Abstract

Advances in whole genome profiling have revolutionized the cancer research field, but at the same time have raised new bioinformatics challenges. For next generation sequencing (NGS), these include data storage, computational costs, sequence processing and alignment, delineating appropriate statistical measures, and data visualization. The NGS application MethylCap-seq involves the in vitro capture of methylated DNA and subsequent analysis of enriched fragments by massively parallel sequencing. Here, we present a scalable, flexible workflow for MethylCap-seq Quality Control, secondary data analysis, tertiary analysis of multiple experimental groups, and data visualization. This workflow and its suite of features will assist biologists in conducting methylation profiling projects and facilitate meaningful biological interpretation.

Keywords: next generation sequencing, DNA methylation, epigenetics, cancer, data analysis, data visualization

I. Introduction

Advances in whole genome profiling technologies have revolutionized the field of cancer research. These technologies have facilitated the discovery of potential biomarkers for disease development and progression as well as our understanding of the complex, underlying molecular mechanisms that lead to cancer. Reduction in costs have spurred the adoption of next generation sequencing (NGS) platforms which offer greater resolution and sensitivity compared to traditional microarray profiling. At the same time, NGS raises new bioinformatics challenges, both practical (e.g. data storage, computational costs) and theoretical (e.g. defining appropriate statistical measures).

A promising application of NGS is the whole-genome profiling of epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation. The addition of methyl groups to the 5' carbon position of cytosine bases is a major mechanism of epigenetic regulation which participates in reorganizing chromatin structure and silencing gene expression. Epigenetic alterations, such as tumor suppressor gene hypermethylation and oncogene hypomethylation, are hallmarks of cancer and play a pivotal role in tumorigenesis and disease progression.

The DNA methylation profiling approach used in our lab, MethylCap-seq involves the in vitro capture of methylated DNA with the high affinity methyl-CpG binding domain of human MBD2 protein and subsequent analysis of enriched fragments by massively parallel sequencing. Unsuccessful or incomplete capture reactions can result in the sequencing of non-methylated DNA fragments, leading to inconsistencies in or the absence of methylation enrichment in a sample. Likewise, poor sequencing library complexity and CpG coverage limit the statistical power to call differential methylation, and ultimately the reproducibility of the dataset. Conventional sequencing analysis pipelines often do not include assay-dependent quality control assessments. Spurious samples reduce analytical power and lead to excess “noise” in downstream analyses.

The challenges to data analysis are real. The numerous options for file processing and genome alignment mean any particular strategy requires extensive troubleshooting and optimization. Large file sizes make data visualization exceedingly difficult without the use of expensive commercial software packages or system resource-intensive publicly available programs. In more practical terms, MethylCap-seq projects, in particular, would greatly benefit from the ability to receive rapid feedback of overall experimental quality. There is also a lack of workflows for efficient analysis of large, MethylCap-seq datasets containing multiple sample groups. To address these pertinent issues, we have developed a scalable, flexible workflow for MethylCap-seq Quality Control and secondary data analysis which facilitates tertiary analysis of multiple experimental groups and data visualization.

The workflow is scalable in terms of handling studies of disparate sample sizes. It is flexible in that unique experimental considerations (genome alignment, read bin sizes, test statistics) can be addressed by simple modification of several operational parameters independent of the scripts responsible for automating the workflow. Automation is imperative because of the large number of intermediate steps and temporary files required. The workflow incorporates proven, existing tools where applicable: e.g., raw read processing, the short read aligner, the R environment and third party libraries. It further takes advantage of high performance computing systems for parallel batch job submissions. This feature is important for scalability and computational feasibility. Data visualization is supported by Anno-J, a genome annotation visualization program and web service viewport.

II. Methods

A. MethylCap-seq Experimental QC

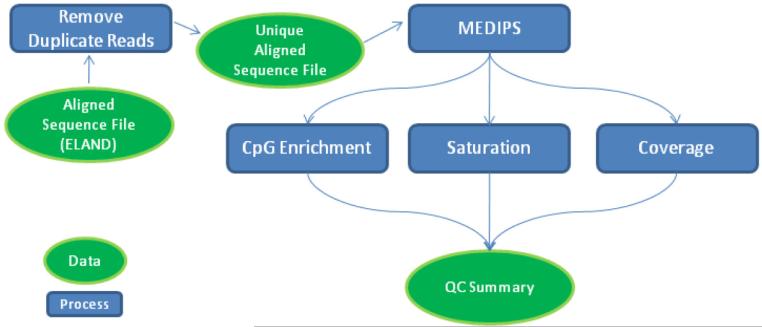

The quality control module identifies technical problems in the sequencing data and flags potentially spurious samples. The module is based on MEDIPs [1], an enrichment-based DNA methylation analysis package, and provides rapid feedback to investigators regarding dataset quality, facilitating protocol optimization prior to committing resources to a larger scale sequencing project. Fig. 1 illustrates the QC automated workflow. For each aligned sequencing file (e.g., the default output of Illumina's CASAVA pipeline), duplicate reads are removed (a correction for potential PCR artifacts), and a stripped, uniquely aligned sequence BED file is loaded into an R workspace for processing by the MEDIPS library. Three functions are performed on the data: Saturation analysis, CpG enrichment calculation, and CpG coverage analysis. The automated workflow produces a QC summary file containing the MEDIPs results and sequencing output metrics from the Illumina CASAVA pipeline. The QC module utilizes the parallel processing capability of a supercomputing environment to greatly decrease the time required for analysis.

Figure 1.

Diagram of MethylCap-seq QC Workflow

B. Sequence File Processing and Alignment

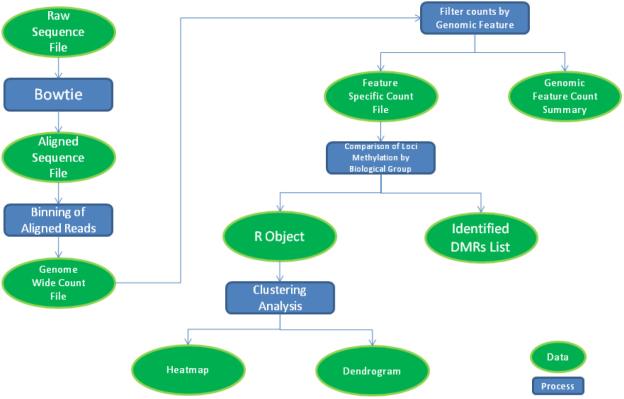

The ability to use multiple custom sequence alignment policies facilitates analysis of various genomic regions and features. Bowtie, a short read aligner, provides many alignment policies and options that allow a great deal of customization of the alignment output [2]. While our focus and workflow centers on reporting uniquely aligned reads, alternative alignment options are used for more customized data analysis. The qseq files are preprocessed for a uniquely aligned Bowtie output by being converted to FASTA format. The converted file is then aligned by Bowtie with options that optimize for uniquely aligned reads and output in SAM format. Post processing uses various SAMtools [3] commands to convert the alignment to BAM format and remove all duplicate reads from the alignment before converting back to a final SAM alignment. The workflow, illustrated in Fig. 2, is concisely handled by a single script which passes each intermediate stage of the alignment process to the subsequent stage and outputs a single SAM alignment file and a report of the number of reads that were aligned and those which were counted as duplicates. Speed is increased by Bowtie's multithreading options and by performing the alignment in a supercomputing environment. To achieve alternative alignments, Bowtie options can be changed, and different genomic sequences or subsets of genomic sequences may be used for alignment.

Figure 2.

Diagram of Global Methylation Analysis Workflow

C. Global Methylation Analysis Workflow

The methylation analysis workflow is outlined in Fig. 2. Chromosomal coordinates of sequence reads are parsed from the final alignment output, then counted using a specified bin size and read extension length (reflecting average fragment size) in order to generate a binary file containing bin counts and scaled count values (reads per million - rpms). The bin size determines the computational resolution of the analysis. We find that a bin size of 500bp provides sufficient analysis resolution while smoothing the data statistically. The binary counts file is next interrogated by genomic feature (e.g., CpG islands, CpG shores, Refseq genes) to generate feature-specific count files. The workflow is compatible with custom feature files listing genomic loci of interest in BED format. In addition, aggregate read count summaries can be compiled for each type of genomic feature.

Once the samples are binned and genomic features are extracted, they are grouped based on biological factors, such as known genotype difference, and statistical tests are performed to discern if there are significant differences in methylation counts among predefined groups of samples. One locus from a genomic feature in one group is tested against the same locus in the other group for all loci in that genomic feature. The statistical test used is dependent on the number of groupings. For two groups a Wilcoxon rank-sum test is employed to test the distribution of methylation counts for each locus across the two groups. We then select significant differentially methylated loci by applying a multiple test corrected p-value cutoff. Similarly for groupings of more than two biological factors, the Kruskal-Wallis test is employed. Statistical testing of genomic features is a custom workflow implemented in R which utilizes the predefined Wilcoxon and Kruskal-Wallis test functions. The output of the workflow is a list of loci from each genomic feature that passes significance testing. Boxplots are also created for the list of significant features for visualization of their differential methylation.

D. Clustering

To identify novel classifications of samples independently of predefined biological factors, unsupervised clustering of the data can be implemented. Clustering of the data is a workflow that takes a data matrix of the samples and the rpm value of each locus for a given genomic feature. The workflow is implemented in R and utilizes various R libraries for matrix manipulation, flashClust, and pvclust for unsupervised clustering. Adjusted p-values are obtained via multiscale bootstrap resampling of the data. Many combinations of correlation calculations and clustering methods can be implemented. Our clustering workflow uses the Pearson correlation distance measure. It takes as input the “raw” rpm data values or rescaled rpms, depending on the features of interest in the dataset. Rescaling the rpms involves dividing the rpms of each locus by the average rpm for that locus. This allows Pearson correlation to evenly weight both the low and high rpm values. Using the raw rpms causes Pearson correlation to more heavily weight the high rpms. The default clustering method of the workflow is that of McQuitty, but R provides any number of additional choices. Our workflow also implements data selection criteria that enforce a minimum coefficient of variation (CV) threshold in combination with minimum average rpm threshold for each locus. Data selection criteria are enforced in order to pare down the number of loci being used for clustering within each genomic feature. The rationale for this approach is that it allows the clustering to be performed on only the loci with the largest differences among samples; the minimum rpm value for each locus removes loci that were not pulled down well during sequencing and thus are expected to be rather noisy. Combinations of the selection criteria produce many different dendrograms of the data for evaluation and serve as a method for exploration of novel differentially methylated loci that may contribute to biological factors. In tandem with the dendrograms, heatmaps are also produced to help visualize the relationship between the clustering sample members. This entire workflow, including all combinations of selection criteria and all genomic features of interest, is completed in a single script.

Because we produce a variety of dendrograms through the use of various genomic features and loci selection criteria, it is useful to see if the membership of a significant group is conserved throughout the dendrograms that were created using other genomic features and even within genomic features analyzed with varying selection criteria. To easily visualize the location of a certain sample group's membership in other dendrograms, we use different colors to track the membership of that group through alternative dendrograms that are produced for different genomic features and selection criteria. If the membership of a group is conserved as we track it through alternative dendrograms, it is more likely to be biologically significant rather than an artifact of the specific clustering procedure. Tracking the membership of a group is accomplished by supplying the membership of that group to a color function that can be applied to subsequent dendrograms through the dendrapply function in R.

E. Data Visualization

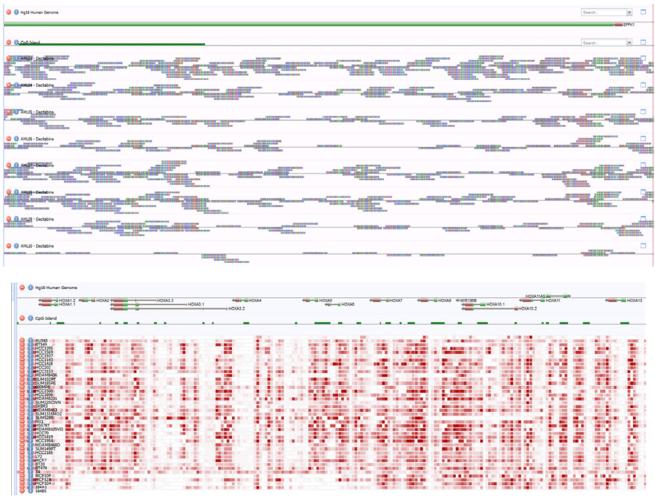

Effective data visualization can bridge the divide between computational and experimental biologists engaged in integrated analysis projects. Visual interpretation of patterns may permit the researcher to observe phenomena which computational analysis do not detect. In our workflow, we have incorporated Anno-J, a REST-based Web 2.0 application for the visualization of deep sequencing information and other genomic annotations [4]. Anno-J is capable of streaming all necessary applets and scripts to the user, providing immediate and installation-less viewing within a user's web browser. This facilitates the fast, real-time and interactive visualization of multiple data sets by users with access to any server hosting Anno-J.

Data visualization within Anno-J uses tracks, discrete rows of graphs, each of which corresponds to a particular set of data. Our workflow incorporates a number of custom scripts which allow quick conversion of binary and raw text read counts and SAM files to various Anno-J track formats, including standard mask and read tracks. These scripts extract from read count files the location and rpm, and from SAM files the location, sequence count and strand identifier, and generate Anno-J read track format files. For the experiment tracks, a scheduled service loads any new files from a shared folder into our database using a prescribed data format. Each track is assigned a unique identifier and properties for experiment type (e.g., methylation, small RNA) and track type (e.g., read, mask). The Anno-J web application will configure the browser with specified tracks based on these properties. The browser calls web services which return formatted data for each track, filtered by the currently viewable portion of the chromosome.

Additionally, we have incorporated a custom algorithm which allows conversion of binary and raw text read counts files to a custom discretized methylation heatmap track format. The heatmap track format modifies constraints and features of the Anno-J mask track format to allow generation of individual rows of heatmap data. Discretized methylation heatmap track generation may be accomplished by percentile ranking binned rpm values from binary or raw text read counts files, assigning color gradient based upon rank. Generation of the final discretized heatmap is a matter of stacking multiple heatmap tracks together. This allows for genome-wide methylation heatmaps, which may be traversed, scaled and rearranged interactively by the user in real-time.

III. RESULTS

The automated MethylCap-seq workflow has been developed over the course of 200 sequencing runs. It has been applied to human solid tumors (e.g., breast, ovarian, endometrial, and hepatocellular carcinoma) and blood cancers (e.g., acute myeloid leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia) as well a number of mouse cancer models.

From our QC workflow, we have found the following parameters considered collectively can flag problematic samples: CpG enrichment, saturation, CpG coverage, and alignment rate. Even valid samples occasionally fail a single parameter; thus, we typically exclude those which fail two or more parameters. In a recent 105 sample dataset, with multiple lanes of sequencing data generated per sample (207 lanes in total), 43 (20.8%) qualified for exclusion. Sequencing of new libraries generated for 12 samples with prior insufficient alignment rates all failed the QC as well. We conclude that sample intrinsic factors can dramatically impact the quality of methylation sequencing data.

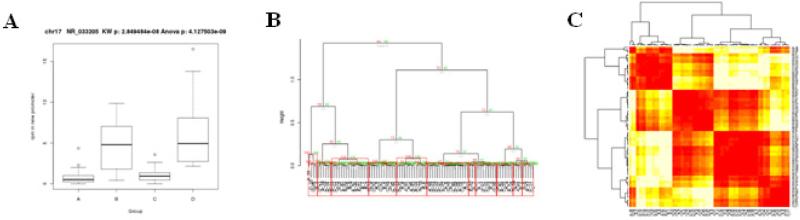

An example of methylation profiling analysis for four AML patient groups is shown in Fig. 3A–C. Hierarchical clustering of promoter regions passing threshold criteria (avg rpm > 10 and CV > 5) reveals four distinct patient groupings (Fig. 3B–1C).

Figure 3.

Methylation analysis of multiple sample groups. A, Boxplot of noncoding RNA NR_033202 promoter methylation in four groups of AML patients. Multiple-testing corrected parametric Anova and non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis p-values are shown. B, Clustering dendrogram of methylation in gene promoters among four groups of AML patients. Values at branches represent multiscale bootstrapping calculated approximately unbiased (AU) p-values (red) and bootstrap p-values (green). Red boxes indicate cluster branches which meet the AU p-value threshold for significance. Cluster labels indicating group membership are shown below the branches. C, Corresponding promoter methylation heatmap of dendrogram in Fig.3B.

Finally, the data workflow prepares samples for visualization in a web browser with Anno-J (Fig. 4). The top panel of Fig. 4 depicts methylation read data at the EPPK1 gene locus in eight AML patient samples. The bottom panel of Fig. 4 shows a methylation heatmap of the HOXA gene cluster in breast cancer cells (n=35) and normal breast epithelial cell lines (n=5).

Figure 4.

Data Visualization with Anno-J. Top, Methylation read data at single base resolution. Data depicted are the 5' end of the EPPK1 gene (track 1) and associated CpG island (track 2) in eight AML patient samples (tracks 3 – 10). Bottom, methylation heatmap of the HOXA gene cluster in 35 breast cancer cell and five normal breast epithelial cell lines (last five rows).

IV. CONCLUSION

In this paper, we presented a scalable, flexible workflow for performing MethylCap-seq Quality Control, secondary data analysis, tertiary analysis of multiple experimental groups, and data visualization in the web service viewport, Anno-J. As the cancer epigenetics field further expands into next generation sequencing, our workflow should assist biologists in conducting methylation profiling projects and facilitate meaningful biological interpretation

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by NCI Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016058 and CA102031 (PI: Marcucci).

REFERENCES

- [1].Chavez L, Jozefczuk J, Grimm C, et al. Computational analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation during the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells along the endodermal lineage. Genome Research. 2010 October 1;20(no. 10):1441–1450. doi: 10.1101/gr.110114.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg S. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biology. 2009;10(no. 3):R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009 August 15;25(no. 16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lister R, O'Malley RC, Tonti-Filippini J, et al. Highly Integrated Single-Base Resolution Maps of the Epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2008;133(no. 3):523–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]