Abstract

Rationale

Sex differences in the analgesic effects of mu-opioid agonists have been documented extensively in rodents and, to a lesser extent, in non-human primates. To date, there have been few experimental studies investigating this effect in humans, and the conclusions have been equivocal.

Objectives

The aims of the present study were to examine potential sex differences in the analgesic, subjective, performance, and physiological effects of morphine in human research volunteers.

Methods

Using a double-blind outpatient procedure, the present study investigated the effects of intramuscular morphine (0, 5, and 10 mg/70 kg, i.m.) in men (N=8) and women (N=10). The primary dependent measure was analgesia, as assessed by the cold-pressor and mechanical-pressure tests. Secondary dependent measures included subjective, performance, and physiological effects of morphine, as well as plasma levels of morphine.

Results

No differences in the analgesic and performance effects of morphine were observed between men and women, but significant differences in morphine’s subjective effects were found. Specifically, men reported greater positive effects whereas women reported greater negative effects after morphine administration.

Conclusions

These data suggest that in humans, there are sex differences in the subjective mood altering effects of morphine but, based on this limited sample, there is little evidence for sex differences in its analgesic effects.

Keywords: Sex differences, morphine, pain, subjective effects, opioids, humans

INTRODUCTION

Morphine and other mu opioid agonists have long been used clinically to alleviate pain. Recent findings have demonstrated sex differences in the analgesic effects of mu opioids in some species (see Craft, 2003 for review). In rodents, for example, numerous studies have demonstrated that a lower dose of drug is required to produce an equivalent antinociceptive effect in males compared to females (Barrett et al., 2002; Terner et al., 2003; Stoffel et al., 2005). In contrast, there is little evidence for such a phenomenon in non-human primates. One study showed that male rhesus monkeys were more sensitive to low-efficacy mu opioid agonists than females, but there was no sex difference in analgesic effectiveness of the high-efficacy agonist fentanyl (Negus and Mello, 1999). Although there is some evidence that partial (low-efficacy) agonists are more potent and effective for the relief of post-surgical pain in women compared with men (Gear et al., 1996, 1999, 2003; Gordon et al., 1995; Chia et al., 2002), this sex difference has not been reliably observed in studies using laboratory pain models (Sarton et al., 2000; Fillingim et al., 2004, 2005; Zacny and Beckman, 2004; Olofsen et al., 2005).

The current study was designed to examine potential sex differences in the effects of morphine in a controlled setting using the Cold Pressor Test (CPT) and the Mechanical Pressure Test (MPT). The CPT has good predictive validity for various analgesics (Chen et al., 1989; Conley et al., 1997). Both tests have been used to study sex differences in response to analgesia in the absence of drug (CPT: Hellstrom et al., 2000; Lowery et al., 2003; Dixon et al., 2004; Edwards et al., 2004; Mitchell et al., 2004; Thorn et al., 2004; Kowalczyk et al., 2006; but see Jones et al., 2002; Zacny and Beckman, 2004; MPT: Brennum et al., 1989; Chesterton et al., 2003; Clark et al., 1989; Kowalczyk et al., in press; Riley et al., 1998). In most of these studies, women were more sensitive to pain than men. In this study, we hypothesized that women would be more sensitive to the effects of morphine on both pain tests.

METHODS

Participants

Normal, healthy volunteers (8 men, 10 women) aged 21-45 years who had taken opioids at least twice previously for medical purposes were included. Those who reported chronic pain, used over-the-counter analgesics more than 4 times a month, met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, revised) criteria for substance abuse or dependence in the past 2 years, or had current Axis I psychopathology were excluded.

Study Design and General Procedure

Participants completed 12 outpatient sessions. During each session, one of three doses of morphine was administered and pain response was assessed using either the CPT or the MPT. Each condition (pain assay and morphine dose) was tested twice, and in normally menstruating women (N=7) the two sessions were scheduled during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle (Days 2-10 and 19-27 after the onset of menstruation). Menstrual cycle phase was confirmed by measuring plasma levels of estradiol and progesterone and by using ovulation kits. Men and the three women on oral contraceptives were tested at intervals similar to the normally menstruating women. Because preliminary analyses indicated that menstrual cycle phase or oral contraceptives had little effect on responses to morphine, data from all the women were pooled. The study was conducted under double-blind dosing conditions and the order of dose and pain test was randomized. Before testing, participants completed a training session to familiarize them with the study procedures. They were asked to refrain from using alcohol and over-the-counter analgesics during the 12 hours prior to the session, which was confirmed with breath alcohol levels and urine drug toxicologies.

Pharmacodynamic responses were assessed and venous blood samples were collected before and for up to four hours after each drug administration. Capillary gas chromatography/mass spectrometry using trideuterated morphine as an internal standard was used to assess morphine levels.

Cold Pressor Test

The cold pressor apparatus consisted of two water coolers, filled with either warm (37°C) or cold water (4°C; Kowalczyk et al., 2006). The CPT began with an immersion of the forearm into the warm-water bath for 3 minutes. Participants then immersed the forearm into the cold-water bath and were instructed to report the first painful sensation after immersion. They were asked to tolerate the stimulus as long as possible, but were permitted to withdraw their arm from the water if the stimulus was too uncomfortable. Latency to first feel pain (threshold) and to withdraw the arm from the water (tolerance) were recorded by the experimenter. Upon withdrawal, blood pressure was measured and the McGill Pain Questionnaire (see below) was completed. The CPT, which took approximately 15 min to complete, was performed before and again approximately 45 and 205 min after drug administration.

Mechanical Pressure Test

The equipment used for the MPT was modeled after the Forgione-Barber focal pressure stimulator (Glederer & Co., Inc., Paterson, NJ). Pressures of various intensities were applied to the fingers using a dull plastic tip (Lucite, 4 mm in diameter) applied at a continuous pressure. The four intensities that were tested were: 2.83 N (440 g), 3.89 N (600 g), 6.02 N (780 g), and 8.76 N (955 g). Each weight was tested 12 times for a total of 48 presentations per session. The maximum exposure during each trial was 30 sec, but the participant could ask the experimenter to remove the weight if the intensity of the stimulus was too great. During each trial, participants rated the intensity of the stimulus 5, 10, 20, and 30 seconds after the weight was placed on the finger. The rating scale ranged from “not noticeable” to “worst possible pain.” Immediately following the task, the McGill Pain Questionnaire was completed. The MPT, which took approximately 40 min to complete, was performed before and approximately 35 and 185 min after drug administration.

Subjective Pain Measure: McGill Pain Questionnaire

A 15-item shortened form of the McGill Pain Questionnaire (Melzack, 1987) was used to assess the pain experience immediately following the CPT and MPT. Responses to the 15 questions were summed and could range between 15 and 60.

Subjective Drug Effects

Participants completed a 6-item Drug Effects Questionnaire approximately 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 180, and 240 minutes after drug administration. They rated the drug effects according to how they were feeling at that moment on a scale ranging from “No good (bad, etc.) effects at all” to “Very much”. Participants also were asked whether they liked the drug on a scale ranging from “Dislike very much” to “Like very much”. An 18-item visual analog scale was completed before and approximately 115, 175, and 305 min after drug administration. Scores ranged from 0 (“Not at all”) to 100 (“Extremely”). Participants also completed a 13-item Opiate Symptom Checklist (Fraser, et al., 1961; Martin & Fraser, 1961), consisting of true/false questions.

Performance Tasks

Participants completed a 3-minute digit-symbol substitution task, a 10-minute divided attention task, and a 10-minute rapid information-processing task before and approximately 90, 150, and 240 min after drug administration (see Comer, et al., 1999 for details).

Physiological Effects

A blood pressure cuff was used to measure heart rate, and systolic and diastolic pressure (Sentry II Vital Signs Monitor, NBS Medical). A pulse oximeter was used to continuously monitor %SpO2 (Model 400, Palco Laboratories). A Canon Powershot G2 camera was used to take pupil photographs under ambient lighting conditions. Blood pressure, %SpO2, and pupil diameter were recorded before, and 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 180, and 240 min after drug administration.

Drugs

Morphine sulfate solution (0, 5, and 10 mg/70 kg; Elkin-Sinn, Inc.) was injected into the deltoid muscle in a total volume of 1 cc. Doses used clinically for acute pain are 5-30 mg every 4 hr. The oral to parenteral dose conversion for analgesia is generally accepted to be 3:1 (Berdine and Nesbit, 2006), so the intramuscular doses of 5 and 10 mg/70 kg used in the present study are within the upper range that is typically prescribed for the treatment of pain.

Data Analyses

A mixed within- and between-subjects design was used in the current study. Pain task, morphine dose, and time served as within-subjects variables and sex served as the between-subject variable. Primary dependent variables were analgesic responses. The latency to first feel pain and to withdraw the arm from the cold water served as the two primary dependent variables measured in the CPT. The ability to discriminate between two stimuli of varying intensities (P(A)) and readiness to report pain (stoicism, B) served as the two primary dependent variables measured in the MPT (Clark and Dillon, 1973; Gil et al., 1996, and McNicol, 1972). Secondary dependent variables included subjective, performance, and physiologic effects as a function of morphine dose and sex. Repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) for within-subject variables were performed to determine effects of morphine dose and time. Planned comparisons were conducted between each of the morphine doses and between the different time points. Mixed model analyses within the MANCOVA module of Statistica were performed to examine sex differences as a function of dose and time.

RESULTS

Participants

Eighteen participants, including 10 women (9 White, 1 Black) and 8 men (3 White, 2 Black, 1 Asian, and 2 Other) completed the study (Table 1). Three women reported current use of oral contraceptives. Eight volunteers reported some current alcohol use and 6 consumed caffeinated beverages daily. None of the participants smoked cigarettes daily or used other nicotine-containing products. One participant reported twice monthly marijuana use. Others reported previous recreational drug use (Table 1). Three participants began the study but were discontinued for medical reasons (one had an allergic reaction to latex and two experienced vasovagal responses to the CPT) and three discontinued because of side effects of morphine (i.e., nausea and vomiting).

Table 1.

Select demographic information (± one standard deviation) for women (N=10) and men (N=8).

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 31.6 (7.2) | 24.5 (1.8)* |

| Body mass index (m/kg2) | 23.1 (2.8) | 25.0 (2.5) |

| % Participants currently drinking alcohol 1-3 times per week | 50.0 | 37.5 |

| % Participants with a history of recreational marijuana use | 70.0 | 75.0 |

| % Participants with a history of recreational stimulant use (e.g., over-the-counter caffeine, Ecstasy, coca tea, cocaine) | 40.0 | 25.0 |

| % Participants with a history of recreational sedative use | 20.0 | 12.5 |

| % Participants with a history of recreational hallucinogen use | 10.0 | 12.5 |

| % Participants with a history of recreational prescription opioid use | 0.0 | 12.5 |

indicates a significant sex difference (p < 0.01).

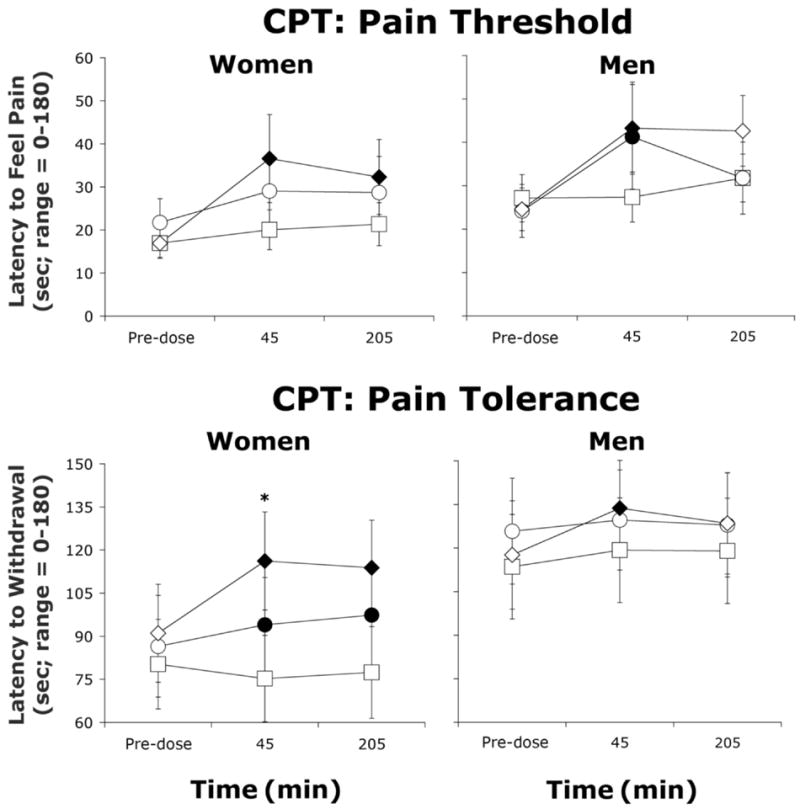

Cold Pressor Test: Threshold and Tolerance

Among women, morphine dose-dependently increased pain tolerance (Figure 1; Dose: F(2,18)=3.9, p≤0.05) and the highest dose increased pain threshold relative to placebo (p≤0.05). Among men, both active doses increased pain threshold relative to placebo (p≤0.05), and the highest dose (10 mg/70 kg) increased pain tolerance (p≤0.05). Between-group analyses revealed no significant differences between the sexes in pain tolerance or threshold during the CPT. Differences in baseline pain threshold and tolerance were not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Average pain threshold and tolerance (± 1 SEM) as a function of morphine dose and time after morphine administration as assessed in the CPT in women (N=10) and men (N=8). Pain threshold was defined as latency to feel pain (0-180 sec) and pain tolerance was defined as latency to withdraw the forearm from the cold water (0-180 sec). Filled symbols represent a significant difference from placebo at that time point. Asterisks represent a significant difference between 5 and 10 mg/70 kg morphine. Squares represent data collected during sessions involving administration of placebo, circles represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 5 mg/70 kg morphine, and diamonds represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 10 mg/70 kg morphine.

Cold Pressor Test: Subjective Pain Ratings

Among women, morphine did not affect subjective ratings of pain as measured by the McGill Pain Questionnaire (data not shown; average sum score=33). In men, morphine also did not decrease ratings of pain (average sum score=39) although pain ratings decreased over the course of the session (Time: F(2,14)=4.7, p≤0.05). Between-group analyses revealed no significant differences in the subjective pain responses between men and women during the CPT.

Cold Pressor Test: Physiological Responses

In both men and women, mean systolic/diastolic pressures were higher after cold water immersions compared to warm water (women: mean systolic/diastolic pressures 113/66 and 120/73 mm Hg and men: 119/68 and 134/81). Compared to women, men exhibited significantly greater increases in systolic (Sex: F(1,16)=9.9, p≤0.01) and diastolic (Sex: F(1,16)=5.0, p≤0.05) pressures during the cold water immersions. Men also had higher diastolic pressures during warm water immersions across time (Sex: F(2,32)=4.1, p≤0.05).

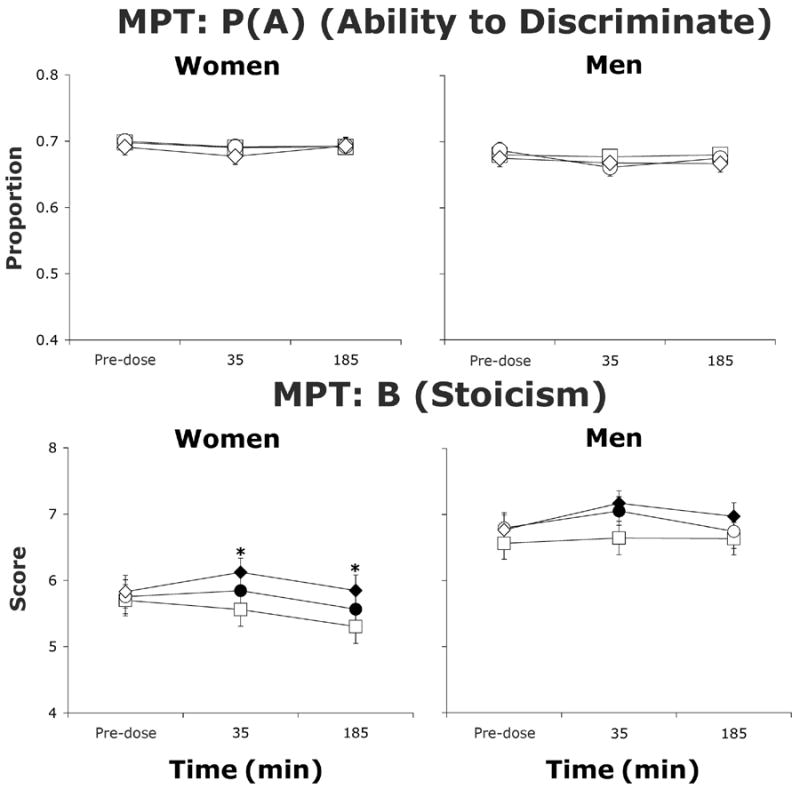

Mechanical Pressure Test: P(A) and B

In women, morphine dose-dependently increased stoicism (B) (Figure 2; Dose: F(2,18)=3.8, p≤0.05). In both women (Time: F(2,18)=10.0, p≤0.001) and men (Time: F(2,14)=4.6, p≤0.05), stoicism varied across time. Men demonstrated greater stoicism than women, an effect that varied across time (Sex × Time: F(2,32)=3.5, p≤0.05), but not morphine dose. Neither group showed dose- or time-related changes in P(A), or ability to discriminate between two stimuli.

Figure 2.

Average ability to discriminate between two stimuli of differing weights P(A) and stoicism (B) (± 1 SEM) as a function of morphine dose and time after morphine administration as assessed in the MPT in women (N=10) and men (N=8). Filled symbols indicate a significant difference from placebo. Asterisks represent a significant difference between 5 and 10 mg/70 kg morphine. Squares represent data collected during sessions involving administration of placebo, circles represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 5 mg/70 kg morphine, and diamonds represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 10 mg/70 kg morphine.

Mechanical Pressure Test: Subjective Pain Ratings

Subjective pain responses as assessed with the McGill Pain Questionnaire (Table 3) decreased as a function of dose and time in women (Dose × Time: F(4,36)=2.9, p≤0.05) and men (Dose × Time: F(4,28)=3.0, p≤0.05). Between-group analyses revealed a Sex × Time interaction (F(2,32)=3.5, p≤0.05), but the Sex × Dose interaction was not significant.

Table 3.

Subjective ratings of pain in response to the MPT. Means (± one standard error of the mean, SEM) are presented for sum scores of the McGill Pain Questionnaire across morphine dose and time. Both women (N=10) and men (N=8) had significant dose by time interactions.

| 0 mg / 70 Kg | 5 mg / 70 Kg | 10 mg / 70 Kg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 35 min | 185 min | Baseline | 35 min | 185 min | Baseline | 35 min | 185 min | |

| Women | 31.3 (1.9) | 32.7 (2.1) | 33.0 (2.0) | 31.7 (1.9) | 29.7 (1.8)a | 30.8 (2.0)a | 30.8 (2.2) | 29.7 (2.1)a | 30.4 (2.1)a |

| Men | 32.2 (1.3) | 31.8 (1.2) | 36.0 (2.6) | 38.3 (2.3)a | 32.8 (2.3) | 34.8 (2.4) | 36.8 (2.6)a | 29.8 (1.4) | 31.2 (2.1)a |

indicates a difference from placebo.

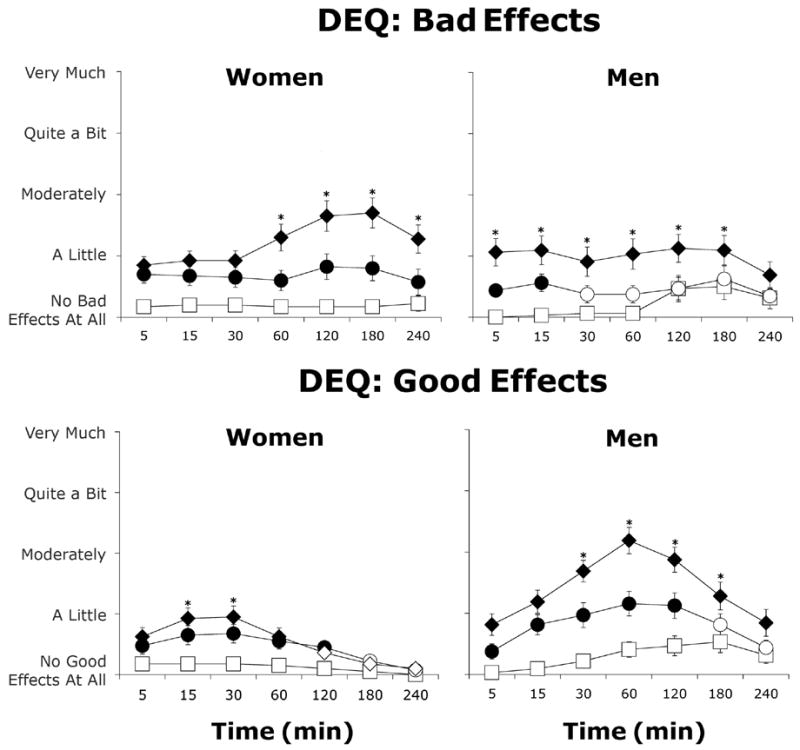

Subjective Ratings of Drug Effects

Among women, morphine dose-dependently increased subjective ratings of both “Bad Effect” (Figure 3; Dose: F(2,18)=14.2, p≤0.001) and “Good Effect” (Dose: F(2,18)=6.0, p≤0.01). The bad effects were highest at 180 min after 10 mg/70 kg morphine, while the maximum ratings for good drug effects occurred 30 min after 10 mg/70 kg morphine. Among men, morphine also increased ratings of both “Bad Effect” (Dose: F(2,14)=7.1, p≤0.01) and “Good Effect” (Dose: F(2,14)=16.2, p≤0.001). In the men, peak ratings of bad drug effects occurred 15 min after morphine administration, whereas ratings of good drug effects peaked 60 min after morphine administration. Compared to women, men reported higher ratings of “Good Effect” regardless of what dose they received (Sex: F(1,16)=5.9, p≤0.05).

Figure 3.

Average subjective ratings of “I feel a good drug effect” and “I feel a bad drug effect” (± 1 SEM) as a function of morphine dose and time after morphine administration in women (N=10) and men (N=8). Filled symbols indicate a significant difference from placebo. Asterisks represent a significant difference between 5 and 10 mg/70 kg morphine. Squares represent data collected during sessions involving administration of placebo, circles represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 5 mg/70 kg morphine, and diamonds represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 10 mg/70 kg morphine.

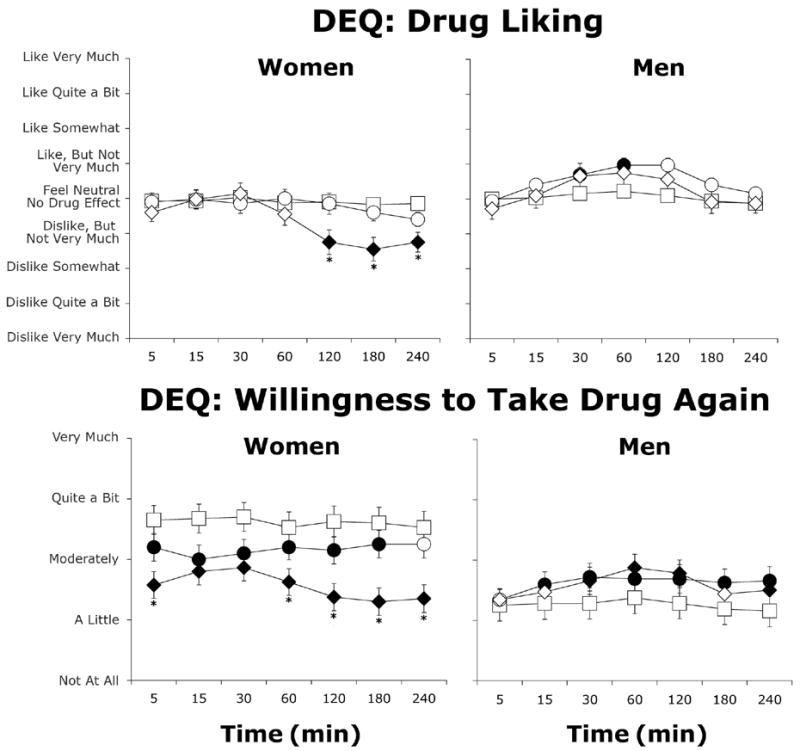

Women reported less drug liking at the highest dose of morphine compared to placebo (Figure 4), and they were less willing to take the drug again as dose increased (Figure 4; Dose: F(2,18)=5.9, p≤0.01). In contrast, as the dose increased, men reported greater drug liking and willingness to take the drug again. Ratings of strength of drug effect increased with increasing dose in both men and women (data not shown; p≤0.001 and p≤0.01 for the main effects of Dose and Time, respectively, in both groups), with peak ratings between “Definite Mild Effect” and “Moderately Strong Effect.” Both men and women also reported that morphine was sedative-like (data not shown). Men reported greater willingness to take the drug again (Sex × Dose: F(2,32)=4.8, p≤0.05) and greater good drug effects (Sex × Dose: F(2,32)=5.1, p<0.01). Men and women also differed in ratings of drug liking (Sex × Time: F(6,96)=3.3, p≤0.05) and good drug effects (Sex × Time: F(6,96)=4.8, p≤0.05) across time. There were no sex differences in ratings of drug strength or type.

Figure 4.

Average subjective ratings of “Drug Liking” and “Willingness to Take the Drug Again” (± one SEM) as a function of morphine dose and time after morphine administration in women (N=10) and men (N=8). Filled symbols indicate a significant difference from placebo. Asterisks represent a significant difference between 5 and 10 mg/70 kg morphine. Squares represent data collected during sessions involving administration of placebo, circles represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 5 mg/70 kg morphine, and diamonds represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 10 mg/70 kg morphine.

Morphine affected other subjective responses to a similar extent in men and women (Table 2). For example, morphine decreased ratings of “Able to Concentrate,” “Alert,” and “Self-confident” and increased ratings of “Confused,” “High,” and “Sedated”. Morphine increased ratings of “Bad Effect” and “Tired” to a greater extent in women than in men (Sex × Dose × Time interactions; p≤0.05). Men reported greater increases in ratings of “Good Effect” than women (p<0.01; Table 2). Sum scores on the Opiate Symptom Checklist (data not shown) dose-dependently increased in both men (Dose: F(2,14)=21.3, p≤0.0001) and women (Dose: F(2,18)=27.0, p≤0.0001), with no between-group differences.

Table 2.

Selected mean visual analog scale ratings (± one standard error of the mean, SEM) for women (N=10) and men (N=8) averaged across the session as a function of morphine dose.

| Women | Men | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mg/70 kg | 5 mg/70 kg | 10 mg/70 kg | 0 mg/70 kg | 5 mg/70 kg | 10 mg/70 kg | ||

| Able to Concentrate | ↓ | 56.4 (2.1) | 51.4 (2.3) | 42.6 (2.6) a,b | 59.5 (3.0) | 59.6 (2.6) | 48.7 (2.9) a,b |

| Alert | ↓ | 57.7 (2.3) | 53.8 (2.4) | 43.6 (2.7) a,b | 56.0 (2.9) | 56.6 (2.6) | 46.7 (2.9) a,b |

| Bad Effect | ↑ | 3.8 (1.3) | 14.0 (2.4) | 32.3 (3.2) a,b | 10.1 (2.3) | 10.5 (2.2) | 18.7 (2.9) a,b |

| Confused | ↑ | 2.0 (0.5) | 4.3 (1.0) | 8.3 (1.4) a | 12.7 (2.0) | 16.4 (2.5) | 19.8 (2.8) a |

| Focused | ↓/- | 48.5 (2.1) | 44.6 (2.2) | 36.3 (2.4) a,b | 53.2 (3.0) | 50.8 (2.7) | 45.8 (2.8) |

| Good Effect | ↑ | 1.1 (0.4) | 5.6 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.3) a | 9.8 (2.1) | 16.0 (2.4) | 25.0 (3.0) a |

| High | ↑ | 8.5 (1.7) | 11.3 (1.8) | 20.8 (2.4) a,b | 8.0 (1.9) | 15.0 (2.4) | 25.3 (2.9) a,b |

| Hungry | ↓/- | 22.7 (2.5) | 21.6 (2.4) | 16.8 (2.2) a,b | 27.8 (3.2) | 27.0 (3.2) | 26.0 (3.1) |

| Sedated | ↑ | 7.0 (1.5) | 19.2 (2.5) a | 37.6 (3.1) a,b | 16.6 (2.9) | 24.1 (3.1) | 34.2 (3.5) a,b |

| Self-confident | ↓ | 65.6 (1.8) | 64.8 (2.2) | 59.0 (2.2) a | 73.8 (2.2) | 74.1 (2.1) | 66.8 (2.3) a,b |

| Tired | ↑ | 40.3 (2.5) | 44.0 (2.5) | 59.5 (2.8) a,b | 46.3 (3.0) | 44.5 (3.1) | 53.9 (3.1) b |

indicates a significant difference from placebo, and

indicates a significant difference between 5 and 10 mg/70 kg morphine. Arrows represent the direction of effect as a function of morphine dose.

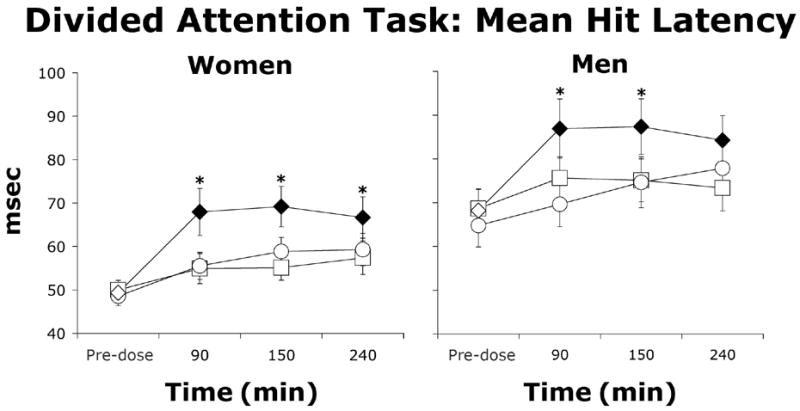

Performance Effects

Among both men and women, morphine increased the latency to correctly identify a target (mean hit latency) during the divided attention task (Figure 5, Table 4; Dose × Time: p≤0.05). Morphine decreased total correct and total attempted patterns on the digit symbol substitution task in both men and women (Table 4). In addition, the number of missed targets on the rapid information processing task increased by dose and time in both men and women (Table 4; Dose × Time: p≤0.05). No sex differences were observed for any of the cognitive tasks.

Figure 5.

Representative cognitive effect of morphine demonstrated by performance on the divided attention task (DAT) defined by average hit latency (± one SEM) as a function of morphine dose and time after morphine administration in women (N=10) and men (N=8). Filled symbols indicate a significant difference from placebo. Asterisks represent a significant difference between 5 and 10 mg/70 kg morphine. Squares represent data collected during sessions involving administration of placebo, circles represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 5 mg/70 kg morphine, and diamonds represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 10 mg/70 kg morphine.

Table 4.

Selected dependent measures on the performance tasks (± one standard error of the mean, SEM) for women (N=10) and men (N=8) averaged across the session as a function of morphine dose.

| Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mg/70 kg | 5 mg/70 kg | 10 mg/70 kg | 0 mg/70 kg | 5 mg/70 kg | 10 mg/70 kg | |

| Divided Attention Task | ||||||

| Mean hit latency | 54.4 (1.6) | 55.6 (1.6) | 63.3 (2.3) a,b | 73.2 (2.4) | 71.7 (2.7) | 81.7 (3.0) a,b |

| Digit Symbol Substitution Task | ||||||

| Total correct | 81.2 (1.0) | 80.9 (1.1) | 76.9 (1.4) a,b | 80.1 (1.7) | 77.6 (1.8) | 76.2 (1.9) a |

| Total attempted | 84.0 (1.1) | 83.3 (1.2) | 79.5 (1.4) a,b | 84.1 (1.7) | 81.0 (1.8) | 79.5 (2.0) a |

| Rapid Information Processing Task | ||||||

| Number of misses | 50.1 (2.5) | 47.6 (2.6) | 63.6 (3.2) a,b | 70.7 (3.6) | 70.9 (3.5) | 77.4 (3.7) |

indicates a significant difference from placebo, and

indicates a significant difference between 5 and 10 mg/70 kg morphine.

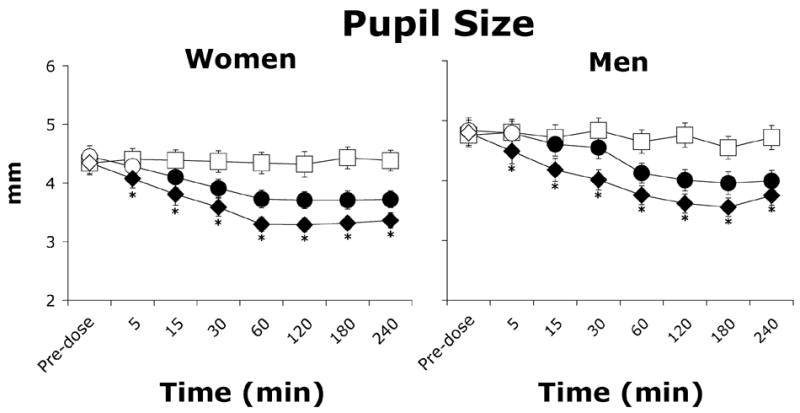

Physiological Effects

Morphine dose-dependently decreased pupil diameter in both women and men (Figure 6, p≤0.0001). In women, morphine dose-dependently decreased heart rate from 69 to 67 beats per minute (data not shown; F(2,18)=6.2, p≤0.01) and oxygen saturation from 98.4% to 98.0% after administration of placebo and 10 mg/70 kg morphine, respectively (data not shown; F(2,18)=13.4, p≤0.001), effects that were not observed in men. Morphine had a greater effect on oxygen saturation in women (Sex × Dose: F(2,112)=6.6, p≤0.01). Men (120 mm Hg) exhibited overall higher systolic blood pressure than women (113 mm Hg; Sex: F (1,16)=4.8, p≤0.05).

Figure 6.

Average pupil diameter (± one SEM) as a function of morphine dose and time after morphine administration in women (N=10) and men (N=8). Filled symbols indicate a significant difference from placebo. Asterisks represent a significant difference between 5 and 10 mg/70 kg morphine. Squares represent data collected during sessions involving administration of placebo, circles represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 5 mg/70 kg morphine, and diamonds represent data collected during sessions involving administration of 10 mg/70 kg morphine.

Plasma Morphine Levels

Plasma morphine levels (data not shown) dose-dependently increased in both women (F(1,9)=159.9, p≤0.0001) and men (F(1,7)=172.4, p≤0.0001). Average peak morphine levels were 26.6 and 61.7 ng/ml after administration of 5 and 10 mg/70 kg morphine, respectively. No difference in morphine plasma levels as a function of sex was detected.

DISCUSSION

Morphine produced different subjective mood effects, but similar analgesic effects in men and women, in this study using two nociceptive stimuli. This absence of a sex difference in analgesia is interesting in light of the substantial evidence for sex differences in opioid analgesia in rodents (Barrett, 2006). Although women were more sensitive to opioid-induced analgesia in some studies (Fillingim and Gear, 2004), these findings appear to depend upon the type of drug and pain models used. For instance, women were more sensitive than men to three opioid agonists in the CPT but not the MPT (Zacny, 2002). In other studies, the analgesic effects of morphine were similar in men and women, using heat, pressure, and ischemic pain tests (e.g., Fillingim et al., 2005). Although the results of the present study are consistent with Fillingim et al. (2005), they must be viewed with caution because of the small sample sizes in each group.

Although sensitivity to morphine’s analgesic effects did not differ between men and women in the present study, a robust difference in subjective ratings was observed. Women reported significantly greater negative effects after morphine administration compared to men, whereas men reported significantly greater positive drug effects. The current findings are consistent with previous reports demonstrating robust negative subjective ratings after opioid administration such as increased nausea and vomiting, and higher ratings of “sluggish feeling” and “dry mouth” in women (Zacny 2001, 2002; Zun et al., 2002; Cepeda et al., 2003; Fillingim et al., 2005; Bijur et al., 2008). The higher sensitivity to the subjective effects of morphine in women observed here are also consistent with the results of a previous study examining sex differences in response to experimentally induced pain as measured by positron emission tomography and [11C]-carfentanil (Zubieta et al., 2002). These investigators postulated that the higher regional (amygdala) concentrations of mu receptors in women could explain their greater sensitivity to the effects of mu opioids. It is possible that the robust negative effects of opiates in women contribute to their lower post-surgical opioid use, a finding that some have attributed to increased analgesic effects of opioids in women (Chia et al., 2002). It also should be noted that modest sex differences in subjective ratings of drug effects have been reported with cocaine (Kosten et al., 1993; Evans et al., 1999), tetrahydrocannabinol (Haney et al., 2007), nitrous oxide (Dohrn et al., 1992), and nicotine (Eissenberg, et al., 1999), suggesting that sex differences in subjective responses may be a common phenomenon that occurs across many drug classes. However, men and women do not appear to differ on measures of performance: Morphine impaired performance on all of the tasks, consistent with previous reports in rodents (Braida et al., 1994; Sala et al., 1994; Hepner et al, 2002), monkeys (Rupniak et al., 1991), and humans (Darke et al., 2000; Specka et al., 2000; Zacny and Gutierrez, 2003). Morphine altered several vital signs in the present study. Women exhibited a greater decrease in oxygen saturation after morphine administration, which is consistent with a previous report (Dahan et al., 1998). Furthermore, in the present study, the pressor effects during the CPT were greater in men, as reported previously by Fillingim and colleagues (2005). However, sex differences in morphine’s physiologic effects, although statistically significant, were small and most likely not clinically relevant.

The present study had several limitations. First, the participants were healthy volunteers, and several participants withdrew from the study, and thus it is not known whether these results would be generalizable to other populations. Second, the sample size was small, which limits the ability to interpret measures on which males and females did not differ. Fourth, we were not able to rule out the possibility of carry-over effects from repeated pain provocation and morphine administration, or the possibility of conditioned effects related to repeated testing. Finally, the men and women in this study differed in age, so this variable also may have affected our outcome measures.

In summary, the findings from the present study indicate that men and women differ in their mood responses to morphine, but may not differ in their sensitivity to the analgesic effects of morphine. This suggests that the two effects may be dissociable. Mood states have been shown to impact pain sensitivity, in some instances to a greater degree in women than men (Jones and Zachariae, 2002; Keogh et al., 2006; Garofalo et al., 2006), so it is conceivable that aversive subjective effects would also alter the analgesic effectiveness of a medication. Attention to the negative subjective effects reported in both men and women and the possible impact of such subjective effects on analgesia should be considered when determining therapeutic doses of morphine.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research for supporting this study (DE12763). The assistance of Michael Donovan RN, Elizabeth Adorno RN, Katherine Strutynski, Daniel Kroch, Anastasia Wermert, Kimberly Blauner, Irina Brouda, Christy Hall, Jose Mora, Mabel Torres, and Suleman Bhana is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Portions of this paper were presented at the 2005 Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, 2007 American Pain Society Meeting, and 2007 Behavioral Pharmacology Society Meeting.

DISCLOSURE/CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Barrett AC. Low efficacy opioids: implications for sex differences in opioid antinociception. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:1–11. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AC, Smith ES, Picker MJ. Sex-related differences in mechanical nociception and antinociception produced by mu- and kappa-opioid receptor agonists in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;452:163–73. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdine JH, Nesbit SA. Equianalgesic dosing of opioids. J Pain Palliative Pharmacother. 2006;20(4):79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braida D, Gori E, Sala M. Relationship between morphine and etonitazene-induced working memory impairment and analgesia. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;271:497–504. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90811-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijur PE, Esses D, Birnbaum A, Chang A, Schechter C, Gallagher EJ. Response to morphine in male and female patients: Analgesia and adverse events. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(3):192–198. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31815d3619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennum J, Kjeldsen M, Jensen K, Jensen TS. Measurements of human pressure-pain thresholds on fingers and toes. Pain. 1989;38:211–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda MS, Farrar JT, Baumgarten M, Boston R, Carr DB, Strom BL. Side effects of opioids during short-term administration: Effect of age, gender, and race. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:102–112. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Dworkin SF, Haug J, Gehrig J. Human pain responsivity in a tonic pain model: psychological determinants. Pain. 1989;37:143–60. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesterton LS, Barlas P, Foster NE, Baxter GD, Wright CC. Gender differences in pressure pain threshold in healthy humans. Pain. 2003;101:259–66. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia YY, Chow LH, Hung CC, Liu K, Ger LP, Wang PN. Gender and pain upon movement are associated with the requirements for postoperative patient-controlled iv analgesia: a prospective survey of 2,298 Chinese patients. Can J Anaesth. 2002;(3):249–55. doi: 10.1007/BF03020523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark WC, Dillon DJ. SDT analysis of binary decisions and sensory intensity ratings to noxious thermal stimuli. Perception and Psychophysics. 1973;13:491–493. [Google Scholar]

- Clark WC, Ferrer-Brechner T, Janal MN, Carroll JD, Yang JC. The dimensions of pain: a multidimensional scaling comparison of cancer patients and healthy volunteers. Pain. 1989;37:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Collins ED, MacArthur RB, Fischman MW. Comparison of intravenous and intranasal heroin self-administration by morphine-maintained humans. Psychopharmacology. 1999;143:327–38. doi: 10.1007/s002130050956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley KM, Toledano AY, Apelbaum JL, Zacny JP. Modulating effects of a cold water stimulus on opioid effects in volunteers. Psychopharmacology. 1997;131:313–20. doi: 10.1007/s002130050298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM. Sex differences in drug- and non-drug-induced analgesia. Life Sci. 2003;72:2675–88. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan A, Sarton E, Teppema L, Olievier C. Sex-related differences in the influence of morphine on ventilatory control in humans. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:903–13. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199804000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Sims J, McDonald S, Wickes W. Cognitive impairment among methadone maintenance patients. Addiction. 2000;95:687–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9556874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon KE, Thorn BE, Ward LC. An evaluation of sex differences in psychological and physiological responses to experimentally-induced pain: a path analytic description. Pain. 2004;112:188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrn CS, Lichtor JL, Finn RS, Uitvlugt A, Coalson DW, Rupani G, de Wit H, Zacny JP. Subjective and psychomotor effects of nitrous oxide in healthy volunteers. Behav Pharmacol. 1992;3:19–30. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199203010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA, Sullivan MJ, Fillingim RB. Catastrophizing as a mediator of sex differences in pain: differential effects for daily pain versus laboratory-induced pain. Pain. 2004;111:335–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T, Adams C, Riggins EC, 3rd, Likness M. Smokers’ sex and the effects of tobacco cigarettes: subject-rated and physiological measures. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1:317. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Haney M, Fischman MW, Foltin RW. Limited sex differences in response to “binge” smoked cocaine use in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:445–54. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, Gear RW. Sex differences in opioid analgesia: clinical and experimental findings. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:413–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, Ness TJ, Glover TL, Campbell CM, Hastie BA, Price DD, Staud R. Morphine responses and experimental pain: sex differences in side effects and cardiovascular responses but not analgesia. J Pain. 2005;6:116–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser HF, Van Horn GD, Martin WR, Wolbach AB, Isbell H. Methods for evaluating addiction liability. (A) “Attitude” of opiate addicts toward opiate-like drugs, (B) A short-term “direct” addiction test. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1961;133:371–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo JP, Lawler C, Robinson R, Morgan M, Kenworthy-Heinige T. The role of mood states underlying sex differences in the perception and tolerance of pain. Pain Pract. 2006;6:186–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2006.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gear RW, Gordon NC, Heller PH, Paul S, Miaskowski C, Levine JD. Gender difference in analgesic response to the kappa-opioid pentazocine. Neurosci Lett. 1996;205:207–9. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12402-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gear RW, Gordon NC, Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Heller PH, Levine JD. Dose ratio is important in maximizing naloxone enhancement of nalbuphine analgesia in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2003;351:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00939-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gear RW, Miaskowski C, Gordon NC, Paul SM, Heller PH, Levine J. The kappa opioid nalbuphine produces gender- and dose-dependent analgesia and antianalgesia in patients with postoperative pain. Pain. 1999;83:339–45. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil KM, Wilson JJ, Edens JL, Webster DA, Abrams MA, Orringer E, Grant M, Clark WC, Janal MN. Effects of cognitive coping skills training on coping strategies and experimental pain sensitivity in African American adults with sickle cell disease. Health Psychol. 1996;15:3–10. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon NC, Gear RW, Heller PH, Paul S, Miaskowski C, Levine JD. Enhancement of morphine analgesia by the GABAB agonist baclofen. Neuroscience. 1995;69:345–9. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00335-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M. Opioid antagonism of cannabinoid effects: differences between marijuana smokers and nonmarijuana smokers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(6):1391–403. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström B, Lundberg U. Pain perception to the cold pressor test during the menstrual cycle in relation to estrogen levels and a comparison with men. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 2000;35:132–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02688772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepner IJ, Homewood J, Taylor AJ. Methadone disrupts performance on the working memory version of the Morris water task. Physiol Behav. 2002;76:41–9. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, Spindler H, Jørgensen MM, Zachariae R. The effect of situation-evoked anxiety and gender on pain report using the cold pressor test. Scand J Psychol. 2002;43(4):307–13. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, Zachariae R. Gender, anxiety, and experimental pain sensitivity: an overview. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2002;57:91–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh E, Bond FW, Flaxman PE. Improving academic performance and mental health through a stress management intervention: outcomes and mediators of change. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:339–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Gawin FH, Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ. Gender differences in cocaine use and treatment response. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1993;10:63–6. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90100-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk WJ, Evans SM, Bisaga AM, Sullivan MA, Comer SD. Sex differences and hormonal influences on response to cold pressor pain in humans. J Pain. 2006;7:151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk WJ, Evans SM, Bisaga AM, Sullivan MA, Comer SD. Sex differences and hormonal influences on response to mechanical pressure pain in humans. J Pain. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.08.004. under revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery D, Fillingim RB, Wright RA. Sex differences and incentive effects on perceptual and cardiovascular responses to cold pressor pain. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:284–91. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000033127.11561.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WR, Fraser HF. A comparative study of physiological and subjective effects of heroin and morphine administered intravenously in postaddicts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1961;133:388–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNicol D. A primer of signal detection theory. London: George Allen & Unwin; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30:191–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell LA, MacDonald RA, Brodie EE. Temperature and the cold pressor test. J Pain. 2004;5:233–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Mello NK. Opioid antinociception in ovariectomized monkeys: comparison with antinociception in males and effects of estradiol replacement. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:1132–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsen E, Romberg R, Bijl H, Mooren R, Engbers F, Kest B, Dahan A. Alfentanil and placebo analgesia: no sex differences detected in models of experimental pain. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(1):130–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200507000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, 3rd, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Myers CD, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in the perception of noxious experimental stimuli: a meta-analysis. Pain. 1998;74:181–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupniak NM, Samson NA, Steventon MJ, Iversen SD. Induction of cognitive impairment by scopolamine and noncholinergic agents in rhesus monkeys. Life Sci. 1991;48:893–9. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90036-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala M, Braida D, Leone MP, Calcaterra P, Frattola D, Gori E. Chronic morphine affects working memory during treatment and withdrawal in rats: possible residual long-term impairment. Behav Pharmacol. 1994;5:570–580. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarton E, Olofsen E, Romberg R, den Hartigh J, Kest B, Nieuwenhuijs D, Burm A, Teppema L, Dahan A. Sex differences in morphine analgesia: an experimental study in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1245–54. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200011000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specka M, Finkbeiner T, Lodemann E, Leifert K, Kluwig J, Gastpar M. Cognitive-motor performance of methadone-maintained patients. Eur Addict Res. 2000;6:8–19. doi: 10.1159/000019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel EC, Ulibarri CM, Folk JE, Rice KC, Craft RM. Gonadal hormone modulation of mu, kappa, and delta opioid antinociception in male and female rats. J Pain. 2005;6:261–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terner JM, Lomas LM, Smith ES, Barrett AC, Picker MJ. Pharmacogenetic analysis of sex differences in opioid antinociception in rats. Pain. 2003;106:381–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn BE, Clements KL, Ward LC, Dixon KE, Kersh BC, Boothby JL, Chaplin WF. Personality factors in the explanation of sex differences in pain catastrophizing and response to experimental pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:275–82. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200409000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DJ, Zacny JP. Subjective, psychomotor, and analgesic effects of oral codeine and morphine in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacol. 1998;140:191–201. doi: 10.1007/s002130050757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP. Morphine responses in humans: a retrospective analysis of sex differences. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63:23–8. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP. Gender differences in opioid analgesia in human volunteers: cold pressor and mechanical pain. NIDA Res Monogr. 2002;182:22–3. [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP, Beckman NJ. The effects of a cold-water stimulus on butorphanol effects in males and females. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;78:653–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP, Gutierrez S. Characterizing the subjective, psychomotor, and physiological effects of oral oxycodone in non-drug-abusing volunteers. Psychopharmacology. 2003;70:242–54. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta J-K, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu Y, Kilbourn MR, Jewett DM, Meyer CR, Koeppe RA, Stohler CS. μ-opioid receptor-mediated antinociceptive responses differ in men and women. J Neurosci. 2002;22(12):5100–5107. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05100.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zun LS, Downey LV, Gossman W, Rosenbaum J, Sussman G. Gender differences in narcotic-induced emesis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:151–154. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2002.32631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]