Abstract

Spatially addressable DNA nanostructures facilitate the self-assembly of heterogeneous elements with precisely controlled patterns. Here we organized discrete GOx/HRP enzyme pairs on specific DNA origami tiles with controlled inter-enzyme spacing and position. The distance between enzymes was systematically varied from 10 nm to 65 nm and the corresponding activities were evaluated. The study revealed two different distance dependent kinetic processes associated with the assembled enzyme pairs. Strongly enhanced activity was observed for those assemblies in which the enzymes were closely spaced, while the activity dropped dramatically for enzymes as little as 20 nm apart. Increasing the spacing further resulted in a much weaker distance dependence. Combined with diffusion modeling, the results suggest that Brownian diffusion of intermediates in solution governed the variations in activity for more distant enzyme pairs, while dimensionally-limited diffusion of intermediates across connected protein surfaces contributed to the enhancement in activity for closely spaced GOx/HRP assemblies. To further test the role of limited dimensional diffusion along protein surfaces, a noncatalytic protein bridge was inserted between GOx and HRP to connect their hydration shells. This resulted in substantially enhanced activity of the enzyme pair.

Cellular activities are directed by complex, multi-enzyme synthetic pathways that exhibit extraordinary yield and specificity. Many of these enzyme systems are spatially organized to facilitate efficient diffusion of intermediates from one protein to another by substrate channeling1, 2 and enzyme encapsulation.3 Understanding the effect of spatial organization on enzymatic activity in multi-enzyme systems is not only fundamentally interesting, but also important for translating biochemical pathways to noncellular environments. Despite the importance, there are very few methods available to systematically evaluate how spatial factors (e.g. position, orientation, enzyme ratio) influence enzymatic activity in multi-enzyme systems.

DNA nanotechnology has emerged as a reliable way to organize nanoscale systems due to the programmability of DNA hybridization and versatility of DNA-biomolecule conjugation strategies.4 The in vitro and in vivo assembly of several enzymatic networks organized on two-dimensional DNA and RNA arrays5 or simple DNA double helices6 has led to the enhancement of catalytic activities. Nevertheless, the nucleic acid scaffolds used in these studies are limited in their ability to study spatial parameters in multi-enzyme systems due to the lack of structural complexity. The development of the DNA origami method7 provides an addressable platform upon which to display nucleic acids or other ligands, permitting the precise patterning of multiple proteins or other elements.8 Here, we report a study of the distance-dependence for the activity of Glucose oxidase (GOx) - Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) cascade by assembling a single GOx/HRP pair on a discrete, rectangular DNA origami tile.

The DNA-directed co-assembly of GOx and HRP on DNA origami tiles is illustrated in Figure 1A. The DNA-conjugated enzymes, GOx-poly(T)22 (5′-HS-TTTTTTTTTTTTTTT TTTTTTT-3′) and HRP-poly(GGT)6 (5′-HS-TTGGTGGTGGTGGT GGTGGT-3′) were assembled on rectangular DNA origami tiles (~ 60 × 80 nm) by hybridizing with the corresponding complementary strands displayed on the surface of the origami scaffolds. Four different rectangular origami tiles9 were prepared with inter-enzyme probe distances (distance between two protein-binding sites) of 10 nm (S1), 20 nm (S2), 45 nm (S3) and 65 nm (S4). For Detailed sample preparations, please see Supplementary Figure S1–S6. To achieve high co-assembly yields of the GOx/HRP pairs, a 3-fold excess of enzymes were incubated with the DNA tiles (Supplementary Figure S7). The co-assembly of the GOx/HRP cascade was visualized using AFM imaging of DNA nanostructures. The presence of a protein results in a higher region than the surrounding surface of the origami tile (Supplementary Figure S8–9, S16–17). Most origami tiles were deposited on the mica surface with the protein decorated side facing up, likely due to the strong interaction (charge or stacking) of the opposite flat side with the mica surface.

Figure 1.

DNA nanostructure-directed co-assembly of GOx and HRP enzymes with control over inter-enzyme distances. (A) The assembly strategy and details of the GOx/HRP enzyme cascade. (B) Rectangular DNA origami tiles with assembled Gox/HRP pairs spacing from 10 nm to 65 nm. GOx/HRP co-assembly yields were determined from AFM images as shown in the bottom panel. Scale bar: 200 nm.

As shown in Figure 1B, high co-assembly yields of GOx/HRP pairs on DNA origami tiles were achieved for longer inter-enzyme distances, with ~ 95% for S3 (45 nm) and ~ 93% for S4 (65 nm). For shorter distances, the co-assembly of GOx/HRP pairs was less efficient due to the steric hindrance between two nearby enzymes, with ~ 45% for S1 (10 nm) and ~ 77% for S2 (20 nm). To rule out any nonspecific absorption of the enzymes to the tile surfaces, a control experiment was performed where tiles without any nucleic acid probes (C1) were incubated with DNA modified GOx and HRP, and no binding of the enzymes to the tiles was observed. The activities of the enzyme complexes, containing all components of GOx/HRP co-assembled on DNA tiles, unbound enzymes and free DNA tiles were measured in the presence of substrates glucose and ABTS2− by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 410 nm (Figure 2A). The S1 (10 nm) tile solution exhibited the highest enzyme activity, which was more than 2 times greater than the activity of the S2 (20 nm) tile solution (Figure 2B), even though the co-assembly yield of GOx/HRP pairs was significantly lower for S1 tiles. Increasing the distance between GOx and HRP from 20 nm to 65 nm resulted in a small decrease in the raw enzyme activity (~ 10%). A similar distance-dependent trend in activity was also observed in additional inter-enzyme distance-dependence studies using a different attachment scheme (Supplementary Figure S10). All samples containing assembled GOx/HRP tiles exhibited higher activities than unassembled enzyme controls, demonstrating how arranging the enzymes in close proximity results in enhanced activity. Further, the control solutions (with free enzymes and unbound DNA tiles) had similar activities as free enzymes without any DNA nanostructures, confirming that a DNA-nanostructure environment does not affect enzyme activity under the conditions used.

Figure 2.

Spacing distance-dependent effect of assembled GOx/HRP pairs as illustrated by (A) plots of product concentration vs. time for various nanostructured and free enzyme samples and (B) enhancment of the activity of the enzyme pairs on DNA nanostructures compared to free enzyme in solution. Both the raw activity (uncorrected for the yield of the completely assembed nanostructures) and yield-corrected activity are shown. The activity correction for assembly yields was performed using eq.(1).

| (1) |

Equation 1 was used to adjust the activities to account for the differences in yields of co-assembled enzymes. In equation 1, the raw activity (Araw) consists of contributions from both assembled GOx/HRP cascades (Aassem) and unassembled enzyme (Aunassem), where Yassem is the co-assembly yield of GOx/HRP pairs on the origami tiles. Because a 3:1 ratio of enzymes to origami tiles was used for the assembly, the percentage of assembled enzymes was , while the percentage of unassembled enzymes was . The resulting calibrated activities are presented in Figure 2B. The largest enhancement in activity was observed for enzymes with 10 nm spacing, which was more than 15 times higher than the corresponding control. A sharp decrease in cascade activity occurred as the inter-enzyme distance was increased from 10 nm to 20 nm, followed by a slow and gradual decrease in activity as the distance was further increased to 65 nm.

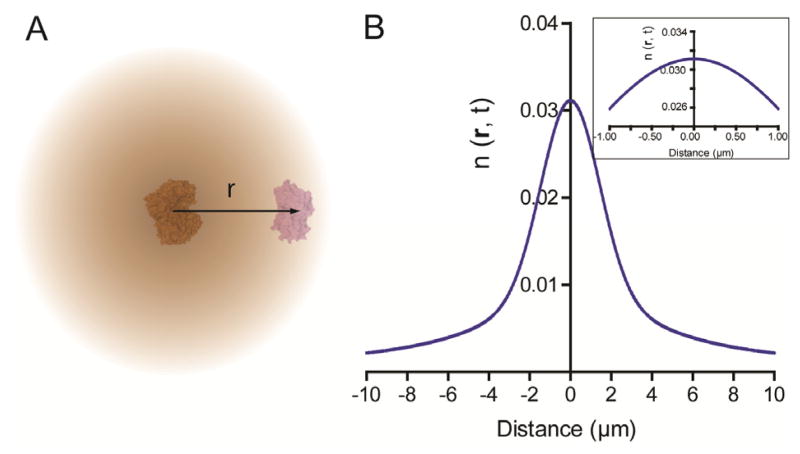

For a GOx/HRP cascade, effective transfer of the intermediate H2O2 between the enzymes is essential to the cascade activity (Figure 3A). Here, we use Brownian motion to simulate the distance-dependent, three-dimensional (3D) diffusion of H2O2 between enzymes as described by Equation 2, where n(r,t) is the concentration of H2O2 at a distance r from the initial position, D is the diffusion coefficient, and t is the diffusion time.10 GOx is assumed to generate H2O2 at a constant rate, kcat. Equation 3 describes the convolution function of Brownian motion of H2O2 with a constant catalytic rate for a GOx/HRP pair in the given time t, where τ is the average time between GOx turnovers (1/kcat). Figure 3B shows the simulation result using the following parameters: D = 1000 μm2/s for H2O2, 11kcat = 300 s−1 for GOx (Supplementary Figure S11) and t = 1 second. Due to the rapid diffusion of H2O2 in water, the concentration of H2O2 drops off only slightly within a few hundred nanometers of GOx. If one assumes that the activity is linear with substrate concentration, this simulation result agrees with the observation that assembled GOx/HRP cascades exhibit only small variations in activity for inter-enzyme distances between 20 nm and 65 nm. For a 1 nM solution of unassembled enzymes, the average spacing between proteins is ~ 1.2 μm, where the H2O2 concentration is ~ 60% of the initial position in the simulation. This result is consistent with the limited activity enhancement (less than two fold) for distantly-spaced GOx/HRP pairs (e.g. 45-nm or 65 nm) compared to unassembled enzymes in Figure 2. Further, if the intermediate transfer between distantly-spaced enzymes is dominated by Brownian motion, diluting the sample will result in a decreased H2O2 concentration for free HRP, while the H2O2 concentration near HRP in the assembled complexes remains nearly constant. Thus greater activity enhancement will be observed for assembled GOx/HRP pairs relative to the free enzymes under these conditions. This concentration-dependent enhancement was confirmed by performing the assay at a range of GOx/HRP concentrations (Supplementary Figure S12).

Figure 3.

Model of H2O2 diffusion in a single GOx/HRP pair. (A) Simplified illustration of the distance-dependent (r) H2O2 concentration gradient resulting from 3D Brownian diffusion. (B) Simulated H2O2 concentration gradient as a function of distance between GOx and HRP using eq.(3) with the following parameters: diffusion coefficient ~ 1000 μm2/s; kcat (GOx) ~ 300 s−1 and the integration time ~ 1 second.

| (2) |

| (3) |

While the Brownian diffusion model is consistent with the inter-enzyme distance dependence of the activity at distances greater than 20 nm, the strong activity enhancement for GOx/HRP pairs spaced 10 nm apart cannot be explained by this model. Apparently, the transfer of H2O2 between closely-spaced enzymes is governed by a different mechanism than that for more distantly spaced enzymes. Since both GOx and HRP are randomly oriented on the DNA origami tiles, it is unlikely that the active sites of GOx and HRP are perfectly aligned to allow the direct transfer of H2O2 between active sites. It seems more likely that when GOx and HRP are spaced in very close proximity, the two protein surfaces become essentially connected with one another, as demonstrated by AFM imaging of S1 tiles for 10 nm inter-enzyme spacing (Figure 1B). One possibility is that under these circumstances H2O2 does not generally escape into the bulk solution but instead transfers from GOx to HRP along their mutual, connected protein surface, providing a limited dimensional diffusion mechanism that dominates over three dimensional diffusion when the two enzymes are essentially in contact. In support of this concept, it is known that water molecules are translationally and rotationally constrained in the hydration layer around a protein, relative to bulk solution, due to hydrogen bonding and coulombic interactions with the protein.12 Some simulation results have suggested that H2O2 also has an affinity for protein surfaces resulting in an even longer residence time in the hydration layer near the protein than water.13 In addition, dimensionally-limited diffusion has been observed in a number of biochemical systems, resulting in decreased times for diffusion of a substrate or ligand to its point of action.1 Examples include linear diffusion of nuclease or transcription factors along DNA14 and the surface-attached ‘lipoyl swing arm’ in the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex.2

If the enhancement seen in Figure 2 at 10 nm inter-enzyme distance is in fact due to dimensionally restricted diffusion along protein surfaces, it should be possible to enhance the activity observed at longer inter-enzyme distances by placing a protein bridge between the enzymes. To test this, we designed a ‘bridge-based’ cascade in which a non-catalytic protein was inserted between GOx and HRP, in order to connect the protein hydration shells and facilitate the surface-limit diffusion of H2O2. As shown in Figure 4A, a GOx/HRP pair was first assembled on a DNA origami tile with a 30 nm inter-enzyme distance. Next, a non-catalytic protein, either neutravidin (NTV) or streptavidin (STV)-conjugated β-galactosidase (β-Gal), was inserted between the enzymes. As shown in Figure 4B, assembled GOx/HRP pairs with a β-Gal bridge exhibited ~ 42 ± 4% higher raw activity than control assemblies without the bridge. For this preparation, the yield of assemblies with all three components (GOx, HRP and the bridge) was ~ 38%. Assembled GOx/HRP pairs with a NTV bridge showed ~ 20 ± 4% enhancement in raw activity compared to the control sample, at ~ 50% co-assembly yield (Supplementary Figure S13, S18). STV conjugated β-Gal and NTV in solution did not affect GOx/HRP activities (Supplementary Figure S14). With a larger protein diameter (~16 nm), β-Gal can fill the space between GOx and HRP more completely than NTV (~ 6 nm diameter), resulting in a more enhanced activity for the β-Gal bridge even with a lower co-assembly yield (Supplementary Figure S15). This result supports the notion that surface-limited diffusion of H2O2 between closely-spaced enzymes is responsible for the increase in cascade activity beyond what is possible by three-dimensional Brownian diffusion.

Figure 4.

Surface-limited H2O2 diffusion induced by a protein bridge. (A) The design of an assembled GOx/HRP pair with a protein bridge used to connect the hydration surfaces of GOx and HRP. (B) Enhancement in the activity of assembled GOx/HRP pairs with β-Gal and NTV bridges compared to unbridged GOx/HRP pairs. AFM images of GOx/HRP pairs with and without protein bridges were used to estimate the co-assembly yield. Scale bar: 200 nm.

In conclusion, we have systematically studied the activity of a GOx/HRP cascade spatially organized on a DNA nanostructure as a function of inter-enzyme distance. The intermediate transfer of H2O2 between enzymes was found to follow the surface-limited diffusion for closely-spaced enzymes, while 3D Brownian diffusion dominated H2O2 transfer between enzymes with larger spacing distances. These studies imply that the strong activity enhancement observed for assembled enzyme cascades is not simply achieved by reducing the inter-enzyme distance to reach high local molecule concentration, but also results from restricting diffusion of intermediates to a two-dimensional surface connecting the enzymes. While it is possible that some co-assembled GOx/HRP pairs are aligned in such a way that their active sites are juxtaposed, facilitating H2O2 transfer between enzyme pockets, there was no specific attempt to orient the enzymes in this study. In the future, it will be important to study the effect of enzyme orientation on the activity of assembled enzyme complexes as well.15 With the further development of DNA-protein attachment chemistry through site-specific conjugation or ligand capture,16 it should be possible to start to direct the flow of substrate molecules between active sites using some of the concepts and tools discussed above.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the funding supports from the Army Research Office, National Science Foundation, Office of Naval Research, National Institute of Health, Department of Energy and Sloan Foundation. The authors would like to thank Jeanette Nangreave for the help in editing the manuscript. The authors are grateful to Nils Walter, Alex Johnson-Buck, Nicole Michelotti and Tristan Tabouillot from University of Michigan for insightful discussions and suggestions.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Detailed methods, Supplementary Figures and Tables. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/

References

- 1.Miles EW, Rhee S, Davies DR. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perham RN. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:961. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Srere PA, Mosbach K. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1974;28:61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.28.100174.000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yeates TO, Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC, Shively JM. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:681. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Lin C, Liu Y, Yan H. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1663. doi: 10.1021/bi802324w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Seeman NC. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:65. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-102244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Voigt NV, Torring T, Rotaru A, Jacobsen MF, Ravnsbaek JB, Subramani R, Mamdouh W, Kjems J, Mokhir A, Besenbacher F, Gothelf KV. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5:200. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Wilner OI, Weizmann Y, Gill R, Lioubashevski O, Freeman R, Willner I. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:249. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Delebecque CJ, Lindner AB, Silver PA, Aldaye FA. Science. 2011;333:470. doi: 10.1126/science.1206938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Niemeyer CM, Koehler J, Wuerdemann C. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:242. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020301)3:2/3<242::AID-CBIC242>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Erkelenz M, Kuo CH, Niemeyer CM. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16111. doi: 10.1021/ja204993s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothemund PWK. Nature. 2006;440:297. doi: 10.1038/nature04586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinheiro AV, Han D, Shih WM, Yan H. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:763. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ke Y, Lindsay S, Chang Y, Liu Y, Yan H. Science. 2008;319:180. doi: 10.1126/science.1150082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pathria RK. Statistical Mechanics. 2. Butterworth-Heinemann; Woburn: 1996. pp. 459–464. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Henzler T, Steudle E. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:2053. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.353.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stewart PS. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1485. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.5.1485-1491.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagchi B. Chem Rev. 2005;105:3197. doi: 10.1021/cr020661+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Chung YH, Xia J, Margulis CJ. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:13336. doi: 10.1021/jp075251+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Domínguez L, Sosa-Peinado A, Hansberg W. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;500:82. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Gorman J, Greene EC. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:768. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jeltsch A, Pingoud A. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2160. doi: 10.1021/bi9719206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mansson MO, Siegbahn N, Mosbach K. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:1487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.6.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Niemeyer CM. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:1200. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Saccà B, Meyer R, Erkelenz M, Kiko K, Arndt A, Schroeder H, Rabe KS, Niemeyer CM. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:9378. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.