Abstract

Objective

To verify circulating tumor cell (CTC) prognostic utility in stage IV resected melanoma patients in a prospective international phase III clinical trial.

Summary Background Data

Our studies of melanoma patients in phase II clinical trials demonstrated prognostic significance for CTCs in patients with AJCC stage IV melanoma. CTCs were assessed to determine prognostic utility in follow-up of disease-free stage IV patients pre- and during treatment.

Methods

After complete metastasectomy, patients were prospectively enrolled in a randomized trial of adjuvant therapy with a whole-cell melanoma vaccine plus Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vs. placebo plus BCG. Blood specimens obtained pretreatment (n=244) and during treatment (n=214) were evaluated by quantitative real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for expression of MART-1, MAGE-A3 and PAX3 mRNA biomarkers. Univariate and multivariate Cox analyses examined CTC biomarker expression with respect to clinicopathological variables.

Results

CTC biomarker(s) (≥1) was detected in 54% of patients pretreatment and in 86% of patients over the first 3 months. With a median follow-up of 21.9 months, 71% of patients recurred and 48% expired. CTC levels were not associated with known prognostic factors or treatment arm. In multivariate analysis, pretreatment CTC (>0 vs. 0 biomarker) status was significantly associated with disease-free survival (DFS) (HR 1.64, p=0.002) and overall survival (OS) (HR 1.53, p=0.028). Serial CTC (>0 vs. 0 biomarker) status was also significantly associated with DFS (HR 1.91, p=0.02) and OS (HR 2.57, p=0.012).

Conclusion

CTC assessment can provide prognostic discrimination before and during adjuvant treatment for resected stage IV melanoma patients. Study registration ID# NCT00052156.

Keywords: Melanoma, Circulating Tumor Cells, Stage IV, Prognosis

INTRODUCTION

There are no standard treatments for American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage IV melanoma.1 Surgery can be effective in carefully selected patients,2, 3 but nonsurgical approaches generally have low response rates and considerable toxicity. Although this is precisely the clinical setting for which reliable blood biomarkers would be most useful, none are available. The AJCC staging system uses anatomic site of metastasis and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), but these offer relatively limited prognostic discrimination. Tumor volume doubling time can predict response to metastasectomy but often cannot be measured.4

Detection of circulating tumor cells (CTC) by molecular approaches is a promising prognostic biomarker in melanoma patients5–11 In phase II clinical trials, we demonstrated the significance of a multimarker quantitative real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) assay for serial assessment of CTC in blood specimens from patients receiving immunotherapy and biochemotherapy for AJCC stage III or IV melanoma.12, 13

In 1998, an international, randomized, double-blinded, phase III study (the Malignant Melanoma Active Immunotherapy Trial for Stage IV Disease [MMAIT-IV]) was initiated to examine the efficacy of adjuvant treatment with a whole-melanoma cell vaccine, Canvaxin™, plus Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) versus placebo plus BCG after complete resection of stage IV melanoma.14 An ancillary aim of this study was to confirm that multimarker RT-qPCR assay of blood specimens for CTC could identify patients at high-risk of early recurrence after complete resection. The three mRNA melanoma biomarkers assessed for verification in this trial (MART-1, MAGE-A3, and PAX-3) were selected from our previously reported studies of melanoma biomarkers in sentinel node specimens from patients with AJCC stage IV metastatic melanoma.12, 13, 15–17 MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T-cells-1) is expressed in >90% of metastatic melanomas and is a melanogenesis differentiation antigen of melanoma. MAGE-A3 (melanoma antigen gene-A3) is a testis-associated antigen found in >60% of melanomas. PAX-3 (paired box homeotic gene transcription factor 3) is a transcription factor activated in melanomas which can regulate MITF and the melanogenesis gene pathway.

The results of this correlative study are the first large-scale confirmation of CTC for assessment of cancer outcome in a prospective international phase III clinical trial.18, 19 Findings demonstrate significance for CTC obtained before and during postoperative adjuvant treatment of patients with distant metastatic melanoma. These specific CTC biomarkers were selected from previous phase II clinical studies because of their robustness and sensitivity to clinical outcomes.

METHODS

Patients and blood specimens

Having met all of the clinical trial patient inclusion criteria (Supplement 1) and after providing informed consent, patients diagnosed with AJCC stage IV melanoma (AJCC 1997 staging guidelines)20, 21 were enrolled at 69 centers in the United States and at various international sites. The clinical trial and companion blood study were IRB approved at JWCI/St. Johns Health Center and all participating centers. Study candidates were patients who had an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1 and no clinical evidence of disease after surgical resection of no more than five metastases in no more than two visceral organ sites. After randomization, Canvaxin™, an allogeneic whole-cell vaccine, or placebo was administered by intradermal injection on days 0, 14, 28, 42, and 56, monthly thereafter during year 1, every 2 months during year 2, and every 3 months during year 3 through 5. BCG (Tice strain, Organon Technika Inc., Durham NC) was used as an immunological adjuvant with the first two doses of placebo or Canvaxin™. Description of the clinical trial is given on the NIH clinical trials registration site (NCT00052156).

Twenty-nine centers agreed to participate in the REMARK compliant prognostic CTC biomarker study (Supplement 2). Blood specimens collected before treatment (baseline), and at the end of months 1 and 3 were analyzed for this correlative biomarker study. Blood samples of patients (n=269) who agreed to participate in the CTC biomarker study were assessed. Excluded patients were those with blood samples having inadequate RNA quality (n=24) or lack of follow-up data (n=1), leaving 244 patients for analysis. Of those, 214 had serial bleed specimens available. Because five patients developed recurrence before the 1-month sampling point, the number of patients in the serial-bleed study was 214 for OS analysis and 209 for DFS analysis.

RNA extraction and multimarker RT-qPCR assay

All blood specimens were collected under a specific standard operating procedure (SOP) approved by the MMAIT-IV Group for all sites and monitored accordingly for quality control. Blood processing was performed under SOP in Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) conditions. For each draw, 10 ml of whole blood was collected in tubes containing sodium citrate. The first 2 ml of blood was discarded to prevent contamination by skin cells.17 Nucleated cells in blood were isolated using Purescript RBC Lysis Solution (Gentra). Total RNA was extracted from whole blood cells, and concentration was determined as previously described.22 Total RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed into cDNA as previously described.22

The optimized multimarker RT-qPCR assay12 was performed to assess the mRNA expression level of melanoma antigen recognized by T-cells 1 (MART1), melanoma antigen gene A3 family (MAGE-A3), and paired box homeotic gene transcription factor 3 (PAX3). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control of RNA quality. Specificity and optimization of the mRNA biomarkers were previously described.12, 13, 17 Primers of each gene were specifically designed to span at least two exons and only amplify cDNA. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) probes specific to each mRNA CTC biomarker were used.23 The multimarker RT-qPCR assays were performed by using iCycler iQ RealTime Thermocycler Detection System as previously described.23 PCR amplification was performed with custom PCR Supermix, ROX (Quanta Biosciences, Inc). Samples were amplified with a precycling hold at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min for GAPDH (59 °C for MART1, 58°C for MAGE-A3, 62°C for PAX3) and extension at 72°C for 1 min.

All samples were assessed in duplicate. The average value of the duplicates was used as the threshold (Cq) value. This mean Cq value was compared with cut-off Cq values that our group previously established for each tumor-related gene12; if the mean Cq was lower than the cut-off Cq, gene expression was considered to be positive. Before undertaking this study, we confirmed cut-off Cq for each gene in a validation set of peripheral blood lymphocytes from 22 healthy volunteers.

Each assay included biomarker-positive controls (three melanoma cell lines), biomarker-negative controls (two healthy donor peripheral blood lymphocytes), reagent controls, and no-template controls as previously described.12, 17, 23 A standard curve was generated by using threshold cycles of multiple serial dilutions of specific gene plasmid templates (10 to 106 copies); this curve was used for deriving template copy numbers PCR efficiency. Any sample assessed to have GAPDH at >30Cq was excluded from analysis for poor mRNA quality.

Biostatistical Analysis

Biostatistical analyses for the pretreatment study and the serial CTC study were performed separately. The demographic details, clinical characteristics and clinical outcomes of MMAIT-IV patients in the CTC study were compared with those of other MMAIT-IV patients, to confirm unbiased selection. In the serial CTC study, assay results were considered positive if any of the three biomarkers was detected. To evaluate the association between CTC biomarkers and subsequent recurrence, blood samples obtained after recurrence were excluded. Patient characteristics were tabulated and compared between the two treatment arms using Chi-square test for categorical variables and T-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for numerical variables. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were compared using log rank test. Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were measured from randomization. Cox model was developed to evaluate the predictive significance of the biomarkers for DFS and OS while other known clinical prognostic factors were adjusted: age, gender, melanoma stage (M1a and M1b of AJCC 2002 classification),21 number of metastatic lesions, elevated LDH, previous treatment for stage IV melanoma, treatment group (Canvaxin™ vs. placebo), and number of positive CTC biomarkers were included in the model.24 Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed in compliance with REMARK.19

SAS software (version 9.2, Cary, NC) was used to perform the statistical analyses. All tests were two-sided with significance at ≤ 0.05. The type 1 error was not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Patient population

Between May 1998 and April 2005, patients were accrued; when the clinical trial stopped accruing patients, 496 patients were enrolled at the 69 centers. Of the 496 trial patients, 269 patients at 27 U.S. sites and 2 foreign sites agreed to participate in the CTC biomarker study from clinical trial sites that had approved IRB for blood collection for CTC analysis. All 269 patients that agreed to participate in the CTC study were evaluated. Blood specimens collected from these patients were processed and shipped to the John Wayne Cancer Institute for molecular analysis. Of the 269 patients, 24 had blood specimens with inadequate RNA quality and one patient had incomplete follow-up data. These patients were not included in the final analysis. Adequate pretreatment blood specimens were available for all of the remaining 244 patients; adequate specimens from month 1 and/or month 3 were available for 214 of these patients.

Prognostic characteristics of the 244 patients in this CTC biomarker study had no significant difference to prognostic characteristics of the 252 remaining patients in MMAIT-IV not participating in the study.

Clinical characteristics of patients in the CTC biomarker study are listed in Table 1. There was no difference in established prognostic factors between the two treatment arms (data not shown). Therefore, patients from both arms were combined for the CTC study. At a median follow-up time of 21.9 months (40 months among survivors) for the 244 patients in the pre-treatment CTC study, 174 (71.3%) patients suffered disease recurrence and 116 expired(47.5%). At a median follow-up of 24.2 months for the 214 patients in the serial-bleed study, 148(69.2%) patients suffered disease recurrence and 98(45.8%) expired. The trial was officially closed for follow-up on 05/30/2010.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Pre-treatment | Serial Bleed | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 149 (61.1%) | 130 (60.8%) |

| Female | 95 (38.9%) | 84(39.2%) |

| Age at Randomization | ||

| Mean ± SD | 54.4 ± 12.8 years | 55.0 ± 12.5 years |

| Median, Range | 55.5, 21–79 years | 56, 22–79 years |

| Site/AJCC Stage of Metastases | ||

| M1a | 95 (38.9%) | 80 (37.4%) |

| M1b | 149 (61.1%) | 134 (62.6%) |

| Number of Metastases | ||

| 1 | 137 (56.1%) | 120 (56.1%) |

| 2–3 | 97 (39.8%) | 85 (39.7%) |

| 4–5 | 10 (4.1%) | 9 (4.2%) |

| Previous Treatment for Melanoma | ||

| Yes | 96 (39.3%) | 133 (62.2%) |

| No | 148 (60.7%) | 81 (37.8%) |

| Prior Diagnosis of Stage III | ||

| Yes | 129 (52.9%) | 103 (48.1%) |

| No | 115 (47.1%) | 111 (51.9%) |

| ECOG Performance Status | ||

| 0 | 206 (84.4%) | 182 (85.0%) |

| 1 | 38 (15.6%) | 32 (15.0%) |

| Elevated Baseline LDH | ||

| Yes | 24 (9.8%) | 19 (8.9%) |

| No | 220 (90.2%) | 195 (91.1%) |

Pre-treatment CTC Analysis

At least one CTC biomarker was detected in 132(54.1%) patients at baseline. MART-1, MAGE-A3, and PAX3 were detected in 64(26%), 56(23%), and 73(30%) patients, respectively. One CTC biomarker was positive in 78(32%), two biomarkers in 47(19.2%), and three biomarkers in seven patients(2.9%) (Supplemental Table 1). Although there was a tendency for LDH to be elevated in patients with at least one positive vs. all negative CTC biomarkers (12.9% vs. 6.3%, p=0.08), biomarker positivity was not significantly associated with sex, age, ECOG status, M1a vs. M1b, prior therapy for stage IV melanoma, or prior stage III disease. There was no association between CTC biomarker positivity and MMAIT-IV treatment arm; rate of positivity was 54% for the vaccine arm vs. 54% for the placebo arm (p=0.86).

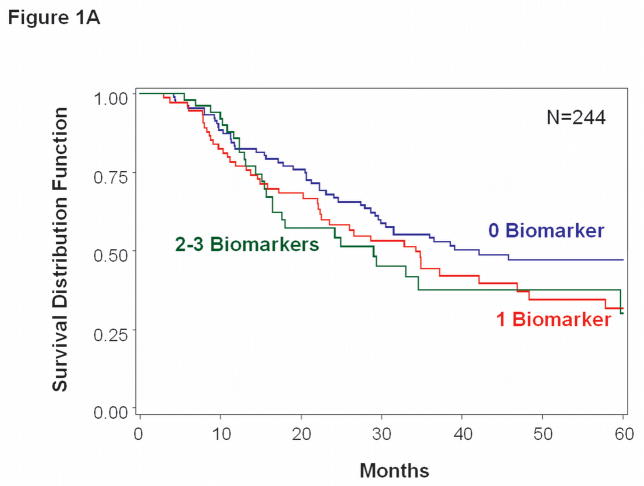

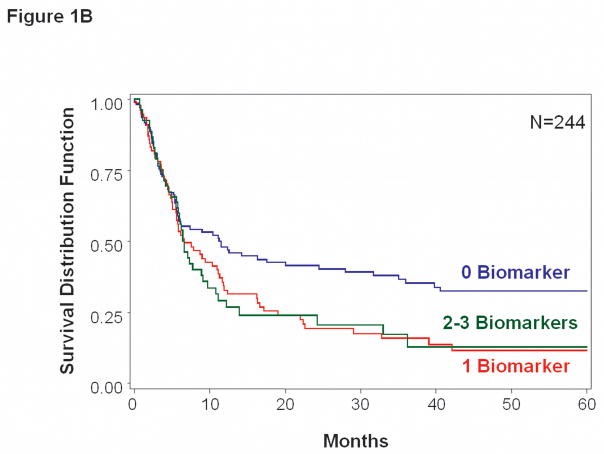

In multivariate analysis, pre-treatment CTC status (>0 vs. 0 biomarkers) was significantly associated with DFS (HR = 1.64, 95% CI 1.19–2.24, p = 0.002) and for OS (HR=1.53, 95% CI 1.05–2.24, p=0.028) (Table 2, Figure 1A&B). In addition to CTC status, DFS and OS were independently related to history of prior treatment for stage IV melanoma. No single individual CTC biomarker was significantly associated with clinical outcome at baseline, although univariate data demonstrated trends toward an adverse impact of positive CTC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Survival and Clinical Factors Based on Pre-treatment Blood Specimens

| Overall Survival | Disease-free Survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Factor | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value |

| Male vs. Female | 0.81 (0.56–1.18) | 0.270 | 1.15 (0.85–1.57) | 0.359 |

| Age (years) | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.580 | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.145 |

| M1b vs. M1a | 1.25 (0.86–1.82) | 0.238 | 1.04 (0.77–1.41) | 0.787 |

| >1 Lesion vs. 1 Lesion | 0.80 (0.55–1.17) | 0.249 | 0.91 (0.67–1.22) | 0.519 |

| Previous Treatment for Melanoma | 1.70 (1.18–2.45) | 0.005 | 1.31 (0.97–1.77) | 0.081 |

| Elevated LDH | 1.81(1.08–3.02) | 0.025 | 1.42 (0.88–2.29) | 0.147 |

| CanVaxin™ vs. Placebo | 1.17 (0.81–1.68) | 0.402 | 0.94 (0.70–1.26) | 0.669 |

| Individual biomarker | ||||

| MART-1 pos. vs. neg | 1.41 (0.94– 2.10) | 0.094 | 1.34 (0.96–1.85) | 0.082 |

| MAGE-A3 pos. vs. neg. | 1.02 (0.66–1.58) | 0.938 | 1.22 (0.87–1.72) | 0.254 |

| PAX3 pos. vs. neg. | 1.34 (0.90–1.99) | 0.148 | 1.26 (0.92–1.74) | 0.156 |

| Number of biomarkers (+) >0 vs. 0 | 1.43 (0.99–2.07) | 0.060 | 1.54(1.13–2.09) | 0.006 |

| Overall Survival | Disease-free Survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate Factor | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Male vs. Female | 0.78 (0.54–1.13) | 0.19 | 1.13 (0.83–1.55) | 0.43 |

| Age (years) | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.88 | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.28 |

| M1b vs. M1a | 1.24 (0.84–1.84) | 0.27 | 0.99 (0.72–1.36) | 0.96 |

| >1 lesion vs. 1 lesion | 0.86 (0.58–1.27) | 0.44 | 0.96 (0.71–1.31) | 0.80 |

| Previous Treatment for Melanoma | 1.74 (1.18–2.55) | 0.005 | 1.40 (1.01–1.93) | 0.044 |

| Elevated LDH | 1.69 (0.99–2.89) | 0.055 | 1.41 (0.87–2.29) | 0.17 |

| CanVaxin™ vs. Placebo | 1.21 (0.83–1.75) | 0.32 | 0.99 (0.73–1.34) | 0.96 |

| Number of biomarkers (+) >0 vs. 0 | 1.53 (1.05–2.24) | 0.028 | 1.64 (1.19–2.24) | 0.002 |

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves based on pre-treatment blood specimens. A, Overall survival tended to be worse for patients with >0 vs. 0 positive biomarkers (p=0.028). B, Disease-free survival was significantly worse for patients with >0 vs. 0 positive biomarkers (p=0.002).

Serial Bleed CTC Analysis

Of the 244 patients, 214 had blood specimens collected at month one (N=186) and/or month 3 (N=154). At least one CTC biomarker was positive in 86% patients at baseline, month 1, or month 3. One CTC biomarker was positive in 73(34%), two biomarkers in 65(30%) and three biomarkers in 47(22%) patients. The percentage positive for any given CTC biomarker did not vary significantly over time (Table 3).

Table 3.

qRT-PCR Positivity of Detected CTC Blood Biomarkers at Specific Bleed Points

| CTC Biomarker | Baseline | Month 1 | Month 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| MART-1 | 27.6% | 27.4% | 30.5% |

| MAGE-A3 | 22.9% | 39.8% | 32.5% |

| PAX3 | 29.4% | 22.6% | 25.3% |

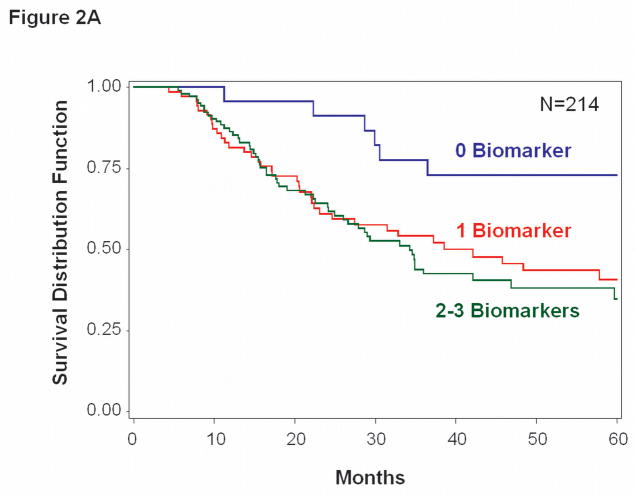

OS rates at 1, 2 and 3 years were significantly higher for patients who had no positive CTC biomarkers (96%, 92%, and 71%, respectively) versus 1 positive CTC biomarker (82%, 62% and 55%, respectively; p=0.033) or 2–3 positive CTC biomarkers (86%, 64% and 42%, respectively; p=0.011) (Figure 2A). Multivariate analysis of OS to the presence of CTC (>0 vs. 0 biomarkers) was significant; HR=2.57, 95% CI 1.23–5.36, p=0.012 (Table 4). Previous treatment for stage IV melanoma was the only other variable independently associated with OS.

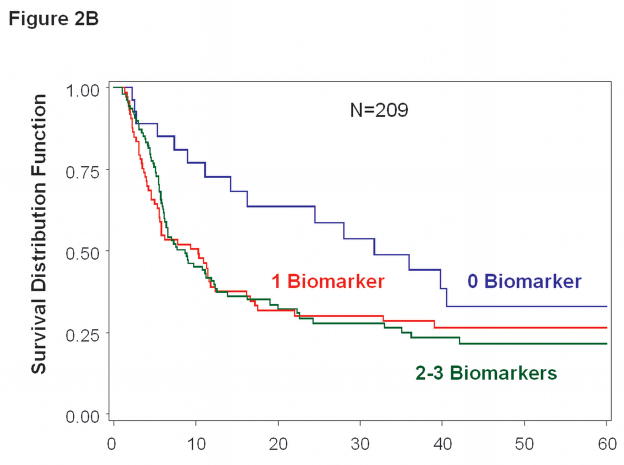

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves based on serial bleed specimens. A, Overall survival was significantly worse for patients with >0 vs. 0 positive biomarkers (p=0.012). B, Disease-free survival was significantly worse for patients with >0 vs. 0 positive biomarkers (p=0.020).

Table 4.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Survival and Clinical Factors Based on Serial-bleed Specimens

| Overall Survival | Disease-free Survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Factor | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Male vs. Female | 0.84 (0.56–1.25) | 0.382 | 1.21 (0.86–1.70) | 0.265 |

| Age (years) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.542 | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.452 |

| M1b vs. M1a | 1.48(0.97–2.25) | 0.067 | 1.17 (0.83–1.64) | 0.378 |

| >1 Lesion vs. 1 Lesion | 0.77(0.52–1.16) | 0.218 | 0.96 (0.69–1.33) | 0.795 |

| Previous Treatment for Melanoma | 1.63(1.09–2.44) | 0.016 | 1.26 (0.90–1.77) | 0.172 |

| Elevated LDH | 1.51(0.82–2.76) | 0.181 | 1.30 (0.75–2.25) | 0.357 |

| Canvaxin™ vs. Placebo | 1.03(0.69–1.53) | 0.888 | 0.92 (0.66–1.27) | 0.607 |

| Individual marker | ||||

| MART-1 pos. vs. neg | 1.28 (0.86–1.91) | 0.228 | 1.13 (0.81–1.57) | 0.447 |

| MAGE-A3 pos. vs. neg. | 1.52 (1.01–2.28) | 0.046 | 1.27 (0.91–1.78) | 0.160 |

| PAX3 pos. vs. neg. | 1.34 (0.90–1.20) | 0.150 | 1.06 (0.76–1.47) | 0.749 |

| Number of biomarkers (+)c >0 vs. 0 | 2.48(1.20–5.11) | 0.014 | 1.77 (1.04–3.03) | 0.037 |

| OS | DFS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate Factor | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p value |

| Male vs. Female | 0.86 (0.57–1.29) | 0.46 | 1.27 (0.90–1.80) | 0.18 |

| Age (years) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.22 | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.69 |

| M1b vs. M1a | 1.33 (0.86–2.06) | 0.20 | 1.00 (0.69–1.43) | 0.98 |

| >1 Lesion vs. 1 Lesion | 0.81 (0.54–1.23) | 0.33 | 1.04 (0.74–1.46) | 0.81 |

| Previous Treatment for Melanoma | 1.75 (1.15–2.66) | 0.009 | 1.29 (0.90–1.85) | 0.16 |

| Elevated LDH | 1.52 (0.82–2.83) | 0.19 | 1.39 (0.79–2.44) | 0.26 |

| Canvaxin™ vs. Placebo | 0.97 (0.64–1.45) | 0.87 | 0.93 (0.66–1.29) | 0.66 |

| Number of biomarkers (+) >0 vs. 0 | 2.57 (1.23–5.36) | 0.012 | 1.91 (1.11–3.30) | 0.020 |

DFS rates showed a similar relationship with CTC biomarker expression (Figure 2B). Five of the 214 patients were excluded from this analysis because their disease recurred before the first postoperative blood specimen was obtained. Multivariate analysis of DFS to the presence of CTC (>0 vs. 0 biomarker) was significant; HR=1.91, 95% CI 1.11–3.30, p=0.020 (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Molecular detection of CTC is a topic of major interest in oncology, but its relevance/value has been controversial because of lack of validation in prospective, multicenter phase III clinical trials, and the use of single mRNA biomarkers with high false-positive/false-negative rates. Patient sample size for CTC analysis has been limited by the availability of follow-up data and often leads to distorted interpretation of results. Many groups have found PCR detection of tyrosinase mRNA to have inadequate sensitivity for prognostic evaluation of blood specimens from patients with melanoma.25, 26 A recent meta-analysis reviewed the major findings on clinical utility of CTC in melanoma,27 but this type of evaluation has its limitations because of the rapid evolution of molecular diagnostic techniques in recent years. Current CTC techniques provide improved sensitivity and specificity through quantification. Also, studies based on single biomarkers have limited value in heterogeneous cancers such as cutaneous melanoma.13 Advanced-stage melanomas have considerable heterogeneity in tumor-related genes due to genomic instability and other ongoing molecular related events. Until now, no study has confirmed the translational utility of CTC assays for stage IV melanoma patients in a large-scale and long-term follow-up prospective NIH registered phase III clinical trial.

We previously demonstrated that multimarker RT-qPCR detection of CTC in blood was correlated with disease progression and OS for patients with metastasis receiving neoadjuvant biochemotherapy for stage III and IV melanoma in a multicenter phase II study.12, 17 We have shown that the use of multiple CTC biomarkers can circumvent difficulties associated with single-marker CTC detection, such as melanoma tumor heterogeneity28–30, level of mRNA expression in CTC31, and frequency of CTC in blood.13 The current prospective international study confirms the potential utility of multimarker RT-qPCR assay for detecting clinically relevant CTC in patients with advanced melanoma. In addition, it demonstrates the feasibility of quantitative CTC biomarker assessment by a centralized laboratory using serial specimens assessed from both domestic and international sites. Our results further validate the current assay platform as a reliable resource for identification of prognostic biomarkers in stage IV melanoma patients.

The three optimized CTC biomarkers in this study were selected based on their frequency of detection in the blood of patients with melanoma, and on their specificity for melanoma.23 The selection pool included mRNA biomarkers initially screened and assessed for a correlation with disease outcome in phase II clinical trials.12, 17 Subsequent investigation in the phase III clinical trial setting, with its carefully defined entry criteria and rigorously followed study calendar, is essential for confirming a potential correlation between CTC expression and recurrence, particularly since it allows for assessment of serial blood specimens collected under protocols specifically designed for molecular assays. Short of implementing the CTC results in determining treatment course, this study has definitively confirmed the prognostic value of our CTC assay.18 We found that CTC positivity of pre-treatment (single point sampling) and serial blood specimens was significant for OS and DFS in multivariate analysis. Both findings of the sampling suggest that multipoint sampling of blood times have different inference in prognostic utility. Our results also confirm the variable clinical course of stage IV melanoma, even after stratification by conventional prognostic variables. Biomarker status was not significantly associated with other potential clinical or pathological prognostic variables.

Recent advances in CTC detection assays, such as the use of cytokeratin-specific antibody immunomagnetic beads for CTC enrichment, have value in epithelial malignancies,32, 33 but this value depends on antibody specificity and sensitivity. We recently reported a similar approach in melanoma using multiple antibodies targeting melanoma cell-surface antigens to capture melanoma CTC then verifying these RT-qPCR biomarkers.15, 31 Alternatively, a carefully selected panel of biomarkers can eliminate the need for CTC enrichment, particularly if the biomarkers are melanoma-specific and from non-overlapping pathways.13 We have shown that multimarker RT-qPCR analysis can upstage H&E/IHC negative sentinel lymph nodes.34 Our recently reported 10-year follow-up study of the same CTC biomarker expression in melanoma-draining sentinel lymph nodes confirmed a significant correlation between biomarker expression and survival.15, 16 This further supports the prognostic utility of the CTC biomarkers that were selected.

The recent introduction and clinical testing of promising agents such as ipilimumab,35 PLX4032,36 and Abraxane,37 have increased the need for blood-based biomarkers to monitor response to therapy for advanced melanoma. In previous phase II studies of metastasis melanoma patients, we demonstrated that serial biomarker levels could be used to determine the response to biochemotherapy.12, 17 Early identification of treatment failures using CTC biomarkers in combination with other considerations could allow clinicians to switch therapies earlier. Prognostic assessment after metastasectomy but before adjuvant treatment may be very useful to stratify patients for appropriate therapies. Postoperative evidence of tumor cells in the blood after clinically complete resection indicates a high likelihood of disease recurrence. Because current options for monitoring progression of stage IV melanoma are limited, measurement of clinically relevant blood biomarkers such as CTC could become an important companion assay in clinical trials of new therapies for advanced-stage melanomas.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

This work was supported by the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation as well as Award Number P0 CA012582 from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Clinical Trials Identification Number: NCT00052156

References

- 1.Barth A, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Prognostic factors in 1,521 melanoma patients with distant metastases. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181(3):193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ollila DW. Complete metastasectomy in patients with stage IV metastatic melanoma. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(11):919–24. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70938-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton DL, Hsueh EC, Essner R, et al. Prolonged survival of patients receiving active immunotherapy with Canvaxin therapeutic polyvalent vaccine after complete resection of melanoma metastatic to regional lymph nodes. Ann Surg. 2002;236(4):438–48. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200210000-00006. discussion 448–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ollila DW, Stern SL, Morton DL. Tumor doubling time: a selection factor for pulmonary resection of metastatic melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 1998;69(4):206–11. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199812)69:4<206::aid-jso3>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mocellin S, Del Fiore P, Guarnieri L, et al. Molecular detection of circulating tumor cells is an independent prognostic factor in patients with high-risk cutaneous melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;111(5):741–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mocellin S, Hoon D, Ambrosi A, et al. The prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in patients with melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(15):4605–13. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mellado B, Colomer D, Castel T, et al. Detection of circulating neoplastic cells by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction in malignant melanoma: association with clinical stage and prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(7):2091–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curry BJ, Myers K, Hersey P. MART-1 is expressed less frequently on circulating melanoma cells in patients who develop distant compared with locoregional metastases. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2562–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gogas H, Kefala G, Bafaloukos D, et al. Prognostic significance of the sequential detection of circulating melanoma cells by RT-PCR in high-risk melanoma patients receiving adjuvant interferon. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(2):181–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmieri G, Ascierto PA, Perrone F, et al. Prognostic value of circulating melanoma cells detected by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(5):767–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keilholz U, Goldin-Lang P, Bechrakis NE, et al. Quantitative detection of circulating tumor cells in cutaneous and ocular melanoma and quality assessment by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(5):1605–12. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koyanagi K, O’Day SJ, Gonzalez R, et al. Serial monitoring of circulating melanoma cells during neoadjuvant biochemotherapy for stage III melanoma: outcome prediction in a multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):8057–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoon DS, Bostick P, Kuo C, et al. Molecular markers in blood as surrogate prognostic indicators of melanoma recurrence. Cancer Res. 2000;60(8):2253–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morton DL, Mozzillo N, Thompson JF, et al. An international, randomized, phase III trial of bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) plus allogeneic melanoma vaccine (MCV) or placebo after complete resection of melanoma metastatic to regional or distant sites. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18S):Abstract 8508. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeuchi H, Morton DL, Kuo C, et al. Prognostic significance of molecular upstaging of paraffin-embedded sentinel lymph nodes in melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(13):2671–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholl MB, Elashoff D, Takeuchi H, et al. Molecular Upstaging Based on Paraffin-Embedded Sentinel Lymph Nodes: Ten-year Follow-up Confirms Prognostic Utility in Melanoma Patients. Ann Surg. 2011;253(1) doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fca894. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koyanagi K, O’Day SJ, Boasberg P, et al. Serial monitoring of circulating tumor cells predicts outcome of induction biochemotherapy plus maintenance biotherapy for metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(8):2402–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buyse M, Sargent DJ, Grothey A, et al. Biomarkers and surrogate end points--the challenge of statistical validation. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(6):309–17. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, et al. REporting recommendations for tumor MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK) Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2(8):416–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 5. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6. New York: Springer-Veriag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koyanagi K, Bilchik AJ, Saha S, et al. Prognostic relevance of occult nodal micrometastases and circulating tumor cells in colorectal cancer in a prospective multicenter trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(22):7391–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koyanagi K, Kuo C, Nakagawa T, et al. Multimarker quantitative real-time PCR detection of circulating melanoma cells in peripheral blood: relation to disease stage in melanoma patients. Clin Chem. 2005;51(6):981–8. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.045096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(16):3622–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bostick PJ, Chatterjee S, Chi DD, et al. Limitations of specific reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction markers in the detection of metastases in the lymph nodes and blood of breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(8):2632–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung FA, Buzaid AC, Ross MI, et al. Evaluation of tyrosinase mRNA as a tumor marker in the blood of melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(8):2826–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.8.2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mocellin S, Hoon DS, Pilati P, et al. Sentinel lymph node molecular ultrastaging in patients with melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1588–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gast A, Scherer D, Chen B, et al. Somatic alterations in the melanoma genome: a high-resolution array-based comparative genomic hybridization study. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49(8):733–45. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarantou T, Chi DD, Garrison DA, et al. Melanoma-associated antigens as messenger RNA detection markers for melanoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57(7):1371–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scolyer RA, Mihm MCJ, Cochran AJ, et al. Pathology of melanoma. In: Balch CM, Houghton AN, Sober AJ, et al., editors. Cutaneous Melanoma. Vol. 5. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitago M, Koyanagi K, Nakamura T, et al. mRNA expression and BRAF mutation in circulating melanoma cells isolated from peripheral blood with high molecular weight melanoma-associated antigen-specific monoclonal antibody beads. Clin Chem. 2009;55(4):757–64. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.116467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(8):781–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, Bolt-de Vries J, et al. Molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells in large quantities of contaminating leukocytes by a multiplex real-time PCR. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118(3):455–68. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuo CT, Hoon DS, Takeuchi H, et al. Prediction of disease outcome in melanoma patients by molecular analysis of paraffin-embedded sentinel lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(19):3566–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(9):809–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hersh E, Millward M, Elias I, Iglesias J. An open-label, multicenter, phase II trial of nab-paclitaxel (NP) versus dacarbazine (DTIC) in previously untreated patients (PTs) with metastatic malignant melanoma (MMM) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15S):Abstract TPS314. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.