Abstract

Multigene expression is required for metabolic engineering, i.e. coregulated expression of all genes in a metabolic pathway for the production of a desired secondary metabolite. To that end, several transgenic approaches have been attempted with limited success. Better success has been achieved by transforming plastids with operons. IL-60 is a platform of constructs driven from the geminivirus Tomato yellow leaf curl virus. We demonstrate that IL-60 enables nontransgenic expression of an entire bacterial operon in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants without the need for plastid (or any other) transformation. Delivery to the plant is simple, and the rate of expressing plants is close to 100%, eliminating the need for selectable markers. Using this platform, we show the expression of an entire metabolic pathway in plants and delivery of the end product secondary metabolite (pyrrolnitrin). Expression of this unique secondary metabolite resulted in the appearance of a unique plant phenotype disease resistance. Pyrrolnitrin production was already evident 2 d after application of the operon to plants and persisted throughout the plant's life span. Expression of entire metabolic pathways in plants is potentially beneficial for plant improvement, disease resistance, and biotechnological advances, such as commercial production of desired metabolites.

Prokaryotic genes are usually clustered in operons under the control of a common promoter, and proteins are translated from a polycistronic mRNA (Jacob and Monod, 1961; Kozak, 1983; Salgado et al., 2000; Ermolaeva et al., 2001). Eukaryotic proteins are translated from their generally monocistronic mRNAs in a 5′-dependent manner (Kozak, 1983). Nevertheless, evidence shows that in some cases, eukaryotic genes associated with functionally related activities are also clustered together and coexpressed (Descombes and Schibler, 1991; Yamanaka et al., 1997; Welm et al., 1999; Ramji and Foka, 2002; Hurst et al., 2004; Amoutzias and Van de Peer, 2008; Field and Osbourn, 2008). Gene clustering may also result in coregulation of gene expression, and in some cases, genes participating in a certain metabolic pathway are clustered and coregulated. However, they do not always share a common cis-element, such as a promoter, and they are not always coregulated by translation from the same polycistronic mRNA (Amoutzias and Van de Peer, 2008). Several cis-controlled clusters have arisen from gene duplication and divergence, e.g. the human β-globin gene cluster (Hardison et al., 1997). However, such clusters represent homologs of the same ancestral gene and not diverse genes requiring coordinated regulation for a particular metabolic pathway. On the other hand, heterologous gene clusters participating in the same metabolic pathway have been found in plants (Gierl and Frey, 2001; Shimura et al., 2007; Field and Osbourn, 2008; Jonczyk et al., 2008). Clustering indicates the possibility of cosegregation (preserving the clusters upon meiosis and recombination). However, despite the “operon-like” clustering and coexpression of pertinent genes (Field and Osbourn, 2008), expression from a single transcription unit, such as the classical operon, has not yet been demonstrated in eukaryotes. The current dogma is that in most cases, coregulation of eukaryotic gene clusters is due to chromosomal arrangements and chromatin potentiation, which affects an entire chromosomal domain (e.g. Kingston and Narlikar, 1999; Gierman et al., 2007). Cases in which expression of dicistronic mRNAs is regulated by readthrough of a stop codon have also been reported (e.g. Descombes and Schibler, 1991; García-Ríos et al., 1997).

Operon-like gene organization has been found in nematodes, yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), and some higher eukaryotes (e.g. Ben-Shahar et al., 2007; Shimura et al., 2007; Vázquez-Manrique et al., 2007; Field and Osbourn, 2008; Qian and Zhang, 2008). However, the term “operon-like” may not be accurate in all cases; “clustered organization” better describes the various situations. Nematodes and Drosophila carry gene clusters that are transcribed to polycistronic pre-mRNAs and on a structural basis can be defined as operon like (summarized in Blumenthal, 2004). However, unlike in prokaryotes, the polycistronic pre-mRNAs are processed to monocistronic (sometimes dicistronic) mature mRNAs and are coregulated by virtue of being transcribed from the same promoter. Intergenic regions (IRs) are removed by splicing and open reading frames (ORFs) are condensed to form a number of mRNAs. The resultant monocistronic mRNAs are transspliced to SL2 (a species of small nuclear RNA), which carries a cap structure, enabling 5′ initiation of translation from each individual monocistronic structure (Blumenthal et al., 2002).

Several rhizospheric bacteria produce antifungal and antibacterial secondary metabolites, and their use as biocontrol agents of soil-borne plant pathogens has been attempted (Weller et al., 2002; Spadaro and Gullino, 2005; Lugtenberg and Kamilova, 2009). Arima et al. (1964) were the first to our knowledge to report the antibiotic compound 3-chloro-4-(2'-nitro-3′-chlorophenyl)-pyrrole (pyrrolnitrin [PRN]) produced by a number of Pseudomonas pyrrocinia strains. PRN has been found active against a wide range of pathogens (e.g. Chernin et al., 1996; el-Banna and Winkelmann, 1998) and is produced by other bacterial species as well, including Pseudomonas fluorescens, Burkholderia cepacia, and Serratia plymuthica (Yoshihisa et al., 1989; Burkhead et al., 1994; Hill et al., 1994; Kalbe et al., 1996; Hammer et al., 1999; Kamensky et al., 2003; Ovadis et al., 2004). A four-gene operon coding for an enzymatic pathway converting Trp to PRN has been identified (Kirner et al., 1998) and the function of every encoded protein determined (Kirner et al., 1998). No significant homology has been found between the first three enzymes (PrnA, PrnB, and PrnC) and any plant protein. However, pheophorbide a deoxygenase (synonymous with ACD1 and LLS1) from several plants shows 42% to 48% similarity to PrnD.

IL-60 is a platform of constructs derived from the geminivirus Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV). The IL-60 system has provided universal expression or silencing in all plants tested to date (Peretz et al., 2007). We present a case in which the universal DNA plant vector system, IL-60, mediated the introduction and expression of an entire bacterial operon in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants. The operon was transcribed and translated in the plant in a manner conforming to that of classical bacterial operons. Expression of the entire pathway resulted in the appearance of a unique secondary metabolite (PRN), creating a unique beneficial plant phenotype.

The biosynthesis of a secondary metabolite involves numerous enzymes, the genes of which constitute a metabolic pathway. Attempts to introduce multiple genes into plants by various techniques (e.g. gene stacking) have been somewhat successful (Halpin, 2005). However, lack of coregulation remains the main obstacle in this latter technique. The best method to date for metabolic engineering is plastid transformation. Because plastids are of prokaryotic origin, they can express several genes from a single polycistronic mRNA. The ability to express a string of coregulated genes could potentially result in activation of an entire metabolic pathway and the production of its end product, a nonproteinaceous secondary metabolite (Wang et al., 2009). However, for this to happen, an operon and its regulatory elements have to be artificially constructed, and concerted regulation and optimization of the stoichiometry of the various components have yet to be achieved.

Here, we report on a vector system that introduces an entire operon into plants; its genes are expressed, producing the end product secondary metabolite. The need for plastid transformation is circumvented, administration to plants is easy, and yield of successfully expressing plants is high, making the use of selectable markers unnecessary.

RESULTS

Delivery, Replication, Expression, and Spread of the prn Operon in Tomato Plants

The components of the plant universal vector IL-60 employed throughout this study are described in Peretz et al. (2007). Briefly, a plasmid was inserted into the replication-associated gene of TYLCV, disabling rolling-circle replication but maintaining replication from double-stranded DNA to double-stranded DNA, which is directed solely by host factors. Any DNA placed downstream of the viral IR that carries the origin of replication and two bidirectional promoters will replicate in the cells into which it has been delivered. However, to spread to other cells, it requires a helper virus or IL-60-BS, which promotes movement throughout the plant without causing disease. The various constructs employed in this study are illustrated in Supplemental Figure S1. All constructs were administered to the plants by root uptake. The root tips of young seedlings were slightly trimmed and immersed in an aqueous solution containing 1 μg of each plasmid per plant. Tap water was added when the solution was fully absorbed by the plants and the plants were immersed for 3 d, after which they were planted in soil.

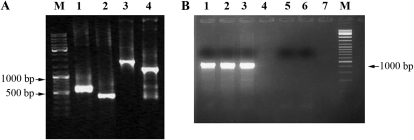

The entire prn operon of P. fluorescens strain Pf-5 (GenBank accession no. CP000076.1; bases 4,157,074–4,162,815) was cloned in front of the IR in the plasmid pD-IR and was designated IR-PRN. The plasmid construct consisted of the IR, a 160-bp stretch of the 5′ end of gene V2 (precoat) of TYLCV carrying a postulated plant ribosomal binding site (RBS), followed by the prn operon starting at the first ATG of prnA. IR-PRN was administered to plants along with the IL-60-BS “driver” as described in “Materials and Methods.” IR-PRN replication and spread in the plant was determined by PCR of DNA extracted from leaves and other plant organs. Primers used for amplification of the various segments of the operon are shown in Supplemental Table S1 and Supplemental Figure S2. Two weeks after administration to plants, prn DNA was found in all tested tissues, including flowers and fruits at flowering and fruit set (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Analysis for the presence of prn genes in treated plants. A, DNA was extracted from systemic leaves and subjected to PCR using different sets of primers (Supplemental Table S1). M, Size markers. Amplification of: a prnA fragment (lane 1), TYLCV-IR (lane 2), a prnB and prnC-spanning fragment (lane 3), and a prnD fragment (lane 4). B, Presence of prnA in various tomato organs. Amplification with prnA primers of DNA extracted from roots (lane 1), leaves (lane 2), fruits (lane 3), leaves of an untreated plant (lane 5), and without template (lane 6). Lanes 4 and 7, Empty. M, Size markers.

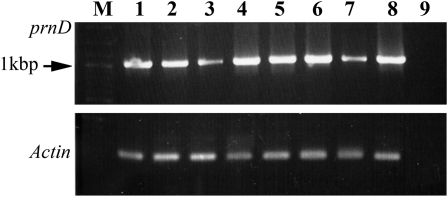

Transcription from IR-PRN was determined by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (Fig. 2) by analyzing ribosome-bound RNA (as cDNA) and by northern-blot analysis (described below).

Figure 2.

RT-PCR analysis for transcription of the prn operon. The amplified sequence is a segment of prnD. RT-PCR of the same plant RNAs amplifying a fragment of tomato actin is depicted at the bottom. M, Size markers. Lanes 1 to 8, Template RNA extracted from various prn-carrying plants. Lane 9, Control; RNA was extracted from untreated plant.

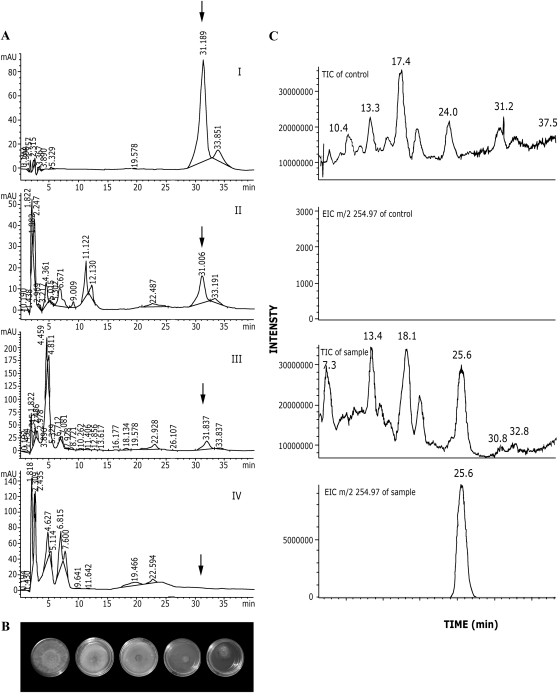

Plants Harboring the prn Operon Produce Biologically Active PRN

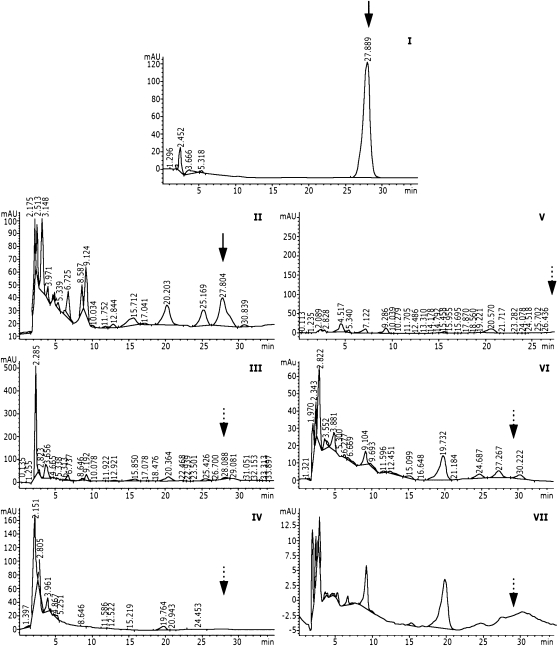

In bacteria, the end product of the prn operon is PRN. We demonstrated that plants treated with the IR-PRN vector system produce PRN. Extracts of various plant organs were analyzed by HPLC as described in “Materials and Methods.” HPLC samples were adjusted for equal protein content. PRN was found in extracts of roots and leaves of plants carrying IR-PRN (Fig. 3A) but not in fruits. Liquid chromatography (LC)-mass spectrometry (MS) analysis (Fig. 3C) identified a peak in IR-PRN-treated plants that was absent in control plants, corresponding in mass (254.97 D) to PRN.

Figure 3.

HPLC and LC-MS analyses of the metabolites produced in PRN-expressing tomato plants. A, HPLC elution profiles. I, Synthetic PRN (positive control); II, root extract of PRN-expressing plants; III, leaf extract of PRN-expressing plants; IV, negative control. Root extract of untreated plants. Positions of PRN elution are indicated by arrows. B, Biological activity of the various fractions of AII. Each plate contains a disk of agar with R. solani mycelium and addition of (left to right) fractions eluted between 1 and 3 min, fractions eluted between 3 and 5 min, fractions eluted between 5 and 25 min, fractions eluted between 30 and 32 min, and synthetic PRN (0.2 μg/plate). C, LC-MS analysis of tomato extracts. The two top panels present extracts from plants not carrying IR-PRN. The two bottom panels present extracts from IR-PRN-harboring plants. LC patterns (total [negative] ion chromatogram [TIC]) are shown in the first and third panels from the top. Searches for PRN by mass (EIC, extracted ion chromatogram) are shown in the second and fourth panels.

PRN is an antifungal, antibacterial compound that inhibits the growth of a wide spectrum of plant pathogens. One of the affected pathogens is the fungus Rhizoctonia solani. Therefore, we tested the various HPLC-eluted fractions for their capacity to inhibit the growth of R. solani. Biological tests showed that the plant-extracted, HPLC-purified PRN was indeed inhibitory to R. solani (Fig. 3B). It was concluded that the plants produced PRN identical to that produced in bacteria by the same operon.

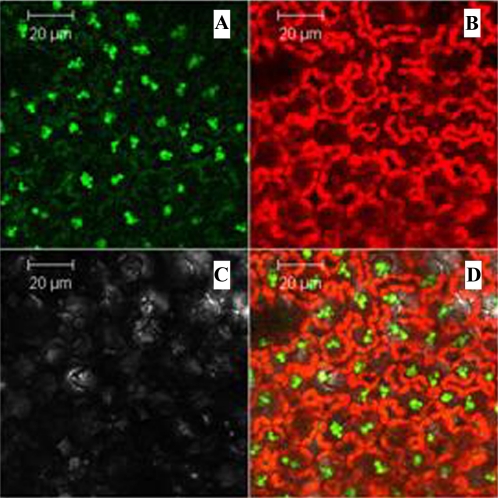

Furthermore, prn expression in plants is shown to be polycistronic. To determine whether, in addition to prnA (which carries a viral RBS in front of it), the other three ORFs are also required for PRN production and are not replaced by functionally equivalent plant proteins, we mutated those genes. We first tested whether translation of the most 3′-distal ORF (prnD) originates from the IR-directed construct and not from a gene directed by a plant promoter. We fused GFP (the 5′−untranslated region was deleted to remove predicted RBSs, and the first ATG was omitted to prevent possible translation initiation at the start of the GFP coding region) to prnD to produce IR-PRN-GFP (described in “Materials and Methods” and illustrated in Supplemental Fig. S1) and then administered this construct to plants. GFP fluorescence in these plants indicated that prnD was translated from IR-directed polycistronic mRNA and was not of plant origin. The protein prnD-GFP appeared to be secreted into the vacuole and to aggregate (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Expression of GFP in tomato plants harboring IR-PRN-GFP. Plant samples were taken 2 weeks after administration of the construct and examined under a confocal microscope (see “Materials and Methods”). A, Picture taken after excitation for GFP fluorescence. B, Picture taken with a filter that masks GFP fluorescence (chlorophyll autofluorescence is in red). C, Picture taken without excitation. D, Superposition of the two top panels.

A series of controlled experiments indicated that all four genes of the PRN operon are required for PRN production in plants. Plants carrying IR-PRN with deletions in prnB (Fig. 5VII) or prnC (data not shown) did not produce PRN. Plants expressing IR-PRN-GFP did not produce PRN (probably due to inactivation of the GFP-fused protein PrnD). Plants in which PRN had been replaced by an irrelevant gene (GUS) or TYLCV-infected plants did not produce PRN (Fig. 5). Only the positive controls exhibited PRN (elution time of 27.9 min). PRN could not be detected by HPLC in fruits (Fig. 5IV), even though the fruit harbored IR-PRN-DNA (Fig. 1B), probably due to interference in expression.

Figure 5.

HPLC analysis of PRN in control tomato plants. I, Positive control (synthetic PRN). II, positive control. Extract of roots from plants carrying IR-PRN (same as in Fig. 3AII). III, Extract of roots carrying IR-PRN-GFP. IV, Extract of fruits from a tomato plant carrying IR-PRN. V, Extract of plants carrying IR-GUS (GUS replacing PRN). VI, Extract of TYLCV-infected tomato. VII, Extract of plants carrying IR-PRN with a deletion in prnB. Black arrows mark the position of PRN elution. Dashed arrows mark the expected positions of the eluted PRN.

Generation of a Unique Phenotype: PRN-Expressing Plants Are Resistant to Damping-off Disease Caused by R. solani

Because PRN is inhibitory to R. solani and was produced in all plant tissues except fruits, the PRN-expressing plants were tested for resistance to damping-off disease of tomato caused by R. solani.

Young untreated and PRN-expressing tomato plants were planted in pots containing soil mixed with R. solani mycelium. The control plants, which did not express PRN, wilted within 2 weeks, whereas the PRN-expressing plants remained healthy (Fig. 6). Various PRN-producing bacteria have been tested by others for biological control of phytopathogens, but despite their potential antifungal activity, results have been inconsistent (e.g. Compant et al., 2005). In comparison, 80% to 100% of the PRN-expressing plants were protected from infection.

Figure 6.

PRN-expressing plants are resistant to damping-off disease. Left: IR-PRN was introduced into tomato seedlings which were then planted in noninfested soil. The plants were transferred to R. solani-infested soil 1 week after administration of IR-PRN. The picture was taken 2 weeks after R. solani infestation. A PRN-treated plant is shown on the left and a nontreated plant on the right. Right: IR-PRN was administered to tomato seedlings which were immediately planted in R. solani-infested soil. The group of plants on the right was PRN treated, and the group on the left consists of untreated plants. The picture was taken 5 d after planting.

PRN-Expressing Plants Produce Operon-Long Transcripts

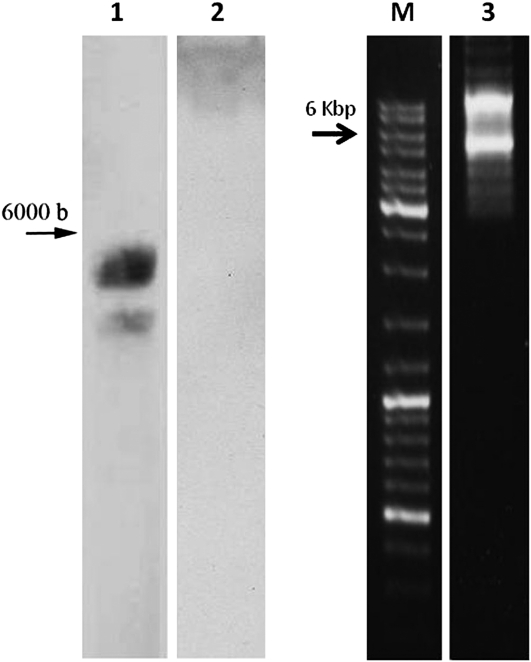

A true polycistronic mode of expression has not, to our knowledge, been demonstrated for eukaryotes. To determine whether the bacterial operon is correctly expressed in plants, we performed northern-blot analyses. Figure 7 (lanes 1 and 2) shows that the prn operon was transcribed into two long transcripts (the size of the major transcript is 5.5–6 kb, and the shorter one is approximately 4–5 kb, probably due to different termination signals).

Figure 7.

. IR-PRN is expressed as a long transcript. Lanes 1 and 2, Northern-blot analyses of RNA from IR-PRN-harboring plant (lane 1) and untreated plant (lane 2). A segment of prnA served as a probe. Lane 3, Long-distance PCR of cDNA reverse transcribed from ribosome-bound RNA. Primers for RT and PCR were from both ends of the prn operon (Supplemental Figs. S1 and 2 and Supplemental Table S1). M, Size markers.

In addition, we isolated polyribosomes from PRN-expressing plants, prepared cDNA from the ribosomal-bound RNA (as described in “Materials and Methods”), and amplified long cDNA (5–6 kb and p) by PCR with a PRN-specific primer (Fig. 7, lane 3). Two major cDNA species were observed: One was 5 to 6 kb long, and the other was longer (possibly due to incomplete 3′ trimming of the nascent transcript). Nevertheless, smaller-size prn transcripts were not detected, indicating a lack of further processing to monocistronic mRNAs. Hence, the polycistronic long transcript itself, rather than processed mature RNAs, served as the template for translation, as is the case in prokaryotes.

DISCUSSION

The IL-60 system provides a universal expression or silencing tool for all plants tested to date (Peretz et al., 2007). In this study, we report on IL-60-derived expression of a complete bacterial operon in tomato. We chose the prn operon (around 6 kb) of the rhizospheric biocontrol strain Pf-5 of P. fluorescens, which encodes the broad-range antifungal and antibacterial PRN (Loper et al., 2007; Gross and Loper, 2009) to investigate whether: 1) the IL-60 system can provide delivery and expression of this rather large bacterial operon in plants, 2) expression of the prn operon in plants leads to the appearance of a major unique metabolic trait manifested in the ability to produce a functionally active secondary metabolite (PRN), and 3) the ability to produce PRN increases resistance of the treated plants to root rot disease caused by the fungus R. solani used as a model plant pathogen.

Secondary metabolites are nonproteinaceous compounds that contribute to the molecular programs required for normal growth and development in plants. They serve as mediators in many metabolic pathways and contribute to plant interactions with the environment, some of which are modulated by plant hormones (Creelman and Mullet, 1997; Wasternack and Parthier, 1997; Loreti et al., 2008). Pigments and fragrance attract pollinators (Raguso, 2004; Grotewold, 2006) and are therefore essential for plant reproduction. At the same time, plant volatiles serve as repellents to herbivores (Gibson and Pickett, 1983; Francis et al., 2004), and, after infestation by a pest, alarm pheromones are emitted that attract natural enemies of that pest (Francis et al., 2004). Plant secondary metabolites also participate in the elicitation of induced resistance to pathogens and pests (Fawcett and Spencer, 1966; Baily, 1982; Walling, 2009). Plants produce a plethora of secondary metabolites that are major ingredients in a wealth of potentially economically valuable substances such as pharmaceuticals, food additives, fragrances, natural pesticides, and more (Morant et al., 2007). However, the production of these metabolites from plants and plant cultures has not yet seen the transition from economic potential to commercial success (Hadacek, 2002; Zhang et al., 2004). Numerous approaches have been attempted to improve the yield of a desired metabolite to a commercially relevant level; metabolic engineering employs genetic engineering techniques to increase production by enhancing gene expression, manipulating a gene's regulatory system (usually transcription factors), preventing branching off to another pathway by down-regulating the competing enzyme, and minimizing catabolism (Verpoorte et al., 1999; Verpoorte and Memelink, 2002).

Here, plants expressing the native bacterial prn operon cloned to the IL-60 platform were shown to produce physiological amounts of the secondary metabolite PRN, sufficient to engender a unique phenotype, without any additional manipulation. PRN production after administration of the prn operon to tomato was at the pmol/mg fresh tissue level (Fig. 3), a biologically active level that indeed induced the appearance of a unique phenotype. The obtained IL-60-PRN construct is transcribed into a polycistronic mRNA, which serves as a template for translation; therefore, it can be defined as an operon. An entire metabolic pathway is expressed, producing the secondary metabolite PRN. Operon-type expression was demonstrated by the appearance of operon-long transcripts, an apparent lack of further processing of those transcripts, the ribosome-bound PRN transcripts being of a size compatible with a full-length polycistronic RNA, and the last gene of the operon indeed being transcribed and translated from an IR-directed transcript. Translation into a polyprotein that would be further processed to maturity and biological activity is inconceivable because of the presence of stop codons and intergenic spaces and because of the fact that not all ORFs are at the same translation frame.

A plant RBS is present on the IR-PRN construct upstream of prnA. However, the issue of plant ribosome recognition of the other RBSs, in front of each of the downstream ORFs, is currently under study. Mutational analyses clearly demonstrated that expression of all of the operon’s genes is required for production of the end product PRN. Taken together, these results indicate that under the control of the IL-60 platform, a plant can express an entire metabolic pathway from an operon in a polycistronic manner. To our knowledge, this is the first report indicating that polycistronic mRNA in a eukaryotic system is a template for translation rather than a pre-mRNA that is further processed to smaller mRNAs.

Operon transformation mediated by the IL-60 system presents several advantages over plastid transformation, as described by other authors (Elghabi et al., 2011; Sanz-Barrio et al., 2011; Wei et al., 2011). A comparison between the two operon-expression systems in plants indicates that: 1) the IL-60 system is not transgenic while plastid transformation produces transgenic plants, 2) preparation and handling of the IL-60 system is much simpler than plastid transformation protocols, and 3) IL-60 delivery into plants circumvents the need to use selectable markers. It is conceivable that further manipulation of any of the pathway's signals and genes may elevate the level of PRN production to match that of other manipulated native secondary metabolites.

The obtained resistance to root rot disease presents an obvious potential advantage of PRN-producing crops over various PRN-producing bacteria, which have been tested by others for biological control of phytopathogens; despite their potential antifungal activity, results have been inconsistent, probably due to the diversity of environmental niches and sensitivity of PRN to environmental factors such as UV light (Compant et al., 2005). In comparison, 80% to 100% of the PRN-expressing plants were protected from infection. It seems that when expressed within plant tissues, PRN is protected from the external environment, it is continuously produced, and it does not need to diffuse into the infected tissue to inhibit the invading pathogen. This may explain the appearance of a unique efficiently resistant phenotype in our plant system. It is worth noting that PRN was found in different parts of the treated plants but not in fruits. Because the operon itself is present in fruits, it is assumed that some conditions/compounds in tomato fruits modify, destroy, or are antagonist to PRN activity. This needs to be further investigated.

CONCLUSION

The ability to express an entire metabolic pathway in plants opens a potentially unique way of manipulating secondary metabolite levels and production. Once the regulatory elements enabling a polycistronic mode of expression are further elucidated, nonplant metabolites of commercial importance can potentially be biofarmed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vectors, Their Administration to Plants, and Molecular Procedures

Molecular procedures were carried out according to standard protocols (Sambrook and Russel, 2001). The RiboRuler high-range RNA ladder (Fermentas) was used to determine the size of RNA bands in northern-blot analyses. IL-60-BS was described by Peretz et al. (2007). The IR segment of TYLCV and the following 166 bp of ORF V2 were PCR-amplified with added KpnI and PstI restriction sites and cloned into the plasmid pDrive (Qiagen). The PRN Operon (GenBank accession no. CP000076.1; bases 4,157,074–4,162,815) was inserted into the same plasmid downstream of IR-V2 between the BamHI and XbaI sites. The construct was designated IR-PRN. In another construct, the gene for GFP was fused to prnD of IR-PRN. A clone of tobacco mosaic virus with GFP of improved fluorescence (30B-GFP3; Shivprasad et al., 1999) was obtained from Dr. William O. Dawson (University of Florida, Lake Alfred). The coding region of GFP was amplified with primers 1,334 and 1,335 (Supplemental Table S1) carrying restriction sites for BglII and NdeI. Inverse PCR of IR-PRN, starting at both ends of the stop codon of prnD, was performed with primers 1,332 and 1,333 carrying restriction sites matching those of the GFP primers. After ligation, the obtained construct carried IR, part of V2, PRN (without the prnD stop codon), and the coding region of GFP (initiation ATG was deleted). This enabled the translation of a fused, continuous, prnD-GFP protein. The various constructs are illustrated in Supplemental Figure S1. Deletion in prnB was done by cleaving with AjiI and religating. Deletion in prnC was done by cleaving with ScaI and religating.

Polyribosomes were prepared as described by Nur et al. (1995). A cDNA library was prepared from polyribosomal RNA using a Smart cDNA construction kit (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primer for RT was 5′-GCCAGATAGTCATGAATACCTCGCAAAGAG-3′.

Extraction of PRN from Plant Tissue, HPLC, and LC-MS Analyses

Plant tissue (4 g) was taken for each extraction. The protein content in each extract was determined separately. The plant tissue was homogenized in chloroform, and the homogenate was kept at 4°C for at least 24 h. The mixture was filtered through Miracloth followed by 10 min of centrifugation at 3,000g. The supernatant fluid was mixed with an equal volume of 0.1 m K2HPO4, and after phase separation, the aqueous fraction was discarded. The chloroform fraction was rota-evaporated, and the resultant dry material was dissolved in 100 μL of acetonitrile. Approximately 30 μL of the extract (equivalent to 70 μg of protein in the initial plant extract) was subjected to HPLC separation. HPLC was performed on a 100 RP-18 column (Merck, Lichrospher, 15 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm). Elution was done in 45% H2O:30% acetonitrile (GC grade) and 25% methanol or in 65% H2O:35% acetonitrile. Flow rate was 1 mL/min, and detection was at 225 nm.

In addition, LC-MS analyses were performed on plant extracts. HPLC analysis was performed on an Accela High Speed LC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which consists of an Accela pump, autosampler, and PDA detector. The Accela LC system was coupled with the LTQ Orbitrap Discovery hybrid FT mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) equipped with an electrospray ionization ion source. The mass spectrometer was operated in negative ionization mode, with the following ion source parameters: spray voltage, 3.5 kV; capillary temperature, 250°C; and capillary voltage, −35 V; source fragmentation was disabled; sheath gas rate (arb), 30; and auxiliary gas rate, 10. Mass spectra were acquired in the mass-to-charge ratio range of 150 to 2,000 D. The LC-MS system was controlled, and data were analyzed using Xcalibur software (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). The presence of PRN in the sample was confirmed by high-resolution LC-MS analysis (measured mass, 254.97284 D; calculated atomic composition of deprotonated pseudomolecular ion C10H5O2N235Cl2, error −2.0 μg mL−1).

Bioassay for Inhibition of Rhizoctonia solani in Vitro

R. solani was cultured on potato dextrose agar at 28°C. A disk (30 mm in diameter) of R. solani-containing agar was transferred to another petri dish containing potato dextrose agar and 10 μL of HPLC elution buffer (negative control), 10 μL of various plant extracts, or 10 μL containing 0.2 μg of synthetic PRN in elution buffer (Sigma, positive control). Inhibition of fungal growth was determined after incubation at 28°C for 3 d.

Assay for R. solani Resistance

Roots of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) seedlings were immersed in a water solution of IL-60-BS and IR-PRN or IR-PRN-GFP (1 μg/plantlet) until the entire solution was sucked up by the plants. The plants were then potted and kept in the greenhouse at 24°C. Tomato seedlings, 2 weeks after application of IL-60-BS and IR-PRN, were transferred to pots with 0.5 kg of soil mixed with 0.5 g of R. solani mycelium. Control plants (not carrying PRN) were similarly treated. Plants were kept for 2 to 3 weeks at 24°C until symptom appearance.

Confocal Microscopy

Tomato leaf sections, after peeling away the epidermis, were observed under the confocal microscope (Zeiss 100M). Excitation was at 488 nm. GFP emission was detected at 505 to 550 nm. Autofluorescence of chlorophyll was detected at wavelengths greater than 560 nm. Data were processed by the built-in program LSM 51.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Illustration of constructs used in this study.

Supplemental Figure S2. Alignment of primers along the PRN operon.

Supplemental Table S1. List of primers for PCR analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Joyce Loper (Oregon State University at Corvallis) for providing Pseudomonas fluorescens strain Pf-5 and Julius Ben-Ari (Interdepartmental Service Unit, The Robert H. Smith Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environment, Hebrew University of Jerusalem) for help with the HPLC and LC/MS analyses.

References

- Amoutzias G, Van de Peer Y. (2008) Together we stand: genes cluster to coordinate regulation. Dev Cell 14: 640–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arima K, Imanaki H, Kousaka M, Fukuta A, Tamura G. (1964) Pyrrolnitrin, a new antibiotic substance, produced by Pseudomonas. Agric Biol Chem 28: 575–576 [Google Scholar]

- Baily JA. (1982) Mechanisms of phytoalexine accumulation. In Mansfield, ed, Phytoalexins. Blackie, Glasgow, pp 289–318 [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shahar Y, Nannapaneni K, Casavant TL, Scheetz TE, Welsh MJ. (2007) Eukaryotic operon-like transcription of functionally related genes in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 222–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal T. (2004) Operons in eukaryotes. Brief Funct Genomics Proteomics 3: 199–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal T, Evans D, Link CD, Guffanti A, Lawson D, Thierry-Mieg J, Thierry-Mieg D, Chiu WL, Duke K, Kiraly M, et al. (2002) A global analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans operons. Nature 417: 851–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhead KD, Schisler DA, Slininger PJ. (1994) Pyrrolnitrin production by biological control agent pseudomonas cepacia B37w in culture and in colonized wounds of potatoes. Appl Environ Microbiol 60: 2031–2039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernin L, Brandis A, Ismailov Z, Chet I. (1996) Pyrrolnitrin production by an Enterobacter agglomerans strain with a broad spectrum of antagonistic activity towards fungal and bacterial phytopathogens. Curr Microbiol 32: 208–212 [Google Scholar]

- Compant S, Duffy B, Nowak J, Clément C, Barka EA. (2005) Use of plant growth-promoting bacteria for biocontrol of plant diseases: principles, mechanisms of action, and future prospects. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 4951–4959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creelman RA, Mullet JE. (1997) Biosynthesis and action of jasmonates in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 48: 355–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descombes P, Schibler U. (1991) A liver-enriched transcriptional activator protein, LAP, and a transcriptional inhibitory protein, LIP, are translated from the same mRNA. Cell 67: 569–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Banna N, Winkelmann G. (1998) Pyrrolnitrin from Burkholderia cepacia: antibiotic activity against fungi and novel activities against streptomycetes. J Appl Microbiol 85: 69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elghabi Z, Ruf S, Bock R. (2011) Biolistic co-transformation of the nuclear and plastid genomes. Plant J 67: 941–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolaeva MD, White O, Salzberg SL. (2001) Prediction of operons in microbial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 1216–1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett CH, Spencer DM. (1966) Antifungal compounds in apple fruit infected with Sclerotinia fructigena. Nature 211: 548–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field B, Osbourn AE. (2008) Metabolic diversification: independent assembly of operon-like gene clusters in different plants. Science 320: 543–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis F, Lognay G, Haubruge E. (2004) Olfactory responses to aphid and host plant volatile releases: (E)-β-farnesene an effective kairomone for the predator Adalia bipunctata. J Chem Ecol 30: 741–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Ríos M, Fujita T, LaRosa PC, Locy RD, Clithero JM, Bressan RA, Csonka LN. (1997) Cloning of a polycistronic cDNA from tomato encoding γ-glutamyl kinase and γ-glutamyl phosphate reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 8249–8254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson RW, Pickett JA. (1983) Wild potato repels aphids by release of aphid alarm pheromone. Nature 302: 608–609 [Google Scholar]

- Gierl A, Frey M. (2001) Evolution of benzoxazinone biosynthesis and indole production in maize. Planta 213: 493–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierman HJ, Indemans MHG, Koster J, Goetze S, Seppen J, Geerts D, van Driel R, Versteeg R. (2007) Domain-wide regulation of gene expression in the human genome. Genome Res 17: 1286–1295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross H, Loper JE. (2009) Genomics of secondary metabolite production by Pseudomonas spp. Nat Prod Rep 26: 1408–1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotewold E. (2006) The genetics and biochemistry of floral pigments. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57: 761–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadacek F. (2002) Secondary metabolites as plant traits: current assessment and future perspectives. Crit Rev Plant Sci 21: 273–322 [Google Scholar]

- Halpin C. (2005) Gene stacking in transgenic plants: the challenge for 21st century plant biotechnology. Plant Biotechnol J 3: 141–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer PE, Burd W, Hill DS, Ligon JM, van Pée K-H. (1999) Conservation of the pyrrolnitrin biosynthetic gene cluster among six pyrrolnitrin-producing strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett 180: 39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardison R, Slightom JL, Gumucio DL, Goodman M, Stojanovic N, Miller W. (1997) Locus control regions of mammalian β-globin gene clusters: combining phylogenetic analyses and experimental results to gain functional insights. Gene 205: 73–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DS, Stein JI, Torkewitz NR, Morse AM, Howell CR, Pachlatko JP, Becker JO, Ligon JM. (1994) Cloning of genes involved in the synthesis of pyrrolnitrin from pseudomonas fluorescens and role of pyrrolnitrin synthesis in biological control of plant disease. Appl Environ Microbiol 60: 78–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst LD, Pál C, Lercher MJ. (2004) The evolutionary dynamics of eukaryotic gene order. Nat Rev Genet 5: 299–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob F, Monod J. (1961) Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. J Mol Biol 3: 318–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonczyk R, Schmidt H, Osterrieder A, Fiesselmann A, Schullehner K, Haslbeck M, Sicker D, Hofmann D, Yalpani N, Simmons C, et al. (2008) Elucidation of the final reactions of DIMBOA-glucoside biosynthesis in maize: characterization of Bx6 and Bx7. Plant Physiol 146: 1053–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalbe C, Marten P, Berg G. (1996) Strains of the genus Serratia as beneficial rhizobacteria of oilseed rape with antifungal properties. Microbiol Res 151: 433–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamensky M, Ovadis M, Chet I, Chernin L. (2003) Soil-borne strain IC14 of Serratia plymuthica with multiple mechanisms of antifungal activity provides biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum diseases. Soil Biol Biochem 35: 323–331 [Google Scholar]

- Kingston RE, Narlikar GJ. (1999) ATP-dependent remodeling and acetylation as regulators of chromatin fluidity. Genes Dev 13: 2339–2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirner S, Hammer PE, Hill DS, Altmann A, Fischer I, Weislo LJ, Lanahan M, van Pée K-H, Ligon JM. (1998) Functions encoded by pyrrolnitrin biosynthetic genes from Pseudomonas fluorescens. J Bacteriol 180: 1939–1943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. (1983) Comparison of initiation of protein synthesis in procaryotes, eucaryotes, and organelles. Microbiol Rev 47: 1–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loper JE, Kobayashi DY, Paulsen IT. (2007) The genomic sequence of pseudomonas fluorescens pf-5: insights into biological control. Phytopathology 97: 233–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreti E, Povero G, Novi G, Solfanelli C, Alpi A, Perata P. (2008) Gibberellins, jasmonate and abscisic acid modulate the sucrose-induced expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in Arabidopsis. New Phytol 179: 1004–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugtenberg B, Kamilova F. (2009) Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 63: 541–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morant AV, Jørgensen K, Jørgensen B, Dam W, Olsen C, Møller B, Bak S. (2007) Lessons learned from metabolic engineering of cyanogenic glucosides. Metabolomics 3: 383–398 [Google Scholar]

- Nur T, Sela I, Webster NJ, Madar Z. (1995) Starvation and refeeding regulate glycogen synthase gene expression in rat liver at the posttranscriptional level. J Nutr 125: 2457–2462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovadis M, Liu X, Gavriel S, Ismailov Z, Chet I, Chernin L. (2004) The global regulator genes from biocontrol strain Serratia plymuthica IC1270: cloning, sequencing, and functional studies. J Bacteriol 186: 4986–4993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretz Y, Mozes-Koch R, Akad F, Tanne E, Czosnek H, Sela I. (2007) A universal expression/silencing vector in plants. Plant Physiol 145: 1251–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W, Zhang J. (2008) Evolutionary dynamics of nematode operons: easy come, slow go. Genome Res 18: 412–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raguso RA. (2004) Why are some floral nectars scented? Ecology 85: 1486–1494 [Google Scholar]

- Ramji DP, Foka P. (2002) CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins: structure, function and regulation. Biochem J 365: 561–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado H, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, Smith TF, Collado-Vides J. (2000) Operons in Escherichia coli: genomic analyses and predictions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6652–6657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russel DW. (2001) Molecular Cloning, Ed 3. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Barrio R, Millán AF-S, Corral-Martínez P, Seguí-Simarro JM, Farran I. (2011) Tobacco plastidial thioredoxins as modulators of recombinant protein production in transgenic chloroplasts. Plant Biotechnol J 9: 639–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimura K, Okada A, Okada K, Jikumaru Y, Ko K-W, Toyomasu T, Sassa T, Hasegawa M, Kodama O, Shibuya N, et al. (2007) Identification of a biosynthetic gene cluster in rice for momilactones. J Biol Chem 282: 34013–34018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivprasad S, Pogue GP, Lewandowski DJ, Hidalgo J, Donson J, Grill LK, Dawson WO. (1999) Heterologous sequences greatly affect foreign gene expression in tobacco mosaic virus-based vectors. Virology 255: 312–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadaro D, Gullino ML. (2005) Improving the efficacy of biocontrol agents against soilborne pathogens. Crop Prot 24: 601–613 [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Manrique RP, González-Cabo P, Ortiz-Martín I, Ros S, Baylis HA, Palau F. (2007) The frataxin-encoding operon of Caenorhabditis elegans shows complex structure and regulation. Genomics 89: 392–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verpoorte R, Memelink J. (2002) Engineering secondary metabolite production in plants. Curr Opin Biotechnol 13: 181–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verpoorte R, van der Heijden R, ten Hoopen HJG, Memelink J. (1999) Metabolic engineering of plant secondary metabolite pathways for the production of fine chemicals. Biotechnol Lett 21: 467–479 [Google Scholar]

- Walling LL. (2009) Adaptive defense responses to pathogens and insects. Adv Bot Res 51: 551–612 [Google Scholar]

- Wang H-H, Yin W-B, Hu Z-M. (2009) Advances in chloroplast engineering. J Genet Genomics 36: 387–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C, Parthier B. (1997) Jasmonate-signaled plant gene expression. Trends Plant Sci 2: 302–307 [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Liu Y, Lin C, Wang Y, Cai Q, Dong Y, Xing S. (2011) Transformation of alfalfa chloroplasts and expression of green fluorescent protein in a forage crop. Biotechnol Lett 33: 2487–2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller DM, Raaijmakers JM, Gardener BBM, Thomashow LS. (2002) Microbial populations responsible for specific soil suppressiveness to plant pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol 40: 309–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welm AL, Timchenko NA, Darlington GJ. (1999) C/EBPalpha regulates generation of C/EBPbeta isoforms through activation of specific proteolytic cleavage. Mol Cell Biol 19: 1695–1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka R, Kim G-D, Radomska HS, Lekstrom-Himes J, Smith LT, Antonson P, Tenen DG, Xanthopoulos KG. (1997) CCAAT/enhancer binding protein epsilon is preferentially up-regulated during granulocytic differentiation and its functional versatility is determined by alternative use of promoters and differential splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 6462–6467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihisa H, Zenji S, Fukushi H, Katsuhiro K, Haruhisa S, Takahito S. (1989) Production of antibiotics by Pseudomonas cepacia as an agent for biological control of soilborne plant pathogens. Soil Biol Biochem 21: 723–728 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Franco C, Curtin C, Conn S. (2004) To stretch the boundary of secondary metabolite production in plant cell-based bioprocessing: anthocyanin as a case study. J Biomed Biotechnol 2004: 264–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.