Abstract

The purpose of this qualitative study is to explore family and peer relationships (including support and influence on risk behavior) among sexually active European American and African American adolescent girls in the context of risk behaviors documented on retrospective event history calendars (EHCs) and in interviews. The EHCs were completed by the adolescents prior to a clinic visit with a nurse practitioner at a school-based clinic in Southeast Michigan, and interviews were conducted after the visit. Constant comparative analysis of EHCs and interview data of 19 sexually active 15 to 19-year-old girls revealed that those with positive familial and peer support were less likely to report risk behaviors compared to those with poor family and peer relationships. School nurses and other providers working with adolescents to prevent risk behaviors could utilize the EHC to determine risks and develop education plans and interventions to reduce risk behaviors.

Keywords: peer relationships, teen pregnancy/parenting, high school, parent/family, school-based clinics, qualitative research, alcohol/tobacco/drug use prevention

As the incidence of adolescent risk behaviors remains high, research on those protective processes that help adolescents avoid or minimize their risk behaviors has increased over the last two decades. Positive parental and peer influence has been shown to reduce the risk of these behaviors in youth. However, the specific influences family members and friends have over an individual adolescent is still being debated in the literature. Furthermore, understanding each individual’s parental and family support can be challenging for practitioners trying to help reduce risk behaviors in an adolescent’s life.

The avoidance of risk behavior by adolescents is thought to be influenced by a variety of factors. However, one common theme that has emerged from the research reveals adolescents with support from family members and friends are more likely to avoid risk behaviors. Researchers have found that warm, communicative parenting as well as adolescents maintaining peer groups that engage in prosocial or positive behaviors encourages adolescents to avoid risk behaviors (Albert, 2009; Bryant & Zimmerman, 2002; Heinrich, Brookmeyer, Shrier, & Shahar, 2006; Kelly & Morgan-Kidd, 2001; Prinstein, Boergers, & Spirito, 2001; Ream & Savin-Williams, 2005; Wills, Resko, Ainette, & Mendoza, 2004).

School nurses and clinicians working from school-based clinics are in a unique position to identify family and peer relationship issues among their population as well as intervene when risk behaviors contribute to health problems. Identification of risk behaviors or poor relationships can facilitate intervention through the use of tailored education or support programs. This study explores family support, peer influence, and risk behaviors among sexually active African American and European American adolescent girls in the context of using the event history calendars (EHCs) to assess lifestyle choices by adolescents. The research aims to extend the understanding of previous studies showing African American and European American adolescents can both positively benefit from family support and positive peer support and provides a tool to evaluate family and peer relationships in adolescents.

EHCs

Typical history taking is often inconsistent and does not include a full risk assessment of sexual activity and illicit substance use (Bull et al., 1999; Lemley, O’Grady, Rauckhorst, Russell, & Small, 1994). Trying to gain a comprehensive picture of an adolescent’s life in minimal time is difficult even for the most seasoned health care provider. Practitioners cite a lack of time in a typical clinic visit as well as their concern that the adolescent will be uncomfortable about questions regarding their sexual health (Bull et al., 1999; Cheng, DeWitt, Savageau, & O’Conner, 1999). Although other history-taking methods exist (such as the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventative Services), these methods are often cumbersome and do not encourage discussion or the ability of the provider to determine how events relate to one another because of the yes or no answers (Martyn, Reifsnider, & Murray, 2006).

Martyn and others (Martyn, 2009; Martyn & Belli, 2002) developed an EHC to assess adolescent risk behavior in an attempt to better analyze patterns of behavior over time and elicit information that would allow open discussion regarding risk reduction and health promotion behaviors. According to Martyn (2009), “A retrospective data collection tool that is contextually and temporally linked and visually shows interrelationships and patterns of behavior and influences is ideal for adolescent risk behavior research …” (p. 76).

The EHC is based upon previous life history calendar research with adolescents as well as themes that Martyn and colleagues derived qualitatively (Martyn, 2009). Completion of the EHC requires the adolescent to use step-by-step instructions, autobiographical memory cues, and retrieval cycles to accurately reconstruct past events and experience (Martyn, Darling-Fisher, Smrtka, Fernandez, & Martyn, 2006). Research on the EHC with both adolescent females and health care providers indicated the tool facilitates recall, report, and communication about risk behaviors and is feasible to use in primary care clinical settings (Martyn, Darling-Fisher, et al., 2006; Martyn, Darling-Fisher, Kristofek, Pardee, Felicetti, & Guys, 2009; Martyn & Martin, 2003;).

The EHC allows the adolescent the opportunity to chronicle their life events over a 4-year period and reflect on the interaction between subjects such as life events, relationships, living situation, sexual activity, and illegal behaviors. The EHC is designed with four vertical columns labeled by sequential years and nine horizontal categories with events, behaviors, and relationships. The first three columns ask the adolescent open-ended questions about their behavior, events, and relationships for the current year and the past 2 years. The final column asks the adolescent to record what their goals are for the following year.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Jessor (1991) proposed that the adolescent’s risk and protective factors, risk behaviors (i.e., problem behavior, health-related behavior, and school behavior), and risk outcomes (i.e., health, social roles, personal development, and preparation for adulthood) are interrelated in his Problem Behavior Theory. The risk factors and protective factors contribute to the risk behaviors, and the risk behaviors contribute to the risk and protective factors in a reciprocal relationship. Risk outcomes subsequently form a reciprocal relationship with risk behaviors. This qualitative study utilized Jessor’s social environment risk and protective factors as a framework to examine the risk behaviors and protective factors present in young women’s lives.

METHOD

Secondary analysis of EHCs, interview data, and memos were conducted to examine family support and peer influence and their relationship to risk behaviors (including sexual activity, drugs, alcohol, and other illegal behaviors) from a sample of African American and European American adolescent female participants involved in a larger study on EHC clinical utility. The larger study was conducted to explore the effects of the EHC intervention on adolescent-provider communication and avoidance of unprotected intercourse postintervention (Martyn et al., 2009). The Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan granted approval for the research protocol. Informed consent/assent was obtained from all the participants and confidentiality was maintained throughout the research project.

Sample

The 19 females in this study were one group of a larger study’s sample of 30 adolescents. The original study recruited 11 males and 19 females from a school-based clinic in southeastern Michigan (see Table 1). The clinic provides primary health care to low-middle-income patients between the ages of 10 and 21 years old. Each year, the clinic provides unduplicated care to approximately 2,000 adolescents.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Information

| Variables (N = 19) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean age (years) | 17.32 |

| Range | 15–19 |

| Ethnicity | |

| European American | 13 (68.4%) |

| African American | 6 (31.6%) |

| Employmenta | |

| Student | 17 |

| Part-time work | 4 |

| Full-time work | 0 |

| Unemployed | 2 |

| Living situationa | |

| Lived with parents | 15 |

| Lived with other family | 4 |

| Lived with partner | 2 |

| Subsidized lunch | |

| Yes | 10 (52.6%) |

| No | 9 (47.4%) |

| Health insurance | |

| Medicaid | 7 (36.8%) |

| Private | 8 (42.1%) |

| None | 1 (5.3%) |

| Unknown | 3 (15.8%) |

Denotes categories that participants marked more than one response.

Procedures

Adolescents who were referred by staff members or self-referred from the flyers were screened for eligibility and explained the study by a trained research assistant. Eligibility requirements included being 15–19 years old, sexually active, and in the clinic for a primary health care visit. All the adolescents who participated in this study identified at least one biological relative as a family member. Those adolescents who agreed to participate in the study signed an informed consent. The adolescents were then given the EHC, a pen, and instructions to self-administer the EHC prior to their visit with a nurse practitioner who was trained on the EHC and study procedures.

During a clinic visit, the adolescent met with a nurse practitioner trained in the EHC method. Additional history information was obtained and notes were made on the EHC to clarify or supplement the data. Following the clinic visit, the adolescents participated in an informal, semi-structured interview with the research assistant that included questions on the efficacy and utilization of the EHC in the school-based health care center. The research assistant asked participants questions such as “How do you think using the history calendar helps you talk to the nurse practitioner?” and “What do you think of the history calendar format” during the interview. These interviews were included in the secondary analysis. The interviews were conducted in a private clinic room, lasted approximately 15–20 min, and were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim within 48–72 hr. Additional information from conversations with the adolescents, along with impressions of the adolescent’s nonverbal and body language was noted in memos by the research assistant for each participant. Upon the completion of the visit, participants were given a $25 gift card.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was guided by the research question, “What family support and peer influence are relevant for African American and European American adolescent females?” Constant comparative method (Glaser, 1978, 1992) was used to identify themes and trends of family support, peer influence, and risk behavior in the adolescents’ EHCs and interviews. Data were first transcribed to the investigators own excel spreadsheet format arranged similarly to the actual EHC. Each column’s response was typed verbatim into an excel file for ease of reading. Comments by the nurse practitioner were typed in a different font and color to differentiate their remarks from those of the adolescent. Each calendar was labeled with the participant’s research number. No other identifying information was on the transcribed calendar data.

The group of 19 calendars was first reviewed line-by-line for general impressions of trends and themes of relationships and risk behaviors. Each EHC was examined individually for quality and change over time in family and peer relationships and categorized as positive and negative relationships (Cresswell, 2003). Positive relationships were denoted by the girl circling family members as important in their lives or stating in the interview the importance of their family members. Negative relationships were denoted by the girl not including family members as important people in their lives or stating in the interview that they had a poor or negative relationship with their family members. For example, if an adolescent lived with both parents and noted on the EHC that her parents were influential in her life by circling “mom and dad,” the relationship was noted. Conversely, if an adolescent marked on her EHC that she lived with both parents but had a negative relationship with her parents (based upon the negative events column, the adolescent’s own comment, or from the nurse practitioner’s remarks on the EHC), this was also noted.

Parental relationships were defined as the relationship between the adolescent and her primary caregivers (i.e., who she primarily lived with for the majority of the 3-year EHC). Therefore, grandparents and legal guardians were considered parents in this study. For example, an adolescent who lived with and had a positive relationship with both her mother and father would be in the same category as an adolescent who lived with her supportive grandmother (for the majority of the 3-year EHC) and had a negative relationship with her mother and father. If one parent was positive and one was negative, the memos from the research assistant and EHC were studied closely to find clues regarding their home life. If EHC events and history indicated predominantly negative relationships, the girl was placed in the category of negative relationships.

After using the EHC to show positive and negative relationships between the girls and their family members, the girl’s peer groups were analyzed. Changes in peer groups were noted as well as changes in boyfriends and other sexual partners. That is, if the adolescent had different friends each year or had multiple sexual partners she deemed important in her life (based upon who she circled as most important on the EHC), the trend was noted.

Finally, risk behaviors and sexual activity were compared with the family and peer groups. Categories were developed and trends were noted when decreased family and peer support was indicated on the EHC and adolescent risk behavior increased. After examining the EHC, the research assistant interviews and memos were examined line-by-line for each participant. Additional categories were developed and trends were noted based upon the memos and interviews on each individual calendar as well as the positive and negative qualities of peer and family relationships.

Prior to reviewing the calendars, it was decided if an adolescent had positive family support but deemed her peer influence negative (or vice versa), the first author would consult the interviews, memos, and nurse practitioner’s comments to determine whether family or friends seemed most influential in the adolescent’s life. After noting trends and themes on individual EHCs, the primary investigator grouped the EHCs into two overall groups: those with support and those without support. Trends and themes associated with the adolescents’ risk behaviors were noted within groups. The data were then compared within and between the two groups to find similarities and differences among the adolescents in the study (Cresswell, 2003). Consistencies were most likely to occur among adolescents in the same group; whereas stark contrasts were found among girls from different groups.

RESULTS

Data from the EHCs, interviews, and memos provided information about each adolescent’s family and peer support networks over the last 3–4 years as well as their risk behaviors. According to Jessor’s (1991) Problem Behavior Theory, the social environment influences adolescent’s risk behavior. Risks such as negative family and peer support can be balanced by the protective processes of positive family and peer support. In this study, 5 of the 19 participants reported positive family and peer relationships; whereas the other 14 had negative family support, negative peer influence, or both. Positive relationships were defined as relationships that lasted the course of 3 years and considered positive by the adolescents.

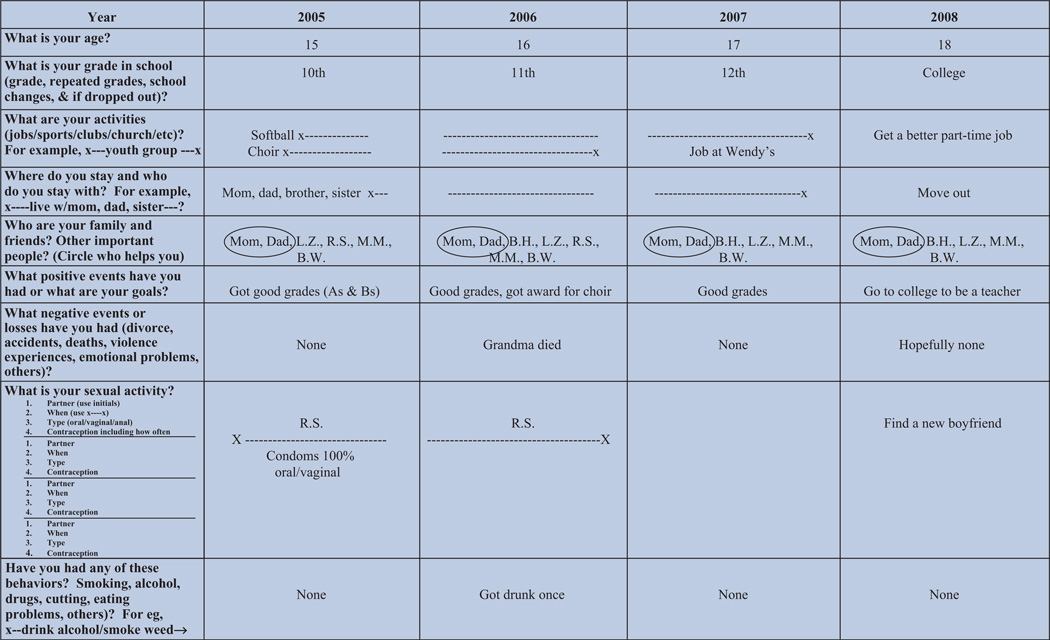

Girls With Support

Of the 19 participants, 5 (2 African American and 3 European American) reported positive family and peer relationships (as evidenced by who they lived with for all 3 years and important family members and friends reported on the EHC). These same five individuals reported fewer risk behaviors (e.g., tobacco/alcohol/illicit drug use, sexual activity, contraceptive use, and physical violence toward oneself or others) compared to their counterparts (see Figure 1). Various themes emerged from the girls with support group including achievement, avoidance of risk, and family approval.

Figure 1.

Sample of EHC data reported by girls with support over 4 years. Note: EHC = event history calendar.

Achievement

Those adolescents with positive family and peer support valued achievement and looked toward their future when considering risks. All of the five participants with positive family and peer support were successful in their current high school academics or graduated from high school. One participant, age 19 years old reported living with her mother and brother, had two sexual partners in 3 years, used birth control 100% of the time, tried marijuana when she was 17 once, and occasionally drank alcohol. She believed her positive family support and friends helped her graduate with a 4.0 from high school and aided her acceptance into college. Her EHC illustrated her minimal risk behaviors as well as her positive relationships with her mother and brother. Subsequently, she had no negative life events and multiple goals for the future in the fourth year of the EHC.

The other four participants had similar stories as the 19-year-old. Two of the participants with minimal risks stated their parents were strong support systems for them and helped them achieve their goals. One had a close relationship with her mother, although no father was present in her life. The other participant also stated her parents and best friend were her support system. Although both were sexually active, one participant used birth control 100% of the time and the other used birth control 75% of the time. Neither girl drank alcohol, used tobacco products, or used drugs. Both graduated from high school and were either going to college or getting a job. Both girls had solid friendship networks which provided positive peer support. Having prosocial friends and positive relationships with their parents influenced these girls to finish school and look for future opportunities.

Avoidance of risk

Family and peers were instrumental in helping adolescents avoid risk behaviors. One 19-year-old who lived with her mother and stepfather believed that her friends and family encouraged her to avoid risk behaviors because of their own attitudes toward negative behaviors like using illicit substances or smoking. She was proud that she did not smoke or get high and stated that she “worries what her parents would think if she had negative behaviors and took risks.”

A 17-year-old participant who lived with her father and grandmother stated that it was important for adolescents to have someone to talk to and rely on. This adolescent used Depo-Provera birth control for all 3 years and condoms the majority of the time. She had four sexual partners in 3 years. During the 3-year EHC, this adolescent lost a close aunt, her grandfather, and a close friend. Despite her losses, she was able to talk to people when she was sad and did not turn to risk behaviors.

She stated that the EHC was a helpful tool for showing why people may or may not choose to have sex. She believed that “being depressed or not having people to talk to you” were reasons that others might turn to risk behaviors. Having a positive support system at home allowed the adolescent to discuss issues and problems with people who would support her. This adolescent illustrates the importance of family support and peer groups on risk behaviors. By having supportive family members, this adolescent made the choice to avoid high-risk situations such as unprotected sex and illicit substance use.

Family approval

Finally, family approval emerged as a theme that was important to the adolescents. One 19-year-old stated that having family was essential. She said,

Cause on that calendar, if someone were to write down no one or only has just friends with them, they wouldn’t have family support. And maybe, that’s why negative things have happened to them.

Most of the girls stated they knew if they did something wrong their family members would be upset with them. They followed the rules set by their families because they wanted to maintain the positive relationships.

According to Jessor’s (1991) PBT, the family and peer support the girls experienced helped counterbalance any risk factors they might be experiencing. These girls in particular had strong familial relationships that allowed them to build strong relationships. Their peers also tended to be similar to them. That is, they exhibited fewer risks per the participants EHC, interview, and memos.

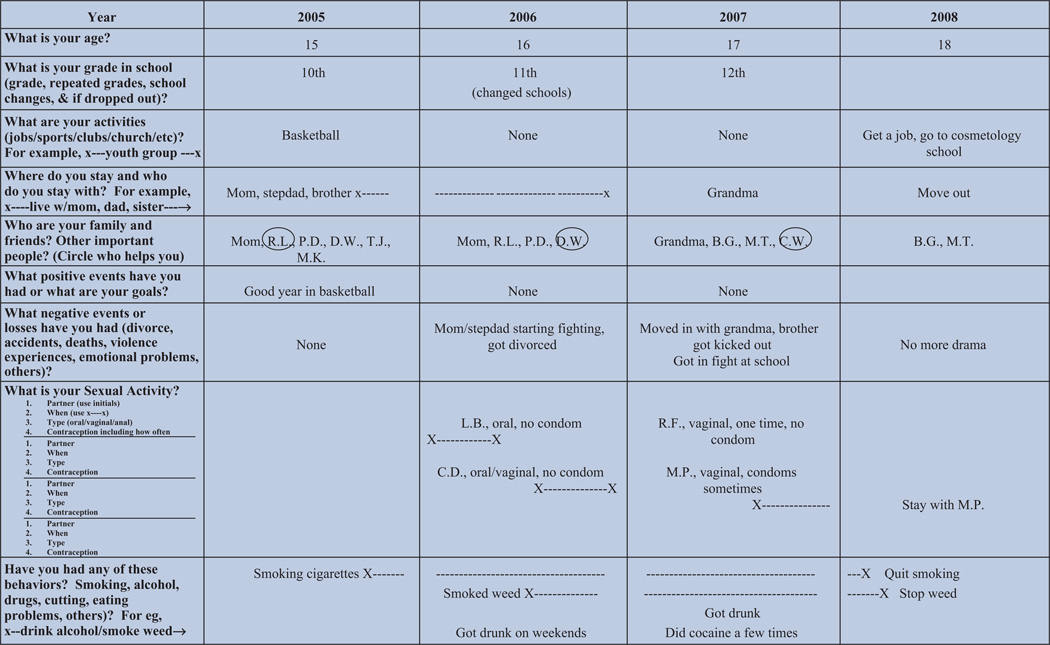

Girls Without Support

Of the 19 participants, 14 reported negative family relationships and/or negative peer influences (as evidenced by their reported living situations over a 3-year period and who they deemed important among friends and family members on the EHC). The 14 adolescents’ risk behaviors varied within the group. Of the girls without support, 12 stated they used alcohol, 9 used illicit substances, and 11 smoked tobacco products (see Figure 2). Illegal substances included marijuana, inhalants, cocaine, crack cocaine, and prescription pain medications. There was no indication of how often the participants smoked, used drugs, or drank alcohol. However, unlike the adolescents with family support who used words like “occasional” or quantified their experiences to “once or twice a year,” only 2 of the 14 females with negative parental or peer relationships reported their substance use as infrequent or occasional. Of the participants, 4 were African American and 10 were European American. The themes that emerged among this group included poor communication with parents, peer pressure, and few role models.

Figure 2.

Sample of EHC data reported by girls without support over 4 years. Note: EHC = event history calendar.

Poor communication

Communication was cited by the adolescents as lacking in their relationships with their parents. One girl stated that she had good peer support but minimal family support. She moved between her father and mother’s houses, but did not like staying with her father because she could not relate to him and she did not get along with her mother. She felt stuck and turned to men for comfort. She had been involved with four sexual partners at age 14, used contraceptives rarely, and had been treated for one sexually transmitted infection. When discussing her thoughts on parental communications she said, “You can’t trust everybody. You think you can trust the closest people, but you can’t.” Her lack of family support influenced her to seek approval elsewhere. She stated, “If you talk to a kid, they’ll tell you.” However, she did not have open lines of communication with her family and turned elsewhere for support.

Another participant who had very little family support and a fluctuating living situation turned to alcohol and smoking after her boyfriend of 2 years broke up with her. Her relationships with adults were minimal, and she did not have a strong support system to turn to while she dealt with the emotions of losing a boyfriend. However, this participant did think having adult support would be helpful in adolescent’s lives. She stated,

You can get enough information … Can talk to them like about smoking, drinking, sex-it would be better for them to communicate.

Adolescents in the study cited a desire to communicate with adults. However, they often remarked on a lack of opportunity to open a dialogue. The participants also noted that sensitive subjects such as sex and drugs would be particularly important to discuss with adolescents searching for information.

Many of the participants who engage in risk behaviors reported disruptions in their home life. One participant had repeated physical fights with her brother and verbal fights with her father. She moved back and forth between her parent’s house, her boyfriend’s house, and her aunt’s house. During the time she was moving around, she increased her risk behaviors by smoking cigarettes, smoking marijuana, and cutting herself. She tried to kill her brother and herself and battled depression. Her family support was minimal and peers were not even mentioned on her EHC as people who were important to her. Adolescents, who are depressed or have an affinity toward violence, struggle when they do not have positive peer influences or family support (Herrenkohl, Hill, Hawkins, Chung, & Nagin, 2006; Prinstein et al., 2001; Smith, Flay, Bell, & Weissberg, 2001; Snyder & Rogers, 2002). They have no one to talk to about their problems and often see violence as an acceptable outlet for their depression, pain, or anger.

Peer pressure

Risk behaviors might have been viewed as a way for the adolescents in this study to be accepted by their peer group or maintain their friendships. One 19-year-old participant had 22 sexual partners, been diagnosed with human papillomavirus, drank alcohol, smoked occasionally, and had given birth to her first child. She stated that she felt a huge amount of peer pressure. She said,

If you have more bad influences, it kind of shows what you were probably doing during that time, whether you were smoking, drinking, or had more sexual partners, or something like that.

She also revealed that

In between 16 and 17, I had a lot of school activities going on. But I was more susceptible to the negative influences in my life because I had a lot of friends too.

Many of the adolescents in the study cited a lack of communication with their families or feeling alone and vulnerable to peer pressure as a reason why they engaged in risk behaviors. The lack of a stable home life influenced adolescents to turn elsewhere for the love and support they desired. Risk behaviors might have been viewed as a way for the adolescents in this study to be accepted by their peer group or maintain their friendships.

Although peer pressure generally carries a negative connotation, it can often be positive. One 16-year-old participant stopped cutting, drinking alcohol, and smoking marijuana and cigarettes when she began dating her current boyfriend. Another 17-year-old who had a negative relationship with her mother, used illicit substances, had issues with violence toward others, and had multiple sexual partners stopped her risk behaviors when she entered into a monogamous relationship with her current boyfriend. She stated that they were trying to be more responsible by avoiding drugs, alcohol, and violence. Having one support person, in these cases a boyfriend, helped these adolescents make good decisions that counterbalanced their negative relationships with family members and peers. These example shows that even one positive person in an adolescent’s life can help steer them away from risk behaviors.

According to Jessor’s (1991) PBT, placing value on health and achievement are protective processes that can counter risk-taking propensity and risk behaviors. Having a positive peer influence in your life can encourage adolescents to make wise decisions on what activities to engage in. However, the converse can also be true. Those whose friends were entering into risk behaviors often bowed to the peer pressure and participated in the activities as well.

Poor role models

Adolescents in this study looked up to their family members and were often disappointed. One participant, an 18-year-old, lived with her mother, father, and brother during the 3-year EHC. At the age of 15, the participant started to smoke, use alcohol, and experiment with marijuana and vicodin. By the time she was 16, she added cocaine and crack cocaine to the list of substances she abused and by 18 she was in a rehabilitation center for her drug addiction. She had two drunk-driving accidents in a year, overdosed, and dealt with a miscarriage at 4 months gestation.

The participant stated that her sister “is one of the reasons why I am who I am today.” Her sister, a drug addict, is not welcome at her family’s home, but influenced this participant before she left. The adolescent stated that she does not get along with her brother or her father, and did not mention on her EHC how her relationship with her mother was. However, she did not list her mother as someone important in her life. Having a sibling who encourages risk behaviors and unstable family relationships can make it difficult to make positive choices.

Another adolescent, age 14 years old, stated she had a bad relationship with her mother, marked with fighting and a lack of discussion among them. Her father is currently in jail, and she stated that she hates him. According to the EHC, her peer group changed on an annual basis. She was molested by her stepgrandfather in the eighth grade and at the same time began having oral, vaginal, and anal sex. She stated that her body was the only thing she was good for. This adolescent’s adult role models (mother, father, and stepgrandfather) failed her, leaving her without valuable, positive relationships.

The adolescent females who engaged in risk behaviors and had a lack of family support, peer support, or both each had other external or social environmental factors influencing their behaviors. Multiple participants had deaths in the family or among very close friends, incidents of molestation or rape, or friendship crises during their 3-year EHC. Although not the focus of this study, these social environmental factors cannot be overlooked as contributors to increased risk behaviors. However, family support, or lack of support and the positive and negative influences of friends was a predominant theme throughout the EHCs and interviews among all those who showed high and low levels of risk behavior in the study.

According to Jessor (1991), the adolescents who did not have family support or positive peer influence did not receive the protective effect that these groups can offer to adolescents. The risk factors that were present such as racial inequality, illegitimate opportunity, poverty, and normative anomie were not counterbalanced by any or enough protective processes. As a result, trends showed that adolescents who engaged in more risk behaviors had lower impressions of themselves, higher rates of violence toward themselves or others, higher school failures, and higher rates of health issues (e.g., sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy, etc.).

DISCUSSION

This exploratory, qualitative study revealed supports, influences, and risk behaviors among adolescent females and meanings of these for the participants through the use of EHCs. Those adolescents who reported positive family relationships on their EHCs as well as positive peer influence more frequently abstained from unprotected sexual activity, substance use, and other risk behaviors. Those with negative family relationships and peer influences engaged in risk behaviors more often than their counterparts with support.

Adolescent risk behavior is multifactoral (Jessor, 1991). However, this study has shown that family support and positive peer influence can greatly influence adolescent behavior. Consistent with other research findings (Devore & Ginsburg, 2005; Heinrich et al., 2006; Martyn, Reifsnider, Barry, Trevino, & Murray, 2006; Prinstein et al., 2001; Ream & Savin-Williams, 2005; Wills et al., 2004), positive family and peer support is important to adolescent well-being.

School nursing implications

School nurses and clinicians working in school settings could use the EHCs to improve adolescent assessment and intervention. The tool takes approximately 10–15 min to complete by adolescents and 2 min to review by the provider (Martyn, Reifsnider, et al., 2006). It allows the provider to view the adolescent’s life and risk behavior broadly and gives the adolescent the opportunity to simultaneously assess their lifestyle choices (Martyn, Reifsnider, et al., 2006).

Although school nurses are working in settings where they have access to adolescents, there are often time constraints placed on visits. A typical history form can be long and cumbersome for the adolescent to complete. They often ask only yes or no questions and are handed to the provider for a quick review without further discussion. The EHC was developed specifically as a way to begin the discussion about risk behaviors with an individual adolescent and continue the discussion throughout the health care visit (Martyn & Martin, 2003). Current work with the EHC has found that participants find the EHC easy to use and believe that it helped them discuss sensitive topics with the nurse practitioner. The research assistant discussed the ease of EHC use with the participants, and all the females enrolled in the study agreed that the EHC helped their health care visit.

The EHC also acts as a starting point for communication between the provider and the patient. For example, one girl responded that she had less than four sexual partners on the EHC. However, once the nurse practitioner probed the adolescent on her sexual behavior, the girl shared her history of 15 sexual partners. Whether or not the girl would have shared her experience without the initial completion of the EHC is debatable. But the EHC offers the adolescent a chance to “warm-up” to the idea of talking about sex and other risk behaviors.

In this particular research study, the EHC was used as a way to gauge peer and family support. Assessing each adolescent’s family and peer relationships is important to understand risk behaviors and potential health implications. It is important for providers to ask questions about the adolescent’s home life and peer support network and to find areas where the adolescent needs additional support. In schools and school-based clinics, those who are lacking positive family or peer support or have other risk factors that are worrisome to health care providers could be referred to social work services, trained school counselors, or even scheduled at a later time to meet with the health care provider to further evaluate risk behaviors and develop a plan to assist the adolescent.

Adolescents will most likely not be able to change their family support system. But, as the nurse working within the school system, the identification of deficiencies in an adolescent’s life can lead to significant follow-up and support. Similarly, school-based interventions could be developed to help build relationships between the adolescent, the family, and the school staff. These interventions would have to be school specific and based upon the resources and the issues specific to the region’s adolescent population.

Using the EHC allowed providers to obtain a snapshot of the adolescent’s family and peer group with minimal intrusion on the adolescent. The nurse or clinician is able to elicit more information from the adolescent in a nonthreatening way using the EHC that allows for further discussion in the actual clinic visit.

FUTURE RESEARCH

Future research should focus on using the EHC with various providers in school-based clinics as well as in other clinics that serve adolescent populations. The current research with the EHC should be repeated but with a larger sample size and a more diverse population. Intervention research would be specifically useful in regions where adolescents have a disproportionately high amount of alcohol/drug use and pregnancy rates. Interventions on ways to encourage family communication and ensure peer support is positive rather than negative could decrease risk behaviors and potential injury. Finding ways to encourage adolescents and adults to engage in family communication would be imperative for future research. Interventions that train parents on appropriate parenting techniques and communication skills could positively affect family relationships.

CONCLUSION

Adolescents with family support and positive peer influence engaged in less risk behaviors. The adolescents who valued achievement, consciously avoided risk, and sought family approval are more likely to make better choices about their health and their bodies. Alternately, those who succumb to negative peer pressure, lack communication with their family, and have poor role models are more likely to engage in risk behaviors that endanger their long-term health. In this study, adolescents who had positive family and peer support were more likely to complete school, use contraception, and forgo substance abuse. Family and peer support was the common theme that facilitated positive life choices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the following grant support by the National Institute of Nursing Research, The Michigan Center for Health Intervention, P30 NR009000 awarded to K. K. Martyn, PhD, FNP-BC, CPNP-PC, PI.

Contributor Information

Melissa Ann Saftner, University of Michigan, School of Nursing, North Ingalls, Ann Arbor, MI, USA..

Kristy Kiel Martyn, Health Promotion and Risk Reduction at the University of Michigan, School of Nursing, North Ingalls, Ann Arbor, MI, USA..

Jody Rae Lori, University of Michigan, School of Nursing, North Ingalls, Ann Arbor, MI, USA..

REFERENCES

- Albert B. With one voice (lite) 2009 Retrieved from http://www.thenationalcampaign.org.

- Bryant AL, Zimmerman MA. Examining the effects of academic beliefs and behaviors on changes in substance use among urban adolescents. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2002;94:621–637. [Google Scholar]

- Bull SS, Rietmeijer C, Fortenberry JD, Stoner B, Malotte K, Vandevanter N, Hook EW., 3rd Practice patterns for the elicitation of sexual history, education, and counseling among providers of STD services: Results from the Gonorrhea Community Action Project (GCAP) Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1999;26:584–589. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199911000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TL, DeWitt TG, Savageau JA, O’Connor KG. Determinants of counseling in primary care pediatric practice: Physician attitudes about time, money, and health issues. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153:629–635. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Devore ER, Ginsburg KR. The protective effects of good parenting on adolescents. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2005;17:460–465. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000170514.27649.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs. forcing. Mill Valley, CA: The Sociology Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Advances in the methodology of grounded theory: Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley, CA: The Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich CC, Brookmeyer KA, Shrier LA, Shahar G. Supportive relationships and sexual risk behavior in adolescence: An ecological-transactional approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:286–297. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Hill KG, Hawkins JP, Chung IJ, Nagin DS. Developmental trajectories of family management and risk for violent behavior in adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12:597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PJ, Morgan-Kidd J. Social influences on the sexual behaviors of adolescent girls in at-risk circumstances. Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecological, and Neonatal Nurses. 2001;30:481–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemley KB, O’Grady ET, Rauckhorst L, Russell DD, Small N. Baseline delivery of clinical preventive services provided by nurse practitioners. Nurse Practitioner. 1994;5:57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK. Adolescent health research and clinical assessment using self-administered event history calendars. In: Belli R, Stafford F, Alwin D, editors. Calendar and time diary methods in life course research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Belli RF. Retrospective data collection using event history calendars. Nursing Research. 2002;51:270–274. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Darling-Fisher C, Kristofek K, Pardee M, Felicetti IL, Guys M. Sexual risk history approach that improves teen-provider communication and outcomes. National presentation at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2009 National Conference; Washington, DC. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Darling-Fisher C, Smrtka J, Fernandez D, Martyn DH. Honoring family biculturalism: Avoidance of adolescent pregnancy among Latinas in the United States. Hispanic Health Care International. 2006;4:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Martin R. Adolescent sexual risk assessment. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2003;8:213–219. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Reifsnider E, Barry MG, Trevino MB, Murray A. Protective processes of Latina adolescents. Hispanic Health Care International. 2006;4:111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Reifsnider E, Murray A. Improving adolescent sexual risk assessment with event history calendars: A feasibility study. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2006;20:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Spirito A. Adolescents’ and their friends’ health-risk behavior: Factors that alter or add to peer influence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2001;26:287–298. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.5.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ream GL, Savin-Williams RC. Reciprocal associations between adolescent sexual activity and quality of youth-parent interactions. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:171–179. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P, Flay BR, Bell CC, Weissberg RP. The protective influence of parents and peers in violence avoidance among African-American youth. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2001;5:245–252. doi: 10.1023/a:1013080822309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Rogers K. The violence adolescent: The urge to destroy versus the urge to feel alive. American Journal of Psychoanalysis. 2002;62:237–253. doi: 10.1023/a:1019876300995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Resko JA, Ainette MG, Mendoza D. Role of parent support and peer support in adolescent substance use: A test of mediated effects. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:122–134. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]