Abstract

Wear debris-induced osteolysis is a major cause of orthopaedic implant aseptic loosening, and various cell types, including macrophages, monocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts, are involved. We recently showed that mesenchymal stem/osteoprogenitor cells (MSCs) are another target, and that endocytosis of titanium (Ti) particles causes reduced MSC proliferation and osteogenic differentiation. Here we investigated the mechanistic aspects of the endocytosis-mediated responses of MSCs to Ti particulates. Dose-dependent effects were observed on cell viability, with doses >300 Ti particles/cell resulting in drastic cell death. To maintain cell viability and analyze particle-induced effects, doses <300 particles/cell were used. Increased production of IL- 8, but not IL-6, was observed in treated MSCs, while levels of TGF-β, IL-1β, and TNF-α were undetectable in treated or control cells, suggesting MSCs as a likely major producer of IL-8 in the periprosthetic zone. Disruptions in cytoskeletal and adherens junction organization were also observed in Ti particles-treated MSCs. However, neither IL-8 and IL-6 treatment nor conditioned medium from Ti particle-treated MSCs failed to affect MSC osteogenic differentiation. Among other Ti particle-induced cytokines, only GM-CSF appeared to mimic the effects of reduced cell viability and osteogenesis. Taken together, these results strongly suggest that MSCs play both responder and initiator roles in mediating the osteolytic effects of the presence of wear debris particles in periprosthetic zones.

Keywords: adult stem cells, implant wear, endocytosis, apoptosis, cytoskeleton, cell adhesion, cell proliferation, cytokines

INTRODUCTION

Over 500,000 total joint arthroplasties are done in the U.S. each year to treat end-stage arthritis,1 with substantial increase projected in coming years. Although total joint arthroplasty is profoundly successful, it is not without complication. Up to 20% of patients eventually require revision surgery, often due to aseptic loosening.1,2 At present, no drug therapy exists for aseptic loosening, and no effective protocol exists to determine which patients will suffer.

Wear debris-induced osteolysis is the principal cause of aseptic loosening. The cellular mechanism of the response to the large number of submicron-size debris particles involves macrophages, monocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts.3,4 These particles can elicit an inflammatory-like response in the surrounding tissues. Particle phagocytosis by macrophages at the bone-implant interface produces a pro-inflammatory cytokine cascade that eventually results in osteoclast stimulation and bone resorption. The cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and IL-1β, all result in abnormally high levels in synovial fluid and surrounding tissues of patients with failed implants secondary to aseptic loosening.5

Osteoprogenitor cells have been implicated as another target in particle-mediated osteolysis.6–14 Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in trabecular bone15,16 and adjacent to implants have osteoprogenitor activities and are critical contributors to maintaining osseous tissue integrity. Perturbation of MSC osteogenic activity may thus affect bony ingrowth and interface stability, leading to increased risk of loosening. We observed that exposure to submicron-size titanium (Ti) particles results in reduced osteogenic differentiation and proliferation, and enhanced apoptosis in human MSC's.6–8 However, the signaling pathways mediating these effects are unknown. We sought to determine whether debris-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine pathways are also involved in the particle-mediated inhibition of MSC functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Particulate Preparation and Characterization

Commercially pure Ti oxide microparticles (Sigma-Aldrich; size distribution: 0.2 to 0.8 μm median, – 0.488μm and mode, 0.426μm) were treated to remove >99.94% of adherent endotoxins.17 After passivation (25% nitric acid wash, 70° C, 1 h), particles were washed 3 times with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and sterilized in 70% ethanol for 30 min at room temperature. Next, particles were incubated in 5 alternating cycles of 0.1N NaOH/95% ethanol (30° C, 20 h) and 25% nitric acid (room temperature, 20 h)with sterile PBS wash between each incubation. After 3 additional washes in sterile PBS, particles were resuspended in MSC Growth Medium, consisting of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) with high glucose, 10% select batch of fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen), and penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B (Sigma). Particle numbers were counted with a Coulter Counter, and the suspension was stored at 4° C. For exposure to particles, the particle suspensions were warmed to 37° C and diluted with fresh medium to the appropriate concentration.

Isolation and Culture of MSCs

Human MSCs were isolated using IRB approved protocols (University of Washington, George Washington University) from bone marrow derived from femoral heads of patients undergoing hip arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis.18 MSCs were derived from 10 subjects. In some experiments, the RBL-1 rat basophilic leukemia cell line (American Type Culture Collection) was used as a mast cell control.

Osteogenic Differentiation of MSCs

Osteogenic medium consisted of Growth Medium containing osteogenic supplements (50 μg/mL L-ascorbate-2-phosphate, 0.1 μM dexamethasone, 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate, and 10 nM 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3; Sigma-Aldrich), and was changed every 3 days during culture. 1,25-Dihydroxy vitamin D3 was added for enhanced, stable osteogenic differentiation.19 To maintain release of cytokines for ELISA, fresh medium was added to existing medium to maintain the accumulated cytokines for the period assayed.

Treatment of MSCs with Ti Particles in vitro

In initial experiments, a particle concentration range that would elicit cellular response without high levels of cell death of MSCs was established. Culture expanded MSCs were seeded in Growth Medium at 2 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates, and allowed to adhere for 24 h. Growth Medium was then removed, and Growth or Osteogenic Medium containing specific concentrations of Ti particles (up to 1,000 particles/cell) were added to the experimental wells, and particle exposure continued for 24 h, and 7 and 14 days, with culture medium change every 3 days. At each time point, the culture medium was collected, and ELISA, real-time RT-PCR, Live/Dead Assay, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining were carried out for control and experimental samples.

ALP Histochemistry and Alizarin Red Staining

Enzyme histochemical staining was done according to manufacturer’s instruction using an ALP kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Staining of matrix mineralization was performed using Alizarin red (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described.6–8,15,16

Cell viability Assay

Live/Dead Assay was conducted followed manufacturer’s protocol outlined in the Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity kit (Invitrogen).

ELISA

Cytokine levels in culture medium supernatants were measured using ELISA kits (Ready Set Go eBioscience) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with the capture antibody and incubated overnight at 4°C. Wells were washed 4 times with PBS-0.01 % Tween, and blocked for 1 h with blocking buffer supplied in the kit. Human cytokine standards and MSC culture medium were added followed by incubation overnight. For IL-6 and IL-8 assays, the culture supernatants were diluted 1:100 to obtain values within the standard curve. After extensive washes, secondary antibody was added for 1 h followed by detection with a biotin-avidin/horseradish peroxidase system. After stopping the reaction with 2N H2SO4, reaction products were quantified spectrophotometrically as A450 values measured using a microplate reader.

Phalloidin and N-Cadherin Staining

MSCs were seeded at 1.0 × 104 cells/cm2 onto glass slides, and then treated with or without Ti particles (100 particles/cell) in Growth Medium. After 24-h incubation, Ti particles and dead cells were removed by PBS wash, and cultures were fixed with 4% buffered formalin (for Phalloidin staining) or with 2% buffered paraformaldehyde in methanol for 15 min at room temperature (for N-cadherin immunostaining). Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton for 5 min at room temperature and washed with PBS. After blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) in PBS, AlexaFluor 594(A12381) conjugated Phalloidin (Invitrogen; 200U/ml in 1% BSA) was used for cytoskeletal staining, and N-cadherin antibody (Invitrogen; 1:100 dilution) followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma) for N-cadherin immunostaining. Nuclear counter-staining was done using DAPI (R&D Systems), and cultures were mounted with VectaShield (Vector Labs). Fluorescence images were collected using a 63X, 1.4 N.A. oil objective on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (excitation/emission: Alexa Fluor 594-561 nm/572-700 nm; FITC – 494 nm/518 nm; DAPI – 345 nm/458 nm).

Real-Time RT-PCR Microarray Analysis

MSCs were seeded at 1.5 × 104 cells/cm2 and induced to undergo osteogenic differentiation in the absence or presence of Ti particles (100 particles/cell) as described above (n = 3). At specified time points, cellular RNA was harvested using Trizol (Invitrogen), purified with RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized using RT2 First Strand Kit (RT2 Profiler PCR Array System; SABioscience). Samples of cDNA synthesized from 0.1 μg starting RNA and RT2 SYBR Green master mix were loaded into 96-well pathway specific PCR array plates containing probes for 84 genes in the apoptotic and osteogenic pathways and 12 controls (SABiosciences), and processed in an iCycler iQ real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad). Data analysis was done using the RT2 Profiler PCR Array Data Analysis web portal (http://www.sabiosciences.com/pcr/arrayanalysis.php). Using the recommended cutoff criteria, a 2.75-fold increase or decrease of transcript level was considered for induction or repression, respectively.

Treatment of MSCs with GM-CSF and with Ti Particles

Cells seeded at 2.0 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates were treated for 24 h with or without Ti particles (100 particles/cell) in Growth Medium, after which cultures were washed with PBS several times to remove excess Ti particles and dead cells, and induced to undergo osteogenic differentiation as described above, in the presence or absence of recombinant human GM-CSF (R&D Systems) at various concentrations (0.25, 10, and 30 ng/ml) for 7 and 14 days. At these times, cells were harvested, rinsed with PBS, fixed with 4% buffered paraformaldehyde, and stained histochemically for ALP as described above.

ALP Activity Assay

Cell lysates were assayed using the ALP Kit (DALP-250, BioAssay Systems Quantichrom), based on the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl phosphate measured spectrophotometrically as A450. Enzyme activity was normalized to DNA content.

DNA Assay

Quant-iT™ PicoGreen dsDNA Kit (Invitrogen) was used to quantify double-stranded DNA in solution following manfacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Mean values ± SD are presented unless otherwise specified. Student’s t tests were performed based on ≥3 independent experiments on 3 different patient samples performed in triplicate. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of Ti Particle Exposure on Cell Viability and Proliferation

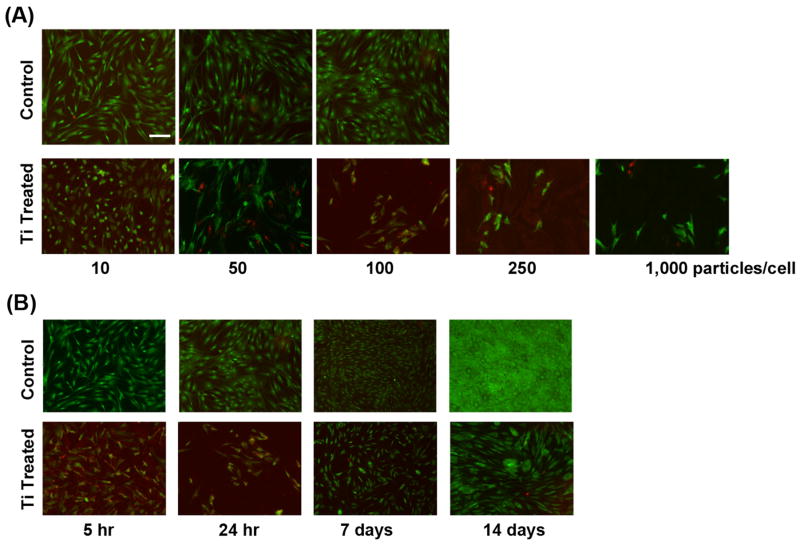

Exposure to Ti particles decreased cellular viability in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 1A). With 24 h exposure, MSC cultures presented with high 250 or 1,000 Ti particles/cell exhibited severely increased cell death compared to particle-free controls. To better analyze the cellular response mechanism, we sought to identify a particle dose that could elicit detectable responses without severely compromising cell viability. At a low concentration (10 particles/cell), no detectable effects on cell viability or activities were observed, when the particles were removed by washing within the 5 to 24 h period. On the other hand, exposure to 100 to 150 particles/cell reduced viability but allowed sufficient cells to remain and present detectable responses, including cytokine release, osteogenic differentiation, and cell growth. So complete cell death did not occur, but cellular function was clearly affected. This concentration thus represented a working condition under which biological effects of Ti particle exposure could be studied over 14 days. The 100 to 150 particles/cell concentration was thus selected for the remaining experiments.

Figure 1.

Reduced MSC viability upon exposure to Ti particles. (A) Cells exposed to 10 to 1,000 Ti particles/cell for 24 h stained with Live/Dead reagent showed dose dependent decrease in cell viability. (B) Cells treated with 100 particles/cell for 5 h or 24 h, and the latter cultures rinsed and supplemented with Growth Medium and then maintained until Days 7 and 14. Live/Dead staining showed that the longer exposure resulted in more cell death, but the remaining cells continued to proliferate. Results were obtained from cells isolated from Subject 1 (19-yr-old female) at passage 2, and are representative of 15 replicate assays using cells harvested from 7 subjects. Bar = 50 μm.

Cells were treated with 100 particles/cell for a period of 5 or 24 h, after which all non-adherent Ti particles were removed by washing. The cultures were harvested for analysis, with some cultures re-fed with medium and then harvested for analysis at days 7 and 14. Live/Dead Assay showed that after 5 h of exposure to Ti there was already an observable degree of cell death compared to untreated cells. At 24 h, the level of cell death became even more prominent, approaching greater than 80% at the higher doses. When the Ti particles were removed at 24 h and cells were allowed to grow, subsequent cell proliferation was slower in comparison to the control but not completely inhibited (Fig. 1B); but particle- treated cells still exhibited obvious proliferation, even at day 14.

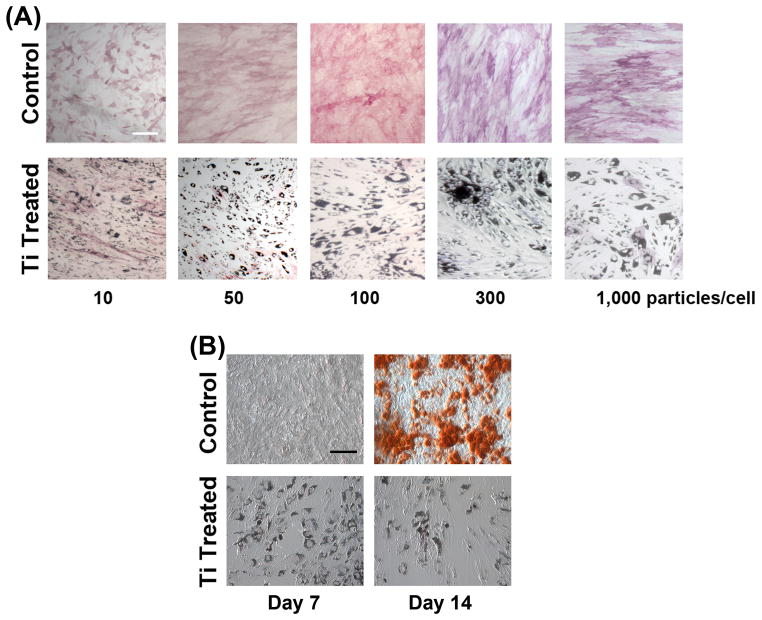

Effect of Ti Particle Exposure on Osteogenic Differentiation

We next determined the effect of Ti particle exposure on osteogenic differentiation. ALP activity showed uniform, high level inhibition of osteogenic differentiation with Ti particle exposure at all concentrations above 10 particles/cell (Fig. 2A). Thus, while the effect of Ti particles on cell viability and proliferation showed dose dependence within the concentration range tested, osteogenic differentiation was considerably more sensitive to Ti particle exposure, with drastic inhibition of ALP activity except at the lowest concentration. Alizarin red staining revealed drastic reduction in matrix mineralization on Day 14 in cultures exposed to 100 particles/cell (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Reduced osteogenesis of MSCs upon exposure to Ti particles. Cultures were treated with particles (10 to 1,000/cell) for 24 h and then allowed to grow for up to 14 days with Osteogenic Medium, and stained (A) for ALP activity (Day 14) or (B) for matrix mineralization (Alizarin red; Days 7 and 14, 100 particles/cell). Significant inhibition of MSC osteogenesis as indicated by ALP was seen at all concentrations except for 10 to 50 particles/cell (A). The suppression of osteogenic differentiation was confirmed as substantially reduced Alizarin red staining at Day 14 (B). Results presented in (A) were obtained from cells isolated from Subject 2 (55-yr-old male) at passage 2, except for 1,000 particles/cell, which was from Subject 1 (see Fig. 1 legend). Results in (B) are from cells of Subject 3 (50-yr-old female) at passage 2. All results are representative of those seen in cells harvested from 8 subjects, assayed in duplicates. Bar = 50 μm.

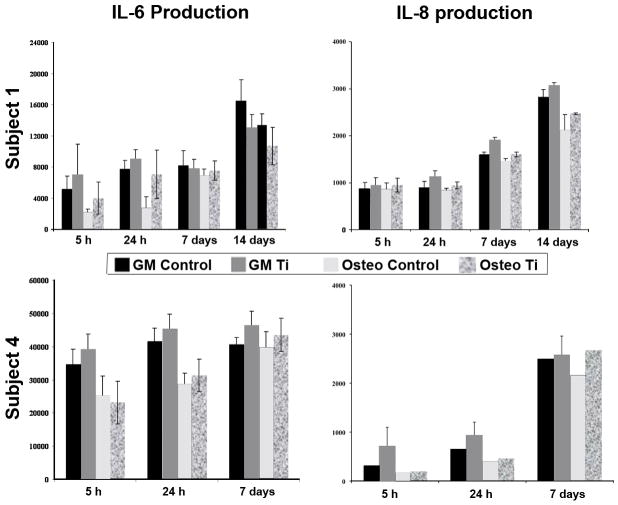

Ti Particle Exposure and Cytokine Release

MSCs derived from two representative subjects were treated with 50 to 100 Ti particles/cell and cultured in either Growth Medium or Osteogenic Medium. Culture media taken at 5 and 24 h and on days 7 and 14 were assayed for total cytokine release during each time period. Treatment with Ti particles resulted in a general profile of increased levels in the amount of IL-8 produced at each time point for both undifferentiated and osteogenic MSC cultures (Fig. 3). IL-6 production was also detected. In agreement with our recent report,20 IL-6 levels were consistently higher in undifferentiated cultures versus osteogenic cultures with slight increase over time. Ti particle exposure tended to increase IL-6 production, but insignificantly. Finally, we were unable to detect any TGF-β, IL-1β, and TNF-α release in either treated or control groups at all time points (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effect of exposure to Ti particles on IL-6 and IL-8 production by undifferentiated and osteogenically differentiated MSCs. Cultures were treated with 100 particles/cell for 5 h at 1 day post plating, or for 24 h at Day 1, Day 7 and Day 14. Secreted IL-6 and IL-8 levels were quantified by ELISA and results from cells derived from 2 subjects are presented: Subject 1 (see Fig. 1 legend) at passage 3 and Subject 4 (55-yr-old male) at passage 2. GM: Growth Medium; Osteo: Osteogenic Medium; Control: without Ti particle; Ti: with Ti particle. (A) IL-6 level. No consistent, significant changes were seen with particle exposure. (B) IL-8 level. Consistently higher levels of secretion upon particle treatment were seen in both undifferentiated and osteogenic cells. In general, a decrease in IL-6 and IL-8 production occurred upon osteogenic differentiation. Results are representative of those seen in cells isolated from 8 subjects, assayed in duplicates, and at various passages.

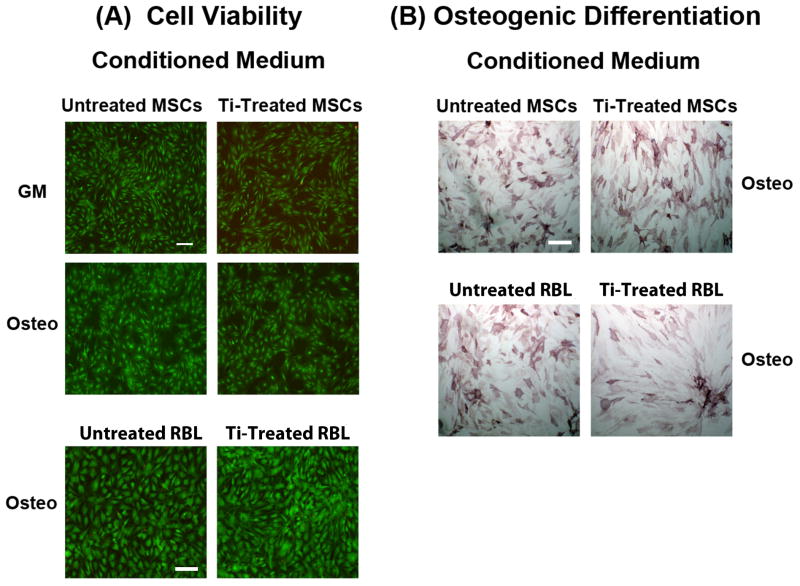

Effect of Culture Medium Supernatants from Ti Particle-Treated Cells on MSCs

To investigate whether the effects of Ti particles could be mediated by factors secreted by cells that previously interacted with and endocytosed Ti particles, conditioned culture media derived from Ti particle-treated cells were tested on untreated cells. Two sets of cell cultures were used: (1) cells treated with 50 to 100 Ti particles/cell for 24 h, followed by removal of particles, rinsing, and addition of fresh medium; and (2) untreated cells, similarly washed, and fed with fresh medium. Both sets grew for an additional 4 days, and the conditioned media collected. A new set of MSC cultures was then treated with the conditioned media. Some cultures were osteogenically induced with the addition of osteogenic supplements, and subsequently evaluated on the basis of alkaline phosphatase activity. Live/Dead Assay was performed on the control and osteogenic cultures, both maintained in conditioned medium derived from Ti-treated cultures or untreated cultures, and a set of cultures treated directly with Ti particles. Marked difference in cell viability occurred between the control cultures and cultures exposed to Ti particles. However, no discernible difference was found between the two groups of cells treated with the conditioned media as analyzed with the Live/Dead Assay. Also, osteogenic differentiation was not affected by treatment with conditioned culture media derived from Ti-treated cultures (Fig. 4B). But the difference between the conditioned medium treated cultures and those exposed directly to Ti particles was marked (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effects of conditioned medium from Ti particle treated MSCs on MSC viability and osteogenic differentiation. Conditioned medium was obtained from MSCs treated with 50 to 100 particles/cell for 24 h, with non-Ti particle treated cells as negative control. RBL cultures were similarly treated with particles, and conditioned medium collected to assess the general effect of particle exposure on cytokine release by inflammatory cells. (A) MSC viability (Live/Dead staining). Conditioned medium from particle treated cells (MSCs and RBL cells) did not affect viability of MSCs, either undifferentiated or undergoing osteogenesis. Bars = 50 μm. (B) MSC osteogenesis (ALP staining on culture day 14). Exposure to conditioned media from particle treated cells (MSCs and RBL cells) did not affect the extent of osteogenesis, as compared to cells treated with conditioned media derived from non-Ti particle treated cells. Bar = 50 μm. MSCs used were isolated from Subject 5 (54-yr-old male) at passage 2, and results are representative of those from 8 subjects, assayed in duplicates (MSC conditioned medium) or from 4 subjects, assayed in duplicates (RBL conditioned medium).

To assess whether MSCs could be affected by secreted products from other cells, including cells of the inflammatory pathway that were exposed to Ti particles, we tested the effect of conditioned medium derived from rat basophilic leukaemia (RBL) cell line exposed to Ti particles. RBL cells are a convenient system to model regulated secretion,21 and were chosen by virtue of their hematopoietic lineage and ease of usage. RBL cultures (3.0 × 107 cells) were treated with 50 Ti particles/cell for 24 h and culture medium collected after removal of particles; ~10% survived and were washed and prepared for conditioned medium harvesting on day 4 as above. Human MSC cultures were treated with the combined conditioned media from day 4 and from 24 h treatment. Live/Dead Assay and ALP staining were performed; no detectable effects on the viability or osteogenic differentiation activity of MSCs were found (Figs. 4A & B).

Effect of Purified Selected Cytokines on Cellular Function

To further assess whether a specific cytokine(s) is responsible for inhibiting MSC osteogenesis, we treated MSCs with varying concentrations (5, 10, 50, and 100 mM) of selected cytokines, including IL-8, IL-6, and IL- β, in both Growth and Osteogenic Media, and compared the effects to those seen in similar cultures treated with or without Ti particles. At all time points (24 h, 7 days and 14 days), the viability of cytokine treated cells was comparable to that in the control, non-particle treated group (data not shown). Cultures in Osteogenic Medium were also examined for osteogenic differentiation based on ALP staining. Treatment at all concentrations showed no effect on osteogenic activity of MSCs for all the cytokines tested (data not shown).

Effect of Titanium Particle Exposure on Gene Expression

To gain insight into the molecular basis of the Ti particle effects on MSCs, we profiled changes in MSC gene expression using custom-designed real-time RT-PCR microarrays for apoptosis (Table 1) and osteogenesis (Table 2) pathways. To examine early changes in gene expression, the microarray analyses were performed using RNAs isolated at 7 h after removal of the Ti particles at 24 h of exposure. In initial studies, we found that analyses carried out at 24 h post-treatment were not informational, since changes in gene expression, particularly in the apoptosis pathway, were essentially saturated. Comparison of the gene expression profiles of Ti particle-treated MSCs and control MSCs revealed several significant differences. In the osteogenesis pathway, Ti particle treatment resulted in a substantial and significant increase in expression of CSF2 (colony-stimulating factor-2 or granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, GM-CSF), and significant down regulation of COMP (cartilage oligomeric matrix protein), FGFR2 (fibroblast growth factor receptor type 2), IGF1 (insulin-like growth factor-1), BMP6 (bone morphogenetic protein-6), several collagen types, and Sox9. The apoptotic pathway analysis showed up-regulation of BAD (Bcl-2 antagonist of cell death), CD 70, and BCL2 (B cell lymphoma 2), with down-regulation of BCL10, TNFRSF11B (tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 11b), and ACTB (β actin). On the basis of our results (Tables 1 and 2), we chose to examine β-actin and CSF2 (GM-CSF) for their possible functional involvement in the Ti particle effects on MSCs.

TABLE 1.

Treatment with Ti Particles Induced Changes in Expression of Apoptosis-Related Genes Based on RT-PCR Microarray Analysis1

| Genes2 | Fold Change in Expression Level | p value |

|---|---|---|

| TNFRSF11B (Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 11b) | −4.18 | 0.0000000 |

| CD 70 (CD 70 molecule) | 3.06 | 0.0000001 |

| CASP8 (Caspase 8, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase) | −2.71 | 0.0000004 |

| BCLAF1 (BCL2-associated transcription factor 1) | −3.51 | 0.0000007 |

| ACTB(Actin, beta) | −3.76 | 0.0000024 |

| BCL10 (B-cell lymphoma 10) | −7.93 | 0.0203106 |

| BAD (BCL2-antgonist of cell death) | 1.77 | 0.0276331 |

| BCL2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) | 1.92 | 0.0823914 |

RNA samples isolated from cells derived from three subjects were used, with each analyzed in duplicate: Subject 1 (19-year-old female); Subject 2 (55-year-old male); and Subject 3 (50-year-old female).

Genes are listed in order of most significant change in gene expression levels based on p values.

TABLE 2.

Treatment with Ti Particles Induced Changes in Expression of Osteogenesis-Associated Genes Based on RT-PCR Microarray Analysis1

| Genes2 | Fold Change in Expression Level | p value |

|---|---|---|

| CSF2 (Colony stimulating factor 2) | 13.25 | 0.0000008 |

| COL15A1 (Collagen type XV, alpha 1) | −6.10 | 0.0000053 |

| COMP (Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein) | −5.71 | 0.0000054 |

| IGF1 (Insulin-like growth factor 1) | −17.91 | 0.0000097 |

| FGFR2 (Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2) | −28.71 | 0.0000175 |

| COL12A1 (Collagen type XII, alpha 1) | −3.96 | 0.0000214 |

| COL3A1 (Collagen type II, alpha 1) | −3.70 | 0.0000277 |

| BMP6 (Bone morphogenetic protein 6) | −6.09 | 0.0001284 |

| TGFBR2 (Transforming growth factor beta receptor II) | −13.40 | 0.0035344 |

| MMP10 (Matrix metalloproteinase 10) | 2.29 | 0.0035344 |

| COL10A1 (Collagen type X, alpha 1) | 3.11 | 0.0113237 |

| SOX9 (SRY (sex determining region Y)- box 9) | −8.24 | 0.0191369 |

RNA samples isolated from cells derived from three subjects were used, with each analyzed in duplicate: Subject 1 (19-year-old female); Subject 2 (55-year-old male); and Subject 3 (50-year-old female).

Genes are listed in order of most significant change in gene expression levels based on p values.

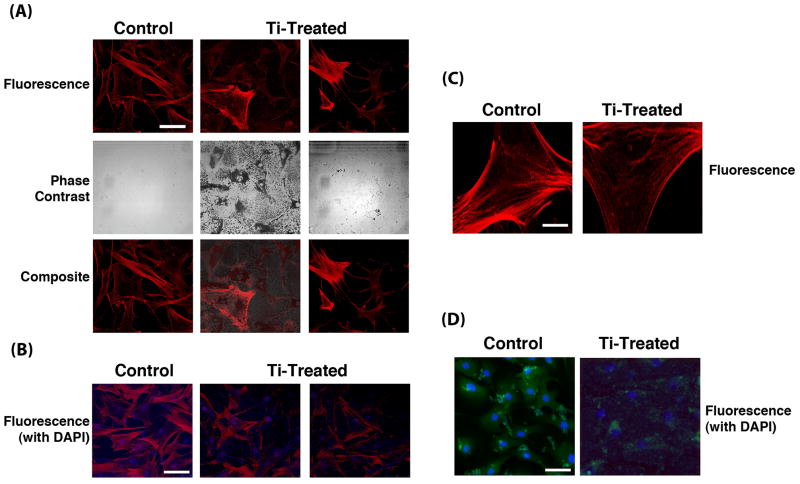

Effect of Titanium Particle Exposure on MSC Cytoskeletal Structure

The significant down-regulation of ACTB expression accompanying Ti particle treatment strongly suggested effects on the cytoskeletal architecture. This was examined using Phalloidin staining of the actin cytoskeleton and staining of cytoskeleton-associated adherens junctions using antibodies to the cell adhesion protein, N-cadherin. Substantially less intense cytoskeletal staining with Phalloidin was seen in MSCs exposed to Ti particles (Figs. 5A and B). Also, disorganized and patchy cytoskeletal architecture was apparent. Examination of the composite micrographs that included DAPI staining revealed that cells with endocytosed Ti particles mostly showed absence of staining, suggesting substantial cytoskeletal disruption and disorganization. Moreover, the particle-laden cells showed limited spreading compared to cells that did not contain Ti particles. N-Cadherin immunostaining showed cell morphologies consistent with this observation (Fig. 5D). Ti particle treated MSCs showed reduced staining and less distinct localization of adherens junctions, suggesting compromised association between adherens junctions and cytoskeleton.

Figure 5.

Cytoskeletal and adherens junction organization in MSCs exposed to Ti particles. (A) Phalloidin staining of actin cytoskeleton nuclear-staining with DAPI. One sample of control, untreated cells (left) and 2 samples of particle-treated cells (24 h at 100 particles/cell); center, minimally rinsed to show the presence of particles, and right, extensive washing to remove particles) are shown. Top row – Phalloidin staining; middle row - phase contrast microscopy showing the presence of particles in treated cells; bottom row – composite micrograph showing both Phalloidin and DAPI nuclear staining. Bar = 10 μm. (B) Another view of cells similar to those in (A) in composite fluorescence micrograph showing both Phalloidin and DAPI nuclear staining. Bar = 10 μm. (C) Higher magnification of cytoskeletal organization in control, untreated cells (left), and in extensively washed, particle-treated cells (right). Bar = 2.5 μm. (D) Adherens junction distribution. Control cells (left) and particle treated cells (right) were immunostained for N-cadherin. Particle treated cells generally displayed reduced and less distinct immunostaining, suggesting disruption of adherens junctions. Bar = 10 μm. MSCs used were derived from Subject 3. Results presented are representative of cells obtained from 2 subjects.

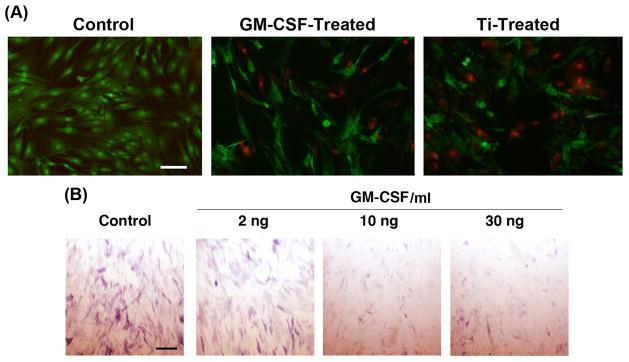

Effect of GM-CSF Treatment on Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Real-time RT-PCR results showed a substantial increase in CSF2 gene expression upon exposure to Ti particles, suggesting a possible functional role for CSF2, or GM-CSF, in Ti particle mediated inhibition of osteogenesis. We therefore tested the direct effects of GM-CSF on MSC viability and osteogenesis. GM-CSF treatment resulted in loss of MSC viability at a level comparable to exposure to Ti particles (Fig. 6), and on the basis of ALP histochemical staining, there was substantial inhibition of MSC osteogenesis. ALP enzymatic assay showed ~58% inhibition at 5 or 10 ng/ml GM-CSF compared to 83% inhibition upon treatment with 100 Ti particles/cell (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Effect of GM-CSF on MSC viability and osteogenesis. (A) Loss of MSC viability after treatment with GM-CSF (10 ng/ml), evaluated using Live/Dead staining at 24 h after treatment, was comparable to that in Ti particle treatment (100 particles/cell). (B) MSC osteogenesis shown by ALP activity on Day 14, showing a dose-dependent reduction in enzyme activity in osteogenically differentiating cultures. MSCs were harvested from Subject 3, and results are representative of those from 3 subjects. Bars = 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

Our previous studies demonstrated the deleterious effects of exposure to Ti particles on MSC proliferation and differentiation,6–8 but the mechanistic aspects of these effects and their biological consequences are still lacking. In this study, we first established a particle concentration range that reproducibly affected MSC functions without severely compromising cell viability. We observed that exposure to doses >300 Ti particles/cell resulted in almost complete cell death, while at ≤ 10 particles/cell, no detectable effects on MSCs were observed. The doses of 50 to 100 Ti particles/cell were a biologically useful range, and the number of wear particles in macrophages of retrieved tissues from revision surgery is in the same range.22–24

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are strongly implicated in wear particle mediated osteolysis.3 Cytokine activation of osteoclasts and macrophages has been demonstrated.25 Conversely, evidence suggests that particles also negatively affect osteoblast functions,26–31 thus suppressing bone formation. We therefore evaluated whether pro-inflammatory cytokines are involved in the Ti particle effects on MSC osteogenic differentiation. We first observed that MSCs are a major producer of IL-6 and IL-8. However, the mechanism for inhibition of osteogenesis is unlikely to be related to the production of IL-6 or IL-8 by MSCs themselves. Furthermore, the absence of TGF-β, IL-1β, and TNF-α production by MSCs suggests that these cytokines are also not functionally responsible. Specifically, direct addition of purified cytokines to MSCs resulted in no inhibition of osteogenesis, suggesting that exposure to these cytokines, including those secreted by other cells in the inflammatory cascade, cannot be implicated in the dramatic inhibition of osteogeneiss of MSCs. Total joint revision patients exhibit elevated levels of the above cytokines, which may contribute to compromised bone growth. For example, Lassus et al. 32 showed that the serum level of IL-8 corresponded with aseptic loosening of total hip arthroplasties, but the cellular source was unknown. This observation is consistent with our findings of increased IL-8 levels as a result of exposure to Ti particles, compared to control. Interestingly, Tanaka et al.33 found that both IL-6 and IL-8 were elevated in patients with loosening, but that IL-8 was a more reliable marker. MSCs express and produce IL-8, in response to infection, wound healing, or tensile strain.34–37 Thus, MSCs might contribute to increased IL-8production, which then acts on other cell types responsible for osteolysis, including osteoclasts and macrophages.

Endocytosis of Ti particles is another possible mode of particle action on MSCs, which we previously showed to be necessary for the observed effects.8 Phalloidin staining revealed that MSCs that have endocytosed Ti particles display a reduced and highly disrupted cytoskeletal architecture, supported by the irregular distribution and pattern of adherens junctions and concomitant reduction of β-actin expression. Cytoskeletal disruption is thus a likely cause of the inhibition of cellular functions, although the exact mechanisms remain to be analyzed.

While the clinical etiology of osteolysis seems to derive from wear, aseptic loosening without osteolysis also occurs.3 Wear debris from Ti implants could diminish the ability of MSCs to contribute to bony remodeling required for osseointegration over the long term. While Ti implants osseointegrate well initially, perhaps their ability to remain well fixed is hampered by effects of wear particles on MSCs. Taken together with previous findings that Ti particles induce IL-8 and MCP-1 in osteoblasts in vitro29 and that Ti reduces the osteogenic differentiation ability of adult human MSCs, these effects of wear particles most likely contribute to loosening of implants with Ti bearing surfaces.38

Patients with aseptic loosening have elevated IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α in their synovial fluid, though the source is unknown.39 Here we showed that MSCs may be responsible for the release of at least some (IL-6 and IL-8), but not all (IL-1β, TNF-α , and TGFβ ) of the cytokines. The MSC response is likely important in cell recruitment and activation of the inflammatory cascade leading to loosening. Ti implants are widely used in fracture fixation and joint arthroplasty. In retrieved periprosthetic tissues taken from arthroplasty revisions, wear debris particles consist predominantly of UHMWPE particles and particles from the metallic alloys, most commonly containing Ti or Co, which are also detectable in the synovial fluid. Of these particles, Co alloy debris seems more toxic,40 particularly when data from metal-on-metal bearing data are considered.41 Due to incomplete bony ingrowth into the implant surface, these wear particles penetrate the bone-implant interface.22,24 Interestingly, peri-implant osteolysis is not a major complication for most titanium fracture fixation implants.42 Information on the extent of particle release around these implants would be of interest.

The expression of a number of osteogenesis-associated genes was significantly altered in MSCs upon exposure to Ti particles, in particular BMP-6, IGF-1, FGFR2, and FGF2. BMP6 is highly active in inducing MSC osteogenic differentiation,43 compared to other BMPs, such as BMP-2 and -4.44 BMP-6 exerts its effects through pathways modulated by IGF-1, and expression of IGF-1 was up-regulated in osteoblasts treated with BMP-6.45 Mice harboring gain-of-function FGFR2 mutation displayed increased osteoblastic progenitors, with homozygotes developing bony overgrowth.46 FGF-2 is also expressed early in osteogenic cells exposed to mechanical stress.47 The potential involvement of GM-CSF in mediating the particle-induced effects is of particular interest, since this cytokine regulates the fusion of mononuclear osteoclasts into bone-resorbing osteoclasts.48 Osteoprogenitor MSCs are thus likely to play both responder and initiator roles in periprosthetic osteolysis. That Ti particle exposure affects the expression of these genes in MSCs, perhaps mediated via other cytokines found in the periprosthetic space and likely involving NFκB-dependent pathways,49 provides evidence for the molecular pathways responsible for the compromised osteogenic activity of the MSCs. More research is clearly needed to decipher the mechanisms responsible for these effects.

Another caveat of our study concerns the nature of the particles. In addition to the UHMWPE liner, Co-CR and Ti alloys are the most commonly used arthroplasty materials, from which wear debris particles are derived.4 In our earlier reports, we included other metallic particulates,6,7 and observed effects similar to those seen with Ti particles, which is the underlying reason for our continuing to use Ti particles to model the response; commercially pure Ti is also more readily available than the alloy materials. In our study, the chemical state of the passivated Ti particles in the form of Ti oxide, which is similar to the chemical state of Ti on the surface of Ti implant alloys and wear particles. In view of the higher cytotoxicity of Co-alloy particles, the effects and mechanisms of action of Ti and Co-alloy particles on MSCs will be compared in future studies.

The primary cause of debris-induced inflammation is the elevated activities of the innate immune cells. Our current findings, taken together with our previous observations, suggest that developing therapeutic means to inhibit cytokine release and/or particle endocytosis by the MSCs may offer a chance for an additional therapy for minimizing the osteolysis-inducing effects of wear debris in patients with metallic alloy orthopaedic implants. Other approaches may include the introduction of pro-osteogenesis agents or biologics, such as the BMP, OP-1,50 sonic hedgehog,51 or other bioactive peptides,30 into the tissue-implant interface as an adjunctive therapy to reverse the bone destruction due to wear particles. Clearly, more extensive in vivo and in vitro research is needed to address the utility of MSC adjunctive therapy prior to any evidence-based clinical application could be considered.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Paul Manner, George Washington University and University of Washington, for providing total joint arthroplasty human tissues. Supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (ZO1 AR41131), and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Health.

Literature Cited

- 1.Kurtz S, Mowat F, Ong K, et al. Prevalence of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 1990 through 2002. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1487–1497. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:128–133. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu-Amer Y, Darwech I, Clohisy J. Aseptic loosening of total joint replacements: mechanisms underlying osteolysis and potential therapies. Arthr Res Ther. 2007;9(Suppl 1):S6. doi: 10.1186/ar2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuan RS, Lee FY, Konttinen TY, Wilkinson JM, Smith RL. What are the local and systemic biologic reactions and mediators to wear debris, and what host factors determine or modulate the biologic response to wear particles? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:S42–48. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200800001-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hundric-Haspl Z, Pecina M, Haspel M. Plasma cytokines as markers of aseptic prosthesis loosening. Clinl Orthop Rel Res. 2006;453:299–304. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000229365.57985.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang ML, Nesti LJ, Tuli R, et al. Titanium particles suppress expression of osteoblastic phenotype in human mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:1175–1184. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang ML, Tuli R, Manner PA, et al. Direct and indirect induction of apoptosis in human mesenchymal stem cells in response to titanium particles. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:697–707. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okafor CC, Haleem-Smith H, Laquerierre P, Manner PA, Tuan RS. Particulate endocytosis mediates biological responses of human mesenchymal stem cells to titanium wear debris. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:461–473. doi: 10.1002/jor.20075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuan RS. Role of adult stem/progenitor cells in osseointegration and implant loosening. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2011;26 (Suppl):50–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schofer MD, Fuchs-Winkelmann S, Kessler-Thönes A, Rudisile MM, Wack C, Paletta JR, Boudriot U. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in the pathogenesis of Co-Cr-Mo particle induced aseptic loosening: an in vitro study. Biomed Mater Eng. 2008;18:395–403. doi: 10.3233/BME-2008-0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu R, Ma T, Smith RL, Goodman SB. Kinetics of polymethylmethacrylate particle-induced inhibition of osteoprogenitor differentiation and proliferation. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:450–457. doi: 10.1002/jor.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu R, Ma T, Smith RL, Goodman SB. Polymethylmethacrylate particles inhibit osteoblastic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 osteoprogenitor cells. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:932–936. doi: 10.1002/jor.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu R, Ma T, Smith RL, Goodman SB. Ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene wear debris inhibits osteoprogenitor proliferation and differentiation in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;89:242–247. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu R, Smith KE, Ma GK, Ma T, Smith RL, Goodman SB. Polymethylmethacrylate particles impair osteoprogenitor viability and expression of osteogenic transcription factors Runx2, osterix, and Dlx5. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:571–577. doi: 10.1002/jor.21035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuli R, Tuli S, Nandi S, Wang ML, Alexander PG, Haleem-Smith H, Hozack WJ, Manner PA, Danielson KG, Tuan RS. Characterization of multipotential mesenchymal progenitor cells derived from human trabecular bone. Stem Cells. 2003;21:681–93. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-6-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noth U, Osyczka AM, Tuli R, Hickok NJ, Danielson KG, Tuan RS. Multilineage mesenchymal differentiation potential of human trabecular bone-derived cells. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:1060–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bi Y, Seabold JM, Kaar SG, et al. Adherent endotoxin on orthopedic wear particles stimulates cytokine production and osteoclast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:2082–2091. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.11.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boland GM, Perkins G, Hall DJ, Tuan RS. Wnt 3a promotes proliferation and suppresses osteogenic differentiation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2004;93:1210–1230. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piek E, Sleumer LS, van Someren EP, Heuver L, de Haan JR, de Grijs I, Gilissen C, Hendriks JM, van Ravestein-van Os RI, Bauerschmidt S, Dechering KJ, van Zoelen EJ. Osteo-transcriptomics of human mesenchymal stem cells: accelerated gene expression and osteoblast differentiation induced by vitamin D reveals c-MYC as an enhancer of BMP2-induced osteogenesis. Bone. 2010;46:613–627. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pricola KL, Kuhn NZ, Haleem-Smith H, Song Y, Tuan RS. Interleukin-6 maintains bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell stemness by an ERK1/2-dependent mechanism. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:577–588. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seldin DC, Adelman S, Austen KF, et al. Homology of the rat basophilic leukemia cell and the rat mucosal mast cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1985;82:3871–3875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.11.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salvati EA, Betts F, Doty SB. Particulate metallic debris in cemented total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;293:160–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobs JJ, Skipor AK, Patterson LM, et al. Metal release in patients who have had a primary total hip arthroplasty. A prospective, controlled, longitudinal study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1447–58. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199810000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buly RL, Huo MH, Salvati E, Brien W, Bansal M. Titanium wear debris in failed cemented total hip arthroplasty : An analysis of 71 cases. J Arthroplasty. 1992;7:315–323. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(92)90056-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rader CP, Sterner T, Jakob F, Schütze N, Eulert J. Cytokine response of human macrophage-like cells after contact with polyethylene and pure titanium particles. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:840–848. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(99)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao J, Cs-Szabo G, Jacobs JJ, Kuettner KE, Glant TT. Suppression of osteoblast function by titanium particles. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:107–112. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199701000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pioletti DP, Takei H, Kwon SY, Wood D, Sung KL. The cytotoxic effect of titanium particles phagocytosed by osteoblasts. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;46:399–407. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19990905)46:3<399::aid-jbm13>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwon SY, Lin T, Takei H, et al. Alterations in the adhesion behavior of osteoblasts by titanium particle loading: Inhibition of cell function and gene expression. Biorheology. 2001;38:161–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fritz EA, Glant TT, Vermes C, Jacobs JJ, Roebuck KA. Chemokine gene activation in human bone marrow-derived osteoblasts following exposure to particulate wear debris. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;77:192–201. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maoqiang L, Zhenan Z, Fengxiang L, Gang W, Yuanqing M, Ming L, Xin Z, Tingting T. Enhancement of osteoblast differentiation that is inhibited by titanium particles through inactivation of NFATc1 by VIVIT peptide. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;95:727–734. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lenz R, Mittelmeier W, Hansmann D, Brem R, Diehl P, Fritsche A, Bader R. Response of human osteoblasts exposed to wear particles generated at the interface of total hip stems and bone cement. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009 May;89(2):370–8. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lassus J, Waris V, Xu JW, et al. Increased interleukin-8 (IL-8) expression is related to aseptic loosening of total hip replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120:328–332. doi: 10.1007/s004020050475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka R, Yasunaga Y, Hisatome T, et al. Serum interleukin 8 levels correlate with synovial fluid levels in patients with aseptic loosening of hip prosthesis. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:1049–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu CH, Hwang SM. Cytokine interactions in mesenchymal stem cells from cord blood. Cytokine. 2005;32(6):270–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yew TL, Hung YT, Li HY, Chen HW, Chen LL, Tsai KS, Chiou SH, Chao KC, Huang TF, Chen HL, Hung SC. Enhancement of wound healing by human multipotent stromal cell conditioned medium: the paracrine factors and p38MAPK activation. Cell Transplant. 2010 Dec 22; doi: 10.3727/096368910X550198. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DelaRosa O, Lombardo E. Modulation of adult mesenchymal stem cells activity by toll-like receptors: implications on therapeutic potential. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:865601. doi: 10.1155/2010/865601. Epub 2010 Jun 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sumanasinghe RD, Pfeiler TW, Monteiro-Riviere NA, Loboa EG. Expression of proinflammatory cytokines by human mesenchymal stem cells in response to cyclic tensile strain. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219(1):77–83. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nasser S, Campbell PA, Kilgus D, Kossovsky N, Amstutz HC. Cementless total joint arthroplasty prostheses with titanium-alloy articular surfaces. A human retrieval analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;261:171–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernigou P, Intrator L, Bahrami T, Bensussan A, Farcet JP. Interleukin-6 in the blood of patients with total hip arthroplasty without loosening. Section II. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1999;366:147–154. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199909000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daniel J, Ziaee H, Pradhan C, Pynsent PB, McMinn DJ. Renal clearance of cobalt in relation to the use of metal-on-metal bearings in hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010 Apr;92(4):840–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delaunay C, Petit I, Learmonth ID, Oger P, Vendittoli PA. Metal-on-metal bearings total hip arthroplasty: the cobalt and chromium ions release concern. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010 Dec;96(8):894–904. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricci WM, Gallagher B, Haidukewych GJ. Intramedullary nailing of femoral shaft fractures: Current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:296–305. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luu HH, Song W, Luo X, et al. Distinct roles of bone morphogenetic proteins in osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:665–677. doi: 10.1002/jor.20359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedman MS, Long MW, Hankenson KD. Osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells is regulated by bone morphogenetic protein-6. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:538–554. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grasser WA, Orlic I, Borovecki F, et al. BMP-6 exerts its osteoinductive effect through activation of IGF-I and EGF pathways. Int Orthop. 2007;31:759–765. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0407-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eswarakumar VP, Horowitz MC, Locklin R, Morriss–Kay GM, Lonai P. A gain-of-function mutation of Fgfr2c demonstrates the roles of this receptor variant in osteogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12555–12560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405031101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li CF, Hughes-Fulford M. Fibroblast growth factor-2 is an immediate-early gene induced by mechanical stress in osteogenic cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:946–955. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee MS, Kim HS, Yeon JT, Choi SW, Chun CH, Kwak HB, Oh J. GM-CSF regulates fusion of mononuclear osteoclasts into bone-resorbing osteoclasts by activating the Ras/ERK pathway. J Immunol. 2009;183:3390–3399. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crisostomo PR, Wang Y, Markel TA, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells stimulated by TNF-α , LPS, or hypoxia produce growth factors by an NFκB- but not JNK-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C675–682. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00437.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kann S, Chiu R, Ma T, Goodman SB. OP-1 (BMP-7) stimulates osteoprogenitor cell differentiation in the presence of polymethylmethacrylate particles. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;94:485–488. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ho JE, Chung EH, Wall S, Schaffer DV, Healy KE. Immobilized sonic hedgehog N-terminal signaling domain enhances differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;15;83(4):1200–1208. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]