Abstract

Background

Seeding trials, clinical studies conducted by pharmaceutical companies for marketing purposes, have rarely been described in detail.

Methods

We examined all documents relating to the clinical trial Study of Neurontin: Titrate to Effect, Profile of Safety (STEPS) produced during the Neurontin marketing, sales practices and product liability litigation, including company internal and external correspondence, reports, and presentations, as well as depositions elicited in legal proceedings of Harden Manufacturing v. Pfizer and Franklin v. Warner-Lambert, the majority of which were created between 1990 and 2009. Using a systematic search strategy, we identified and reviewed all documents related to the STEPS trial, in order to identify key themes related to the trial’s conduct and determine the extent of marketing involvement in its planning and implementation.

Results

Documents demonstrated that STEPS was a seeding trial posing as a legitimate scientific study. Documents consistently described the trial itself, not trial results, to be a marketing tactic in the company’s marketing plans. Documents demonstrated that several external sources questioned the validity of the study before execution, and that data quality during the study was often compromised. Furthermore, documents described company analyses examining the impact of participating as a STEPS investigator on rates and dosages of gabapentin prescribing, finding a positive association. None of these findings were reported in two published papers.

Conclusions

The STEPS trial was a seeding trial, used to promote gabapentin and increase prescribing among investigators, and marketing was extensively involved in its planning and implementation.

INTRODUCTION

Pharmaceutical companies use a variety of techniques to promote their products, including “seeding trials.” Seeding trials are clinical trials, deceptively portrayed as patient studies, which are used to promote drugs recently approved or under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) by encouraging prescribers to use these medications under the guise of participating as an investigator in a clinical trial.1 In fact, marketing departments, rather than clinical research departments, are known to design and conduct these trials.2 Although seeding trials are not illegal, they are unethical. Their primary goal is to expose physicians to a new drug and have them interact with the pharmaceutical company sponsor and its sales representatives, in order to influence prescribing decisions, independent of any findings from the actual study. In addition, physician “investigators” are the actually trial subjects and this information is neither disclosed to them nor the human participants. There are no current estimates of how frequently seeding trials are conducted and most evidence of their planning and conduct has come from documents produced in tort litigation against pharmaceutical companies.3

A recent analysis of documents produced during litigation against Merck related to rofecoxib led to the first in-depth account of a seeding trial. Documentation described the marketing rationale behind the Assessment of Differences between Vioxx and Naproxen To Ascertain Gastrointestinal Tolerability and Effectiveness (ADVANTAGE) trial, as well as the marketing department’s involvement in trial conception and implementation.2

In 2006, an analysis of a limited set of documents produced during litigation against Parke-Davis overviewed Parke-Davis’s promotion of gabapentin, an anticonvulsant. Marketing involvement in the Study of Neurontin: Titrate to Efficacy, Profile of Safety (STEPS) trial was briefly mentioned among gabapentin marketing techniques, but discussion was necessarily incomplete; the investigation was limited to only a small subset of documents and depositions (approximately 250 of over 300,000 produced in litigation).4 The purpose of this investigation is to more fully evaluate whether STEPS was a seeding trial, including discussion of its conception, design, implementation, and impact on gabapentin prescribing. The recent availability of the complete set of documents and depositions produced during litigation provided a unique opportunity to examine the STEPS trial in more detail.

METHODS

Procurement of the Litigation Documents

We examined all documents produced during the Neurontin marketing, sales practices, and product liability litigation. In Harden Manufacturing v. Pfizer and Franklin v. Warner-Lambert, plaintiffs’ attorneys aggregated all documents produced by the defendants into an integrated database. Documents included internal and external correspondences, internal planning documents and presentations, clinical research reports, and market research analyses, the majority of which were created between 1990 and 2009. As consultants to the plaintiffs, investigators had access to the entire document production and all depositions taken for the cases; two investigators were paid consultants (SDK, DSE) and the third investigator was an unpaid consultant (JSR).

Review of the Litigation Documents

One investigator (SDK) conducted a primary review of all documents from the database, identifying those related to the STEPS trial using a systematic search strategy, searching “STEPS” in conjunction with the following key words: trial, marketing, promotion, seeding, advisory board, investigators, and the names of internal personnel and associated external investigators. Documents identified using these key search terms were reviewed, subsequently leading to retrieval of related or referred to documents that included STEPS-relevant content. The reviewer used a Boolean search because of the high frequency of the word “steps” within document production.

The original keyword searches returned approximately 3000 documents. The primary reviewer read all documents and identified a subset of approximately 400 documents relevant to STEPs and marketing related issues. These documents primarily consisted of internal memos, marketing presentations, and correspondences between Parke-Davis employees, STEPS investigators, and employees of Corning-Besselaar, a contract research organization. The primary reviewer re-read these documents in order to establish the chronology of the trials conduct and design and to identify broad themes reflecting the design and conduct of a seeding trial. In this iterative process, segments of text were organized according to their essential concepts,5,6 a similar method as was used recently with court documents to examine tobacco marketing, pharmaceutical marketing, and ghostwriting for scientific papers.2,4,7–9 Next, selected subsets of documents, those which were more critical to establishing themes and whose meaning were more open to interpretation, were reviewed by the other investigators to identify and further develop core themes. Finally, the primary reviewer again reviewed all of the documents for additional evidence to support or refute the core themes.

RESULTS

The STEPS Trial

The STEPS trial was a Phase IV uncontrolled, unblinded trial sponsored by Parke Davis. The STEPS trial stated objective was to study efficacy, safety, tolerability, and quality of life among gabapentin users when titrating the drug to patient effect. Parke-Davis recruited 772 investigators to participate in STEPS, enrolling 2759 patients; a ratio of approximately 4 patients per investigator. Informed consent documents explained that patients were enrolling in a study “designed to assess the safety and tolerability of doses of Neurontin (gabapentin) from 900 to 3600 mg daily whose partial seizures are not completely controlled by other drugs,” without mention of marketing objectives.10 Patients were initially given 900mg/day of Neurontin during the first week, and then were to have their doses titrated up to 1800mg/day, 2400mg/day and ultimately to 3600mg/day. Deviation from the rigid titration schedule led to exclusion from the study’s primary analysis. Titration stopped if the patient developed dose-limiting side effects or if the physician judged that the patient had reached an efficacious dose.11 The study ultimately resulted in two published articles in the journals Epilepsia and Seizure,12,13 one of which described the efficacy analysis, the other of which described the safety and tolerability analysis. Both articles were generally supportive, describing gabapentin as effective, safe, and tolerable.

STEPS Study Design and Execution

Poor Trial Design Undermines Scientific Validity

STEPS used an uncontrolled and unblinded design to study gabapentin efficacy, safety and tolerability, a questionable design, particularly for efficacy. In fact, two independent external sources questioned the STEPS’ scientific validity before it was initiated. The John Hopkins University Institutional Review Board (IRB) rejected the application for the STEPS trial, both initially and on appeal, stating “the board in its deliberation, voted to disapprove the protocol, since we believe that the entry criteria and outcome measures are too vague to allow any scientific conclusions to be reach [sic].”14 Parke-Davis also remarked in an internal memo that the FDA director of the Division of Drug Marketing Advertisements and Communications [DDMAC] believed that “the idea [of STEPS] was a good one from a marketing perspective, [but] she did not think the trial was needed to acquire the desired information on high dose use.”15

Furthermore, the STEPS trial used complicated inclusion and exclusion criteria for each analysis, limiting generalizability. For instance, for the tolerability analysis, there was a pre-specified, rigid up-titration method, which led to the exclusion of 87.3% non-random study participants. Following the completion of STEPS, Customer Business Units (CBUs), which were autonomous, regionally-focused branches of Warner-Lambert that planned and implemented marketing strategies, conceded that the study design was not rigorous enough for dissemination. For instance, a West CBU planning document acknowledged that “[though [STEPS] is likely to be published, [Territory Managers] will not be able to distribute results due to the open label format of the study.”16

Poor Trial Conduct Undermines Data Quality

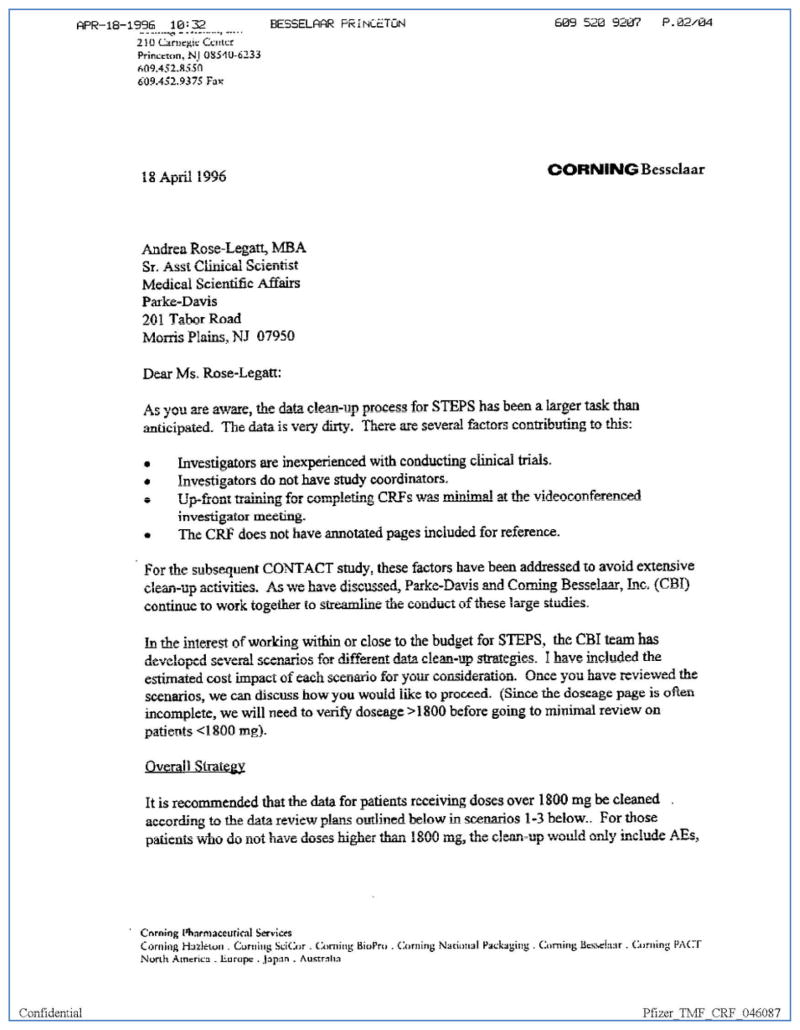

In addition to STEPS’ design limitations, the trial itself was not conducted in a way conducive to ensuring good data quality. Parke-Davis recruited site investigators with little or no clinical trial experience, provided insufficient training, and did not audit study sites prior to the beginning of the trial, which led to poor trial data quality. An April 1996 memo from Corning Besselaar [the Contract Research Organization used for the trial], noted that “the data clean-up process for STEPS has been a larger task than anticipated. The data was very dirty;” and added “Investigators are inexperienced with conducting clinical trials, investigators do not have study co-ordinators, up-front training for completing Case Report Forms (CRFs) was minimal at the videoconferenced investigator meeting, and the CRF does not have annotated pages included for reference.”17 (Figure 1) During statistical analysis, Parke-Davis also described data quality issues. For instance, site investigators were non-adherent to seize frequency assessment protocol, scheduling follow-up visits after more than 16 weeks, such that fewer than 25% of patients were assessed between follow-up weeks 13 and 16.18 In one case, 27 weeks elapsed between the baseline and final visit. Yet there were no mentions of data irregularity in either the internal research report or the published papers.

Figure 1.

Dirty STEPS Data: Corning-Besselaar, the Contract Research Organization, which ran STEPS sent Parke-Davis a series of letters in Spring 1996 detailing the poor quality of much of the STEPS data. In this memo, Corning-Besselaar describes several factors contributing to poor data, all of which were the result of deliberate decisions related to study conduct.

Marketing Involvement in STEPS

Marketing and Data Collection

Pharmaceutical sales representatives were directly involved in collecting and recording individual subject trial data. At a December 1995 Northeast CBU anticonvulsant advisory board meeting, a co-lead investigator explained that there was a greater completion rate when Parke-Davis representatives filled out the study forms.19 Although this appeared to raise concerns among some meeting attendees, a Parke-Davis marketing manager reassured the audiences that “STEPS is a Phase IV post-marketing study and does not follow the same rigorous protocols as phase III trials. We should stress with the representatives that they are not allowed to fill out paperwork (underline from original).”19 Nevertheless, the role some representatives played in data collection was not mentioned in the final published papers.

Marketing Rationale

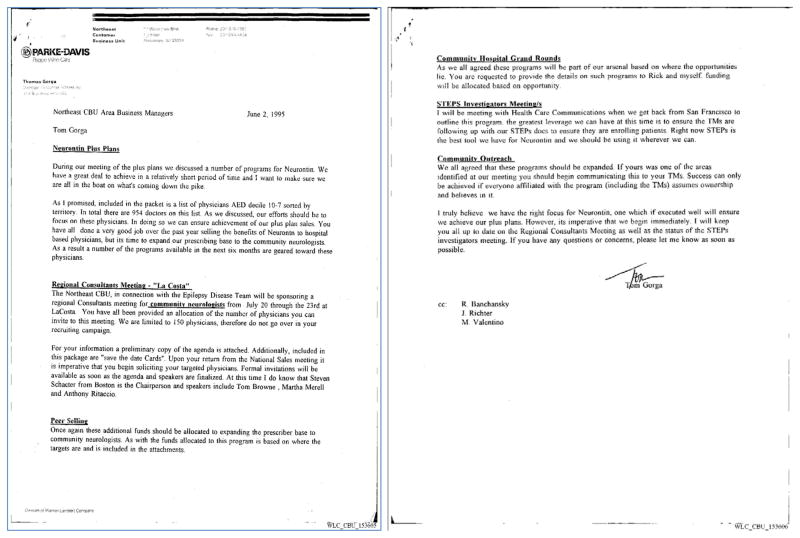

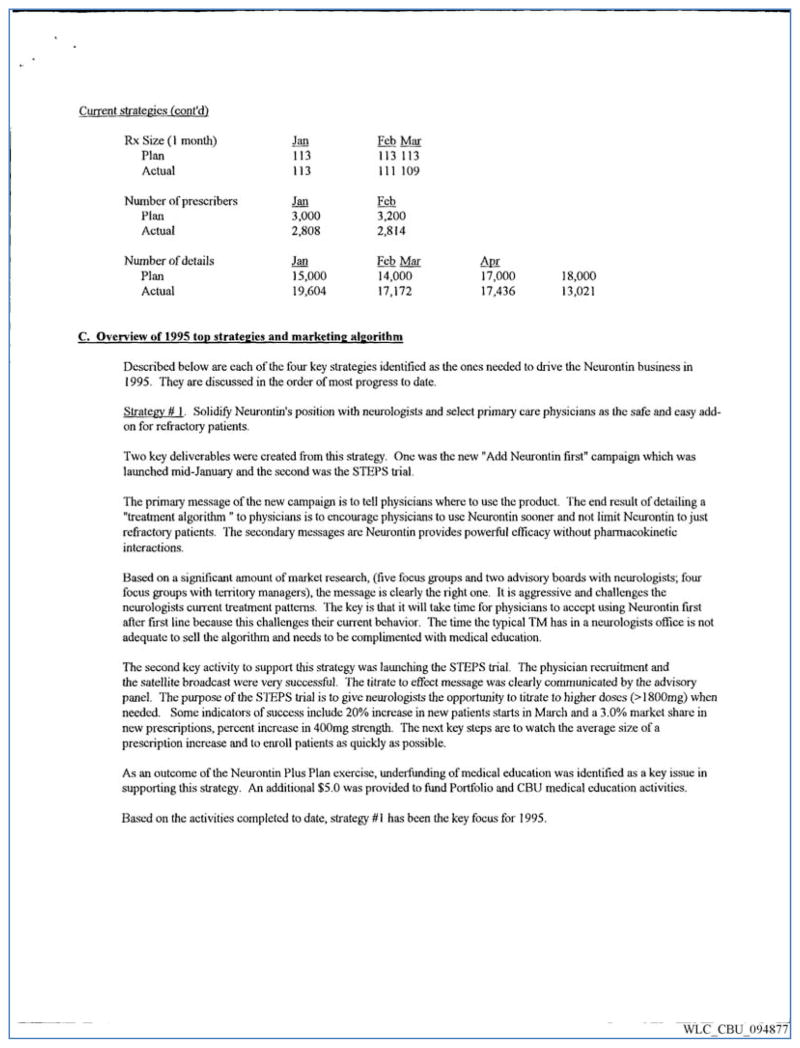

The STEPS trial was a key component of gabapentin marketing strategy. Multiple strategic plans cite the STEPS trial itself, as opposed to the anticipated trial findings, as a key marketing tool for the promotion of gabapentin. The 1996 Neurontin Situation Report identified STEPS as a key deliverable under the strategy “Solidify Neurontin’s position with neurologists and select primary care physicians as the safe and easy add-on for refractory patients.” Further, the purpose and anticipated impact of the STEPS trial are described as “to give neurologists the opportunity to titrate to higher doses (>1800mg) when needed. Some indicators of success include 20% increase in new patients’ starts in March and a 3% market share in new prescriptions, percent increase in 400mg strength. The next key steps are to watch the average size of a prescription increase and to enroll patients as quickly as possible.”20 (Figure 2) STEPS trial conduct facilitated Parke-Davis efforts to reach community and office-based neurologists. A North Central CBU document states: “the rapid growth of Neurontin depends on the ability to influence the large population of community neurologists that see the majority of non-refractory seizure patients. The STEPS trial … was a strong start to this Customer Business Unit (CBU) priority.”21 A similar push took place in the Northeast CBU, where one marketing memo stated “STEPS is the best tool we have for Neurontin and we should be using it wherever we can.”22 (Figure 3) These memos were written as the trial was ongoing.

Figure 2.

Neurontin Plus Plan, a comprehensive plan developed in the middle of 1995 to increase sales of Neurontin. The Northeast Customer Business Unit (CBU) included the STEPS trial as one of the marketing tactics to be used as a “tool” for increasing Neurontin prescriptions.

Figure 3.

The 1996 Neurontin Situation Analysis. Neurontin Situation Analyses recapped the marketing strategies employed for the previous year and introduced future strategies. This document shows that STEPS was intended to encourage investigator-physicians to increase their prescribed doses of Neurontin. The document also measures the success of Neurontin in terms of increases in prescriptions, dosage levels and market share.

In order for STEPS to reach as many community neurologists as possible, site investigators were widely recruited across the country. The company sent recruitment letters to approximately 5000 potential investigators.23 Ultimately, 1,542 “potential investigators” attended an introductory study briefing simulcast to nine different regional centers,24,25 where, along with study information, promotional information about gabapentin was also presented.21,26 To accommodate the involvement of such a large number of site investigators, sites were generally limited to a maximum of ten patients each and averaged 4 recruited patients per site. However, more influential site investigators were offered the opportunity to recruit more patients.27

Patient recruitment for the STEPS trial was also used as an opportunity to provide marketing information about gabapentin to physicians. Company representatives were encouraged to ask site investigators to institute “Shadow Days” during which epilepsy patients would make up the bulk of the clinic day’s schedule, permitting representatives to be present and encourage patient enrollment while simultaneously promoting gabapentin. The company also suggested offering promotional rewards to achieve enrollment goals. For example, company sales representatives rewarded some investigators for achieving specific recruitment milestones; physicians were given a free lunch after recruiting three patients and a free diner after seven patients.28 Patients were not informed of these “promotional reward” programs.

Patient recruitment for the STEPS trial was used not only as an opportunity to promote gabapentin, but also to block competing medications, particularly Lamictal (Lamotrigine). For instance, one employee explained that “at the very least, we should be looking to place as many managed-care patients as feasible in [STEPS] to prevent Lamictal starts.”29 A 1996 “Neurontin Situation Analysis” similarly suggested that an added benefit of the STEPS trial is that it “effectively blocked physicians from actively participating in the Lamictal/Alert trial.”30

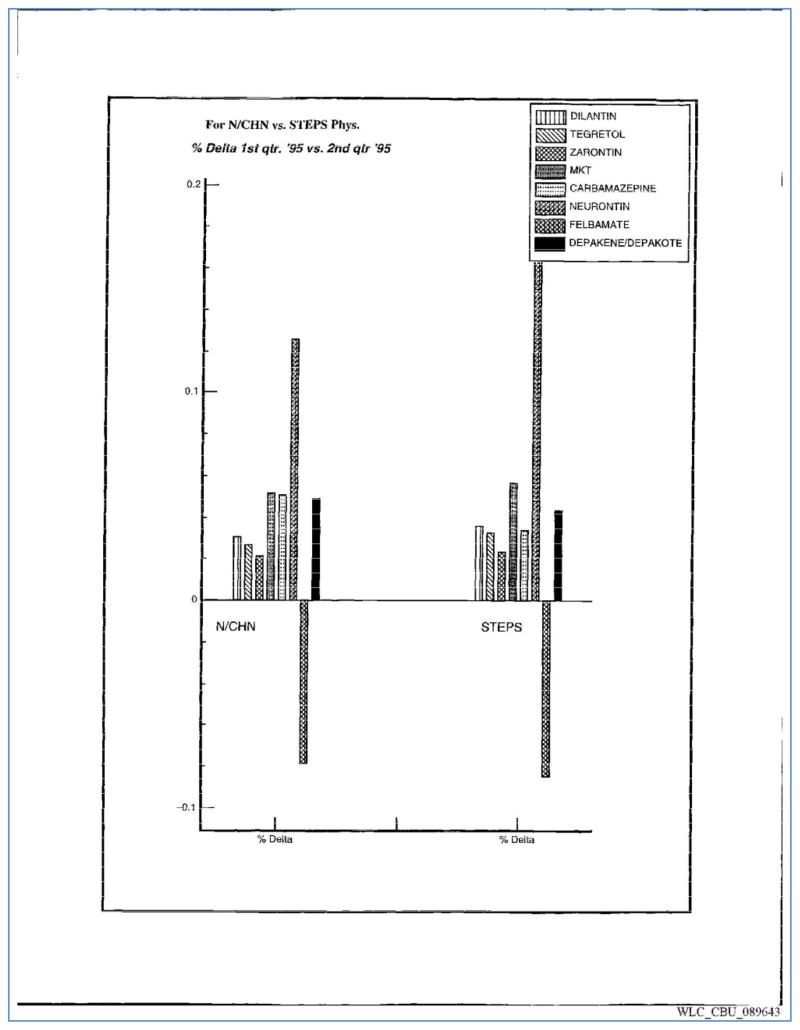

STEPS Effect on Investigator Prescriptions

The purpose of STEPS was to increase the prescription rates of physician-investigators. Parke-Davis monitored investigators’ prescribing of gabapentin during and after the completion of the STEPS trial through analyses completed by its Precision Marketing department and by the IMS Health Promotrak division. Neither the investigators, nor the patients, were informed that these analyses would be conducted as part of the study. One analysis compared prescribing before and after attendance at the STEPS introductory investigators briefing, finding a 38% increase in prescriptions after event attendance.31 The same study also found a 10% increase in average prescribed dose.31 Subsequent analysis demonstrated that investigator attendance was associated with persistently increased high-dose prescribing over time, although the rate of increase decreased.32 Other analyses compared prescribing among STEPS investigators with a control group of Neurologists and Child Neurologists, finding similarly increased prescribing among STEPS investigators.33,34 (Figure 4) The success of the STEPS trial in increasing prescriptions was reported within the 1996 “Neurontin Situation Analysis,” which described how investigators were “increasing their [Neurontin] shares … and their use of 400mg capsules.”30 Of note, these analyses were conducted prior to the dissemination of any trial results.

Figure 4.

A 1995 Selected Physician Titration Analysis, showing the dramatic increase in prescriptions by STEPS investigators as compared to a control group of Neurologists and Child Neurologists. Change in prescriptions of other anticonvulsants demonstrates no clear change among the two groups.

DISCUSSION

The STEPS trial was a seeding trial, used to promote gabapentin and increase prescribing among investigators, despite its stated scientific objective to examine efficacy, safety, and tolerability of the drug. Although STEPS was conducted fifteen years ago, the ethical issues illustrated by the trial’s conduct, and the data gained from Parke-Davis’ marketing analyses, have tremendous relevance in today’s debates over the limits and consequences of pharmaceutical industry sponsorship of Phase IV post-marketing clinical trials. Our analysis is only the second comprehensive account of a seeding trial based on primary source documents and clearly demonstrates how a clinical trial was designed, conducted, and explicitly used to promote marketing objectives, not science, without providing full informed consent to the patients and physicians who participated in the study.

Seeding trials have been used in the pharmaceutical industry for at least twenty years.1 However, since they are designed to impact sales, they may never be published and remain difficult to identify even when published. The only previous documentary account of a seeding trial, published in 2007,2 identified three main characteristics of seeding trials: marketing involvement in study conception and design, marketing involvement in data collection and analysis, and non-disclosure of the study’s true purpose from institutional review boards, patients, and investigators. Similarly, Kessler et al. described seeding trials, without the use of source documents, as lacking scientifically rigorous design or purpose and using the trial itself, not its findings, for wider marketing campaigns.1 STEPS differed from these previous examples as it was designed and conducted by a contract research organization, not a company’s marketing department. However, STEPS was clearly intended to promote gabapentin. The study, independent of any results, was repeatedly described as a means to market gabapentin and increase prescribed dosages. Our findings both corroborate previous descriptions of seeding trials, while also providing new insights into their execution.

There has been little academic research on the effect of seeding trials on prescribing. Danish researchers examined the effect on prescribing of participation in a clinical trial as a site-investigator,35 finding participation was associated with increased prescribing of the trial sponsor’s drug. In both ADVANTAGE and STEPS, the sponsor companies internally measured prescribing among investigators and found positive effects.2 While these internal analyses are suggestive, caution is warranted as the data and reports were not peer-reviewed and there were strong incentives to demonstrate that these seeding trials, as investments, were successful, potentially biasing the data. Additionally, much of the STEPS prescription data was uncontrolled and limited to summary descriptions, not raw data. Rigorously conducted research examining the impact on prescribing of participating as a trial investigator, or attending clinical trial marketing events, is necessary.

There were several ethical breaches within the STEPS trial. Principally, STEPS and all seeding trials prevent patients from making informed consent decisions about participation because the true marketing objectives are not disclosed. Informed consent is an established cornerstone of research on human subjects, both internationally36 and in U.S. law.37 During STEPS, among 2759 patients, there were 11 deaths, 73 patients experienced serious adverse events, and 997 experienced less serious adverse effects,11 suggesting that patients were at more than minimal risk. Second, investigators were also not fully informed, which is clearly unethical because these physicians were the intended study subjects. Third, the promotional rewards used within STEPS were also unethical. Conventional wisdom suggests that providing a small gift after data collection is acceptable, but unacceptable when given before,38 particularly if potentially coercive or presents undue influence.39

Seeding trials are not illegal and generally do not fall under the authority of the FDA, which has oversight only over clinical trials conducted as part of new drug applications or intended to support other label or advertising changes.40 However, the U.S. clinical trial regulatory system, principally under the authority of the U.S. Office for Human Research Protections, includes registration of clinical trials and protection of human research subjects that is dependent upon individual IRBs. As such, IRBs likely have the strongest potential to prevent seeding trials, outside of appeals to professionalism and ethical practice. However, recent research on IRBs suggest problems with conflict-of-interest and lax regulation, among both commercial and academic IRBs.41 These findings were substantiated by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, which demonstrated the inability of some commercial IRBs to protect against obvious violations of subject’s rights and suggested that IRBs were not effective at denying approval of scientifically unsound studies.42

Several steps may strengthen IRBs’ ability to prevent seeding trials. First, IRBs require stricter government oversight. All IRBs should be registered, accredited, and evaluated, with penalties for the approval of trials that do not meet ethical standards. Second, commercial IRBs should not be accredited. There is an inherent conflict of interest when an organization responsible for protecting human subjects subsists on payments from trial sponsors, potentially leading to companies shopping protocols to find the most receptive IRB. Third, IRBs should utilize a publicly-available repository to circulate previous reviews and rejections. Although the FDA requires prior IRB reviews be submitted as part of subsequent applications,43 this is not always practiced. For the STEPS trial, the concerns raised by the Johns Hopkins IRB might have alerted others. Finally, posting of original protocols within a publicly-available repository may also help to identify seeding trials, post-hoc, so that investigators, sponsors, and the IRBs which approved them can be identified. Even published seeding trials are challenging to recognize. But if a study is never published, or published misleadingly, there is no way for patients, physicians, or regulators to know the true nature of the trial. While mandatory trial registration within ClinicalTrials.gov is an important first step to address selective publication of all types of clinical trials, at this time registration does not include posting of study protocols, which could identify marketing-focused studies.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, because our analysis is limited to only one pharmaceutical company and describes events that took place 10–15 years ago, our findings may not be generalizable to today’s marketplace. However, our findings are consistent with the practices identified during another seeding trial.2 Second, we did not communicate with any company representatives or scientific investigators involved with STEPS. We based our analysis entirely upon document review, although we did also have access to deposition testimony. Third, any qualitative assessment of documents (or historical work in general) is susceptible to misinterpretation and unconscious bias. This analysis amounts to the authors’ best effort to faithfully and accurately reconstruct the planning, implementation and execution of the STEPS trial. Finally, given the large size of the document database, we may have missed relevant documents in the course of our search, although we used comprehensive search strategies to minimize this possibility.

In conclusion, the STEPS trial was a seeding trial masquerading as a scientific study. Parke-Davis performed an in-depth marketing analysis to track the effect of attendance at the STEPS introductory briefing and participation as a study investigator on the rate and dosage of gabapentin prescribing. No study publications mentioned the internal data quality problems, tampering (representatives filling out study forms) or the study’s marketing goals. Our analysis provides critical evidence suggesting that seeding trials are used as a promotional strategy by pharmaceutical companies. Reform of the current IRB system, as well as promoting better clinical trial practice in the human subjects research community, are necessary to prevent continued conduct of seeding trials by the pharmaceutical industry.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This project was not directly supported by any external grants or funds. Dr. Ross is currently supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08AG032886) and the American Federation of Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Mr. Krumholz and Dr. Egilman are currently paid consultants at the request of plaintiffs in litigation against Pfizer, Inc. related to gabapentin in the United States, while Dr. Ross is currently an unpaid consultant in the same litigation. Drs. Egilman and Ross were previously paid consultants at the request of plaintiffs in litigation against Merck and Co., Inc. related to rofecoxib in the United States.

References

- 1.Kessler DA, Rose JL, Temple RJ, Schapiro R, Griffin JP. Therapeutic-class wars--drug promotion in a competitive marketplace. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(20):1350–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411173312007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill KP, Ross JS, Egilman DS, Krumholz HM. The ADVANTAGE seeding trial: a review of internal documents. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(4):251–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-4-200808190-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kesselheim AS, Avorn J. The role of litigation in defining drug risks. JAMA. 2007;297(3):308–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinman MA, Bero LA, Chren MM, Landefeld CS. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):284–93. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson SJ, Dewhirst T, Ling PM. Every document and picture tells a story: using internal corporate document reviews, semiotics, and content analysis to assess tobacco advertising. Tob Control. 2006;15(3):254–261. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wayne GF, Connolly GN. How cigarette design can affect youth initiation into smoking: Camel cigarettes 1983–93. Tob Control. 2002;11 (Suppl 1):I32–39. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross JS, Hill KP, Egilman DS, Krumholz HM. Guest authorship and ghostwriting in publications related to rofecoxib: a case study of industry documents from rofecoxib litigation. JAMA. 2008;299(15):1800–1812. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.15.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Fax from Andrea Rose to Dr. XXXXX “Informed Consent Form and Clinical Study Agreement for Neurontin STEPS Study”. 1995 March 30; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 137698-137710. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_137698.pdf.

- 11.Magnus-Miller L, Podolnick O, Rose-Legatt A. Report No. 995-00057: Neurontin STEPS (Study of Titration to Effectiveness and Profile of Safety) Morris Plains, NJ: Parke Davis Medical and Scientific Affairs; Jul, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLean MJ, Morrell MJ, Willmore LJ, et al. Safety and tolerability of gabapentin as adjunctive therapy in a large, multicenter study. Epilepsia. 1999;40(7):965–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrell MJ, McLean MJ, Willmore LJ, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin as adjunctive therapy in a large, multicenter study. The Steps Study Group. Seizure. 2000;9(4):241–8. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011];Letter from Peter Kaplan to Andrea Rose “Re: STEPS IRB Approval”. 1995 May 1; Bates Numbers Pfizer/TMF/CRF 0046561-45568. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/PFIZER_TMF_CRF_046561.pdf.

- 15.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Record of FDA Contact by Irwin Martin. 1994 November 30; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 119162-119168. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_119162.pdf.

- 16.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke Davis Memo from Patrick Reichenberger to John McCarthy “Re: Neurontin Activities”. 1997 April 11; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 035854-035855. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_035854.pdf.

- 17.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Letter from Barbara Rainville to Andrea Rose-Legat “Re: Data Clean-Up Process”. 1996 April 17; Bates Numbers Pfizer/TMF/CRF 0046087-0046093. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/PFIZER_TMF_CRF_046087.pdf.

- 18.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Letter from Jo-Anne Paul to Paula Podolnick “Re: STEPS: Seizure Frequency Assessment Visits”. 1997 January 20; Bates Numbers Pfizer/TMF/CRF 047477-047478. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/PFIZER_TMF_CRF_047465.pdf.

- 19.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Memo from Laura Johnson to Area Business Managers “Re: Northeast Anticonvulsant Advisory Board Meeting”. 1996 January 4; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 156787-156788. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_156787.pdf.

- 20.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke Davis Marketing Report “1996 Neurontin Situation Analysis”. 1995 September 20; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 094876-094883. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_094876.pdf.

- 21.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke Davis Memo “Re: Revised North Central CBU Neurontin “Plus” Plan”. 1995 April 19; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 136177-136190. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_136177.pdf.

- 22.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Memo from Tom Gorda to the NECBU “Re: Neurontin “Plus” Plans”. 1995 June 2; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 153605-153606. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_153605.pdf.

- 23.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Memo “Re: “Neurontin STEPS Videoconference”. 1994 December 30; Bates Number WLC/CBU 146788. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_146778.pdf.

- 24.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Powerpoint “CNS Marketing Task Force Briefing”. 1995 March 30; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 084368-84401. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_084368.pdf.

- 25.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Meeting Minutes “Neurontin Development Team Meeting”. 1995 March 16; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 170739-170744. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_170739.pdf.

- 26.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Collected Materials “Introductory Investigators Briefing”. 1995 March 4; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 036290-036376. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_036290.pdf.

- 27.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Memo from David Davis to Rick Bancharsky “Re: STEPS Hospital Sites”. 1995 January 26; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 153844-153846. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_153844.pdf.

- 28.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Memo from Andrea Rose to Parke-Davis Distrubtion List “Re: Neurontin STEPS Study Enrollment”. 1995 June 28; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 153523-153524. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_153523.pdf.

- 29.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Memo from Rich Weiss to Mike Hoffman, et al “Re: Neurontin CONTROL Study”. 1994 December 5; Bates Number WLC/Franklin 00000039903. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_FRANKLIN_0000039903.pdf.

- 30.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke Davis Memo from Epilepsy Marketing Team to Dist List “Re: Situation Analysis for Neurontin”. 1996 June 12; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 090238-090256. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_090238.pdf.

- 31.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke Davis Memo from Jan Rizzo to Lara Ulrich et al “Re: Selected Physician Titration Analysis”. 1995 July 26; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 089640-089643. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_089640.pdf.

- 32.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Memo from Jan Rizzo to Lara Ulrich et al “Re: Selected Physician Titration Analysis”. 1995 November 9; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 089593-089595. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_089593.pdf.

- 33.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Memo from Lawton Griffin to Edda Guerrero “Re: AED Monthly Reports”. 1995 October 23; Bates Numbers WLC/Franklin 000033263-0000033271. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_FRANKLIN_0000033263.pdf.

- 34.Neurontin Marketing, Sales Practices, and Product Liability Litigation. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Parke-Davis Memo from Lawton Griffin to Edda Guerrero “Re: AED Monthly Reports”. 1995 December 7; Bates Numbers WLC/CBU 146230-146239. Available at: http://www.egilman.com/neurontindocs/STEPS%20Docs/WLC_CBU_146230.pdf.

- 35.Andersen M, Kragstrup J, Sondergaard J. How conducting a clinical trial affects physicians’ guideline adherence and drug preferences. JAMA. 2006;295(23):2759–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.23.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The World Medical Association. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Declaration of Helsinki. 1964 Available at http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html.

- 37.Code of Federal Regulations. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Protection of Human Subjects. 46.116:2009. Available at http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.htm.

- 38.Kumar R. Research Methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];Payment to Research Subjects - Information Sheet: Guidance for Institutional Review Boards and Clinical Investigators. 2010 October 18; Available at http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm126429.htm.

- 40.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];“Off-Label” and Investigational Use Of Marketed Drugs, Biologics, and Medical Devices - Information Sheet: Guidance for Institutional Review Boards and Clinical Investigators”; 2010 October 18; Available at http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm126486.htm.

- 41.Emanuel EJ, Wood A, Fleischman A, et al. Oversight of human participants research: identifying problems to evaluate reform proposals. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(4):282–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.United States Government Accountability Office. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];“Human Subjects Research: Undercover tests show the institutional review board system is vulnerable to unethical manipulation”; 2009 March 26; Available at http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d09448t.pdf.

- 43.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [Last accessed on April 4, 2011.];“Institutional Review Boards Frequently Asked Questions -Information Sheet: Guidance for Institutional Review Boards and Clinical Investigators”; 2010 October 18; Available at http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm126420.htm.