Abstract

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics is playing an increasingly important role in cardiovascular research. Proteomics includes not only identification and quantification of proteins, but also the characterization of protein modifications such as post-translational modifications and sequence variants. The conventional bottom-up approach, involving proteolytic digestion of proteins into small peptides prior to MS analysis, is routinely used for protein identification and quantification with high throughput and automation. Nevertheless, it has limitations in the analysis of protein modifications mainly due to the partial sequence coverage and loss of connections among modifications on disparate portions of a protein. An alternative approach, top-down MS, has emerged as a powerful tool for the analysis of protein modifications. The top-down approach analyzes whole proteins directly, providing a “bird’s eye” view of all existing modifications. Subsequently, each modified protein form can be isolated and fragmented in the mass spectrometer to locate the modification site. The incorporation of the non-ergodic dissociation methods such as electron capture dissociation (ECD) greatly enhances the top-down capabilities. ECD is especially useful for mapping labile post-translational modifications which are well-preserved during the ECD fragmentation process. Top-down MS with ECD has been successfully applied to cardiovascular research with the unique advantages in unraveling the molecular complexity, quantifying modified protein forms, complete mapping of modifications with full sequence coverage, discovering unexpected modifications, and identifying and quantifying positional isomers and determining the order of multiple modifications. Nevertheless, top-down MS still needs to overcome some technical challenges to realize its full potential. Herein, we reviewed the advantages and challenges of top-down methodology with a focus on its application in cardiovascular research.

Keywords: Cardiovascular diseases, Proteomics, Electron Capture dissociation, Post-translational modification, Top-Down Mass Spectrometry

Introduction

Proteomics is playing an increasingly important role in cardiovascular research (see reviews1–8). Proteomics includes not only the separation, identification and quantification of proteins, but also the characterization of protein modifications such as post-translational modification (PTMs) and sequence variants (e.g. mutants, alternatively spliced isoforms, and amino acid polymorphism).9–10 PTMs (e.g. phosphorylation, glycosylation, acetylation, proteolysis) are covalent modifications of a protein after its translation. PTMs can modulate the activity, stability, and function of a protein.11 Disease-induced PTMs can occur in concert with altered gene expression, which will substantially affect protein function and its interaction with other proteins in the signaling network.1 Aberrant protein PTMs together with mutations and alternatively spliced isoforms are increasingly recognized as important underlying mechanisms for cardiovascular diseases.12–14 Hence, a comprehensive analysis of protein modifications is of high importance for understanding the disease mechanisms.

Traditional strategies for analysis of protein modifications, such as radioactive labeling and Western blotting, can be specific and relatively quantitative, but they require prior knowledge of the modification type and are limited by antibody availability and specificity. The recently developed Pro-Q diamond staining can globally reveal the level of protein phosphorylation, but cannot provide the identification of proteins or their modification sites which are essential for understanding the disease mechanisms.15–16 Biological mass spectrometry (MS) is the preferred method for the analysis of protein modifications since it is capable of not only providing universal information about protein modifications without a priori knowledge but also locating the sites of modification.11

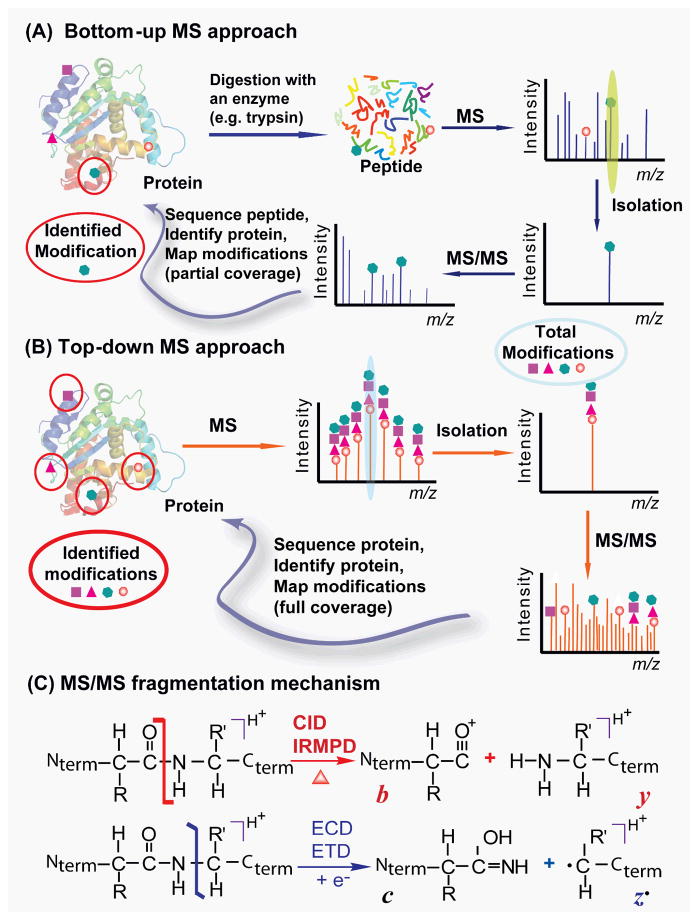

Currently, there are two complementary approaches in MS-based proteomics: “bottom-up” and “top-down”.17–20 The conventional peptide-based “bottom-up” shotgun proteomics involves in gel or in solution proteolytic digestion of proteins with enzymes, usually trypsin, into many pieces of small peptides (1–3 kDa) prior to MS analysis (Fig. 1A). This approach is well-suited for protein identification which only requires a very small portion of sequence coverage (~10–20 amino acid residues) to identify the protein from the database.21 With the tremendous efforts dedicated to the development of hardware and software in the past decade, bottom-up shotgun proteomics currently serves as a workhorse in modern proteomics with high throughput and automation. Nevertheless, the bottom-up approach has intrinsic limitations in characterizing protein modifications since only a small and variable fraction of peptides is recovered from digestion resulting in low percentage coverage of the protein sequence. In other words, even if one identifies all modifications present in the recovered peptides, the modification status of the unrecovered sequence portion remains unknown. In addition, the connection between modifications on disparate portions of a protein can be lost since the typical peptides from tryptic digestion contain only ~5–20 amino acids.17 Furthermore, since each protein is digested into many small peptide components, the overall complexity of the sample is increased.

Fig. 1. Top-down (A) vs. bottom-up (B) for protein PTM characterization.

(A) In bottom-up MS, a protein is typically digested with an enzyme (i.e. trypsin) into many small peptides either in gel or in solution. The recovered peptides will be detected by MS and a specific peptide can be isolated and fragmented by MS/MS to identify the protein from the database. Modifications can be mapped in the recovered peptides but many peptides remain uncovered and undetected by MS resulting in partial sequence coverage. (B) In top-down MS, the whole protein is analyzed directly in the mass spectrometer without digestion so the full information of the modification state can be revealed. A specific protein form can be isolated and fragmented by MS/MS to locate the modification sites. All modifications can be identified with full sequence coverage. (C) MS/MS fragmentation mechanism. The energetic dissociation methods (i.e. CID/IRMPD) cleave CO-NH bonds producing b and y fragment ions. The non-ergodic methods (i.e. ECD/ETD) cleave NH-CHR bonds producing mainly c and z• ions. Nterm and Cterm stand for N- and C-termini of a protein, respectively.

Top-down MS is becoming a powerful technology for comprehensive analysis of protein modifications.22–33 In contrast to bottom-up MS, top-down MS analyzes intact proteins without proteolytic digestion (Fig. 1B). This strategy preserves the labile structural characteristics which are mostly destroyed in bottom-up MS.32 It can universally detect all the existing modifications including PTMs (i.e. phosphorylation, proteolysis, acetylation) and sequence variants (i.e. mutants, alternatively spliced isoforms, amino acid polymorphisms) simultaneously in one spectrum (a “bird’s eye” view) without a priori knowledge.32 Top-down MS first measures the molecular weight (MW) of an intact protein and compares it with the calculated value based on the DNA-predicted protein sequence which can easily reveal any changes/modifications in the protein sequence globally (the “top” part). Then a specific modified form of interest can be directly isolated in the mass spectrometer (“a gas-phase purification”) and subsequently fragmented in the mass spectrometer by tandem MS (MS/MS) such as collision-induced dissociation (CID) and electron capture dissociation (ECD) for highly reliable mapping of the modification sites (the “down” part).10, 32 The incorporation of the novel MS/MS technique, ECD,34 has greatly enhanced the capability of top-down MS in structural analysis of biomolecules (see review35). As a non-ergodic fragmentation method,34 ECD preserves labile PTMs during the fragmentation process thus it is particularly suitable for the localization of labile PTMs.25–26 Top-down MS with ECD has been successfully applied to cardiovascular research with the unique advantages in unraveling the molecular complexity, quantifying multiple modified protein forms, complete mapping of modifications with full sequence coverage, discovering unexpected PTMs and amino acid polymorphisms, and identifying and quantifying positional isomers and determining the order of multiple modifications.25–30

In contrast to the well-established bottom-up proteomics, the top-down proteomics is still in its early developmental stage and yet to fully overcome its technical challenges in sample preparation, instrument sensitivity/detection limit, and throughput/automation.32, 36–39 New technological developments are needed to advance top-down proteomics for the analysis of complex samples of cell/tissue lysate and biological fluid. Herein, we provide an overview on the top-down MS methodology, the basic information needed for top-down MS analysis, and its advantages and technical challenges, with a focus on its application in cardiovascular disease.

Top-down MS-based Proteomics Methodology

Sample preparation for top-down MS

Typically, intact proteins need to be extracted from cell/tissue lysate, solubilized and separated/purified prior to MS analysis. Protein samples then need to be introduced to a mass spectrometer in buffer conditions compatible with MS analysis. Typical buffers used to extract/solubilize proteins involve high salt concentration usually with the addition of detergents such as sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to increase the solubility of the protein. These salts and detergents interfere with MS detection of proteins because they are present in huge excess relative to proteins and have much higher ionization efficiency, which will therefore suppress protein signals.

The high salt content can be easily removed by a desalting step using a reverse phase column/trap either on-line or off-line prior to MS analysis. Alternatively, MS-compatible volatile salt buffers such as ammonia bicarbonate and ammonia acetate can also be used to replace the common salt present in biological samples (i.e. NaCl, KCl, CaCl2) via a buffer exchange step such as dialysis or ultra-filtration. Typical procedures for detergent removal involve precipitation and resolubilization of proteins in detergent-free buffers, which may result in sample loss since some portion of protein may become insoluble in detergent-free buffers. Recently there are efforts allocated in designing MS-compatible acid labile detergents with the hope of replacing these traditional detergents.40,41 Alternatively, proteins can also be selectively solubilized based on their inherent chemical properties such as biospecificity, hydrophobicity and charge without the use of detergent.1 This can also be used to fractionate specific subproteome prior to chromatographic separation.

Separation/purification of intact proteins

A complex protein mixture can be separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), liquid chromatography (LC) as well as the high resolution mass spectrometry. One dimensional (1D) and 2D SDS-PAGE are the classical methods for protein separation and visualization.1, 42–44 The gel-based separation is widely used in bottom-up proteomics since trypsin digested peptides can be effectively retrieved from gels.37, 39 However it is technically challenging to extract the intact proteins from gel matrixes with a high recovery rate.45 Thus gel-based separation is not applicable in top-down MS. Recently, a solution-based isoelectric focusing coupled with a multiplex tube gel electrophoresis separation device referred to as gel-eluted liquid fraction entrapment electrophoresis (GELFrEE)46 has been developed for intact protein separation based on their MWs and applied to proteins (10–250 kDa) with high resolution and high recovery rate.24, 37, 47 Nevertheless, the surfactant SDS is still present in the sample so the proteins need to be precipitated in organic solvent and resolubilized in MS-compatible buffers.

LC is ideally suited for proteomics since it can be conveniently interfaced with MS (see reviews20, 48–49). The major LC techniques typically used for intact protein separation include affinity, ion exchange chromatography (IEC), size exclusion chromatography (SEC), and reverse-phase (RP) chromatography.48 Affinity chromatography is by far the most effective and specific protein purification method.50 For example, immunoaffinity methods have been utilized to effectively purify cardiac troponin I (cTnI) from animal and human myocardium.15, 25, 27, 30, 42 Nonetheless, most of the affinity methods have been performed offline, requiring an additional separation/desalting procedure using RPLC. IEC and SEC have also been employed for intact protein separation.48, 51–53 Generally, they are used to carry out the first dimension separation followed by RP chromatography in the second dimension. RP chromatography not only enhances the separation from the previous step but also performs desalting as the last sample preparation step before MS analysis.52–53 The 2DLC approach has the advantage of preconcentrating and desalting the species of interest simultaneously, yielding higher peak capacity and better separation, and, if connected on-line, minimizing sample loss. Chromatographic focusing, as a promising alternative to salt gradient IEC, is also capable of separating intact proteins.37 Van Eyk and co-workers reported the separation of intact proteins from human serum proteome with the use of chromatographic focusing and RPLC in a commercial ProteomeLab PF2D system.54

With high resolution mass spectrometers e.g. Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FTICR) MS (see review55), protein mixtures with high complexity may be resolved during MS analysis in addition to other traditional separation techniques. It has been demonstrated that over 100 protein components from a crude cell lysate were successfully separated in one FTICR MS spectrum using the high resolving power of FTICR.23

Top-down MS instrumentation

A typical mass spectrometer consists of four components: 1) sample inlet, 2) ion source which converts sample molecules to ions such as electrospray ionization (ESI) and matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI), 3) mass analyzer, and 4) detector (see reviews20, 37, 56). Top-down MS is usually performed in high resolution instruments due to the need to resolve the high MW of intact proteins.32, 55 The early top-down MS studies were done in home-built FTICR mass spectrometers with high resolution and accuracy.22–23 Recently, the development of a number of commercial high resolution hybrid mass spectrometers such as LTQ/FT, LTQ-orbitrap (a hybrid between ion trap and FT), and quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-TOF) substantially boosted the growth of top-down MS applications.39 ESI is preferred over MALDI in top-down proteomics since it produces multiply-charged precursor ions for more efficient dissociation of large protein ions and provides more MS/MS options than MALDI which mainly produces singly-charged species.57 The inability to resolve the large MW ions substantially limits the practice of top-down MS in low resolution instruments.

Fragmentation methods for protein molecular ions

Generally, there are two categories of fragmentation methods: energetic vs. non-ergodic (Fig. 1C). 10, 32, 39 The well-developed energetic dissociation methods such as CID, infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD) and post-source decay (PSD), cleave CO-NH backbone bonds to produce b and y fragment ions at very high efficiency. All these energetic dissociation methods preferably dissociate bonds of the lowest activation energy. Since energy levels of the labile PTMs such as phosphorylation bonds are weaker than the backbone amide bonds, they are usually cleaved first in the energetic dissociation methods, resulting in the neutral loss of phosphoric acid (H3PO4, 98 Da) or metaphosphoric acid (HPO3, 80 Da), which makes it difficult to map phosphorylation sites.

The non-ergodic electron-based MS/MS techniques, ECD34 and electron transfer dissociation (ETD),58 are particularly suitable for the localization of labile PTMs like phosphorylation.25–26, 30, 35 In ECD, low energy thermal electrons are captured by a protonated peptide or protein causing local fast (<10−12 s) cleavages of backbone covalent bonds, NH-CHR, producing mainly c and z• ions (Fig. 1C).34 Hence the labile PTMs are well-preserved in the ECD fragmentation process and no loss of labile phosphate has been observed in ECD spectra.25–26, 30 ECD is non-selective so that it often provides far more cleavages than CID,23 which greatly enhances the capability of top-down MS in identifying PTMs and sequence variants.23, 25, 27, 29–30,59 Nevertheless, ECD is only available at high-end FTICR instruments, which substantially limits its wide use in proteomic laboratories. More recently, ETD,58 a sister-version of ECD, in which the electrons are delivered by an anion that transfers its electron to a multiply-charged peptide or protein, has been implemented in hybrid LTQ/orbitrap instruments,60 which begins to play a role in top-down proteomics.61

Top-down MS data analysis tools

Since ESI, the commonly used ionization method in top-down MS, produces multiply-charged ions, Horn et al. first developed a fully automated computer algorithm, THRASH, to determine the charge states and subsequently the MWs of precursor and product ions from complex high resolution mass spectra.62 Unfortunately, this software is not compatible with the mainstream computers. Smith’s lab developed free downloadable PC and Mac compatible software (http://omics.pnl.gov/software), DeconMSn and Decon2LS, based on THRASH algorithm. Thermo has also developed the ManualXtract algorithm to process high resolution data of multiply-charged ions from ESI.

Furthermore, bioinformatics tools for identification of proteins using top-down MS are also currently available. There are three major search engines: ProSight, PIITA, and MascotTD (also known as “big Mascot”) (for reviews, see37–38). ProSight, developed by Kelleher group, is the first and most flexible search engine for top-down proteomics.63 It allows the identification of proteins from complex mixtures by searching both the precursor ion MS and product ion MS/MS data (processed via THRASH algorithm) in the databases. ProSight can be used to map both known and unknown PTMs.37 PIITA is based on precursor ion independent top-down algorithm using fragmentation data without a priori expectation of PTMs or sequence errors.64 A recently released big Mascot extended the classical Mascot to large proteins (>16 kDa). Big Mascot search requires both precursor and fragment ions and can identify protein PTMs and sequence variants.65

Application of Top-down MS to Cardiovascular Research

Unraveling molecular complexity of intact proteins by high resolution MS

The major advantage of top-down MS is that it can easily reveal the full extent of molecular complexity of a protein since it analyzes whole proteins instead of small peptides.32 The presence of PTMs can be detected by the mass difference (Δm) between unmodified and modified forms (See review11). Moreover, most of the common amino acids have distinct mass (except Leu, Ile) so that the top-down approach can also be used to reveal sequence variations resulting from proteolytic degradation, mutation, amino acid polymorphism, and alternatively spliced isoform.

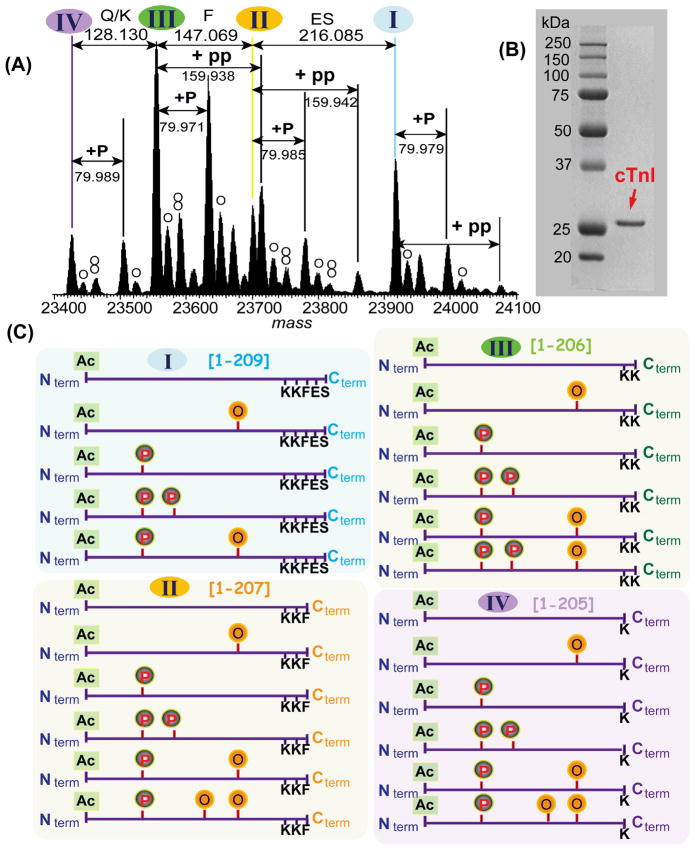

We have recently employed the high resolving power of FTICR MS to unravel the complexity of PTMs for a commercially available cTnI sample said purified from healthy human heart tissues (Fig. 2).28 cTnI is the inhibitory subunit of the thin filament troponin-tropomyosin regulatory complex, playing a critical role in Ca2+-mediated cardiac muscle contractility.66–67 ESI/FTMS spectrum of cTnI revealed a total of thirty-six modified molecular ions (Fig. 2A) despite the protein running as a single sharp band on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2B). The accurate mass measurements of all the well resolved cTnI forms suggest several mass differences (Δm) (Fig. 2A). For example, Δm of +79.971 Da matches with phosphorylation (Calc’d: 79.966 Da) andΔm of +15.996 Da is commonly assigned as oxidations (Calc’d: 15.995 Da) of the proteins. Moreover,Δm values of 128.130, 147.069, and 216.085 Da correspond to amino acids Q/K (Calc’d: Q, 128.059 Da; K, 128.095 Da), F (Calc’d, 147.068 Da), and ES (Calc’d, 216.075 Da) respectively, which were resulted from truncations of Glu-Ser, Phe-Glu-Ser and Lys-Phe-Glu-Ser residues from the C-terminus of a full-length cTnI. The high mass accuracy afforded by high resolution MS data greatly increased the confidence in assigning the protein modification. All forms detected here matched with the predicted sequence (TNNI3_human) obtained from Swissprot database with the removal of N-terminal Met and the addition of acetylation at the new N-terminus. Thus, we find acetylation, N-terminal Met removal, mono- and bis-phosphorylation, oxidation, and proteolytic degradation for this commercially available cTnI.28 The major modified forms of cTnI, resulting from the combinations of these multiple modifications, were illustrated in Fig. 2C. Such a high level of molecular complexity cannot be accounted for by any other technique.

Fig. 2. Top-down MS for unraveling molecular complexity of commercially available human cTnI.

(A) Deconvoluted high resolution ESI/MS spectrum (m/z is converted to mass) of multiply charged intact cTnI molecular ions revealed a total of thirty-six modified forms resulting from acetylation, phosphorylation and C-terminal proteolytic truncations. Roman numerals indicate the full-length (I) and three different C-terminal truncated forms of cTnI (II, III, IV), respectively. +80 Da and +160 Da correspond to mono- and bis-phosphorylation (+P, +PP), respectively. Oxidized species (+16 Da) are indicated by “O”. (B). 1-D SDS PAGE analysis of human cTnI stained with Coomassie Blue. (C) Schematic representation of the major modified forms of human cTnI detected in (A) with a combinatorial modifications of one acetylation (Ac-), one or two phosphorylation (P) sites, one or two oxidation (O) sites, and three possible C-terminal proteolytic truncations. Nterm and Cterm stand for N- and C-termini of cTnI, respectively. Modified based on Ref.28 with permission.

Complete PTM mapping by MS/MS

Top-down MS not only can reveal the molecular complexity but also precisely map sites of modifications by isolating and fragmenting the modified protein ions in the mass spectrometer.10,68 MS/MS produces b/y or c/z• fragment ions with b/c ions counting from the N-terminus and y/z• ions from the C-terminus (Fig. 1C). In a top-down MS/MS experiment, full sequence coverage can be easily achieved for a protein less than 60 kDa.25, 27, 29–30, 68 We have utilized top-down MS with ECD for the comprehensive mapping of all present modifications in mouse, rat, pig, and primate cTnI.25, 27, 29–30 In the case of mouse cTnI, high resolution ESI/MS revealed the coexistence of un-, mono-, and bis-phosphorylated forms, together with minor N-terminal proteolytic fragments.25 The subsequent MS/MS of individually isolated un-, mono-, and bis-phosphorylation forms generated extensive fragmentation ions including complementary pairs which covered the entire sequence (e.g. for a 210 amino acid mouse cTnI, c134/z•166 is a complementary pair resulting from the cleavage of the same bond between amino acid 134 and 135. c134 covers the first 134 amino acids from the N-terminus and z•166 covers the last 166 amino acids for the C-terminus). All the MS/MS data unambiguously identified Ser22/23, the bona fide sites for protein kinase A (PKA), as the only phosphorylation sites in cTnI immunoaffinity purified from healthy wild-type mouse hearts, consistent with our other studies of rat, pig and primate cTnI.27, 29–30 Furthermore, high resolution MS and Pro-Q diamond gel analysis consistently showed the lack of phosphorylation in transgenic mouse cTnI (cTnI-Ala2) where Ser22/23 in cTnI had been rendered non-phosphorylatable by mutations to Alanine.25 This data confirmed that top-down MS mapped all phosphorylation sites in mouse cTnI. However, cTnI is also well-known to be phosphorylated by protein kinase C (PKC) at Ser43/45 and Thr144 (mouse sequence counting the N-terminal Met). So the question is whether these PKC sites, mainly identified via in vitro phosphorylation assays, are fact or fancy.69 It is possible that in the healthy mouse hearts the phosphorylation occupancy (<1%) of these PKC sites are below the limit of detection at current stage of the top-down methodology development.25 More importantly, since we have only analyzed the basal phosphorylation state in healthy animals, the phosphorylation of the PKC sites in cTnI might be related to cardiac dysfunction.67 The transgenic mouse lines that over-expressed PKC in the myocardium exhibit a steady progression to heart failure70–71 and partial replacement of cTnI with a non-phosphorylatable mutant at Ser43/45 attenuates the contractile dysfunction suggesting that PKC sites Ser43/45 may contribute to the progression of failure.72 Indeed our recent study has precisely identified PKC sites of Ser43/45 in cTnI affinity purified from spontaneously hypertensive heart failure rat (Dong X., et al. unpublished data).

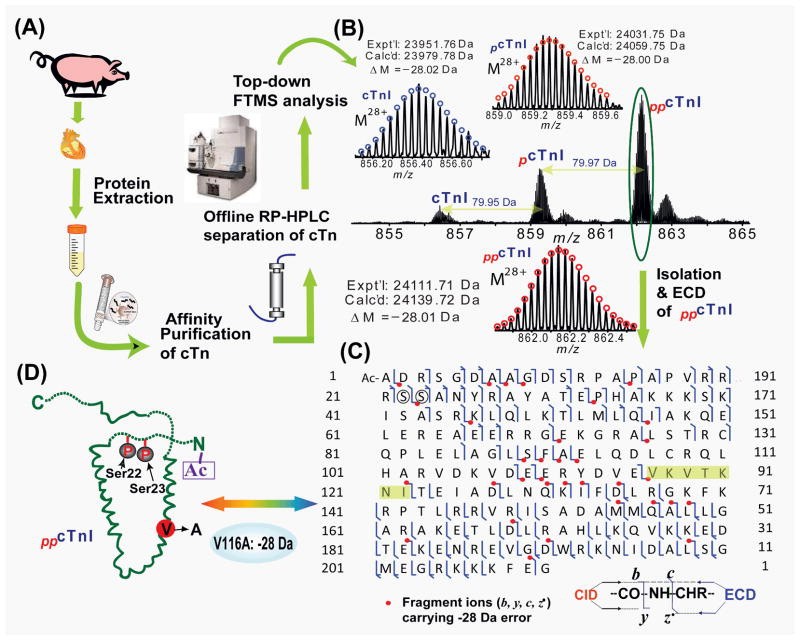

Discovery of the unexpected modifications

Top-down MS is also able to discover unexpected PTMs or amino acid polymorphisms (a.k.a. protein-sequence polymorphisms).27, 29, 68, 73 Typically, the first step in top-down MS approach is to compare the experimental MW with that predicted from DNA sequence. The “incorrect” MW could immediately caution that there might be sequence discrepancy (“error”) present in the protein sequence. Then the precursor ion containing the “error” will be isolated and fragmented to locate the precise “error” position. For example, Zhang et al. effectively localized an unexpected single amino acid polymorphism, V116A in addition to phosphorylation, acetylation, and removal of N-terminal Met for swine cTnI (Fig. 3)29 which was extracted, immunoaffinity enriched from the left ventricle of domestic pig myocardium, and separated and desalted using off-line RPLC prior to MS analysis (Fig. 3A). The high resolution MS analysis revealed three major MW forms corresponding to un-, mono-, and bis-phosphorylated swine cTnI. Surprisingly, all three cTnI forms contained an “error” of Δm = −28 Da from the predicted value (Fig. 3B). The bis-phosphorylated cTnI was individually isolated and fragmented by CID and ECD. It was found that all fragment ions containing the first 115 amino acids from the N-terminus, as well as the fragment ions containing the first 88 amino acids from the C-terminus, were “error”-free, which essentially narrow the “error” down to the 7 amino acid region after the first 115 and before the last 88 amino acids, V116-I122 (VKVTKNI) (Fig. 3C). The only possibility to account for the −28 Da mass discrepancy is the replacement of valine for alanine (V->A) and most likely to be V116A based on the sequence homology alignment (Fig. 3D). We assigned it as amino acid polymorphism instead of mutation since the latter typically is associated with pathology while healthy pig heart tissue was used in this study. Amino acid polymorphism of Ala/Ser at residue 7 and the addition of Gln (Q) at residue 192 were also identified for rat cTnI and cardiac troponin T(cTnT).27

Fig. 3. Top-down MS for discovery of unexpected modifications.

(A) The workflow of extraction and purification of cTn from domestic swine hearts for MS analysis. (B) FTMS spectrum of swine cTnI for the charge state 28+ precursor ions, showing its distribution in un-, mono- and bis-phosphorylated forms. Insets: isotopically resolved molecular ions of un-, mono-, and bis-phosphorylated cTnI (M28+) with high accuracy molecular weight measurements. pcTnI and ppcTnI represent mono-(+79.95 Da) and bis-phosphorylated (+159.92 Da) cTnI, respectively. Circles represent the theoretical isotopic abundance distribution of the isotopomer peaks corresponding to the assigned mass. Calc’d, calculated most abundant mass; Expt’l, experimental most abundant mass. (C) MS/MS fragmentation and product ion map from ECD and CID spectra for bis-phosphorylated swine cTnI (ppcTnI). Bis-phosphorylated cTnI was isolated and fragmented by ECD. Fragments assignments were made to the swine cTnI (UnitProtKB/Swiss-Prot A5X5T5, TNNI3_pig) with the removal of N-terminal Met and acetylation at the new terminus. Bis-phosphorylation sites of Ser22/23 were highlighted by circles. The fragmentation ions carrying the mass discrepancy (−28 Da) was indicated in dots. The potential amino acids containing the mass discrepancy (−28 Da) were highlighted in shades. (D) Schematic representation of all identified modifications for bis-phosphorylated swine cTnI. Modified based on Ref.29 with permission.

There are occasions even if the measured MW matches exactly with the predicted value; errors still exist in the sequence. A remarkable example is reported by Sze et al. where the comprehensive top-down MS sequencing of a 29 kDa protein, carbonic anhydrase was accomplished.74 A total of 250 of the 258 interresidue bonds were extensively cleaved which essentially can define any modifications to within one residue. It was suggested that there are two “errors” in the first 10–31 amino acid region: Asp10 should be Asn10 and Asn31 should be Asp31.74 Top-down MS has also been employed to discover unexpected PTMs such as an unexpected automethylation event.68

Quantification of modified protein levels

Protein quantification is becoming an increasingly important subject in MS-based proteomics.75–76 The top-down MS approach is especially attractive for quantification of the relative abundance of modified protein species, since the effect of the modifying groups on the physico-chemical properties of the intact proteins in the top-down approach is much less compared with that of the peptides in the bottom-up approach.24, 28, 77 Muddiman and co-workers demonstrated a quantitative relationship between the concentration ratios of two proteins which are 97% identical and their ESI/FTMS peak ratios as well as a linear relationship between the protein concentration and the FTMS peak intensity over ~1.5 orders of magnitude.78 Kelleher group has developed a method called protein ion relative ratio (PIRR) where the relative ratio of MS signal intensity values were used to calculate the relative amount of modified protein forms77 and applied it to the global assessment of the combinatorial PTMs of core histones79 and histone H4.80 Our group has modified such a PIRR method and quantitatively determined the phosphorylation levels in human, mouse, rat, swine, and primate cTnI25, 28–30 as well as recombinant mouse cardiac myosin binding protein C (cMyBP-C).26

Wannders et al. extended the stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) methodology to intact proteins for the quantification of their relative expression levels and the degrees of modification between different samples.81 More recently, Collier et al. reported the quantitative top-down proteomics of SILAC labeled human embryonic stem cells.82

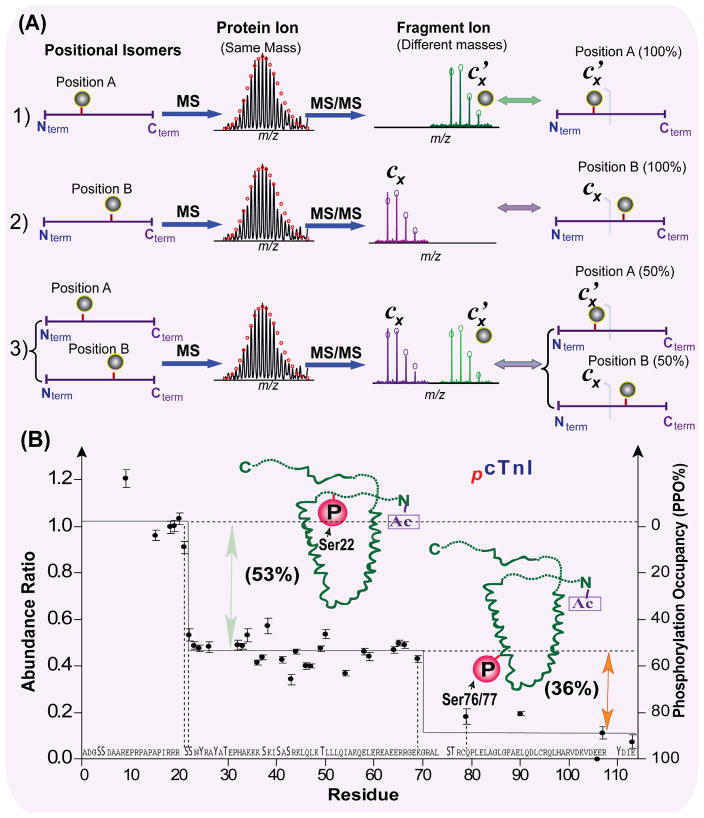

Identification and quantification of modified positional isomers

Top-down MS also appears to be uniquely advantageous for identification and quantification of modified positional isomers which are results from the occurrence of the same modification group at a different location (i.e. position A vs. B). How top-down MS can be used to identify positional isomers is illustrated in Fig. 4A. In a hypothetical example of positional isomers, all three cases (case 1 of proteins carrying the modification entirely at position A, case 2 of proteins carrying the same modification entirely at position B, and case 3 of a mixture of proteins with modification at either position A or B) showed the identical molecular ion spectra (Fig. 4A). The subsequent MS/MS can generate different product ion spectra for fragments with bond cleavages between position A and B (e.g. hypothetical fragments Cx’ with modification and Cx without modification), which distinguishes the positional isomers in all three cases (Fig. 4A). We have identified positional isomers for mono-phosphorylated human cTnI.28 ECD data suggested two possible sites for the mono-phosphorylation: the well known PKA site Ser22 and a novel site at Ser76/Thr77 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Top-down MS for identification and quantification of positional isomers.

(A) Schematic representation of positional isomers determined by top-down MS. The MS spectra of hypothetical positional isomers: 1) protein modified entirely at position A, 2) protein modified entirely at position B, and 3) a mixture of proteins modified at position A and modified at position B yield identical mass. The subsequent MS/MS spectra of these positional isomers with bond cleavages between position A and B (e.g. hypothetical fragments Cx’ with modification and Cx without modification) yield different masses, which distinguishes the positional isomers in (1–3) and quantify the percentages of modification on the position A vs. B accordingly. (B) Quantification of phosphorylated positional isomers in human cTnI. The normalized absolute abundance ratios and phosphorylation occupancy (PPO%) of unphosphorylated c fragment ions from ECD spectra of both unphosphorylated and mono-phosphorylated molecular ions are plotted vs. the amino acid sequence (only 114 N-terminal residues shown). Positional isomers were identified and quantified as Ser22 (53±4%) and Ser76/77 (36±3%). Modified based on Ref.28 with permission.

After the identification of positional isomer sites, the next step is to quantify the occupancy of the modification on each site. In other words, how much (e.g. percent) of the total protein population is modified on position A vs. B? The top-down MS strategy with ECD has been successfully employed for quantitative characterization of positional isomers since ECD generates fragment-ion-rich data. 24, 28, 77 To quantify positional isomers carrying the stable modifications such as deamidation or acetylation, the ratio of unmodified to modified fragments generated in ECD spectra was measured in a single spectrum.28, 77 However, the accuracy in quantification of labile phosphorylated isomers would be compromised in a direct measurement of the abundance ratios of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated fragment ions (c/z•) within one spectrum. This is due to the possible effects from the presence of the phosphate moiety on the ECD cleavage efficiency. So the relative abundance of phosphorylated c ions derived from ECD are not necessarily proportional to the abundance of the corresponding phosphorylated isomeric precursors. Hence, we have developed a novel method to quantify positional isomers with labile modification such as phosphorylation.28 Our method utilized only the abundance of unphosphorylated fragment ions via intraspectrum normalization versus “internal standard” fragments followed by a comparison between ECD spectra of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated precursor ions. This allowed for an accurate quantitative determination of partial phosphorylation occupancies of the corresponding sites because the abundance ratios revealed the difference attributed to phosphorylation events. Using this methodology, we have quantified the phosphorylated positional isomers in human cTnI as Ser22: 53±4%; Ser76/Thr77: 36±3% (Fig. 4B).28 On the other hand, it is very difficult to use the bottom-up approach to determine the positional isomers due to the partial sequence coverage and loss of connectivity among different modifications.

Determination of the order of multiple phosphorylation sites

If a protein harbors multiple phosphorylation sites, one question is whether all modifications occurred simultaneously or sequentially. Top-down MS is well situated to answer this question since it can isolate each specific phosphorylation form and locate the sites. Recently, we have employed top-down MS to characterize the phosphorylation order in cTnI purified from non-human primate myocardial tissues.30 cTnI is present at un-, mono- and bis-phosphorylated forms with bis-phosphorylation as the predominant form. We have individually “gas-phase” isolated un-, mono-, bis-phosphorylated forms in the mass spectrometer and subsequently fragmented each form with ECD for localization of the modification sites. Ser23 was the only site phosphorylated in monophosphorylated cTnI form but Ser22 and Ser23 were both phosphorylated in bis-phosphorylated cTnI form, consistent with the phosphorylation occurred at Ser23 prior to Ser22.

We have also unveiled the phosphorylation order in both truncated and full-length recombinant mouse cMyBP-C,26 an important regulator of cardiac contractility located in the sarcomere’s thick filament.83–86 We have identified the phosphorylation sites in full-length recombinant cMyBP-C as Ser283, Ser292, and Ser312 (corresponding to Ser273/282/302 in endogenous mouse cMyBP-C) with a sequential phosphorylation among them: the phosphorylation of Ser292 occurs before phosphorylation of Ser312 and Ser283. Gautel et al. has previously identified these three sites as substrates for PKA.87 Ser292 is located on a cardiac-specific loop LAGARRTS and the phosphorylation of Ser292 could induce a conformational change which makes the other sites accessible to protein kinases.87 Surprisingly, the identified phosphorylation sites in truncated cMyBP-C protein are quite different from that of full-length cMyBP-C. We have localized the phosphorylation sites in C0-C4 (containing the intact N-terminal 4 domains and the cMyBP-C motif) to Ser292, Ser312, and Ser484 with no apparent phosphorylation order as both Ser292 and Ser312 were phosphorylated concurrently. This suggested that sequence truncations can alter the protein PTM state, which can potentially lead to variations in protein structure and function.26

Technical Challenges of Top-down MS

As illustrated above, top-down MS has many advantages for proteomics and is superior to the bottom-up approach for protein modification analysis. However, there are still technical challenges yet to be resolved to realize its full potential.

Protein solubility

Proteins are generally much more difficult to handle than small peptides mainly due to their poor solubility.21 Unlike the tryptic peptides which are highly soluble under the general LC/MS condition, proteins may not be all soluble under the same condition. In addition, some large proteins (MW >50 kDa) and almost all membrane proteins are difficult to solubilize without classic detergents (i.e. SDS and TritonRX-100). The available MS compatible detergents are not as effective as the classic detergents and degrade rapidly in a typical acidic LC/MS buffer (0.1 % formic acid). The “magic” top-down MS-compatible detergent which can solubilize all types of proteins is yet to be developed.

Sensitivity and detection limit

The sensitivity and detection limit of the mass spectrometer for proteins is much lower than that for peptides.21 Top-down MS could require much more concentrated and usually 10 or 100 folds more materials than that required for the bottom-up approach.32 In any type of MS instrument, the sensitivity decreases drastically with the increase of MW. At current stage it is still relatively difficult to analyze intact proteins larger than 70 kDa. Moreover, as the MW of the protein increases, the tertiary structure of proteins becomes more difficult to disrupt, which thereby limits the MS/MS fragmentation efficiency of intact proteins. Thus most of the top-down applications focused on proteins less than 50 kDa and there are very few applications to date on larger proteins (>100 kDa).22–32 Our lab has recently applied the top-down ECD MS/MS to a 142 kDa recombinant cMyBP-C and isotopically resolved a 115 kDa truncated form of cMyBP-C – the largest protein resolved isotopically to date.26 McLafferty and co-workers extended the top-down MS to proteins larger than 200 kDa by prefolding dissociation which utilizes variable thermal and collisional activation immediately after ESI.31 Nevertheless, it required high protein purity (>80% homogeneity) and high concentration (0.5–1 μg/μl) for top-down analysis of the proteins larger than 100 kDa. Hence, it is essential to develop MS instruments with increased sensitivity and lower detection limit for large proteins in order to generalize the use of top-down MS since the majority of the proteins in the proteome are larger than 50 kDa.

Requirement of high-end instruments

Another reason for the popularity of bottom-up approach is that small peptides (500–2000 Da) can be easily analyzed in low-end instruments such as ion trap mass spectrometer with low resolution (also at a low cost).21,32 In contrast, top-down generally requires high-end instruments with high-resolution (and high cost) to resolve the protein precursors as well as the large fragmentation ions. Although top-down MS has been extended to ion trap mass spectrometer especially with the help of ion-ion reaction, such an approach is still limited to a small number of academic labs and not generally available.88

Throughput

Historically, top-down MS has been employed for elegant and comprehensive characterization of purified single protein or protein mixture of relatively low to moderate complexity but with relatively low throughput. In the past ten years, Kelleher and other labs have been working on a high-throughput version of top-down proteomics integrating online separation of intact proteins, automatic MS and MS/MS data acquisition and bioinformatics tool for data processing (see review37). For example, Roth et al. detected > 600 unique intact masses (up to 63 kDa) in the human primary leukocytes using a multidimensional protein characterization by automated top-down approach.89 Subsequent MS/MS experiment identified 133 proteins from 67 unique genes with 32 of the identified proteins harboring coding polymorphisms and PTMs suggesting the diversity of the human proteome. Admittedly, the throughput of top-down proteomics, although increasing at a good rate, is still not comparable to bottom-up shotgun proteomics at its present stage. The question will remain whether one day in the future top-down proteomics can become a truly high-throughput complement to bottom-up proteomics.38

Conclusions and Perspectives

As reviewed here, top-down MS emerges as a powerful technology in proteomics particularly for the analysis of protein PTMs and sequence variants. It has offered unique opportunities to cardiovascular proteomics including unraveling molecular complexity, complete PTM mapping, quantification of modified protein forms, identification and quantification of positional isomers and determination of the order of multiple phosphorylations, which can be very difficult to achieve by the bottom-up MS approach. However, top-down MS is still in its early developmental stage and in the process of overcoming several technical challenges such as solubility, sensitivity, and throughput issues. Perceptibly, bottom-up proteomics as a mature technology will continue to serve as a workhorse in modern proteomics at present and in the near future. In some sense, the bottom-up and top-down are really complementary approaches in proteomics. Bottom-up MS is sufficient for identification of protein from the database and quantification of protein expression level. Meanwhile, top-down MS is ideally suited for the comprehensive analysis of protein PTMs and sequence variations. The synergy between bottom-up and top-down approaches will yield best proteomic results and broaden the application of proteomics in biomedical research. A combined bottom-up/top-down hybrid approach90 and a “middle-down” proteomics (MS on large peptides at about 3–20 kDa from limited digestion of proteins) will play potentially important roles during this high mass “void” till the point that top-down overcomes the technical challenges to realize its full potential.38 Evidently, the top-down MS has achieved substantial progress in the last few years.37 Hence, with continuous developments at such a speed on the new methodologies including the front end separation/protein solubility, MS instrument sensitivity and detection limit, and user-friendly data processing and automation software, it is hopeful that top-down MS soon can become widely used in the near future.

Needless to say, the ultimate goal of developing proteomic technologies is to understand molecular mechanism of diseases and to diagnose them at the early stage.1, 5–7 There are two major issues we must address to advance the application of top-down MS in cardiovascular research. First is to comprehensively characterize the protein modification states in disease models, including universal and unbiased detection of all PTMs and sequence variants, precise localization of the modification sites, identification and quantification of the changes in the distribution of PTMs (i.e. phosphorylation) among multiple targeted sites during disease progression. This goal can be readily achieved. In fact, our laboratory has already applied top-down MS to characterize cTnI from diseased cardiac tissues of humans and animal models (unpublished data). Second is to detect specific modifications of intact protein biomarkers (e.g. cTnI) in the general circulation system and subsequently characterize their modifications. Blood is certainly a much more practical source for routine clinical diagnosis than tissues (especially cardiac tissue). Therefore the ability to detect protein modifications in blood will significantly increase the impact of top-down MS. Obviously, this is much more challenging due to the high complexity and dynamic range in the blood proteome, which will require the development of a high resolution mass spectrometer with ultra-high sensitivity. In the near term, we can discover the specific modified form in tissues as potential candidate biomarkers and then validate them in serum/plasma using either an antibody approach (by developing antibodies recognizing the protein and its specific modifications) or targeted-MS approach (by developing multiple reaction monitoring with stable isotope dilution methods).91 Overall, we believe that with the continuous development in the technology front and with a collaborative effort among the MS/proteomics researchers, instrument engineers, biologists, clinicians, and bioinformatics specialists, top-down MS-based proteomics has great potential to transform the approach to cardiovascular research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Raquel Sancho Solis, Beth Altschafl, and Wei Xu for critical reading of this review.

Funding Sources:

This work was supported by the Wisconsin Partnership Fund for a Healthy Future and American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 0735443Z and National Institutes of Health Grant R01HL096971 (to Y.G.).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- PTMs

post-translational modifications

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- MW

molecular weight

- CID

collision-induced dissociation

- ECD

electron capture dissociation

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- LC

liquid chromatography

- GELFrEE

gel-eluted liquid fraction entrapment electrophoresis

- IEC

ion exchange chromatography

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

- RP

reverse-phase

- cTnI

cardiac troponin I

- FTICR

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance

- CIEF

capillary isoelectrofocusing

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- MALDI

matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization

- Q-TOF

quadrupole time-of-flight

- IRMPD

infrared multiphoton dissociation

- PSD

post-source decay

- ETD

electron transfer dissociation

- SILAC

stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- cTnT

cardiac troponin T

- cMyBP-C

cardiac myosin binding protein C

- Calc’d

calculated mass

- Expt’l

experimental mass

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Han Zhang and Dr. Ying Ge have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Arrell DK, Neverova I, Van Eyk JE. Cardiovascular proteomics - evolution and potential. Circ Res. 2001;88:763–773. doi: 10.1161/hh0801.090193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arab S, Gramolini AO, Ping PP, Kislinger T, Stanley B, van Eyk J, Ouzounian M, MacLennan DH, Emili A, Liu PP. Cardiovascular proteomics - tools to develop novel biomarkers and potential applications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1733–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White MY, Van Eyk JE. Cardiovascular proteomics - past, present, and future. Mol Diag Ther. 2007;11:83–95. doi: 10.1007/BF03256227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards AVG, White MY, Cordwell SJ. The role of proteomics in clinical cardiovascular biomarker discovery. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:1824–1837. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R800007-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ping PP, Chan DW, Srinivas P. Advancing cardiovascular biology and medicine via proteomics opportunities and present challenges of cardiovascular proteomics. Circulation. 2010;121:2326–2328. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.949230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kullo IJ, Cooper LT. Early identification of cardiovascular risk using genomics and proteomics. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:309–317. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasan RS. Biomarkers of cardiovascular disease - molecular basis and practical considerations. Circulation. 2006;113:2335–2362. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.482570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayr M, Zhang J, Greene AS, Gutterman D, Perloff J, Ping PP. Proteomics-based development of biomarkers in cardiovascular disease - mechanistic, clinical, and therapeutic insights. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1853–1864. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R600007-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fields S. Proteomics - proteomics in genomeland. Science. 2001;291:1221–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5507.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLafferty FW, Breuker K, Jin M, Han XM, Infusini G, Jiang H, Kong XL, Begley TP. Top-down ms, a powerful complement to the high capabilities of proteolysis proteomics. Febs J. 2007;274:6256–6268. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann M, Jensen ON. Proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:255–261. doi: 10.1038/nbt0303-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan C, Solaro RJ. Myofilament proteins: From cardiac disorders to proteomic changes. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2008;2:788–799. doi: 10.1002/prca.200780076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin WH, Brown AT, Murphy AM. Cardiac myofilaments: From proteome to pathophysiology. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2008;2:800–810. doi: 10.1002/prca.200780075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biesiadecki BJ, Elder BD, Yu ZB, Jin JP. Cardiac troponin T variants produced by aberrant splicing of multiple exons in animals with high instances of dilated cardiomyopathy. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50275–50285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messer AE, Jacques AM, Marston SB. Troponin phosphorylation and regulatory function in human heart muscle: Dephosphorylation of ser23/24 on troponin I could account for the contractile defect in end-stage heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marston SB, de Tombe PP. Troponin phosphorylation and myofilament Ca2+ -sensitivity in heart failure: Increased or decreased? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:603–607. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chait BT. Mass spectrometry: Bottom-up or top-down? Science. 2006;314:65–66. doi: 10.1126/science.1133987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han XM, Aslanian A, Yates JR. Mass spectrometry for proteomics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bogdanov B, Smith RD. Proteomics by FTICR mass spectrometry: Top down and bottom up. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2005;24:168–200. doi: 10.1002/mas.20015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yates JR, Ruse CI, Nakorchevsky A. Proteomics by mass spectrometry: Approaches, advances, and applications. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2009;11:49–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steen H, Mann M. The abc’s (and xyz’s) of peptide sequencing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:699–711. doi: 10.1038/nrm1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelleher NL, Lin HY, Valaskovic GA, Aaserud DJ, Fridriksson EK, McLafferty FW. Top down versus bottom up protein characterization by tandem high-resolution mass spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:806–812. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ge Y, Lawhorn BG, ElNaggar M, Strauss E, Park JH, Begley TP, McLafferty FW. Top down characterization of larger proteins (45 kda) by electron capture dissociation mass spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:672–678. doi: 10.1021/ja011335z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zabrouskov V, Han XM, Welker E, Zhai HL, Lin C, van Wijk KJ, Scheraga HA, McLafferty FW. Stepwise deamidation of ribonuclease a at five sites determined by top down mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2006;45:987–992. doi: 10.1021/bi0517584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayaz-Guner S, Zhang J, Li L, Walker JW, Ge Y. In vivo phosphorylation site mapping in mouse cardiac troponin I by high resolution top-down electron capture dissociation mass spectrometry: Ser22/23 are the only sites basally phosphorylated. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8161–8170. doi: 10.1021/bi900739f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ge Y, Rybakova IN, Xu QG, Moss RL. Top-down high-resolution mass spectrometry of cardiac myosin binding protein c revealed that truncation alters protein phosphorylation state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12658–12663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813369106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solis RS, Ge Y, Walker JW. Single amino acid sequence polymorphisms in rat cardiac troponin revealed by top-down tandem mass spectrometry. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2008;29:203–212. doi: 10.1007/s10974-009-9168-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zabrouskov V, Ge Y, Schwartz J, Walker JW. Unraveling molecular complexity of phosphorylated human cardiac troponin I by top down electron capture dissociation/electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:1838–1849. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700524-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang JA, Dong XT, Hacker TA, Ge Y. Deciphering modifications in swine cardiac troponin I by top-down high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:940–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu F, Xu Q, Dong X, Guy M, Guner H, Hacker TA, Ge Y. Top-down high-resolution electron capture dissociation mass spectrometry for comprehensive characterization of post-translational modifications in rhesus monkey cardiac troponin I. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2010 Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han XM, Jin M, Breuker K, McLafferty FW. Extending top-down mass spectrometry to proteins with masses greater than 200 kilodaltons. Science. 2006;314:109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.1128868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siuti N, Kelleher NL. Decoding protein modifications using top-down mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007;4:817–821. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan CM, Souda P, Bassilian S, Ujwal R, Zhang J, Abramson J, Ping PP, Durazo A, Bowie JU, Hasan SS, Baniulis D, Cramer WA, Faull KF, Whitelegge JP. Post-translational modifications of integral membrane proteins resolved by top-down fourier transform mass spectrometry with collisionally activated dissociation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:791–803. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900516-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zubarev RA, Horn DM, Fridriksson EK, Kelleher NL, Kruger NA, Lewis MA, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. Electron capture dissociation for structural characterization of multiply charged protein cations. Anal Chem. 2000;72:563–573. doi: 10.1021/ac990811p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper HJ, Hakansson K, Marshall AG. The role of electron capture dissociation in biomolecular analysis. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2005;24:201–222. doi: 10.1002/mas.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelleher NL. Top-down proteomics. Anal Chem. 2004;76:196A–203A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kellie JF, Tran JC, Lee JE, Ahlf DR, Thomas HM, Ntai I, Catherman AD, Durbin KR, Zamdborg L, Vellaichamy A, Thomas PM, Kelleher NL. The emerging process of top down mass spectrometry for protein analysis: Biomarkers, protein-therapeutics, and achieving high throughput. Mol BioSyst. 2010;6:1532–1539. doi: 10.1039/c000896f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia BA. What does the future hold for top down mass spectrometry? J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armirotti A, Damonte G. Achievements and perspectives of top-down proteomics. Proteomics. 2010;10:3566–3576. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen EI, McClatchy D, Park SK, Yates JR. Comparisons of mass spectrometry compatible surfactants for global analysis of the mammalian brain proteome. Anal Chem. 2008;80:8694–8701. doi: 10.1021/ac800606w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meng FY, Cargile BJ, Patrie SM, Johnson JR, McLoughlin SM, Kelleher NL. Processing complex mixtures of intact proteins for direct analysis by mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2002;74:2923–2929. doi: 10.1021/ac020049i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zong CG, Young GW, Wang YJ, Lu HJ, Deng N, Drews O, Ping PP. Two-dimensional electrophoresis-based characterization of post-translational modifications of mammalian 20s proteasome complexes. Proteomics. 2008;8:5025–5037. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ping PP, Zhang J, Pierce WM, Bolli R. Functional proteomic analysis of protein kinase C epsilon signaling complexes in the normal heart and during cardioprotection. Circ Res. 2001;88:59–62. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Labugger R, McDonough JL, Neverova I, Van Eyk JE. Solubilization, two-dimensional separation and detection of the cardiac myofilament protein troponin T. Proteomics. 2002;2:673–678. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200206)2:6<673::AID-PROT673>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fridriksson EK, Baird B, McLafferty FW. Electrospray mass spectra from protein electroeluted from sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1999;10:453–455. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(99)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tran JC, Doucette AA. Gel-eluted liquid fraction entrapment electrophoresis: An electrophoretic method for broad molecular weight range proteome separation. Anal Chem. 2008;80:1568–1573. doi: 10.1021/ac702197w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vellaichamy A, Tran JC, Catherman AD, Lee JE, Kellie JF, Sweet SMM, Zamdborg L, Thomas PM, Ahlf DR, Durbin KR, Valaskovic GA, Kelleher NL. Size-sorting combined with improved nanocapillary liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry for identification of intact proteins up to 80 kda. Anal Chem. 2010;82:1234–1244. doi: 10.1021/ac9021083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neverova I, Van Eyk JE. Role of chromatographic techniques in proteomic analysis. J Chromatogr B. 2005;815:51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qian WJ, Jacobs JM, Liu T, Camp DG, Smith RD. Advances and challenges in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based proteomics profiling for clinical applications. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1727–1744. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600162-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hage DS. Affinity chromatography: A review of clinical applications. Clin Chem. 1999;45:593–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gundry RL, Fu Q, Jelinek CA, Van Eyk JE, Cotter RJ. Investigation of an albumin-enriched fraction of human serum and its albuminome. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007;1:73–88. doi: 10.1002/prca.200600276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma S, Simpson DC, Tolic N, Jaitly N, Mayampurath AM, Smith RD, Pasa-Tolic L. Proteomic profiling of intact proteins using WAX-RPLC 2-D separations and FTICR mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:602–610. doi: 10.1021/pr060354a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simpson DC, Ahn S, Pasa-Tolic L, Bogdanov B, Mottaz HM, Vilkov AN, Anderson GA, Lipton MS, Smith RD. Using size exclusion chromatography-RPLC and RPLC-CIEF as two-dimensional separation strategies for protein profiling. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:2722–2733. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sheng S, Chen D, Van Eyk JE. Multidimensional liquid chromatography separation of intact proteins by chromatographic focusing and reversed phase of the human serum proteome - optimization and protein database. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:26–34. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500019-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marshall AG, Hendrickson CL. High-resolution mass spectrometers. Annu Rev Anal Chem. 2008;1:579–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.112945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature. 2003;422:198–207. doi: 10.1038/nature01511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scherperel G, Reid GE. Emerging methods in proteomics: Top-down protein characterization by multistage tandem mass spectrometry. Analyst. 2007;132:500–506. doi: 10.1039/b618499p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Syka JEP, Coon JJ, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Peptide and protein sequence analysis by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9528–9533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ge Y, ElNaggar M, Sze SK, Bin Oh H, Begley TP, McLafferty FW, Boshoff H, Barry CE. Top down characterization of secreted proteins from mycobacterium tuberculosis by electron capture dissociation mass spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s1044-0305(02)00913-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McAlister GC, Phanstiel D, Good DM, Berggren WT, Coon JJ. Implementation of electron-transfer dissociation on a hybrid linear ion trap-orbitrap mass spectrometer. Anal Chem. 2007;79:3525–3534. doi: 10.1021/ac070020k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bunger MK, Cargile BJ, Ngunjiri A, Bundy JL, Stephenson JL. Automated proteomics of E-Coli via top-down electron-transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2008;80:1459–1467. doi: 10.1021/ac7018409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Horn DM, Zubarev RA, McLafferty FW. Automated reduction and interpretation of high resolution electrospray mass spectra of large molecules. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2000;11:320–332. doi: 10.1016/s1044-0305(99)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meng FY, Cargile BJ, Miller LM, Forbes AJ, Johnson JR, Kelleher NL. Informatics and multiplexing of intact protein identification in bacteria and the archaea. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:952–957. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsai YS, Scherl A, Shaw JL, MacKay CL, Shaffer SA, Langridge-Smith PRR, Goodlett DR. Precursor ion independent algorithm for top-down shotgun proteomics. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:2154–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karabacak NM, Li L, Tiwari A, Hayward LJ, Hong PY, Easterling ML, Agar JN. Sensitive and specific identification of wild type and variant proteins from 8 to 669 kda using top-down mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:846–856. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800099-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takeda S, Yamashita A, Maeda K, Maeda Y. Structure of the core domain of human cardiac troponin in the ca2+-saturated form. Nature. 2003;424:35–41. doi: 10.1038/nature01780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Solaro RJ, Rosevear P, Kobayashi T. The unique functions of cardiac troponin I in the control of cardiac muscle contraction and relaxation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kuhn P, Xu QG, Cline E, Zhang D, Ge Y, Xu W. Delineating anopheles gambiae coactivator associated arginine methyltransferase 1 automethylation using top-down high resolution tandem mass spectrometry. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1272–1280. doi: 10.1002/pro.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Solaro RJ, van der Velden J. Why does troponin I have so many phosphorylation sites? Fact and fancy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:810–816. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang L, Wolska BM, Montgomery DE, Burkart EM, Buttrick PM, Solaro RJ. Increased contractility and altered ca2+ transients of mouse heart myocytes conditionally expressing pkc beta. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1114–C1120. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.5.C1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goldspink PH, Montgomery DE, Walker LA, Urboniene D, McKinney RD, Geenen DL, Solaro RJ, Buttrick PM. Protein kinase C epsilon overexpression alters myofilament properties and composition during the progression of heart failure. Circ Res. 2004;95:424–432. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000138299.85648.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scruggs SB, Walker LA, Lyu T, Geenen DL, Solaro RJ, Buttrick PM, Goldspink PH. Partial replacement of cardiac troponin I with a non-phosphorylatable mutant at serines 43/45 attenuates the contractile dysfunction associated with pkc epsilon phosphorylation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whitelegge JP, Zabrouskov V, Halgand F, Souda P, Bassiliana S, Yan W, Wolinsky L, Loo JA, Wong DTW, Faull KF. Protein-sequence polymorphisms and post-translational modifications in proteins from human saliva using top-down fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2007;268:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sze SK, Ge Y, Oh H, McLafferty FW. Top-down mass spectrometry of a 29-kda protein for characterization of any posttranslational modification to within one residue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1774–1779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251691898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ong SE, Mann M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics turns quantitative. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:252–262. doi: 10.1038/nchembio736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bantscheff M, Schirle M, Sweetman G, Rick J, Kuster B. Quantitative mass spectrometry in proteomics: A critical review. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;389:1017–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pesavento JJ, Mizzen CA, Kelleher NL. Quantitative analysis of modified proteins and their positional isomers by tandem mass spectrometry: Human histone h4. Anal Chem. 2006;78:4271–4280. doi: 10.1021/ac0600050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gordon EF, Muddiman DC. Quantification of singly charged biomolecules by electrospray ionization fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry utilizing an internal standard. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1999;13:164–171. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jiang L, Smith JN, Anderson SL, Ma P, Mizzen CA, Kelleher NL. Global assessment of combinatorial post-translational modification of core histones in yeast using contemporary mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27923–27934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pesavento JJ, Bullock CR, Leduc RD, Mizzen CA, Kelleher NL. Combinatorial modification of human histone h4 quantitated by two-dimensional liquid chromatography coupled with top down mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14927–14937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709796200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Waanders LF, Hanke S, Mann M. Top-down quantitation and characterization of silac- labeled proteins. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:2058–2064. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Collier TS, Sarkar P, Rao B, Muddiman DC. Quantitative top-down proteomics of silac labeled human embryonic stem cells. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:879–889. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Flashman E, Redwood C, Moolman-Smook J, Watkins H. Cardiac myosin binding protein C - its role in physiology and disease. Circ Res. 2004;94:1279–1289. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000127175.21818.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Winegrad S. Cardiac myosin binding protein C. Circ Res. 1999;84:1117–1126. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.10.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moss RL, Razumova M, Fitzsimons DP. Myosin crossbridge activation of cardiac thin filaments - implications for myocardial function in health and disease. Circ Res. 2004;94:1290–1300. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000127125.61647.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.de Tombe PP. Myosin binding protein C in the heart. Circ Res. 2006;98:1234–1236. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000225873.63162.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gautel M, Zuffardi O, Freiburg A, Labeit S. Phosphorylation switches specific for the cardiac isoform of myosin binding protein-c - a modulator of cardiac contraction. EMBO J. 1995;14:1952–1960. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reid GE, Shang H, Hogan JM, Lee GU, McLuckey SA. Gas-phase concentration, purification, and identification of whole proteins from complex mixtures. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7353–7362. doi: 10.1021/ja025966k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Roth MJ, Parks BA, Ferguson JT, Boyne MT, Kelleher NL. “Proteotyping”: Population proteomics of human leukocytes using top down mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2008;80:2857–2866. doi: 10.1021/ac800141g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu S, Lourette NM, Tolic N, Zhao R, Robinson EW, Tolmachev AV, Smith RD, Pasa-Tolic L. An integrated top-down and bottom-up strategy for broadly characterizing protein isoforms and modifications. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1347–1357. doi: 10.1021/pr800720d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fu Q, Schoenhoff FS, Savage WJ, Zhang PB, Van Eyk JE. Multiplex assays for biomarker research and clinical application: Translational science coming of age. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2010;4:271–284. doi: 10.1002/prca.200900217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]