Abstract

Cytokine dysregulation and decontrol of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latency by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection are potential mechanisms for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). We therefore assessed circulating blood levels in pre-diagnosis plasma or serum from 63 AIDS-related NHL cases 0.1 – 2.0 (median 1.0) years pre-NHL and 181 controls matched for CD4+ T-cell count. Cytokines were measured by Millipore 30-plex Luminex assays and cell-free EBV DNA detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Correlations in multiplex cytokine levels were summarized by factor analysis. Individual cytokines and their principal factors were analyzed for associations with NHL by conditional logistic regression. Cases had higher levels for 25 of the 30 cytokines. In analyses of cytokine profiles, cases had significantly higher scores for a principal factor primarily reflecting levels of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-13, and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (four gene products with coordinated transcription in vitro), as well as IL-1alpha. Epstein-Barr viremia was not significantly associated based on 113 evaluable samples without PCR inhibition. We found increases of T-helper type 2 interleukins and generalized elevations of other inflammatory cytokines and growth factors up to two years before AIDS-NHL. Cytokine-mediated hyperstimulation of B-cell proliferation may play a role in AIDS-related lymphomagenesis.

Cytokines are a diverse group of secreted proteins that are produced by and regulate cells of the immune system [1]. Their biological activities are both pleiotropic and redundant (i.e., each cytokine may act upon multiple molecular targets and multiple cytokines may elicit the same cellular response), in part due to overlapping features of their receptors and signal-transduction pathways. Moreover, expression and effects vary depending upon such factors as cellular characteristics, surrounding microenvironment, and concentrations of other cytokines.

Disruption of the cytokine signaling network is a key pathophysiologic feature of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [2]. Concomitant with the declining function of CD4 T helper cells, increasing levels of various cytokines stimulate B cell activation and proliferation. Replication of HIV and opportunistic infections, particularly the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), provides additional B cell stimulation, both by generating cytokine response as well as by direct actions of microbial antigens. Hence, blood levels of cytokines and EBV are markers of HIV disease progression as well as mediators of AIDS pathogenesis.

Apart from interfering with immune function, B cell hyperstimulation also has tropic consequences [3]. Generalized lymphadenopathy is an early sign of HIV infection. Increased DNA replication also generates opportunities for genetic errors, in part due to the lymphocyte-specific mechanisms for chromosomal rearrangement and somatic hypermutation that generate antibody diversity and specificity. Accumulation of errors that provide growth advantage and abrogation of apoptosis can lead to malignant transformation and clonal outgrowth, which manifests as non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). As the initiating factors in this process, alterations of cytokine signaling and EBV control may indicate severity of B cell hyperstimulation and risk of subsequent lymphoma.

Accordingly, we assessed these markers in blood samples obtained prior to diagnosis of AIDS-related NHL. Fifty-six cases had at least one matched control, with mean (median) CD4/mm3 of 176 (85) for cases and 166 (91) for controls (Table 1). All but three cytokines (G-CSF, MIP-1beta and GM-CSF) were detectable in at least 50% percent of samples, taking cases and controls together. Geometric means for detectable samples ranged from 1 pg/ml for IL-5 to over 24,000 pg/ml for RANTES (Table 2). EBV was detectable in 21 (19%) of 113 sera and acid-citrate-dextrose plasma samples, but the remaining plasma samples with heparin or other anticoagulants could not be assayed due to PCR inhibition.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases and controls

| Characteristic | Cases (n=63) | Controls (n=181) |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 59 (94) | 169 (93) |

| Age in years, median (IQR1) | 38 (29–44) | 38 (32–44) |

| White race, n (%) | 51 (81) | 151 (83) |

| CD4/mm3, median (IQR) | 85 (31–230) | 91 (16–252) |

| Year of NHL, median (IQR) | 1994 (1991–1998) | - |

| NHL subtype, n (%) | ||

| diffuse large B-cell | 27 (43) | - |

| primary brain | 11 (17) | - |

| Burkitt | 4 (6) | - |

| other/unknown | 21 (33) | -. |

interquartile range

Table 2.

Pre-diagnosis cytokine levels and matched odds ratios (mOR) for AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases and matched controls (N=244)

| Cytokine | Percent Detectable | Geometric Mean (Std Dev), pg/ml1 | mOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | |||

| N=244 | n=63 | n=181 | ||

| IL-1alpha | 71% | 131 (x/ 4.6) | 66 (x/ 4.5) | 1.6 (1.0–2.5) |

| IL-1beta | 70% | 2 (x/ 3.7) | 2 (x/ 3.1) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| IL-1ra | 87% | 334 (x/ 3.5) | 272 (x/ 3.4) | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) |

| IL-2 | 76% | 17 (x/ 4.1) | 13 (x/ 3.8) | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) |

| IL-4 | 52% | 102 (x/ 4.8) | 54 (x/ 4.9) | 1.4 (1.0–2.1) |

| IL-5 | 64% | 1 (x/ 4.6) | 1 (x/ 2.3) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) |

| IL-6 | 96% | 14 (x/ 5.2) | 10 (x/ 5.3) | 2.5 (1.3–4.8) |

| IL-7 | 90% | 6 (x/ 2.7) | 5 (x/ 2.6) | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) |

| IL-8 | 100% | 20 (x/ 6.6) | 15 (x/ 5.3) | 1.8 (0.8–3.8) |

| IL-10 | 98% | 26 (x/ 2.8) | 20 (x/ 2.6) | 1.2 (0.6–2.1) |

| IL-12p40 | 75% | 218 (x/ 2.5) | 218 (x/ 2.6) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| IL-12p70 | 51% | 5 (x/ 3.3) | 3 (x/ 2.8) | 1.7 (1.1–2.7) |

| IL-13 | 63% | 48 (x/ 3.5) | 27 (x/ 3.6) | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) |

| IL-15 | 61% | 14 (x/ 2.5) | 12 (x/ 2.6) | 2.0 (1.3–3.1) |

| IL-17 | 56% | 28 (x/ 2.5) | 23 (x/ 3.2) | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) |

| EGF | 78% | 82 (x/ 2.7) | 78 (x/ 2.6) | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) |

| Eotaxin | 96% | 148 (x/ 2.4) | 154 (x/ 2.3) | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) |

| Fractalkine | 57% | 243 (x/ 3.1) | 191 (x/ 2.7) | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) |

| G-CSF | 35% | 136 (x/ 2.7) | 187 (x/ 3.9) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| GM-CSF | 48% | 5 (x/ 3.3) | 3 (x/ 2.7) | 1.8 (1.2–2.9) |

| IFN-g | 64% | 11 (x/ 4.1) | 8 (x/ 3.3) | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) |

| IP-10 | 100% | 1650 (x/ 2.8) | 1270 (x/ 2.6) | 2.3 (1.1–4.6) |

| MCP-1 | 100% | 341 (x/ 3.0) | 305 (x/ 2.8) | 1.3 (0.6–2.5) |

| MIP-1a | 62% | 29 (x/ 4.8) | 38 (x/ 5.5) | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) |

| MIP-1b | 42% | 174 (x/ 4.5) | 164 (x/ 5.3) | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) |

| RANTES | 100% | 24600 (x/ 3.1) | 24500 (x/ 3.1) | 0.9 (0.4–1.8) |

| sCD40L | 99% | 7100 (x/ 3.2) | 7600 (x/ 3.1) | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) |

| TGFa | 76% | 22 (x/ 4.0) | 14 (x/ 2.5) | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) |

| TNFa | 100% | 13 (x/ 2.5) | 10x/ 2.3) | 1.4 (0.7–2.7) |

| VEGF | 88% | 105 (x/ 2.3) | 98 (x/ 2.4) | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) |

Excluding non-detectables

For 25 of the 30 cytokines, NHL cases had higher levels than their matched controls. The mORs significantly exceeded 1.0 for greater than median IL-6, IL-15 and GM-CSF (p<.01), as well as IL-1alpha, IL-12p70, IL-13, IP-10 and VEGF (p<.05) (Table 2). EBV PCR-positivity had a mOR of 1.6 (95% CI, 0.5–5.0), based on serum and evaluable plasma samples only.

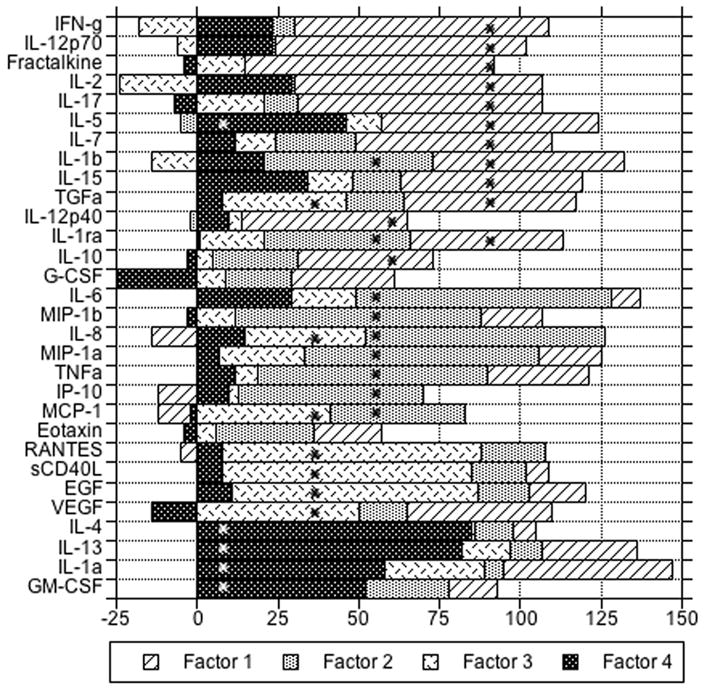

Factor analysis identified four principal cytokine factors in controls that had little overlap of salient loadings after rotation. Thirteen cytokines had salient loadings on Factor 1, nine on Factor 2 (including two from Factor 1), seven on Factor 3 (including one from Factor 1 and two from Factor 2), and five on Factor 4 (including one from Factor 1); two cytokines did not have salient loadings on the rotated factors (Figure).

Figure.

Rotated loadings (X 100) on four principal factors for log-transformed cytokine levels among controls, in descending order of salient loadings within factors. Asterisks indicate loadings greater than 0.36 for a given factor (i.e., salient).

In analyses of the cytokine principal factors, only Factor 4 was significantly associated with risk of subsequent NHL, with mOR 1.5 (95% CI, 1.1–2.2) per unit change. Associations with Factor 4 were similar for cases with blood collected less than (n=31) vs. greater than (n=32) 1.0 year pre-NHL, with mOR 1.5 (95% CI, 0.92–2.5) and 1.6 (95% CI, 0.96–2.6) per unit change, respectively. Associations of the other three principal factors were not statistically significant, with mORs 1.5 (p=.1) for Factor 1, 1.3 (p=.2) for Factor 2, and 1.3 (p=.4) for Factor 3. Analyzing the factors as quartiles, there was a significant linear trend only for Factor 4 with mOR vs. quartile 1 of 2.4 (95% CI, 0.7–8.0) for quartile 2, 2.9 (95% CI, 0.9–8.8) for quartile 3 and 3.3 (95% CI, 1.0–10.2) for quartile 4, adjusted for the other three factors (mOR 1.4 per quartile; 95% CI, 1.0–1.9). The cytokines with salient factor loadings for Factor 4 were IL-1alpha, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and GM-CSF (Figure).

Factor 4, which was significantly associated with risk for AIDS-NHL, includes three classic T-helper type 2 (Th2) cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13), pro-inflammatory IL-1alpha, and hematopoeitic growth factor GM-CSF. With the exception of the gene for IL-1alpha, the genes for the other four are all clustered in tandem orientation in a 650 kilobase DNA segment at chromosome 5q31, clonal deletion of which may occur in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia associated with alkylator chemotherapy [10]. A conserved non-coding sequence called CNS1 is a coordinate regulator of transcription at this locus [11]. Thus, the common regulation of circulating levels of their four gene products, as identified by our factor analysis, may have a chromosomal basis.

IL-4, also known as B-cell stimulatory factor 1 (BSF1), promotes proliferation and differentiation of activated B-cells and is a prime driver of Th2 polarization of CD4-positive T cells [12]. IL-5, also known as eosinophil differentiation factor (EDF), stimulates production and differentiation of eosinophils [13]. IL-13 is an important down-regulator of pro-inflammatory cytokines and induces immunoglobulin synthesis by B cells [14]. GM-CSF is an essential regulator of neutrophils and macrophages [15]. IL-1alpha is a potent pro-inflammatory mediator that is also produced by stimulated B cells [16]. While our analysis associated lymphoma risk with this group of markers collectively, it may be the case that only some have causal effects related to B-cell hyperproliferation and malignant transformation.

Several cytokines have been previously found to be increased prior to AIDS-lymphoma diagnosis in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). The B-cell growth factor sCD23, the anti-inflammatory IL-10 and the pleiotropic IL-6 have each been associated with NHL risk in various analyses [17–19]. While we did not measure sCD23, our non-significantly positive association with IL-10 and strongly significant association with IL-6 are consistent with these reports. Increases of circulating sCD27 and sCD30, two cytokine receptor molecules, have also been associated with NHL risk in the MACS [20, 21].

HIV infection has profound effects on the immune system and AIDS-NHL is relatively homogeneous as compared to NHL in the general population. Nevertheless, blood levels of cytokines and other immune stimulatory molecules have also been investigated as predictors of NHL risk in the absence of HIV, with varying results. In the EPIC Italy cohort, there was a significant association with levels of CD54 and an inverse association with IL2 and gamma interferon among 68 NHL cases with plasma drawn 2.1–10.4 years prior to diagnosis [22]. In the New York University Women’s Health Study, there was a significant association with sIL2r and an inverse association with IL13 among 92 NHL cases with serum drawn a median of 8.2 years prior to diagnosis [23]. In the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial, there was a significant association with sCD30 among 234 NHL cases with serum drawn 1–10 years prior to diagnosis [24]. The discrepancies among these studies may reflect the heterogeneity of NHL, highlighting both the utility and the limitations of AIDS-NHL as a model system for lymphoma etiology.

In summary, we found generalized elevations of Th1, Th2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors up to 2 years before AIDS-NHL, although only one of four principal factors was statistically significant. That the Factor 4 association was somewhat stronger (although not statistically significant) in the earlier samples drawn more than one year prior to NHL argues against disease bias as an explanation. While EBV viremia was not significantly predictive, our study had little statistical power in part due to PCR inhibition in heparin plasma samples. Cytokine hyperstimulation of B-cell proliferation may be an important etiologic pathway to AIDS-related lymphomagenesis.

METHODS

Patients

We identified AIDS-NHL cases (n=63) from three HIV-infected cohorts followed at the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI). Eight occurred in a cohort of 133 HIV-1-infected homosexual men [4], 39 were among 2126 HIV-1-infected hemophilia patients [5], and 16 were in a study of 2803 patients at AIDS treatment and clinical trial sites [6]. Institutional review boards at the NCI and collaborating institutions approved each cohort study, and all participants gave written informed consent.

The NHLs had been diagnosed between 1985 and 2004 (median, 1994; Table 1). We identified archived plasma (n=53 cases) or serum (n=10 cases) samples collected roughly one year before NHL diagnosis (range 0.1 – 2.0 yr). Up to three lymphoma-free controls per case (n=181 samples) were matched for cohort and sample type (i.e., plasma or serum) within the same time period, as well as age at diagnosis (+/− 5 years), race, sex, and CD4+ cells/mm3 at diagnosis (categorized as 0−, 100−, 200−, and 500−).

Cytokine and EBV assays

Cytokine levels were determined by Luminex fluorescent bead human cytokine immunoassays (MILLIPLEX MAP, Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA, USA). Thirteen cytokines were part of a high-sensitivity multiplex panel (GMCSF, IFNg, interleukin (IL)-1beta, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-13, and TNFalpha.), 16 were in a standard-sensitivity multiplex panel (EGF, eotaxin, fractalkine, G-CSF, IL-1alpha, IL-1ra, IL-12 (p40, free form), IL-15, IL-17, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta, soluble CD40L, TGFalpha, and VEGF), and one was measured as a single analyte (RANTES). Values below the limit of detection were assumed to be half of the minimum detectable level. Measurements on blinded replicate samples included with test samples had coefficients of variation between 10% and 46%.

Cell-free EBV DNA was detected by extracting 200 ul of sample using the Total Nucleic Acid Isolation protocol on the MagnaPure LC instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany) and performing quantitative real-time PCR for the p143 gene BNRF [7]. Amplification was considered to be inhibited when the average cycle threshold (Ct) for a spiked internal control sequence was more than two standard deviations from the longstanding average.

Statistical analysis

Geometric means and standard deviations of cytokine measurements greater than the limit of detection were calculated with Stata/SE 10.1 for Macintosh software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). To account for correlations among cytokines, we performed factor analysis to extract independent factors related to levels among controls, using SAS v9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The number of principal factors was based on examination of scree plots and Kaiser’s rule [8]. Correlations of cytokine levels with particular factors were determined as factor loadings, with a higher value indicating greater correlation and a negative loading meaning that the cytokine was inversely related to that factor. Factors were rotated by orthogonal Varimax transformation to obtain a simpler structure for interpretation; rotated values exceeding the root mean square factor loading (0.36) were considered to be salient.

Factor scores for principal factors were calculated for each subject as the sum of their standardized (mean 0, variance 1) cytokine levels times the respective standardized scoring coefficients from factor analysis. Since factor scores were themselves standardized, the parameter estimates are interpretable as multiples of their standard deviations [9].

We used conditional logistic regression analyses on matched sets to estimate odds ratios (mORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for association of case status with individual cytokines (categorized as undetectable, low and high based on median values for controls), and with the rotated principal factors as continuous measures. To account for possible non-linear associations, we also analyzed the factors in quartiles based on their values among controls, both as categorical variables and in tests for trend. Unconditional analyses adjusted for the matching variables yielded generally similar estimates of associations, so only results for the conditional models are presented. Regression analyses were performed using Stata and SAS software. All significance tests were two-sided and p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.Khaled AR, Durum SK. The role of cytokines in lymphocyte homeostasis. Biotechniques. 2002;(Suppl):40–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambinder RF, Bhatia K, Martinez-Maza O, et al. Cancer biomarkers in HIV patients. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:531–537. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833f327e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaidano G, Carbone A, Dalla-Favera R. Pathogenesis of AIDS-related lymphomas: molecular and histogenetic heterogeneity. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:623–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goedert JJ, Sarngadharan MG, Biggar RJ, et al. Determinants of retrovirus (HTLV-III) antibody and immunodeficiency conditions in homosexual men. Lancet. 1984;2:711–716. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92624-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goedert JJ, Kessler CM, Aledort LM, et al. A prospective study of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and the development of AIDS in subjects with hemophilia. NEnglJMed. 1989;321:1141–1148. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910263211701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nawar E, Mbulaiteye SM, Gallant JE, et al. Risk factors for Kaposi’s sarcoma among HHV-8 seropositive homosexual men with AIDS. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:296–300. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luderer R, Kok M, Niesters HG, et al. Real-time Epstein-Barr virus PCR for the diagnosis of primary EBV infections and EBV reactivation. Mol Diagn. 2005;9:195–200. doi: 10.1007/BF03260091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaiser HF. The Application of Electronic Computers to Factor Analysis. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane PW, Nelder JA. Analysis of covariance and standardization as instances of prediction. Biometrics. 1982;38:613–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Beau MM, Lemons RS, Espinosa R, 3rd, et al. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-5 map to human chromosome 5 in a region encoding growth factors and receptors and are deleted in myeloid leukemias with a del(5q) Blood. 1989;73:647–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loots GG, Locksley RM, Blankespoor CM, et al. Identification of a coordinate regulator of interleukins 4, 13, and 5 by cross-species sequence comparisons. Science. 2000;288:136–140. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yokota T, Otsuka T, Mosmann T, et al. Isolation and characterization of a human interleukin cDNA clone, homologous to mouse B-cell stimulatory factor 1, that expresses B-cell-and T-cell-stimulating activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:5894–5898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell HD, Tucker WQ, Hort Y, et al. Molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the gene encoding human eosinophil differentiation factor (interleukin 5) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:6629–6633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minty A, Chalon P, Derocq JM, et al. Interleukin-13 is a new human lymphokine regulating inflammatory and immune responses. Nature. 1993;362:248–250. doi: 10.1038/362248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metcalf D. The molecular biology and functions of the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factors. Blood. 1986;67:257–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lord PC, Wilmoth LM, Mizel SB, et al. Expression of interleukin-1 alpha and beta genes by human blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1312–1321. doi: 10.1172/JCI115134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yawetz S, Cumberland WG, van der Meyden M, et al. Elevated serum levels of soluble CD23 (sCD23) precede the appearance ofacquired immunodeficiency syndrome--associated non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood. 1995;85:1843–1849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breen EC, Boscardin WJ, Detels R, et al. Non-Hodgkin’s B cell lymphoma in persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is associated with increased serum levels of IL10, or the IL10 promoter -592 C/C genotype. Clin Immunol. 2003;109:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breen EC, van der Meijden M, Cumberland W, et al. The development of AIDS-associated Burkitt’s/small noncleaved cell lymphoma is preceded by elevated serum levels of interleukin 6. Clin Immunol. 1999;92:293–299. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breen EC, Fatahi S, Epeldegui M, et al. Elevated serum soluble CD30 precedes the development of AIDS-associated non-Hodgkin’s B cell lymphoma. Tumour Biol. 2006;27:187–194. doi: 10.1159/000093022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widney D, Gundapp G, Said JW, et al. Aberrant expression of CD27 and soluble CD27 (sCD27) in HIV infection and in AIDS-associated lymphoma. Clin Immunol. 1999;93:114–123. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saberi Hosnijeh F, Krop EJ, Scoccianti C, et al. Plasma cytokines and future risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL): a case-control study nested in the Italian European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1577–1584. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu Y, Shore RE, Arslan AA, et al. Circulating cytokines and risk of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a prospective study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1323–1333. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9560-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purdue MP, Lan Q, Martinez-Maza O, et al. A prospective study of serum soluble CD30 concentration and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2009;114:2730–2732. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-217521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]