Abstract

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is a cAMP-regulated chloride channel localized primarily at the apical surfaces of epithelial cells lining airway, gut and exocrine glands, where it is responsible for transepithelial salt and water transport. Several human diseases are associated with an altered channel function of CFTR. Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by the loss or dysfunction of CFTR-channel activity resulting from the mutations on the gene; whereas enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas are caused by the hyperactivation of CFTR channel function. CFTR is a validated target for drug development to treat these diseases. Significant progress has been made in developing CFTR modulator therapy by means of high-throughput screening followed by hit-to-lead optimization. Several oral administrated investigational drugs are currently being evaluated in clinical trials for CF. Also importantly, new ideas and methodologies are emerging. Targeting CFTR-containing macromolecular complexes is one such novel approach.

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

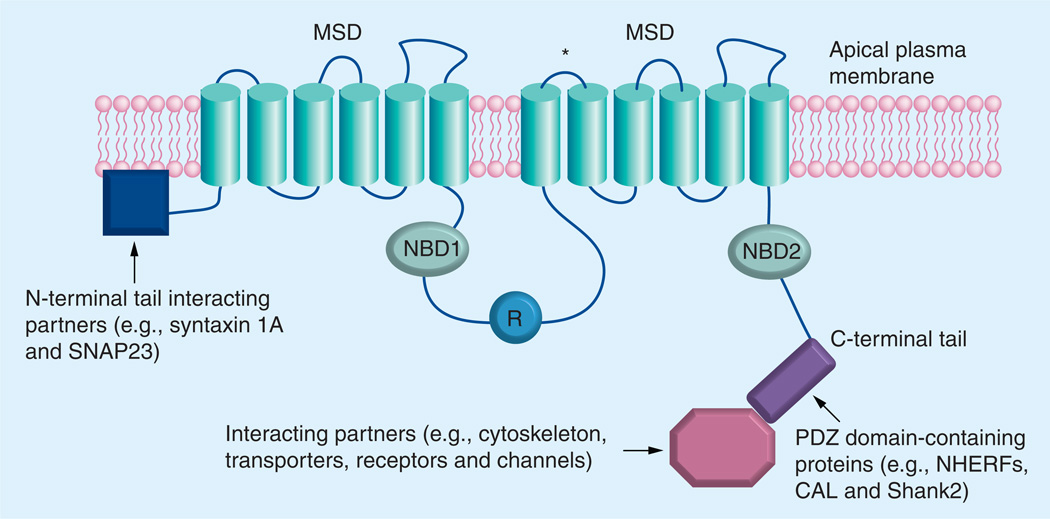

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is a cAMP-regulated chloride (Cl−) channel localized primarily at the apical surfaces of epithelial cells lining airway, gut, and exocrine glands, where it is responsible for transepithelial salt and water transport [1–3]. CFTR is a member of the ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily and consists of two repeated motifs, each composed of a six-helix membrane-spanning domain and a cytosolic nucleotide binding domain (NBD), which can bind to and hydrolyze ATP. These two identical motifs are linked by a cytoplasmic regulatory (R) domain that contains multiple consensus phosphorylation sites (Figure 1). The CFTR Cl− channel can be activated through phosphorylation of the R domain by various protein kinases (e.g., cAMP-dependent protein kinase A, protein kinase C and cGMP-dependent protein kinase II) and by ATP binding to, and hydrolysis by, the NBD domains. Both the amino (NH2) and carboxyl (COOH) terminal tails of CFTR are cytoplasmically oriented and mediate the interaction between CFTR and a wide variety of binding proteins (Figure 1). The high-resolution 3D structures of wild-type (WT) or mutant CFTR have not been determined. Some structural studies on the subdomain of CFTR (e.g., NBD1) using x-ray crystallography and NMR [4,5], and on full-length CFTR using homology-based models [6,7], have been published.

Figure 1. The putative domain structure of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and its interaction with various binding partners.

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is composed of two repeated motifs; each consists of a six-helix MSD and a NBD. These two motifs are linked by a cytoplasmic regulatory (R) domain, which contains multiple consensus phosphorylation sites. The CFTR chloride channel can be activated by phosphorylation of the R domain and by ATP binding to, and hydrolysis by, the NBDs. Both the amino and carboxyl terminal tails mediate the interaction between CFTR and a wide variety of binding partners. The asterisk denotes the glycosylation sites.

MSD: membrane spanning domain; NBD: Nucleotide binding domain.

Modified from [59].

More than 1600 mutations have been identified on CFTR gene, which can be roughly grouped into six categories. The Class I mutations constitute nonsense, splice and frame shift mutants that encode truncated forms of CFTR (e.g., G542X and 394delTT). These premature stop mutations are found in 10% of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients worldwide. The Class II mutations are mostly processing mutants that get trapped in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and targeted for degradation. ΔF508-CFTR is the most prevalent Class II mutant. Approximately 90% of CF patients carry ΔF508 on at least one allele. The Class III (regulation mutants; e.g., G551D) and Class IV (permeation mutants; e.g., R117H) are mutants that decrease the open probability (Po) of CFTR channel (impaired gating) or reduce its ability to transport Cl− (altered conductance), consequently leading to partial loss of the channel function. The class V mutations show reduced mRNA stability (e.g., 3849+10kbC→T). The Class VI mutations, proposed by Lukacs and colleagues, include C-terminal truncated CFTRs, which form unstable mature protein with five- to six-fold faster degradation rate than WT-CFTR [8].

Several human diseases result from an altered function of CFTR Cl− channel, among which CF and enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas are the two major disorders [9,10].

Cystic fibrosis

CF is a lethal autosomal recessive inherited disease that is caused by the loss or dysfunction of the CFTR Cl− channel activity resulting from the mutations [11,12]. The absence or dysfunction of CFTR Cl− channel leads to aberrant ion and fluid homeostasis at epithelial surfaces where it is normally expressed. Clinically, chronic lung disease is the main cause of morbidity and mortality for CF patients. Other symptoms include, but are not limited to, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and the resultant meconium ileus, elevated sweat electrolytes, and male infertility [13]. In the lung, the defect in Cl− transport (thus fluid secretion) is coupled with the hyperabsorption of sodium (Na+) and fluid, leading to the generation of thick and dehydrated mucus and subsequent chronic bacterial infections (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa). This causes bronchiectasis and progressive airway destruction, eventually leading to the loss of pulmonary function [13].

Current therapies to treat CF lung disease mainly target the downstream disease consequences (symptoms) that are secondary to the loss of CFTR channel function (the ‘root cause’ of the disease) including mucolytics, anti-infective agents, anti-inflammatory agents and lung transplantation [14].

Enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas

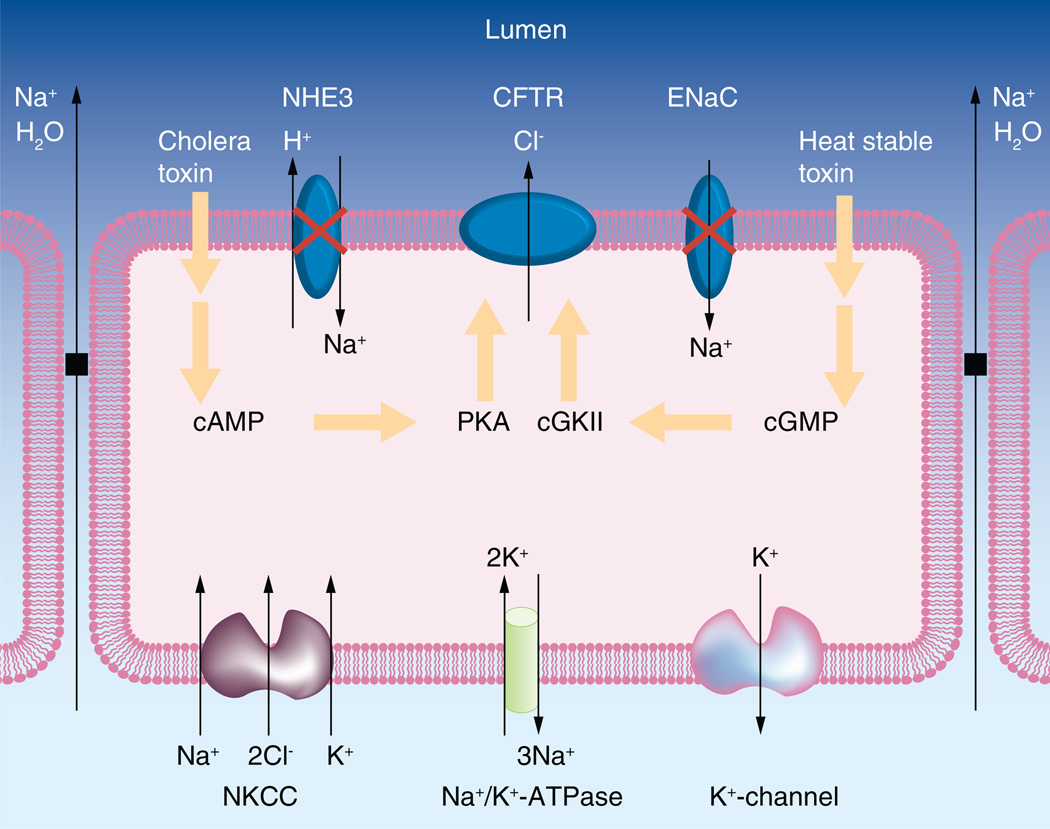

Secretory diarrhea is another major dysfunction involving the hyperactivation of CFTR in the GI tract [15]. CFTR is expressed at the apical surfaces of secretory epithelial cells lining the lumen of the gut. When the gut lumen is exposed to toxins secreted by the colonizing pathogenic microorganisms (e.g., Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, Yersinia enterocolitica, Shigella flexneri and Salmonella typhimurium), the intracellular second messengers (cAMP and/or cGMP) are excessively produced, leading to the hyperactivation of CFTR channel. The resulting transepithelial Cl− secretion increases the electrical and osmotic driving forces for the parallel flows of Na+ and water. In parallel, the fluid absorption process mediated by Na+/H+ exchangers (e.g., NHE3) and epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) are inhibited. Therefore, the net result is the robust transepithelial secretion of fluid and electrolytes into the intestine lumen and, subsequently, large amount of fluid entering the colon, which overwhelms its reabsorbing capacity, leading to fluid loss and dehydration, which can be fatal if untreated (Figure 2). Until now, the mainstay of therapy in secretory diarrheas has been the oral rehydration therapy (ORT).

Figure 2. A model depicting enterotoxin-induced and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-mediated transepithelial chloride and fluid secretion, which causes secretory diarrheas.

The cholera toxin or the heat stable toxin induces the elevation of intracellular cAMP or cGMP levels, leading to excessive phosphorylation of the R domain of CFTR by PKA- or cGKII and hyperactivation of CFTR channel to secrete chloride into the lumen. As a consequence, Na+ and water are effluxed into the lumen through the paracellular transport mechanism. In parallel, the electroneutral absorption of Na+ mediated by NHEs (e.g., NHE3) and the electrogenic absorption of Na+ mediated by the ENaC are inhibited. Therefore, the net result is the secretion of large amount of fluid into the luminal side of intestine and, consequently, large amount of fluid enters the colon, which overwhelms its absorptive capacity and causes diarrheas.

CFTR: Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; cGKII: cGMP-dependent protein kinase II; ENaC: Epithelial sodium channel; NHE: Na+/H+ exchanger; NKCC: Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter.

Modified from [59].

The purpose of this review

The purpose of this review is to summarize the most significant progress in targeting CFTR for treating CF and enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas, with focus on agents that have been extensively characterized or have been tested in clinical trials and particularly on the emerging ideas and approaches in identification of novel therapeutic targets and agents for CFTR modulators discovery.

Targeting CFTR for therapy of cystic fibrosis

Since the median predicted survival age for CF patients is currently in the mid-30s [101], there is an urgent need for developing more efficacious therapies that address the underlying defect of CF. Development of small-molecule agents that increase CFTR channel function could, in principle, cure the ‘root cause’ of CF or slow the progression of the disease. In the last two decades, extensive efforts have been made in the development of small-molecule CFTR modulators. The most successful approach so far has been high-throughput screening (HTS) of chemical libraries followed by extensive hit-to-lead chemical optimization. Some excellent reviews have been published in recent years on the discovery of CFTR modulators [14,16,17]. This paper will focus particularly on the new approaches and ideas emerging in this field, and the agents, which have entered clinical trials.

CFTR modulators include activators, potentiators, correctors and inhibitors (blockers). CFTR activators are agents that can stimulate CFTR channel function by means of increasing intracellular cAMP/cGMP levels. CFTR potentiators are agents that can increase the channel gating activity of cell-surface localized CFTR, thus, enhancing its ion transport capability. CFTR correctors act by increasing the amount of functional CFTR at the cell surface, resulting in enhanced ion transport. These three types of CFTR modulators are developed for treating CF. CFTR inhibitors are agents that can decrease CFTR Cl− channel function and are developed for treating enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas and polycystic kidney disease (PKD) [14,17].

CFTR modulators in clinical trials

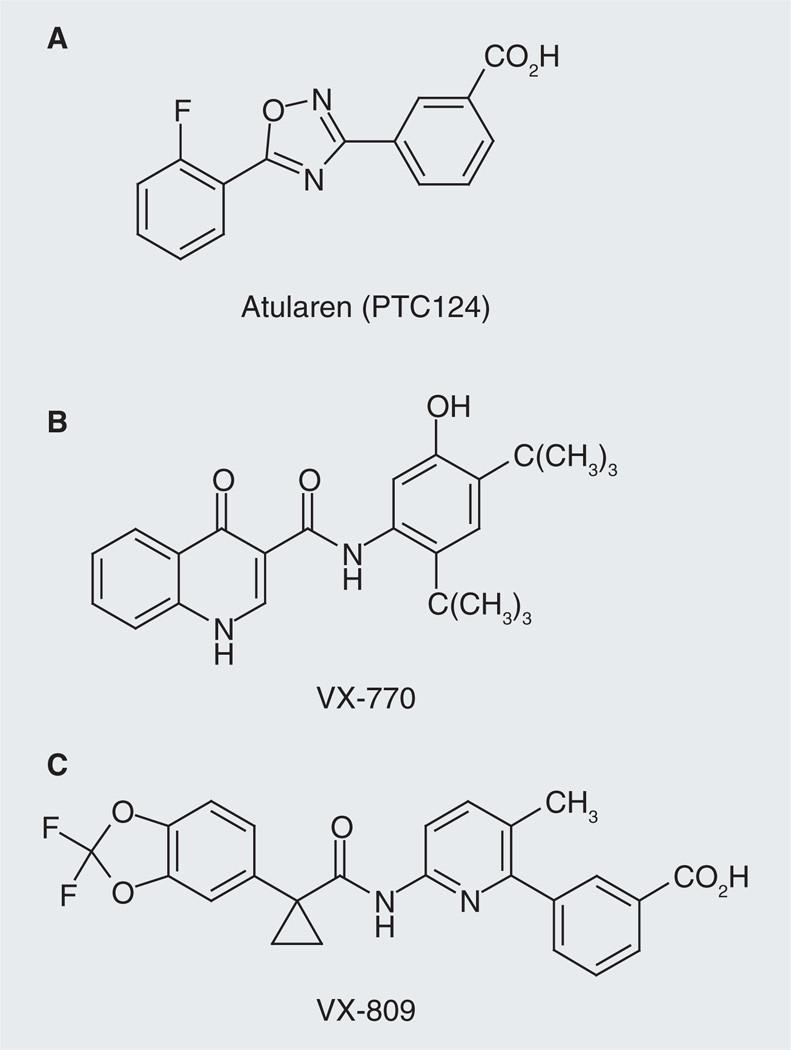

Three orally administered investigational CFTR modulators are currently being evaluated in clinical studies: Atularen (PTC124®; CFTR corrector), VX-770 (CFTR potentiator) and VX-809 (CFTR corrector).

Atularen (Figure 3A) is an orally bioavailable small molecule that can induce ribosomes to read through premature stop codons during mRNA translation. Nonsense mutations are responsible for approximately 10% of CF cases worldwide and more than 50% in Israel [18]. In a Phase IIa trial in adult CF patients who had at least one nonsense mutation in CFTR gene, oral administration of Atularen in two 28-day cycles was generally well tolerated and caused the production of functional CFTR and significant improvements in CFTR-mediated total Cl− transport as assessed by transepithelial nasal potential difference in the nasal airways [19]. Atularen is now being evaluated in a Phase III trial in CF patients aged 6 and older who have a nonsense mutation [102].

Figure 3. Three cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators in clinical trials.

(A) Atularen is now being evaluated in a Phase III trial in cystic fibrosis patients aged 6 and above, who have a nonsense mutation. (B) VX-770 is a cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator potentiator, which was tested to treat CF patients with at least one copy of the G551D mutation. VX-770 has been approved by the US FDA for treatment of CF patients aged 6 and older with G551D mutation. (C) VX-809 is a CFTR corrector. Plans have been disclosed for evaluating VX-809 in combination with VX-770 in a Phase II clinical trial in patients carrying at least one copy of ΔF508 mutation.

VX-770 (Figure 3B) was identified from HTS followed by lead optimization [20]. VX-770 was shown to potentiate FSK-stimulated and CFTR-mediated Isc in recombinant Fisher rat thyroid (FRT) cells expressing G551D- or ΔF508-CFTR with an EC50 value of 100 ± 47 nM (~fourfold increase) and 25 ± 5 nM (~sixfold increase; ΔF508-CFTR was temperature corrected prior to potentiation). Biophysically, it was found that VX-770 acts by increasing CFTR channel Po in excised membrane patches from these recombinant cells (G551D: ~sixfold; WT: twofold; ΔF508: ~fivefold). VX-770 was also shown to increase FSK-induced and CFTR-mediated Isc in primary cultures of G551D/ΔF508 human bronchial epithelia (HBE) by tenfold (equivalent of 48 ± 4% of non-CF HBE) with an EC50 value of 236 ± 200 nM. In ΔF508 HBE isolated from three of the six ΔF508-homozygous CF patients, VX-770 significantly increased the FSK-stimulated Isc with a maximum response equivalent to 16 ± 4% of non-CF HBE and a mean EC50 of 22 ± 10 nM. Moreover, it was found that the increase in CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion by VX-770 caused a secondary decrease in ENaC-mediated Na+ absorption and consequently increased the airway surface liquid volume and cilia beating in G551D/ΔF508 HBE [21]. These studies provide evidence to support the hypothesis that drugs that aimed to restore or increase CFTR channel function can rescue epithelial cell function in human CF airway and have the potential for therapy. VX-770 had been tested in Phase III trials in pediatric and adult CF patients with at least one copy of the G551D mutation (a Class III mutation) in their CFTR gene. No safety issues were found in these trials. The treatment groups met the primary endpoint for improved lung function and secondary endpoints of reduced pulmonary exacerbations, increase in body weight and quality of life measures [103]. ‘VX-770 has been approved by the US FDA to treat CF patients aged 6 or older with G551D mutation. In addition, studies have been planned to test VX-770 in children (2–5 years old) with G551D mutation and in CF patients with other Class III gating mutations besides G551D [104].

VX-809 (Figure 3C) was also discovered through the approach of HTS followed by lead optimization [22]. It was shown that, in recombinant FRT cells, VX-809 (48 h preincubation) improved ΔF508-CFTR maturation by 7.1 ± 0.3-fold (EC50 = 0.1 ± 0.1 µM) and increased ΔF508-CFTR-mediated Isc by approximately fivefold (EC50 = 0.5 ± 0.1 µM). In cultured HBE cells isolated from the lungs of seven CF patients homozygous for ΔF508-CFTR mutation (ΔF508-HBE), VX-809 (48 h preincubation) increased CFTR maturation by ~eightfold (EC50 = 350 ± 180 nM) and CFTR-mediated Isc by fourfold (EC50 = 81 ± 19 nM), equivalent to ~14% of non-CF HBE. Moreover, it was found that VX-809-corrected ΔF508-CFTR exhibited biochemical and functional characteristics similar to WT-CFTR and that VX-809 showed selectivity for correction of CFTR processing [22]. It is also of importance that it was found that acute application of VX-770 could increase FSK-induced Isc in cultured ΔF508-HBE pretreated with VX809 to the level ~25% of that measured in non-CF HBE cells and further increased the airway surface liquid height in these cells, providing the rational of combining CFTR correctors and potentiators as one strategy for CF therapy [22]. Mechanistic studies suggest that VX-809 acts by directly interacting with ΔF508-CFTR and/or CFTR-associated proteins and promoting its proper folding during its biogenesis and processing in ER [22]. A 28-day Phase IIa trial of VX-809 in CF patients who have the ΔF508 mutation showed that VX-809 was well tolerated and led to a significant decrease in sweat Cl− level (8 mmol/l drop). However, no changes in clinical endpoints such as lung function were observed [23,105].

Plans have been disclosed for evaluating VX-770 in combination with VX-809 in a Phase IIa clinical trial in patients carrying at least one copy of ΔF508 mutation. The trial will evaluate the effects of using higher dose of the drug combination over a longer period than in earlier combination trial, which showed that VX-770 did further potentiate the channel activity of ΔF508-CFTR rescued by VX-809 [106].

Emerging and promising therapies/methodologies

Co-administration of CFTR modulators

Given the facts that ΔF508-CFTR is a processing defect, which is retained in the ER and rapidly degraded, and that the temperature-rescued protein is unstable at the cell surface with impaired channel activity, the ideal therapy for CF associated with ΔF508 mutation would be to promote its folding efficiency to increase the amount of protein at the cell surface and also fully restore its Cl− permeability [24]. Co-administration of a CFTR corrector and a potentiator is one of the approaches expected to achieve this goal. Currently, plans have been disclosed for evaluating VX-809 in combination with VX-770 in a Phase IIa clinical trial in CF patients who have the ΔF508 mutation [106].

Dual-activity CFTR modulators

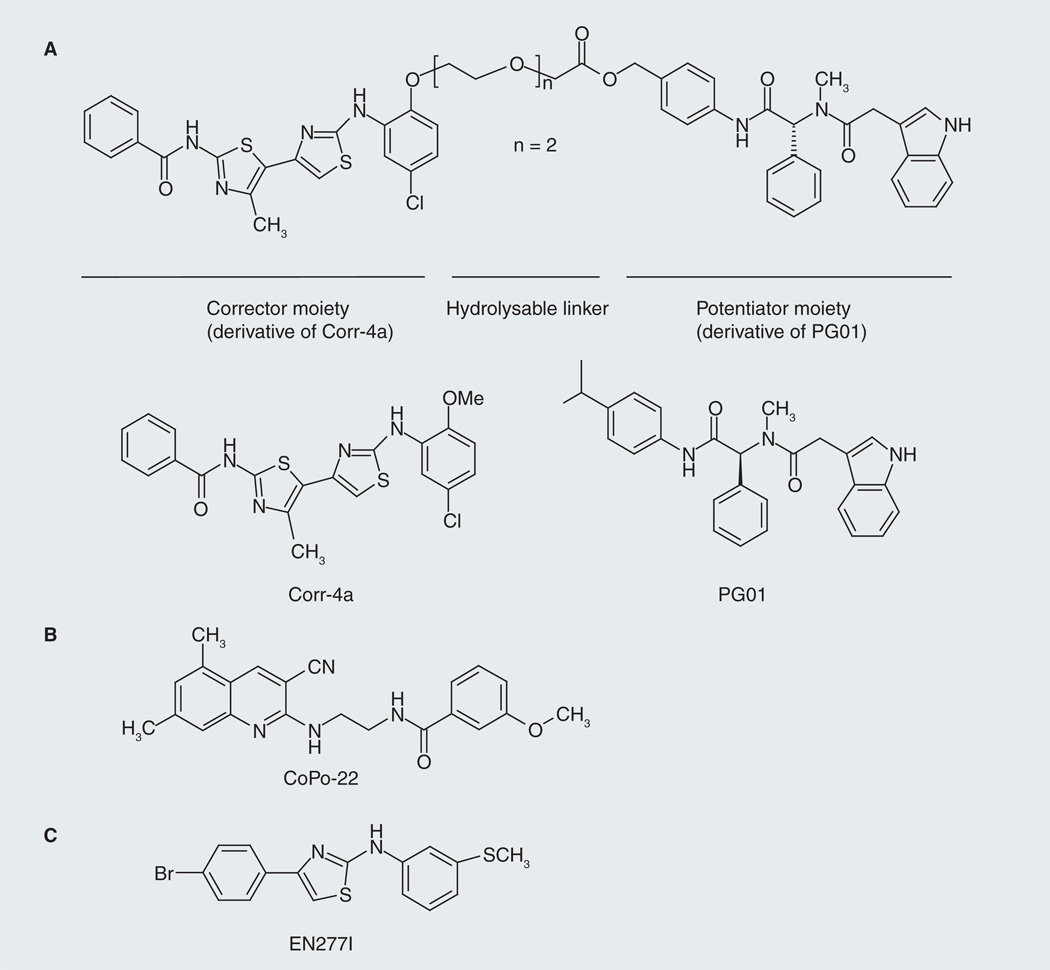

In addition to the approach of co-administration of CFTR modulators to treat CF caused by ΔF508-CFTR, development of drugs that have ‘potentiation’ capacity and ‘correction’ capacity in one molecule is another promising approach. Compared with multicomponent drugs, the single-drug therapy has some apparent advantages, that is, the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship studies for single drugs are easier to conduct in terms of the amount of work and the financial resources needed for the preclinical and clinical evaluation [25]. Generally, two approaches were adopted to develop dual-activity modulators for ΔF508-CFTR. One approach is to identify compounds that have intrinsic-independent correcting and potentiating capability, the other is to synthesize ‘hybrid’ molecules that constitute a ‘corrector’ moiety (derived from a known corrector) and a ‘potentiator’ moiety (derived from a known potentiator).

Based on the structure–activity relationship (SAR) data for phenylglycine-type CFTR potentiators and bithiazole-type correctors, Mills and colleagues designed and synthesized a hybrid molecule (a prodrug) incorporating a potentiator moiety (derived from CFTR potentiator PG01) and a corrector moiety (derived from CFTR corrector Corr-4a) linked by an enzymatic hydrolysable ethylene glycol spacer through an ester bond (Figure 4A) [26]. The authors demonstrated that, after cleavage by intestinal enzymes under physiological conditions, the hybrid molecule yielded active potentiator and corrector fragments, which had low micromolar potency for restoring ΔF508-CFTR channel gating and cellular processing in FRT cells stably expressing human ΔF508-CFTR [26]. The study is an example for the design of potentiator-corrector hybrids for CF therapy caused by ΔF508 mutation.

Figure 4. Approaches used to discover dual-acting cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators.

(A) Synthesis of a ‘hybrid’ molecule, which constitutes a ‘corrector’ moiety (derived from a potent CFTR corrector) and a ‘potentiator’ moiety (derived from a potent CFTR potentiator). Shown here is a compound synthesized by Mills et al., which consists of a corrector moiety (derived from corrector Corr-4a) and a potentiator moiety (derived from potentiator PG01) linked by an enzymatic hydrolysable ethylene glycol spacer through an ester bond [26]. (B) Identification of compounds that have intrinsic independent correcting and potentiating capacity. Shown here is a compound (CoPo-22), which was identified by Verkman et al. and demonstrated dual correcting and potentiating capability for ΔF508-CFTR [24]. (C) EN277I is another compound identified by Verkman et al., which exhibited dual correcting and potentiating capability (upon chronic treatment) for ΔF508-CFTR [28].

CFTR: Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator.

More recently, Verkman and colleagues used a cell-based HTS method to identify compounds that have both the correcting and potentiating capacities [24]. They screened a total of 110,000 diverse drug-like small molecules and found that a cyanoquinoline class of compounds exhibit corrector and potentiator activities. For chemical optimization, they tested 180 commercially available cyanoquinoline analogs and found six compounds exhibiting dual correcting and potentiating activities. CoPo-22 (Figure 4B) was found to be the most potent corrector with low micromolar EC50 value for correcting (2.2 µM) and potentiating (~10 µM) ΔF508-CFTR. The maximal corrector and potentiator activities of CoPo-22 were comparable to those of Corr-4a (Figure 4A) and genistein, respectively [24]. In addition to ΔF508-CFTR, CoPo-22 was also found to potentiate FSK-induced WT- and G551D-CFTR Cl− conductance within minutes. An initial SAR analysis was performed on the core cyanoquinoline scaffold and suggested that the dual-acting activity is not a general feature of cyanoquinolines but depends on the specific structure of the leads [24].

Some aminoarylthiazole compounds (AATs) have previously been identified as correctors for ΔF508-CFTR [27]. Recently, Pedemonte et al. reported that some AATs also exhibited potentiating activity for ΔF508-CFTR and Class III mutants such as G1349D and G551D upon chronic treatment (24 h) [28]. Among the ATTs tested, EN277I (Figure 4C) was identified as the most effective compound. In fluorescence-based halide transport assays in FRT cells expressing mutant CFTR (HS-YFP assays), the Kd values of EN277I for correcting or potentiating ΔF508-CFTR were calculated as 19.2 ± 0.8 and 20.1 ± 2.2 µM, respectively. Similarly, the Kd values of EN277I for potentiating G1349D or G551D were 15.8 ± 1.1 µM and 25.1 ± 1.9 µM, respectively [28]. Similar to cyanoquinoline compounds [24], it was found that the dual activity is not a general feature of AAT scaffold. The mechanism underlying the dual capability of AATs was speculated as their binding to mutant CFTR, which causes a mild potentiating effect on channel function after acute treatment. Prolonged (chronic) interaction of the molecule at the binding site(s) causes a further improvement in potentiating the channel activity as well as in rescuing the trafficking defects [28].

Mechanism-of-action studies

The molecular mechanisms underlying the action of CFTR potentiators are suggested to be their direct binding to the mutant CFTRs at the cell surface and normalizing the defective channel gating [24,29]. The molecular mechanisms underlying the ‘correcting action’ of CFTR correctors remain largely unknown. The accumulating evidence suggests that:

-

▪

The correctors bind directly to ΔF508-CFTR and act as pharmacological chaperones to help fold the mutant protein [30];

-

▪

The correctors stabilize the rescued mutant protein at the cell surface [30,31];

-

▪

The correctors might influence the activity of the proteostasis network [32].

Mechanistic studies are urgently needed because the results from these investigations would not only help us better understand the structural (molecular) basis for the misfolding and mistrafficking of ΔF508-CFTR, but also greatly advance the progress for structure-based design and mechanism-based screening of CF drugs.

Structure-based discovery of CFTR modulators

In addition to the HTS method for identification of CFTR modulators, the structure-based virtual screening method has also been attempted. By using a homology model of CFTR, Kalid et al. identified three putative binding sites at the interfaces between the cytoplasmic domains of CFTR and performed the in silico screening of virtual libraries. The 496 candidate compounds were tested in functional assays, which yielded 15 correctors with diverse structure. Potentiators and dual-acting compounds were also identified in their studies [33]. Once the high-resolution structures of WT and ΔF508-CFTR are determined and the binding site(s) for CFTR modulators are defined, the structure-based design and in silico screening methods will play more influential roles in CF drug discovery.

Summary

In the last two decades, significant progress has been made in the field of CFTR drug discovery. As a result, three compounds (VX-770, VX-809 and Atularen) have entered clinical trials and VX-770 has been approved by the US FDA to treat CF patients aged 6 or older with G551D mutation. These results indicate that CFTR is a validated drug target for CF drug discovery. However, with no approved CFTR modulators for treating CF due to ΔF508 mutation, CFTR drug discovery is still at an early stage. Moreover, studies are still required to study the effects of long-term use of CFTR modulators in CF patients with diverse genetic background, age and disease stage [14].

Targeting CFTR for therapy of enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas

Since CFTR plays the central role in the pathogenic process of enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas as described above, CFTR inhibitors (blockers) would be an appropriate therapy for these forms of diseases.

Development of CFTR inhibitors for therapy of enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas

CFTR inhibitors identified from natural products

Several natural product extracts, such as SP-303 (Crofelemer [34]) and Cocoa-related flavonoids [35], have been shown to inhibit CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion and inhibit enterotoxin-induced intestinal fluid accumulation.

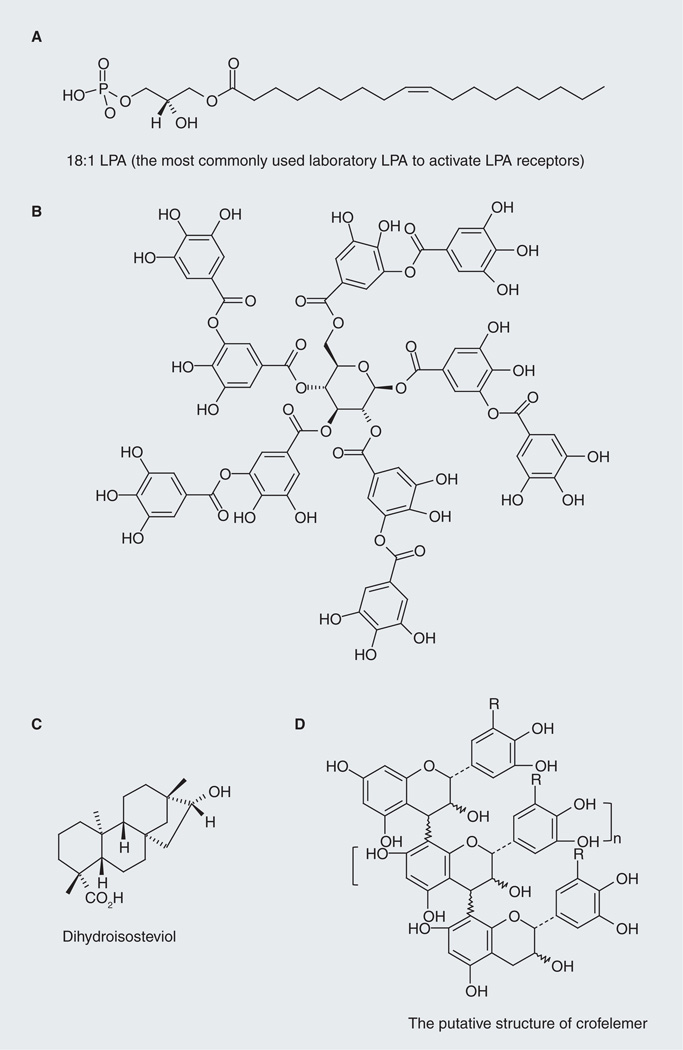

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA; Figure 5A) is a growth factor-like phospholipid present in biological fluids and foods. LPA mediates diverse cellular responses, such as migration, survival, inflammation and electrolyte transport in epithelial cells [36]. We found that LPA efficiently inhibits CFTR-dependent transepithelial Cl− transport in gut epithelial cells and inhibits cholera toxin (CTX)-induced secretory diarrhea in mice [36]. Coincidently, LPA has also been found to acutely stimulate Na+ and fluid absorption in human intestinal epithelial cells and in mouse intestine by activating NHE3 through an LPA5-mediated signaling cascade [37]. Therefore, LPA or LPA-rich food (e.g., hen egg yolk and white, and LPA-enriched soy lipid extract) would be a cost-effective method to treat enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas [36,38].

Figure 5. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator inhibitors identified from natural products.

(A) 18:1 lysophosphatidic acid. (B) Representative structure of tannic acid. (C) Dihydroisosteviol. (D) The putative structure of Crofelemer. Crofelemer has entered clinical trials and demonstrated efficacy in treating several types of enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas, including cholera.

LPA: Lysophosphatidic acid.

Tannins (tannic acid; Figure 5B) are polyphenols commonly found in plants including grape seed, oak and tea [39]. The use of tannins for treating gastrointestinal diseases can be dated back to the early 20th century. Tannins, both condensed and hydrolyzable types, have been shown to inhibit CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion in Caco-2, FRT, T84 and HT29-CL19A cells [34,40,41], and inhibit CTX-induced intestinal fluid secretion in a mouse acute diarrheal model [40,41]. More recently, we reported that Cesinex®, which is a medical food based on food-grade tannic acid and dried egg albumen, demonstrates a good safety profile and efficacy in treatment of diarrhea. Although the broad-spectrum antidiarrheal effect of Cesinex can be attributed to a combination of factors, including its ability to improve intestinal epithelial barrier function and its high antioxidant capacity, inhibiting CFTR-dependent intestinal fluid secretion plays an important role. The presence of egg albumen (rich in LPA) also increases its antidiarrheal efficacy [41]. Given the fact that the tannins used in these studies are natural extracts, which consist of a mixture of several structurally similar compounds, to develop more efficacious therapy we need to separate these structurally similar components, study their SAR and optimize the anti-diarrheal activity of the hit by medicinal chemistry input.

Stevioside, the major component of extract from Stevia rebaudiana, its metabolites steviol and analogs have been reported to affect ion transport in several types of tissues. Pariwat et al. demonstrated that dihydroisosteviol (Figure 5C) inhibited FSK-induced Cl− transport in T84 cells in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 value of 9.6 µM. The inhibitory mechanism was found through targeting apical CFTR channel. The inhibitory effect was temporal and reversible implying dihydroisosteviol affects Cl− secretion from outside the cell. Dihydroisosteviol was found nontoxic to T84 cells and has no effect on CaCCs. In in vivo experiments using a mouse closed-loop model of diarrhea, the authors demonstrated that intraluminal injection of 50-µM dihydroisosteviol reduced CTX-induced intestinal-fluid secretion by 88.2% without altering fluid absorption, indicating the antidiarrheal efficacy of this compound [42].

Crofelemer (also known as SP-303) is a purified proanthocyanidin oligomer (average molecular mass: ~2300 Da) extracted from the bark latex of Croton lechleri (it putative structure is shown in Figure 5D). Crofelemer has been shown to inhibit CFTR Cl− channel function (IC50: ~7 µM; maximum inhibition: ~90%) and the intestinal calcium-activated Cl− channel TMEM16A (IC50: ~6.5 µM; maximum inhibition: >90%) [43]. The dual inhibitory action of crofelemer on two distinct intestinal Cl− channels may account for its intestinal anti-secretory effect. Clinically, crofelemer has demonstrated efficacy in treating several types of secretory diarrhea including infectious diarrhea due to cholera, AIDS-associated diarrhea and travelers’ diarrhea (for an excellent review, see [44]). In a preliminary study from Bangladesh, to test the safety and efficacy of crofelemer on reducing watery stool output due to cholera within 24 h vs placebo, single-dose crofelemer (125 or 250 mg) or placebo was given to the subjects (100 adults, aged 18–55 years old) after a 4-h period of rehydration therapy. The results showed that the group treated with crofelemer have significant reduction of normalized watery stool output compared with placebo-treated group (125-mg dosage: 25–30% reduction, p = 0.028; 250-mg dosage: 25–30% reduction, p = 0.07). In another study from India, which tested the effect of crofelemer in treating patients with acute dehydrating watery diarrhea due to E.coli or V. cholera, patients were given oral dose of crofelemer 250 mg every 6 h for 2 days (n = 51) or placebo (n = 47) in combination with ORT. The results showed that crofelemer-treated patients have better overall clinical success than placebo-treated group [45]. Oral administration of crofelemer in clinical trials seemed to be well tolerated. However, larger scale clinical studies are still needed to determine the clinical efficacy and long-term safety of this agent [44].

Small-molecule CFTR inhibitors identified by HTS methods

Before the systematic screening for specific and potent CFTR inhibitors, several compounds, such as glibenclamide, diphenylamine-2-carboxylate, 5-nitro-2(3-phenylpropyl-amino) benzoate and flufenamic acid, have been found to inhibit CFTR channel function with weak potency and poor specificity [17].

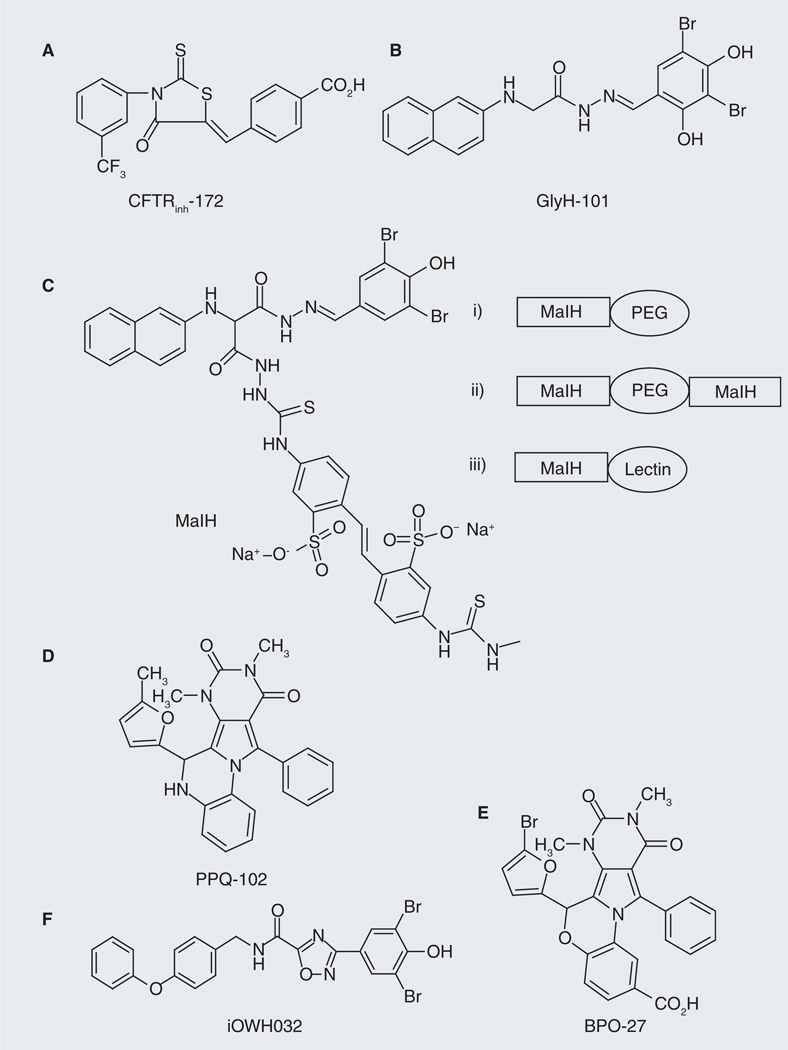

Verkman and colleagues utilized cell-based fluorescence assays and subsequent chemical optimization to identify novel, more specific and potent CFTR inhibitors. Initially they found that two classes of compounds, thiazolidiones and glycine hydrazides, inhibited CFTR channel function. Thiazolidione-type CFTR inhibitors such as CFTRinh-172 (Figure 6A) were found to act from the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane to block CFTR Cl− conductance. CFTRinh-172 inhibited CFTR channel function with improved potency (~500-times better than glibenclamide control; IC50: ~0.3–3 µM depending on cell type and membrane potential) and specificity (it did not affect several other calcium- or volume-activated Cl− channels, or other ATP-binding cassette transporters) and was found to have low toxicity and metabolic stability [46,47]. The glycine hydrazides-type compounds, such as GlyH-101 (Figure 6B), were found to inhibit CFTR channel function with an IC50 value of ~5 µM and act through an external pore occlusion mechanism [48]. The inhibitory effect of CFTRinh-172 and GlyH-101 on CTX-induced intestinal fluid secretion was demonstrated in a mouse closed-loop model, indicating their antidiarrheal efficacy [48,49]. It was also found that CFTRinh-172 inhibited fluid secretion after E. coli STa toxin infection in human intestine [49]. The analogs of GlyH-101 were prepared for SAR analysis [48]. CFTRinh-172 has been widely used as a research tool to study CFTR functions in cell culture, ex vivo tissues and in vivo.

Figure 6. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator inhibitors identified through high-throughput screening.

(A) CFTRinh-172 is a thiazodione-type compound, which was demonstrated to inhibit cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-mediated chloride and fluid transport in cell and in vivo. (B) GlyH-101 is a glycine hydrazides type compound, which was also shown to inhibit CFTR-mediated chloride and fluid transport in cell and in vivo. (C) Non-absorbable CFTR inhibitors based on glycine hydrozide scaffold. MaIH was conjugated to PEG of different sizes (i–ii) or lectins (iii), yielding those luminal active, nonabsorbable CFTR inhibitors. (D) The structure of PPQ-102, which represents a new class of membrane-potential insensitive PPQ CFTR inhibitors. (E) The structure of BPO-27, which represents a new class of water-soluble, metabolic-stable and membrane-potential insensitive benzo-PPQ CFTR inhibitors. (F) The structure of iOWH032, which was developed by One World Health and is currently in Phase I clinical trials.

PEG: Polyethylene glycol; PPQ: Pyrimido-pyrrolo-quinoxalinedione.

The Verkman laboratory also reported the discovery of nonabsorbable CFTR inhibitors based on glycine hydrazide scaffold [50–52]. The rational for developing such nonabsorbable CFTR inhibitors for antidiarrheal therapy is that high concentrations of compound can be achieved in the gut lumen, where CFTR is expressed so that the concerns related to toxicity and off-target effects resulting from cellular uptake and systemic absorption can be minimized. One of the strategies the authors used to develop such luminal active and nonabsorbable CFTR inhibitors was to conjugate a GlyH-101 analog, malonic acid hydrazide (MaIH; Figure 6C), to water soluble polymer polyethylene glycol (PEG) [50,52] or to lectins [51]. It was found that monovalent MaIH-PEGs (Figure 6C: i) inhibited CFTR-mediated Isc rapidly (IC50: 10–15 µM) and reversibly after washout, and that when added in the lumen of closed mid-jejunal intestinal loops in mice, MaIH-PEGs inhibited CTX-induced intestinal fluid secretion in a dose-dependent manner with essentially complete inhibition at the higher amounts [50,52]. MaIH-PEGs were found to be nontoxic in cell culture and in mice. Compared with these monovalent MaIH-PEG conjugates, the divalent MaIH-PEG-MaIH compounds (Figure 6C: ii) showed improved CFTR inhibition potency (IC50 value: <1 µM) and improved antidiarrheal efficacy in both intestinal closed-loop model (IC50 value: ~10 pmol/loop) and sucking mouse survival model (reduced mortality) [50]. The MaIH–lectin conjugates (Figure 6C: iii) were also found to have improved CFTR inhibitory potency (IC50 value down to 50 nM) and improved resistance to washout. MaIH–conconavalin A and MaIH–wheat inhibited CTX-induced intestinal fluid secretion in mice closed mid-jejunal intestinal loops (IC50 value: 50–100 pmol/loop) and greatly reduced mortality in sucking mouse survival models of cholera [51]. All these MaIH conjugates were found to act by a pore-occluding mechanism from the extracellular side of CFTR [50–52].

Recently, Verkman et al. also reported the discovery, SAR analysis and characterization of a new class of pyrimido-pyrrolo-quinoxalinedione (PPQ) CFTR inhibitors that are uncharged at physiological pH and, thus, membrane-potential insensitive [53]. The most potent compound, PPQ-102 (Figure 6D), completely inhibited CFTR Cl− current with an IC50 value of approximately 90 nM. Patch-clamp analysis revealed that PPQ-102 stabilizes the CFTR channel closed state. It was suggested that PPQ-102 acts at a site on the cytoplasmic-facing surface of CFTR distinct from its pore. In an embryonic kidney organ culture model of PKD, PPQ-102 prevented cyst expansion and reduced the size of preformed cysts [53]. However, PPQ-102 has poor metabolic stability and low water solubility [54]. The in vivo antisecretory effect of PPQ-102 for enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas was not tested.

To further improve CFTR inhibitory potency, compound metabolic stability and water solubility, Verkman et al. synthesized 16 PPQ analogous and 11 BPO (benzopyrimido–pyrrolo–oxazinedione) analogues and tested their inhibitory potency and drug-like properties [54]. The best compound found was BPO-27 (Figure 6E), which inhibited CFTR-mediated Isc with IC50 of approximately 8 nM and, compared with PPQ-102, exhibited >tenfold greater metabolic stability and much greater water solubility. In an embryonic kidney culture model of PKD, BPO-27 prevented cyst growth with an IC50 of approximately 100 nM (>fivefold potency over PPQ-102) [54]. The in vivo antisecretory effect of BPO-27 for enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas was not tested.

One World Heath (OWH) also developed CFTR inhibitors which share the halophenol moiety as that in GlyH compounds. The inhibitory activities of OWH compounds on CFTR Cl− channel function were tested in cell lines and also in animal models of secretory diarrhea. The lead compound iOWH032 (Figure 6F) inhibited fluid secretion by nearly 70%, as measured on a semi-quantitative fecal output scale. iOWH032 is currently in Phase I clinical trials [55]. To the best of our knowledge, iOWH032 is the first synthetic CFTR inhibitor to enter clinical trials.

Summary

ORT has been a great success in reducing the morbidity and mortality of enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas, which has in many ways slowed down the development of other novel drugs. The adoption of ORT as the standard of care has slowed down in recent years [54]. One possible reason is that ORT does not reduce or prevent the pathogenic fluid loss process of the diseases, thus does not provide quick clinical relief of diarrhea symptoms. More specific and potent anti-secretory agents such as LPA, type 2 lysophosphatidic acid receptor (LPA2) agonists and small-molecule CFTR inhibitors have the advantage of curing or preventing ‘the root cause’ of secretory diarrheas; therefore, they can be useful additions to the ORT to enhance its efficacy and adoption for treatment of secretory diarrheas.

Perspective: can CFTR-containing macromolecular complexes serve as targets for therapy of CF & enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas?

Protein–protein interactions regulate virtually all cellular processes by promoting the proper cellular localization of regulatory partners and/or by facilitating the signaling through reaction pathways to warrant exquisite spatiotemporal control. It is now well accepted that formation of multiprotein complexes at discrete subcellular microdomains increases the specificity and efficiency of signaling in cells [56–58].

CFTR-containing macromolecular complexes

The apical surface localized CFTR Cl− channel can be activated through phosphorylation of the R domain by various protein kinases and by ATP binding to, and hydrolysis by, the NBDs (Figure 1). The intracellular processing, trafficking, apical membrane localization and channel function of CFTR are regulated by protein–protein interactions involving a wide variety of proteins (e.g., channels/transporters, receptors and scaffolding proteins) in a complex network termed as the CFTR interactome [59,60]. Examples of the CFTR-containing macromolecular complexes that have been characterized at the molecular and cellular levels include, but are not limited to, the macromolecular signaling complex of β2-adrenergic receptor, NHERF1 and CFTR at the apical surfaces of airway epithelial cells, which couples β2-adrenergic signaling to CFTR-channel function [61], the macromolecular signaling complex of LPA2, NHERF2 and CFTR at the apical surfaces of airway and intestinal epithelial cells, which couples LPA signaling to CFTR channel function [36], the macromolecular complex of MRP4, PDZ domain-containing protein in kidney 1, and CFTR at the apical surfaces of gut epithelial cells, which spatiotemporally couples the cAMP transporter activity of MRP4 to CFTR channel function [56].

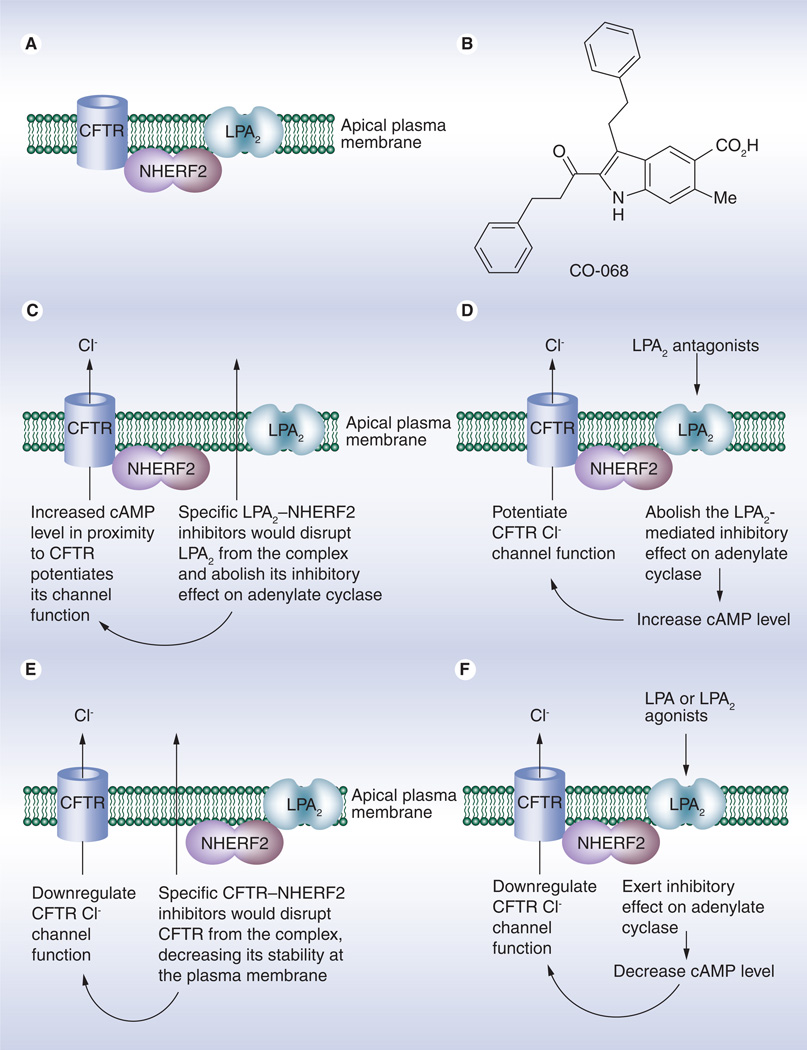

CFTR–NHERF2–LPA2-containing macromolecular complex in the airway & a possible target for therapeutic interventions of CF

Recently, we found that CFTR, LPA2 and NHERF2 (along with other signaling molecules) form a macromolecular complex at the plasma membrane of airway epithelium, which functionally couples LPA2-mediated signaling to CFTR-mediated Cl− transport (Figure 7A) [36]. Our observations are supported by in vivo studies [62]. Since the potential of using biological agents (such as peptides) or small-molecule mimics to disrupt a particular PDZ domain-mediated interaction and modify a specific biological process have been reported [63,64], we sought to explore the possibility of targeting this CFTR-containing macromolecular complex, specifically by perturbing PDZ domain-mediated protein–protein interactions within this complex, to upregulate CFTR channel function for therapy of CF. To this end, we first developed an AlphaScreen-based assay to screen for compounds that can specifically inhibit the LPA2–NHERF2 interaction. A library of 80 compounds that were previously designed to inhibit PDZ domain-mediated protein–protein interactions [65–68] was subjected to the screening. We found one compound (named as CO-068; Figure 7B) can preferentially inhibit the biochemical LPA2 peptide (derived from the C terminal tail of LPA2)–NHERF2 interaction. We next demonstrated that CO-068 specifically disrupts the LPA2–NHERF2 interaction in cells and, functionally, augments CFTR Cl− channel activity in Calu-3 cells. We then showed that this compound augments both basal and FSK-induced CFTR-dependent submucosal gland fluid secretion in a pig model. Mechanistically, we found that compound CO-068 potentiates CFTR Cl− channel function by means of elevating compartmentalized cAMP levels in cells (Figure 7C) [69]. More recently, we found that this compound can further potentiate the channel function of temperature-rescued ΔF508-CFTR in CFBEo-cells [Weiqiang Z, Unpublished Data]. Our findings suggest that these types of molecules have the potential to treat CF associated with regulation or permeation mutants such as G551D or R117H, and that, when used in combination with a CFTR corrector, they have the potential for treating CF due to the ΔF508 mutation. The strategy we used is novel and highlights the potential to fine-tune the CFTR channel function by modulating indirect protein–protein interactions rather than by modifying CFTR-involving protein–protein interactions.

Figure 7. Targeting cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-containing macromolecular complex for therapy of cystic fibrosis and enterotoxin-induce secretory diarrheas.

(A) A macromolecular complex of CFTR, NHERF2 and LPA2 exists at the apical surfaces of airway and gut epithelial cells. The macromolecular complex forms the molecular foundation for the coupling of LPA2-mediated signaling and CFTR chloride channel function. (B) A small-molecule inhibitor (CO-068) for LPA2–NHERF2 interaction was demonstrated to specifically disrupt the interaction in cells and potentiate CFTR chloride channel function in cells and in tissues, thus having the potential to treat CF associated with a gating defect such as G551D–CFTR. (C) Mechanism underlying the potentiating effect of specific LPA2-NHERF2 inhibitors on CFTR chloride channel function. (D) Mechanism underlying the potentiating effect of specific LPA2 antagonists on CFTR chloride channel function. (E) Mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of specific CFTR–NHERF2 inhibitors on CFTR chloride channel function. (F) Mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of specific LPA2 agonists (or LPA) on CFTR chloride channel function.

CFTR: Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; LPA2: Type 2 lysophosphatidic acid receptor.

The IC50 value of compound CO-068 for LPA2–NHERF2 interaction is relatively high, which limits its application to in vivo studies and highlights the need for chemical optimization to discover more potent and specific lead compounds. Structure biological studies on LPA2–NHERF2 interaction and the binding site for compound CO-068 will help design and identify lead compounds.

Another approach for targeting this macromolecular complex for therapy of CF is to use specific and potent LPA2 antagonists to attenuate the inhibitory effect of LPA2 on adenylate cyclase and ultimately potentiates CFTR channel function (Figure 7D). This type of LPA2 antagonists also have the potential to treat CF associated with the regulation (Class III) or permeation (Class IV) mutations and CF due to ΔF508 mutation when used in combination with a CFTR corrector.

CFTR–NHERF2–LPA2-containing macromolecular complexes in the gut & a possible target for therapeutic interventions of enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas

CFTR–NHERF2–LPA2-containing macromolecular complex also exists at the plasma membrane of gut epithelial cells. We demonstrated that LPA inhibits CFTR-mediated Cl− transport through LPA2-mediated Gi pathway in a compartmentalized manner in cells and that LPA inhibits CFTR-dependent CTX-induced intestinal fluid secretion in an acute diarrhea model in mice [36]. Our observations are supported by other in vivo studies, which showed that FSK-stimulated CFTR-dependent murine duodenal HCO3− secretion was significantly increased in Nherf2−/− mice and that NHERF2 is absolutely required for LPA2-mediated inhibition of HCO3− secretion [62]. These findings imply that targeting NHERF2-meidated protein–protein interactions might provide new approaches for therapeutic interventions of CFTR-associated diseases [36,62].

As described above, LPA has also been found to acutely stimulate Na+ and fluid absorption in human intestinal epithelial cells and in mouse intestine by activating NHE3 through an LPA5-mediated signaling cascade [37]. Taken together, LPA or LPA-rich food (e.g., hen egg yolk and white, and LPA-enriched soy lipid extract) can be considered as an alternative method to treat enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas [38].

Similarly, it can be envisioned that specific and potent LPA2 agonists would inhibit the CFTR channel function and have the potential to treat enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas (Figure 7F).

It can also be envisioned that inhibitors for CFTR–NHERF2 interaction would spatially isolate CFTR from the macromolecular complex, thus decreasing its stability at the plasma membrane and downregulating its Cl− channel function. Therefore, the specific and potent CFTR-NHERF2 inhibitors have the potential to treat enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas (Figure 7E).

Summary

Our studies suggest that CFTR-containing macromolecular complexes could potentially be new therapeutic targets for treating CFTR-associated diseases. Notably, the studies suggest that, by targeting different PDZ domain-mediated protein–protein interactions within the LPA2–NHERF2–CFTR-containing macromolecular complex, we can modulate CFTR channel function on a use-dependent mode for treating different diseases; for instance, targeting the LPA2–NHERF2 interaction to potentiate CFTR Cl− channel function for drug development to treat CF and targeting the CFTR–NHERF2 interaction to downregulate CFTR Cl− channel function for drug development to treat enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas. Currently, development of more potent and specific inhibitors for LPA2–NHERF2 interaction and for CFTR–NHERF2 interaction, and development of specific and potent LPA2 agonists or antagonists, is under way.

Future perspective

During the past two decades, tremendous progress has been made in identification and elucidation of molecules that regulate CFTR activity and in identification of ‘drugable’ targets for treating CFTR-associated diseases. As a result, several small-molecule compounds are entering clinical trials. However, with no approved CFTR modulators for treating CF due to the ΔF508 mutation, CF drug discovery is still at an early stage. From the authors’ point of view, the progress of CFTR modulators development, especially the development of correctors for ΔF508 CFTR, will critically depend on our knowledge on the following topics:

-

▪

The structural differences between WT and mutant CFTR at different stages of their intracellular processing and trafficking. The structural differences between WT and mutant CFTR at their cell surface dwelling, phosphorylation states and at their catalytic and gating cycles. X-ray crystallography, NMR and other computational studies will help us better understand the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying these differences and help advance the progress for structure-based drug design and in silico screening;

-

▪

The differences between CFTR interactome for WT and mutant CFTR. How do mutations in CFTR affect the formation and localization of CFTR-containing macromolecular complexes? And whether alterations in the formation and localization of these macromolecular complexes account for the numerous phenotypic changes observed in CF patients.

Executive summary.

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) & its role in cystic fibrosis (CF) & enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas

-

▪

The CFTR is a cAMP-regulated chloride (Cl−) channel localized primarily at the apical surfaces of epithelial cells lining airway, gut and exocrine glands, where it is responsible for transepithelial salt and water transport.

-

▪

Several human diseases result from an altered function of the CFTR Cl− channel. CF and enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas are the two major disorders. CFTR hypofunctioning due to mutations on the CFTR gene causes CF. CFTR hyperfunctioning resulting from infection by pathogenic microorganisms leads to secretory diarrheas. Therefore, CFTR can be targeted for therapy of these diseases.

Development of small-molecule CFTR modulators for therapy of CF or enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas

-

▪

Small-molecule CFTR modulators are agents that can alter CFTR Cl− channel function through different mechanisms. CFTR activators, potentiators and correctors can upregulate CFTR channel function by means of increasing the amount of functional protein at the cell surface (correctors), by increasing channel gating activity (potentiators) or by increasing the phosphorylation status of CFTR (activators). These modulators are being developed for CF therapy. CFTR inhibitors (blockers) can downregulate CFTR channel function by either occluding the pore of the Cl− channel or decreasing the intracellular second messenger (cAMP or/and cGMP) levels, thus altering the phosphorylation states of CFTR. CFTR inhibitors are being developed for therapy of enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas.

-

▪

Three orally administered investigational CFTR modulators are currently being tested in clinical trials. Atularen (PTC124®) is being evaluated in a Phase III trial in CF patients aged 6 and above who have a nonsense mutation. VX-770 is a CFTR potentiator, which demonstrated efficacy and safety profile in treating CF patients with G551D mutation. VX-770 has been approved to treat CF patients aged 6 or older with G551D mutation by the US FDA. VX-809 is a CFTR corrector developed to increase the folding efficiency of ΔF508-CFTR and help deliver it to cell surfaces.

-

▪

Emerging ideas/methodologies for CF therapy include co-administration of CFTR modulators, development of dual-activity CFTR modulators, structure-based drug design and in silico screening. The mechanistic studies underlying the actions of CFTR modulators are urgently needed because such investigation will help better understand the molecular basis for the misfolding and mistrafficking of CFTR mutant and advance the progress for structure-based CF drug design and in silico screening.

-

▪

Small-molecule CFTR inhibitors have been identified through high-throughput screening followed by hit-to-lead optimization. iOWH032 is the first synthetic CFTR inhibitors to enter clinical trials. Other types of CFTR inhibitors have also been identified from natural products including Crofelemer, tannins, lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and Cocoa-related flavonoids.

Targeting CFTR-containing macromolecular complexes for therapy of CF or enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas

-

▪

CFTR-containing macromolecular complexes can be targeted for treating CF or enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas. A macromolecular complex of CFTR, NHERF2 and LPA2 exists at the plasma membrane of airway epithelium. The potent and specific LPA2–NHERF2 inhibitors, as well as LPA2 antagonists, can potentiate CFTR channel function and have potentials for CF therapy.

-

▪

The macromolecular complex of CFTR, NHERF2 and LPA2 also exists at the plasma membrane of intestinal epithelium. The potent and specific CFTR-NHERF2 inhibitors, LPA2 agonists and LPA can downregulate CFTR channel function, thus having potential for therapy of enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Grant DK-093045 and DK-080834 (to AP Naren) from the US NIH.

Key Terms

- CFTR chloride channel

Amount of chloride transported by the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulato is determined by the number of channels at the cell surface, the open probability (Po) of the channels and the single channel conductance. Mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulato alter one or more of these parameters and decrease the channel activity.

- ΔF508-CFTR

ΔF508-CFTR is the most common cystic fibrosis (CF) mutation; more than 90% of CF patients carry ΔF508 on at least one allele. ΔF508-CFTR is also associated with a severe form of CF disease. ΔF508-CFTR results from the deletion of three nucleotides in the gene and, thus, the deletion of a phenylalanine (F) residue at position 508 on the protein. The ΔF508-CFTR protein is unstable and insufficiently folded, which is, therefore, trapped in the endoplasmic reticulum and targeted for degradation. Although the mutant protein can be partially rescued by exposure to low temperature, it is unstable at the plasma membrane and exhibits impaired channel activity.

- Single-drug therapy

The ideal therapy for cystic fibrosis associated with ΔF508-cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator would be a single-drug therapy that not only rescues the defective ΔF508-cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator folding and intracellular processing, but restores its impaired gating property at the cell surface. Single-drug therapy has some intrinsic advantages over multicomponent-drug therapy; that is, there is no need to conduct extensive clinical studies to clarify the drug–drug interactions required in multicomponent-drug development.

- CFTR-containing macromolecular complexes

A growing number of studies suggest that cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is coupled spatially and temporally to a wide variety of interacting partners including membrane receptors (e.g., β2 adrenergic receptor), ion channels/transporters (e.g., multidrug-resistance protein 4), scaffolding proteins (e.g., sodium/hydrogen exchanger regulator factors) and other signaling molecules. The dynamic protein–protein interactions within these macromolecular complexes play important roles in the regulation of CFTR channel function and could be targeted for drug development to treat diseases associated with altered CFTR channel function.

- CO-068

A 411-Da cell-permeable inhibitor for type 2 lysophosphatidic acid receptor (LPA2)–NHERF2 interaction (IC50 = 63 µM). At 50 µM concentration, it specifically disrupts LPA2–NHERF2 interaction in cells without affecting cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator–NHERF2 interaction, or NHERF2–PLC-β3 interaction.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245(4922):1066–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson MP, Gregory RJ, Thompson S, et al. Demonstration that CFTR is a chloride channel by alteration of its anion selectivity. Science. 1991;253(5016):202–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1712984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bear CE, Li CH, Kartner N, et al. Purification and functional reconstitution of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cell. 1992;68(4):809–818. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis HA, Buchanan SG, Burley SK, et al. Structure of nucleotide-binding domain 1 of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. EMBO J. 2004;23(2):282–293. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis HA, Wang C, Zhao X, et al. Structure and dynamics of NBD1 from CFTR characterized using crystallography and hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;396(2):406–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendoza JL, Thomas PJ. Building an understanding of cystic fibrosis on the foundation of ABC transporter structures. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2007;39(5–6):499–505. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serohijos AW, Hegedus T, Aleksandrov AA, et al. Phenylalanine-508 mediates a cytoplasmic-membrane domain contact in the CFTR 3D structure crucial to assembly and channel function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105(9):3256–3261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800254105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penmatsa H, Frederick CA, Nekkalapu S, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of S1118F-CFTR. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2009;44(10):1003–1009. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welsh MJ, Tsui L-C, Boat TF, Beau det AL. Cystic fibrosis. In: Scriver C, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Diseases: Membrane Transport Systems. NY, USA: McGraw-Hill; 1995. pp. 3799–3876. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cormet-Boyaka E, Naren AP, Kirk KL. CFTR interacting proteins. In: Kirk KL, Dawson DC, editors. The Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator. NY, USA: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 94–118. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Marshall J, et al. Defective intracellular transport and processing of CFTR is the molecular basis of most cystic fibrosis. Cell. 1990;63(4):827–834. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welsh MJ, Smith AE. Molecular mechanisms of CFTR chloride channel dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. Cell. 1993;73(7):1251–1254. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90353-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies JC, Alton EW, Bush A. Cystic fibrosis. BMJ. 2007;335(7632):1255–1259. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39391.713229.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hadida S, Van Goor F, Grootenhuis PDJ. Macor JE, editor. CFTR modulators for the treatment of cystic fibrosis. Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry (Volume 45) 2010:157–173. ▪▪ Excellent review on the topic of developing cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulators for therapy of cystic fibrosis (CF).

- 15.Gabriel SE, Brigman KN, Koller BH, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ. Cystic fibrosis heterozygote resistance to cholera toxin in the cystic fibrosis mouse model. Science. 1994;266(5182):107–109. doi: 10.1126/science.7524148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Becq F. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators for personalized drug treatment of cystic fibrosis: progress to date. Drugs. 2010;70(3):241–259. doi: 10.2165/11316160-000000000-00000. ▪▪ Excellent review on the topic of developing CFTR modulators for therapy of CF.

- 17. Verkman AS, Lukacs GL, Galietta LJ. CFTR chloride channel drug discovery – inhibitors as antidiarrheals and activators for therapy of cystic fibrosis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006;12(18):2235–2247. doi: 10.2174/138161206777585148. ▪▪ Excellent review on the topic of targeting CFTR for therapy of CF or diarrheas.

- 18.Bobadilla JL, Macek M, Jr, Fine JP, Farrell PM. Cystic fibrosis: a worldwide analysis of CFTR mutations – correlation with incidence data and application to screening. Hum. Mutat. 2002;19(6):575–606. doi: 10.1002/humu.10041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerem E, Hirawat S, Armoni S, et al. Effectiveness of PTC124 treatment of cystic fibrosis caused by nonsense mutations: a prospective Phase II trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9640):719–727. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61168-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Goor F, Straley KS, Cao D, et al. Rescue of DeltaF508-CFTR trafficking and gating in human cystic fibrosis airway primary cultures by small molecules. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2006;290(6):L1117–L1130. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, et al. Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(44):18825–18830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904709106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, et al. Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(46):18843–18848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105787108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clancy JP, Rowe SM, Accurso FJ, et al. Results of a Phase IIa study of VX-809, an investigational CFTR corrector compound, in subjects with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del-CFTR mutation. Thorax. 2011;67(1):12–18. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Phuan PW, Yang B, Knapp J, et al. Cyanoquinolines with independent corrector and potentiator activities restore deltaF508-CFTR chloride channel function in cystic fibrosis. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011;80(4):683–693. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.073056. ▪ Discovery of dual-activity CFTR modulators to restore ΔF508-CFTR channel function in CF.

- 25.Morphy R, Rankovic Z. Designed multiple ligands. An emerging drug discovery paradigm. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48(21):6523–6543. doi: 10.1021/jm058225d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mills AD, Yoo C, Butler JD, Yang B, Verkman AS, Kurth MJ. Design and synthesis of a hybrid potentiator-corrector agonist of the cystic fibrosis mutant protein DeltaF508-CFTR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20(1):87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedemonte N, Lukacs GL, Du K, et al. Small-molecule correctors of defective DeltaF508-CFTR cellular processing identified by high-throughput screening. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115(9):2564–2571. doi: 10.1172/JCI24898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedemonte N, Tomati V, Sondo E, et al. Dual activity of aminoarylthiazoles on the trafficking and gating defects of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel caused by cystic fibrosis mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(17):15215–15226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.184267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pasyk S, Li C, Ramjeesingh M, Bear CE. Direct interaction of a small-molecule modulator with G551D-CFTR, a cystic fibrosis-causing mutation associated with severe disease. Biochem. J. 2009;418(1):185–190. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wellhauser L, Kim Chiaw P, Pasyk S, Li C, Ramjeesingh M, Bear CE. A small-molecule modulator interacts directly with deltaPhe508-CFTR to modify its ATPase activity and conformational stability. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;75(6):1430–1438. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.055608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varga K, Goldstein RF, Jurkuvenaite A, et al. Enhanced cell-surface stability of rescued DeltaF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) by pharmacological chaperones. Biochem. J. 2008;410(3):555–564. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Powers ET, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW, Balch WE. Biological and chemical approaches to diseases of proteostasis deficiency. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:959–991. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.114844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kalid O, Mense M, Fischman S, et al. Small molecule correctors of F508del-CFTR discovered by structure-based virtual screening. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2010;24(12):971–991. doi: 10.1007/s10822-010-9390-0. ▪ First report on structure-based virtual screening for small-molecule CFTR modulators.

- 34.Gabriel SE, Davenport SE, Steagall RJ, Vimal V, Carlson T, Rozhon EJ. A novel plant-derived inhibitor of cAMP-mediated fluid and chloride secretion. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:G58–G63. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.1.G58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuier M, Sies H, Illek B, Fischer H. Cocoa-related flavonoids inhibit CFTR-mediated chloride transport across T84 human colon epithelia. J. Nutr. 2005;135(10):2320–2325. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.10.2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li C, Dandridge KS, Di A, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid inhibits cholera toxin-induced secretory diarrhoea through CFTR-dependent protein interactions. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202(7):975–986. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050421. ▪ First paper on the discovery and characterization of CFTR–NHERF2-type 2 lysophosphatidic acid receptor-containing macromolecular complex.

- 37.Lin S, Yeruva S, He P, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates the intestinal brush border Na(+)/H(+) exchanger 3 and fluid absorption via LPA(5) and NHERF2. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2):649–658. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang W, Naren AP. Bioactive phospholipids signaling influences NHE3-dependent intestinal Na+ and fluid absorption: a macromolecular complex perspective. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2011;301(5):C982–C983. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00303.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung KT, Wong TY, Wei CI, Huang YW, Lin Y. Tannins and human health: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998;38(6):421–464. doi: 10.1080/10408699891274273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wongsamitkul N, Sirianant L, Muanprasat C, Chatsudthipong V. A plant-derived hydrolysable tannin inhibits CFTR chloride channel: a potential treatment of diarrhea. Pharm. Res. 2010;27(3):490–497. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-0040-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren A, Zhang W, Thomas HG, et al. A tannic acid-based medical food, Cesinex®, exhibits broad-spectrum antidiarrheal properties: a mechanistic and clinical study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012;57(1):99–108. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1821-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pariwat P, Homvisasevongsa S, Muanprasat C, Chatsudthipong V. A natural plant-derived dihydroisosteviol prevents cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;324(2):798–805. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tradtrantip L, Namkung W, Verkman AS. Crofelemer, an antisecretory antidiarrheal proanthocyanidin oligomer extracted from Croton lechleri, targets two distinct intestinal chloride channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;77(1):69–78. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.061051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Crutchley RD, Miller J, Garey KW. Crofelemer, a novel agent for treatment of secretory diarrhea. Ann. Pharmacother. 2010;44(5):878–884. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M658. ▪▪ Excellent review on the topic of using crofelemer for treating secretory diarrheas.

- 45.Bardhan PK, Khan WA, Ahmed S, et al. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of a novel anti-secretory anti-diarrheal agent Crofelemer (NP-303), in combination with a single oral dose of azithromycin for the treatment of acute dehydrating diarrhea caused by Vibrio cholerae. Presented at: 13th International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases in the Pacific Rim – Focused on Enteric Diseases; 6–9 April 2009; Kolkata, India. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma T, Thiagarajah JR, Yang H, et al. Thiazolidinone CFTR inhibitor identified by high-throughput screening blocks cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110(11):1651–1658. doi: 10.1172/JCI16112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sonawane ND, Muanprasat C, Nagatani R, Jr, Song Y, Verkman AS. In vivo pharmacology and antidiarrheal efficacy of a thiazolidinone CFTR inhibitor in rodents. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005;94(1):134–143. doi: 10.1002/jps.20228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muanprasat C, Sonawane ND, Salinas D, Taddei A, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Discovery of glycine hydrazide pore-occluding CFTR inhibitors: mechanism, structure–activity analysis, and in vivo efficacy. J. Gen. Physiol. 2004;124(2):125–137. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thiagarajah JR, Broadbent T, Hsieh E, Verkman AS. Prevention of toxin-induced intestinal ion and fluid secretion by a small-molecule CFTR inhibitor. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(2):11–19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sonawane ND, Zhao D, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Nanomolar CFTR inhibition by pore-occluding divalent polyethylene glycol-malonic acid hydrazides. Chem. Biol. 2008;15(7):718–728. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sonawane ND, Zhao D, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Lectin conjugates as potent, nonabsorbable CFTR inhibitors for reducing intestinal fluid secretion in cholera. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(4):1234–1244. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sonawane ND, Hu J, Muanprasat C, Verkman AS. Luminally active, nonabsorbable CFTR inhibitors as potential therapy to reduce intestinal fluid loss in cholera. FASEB J. 2006;20(1):130–132. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4818fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tradtrantip L, Sonawane ND, Namkung W, Verkman AS. Nanomolar potency pyrimido-pyrrolo-quinoxalinedione CFTR inhibitor reduces cyst size in a polycystic kidney disease model. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52(20):6447–6455. doi: 10.1021/jm9009873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snyder DS, Tradtrantip L, Yao C, Kurth MJ, Verkman AS. Potent, metabolically stable benzopyrimido-pyrrolo-oxazine-dione (BPO) CFTR inhibitors for polycystic kidney disease. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54(15):5468–5477. doi: 10.1021/jm200505e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Hostos EL, Choy RK, Nguyen T. Developing novel antisecretory drugs to treat infectious diarrhea. Future Med. Chem. 2011;3(10):1317–1325. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li C, Krishnamurthy PC, Penmatsa H, et al. Spatiotemporal coupling of cAMP transporter to CFTR chloride channel function in the gut epithelia. Cell. 2007;131(5):940–951. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaccolo M. Phosphodiesterases and compartmentalized cAMP signaling in the heart. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2006;85(7):693–697. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zaccolo M, Pozzan T. Discrete microdomains with high concentration of cAMP in stimulated rat neonatal cardiac myocytes. Science. 2002;295(5560):1711–1715. doi: 10.1126/science.1069982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Li C, Naren AP. CFTR chloride channel in the apical compartments: spatiotemporal coupling to its interacting partners. Integr. Biol. 2010;2(4):161–177. doi: 10.1039/b924455g. ▪▪ Excellent review on the topic of CFTR-containing macromolecular complexes.

- 60.Eckford PD, Bear CE. Targeting the regulation of CFTR channels. Biochem. J. 2011;435(2):e1–e4. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naren AP, Cobb B, Li C, et al. A macromolecular complex of beta 2 adrenergic receptor, CFTR, and ezrin/radixin/moesin-binding phosphoprotein 50 is regulated by PKA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100(1):342–346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135434100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh AK, Riederer B, Krabbenhöft A, et al. Differential roles of NHERF1, NHERF2, and PDZK1 in regulating CFTR-mediated intestinal anion secretion in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119(3):540–550. doi: 10.1172/JCI35541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Christian F, Szaszak M, Friedl S, et al. Small molecule AKAP/PKA interaction disruptors that activate PKA interfere with compartmentalized cAMP signaling in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(11):9079–9096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thorsen TS, Madsen KL, Rebola N, et al. Identification of a small-molecule inhibitor of the PICK1 PDZ domain that inhibits hippocampal LTP and LTD. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(1):413–418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902225107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fujii N, Haresco JJ, Novak KA, et al. A selective irreversible inhibitor targeting a PDZ protein interaction domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125(40):12074–12075. doi: 10.1021/ja035540l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fujii N, You L, Xu Z, et al. An antagonist of dishevelled protein–protein interaction suppresses beta-catenin-dependent tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67(2):573–579. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fujii N, Haresco JJ, Novak KA, et al. Rational design of a nonpeptide general chemical scaffold for reversible inhibition of PDZ domain interactions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17(2):549–552. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fujii N, Shelat A, Hall RA, Guy RK. Design of a selective chemical probes for Class I PDZ domains. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17(2):546–548. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang W, Penmatsa H, Ren A, et al. Functional regulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-containing macromolecular complexes: a small-molecule inhibitor approach. Biochem. J. 2011;435(2):451–462. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Websites

- 101.The median predicted survival age for CF patients. www.cff.org/AboutCF.

- 102.Atularen in clinical trial. www.cff.org/research/DrugDevelopmentPipeline/#CFTR_MODULATION.

- 103.VX-770 in clinical trial. www.cff.org/research/DrugDevelopmentPipeline/#CFTR_MODULATION.

- 104.VX-770 has been approved by US FDA to treat CF patients aged 6 or older with G551D mutation. www.cff.org/aboutCFFoundation/NewsEvents/2012NewsArchive/1-31-FDA-Approves-Kalydeco.cfm.

- 105.VX-809 in clinical trial. www.cff.org/research/DrugDevelopmentPipeline.

- 106.Plan for clinical trial using a combination of VX-770 and VX-809. www.cff.org/aboutCFFoundation/NewsEvents/7–29-VX-770-on-Track-for-New-Drug-Application.cfm.