Abstract

The plasma concentration of fibrinogen varies in the healthy human population between 1.5 and 3.5 g/L. Understanding the basis of this variability has clinical importance because elevated fibrinogen levels are associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk. To identify novel regulatory elements involved in the control of fibrinogen expression, we used sequence conservation and in silico–predicted regulatory potential to select 14 conserved noncoding sequences (CNCs) within the conserved block of synteny containing the fibrinogen locus. The regulatory potential of each CNC was tested in vitro using a luciferase reporter gene assay in fibrinogen-expressing hepatoma cell lines (HuH7 and HepG2). 4 potential enhancers were tested for their ability to direct enhanced green fluorescent protein expression in zebrafish embryos. CNC12, a sequence equidistant from the human fibrinogen alpha and beta chain genes, activates strong liver enhanced green fluorescent protein expression in injected embryos and their transgenic progeny. A transgenic assay in embryonic day 14.5 mouse embryos confirmed the ability of CNC12 to activate transcription in the liver. While additional experiments are necessary to prove the role of CNC12 in the regulation of fibrinogen, our study reveals a novel regulatory element in the fibrinogen locus that is active in the liver and may contribute to variable fibrinogen expression in humans.

Introduction

Fibrinogen is the major coagulation protein by mass and has a central role in platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. It is also an important determinant of blood viscosity and thrombophilia, and also plays a role in the proliferation of vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells.1–4

The fibrinogen plasma level varies within the healthy population ranging from 1.5 to 3.5 g/L. An increase in fibrinogen concentration of 1 g/L above the normal range is associated with a near doubling of cardiovascular disease risk.5 Environmental factors such as smoking, body mass index, and age, or characteristic physiological states such as pregnancy and inflammation have been associated with higher or lower fibrinogen levels.6 The heritability of plasma fibrinogen level has been estimated between 20% and 50%.7,8 Therefore, we speculated that common genetic variations localized in regulatory or coding regions of the fibrinogen cluster affect fibrinogen plasma levels that in turn influence formation of the fibrin network, its structure or the sensitivity of the fibrin clot to fibrinolysis. Thus, identifying new sequences contributing to the regulation of fibrinogen gene expression may add further insight into the genetic components involved in the heritability of plasma fibrinogen levels and could be of clinical relevance for the prediction of cardiovascular events.

Fibrinogen is a hexamer composed of 2 copies of 3 polypeptide chains Aα, Bβ and γ. These are encoded by 3 genes, FGB, FGA, and FGG (ordered from centromere to telomere) clustered in a 50-kb region on the long arm of human chromosome 4 (4q32). Fibrinogen biosynthesis occurs in the liver where the 3 genes undergo coordinate transcription. Functional transcription factor binding sites have been described within the 3 promoter regions.9 Two transcription factors, CCAAT-box/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) and the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 (HNF-1), play an important role in the basal expression of FGA and FGB. The increased expression of the 3 genes during the acute phase is mediated by interleukin-6 responsive elements, identified in the promoter regions of all 3 genes.9

Further investigations into the transcriptional regulation of the fibrinogen gene cluster are required to explain the coordinate liver-specific transcription pattern of the fibrinogen genes.10,11 The majority of studies on fibrinogen transcriptional regulation have focused on the proximal promoter regions. Surprisingly, the role of regulatory sequences situated at larger distances from the fibrinogen gene transcription start sites has not been addressed. Indeed, it is now generally assumed that highly tissue-specific or complex expression patterns of vertebrate genes are achieved by coordinate actions of promoter regions and regulatory elements.12,13 These regulatory elements can be separated by several megabases from their target gene(s).14 Therefore the identification of these sequences remains challenging because it implicates short regulatory elements of a few hundred base pairs embedded in large genomic regions.

To identify regulatory elements driving tissue-specific transcription, comparative sequence analysis has been used successfully by starting with the underlying hypothesis that functional regions of the genome are less tolerant to nucleotide substitutions and thus portray higher evolutionary conservation than expected under neutral selection.12,15–19 To this end, experimental strategies combining in vitro screens of numerous sequences followed by in vivo investigation of the spatio-temporal pattern of enhancer activity have been proposed.20,21 Functional conserved noncoding sequences (CNCs) have been extensively associated with temporal, spatial, and quantitative regulation of gene expression,22 playing roles in development23 and disease.24

Genome comparisons using the human, mouse, chicken, and frog sequences reveal remarkable conservation of the fibrinogen gene cluster structure as well as a conserved adjacent syntenic region.25 It has been suggested that the need to keep long-range cis-regulatory elements in cis with their target genes during evolution has contributed to structured conserved blocks of synteny observed in vertebrate genomes.25,26 This hypothesis implies that transcriptional regulatory mechanisms have been conserved for the fibrinogen genes and involve regulatory elements residing in the syntenic regions including the fibrinogen gene cluster.

To identify novel regulatory elements involved in the transcriptional regulation of the fibrinogen cluster, we assessed the in vitro regulatory potential of 14 CNCs from the syntenic genomic landscape of the fibrinogen cluster. We found 4 CNCs with enhancer activity and 1 potential silencer. Liver activity for 1 of the 4 enhancer CNCs was confirmed in vivo using EGFP reporter gene transgenic zebrafish and validated in LacZ reporter gene mouse embryos. These results demonstrate the presence of a novel liver enhancer within the fibrinogen cluster located between the FGB and FGA genes.

Methods

Cell culture

Human hepatoma HuH7 and human embryonic kidney (HEK-293T) cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen). Human hepatoma HepG2 cells were cultured in Eagle minimum essential medium (Sigma-Aldrich) also supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen).

In vitro enhancer assays using luciferase gene reporter plasmids

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers for the amplification of selected human CNCs (CNC1 to CNC14) are listed in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The amplified fragments, which include SalI restriction sites on both extremities, were inserted upstream of the minimal TATA-like promoter (pTAL) in the XhoI site of the pTAL firefly luciferase (pTAL-Luc) reporter plasmid (Clontech Laboratories).

HEK-293T, HuH7, and HepG2 cells were seeded at 104, 1.5 × 104, and 3 × 104 cells per well, respectively, in opaque 96-well plates (PerkinElmer) 24 hours before transfection. Each well was transfected with 100 ng of pTAL-Luc firefly reporter construct and 8 ng of transfection control plasmid encoding the renilla luciferase gene (pRL-SV40; Promega), using FuGENE-HD (Roche) as transfection reagent, according to the manufacturer's instructions. These transient cotransfections were performed in technical triplicates and in 3 independent transfection experiments. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the activities of firefly and renilla luciferase were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega). Luciferase activity ratio (firefly/renilla) for each transfection condition was normalized to the ratio obtained with control plasmid (pTAL-Luc without a CNC sequence) present on each plate. Enhancer activity of each CNC sequence was assessed by comparison with the basal transcriptional activity of the luciferase coding plasmids carrying no CNCs (normalized to 1.0). Normalization to the mean activity of the control condition gave the fold-change in luciferase activity values presented.

EGFP reporter gene enhancer assay in zebrafish embryos

The human sequences of CNC4, CNC10, CNC12, and CNC13 were amplified from the pTAL-Luc reporter plasmid by PCR (Clontech Laboratories; supplemental Table 1), adding a HindIII site on their 5′ end and a BamHI site on their 3′ end, and cloned directionally into the homemade pTRAN plasmid. In this manner, the CNC sequences were inserted in front of a human β-globin/mouse Hspa1a minimal promoter and the enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP) gene, followed by a simian virus (SV)40 polyadenylation signal. The reporter cassettes (CNCs, β-globin promoter, EGFP, and polyadenylation signal) were amplified from the pTRAN vector, adding a SalI site upstream of CNCs, and subcloned via pCRII-TOPO (Invitrogen) between the XhoI and HpaI sites of pT2KXIGΔin, a Tol2 transposon system gene transfer plasmid.27 A similar construct lacking a CNC was used as a negative control. As a positive control, we amplified by PCR 1.63 kb of genomic sequence from upstream of the zebrafish fgg gene transcription start site and cloned this region upstream of EGFP and the SV40 polyadenylation signal. Further details and oligonucleotides sequences used in this construction are available upon request. Tol2 transposase mRNA was in vitro transcribed with SP6 RNA polymerase from NotI-linearized pCS-TP,28 using the mMessage mMachine Kit (Ambion).

AB strain zebrafish were raised and bred in standard conditions and embryos were obtained from natural crosses. A license for experimentation with zebrafish was obtained from the local veterinary authority. One- or two-cell embryos were microinjected with 1 nL of injection solutions composed of 35 ng/μL transposase mRNA, 25 ng/μL reporter gene plasmid, and 0.075% phenol red essentially as described by Fisher et al.29 G0 embryos were observed daily using a Leica MZ16FA fluorescence stereomicroscope and photographed at room temperature using a Leica DFC340FX digital camera (black and white) and Leica software LAF 2.1. Some G0 embryos were raised to reproductive age and crossed with control fish. Expression of EGFP was then assessed in G1 embryos up to 8 days postfertilization (dpf).

Whole mount in situ hybridization of zebrafish embryos

Two dpf G1 transgenic or control embryos were fixed, depigmented, permeabilized, hybridized with DIG-labeled RNA probes, and developed for imaging essentially as described by Thisse and Thisse.30 Digoxigenin (DIG)–labeled sense and anti-sense EGFP RNA probes were synthesized by in vitro transcription with SP6 and T7 RNA polymerases (both from Promega) from a linearized pCRII TOPO (Invitrogen) plasmid containing the complete EGFP open reading frame with promoter sequences flanking either side of the insert. Minor protocol changes, compared with Thisse and Thisse,30 included probe hybridization at 60°C, and prehybridization, hybridization, and posthybridization washing steps made in 2-mL tubes rather than immersed nylon baskets. Before imaging, embryos were progressively washed in 25%, 50%, and 75% methanol in phosphate-buffered saline, 100% methanol, and then clarified in 100% glycerol. Images were obtained at room temperature using a Leica DFC420 digital camera and software LAS 2.8.1.

Human sequence cloning and generation of transgenic mice

CNC12 was PCR amplified from human genomic DNA (Clontech), sequence-validated, and cloned into a Gateway compatible Hsp68-LacZ reporter vector31 (primers used for amplification: FgCNC12F: CCTCAATTTTCCATTAGCAA; FgCNC12R: AGGAAAGCAGTATCGTGAAG).

Transgenic mice were generated as previously described32 in accordance with protocols approved by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Mouse embryo staining

A total of 66 embryos were harvested at embryonic day (E)14.5. Abdominal cavities were opened to facilitate reagent penetration of the liver. Embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution and subsequently incubated in staining solution (0.8 mg/mL X-gal [5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-beta-D-galacto-pyranoside], 4mM potassium ferrocyanide, 4mM potassium ferricyanide, and 20mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane] pH 7.5) for 24 hours at room temperature. Images were obtained at room temperature in phosphate-buffered saline using a Leica MZ16 light microscope at magnification 1.6× with a Leica DFC420 camera. Adobe Photoshop Elements was used as acquisition software.

Results

Selection of potential regulatory CNCs within the fibrinogen syntenic genomic landscape

The human fibrinogen gene cluster is located within a syntenic region of ≈215 kb (assembly NCBI36/hg18: Chr4: 155 675 587-155 891 061) conserved from human to frog (Xenopus tropicalis).25 This conserved blocks of synteny (CBS) is constituted of the pleiotropic regulator 1 (PLRG1) gene at the centromeric end, the 50-kb fibrinogen cluster, a gene desert region of ≈131 kb and the lecithin retinol acyltransferase (LRAT) gene at the telomeric end. Using a multispecies alignment tool (rVISTA),33 we searched for sequences defined by a minimum length of 100 bp and at least 70% homology with the mouse sequence. We also considered the presence of PhastCons conserved elements34 as well as the evolutionary and sequence pattern extraction through reduced representations regulatory potential.35 With these criteria, we selected 14 sequences (CNC1 to CNC14) localized within the syntenic landscape of the human fibrinogen locus (Figure 1A and supplemental Table 1) as candidates for regulatory elements of the fibrinogen locus. These sequences are all located in the CBS, except for CNC1 that is located 41-kb centromeric to FGB. We selected CNCs within the fibrinogen cluster (intronic, in promoter regions or intergenic) as well as CNCs outside the cluster. CNC2 and CNC4 were chosen due to their particular localizations (ie, partly overlapping the FGB and FGG proximal promoters, respectively). The lesser conserved CNC5 and CNC8 were selected due to their high evolutionary and sequence pattern extraction through reduced representations regulatory potential pattern. The 14 selected sequences do not show an homology greater than 78% with the mouse sequence, and are not deeply conserved throughout vertebrates; CNC13 and CNC14 are the most conserved with homologies greater than 70% in a human-chicken alignment.

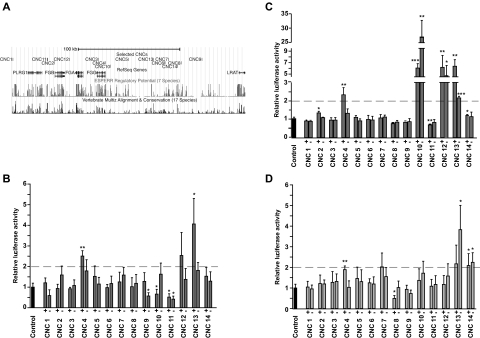

Figure 1.

Screen of 14 CNCs using in vitro luciferase enhancer assay. (A) The University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser representation of the fibrinogen cluster genomic region (NCBI36/hg18; Chr4: 155 661 000-155 891 000) is shown. The localization of the 14 selected CNCs as well as the fibrinogen genes (FGA, FGB, and FGG) and the nearby genes (PLRG1 and LRAT) present in the syntenic vicinity are schematically represented as well as the regulatory potential and the conservation feature. Luciferase assay was performed for 14 CNCs on 3 cell lines (B) HepG2, (C) Huh7, and (D) HEK-293T in both genomic orientations (+ and − strands). Luciferase activities normalized with a control plasmid (Control) are plotted. The gray dashed line represents a 2-fold threshold above which we consider that the tested sequence shows enhancer activity. Error bars show standard deviation; P values were calculated from experimental data versus values for control plasmid condition (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, 2-sided t test, n = 3).

In vitro screening for hepatocyte-specific regulatory sequences

The regulatory potential of the 14 selected CNC sequences was tested in vitro using a luciferase-based reporter assay. Their putative role in controlling hepatic-specific fibrinogen transcription was monitored by assaying them in 2 fibrinogen-expressing hepatoma cell lines (Huh7 and HepG2) versus a nonfibrinogen-expressing cell line (HEK-293T). The orientation-dependent regulatory function of each CNC was studied by cloning and assaying both orientations (see “In vitro enhancer assays using luciferase gene reporter plasmids”). For this purpose, we cloned short sequences (348 bp in average, SD 140 bp), without flanking genomic sequences. These constructs were transiently transfected in the 3 cell lines tested. The regulatory potential of each CNC was determined by normalization to the basal transcriptional activity of the backbone luciferase plasmid (Figure 1). Of the 2 sequences overlapping promoter regions, only CNC4 showed activity, interestingly in all 3 cell lines. CNC13 shows enhancer potential (relative luciferase activity above 2) in all 3 cell lines in both orientations, as might be expected for enhancer elements that are not orientation dependent.13,36,37 CNC12 shows enhancer potential exclusively in hepatoma cell lines. CNC10 showed enhancer activity in HuH7 cells, but not in HepG2 cells where we observed inconsistent luciferase activities when comparing CNC10 orientations. Finally, taking into account a cutoff value of relative luciferase activity at or below 0.5 for both orientations for repressor activity, we found that CNC11 shows repressor activity in HepG2 cells, a lesser effect in HuH7 cells, and no activity in embryonic kidney cells.

In summary, the in vitro screen of 14 conserved sequences revealed 4 putative regulatory elements, of which 2 are potential hepatocyte enhancers (CNC10 and CNC12), and 1 is a potential hepatocyte repressor (CNC11).

In vivo reporter gene assays in zebrafish embryos

To evaluate the regulatory potential in vivo and assess the spatiotemporal enhancer activity of CNC4, CNC10, CNC12, and CNC13 (Figure 2), we performed in vivo EGFP reporter assays in zebrafish embryos. If these 4 sequences are indeed implicated in the tissue-specific expression of the fibrinogen genes, they should drive liver expression of the reporter gene. The human sequences of CNC4, CNC10, CNC12, and CNC13 were cloned upstream of a minimal promoter and EGFP in a Tol2 transposase gene transfer plasmid. A negative control without a CNC sequence was used to evaluate the background expression of the EGFP encoding vectors. We also used as positive control a construct with EGFP downstream of a 1.63-kb zebrafish fgg promoter. These constructs were individually comicroinjected with capped Tol2 transposase mRNA in zebrafish embryos, resulting in mosaic transgenic animals (G0). Embryos were regularly observed and at 5 dpf, 25 to 55 embryos per reporter construct were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Table 1). We observed reproducible EGFP expression patterns for each reporter construct (Figure 3A). The negative control construct (carrying no CNC) gave weak scattered EGFP-positive somite muscle cells. This weak muscle signal was sparsely observed for all 5 constructs. The majority of CNC4- and CNC10-injected embryos showed EGFP expression in the yolk sac (24/25 and 41/42, respectively), and a single individual per construct showed weak expression in the liver. Surprisingly, more than half of the CNC13 embryos did not show any GFP expression, and the other half showed weak expression in muscle cells or in the yolk. In contrast, CNC12 showed EGFP expression in the liver for 50% (18/36) of injected embryos. This rate is comparable with fish injected with a positive control plasmid, carrying EGFP under the control of the zebrafish fgg promoter (70% EGFP-positive livers).

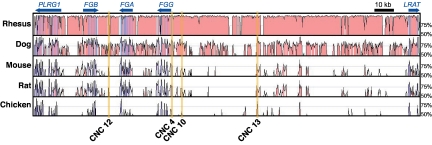

Figure 2.

Localization and conservation of in vitro selected CNCs. mVISTA plot comparing the human reference sequence with orthologous sequences from 5 vertebrates (window shown 215 kb). Orange-highlighted regions designate CNC sequences that were capable of driving luciferase 2-fold compared with the control plasmid (see Figure 1). Colored peaks indicate sequence conservation of 70% identity across 100 nucleotides (red, noncoding; blue, exons).

Table 1.

Enhancer assay in G0 fish embryos

| Construct | No. of embryos | No. GFP negative | Percent liver positive (no.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control plasmid | 55 | 9 | 0 |

| fgg promoter | 27 | 0 | 70.4 (19) |

| CNC 4 | 25 | 0 | 4.2 (1) |

| CNC 10 | 42 | 0 | 2.4 (1) |

| CNC 12 | 36 | 4 | 50.0 (18) |

| CNC 13 | 30 | 16 | 0 |

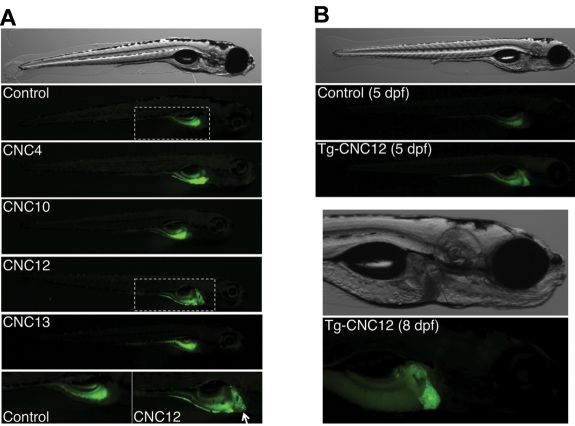

Figure 3.

In vivo enhancer assay using EGFP reporter constructs in zebrafish embryos. (A) Representative mosaic G0 animals, at 5 dpf, for 5 EGFP reporter constructs (CNC4, CNC10, CNC12, and CNC13) as well as for the control plasmid carrying no CNC sequences (Control). The 2-bottom pictures are higher magnification of the areas defined by dashed line of Control and CNC12 constructs, the last one driving EGFP expression in liver (white arrow). (B) CNC12-EGFP and control transgenic representative G1 animals at 5 dpf. Higher magnification of an 8-dpf CNC12-EGFP transgenic individual depicts clear liver expression of the reporter gene. Embryos are shown in lateral view, anterior to the right in all panels.

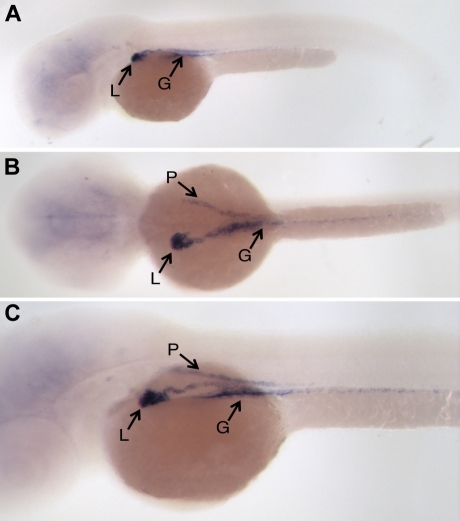

To confirm that our observations made on G0 embryos were not due to an insertion site bias or episomal expression of the CNC-EGFP transgene, we analyzed EGFP expression in transgenic progeny descending from 2 different CNC12 founders. For this purpose, a group of CNC12-injected embryos were raised to reproductive age and crossed with wild-type fish. EGFP expression in their transgenic progeny was analyzed during the first week of development. EGFP expression was not observed during the first day of transgenic G1 embryo development. During the second day EGFP was seen in the presumptive gut and liver primordium. The liver EGFP signal became more evident as liver development progressed through 5 to 8 dpf (Figure 3B). The EGFP pattern observed at 8 dpf is very similar to that seen in transgenic fish carrying the EGFP gene under the control of the zebrafish fgg promoter (R.J.F., M.N.-A., unpublished data). Finally, to distinguish the EGFP expression driven by the CNC12 from the strong auto-fluorescence of the zebrafish embryo yolk sac, we performed in situ hybridizations with DIG-labeled EGFP RNA probes to clearly define the EGFP expression pattern in 2 dpf transgenic animals. Wild-type embryos and sense RNA probes were used as negative controls. EGFP mRNA was clearly and specifically detected in the developing gut, pronephros, and liver bud (Figure 4), a pattern of expression reminiscent of that of the zebrafish CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha (C/EBPα).38

Figure 4.

EGFP in situ hybridization of CNC12-EGFP transgenic fish embryos. (A) Lateral, (B) dorsal, and (C) oblique views of representative 2-dpf CNC12-EGFP G1 embryos show EGFP expression in liver (L), gut (G), and also in the pronephros ducts (P). Embryos are shown anterior to the left in all panels.

In summary, our in vivo reporter gene assay in transgenic zebrafish embryos demonstrates that CNC12 drives the robust liver expression of a transgene.

In vivo reporter gene assays in mouse embryos

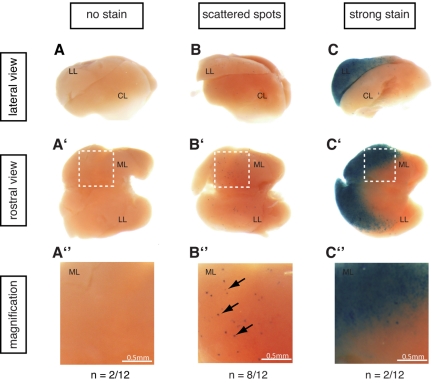

To confirm the in vivo liver activity of CNC12 in a mammalian model system, we performed a transgenic reporter gene assay in mouse embryos. Human CNC12 was cloned upstream of an Hsp68 minimal promoter driving the activity of a LacZ reporter gene. The linearized vector was used to generate transgenic embryos by pronuclear microinjection. A total of 66 embryos were collected at E14.5. Of the 66 embryos, 12 were transgenic as assessed by LacZ staining. Of these 12 embryos resulting from independent transgenic integration events, 10 showed staining in the liver. In most cases, liver staining was confined to individual scattered cells (8/10), whereas in 2 cases we observed strong staining in the median and left lobes that did not extend into other regions of the liver (Figure 5 and supplemental Figure 2). Of note, the mRNA expression patterns of the Fga, Fgb, and Fgg genes at E14.5 do not exhibit such a scattered or lobe-specific appearance (Visel et al39 and www.eurexpress.org). There are at least 2 plausible explanations for the partial overlap in the pattern of expression of the fibrinogen genes and CNC12. First, additional enhancers may map within the locus and the coordinated action of all of these enhancers may be necessary to recapitulate the full fibrinogen gene expression pattern. Second, the activity of CNC12 in our in vivo assay may be weakened due to its integration site (positional effect) or by the absence of flanking sequences in the construct used for this experiment.

Figure 5.

CNC12 activates transcription in the mouse E14.5 liver. Twelve embryos resulting from Hsp68CNC12 LacZ transgenesis showed blue staining in the liver or other structures, indicating successful transgene integration. The livers of these 12 embryos were dissected and pictures from lateral (a-c) and rostral (a'-c') views were taken for each of them (1 representative liver is shown per group; see supplemental Figure 2 for the complete set). As shown in panel a-a″, b-b″, and c-c″, 3 groups could be detected within the 12 transgenics embryos: (a-a″) embryos with no lacZ transcriptional activation in the liver (n = 2), (b-b″) embryos with scattered blue spots specifically in the liver (n = 8), and (c-c″) embryos exhibiting a strong staining in the median and left lobes of the liver (n = 2). Panel a″-c″ are magnifications of the median lobe of each of the representative livers (white boxed region in each of the liver from a'-c' panel). LL: left lobe, CL: caudate lobe, ML: median lobe.

Discussion

In this study, we provide both in vitro and in vivo evidence for the liver enhancer activity of a noncoding sequence, CNC12, located within the human fibrinogen cluster. Our data show that CNC12, a 340-bp element located between FGB (6.1 kb upstream) and FGA (7.7 kb downstream), is sufficient to drive liver expression of reporter genes in human hepatoma cells, in zebrafish embryos and in mouse embryos.

Identification of this novel enhancer sheds light on the regulation of the fibrinogen cluster because it is the first liver-active regulatory sequence to be identified in the 50-kb cluster outside of the well-known 5′-proximal promoters of FGA, FGB, and FGG. While additional experiments are necessary to formally prove the role of CNC12 in the regulation of fibrinogen, considering the specific liver activity of CNC12 and its position within the conserved block of synteny of the fibrinogen genes, it seems justified to suggest that CNC12 is involved in the gene expression control of the fibrinogen genes, both in zebrafish and mouse embryos, but also in humans. Due to its distinctive intergenic localization, CNC12 may be involved in the global coregulation of the 3 fibrinogen genes that is still not fully understood. Interestingly, a hyperfibrinogenemic mouse model was recently obtained by multiple insertions of a 80- to 100-kb transgene containing the complete mouse fibrinogen locus.40 The expression of the exogenous fibrinogen genes imitated perfectly the endogenous liver-specific transcription pattern, suggesting that all the essential regulatory sequences mediating the tissue-specificity were present within the fibrinogen cluster.

Enhancers activate transcription, often in a temporally and tissue-restricted manner, mainly by acting on promoters.41 Some authors have suggested that regulatory sequences are kept in the vicinity of their target gene(s) due to evolutionary pressure restraining recombination events between regulatory elements and target genes, ultimately leading to the formation of conserved blocks of synteny.25,26

Of great interest to this study, CNC12 has binding sites for 2 important liver transcription factors.42 Indeed, high-resolution chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, combining ChIP with high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq),43 have defined all loci interacting with C/EBPα and HNF4α in liver samples from organisms representing 5 vertebrate orders (human, mouse, dog, short-tailed opossum, and chicken).44 In absolute correlation with our data, C/EBPα and HNF4α were found to bind to sequences within human CNC12 (supplemental Figure 1). In addition, in situ hybridization performed for cebpa (Zebrafish Information Network identification: ZDB-IMAGE-040107-415)38 and hnf4a (Zebrafish Information Network identification: ZDB-IMAGE-080403-438)45 in zebrafish embryos depict very similar patterns to those we obtained for our CNC12-EGFP transgenic animals (Figure 4). Altogether, these ChIP-seq experiments, in situ hybridizations, and our data allow us to speculate that CNC12 liver activity is mediated through interactions with C/EBPα and HNF4α transcription factors.

Of the 14 sequences that we tested in vitro, CNC12 is not among the most conserved. Although it is commonly observed that deep phylogenetic conservation increases the likelihood of regulatory function,31,46 moderately conserved regulatory sequences probably represent a group of more recently developed enhancers.47 It has been proposed that comparisons of orthologous sequences from multiple closely related species may be a more sensitive and accurate approach for the identification of vertebrate regulatory sequences rather than focusing on deeply conserved regions.48 Indeed, regulatory noncoding sequences conserved only within mammals have been shown experimentally to be functional.21 The conservation pattern of CNC12 shows 4 PhastCons elements34 that are modestly conserved among 17 vertebrates (Figure 2), suggesting a recently developed mammalian-specific enhancer. This feature raises questions regarding the liver activity we observed in fish. Two hypotheses could explain the activity of a modestly conserved human element in the fish assay system: either the sequence important for transcription factor binding and enhancer activity is very short and although conserved between vertebrates is simply not identifiable; or the critical transcription factor binding sites show sequence plasticity and the fish transcription factors are able to recognize human binding sites.

The identification of an enhancer likely to be involved in the transcriptional regulation of fibrinogen gene expression reveals a further potential source of the large variability in circulating fibrinogen levels seen among healthy people. Indeed, in addition to posttranscriptional regulation by microRNAs,49 environmental factors,6 modifier genes,50 genetic variation within the 5′-proximal promoter or coding sequences, polymorphisms in more distant enhancers should be taken into consideration. As C/EBPα and/or HNF4α bind CNC12 in hepatocytes, and may therefore contribute to fibrinogen regulation, genetic variants affecting these transcription factors should also be taken into consideration. Subtle variations in upstream regulator expression may impact on fibrinogen production, affecting the interactions between promoters and distant enhancers. Therefore, variability in fibrinogen levels could be explained by perturbation at several levels of transcriptional regulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Luciana Romano and Corinne Di Sanza for technical assistance and Professor Koichi Kawakami (National Institution of Genetics, Shizuoka, Japan) for providing Tol2 transposon system plasmids.

This work was supported by grants from the Dr Henri Dubois-Ferrière-Dinu Lipatti foundation and the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 31-A0119845). A.V. and C.A. were supported by grant HG003988 funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute and Department of Energy Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231, University of California, Energy Office Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. C.A. is also supported by an European Molecular Biology Organization long-term fellowship.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: A.F. designed and performed in silico analyses and in vitro experiments; R.J.F. designed and performed experiments with zebrafish; C.A. helped with the in silico analyses and designed and performed experiments with mice; R.D. provided expertise for the zebrafish experiments; A.V. designed the mouse experiments; M.N.-A. designed and directed the project; A.F., R.J.F., and M.N.-A. wrote the manuscript; and C.A., R.D., and A.V. edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marguerite Neerman-Arbez, Department of Genetic Medicine and Development, 1 Rue Michel Servet, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland; e-mail: marguerite.neerman-arbez@unige.ch.

References

- 1.Folsom AR. Hemostatic risk factors for atherothrombotic disease: an epidemiologic view. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(1):366–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamath S, Lip GY. Fibrinogen: biochemistry, epidemiology and determinants. QJM. 2003;96(10):711–729. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collet JP, Allali Y, Lesty C, et al. Altered fibrin architecture is associated with hypofibrinolysis and premature coronary atherothrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(11):2567–2573. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000241589.52950.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danesh J, Collins R, Peto R, Lowe GD. Haematocrit, viscosity, erythrocyte sedimentation rate: meta-analyses of prospective studies of coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2000;21(7):515–520. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danesh J, Lewington S, Thompson SG, et al. Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;294(14):1799–1809. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.14.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaptoge S, White IR, Thompson SG, et al. Associations of plasma fibrinogen levels with established cardiovascular disease risk factors, inflammatory markers, and other characteristics: individual participant meta-analysis of 154,211 adults in 31 prospective studies: the fibrinogen studies collaboration. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(8):867–879. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green FR. Fibrinogen polymorphisms and atherothrombotic disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;936:549–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voetsch B, Loscalzo J. Genetic determinants of arterial thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(2):216–229. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000107402.79771.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuller GM, Zhang Z. Transcriptional control mechanism of fibrinogen gene expression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;936:469–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courtois G, Baumhueter S, Crabtree GR. Purified hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 interacts with a family of hepatocyte-specific promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(21):7937–7941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen LP, Crabtree GR. Regulation of the HNF-1 homeodomain proteins by DCoH. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3(2):246–253. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90030-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Calle-Mustienes E, Feijoo CG, Manzanares M, et al. A functional survey of the enhancer activity of conserved non-coding sequences from vertebrate Iroquois cluster gene deserts. Genome Res. 2005;15(8):1061–1072. doi: 10.1101/gr.4004805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maston GA, Evans SK, Green MR. Transcriptional regulatory elements in the human genome. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:29–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nobrega MA, Ovcharenko I, Afzal V, Rubin EM. Scanning human gene deserts for long-range enhancers. Science. 2003;302(5644):413. doi: 10.1126/science.1088328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall H, Studer M, Popperl H, et al. A conserved retinoic acid response element required for early expression of the homeobox gene Hoxb-1. Nature. 1994;370(6490):567–571. doi: 10.1038/370567a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aparicio S, Morrison A, Gould A, et al. Detecting conserved regulatory elements with the model genome of the Japanese puffer fish, Fugu rubripes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(5):1684–1688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher S, Grice EA, Vinton RM, Bessling SL, McCallion AS. Conservation of RET regulatory function from human to zebrafish without sequence similarity. Science. 2006;312(5771):276–279. doi: 10.1126/science.1124070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prabhakar S, Poulin F, Shoukry M, et al. Close sequence comparisons are sufficient to identify human cis-regulatory elements. Genome Res. 2006;16(7):855–863. doi: 10.1101/gr.4717506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pennacchio LA, Loots GG, Nobrega MA, Ovcharenko I. Predicting tissue-specific enhancers in the human genome. Genome Res. 2007;17(2):201–211. doi: 10.1101/gr.5972507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin JT, Priest JR, Ovcharenko I, et al. Human-zebrafish non-coding conserved elements act in vivo to regulate transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(17):5437–5445. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grice EA, Rochelle ES, Green ED, Chakravarti A, McCallion AS. Evaluation of the RET regulatory landscape reveals the biological relevance of a HSCR-implicated enhancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(24):3837–3845. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pennacchio LA, Rubin EM. Genomic strategies to identify mammalian regulatory sequences. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2(2):100–109. doi: 10.1038/35052548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davidson EH, Erwin DH. Gene regulatory networks and the evolution of animal body plans. Science. 2006;311(5762):796–800. doi: 10.1126/science.1113832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleinjan DA, van Heyningen V. Long-range control of gene expression: emerging mechanisms and disruption in disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76(1):8–32. doi: 10.1086/426833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahituv N, Prabhakar S, Poulin F, Rubin EM, Couronne O. Mapping cis-regulatory domains in the human genome using multi-species conservation of synteny. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(20):3057–3063. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackenzie A, Miller KA, Collinson JM. Is there a functional link between gene interdigitation and multi-species conservation of synteny blocks? Bioessays. 2004;26(11):1217–1224. doi: 10.1002/bies.20117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urasaki A, Morvan G, Kawakami K. Functional dissection of the Tol2 transposable element identified the minimal cis-sequence and a highly repetitive sequence in the subterminal region essential for transposition. Genetics. 2006;174(2):639–649. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.060244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawakami K, Takeda H, Kawakami N, Kobayashi M, Matsuda N, Mishina M. A transposon-mediated gene trap approach identifies developmentally regulated genes in zebrafish. Dev Cell. 2004;7(1):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fisher S, Grice EA, Vinton RM, et al. Evaluating the biological relevance of putative enhancers using Tol2 transposon-mediated transgenesis in zebrafish. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(3):1297–1305. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thisse C, Thisse B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(1):59–69. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pennacchio LA, Ahituv N, Moses AM, et al. In vivo enhancer analysis of human conserved non-coding sequences. Nature. 2006;444(7118):499–502. doi: 10.1038/nature05295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poulin F, Nobrega MA, Plajzer-Frick I, et al. In vivo characterization of a vertebrate ultraconserved enhancer. Genomics. 2005;85(6):774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loots GG, Ovcharenko I, Pachter L, Dubchak I, Rubin EM. rVista for comparative sequence-based discovery of functional transcription factor binding sites. Genome Res. 2002;12(5):832–839. doi: 10.1101/gr.225502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siepel A, Bejerano G, Pedersen JS, et al. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 2005;15(8):1034–1050. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King DC, Taylor J, Elnitski L, Chiaromonte F, Miller W, Hardison RC. Evaluation of regulatory potential and conservation scores for detecting cis-regulatory modules in aligned mammalian genome sequences. Genome Res. 2005;15(8):1051–1060. doi: 10.1101/gr.3642605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee TI, Young RA. Transcription of eukaryotic protein-coding genes. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:77–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banerji J, Rusconi S, Schaffner W. Expression of a beta-globin gene is enhanced by remote SV40 DNA sequences. Cell. 1981;27(2 Pt 1):299–308. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thisse B, Pflumio S, Fürthauer M, et al. Expression of the zebrafish genome during embryogenesis (NIH R01 RR15402). ZFIN Direct Data Submission. 2001 ( http://zfin.org) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Visel A, Thaller C, Eichele G. GenePaint.org: an atlas of gene expression patterns in the mouse embryo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D552–556. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh029. (Database issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gulledge AA, Rezaee F, Verheijen JH, Lord ST. A novel transgenic mouse model of hyperfibrinogenemia. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(2):511–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Visel A, Rubin EM, Pennacchio LA. Genomic views of distant-acting enhancers. Nature. 2009;461(7261):199–205. doi: 10.1038/nature08451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hatzis P, Kyrmizi I, Talianidis I. Mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated disruption of enhancer-promoter communication inhibits hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(19):7017–7029. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00297-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt D, Wilson MD, Spyrou C, Brown GD, Hadfield J, Odom DT. ChIP-seq: using high-throughput sequencing to discover protein-DNA interactions. Methods. 2009;48(3):240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt D, Wilson MD, Ballester B, et al. Five-vertebrate ChIP-seq reveals the evolutionary dynamics of transcription factor binding. Science. 2010;328(5981):1036–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.1186176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thisse C, Thisse B. Expression from: unexpected novel relational links uncovered by extensive developmental profiling of nuclear receptor expression. ZFIN Direct Data Submission. 2008 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030188. ( http://zfin.org) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Attanasio C, Reymond A, Humbert R, et al. Assaying the regulatory potential of mammalian conserved non-coding sequences in human cells. Genome Biol. 2008;9(12):R168. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-12-r168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boffelli D, McAuliffe J, Ovcharenko D, et al. Phylogenetic shadowing of primate sequences to find functional regions of the human genome. Science. 2003;299(5611):1391–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1081331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Margulies EH, Blanchette M, Haussler D, Green ED. Identification and characterization of multi-species conserved sequences. Genome Res. 2003;13(12):2507–2518. doi: 10.1101/gr.1602203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fort A, Borel C, Migliavacca E, Antonarakis SE, Fish RJ, Neerman-Arbez M. Regulation of fibrinogen production by microRNAs. Blood. 2010;116(14):2608–2615. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-268011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dehghan A, Yang Q, Peters A, et al. Association of novel genetic Loci with circulating fibrinogen levels: a genome-wide association study in 6 population-based cohorts. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2(2):125–133. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.825224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.