Abstract

Adult stem cells must balance self-renewal and differentiation for tissue homeostasis. The Drosophila ovary has provided a wealth of information about the extrinsic niche signals and intrinsic molecular processes required to ensure appropriate germline stem cell renewal and differentiation. The factors controlling behavior of the more recently identified follicle stem cells of the ovary are less well-understood but equally important for fertility. Here we report that translational regulators play a critical role in controlling these cells. Specifically, the translational regulator Caprin (Capr) is required in the follicle stem cell lineage to ensure maintenance of this stem cell population and proper encapsulation of developing germ cells by follicle stem cell progeny. In addition, reduction of one copy of the gene fmr1, encoding the translational regulator Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein, exacerbates the Capr encapsulation phenotype, suggesting Capr and fmr1 are regulating a common process. Caprin was previously characterized in vertebrates as Cytoplasmic Activation/Proliferation-Associated Protein. Significantly, we find that loss of Caprin alters the dynamics of the cell cycle, and we present evidence that misregulation of CycB contributes to the disruption in behavior of follicle stem cell progeny. Our findings support the idea that translational regulators may provide a conserved mechanism for oversight of developmentally critical cell cycles such as those in stem cell populations.

Introduction

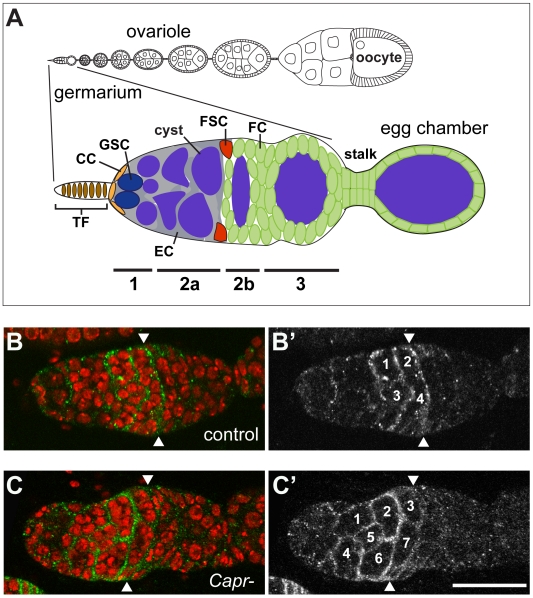

Distinct stem cell populations within the ovary produce the different cell types that must act coordinately to create a functional egg. The Drosophila ovary has proved an extremely fruitful model system to study this process (reviewed in [1]). Two stem cell populations have been identified: the germline stem cells (GSCs), and the follicle stem cells (FSCs), which reside at the anterior of the ovariole in a structure called the germarium (Figure 1A). The GSCs give rise to the invariant 15 nurse cells and single oocyte comprising a cyst. Two FSCs produce all of the different types of somatic cells that surround the cysts and connect the developing egg chambers. During development, a cyst progresses through four morphologically and functionally distinct regions of the germarium: 1, 2a, 2b and 3 ([2] and Figure 1A). Region 1 houses the GSCs and escort cells [3], [4], [5]. Here, GSCs divide to produce another GSC (self renewal) and a cystoblast that undergoes four synchronous divisions to produce a 16-cell cyst [6]. As cysts develop, cellular processes from the escort cells surround them in regions 1 and 2a of the germarium and help move the cysts through this region [3], [7]. Two FSCs reside at the border of regions 2a and 2b and produce the follicle cells, stalk cells, and other somatic cells associated with a developing egg chamber [8], [9], [10]. Once a cyst is encapsulated it buds off from the germarium forming a stage 1 egg chamber. Production of a functional egg requires proper control of proliferation and differentiation of both stem cell populations and their progeny.

Figure 1. Loss of Capr disrupts germline cyst development.

A) Schematic of the Drosophila germarium with bars below indicating the numbered germarium regions (1, 2a, 2b, 3) and their cell types: non-proliferating terminal filament (TF) and cap cells (CC), germline stem cells (GSC) which give rise to the developing 16-cell cysts (cyst), escort cells (EC) which facilitate movement of cysts through regions 1 and 2a, and the follicle stem cells (FSC) which give rise to the follicle cells (FC) and stalk. Anterior is to the left in all figures. B-C) Immunofluorescence analysis of control +/Df(3L)Cat (B, B’) or Capr2/Df(3L)Cat (C, C’) germaria stained with antibodies to Slit (green and B’, C’) and TO-PRO-3 iodide (DNA, red). Arrowheads indicate the position of FSCs and the unencapsulated cysts are numbered in B’ and C’. Scale bar is 30 microns.

Stem cell activity is controlled by intrinsic and extrinsic factors, which operate in the context of specialized microenvironments, stem cell niches (reviewed in [1], [11]). Much is known about the molecular mechanisms regulating GSCs and their role in producing a functional egg (reviewed in [1]). For example, GSCs are found in a cellular niche at the anterior of the germarium. They are anchored to the cap cells via DE-cadherin, and loss of this adhesion leads to loss of stem cell properties [12]. In their niche, GSCs receive extrinsic signals, such as Dpp, from cap cells, that maintain their stem cell identity and prevent differentiation [13], [14]. Numerous intrinsic factors have also been identified that control GSC proliferation and differentiation and comprise a variety of molecular mechanisms. Prominent among them are proteins involved in translational regulation such as the eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4A and the translational regulators Pumilio, Nanos, and Vasa, [15], [16], [17], [18], [19] and components of the microRNA pathway [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. In addition, GSC self-renewal and differentiation rely on chromatin modifiers which influence transcriptional regulation [25], [26]. Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors ensure that GSCs remain in an undifferentiated state while in their niche, yet continue to produce daughter cells that form the invariant 16-germ cells of each cyst.

Significantly less is known about the regulation of the FSCs. While FSCs also require cell adhesion proteins to maintain their stem cell identity, in this case DE-cadherin and integrins [12], [27], the cellular nature of the FSC niche is poorly understood. Recent work has suggested that each FSC may maintain contact with a single escort cell [7] however, the full complement of cells that comprise the FSC niche remains uncertain (reviewed in [1]). Like GSCs, FSCs also receive extrinsic signals controlling their proliferation and differentiation. These include long-range Hh and Wg signals, which emanate from the cap cells, and short-range signals from escort cells [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]. Proteins modulating chromatin structure also appear to affect FSC self-renewal [25], [26], [34], [35]. To date, however, Dicer-1 is the only translational regulator identified as necessary for FSC maintenance or function [22]. Here, we report that the translational regulators Caprin (CAPR) and the Drosophila ortholog of Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP) function together in regulating the FSC lineage. In addition, we find that FSC-lineage cells have an altered cell cycle in Capr mutants, further implicating Capr in developmental regulation of the cell cycle.

Results

Loss of Capr Produces Defects in Germline Cyst Packaging and Stalk Morphology

During our previous study [36] it was noted that Capr- females that were heterozygous for the fmr1 gene (Df(3L)Cat fmr13/Capr2) had reduced fecundity that decreased further with age (Figure S1). fmr1 had been previously reported to have an extrinsic role in ovarian germline stem cell (GSC) maintenance [24], [37]. However, no germline phenotype was observed in heterozygous fmr1 mutant ovaries, suggesting that the reduction of fecundity in Df(3L)Cat fmr13/Capr2 females was caused by loss of Capr or a combined requirement for Capr and fmr1 in maintaining ovary function. To explore this possibility, ovaries from Capr null females were dissected and examined for morphological defects that could explain the contribution of Capr to the reduced fecundity. Initial observations indicated that Capr2/Df(3L)Cat mutant (hereafter referred to as Capr-) germaria were often swollen-looking and appeared to contain too many cells in region 2a. This phenotype could arise through hyperproliferation of cells within each cyst, or a local overabundance of morphologically normal cysts. Staining for the extracellular matrix protein Slit, which identifies escort and follicle cells in regions 2a and 2b of the germarium [10], revealed that compared to controls (Figure 1B, B’), there are an inappropriately high number of morphologically normal 16-cell cysts in 86% of Capr- germaria (Figure 1C, C’, and Table 1). Cyst production is controlled by proliferation and differentiation of GSC-lineage cells, while the follicle stem cell lineage is responsible for encapsulating cysts and mediating their exit from the germarium. The accumulation of cysts in region 2a of Capr- germaria could be due, therefore, to defects in either lineage.

Table 1. Loss of Capr increases the number of unencapsulated germline cysts.

| Genotype | ≤5 cysts | >5 cysts | n |

| Df/+ | 71.9% | 28.1% | 82 |

| Capr2/Df | 14.4% | 85.6% | 104 |

| ptcS2/+ | 91.9% | 8.1% | 62 |

| ptcS2/+; Capr2/Df | 52.0% | 48.0% | 120 |

| wg1–12/+ | 91.2% | 8.8% | 57 |

| wg1–12/+; Capr2/Df | 0.0% | 100.0% | 111 |

| CycB2/+; Capr2/Df | 49.5% | 50.5% | 95 |

| Act5C-GAL4; UAS-CycB | 21.6% | 78.4% | 88 |

| fmr13/Df(3R)Exel6265 | 81.4% | 18.6% | 59 |

| Df, fmr13/Capr2 | 0.0% | 100.0% | 91 |

The percent of total germaria scored (n) containing the normal number of Slit-stained 16-cell cysts (≤5 cysts), or supernumerary 16-cell cysts (>5 cysts), is shown for each genotype. Df refers to the Capr deficiency, Df(3L)Cat.

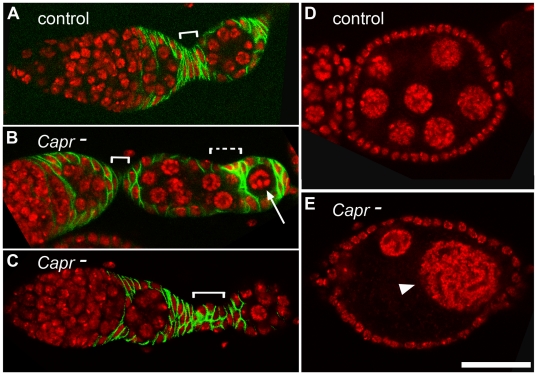

Examination of developing egg chambers revealed two additional defects in Capr mutant ovaries not observed in heterozygotes. First, a small portion of encapsulated egg chambers contained an inappropriate number of nuclei (Figure 2B, 2E, and Table S1). Occasionally, egg chambers were also observed that displayed heterogeneity in the size and presumed ploidy of the nuclei (Figure 2E) or portions of two cysts packaged into one egg chamber (data not shown). Similar defects have been reported for mutations in genes specifically affecting the FSC lineage [28], [29], [30], [32], [35], [38], but also resemble those attributed to GSC proliferation defects in fmr1 mutants [39], [40]. In addition to the packaging defects, we observed occasional aberrations in cell number and/or organization of the stalk cells connecting developing egg chambers of Capr- ovarioles (Figure 2, compare brackets in A-C). Because stalk cells are exclusively derived from FSCs this suggests that at a minimum, Capr function is required by the FSC lineage, but could play a role in both the FSC and GSC lineages.

Figure 2. Characterization of egg chamber and stalk defects in Capr- ovaries.

A-C) Germarium, budding egg chamber, and stalk (white bracket) of the indicated genotypes stained with antibodies to the follicle cell marker, FASIII (green), and with TO-PRO-3 iodide (red). A) Df(3L)Cat/+ (Control), B) Capr- showing a reduced primary stalk, and an aberrantly packaging egg chamber displaying an absence of stalk (dashed bracket) and misencapsulation of a single germline cell (arrow), and C) Capr- containing a disorganized stalk. D-E) Egg chambers stained for TO-PRO-3 (red). Optical sectioning revealed 16 nuclei in the control egg chamber (D), but fewer cells in a Capr- egg chamber (E) including nuclei of inappropriate size for this stage (arrowhead). Scale bar is 30 microns.

Capr is Specifically Required for Maintenance of Follicle Stem Cells

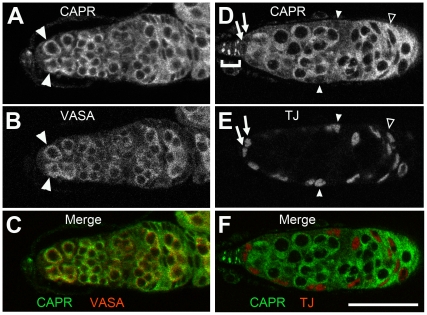

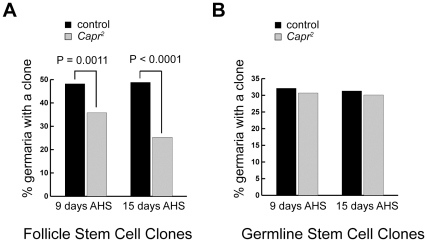

Caprin protein is found throughout all cells in the germarium. Using preabsorbed anti CAPR serum under conditions where staining is undetectable in Capr mutant ovaries (Figure S2) we observed relatively high CAPR expression in wild type ovaries in the GSC lineage, FSC lineage, and terminal filament compared to the cap cells and escort cells, where CAPR is barely detectable (Figure 3 and data not shown). To determine which lineage requires Capr function, we initially used the heat-shock-induced FLP/FRT method to generate marked homozygous Capr mutant clones in a heterozygous mutant female [41]. Mutant clones from either lineage showed no gross defects in size, morphology, or polarity as determined by immunostaining for Actin or the ß-catenin ortholog Armadillo (data not shown), suggesting that Capr is not required for anchoring FSC cells to their niche. During oogenesis, cells that are directly derived from an FSC division remain in the ovary for seven days. Following generation of Capr mutant clones, any Capr mutant cells detected in the ovary after seven days must be derived from a stem cell population that persisted after clone induction, while a reduction or absence of clones after seven days indicates a loss of the mitotically active stem cells [8]. The percentage of ovarioles containing either an FSC lineage clone or a GSC lineage clone was determined at various time points after clone induction. We found a statistically significant decrease in Capr mutant FSC-derived clones compared to the control (Figure 4A), and this difference increased with time after clone induction, indicating a progressive loss of mutant FSCs over time. In contrast, we observed no change in the frequency of Capr mutant GSC-derived clones compared to the control (Figure 4B). These results demonstrate that Capr is intrinsically required for FSC, but not GSC, maintenance. Since stalk cells and the follicle cells that encapsulate each cyst are derived from FSCs, all of the observed phenotypes are consistent with a role for Capr in both FSC maintenance and appropriate function of FSC progeny.

Figure 3. CAPR is present in both somatic and germline cells of the germarium.

Immunofluorescence analysis of wild type germaria indicates CAPR is present in cells identified by the germline marker VASA (A-C) including the GSCs (arrowheads in A, B), and in some of the somatic cells identified by the nuclear protein Traffic Jam (TJ) (D-F). CAPR is present in the FSC-derived follicle cells (open arrowhead, D, E), and as bright cytoplasmic puncta in differentiated terminal filament cells (bracket in D), but is barely visible in the cap cells (arrows in D, E), and escort cells (closed arrowheads in D, E). Scale bar is 30 microns.

Figure 4. Loss of Capr leads to loss of follicle stem cells but not germline stem cells.

The heat shock-FLP system was used to generate clones homozygous for the FRT80B (control) or for the FRT80B Capr2 (Capr2) chromosome. Percent germaria containing follicle stem cell clones (A), or germline stem cell clones (B) were quantified at 9 and 15 days after heat shock (AHS). The number of germaria analysed for 9 day and 15 day data respectively was 106 and 166 for control and 78 and 166 for Capr2.

Capr Specifically Regulates the Cell Cycle in the Follicle Stem Cell Lineage

The fates of stem cells and their progeny can be dramatically altered through changes in cell proliferation and cell cycle regulation [32], [42] and reviewed in [43]. FSC proliferation and differentiation are regulated by both wg and hh signals emanating from the cap cells at the tip of the germarium [28], [29], [32], [33]. We tested whether modulation of these signaling pathways could enhance or ameliorate the cyst packaging defects observed in Capr null germaria. A reduction in wg gene dosage, and consequent wg signaling, in a Capr mutant background caused a strong enhancement of the Capr- phenotype, such that all germaria contained supernumerary cysts in region 2a (Table 1). A similar reduction in ptc, which is expected to increase hh signaling and FSC proliferation [33], led to a reduction in supernumerary cysts in region 2a of Capr- germaria (Table 1). These results suggest that alterations in cell proliferation in the FSC lineage can specifically enhance or suppress the Capr- phenotype.

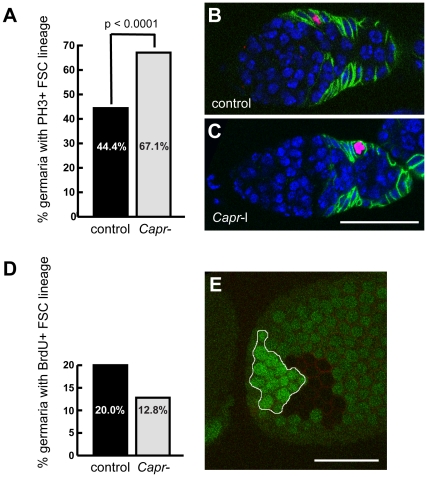

Because Capr has been implicated in cell cycle regulation in both Drosophila and vertebrate cells [36], [44], [45], we considered the possibility that Capr might directly regulate the cell cycle in ovarian stem cells and their progeny. We used two approaches to determine whether loss of Capr alters the cell cycle in the FSC lineage: phospho-histone H3 staining and BrdU incorporation. Phospho-histone H3 specifically labels mitotic chromosomes [46], and is generally used to identify cells that are undergoing mitosis. We observed a statistically significant increase in the percentage of fixed Capr- germaria containing FSC-lineage cells in mitosis compared to the control germaria (Figure 5A). These results indicate that FSC-lineage cells in Capr mutant germaria are either undergoing more cell divisions or they are spending more time in mitosis. If the FSC-derived cells are undergoing more divisions there should be an equivalent increase in the number of cells in other phases of the cell cycle. We identified cells in S-phase by pulse labeling with BrdU, a thymidine analog incorporated into DNA during S-phase [47]. The percentage of Capr- germaria containing FSC-lineage cells in S-phase was not increased relative to controls (Figure 5D), and was in fact slightly reduced, although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.09). This suggests that the defects found in Capr mutant ovaries are not due to alterations in overall proliferation rates, but are due to an alteration in lineage-specific cell cycle dynamics. Consistent with this interpretation, we did not find any striking differences in the overall size of the Capr- clones induced in heterozygotes compared to the simultaneously generated adjacent wild type clones (twin spots). This was true for clones observed in late stage egg chambers (Figure 5E) or recently induced within the germarium (data not shown). Together these data demonstrate that loss of Capr alters the cell cycle dynamics in the FSC lineage in a specific way, leading to prolonged mitosis but not an overall change in cycle length.

Figure 5. Loss of Capr alters cell cycle dynamics but not proliferation rates in the FSC lineage.

A-C) Fixed Df(3L)Cat/+ (control), or Df(3L)Cat/Capr2 (Capr-) germaria were stained with antibodies to phospho-histone H3 (red), and FasIII (green), and with TO-PRO-3 iodide (blue). A) Quantification of the % of germaria scored that showed any phospho-histone H3-positive staining in cells of the FSC lineage. The number of germaria analysed was 81 control, 82 Capr-. B-C) Examples of stained germaria of the indicated genotypes. Size bar is 30 microns. D) Quantification of the % of pulse labeled germaria scored that incorporated BrdU in cells of the FSC lineage. The difference between Df(3L)Cat/+ (control), or Df(3L)Cat/Capr2 (Capr-) was not significant (P = 0.09). The number of germaria analysed was 80 control, 86 Capr-. E) Tangential section of a fixed stage-10 egg chamber stained for GFP (green) and FasIII (red). The Capr- follicle cell clone (no GFP staining) and its adjacent wild-type twin-spot (bright green) are of similar size. Size bar is 60 microns.

Capr may Regulate CYCB Levels in the Follicle Stem Cell Lineage

CAPR is believed to act as a signal-dependent regulator of specific target mRNAs [36], [44], [48], [49]. In Drosophila, Capr modulates the translation of two mRNAs encoding cell cycle regulators during the mid-blastula transition: CycB and frs [36]. Of these known targets frs is not expressed in the germarium [50], [51], however, CycB is expressed in both the GSC and FSC lineage and is required for GSC divisions [52]. CYCB is a mitotic cyclin whose destruction is required to exit mitosis [53], making it a good candidate to mediate the alterations in the cell cycle we observe in Capr- ovarioles. Since CYCB levels oscillate during the cell cycle, we were unable to accurately compare CYCB levels directly by immunofluorescence. However, genetic manipulation of CYCB levels produced results consistent with a role for CYCB as an effector of the Capr- phenotype. Reducing the genetic dose of CycB in a Capr mutant background partially rescued the supernumerary cyst phenotype seen in Capr- germaria (Table 1) indicating that a critical level of CYCB is necessary to generate this phenotype. Furthermore, if the Capr- phenotype we observe is primarily due to an increase in CYCB, then overexpression of CYCB in a wild type ovary should also produce this phenotype. We tested this using Act5C-GAL4 and UAS-CycB transgenes to drive CycB expression in all FSC lineage cells (data not shown). Overexpression of CYCB led to a specific increase in the number of cysts present in region 2a (Table 1) as was seen in Capr- germaria. Furthermore, a small percentage of ovarioles had stalk cell defects when CYCB was overexpressed (data not shown) suggesting that most if not all aspects of the Capr mutant phenotype can be explained by misregulation of CycB.

fmr1 and Capr Coordinately Regulate the Follicle Stem Cell Lineage

Previously, our lab showed that CAPR and dFMRP bind and regulate expression of some of the same mRNAs, including CycB, and that loss of Capr in a fmr1 heterozygous background results in a more severe phenotype than loss of either gene alone ([36] and Figure S1). To date, fmr1 has been implicated only in the maintenance and differentiation of GSCs, but not FSCs [37], [39], [40], [54]. However, the reported effects of fmr1 on GSCs are not intrinsic, and dFMRP is expressed in somatic tissues, with the exception of the terminal filament cells which lack detectable dFMRP (data not shown, consistent with [37], [39]). We asked whether fmr1 might also play a role in the FSC-dependent packaging of cysts. Complete loss of fmr1 alone produced a minimal increase in unencapsulated cysts (18.6% of germaria showing >5 cysts in region 2a) compared to the 85.6% seen in Capr null germaria (Table 1). In a Capr mutant, however, even partial reduction of fmr1 generated unencapsulated cysts in 100% of the germaria (Table 1). Because loss of fmr1 has no effect on cyst production by GSCs [37] the genetic interaction between Capr and fmr1 suggests that Capr and fmr1 coordinately regulate cyst encapsulation by the FSC lineage.

Discussion

Stem cells are influenced by a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors instructing them to produce more stem cells and/or differentiating progeny (reviewed in [1], [11], [55]). Translational regulation has proven to be of fundamental importance in control of GSC identity and behavior, but surprisingly little is known about the relative importance of this mode of regulation in controlling the fate of FSCs. Here we report that the translational regulator Capr functions as an intrinsic factor required for the proper maintenance of FSCs, and that loss of Capr disrupts cell cycle dynamics within the FSC lineage. We propose that Capr is required for proper execution of the cell cycle in the FSC-lineage, in part through modulation of CYCB protein levels. In this model misregulation of the Capr-dependent cell cycle leads to defects in somatic cell differentiation, with a concomitant disruption of the ability to correctly package developing cysts into egg chambers. The ability of fmr1 mutation to enhance the encapsulation defects implicates these two translational regulatory factors in coordinate control of this aspect of ovary function.

Is Capr solely Required in the FSC Lineage?

Given the similarities between the Capr mutant phenotype and the mutant phenotype of genes involved in FSC proliferation, maintenance, and differentiation, it is possible that Capr is only required in the FSC lineage. Our data, however, cannot rule out the possibility that Capr is additionally required in non-FSC lineage cells to send extrinsic signals that impact the encapsulation process. For example, our clonal analysis demonstrated that Capr is not required for GSC maintenance. However this technique cannot rule out a requirement for Capr in the GSC lineage for other functions such as cell-cell communication. Similarly, because Capr protein was barely detectable in the cap cells or the escort cells it seems less likely that Capr has a critical function in these populations, but not impossible. A more appealing candidate population might be the terminal filament cells based on their prominent CAPR-containing puncta. Terminal filament cells are known to function along with the cap cells as niche cells for both the GSCs and FSCs (reviewed in [1]). It will be interesting to determine whether the bright puncta of CAPR we observe in the terminal filament cells represent ribonucleoprotein structures involved in signal-responsive translational regulation similar to the CAPR-containing neuronal and stress granules of vertebrates [44], [49], [56]. Ultimately, because the clonal removal of Capr specifically from the FSC’s alone disrupted stem cell maintenance, the simplest interpretation of the current data is that an intrinsic role for Capr in the FSC’s can account for all the phenotypes observed. Further study will be required to determine whether Capr has additional roles in other ovarian cells.

fmr1 Collaborates with Capr in the Ovary

During Drosophila embryogenesis, Capr is known to functionally collaborate with fmr1 to regulate the timing of the mid-blastula transition [36]. The functional interaction of these two translational regulators is further supported by evidence that CAPR and dFMRP coimmunoprecipitate from Drosophila embryos [36] and associate with common ribonucleoprotein structures such as neuronal granules [48], [56], [57], [58], stress granules [44], [59], [60], [61], Drosophila lipid droplets [62], and the 5' cap structure of mRNAs in the ovary [63]. In the ovary Capr and fmr1 are expressed in both the germline and somatic cells (this work and [39]). A role for fmr1 in somatic cells and encapsulation was initially considered unlikely because fmr1 mutant egg chambers displaying germ cell proliferation defects are surrounded by apparently normal follicle cells, and are typically flanked by appropriately packaged egg chambers [39], [40]. The maintenance of GSCs, however, relies on fmr1 function outside the GSCs [37], [40] leaving open the possibility that fmr1 functions in the germline cysts and somatic cells of the ovary. Our data indicate that fmr1 and Capr genetically interact to regulate cyst encapsulation and female fecundity. One possible interpretation of our data is that CAPR and dFMRP co-regulate translation of a set of transcripts in FSCs or their progeny important for cyst encapsulation. Alternatively, CAPR and dFMRP could individually regulate distinct transcripts required for proper FSC function. In either case both translational regulators are necessary for proper encapsulation of developing cysts and generation of a functional egg chamber.

Intriguingly recent studies have indicated that FMRP is required for normal functioning of the human ovary as well. Although the mechanism has yet to be determined, FMR1 premutation carriers with no neuro/psychiatric symptoms nevertheless show reduced fecundity due to aberrant control of follicular recruitment and ovarian reserves [64]. In addition to its role in the ovary, dFMRP is reported to affect proliferation of Sertoli cells, the niche cells of the male gonad [65], [66], and to regulate stem cell behavior in the nervous system (reviewed in [67]) and it will be interesting to determine whether CAPR also participates in these processes.

Capr may Act as a Cell Cycle-specific Translational Regulator in the Ovary

In stem cells control of the cell cycle may be uniquely linked to cell fate. For example, in mouse neuroepithelial cells, simply altering the length of G1 using cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors induces differentiation [68]. Likewise in the ovary, as cells produced by FSCs proceed through successive divisions they acquire longer S-phases and increased epigenetic stability, conditions which promote the differentiated state [69]. Furthermore, elevated levels of CYCE are required in the FSC’s themselves, to promote the adherence of these stem cells to their niche [42]. It is therefore plausible that even subtle modulation of the cell cycle by Capr could have profound consequences for production of a functional egg chamber.

Translational control of cell cycle regulation is a specific mechanism reported to affect behavior of both GSCs and FSCs [21], [22]. Although CAPR is reported to be a signal-dependent regulator of translation in the vertebrate nervous system [48], [49], [56] it has been equally implicated in developmental regulation of proliferation: Caprin-1 levels correlate with cell proliferation states in many vertebrate tissues, and caprin-1 deficient cells show a specific delay in G1-S progression [45], [70]. Similarly, FMRP has been predominantly studied because of its role in the nervous system where loss of FMRP causes mental retardation and autism (reviewed in [71]). However, loss of FMRP also generates significant aberrations in proliferation in both the ovary and testis [40], [66]. The encapsulation defects we see, therefore, could be due entirely to a Capr- or Capr and fmr1-dependent alteration of the cell cycle in the FSC lineage.

CAPR is a sequence-specific RNA-binding protein believed to function by altering translation and/or localization of specific mRNA targets [36], [44], [48], [49], [56]. However, despite our genetic evidence that CycB misregulation underlies the defects we observed, CAPR may regulate other mRNAs, and the phenotype we see could be due to a cumulative misexpression of mRNAs involved in cell cycle control and other processes. In this regard there is still much to learn about how CAPR or FMRP achieve temporal and target specificity. For example, both Capr and CycB are expressed in GSCs and numerous other tissues but Capr does not appear to regulate CycB in all of these. Future determination of all relevant mRNA targets in the ovary, and the mechanism for regulating CAPR function and specificity would be constructive steps towards understanding the role of translational regulation in the control of stem cell behavior.

Materials and Methods

Fly Stocks

Stocks were reared on standard cornmeal media. Df(3L)Cat ri fmr13 and Capr2 were previously described [36]. The FRT80B Capr2 stock was generated for this paper. Df(3L)Cat ri sbd1 e, Df(3R)Exel6265, P[+mC] = XP-U}Exel6265, FRT80B, hsFLP; FRT80B arm-lacZ, FRT80B ubi-GFP, wgl–12, ptcS2, CycB2, UAS-CycB, and Act5C-GAL4 stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (Bloomington, IN).

Immunofluorescence

Ovaries were from females fed fresh yeast paste for a minimum of two days. Ovaries were dissected into PBS on ice and broken up by pipeting. Samples were fixed 20 minutes in 4% formaldehyde in PBS, followed by four 15 minute washes in PBST (PBS + 0.1% Triton-X 100). Fixed samples were blocked with PBTA (PBST + 1% BSA) for 1–2 hours at room temperature, incubated with primary antibody in PBTA overnight at 4°C, washed with PBST as above, and incubated 2 hours with secondary antibody. Samples were washed with PBST as above and mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Anti-Caprin polyclonal serum was preabsorbed against Oregon-R ovaries in PBTA prior to use.

Primary Antibodies: mouse anti-FasIII (1∶50, 7G10) and mouse anti-Slit (1∶25 C555.6D) were from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, guinea pig anti-Traffic Jam (1∶3000, [72]), rabbit anti-phospho-Histone H3 (Ser10) (1∶500, Millipore 06–570), mouse anti-BrdU (1∶20, Becton Dickinson 347580), and rabbit anti-Caprin (1∶500, [36]).

Secondary Antibodies: Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1∶500), Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (1∶500), Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-rat IgG (1∶500), Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1∶500), Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti-mouse IgG (1∶500), and Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1∶500) were from Invitrogen. DNA was visualized with TO-PRO-3 iodide (1∶2000, Invitrogen).

Clonal Analysis

hsFLP; FRT80B ubi-GFP/FRT80B Capr2 or hsFLP; FRT80B arm-lacA/FRT80B Capr2 flies were transferred to well yeasted vials each day for at least two days before heat-shock treatment. Flies were then heat-shocked in a 38°C running water bath for 1 hour (twin-spot analysis) or for 1 hour on three consecutive days (FSC and GSC clonal analysis). Flies were then transferred to well-yeasted vials every day until ovaries were dissected and prepared for immunofluorescence.

BrdU labeling

Flies were labeled essentially as described [47]. Briefly, ovaries from well-fed flies were dissected into room temperature Schneider’s Insect Medium (Sigma S0146). Medium was replaced with Schneider’s Insect Medium containing 10 mM 5-Bromo-2-Deoxy-Uridine (Roche 10280879001), and the ovaries were incubated for 1 hour on a nutator at room temperature. Ovaries were washed in Schneider’s Insect Medium twice for three minutes each, and fixed 20 minutes in 1∶1∶4 37% formaldehyde: Buffer B (100 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 pH 6.8, 450 mM KCl, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2): H2O. Fixed samples were washed twice in PBST and twice in DNase buffer (66 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) for 15 minutes each, incubated in DNase buffer with 12.5 U/ml DNaseI (Fermentas EN0521) at 37°C for 30 minutes, and washed three times with PBST for 10 minutes each. Samples were blocked in PBTA for 30–60 minutes, incubated in PBTA containing anti-BrdU antibody overnight at 4°C, and washed four times for 15 minutes each in PBTA. Secondary antibody incubation and subsequent steps were as for immunofluorescence.

Statistics

X2 analysis (http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/chisquared2.cfm) was performed using 1 degree of freedom where a two-tailed P value of < .05 was deemed significant. For clonal analyses at 9 days values for GSCs were X2 = 0.06, P = 0.81 and for FSCs X2 = 10.70, P = 0.001. For clonal analyses at 15 days values for GSCs were X2 = 0.10, P = 0.75 and for FSCs X2 = 36.67, P < 0.0001. For phopho-Histone H3 staining values were X2 = 17.09, P < 0.0001. For BrdU incorporation values were X2 = 2.79, P = 0.09.

Supporting Information

Capr null flies with reduced fmr1 show reduced fecundity over time. Well fed females of the indicated genotypes were mated to Oregon R males and eggs were collected from females of the indicated age range. Df refers to the Capr deficiency, Df(3L)Cat. n = total eggs collected. A) Graph showing eggs laid per unit time per female. B) Graph of the percent of eggs that hatched. Error bars depict standard deviation. Note the dramatic decrease in egg production and viability in 9–11 day old Df, fmr13/Capr2 females.

(TIF)

Polyclonal anti-CAPR antibodies used in this study show no background staining in the germarium. Representative germaria from A) Oregon R (control) or B) Capr2/Df(3L)Cat (Capr-) flies stained with preabsorbed anti-Caprin antibodies (top panels, CAPR, green) and TO-PRO-3 iodide (bottom panels, DNA, red). Scale bar is 30 microns.

(TIF)

Data are shown for the percent of ovarioles containing an egg chamber with the indicated number of nurse cells. Df refers to the Capr deficiency, Df(3L)Cat. n = number of ovarioles scored.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Howard Wang for his contributions to Figure 1A.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health - National Institute of General Medical Sciences, grant no. 5RO1GM087562 (http://www.nigms.nih.gov). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Losick VP, Morris LX, Fox DT, Spradling A. Drosophila stem cell niches: a decade of discovery suggests a unified view of stem cell regulation. Dev Cell. 2011;21:159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahowald AP, Kambysellis MP. Oogenesis. In: Ashburner M, Wright TRF, editors. The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila. London and New York: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 141–224. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decotto E, Spradling AC. The Drosophila ovarian and testis stem cell niches: similar somatic stem cells and signals. Dev Cell. 2005;9:501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schüpbach T, Wieschaus E, Nöthiger R. A study of the female germ line in mosaics of Drosophila. Wilhelm Roux’s Archives of Developmental Biology. 1978;184:41–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00848668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wieschaus E, Szabad J. The development and function of the female germ line in Drosophila melanogaster: a cell lineage study. Dev Biol. 1979;68:29–46. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(79)90241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spradling AC. Developmental Genetics of Oogenesis. In: Bate M, Martinez Arias A, editors. The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris LX, Spradling AC. Long-term live imaging provides new insight into stem cell regulation and germline-soma coordination in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 2011;138:2207–2215. doi: 10.1242/dev.065508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Margolis J, Spradling A. Identification and behavior of epithelial stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 1995;121:3797–3807. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nystul T, Spradling A. An epithelial niche in the Drosophila ovary undergoes long-range stem cell replacement. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nystul T, Spradling A. Regulation of epithelial stem cell replacement and follicle formation in the Drosophila ovary. Genetics. 2010;184:503–515. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.109538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrison SJ, Spradling AC. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell. 2008;132:598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song X, Xie T. DE-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion is essential for maintaining somatic stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14813–14818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232389399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie T, Spradling AC. decapentaplegic is essential for the maintenance and division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Cell. 1998;94:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie T, Spradling AC. A niche maintaining germ line stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Science. 2000;290:328–330. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris RE, Pargett M, Sutcliffe C, Umulis D, Ashe HL. Brat promotes stem cell differentiation via control of a bistable switch that restricts BMP signaling. Dev Cell. 2011;20:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JY, Lee YC, Kim C. Direct inhibition of Pumilo activity by Bam and Bgcn in Drosophila germ line stem cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4741–4746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu N, Han H, Lasko P. Vasa promotes Drosophila germline stem cell differentiation by activating mei-P26 translation by directly interacting with a (U)-rich motif in its 3' UTR. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2742–2752. doi: 10.1101/gad.1820709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen R, Weng C, Yu J, Xie T. eIF4A controls germline stem cell self-renewal by directly inhibiting BAM function in the Drosophila ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11623–11628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903325106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z, Lin H. Nanos maintains germline stem cell self-renewal by preventing differentiation. Science. 2004;303:2016–2019. doi: 10.1126/science.1093983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forstemann K, Tomari Y, Du T, Vagin VV, Denli AM, et al. Normal microRNA maturation and germ-line stem cell maintenance requires Loquacious, a double-stranded RNA-binding domain protein. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatfield SD, Shcherbata HR, Fischer KA, Nakahara K, Carthew RW, et al. Stem cell division is regulated by the microRNA pathway. Nature. 2005;435:974–978. doi: 10.1038/nature03816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin Z, Xie T. Dcr-1 maintains Drosophila ovarian stem cells. Curr Biol. 2007;17:539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park JK, Liu X, Strauss TJ, McKearin DM, Liu Q. The miRNA pathway intrinsically controls self-renewal of Drosophila germline stem cells. Curr Biol. 2007;17:533–538. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Xu S, Xia L, Wang J, Wen S, et al. The bantam microRNA is associated with drosophila fragile X mental retardation protein and regulates the fate of germline stem cells. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buszczak M, Paterno S, Spradling AC. Drosophila stem cells share a common requirement for the histone H2B ubiquitin protease scrawny. Science. 2009;323:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1165678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xi R, Xie T. Stem cell self-renewal controlled by chromatin remodeling factors. Science. 2005;310:1487–1489. doi: 10.1126/science.1120140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Reilly AM, Lee HH, Simon MA. Integrins control the positioning and proliferation of follicle stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:801–815. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forbes AJ, Lin H, Ingham PW, Spradling AC. hedgehog is required for the proliferation and specification of ovarian somatic cells prior to egg chamber formation in Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:1125–1135. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.4.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forbes AJ, Spradling AC, Ingham PW, Lin H. The role of segment polarity genes during early oogenesis in Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:3283–3294. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartman TR, Zinshteyn D, Schofield HK, Nicolas E, Okada A, et al. Drosophila Boi limits Hedgehog levels to suppress follicle stem cell proliferation. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:943–952. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirilly D, Spana EP, Perrimon N, Padgett RW, Xie T. BMP signaling is required for controlling somatic stem cell self-renewal in the Drosophila ovary. Dev Cell. 2005;9:651–662. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song X, Xie T. Wingless signaling regulates the maintenance of ovarian somatic stem cells in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:3259–3268. doi: 10.1242/dev.00524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Kalderon D. Hedgehog acts as a somatic stem cell factor in the Drosophila ovary. Nature. 2001;410:599–604. doi: 10.1038/35069099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X, Han Y, Xi R. Polycomb group genes Psc and Su(z)2 restrict follicle stem cell self-renewal and extrusion by controlling canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling. Genes Dev. 2010;24:933–946. doi: 10.1101/gad.1901510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Narbonne K, Besse F, Brissard-Zahraoui J, Pret AM, Busson D. polyhomeotic is required for somatic cell proliferation and differentiation during ovarian follicle formation in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:1389–1400. doi: 10.1242/dev.01003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papoulas O, Monzo KF, Cantin GT, Ruse C, Yates JR, III, et al. dFMRP and Caprin, translational regulators of synaptic plasticity, control the cell cycle at the Drosophila mid-blastula transition. Development. 2010;137:4201–4209. doi: 10.1242/dev.055046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang L, Duan R, Chen D, Wang J, Jin P. Fragile X mental retardation protein modulates the fate of germline stem cells in Drosophila. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1814–1820. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Kalderon D. Regulation of cell proliferation and patterning in Drosophila oogenesis by Hedgehog signaling. Development. 2000;127:2165–2176. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.10.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costa A, Wang Y, Dockendorff TC, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, et al. The Drosophila fragile X protein functions as a negative regulator in the orb autoregulatory pathway. Dev Cell. 2005;8:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epstein AM, Bauer CR, Ho A, Bosco G, Zarnescu DC. Drosophila Fragile X protein controls cellular proliferation by regulating cbl levels in the ovary. Dev Biol. 2009;330:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu T, Rubin GM. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–1237. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang ZA, Kalderon D. Cyclin E-dependent protein kinase activity regulates niche retention of Drosophila ovarian follicle stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21701–21706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909272106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orford KW, Scadden DT. Deconstructing stem cell self-renewal: genetic insights into cell-cycle regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:115–128. doi: 10.1038/nrg2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solomon S, Xu Y, Wang B, David MD, Schubert P, et al. Distinct structural features of caprin-1 mediate its interaction with G3BP-1 and its induction of phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2alpha, entry to cytoplasmic stress granules, and selective interaction with a subset of mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2324–2342. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02300-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang B, David MD, Schrader JW. Absence of caprin-1 results in defects in cellular proliferation. J Immunol. 2005;175:4274–4282. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hendzel MJ, Wei Y, Mancini MA, Van Hooser A, Ranalli T, et al. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates primarily within pericentromeric heterochromatin during G2 and spreads in an ordered fashion coincident with mitotic chromosome condensation. Chromosoma. 1997;106:348–360. doi: 10.1007/s004120050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calvi BR, Lilly MA. Fluorescent BrdU labeling and nuclear flow sorting of the Drosophila ovary. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;247:203–213. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-665-7:203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shiina N, Shinkura K, Tokunaga M. A novel RNA-binding protein in neuronal RNA granules: regulatory machinery for local translation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4420–4434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0382-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shiina N, Yamaguchi K, Tokunaga M. RNG105 deficiency impairs the dendritic localization of mRNAs for Na+/K+ ATPase subunit isoforms and leads to the degeneration of neuronal networks. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12816–12830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6386-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grosshans J, Muller HA, Wieschaus E. Control of cleavage cycles in Drosophila embryos by fruhstart. Dev Cell. 2003;5:285–294. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gelbart WM, Emmert DB. FlyBase High Throughput Expression Data Beta Version (Peter McQuilton, Susan E. St. Pierre, Jim Thurmond, and the FlyBase Consortium FlyBase 101 – the basics of navigating FlyBase. Nucleic Acids Research (2011) 2010;39:21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1030. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z, Lin H. The division of Drosophila germline stem cells and their precursors requires a specific cyclin. Curr Biol. 2005;15:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sigrist S, Jacobs H, Stratmann R, Lehner CF. Exit from mitosis is regulated by Drosophila fizzy and the sequential destruction of cyclins A, B and B3. EMBO J. 1995;14:4827–4838. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pepper AS, Beerman RW, Bhogal B, Jongens TA. Argonaute2 suppresses Drosophila fragile X expression preventing neurogenesis and oogenesis defects. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kirilly D, Xie T. The Drosophila ovary: an active stem cell community. Cell Res. 2007;17:15–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shiina N, Tokunaga M. RNA granule protein 140 (RNG140), a paralog of RNG105 localized to distinct RNA granules in neuronal dendrites in the adult vertebrate brain. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24260–24269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.108944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barbee SA, Estes PS, Cziko AM, Hillebrand J, Luedeman RA, et al. Staufen- and FMRP-containing neuronal RNPs are structurally and functionally related to somatic P bodies. Neuron. 2006;52:997–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elvira G, Wasiak S, Blandford V, Tong XK, Serrano A, et al. Characterization of an RNA granule from developing brain. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:635–651. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500255-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dolzhanskaya N, Zie W, Merz G, Denman RB. EGFP-FMRP forms proto-stress granules: A poor surrogate for endogenous FMRP. J Biophys Struct Biol. 2011;3:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kunde SA, Musante L, Grimme A, Fischer U, Muller E, et al. Hum Mol Genet; 2011. The X-chromosome linked intellectual disability protein PQBP1 is a component of neuronal RNA granules and regulates the appearance of stress granules. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mazroui R, Huot ME, Tremblay S, Filion C, Labelle Y, et al. Trapping of messenger RNA by Fragile X Mental Retardation protein into cytoplasmic granules induces translation repression. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:3007–3017. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.24.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cermelli S, Guo Y, Gross SP, Welte MA. The lipid-droplet proteome reveals that droplets are a protein-storage depot. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1783–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pisa V, Cozzolino M, Gargiulo S, Ottone C, Piccioni F, et al. The molecular chaperone Hsp90 is a component of the cap-binding complex and interacts with the translational repressor Cup during Drosophila oogenesis. Gene. 2009;432:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gleicher N, Barad DH. The FMR1 gene as regulator of ovarian recruitment and ovarian reserve. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2010;65:523–530. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181f8bdda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oatley MJ, Racicot KE, Oatley JM. Sertoli cells dictate spermatogonial stem cell niches in the mouse testis. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:639–645. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.087320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Slegtenhorst-Eegdeman KE, de Rooij DG, Verhoef-Post M, van de Kant HJ, Bakker CE, et al. Macroorchidism in FMR1 knockout mice is caused by increased Sertoli cell proliferation during testicular development. Endocrinology. 1998;139:156–162. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.1.5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Callan MA, Zarnescu DC. Heads-up: new roles for the fragile X mental retardation protein in neural stem and progenitor cells. Genesis. 2011;49:424–440. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Calegari F, Huttner WB. An inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases that lengthens, but does not arrest, neuroepithelial cell cycle induces premature neurogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4947–4955. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Skora AD, Spradling AC. Epigenetic stability increases extensively during Drosophila follicle stem cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7389–7394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003180107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grill B, Wilson GM, Zhang KX, Wang B, Doyonnas R, et al. Activation/division of lymphocytes results in increased levels of cytoplasmic activation/proliferation-associated protein-1: prototype of a new family of proteins. J Immunol. 2004;172:2389–2400. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Rubeis S, Bagni C. Regulation of molecular pathways in the Fragile X Syndrome: insights into Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Neurodev Disord. 2011;3:257–269. doi: 10.1007/s11689-011-9087-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li MA, Alls JD, Avancini RM, Koo K, Godt D. The large Maf factor Traffic Jam controls gonad morphogenesis in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:994–1000. doi: 10.1038/ncb1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Capr null flies with reduced fmr1 show reduced fecundity over time. Well fed females of the indicated genotypes were mated to Oregon R males and eggs were collected from females of the indicated age range. Df refers to the Capr deficiency, Df(3L)Cat. n = total eggs collected. A) Graph showing eggs laid per unit time per female. B) Graph of the percent of eggs that hatched. Error bars depict standard deviation. Note the dramatic decrease in egg production and viability in 9–11 day old Df, fmr13/Capr2 females.

(TIF)

Polyclonal anti-CAPR antibodies used in this study show no background staining in the germarium. Representative germaria from A) Oregon R (control) or B) Capr2/Df(3L)Cat (Capr-) flies stained with preabsorbed anti-Caprin antibodies (top panels, CAPR, green) and TO-PRO-3 iodide (bottom panels, DNA, red). Scale bar is 30 microns.

(TIF)

Data are shown for the percent of ovarioles containing an egg chamber with the indicated number of nurse cells. Df refers to the Capr deficiency, Df(3L)Cat. n = number of ovarioles scored.

(DOCX)