Abstract

Few controlled trials compared second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) regarding relapse prevention in schizophrenia. We conducted a systematic review/meta-analysis of randomized trials, lasting ≥6 months comparing SGAs with FGAs in schizophrenia. Primary outcome was study-defined relapse; secondary outcomes included relapse at 3, 6 and 12 months, treatment failure, hospitalization, and dropout due to any cause, non-adherence and intolerability. Pooled relative risk (RR) [+/−95%CIs] was calculated using random-effects model, with numbers-needed-to-treat (NNT) calculations where appropriate. Across 23 studies (n=4,504, mean duration=61.9+/−22.4 weeks), none of the individual SGAs outperformed FGAs (mainly haloperidol) regarding study-defined relapse, except for isolated, single trial-based superiority, and except for risperidone's superiority at 3 and 6 months when requiring >/=3 trials. Grouped together, however, SGAs prevented relapse more than FGAs (29.0% vs. 37.5%, RR=0.80, CI:0.70–0.91, p=.0007, I2=37%; NNT=17, CI:10–50, p=.003). SGAs were also superior regarding relapse at 3, 6 and 12 months (p=.04, p<.0001, p=.0001), treatment failure (p=.003) and hospitalization (p=.004). SGAs showed trend-level superiority for dropout due to intolerability (p=.05). Superiority of SGAs regarding relapse was modest (NNT=17), but confirmed in double-blind trials, first- and multi-episode patients, using preferentially or exclusively raw or estimated relapse rates, and for different haloperidol equivalent-comparator doses. There was no significant heterogeneity or publication bias. The relevance of the somewhat greater efficacy of SGAs over FGAs on several relevant outcomes depends on whether SGAs form a meaningful group and whether mid- or low-potency FGAs differ from haloperidol. Regardless, treatment selection needs to be individualized considering patient- and medication-related factors.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Antipsychotics, Relapse Prevention, Maintenance, Long-term treatment, Meta-analysis

Introduction

As psychopathology and social functioning can worsen with repeated relapses in schizophrenia patients (1), relapse prevention is a critical issue in managing this illness. Since clozapine, the first second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) introduced in 1971 (marketed in the US in 1990) and risperidone, introduced in 1994, a total of 8 SGAs are now available in the USA, which are widely used (2). SGAs are better tolerated than first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) regarding acute extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) (3) and tardive dyskinesia (TD) (4). However, there is growing concern about metabolic side effects, such as body weight gain, insulin resistance and dyslipidemia (5;6). Combined with the lack of significant superiority in efficacy and/or effectiveness observed in large, pragmatic trials (7–10), the advantages of non-clozapine SGAs over FGAs have been challenged. Less attention has been focused on relapse prevention. A meta-analysis comparing SGAs to FGAs was published in 2003 (11), but since then, there have been twelve additional relevant trials.

Materials and Methods

Search

We conducted a search using MEDLINE/PubMed, the Cochrane library, PsycINFO (last search date January 2011) for randomized, controlled trials of relapse prevention or maintenance treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders lasting ≥6months. Studies had to be published in English in peer-reviewed journals. Search terms included antipsychotic(s), neuroleptic(s), individual names of SGAs and FGAs, schizophrenia, random, randomly, randomized, and maintenance, relapse, or long-term. The electronic search was supplemented by hand search of reference lists of relevant studies and reviews. Authors and companies were contacted to provide missing information and unpublished data.

Inclusion Criteria

Trials included in this analysis were randomized, head-to-head comparisons of oral SGAs versus oral FGAs for relapse prevention or maintenance treatment in adults with schizophrenia. We only included trials with a minimum duration of 6 months [one study included patients with a range of 22–84 weeks completion (12)]. We also only included trials providing relapse-related information, such as study-defined relapse or re-hospitalization. Trials were included irrespective of whether randomization occurred during the acute or maintenance phase. However, when patients were randomized in the acute phase, we only used data from patients for whom information was available after they had responded, remitted or were discharged.

Data extraction and Outcomes

Data were extracted independently by ≥2 reviewers (T.Kishimoto, V.A., T.Kishi, C.C.). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

The primary outcome measure was study-defined relapse at endpoint, preferentially based on survival curves, which we believe yield more accurate data for relapse than raw relapse rates, as the bias of unequal follow-up duration is minimized. If the estimated relapse rate was not available, we used raw relapse rate. While we utilized study-defined relapse, when there was no definition of relapse or the authors' definition was regarded as inappropriate, we utilized the next most appropriate outcome for our analysis; which predominantly was re-hospitalization.

As secondary outcomes, relapse rates at 3, 6 and 12 months, “treatment failure” (defined as relapse and/or all-cause discontinuation, depending on whether data were available for both outcomes), hospitalization and dropout due to any cause, non-adherence and intolerability were examined.

Data Analysis

All outcomes were dichotomous and SGAs were compared to FGAs both individually and as separate groups for each outcome. We applied a “once-randomized-analyzed” endpoint analysis. Pooled relative risk (RR) [+/−95% confidence intervals (CIs)], and risk differences were calculated, using random-effects models by DerSimonian and Laird (13), which is more conservative than fixed effects models. Number-needed-to-treat (NNT) was calculated where appropriate. To reduce a potential type I error, we considered the meta-analytic results to be significant only if they were based on ≥3 studies.

Heterogeneity between studies was explored with a chi-square test of homogeneity (p<0.1) together with the I2-statistic, with an I2 >/=50% indicating significant heterogeneity (14).

In addition to the primary and secondary outcome analyses, we also conducted a priori defined sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome comparing SGAs with FGAs, seeking to identify potential methodological biases and whether the findings extended to clinically relevant sub-populations and treatment groups. The examined variables included: a) treatment concealment (open vs. blinded), b) sponsorship (industry vs. academia), c) publication year (before 2000 vs. 2000 and later, d) clozapine vs. non-clozapine SGAs, e) randomization time point (acute vs. maintenance phase), f) determination of patient stability (≥4 weeks vs. <4 weeks), g) first- vs. multi-episode patients, and h) haloperidol equivalent comparator dose level (<5 mg vs. ≥5 mg and <10 mg vs. ≥10 mg), calculated for non-haloperidol medications using established conversion factors (15). We also assessed the generalizability of the primary outcome results, using alternative ways to calculate relapse, i.e., utilizing preferentially raw over estimated relapse rates, and using only raw or estimated rates instead of preferring estimated relapse rate. Finally, to test if the results could be reversed in favor of FGAs, we performed a “best case scenario” analysis for FGAs. We pooled all studies where the RR for study defined relapse was >/=1.0, or >1.0 i.e., we excluded all studies where SGAs had any effect (significant or non-significant) that was larger than for FGAs.

All data were entered into a funnel graph (trial effect against trial size) to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias (16). Data were double entered (T.Kishimoto, V.A.) into Revman 5.0.25, a program developed by the Cochrane Collaboration for systematic reviews.

Results

Search and Study Characteristic

We included 18 publications of 23 randomized, active drug controlled studies with 4,504 participants (Supplemental Figure 1).

The number of participants per study ranged from 32–690 (median: 147), and mean maximum study duration was 61.9+/−22.4 (range: 40–104) weeks (Table 1). There were 6 studies with first episode and 17 with multiple episode patients. Five studies were open-label, 17 were double blind, and one study was rater-masked (17). The number of studies with each individual SGA were: amisulpride=3; aripiprazole=2; clozapine=4; iloperidone=3; olanzapine=6; quetiapine=1; risperidone=6; sertindole=1; ziprasidone=1. Haloperidol was the comparator in 21/23 studies; one study used chlorpromazine (45,46) and one used mixed FGAs (19). Mean haloperidol equivalent dose was 11.6+/−8.3 (range: 2.9–28.5) mg/day. Eighteen studies (78.3%) randomized patients in acute phase, and only 5 studies (21.7%) randomized patients in the maintenance phase. Eight studies (34.8%) determined patients' stability for ≥4 weeks, and 15 studies (65.2%) determined patients' stability <4 weeks or cross-sectionally.

Table 1.

Description of included studies

| Study/Country | Total # of Patients | Study Design | Duration (week) | Patient population included in analysis | Definition of Relapse-Related Outcome | Mean Age (year) | % Male | % White | % SzAD | # of Pts per Arm | Mean Dose (range/fixed (mg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamminga et al. '94(17)/USA | 32 | Rater Masked | 52 | OPs with TD stabilized for 1–6 months before randomization | Relapsee: study discontinuation due to decompensation | 35.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 0 | CLO: 19 | 293.8 |

| HAL: 13 | 28.5 | ||||||||||

| Essock et al. '96(19)a/USA | 124 | OL | 104 | IPs in state hospital with FDA criteria for CLO use who were discharged | Relapsee: rehospitalization | 41.2 | 60.8 | NR | NR | CLO: 76 | 496 |

| FGA: 48 | 1386g | ||||||||||

| Speller et al. '97(33)/UK | 60 | DB | 52 | IPs on rehabilitation wards with moderate to severe negative symptoms, with combined score of ≥4 on the negative subscale of Manchester Scale | Relapse: when psychotic exacerbation (increase of 3≥on the combined score for the thought disturbance and paranoia items of BPRS) could not controlled with dose increase | 63f | 76.6 | NR | 0 | AMI: 29 | NR (100–800) |

| HAL: 31 | NR (3–20) | ||||||||||

| Tran et al. '98(12)b -study 1/North America | 55 | DB | 46 | Responders to acute phase therapy (BPRS-T decreased ≥40% from baseline or ≤18.) and have been OPs | Relapse: hospitalization for psychopathology | 37.0 | 64.8 | NR | 11.5 | OLA: 5 | 12.1 (12) |

| HAL: 10 | 14.0 (14.0) | ||||||||||

| Tran et al. '98(12)b -study 2/International | 62 | DB | 46 | Responders to acute phase therapy (BPRS-T decreased ≥40% from baseline or ≤18.) and have been OPs | Relapse: hospitalization for psychopathology | 37.0 | 64.8 | NR | 11.5 | OLA: 48 | 11.5 (12) |

| HAL: 14 | 16.4 (16) | ||||||||||

| Tran et al. '98(12)b -study 3/International | 690 | DB | 22–84d | Responders to acute phase therapy (BPRS-T decreased ≥40% from baseline or ≤18.) and have been OPs | Relapse: hospitalization for psychopathology | 37.0 | 64.8 | NR | 11.5 | OLA: 534 | 13.9 (5–20) |

| HAL: 156 | 13.2 (5–20) | ||||||||||

| Daniel et al. '98(18)/USA | 203 | DB | 52 | Medication-responsive OPs stable for ≥3 months but had hospitalization or decompensation within last 5 years, CGI-S≤4 | Relapsee: hospitalization Treatment failure: 1) hospitalization; 2) 20% deterioration in BPRS-T, 3) discontinuation due to lack of efficacy or noncompliance, 4) use of other antipsychotics | 37.0 | 75.4 | 60.1 | 0 | SER: 94 | (24) |

| HAL: 109 | (10) | ||||||||||

| Rosenheck et al. '99(23)a/USA | 49 | DB | 52 | Treatment refractory patients whose PANSS-T decreased ≥20% in the initial 6 week treatment | Relapsee: failed to maintain improvement | 43.9 | 99.2 | 70.2 | 0 | CLO: 35 | 628 (100–800) |

| HAL: 14 | 28.2 (5–30) | ||||||||||

| Colonna et al. '00(42)a/France | 322 | OL | 52 | Responders after 1 month of acute phase treatment (BPRS-T decrease ≥20%) | Treatment failure: all discontinuation + cannot maintain response (BPRS-T ≥20% decrease) | 37.5 | 67.0 | 97 | 0 | AMI: 253 | 626 (200–800) |

| HAL: 69 | 15.1 (5–20) | ||||||||||

| Csernansky et al. '02(32)/USA | 361 | DB | 52 | OPs judged stable by the principal investigater; stable dose of antipsychotics and same residence for 30 days | Relapse: 1) psychiatric hospitalization; 2) psychiatric care increase and 25% increase in PANSS-T, including ≥10 points increase; 3) self-injury, suicidal, homicidal ideation, violence; 4) CGI-C≥6 | 40.2 | 69.9 | 47.7 | 17.8 | RIS: 177 | 4.9 (2–8) |

| HAL: 184 | 11.7 (5–20) | ||||||||||

| de Sena et al. '03(43)c/Brazil | 33 | OL | 52 | Hospitalized due to an acute exacerbation | Relapse: first rehospitalization after discharge | 27.7 | 18.0 | 18.9 | 0 | RIS: 20 | 4.0f (flexible) |

| HAL: 13 | 10f (flexible) | ||||||||||

| Kasper et al. '03(21)a study 1,2/USA (study 1), International (study 2) | 633 | DB | 52 | Acute phase patients who responded (≥30% reduction in PANSS-T) and not having any of 1) CGI-I≥6, 2) Adverse event of worsening schizophrenia, 3) PANSS psychotic subscale≥5 | Relapsee: fail to maintain response | 37.1 | 58.6 | NR | 0 | ARI: 444 | 29.0 (30) |

| HAL: 189 | 8.9 (10) | ||||||||||

| Lieberman et al. '03(20)c/China | 143 | DB | 40 | FEPs who discharged from 12 weeks of hospitalization for acute phase treatment | Relapsee: rehospitalization after week 12 | 28.7 | 52.0 | 0 | 0 | CLO: 71 | 600f (flexible) |

| CPZ: 72 | 400f (flexible) | ||||||||||

| Marder et al. '03(22)/USA | 63 | DB | 104 | Treated as OPs for ≥1 month but had ≥2 episodes of acute schizophrenic illness or having ≥2 years of continuing psychotic symptoms | Relapsee: psychotic exacerbation [1) ≥4points increase on the sum of BPRS cluster scores for thought disturbance and hostile-suspiciousness; 2) ≥3points increase on one of these clusters with one item ≥4 | 43.5 | 92.1 | 44.4 | 0 | RIS: 33 | 5.7 (6) |

| HAL: 30 | 4.5 (6) | ||||||||||

| Schooler et al. '05(44)a/International | 400 | DB | 104 | FEPs who achieved clinical improvement (≥20% decrease in PANSS total score) | Relapse: 1) ≥25% increase in PANSS-T, including ≥10 points increase; 2) CGI-C≥6; 3) deliberate self-injury; 4) suicidal or homicidal ideation or suicide; 5) violent behavior | 25.5 | 71.4 | 74.4 | 7.6 | RIS: 197 | 3.3 (up to 8) |

| HAL: 203 | 2.9 (up to 8) | ||||||||||

| Lieberman et al. '03(45)/Green et al. '06(46)a/USA, Europe | 133 | DB | 104 | FEPs who remitted (PANSS P1, 2, 3, 5,6≤3, CGI-S≤3 for 4-week) | Relapse: failed to maintain remission | 23.8 | 81.8 | 52.9 | 9.9 | OLA: 75 | 10.2 (5–20) |

| HAL: 58 | 4.82 (2–20) | ||||||||||

| Gaebel et al. '07(24)/Germany | 151 | DB | 52 | Successfully completed acute therapy (CGI-C≤3) in the first illness episode | Relapse: ≥10 increase of PANSS positive + CGI-C≥6 + GAF≥20 decrease; hMarked clinical deterioration: 1)single fulfillment of relapse criteria, 2) ≥7 increase in PANSS positive + ≥15 decrease in GAF | 31.6 | 58.3 | NR | 0 | RIS: 77 | 4.2 (2–4) |

| HAL: 74 | 4.1 (2–4) | ||||||||||

| Kane et al. '08(34) study 1 – 3 pooled/International | 473 | DB | 46 | Completed initial 6 wks with ≥20% decrease of PANSS-total score and CGI-C≤4 | Relapse: 1) ≥25% increase in PANSS-T, including ≥10 points increase; 2) discontinuation due to lack of efficacy; 3) aggravated psychosis with hospitalization; 4) ≥2 increase in CGI-S | 34.7 | 63.4 | 45.6 | 6.3 | ILO: 359 | 11.8 (4–16) |

| HAL: 114 | 13.2 (5–20) | ||||||||||

| Kahn et al. '08(10)/Europe and Israel | 351 | OL | 52 | FEPs within 2 years since the onset of positive symptoms and had ≤14days of antipsychotic exposure | Relapsee: admitted to hospital after randomization | 26.0 | 60.0 | 94.0 | 7.0 | AMI: 88 | 450.8 (200–800) |

| OLA: 89 | 12.6 (5–20) | ||||||||||

| QUE: 60 | 498.6 (250–700) | ||||||||||

| ZIP: 60 | 107.2 (40–160) | ||||||||||

| HAL: 64 | 3.0 (1–4) | ||||||||||

| Crespo-Facorro etal. '10(47)/Spain | 166 | OL | 52 | FEPs who have improved by study medication to CGI-S≤4, 30%≥ decrease of BPRS-T, all BPRS item≤3 for ≥4 weeks | Relapse: 1) any key BPRS item≥5, 2) CGI-S≥6, CGI-G≥6, 3) psychotic hospitalization, 4) complete suicide | 27.4 | 62.0 | NR | 2.4 | OLA: 54 | 10.4 (5–20) |

| RIS: 58 | 3.4 (3–6) | ||||||||||

| HAL: 54 | 2.9 (3–9) |

Subpopulation of responded or remitted patients used in this meta-analysis, but demographic data was obtained from study original total population

Demographic data was obtained from study 1,2,3 pooled data.

100% of patients discharged after randomization.

Subjects completed between 22 and 84 weeks of double blind therapy.

Original study didn't have relapse definition, mentioned outcome utilized as relapse in the analysis

Reported median

Chlorpromazine equivalent dose

Utilized marked clinical deterioration as relapse in analysis

Abbreviations: AMI=amisulpride, ARI=aripiprazole, BPRS=Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, BPRS-T=BPRS total score, CGI-C=Clinical Global Impressions scale-change score, CGI-S=Clinical Global Impressions scale-severity score, CLO=clozapine, CPZ=chlorpromazine, DB =double blind, FEPs=first-episode patients, FGA=frrst-generation antipsychotics, GAF=Global Assessment of Functioning scale, HAL=haloperidol, ILO=iloperidone, IPs=inpatients, NR=not reported, OL=open label, OLA=olanzapine, OPs=outpatients, PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, PANSS-T=PANSS total score QUE=quetiapine, RIS=risperidone, SER=sertindole, SzAD=schizoaffective disorder, ZIP=ziprasidone

Relapse definitions varied. In 9 studies, relapse was not defined. In 4 of these (10;18–20), we used hospitalization rate. In the remaining 5, we utilized “failure to maintain response” (21), “psychotic exacerbation” (22), “failed to maintain improvement” (23), “dropout due to decompensation” (17). In another study, very strict, pre-defined relapse criteria resulted in no relapse in either group (24). Therefore, the authors employed “marked clinical deterioration” post-hoc, which we also utilized.

Endpoint relapse rate

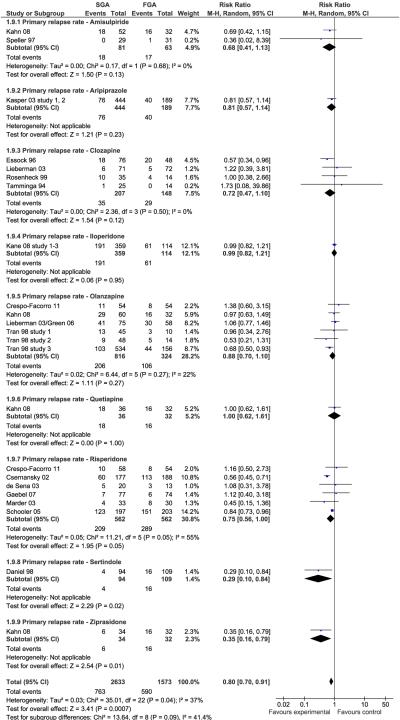

Two single studies of SGAs yielded significant superiority over FGA. These included sertindole (n=203, RR=0.29, CI:0.10–0.84, p=0.02) and ziprasidone (n=66, RR=0.35, CI:0.16–0.79, p=0.01). When requiring ≥3 trials per individual antipsychotic, neither risperidone (n=1124, RR=0.75, CI:0.56–1.00, p=0.05, I2=55%), clozapine (n=355, RR=0.72, CI:0.47–1.10, p=0.12 I2=0%) or olanzapine (n=1140, RR=0.88, CI:0.70–1.10, p=0.27, I2=22%) were statistically superior to FGAs in preventing relapse (Figure 1). However, when grouped together, SGAs were significantly superior to FGAs without significant heterogeneity (N=19, n=4206, 29.0% vs. 37.5%, RR=0.80, CI:0.70–0.91, p=.0007, I2=37%; NNT=17, CI:10–50, p=0.003) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Primary Outcome: Study-defined Relapse

Figure 2.

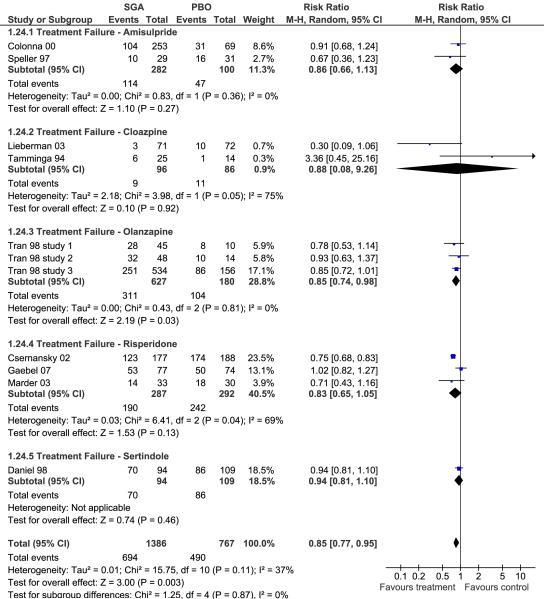

Overall Treatment Failure

Relapse rate at 3, 6 and 12 months

Several individual SGAs were associated with significantly lower relapse rates at specific time points. This included clozapine at 3 months (p=0.03), 6 months (p=0.006), olanzapine at 6 months (p=0.0003) and sertindole (p=0.02) as well as ziprasidone (p=0.01) at 12 months. Requiring ≥3 analyzable trials, only risperidone showed significant superiority over FGAs at both 6-months (p=0.004) and 12-months (p<0.0001) (Supplemental Figures 2–4). Pooled SGAs, however, were superior to FGAs at all pre-specified time points, i.e., 3-months: 13.8% vs. 17.4%, p=.04; 6-months: 21.0% vs. 28.1%, p<.0001; 12-months: 31.4% vs. 37.1%, p=.0001).

Treatment failure, hospitalization and dropout due to any cause, non-adherence and intolerability

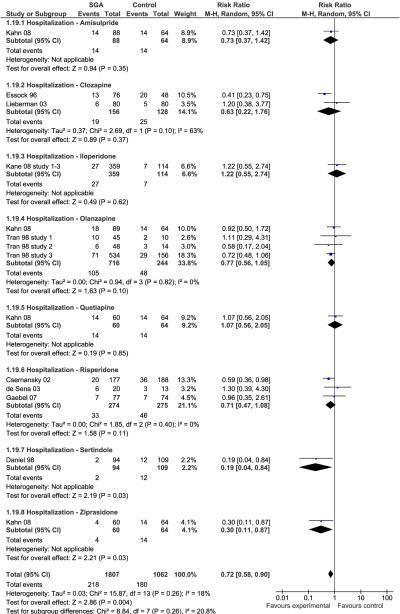

Individually, only olanzapine was superior to FGAs (p=.03) regarding treatment failure defined as relapse and/or all-cause discontinuation, but pooled together, SGAs significantly outperformed FGAs (p=.003) (Figure 2). Except for single study superiority of sertindole and ziprasidone (p=0.03 each), none of the individual SGAs was superior to FGAs in preventing hospitalization (Figure 3). However, pooled together, SGAs were superior to FGAs (12.1% vs. 16.9%, p=.004).

Figure 3.

Hospitalization

Dropout rates for reasons other than relapse varied widely from 9.1%–68.2% (median: 34%,13 studies with data). Except for single study-based lower dropout for non-adherence with sertindole (p=0.02), no significant superiority was found for any individual SGA for dropout due to any reason, non-adherence or intolerability. Even when pooled together, SGAs had only trend-level superiority over FGAs regarding dropout due to any cause (p=.06) (Supplemental Figure 5), non-adherence (fewer data points were available, p=.20) (Supplemental Figure 6) and intolerability (p=.05) (Supplemental Figure 7).

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses (Table 2)

Table 2.

Sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses

| Variables | Relative Risk | Risk Difference | NNT | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| N | n | RR | 95% CI | I2% | P | RD | 95% CI | NNT | 95% CI | I2% | P | |

| Blinding status | ||||||||||||

| Open label studies | 4 | 537 | 0.78 | 0.57, 1.06 | 9 | .11 | 0.06 | 0.06, 0.18 | NA | NA | 43 | .34 |

| Blinded studies | 18 | 3519 | 0.79 | 0.68, 0.92 | 44 | .003 | 0.06 | 0.02, 0.10 | 16.7 | 10, 50 | 58 | .009 |

| Sponsorship | ||||||||||||

| Pharmaceutical study | 15 | 3250 | 0.81 | 0.75, 0.89 | 52 | <.00001 | 0.07 | 0.04, 0.10 | 14.3 | 10, 25 | 57 | <.00001 |

| Academic study | 6 | 767 | 0.77 | 0.60, 1.00 | 0 | .05 | 0.03 | −0.03, 0.09 | NA | NA | 30 | .29 |

| Publication year | ||||||||||||

| before 2000 | 8 | 1282 | 0.65 | 0.51, 0.82 | 0 | .0002 | 0.07 | 0.02, 0.12 | 14.3 | 8.3, 50 | 13 | .003 |

| after 2000 | 14 | 2774 | 0.84 | 0.72, 0.98 | 48 | .03 | 0.05 | −0.01, 0.11 | NA | NA | 67 | .09 |

| Clozapine/non-clozapine | ||||||||||||

| Clozapine studies | 4 | 355 | 0.72 | 0.47, 1.10 | 0 | .12 | 0.02 | −0.09, 0.13 | NA | NA | 55 | .68 |

| Non-clozapine SGAs studies | 18 | 3701 | 0.80 | 0.69, 0.92 | 45 | .002 | 0.07 | 0.02, 0.11 | 14.3 | 9.1, 50 | 53 | .002 |

| Randomization time point | ||||||||||||

| During acute phase | 17 | 3326 | 0.86 | 0.79, 0.94 | 0 | .001 | 0.04 | 0.01, 0.07 | 25 | 14.3, 100 | 13 | .02 |

| During maintenance phase | 5 | 730 | 0.54 | 0.43, 0.68 | 0 | <.00001 | 0.10 | −0.02, 0.22 | NA | NA | 85 | .12 |

| Patient stability determination | ||||||||||||

| Cross sectional stabilization | 14 | 2454 | 0.84 | 0.77, 0.93 | 0 | .0006 | 0.05 | 0.01, 0.09 | 20 | 11.1, 100 | 15 | .01 |

| Stabilized ≥4 weeks | 8 | 1602 | 0.74 | 0.53, 1.03 | 63 | .08 | 0.07 | −0.02, 0.15 | NA | NA | 76 | .12 |

| First/multi episode | ||||||||||||

| First episode | 6 | 1207 | 0.87 | 0.78, 0.98 | 0 | .02 | 0.02 | −0.04, 0.08 | NA | NA | 43 | 0.52 |

| Multi episode | 16 | 2849 | 0.71 | 0.58, 0.87 | 44 | .0009 | 0.08 | −0.03, 0.13 | 12.5 | 7.7, 33 | 53 | .002 |

| Haloperidol comparator dose | ||||||||||||

| <5mg/day | 7 | 1187 | 0.86 | 0.77, 0.97 | 0 | .01 | 0.04 | −0.02, 0.09 | NA | NA | 32 | .16 |

| ≥5mg/day | 15 | 2869 | 0.73 | 0.59, 0.90 | 47 | .003 | 0.07 | 0.01, 0.13 | 14.3 | 7.7, 100 | 61 | .01 |

| <10mg/day | 10 | 1963 | 0.86 | 0.77, 0.96 | 0 | .007 | 0.03 | −0.01, 0.07 | NA | NA | 21 | .12 |

| ≥10mg/day | 12 | 2093 | 0.70 | 0.54, 0.90 | 55 | .006 | 0.09 | 0.16, 0.02 | 11.1 | 6.3, 50 | 58 | .01 |

| Relapse rate calculation | ||||||||||||

| Using preferentially raw over estimated rates | 22 | 4449 | 0.81 | 0.71, 0.94 | 25 | .005 | 0.04 | 0.01, 0.07 | 25 | 14.3, 100 | 33 | .004 |

| Using only estimated rates | 16 | 3631 | 0.76 | 0.66, 0.88 | 48 | .0003 | 0.09 | 0.04, 0.14 | 11.1 | 7.1, 25 | 50 | .0002 |

| Using only raw rates | 20 | 3753 | 0.82 | 0.70, 0.96 | 29 | .02 | 0.04 | 0.01, 0.07 | 25 | 14.3, 100 | 37 | .01 |

p-values <.05 bolded to indicate statistical significance

The superiority of grouped SGAs regarding preventing relapse remained significant in blinded studies (N=18, n=3519, p=.003), pharmaceutical company-sponsored studies (N=15, n=3250, p<.00001), studies published before and after 2000 (N=8, n=1282, p=.0002; N=14, n=2774, p=.03, respectively), non-clozapine SGA studies (N=18, n=3701, p=.002), both randomization time points (acute phase: N=17, n=3326, p=.001; maintenance phase: N=5, n=730, p<.00001), studies with < 4 weeks or cross-sectionally assessed stability (N=14, n=2454, p=.0006), and in first- and multi-episode patients (N=6, n=1207, p=.02; N=16, n=2849, p=.0009, respectively). Results remained significant regardless of the haloperidol comparator dose. Academia-sponsored studies (N=6, n=767, p=.05); and studies requiring validated patient stability for ≥4 weeks showed trend-level superiority of SGAs (N=8, n=1602, p=.08). SGAs remained significantly superior over FGAs independent of whether raw relapse rates were used preferentially over estimated relapse rates (p=.005), and whether only estimated rates or raw rates were used (p=.0003; p=.02, respectively). Finally, performing a “best case scenario” analysis for FGAs, we pooled all studies where the RR for study defined relapse was >/=1.0. In this subsample, SGAs were not inferior to FGAs (N=9, n=836, RR=1.08 (CI:0.97–1.35), p=0.50, I squared=0%). The same was true when removing the two studies with an RR=1.0, i.e., when analyzing only studies that had an RR >1.0 that disfavored SGAs (N=7, n=719, RR=1.11 (CI:0.96–1.44, p=0.46, I squared=0%).

Other outcomes

Changes in psychopathology and side effects could not be formally meta-analyzed, as most studies did not provide these data separately for the stabilized subgroup in which relapse was examined.

Publication bias

The symmetrical funnel-plot did not suggest overt publication bias (Supplemental Figure 8).

Discussion

This is the largest meta-analysis to date directly comparing relapse rates in schizophrenia patients treated with SGAs or FGAs followed for ≥6 months. We found that while in some single-studies individual SGAs were associated with significantly lower relapse rates and isolated other superiority regarding secondary outcomes, this was no longer the case when requiring at least three studies providing data for the meta-analysis of individual drug effects. The exception was risperidone, which showed significant superiority over FGAs at both 6-months (p=0.004) and 12-months (p<0.0001) when requiring ≥3 analyzable trials.

Of note, however, there was no instance where individual FGAs were superior to individual SGAs, either at a trial level or compared to all trials with a specific SGA. Moreover, when grouped together, SGAs as a group were superior to FGAs. Although the NNT of 17 is modest, the results were bolstered in that they were confirmed in a number of relevant sensitivity and subgroup analyses and also extended to overall treatment failure and hospitalization, the latter of which is known to be less sensitive than relapse (25). Therefore, we consider these findings are relevant when choosing long-term treatments in clinical practice. Although SGAs were not significantly superior to FGAs regarding all-cause discontinuation, discontinuation for intolerability or non-adherence, results trended in favor of SGAs (p=0.05–0.20), and the analyzable samples for these outcomes included only 18%–50% of all patients. However, these results need to be considered in the context of the cost-effectiveness discussion regarding SGAs vs. FGAs (9;26–28).

Our report included 23 studies, involving 4,504 participants. This extends the similar findings from the earlier meta-analysis (11) that included 11 studies with 2032 patients. The inclusion criteria and methodology were similar, except that we preferred survival curve-estimated relapse rates over raw rates as our primary outcome, which we believe is a better measure, since the shorter follow-up durations often found with FGAs can bias the results against SGAs, which often have more follow-up and observation time during which relapse can occur. Actually, in both the prior and current meta-analyses, differences were smaller when raw relapse rates were used, but the results were not affected by the methods used to calculate relapse. Furthermore, compared to the prior meta-analysis (11), we were able to include 4 additional SGAs in our analyses, i.e., aripiprazole, iloperidone, quetiapine and ziprasidone, we included 6 first episode studies, and we were able to extend the analyses by investigating multiple secondary outcomes and conducting previously unavailable sensitivity analyses that confirmed and extended the primary results. This included superiority of SGAs compared to FGAs dosed below 5 mg/day (haloperidol equivalents), whereas the comparatively high haloperidol doses used in the earlier studies had been a major shortcoming in the previously available data base.

Nevertheless, relapse rates were substantially different between prior and current analyses, even when taking into the account that we preferentially used survival analyses-based rates. In the prior analysis (11), relapse rates at 1 year were 15% vs. 23% for SGAs and FGAs compared to 31.4% vs. 37.1% in our analysis. It appears that the low threshold definition of relapse in some more recent, large trials accounts for this difference, but SGAs demonstrated superiority regardless of whether study defined relapse, treatment failure or hospitalization was used.

There has been much recent debate about the relative merits of SGAs over FGAs (8–10;27–31). Increasingly, the heterogeneity of SGAs and FGAs with need for individualization of treatment is being stressed (8;25–30). Nevertheless, different drug classes are usually determined by distinctly different mechanisms, and SGAs and FGAs differ regarding potentially relevant receptor binding profiles. Moreover, the grouping has some historical relevance because of previous reviews and clinical trials of efficacy, effectiveness, relapse, EPS and TD. Although we think the strict dichotomy has outlived its usefulness, we now have a larger series of studies comparing SGAs to haloperidol (once the leading drug worldwide), suggesting that there are modest differences regarding relapse prevention, a prevailing long-term goal in schizophrenia, regardless of high, medium or low haloperidol comparator dose and, possibly, dropout due to intolerability and non-adherence. The fact that we found relatively consistent differences favoring SGAs, though modest, also has heuristic implications in that some patients relapse despite adequate dopamine antagonism provided by FGAs and SGAs. Therefore, an understanding of what other mechanisms might be relevant for relapse (even in a subset of patients) is important.

However, results of this study have to be interpreted in the context of several limitations. The data base, though larger than in the previous meta-analysis, is still limited, especially regarding individual SGAs as well as FGA comparators other than haloperidol. This limitation does not allow for a conclusive comparison of individual SGAs, which needs to be addressed by the conduct of additional studies. Another important limitation is the inconsistent definition of relapse. As noted, we utilized each study-defined relapse measure, and if no definition of relapse was available, or if the study-defined relapse criteria were considered inappropriate, we used what we judged to be the most appropriate relapse-related outcome, i.e., predominantly psychiatric hospitalization. The problem of heterogeneously defined relapse is not surprising, since there is no universally accepted definition. On the other hand, this heterogeneity and broad-based definition of the primary outcome could also serve to enhance the generalizability of the results.

A further limitation is the methodological variability of the studies. For example, in many trials randomization occurred in the acute phase. To deal with this problem, we only used the subpopulation of patients who were judged to be responders or who were stable enough to be discharged, so that this subpopulation could be considered “at risk” for relapse, having demonstrated clear improvement as well as subsequent, clear exacerbation from that new baseline state. The concern is that by including studies, which randomized acutely exacerbated patients, we would include only patients at risk for relapse who had responded to that specific medication for acute treatment. This could lead to a selection bias toward patients who experienced less side effects or experienced more improvement on the allocated medication. If we were limited to the studies randomizing patients in the maintenance phase, only five studies would have been eligible for this meta-analysis. Furthermore, we also wanted to utilize the same inclusion criteria as in the previous meta-analysis (11). Moreover, this apparent bias applied to both SGAs and FGAs and mirrors clinical practice, in that maintenance treatment is utilized in patients who tolerate a given treatment and who do reasonably well on it.

Another limitation is the paucity of available data on potentially relevant factors, such as EPS and adherence, as well as the use of the high-potency FGA haloperidol in 21/23 studies, which precluded subgroup analyses for mid- or low-potency FGAs. The possibility that higher EPS rates could contribute to the higher rate of relapse, either directly or indirectly via non-adherence, should be considered. For example, the possibility exists that akathisia or severe akinesia might have mimicked or contributed to apparent psychotic exacerbation. However, it is unlikely that in a maintenance study involving relatively stable patients, there would be a sufficiently sudden or dramatic increase in EPS to trigger a clinical or rating scale threshold of relapse. This is of particular importance because haloperidol was a comparator in most studies and therefore might have facilitated an apparent advantage for SGAs due to its higher EPS risk. However, SGAs were superior regardless of the haloperidol comparator dose. There were insufficient data to carry out a meta-analysis on EPS or adherence, but in the studies with data (17;18;24;32–34), SGAs showed either significant or trend level superiority in some of the EPS-related outcomes. Some studies provided non-adherence rates and some provided data on discontinuation for non-adherence, but these measures were generally crude. Nevertheless, we did not find significantly more non-adherence with FGAs in the 9 studies with relevant data. In addition, other studies have not consistently shown that adherence with SGAs is sufficiently superior to explain the differences in relapse rates observed in our meta-analysis (35;36).

Assuming that we have identified a true difference between SGAs and FGAs for relapse prevention, unconfounded with differences in adherence or EPS, possible explanations for this finding deserve consideration. Differences in receptor biding profiles might play some role in relapse prevention. Clearly dopamine receptor antagonism alone is insufficient to prevent all relapses as evidenced by the roughly 20% of patients who relapse within a year on long-acting injectable antipsychotics (37). It is possible that SGAs are associated with less DA receptor upregulation [as evidenced by lower rates of tardive dyskinesia (4)] and that this might also impact rates of psychotic relapse. At the same time, SGAs have outperformed FGAs on measures of subjective well being and quality of life, raising the possibility that these might also be mediating factors in relapse risk (38). However, a detailed discussion of these possibilities is beyond scope this report.

Finally, we acknowledge that other long-term costs of FGA and SGA treatment, such as the risk for tardive dyskinesia (4;39) and for cardiovascular adverse effects (3;6;40) require careful consideration in the individualized choice of treatments for schizophrenia patients.

Thus, while the results might appear somewhat confusing in that only several individual SGAs separated from the FGA comparator, whereas in pooled analyses SGAs were clearly superior to FGAs, we believe that our results indicate that this disconnect is likely due to a lack of power. This interpretation of the results is based on the following: First, despite inclusion of heterogeneous SGAs and study populations, there is no evidence that FGAs are superior to SGAs. Even when we restricted the analyses removing all individual studies that showed results in the direction of favoring SGAs (i.e., best case scenario for FGAs in that all RRs were >/=1.0 or >1.0), the p-value for the comparison of these 9 and 7 studies was 0.50 and 0.43, respectively. Second, the superiority of combined SGAs vs. FGAs was widespread, generalizing to almost all examined efficacy outcomes.

In conclusion, results from this meta-analysis suggest that, while individually SGAs were not consistently superior to FGAs, as a group, SGAs were associated with less study-defined relapse, overall treatment failure and hospitalization than FGAs, having a modest but clinically relevant effect size. Future relapse prevention studies should carefully assess EPS and adherence. Moreover, additional studies with a variety of SGAs using non-haloperidol FGA comparators at low-medium doses that do not produce significantly greater EPS than SGAs (41) are needed to extend these findings. In particular, sufficiently large data sets are needed to allow the examination of the relative merits of individual SGAs and to guide an individualized and evidence-based maintenance treatment selection in schizophrenia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by The Zucker Hillside Hospital Advanced Center for Intervention and Services Research for the Study of Schizophrenia (MH090590) from the National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Md. The sponsor had no influence on the design, data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

We thank Gennady Gelman, MD, and Allyssa Brody, BS for help with the literature search and data abstraction. We thank the following authors and pharmaceutical companies for providing additional, unpublished data on their studies relevant for this meta-analysis: Drs. Benedicto Crespo-Facorro, Eduardo Pondé de Sena, Jeffrey A Lieberman, Robert Hamer, Eli Lilly (Drs. Bruce Kinon and Virginia Stauffer), Janssen-Cilag Brazil (Dr. de Sena), and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation (Dr. Marla Hochfeld).

Footnotes

Part of the data were presented in poster format at the 51st Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation (NCDEU), Boca Raton, FL, June 15, 2011

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Kishimoto has received speaker's honoraria from Banyu, Eli Lilly, Dainippon Sumitomo, Janssen, Otsuka, Pfizer. He has received grant support from the Byoutaitaisyakenkyukai Fellowship (Fellowship of Astellas Foundation of Research on Metabolic Disorders) and Eli Lilly Fellowship for Clinical Psychopharmacology.

Dr. Agarwal has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Kishi has received speaker's honoraria from Astellas, Dainippon Sumitomo, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Otsuka, and Pfizer and has received grant support from the Fellowship of Japan Research Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology.

Dr. Leucht received speaker/consultancy/advisory board honoraria from SanofiAventis, BMS, EliLilly, Essex Pharma, AstraZeneca, Alkermes, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen/Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck, Medavante and Pfizer, SanofiAventis and EliLilly supported research projects by SL.

Dr. Kane has been a consultant to Astra-Zeneca, Janssen, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo/Sepracor/Sunovion, Johnson & Johnson, Otsuka, Vanda, Proteus, Takeda, Targacept, IntraCellular Therapies, Merck, Lundbeck, Novartis, Roche, Rules Based Medicine, Sunovion and has received honoraria for lectures from Otsuka, Eli Lilly, Esai, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Janssen. He has received grant support from The National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Correll has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from: Actelion, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, GSK, IntraCellular Therapies, Ortho-McNeill/Janssen/J&J, Merck, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Sunovion. He has received grant support from the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and the National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), BMS, Ortsuka and Ortho-McNeill/Janssen/J&J.

References

- 1.Lieberman JA. Atypical antipsychotic drugs as a first-line treatment of schizophrenia: a rationale and hypothesis. J Clin.Psychiatry. 1996;57(Suppl 11):68–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, Moloney RM, Stafford RS. Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995–2008. Pharmacoepidemiol.Drug Saf. 2011;20(2):177–84. doi: 10.1002/pds.2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, Hunger H, Schmid F, Lobos CA, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2010;123(2–3):225–33. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am. J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):414–25. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. J Clin. Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):267–72. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, Napolitano B, Kane JM, Malhotra AK. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;302(16):1765–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenheck R, Perlick D, Bingham S, Liu-Mares W, Collins J, Warren S, et al. Effectiveness and cost of olanzapine and haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(20):2693–702. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.20.2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, Mcevoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N. Engl. J Med. 2005;353(12):1209–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones PB, Barnes TR, Davies L, Dunn G, Lloyd H, Hayhurst KP, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect on Quality of Life of second- vs first-generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63(10):1079–87. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, Davidson M, Vergouwe Y, Keet IP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leucht S, Barnes TR, Kissling W, Engel RR, Correll C, Kane JM. Relapse prevention in schizophrenia with new-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Am. J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1209–22. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran PV, Dellva MA, Tollefson GD, Wentley AL, Beasley CM., Jr. Oral olanzapine versus oral haloperidol in the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia and related psychoses. Br. J Psychiatry. 1998;172:499–505. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.6.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, McGlashan TH, Miller AL, Perkins DO, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am. J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2 Suppl):1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamminga CA, Thaker GK, Moran M, Kakigi T, Gao XM. Clozapine in tardive dyskinesia: observations from human and animal model studies. J Clin. Psychiatry. 1994;55(Suppl B):102–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniel DG, Wozniak P, Mack RJ, McCarthy BG. Long-term efficacy and safety comparison of sertindole and haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia. The Sertindole Study Group. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1998;34(1):61–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Essock SM, Hargreaves WA, Covell NH, Goethe J. Clozapine's effectiveness for patients in state hospitals: results from a randomized trial. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1996;32(4):683–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H, Stroup S, Zhang P, Kong L, et al. Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naive first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine vs chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(5):995–1003. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasper S, Lerman MN, McQuade RD, Saha A, Carson WH, Ali M, et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole vs. haloperidol for long-term maintenance treatment following acute relapse of schizophrenia. Int. J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6(4):325–37. doi: 10.1017/S1461145703003651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marder SR, Glynn SM, Wirshing WC, Wirshing DA, Ross D, Widmark C, et al. Maintenance treatment of schizophrenia with risperidone or haloperidol: 2-year outcomes. Am. J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1405–12. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenheck R, Evans D, Herz L, Cramer J, Xu W, Thomas J, et al. How long to wait for a response to clozapine: a comparison of time course of response to clozapine and conventional antipsychotic medication in refractory schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1999;25(4):709–19. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaebel W, Riesbeck M, Wolwer W, Klimke A, Eickhoff M, von Wilmsdorff M, et al. Maintenance treatment with risperidone or low-dose haloperidol in first-episode schizophrenia: 1-year results of a randomized controlled trial within the German Research Network on Schizophrenia. J Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1763–74. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gitlin M, Nuechterlein K, Subotnik KL, Ventura J, Mintz J, Fogelson DL, et al. Clinical outcome following neuroleptic discontinuation in patients with remitted recent-onset schizophrenia. Am. J Psychiatry. 2001;158(11):1835–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenheck RA, Leslie DL, Sindelar J, Miller EA, Lin H, Stroup TS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics and perphenazine in a randomized trial of treatment for chronic schizophrenia. Am. J Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2080–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenheck RA, Leslie DL, Doshi JA. Second-generation antipsychotics: cost-effectiveness, policy options, and political decision making. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008;59(5):515–20. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.5.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenheck RA. Pharmacotherapy of first-episode schizophrenia. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1048–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kane JM, Correll CU. Past and present progress in the pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin. Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1115–24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10r06264yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leucht S, Heres S, Kissling W, Davis JM. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Int. J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(2):269–84. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710001380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R. A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. N. Engl. J Med. 2002;346(1):16–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speller JC, Barnes TR, Curson DA, Pantelis C, Alberts JL. One-year, low-dose neuroleptic study of in-patients with chronic schizophrenia characterised by persistent negative symptoms. Amisulpride v. haloperidol. Br. J Psychiatry. 1997;171:564–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kane JM, Lauriello J, Laska E, Di Marino M, Wolfgang CD. Long-term efficacy and safety of iloperidone: results from 3 clinical trials for the treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(2 Suppl 1):S29–S35. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318169cca7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Jeste DV. Antipsychotic medication adherence: is there a difference between typical and atypical agents? Am. J Psychiatry. 2002;159(1):103–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, Scott J, Carpenter D, Ross R, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin. Psychiatry. 2009;70(Suppl 4):1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leucht C, Heres S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Davis JM, Leucht S. Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia-A critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophr. Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambert M, Schimmelmann BG, Schacht A, Suarez D, Haro JM, Novick D, et al. Differential 3-Year Effects of First- Versus Second-Generation Antipsychotics on Subjective Well-Being in Schizophrenia Using Marginal Structural Models. J Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):226–30. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182114d21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenheck RA. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of reduced tardive dyskinesia with second-generation antipsychotics. Br. J Psychiatry. 2007;191:238–45. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.035063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nielsen J, Skadhede S, Correll CU. Antipsychotics associated with the development of type 2 diabetes in antipsychotic-naive schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(9):1997–2004. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leucht S, Wahlbeck K, Hamann J, Kissling W. New generation antipsychotics versus low-potency conventional antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9369):1581–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Colonna L, Saleem P, Dondey-Nouvel L, Rein W. Long-term safety and efficacy of amisulpride in subchronic or chronic schizophrenia. Amisulpride Study Group. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2000;15(1):13–22. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200015010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Sena EP, Santos-Jesus R, Miranda-Scippa A, Quarantini LC, Oliveira IR. Relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a comparison between risperidone and haloperidol. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2003;25(4):220–3. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462003000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schooler N, Rabinowitz J, Davidson M, Emsley R, Harvey PD, Kopala L, et al. Risperidone and haloperidol in first-episode psychosis: a long-term randomized trial. Am. J Psychiatry. 2005;162(5):947–53. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lieberman JA, Tollefson G, Tohen M, Green AI, Gur RE, Kahn R, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus haloperidol. Am. J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1396–404. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green AI, Lieberman JA, Hamer RM, Glick ID, Gur RE, Kahn RS, et al. Olanzapine and haloperidol in first episode psychosis: two-year data. Schizophr. Res. 2006;86(1–3):234–43. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crespo-Facorro B, Perez-Iglesias R, Mata I, Caseiro O, Martinez-Garcia O, Pardo G, et al. Relapse prevention and remission attainment in first-episode non-affective psychosis. A randomized, controlled 1-year follow-up comparison of haloperidol, risperidone and olanzapine. J Psychiatr. Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.