Abstract

Many membrane proteins are involved in the transport of nutrients in plants. While the import of amino acids into plant cells is, in principle, well understood, their export has been insufficiently described. Here, we present the identification and characterization of the membrane protein Siliques Are Red1 (SIAR1) from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) that is able to translocate amino acids bidirectionally into as well as out of the cell. Analyses in yeast and oocytes suggest a SIAR1-mediated export of amino acids. In Arabidopsis, SIAR1 localizes to the plasma membrane and is expressed in the vascular tissue, in the pericycle, in stamen, and in the chalazal seed coat of ovules and developing seeds. Mutant alleles of SIAR1 accumulate anthocyanins as a symptom of reduced amino acid content in the early stages of silique development. Our data demonstrate that the SIAR1-mediated export of amino acids plays an important role in organic nitrogen allocation and particularly in amino acid homeostasis in developing siliques.

In multicellular organisms, transport proteins are indispensable for the controlled intercellular and intracellular exchange of nutrients and for an efficient supply to all tissues and organs. While the import of amino acids into cells has been described in detail, the molecular mechanism of amino acid efflux in plants is not well understood. However, amino acid distribution in plants includes apoplasmic transport steps that require import as well as export processes (Okumoto and Pilot, 2011); consequently, the presence of amino acid exporters has been postulated for a number of intercellular transport steps (Bush, 1993; Rentsch et al., 2007). Here, the terms export and efflux are used to describe the transport of amino acids from the cytosol into the apoplasmic space. In roots, for example, radially transported solutes have to be imported into endodermis cells, but prior to entering the xylem, the solutes need to be exported into the apoplasm to reach the tracheary elements and the transpiration stream. Another example where the export of solutes and amino acids is necessary are the symplasmically isolated developing pollen grains (Lee and Tegeder, 2004). Also, interfaces between plants and other organisms, like symbiotic or pathogenic relationships, require regulated import and export of solutes (Lodwig et al., 2003; Lalonde et al., 2004). In general, apoplasmic borders occur between the different generations of a plant. It was shown that the megaspore mother cell and the developing female gametophyte and later the filial part of the seed, including the embryo, are symplasmically isolated (Stadler et al., 2005; Werner et al., 2011). Developing seeds are strong sink organs and need to be supplied with large amounts of assimilates. Nutrients arriving through the vasculature of the funiculus are delivered into the chalazal region of ovules and developing seeds. The import of amino acids into the developing seed is at least in part mediated by members of the Amino Acid Permease (AAP) family, which are described as unidirectional, proton-coupled amino acid symporters (Hirner et al., 1998; Schmidt et al., 2007; Sanders et al., 2009). Nevertheless, proteins catalyzing the export steps at these specific sites are still unknown.

In contrast to the limited amount of information on plant amino acid export systems, several transport systems have been characterized in yeast, animals, and human. For example, in mammals, amino acids can be directly exported by an ion-independent uniport at the plasma membrane, as has been shown for asc-type amino acid transporter-1, the light chain of a heteromeric transport system. This transport system is composed of different light chains and of the heavy chain 4F2hc (4F2 heavy chain; Fukasawa et al., 2000; Meier et al., 2002; Bröer, 2008). The light chain mediates transport and determines substrate specificity, whereas the heavy chain regulates activity and is responsible for the trafficking of the complex to the membrane (Chillarón et al., 2001; Bröer, 2008). One example of plant proteins involved in the amino acid export are members of the GLUTAMINE DUMPER (GDU) family from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Pilot et al., 2004; Pratelli et al., 2010). When overexpressed, GDU1 leads to an accumulation of Gln crystals at the hydathodes (Pilot et al., 2004). As the GDU proteins do not show any transport activity themselves, the underlying mechanism that causes this secretion remains unclear; however, GDU1 might act indirectly by stimulating the export by as yet unidentified amino acid facilitators (Pratelli et al., 2010). To date, the only plant protein identified to perform an export of amino acids out of a cell is BAT1, the bidirectional amino acid transporter 1. When expressed in yeast, a bidirectional, facilitated transport activity was determined (Dündar and Bush, 2009). BAT1 localizes to the vascular tissue and could be involved in phloem unloading (Dündar, 2009; Dündar and Bush, 2009). However, additional amino acid efflux proteins should be present, which catalyze various essential efflux steps and thereby act as counterparts to the numerous characterized import proteins.

We describe Siliques Are Red1 (SIAR1) as a novel type of amino acid transporter in Arabidopsis. SIAR1 belongs to the Medicago truncatula NODULIN21 (MtN21) gene family, with over 40 members in Arabidopsis. The MtN21 family is part of the Plant Drug/Metabolite Exporter family, which is located within the Drug/Metabolite Transporter superfamily (Jack et al., 2001). The only other member of the MtN21 family that is characterized to date is Walls Are Thin1 (WAT1) from Arabidopsis. It is involved in stem elongation and in secondary cell wall formation in fibers (Ranocha et al., 2010). wat1 mutants have a pleiotropic phenotype, including alterations in auxin and Trp metabolism (Ranocha et al., 2010).

Here, we show that SIAR1 catalyzes a bidirectional transport across the membrane and, thus, is also able to function as an amino acid exporter. SIAR1 is expressed at specific sites where the export of amino acids out of cells is essential. Mutant analysis revealed an important role for SIAR1 in the amino acid homeostasis of siliques and the supply of organic nitrogen to developing seeds.

RESULTS

Structure and Subgroups of the MtN21 Protein Family in Arabidopsis and Rice

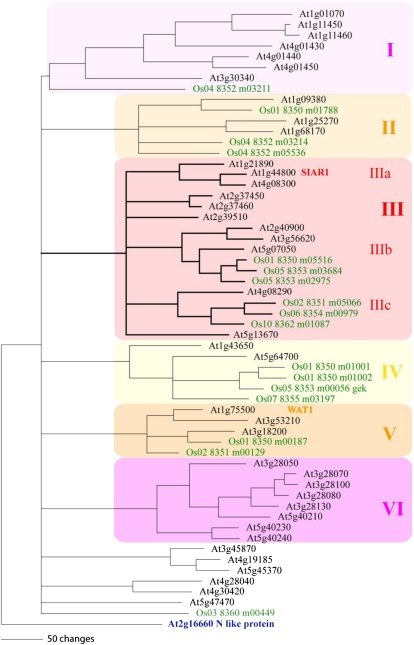

SIAR1 belongs to the plant-specific MtN21 family. The MtN21 protein family itself is part of the huge Drug/Metabolite Transporter superfamily that exists in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes (Jack et al., 2001). One of the prokaryotic members has been assigned to function in the efflux of metabolites that derived from the Cys biosynthesis pathway (Dassler et al., 2000). The MtN21 family consists of 44 members in Arabidopsis. Orthologs can be found in all higher plant species (e.g. in Medicago, rice [Oryza sativa], poplar [Populus spp.], and pine [Pinus spp.]). MtN21 family members are also present in mosses like Physcomitrella patens and Marchantia polymorpha. However, this family is not present in the unicellular organism Ostreococcus tauri, an early representative of the green lineage (Rodríguez-Ezpeleta et al., 2005), or in animals and fungi. Phylogenetic analysis with protein sequences from Arabidopsis and rice allowed the division of this family into six major groups, each of which can be separated from the other groups by more than 50 amino acid exchanges (Fig. 1). SIAR1 (At1g44800) belongs to group IIIa and has two closely related paralogs in Arabidopsis that are encoded by At1g21890 and At4g08300, but there are no direct orthologs in rice. WAT1 (At1g75500), the first described member of the family (Ranocha et al., 2010), is a distant homolog of SIAR1 and belongs to group V in the phylogram.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationship between SIAR1 and the related MtN21 family proteins from Arabidopsis and rice. The highly variable N- and C-terminal regions of the proteins were truncated, and the analysis was performed with the conserved regions of the proteins. The tree calculation was based on a multiple alignment generated by MegAlign. The phylogram was created by PAUP4.0b10 using the bootstrap algorithm running 1,000 replicates. As an outgroup, a nodulin-like protein (At2g16660) was used. The MtN21 proteins group in six major subfamilies, which are separated by more than 50 changes each. WAT1 (Ranocha et al., 2010) is located in group V; SIAR1 is located in subgroup IIIa.

Expression in Yeast and Oocytes Shows That SIAR1 Mediates Both Amino Acid Import and Export

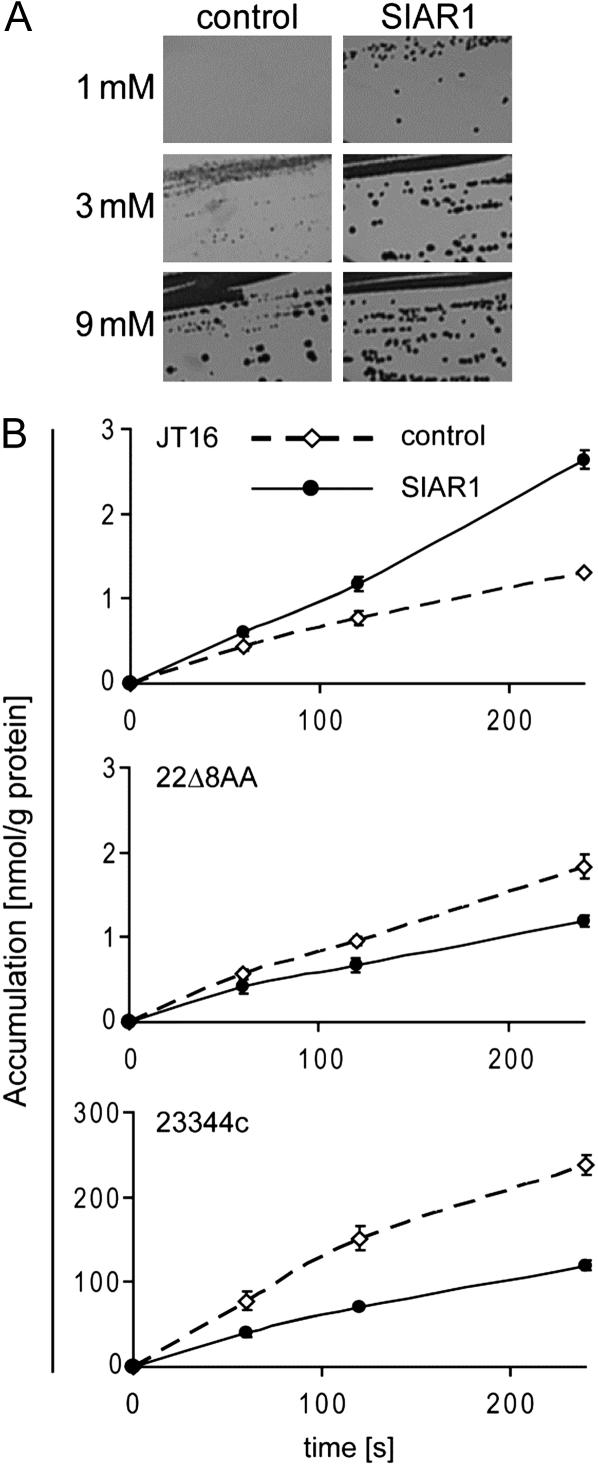

To test the ability of SIAR1 to transport His, the gene was expressed in the yeast strain JT16, which is deficient in the uptake and biosynthesis of His and, therefore, unable to grow well on His as a sole nitrogen source (Tanaka and Fink, 1985). After 6 d, the growth of SIAR1-transformed yeast cells was clearly visible on SC medium with 1 or 3 mm His. In contrast, the empty vector control cells displayed less growth, beginning to grow at concentrations of 3 mm His (Fig. 2A). To further support these complementation data, the direct uptake of radiolabeled [14C]His into yeast cells expressing SIAR1 was measured. The uptake activity was about 2- to 3-fold higher than the background activity determined in control cells (Fig. 2B), although other amino acid transporters (e.g. LYSINE HISTIDINE TRANSPORTER1 [LHT1]) enhance the transport rates 40- to 200-fold depending on the substrate (Hirner et al., 2006). We next expressed SIAR1 in two other yeast strains, 22Δ8AA, with multiple deletions in endogenous amino acid importers, and 23344c, a wild-type yeast strain that contains all endogenous yeast amino acid transporters. Surprisingly, uptake activity measurements with SIAR1-expressing cells led to a reduction of His accumulation in comparison with the control cells in both yeast strains (Fig. 2B). The SIAR1-dependent reduced net accumulation could be explained by a concomitant export of intracellular His, suggesting that SIAR1 is able to catalyze the efflux of His in this experiment.

Figure 2.

Complementation of JT16 and His transport by SIAR1 in different yeast strains. A, Yeast growth on synthetic complete medium with different His concentrations (1, 3, or 9 mm). The control is shown in the left panels, and SIAR1-expressing cells are shown in the right panels. B, Uptake of 14C-labeled His in JT16, 22Δ8AA, and 23344c. Uptake of His was monitored over 4 min, and samples were taken at the indicated time points. The concentration of radiolabeled His was 10 μm, and the measurements were performed at pH 4.5. Dashed lines indicate control cells, and continuous lines indicate SIAR1-expressing cells. n = 6 ± se.

To test whether SIAR1-dependent transport is restricted to His, we analyzed the uptake activity for Gln and Asp in 22Δ8AA and 23344c yeast cells (Fig. 3A). Again, the results obtained were strain dependent. In the 22Δ8AA strain, which has low endogenous transport capacity, SIAR1 enhanced Gln uptake at the concentration tested. In contrast, in 23344c with high endogenous amino acid transport rates, SIAR1 reduced the net uptake rate of Gln (Fig. 3A). Because the cytosolic Gln levels are unknown, it is difficult to judge whether this effect is dependent on the intracellular amino acid concentration. For the acidic amino acid Asp, a SIAR1-mediated uptake was determined in both yeast strains (Fig. 3A). Another indication that SIAR1 acts as an importer was found in Xenopus laevis oocytes for Gln and Asp (Fig. 3B). In comparison with water-injected control cells, slightly more Gln and Asp accumulated in SIAR1-expressing cells.

Figure 3.

Transport measurements in yeast and oocytes. A, SIAR1-mediated transport of Gln and Asp in 22Δ8AA and 23344c. The accumulation of the indicated amino acids in the yeast strains 22Δ8AA and 23344c was monitored over 4 min, and samples were taken at the indicated time points. The concentration of radiolabeled amino acid was 10 μm, and the measurements were performed at pH 4.5. Dashed lines indicate control cells, and continuous lines indicate SIAR1-expressing cells. n = 6 ± se. B, Uptake of radiolabeled amino acids into Xenopus oocytes. The uptake of 14C-labeled Gln and Asp into oocytes injected with SIAR1 complementary RNA is shown. Water-injected oocytes were used as a control. Amino acid at 1 mm was supplied as a substrate, of which 0.44 μm was radioactively labeled. The measurements were performed in Ringer’s solution at pH 5.0. The cpm are depicted for the accumulation of each amino acid after 15 min of incubation. n = 5 ± se. A t test was performed: * P < 0.05. C, Comparison of the amino acid concentrations in the supernatant of control cells and SIAR1-expressing yeast cells. Yeast cells of the strain 22Δ8AA were grown in minimal medium at the indicated pH values to an optical density of 2.0. The supernatant was analyzed by HPLC. n = 3, and error bars represent sd. Cit, Citrulline; n.d., not detectable. A t test was performed: * P < 0.01, ** P < 0.001. D, Gln efflux measurements in oocytes. Oocytes from two different frogs were injected with 50 nL of radioactively labeled Gln to a final concentration of 1 mm. The experiment was performed in ND96 solution at pH 7.5. After 10 and 20 min, five control and five SIAR1-expressing cells were washed and the radioactivity was measured. The control oocytes at 10 min were set as 100%; the other signals were referred to the control cells and are given as relative counts. n = 5 ± sd. A t test was performed: * P < 0.01.

Further support for the transport activity of SIAR1 was gained from the analysis of yeast cell supernatants. Control cells and SIAR1-expressing cells of the strain 22Δ8AA were grown in amino acid-free minimal medium with ammonium sulfate as the sole nitrogen source at two different pH values. Analyses of the supernatant revealed elevated amino acid levels in the medium of SIAR1-expressing cells (Fig. 3B), which likely represents exuded amino acids. Gln and Val concentrations showed the most pronounced differences, with the Gln levels being about 100-fold higher in the supernatant of SIAR1-expressing cells compared with the control. His was not detectable in the supernatant, but citrulline and Ile were present in much higher concentrations. Because the transport assays had directly shown an increased Gln transport capacity in the 22Δ8AA strain by SIAR1 (Fig. 3A), it is likely that the high Gln content in the supernatant reflects export under the chosen experimental conditions. However, as the activity of endogenous yeast transporters may be affected by the overexpression of SIAR1, it cannot be completely ruled out that the reduced accumulation is due to an impaired reuptake of amino acids.

To provide further evidence for Gln export and to avoid the possible interference with yeast metabolism or endogenous transport systems, we injected radioactively labeled Gln directly into control oocytes and SIAR1-expressing oocytes. After 10 min of incubation, no significant difference was detected (Fig. 3D), but after 20 min, the SIAR1-expressing cells contained significantly lower amounts of the radioactive Gln compared with control cells (Fig. 3D), which can be explained by an export of the amino acid. The fact that the export is not visible after 10 min is probably due to the central yolk in oocytes, into which the labeled substrate was most probably injected. The substrate has to diffuse to the plasma membrane prior to being available for export by SIAR1. Given that oocytes contain few endogenous transporters at their plasma membrane, the chance of any influence of SIAR1 on endogenous oocyte transporters is considerably low (Miller and Zhou, 2000). Taken together, the capacity of SIAR1 to transport Gln in both directions could be confirmed in oocytes. Although the transport mode remains unclear, the yeast and oocyte transport measurements provide evidence for a bidirectional amino acid transport function of SIAR1.

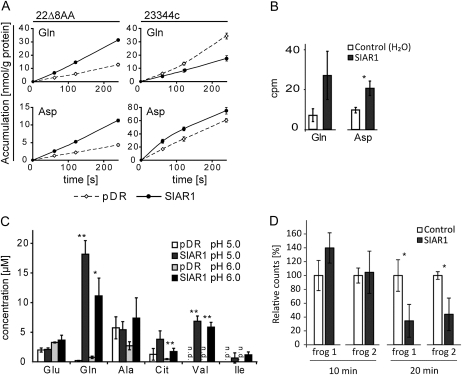

SIAR1 Is Expressed in Vascular Tissue and Reproductive Organs

RNA gel-blot analysis showed that SIAR1 is ubiquitously expressed. These data are in agreement with available microarray data (Schmid et al., 2005). The expression levels in sink leaves, cauline leaves, and flowers were lower, whereas the signal intensities detected in roots, stems, source leaves, siliques, and seedlings were higher (Fig. 4A). To analyze the expression pattern in more detail, promoter-reporter (GUS) studies in transgenic PSIAR1:GUS Arabidopsis lines were performed. Histochemical analyses demonstrated that the SIAR1 promoter drives expression in nearly all organs (Fig. 4, B and C). In source leaves, the promoter activity could be detected in the vascular bundles of the leaves, with a strong staining of the primary vein (Fig. 4, C–E). In sink or cauline leaves, weaker GUS activity was visible, which is in accordance with the northern-blot results and microarray data. Furthermore, a strong staining in the roots and a weaker staining in the stem and the inflorescence were detectable (Fig. 4, B and C). In reproductive organs, GUS activity could be observed in the siliques at the peduncle and in the funiculi (Fig. 4G). In stamen, the vascular tissue of the filament was stained and a very strong signal was visible at the connective tissue (Fig. 4, H and I).

Figure 4.

Organ- and tissue-specific expression of SIAR1. A, Expression was analyzed by RNA gel-blot hybridization by using 32P-labeled full-length SIAR1 cDNA as a probe. Seedlings and the indicated organs of adult Arabidopsis plants were probed. The RNA is shown as a loading control on an ethidium bromide-stained gel. B to I, Reporter gene analysis of PSIAR1:GUS plants. B and C, Adult plants. D, Closeup of a source leaf. E, Cross-section of a source leaf. F, Unopened bud. G, Young silique. H, Flower. I, Stamen.

SIAR1 Localizes to the Plasma Membrane in Developing Seeds and in the Pericycle

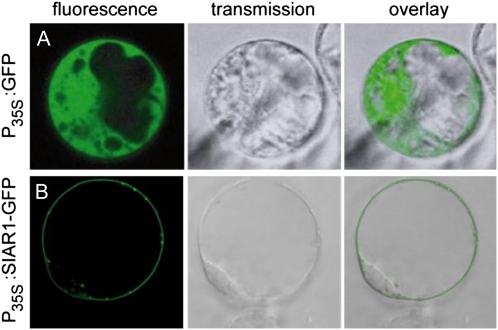

All members of the nodulin MtN21 family are predicted to be membrane proteins with 10 to 12 transmembrane domains (consensus predictions of the ARAMEMNON database, topology detail [Schwacke et al., 2003]). We analyzed the subcellular localization of SIAR1-GFP fusion proteins in Arabidopsis protoplasts. SIAR1-GFP could be clearly localized at the plasma membrane and weakly in some speckles in the cytosol (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Subcellular localization of P35S:SIAR1-GFP in Arabidopsis protoplasts. A, Free GFP fluorescence as a control. B, SIAR1-GFP fluorescence.

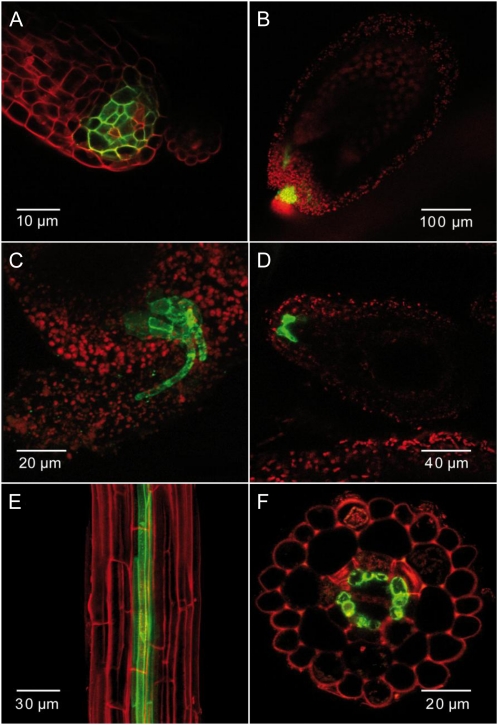

To analyze the cellular and tissue-specific localization of SIAR1 in intact plants, we transformed Arabidopsis plants with a construct that comprises the genomic locus with the full-length open reading frame (ORF) fused to GFP and expressed it under the control of the endogenous SIAR1 promoter. In general, the localization of the GFP signal was consistent with the histochemical GUS studies. The fluorescence of SIAR1-GFP could be detected in almost all organs and was visible in leaves, especially in the source leaves (data not shown), and in the stamen at the connection site between filament and anthers, comparable to the histochemical analysis. Signals could also be observed in ovules and developing seeds. Here, the fluorescence was localized in the chalazal region in close proximity to the point of transition, where the end of the funiculus passes into the ovule or into the developing seed. Cells within this region might form a sort of “nutrient-unloading zone,” which is characterized by a strong expression of the SIAR1 fusion protein. Interestingly, in a few distinct cells at the center, no fluorescence was detectable (Fig. 6, A and B). The top view (Fig. 6D) shows that the region of SIAR1-GFP-expressing cells spread in a kidney-shaped manner over the plane of the integuments, which extends the nutrient unloading zone. In roots, the GFP fluorescence can be unambiguously localized to pericycle cells, which is the first cell layer of the central cylinder adjacent to the endodermis (Fig. 6, F and G). The pericycle is involved in the radial transport of nutrients into the central cylinder (Peterson and Enstone, 1996). Altogether, SIAR1 expression was detected in tissues that are involved in the transfer of nutrients.

Figure 6.

Tissue- and cell-specific localization of SIAR1. Localization studies using PSIAR1:SIAR1-GFP were performed with a confocal laser scanning microscope. A, Ovule, view of the transition zone between the funiculus and chalaza. B, Ovule, lateral view. C, Developing seed, globular stage. The funiculus with vascular tissue is visible along with the chalazal region. D, Developing seed, globular stage, top view. E, Lateral view of the root. F, Cross-section of a root. The GFP fluorescence is depicted in green, and propidium iodide staining is shown in red.

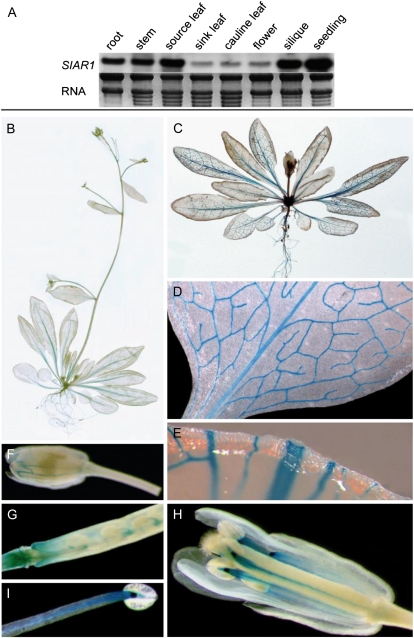

siar1 Mutants Display a Disturbed Amino Acid Homeostasis in Siliques

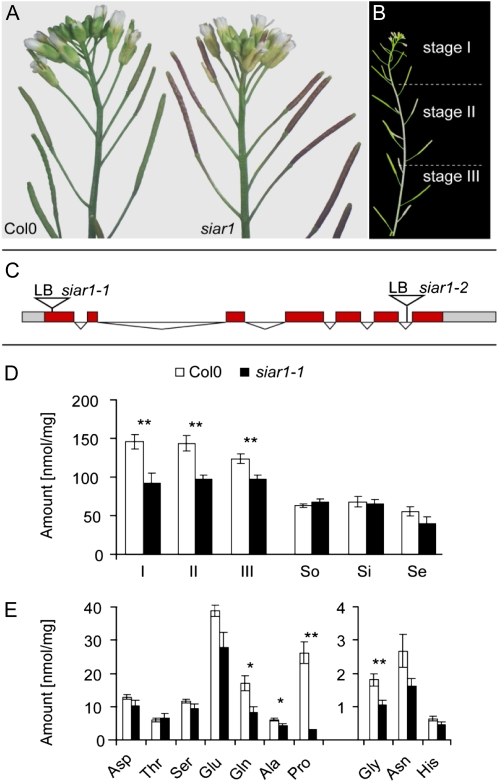

For SIAR1, two T-DNA insertion lines, siar1-1 (SALK_123331) and siar1-2 (SALK_074699), could be isolated by PCR genotyping (Fig. 7C). Homozygous insertion lines were analyzed for possible residual transcripts. For siar1-1, RNA gel-blot analysis with RNA from source leaves did not show any residual transcript (data not shown). Quantitative real-time (q)PCR revealed strongly reduced transcripts for both alleles: 25-fold reduction in the siar1-1 allele and 7-fold reduction in the siar1-2 allele compared with the wild type. Thus, the siar1-1 allele is a bona fide knockout, whereas siar1-2 is a knockdown allele.

Figure 7.

Phenotypes and changes of amino acid concentrations in siar1 mutants. A, Phenotypes of siar1 mutants. The top-most siliques of siar1-1 hyperaccumulate anthocyanins in comparison with the wild type. B, Definition of the three different stages of siliques, which were used for amino acid analysis. C, Schematic depiction of the T-DNA insertion sites in the SIAR1 locus; siar1-1, SALK_123331; siar1-2, SALK_074699. LB, Left border. D, Analyses of the free amino acid concentrations in the wild type and the siar1-1 mutant. The total amount of amino acid is given in nmol mg−1 dry weight. I, II, and III, Siliques of stages I, II, and III; Se, senescent leaves; Si, sink leaves; So, source leaves. E, Amounts of individual amino acids in siliques of stage I in nmol mg−1 dry weight. The error bars in D and E represent se. n = 6. A t test was performed: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

The analysis of plant growth on medium containing different nitrogenous compounds including individual amino acids as the sole nitrogen source did not show any obvious phenotypes, suggesting that SIAR1 is not involved in the acquisition of amino acids from the environment (data not shown). The youngest siliques of siar1 mutants (described here as stage I; Fig. 7B) display a red color (Fig. 7A). The phenotype occurs under constant light conditions, when a surplus of carbohydrates is available and the nitrogen supply is limited. The coloring is caused by the accumulation of anthocyanin, known as a general stress symptom under nitrogen depletion (Diaz et al., 2006; Lillo et al., 2008). The anthocyanin was identified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis as a cyanidin derivative that is similar in its mass fragmentation pattern to 3-O-[2-O(2-O-(sinapoyl)-β-d-xylopyranosyl)-6-O-(4-O-(β-d-glucopyranosyl)-p-coumaroyl-β-d-glucopyranoside]5-O-[6-O-(malonyl)β-d-glucopyranoside]. This cyanidin derivative is described as the major anthocyanin in Arabidopsis (Bloor and Abrahams, 2002; Tohge et al., 2005). It was also identified by nontargeted metabolomic LC-MS analysis between the wild type and siar1 mutants as a marker that is significantly increased in siar1 compared with the wild type. siar1-2 is the weaker knockdown line, and its anthocyanin accumulation was less pronounced but still clearly visible. The observation of anthocyanin accumulation in the siliques of siar1 mutants and the characterization of SIAR1 as a bidirectional amino acid transporter led us to the assumption that the amino acid metabolism in these organs is disturbed. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the free amino acids of siliques of siar1 mutants and wild-type plants. The detailed amino acid composition and the total amount of free amino acids were analyzed at three different stages of silique development (Fig. 7B). Stage I included the six youngest siliques. Stage II comprised siliques that had not yet attained the maximum length and width of mature siliques. Stage III consisted of siliques that were of maximum size but still entirely green. The analyses were carried out for both alleles and compared with the analysis of the same stages of wild-type ecotype Columbia (Col-0) plants. The quantification of free amino acids in the three stages showed significant differences. In both alleles, an overall reduction in the total amino acid content could be determined. The strongest effect was detected in the siliques of stage I, which displayed the strongest anthocyanin accumulation. A less pronounced effect could be observed in the siliques of stage III (Fig. 7D). The largest divergence in the detailed amino acid analysis was detected for Pro. The siliques of siar1-1 mutants contained almost 10 times less Pro than the wild type (Fig. 7F). This alteration is weakened in siliques of stage II and reduced to a 2-fold difference in the oldest siliques (Supplemental Figs. S1–S3). During these later phases of silique development, the differences in the amino acid content are attenuated, probably because some other amino acid transporters can compensate for the loss of function of SIAR1. According to the tissue-specific microarray data of seeds, other members of the MtN21 family are expressed in the chalazal region (e.g. At2g39510; Le et al., 2010). Also, the amino acids Glu/Gln and Gly exhibited significant reductions in the siar1 mutants. In summary, a reduction of the overall amino acid content was observed with a strong reduction of Pro, Gln, and Glu concentrations. The reduction of Gln content was confirmed for siliques of plants of both siar1 alleles by a nontargeted metabolomic LC-MS analysis.

DISCUSSION

Amino acid transfer between different organs and their cycling through xylem and phloem ensure an optimal nitrogen allocation within the plant. At present, many amino acid importers from different families with individual expression patterns and substrate specificities are known. Our findings suggest that SIAR1, which is a plasma membrane-localized protein, exports amino acids from the cytosol into the apoplasmic space. To date, BAT1 (Dündar and Bush, 2009) and now SIAR1 are the only characterized amino acid transporters in plants that are capable of exporting amino acids from cells under physiological conditions. Previously characterized transporters are described to mediate solely amino acid import, mostly proton coupled, but also a proton-independent Gln transport was identified (Lalonde et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010).

SIAR1 is expressed at specific sites in planta, such as reproductive organs like anthers, developing ovules, and the growing embryo, where export from the cytosol into the apoplasm has been postulated (Lalonde et al., 2004). The specific expression of SIAR1 in cells of the chalazal region indicates its involvement in the export of amino acids from these cells. This region constitutes a sort of delivery zone where amino acids and other solutes arrive in large amounts via the phloem. From the phloem, the solutes are symplasmically unloaded and can migrate within the cells of the seed coat, which are connected by plasmodesmata (Imlau et al., 1999; Stadler et al., 2005). In contrast, no or few symplasmic connections exist between the maternal seed coat and the filial tissue. Thus, nutrients have to be exported into the apoplasmic space first, to be available for the adjacent cells that allocate the nutrients toward the sites of utilization (Thorne, 1985; Stadler et al., 2005). SIAR1 probably functions in the release of amino acids into the apoplasmic space in the chalazal region, from where they are subsequently available for import into adjacent cells of the endosperm and the embryo. It is already known that import of amino acids into the filial tissue is mediated by the high-affinity AAP1 (Hirner et al., 1998; Sanders et al., 2009). Besides AAP1, other secondary active amino acid importers, such as AAP8 or CATIONIC AMINO ACID TRANSPORTER6, were identified to be involved in amino acid uptake into developing seed (Okumoto et al., 2002; Hammes et al., 2006; Schmidt et al., 2007). In summary, our data contribute to complement and broaden the picture of amino acid transport in developing seeds by an export step mediated by SIAR1, which precedes the uptake via AAP1, AAP8, or CAT6.

As already mentioned, SIAR1 is also expressed in stamens (Lee and Tegeder, 2004), where the situation is similar to the one in developing seeds. At the connective tissue of the filament, assimilates are symplasmically unloaded from the phloem (Imlau et al., 1999) and need to be released from these cells. Once the amino acids are present in the apoplasmic space, they are available for the subsequent import into the tapetum cells. This import of amino acids is known to be LHT2 dependent (Lee and Tegeder, 2004). We propose that the release of amino acids out of the connective cells into the apoplasm is mediated by SIAR1.

In roots, SIAR1 expression is restricted to the cells of the pericycle, which are known to be involved in the radial transport of solutes and nutrients from the outer layers of the root into the central cylinder (Peterson and Enstone, 1996). Therefore, we postulate that SIAR1 could exert a function in loading amino acids into the xylem. Besides SIAR1, several transport proteins (e.g. the potassium channel SKOR, the boron exporter AtBOR1, and the nitrate transporter NRT1.5) function in xylem loading (Gaymard et al., 1998; Takano et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2008).

In leaves, SIAR1 expression is associated with the vascular tissue. Notably, a strong expression is found in source leaves in both the major and minor veins, while a weaker expression can be detected in sink leaves. A similar expression pattern was recently described for two members of the SWEET family (Chen et al., 2012). These Suc exporters mediate export from bundle sheath or phloem parenchyma cells into the apoplasm prior to the subsequent import into the sieve elements/companion cells by proton-coupled Suc importers like SUT1 (Riesmeier et al., 1994; Chen et al., 2012). In analogy, the amino acid exporter SIAR1 may be involved in exporting amino acids into the apoplasm before they are taken up into the sieve element/companion cell complex. Therefore, SIAR1 possibly acts in the allocation of amino acids from source to sink and thereby ensures the proper allocation of amino acids throughout the whole plant. However, more detailed studies are necessary to reveal the exact localization and function of SIAR1 within the vascular tissue.

Interestingly, SIAR1 was able to mediate the import and export of amino acids when expressed in yeast. The complementation of the mutant yeast strain JT16 was shown, which demonstrates clearly that SIAR1 allows a His import. The import function was further confirmed by uptake experiments. His import into JT16 cells is strongly favored by the concentration gradient, as the intracellular concentrations should be very low due to the autotrophy of this strain. In a wild-type strain, however, which has a high endogenous His-generating metabolism, the accumulation of His was reduced. This was the first indication that SIAR1 could act both as an importer and exporter. Similar transport characteristics were observed in Gln uptake experiments. Furthermore, Gln and a few other amino acids strongly accumulate in the supernatant of yeast cells expressing SIAR1. Actually, the detected spectrum of amino acids in the yeast medium does not necessarily correspond to the substrate preferences in planta, but it gives evidence that SIAR1 could be able to transport the above-mentioned amino acids. It cannot be entirely excluded that the overexpression of SIAR1 interferes with the expression or activity of endogenous yeast transporters and leads to an impaired reuptake from the medium in comparison with the control cells. However, this is unlikely, as the yeast strain used is deleted in all major Gln transporters. The accumulation in the supernatant is easily explained by an efflux mediated by SIAR1. To overcome the objections linked to the heterologous yeast expression system and to validate the yeast data, we performed oocyte experiments. When injected directly into the cells, Gln was exported by SIAR1. In general, oocytes display very little background transport (Miller and Zhou, 2000). SIAR1-expressing and Gln-injected oocytes contained significantly less Gln after 20 min compared with control cells, which is consistent with the postulated efflux activity. Taken together, our data based on two heterologous eukaryote expression systems give evidence for a Gln export function of SIAR1.

To date, the only other member of the MtN21 family described, WAT1, is involved in Trp and auxin metabolism (Ranocha et al., 2010). It might be possible that WAT1 also plays a role in the transport of amino acids or their derivatives, which could explain some aspects of the wat1 mutant phenotype. The mutants show enhanced sensitivity toward a toxic analog of Trp (Ranocha et al., 2010). As WAT1 localizes to the tonoplast, it can be speculated that it is involved in the export of Trp from the cytosol (and its toxic analog) into the vacuole (Ranocha et al., 2010; Okumoto and Pilot, 2011).

The proposed function of SIAR1 as an amino acid exporter is also reflected by the phenotype of siar1 mutants, which accumulate anthocyanins in the youngest siliques under constant light conditions. This anthocyanin hyperaccumulation is a well-known phenomenon in response to nitrogen limitation (Diaz et al., 2006). Consistently, the overall amount of free amino acid of siliques is reduced and the composition is altered in the mutants compared with the wild type. Notably, Pro as well as Glu and Gln levels are affected. Pro and Glu are especially important in silique and pollen development, as they can act on the one hand as readily accessible energy sources and on the other hand as compatible solutes and enhance the dehydration tolerance (Schwacke et al., 1999). The metabolisms of Pro and Glu/Gln are closely linked, as Pro synthesis occurs mainly via Glu, which is connected to the availability of Gln (Verbruggen et al., 1993; Verbruggen and Hermans, 2008). Thus, either the transport of Pro itself is impaired or the transport of the precursor Glu and Gln is defective in the mutants.

The amino acids altered in the siliques of siar1 mutants and those detected in the supernatant of yeast do not completely overlap. Basically, this could be due to different amino acid concentrations in the cytoplasm of the two organisms. But it can also be speculated that in yeast, a protein that is important for the transport specificity or activity is missing that is present in the plant. As was shown for the heteromeric mammalian amino acid transporter, one subunit of the complex regulates the activity, specificity, or targeting of the protein to its subcellular destination, whereas the other subunit mediates substrate specificity and the transport itself (Chillarón et al., 2001; Bröer, 2008). Interestingly, for members of the GDU family, a clear involvement in amino acid export could be shown, but the proteins themselves do not catalyze any transport (Pilot et al., 2004; Pratelli et al., 2010). It might be possible that also in plants, the combination of a transport protein and a regulatory protein could interact to form a heteromeric transport protein that mediates regulated transport.

CONCLUSION

Our data show that SIAR1 is an amino acid transporter able to export amino acids under physiological conditions. It is crucial for the correct allocation of amino acids throughout the plant. Generally, in reproductive organs, SIAR1 seems to play a role in amino acid efflux into the apoplasm subsequent to the unloading of amino acids from the long-distance transport.

The existence of a multitude of amino acid import proteins with distinct functions has been proven; likewise, a multitude of proteins that mediate amino acid efflux can be expected. The function of SIAR1 represents a further component besides the function of BAT1 (Dündar and Bush, 2009) in nitrogen cycling throughout the plant with postulated amino acid export steps (Lalonde et al., 2004; Okumoto and Pilot, 2011). Closely related proteins of the MtN21 family could accomplish further functions in the still largely elusive concept of cellular amino acid export in plants. Finally, by the molecular characterization of SIAR1, we add an important component to the current understanding of amino acid cycling in plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotype Col-0 plants were grown on soil in growth chambers (24 h of light, 22°C; plants used for amino acid HPLC) or in the greenhouse (16 h of light, 25°C; plants used for RNA gel-blot analysis, promoter-GUS, and full gene-GFP studies). The T-DNA insertion lines SALK_123331 and SALK_074699 were provided by the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory and were ordered at the European Arabidopsis Stock Centre (Alonso et al., 2003). Positive T-DNA insertion lines were identified with the following gene-specific primers and a pROK2 left border-specific oligonucleotide: for SALK_123331, At1g44800, allele siar1-1, siar1-1 fwd, 5′-ATGCATGTACATAGATGTGG-3′, and siar1-1 rev, 5′-CACCCTTACCACCTACTACTTG-3′; for SALK_074699, At1g44800, allele siar1-2, siar1-2 fwd, 5′-GAAAGGTCCACAGTGTTGCAAAAG-3′, and siar1-2 rev, 5′-TCAGTACTGGTAACCACACC-3′. The sites of T-DNA insertion were confirmed by sequencing of the obtained PCR products.

Expression Levels

The expression levels of SIAR1 in the homozygous SALK lines were analyzed in comparison with the wild type by qPCR. RNA was extracted from leaves and treated with DNaseI. With 2.5 μg of DNA-free RNA, reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 10 μL. The resulting product was diluted 50-fold, and 5 μL of the diluted product served as a template for qPCR. For amplification, 10 μL of LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche) and 5 μL of specific oligonucleotides (1 μm) were used. The reaction was carried out with a Roche Lightcycler 480 (Roche Applied Science). Oligonucleotides for qPCR were SIAR1 Q fwd, 5′-ACTTCCCGCCGTCACCTT-3′, and SIAR1 Q rev, 5′-CCGTTATTACCGTTCCTACCACTT-3′.

RNA Gel-Blot Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from roots, stems, mature, sink, source, and cauline leaves, flowers, siliques, and seedlings. Twenty micrograms of RNA was separated on formaldehyde-containing 1.2% agarose gels (Riesmeier et al., 1994) and immobilized on a nylon membrane (Hybond N+; Amersham). Hybridization was performed at 65°C in 0.3 m sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 7% SDS, 1 mm EDTA, and 1% bovine serum albumin overnight using SIAR1 cDNA as a probe. Radioactive labeling of the probe was performed using the HexaLabel DNA Labeling Kit (MBI Fermentas), 100 ng of template DNA, and 50 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP. After hybridization, two washing steps (2× SSC, 0.2% SDS at 65°C and 0.2× SSC, 0.2% SDS at 65°C, 20 min each) were performed, and the membrane was exposed to x-ray film (Hyperfilm; Amersham).

DNA Work

Cloning of the Yeast Expression Vector

To obtain the cDNA, RNA from Arabidopsis seedlings was used for first-strand synthesis with RevertAid Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (MBI Fermentas). The ORF of SIAR1 was amplified by PCR using Turbo Pfu Polymerase (Stratagene) on first-strand cDNA with the following oligonucleotides: SIAR1 PstI, 5′-gagactgcagAAGATGAAAGGTGGAAGCATG-3′, and SIAR1 SalI, 5′-cccccgtcgacTCAGGTACTGGTAACCACAC-3′ (the uppercase letters are sequence specific nucleotides, whereas the lowercase letters represent oligonucleotides containing restriction sites). The ORF was cloned with PstI/SalI into the yeast expression vector pDR196 (Rentsch et al., 1995). The sequence was verified by sequencing the resulting SIAR1-pDR196 construct.

cDNA-GFP Fusions

For transient overexpression in Arabidopsis protoplasts, the ORF of SIAR1 was amplified by PCR using SIAR1-pDR196 as template. The resulting sequence was inserted after the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and before the GFP5 (S65T) gene of the pCF203 vector (Dettmer et al., 2005). Primers with PstI and BamHI restriction sites were used: SIAR1 PstI, 5′-gagactgcagAAGATGAAAGGTGGAAGCATG-3′, and SIAR1 rev GFP BamHI, 5′-aaaaggatcccGGTACTGGTAACCACACCG-3′.

PSIAR1SIAR1:GFP Construct

The SIAR1 promoter-full gene-GFP construct consists of a 2.9-kb promoter and a 2.5-kb genomic sequence except for the last triplet of the ORF. Genomic Col-0 DNA was used as a template. The sequence was cloned in front of the GFP gene into the binary vector pGTkan (binary, GFP gene-containing vector based upon the N-terminal TAPa T-DNA vector pN-TAPa [GenBank accession no. AY788908.1], kindly provided by Karin Schumacher) using SacI/BamHI restriction enzymes. The oligonucleotides are as follows: SIAR1 gfp SacI fwd, 5′-gagagagctcATCTAACAAATGTTGTTCGTCCG-3′, and SIAR1 gfp BamHI rev, 5′-tctcggatcccGGTACTGGTAACCACACCG-3′.

PSIAR1:GUS Construct

The following oligonucleotides were used to amplify the 2.9-kb promoter and the 1.3-kb genomic sequence of SIAR1 using genomic Col-0 DNA as a template: SIAR1 GUS XhoI fwd, 5′-agagctcgagATCTAACAAATGTTGTTCGTCCG-3′, and SIAR1 GUS PstI rev, 5′-gagactgcagGTAGTACAAATTCTGGTCCATGAG-3′.

The fragment includes nucleotides of the coding region up to the second intron. The sequence was introduced into the vector pUTkan (binary, GUS gene-containing vector based upon the N-terminal TAPa T-DNA vector pN-TAPa [GenBank accession no. AY788908.1], kindly provided by Karin Schumacher) with the restriction enzymes XhoI and PstI in front of the region that encodes the uidA gene and finally results in a translational fusion to the GUS protein.

Stable Transformation of Arabidopsis Plants

The constructs were introduced into Arabidopsis Col-0 plants by transformation with the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain pGV3101 by spraying. More than 20 independent insertions were selected and propagated. Homozygous plants of the T3 generation were analyzed.

Transient Overexpression of SIAR1-GFP in Protoplasts

Transient transformation of protoplasts from Arabidopsis Col-0 dark-grown cell culture with polyethylene glycol was performed as published earlier (Negrutiu et al., 1987).

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

GFP-expressing tissues and protoplasts were imaged using a confocal laser scanning microscope (TCS SP II; Leica Microsystems) equipped with Leica Confocal Software 2.5. The 488-nm argon laser line was used for excitation. GFP fluorescence was observed from 495 to 530 nm. For cell wall staining, the tissue was incubated in 0.5% propidium iodide for 10 min at room temperature and washed twice with water. Propidium iodide-derived red fluorescence was detected at 595 to 640 nm, and chlorophyll autofluorescence was detected at 640 to 730 nm.

Yeast Strains, Growth Assays, and Uptake Experiments

The following Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains were used: 22Δ8AA (Matα, ura3-1, gap1, put4-1, uga4-1, can1::HisG, lyp/alp::HisG, hip1::HisG, dip5::HisG; Fischer et al., 2002); 23344c (Matα, ura3-1; Soussi-Boudekou et al., 1997); and JT16 (MATa hip1-614 his4-401 ura 3-52 ino1 can1; Tanaka and Fink, 1985).

Yeast cells were transformed with SIAR1-pDR196 or with pDR196 and selected on medium lacking uracil.

Transport Measurements in Yeast

Transport measurements in yeast were performed as described (Hirner et al., 2006). A final concentration of 10 μm for each amino acid was used (l-[U-14C]His, 11.6 GBq mmol−1; l-[U-14C]Glu, 9.47 GBq mmol−1; l-[U-14C]Gln, 9.1 GBq mmol−1; l-[U-14C]Phe, 17.4 GBq mmol−1; l-[U-14C]Asp, 7.66 GBq mmol−1 [Amersham Bioscience]).

Yeast Growth Test on His

The indicated concentrations of His were adjusted in synthetic complete medium.

Amino Acid Analytics in the Supernatant of Yeast Cell Cultures

SIAR1-expressing cells and control cells of the yeast strain 22Δ8AA were grown in minimal medium until an optical density at 600 nm of 2.0. After sedimentation, 5 mL of the supernatant was collected, lyophilized, and redissolved in 1.5 mL of 100% methanol. Solubilization was carried out two times for 3 min in an ultrasonic bath. Again, the samples were centrifuged and 1 mL of supernatant was dried in a SpeedVac. The sediment was resuspended in 250 μL of lithium buffer (Pickering Laboratories), and the solution was filtered (0.2-μm Minisart RC15 filters) before analysis. Amino acids were analyzed by ion-exchange chromatography (high-efficiency fluid column, 3 mm × 150 mm; Pickering Laboratories) with postcolumn ninhydrin derivatization (Hirner et al., 2006). To demonstrate the integrity of the yeast cells, a viability test was performed with trypan blue (Kucsera et al., 2000).

Transport Measurements in Oocytes

SmaI and SalI were used to digest the SIAR1 cDNA from SIAR1-pDR196 and introduce it into the oocyte expression vector pOO2. The resulting construct was linearized with MluI. Complementary RNA was synthesized by using the Sp6 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion). The preparation of Xenopus laevis oocytes and the uptake experiments were performed as described before (Hammes et al., 2006). In the uptake measurements, 1 mm amino acid was supplied as substrate, of which 0.44 μm was radioactively labeled. The experiment was performed in Ringer’s solution, pH 5.0.

For the efflux measurements, 50 nL of radioactively labeled Gln was injected into oocytes, resulting in a final concentration of 1 mm, as the oocyte volume was estimated to be 0.5 μL. After 5 min of recovery in ND96 solution (pH 7.5), the oocytes were transferred into fresh ND96 solution and incubated for 10 or 20 min. In each case, five control and five SIAR1-expressing oocytes were used. After the indicated time, the oocytes were washed once and transferred into scintillation vials that contained 0.5 mL of 10% SDS for lysis of the oocytes, incubated, and measured using Ultima Gold as the scintillation cocktail. The experiment was performed with oocytes from two different frogs.

Histochemical Localization of GUS Activity

Plant material was harvested and infiltrated with 1.5% formaldehyde-containing phosphate buffer (34.2 mm Na2HPO4, 15.8 mm NaH2PO4, 0.25% Triton X-100, and 1.5% formaldehyde). After three wash cycles with phosphate buffer, GUS-staining solution [phosphate buffer, 0.5 mm K4(Fe[CN]6), 0.5 mm K3(Fe[CN]6), and 1 mm 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-glucuronic acid] was vacuum infiltrated and subsequently incubated at 37°C for 12 h. Plant material was cleared in 70% ethanol.

Amino Acid Analytics from Plant Material

Plant material was harvested and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The frozen material was ground to homogeneity and lyophilized. Ten milligrams of freeze-dried powder was extracted twice (3 min per extraction), once with 80% methanol and once with 20% methanol at 100°C. Norleucine (0.2 mm) was added as an internal standard. Both extracts were pooled, vacuum dried, and resuspended in lithium buffer (0.7% lithium acetate and 0.6% LiCl; Pickering Laboratories). After centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered (0.2-μm Minisart RC15 filters). Amino acids were analyzed by ion-exchange chromatography (high-efficiency fluid column, 3 mm × 150 mm; Pickering Laboratories) with postcolumn ninhydrin derivatization (Hirner et al., 2006).

Quantification of Amino Acids in Xylem Exudate

The quantification of amino acids in xylem exudates was performed according to Pilot et al. (2004), but instead of being lyophilized, the xylem sap was directly filtered (0.2-μm Minisart RC15 filters) and used for amino acid determination.

Metabolomic LC-MS Analysis of Plant Material

Ten milligrams of homogenized and lyophilized material was sonicated in 500 μL of methanol at room temperature for 5 min, incubated for 30 min on ice, and sedimented at 14,000 rpm at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and kept on ice. The sediment was resuspended in 500 μL of 20% methanol containing 0.1% formic acid and sonicated again for 5 min at room temperature. This was followed by an incubation of 30 min on ice and centrifugation as described above. The pooled supernatant fractions were dried in a SpeedVac, resuspended in 150 μL of 20% methanol containing 0.1% formic acid, and sedimented. Five microliters of the supernatant was analyzed with an LC-MS system comprising an Acquity UPLC apparatus and a Synapt G2 Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Waters). Reverse-phase HPLC was carried out on a Waters C18 column (2.1 mm × 10 cm, 1.8 μm) with a flow rate of 0.25 mL min−1. The starting condition consisted of 98% solvent A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and 2% solvent B (methanol and 0.1% formic acid) for 2 min, followed by a 25-min linear gradient to 100% solvent B. Samples were ionized by electrospray ionization, and a mass range between 50 and 1,200 mass-to-charge ratio was detected.

Data analysis was performed with MarkerLynx software (Waters). Statistical analysis was conducted with the Extended Statistics Software Package (Umetrics).

Anthocyanin Identification

Extracts were acidified with 0.1% formic acid and purified by HPLC with subsequent diode array detection. Fractions containing red staining were collected and further analyzed by LC-MS/MS (for conditions, see above). For compound characterization, MS/MS fragmentation studies were performed.

Accompanying sequence data can be found under The Arabidopsis Information Resource accession locus 2194864. Other sequence data are given as Arabidopsis Genome Initiative at respective positions throughout the text.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Detailed amino acid quantification of siliques of stage I.

Supplemental Figure S2. Detailed amino acid quantification of siliques of stage II.

Supplemental Figure S3. Detailed amino acid quantification of siliques of stage III.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Guillaume Pilot for providing qPCR primer. We are very grateful to Dierk Wanke, Guillaume Pilot, Réjane Pratelli, and Wolf Frommer for many helpful discussions. We further thank Bettina Stadelhofer for excellent technical assistance.

References

- Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ, Kim CJ, Chen H, Shinn P, Stevenson DK, Zimmerman J, Barajas P, Cheuk R, et al. (2003) Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301: 653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloor SJ, Abrahams S. (2002) The structure of the major anthocyanin in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 59: 343–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bröer S. (2008) Amino acid transport across mammalian intestinal and renal epithelia. Physiol Rev 88: 249–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush DR. (1993) Proton-coupled sugar and amino acid transporters in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 44: 513–542 [Google Scholar]

- Chen L-Q, Qu X-Q, Hou B-H, Sosso D, Osorio S, Fernie AR, Frommer WB. (2012) Sucrose efflux mediated by SWEET proteins as a key step for phloem transport. Science 335: 207–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chillarón J, Roca R, Valencia A, Zorzano A, Palacín M. (2001) Heteromeric amino acid transporters: biochemistry, genetics, and physiology. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F995–F1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassler T, Maier T, Winterhalter C, Böck A. (2000) Identification of a major facilitator protein from Escherichia coli involved in efflux of metabolites of the cysteine pathway. Mol Microbiol 36: 1101–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer J, Schubert D, Calvo-Weimar O, Stierhof Y-D, Schmidt R, Schumacher K. (2005) Essential role of the V-ATPase in male gametophyte development. Plant J 41: 117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz C, Saliba-Colombani V, Loudet O, Belluomo P, Moreau L, Daniel-Vedele F, Morot-Gaudry J-F, Masclaux-Daubresse C. (2006) Leaf yellowing and anthocyanin accumulation are two genetically independent strategies in response to nitrogen limitation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 74–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dündar E. (2009) Multiple GUS expression patterns of a single Arabidopsis gene. Ann Appl Biol 154: 33–41 [Google Scholar]

- Dündar E, Bush DR. (2009) BAT1, a bidirectional amino acid transporter in Arabidopsis. Planta 229: 1047–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W-N, Loo DDF, Koch W, Ludewig U, Boorer KJ, Tegeder M, Rentsch D, Wright EM, Frommer WB. (2002) Low and high affinity amino acid H+-cotransporters for cellular import of neutral and charged amino acids. Plant J 29: 717–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa Y, Segawa H, Kim JY, Chairoungdua A, Kim DK, Matsuo H, Cha SH, Endou H, Kanai Y. (2000) Identification and characterization of a Na+-independent neutral amino acid transporter that associates with the 4F2 heavy chain and exhibits substrate selectivity for small neutral D- and L-amino acids. J Biol Chem 275: 9690–9698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaymard F, Pilot G, Lacombe B, Bouchez D, Bruneau D, Boucherez J, Michaux-Ferrière N, Thibaud J-B, Sentenac H. (1998) Identification and disruption of a plant shaker-like outward channel involved in K+ release into the xylem sap. Cell 94: 647–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammes UZ, Nielsen E, Honaas LA, Taylor CG, Schachtman DP. (2006) AtCAT6, a sink-tissue-localized transporter for essential amino acids in Arabidopsis. Plant J 48: 414–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirner A, Ladwig F, Stransky H, Okumoto S, Keinath M, Harms A, Frommer WB, Koch W. (2006) Arabidopsis LHT1 is a high-affinity transporter for cellular amino acid uptake in both root epidermis and leaf mesophyll. Plant Cell 18: 1931–1946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirner B, Fischer WN, Rentsch D, Kwart M, Frommer WB. (1998) Developmental control of H+/amino acid permease gene expression during seed development of Arabidopsis. Plant J 14: 535–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlau A, Truernit E, Sauer N. (1999) Cell-to-cell and long-distance trafficking of the green fluorescent protein in the phloem and symplastic unloading of the protein into sink tissues. Plant Cell 11: 309–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack DL, Yang NM, Saier MH., Jr (2001) The drug/metabolite transporter superfamily. Eur J Biochem 268: 3620–3639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucsera J, Yarita K, Takeo K. (2000) Simple detection method for distinguishing dead and living yeast colonies. J Microbiol Methods 41: 19–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde S, Sero A, Pratelli R, Pilot G, Chen J, Sardi MI, Parsa SA, Kim D-Y, Acharya BR, Stein EV, et al. (2010) A membrane protein/signaling protein interaction network for Arabidopsis version AMPv2. Front Physiol 1: 24 [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde S, Wipf D, Frommer WB. (2004) Transport mechanisms for organic forms of carbon and nitrogen between source and sink. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55: 341–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le BH, Cheng C, Bui AQ, Wagmaister JA, Henry KF, Pelletier J, Kwong L, Belmonte M, Kirkbride R, Horvath S, et al. (2010) Global analysis of gene activity during Arabidopsis seed development and identification of seed-specific transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 8063–8070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-H, Tegeder M. (2004) Selective expression of a novel high-affinity transport system for acidic and neutral amino acids in the tapetum cells of Arabidopsis flowers. Plant J 40: 60–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillo C, Lea US, Ruoff P. (2008) Nutrient depletion as a key factor for manipulating gene expression and product formation in different branches of the flavonoid pathway. Plant Cell Environ 31: 587–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S-H, Kuo H-F, Canivenc G, Lin C-S, Lepetit M, Hsu P-K, Tillard P, Lin H-L, Wang Y-Y, Tsai C-B, et al. (2008) Mutation of the Arabidopsis NRT1.5 nitrate transporter causes defective root-to-shoot nitrate transport. Plant Cell 20: 2514–2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodwig EM, Hosie AHF, Bourdès A, Findlay K, Allaway D, Karunakaran R, Downie JA, Poole PS. (2003) Amino-acid cycling drives nitrogen fixation in the legume-Rhizobium symbiosis. Nature 422: 722–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier C, Ristic Z, Klauser S, Verrey F. (2002) Activation of system L heterodimeric amino acid exchangers by intracellular substrates. EMBO J 21: 580–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AJ, Zhou JJ. (2000) Xenopus oocytes as an expression system for plant transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta 1465: 343–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrutiu I, Shillito R, Potrykus I, Biasini G, Sala F. (1987) Hybrid genes in the analysis of transformation conditions. 1. Setting up a simple method for direct gene-transfer in plant-protoplasts. Plant Mol Biol 8: 363–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumoto S, Pilot G. (2011) Amino acid export in plants: a missing link in nitrogen cycling. Mol Plant 4: 453–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumoto S, Schmidt R, Tegeder M, Fischer WN, Rentsch D, Frommer WB, Koch W. (2002) High affinity amino acid transporters specifically expressed in xylem parenchyma and developing seeds of Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 277: 45338–45346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CA, Enstone DE. (1996) Functions of passage cells in the endodermis and exodermis of roots. Physiol Plant 97: 592–598 [Google Scholar]

- Pilot G, Stransky H, Bushey DF, Pratelli R, Ludewig U, Wingate VPM, Frommer WB. (2004) Overexpression of GLUTAMINE DUMPER1 leads to hypersecretion of glutamine from hydathodes of Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell 16: 1827–1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratelli R, Voll LM, Horst RJ, Frommer WB, Pilot G. (2010) Stimulation of nonselective amino acid export by glutamine dumper proteins. Plant Physiol 152: 762–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranocha P, Denancé N, Vanholme R, Freydier A, Martinez Y, Hoffmann L, Köhler L, Pouzet C, Renou JP, Sundberg B, et al. (2010) Walls are thin 1 (WAT1), an Arabidopsis homolog of Medicago truncatula NODULIN21, is a tonoplast-localized protein required for secondary wall formation in fibers. Plant J 63: 469–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentsch D, Laloi M, Rouhara I, Schmelzer E, Delrot S, Frommer WB. (1995) NTR1 encodes a high affinity oligopeptide transporter in Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett 370: 264–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentsch D, Schmidt S, Tegeder M. (2007) Transporters for uptake and allocation of organic nitrogen compounds in plants. FEBS Lett 581: 2281–2289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesmeier JW, Willmitzer L, Frommer WB. (1994) Evidence for an essential role of the sucrose transporter in phloem loading and assimilate partitioning. EMBO J 13: 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ezpeleta N, Brinkmann H, Burey SC, Roure B, Burger G, Löffelhardt W, Bohnert HJ, Philippe H, Lang BF. (2005) Monophyly of primary photosynthetic eukaryotes: green plants, red algae, and glaucophytes. Curr Biol 15: 1325–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders A, Collier R, Trethewy A, Gould G, Sieker R, Tegeder M. (2009) AAP1 regulates import of amino acids into developing Arabidopsis embryos. Plant J 59: 540–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Davison TS, Henz SR, Pape UJ, Demar M, Vingron M, Schölkopf B, Weigel D, Lohmann JU. (2005) A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat Genet 37: 501–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R, Stransky H, Koch W. (2007) The amino acid permease AAP8 is important for early seed development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 226: 805–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacke R, Grallath S, Breitkreuz KE, Stransky E, Stransky H, Frommer WB, Rentsch D. (1999) LeProT1, a transporter for proline, glycine betaine, and gamma-amino butyric acid in tomato pollen. Plant Cell 11: 377–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacke R, Schneider A, van der Graaff E, Fischer K, Catoni E, Desimone M, Frommer WB, Flügge U-I, Kunze R. (2003) ARAMEMNON, a novel database for Arabidopsis integral membrane proteins. Plant Physiol 131: 16–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soussi-Boudekou S, Vissers S, Urrestarazu A, Jauniaux J-C, André B. (1997) Gzf3p, a fourth GATA factor involved in nitrogen-regulated transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol 23: 1157–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler R, Lauterbach C, Sauer N. (2005) Cell-to-cell movement of green fluorescent protein reveals post-phloem transport in the outer integument and identifies symplastic domains in Arabidopsis seeds and embryos. Plant Physiol 139: 701–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano J, Noguchi K, Yasumori M, Kobayashi M, Gajdos Z, Miwa K, Hayashi H, Yoneyama T, Fujiwara T. (2002) Arabidopsis boron transporter for xylem loading. Nature 420: 337–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka J, Fink GR. (1985) The histidine permease gene (HIP1) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 38: 205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne JH. (1985) Phloem unloading of C and N assimilates in developing seeds. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 36: 317–343 [Google Scholar]

- Tohge T, Nishiyama Y, Hirai MY, Yano M, Nakajima J, Awazuhara M, Inoue E, Takahashi H, Goodenowe DB, Kitayama M, et al. (2005) Functional genomics by integrated analysis of metabolome and transcriptome of Arabidopsis plants over-expressing an MYB transcription factor. Plant J 42: 218–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen N, Hermans C. (2008) Proline accumulation in plants: a review. Amino Acids 35: 753–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen N, Villarroel R, Van Montagu M. (1993) Osmoregulation of a pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase gene in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 103: 771–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner D, Gerlitz N, Stadler R. (2011) A dual switch in phloem unloading during ovule development in Arabidopsis. Protoplasma 248: 225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Bogner M, Stierhof Y-D, Ludewig U. (2010) H-independent glutamine transport in plant root tips. PLoS ONE 5: e8917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.