Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this research was to calibrate an item bank for a computerized adaptive test (CAT) of asthma impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL), test CAT versions of varying lengths, conduct preliminary validity testing, and evaluate item bank readability.

Methods

Asthma Impact Survey (AIS) bank items that passed focus group, cognitive testing, and clinical and psychometric reviews were administered to adults with varied levels of asthma control. Adults self-reporting asthma (N=1106) completed an Internet survey including 88 AIS items, the Asthma Control Test (ACT), and other HRQOL outcome measures. Data were analyzed using classical and modern psychometric methods, real-data CAT simulations, and known groups validity testing.

Results

A bi-factor model with a general factor (asthma impact) and several group factors (cognitive function, fatigue, mental health, physical function, role function, sexual function, self-consciousness/stigma, sleep, and social function) was tested. Loadings on the general factor were above 0.5 and were substantially larger than group factor loadings, and fit statistics were acceptable. Item functioning for most items and fit to the model was acceptable. CAT simulations demonstrated several options for administration and stopping rules. AIS distinguished between respondents with differing levels of asthma control.

Conclusions

The new 50-item AIS item bank demonstrated favorable psychometric characteristics, preliminary evidence of validity, and accessibility at moderate reading levels. Developing item banks for CAT can improve the precise, efficient, and comprehensive monitoring of asthma outcomes, and may facilitate patient-centered care.

Keywords: asthma control, Asthma Impact Survey, item response theory, patient-reported outcome, health-related quality of life

INTRODUCTION

The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program’s (NAEPP) Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma recommends regular patient-based assessment and monitoring of the impact of asthma on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [1,2]. A variety of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures have been developed to capture the impact of asthma and its treatment [3]. PRO measures are typically applied in clinical trials, effectiveness research, and research on quality of care to determine whether treatments are doing more good than harm, health and quality of life are improving or worsening, or specific asthma subgroups differ. However, there remains a need for practical, efficient, and precise tools for routine use in clinical practice [1,2].

Modern psychometric methods (e.g., item response theory (IRT)) and computerized adaptive testing (CAT) can improve HRQOL measures [4,5]. CAT mimics what an experienced clinician would do while assessing a patient, by directing questions at the individual’s functional level. It employs a simple form of artificial intelligence that selects questions tailored to the test-taker; shortens or lengthens the test to achieve the desired precision; and scores everyone on a standard metric so that results can be compared. CAT applications require a large set of items (banks) in any one functional area; items that consistently scale along a dimension of low to high functional proficiency; and rules guiding starting, stopping and scoring procedures [4].

During the last decade, CAT applications have been increasingly used in the assessment of health outcomes [6–12]. Computer-based health outcomes measures can play an important role in patient monitoring (both in-clinic and remote) and disease management. Although some research has applied IRT methods in asthma measurement [12–16], there are no published studies applying these methods to the development of a CAT for adult asthma patients outside of our own preliminary work [17].

This research documents work underlying the development of a dynamic survey, the DYNHA® Asthma Impact Survey (AIS™), which is to our knowledge the first CAT for adult asthma impact assessment. The objective of this research was to calibrate an item bank for a computerized adaptive test (CAT) of asthma impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL), test CAT versions of varying lengths, conduct preliminary validity testing, and evaluate item bank readability. Asthma Impact Survey (AIS) bank items that passed focus group, cognitive testing, and clinical and psychometric reviews [18] were administered to adults with varied levels of asthma control. Data were analyzed using confirmatory factor analyses for categorical data and item response theory (IRT) methods. CAT simulation studies were then conducted to assess the agreement between scores from different versions of a shorter adaptive test and scores based on the total AIS item bank.

METHODS

Sample

Participants were self-reported adult asthma sufferers from an online consumer health panel (Polimetrix) quota sampled to reflect national asthma prevalence estimates for gender and race/ethnicity distributions and representation across asthma control levels. Sampling criteria included age (≥ 18 years), language (able to read and write in English), diagnosis (self-reported; “Yes” to the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you have asthma?”), and asthma symptoms within the past 12 months. Asthma within the past 12 months was defined by a “yes” response to at least one of the following four items: In the past 12 months, have you had: (a) …a sudden episode or recurrent episode of coughing, wheezing (high-pitched whistling sounds when breathing out), or shortness of breath?, (b) …colds that “go to the chest” or take more than 10 days to get over?, (c) …coughing, wheezing, or shortness of breath during a particular season or time of the year?, or (d) …coughing, wheezing, or shortness of breath in certain places or when exposed to certain things (e.g., animals, tobacco smoke, perfumes)? Current smokers, those reporting current depression, congestive heart failure, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, pneumonia, and respiratory conditions other than asthma, and those currently under treatment for sinusitis were excluded from the study. To ensure adequate representation across control levels, the Asthma Control Test (ACT™) [19, 20] was fielded in the screening survey. Potential participants were recruited from Polimetrix’s database of more than one million U.S. residents who have previously enrolled in their nationwide panel through a variety of methods, such as Random Digit Dialing, invitations via web newsletters, and web polling.

Measures

Developmental Asthma Impact Survey (AIS™) Item Bank

It consisted of a bank of 88 Likert-type items covering the following content areas relevant to asthma impact: cognitive function, fatigue, financial, mental health, physical function, role function, sexual function, general social support, stigma, sleep, and social function. The AIS item bank includes 37 disease impact items developed by QualityMetric and tested across several conditions, with additional asthma-related items developed based on focus group, cognitive testing, and clinical and psychometric reviews [18].

Asthma Control Test (ACT™)

It is a five-item survey to assess dimensions underlying asthma control (asthma symptoms, utilization of rescue medications, and the impact of asthma on everyday functioning) [19, 20]. ACT scores range from 5 (poorly controlled) to 25 (well controlled). An ACT score ≤ 19 indicates asthma control problems.

SF-12v2® Health Survey (SF-12v2®)

It is a 12-item short-form generic survey that measures functional health and well-being, and yields an eight-scale health domain score profile as well as physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores. Higher scores are indicative of better health [21, 22].

Marks’ Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ-M™)

It is a 20-item survey that measures quality of life in adults with asthma. Total AQLQ scores and subscale scores for breathlessness, mood disturbance, social disruption, and concerns for health are calculated on a scale of 0 (no impairment of quality of life) to 4 (maximum impairment) [23].

ITG-Asthma Short Form (ITG-ASF™)

It is a 15-item survey that measures quality of life in adults with asthma, and yields a total score plus five individual scale scores ranging from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better health [24].

Background Information Survey

It is a 28-item module assessing participant demographics, symptom frequency, missed work days, and care utilization.

Chronic Conditions Checklist

It is a two-item checklist assessing presence of co-existing conditions: Has a doctor ever told you that you had any of the following conditions?, and Do you now have any of the following conditions?

Procedure

Panelists received a brief description of the study via email invitation from Polimetrix. Interested respondents selected “Begin Survey” on the e-mail invitation, which opened a web browser link to a pre-screening survey. Panelists who met eligibility criteria were directed to a Polimetrix HIPAA-compliant Internet portal to complete the online survey. The study protocol was approved by New England IRB (#07-055), and all participants provided informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Analyses

The approach to item bank development followed that described in previous studies [9, 25]. Frequency distributions were examined to identify items with extreme missing data or skewness for exclusion.

A series of factor analytic models including single and bi-factor models were evaluated. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was selected because initial AIS bank content was previously tested [18]. Assumptions of unidimensionality and local independence were tested through CFA for categorical data using Mplus software with weighted least squares estimation with robust standard errors and mean- and variance-adjusted X2 statistics (WLSMV) [26, 27]. Polychoric correlations were used as input to the factor analyses [28]. To test for local independence we evaluated residual correlations among items in a one-factor model. High residual correlations (> 0.20 [25]) suggest that there is dependence among items, and require further analyses [5]. Overall model fit was evaluated using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) as implemented for categorical data [27, 29].

Based on initial results from the one-factor model and given that asthma can impact varied areas of health (so an instrument constructed to assess this broad construct must contain items that differ by content and cover a wide range of impact), a bi-factor model tested whether these data have a strong enough common factor for a unidimensional IRT solution [30]. In a bi-factor model, each item is expected to load on a general factor that underlies all the items and is the broader construct a researcher is interested in measuring. In addition, an item can load on a group factor that is more conceptually narrow. A bi-factor model with a general factor (asthma impact) and several group factors (cognitive function, fatigue, mental health, physical function, role function, sexual function, self-consciousness/stigma, sleep, and social function) was tested.

TestGraf was used to examine item characteristic curves (ICCs) for each item [31]. Heuristic examination of ICCs allows for the identification of poor items and response options. Poor items may be dropped from the model, or response options that do not discriminate one response from another may be collapsed in further analyses [7].

Item parameters were estimated using the generalized partial credit model (GPCM) [32] with Parscale [33]. Item fit to the model was assessed by comparing expected and observed item frequency distributions at varying score levels, and calculating overall fit statistics [32, 34]. Item information functions were calculated from the IRT model parameters using SAS V9 [35]. The item information function is an index of precision and is used to select questions that are informative at particular score ranges [4].

Next, tests of differential item functioning (DIF) were used to identify systematic errors due to a group bias [36]. DIF occurs when respondents from different groups at the same level of the latent trait have a different probability of response selection. Using an ordinal logistic regression model [37], tests of DIF were conducted for gender, age, race, ethnicity, educational level, symptom frequency, and asthma severity. The coefficient of determination (R2), defined as the proportion of variation explained by the logistic regression model [38] was used to evaluate the magnitude of DIF. A significant effect of the independent variable or interaction effect (between the independent variable and the sum score) and an increase in R2 > 0.03 indicated DIF. Items with DIF were excluded from the model.

CAT testing algorithms were developed and after rescaling the IRT score (theta, θ) to a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10, real data simulations were conducted [see, e.g., Ware et al. (39)]. This approach mimics the item selection and scoring strategy of the true CAT but uses already collected data as input. This approach also allowed us to evaluate survey “stopping rules” (e.g., defined by number of items or content coverage) before wide-scale administration of the final CAT survey. Several CAT versions were tested in relation to an asthma impact score (theta, θ) estimated using all items in the bank (full bank). CAT-5 administered AIS1, allowed the computer to choose freely among the remaining items in the bank based on information, and stopped after the administration of five items. CAT-9C (content balanced) administered AIS1, forced the computer to select one most informative item from each of the content areas represented in the bank, and stopped after the administration of nine items. CAT-9 administered AIS1, allowed the computer to choose freely among the remaining items in the bank based on information, and stopped after the administration of nine items. CAT-95% CI administered AIS1, allowed the computer to choose freely among the remaining items in the bank based on information, and stopped after achieving 95% confidence interval (CI) around the score estimate.1 Descriptive statistics were calculated for alternate CAT versions, and product-moment and intra-class correlations were calculated to assess the extent to which simulated CAT versions accurately reproduced the IRT-based latent trait score (estimated from the full bank).

For each CAT version, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate asthma impact scores for respondents differing on Asthma Control Test (ACT) scores (>19 controlled, 16–19 somewhat controlled, ≤ 15 uncontrolled). We expected to observe higher scores (greater asthma impact) on all CAT versions among respondents with lower levels of asthma control. Relative validity (RV) coefficients were computed by dividing the F-statistics of each scale by the largest F-statistic observed among all scales [40]. We expected RV coefficients to be higher for the IRT-Total AIS scale than other CAT versions.

Finally, readability of the final DYNHA AIS item bank was assessed using the Flesch-Kincaid Readability Tests (Reading Ease and Grade Level) [41–43].

RESULTS

The sample included 1106 adults self-reporting asthma, varied in terms of age (M=47 years, range 18–83 years), gender (67% female), and asthma control (46% controlled, 30% somewhat controlled, 24% uncontrolled) (see Table 1). Eighty-four percent of the sample reported current use of at least one asthma medication.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N=1106)

| Females n (%) |

Males n (%) |

Total n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma Control | |||

| Controlled | 300 (40%) | 202 (56%) | 502 (46%) |

| Somewhat controlled | 239 (32%) | 96 (26%) | 335 (30%) |

| Uncontrolled | 205 (28%) | 64 (18%) | 269 (24%) |

| Age | |||

| 18–24 years | 51 (7%) | 12 (3%) | 63 (6%) |

| 25–34 years | 127 (17%) | 39 (11%) | 166 (15%) |

| 35–44 years | 154 (21%) | 81 (22%) | 235 (21%) |

| 45–54 years | 191 (26%) | 97 (27%) | 288 (26%) |

| 55–64 years | 154 (21%) | 87 (24%) | 241 (21%) |

| 65–74 years | 49 (7%) | 36 (10%) | 85 (8%) |

| 75+ years | 18 (2%) | 10 (3%) | 28 (3%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 51 (7%) | 21 (6%) | 72 (7%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 693 93%) | 341 (94%) | 1034 (93%) |

| Race | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 6 (<1%) | 3 (<1%) | 9 (<1%) |

| Asian | 9 (1%) | 11 (3%) | 20 (2%) |

| Black or African American | 48 (6%) | 16 (4%) | 64 (6%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (<1%) |

| White | 651 (88%) | 317 (88%) | 968 (88%) |

| Multi-racial | 14 (2%) | 6 (2%) | 20 (2%) |

| Unknown or not reported | 15 (2%) | 9 (2%) | 24 (2%) |

| Education Level | |||

| Elementary | 0 (0%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Some high school | 3 (<1%) | 3 (<1%) | 6 (<1%) |

| Graduated high school/GED | 87 (12%) | 20 (6%) | 107 (10%) |

| Some college or technical school | 290 (39%) | 128 (35%) | 418 (38%) |

| College graduate | 218 (29%) | 95 (26%) | 313 (28%) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 143 (19%) | 113 (31%) | 256 (23%) |

| Other | 3 (<1%) | 2 (<1%) | 5 (<1%) |

One item (During the past 4 weeks, how often have you awakened in the morning with asthma symptoms that did not improve within 15 minutes of using your rescue inhaler?) was dropped from the model due to substantial missing data (>10%). For the remainder of items, all item response categories were used and no items were dropped due to extreme skewness (more than 95% responses in one category).

As expected an initial one-factor model including all items from 1106 respondents with complete data on the DYNHA AIS, ACT, AQLQ-M, and ITG-ASF items, did not converge. Symptom frequency and rescue inhaler use items were dropped from the model. Also, since some bank items were very similar in content (e.g., AIS22 “In the past 4 weeks, how often did your asthma make it difficult for you to focus your attention on other things?” versus EXP_AIS22 “In the past 4 weeks, how often did your asthma make it difficult for you to focus your attention?”) and could result in high residual correlations, experimental items were also dropped from the factor analytic model. The AQLQ-M and ITG-ASF were also dropped from the model since they are proprietary tools that contained repetitive content.

A one-factor model was estimated with the remaining set of items (k=55). Although factor loadings ranged from 0.57–0.91, fit statistics were not strong (RMSEA=.165, CFI=.650) (see Table 2). Also, high residual correlations were observed for a few item pairs. Next, a bi-factor model was estimated on the same set of items. Modification indices suggested potential model improvements, and the final model allowed cross-loadings for two items and correlations between the group factor for role function and group factors for physical function and fatigue. This model fit the data well (RMSEA=0.074, CFI=0.900; see Table 2). Factor loadings on the general factor were not appreciably different from the one-factor model (range 0.58 – 0.89) and were substantially larger than loadings on the group factors. This evidence suggests that the multi-faceted concept of asthma impact may be scaled using a unidimensional IRT model [30].

Table 2.

AIS Item Bank Factor Structure (k=55)

| One-factor Model |

Bi-factor Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Item Label and Abbreviated Content | Loadings on single factor |

Loadings on general factor |

Loadings on group factors |

| Cognitive Function (COG, k=2) | AIS5 (limited ability to concentrate on work) | 0.855 | 0.869 | 0.356 |

| AIS22 (difficult to focus attention) | 0.847 | 0.862 | 0.356 | |

| Fatigue (FATIG, k=4) | AIS8 (left you too tired to do work) | 0.843 | 0.838 | 0.348 |

| AIS14 (lie down and rest) | 0.784 | 0.781 | 0.326 | |

| AIS23 (keep you in bed) | 0.812 | 0.817 | 0.257 | |

| EXP_FTG2 (feel tired) | 0.823 | 0.831 | 0.262 | |

| Mental Health (MH, k=11) | AIS4 (felt fed up or frustrated) | 0.805 | 0.770 | 0.436 |

| AIS13 (make you angry) | 0.792 | 0.749 | 0.458 | |

| AIS17 (going to lose control) | 0.825 | 0.813 | 0.284 | |

| AIS21 (get tense) | 0.822 | 0.790 | 0.401 | |

| AIS27 (afraid of letting others down) | 0.805 | 0.825 | 0.116 | |

| AIS29 (feel irritable) | 0.821 | 0.801 | 0.348 | |

| AIS30 (feel frustrated) | 0.829 | 0.790 | 0.457 | |

| AIS35 (feel desperate) | 0.81 | 0.787 | 0.390 | |

| EXP_MH1 (worry about having an attack) | 0.734 | 0.719 | 0.356 | |

| EXP_MH3 (make you anxious) | 0.77 | 0.727 | 0.459 | |

| EXP_MH5 (feel depressed) | 0.759 | 0.752 | 0.269 | |

| Physical Function (PF, k=6) | EXP_PF5 (difficult to exercise) | 0.817 | 0.719 | 0.540 |

| EXP_PF6 (difficult to be active with family) | 0.814 | 0.793 | 0.332 | |

| EXP_PF7 (limited recreation involving physical activity) | 0.854 | 0.744 | 0.570 | |

| EXP_PF8 (limited ability to participate in sports) | 0.793 | 0.672 | 0.597 | |

| REX_PF9 (limited ability to walk 100 yards) | 0.756 | 0.701 | 0.445 | |

| REX_PF10 (limited ability to walk more than one mile) | 0.755 | 0.679 | 0.509 | |

| Role Function (RF, k=13) | AIS1 (limit usual activities) | 0.834 | 0.803 | 0.314 |

| AIS6 (difficulty performing work) | 0.909 | 0.860 | 0.367 | |

| AIS10 (keep you from getting as much done) | 0.882 | 0.828 | 0.395 | |

| AIS12 (cancel work or daily activities) | 0.823 | 0.814 | 0.223 | |

| AIS18 (restrict usual daily activities) | 0.904 | 0.844 | 0.421 | |

| AIS20 (restrict recreational activities) | 0.835 | 0.774 | 0.134 (0.354 PF) | |

| AIS25 (need help handling routine tasks) | 0.817 | 0.796 | 0.286 | |

| AIS26 (interfered with leisure activities) | 0.788 | 0.733 | 0.145 (0.323 PF) | |

| AIS28 (productivity reduced by half or more) | 0.822 | 0.792 | 0.311 | |

| AIS31 (limit ability to work, study, do chores) | 0.891 | 0.822 | 0.440 | |

| AIS32 (make simple tasks hard to complete) | 0.848 | 0.785 | 0.440 | |

| AIS36 (avoid traveling) | 0.827 | 0.845 | 0.078 | |

| EXP_RF1 (avoid spending time outdoors) | 0.693 | 0.700 | 0.128 | |

| Self-Conscious/Stigma (SC/STIG, k=4) | EXP_SC1 (embarrassed taking medication in public) | 0.565 | 0.579 | 0.288 |

| EXP_SC2 (embarrassed by coughing) | 0.631 | 0.642 | 0.485 | |

| EXP_STG1 (others avoid you) | 0.74 | 0.745 | 0.428 | |

| EXP_STG2 (people distances themselves from you) | 0.679 | 0.677 | 0.644 | |

| Sex Function (SEX, k=2) | EXP_SEX1 (avoid sexual activity) | 0.786 | 0.726 | 0.614 |

| EXP_SEX2 (limited your enjoyment of sexual activity) | 0.785 | 0.734 | 0.614 | |

| Sleep (SLP, k=5) | EXP_SLP1 (trouble sleeping through the night) | 0.821 | 0.711 | 0.642 |

| EXP_SLP2 (wake up coughing) | 0.668 | 0.617 | 0.535 | |

| EXP_SLP4 (wake up short of breath) | 0.756 | 0.683 | 0.549 | |

| EXP_SLP5 (had too little sleep) | 0.833 | 0.762 | 0.533 | |

| REX_SLP6 (difficulty getting to sleep) | 0.743 | 0.708 | 0.460 | |

| Social Function (SF, k=8) | AIS3 (interfered with how you dealt with family, friends) | 0.79 | 0.819 | −0.027 |

| AIS7 (avoid social or family activities) | 0.806 | 0.807 | 0.394 | |

| AIS9 (felt like a burden on others) | 0.806 | 0.843 | −0.137 | |

| AIS11 (avoid being around people) | 0.825 | 0.827 | 0.388 | |

| AIS16 (miss family, social, or leisure activities) | 0.87 | 0.889 | 0.219 | |

| AIS37 (place stress on your relationships) | 0.812 | 0.835 | 0.102 | |

| EXP_SF1 (avoid going places) | 0.715 | 0.724 | 0.326 | |

| EXP_SF3 (unable to go to social activities) | 0.778 | 0.790 | 0.313 | |

| PF with RF: | 0.439 | |||

| FATIG with RF: | 0.563 | |||

| Model Fit Statistics: | Chi square: 4870.308 | Chi square: 1615.167 | ||

| df=160 | df=229 | |||

| p =.0000 | p =.0000 | |||

| CFI: .650 | CFI: .900 | |||

| TLI: .965 | TLI: .993 | |||

| RMSEA: .165 | RMSEA: .074 | |||

| WRMR: 3.386 | WRMR: 1.473 | |||

NOTE: Items shown in gray did not make it into the final bank (based on additional results).

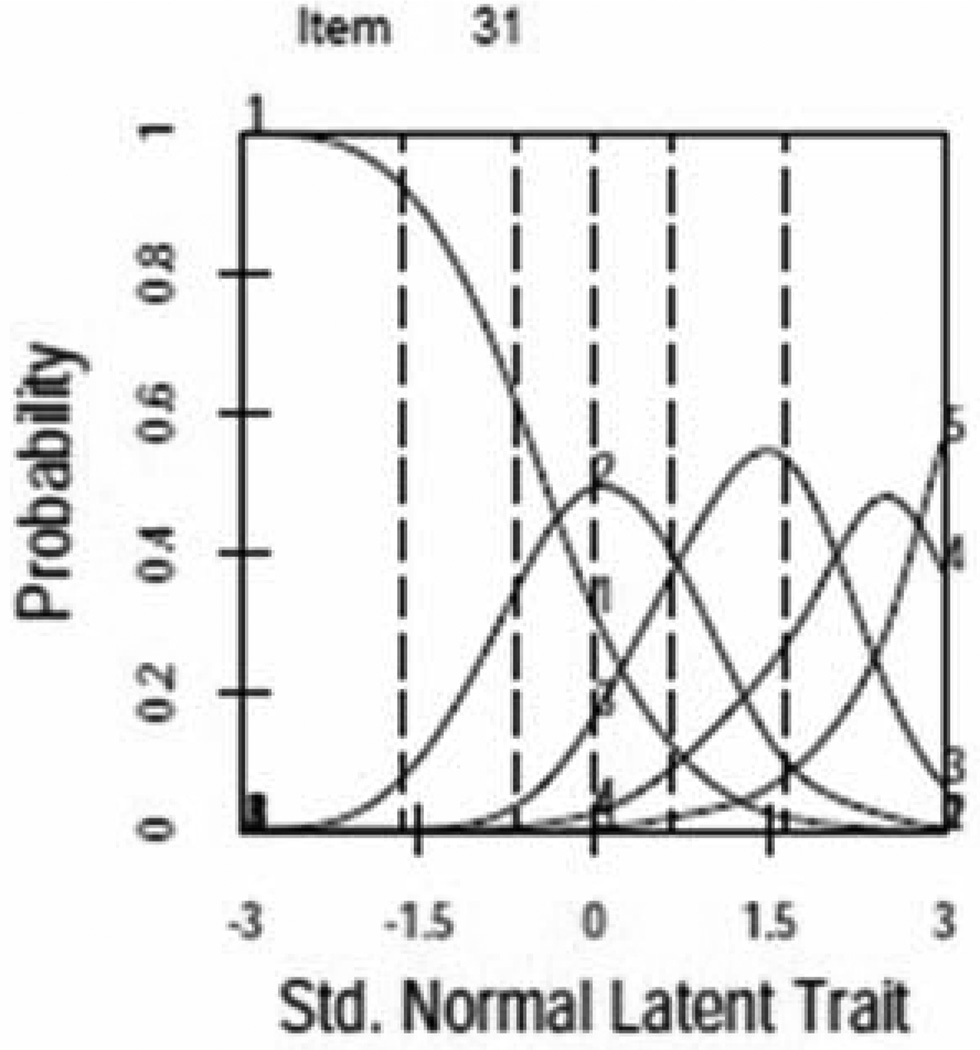

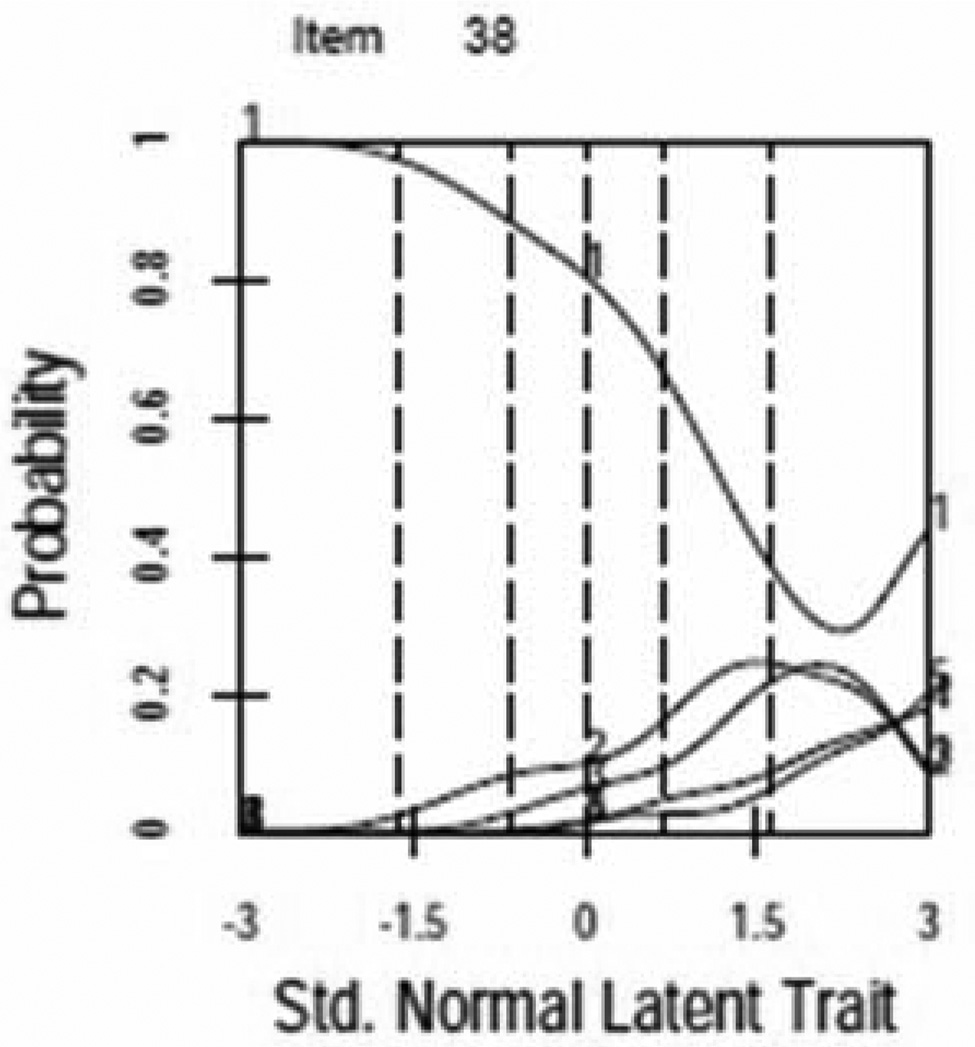

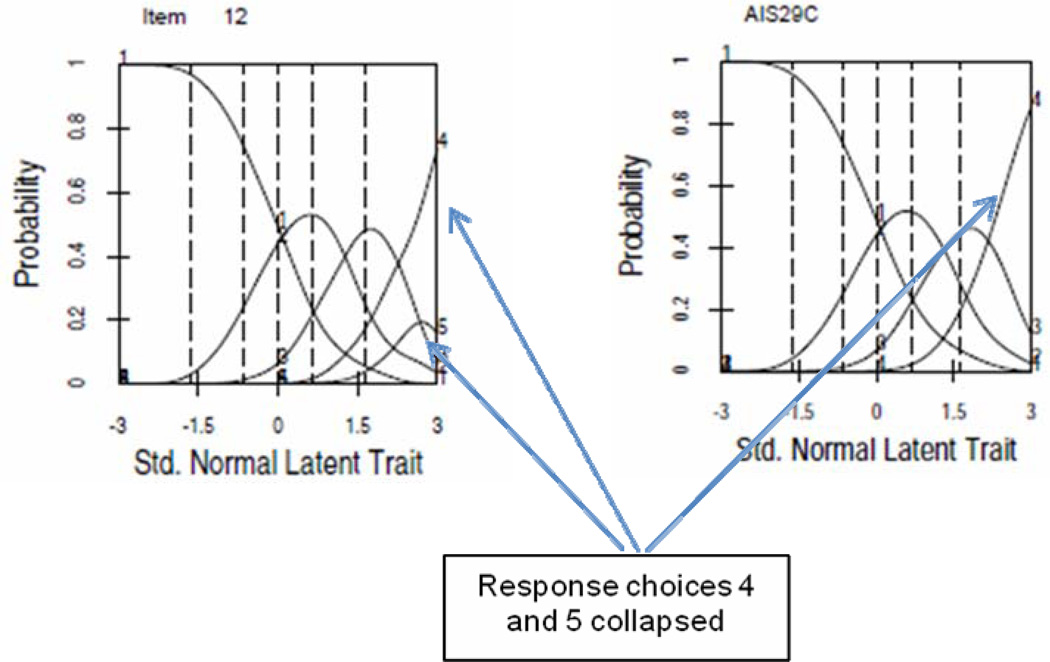

For most items ICCs demonstrated a unique and unequivocal relationship to the latent trait with one clear maximum. Figure 1 provides examples of items with properly functioning (Figure 1a,) and poorly functioning (Figure 1b) response curves. Response categories were collapsed for several items with poorly functioning curves (see improvement in Figure 1c, see Table 3 for final item collapsing). Two additional items were dropped due to poor performance.

Figure 1.

Item Characteristic Curves (ICCs)

a. AIS Item with Properly Functioning ICC

b. AIS Item with Poorly Functioning ICC

c. AIS Item Pre- and Post- Collapsed Response Options

Table 3.

Final AIS Item Parameters (k=50)

| Domain | Item Text | Response Options |

Number of Options |

Slope | Minimum Threshold |

Maximum Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Functioning (k=2) | AIS5 (limited ability to concentrate on work) | a | 5 | 2.62 | 0.20 | 2.53 |

| AIS22 (difficult to focus attention) | b | 5 | 2.37 | 0.08 | 2.13 | |

| Fatigue (k=4) | AIS8 (left you too tired to do work) | a | 5 | 2.47 | 0.05 | 2.55 |

| AIS14 (lie down and rest) | c | 5 | 2.18 | −0.58 | 2.61 | |

| AIS23 (keep you in bed) | b | 4 | 2.14 | 1.35 | 2.49 | |

| EXP_FTG2 (feel tired) | a | 5 | 2.03 | −0.52 | 1.99 | |

| Mental Health (k=11) | AIS4 (felt fed up or frustrated) | a | 5 | 1.55 | 0.12 | 1.83 |

| AIS13 (make you angry) | c | 5 | 1.46 | 0.72 | 2.23 | |

| AIS17 (going to lose control) | c | 5 | 2.02 | 0.93 | 2.53 | |

| AIS21 (get tense) | b | 5 | 1.91 | 0.13 | 2.60 | |

| AIS27 (afraid of letting others down) | a | 5 | 1.87 | 0.73 | 2.03 | |

| AIS29 (feel irritable) | a | 4 | 2.03 | 0.13 | 1.78 | |

| AIS30 (feel frustrated) | a | 5 | 1.90 | −0.03 | 2.06 | |

| AIS35 (feel desperate) | c | 5 | 1.82 | 1.02 | 2.70 | |

| EXP_MH1 (worry about having an attack) | d | 5 | 1.19 | 0.19 | 2.31 | |

| EXP_MH3 (make you anxious) | d | 5 | 1.46 | 0.23 | 2.58 | |

| EXP_MH5 (feel depressed) | d | 5 | 1.57 | 0.73 | 2.69 | |

| Physical Functioning (k=5) | EXP_PF5 (difficult to exercise) | d | 4 | 1.56 | −0.80 | 0.74 |

| EXP_PF6 (difficult to be active with family) | d | 5 | 1.88 | 0.22 | 2.18 | |

| EXP_PF8 (limited ability to participate in sports) | d | 4 | 1.30 | 0.09 | 1.60 | |

| REX_PF9 (limited ability to walk 100 yards) | d | 5 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.85 | |

| REX_PF10 (limited ability to walk more than one mile) | d | 4 | 1.21 | 0.25 | 1.62 | |

| Role Functioning (k=13) | AIS1 (limit usual activities) | e | 5 | 2.61 | −0.34 | 2.50 |

| AIS6 (difficulty performing work) | a | 4 | 3.93 | −0.13 | 1.75 | |

| AIS10 (keep you from getting as much done) | a | 5 | 3.09 | −0.12 | 2.19 | |

| AIS12 (cancel work or daily activities) | c | 4 | 2.28 | 0.82 | 2.26 | |

| AIS18 (restrict usual daily activities) | f | 4 | 3.86 | −0.14 | 1.67 | |

| AIS20 (restrict recreational activities) | b | 5 | 1.98 | −0.18 | 2.06 | |

| AIS25 (need help handling routine tasks) | a | 5 | 2.15 | 0.83 | 2.97 | |

| AIS26 (interfered with leisure activities) | a | 5 | 2.35 | −0.08 | 2.18 | |

| AIS28 (productivity reduced by half or more) | a | 5 | 2.55 | −0.20 | 2.04 | |

| AIS31 (limit ability to work, study, do chores) | a | 5 | 3.12 | −0.07 | 2.29 | |

| AIS32 (make simple tasks hard to complete) | a | 5 | 2.41 | 0.07 | 2.33 | |

| AIS36 (avoid traveling) | c | 4 | 2.99 | 1.49 | 2.58 | |

| EXP_RF1 (avoid spending time outdoors) | d | 4 | 1.44 | −0.08 | 2.54 | |

| Self Conscious/Stigma (k=2) | EXP_SC2 (embarrassed by coughing) | d | 4 | 1.11 | 0.38 | 2.20 |

| EXP_STG1 (others avoid you) | a | 4 | 1.95 | 1.57 | 2.53 | |

| Sexual Functioning (k=1) | EXP_SEX1 (avoid sexual activity) | d | 4 | 1.54 | 0.93 | 2.11 |

| Sleep (k=4) | EXP_SLP1 (trouble sleeping through the night) | g | 4 | 1.23 | 0.02 | 1.63 |

| EXP_SLP2 (wake up coughing) | g | 4 | 0.94 | 0.19 | 2.18 | |

| EXP_SLP4 (wake up short of breath) | g | 4 | 1.07 | 0.40 | 2.16 | |

| EXP_SLP5 (had too little sleep) | g | 4 | 1.41 | 0.28 | 1.95 | |

| Social Functioning (k=8) | AIS3 (interfered with how you dealt with family, friends) | a | 5 | 1.93 | 0.75 | 2.54 |

| AIS7 (avoid social or family activities) | d | 5 | 2.31 | 0.89 | 3.01 | |

| AIS9 (felt like a burden on others) | a | 5 | 1.89 | 0.91 | 2.17 | |

| AIS11 (avoid being around people) | a | 5 | 2.01 | 1.45 | 2.37 | |

| AIS16 (miss family, social, or leisure activities) | c | 4 | 2.62 | 0.80 | 2.12 | |

| AIS37 (place stress on your relationships) | c | 4 | 2.81 | 1.39 | 2.40 | |

| EXP_SF1 (avoid going places) | d | 4 | 1.30 | 1.52 | 1.99 | |

| EXP_SF3 (unable to go to social activities) | d | 5 | 1.40 | 1.19 | 2.28 |

None of the time, A little of the time, Some of the time, Most of the time, All of the time

Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Very often

Never, Almost never, Sometimes, Very often, Always

Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always

Not at all, A little, Moderately, Quite a lot, Extremely

Not at all, Very little, Somewhat, Quite a lot, Could not do activities

Not at all, 1 to 3 times a month, Once a week, 2 to 3 nights a week, 4 or more nights a week

NOTE: Slope parameter - represents the discrimination of the item (degree to which it discriminates between persons at different areas on the latent continuum).

NOTE: Threshold parameter - represents the difficulty or severity of an item response (location along the continuum of item response categories).

Items with high residual correlations represent an estimation challenge, since such local dependencies may lead us to overestimate the slope parameter for these items. To estimate parameters for several item pairs showing local dependence (including experimental AIS items removed from the factor analytic model due to overlapping content), we initially estimated parameters including the first item from each pair. To estimate parameters for the remaining items, we ran the model again, this time including the second item from each pair and fixing all other items.

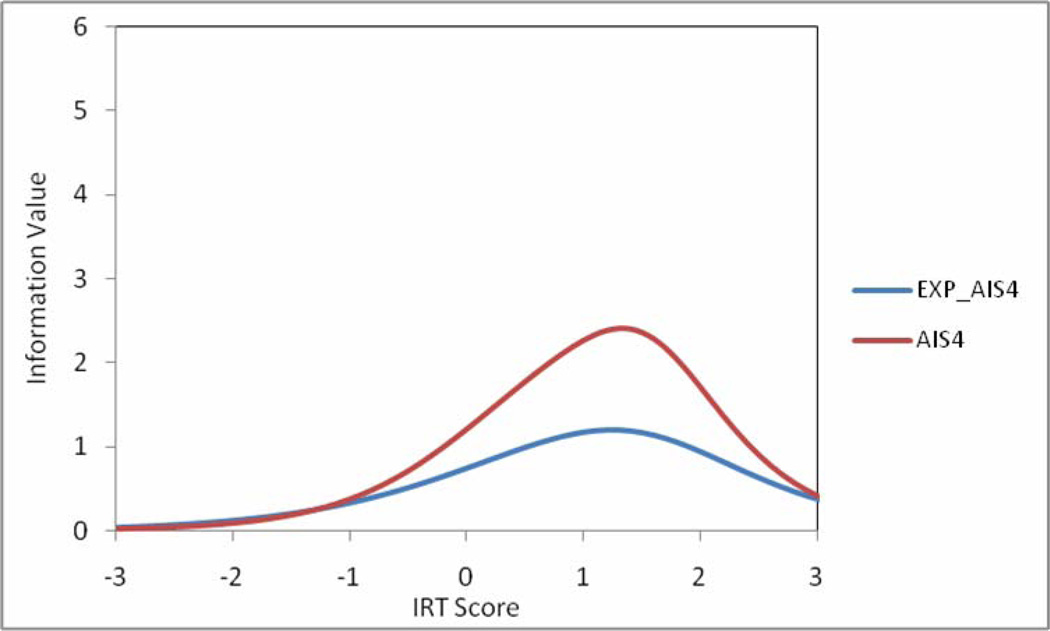

Table 3 summarizes the IRT results. Slopes and thresholds ranged from 0.94 to 3.93 and −0.80 to 3.01, respectively. For most items, tests of item fit were in the acceptable range. Information function plots for item pairs with local dependence due to similar content coverage were also examined, with the goal of eliminating one item from each pair. Items providing more information across a broader scale range were retained in the model. For example, AIS4 provided more information across the range than EXP_AIS4, so the latter was eliminated (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Information Function for AIS Item Versions with Similar Content

No DIF was found for gender, age, race, ethnicity, or educational level. One item showed DIF on symptom frequency and asthma severity, and was dropped from the model.

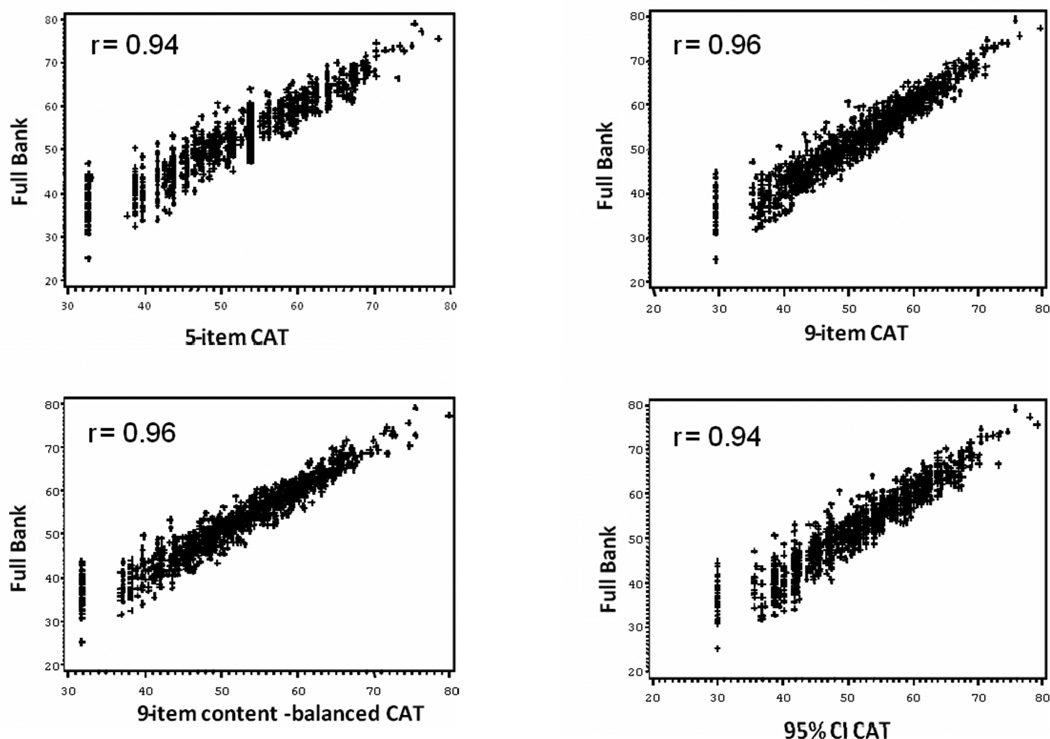

For the CAT simulations, AIS1 was selected as the initial item administered since it is a high discriminating item covering a wide range of asthma impact. Descriptive statistics for CAT score versions were highly comparable (see Table 4). Scores based on the full AIS item bank and all CAT score versions similarly covered a wide range of measurement. Figure 3 demonstrates concordance between scores on the CAT-5, CAT-9 (content balanced), CAT-9, and CAT-95% CI and those based on the full AIS item bank. For each CAT version, results show that the measures are highly correlated, though agreement is not as good at the lower end of the scale (less asthma impact).

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics for CAT Versions

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full AIS item bank | 50.92 | 10.35 | 25.20 | 79.00 |

| 5-Item CAT | 50.40 | 9.83 | 32.60 | 78.40 |

| 9-Item CAT | 50.15 | 10.20 | 29.60 | 79.50 |

| 9-Item Content-Based CAT | 50.43 | 9.83 | 31.80 | 79.90 |

| 95% Confidence Interval CAT | 50.28 | 10.11 | 29.90 | 79.10 |

Figure 3.

Correlation between Full AIS Item Bank and CAT Versions (N=1106)

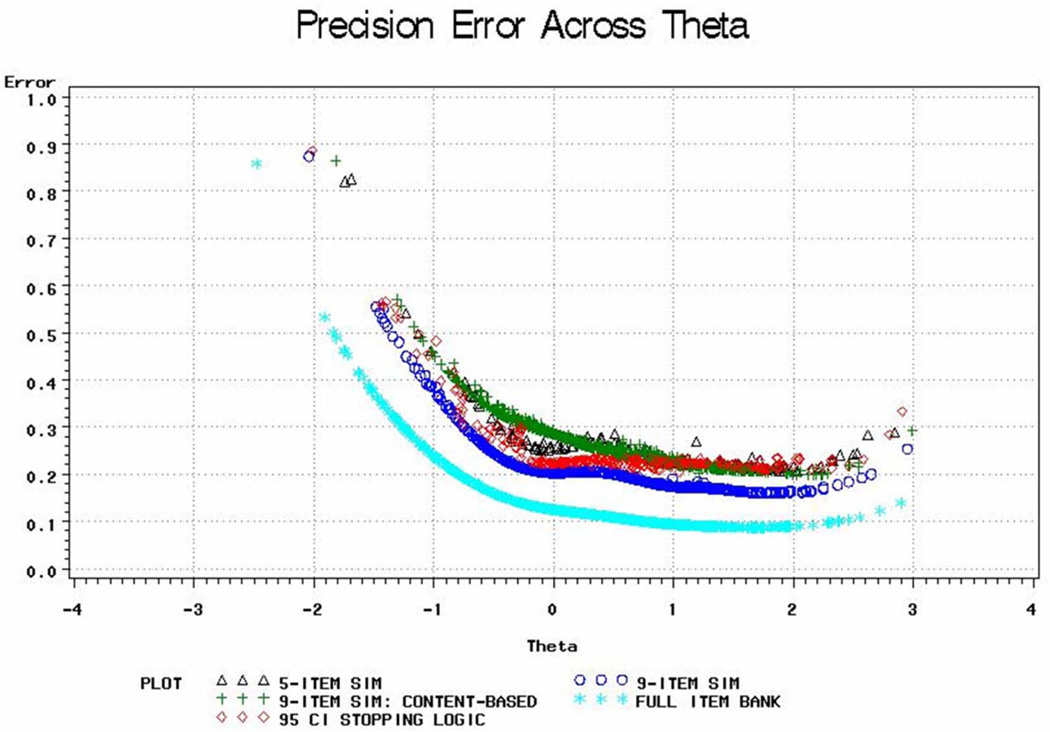

Figure 4 presents results of the real-data simulations for CAT score versions and scores based on the full AIS item bank. Score estimates are less precise in the very low range of measurement. Best performance of a scale is indicated by smaller standard error of measurement (SEM) and by the breadth of the curve with low SEMs. As shown, scores based on the full bank can be estimated with very high precision (SE < 2.3, equivalent to 95% reliability) over a wide range of the latent trait (≈ 39–79, approximately 4 SD). Using CAT-9 or CAT-95% CI still covers a wide range (3 and 2.5 SD, respectively) with very high measurement precision (SE < 2.3, 95% reliability), and a wider range (approximately 4 SD) with high measurement precision (SE < 3.3, 90% reliability). Using the 5 most informative items (CAT-5), we will cover a range of approximately 3.5 SD with measurement precision of SE < 3.3. Although CAT-9 (content balanced) is the least precise, it still performs well, covering a range of approximately 3.5 SD with high measurement precision (SE < 3.3). These simulations suggest we could cover a theta score range between 40 and 80 without increasing respondent burden, and should be able to approach a level of precision comparable to using all items.

Figure 4.

CAT Data Simulations

Note: Theta corresponds to the IRT score before rescaling to a standardized metric (mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 in the developmental sample).

Preliminary validity testing demonstrated that mean AIS scores (from the full bank and all CAT versions) differed significantly for respondents with controlled, somewhat controlled, and uncontrolled asthma (see Table 5). As expected, AIS scores were higher (greater asthma impact) for those with uncontrolled asthma and lower for those with controlled asthma.

Table 5.

Discriminant and Relative Validity Tests

| Uncontrolled (n=269) |

Somewhat Controlled (n=335) |

Controlled (n=502) |

Fa | RV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Full AIS item bank | 60.46 | 6.45 | 53.84 | 6.62 | 43.86 | 8.96 | 437.41 | 1.00 |

| CAT-5 | 59.31 | 7.41 | 52.68 | 7.37 | 44.1 | 7.84 | 372.91 | 0.85 |

| CAT-9 | 59.32 | 7.38 | 52.71 | 7.46 | 43.52 | 8.35 | 379.44 | 0.87 |

| CAT-9C | 59.58 | 6.81 | 52.92 | 7.02 | 43.86 | 7.94 | 421.81 | 0.96 |

| CAT-95% CI | 59.33 | 7.39 | 52.81 | 7.45 | 43.73 | 8.24 | 374.94 | 0.86 |

All p-values were less than .001.

The Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease score for the final AIS item bank was 76, slightly higher than the standard level (60–70); and the Grade Level score was 7.4 indicating that AIS item bank text should be understandable by an average student in the 7th grade (ages 12–13 in the United States).

DISCUSSION

We developed item calibrations for a 50-item bank to be used as the basis for a CAT of asthma impact on HRQOL. A bi-factor model fit the data and results supported unidimensionality of the bank [30, 44, 45]. For most items, response curves had a clear maximum, well separated from that of other curves. No DIF was found for gender, age, race, ethnicity, or educational level. Item fit to the model was acceptable.

Items demonstrated broad coverage across asthma impact, although there is less content coverage and precision in the lowest end of the measurement continuum (for those with little or no asthma impact). Range restrictions may produce a ceiling effect, and limit the instrument’s ability to detect positive changes in health over time in certain patient or study groups because there is limited room in the instrument for improvement. To further improve the AIS, future research can evaluate its responsiveness in various patient subgroups and, if necessary, “seed” new bank items covering content with more precision in this part of the measurement scale.

CAT simulations demonstrated several possible options for stopping rules, which can be easily modified depending on the purpose of the assessment, without compromising comparability across assessments. And, in preliminary validity tests, AIS distinguished between respondents with differing levels of asthma control.

Although efforts were made to ensure that the current panel sample was representative of asthma sufferers in the general U.S. population through quota sampling for gender and race/ethnicity, not all enrollment targets were reached. This may be due to the fact that we also sought to include participants with varied levels of asthma control in order to develop a tool that assesses functional impact across a wide measurement range. Also, this study included only non-smoking patients with self-reported asthma. Future research should cross-validate the AIS in studies with physician-diagnosed patients that include smokers and other subgroups of interest.

CONCLUSIONS

This initial CAT for asthma shows favorable psychometric characteristics, preliminary evidence of validity, and accessibility at moderate reading levels. However, since some of the bank content areas are represented by only a few items, future research may involve item bank expansion and a re-evaluation of the underlying factor structure. Computer-based PRO measures such as the AIS may play a role in the effective management of asthma. Survey results can be used by patients to track changes in health due to asthma over time, to provide an early indicator of the need for treatment intervention (e.g., based on declining scores), and to inform healthcare providers regarding the patient’s experience and perspective on their health status.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Sarah J. Hogue for her contribution to the literature review and formatting of this paper.

This research was supported in part by an NIH-sponsored grant (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, #7 R44 HL 078252-05).

Footnotes

The CI width varies for different score ranges on the measurement continuum (theta).

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Part of this research was conducted while Dr. Turner-Bowker, Dr. Saris-Baglama, and Mr. DeRosa were employed by QualityMetric Incorporated. Dr. Bjorner is employed by QualityMetric Incorporated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Busse WW. National asthma education and prevention program Expert Panel Report 3. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5S1):S94–S138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; 2007. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Revicki D, Weiss KB. Clinical assessment of asthma symptom control: review of current assessment instruments. J Asthma. 2006 Sep;43(7):481–487. doi: 10.1080/02770900600619618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wainer H, Dorans NJ, Eignor D, Flaugher R, Green B, Mislevy R, et al. Computer-adaptive testing: A primer. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item response theory for psychologists. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anatchkova MD, Saris-Baglama RN, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB. Development and preliminary testing of a computerized adaptive assessment of chronic pain. J Pain. 2009 Sep;10(9):932–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjorner JB, Chang CH, Thissen D, Reeve BB. Developing tailored instruments: item banking and computerized adaptive assessment. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(Suppl 1):95–108. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, Ware JE, Sullivan E, Straus WL. An evaluation of a patient-reported outcomes found computerized adaptive testing was efficient in assessing osteoarthritis impact. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:715–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose M, Bjorner JB, Becker J, Fries JF, Ware JE. Evaluation of a preliminary physical function item bank supported the expected advantages of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(1):17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz C, Welch G, Santiago-Kelly P, Bode R, Sun X. Computerized adaptive testing of diabetes impact: A feasibility study of Hispanics and non-Hispanics in an active clinic population. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(9):1503–1518. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware JE, Bayliss MS. The practical assessment of headache impact using item response theory and computerized adaptive testing. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:887–1012. doi: 10.1023/a:1026115230284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeatts KB, Stucky B, Thissen D, Irwin D, Varni JW, DeWitt EM, Lai JS, DeWalt DA. Construction of the Pediatric Asthma Impact Scale (PAIS) for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) J Asthma. 2010 Apr;47(3):295–302. doi: 10.3109/02770900903426997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams R, Rosier M, Campbell D, Ruffin R. Assessment of an asthma quality of life scale using item-response theory. Respirology. 2005 Nov;10(5):587–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2005.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metz SM, Wyrwich KW, Babu AN, Kroenke K, Tierney WM, Wolinsky FD. A comparison of traditional and Rasch cut points for assessing clinically important change in health-related quality of life among patients with asthma. Qual Life Res. 2006 Dec;15(10):1639–1649. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang CH, Sharp LK, Kimmel LG, Grammer LC, Kee R, Shannon JJ. A 6-item brief measure for assessing perceived control of asthma in culturally diverse patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Im. 2007 Aug;99(2):130–135. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60636-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed S, Ernst P, Tamblyn R, Colman N. Evaluating asthma control: a comparison of measures using an item response theory approach. J Asthma. 2007 Sep;44(7):547–554. doi: 10.1080/02770900701537024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner-Bowker DM, Saris-Baglama RN, Anatchkova M, Mosen D. A Computerized Asthma Outcomes Measure Is Feasible for Disease Management. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2010 Apr 1;2(2):119–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner-Bowker DM, Saris-Baglama RN, Derosa MA, Paulsen CA, Bransfield CP. Using qualitative research to inform the development of a comprehensive outcomes assessment for asthma. Patient. 2009 Dec 1;2(1):269–282. doi: 10.2165/11313840-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Pendergraft TB. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Jan;113(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayliss MS, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Fortin E. Asthma Control Test™: A user’s guide. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjorner JB, Turner-Bowker DM. Generic instruments for health status assessment: The SF-36® and S-12® Health Surveys. In: Kattan MW, Cowen M, editors. Encyclopedia of medical decision-making. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B. How to score version 2 of the SF-12® health survey (with a supplement documenting version 1) Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marks GB, Dunn SM, Woolcock AJ. A scale for the measurement of quality of life in adults with asthma. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992 May;45(5):461–472. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayliss MS, Larrat EP, Perfetto EM, Buchner D, Ware JE. ITG-Asthma short form manual and interpretation guide. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjorner JB, Kosinski M, Ware JE., Jr Calibration of an item pool for assessing the burden of headaches: an application of item response theory to the headache impact test (HIT) Qual Life Res. 2003 Dec;12(8):913–933. doi: 10.1023/a:1026163113446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muthén B. A general structural equation model with dichotomous, ordered categorical, and continuous latent variable indicators. Psychometrika. 1984;49:115–132. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Fifth ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drasgow F. Polychoric and polyserial correlations. In: Kotz S, Johnson NL, Read CB, editors. Encyclopedia of statistical sciences. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1986. pp. 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modelling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reise SP, Morizot J, Hays RD. The role of the bifactor model in resolving dimensionality issues in health outcomes measures. Qual Life Res. 2007;16 Suppl 1:19–31. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramsay JO. A program for the graphical analysis of multiple choice test and questionnaire data. Montreal: McGill University; 1995. TestGraf. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muraki E. A generalized partial credit model. In: Van der Linden WJ, Hambleton RK, editors. Handbook of modern item response theory. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muraki E, Brock RD. Parscale: IRT based test scoring and item analysis for graded open-ended exercises and performance tasks. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orlando M, Thissen D. Likelihood-based item-fit indices for dichotomous item response theory models. Appl Psych Meas. 2000;24(1):50–64. [Google Scholar]

- 35.SAS. Statistical Analysis Software for Windows [computer program]. Version 9.0. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holland PW, Wainer H. Differential item functioning. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1993. Educational Testing Service. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swaminathan H, Rogers JH. Detecting differential item functioning using logistic regression procedures. J Educ Meas. 1990;27:361–370. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagelkerke NJD. Miscellanea. A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika. 1991;78:691–692. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, Bayliss MS, Batenhorst A, Dahlof CG, Tepper S, Dowson A. Applications of computerized adaptive testing (CAT) to the assessment of headache impact. Qual Life Res. 2003 Dec;12(8):935–952. doi: 10.1023/a:1026115230284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948 Jun;32(3):221–233. doi: 10.1037/h0057532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Deviation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count, and flesch reading ease formula) for navy enlisted personnel. Millington, Tennessee: Naval Technical Training Command; 1975. Report Rbr-8-75 1975 February Research Branch. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farr JN, Jenkins JJ, Paterson DG. Simplification of flesch reading ease formula. J Appl Psychol. 1951;35(5):333–337. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cook KF, Kallen MA, Amtmann D. Having a fit: impact of number of items and distribution of data on traditional criteria for assessing IRT’s unidimensionality assumption. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(4):447–460. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9464-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDonald RP. Test theory: a unified approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum; 1999. [Google Scholar]