitment began in January 2001 and ended in December 2005. During this time 3,203 women were eligible for the study, and 2,006 (63%) were recruited. For analyses in this study, we excluded women if they participated in the PIN3 Study for a second or third time (n=131), were under the age of 18 (n=33), or had missing information on physical activity from the two interviews (n=360), leaving 1482 (73.9%) women in the analysis sample.

Women participated in two research center visits and telephone interviews, along with filling out several self-administered questionnaires. The telephone interviews were carried out at 17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation, falling into the second and third trimesters of their pregnancy.

Physical Activity Measurement

Interviewers administered a past week recall questionnaire on physical activity during the two telephone interviews. The questionnaire assessed frequency and duration of all physical activities separately for recreational, occupational, transportation, child and adult care, and indoor and outdoor household activity. Using recreational activity as an example, the question asking about participation in particular modes of physical activity was: “In the past week, did you participate in any non-work, recreational activity or exercise, such as walking for exercise, swimming, or dancing, that caused at least some increase in breathing and heart rate?” If the participant responded ‘Yes’, then the interviewer asked her to list all types of activities, one by one, with the following question: “What type of recreational activities did you do during the past week?” For each activity, the participant reported the number of sessions per week, duration of each session, and the perceived intensity level using the following options: ‘fairly light,’ ‘somewhat hard,’ and ‘hard or very hard’. The perceived intensity categories were developed from the Borg scale (5). In addition, the activities were later assigned an absolute intensity level using published metabolic equivalent (MET) tables (2, 3). These questions were repeated for occupational, transportation, child and adult care giving, indoor household, and outdoor household activity. The outcome variables were estimates of total number of hours in the past week (h/wk) and total number of MET hours in the past week (MET h/wk), in which MET h/wk was based on established MET intensities (2, 3).

Women were assigned an activity status based on whether they reported any physical activity at the17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation. Those who were active at both trimesters were defined as ‘active’ and those not active at both trimesters were ‘inactive’. Those women who stopped physical activity between the two time points were categorized as ‘became inactive’. If the participant was inactive in the second trimester and active at the third trimester, she was categorized as ‘became active’.

The women were categorized by whether they reached the recommendations for physical activity, based on the guidelines by the ACOG (1), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (24, 36), and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) (24, 27), The ACOG and CDC/ACSM guidelines suggest 30 minutes or more of moderate intensity activity on most days of the week, but they differ on the type of activity, as ACOG recommends only exercise and CDC/ACSM recommends any type of physical activity. The ACSM’s vigorous recommendation includes any type of activity that is vigorous and is carried out at least 20 minutes, three times per week. We created four recommended activity levels: 1) ACOG’s recommendation using an absolute intensity of 4.8–7.1 METs (moderate intensity based on age 20–39 years) (27), 2) ACOG’s recommendation using ‘somewhat hard’ perceived intensity to match with a moderate intensity, 3) combined CDC/ACSM’s moderate and ACSM’s vigorous recommendation using absolute intensity of ≥4.8 METs, and 4) combined CDC/ACSM’s moderate and ACSM’s vigorous recommendation using ‘somewhat hard’ and ‘hard or very hard’ perceived intensity.

The physical activity questionnaire took approximately 10 to 20 minutes to complete. Intra- and inter-interviewer quality control measures, such as expert review of taped interviews, were established to ensure that interviewers were asking questions reliably and systematically. The test-retest reliability of this questionnaire was measured among 109 women within 48 hours of interview completion at 17–22 or 27–30 weeks’ gestation. The measures used for this study generally displayed substantial agreement using Landis and Kohl’s classification (18). For example, the intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.83 (95% confidence intervals, CI, 0.76–0.88) for total activity in MET h/wk. The criterion validity of this questionnaire was examined in 177 pregnant women who wore an accelerometer for one week, kept a daily structured diary, and following these two measures, completed a one-week recall of the PIN3 physical activity questionnaire. The diary generally displayed moderate to substantial agreement with the questionnaire; the Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.67 (95% CI 0.55–0.78) for total activity in MET h/wk. The agreement between the questionnaire and accelerometer was lower, with the Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.29 (95% CI 0.10–0.47) for total activity in MET h/wk comparing total counts. A detailed description of how the physical activity questionnaire was coded and how the recommended levels of activity were derived is available elsewhere (11).

Other measurements

Women were asked during the telephone interview about their race and ethnicity, marital status, working status, education, parity (live plus still births), and general health. Pre-pregnancy self-reported weight and height were collected at the recruitment interview at 15–20 weeks’ gestation for the determination of body mass index as weight in kilograms divided by height in squared meters.

Statistical methods

The percentages and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) of physical activity at the two interviews were reported separately for fairly light, somewhat hard, and hard or very hard perceived intensity levels in h/wk and for absolute intensity levels in MET h/wk in each mode of activity. Poisson regression models with generalized estimating equations (GEE) for repeated count measures, using an exchangeable working correlation, were applied to test whether the change in physical activity (total or by perceived and absolute intensity levels) across the two time points was different (38). The goodness-of-fit statistics of all models indicated overdispersion, therefore the Pearson scaling adjustment was applied.

The number of reported activities, the MET values of activities, and the duration of activities at 17–22 and 27–30 weeks of gestation were reported separately for modes and perceived intensities of physical activity using medians with IQR and tested for differences in time with the non-parametric sign test. Participation in the modes of physical activity was reported across the trimesters using medians with IQR separately for ‘active,’ ‘became active,’ and ‘became inactive’ women. We used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to explore the differences in the three groups (‘active,’ ‘became active,’ and ‘became inactive’). The signed rank test was used to explore the difference in activity between the 17–22 and 27–30 weeks of gestation among the ‘active’ women. The percentage of women who reached the ACOG and CDC/ACSM recommended level of activity was reported across the second and third trimester. The difference in the percentage was tested using the GEE model as previously described. The SAS statistical package (version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all of the analyses.

Results

Description of sample

Among the sample of 1482 pregnant women, the median age at conception was 30 years and most (60.2%) belonged to the age group of 26–34 years. The majority, 71.6%, were non-Hispanic white women, while 17.3% were non-Hispanic African American, and 11.1% of other race/ethnic background. The women reported a median of 16 years of education and 63% had at least 16 years of education. Most women had no children (49.4%) or one child (32.9%) and had an excellent (32.0%) or very good (43.3%) self-perceived health status. The median pre-pregnancy body mass index was 23.4 kg/m2.

Modes and components of self-reported physical activity

The majority of women reported some physical activity during the second (96.5%) and third (93.9%) trimesters (Table 1). When examining all modes together, the level of physical activity decreased between the second and third trimester in fairly light (p<0.001) and hard or very hard (p=0.02) intensity categories, but also in total activity (p<0.001 for both h/wk and MET h/wk). In the separate modes, decreasing activity levels were observed for fairly light (p=0.01) and total (p<0.001 for both h/wk and MET h/wk) care-related activity, for fairly light (p=0.003) and total (p=0.05 for h/wk and p=0.03 for MET h/wk) household-related outdoor activity, and for somewhat hard (p=0.03), hard or very hard (p=0.01), and total (p=0.01 for h/wk and p<0.001 for MET h/wk) recreational activity. Among the full sample, the number of women who reported any occupational physical activity at their second trimester (32%) and third trimester (30%) remained stable, but they reported very low levels of occupational physical activity, with medians of 0.0 h/wk and 0.0 MET h/wk for all intensity levels at the second and third trimester.

Table 1.

The modes and self-reported intensities of physical activity at 17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation among all women (n=1482). The reported values are percentages reporting any activity and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) in hours per week (h/wk) and MET hours per week (MET h/wk).

| 17–22 weeks of gestation | 27–30 weeks of gestation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Activity %* | Median (IQR) | Any Activity %* | Median (IQR) | p-value† | |

| All modes of activity | |||||

| Fairly light (h/wk) | 86.4 | 2.2 (0.7–5.3) | 81.8 | 2.0 (0.4–4.5) | <0.001 |

| Somewhat hard (h/wk) | 63.8 | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 61.9 | 0.9 (0.0–2.8) | 0.23 |

| Hard or very hard (h/wk) | 16.5 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 14.7 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.02 |

| Total (h/wk) | 96.5 | 4.7 (2.2–9.3) | 93.9 | 4.2 (1.9–8.4) | <0.001 |

| Total (MET h/wk) | 96.5 | 17.5 (8.3–34.5) | 93.9 | 15.0 (6.4–30.1) | <0.001 |

| Care-related activity | |||||

| Fairly light (h/wk) | 28.3 | 0.0 (0.0. –0.3) | 24.7 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.01 |

| Somewhat hard (h/wk) | 15.7 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 15.1 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.13 |

| Hard or very hard (h/wk) | 3.58 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 3.4 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.20 |

| Total (h/wk) | 38.8 | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | 36.1 | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | <0.001 |

| Total (MET h/wk) | 38.8 | 0.0 (0.0–5.1) | 36.1 | 0.0 (0.0–3.5) | <0.001 |

| Household-related indoor activity | |||||

| Fairly light (h/wk) | 57.0 | 0.3 (0.0–1.3) | 57.4 | 0.3 (0.0–1.2) | 0.11 |

| Somewhat hard (h/wk) | 21.0 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 24.1 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.17 |

| Hard or very hard (h/wk) | 4.0 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 4.1 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.07 |

| Total (h/wk) | 65.5 | 0.5 (0.0–2.0) | 67.5 | 0.6 (0.0–2.0) | 0.42 |

| Total (MET h/wk) | 65.5 | 1.8 (0.0–5.6) | 67.5 | 1.8 (0.0–5.3) | 0.31 |

| Household-related outdoor activity | |||||

| Fairly light (h/wk) | 13.5 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 10.2 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.003 |

| Somewhat hard (h/wk) | 5.1 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 6.3 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.77 |

| Hard or very hard (h/wk) | 1.3 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 1.1 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.53 |

| Total (h/wk) | 18.1 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 15.9 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.05 |

| Total (MET h/wk) | 18.1 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 15.9 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.03 |

| Recreational activity | |||||

| Fairly light (h/wk) | 37.9 | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 33.9 | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.83 |

| Somewhat hard (h/wk) | 37.8 | 0.0 (0.0–1.3) | 33.1 | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.03 |

| Hard or very hard (h/wk) | 8.6 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 6.8 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.01 |

| Total (h/wk) | 67.8 | 1.0 (0.0–2.8) | 60.7 | 1.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.01 |

| Total (MET h/wk) | 67.8 | 4.5 (0.0–11.2) | 60.7 | 3.7 (0.0–9.6) | <0.001 |

| Transportation activity | |||||

| Fairly light (h/wk) | 12.4 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 10.6 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.45 |

| Somewhat hard (h/wk) | 7.2 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 7.0 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.67 |

| Hard or very hard (h/wk) | 1.6 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 2.0 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.69 |

| Total (h/wk) | 21.1 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 19.4 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.67 |

| Total (MET h/wk) | 21.1 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 19.4 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.67 |

| Occupational activity | |||||

| Fairly light (h/wk) | 24.6 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 20.5 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.19 |

| Somewhat hard (h/wk) | 10.9 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 11.7 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.75 |

| Hard or very hard (h/wk) | 1.2 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 1.3 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.35 |

| Total (h/wk) | 31.9 | 0.0 (0.0–0.3) | 30.2 | 0.0 (0.0–0.3) | 0.16 |

| Total (MET h/wk) | 31.9 | 0.0 (0.0–1.4) | 30.2 | 0.0 (0.0–1.1) | 0.05 |

Percentage of participants that reported any physical activity in each mode and perceived intensity category.

P-value for the mean difference between 17–22 weeks and 27–30 weeks of gestation (GEE model).

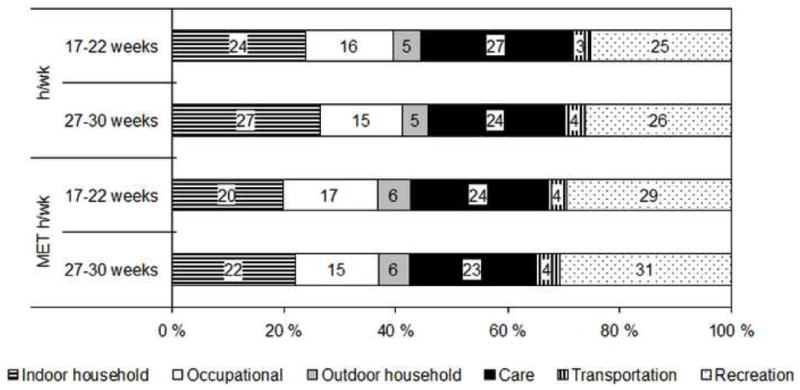

Care-related, household-related indoor, and recreational activities represented the largest part of women’s activities, as each mode constituted around 25% of total physical activity in h/wk (Figure 1). When examining the total MET h/wk, where intensity is accounted for, recreational physical activity was the largest contributor, with around 30% of the total MET h/wk. The distribution of percentages in each mode of activity remained fairly stable between the two interviews (Figure 1), while the total time declined between the two interviews (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution (%) of modes of physical activity in hours per week (h/wk) and in MET hours per week (MET h/wk) at 17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation.

The women reported on average five different types of activities in the past week in the second trimester and four activities in the third trimester (Table 2). The median MET values of the reported activities did not meaningfully change from the second trimester (4.5 METs) to the third trimester (4.6 METs). The median duration of reported activities significantly declined from 1.1 hours per activity at the second trimester to 1.0 hours per activity at the third trimester. Women commonly remained active in occupational activity (80%), household-related indoor activity (50%), and recreational activity (48%) between 17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation (Table 3). There were only 14 (1%) women who reported being entirely physically inactive at both time points. The consistently active women reported higher levels of physical activity for all modes of activity than those switching their activity status during the time points, except for occupational and household-related outdoor activity.

Table 2.

Reported number of activities, MET values of reported activities, and duration of activities overall and by mode among pregnant women (n=1482). The values are medians (with interquartile range, IQR).

| Number of reported activities | MET values of activities | Duration (hours per activity) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17–22 weeks | 27–30 weeks | P value* | 17–22 weeks | 27–30 weeks | P value* | 17–22 weeks | 27–30 weeks | P value* | |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||||

| All modes of activity | 5 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | <0.001 | 4.5 (4.0–5.3) | 4.6 (3.9–5.3) | 0.71 | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | 1.0 (0.5–1.6) | 0.003 |

| By modes | |||||||||

| Care | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | <0.001 | 3.2 (3.0–3.5) | 3.2 (3.0–3.4) | 0.77 | 1.8 (0.7–3.6) | 1.4 (0.6–3.0) | 0.006 |

| Indoor household | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | <0.001 | 3.1 (2.5–3.5) | 3.1 (2.5–3.5) | 0.64 | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 0.95 |

| Outdoor household | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 0.82 | 4.3 (4.0–4.5) | 4.3 (4.0–4.5) | 0.89 | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 1.0 (0.5–1.8) | 0.001 |

| Recreational | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | <0.001 | 3.7 (3.7–5.1) | 3.7 (3.7–4.9) | 0.046 | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | 0.76 |

| Transportation | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 1.0 | 4.0 (4.0–4.0) | 4.0 (4.0–4.0) | 0.8 (0.5–1.7) | 1.0 (0.5–1.7) | 0.90 | |

| Occupational | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | <0.001 | 3.7 (3.3–4.0) | 3.5 (3.3–4.0) | 0.91 | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) | 0.8 (0.3–2.0) | 0.11 |

P-value for the difference between time points from the sign test. For transportation, the MET value was the same across time so the p-value is not provided.

Table 3.

Participation in any physical activity stratified by whether women remained active, became active, or became inactive at 17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation. The reported values are medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) in hours per week (h/wk) and MET hours per week (MET h/wk).

| 17–22 weeks | 27–30 weeks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h/wk | MET h/wk | h/wk | MET h/wk | ||

| %* | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| All modes of activity | |||||

| Active | 91.4 | 5.2 (2.6–9.8) | 18.6 (9.9–36.6) | 4.5 (2.2–9.1)† | 16.6 (7.8–31.7)† |

| Became active | 2.6 | 2.2 (0.5–5.0)‡ | 7.7 (1.9–16.9)‡ | ||

| Became inactive | 5.1 | 2.5 (1.0–5.7)‡ | 10.6 (3.5–19.7)‡ | ||

| Care–related activity | |||||

| Active | 27.5 | 3.5 (1.3–8.1) | 11.1 (4.2–26.4) | 2.4 (1.0–5.8)† | 8.0 (3.3–19.0)† |

| Became active | 8.6 | 1.2 (0.5–3.0)‡ | 4.5 (1.6–10.1)‡ | ||

| Became inactive | 11.3 | 1.5 (0.5–4.0)‡ | 5.4 (2.0–13.0)‡ | ||

| Household-related indoor activity | |||||

| Active | 50.4 | 1.6 (0.6–3.5) | 4.4 (1.8–10.0) | 1.3 (0.7–3.0)† | 3.8 (1.8–8.5)† |

| Became active | 17.1 | 1.0 (0.5–2.3)‡ | 3.0 (1.3–6.9)‡ | ||

| Became inactive | 15.1 | 1.0 (0.5–2.0)‡ | 3.0 (1.3–6.6)‡ | ||

| Household-related outdoor activity | |||||

| Active | 5.9 | 1.5 (1.0–3.0) | 6.7 (4.0–12.0) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0)† | 4.5 (2.2–9.0)† |

| Became active | 10.1 | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 4.5 (2.2–9.0) | ||

| Became inactive | 12.2 | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 4.3 (2.2–8.8)‡ | ||

| Recreational activity | |||||

| Active | 48.2 | 2.3 (1.3–3.8) | 9.7 (5.6–16.9) | 2.0 (1.2–3.8) | 8.6 (4.5–16.6)† |

| Became active | 12.5 | 1.3 (0.8–2.3)‡ | 5.5 (3.1–8.6)‡ | ||

| Became inactive | 19.6 | 1.5 (1.0–2.5)‡ | 5.6 (3.6–11.1)‡ | ||

| Transportation activity | |||||

| Active | 10.8 | 1.0 (0.7–1.7) | 4.0 (2.7–6.7) | 1.2 (0.7–1.7) | 4.7 (2.7–6.7) |

| Became active | 8.7 | 0.7 (0.3–1.3)‡ | 2.7 (1.3–5.3)‡ | ||

| Became inactive | 10.4 | 0.7 (0.4–1.3)‡ | 2.7 (1.6–5.4)‡ | ||

| Occupational activity§ | |||||

| Active | 79.9 | 0.0 (0.0–0.8) | 0.0 (0.0–3.3) | 0.0 (0.0–0.8) | 0.0 (0.0–3.0) |

| Became active | 2.2 | 0.2 (0.0–1.7) | 0.9 (0.0–5.5) | ||

| Became inactive | 17.9 | 0.0 (0.0–1.7) | 0.0 (0.0–6.0) | ||

Percent of women who were physically active at 17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation (active), became physically active at 27–30 weeks’ gestation (became active), and became physically inactive at 27–30 weeks’ gestation (became inactive). The percent was calculated separately for each mode of activity. Those women who reported no physical activity at both time points are not included in the table.

The difference between 17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation was statistically significant at alpha level p<0.05 (the signed rank test).

The difference between ‘active’ versus ‘became active’ and ‘active’ versus ‘became inactive’ was statistically significant at alpha level p<0.05 (the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test).

Those women who reported to be working in either of the trimesters (n=1206).

Recommended physical activity

The proportion of women reaching the recommended level of physical activity using the ACOG definition at the second trimester was 3% for absolute intensity and 13% for perceived intensity (Table 4). When using the CDC/ACSM moderate/vigorous activity definition the proportion was 15% for absolute intensity and 38% for perceived intensity. The corresponding proportions mostly decreased at the third trimester, to 3% (p=0.9) and 11% (p=0.05) for the ACOG and 11% (p<0.001) and 34% (p=0.005) for the CDC/ACSM moderate/vigorous definition.

Table 4.

The definitions and percent of the recommended level of physical activity at 17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), and the American Heart Association (AHA) and ACSM.

| Definition | % Reaching Recommendation | P- value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of activity | Frequency and duration | Intensity | 17–22 weeks | 27–30 weeks | ||

|

|

||||||

| ACOG | Exercise† | ≥5 times/wk, ≥150 minutes/wk | Moderate | |||

| Absolute intensity (4.8–7.1 METs)‡ | 3.0 | 3.1 | 0.90 | |||

| Perceived intensity (somewhat hard)§ | 12.9 | 10.8 | 0.05 | |||

| CDC/ACSM combined | Any | ≥5 times/wk, ≥150 minutes/wk (moderate intensity) or ≥3 times/wk, ≥60 minutes/wk (vigorous intensity) | Moderate or vigorous | |||

| Absolute intensity (moderate 4.8–7.1 METs; vigorous >7.1 METs)‡ | 15.2 | 11.4 | <0.001 | |||

| Perceived intensity (somewhat hard or hard/very hard)§ | 38.0 | 33.7 | 0.005 | |||

P-value for the difference in prevalence between 17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation (GEE model).

Exercise was defined as any ‘planned, structured, and repetitive movement done to improve or maintain one or more components of physical fitness’ (36) and included recreational activities such as: bicycling, aerobics, walking, pushing a stroller, water activities, and sports, but not occupational or transportation activities,

Absolute intensity level was based on the metabolic cost (2,3), where age-specific MET values were used (27).

Perceived intensity was based on self-report of activity being fairly light, somewhat hard, or hard or very hard.

Discussion

Based on our large prospective cohort, with a detailed assessment of physical activity, we found that the overall physical activity level slightly decreased between 17–22 and 27–30 weeks’ gestation, particularly in duration and volume of care, outdoor household, and recreational activity. The care, indoor household, and recreational activities constituted the largest proportion of the total activity level. The women who were consistently active throughout pregnancy reported higher levels of activity in all activity modes than those who became active or inactive during pregnancy. Only a few women reported being entirely inactive during pregnancy. Most women continued working during pregnancy and had sedentary jobs with no or little activity that was reported as at least fairly light. The prevalence of women who reached the recommended level of physical activity varied largely based on the definition and intensity used, though by all definitions the majority of women did not reach the recommended level of activity.

Methodological issues

This study used self-reported levels of physical activity, which are subject to recall bias. To reduce potential recall bias, we included telephone interviews and a recall of the past seven days, both of which are believed to produce better recall than postal surveys and recalls over longer time periods (17). Among a sample of pregnant women, the test-retest reliability of the questionnaire and the comparison of the questionnaire to a 1-week diary was generally substantial in agreement. However, the comparison of the questionnaire with the accelerometer displayed lower agreement, a pattern similar to what others have shown (8). The MET values assigned for each activity were not specific to pregnant women, but rather standardized for an average adult, which likely underestimated the activity assessed in MET h/wk, especially in late pregnancy. We used the moderate (4.8–7.1) and vigorous (>7.1) MET categorization based on 20 to 39 year old women to create definitions of moderate and vigorous activity (27) rather than using the categorizations provided by the US Surgeon General’s Report (36) for an adult (moderate 3–6, vigorous >6 METs). However, our sample did include 37 (2.5%) women 40 to 47 years of age and 44 (3.0%) under 20 years of age who may have been misclassified.

Another limitation of this study was generalizability, a common concern among clinic-based studies of pregnant women (31, 32). Analyses carried out using the PIN1 and PIN2 Studies that preceded this PIN3 Study suggest that underrepresented women were more often less educated, younger, African American, had higher parity, and had a higher pregnancy risk profile (31, 32). The PIN3 cohort involved only one of the two primary clinics in the earlier cohorts. This representation bias might have affected our results by providing higher levels of physical activity than may be in a general pregnant population (31).

Our study was strengthened by its prospective design and large cohort, being one of the few studies of this magnitude to study women and their physical activity throughout their pregnancy. Only a few of the previously reported physical activity studies on pregnant women have used a detailed physical activity interview assessing the mode, frequency, duration, and intensity of different modes of activity (6, 8, 16, 28), and none of them have had large sample size with a prospective design.

Comparisons to previous literature

In agreement with our findings, decreasing levels of overall and recreational activity during pregnancy have been reported in previous studies (9, 15, 20–22, 25, 29, 34, 35) in which the decline was mostly explained by the decrease in duration and intensity of recreational activity (13, 21, 22, 25, 35) as opposed to other kinds of activity. Studies on occupational physical activity have been reported in only three previous studies, in which the levels of occupational activity decreased slightly from pre-pregnancy to late pregnancy (7, 9, 20). We found stable levels of occupational physical activity among working pregnant women, yet the levels were extremely low.

We assessed separately the frequency, intensity, and duration of household-related indoor and outdoor activities and care-related activities, which have not been included in detail in any of the previous studies. Some studies have reported sustained levels in household physical activity (7, 9), a shift from heavy to light domestic activity (9), or an increase in combined household and care-giving activity (33). Our findings suggest significant changes in household and care-related activity and mainly decreasing levels for light and total care giving and outdoor household activity. Moreover, our findings suggest that care giving and household physical activity contribute greatly to weekly activity and have an important role in physical activity behavior among pregnant women. Engagement in care giving and household activity was mostly of lower intensity and recreational activity of higher intensity, thus recreational activity becomes an important contributor to energy expenditure particularly when measured by total MET h/wk.

We found few studies that explored change in activity across the different modes, from being active to inactive or from inactive to active (15, 39). One study on a population-based sample of pregnant women suggested that 20% of the women started to exercise, while 40% became less active during pregnancy (15). Another study, using a more selected sample of white rural pregnant women reported that 35% of pregnant women continued their exercise, 45% remained entirely inactive, 13% became inactive, and 7% initiated exercise during pregnancy (39). We reported that most of the women remained physically active in occupational, indoor household, and recreational activity.

Recommended levels of physical activity

Previous estimates of pregnant women reaching the recommended activity levels have been carried out using recreational activity, in which the prevalence has varied from 6% to as high as 78% (12, 25, 26). The study that suggested that 78% of women met the recommended level of activity seems markedly higher than in other reported literature, including our findings. These discrepancies may be due to a selected population or measurement of physical activity. In this study, we used all types of activity to assess the recommended level for the CDC/ACSM definitions and exercise to assess the ACOG definition. The prevalence of sufficient activity varied between 3% and 38%, depending on the type of activity and measurement of intensity included. In our sample, using the combined CDC/ACSM moderate/vigorous intensity definition resulted in higher prevalence than the ACOG moderate intensity exercise definition.

This study provides new information on the physical activity modes among pregnant women, particularly on household, care, and occupational activity. Further research is needed to follow women through pregnancy to postpartum to examine how physical activity levels change and to tailor a physical activity program to those women at risk for inactivity, obesity, and chronic disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the NIH / National Cancer Institute (#CA109804-01). The PIN3 Study was supported by NIH / National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (#HD37584). In addition, the Finnish Cultural Foundation and the Research Academy of Finland are acknowledged for their financial support. The PIN3 Study is a joint effort of many investigators and staff members whose work is gratefully acknowledged. In addition, we thank Lisa Canada for her helpful comments on an earlier draft and the anonymous reviewers. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.ACOG. Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 267. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:171–3. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, et al. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Sports Medicine. Impact of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum on chronic disease risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:989–1006. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000218147.51025.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borg G, Linderholm H. Perceived exertion and pulse rate during graded exercise in various age groups. Acta Med Scand. 1974;472:194–206. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chasan-Taber L, Evenson KR, Sternfeld B, Kengeri S. Assessment of recreational physical activity during pregnancy in epidemiologic studies of birthweight and length of gestation: methodologic aspects. Women Health. 2007;45:85–107. doi: 10.1300/J013v45n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Pekow P, Sternfeld B, Manson J, Markenson G. Correlates of physical activity in pregnancy among Latina women. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11:353–63. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Roberts DE, Hosmer D, Markenson G, Freedson PS. Development and validation of a Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1750–60. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000142303.49306.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke PE, Rousham EK, Gross H, Halligan AW, Bosio P. Activity patterns and time allocation during pregnancy: a longitudinal study of British women. Ann Hum Biol. 2005;32:247–58. doi: 10.1080/03014460500049915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies G, Wolfe L, Mottola M, MacKinnon C. Joint SOGC/CSEP clinical practice guideline: Exercise in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Can J Appl Physiol. 2003;28:330–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evenson KR. The Pregnancy, Infection, and Nutrition Study. UNC Carolina Population Center; 2008. (cited February 29, 2008) Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/pin/docs_3/PIN_PAQ_080907.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evenson KR, Savitz DA, Huston SL. Leisure-time physical activity among pregnant women in the US. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18:400–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evenson KR, Siega-Riz AM, Savitz DA, Leiferman JA, Thorp JM., Jr Vigorous leisure activity and pregnancy outcome. Epidemiology. 2002;13:653–9. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haakstad LA, Voldner N, Henriksen T, Bo K. Physical activity level and weight gain in a cohort of pregnant Norwegian women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:559–64. doi: 10.1080/00016340601185301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinton P, Olson C. Predictors of pregnancy-associated change in physical activity in a rural white population. Maternal Child Health J. 2001;5:7–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1011315616694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer M, McDonald S. Regular aerobic exercise during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006:Art. No.: CD000180. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000180.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kriska A, Caspersen C. Introduction to a collection of physical activity questionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:S5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landis J, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMurray R, Mottola M, Wolfe L, Artal R, Millar L, Pivarnik J. Recent advances in understanding maternal and fetal responses to exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:1305–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mottola M, Campbell M. Activity patterns during pregnancy. Can J Appl Physiol. 2003;28:642–53. doi: 10.1139/h03-049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ning Y, Williams M, Dempsey J, Sorensen T, Frederick I, Luthy D. Correlates of recreational physical activity in early pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003;13:385–93. doi: 10.1080/jmf.13.6.385.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oken E, Ning Y, Rifas-Shiman SL, Radesky JS, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Associations of physical activity and inactivity before and during pregnancy with glucose tolerance. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1200–7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000241088.60745.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Blair SN, Lee IM, Hyde RT. Measurement of physical activity to assess health effects in free-living populations. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:60–70. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereira MA, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Peterson KE, Gillman MW. Predictors of change in physical activity during and after pregnancy: Project Viva. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:312–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen A, Leet T, Brownson R. Correlates of physical activity among pregnant women in the United States. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:1748–53. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000181302.97948.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pollock M, Gaesser G, Butcher J, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand: The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:975–91. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199806000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poudevigne MS, O’Connor PJ. A review of physical activity patterns in pregnant women and their relationship to psychological health. Sports Med. 2006;36:19–38. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200636010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rousham EK, Clarke PE, Gross H. Significant changes in physical activity among pregnant women in the UK as assessed by accelerometry and self-reported activity. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:393–400. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Exercise in pregnancy. RCOG Statement No 4. 2006 (cited July 25, 2007) Available from: http://www.rcog.org.uk/index.asp?PageID=1366.

- 31.Savitz D, Dole N, Williams J, et al. Determinants of participation in an epidemiologic study of preterm delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1999;13:114–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1999.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savitz DA, Dole N, Kaczor D, et al. Probability samples of area births versus clinic populations for reproductive epidemiology studies. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19:315–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt MD, Pekow P, Freedson PS, Markenson G, Chasan-Taber L. Physical activity patterns during pregnancy in a diverse population of women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:909–18. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sternfeld B, Quesenberry C, Jr, Eskenazi B, Newman L. Exercise during pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:634–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Symons Downs D, Hausenblas HA. Women’s exercise beliefs and behaviors during their pregnancy and postpartum. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49:138–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA, USA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Raaij JM, Schonk CM, Vermaat-Miedema SH, Peek ME, Hautvast JG. Energy cost of physical activity throughout pregnancy and the first year postpartum in Dutch women with sedentary lifestyles. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:234–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Savitz D. Exercise during pregnancy among US women. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:53–9. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(95)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]