Abstract

Prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) has adverse effects on the development of numerous physiological systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the immune system. HPA hyper-responsiveness and impairments in immune competence have been demonstrated. The present study investigated immune function in PAE females utilizing an adjuvant-induced arthritis (AA) model, widely used as a model of human rheumatoid arthritis. Given the effects of PAE on HPA and immune function, and the known interaction between HPA and immune systems in arthritis, we hypothesized that PAE females would have heightened autoimmune responses, resulting in increased severity of arthritis, compared to controls, and that altered HPA activity might play a role in the immune system changes observed.

The data demonstrate, for the first time, an adverse effect of PAE on the course and severity of AA in adulthood, indicating an important long-term alteration in functional immune status. Although overall, across prenatal treatments, adjuvant-injected animals gained less weight, and exhibited decreased thymus and increased adrenal weights, and increased basal levels of corticosterone and adrenocorticotropin, PAE females had a more prolonged course of disease and greater severity of inflammation compared to controls. In addition, PAE females exhibited blunted lymphocyte proliferative responses to concanavalin A and a greater increase in basal ACTH levels compared to controls during the induction phase, before any clinical signs of disease were apparent. These data suggest that prenatal alcohol exposure has both direct and indirect effects on inflammatory processes, altering both immune and HPA function, and likely, the normal interactions between these systems.

Keywords: prenatal alcohol (ethanol) exposure, stress, adjuvant-induced arthritis, HPA axis, neuroimmune function, fetal programming

Impairments in immune competence of children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) are demonstrated broadly in both innate and adaptive immunity. For example, children exposed prenatally to alcohol have an increased incidence of bacterial infections, such as meningitis, pneumonia, otitis media, gastroenteritis and sepsis, as well as urinary tract and upper respiratory tract infections (Johnson et al., 1981; Church and Gerkin, 1988). As well, these children have lower eosinophil and neutrophil counts, decreased circulating E-rosette-forming lymphocytes, reduced mitogen-stimulated proliferative responses of peripheral blood leucocytes and hypogammaglobulinemia (Johnson et al., 1981).

Research using rodent models of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) has substantiated the clinical evidence of impaired immunity associated with FASD. Delayed thymic ontogeny, decreased total numbers of splenic and thymic T cells, decreased thymus weight, size, and cell counts, and suppressed B cell development have all been observed in fetuses and newborns exposed to alcohol in utero (Ewald and Walden, 1988; Ewald and Huang, 1990; Clausing et al., 1996; Moscatello et al., 1999). These changes may persist into adolescence and adulthood, and additional immune deficits, including altered responses to the intestinal parasite, Trichinella spiralis and deficits in mitogen-induced lymphocyte and lymphoblast cell proliferation to mitogens, may be revealed as the animal matures (Ewald and Frost, 1987; Ewald, 1989; Norman et al., 1989; Redei et al., 1989; Gottesfeld et al., 1990; Weinberg and Jerrells, 1991; Steven et al., 1992; Redei et al., 1993; Giberson and Blakley, 1994; Clausing et al., 1996; Seelig et al., 1996; Jerrells and Weinberg, 1998; Taylor et al., 1999). Moreover, exposure to stressors, including cold stress and chronic intermittent stress, may exacerbate immune deficits in PAE compared to control animals (Giberson and Weinberg, 1995; Giberson et al., 1997).

The present study aimed to expand our understanding of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the functional status of the immune system. We utilized an adjuvant-induced arthritis (AA) model, widely used as a model of human rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Like human RA, AA in the rodent is an inflammatory disease of the joints, especially the hind paws, shown to be mediated by CD4+ T cells. AA has been used to study disease pathogenesis, chronic pain and/or stress, and, in view of the involvement of the HPA axis in arthritis, neuroendocrine imbalance, as well as altered interactions between the neuroendocrine and immune systems (Harbuz et al., 1993; Chover-Gonzalez et al., 1999; Chover-Gonzalez et al., 2000; Harbuz et al., 2003; Bomholt et al., 2004).

Evidence in humans suggests that alcohol consumption in adulthood may be protective in relation to RA risk and severity. Moderate alcohol consumption not only resulted in a dose-dependent inverse association with risk and severity of RA, but also attenuated the adverse effects of smoking, a well-established risk factor for RA (Kallberg et al., 2009; Maxwell et al., 2010), and reduced markers of inflammation in women with preclinical RA (Lu et al., 2010).

By contrast, the effects of prenatal exposure to alcohol on risk for and development of arthritis have not been directly investigated. However, data from animal studies suggest that PAE is likely to have pro-inflammatory rather than anti-inflammatory effects, possibly mediated by altered neuroendocrine-immune interactions. For example, greater adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) and/or corticosterone (CORT) responses to immune signals such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Lee and Rivier, 1996; Yirmiya et al., 1998; Kim et al., 1999), and greater increases in plasma levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines following LPS challenge (Zhang et al., 2005) have been observed in PAE compared to control offspring. As well, embryos exposed in vitro to alcohol had greater tissue levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IL-6 than control embryos (Vink et al., 2005). Increased pro-inflammatory responses to stressors and immune signals is reminiscent of the HPA hyperresponsiveness to stressors typically observed in PAE animals (Weinberg et al., 2008) and in fetal alcohol-exposed infants (Ramsay et al., 1996; Jacobson et al., 1999). Alcohol exposure in utero has been shown to program the fetal HPA axis such that HPA tone is increased throughout life (Weinberg et al., 2008), resulting in greater HPA activation and deficits in recovery following stress, as well as altered central HPA regulation. Of note, Schneider and colleagues (Schneider et al., 2002; Schneider et al., 2004) showed in a primate model that moderate prenatal alcohol exposure, prenatal stress, or both result in dysregulation of neurobiological systems related to stress, and that the mechanisms underlying the adverse effects of PAE and prenatal stress overlap. These findings are relevant, as both prenatal and early life stress and adversity have been linked with pro-inflammatory changes in the pregnant female and her offspring, in both humans (Chen et al., 2006; Coussons-Read et al., 2007; Danese et al., 2007; Bellinger et al., 2008; Dube et al., 2009) and animal models (Vanbesien-Mailliot et al., 2007; Bellinger et al., 2008; Merlot et al., 2008), including increased severity of adjuvant-induced arthritis (Seres et al., 2002).

In the context of the known effects of PAE on HPA and immune function, as well as the interaction between the HPA and immune systems in arthritis, we hypothesized that in utero alcohol exposure would increase the autoimmune response compared to that in control offspring, resulting in enhanced severity of AA. The clinical manifestations of arthritis, as well as immune markers and HPA hormone levels were assessed over the course of inflammation. Our data demonstrate that, whereas adjuvant injection, as expected, had marked effects on immune measures across all prenatal groups, prenatal exposure to alcohol significantly increased the course and severity of disease.

Materials and Methods

Animals: Breeding and Feeding

Adult Sprague-Dawley male (350–375 g) and female (250–275 g) rats were obtained from the Animal Care Center, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada and group housed by sex for a 1- to 2-week adaptation period, during which they were given ad libitum access to standard laboratory chow (Jamieson's Pet Food Distributors, Ltd., Delta, BC, Canada) and water. Details of the breeding and handling procedures have been previously published (Glavas et al., 2007). Briefly, adult females were co-housed with males in stainless steel suspended cages with mesh fronts and floors, and wax papers beneath the cages were checked daily. Presence of vaginal plugs indicated day 1 of gestation. Females were then housed singly and assigned to one of three groups: 1) Control (C): laboratory chow, ad libitum; 2) Pair-fed (PF): liquid control diet, with maltose-dextrin isocalorically substituted for alcohol, in the amount consumed by a PAE partner (g/kg body weight/day of gestation); 3) Prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE): liquid ethanol diet (36% ethanol-derived calories), ad libitum. Females in all groups had ad libitum access to water. The liquid diets were formulated to provide adequate nutrition to pregnant dams regardless of alcohol intake (Ethanol Diet #710324, Control Diet #710109, Dyets Inc. Bethlehem, PA). Diets were administered from days 1–21 of gestation and thereafter, animals received laboratory chow and water ad libitum. Pregnant females were weighed on gestation days (GD) 1, 7, 14, and 21. At birth, designated postnatal day (PND) 1, litters were weighed and culled (5 males and 5 females when possible). From weaning (PND 22) until the start of testing, pups were group-housed by litter and sex, 2–3 rats per cage.

Experimental design and induction of AA

AA was induced by injection of complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA), as demonstrated previously (Banik et al., 2002). Clinical signs of arthritis (foci of redness, edema and swelling) in the paw joints typically first appear 10–14 days following CFA injection and clinical signs of AA typically subside, at least partially, at about 28–30 days after injection..

The subjects were female offspring from C, PF and PAE prenatal groups, 50–65 days of age at the start of testing. CFA was prepared by grinding the powdered form of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37 Ra (Difco laboratory, Detroit, MI) with a mortar and pestle, and then dissolving it in 1 ml mineral oil (Difco laboratory, Detroit, MI). For induction of AA, 0.1 ml of a 12 mg/ml suspension of CFA was injected intradermally at the base of tail; 0.1 ml of saline was injected at the base of tail for animals in the saline control group. All animals were singly housed after injection. Three cohorts of C, PF and PAE females were run in overlapping subsets: one cohort was terminated on day 7 (induction phase, no clinical signs of arthritis); one cohort was terminated on day 16 (peak of clinical signs of arthritis); and one cohort was terminated on day 39 (resolution phase, with clinical signs generally decreasing) after adjuvant injection. Each cohort contained 27 adjuvant-injected (9 each of C, PF, PAE) and 15–18 saline-injected (5–6 each of C, PF, PAE) animals, for a total of 129 animals in the study.

Clinical evaluation of AA

Animals were weighed prior to CFA injection, and general health status was checked daily for the first three days after injection, in accordance with the animal ethics protocol. Animals were then weighed and checked for clinical signs of polyarthritis (hereafter called arthritis) on day 7 and day 10 post-injection and every other day thereafter until day 38. In addition, animals were monitored for pain or any signs of discomfort or infection, as well as for alertness, activity, coat quality, and color or paleness of ears. The injection site at the base of the tail was observed for redness, swelling or ulceration, and the tail was treated appropriately if necessary. Water bottles with long sipper tubes and soft bedding were used from day 7 post-injection onward to improve the animals' environment and minimize the discomfort caused by swelling of the paws. To monitor arthritis progression, animals were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane, and each paw was scored on a scale of 0 to 4, where 0 = no signs of arthritis; 1= single focus of redness or swelling; 2 = two or more foci; 3 = confluent but not global swelling; 4 = severe global swelling. The highest obtainable clinical score was 16. Scoring was blinded as to prenatal treatment and injection status and performed by the same researchers each time.

Termination

On each termination day (days 7, 16 and 39 post-injection), animals from the appropriate cohort were singly and quietly removed from the colony room, exposed to CO2 for approximately 30 seconds, and then quickly decapitated. All animal handling procedures were conducted between 0830 and 1130 hr, during the trough of the CORT circadian rhythm. Trunk blood was collected in ice cold polystyrene tubes containing 7.5 mg EDTA and 1000 KIU aprotinin. Blood was centrifuged at 3600 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Plasma was collected and stored in polypropylene tubes at −70° C until assayed for ACTH and CORT. Draining inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes were removed aseptically into tubes with sterile RPMI media supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum and then weighed. Spleen, thymus and adrenal glands also were removed, cleaned and weighed.

Proliferation Assays

Proliferation assays were used to examine the responses of lymphocytes to a polyclonal stimulant, Con A (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO). Although not antigen-specific, this measure was meant to replicate and confirm data from previous studies indicating a general decrease in lymphocyte proliferative responses to mitogens (Weinberg and Jerrells, 1991). Single cell suspensions from draining lymph nodes were prepared by passing the tissues through a 250 μm stainless steel mesh and again through a 70 μm cell strainer to exclude clumps. Lymphocytes were cultured in T cell culture media (RPMI containing 10% FBS, HEPES 10 mmol/L, L-glutamine 2 mmol/L, minimal essential medium nonessential amino acids 2 mmol/L, sodium pyruvate 1 mmol/L, 2-mercaptoethanol 50 μmol/L, penicillin 100 U/mL, and streptomycin 100 μg/mL) at 2 × 105 cells/well in 96-well plates at 37°C in 5% CO2. Proliferation was assessed in 6–8 replicates (6–8 wells for each sample). Con A was added to each well at a final concentration of 2 μg/mL. Cultures were incubated for 72–96 hr, with 1 μCi 3H-thymidine added to each well for the last 18 hr of incubation. Cells were harvested and 3H-thymidine uptake was assessed using a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter™). Data are reported as the mean +/− SEM counts per minute (CPM) from quadruplicates.

Phenotyping of Lymphocytes by Flow Cytometry

Lymphocytes from draining lymph nodes were washed with flow cytometry washing buffer (PBS supplemented with 2% FBS). Viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion and cell counts were performed using a hemacytometer. Cells were then resuspended at 1 × 108/mL in a FACS washing buffer (PBS with 2% FBS and 2mM EDTA) and stained using antibodies against the following markers: CD4 (OX35), CD8a (OX8), CD25 (OX39), CD44H (Pgp-1, H-CAM, OX49), CD62L (LECAM-1), CD45RC (OX22) and CD134 (OX40), purchased from BD PharMingen (La Jolla, CA). Typically 10,000 to 20,000 events were collected using a FACSCaliber™ flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), and the data analyzed using Flowjo (Version 5.7.2) software.

Hormone Radioimmunoassays

Plasma levels of ACTH were assayed using a modification of the DiaSorin ACTH 125I Radioimmunoassay Kit (DiaSorin Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA). Antiserum cross-reactivity was 100% for ACTH and less than 0.1% for all other peptides (including α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH), β-endorphin and β-lipotropin). Plasma volume was halved from 100 μl to 50 μl, and all reagent volumes were also halved per tube. The minimum detectable concentration for ACTH was 20 pg/ml, and the mid-range intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 3.9% and 6.5%, respectively.

Total (bound plus free) plasma CORT levels were measured by standard radioimmunoassay. Antiserum was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Orangeberg, NY, USA). The minimum detectable CORT concentration was 25 ng/mL. The intra and interassay coefficients of variation were 4.4% and 7.1%, respectively.

Statistical analyses

Incidence and Severity of Disease

Incidence

Data were analyzed with HLM 6.0 statistical software, using a mixed-effects model. The first level factor (individual growth curves) entered into the analysis was the within-subjects factor (incidence over time). The incidence of arthritis was collected as a binary variable and was analyzed using a logistic regression. The second level factor entered into the analysis was group membership (C, PF, PAE). This resulted in two separate models that enabled analysis of group differences in incidence over time. The first model analyzed the incidence from day 1 to day 16 (from induction to the time of peak incidence) (n = 54, including 9 each of C, PF, and PAE animals terminated on day 7, and 9 each of C, PF and PAE animals terminated on day 16). The second model analyzed the incidence from day 17 to day 39 (from the peak through the resolution phase), (n = 27, including 9 each of C, PF and PAE animals terminated on day 39).

Severity

Data for severity, as measured by clinical scores on each measurement day, were entered into the Graphpad 3.0 software package to determine area under the curve (AUC) for each individual. AUC was chosen because it represents the overall degree of severity over time, with higher AUC representing higher severity. Data were then entered into 3 separate Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests using SPSS 14.0 with group (C, PF, PAE) as the between-subjects factor and AUC as the dependent variable. The analyses measured AUC from day 0 to day 16, (n = 54), AUC from day 17 to day 39 (n = 27), and AUC across all 39 days (n = 27) (the latter two analyses included only the day 39 cohort). Clinical scores for saline-injected animals were 0 at all times and therefore not included in the analysis. Incidence and severity for saline-injected animals was also 0, and these data were not analyzed further.

Hormone, proliferation, and phenotype data

Hormone, proliferation and phenotype data were analyzed by separate ANOVAs for each injection day. For day 7, ANOVAs for the factors of prenatal group (C, PF, PAE) and injection (saline, adjuvant) were performed. Clinical signs of disease first appeared in some animals approximately 9–11 days following adjuvant injection, and not all animals developed clinical signs of disease. Thus, for the day 16 and day 39 cohorts, adjuvant-injected animals were further divided into subgroups: those who developed clinical signs of arthritis (Adj/AA) and those with no clinical signs of arthritis (Adj/NA). Two-way ANOVAs for the factors of group (C, PF, PAE) and condition (saline, Adj/NA, Adj/AA) were conducted, followed by Fisher LSD pair-wise comparisons for significant main and interactions effects.

Body and Organ weights

Percentage change from starting body weights (body weights on day 0, prior to CFA injection) were calculated for each animal and an overall 3-way ANOVA for the factors of prenatal group (C, PF, PAE), condition (saline, adjuvant), and day, with day treated as a repeated measure, was run. Weights of lymph node, spleen, thymus and adrenal gland were analyzed by separate ANOVAs on days 7, 16 and 39.

Results

Body weights

The overall ANOVA on percentage change from starting body weights revealed main effects of condition, [F(1,111)=17.05, p<0.001], and day, [F(2, 111)=104.73, p<0.001]. Although all animals gained weight over the course of testing, adjuvant-injected females gained less weight than saline-injected females, p<0.001, regardless of whether or not they developed clinical signs of arthritis. By day 38, saline-injected animals were 127% above starting body weight, whereas animals in the Adj/NA and Adj/AA conditions were 114% and 116% above starting body weights, respectively. There were no prenatal group × condition interactions, and no post-hoc differences between animals in the Adj/NA and the Adj/AA conditions.

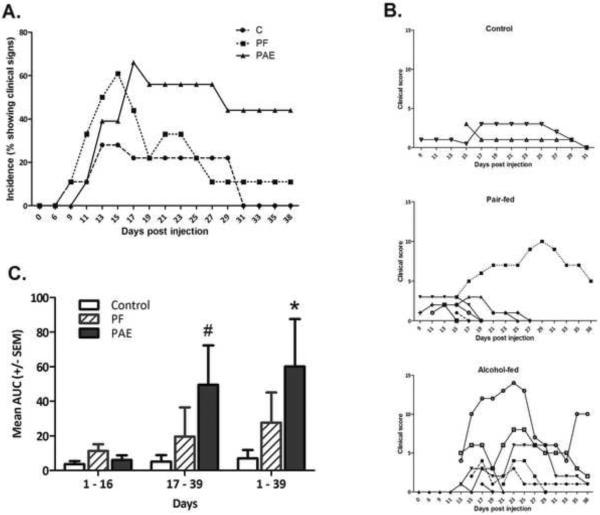

Clinical incidence and severity of AA

The onset of clinical signs of arthritis generally occurred approximately 9–11 days after adjuvant injection, although one PAE and one PF animals showed initial signs of arthritis as late as day 21 after injection. Figure 1A illustrates the onset and overall incidence of arthritis over time. PF females had a marginally faster onset than PAE females (day 9 vs day 11, p=0.077), and a significantly higher incidence of arthritis than C females [t (51) = 2.07, p = 0.04] during the induction period (days 0–16). PAE females were not different from C females in overall incidence of arthritis during the induction period. In contrast, during the resolution phase (days 17–39), PAE females had a significantly higher incidence of arthritis than both PF [t (24) = 2.13, p = 0.043] and C [t (24) = 2.37, p = 0.026] females, as well as a more prolonged course of inflammation; i.e., on day 39, there were still 4 PAE animals (57%) with clinical signs of arthritis, but only 1 PF and no C animals. C females had the lowest incidence of arthritis, with only 2 of 9 females in that cohort showing any clinical signs of disease, and showed the fastest resolution of disease, with complete resolution by day 30 post-injection.

Figure 1. Incidence and severity of arthritis.

1A. Percentage of adjuvant-injected females from prenatal Control (C, ad libitum-fed), Pair-fed (PF), and Alcohol-fed (PAE, prenatal alcohol exposure) groups that developed clinical signs of arthritis over the 39 day time course. Day 0–16, PF>C, p=0.04; PF > E, p<0.077). Day 17–39, PAE>PF=C, p<0.05.

1B. Clinical scores of individual females from prenatal Control (C, ad libitum-fed), Pair-fed (PF), and Alcohol-fed (PAE, prenatal alcohol exposure) groups in the day 39 cohort over time.

1C. Area under curve (AUC) (mean±SEM) as a quantitative measure of incidence of arthritis in females from prenatal Control (C, ad libitum-fed), Pair-fed (PF), and Alcohol-fed (PAE, prenatal alcohol exposure) groups over the 39 day time course. *PAE>PF=C, p<0.05; #PAE>PF=C, p<0.06.

Severity of arthritis in individual animals from the day 39 cohort is shown in Figure 1B. Animals in the C group had a mild clinical course of arthritis and a relatively fast resolution of disease. Although more PF than C animals showed clinical signs of disease, all but one of the PF females had relatively mild arthritis with a fast recovery, similar to the course seen in C females. In contrast, most of the PAE females developed moderate to severe arthritis, and the course of disease was prolonged. The Kruskal-Wallis analysis of overall AUC (days 1–39), revealed a significant effect of prenatal group (p <0.05), with PAE females having the highest AUC, and thus the greatest severity of disease (Figure 1C). Further analysis indicated that the effect of prenatal treatment was not significant during the induction phase (day 0–16) but emerged during the resolution phase (day 17–39) (p<0.06).

Lymphoid organ weights and lymph node cell counts

Organ weights

Analysis for day 7 post-injected revealed that overall, adjuvant-injected animals had increased lymph node [F(1,36)=42.4, p<0.001] and spleen [F(1,36)=48.0, p<0.001] weights and decreased thymus [F(1,36)=23.8, p<0.001] weights compared to saline-injected animals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Organ weights (g; Mean ± SEM) by Treatment

| Day 7 | Day 16 | Day 39 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | Adj | Saline | Adj/NA | Adj/AA | Saline | Adj/NA | Adj/AA | |

| Lymph node | 0.069±0.023 | 0.257a±0.017 | 0.073±0.029 | 0.221±0.032 | 0.316c±0.031 | 0.067±0.009 | 0.184e±0.016 | 0.163e±0.011 |

| Spleen | 0.560±0.030 | 0.819a±0.022 | 0.620±0.047 | 0.847±0.053 | 01.283c±0.051 | 0.572±0.034 | 0.807e±0.062 | 0.818e±0.043 |

| Thymus | 0.468±0.026 | 0.313b±0.019 | 0.345±0.026 | 0.255d±0.029 | 0.226d±0.028 | 0.339±0.019 | 0.358±0.035 | 0.332±0.024 |

| Adrenal | 0.032±0.002 | 0.030±0.001 | 0.037±0.002 | 0.039±0.002 | 0.043f±0.002 | 0.039±0.002 | 0.044±0.003 | 0.039±0.002 |

Saline: saline-injected; Adj: Adjuvant-injected; Adj/NA: adjuvant-injected with no clinical signs of arthritis; Adj/AA: adjuvant injected with clinical signs of arthritis

Adj > saline, p<0.001

Adj < saline, p<0.001

Adj/AA > Adj/NA > saline, p<0.05

Adj/AA = Adj/NA < saline, p<0.001 and p<0.05, respectively

Adj/AA = Adj/NA > saine, p<0.01

Adj/AA > saline, p<0.05

On day 16, at the peak of inflammation, both lymph node [F(2,33)=17.0, p<0.001] and spleen [F(2,33)=46.8, p<0.001], weights were highest in animals that developed arthritis and higher in Adj/NA than in saline-injected animals (Adj/AA>Adj/NA>Sal, p<0.05). Consistent with day 7, thymus weights [F(2,33)=5.5, p<0.01] of animals in the Adj/AA and Adj/NA conditions were lower than those of animals in the saline condition (Adj/AA=Adj/NA<Sal, p<0.01 and p<0.05, respectively) (Table 1).

On day 39, during the resolution phase, adjuvant-injected animals, regardless of whether they developed clinical signs of arthritis, had higher lymph node [F(2,36)=35.6, p<0.001] and spleen [F(2,36=12.2, p<0.001] weights than saline-injected animals (Adj/AA=Adj/NA>Sal, p<0.01), whereas thymus weights no longer differed among conditions. In addition, in the Adj/NA condition [F(2,36)=2.93, p<0.05], PAE females (0.240±0.026 g) had larger lymph nodes than C females (0.143±0.014 g) (p<0.01) (Table 1).

Lymph node cell counts

There were significant main effects of condition (adjuvant vs saline) on all test days (day 7 [(F(1,36)=32.3, p<0.001)]; day 16 [F(2,33)=27.3, p<0.001)]; day 39 [F(2,36=39.3, p<0.001]) (Table 2), but no significant effects of prenatal treatment on counts of viable cells. As expected, adjuvant injection greatly increased cell numbers (up to 10 fold) compared to saline injection (p<0.001) (Table 2). In addition, Adj/AA animals had higher cell counts than Adj/NA animals on day 16 (p<0.05), at the peak of inflammation, but were no longer different by day 39, during the resolution phase (Adj/AA=Adj/NA >Sal, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Lymph node cell counts (viable cells × 108)

| Day 7 | Day 16 | Day 39 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | Adj | Saline | Adj/NA | Adj/AA | Saline | Adj/NA | Adj/AA |

| 0.282±0.198 | 1.681a±0.147 | 0.266±0.118 | 1.258±0.127 | 1.741b±0.123 | 0.175±0.055 | 0.855c±0.099 | 0.873c±0.068 |

Saline: saline-injected; Adj: Adjuvant-injected; Adj/NA: adjuvant-injected with no clinical signs of arthritis; Adj/AA: adjuvant injected with clinical signs of arthritis

Adj > saline, p<0.001

Adj/AA > Adj/NA > saline, p<0.01 and p<0.001, respectively

Adj/AA = Adj/NA > saline, p<0.001

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from draining lymph nodes

Adjuvant injection had marked effects on percentages of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Table 3). On days 7 [F(1,36)=44.6, p<0.001] and 16 [F(2,33)=3.4, p<0.05], the percentage of CD4+ T cells was lower in adjuvant-injected than in saline-injected animals. In addition, the percent of CD4+ T cells was lower in saline-injected PAE (42.7±1.9) and PF (45.0±1.9) than C (51.4±1.9) animals on day 16 [F(4,33)=3.9, p<0.01] (PAE=PF<C, p<0.01 and p<0.05, respectively). By day 39, differences among groups and conditions were no longer significant. For CD8+ T cells, main effects of condition [F(1,111)=7.59, p<0.01] and day [(F(2,111)=7.60, p<0.001] indicated that the percentage of CD8+ T cells in adjuvant-injected animals was marginally higher on day 7 (p<0.055) and significantly higher on day 39 (p<0.01) than that in saline-injected animals (Table 3).

Table 3.

% CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Mean ± SEM)

| Day 7 | Day 16 | Day 39 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | Adj | Saline | Adj/NA | Adj/AA | Saline | Adj/NA | Adj/AA | |

| CD4+ | 50.62±1.91 | 34.72a±1.42 | 46.35±1.12 | 43.16b±1.25 | 42.32b±1.21 | 49.86±0.99 | 47.57±1.79 | 46.66±1.22 |

| CD8+ | 18.21±0.85 | 20.30c±0.63 | 21.33±0.67 | 20.48±0.75 | 21.19±0.73 | 20.41±0.71 | 25.94d±1.28 | 22.53d±0.88 |

Saline: saline-injected; Adj: Adjuvant-injected; Adj/NA: adjuvant-injected with no clinical signs of arthritis; Adj/AA: adjuvant injected with clinical signs of arthritis

Adj < saline, p<0.001

Adj/AA = Adj/NA < saline, p<0.05 and p=0.066, respectively

Adj > saline, p=0.055

Adj/AA=Adj/NA>saline, p<0.01

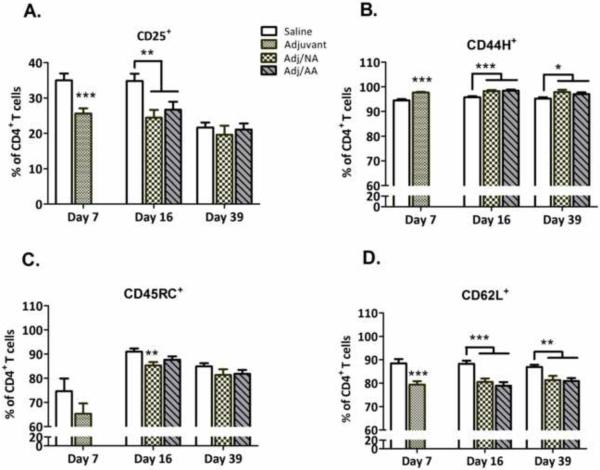

Activation status of CD4+ T lymphocytes

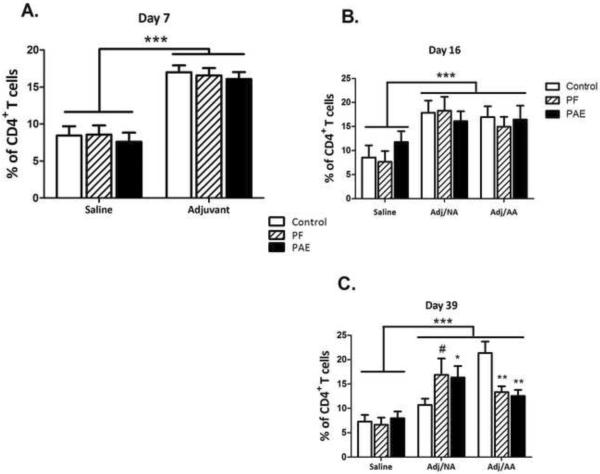

Generally, adjuvant injection increased the percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing CD44H and CD134 activation surface markers, and decreased the percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing CD25, CD62L, and CD45RC activation markers, with most of the changes persisting throughout the course of inflammation and resolution (Figures 2 and 3). For most of these markers, adjuvant-induced changes in expression occurred regardless of whether the animals developed clinical signs of disease. Interestingly, a prenatal group × condition interaction, [F(4,35)=4.45, p<0.01], indicated that the percentage of CD4+CD134+ T cells was lower in PAE and PF than C animals that developed arthritis (Adj/AA condition, PAE=PF<C, p<0.01), but higher in PAE and PF than C animals that did not develop arthritis (Adj/NA condition, PAE=PF>C, p<0.05 and p=0.10) (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Activation status (mean±SEM) of lymph node CD4+ T cells.

Percentage of activated CD4+ T cells expressing the activation markers CD25, CD44H, CD45RC, and CD62L in saline- and adjuvant-injected females, as assessed by flow cytometry. *p<0.05**p<0.01, ***p<0.001, compared to Saline-injected females.

Figure 3. Lymph node CD4+CD134+ T cells.

Percentage (mean±SEM) of activated CD4+ T cells expressing the activation marker CD134+ in saline- and adjuvant-injected females from prenatal Control (C, ad libitum-fed), Pair-fed (PF), and alcohol-fed (PAE, prenatal alcohol exposure) groups, as assessed by flow cytometry. ***p<0.001 vs saline-injected females; #p<0.10 vs C females.

Lymphocyte proliferation

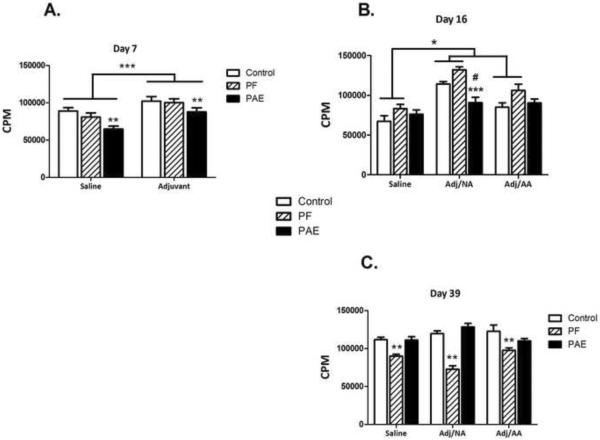

For day 7, significant main effects of prenatal group [F(2,330)=9.75, p<0.001] and condition [F(1,330)=25.3, p<0.001] indicated that lymph node-derived lymphocytes from PAE animals, regardless of injection condition, had a lower proliferative response to Con A than lymphocytes from PF and C animals (p<0.01), and overall, lymphocyte proliferation was greater in adjuvant- than in saline-injected animals, p<0.001 (Figure 4A). At the peak of inflammation (day 16), there were main effects of group [F(2,325)=10.31, p<0.001] and condition [F(2,325)=23.13, p<0.001, and a group × condition interaction [F(4,325)=2.87, p<0.05)]. The proliferative response of lymphocytes from PAE females in the Adj/NA condition was lower than that of their PF and C counterparts (p<0.001 and p<0.06, respectively) (Figure 4B), and was similar across injection conditions, whereas PF and C females in the Adj/NA condition had a greater proliferative response than their PF and C counterparts in the saline and Adj/AA conditions. For day 39, by contrast, the group × condition interaction [F(4,340)=3.68, p<0.01] revealed an effect of pair-feeding; collapsed across injection condition, lymphocytes from PF animals showed a lower proliferative response than those from PAE and C animals (p<0.01) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Proliferative response (mean±SEM) of lymphocytes from draining lymph nodes on d 7, 16 and 39 post-adjuvant injection.

3H-thymidine incorporation expressed as counts per minute (CPM).

4A. Day 7: Adjuvant>saline, ***p<0.001; Collapsed across condition, PAE<PF=C, **p<0.01.

4B. Day 16: In the Adj/NA condition, PAE<PF=C, ***p<0.001 and #p<0.06, respectively.

4C. Day 39: Collapsed across condition, PF<PAE=C, **p<0.01.

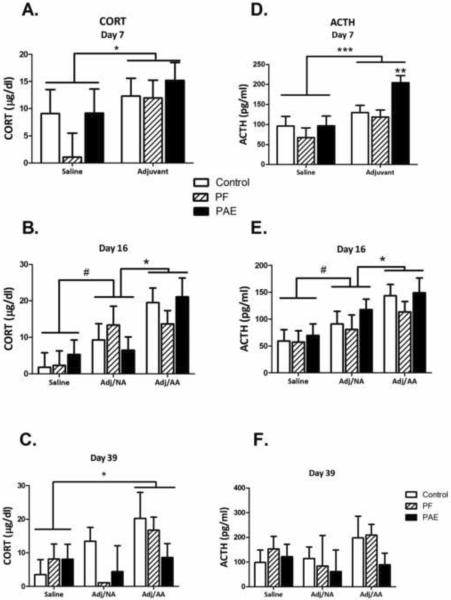

Adrenal weights and basal levels of plasma CORT and ACTH

Adrenal weights

There were no significant effects of prenatal group or condition on Day 7 or Day 39 (Table 1). However, on day 16, at the peak of inflammation, a significant effect of group [F(2,33)=6.22, p<0.01] and a trend for condition [F(2,33)=2.78, p=0.077] indicated that adrenal weights were lower in PAE (0.036±0.002 g) and PF (0.039±0.002 g) than in C (0.044±0.002 g) females, (p<0.01 and p<0.05, respectively), and were higher overall in Adj/AA than in saline-injected animals (p<0.05).

Plasma CORT and ACTH

CORT

Analyses revealed significant main effects of condition for day 7 [F(1,36=4.43, p<0.05] and day 16 [F(2,33)=9.75, p<0.001], and a trend for condition on day 39 [F(2,36=2.47, p=0.099] (Figure 5). Basal CORT levels were higher in adjuvant- than in saline-injected animals on day 7 (p<0.05) (Figure 5A); different among the 3 conditions on day 16 (Adj/AA>Adj/NA>saline, p<0.05 and p=0.065, respectively) (Figure 5B); and higher in the Adj/AA than in the saline condition on day 39 (Adj/AA>saline, p<0.05) (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. HPA hormone profiles.

Left column: Plasma CORT levels (mean±SEM) on d 7 (A), 16 (B) and 39 (C) after injection.

Day 7: Adj>saline, *p<0.05; Day 16: Adj/AA>Adj/NA>saline, #p=0.065; *p<0.05); Day 39: Adj/AA>saline, *p<0.05.

Right column: Plasma ACTH levels (mean±SEM) on d 7 (D), 16 (E) and 39 (F) after injection.

Day 7: Adj>saline, ***p<0.001; within Adj, PAE>PF=C, **p<0.01; Day 16: Adj/AA>Adj/NA>saline, *p<0.05, #p=0.068.

ACTH

The pattern of response for basal ACTH levels was generally similar to that of plasma CORT (Figure 5). One notable difference was on day 7: Significant main effects of condition [F(1,36=13.81, p=0.001] and group [F(2,36=3.87, p<0.05] indicated that in addition to the overall effect of adjuvant injection on basal ACTH levels (Adj>Sal, p<001), PAE females had significantly higher ACTH levels than PF and C females following adjuvant injection (p<0.01) (Figure 5D). By day 16, there were no longer effects of prenatal treatment. ACTH levels were higher in Adj/AA than in Adj/NA animals (p<0.05), and marginally higher in Adj/NA than in saline-injected animals (p=0.068) (main effect of condition [F(2,33)=8.36, p<0.001]) (Figure 5E). By day 39, during resolution, there were no effects of prenatal treatment or condition on ACTH levels (Figure 5F).

Discussion

The present data demonstrate, for the first time, an adverse effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on the course and severity of adjuvant-induced arthritis in adulthood, indicating an important and clinically relevant long-term alteration in functional immune status. Although PAE females showed a delay in arthritis onset during the induction phase, during the resolution phase, PAE females had a more prolonged course of disease and greater severity of inflammation compared to females in the PF and C groups. In addition, PAE females exhibited a blunted lymphocyte proliferative response to Con A and a greater increase in basal ACTH levels during the induction phase compared to controls. These data suggest that prenatal alcohol exposure may have both direct and indirect effects on chronic inflammatory processes, altering both immune and neuroendocrine function, and likely, the interaction between these systems.

In support of the suggestion that AA can be considered a model of persistent or chronic pain/stress (Bomholt et al., 2004), we found that overall, across prenatal treatments, adjuvant-injected animals gained less weight, and exhibited decreased thymus weights, increased adrenal weights, and increased basal levels of CORT and ACTH. The greatest changes were found during disease onset and at the peak of inflammation, with minimal differences occurring during the resolution phase. Moreover, consistent with previous reports (Harbuz et al., 1993), adjuvant administration in general was a potent challenge to both the immune and endocrine systems. Adjuvant-induced activation of the immune system was observed on day 7, prior to any clinical signs of disease, and increased as inflammation increased, as indicated by enlarged draining lymph nodes and spleens, increased lymph node lymphocyte cell counts, increased lymphocyte proliferative responses to Con A, and activated immune cell phenotypes. In addition, decreased CD4+ and increased CD8+ T cells from draining lymph nodes, and consequently, a decreased CD4+:CD8+ ratio, were observed, consistent with the expected pro-inflammatory response to adjuvant. Prenatal exposure to alcohol did not differentially alter any of these outcome measures, with the exception that PAE females in the Adj/NA condition had larger lymph nodes than C females on day 39. It is possible that adjuvant-induced activation of the immune system may have persisted longer in PAE than control animals, even in the absence of clinical signs of disease.

Altered percentages of CD4+ T cells expressing a variety of activation markers over the course of inflammation were observed. Changes were consistent in general with the roles these molecules play in cell processes related to activation, adhesion, cell trafficking, lymph node homing, and inflammation, but were not specific to the increased inflammation occurring in PAE animals. However, the finding of a decreased percent of lymph node CD4+CD134+ cells in adjuvant-injected PAE and PF females that developed clinical signs of arthritis, but an increased percentage of CD4+CD134+ cells in PAE and PF animals that remained asymptomatic is intriguing. CD134 (OX40) and OX40 ligand (OX40L) are cell surface molecules belonging to the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily. CD134 is expressed in vivo primarily on autoreactive CD4+ T cells, and is selectively upregulated in inflamed tissue. Patients with active RA, for example, showed higher CD4+CD134+ expression on T lymphocytes in synovial fluid and synovial tissue (Giacomelli et al., 2001), and T cells isolated from the site of inflammation in an animal model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) showed increased expression of OX40 (Weinberg, 2002).. Conversely, administration of an anti-OX40L monoclonal antibody ameliorated disease severity in a collagen-induced arthritis model (Yoshioka et al., 2000), and injection of liposomes coated with a CD134-directed monoclonal antibody into the hind paws of rats ameliorated the symptoms of adjuvant-induced arthritis (Boot et al., 2005). In our study, we found the opposite of what we expected, i.e., decreased rather than increased CD134 expression in PAE females that developed clinical signs of arthritis. Moreover, PF females showed increases or decreases in the percentage of CD4+CD134+ T cells similar to those of PAE females, but had a milder course and faster resolution of disease. It is possible that our findings relate to the compartment sampled. That is, decreased CD134 expression on lymph node T cells may reflect migration of CD4+CD134+ T cells from lymph nodes to joints (“…a redeployment from the `barracks' to the `battle stations'”) (McEwen et al., 1997), resulting in increased CD134 expression in the synovial fluid/joints of animals with clinical signs of arthritis. It has been shown that with inflammation, the synovium becomes a target for recruitment of lymphocytes, particularly those generated in peripheral lymphoid tissue (Issekutz and Issekutz, 1991; Spargo et al., 1996). However, this would not explain why PF females were similar to PAE females in their CD134 profile yet had a different course of disease. The relationship between basal CORT levels and expression of CD134, particularly during the resolution phase, also requires further investigation. On day 39, it is noteworthy that for PF and C animals in the Adj/NA condition, mean CORT levels were somewhat lower than those in controls, and the percentage of CD4+CD134+ T cells was increased. A relationship between CORT and CD134, however, does not hold up to the same extent in animals that develop clinical signs of arthritis. Further studies are clearly needed to determine what role, if any, CD134+ T cells play in the differential course of disease that was observed in PAE and control females.

The findings that PF and PAE females showed similar responses on some measures, and that pair-feeding itself had some effects on immune function, are not entirely surprising. Although pair-feeding is a necessary control for the reduced food intake that occurs in alcohol-consuming females, pair-feeding itself is a treatment. PF dams receive an amount of diet matched to that consumed by PAE dams (g/kg body wt/day of gestation). While both groups receive the same number of calories, PAE dams eat ad libitum whereas PF dams receive a reduced ration, less than they would consume if fed the same diet without alcohol. As a result, PF dams typically consume their entire daily ration within a few hours, and are effectively on a “meal-feeding” schedule. Restricted meal-feeding is such a significant manipulation that it can override the influence of the light-dark cycle and serve as the “Zeitgeber” to synchronize circadian rhythms of a variety of variables, as well as having adverse effects on a number of cellular processes (Krieger, 1974; Krieger and Hauser, 1978; Gallo and Weinberg, 1981). Moreover, nutrient restriction and maternal undernutrition can themselves program the offspring HPA axis, resulting in fetal over-exposure to glucocorticoids and HPA hyperactivity in adulthood. Such changes, in turn, could play a role in increased susceptibility to immune and inflammatory diseases (Lesage et al., 2001; Lesage et al., 2006; Vieau et al., 2007). The mechanisms underlying the effects of pair-feeding remain to be determined. However, it is possible that similar phenotypes in PAE and PF offspring may be differentially mediated (direct/indirect effects of alcohol vs. effects of food/nutrient restriction and/or mild prenatal stress due to the hunger that accompanies food restriction) rather than occurring along a continuum of effects on the same pathway.

The increased adjuvant-induced HPA activation seen during the induction phase, was specific to PAE females and could have played a role in the delayed onset of disease, either directly, by suppressing the inflammatory response, or indirectly, by suppressing the lymphocyte proliferative response to adjuvant. Consistent with this latter possibility, we found reduced lymph node lymphocyte proliferative responses to Con A in PAE animals overall on day 7, and in PAE animals in the Adj/NA condition on day 16. These data replicate and extend previous results from our laboratory (Weinberg and Jerrells, 1991) and others (Ewald and Frost, 1987; Norman et al., 1989) demonstrating reduced splenic and thymic lymphocyte proliferative responses to mitogens, as well as reduced thymic and splenic T-cell responses to a secondary stimulation by IL-2. Blunted proliferation at induction of arthritis could reduce cytokine production and recruitment of cells to the joints, thus delaying arthritis onset. However, these data must be interpreted with caution. While Con A-stimulated proliferation was utilized to replicate previous findings in order to confirm known prenatal alcohol effects in this new model, this assay did not test antigen-specific proliferation and is a relatively low resolution method of quantifying T cell proliferation. Of note, consistent with previous studies (Straub and Besedovsky, 2003; Del Rey et al., 2010), the differential elevation in basal HPA activity occurred during induction and was not sustained over the course of testing. While we saw graded CORT and ACTH responses on day 16, at the peak of inflammation (saline < Adj/NA < Adj/AA), neither ACTH nor CORT levels differed among prenatal treatment groups on day 16 or 39, and by day 39, both ACTH and CORT levels appeared, if anything, somewhat lower in PAE than C animals with clinical signs of arthritis. Del Rey et al (2010) suggest that low levels of CORT in the context of high levels of inflammation is suggestive of a disconnect between the immune and endocrine systems. Recent data from our laboratory support this suggestion (Zhang et al., 2005). Following exposure to repeated restraint stress, PAE animals displayed significantly increased and sustained elevations in plasma levels of IL-1β and TNF-α to LPS injection compared to controls, but did not differ from controls in their CORT response to LPS, suggesting disruption of the cytokine-HPA axis feedback circuit. In the present study it is possible that reduced HPA activity in PAE animals during the resolution phase, in the face of persisting inflammation, is related to the prolonged course and severity of disease seen in PAE compared to control animals.

One conceptual framework for understanding the long-term adverse effects of alcohol on susceptibility to arthritis is that of fetal programming. Environmental factors acting during sensitive periods of development are known to exert organizational effects on physiological/neurobiological systems, resulting in changes that can persist throughout life and influence the risk for diseases or disorders in adulthood (Welberg and Seckl, 2001; Owen et al., 2005) including the risk for RA (Del Rey et al., 2010; Colebatch and Edwards, 2011). Fetal programming is generally thought to facilitate the organism's adaptation to the postnatal environment. However, programming can be detrimental if stimuli program systems to function outside their normal physiological range, leading to high allostatic load (McEwen, 1998) Data suggest that the HPA axis is particularly vulnerable to programming by early life events (Welberg and Seckl, 2001; Owen et al., 2005). In this regard, because HPA dysregulation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of RA, it has been suggested that HPA programming may be one potential mechanism through which early life factors can predispose the individual to autoimmune diseases (Walker et al., 1999; Wahle et al., 2002; Jessop et al., 2004; Colebatch and Edwards, 2011). As noted, alcohol exposure in utero programs the fetal HPA axis such that HPA tone is increased throughout life, resulting in increased HPA activation, delayed or deficient recovery (Taylor et al., 1988; Weinberg et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2000), and altered central HPA regulation (Zhang et al., 2005; Glavas et al., 2007; Weinberg et al., 2008). We postulate that imposition of the chronic inflammatory stress of adjuvant-induced arthritis on a system already sensitized by prenatal exposure to alcohol could underlie the increased autoimmune responses and the altered course and severity of disease that we observed in our model. Alcohol-induced disruptions of normal neuroendocrine-immune interactions may provide an indirect route through which early life experiences can have long term effects on the immune system.

In summary, we report the novel finding that prenatal exposure to alcohol alters the course and severity of adjuvant-induced arthritis in adulthood. Alcohol exposure appears to have both direct and indirect effects on the inflammatory response of the offspring, altering both immune and neuroendocrine function, and likely, the interaction between these two systems. Ongoing studies investigating HPA hormones and cytokines in multiple compartments, and immunohistochemical analysis of arthritic joints in this model will begin to elucidate mechanisms mediating alcohol's long-term adverse effects on neurobiological/neuroimmune processes and will have important implications for understanding vulnerabilities in children with FASD.

Research Highlight.

These novel data indicate that prenatal alcohol exposure significantly increases the course and severity of inflammation in a rat model of adjuvant-induced arthritis.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by R24MH081797 to JW and GGM; R37AA007789 and a grant from the BC Ministry of Children and Family Services through the Human Early Learning Partnership to JW; K05AA017149 and R01AA07293 to GGM. The authors are grateful to Tamara Bodnar and Dr. Wendy Comeau for assistance with the graphs and statistics and for helpful input on the content of this manuscript. We thank Deborah Sasges and Jonathan Malo for their assistance in running this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Banik RK, Kasai M, Mizumura K. Reexamination of the difference in susceptibility to adjuvant-induced arthritis among LEW/Crj, Slc/Wistar/ST and Slc/SD rats. Exp Anim. 2002;51:197–201. doi: 10.1538/expanim.51.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger DL, Lubahn C, Lorton D. Maternal and early life stress effects on immune function: relevance to immunotoxicology. J Immunotoxicol. 2008;5:419–444. doi: 10.1080/15476910802483415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomholt SF, Harbuz MS, Blackburn-Munro G, Blackburn-Munro RE. Involvement and role of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) stress axis in animal models of chronic pain and inflammation. Stress. 2004;7:1–14. doi: 10.1080/10253890310001650268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot EP, Koning GA, Storm G, Wagenaar-Hilbers JP, van Eden W, Everse LA, Wauben MH. CD134 as target for specific drug delivery to auto-aggressive CD4+ T cells in adjuvant arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R604–615. doi: 10.1186/ar1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Hanson MD, Paterson LQ, Griffin MJ, Walker HA, Miller GE. Socioeconomic status and inflammatory processes in childhood asthma: the role of psychological stress. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1014–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chover-Gonzalez AJ, Jessop DS, Tejedor-Real P, Gibert-Rahola J, Harbuz MS. Onset and severity of inflammation in rats exposed to the learned helplessness paradigm. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:764–771. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.7.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chover-Gonzalez AJ, Harbuz MS, Tejedor-Real P, Gibert-Rahola J, Larsen PJ, Jessop DS. Effects of stress on susceptibility and severity of inflammation in adjuvant-induced arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;876:276–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church MW, Gerkin KP. Hearing disorders in children with fetal alcohol syndrome: findings from case reports. Pediatrics. 1988;82:147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausing P, Ali SF, Taylor LD, Newport GD, Rybak S, Paule MG. Central and peripheral neurochemical alterations and immune effects of prenatal ethanol exposure in rats. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1996;14:461–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colebatch AN, Edwards CJ. The influence of early life factors on the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;163:11–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussons-Read ME, Okun ML, Nettles CD. Psychosocial stress increases inflammatory markers and alters cytokine production across pregnancy. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, Taylor A, Poulton R. Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1319–1324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610362104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rey A, Wolff C, Wildmann J, Randolf A, Straub RH, Besedovsky HO. When immune-neuro-endocrine interactions are disrupted: experimentally induced arthritis as an example. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2010;17:165–168. doi: 10.1159/000258714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Fairweather D, Pearson WS, Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Croft JB. Cumulative childhood stress and autoimmune diseases in adults. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:243–250. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald SJ. T lymphocyte populations in fetal alcohol syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1989;13:485–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald SJ, Frost WW. Effect of prenatal exposure to ethanol on development of the thymus. Thymus. 1987;9:211–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald SJ, Walden SM. Flow cytometric and histological analysis of mouse thymus in fetal alcohol syndrome. J Leukoc Biol. 1988;44:434–440. doi: 10.1002/jlb.44.5.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald SJ, Huang C. Lymphocyte populations and immune responses in mice prenatally exposed to ethanol. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;325:191–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo PV, Weinberg J. Corticosterone rhythmicity in the rat: interactive effects of dietary restriction and schedule of feeding. J Nutr. 1981;111:208–218. doi: 10.1093/jn/111.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomelli R, Passacantando A, Perricone R, Parzanese I, Rascente M, Minisola G, Tonietti G. T lymphocytes in the synovial fluid of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis display CD134-OX40 surface antigen. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:317–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giberson PK, Blakley BR. Effect of postnatal ethanol exposure on expression of differentiation antigens of murine splenic lymphocytes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giberson PK, Weinberg J. Effects of prenatal ethanol exposure and stress in adulthood on lymphocyte populations in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1286–1294. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giberson PK, Kim CK, Hutchison S, Yu W, Junker A, Weinberg J. The effect of cold stress on lymphocyte proliferation in fetal ethanol-exposed rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:1440–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavas MM, Ellis L, Yu WK, Weinberg J. Effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on basal limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation: role of corticosterone. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1598–1610. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesfeld Z, Christie R, Felten DL, LeGrue SJ. Prenatal ethanol exposure alters immune capacity and noradrenergic synaptic transmission in lymphoid organs of the adult mouse. Neuroscience. 1990;35:185–194. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90133-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbuz MS, Rees RG, Lightman SL. HPA axis responses to acute stress and adrenalectomy during adjuvant-induced arthritis in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:R179–185. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.1.R179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbuz MS, Chover-Gonzalez AJ, Jessop DS. Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis and chronic immune activation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;992:99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issekutz AC, Issekutz TB. Quantitation and kinetics of polymorphonuclear leukocyte and lymphocyte accumulation in joints during adjuvant arthritis in the rat. Lab Invest. 1991;64:656–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson SW, Bihun JT, Chiodo LM. Effects of prenatal alcohol and cocaine exposure on infant cortisol levels. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:195–208. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerrells TR, Weinberg J. Influence of ethanol consumption on immune competence of adult animals exposed to ethanol in utero. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:391–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessop DS, Richards LJ, Harbuz MS. Effects of stress on inflammatory autoimmune disease: destructive or protective? Stress. 2004;7:261–266. doi: 10.1080/10253890400025497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Knight R, Marmer DJ, Steele RW. Immune deficiency in fetal alcohol syndrome. Pediatr Res. 1981;15:908–911. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallberg H, Jacobsen S, Bengtsson C, Pedersen M, Padyukov L, Garred P, Frisch M, Karlson EW, Klareskog L, Alfredsson L. Alcohol consumption is associated with decreased risk of rheumatoid arthritis: results from two Scandinavian case-control studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:222–227. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.086314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CK, Turnbull AV, Lee SY, Rivier CL. Effects of prenatal exposure to alcohol on the release of adenocorticotropic hormone, corticosterone, and proinflammatory cytokines. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger DT. Food and water restriction shifts corticosterone, temperature, activity and brain amine periodicity. Endocrinology. 1974;95:1195–1201. doi: 10.1210/endo-95-5-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger DT, Hauser H. Comparison of synchronization of circadian corticosteroid rhythms by photoperiod and food. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:1577–1581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.3.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Rivier C. Gender differences in the effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to immune signals. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:145–155. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Schmidt D, Tilders F, Rivier C. Increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of rats exposed to alcohol in utero: role of altered pituitary and hypothalamic function. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:515–528. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage J, Blondeau B, Grino M, Breant B, Dupouy JP. Maternal undernutrition during late gestation induces fetal overexposure to glucocorticoids and intrauterine growth retardation, and disturbs the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis in the newborn rat. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1692–1702. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.5.8139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage J, Sebaai N, Leonhardt M, Dutriez-Casteloot I, Breton C, Deloof S, Vieau D. Perinatal maternal undernutrition programs the offspring hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Stress. 2006;9:183–198. doi: 10.1080/10253890601056192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Solomon DH, Costenbader KH, Keenan BT, Chibnik LB, Karlson EW. Alcohol consumption and markers of inflammation in women with preclinical rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3554–3559. doi: 10.1002/art.27739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JR, Gowers IR, Moore DJ, Wilson AG. Alcohol consumption is inversely associated with risk and severity of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:2140–2146. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Biron CA, Brunson KW, Bulloch K, Chambers WH, Dhabhar FS, Goldfarb RH, Kitson RP, Miller AH, Spencer RL, Weiss JM. The role of adrenocorticoids as modulators of immune function in health and disease: neural, endocrine and immune interactions. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;23:79–133. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(96)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlot E, Couret D, Otten W. Prenatal stress, fetal imprinting and immunity. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscatello KM, Biber KL, Jennings SR, Chervenak R, Wolcott RM. Effects of in utero alcohol exposure on B cell development in neonatal spleen and bone marrow. Cell Immunol. 1999;191:124–130. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman DC, Chang MP, Castle SC, Van Zuylen JE, Taylor AN. Diminished proliferative response of con A-blast cells to interleukin 2 in adult rats exposed to ethanol in utero. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1989;13:69–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen D, Andrews MH, Matthews SG. Maternal adversity, glucocorticoids and programming of neuroendocrine function and behaviour. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:209–226. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay DS, Bendersky MI, Lewis M. Effect of prenatal alcohol and cigarette exposure on two- and six-month-old infants' adrenocortical reactivity to stress. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996;21:833–840. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.6.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redei E, Clark WR, McGivern RF. Alcohol exposure in utero results in diminished T-cell function and alterations in brain corticotropin-releasing factor and ACTH content. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1989;13:439–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redei E, Halasz I, Li LF, Prystowsky MB, Aird F. Maternal adrenalectomy alters the immune and endocrine functions of fetal alcohol-exposed male offspring. Endocrinology. 1993;133:452–460. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.2.8344191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider ML, Moore CF, Kraemer GW. Moderate level alcohol during pregnancy, prenatal stress, or both and limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis response to stress in rhesus monkeys. Child Dev. 2004;75:96–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider ML, Moore CF, Kraemer GW, Roberts AD, DeJesus OT. The impact of prenatal stress, fetal alcohol exposure, or both on development: perspectives from a primate model. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:285–298. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelig LL, Jr., Steven WM, Stewart GL. Effects of maternal ethanol consumption on the subsequent development of immunity to Trichinella spiralis in rat neonates. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:514–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seres J, Stancikova M, Svik K, Krsova D, Jurcovicova J. Effects of chronic food restriction stress and chronic psychological stress on the development of adjuvant arthritis in male long evans rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;966:315–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spargo LD, Hawkes JS, Cleland LG, Mayrhofer G. Recruitment of lymphoblasts derived from peripheral and intestinal lymph to synovium and other tissues in normal rats and rats with adjuvant arthritis. J Immunol. 1996;157:5198–5207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steven WM, Stewart GL, Seelig LL. The effects of maternal ethanol consumption on lactational transfer of immunity to Trichinella spiralis in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992;16:884–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub RH, Besedovsky HO. Integrated evolutionary, immunological, and neuroendocrine framework for the pathogenesis of chronic disabling inflammatory diseases. FASEB J. 2003;17:2176–2183. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0433hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AN, Tio DL, Chiappelli F. Thymocyte development in male fetal alcohol-exposed rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AN, Branch BJ, Van Zuylen JE, Redei E. Maternal alcohol consumption and stress responsiveness in offspring. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;245:311–317. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2064-5_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanbesien-Mailliot CC, Wolowczuk I, Mairesse J, Viltart O, Delacre M, Khalife J, Chartier-Harlin MC, Maccari S. Prenatal stress has pro-inflammatory consequences on the immune system in adult rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieau D, Sebaai N, Leonhardt M, Dutriez-Casteloot I, Molendi-Coste O, Laborie C, Breton C, Deloof S, Lesage J. HPA axis programming by maternal undernutrition in the male rat offspring. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(Suppl 1):S16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink J, Auth J, Abebe DT, Brenneman DE, Spong CY. Novel peptides prevent alcohol-induced spatial learning deficits and proinflammatory cytokine release in a mouse model of fetal alcohol syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:825–829. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahle M, Krause A, Pierer M, Hantzschel H, Baerwald CG. Immunopathogenesis of rheumatic diseases in the context of neuroendocrine interactions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;966:355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JG, Littlejohn GO, McMurray NE, Cutolo M. Stress system response and rheumatoid arthritis: a multilevel approach. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:1050–1057. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.11.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg AD. OX40: targeted immunotherapy--implications for tempering autoimmunity and enhancing vaccines. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:102–109. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J, Jerrells TR. Suppression of immune responsiveness: sex differences in prenatal ethanol effects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15:525–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J, Taylor AN, Gianoulakis C. Fetal ethanol exposure: hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and beta-endorphin responses to repeated stress. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:122–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J, Sliwowska JH, Lan N, Hellemans KG. Prenatal alcohol exposure: foetal programming, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sex differences in outcome. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:470–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welberg LA, Seckl JR. Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids and the programming of the brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:113–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yirmiya R, Chiappelli F, Tio DL, Tritt SH, Taylor AN. Effects of prenatal alcohol and pair feeding on lipopolysaccharide-induced secretion of TNF-alpha and corticosterone. Alcohol. 1998;15:327–335. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(97)00153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka T, Nakajima A, Akiba H, Ishiwata T, Asano G, Yoshino S, Yagita H, Okumura K. Contribution of OX40/OX40 ligand interaction to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2815–2823. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200010)30:10<2815::AID-IMMU2815>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Sliwowska JH, Weinberg J. Prenatal alcohol exposure and fetal programming: effects on neuroendocrine and immune function. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:376–388. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]