Summary

Cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) is a common, bacterial second messenger that regulates diverse cellular processes in bacteria. Opposing activities of diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and phosphodiesterases (PDEs) control c-di-GMP homeostasis in the cell. Many microbes have a large number of genes encoding DGCs and PDEs that are predicted to be part of c-di-GMP signaling networks. Other building blocks of these networks are c-di-GMP receptors which sense the cellular levels of the dinucleotide. C-di-GMP receptors form a more diverse family, including various transcription factors, PilZ domains, degenerate DGCs or PDEs, and riboswitches. Recent studies revealing the molecular basis of c-di-GMP signaling mechanisms enhanced our understanding of how this molecule controls downstream biological processes and how c-di-GMP signaling specificity is achieved.

Introduction

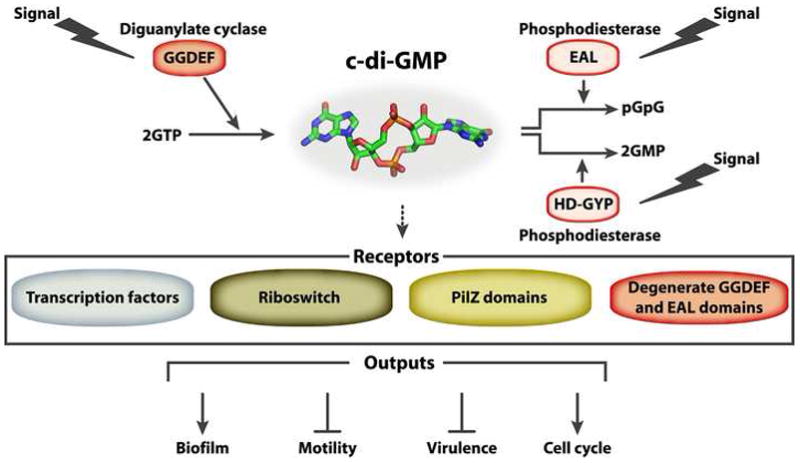

A key regulator of bacterial physiology is the nucleotide-based, second messenger c-di-GMP which controls the transition from a free-living, motile lifestyle to a biofilm one. C-di-GMP also controls other cellular processes including virulence, cell-cell signaling, and cell cycle regulation (Figure 1). Diguanylate cyclase (DGC) proteins containing the GGDEF domain produce c-di-GMP [1,2], while phosphodiesterase (PDE) proteins bearing the EAL [3,4] or HD-GYP [5] domains degrade it. Many of the early studies on c-di-GMP focused on the analysis of enzymatic activities of individual DGC and PDE proteins and biological responses involving c-di-GMP. While recent genome-wide studies have revealed redundancies and specificities of DGCs and PDEs on a broader scale, much less is known regarding c-di-GMP circuitries and signaling mechanisms. Here, we focus in particular on recent efforts to elucidate c-di-GMP signaling systems and the effectors that directly couple c-di-GMP production and cellular responses.

Figure 1.

c-di-GMP is a common, bacterial second messenger that controls the transition from a free-living, motile lifestyle to a biofilm one. c-di-GMP is produced by DGC proteins containing the GGDEF domain and degraded by PDE proteins bearing the EAL or HD-GYP domains. c-diGMP is sensed by receptor proteins or RNAs from either the PilZ, degenerate GGDEF or EAL domain, transcriptional factors or riboswitch families. Typically, receptor proteins then interact with a downstream target to affect a particular cellular function.

Regulation of active DGCs and PDEs

Many GGDEF, EAL and HD-GYP domains occur in diverse multi-domain signaling proteins and as part of multi-component signaling systems, suggesting a role for c-di-GMP in sensing environmental cues [6]. While input signals for the majority of these proteins remain to be discovered, recent studies have begun to shed light on the mechanisms of enzyme activation by environmental signals. The environmental regulation of c-di-GMP homeostasis is achieved by the incorporation of one of several domains into GGDEF and EAL domain-containing proteins. These domains include those that react to light (BlrP1 from Klebsiella pneumonia [7], BphG1 from Rhodobacter sphaeroides [8]) or gases (DosC and DosP from E. coli [9], BpeGReg from Bordetella pertussis [10], AxDGC2 and AxPDEA1 from Acetobacter xylinum [11,12]). Common domains for these types of regulation are Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS), Light-Oxygen-Voltage (LOV), Blue Light Using FAD (BLUF) photoreceptor, and globin domains, which use cofactors, such as flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) or heme. Protein-protein interactions involving DGCs and PDEs with proteins containing sensory domains have also been shown to control enzymatic activities. In Legionella pneumophila, the activity of a DGC is inhibited by the NO receptor H-NOX1 (a Heme Nitric oxide/OXygen (H-NOX) domain-containing protein) in the NO-ligated state [13]. In Rhodopseudomonas palustris, light-dependent activation of PapB, a photoreceptor with a BLUF domain [14], regulates the PDE activity of PapA.

Alternatively, response regulator enzymes with receiver domains occur as modules in multi-component signaling systems. Examples are the Borrelia burgdorferi Rrp1 [1], V. cholerae PDE VieA [15], the P. aeruginosa DGC WspR [16] and the P. aeruginosa PDE SadR (also known as RocR) [17,18]. Sensing of the environment in these systems is achieved by transmembrane sensor proteins that react to surface growth conditions or other external stimuli. Molecular mechanisms for the activation of DGCs and PDEs by response regulator domains are well established. Pioneering work on Caulobacter crescentus PleD, a response regulator DGC involved in polar development, established key concepts in c-di-GMP signaling, including the dimerization of GGDEF domains by phosphorylated receiver domains and the presence of a widely used, inhibitory c-di-GMP-binding site (I-site) [19,20]. In essence, these regulatory mechanisms are conserved in P. aeruginosa WspR[21].

Signaling networks incorporating catalytically inactive GGDEF and EAL domain-containing effectors

Several bioinformatic, structural and functional studies determined sequence requirements for active DGCs and PDEs, but also highlighted the existence of catalytically inactive GGDEF and EAL domain-containing proteins in large numbers. Degenerate GGDEF and EAL domains are a major class of c-di-GMP effectors. Signal output often involves features that were maintained from active enzymes, such as the presence of I-site motifs and domain oligomerization. These degenerate GGDEF and/or EAL domain-containing proteins form central modules in signaling networks. Two of the more extensively studied systems are involved in the control of the cell cycle in C. crescentus and the commitment to stable cell adhesion in P. fluorescens biofilms. These are discussed below in more detail.

One example of an enzymatically inactive c-di-GMP-binding protein is PopA, which contains two receiver domains and a GGDEF domain with a conserved I-site and degenerate active site [22]. In C. crescentus, PopA regulates cell cycle progression. C. crescentus undergoes asymmetric cell division, forming a motile swarmer cell and sessile stalked cell [22]. A coordinated integration of c-di-GMP and two-component signaling ensures proper progression through the division cycle [23]. During the G1-to-S phase transition, PopA is sequestered to the old pole, where it is involved in recruiting proteins required for the degradation of the master cell-cycle regulator CtrA, which controls cell cycle-related genes and directly binds the chromosomal origin of replication, occluding replication initiation factors. Polar localization of PopA is mediated by binding of c-di-GMP to PopA’s I-site [22]. C-di-GMP levels are regulated at the flagellated pole by the opposing activities of a PDE, PdeA, and the DGC, DgcB, until the G1-S transition. Transition into S phase is marked by PdeA degradation and by the concomitant phosphorylation and polar localization of another response regulator DGC, PleD. DgcB and PleD activity subsequently promote entry of the cell into S-phase and morphogenesis of the stalked pole [23].

Similarly to PopA, P. aeruginosa PelD, a protein that regulates production of PEL exopolysaccharide and biofilm formation, requires c-di-GMP binding for its function [24]. Secondary structure predictions indicate some structural similarity of PelD with GGDEF domains. More importantly, binding of c-di-GMP depends on a conserved RxxD motif resembling an I-site found in active DGCs [24]. Another example of this family of c-di-GMP receptors appears to be CdgG of V. cholerae. Although it remains to be determined whether CdgG can bind to c-di-GMP, genetic and enzymatic analysis show that this protein is not a DGC and its RxxD motif is critical for its function [25], i.e., the negative regulation of biofilm formation through a yet unknown mechanism. Together, these studies highlight the mechanistic conservation of inactive GGDEF domains as signal integrators.

Similar to proteins with degenerate GGDEF domains, many enzymatically inactive PDEs retain their ability to bind to c-di-GMP and regulate cellular processes. Interestingly, several proteins contain both inactive GGDEF and EAL domains, such as P. aeruginosa FimX [26,27] or P. fluorescens LapD [28]. LapD was identified as a new class of c-di-GMP-binding transmembrane proteins that control the cell-surface localization of the large cell surface adhesin LapA via an inside-out signal transduction mechanism, and thus regulating biofilm formation [28,29]. Binding of c-di-GMP to LapD’s cytoplasmic EAL domain alters the conformation of the receptor, and the signal is propagated from the GGDEF-EAL module to the output domain through a HAMP (Histidine kinases, Adenyl cyclases, Methyl-accepting proteins and Phosphatases) domain [30]. As a consequence, LapD sequesters the periplasmic protease LapG, which prevents LapA processing and ensures stable anchorage of cells via the intact adhesin [29,30]. Cellular c-di-GMP levels are inversely regulated by the PDE RapA [31], whose expression is regulated on a transcriptional level in response to phosphate availability, and a subset of three DGCs [32]. Whether signaling specificity is achieved by direct protein-protein interactions that are similar to the network architecture described for Caulobacter cell cycle regulation remains to be shown.

FimX of P. aeruginosa, a GGDEF-EAL domain-containing protein with little to no activity, also senses c-di-GMP via a degenerate EAL domain. Mutation of the degenerate GGDEF or EAL domains of a fluorescently tagged FimX construct alters the single polar localization of FimX to a bi-polar distribution, and regulates the assembly of type IV pili and twitching motility [26]. Qi and colleagues has shown that c-di-GMP binding to the EAL domain induces long-range conformational changes, establishing a potential mechanism for its function as a c-di-GMP receptor [33].

c-di-GMP signaling at the transcriptional level

C-di-GMP also regulates gene expression, using a diverse group of specific receptors. One example is FleQ, which activates expression of flagella biosynthesis genes and represses transcription of genes involved in exopolysaccharide biosynthesis in P. aeruginosa [34]. FleQ is an AAA domain-containing protein that has been classified as a sigma54-dependent transcriptional activator. C-di-GMP binding to FleQ results in the disassembly of FleQ•DNA complexes [34]. The mechanism by which c-di-GMP binding alters FleQ function remains to be determined.

The Clp transcriptional regulators from the plant pathogens Xanthomonas campestris [35] and Xanthomonas axonopodis [36] have been shown to bind c-di-GMP. These CRP (cAMP Receptor Protein)/FNR(regulator of fumarate and nitrate reduction) superfamily members comprise an N-terminal β-barrel-containing domain and C-terminal DNA binding domain [37]. In contrast to previously characterized CRP-like proteins, Clp binds to its target DNA sites in the absence of any ligand. However, Clp undergoes structural rearrangements and loses its DNA binding ability upon incubation with c-di-GMP [37]. Identification of a CRP family protein that functions as a c-di-GMP receptor protein whose DNA binding ability is allosterically inhibited is an elegant example in evolution of nucleotide-based signaling systems. In contrast, Burkholderia cenocepacia Bcam139, another c-di-GMP-binding CRP/FNR family protein, shows enhanced DNA binding in the presence of the dinucleotide [38].

The transcriptional regulator VpsT from V. cholerae is an example of a novel c-di-GMP receptor [39]. VpsT inversely regulates expression of motility and matrix production genes in a c-di-GMP-dependent manner. VpsT consists of a non-canonical, N-terminal receiver and a C-terminal helix-turn-helix domain. A crystal structure of VpsT revealed that, unlike previously described receiver domains, VpsT has an additional helix (α6) at its C-terminus. Dimerization utilizing this helix is facilitated by binding of two intercalated c-di-GMP molecules to the base of the VpsT dimer. VpsT binds c-di-GMP using a 4-residue-long, conserved sequence, W[F/L/M][T/S]R [39]. Mutations in the conserved c-di-GMP binding motif or the dimerization interface abolish c-di-GMP binding and the ability of VpsT to bind to its target sequences.

A recent study has shown that Klebsiella pneumoniae MrkH, a PilZ domain-containing transcriptional activator, also binds to its target promoters only in the presence of c-di-GMP [40], although the exact molecular mechanism remains to be determined.

c-di-GMP signaling at a post-translational level via PilZ domains

PilZ domain-containing proteins were first identified by computational studies as potential c-di-GMP receptors and have wide phylogenetic distribution [41]. PilZ domains occur either as single domain proteins or in conjunction with other domains predicted to have enzymatic, regulatory or transport functions [41]. Most genomes encode more than one of these potential receptors, with YcgR from E. coli and BcsA from Gluconacetobacter xylinus being the first experimentally verified c-di-GMP receptors of this family [42].

Structures of several PilZ domain proteins alone and in complex with c-di-GMP have been determined recently. These include YcgRN-PilZ family proteins, represented by VCA0042/PlzD [43] and PP4397 [44], which contains an N-terminal YcgR-like domain, and PP4608 [45], a single-domain PilZ protein. While the fold of the different proteins is very similar, some of the molecular details, such as c-di-GMP binding stoichiometry, affinity, and dinucleotide-induced changes in quaternary structure, appear to be different for the individual proteins. A common feature of PilZ domains is a seven-residue loop, designated the —c-di-GMP switch, which invariably undergoes a conformational change upon c-di-GMP binding. In addition, the conserved RxxxR and D/NxSxxG motifs of the PilZ domains are critical for c-di-GMP binding [43–45]. These properties have been exploited in the design of the first genetically encoded c-di-GMP sensor [46], which allows detection of changes in the cellular c-di-GMP concentration in a diverse set of bacteria, highlighting its potential to further studies of c-di-GMP on a cellular and potentially sub-cellular level.

In general, PilZ proteins studied to date are activated by c-di-GMP and most of them function at the post-translational level via protein-protein interactions. One of the best studied examples is YcgR from E. coli, which binds c-di-GMP and interacts with components of the flagellar motor to affect directional switching and possibly speed [47–49].

PilZ domain proteins impact diverse cellular processes. In V. cholerae, mutations in three of the five PilZ domain proteins impact motility, biofilm formation and intestinal colonization [50]. At least one of the seven P. aeruginosa PilZ proteins (PilZ) is required for twitching motility, while another (Alg44) is required for alginate production [51]. It remains to be seen whether similar mechanisms control other PilZ-type c-di-GMP receptors that affect production of exopolysaccharide, virulence.

Regulation of gene expression by c-di-GMP-binding riboswitches

The discovery of new classes of riboswitches—mRNA segments controlling gene expression, which specifically bind c-di-GMP—has revealed a completely new level of regulation that involves this dinucleotide [52,53]. Thus far, two main classes, the c-di-GMP I and II riboswitches, respectively, have been identified in computational searches and validated experimentally. Crystallographic analyses of the c-di-GMP-bound aptamers has elucidated the overall structures and mode of ligand binding [54–56]. While both riboswitches bind c-di-GMP in an asymmetric fashion involving somewhat similar molecular interactions, the sequences and structural motifs of the RNA aptamers that accommodate c-di-GMP are quite different, suggesting that they evolved independently. These regulatory motifs are widely used and can occur in large numbers indicating the major potential of aptamer-based c-di-GMP signaling.

Conclusion

Since the discovery of c-di-GMP 26 years ago as an allosteric regulator of cellulose synthase [57], c-di-GMP has become one of the most studied signaling molecules, controlling diverse cellular processes in bacteria. There remain many unsolved questions regarding the mechanism of c-di-GMP signaling. Various systems studied in detail thus far suggest that both general and more localized signals can be generated and integrated to control different cellular processes. Future studies will need to address the overall mechanism of localization of signaling reactions, correlation of the global c-di-GMP pool and affinities of c-di-GMP receptors within signaling networks ultimately revealing c-di-GMP signaling specificity. Genetic and biochemical studies suggest that other types of c-di-GMP receptors exist. Although the identities of some receptors are known [58], the identities of many other receptors have yet to be determined. Regulation of c-di-GMP homeostasis at transcriptional, translational and post-translational levels, the building principles of c-di-GMP-dependent signaling cascades, and the integration of these pathways in other environmental signaling networks is being elucidated [59,60], but we have a limited understanding of regulatory interplays. On the protein level, we are only beginning to appreciate the extent to which GGDEF, EAL and HD-GYP domain-containing proteins are functionally diversified. As discussed above, some have evolved to function as c-di-GMP effector proteins, while others have regulatory functions independent of c-di-GMP signaling. It also remains to be determined whether some of the mechanistic principles play a role in signaling and overall function of c-di-AMP, a recently discovered dinucleotide similar to c-di-GMP [61]. Such studies will lead to a better understanding of c-di-GMP signaling mechanisms and c-di-GMP signal transduction pathways that are critical for biology of a broad range of bacteria.

Table 1.

C-di-GMP-specific effectors.

| Protein | Organism | Mechanism | Biological output | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription factors | ||||

| FleQ | P. aeruginosa | Release from DNA | Biofilm formation Motility | [34] |

| VpsT | V. cholerae | Dimerization-induced DNA binding | Biofilm formation Motility | [39] |

| Clp |

Xanthomonas campestris Xanthomonas axopodis |

Release from DNA | virulence | [35,36] |

| Bcam1349 | Burkholderia cenocepacia | Ligand-enhanced DNA binding | Biofilm formation Virulence | [38] |

| PilZ domain-containing proteins | ||||

| YcgR | E. coli | Protein-protein interaction | Direction of flagellar switching | [47–49] |

| DcgR | C. crescentus | Protein-protein interaction | Motility | [62] |

| Alg44 | P. aeruginosa | Protein-protein interaction (?) | Alginate production | [51] |

| Plz | Vibrio choleare | unknown | Motility Biofilm formation Virulence | [50] |

| MrkH | Klebsiella pneumoniae | DNA binding | Type 3 Fimbriae expression and biofilm formation | [40] |

| GGDEF and/or EAL domain-containing proteins | ||||

| FimX | P. aeruginosa | Conformational change | Twitching motility | [33] |

| LapD | P. fluorescens | Disruption of an autoinhibited conformation | Biofilm formation | [30] |

| PelD | P. aeruginosa | unknown | Exopolysaccharide production | [24] |

| PopA | C. crescentus | Spatial redistribution in the cell | Cell cycle regulation | [23] |

| Others | ||||

| PNPase | E. coli | Enzyme activation | RNA processing | [58] |

| Riboswitches | ||||

| Class I |

V. cholerae Vc2(tfoX) |

RNA compaction, Structural rearrangement | Gene expression | [53] |

| Class II | Clostridium difficile | Activation of ribozyme self-splicing | Translational control | [52] |

Acknowledgments

We apologize to those authors whose important work we were unable to cite due to space restrictions. This work was supported by the NIH through grants AI055987 (F.Y.) and GM081373 (H.S.), and a PEW scholar award in Biomedical Sciences (H.S.). We thank Mark Gomelsky for his comments on the review.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

• Of special interest

•• Of outstanding interest

- 1.Ryjenkov DA, Tarutina M, Moskvin OV, Gomelsky M. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1792–1798. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1792-1798.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul R, Weiser S, Amiot NC, Chan C, Schirmer T, Giese B, Jenal U. Cell cycle-dependent dynamic localization of a bacterial response regulator with a novel di-guanylate cyclase output domain. Genes Dev. 2004;18:715–727. doi: 10.1101/gad.289504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christen M, Christen B, Folcher M, Schauerte A, Jenal U. Identification and characterization of a cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase and its allosteric control by GTP. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30829–30837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt AJ, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M. The ubiquitous protein domain EAL is a cyclic diguanylate-specific phosphodiesterase: enzymatically active and inactive EAL domains. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4774–4781. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4774-4781.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan RP, Fouhy Y, Lucey JF, Crossman LC, Spiro S, He YW, Zhang LH, Heeb S, Camara M, Williams P, et al. Cell-cell signaling in Xanthomonas campestris involves an HD-GYP domain protein that functions in cyclic di-GMP turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6712–6717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600345103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Galperin MY. Diversity of structure and function of response regulator output domains. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7•.Barends TR, Hartmann E, Griese JJ, Beitlich T, Kirienko NV, Ryjenkov DA, Reinstein J, Shoeman RL, Gomelsky M, Schlichting I. Structure and mechanism of a bacterial light-regulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Nature. 2009;459:1015–1018. doi: 10.1038/nature07966. A structural study reports the molecular mechansim of PDE that is regulated by light. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarutina M, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M. An unorthodox bacteriophytochrome from Rhodobacter sphaeroides involved in turnover of the second messenger c-di-GMP. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34751–34758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuckerman JR, Gonzalez G, Sousa EH, Wan X, Saito JA, Alam M, Gilles-Gonzalez MA. An oxygen-sensing diguanylate cyclase and phosphodiesterase couple for c-di-GMP control. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9764–9774. doi: 10.1021/bi901409g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan X, Tuckerman JR, Saito JA, Freitas TA, Newhouse JS, Denery JR, Galperin MY, Gonzalez G, Gilles-Gonzalez MA, Alam M. Globins synthesize the second messenger bis-(3'-5')-cyclic diguanosine monophosphate in bacteria. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang AL, Tuckerman JR, Gonzalez G, Mayer R, Weinhouse H, Volman G, Amikam D, Benziman M, Gilles-Gonzalez MA. Phosphodiesterase A1, a regulator of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum, is a heme-based sensor. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3420–3426. doi: 10.1021/bi0100236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi Y, Rao F, Luo Z, Liang ZX. A flavin cofactor-binding PAS domain regulates c-di-GMP synthesis in AxDGC2 from Acetobacter xylinum. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10275–10285. doi: 10.1021/bi901121w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson HK, Vance RE, Marletta MA. H-NOX regulation of c-di-GMP metabolism and biofilm formation in Legionella pneumophila. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77:930–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanazawa T, Ren S, Maekawa M, Hasegawa K, Arisaka F, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Ohta H, Masuda S. Biochemical and physiological characterization of a BLUF protein-EAL protein complex involved in blue light-dependent degradation of cyclic diguanylate in the purple bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10647–10655. doi: 10.1021/bi101448t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tischler AD, Camilli A. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:857–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hickman JW, Tifrea DF, Harwood CS. A chemosensory system that regulates biofilm formation through modulation of cyclic diguanylate levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14422–14427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507170102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuchma SL, Connolly JP, O'Toole GA. A three-component regulatory system regulates biofilm maturation and type III secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1441–1454. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1441-1454.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kulasekara HD, Ventre I, Kulasekara BR, Lazdunski A, Filloux A, Lory S. A novel two-component system controls the expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa fimbrial cup genes. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:368–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul R, Abel S, Wassmann P, Beck A, Heerklotz H, Jenal U. Activation of the diguanylate cyclase PleD by phosphorylation-mediated dimerization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29170–29177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wassmann P, Chan C, Paul R, Beck A, Heerklotz H, Jenal U, Schirmer T. Structure of BeF3- -modified response regulator PleD: implications for diguanylate cyclase activation, catalysis, and feedback inhibition. Structure. 2007;15:915–927. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De N, Navarro MV, Raghavan RV, Sondermann H. Determinants for the activation and autoinhibition of the diguanylate cyclase response regulator WspR. J Mol Biol. 2009;393:619–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duerig A, Abel S, Folcher M, Nicollier M, Schwede T, Amiot N, Giese B, Jenal U. Second messenger-mediated spatiotemporal control of protein degradation regulates bacterial cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 2009;23:93–104. doi: 10.1101/gad.502409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23••.Abel S, Chien P, Wassmann P, Schirmer T, Kaever V, Laub MT, Baker TA, Jenal U. Regulatory Cohesion of Cell Cycle and Cell Differentiation through Interlinked Phosphorylation and Second Messenger Networks. Mol Cell. 2011;43:550–560. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.018. This report identifies a protein interaction network integrating c-di-GMP signaling, protein phoshorylation and degradation to control bacterial cell cycle progression and development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee VT, Matewish JM, Kessler JL, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Lory S. A cyclic-di-GMP receptor required for bacterial exopolysaccharide production. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:1474–1484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beyhan S, Odell LS, Yildiz FH. Identification and characterization of cyclic diguanylate signaling systems controlling rugosity in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7392–7405. doi: 10.1128/JB.00564-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazmierczak BI, Lebron MB, Murray TS. Analysis of FimX, a phosphodiesterase that governs twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1026–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navarro MV, De N, Bae N, Wang Q, Sondermann H. Structural analysis of the GGDEF-EAL domain-containing c-di-GMP receptor FimX. Structure. 2009;17:1104–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newell PD, Monds RD, O'Toole GA. LapD is a bis-(3',5')-cyclic dimeric GMP-binding protein that regulates surface attachment by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0–1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3461–3466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808933106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29••.Newell PD, Boyd CD, Sondermann H, O'Toole GA. A c-di-GMP effector system controls cell adhesion by inside-out signaling and surface protein cleavage. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000587. Genetic and biochemical studies reveal molecular basis of an inside-out signaling switch linking cytoplasmic c-di-GMP levels to proteolysis of an extracellular cell adhesion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navarro MV, Newell PD, Krasteva PV, Chatterjee D, Madden DR, O'Toole GA, Sondermann H. Structural basis for c-di-GMP-mediated inside-out signaling controlling periplasmic proteolysis. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monds RD, Newell PD, Gross RH, O'Toole GA. Phosphate-dependent modulation of c-di-GMP levels regulates Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 biofilm formation by controlling secretion of the adhesin LapA. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:656–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newell PD, Yoshioka S, Hvorecny KL, Monds RD, O'Toole GA. Systematic Analysis of Diguanylate Cyclases That Promote Biofilm Formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:4685–4698. doi: 10.1128/JB.05483-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi Y, Chuah ML, Dong X, Xie K, Luo Z, Tang K, Liang ZX. Binding of cyclic diguanylate in the non-catalytic EAL domain of FimX induces a long-range conformational change. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2910–2917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.196220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34•.Hickman JW, Harwood CS. Identification of FleQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a c-di-GMP-responsive transcription factor. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:376–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06281.x. Describes transcriptional regulation via a c-di-GMP-binding protein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35•.Tao F, He YW, Wu DH, Swarup S, Zhang LH. The cyclic nucleotide monophosphate domain of Xanthomonas campestris global regulator Clp defines a new class of cyclic di-GMP effectors. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:1020–1029. doi: 10.1128/JB.01253-09. Describes identification of a CRP family protein that functions as a c-di-GMP receptor protein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36•.Leduc JL, Roberts GP. Cyclic di-GMP allosterically inhibits the CRP-like protein (Clp) of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7121–7122. doi: 10.1128/JB.00845-09. Describes identification of a CRP family protein that functions as a c-di-GMP receptor protein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37•.Chin KH, Lee YC, Tu ZL, Chen CH, Tseng YH, Yang JM, Ryan RP, McCarthy Y, Dow JM, Wang AH, et al. The cAMP receptor-like protein CLP is a novel c-di-GMP receptor linking cell-cell signaling to virulence gene expression in Xanthomonas campestris. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:646–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.076. Structure-function analysis of a CRP family protein that functions as a c-di-GMP receptor protein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fazli M, O'Connell A, Nilsson M, Niehaus K, Dow JM, Givskov M, Ryan RP, Tolker-Nielsen T. The CRP/FNR family protein Bcam1349 is a c-di-GMP effector that regulates biofilm formation in the respiratory pathogen Burkholderia cenocepacia. Mol Microbiol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39•.Krasteva PV, Fong JC, Shikuma NJ, Beyhan S, Navarro MV, Yildiz FH, Sondermann H. Vibrio cholerae VpsT regulates matrix production and motility by directly sensing cyclic di-GMP. Science. 2010;327:866–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1181185. Structure-function analysis establishes a non-canonical response receiver as c-di-GMP-dependent, transcriptional master regulator for V. cholerae biofilm formation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilksch JJ, Yang J, Clements A, Gabbe JL, Short KR, Cao H, Cavaliere R, James CE, Whitchurch CB, Schembri MA, et al. MrkH, a Novel c-di-GMP-Dependent Transcriptional Activator, Controls Klebsiella pneumoniae Biofilm Formation by Regulating Type 3 Fimbriae Expression. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002204. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Amikam D, Galperin MY. PilZ domain is part of the bacterial c-di-GMP binding protein. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:3–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti739. Based on a bioinformatic analysis, this report identifies PilZ domains as the first c-di-GMP binding modules. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryjenkov DA, Simm R, Romling U, Gomelsky M. The PilZ domain is a receptor for the second messenger c-di-GMP: the PilZ domain protein YcgR controls motility in enterobacteria. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30310–30314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benach J, Swaminathan SS, Tamayo R, Handelman SK, Folta-Stogniew E, Ramos JE, Forouhar F, Neely H, Seetharaman J, Camilli A, et al. The structural basis of cyclic diguanylate signal transduction by PilZ domains. Embo J. 2007;26:5153–5166. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ko J, Ryu KS, Kim H, Shin JS, Lee JO, Cheong C, Choi BS. Structure of PP4397 reveals the molecular basis for different c-di-GMP binding modes by Pilz domain proteins. J Mol Biol. 2010;398:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Habazettl J, Allan MG, Jenal U, Grzesiek S. Solution structure of the PilZ domain protein PA4608 complex with cyclic di-GMP identifies charge clustering as molecular readout. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:14304–14314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46•.Christen M, Kulasekara HD, Christen B, Kulasekara BR, Hoffman LR, Miller SI. Asymmetrical distribution of the second messenger c-di-GMP upon bacterial cell division. Science. 2010;328:1295–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.1188658. Describes development of genetically encoded fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)–based biosensor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47••.Fang X, Gomelsky M. A post-translational, c-di-GMP-dependent mechanism regulating flagellar motility. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:1295–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07179.x. Describes c-di-GMP mediated post-transcriptional regulation of flagellar reversals by interactions of a PilZ-type c-di-GMP receptor with the flagellar switch-complex proteins FliG and FliM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48••.Paul K, Nieto V, Carlquist WC, Blair DF, Harshey RM. The c-di-GMP binding protein YcgR controls flagellar motor direction and speed to affect chemotaxis by a “backstop brake” mechanism. Mol Cell. 2010;38:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.001. Describes c-di-GMP mediated post-transcriptional regulation of flagellar reversals by interactions of a PilZ-type c-di-GMP receptor with the flagellar switch-complex proteins FliG and FliM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49••.Boehm A, Kaiser M, Li H, Spangler C, Kasper CA, Ackermann M, Kaever V, Sourjik V, Roth V, Jenal U. Second messenger-mediated adjustment of bacterial swimming velocity. Cell. 2010;141:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.018. Describes c-di-GMP mediated post-transcriptional regulation of flagellar swimming speed by interactions of a PilZ-type c-di-GMP receptor with particular flagellar motor proteins. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pratt JT, Tamayo R, Tischler AD, Camilli A. PilZ domain proteins bind cyclic diguanylate and regulate diverse processes in Vibrio cholerae. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12860–12870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611593200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Merighi M, Lee VT, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Lory S. The second messenger bis-(3'-5')-cyclic-GMP and its PilZ domain-containing receptor Alg44 are required for alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:876–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee ER, Baker JL, Weinberg Z, Sudarsan N, Breaker RR. An allosteric self-splicing ribozyme triggered by a bacterial second messenger. Science. 2010;329:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1190713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53••.Sudarsan N, Lee ER, Weinberg Z, Moy RH, Kim JN, Link KH, Breaker RR. Riboswitches in eubacteria sense the second messenger cyclic di-GMP. Science. 2008;321:411–413. doi: 10.1126/science.1159519. Bioinformatic identification and experimental validation of c-di-GMP-binding RNA apatmers establish as widely used mechanism for gene regulation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kulshina N, Baird NJ, Ferre-D'Amare AR. Recognition of the bacterial second messenger cyclic diguanylate by its cognate riboswitch. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1212–1217. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith KD, Lipchock SV, Ames TD, Wang J, Breaker RR, Strobel SA. Structural basis of ligand binding by a c-di-GMP riboswitch. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1218–1223. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith KD, Shanahan CA, Moore EL, Simon AC, Strobel SA. Structural basis of differential ligand recognition by two classes of bis-(3'-5')-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate-binding riboswitches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7757–7762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018857108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ross P, Weinhouse H, Aloni Y, Michaeli D, Weinberger-Ohana P, Mayer R, Braun S, de Vroom E, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH, et al. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature. 1987;325:279–281. doi: 10.1038/325279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tuckerman JR, Gonzalez G, Gilles-Gonzalez MA. Cyclic di-GMP activation of polynucleotide phosphorylase signal-dependent RNA processing. J Mol Biol. 2011;407:633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fong JC, Yildiz FH. Interplay between cyclic AMP-cyclic AMP receptor protein and cyclic di-GMP signaling in Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6646–6659. doi: 10.1128/JB.00466-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weber H, Pesavento C, Possling A, Tischendorf G, Hengge R. Cyclic-di-GMP-mediated signalling within the sigma network of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:1014–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Witte G, Hartung S, Buttner K, Hopfner KP. Structural biochemistry of a bacterial checkpoint protein reveals diadenylate cyclase activity regulated by DNA recombination intermediates. Mol Cell. 2008;30:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Christen M, Christen B, Allan MG, Folcher M, Jeno P, Grzesiek S, Jenal U. DgrA is a member of a new family of cyclic diguanosine monophosphate receptors and controls flagellar motor function in Caulobacter crescentus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4112–4117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607738104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]