Abstract

β-Lactamase inhibitors (clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam) contribute significantly to the longevity of the β-lactam antibiotics used to treat serious infections. In the quest to design more potent compounds and to understand the mechanism of action of known inhibitors, 6β-(hydroxymethyl)penicillanic acid sulfone (6β-HM-sulfone) was tested against isolates expressing the class A TEM-1 β-lactamase and a clinically important variant of the AmpC cephalosporinase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, PDC-3. The addition of the 6β-HM-sulfone inhibitor to ampicillin was highly effective. 6β-HM-sulfone inhibited TEM-1 with an IC50 of 12 ± 2 nM and PDC-3 with an IC50 of 180 ± 36 nM, and displayed lower partition ratios than commercial inhibitors, with partition ratios (kcat/kinact) equal to 174 for TEM-1 and 4 for PDC-3. Measured for 20 h, 6β-HM-sulfone demonstrated rapid, first-order inactivation kinetics with the extent of inactivation being related to the concentration of inhibitor for both TEM-1 and PDC-3. Using mass spectrometry to gain insight into the intermediates of inactivation of this inhibitor, 6β-HM-sulfone was found to form a major adduct of +247 ± 5 Da with TEM-1 and +245 ± 5 Da with PDC-3, suggesting that the covalently bound, hydrolytically stabilized acyl-enzyme has lost a molecule of water (H–O–H). Minor adducts of +88 ± 5 Da with TEM-1 and +85 ± 5 Da with PDC-3 revealed that fragmentation of the covalent adduct can result but appeared to occur slowly with both enzymes. 6β-HM-sulfone is an effective and versatile β-lactamase inhibitor of representative class A and C enzymes.

Keywords: β-Lactamase inhibitor, PDC-3, TEM-1, β-Lactamase, Sulfone, β-Lactam

1. Introduction

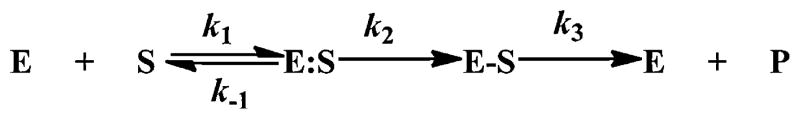

β-Lactam antibiotics are potent inhibitors of bacterial cell wall synthesis and eventually result in cell death [1–3]. To combat the lethal action of β-lactams, bacteria possess several mechanisms that confer resistance; one of these is the production of β-lactamases. In general, β-lactamases hydrolyze and inactivate β-lactams according to a three step mechanism (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

In this reaction scheme, E corresponds to the β-lactamase, S to the β-lactam substrate, E:S the Michaelis complex, E–S the acylated β-lactam, P the inactive product; k1 and k−1 represent the association and dissociation rate constants, k2 is the acylation rate constant, and k3 is the deacylation rate constant. As such, β-lactamases use either serine as a reactive nucleophile, or a metal ion (Zn2+) as an electrophile to catalyze antibiotic hydrolysis. Presently, two classification schemes are used to categorize β-lactamases [4,5]. Drawing upon the Ambler classification scheme as a model, “serine-based” β-lactamases are grouped into either class A, C or D, while β-lactamase that employ a metal ion are grouped into class B [4,6].

To counteract the emergence of β-lactamases in clinically important pathogens, mechanism-based inhibitors are sought [7]. Three β-lactamase inhibitors (clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam) are currently available and are administered in combination with a partner β-lactam antibiotic. These commercially available β-lactamase inhibitors are primarily effective against class A β-lactamases such as TEM-1, SHV-1, and CTX-M enzymes [5,8]. Except for possibly tazobactam, the β-lactamase inhibitors do not possess activity against class C or D β-lactamases [5,8]. The relatively limited spectrum of current inhibitors, together with the recent emergence of novel β-lactamases which possess resistance to inactivators necessitate the search for novel antibiotic combinations [7].

Exploring the potency of penicillanic acid sulfones as inhibitors of class A and C β-lactamases has assumed increasing importance in the last decade [9]. The many varieties of this series include C6-unsubstituted systems (e.g. sulbactam), C2-substituted analogs (e.g. tazobactam), and C6-unsaturated analogs, such as LN-1-255, a 6-(α-pyridylmethylidene)penicillanic acid sulfone possessing a siderophore-mimicking catecholic moiety appended at C2. LN-1-255 has proved to be highly active against Gram negative bacteria possessing extended-spectrum class A β-lactamases [10]. Other 6-alkylidene-2′-substituted penicillin sulfones have also been documented to possess potent inhibitory activity against numerous β-lactamases, including class D carbapenemases [11].

While C6-hydroxyalkyl β-lactams are well known due to the carbapenem and penem series of antibiotics, in the penicillin scaffold, published mechanistic inhibitory studies have focused solely on 6-(hydroxyalkyl)penicillin sulfides [12], and not on the mechanistically dissimilar sulfones. Three decades ago, Kellogg advanced that 6-hydroxymethylpenicllin sulfone was useful as an inhibitor of β-lactamase [13]. Subsequently, Buynak et al. showed that the hydroxymethyl group of this series can be further modified to mercaptomethyl to broaden the spectrum of inhibition to include the inhibition of metallo-β-lactamases [14]. In order to optimize the structure activity relationships of C6-penicillin sulfones, the mechanistic significance of the C6 substituent was studied further. A systematic series of 6-substituted penicillin sulfones was recently prepared and evaluated by Nottingham et al. [15]. The inhibitory activity was found to be highly dependent on C6 side chain structure, particularly including the precise location of side chain functionality, including a hydroxyl group appended to the alkyl side chain.

Based upon these deficiencies in comparative data, this study quantifies the activity of the simplest, and most potent, member of the C6-(hydroxyalkyl)penicillin sulfone series, 6β-(hydroxymethyl)penicillanic acid sulfone (1, 6β-HM-sulfone) and to explore its mechanism of inhibition. 6β-HM-sulfone can partner well with ampicillin to enhance susceptibility of Escherichia coli expressing two representative class A and class C β-lactamases, TEM-1 and the AmpC of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, PDC-3, respectively. 6β-HM-sulfone can serve as an important scaffold to further develop inhibitors against class A and C β-lactamases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Bacterial strains

For disc diffusion testing, Escherichia coli ATCC35218 carrying blaTEM-1 and E. coli DH10B pBC SK(−)blaPDC-3 were used. For purification of β-lactamases, E. coli DH5α pUC19 carrying blaTEM-1 (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), while E. coli BL21-Codon Plus-(DE3)-RP cells pET24a + blaPDC-3 was the source of PDC-3. The cloning of blaPDC-3 into the pBC SK(−) phagemid and the pET24a + plasmid has been previously described [16].

2.2. Antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors

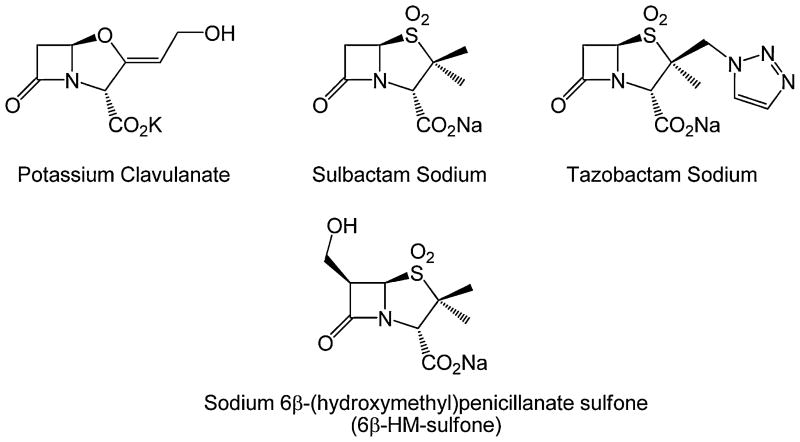

The antibiotics used in this study were obtained from their respective manufacturers as indicated: ampicillin from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); sulbactam, sodium salt from Pfizer (Groton, CT); clavulanic acid, potassium salt from USP (Rockville, MD); tazobactam, sodium salt, from Lederle Laboratories (Pearl River, NY); and nitrocefin from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ). The sodium salt of 6β-HM-sulfone (263 Da) was synthesized by Syncom BV (Groningen, Netherlands) and Dr. John D. Buynak (SMU, Dallas, TX). Chemical structures of β-lactamase inhibitors are represented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of the potassium clavulanate, sulbactam sodium, tazobactam sodium, and sodium 6β-HM-sulfone.

2.3. Susceptibility testing

Disc diffusion assays were conducted using the guidelines of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [17]. Briefly, ampicillin discs containing 10 μg of ampicillin and ampicillin-sulbactam discs containing 10 μg of ampicillin and 10 μg of sulbactam were purchased from Becton Dickinson. A solution containing 10 μg of 6β-HM-sulfone was pipetted onto ampicillin disks containing 10 μg of ampicillin and allowed to dry for 1 h. Colonies, directly re-suspended into sterile water equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard, were used to inoculate Mueller Hinton (MH) agar plates. The discs were carefully placed on each plate. The bacteria were grown at 37 °C for 18 h and zone diameters were measured. Resistance or susceptibility ampicillin and ampicillin-sulbactam was determined based on the criteria of CLSI [18]. The ampicillin-sulbactam breakpoints were used as a guideline for the ampicillin-6β-HM-sulfone breakpoints.

2.4. β-Lactamase purification

Two sources of the purified TEM-1 β-lactamase were used in this study. Initially, the TEM-1 β-lactamase was purified from E. coli DH5α pUC19 carrying blaTEM-1by boronic acid affinity chromatography [19,20] and HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 chromatography (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden). Subsequently, the purified TEM-1 β-lactamase was a kind gift of Dr. Jean-Marie Frère (Université de Liège, Belgium). The PDC-3 β-lactamase was purified by preparative isoelectric focusing and HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 chromatography, as previously described [16].

2.5. Inhibition of β-lactamase activity

The inhibitor concentration that caused 50% reduction in nitrocefin (100 μM) hydrolysis after 5 min of pre-incubation of the enzyme and inhibitor at 25 °C was denoted as IC50.

The partition ratio (kcat/kinact) or the number of inhibitor (I) molecules required to inactivate one molecule of enzyme (E) was determined by inhibitor-enzyme molar ratio that resulted in > 99% inactivation after 20 h of incubation [21].

The progressive inactivation of TEM-1 and PDC-3 by 6β-HM-sulfone was also investigated. The progressive inactivation assay was run by diluting each β-lactamase in buffer to a known concentration, then incubating the enzyme with varying amounts of inhibitor over time. At each time point the partially inactivated enzyme was removed and placed in a fresh 100–200 μM solution of nitrocefin and the amount of remaining β-lactamase activity was measured compared to an inhibitor-free control enzyme incubated over the same time period.

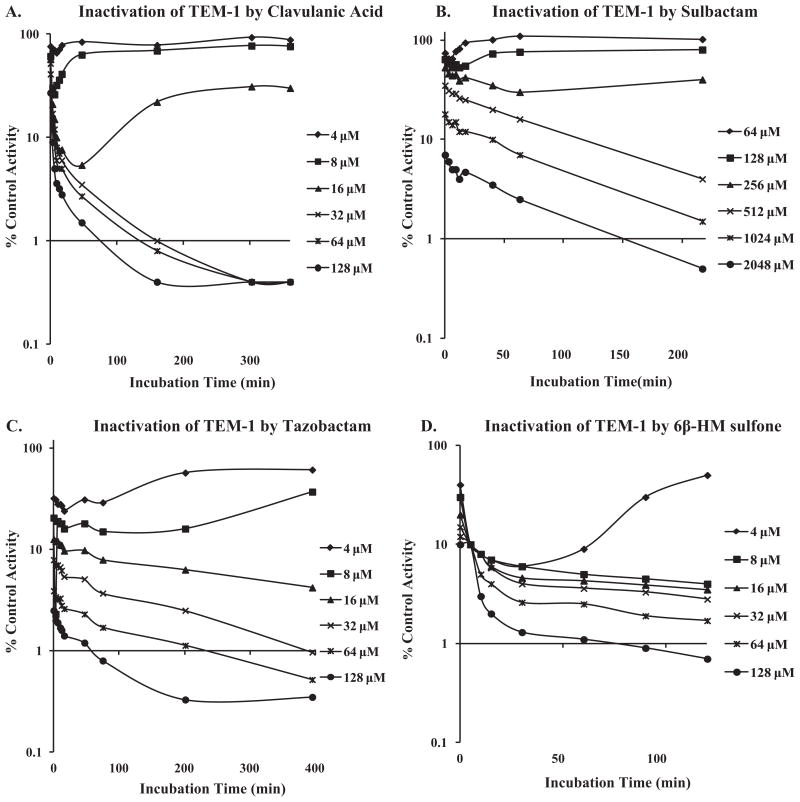

The β-lactamase and inhibitor interact according to the following proposed Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

In this model, formation of the E:I non-covalent enzyme:inhibitor complex represents the dissociation constant, Kd, which is equivalent to k−1/k1. The acylation step or formation of E–I is represented by the rate constant, k2. The hydrolysis of the E–I acyl-enzyme corresponds to rate constant, k3. The rearrangement of E–I to the E–T enzyme–tautomer complex is signified by the rate constant k4. Finally, the formation of a terminally inactivated acyl-enzyme species, E–I*, is represented by rate constant k5. Here, the partition ratio is equivalent to (k2·k4·k5)/(k2 + k3 + k4 + k5).

2.6. ESI-MS analysis: TEM-1 and PDC-3 β-lactamase

ESI-MS was performed at two different locations. A Micromass Ultima triple quadrupole (Waters, Milford, MA) and Sciex API-150 single quadrupole (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) was used for TEM-1 studies done at Groton Connecticut and a Q-STAR XL Quadrupole-Time-of-Flight mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA) was used for PDC-3 analysis in Cleveland, Ohio.

6β-HM-sulfone was reacted with TEM-1 β-lactamase at inhibitor:enzyme (I/E) molar ratios between 100:1 and 200:1 at 25°C for 1 h. Additionally, unreacted TEM-1 was used as a control. Samples were prepared at ~2 pmol/μl in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 7.8 and 5–50 μL were injected onto VYDAC C-4 columns (Grace, Deerfield, IL) and eluted with gradients of 0–80% B using various time courses (A = 0.05% TFA in water, B = 0.05% TFA in acetonitrile). Mass spectra were obtained using a Micromass Ultima triple quadrupole mass spectrometer and a Sciex API-150 single quadrupole mass spectrometer operating in the open access mode. Data were collected and processed using the manufacturer’s deconvolution programs to calculate molecular weight results at zero charge state and an error of ±5 amu was assigned to each measurement.

6β-HM-sulfone was incubated with PDC-3 β-lactamase in phosphate-buffered saline at I/E molar ratios of 20:1 at 25 °C for 15 min. In like manner to TEM-1, PDC-3 was prepared alone to run as a control. The samples were acidified by the addition of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and immediately desalted and concentrated using a C18 ZipTip (Millipore, Bedford, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were equilibrated to 50% acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid then placed on ice and analyzed within 1 h. A Q-STAR XL Quadrupole-Time-of-Flight mass spectrometer equipped with a nanospray source was used to detect mass spectra by infusing the samples at a rate of 0.5 μl min−1 and the data were collected for 2 min. Spectra were deconvoluted using the Analyst program (Applied Biosystems) and an error of ±5 amu was assigned to each measurement.

2.7. Computer-assisted molecular modeling

Computer-assisted molecular modeling was performed using the FlexX docking software (BioSolveIT) within the Sybyl platform (Tripos Inc.). The PDB files 1ZG4 (TEM1) and 1KE4 (AmpC) were utilized [22,23]. The following customizations were made to terminal C–C–O–H torsion angles in the respective active sites: 1ZG4: Ser70_Cα_Cβ_Oγ_Hγ = −25; Ser235_Cα_Cβ_Oγ_Hγ = 90; 1KE4: Ser64_Cα_Cβ_Oγ_Hγ = −25; Tyr150_Cε1_Cζ_OH_HH = 305; Thr316_Cα_Cβ_Oγ1_Hγ1 = 90.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Susceptibility testing

Zone diameters were measured for ATCC 35218 E. coli expressing blaTEM-1 and E. coli DH10B with pBC SK(−) blaPDC-3 (Table 1). Both strains were resistant to ampicillin with zone sizes of 6 mm. When ampicillin was combined with sulbactam or 6β-HM-sulfone zone sizes increased to 15 mm and 20 mm, respectively, thus indicating synergy between the β-lactam antibiotic and the respective β-lactamase inhibitors. Ampicillin when combined with 6β-HM-sulfone was the most potent combination against these strains as it produced the largest increase in zone diameter.

Table 1.

Disc diffusion.

| Strains | Ampicillina | Ampicillin-sulbactama | Ampicillin-6β-HM-sulfonea |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC35218 E. coli blaTEM-1 | 6 (R) | 15 (S) | 20 (S) |

| E.coli DH10B pBC SK(−) blaPDC-3 | 6 (R) | 15 (S) | 20 (S) |

10 μg of ampicillin and each inhibitor were used in the disc assay. R, resistant; S, susceptible.

3.2. Kinetic studies with β-lactamase inhibitors

6β-HM-sulfone possessed activity against TEM-1 with an IC50 value of 12 nM ± 2 (Table 2). Strikingly, 6β-HM-sulfone was the most potent inhibitor of PDC-3 when compared to sulbactam and tazobactam with an IC50 value at 5 min of 180 nM ± 36 (Table 2). All other tested inhibitor possessed >6-fold higher IC50 values for PDC-3. This difference is most likely due to an increase in affinity for 6β-HM-sulfone over the commercially available inhibitors.

Table 2.

Inhibitor steady state kinetic parameters.

| Inhibitor | TEM-1 IC50 (5 min) (nM) |

TEM-1 kcat/kinact |

PDC-3 IC50 (5 min) (nM) |

PDC-3 kcat/kinact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6β-HM-sulfone | 12 ± 2 | 174 ± 35 | 180 ± 36 | 4 ± 1 |

| Sulbactam | 1300 ± 260 | 5565 ± 1113 | 4300 ± 860 | 14 ± 3 |

| Tazobactam | 15 ± 3 | 348 ± 70 | 1100 ± 220 | 9 ± 2 |

| Clavulanic acid | 60 ± 12 | 348 ± 70 | >100,000 | NDa |

Data were unable to be determined (ND).

Compared to clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam, the partition ratio (kcat/kinact) or turnover number of 6β-HM-sulfone for TEM-1 at 20 h was 174 molecules (99% irreversible inhibition). 6β-HM-sulfone also demonstrated the lowest partition ratio for PDC-3 (4 molecules required to inactivate one molecule of enzyme).

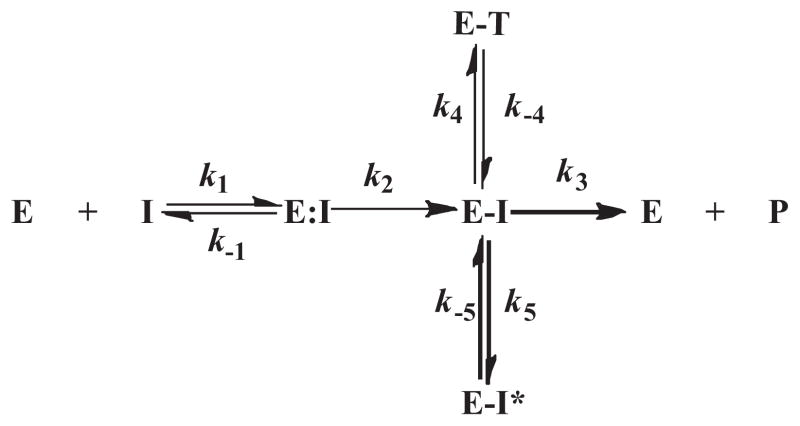

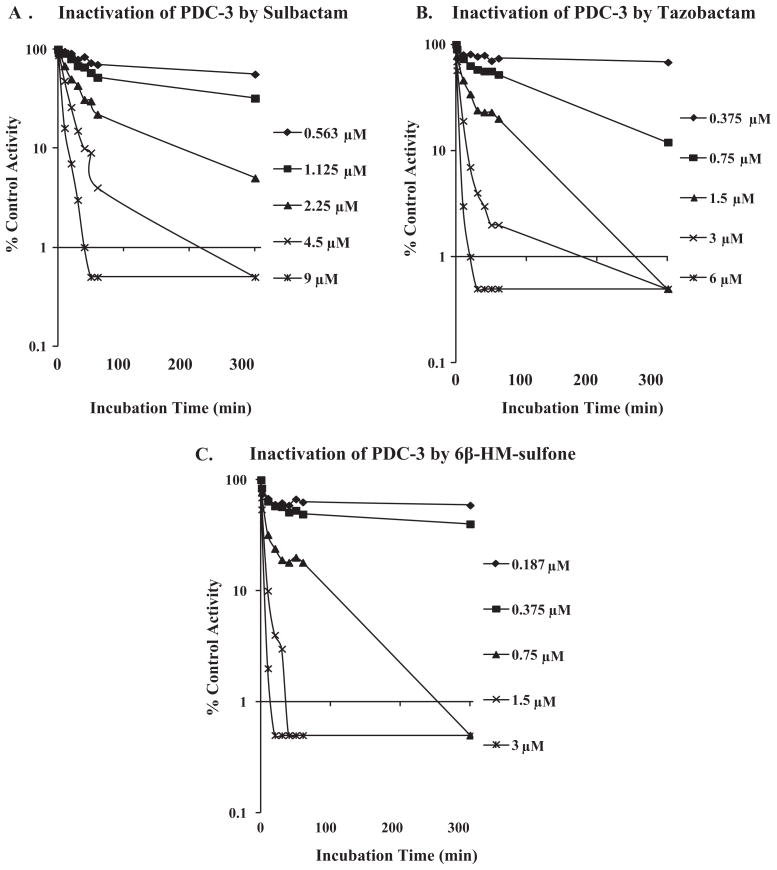

The progressive inactivation by 6β-HM-sulfone was investigated using the TEM-1 and PDC-3 β-lactamases (Figs. 2A–D and 3A–C). 6β-HM-sulfone, tazobactam, clavulanic acid, and sulbactam demonstrated rapid, first-order inactivation kinetics with the extent of inactivation being related to the concentration of inhibitor. Inactivation was incomplete and reversible at lower concentrations of inhibitor, while at higher concentrations of inhibitor, inactivation was irreversible. Clavulanic acid was not measured with PDC-3 as it displayed >100,000 nM IC50 for PDC-3.

Fig. 2.

Progressive inactivation of nitrocefin hydrolysis by TEM-1 β-lactamase with increasing concentrations of clavulanic acid (A), sulbactam (B), tazobactam (C), or 6β-HM-sulfone (D).

3.3. ESI-MS, intermediates, and mechanism: studies with 6β-HM-sulfone using purified TEM-1 and PDC-3 β-lactamases

Highly purified samples of TEM-1 and PDC-3 were used to characterize the intermediates of inhibition by 6β-HM-sulfone. Typical experiments with sulfones and β-lactamases using mass spectrometry suggest a multi-step pathway towards inactivation with several intermediates (possible formation of an imine, enamine (cis and/or trans), as well as inhibitor fragmentation) [24,25].

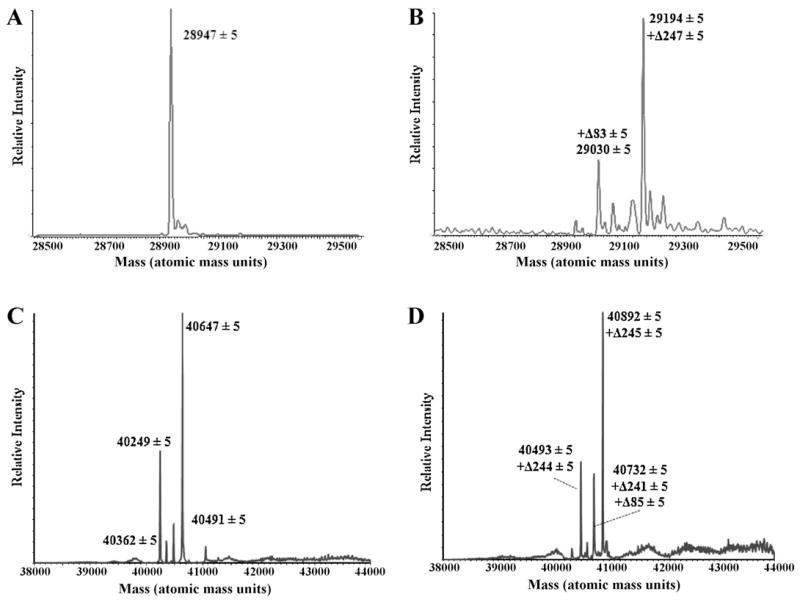

In these studies, TEM-1 reacted with 6β-HM-sulfone revealed the production of two covalent adducts, the most abundant having Δm/z = +247 ± 5 Da and a less abundant adduct having Δm/ z = +82 ± 5 Da (Fig. 4A and B). As shown by the spectra of the apoenzyme, PDC-3 β-lactamase possessed a “ragged” N-terminus on mass spectrometry (Fig. 4C). Similar to TEM-1, the addition of 6β-HM-sulfone revealed the production of a 245 ± 5 Da adduct as well as a minor fragment having Δm/z = +85 ± 5 Da (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Mass spectra of TEM-1 alone (A) and with 6β-HM-sulfone (B). Mass spectra of PDC-3 alone (C) and with 6β-HM-sulfone (D).

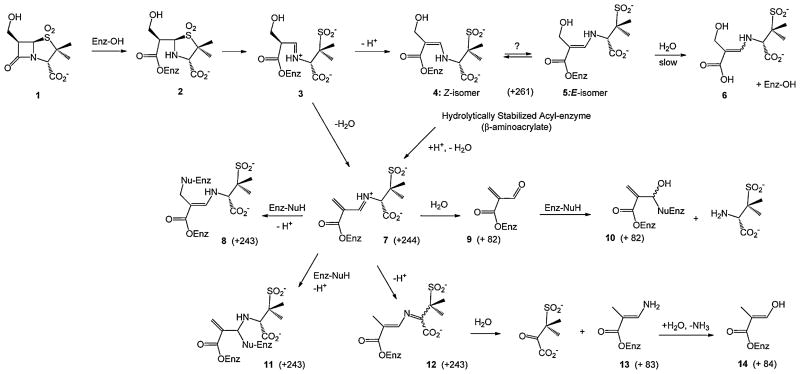

Scheme 3 depicts a mechanistically logical prediction of the interactions of 6β-HM-sulfone with these β-lactamases, based on established inhibitory pathways of the penicillin sulfones. Upon acylation of the active site serine, fragmentation of the dioxothiazolidine ring is predicted to occur producing a protonated imine 3. The proton alpha to the ester carbonyl (formerly attached to C6) is now rendered relatively acidic due to activation by both the adjacent carbonyl and protonated imine. The mass spectrometric results indicated that water is lost from the inhibitor subsequent to acylation of the enzyme, a process that may occur directly from 3 or through intermediates 4 and/or 5 (corresponding to the E and Z isomers of the β-aminoacrylates or enamines), which would be produced by tautomerization of the imine to the corresponding enamine. This elimination would produce intermediates 7, 8, 11, and/or 12 with appropriate mass to represent the major covalent fragment. As shown, subsequent hydrolysis of the imine of 7 and/ or 11 would produce covalent adducts 9, 10, 13, and/or 14, with appropriate mass to correspond to the minor fragment.

Scheme 3.

Proposed Mechanistic Interactions of 6β-HM-sulfone with the β-Lactamases.

3.4. Conclusions

In summary, the presence of the C6 hydroxymethyl group improves the efficiency of the inactivation process, relative to the C6 unsubstituted penicillin sulfones [26]. Mass spectrometric studies suggest that this may be due to rapid loss of water, subsequent to acylation of the enzyme, leading to intermediate 7, which has a number of mechanistic possibilities for production of a stabilized acyl-enzyme.

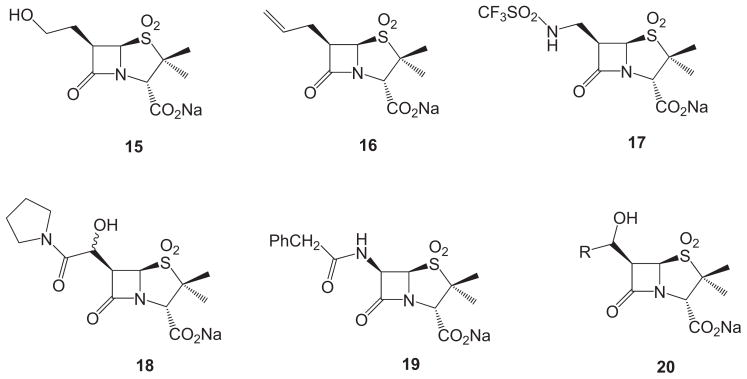

These mechanistic hypotheses are also consistent with the results of a recent study of the SARs of C6 substituted penicillin sulfones with TEM-1 and PDC-3. In that study, Nottingham et al. showed that, relative to the position of the hydroxyl group in 6β-HM-sulfone, the effect of moving the hydroxyl group further from C6, as in penicillin sulfone 15, or removal of the hydroxyl group entirely, as in penicillin sulfone 16, was loss of inhibitory activity, while, conversely, positioning the hydroxyl (or other heteroatom) so as to maintain the mechanistic possibility for elimination, as in penicillin sulfones 17 and 18, resulted in preservation of activity (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Representative C6 substituted penicillin sulfones.

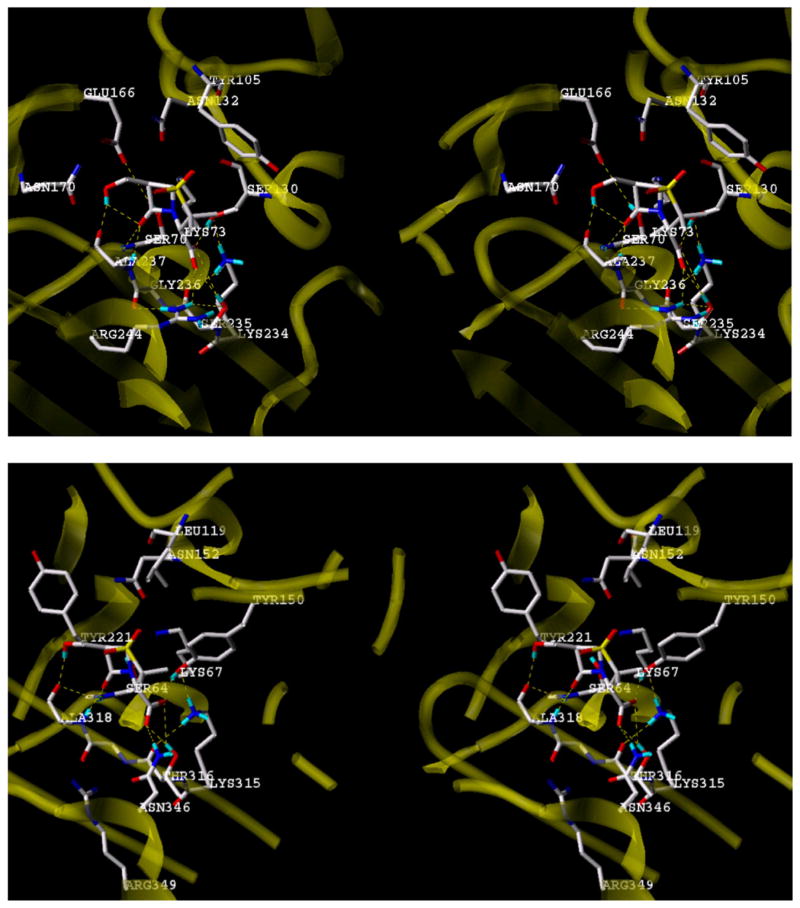

The hydroxymethyl group assists in recognition, by providing a hydrogen-bond donor to mimic the acylamino NH group of the substrate penam and cephem systems to the carbonyl oxygen of Ala237, as suggested through computationally assisted docking of the inhibitor into the TEM-1 site and illustrated in Fig. 6. Studies by Fisher et al. showed that sulfone inhibitors which closely resemble the penicillin substrates, such as penicillin G sulfone, 19, are poor β-lactamase inhibitors due to their ability to serve as excellent substrates of the respective β-lactamases, sometimes superior to the antibiotics themselves [27], thus further suggesting that the C6β hydroxymethyl group has a discreet mechanistic role in the inhibitory process.

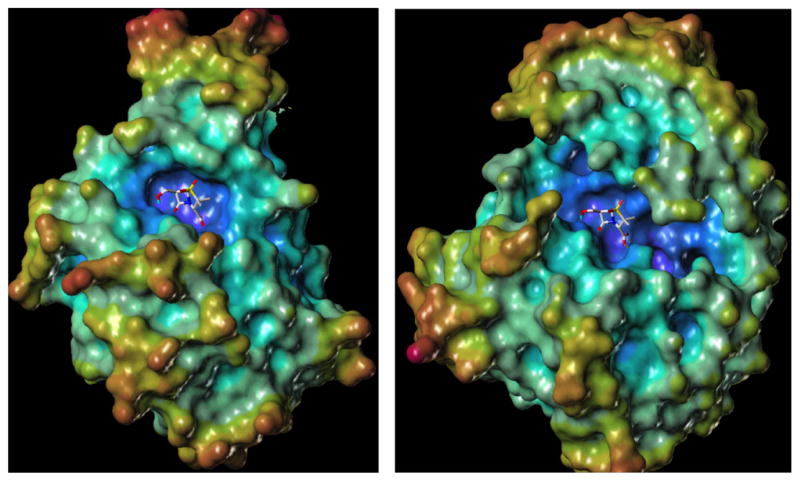

Fig. 6.

Stereoimages of computationally docked (FlexX) 6β-HM-sulfone in the active sites of the TEM-1 β-lactamase (top, PDB code 1ZG4) and AmpC β-lactamase (bottom, PDB code 1KE4) showing H-bonding interactions.

Lastly, it may be questioned as to why, of the 6β-(hydroxyalkyl)penicillin sulfone inhibitors (general structure 20 in Fig. 5) examined thus far, that the most active inhibitor has the least possible substituents (simple hydroxymethyl) on the C6 side chain (i.e. R = H in 20). As illustrated by Fig. 7, the active site pocket of TEM-1 is relatively constrained compared to the AmpC β-lactamase. One potential explanation is that the elimination of water requires a conformation possessing anti-coplanar geometry of the H–C–C–OH atoms (assuming elimination from 3), or alternatively, a conformational geometry where the C–OH bond is parallel to the π-system of enamines 4 and/or 5, as shown in Scheme 3. It is logical that, in the sterically confined active site cavity, that such antiperiplanar geometry would be achieved most readily with fewer substituents on the C6 side chain thus providing maximum opportunity for free rotation and less opportunities for interactions of the C6 side chain with active site substituents that might restrict rotation and hinder attainment of the ideal transition state geometry.

Fig. 7.

Image of computationally docked (FlexX) 6β-HM-sulfone in the active sites of the TEM-1 β-lactamase (left, PDB code 1ZG4) and AmpC β-lactamase (right, PDB code 1KE4) with electrostatic potential mapped onto the enzyme surface.

The deacylation half of the catalytic process of the AmpC/Class C β-lactamase mechanism had been the focus of numerous studies in recent years. In order to better understand the inhibitor interaction with the respective enzymes, computer-assisted modeling studies were undertaken which not only help to appreciate the importance of the C6 hydroxymethyl group in recognition, but also now leads to a new mechanism for the acylation half of the mechanism of AmpC hydrolysis.

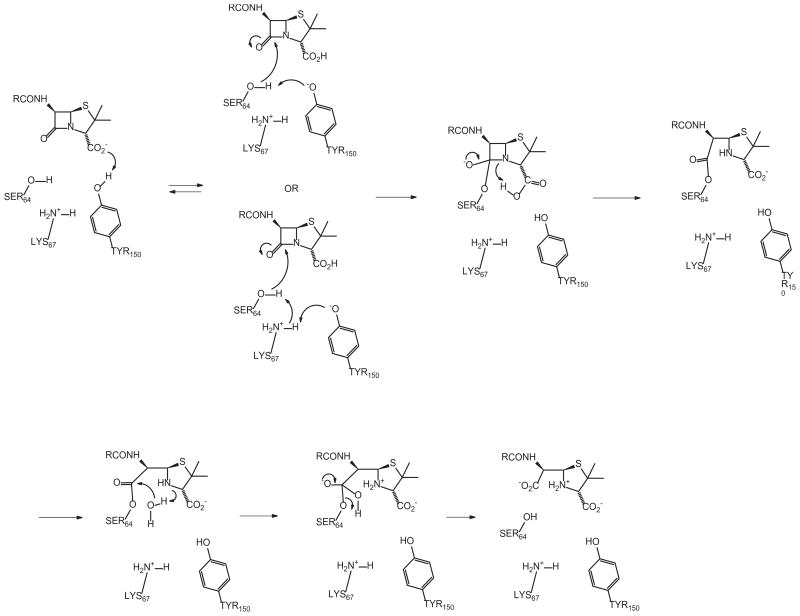

The docking studies showed that, in order to consistently achieve appropriate orientation of penicillin-derived inhibitors with the AmpC β-lactamase, a modification of the binding pocket was required. This involved adjusting the torsional angle of the C=C=O=H of Tyr150 so that the O=H bond of the phenol was oriented at an angle 55° from to the plane of the aromatic ring. The resultant docking results consistently implied a strong interaction between the C3 carboxylate of the inhibitor and the O–H of Tyr150. This computer-generated recognition data, together with the proximity of Tyr150 to the active site serine (Ser64), suggest that hydrolysis by AmpC may be a case of substrate-assisted catalysis, as shown in Scheme 4. The carboxylate of the antibiotic (or inhibitor) is the base responsible for deprotonation of Tyr150, which, in turn serves to either directly deprotonate Ser64, or does so through Lys67. (Both scenarios seem plausible from inspection of the models.) Collapse of the resultant tetrahedral intermediate, with assistance from a proton donation from the (now protonated) C3 carboxylic acid, then liberates the amine nitrogen which, in turn, serves as the base for deacylation, as indicated by the studies of Bulychev et al. and others [28,29].

Scheme 4.

Substrate-assisted catalysis of a penicillin by PDC-3. A similar mechanism is predicted to occur with 6β-HM sulfone and PDC-3; however in this case the acyl-enzyme is not catalyzed but instead follows the paths indicated in Scheme 2.

In conclusion, 6β-HM-sulfone is a potent inhibitor of TEM-1 and PDC-3. Mass spectroscopic data confirm that inactivation of the TEM-1 and PDC-3 β-lactamases proceeds through covalent attachment of the inhibitor to the β-lactamase and subsequent production of one or more hydrolytically stabilized acyl-enzyme intermediates through a mechanistic process which likely includes elimination of water from the initial acyl-enzyme. These data support the use of compounds like 6β-HM-sulfone as potential lead agents in the development of novel β-lactamase inhibitors.

Fig. 3.

Progressive inactivation of nitrocefin hydrolysis by PDC-3 β-lactamase with increasing concentrations of sulbactam (A), tazobactam (B), or 6β-HM-sulfone (C).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jean-Marie Frère (Université de Liège, Belgium) for the purified TEM-1 β-lactamase used in parts of this study. KMP-W is supported by the Veterans Affairs Career Development Program. PRC was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM54072). JDB is supported by grant N-0871 from the Robert A. Welch Foundation. RAB is supported by the Veterans Affairs Merit Review Program (RAB), the National Institutes of Health (RO1 AI063517-01), and Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centre VISN 10. Pfizer also supported this work.

References

- 1.Chain E. Chemical properties and structure of the penicillins. Endeavour. 1948;7:83. passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chain E. The chemistry of penicillin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1948;17:657–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.17.070148.003301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florey H. Penicillin other antibiotics. Adv Sci. 1948;4:281–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambler RP, Meadway RJ. Chemical structure of bacterial penicillinases. Nature. 1969;222:24–6. doi: 10.1038/222024a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush K, Jacoby GA, Medeiros AA. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–33. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambler RP. The structure of β-lactamases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1980;289:321–31. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drawz SM, Bonomo RA. Three decades of β-lactamase inhibitors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:160–201. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00037-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bush K, Jacoby GA. Updated functional classification of β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:969–76. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01009-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buynak JD. The discovery and development of modified penicillin- and cephalosporin-derived β-lactamase inhibitors. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:1951–64. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buynak JD, Rao AS, Doppalapudi VR, Adam G, Petersen PJ, Nidamarthy SD. The synthesis and evaluation of 6-alkylidene-2′β-substituted penam sulfones as β-lactamase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:1997–2002. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bou G, Santillana E, Sheri A, Beceiro A, Sampson JM, Kalp M, et al. Design, synthesis, and crystal structures of 6-alkylidene-2′-substituted penicillanic acid sulfones as potent inhibitors of Acinetobacter baumannii OXA-24 carbapenemase. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13320–31. doi: 10.1021/ja104092z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maveyraud L, Massova I, Birck C, Miyashita K, Samama J-P, Mobashery S. Crystal structure of 6α-(hydroxymethyl)penicillanate complexed to the TEM-1 β-lactamase from Escherichiacoli: evidence on themechanism ofactionofanovel inhibitor designed by a computer-aided process. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7435–40. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kellog MS, Hamanaka ES. Process for converting 6,6-disubstituted penicillanic acid derivatives to the 6-β-congeners. 4,397,783. USA: Patent. 1983

- 14.Buynak JD, Chen H, Vogeti L, Gadhachanda VR, Buchanan CA, Palzkill T, et al. Penicillin-derived inhibitors that simultaneously target both metallo- and serine-β-lactamases. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:1299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nottingham M, Bethel CR, Pagadala SR, Harry E, Pinto A, Lemons ZA, et al. Modifications of the C6-substituent of penicillin sulfones with the goal of improving inhibitor recognition and efficacy. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:387–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.10.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drawz SM, Taracila M, Caselli E, Prati F, Bonomo RA. Exploring sequence requirements for C(3)/C(4) carboxylate recognition in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa cephalosporinase: insights into plasticity of the AmpC β-lactamase. Protein Sci. 2011;20:941–58. doi: 10.1002/pro.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Approved Standard. 1. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; CLSI methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. CLSI M7-A1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.CLSI. Eighteen informational supplement. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2007. CLSI performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. CLSI M100-S17. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bush K, Singer SB. Biochemical characteristics of extended broad spectrum β-lactamases. Infection. 1989;17:429–33. doi: 10.1007/BF01645566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cartwright SJ, Waley SG. Purification of β-lactamases by affinity chromatography on phenylboronic acid-agarose. Biochem J. 1984;221:505–12. doi: 10.1042/bj2210505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bush K, Macalintal C, Rasmussen BA, Lee VJ, Yang Y. Kinetic interactions of tazobactam with β-lactamases from all major structural classes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:851–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.4.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powers RA, Shoichet BK. Structure-based approach for binding site identification on AmpC β-lactamase. J Med Chem. 2002;45:3222–34. doi: 10.1021/jm020002p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stec B, Holtz KM, Wojciechowski CL, Kantrowitz ER. Structure of the wild-type TEM-1 β-lactamase at 1.55 A and the mutant enzyme Ser70Ala at 2. 1 A suggest the mode of noncovalent catalysis for the mutant enzyme. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:1072–9. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905014356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Janota K, Tabei K, Huang N, Siegel MM, Lin YI, et al. Mechanism of inhibition of the class A β-lactamases PC1 and TEM-1 by tazobactam Observation of reaction products by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26674–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuzin AP, Nukaga M, Nukaga Y, Hujer A, Bonomo RA, Knox JR. Inhibition of the SHV-1 β-lactamase by sulfones: crystallographic observation of two reaction intermediates with tazobactam. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1861–6. doi: 10.1021/bi0022745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bitha P, Li Z, Francisco GD, Rasmussen BA, Lin YI. 6-(1-Hydroxyalkyl)penam sulfone derivatives as inhibitors of class A and class C β-lactamases I. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:991–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher J, Charnas RL, Bradley SM, Knowles JR. Inactivation of the RTEM β-lactamase from Escherichia coli. Interaction of penam sulfones with enzyme. Biochemistry. 1981;20:2726–31. doi: 10.1021/bi00513a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bulychev A, Massova I, Miyashita K, Mobashery S. Nuances of mechanisms and their implications for evolution of the versatile β-lactamase activity: from biosynthetic enzymes to drug resistance factors. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:7619–25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patera A, Blaszczak LC, Shoichet BK. Crystal structures of substrate and inhibitor complexes with AmpC β-lactamase: possible implications for substrate-assisted catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10504–12. [Google Scholar]