Background: Origin recognition complex (ORC) binds to the replication origin for initiation of eukaryotic chromosome replication.

Results: Phosphorylation of human ORC2 in the S phase dissociates ORC from chromatin and replication origins.

Conclusion: Phosphorylation of ORC2 dissociates ORC from DNA and inhibits binding of ORC to newly replicated DNA.

Significance: Phosphorylation of ORC2 controls chromatin binding of ORC.

Keywords: Cyclin-dependent Kinase (CDK), Cell Cycle, Chromatin, DNA Replication, Phosphorylation, ORC, Prereplicative Complex

Abstract

During the late M to the G1 phase of the cell cycle, the origin recognition complex (ORC) binds to the replication origin, leading to the assembly of the prereplicative complex for subsequent initiation of eukaryotic chromosome replication. We found that the cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of human ORC2, one of the six subunits of ORC, dissociates ORC2, -3, -4, and -5 (ORC2–5) subunits from chromatin and replication origins. Phosphorylation at Thr-116 and Thr-226 of ORC2 occurs by cyclin-dependent kinase during the S phase and is maintained until the M phase. Phosphorylation of ORC2 at Thr-116 and Thr-226 dissociated the ORC2–5 from chromatin. Consistent with this, the phosphomimetic ORC2 protein exhibited defective binding to replication origins as well as to chromatin, whereas the phosphodefective protein persisted in binding throughout the cell cycle. These results suggest that the phosphorylation of ORC2 dissociates ORC from chromatin and replication origins and inhibits binding of ORC to newly replicated DNA.

Introduction

Chromosome DNA replication is coordinated with cell cycle progression (1–3). Chromosome replication occurs only once per cell cycle, specifically by limiting licensing of origins (prereplicative complex (pre-RC)4 formation) to the late M and early G1 phase of the cell cycle (4, 5). During pre-RC formation, ORC binding to the origin of replication results in recruitment of Cdc6, Cdt1, and Mcm2–7 complexes (6–8). DNA replication occurs only during the S phase, originating at the pre-RCs formed during the G1 phase.

ORC was first identified to bind to autonomously replicating sequences (ARS) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a sequence-specific manner (9, 10). ORC consists of six different subunits, which are conserved among a diverse range of eukaryotes. In higher eukaryotes, origin binding by ORC appears to be sequence-independent (11). ORC possesses ATP binding and hydrolysis activities attributed to the AAA+ ATPase motif of the ORC1, -4, and -5 subunits (12, 13). ATP binding is involved in ORC complex formation, DNA binding, and pre-RC assembly. The human ORC subunits ORC2–5 form a stable subcomplex, and ORC1 is transiently associated with this complex during the late M to G1 phase (14–16). ORC1 association allows ORC to function at the replication origin, and ORC1 is dissociated from chromatin at the end of the S phase (16–18). Although the yeast ORC binds to the origin of replication throughout the cell cycle, several reports have suggested that mammalian ORC dissociates from chromatin and the replication origin as the cell progresses through the S phase through some unknown mechanism (15, 16, 19), but the mechanism of this dissociation is not known.

The ORC1, ORC2, and ORC6 subunits contain consensus sequences for phosphorylation by CDK (8, 20–22). Mutation of the CDK phosphorylation site of ORC2 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe resulted in rereplication (23). Mutations of S. cerevisiae ORC2 at a CDK phosphorylation site delayed S phase progression and G1/S transition (24). CDK phosphorylation of ORC1, ORC2, and Cdc6 inhibited the replication reinitiation in S. cerevisiae (25). In vitro studies with S. cerevisiae showed that CDK phosphorylation of ORC2 and ORC6 inhibited the loading of Cdt1 and Mcm2–7 onto the origin of replication (8). In vertebrates, hamster ORC1 was hyperphosphorylated by cyclin A-CDK1 during the G2 to M phase, which suppressed the chromatin reloading of the ORC during mitosis (26). In Xenopus egg extracts, phosphorylation of ORC subunits has been proposed to dissociate the complex from chromatin (20).

Despite all of this evidence in other species, there is no clear demonstration that human ORC is inactivated during cell cycle progression through its phosphorylation by CDK. In this report, we demonstrate that phosphorylation of human ORC2 controls the binding of ORC to chromatin and replication origins. The phosphorylation at Thr-116 and Thr-226 of ORC2 by CDK in the S phase dissociates ORC from chromatin and replication origins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Phosphorylated ORC2 Antibodies

Phosphospecific antibodies were generated using synthetic peptides corresponding to amino acids 112–120 (CELAKpTPQKS) and 221–230 (CPVGKEpTPSKR) of ORC2 for anti-phospho-Thr-116 (α-pT116) and anti-phospho-Thr-226 (α-pT226) antibodies, respectively (Peptron Corp.). Immunizing sera were purified by two-step affinity purification using resins linked to phosphopeptide and non-phosphopeptide.

Chromatin Fractionation

Chromatin fractionation was performed as described previously (15) with modifications. Synchronized HeLa cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and resuspended in buffer A (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 20 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, protease inhibitor mixture (Calbiochem), and 200 nm calyculin A) for 15 min on ice followed by Dounce homogenization. Nuclei obtained by centrifugation at 1,300 × g for 5 min were lysed with buffer A containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40 and then centrifuged. The soluble fraction was the supernatant, and the precipitate was successively eluted with buffer B (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, and 20 nm calyculin A) containing 0.1, 0.25, and 0.45 m NaCl, or, for Fig. 5B, cells were resuspended in buffer C (10 mm PIPES, pH 7.9, 0.2 m NaCl, 0.3 m sucrose, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm EGTA, 200 μm Na3VO4, 10 mm NaF, 20 nm calyculin A, and a protease inhibitor mixture) and lysed on ice for 10 min followed by centrifugation at 1,300 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min to obtain a soluble fraction, and the precipitate was washed once with two volumes of buffer C to obtain the precipitate (chromatin-enriched) fraction.

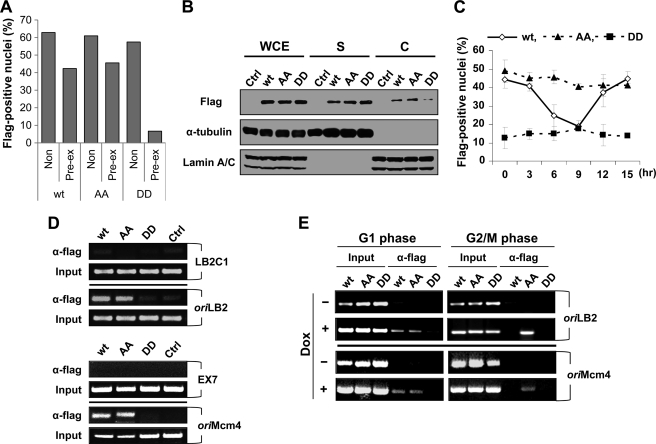

FIGURE 5.

Phosphorylation of ORC2 dissociates the ORC from chromatin and the replication origin. A, HeLa Tet-On cells expressing FLAG-tagged ORC2 wild type (wt), T116A/T226A (AA) mutant, or T116D/T226D (DD) mutant were incubated in media containing 2 μg/ml doxycycline for 48 h. The cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and then stained with anti-FLAG antibody, followed by Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody. Pre-extraction was performed using 0.5% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline for 1 min before fixation (supplemental Fig. 3). The nuclei exhibiting FLAG-positive signal were quantified using ImageJ software and described as the ratio of positive nuclei over total number of nuclei. B, chromatin fractionation was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Proteins were detected by immunoblot analysis. WCE, whole-cell extract; S, soluble fraction; C, chromatin-enriched fraction; Ctrl, HeLa Tet-On cells containing no FLAG-ORC2 gene. C, HeLa Tet-On cells expressing the indicated FLAG-ORC protein, which were arrested at the G1/S boundary using a double thymidine block, were released into fresh media for the indicated time. At 24 h before thymidine release, 2 μg/ml doxycycline was added to the medium. After pre-extraction, cells containing FLAG-positive nuclei were scored and indicated as a ratio over total cells. Three independent experiments were performed. D, asynchronously growing HeLa Tet-On cells expressing the corresponding FLAG-tagged ORC2 were obtained by the addition of 2 μg/ml doxycyline for 48 h before cell harvest. The chromatin-immunoprecipitation using an anti-FLAG antibody was followed by amplification by PCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Input DNAs were obtained by PCR of the soluble chromatin fraction. oriLB2, the replication origin in lamin B2; LB2C1, 3.5 kbp upstream from oriLB2; oriMcm4, the replication origin in the Mcm4 upstream promoter region; EX7, exon VII coding region of the Mcm4 gene. E, the G1 or the G2/M phase cells were obtained by 8 h after release of nocodazole or from double-thymidine arrested cells, respectively. FLAG-ORC2 proteins were expressed by the addition of 2 μg/ml doxycyline for 48 h before cell harvest. Then ChIP assays were performed. Dox, doxycycline.

Tet-On Inducible Cell Lines

FLAG-tagged ORC2 wild type (WT), T116A/T226A (AA), or T116D/T226D (DD) mutant gene inserted into a pTRE2hyg vector was transfected into HeLa Tet-On cells, which contained the stably expressed reverse tetracycline-responsive transcriptional activator (Clontech). Hygromycin-resistant cells were selected under 200 μg/ml hygromycin (A.G. Scientific) for 2–4 weeks and were then used in the experiments. FLAG-ORC2 proteins were induced by the addition of 2 μg/ml doxycycline.

ChIP Assay

Soluble chromatin fraction following sonication was obtained as described previously (27, 28). One-tenth of the soluble chromatin fraction was used in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as the input control, and the residual fraction was precipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and protein A-Sepharose beads followed by sequential washes for 5 min each in TSE buffers (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mm EDTA, and 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.1) containing either 150 or 500 mm NaCl, buffer III (0.25 m LiCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% deoxycholate, 1 mm EDTA, and 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.1), and TE buffer. The immunocomplexes were eluted with elution buffer (1% SDS and 0.1 m NaHCO3) and heated at 65 °C for reverse cross-linking. PCR was performed with primers to amplify oriLB2 (the origin region of the human lamin B2; 5′-GGCTGGCATGGACTTTCATTTCAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGGAGGGATCTTTCTTAGACATC-3′ (reverse)), LB2C1 (3.5 kbp upstream of the LB2; 5′-GTTAACAGTCAGGCGCATGGGCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCATCAGGGTCACCTCTGGTTCC-3′ (reverse)), oriMcm4 (the origin in the upstream promoter region of Mcm4; 5′-AAACCAGAAGTAGGCCTCGCTCGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCTGACCTGCGGAGGTAGTTTGG-3′ (reverse)), and EX7 (the exon VII region of the Mcm4 gene; 5′-TAATCCGTCACCTTGACTACCACC-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACAGCACGTGCATGATTCTGTAGG-3′ (reverse)) (29).

RESULTS

Human ORC2 Is Phosphorylated at Thr-116 and Thr-226

Protein function is often controlled by phosphorylation. In order to examine the phosphorylation of human ORC2, HEK293T cells expressing GST-ORC2 or GST-ORC2-fragments were incubated with [32P]orthophosphate for in vivo labeling (Fig. 1A). 32P was incorporated specifically into GST-ORC2 isolated by glutathione-agarose pull-down. The 32P was incorporated into the N-terminal 230-amino acid fragment but not the C-terminal 347-amino acid fragment.

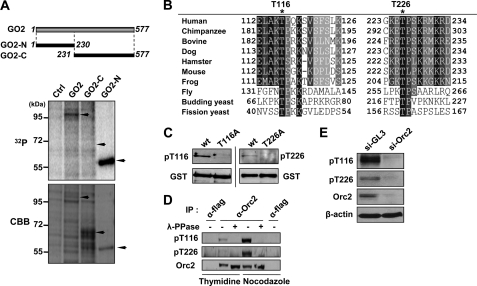

FIGURE 1.

Phosphorylation of human ORC2 at Thr-116 and Thr-226. A, DNA constructs expressing GST-tagged full-length human ORC2 (GST-ORC2), the N-terminal 230 amino acid residues of human ORC2 (GST-ORC2-N), or the C-terminal 347 amino acid residues of human ORC2 (GST-ORC2-C) were transfected into HEK293T cells and incubated in phosphate-free medium containing 200 μCi/ml [32P]orthophosphate for 4 h before harvesting. The 32P and CBB panels represent the autoradiogram and Coomassie Brilliant Blue-stained gel, respectively, of proteins pulled down on glutathione-agarose beads. Ctrl, empty vector; GO2, GST-ORC2; GO2-N, GST-ORC2-N; GO2-C, GST-ORC2-C. B, phosphorylated amino acid residues of human ORC2 determined by mass spectrometry (supplemental Fig. 1) are denoted by asterisks. Alignment of ORC2 protein sequences of human and other eukaryotes was performed using the ClustalW2 program. Ser (S) or Thr (T) in the sequence (S/T)PX(K/R), where X is any amino acid, is potentially phosphorylated by CDK2 (31). C, the indicated proteins, isolated by GST pull-down from HEK293T cells transfected with the corresponding DNA, were analyzed by immunoblot with α-pT116 or α-pT226 antibodies. WT, GST-ORC2; T116A, GST-ORC2 (T116A); T226A, GST-ORC2 (T226A). The lower panels show GST-ORC2 detected by anti-GST-antibody. D, ORC2 protein immunoprecipitated (IP) from cells arrested with double thymidine or nocodazole using a mouse monoclonal anti-ORC2 antibody (α-ORC2; Calbiochem) was immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. Monoclonal mouse anti-FLAG antibody (α-FLAG; Sigma) was used as control antibody. λ-Phosphatase (λ-PPase) (New England Biolabs) was treated for 30 min at 30 °C. E, HeLa cells were depleted using the following siRNA oligonucleotides (Samchully Pharm): control siRNA (si-GL3), CUUACGCUGAGUACUUCGA; ORC2 siRNA (si-ORC2), GAAGGAGCGAGCGCAGCUU. The depleted cells were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies.

To identify phosphorylated amino acid residues of ORC2, endogenous ORC2 immunoprecipitated by using anti-ORC2 antibody was analyzed by mass spectrometry. This analysis revealed phosphorylation at Thr-116 and Thr-226 (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. 1), both of which are located in the N-terminal region of ORC2. Thr-116, Thr-226, and their adjacent amino acids are conserved in ORC2 homologues of higher eukaryotes, ranging from frogs to humans (Fig. 1B).

To verify the phosphorylation at Thr-116 and Thr-226 of ORC2, we generated phosphoantibodies that specifically detected phospho-Thr-116 or phospho-Thr-226 of ORC2. The α-pT116 and α-pT226 antibodies recognized GST-ORC2 expressed in 293T cells (Fig. 1C). However, neither phosphoantibody detected mutant forms of the protein with Thr to Ala substitutions (T116A or T226A). In addition, both phosphoantibodies recognized endogenous ORC2 after immunoprecipitation by an anti-ORC2 antibody, but not after treatments of the immunoprecipitate with λ-phosphatase (Fig. 1D). Neither phospho-Thr-116 nor phospho-Thr-226 of ORC2 was detected in cells in which ORC2 was depleted by RNA interference (Fig. 1E). These results show that α-pT116 and α-pT226 specifically recognize phospho-Thr-116-ORC2 and phospho-Thr-226-ORC2, respectively.

A double thymidine block arrests cells in the G1/S boundary, and nocodazole arrests cells in the prometaphase of mitosis. Interestingly, nocodazole-treated cells contained more phosphorylated ORC2 than thymidine-treated cells (Fig. 1D). These different levels of phosphorylation suggest that ORC2 phosphorylation might take place in a cell cycle-dependent manner.

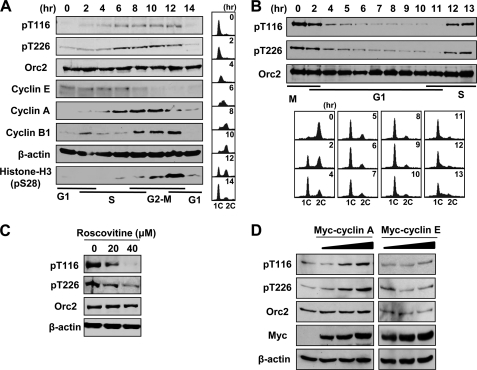

Phosphorylation of ORC2 in S Phase

Release of cells from a double thymidine block led to synchronized progression of cells through S phase (Fig. 2A). Both FACS analysis and measurement of cell cycle markers indicated S phase progression by 6–8 h and cell division by 10–12 h after the release. At 14 h post-release, most cells had reached the next G1 phase. Although the level of ORC2 was nearly constant throughout the cell cycle, the amounts of phospho-Thr-116 and phospho-Thr-226 ORC2 started to increase 2 h after release, reached a peak by 6 h postrelease, and were maintained until 12 h postrelease. Fourteen hours postrelease, when cells were in early G1, the phosphorylation level dramatically decreased. Interestingly, the cell cycle pattern of ORC2 phosphorylation was similar to that of cyclin A, which increases during the S phase and degrades at the metaphase-anaphase transition of mitosis (30). Detection of ORC2 phosphorylation in cells released from nocodazole arrest confirmed an unphosphorylated state in the G1 phase and phosphorylated states in the M and S phases (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that ORC2 phosphorylation at Thr-116 and Thr-226 occurs in the S phase, and the phosphorylated state persists until the M phase.

FIGURE 2.

Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of ORC2 by CDK. A, synchronized growth of HeLa cells was achieved by blocking cells in G1/S using double thymidine block. At the indicated times after release into fresh media, cell cycle progression was determined by FACS analysis of propidium iodide-stained cells (right) and by detecting the proteins in immunoblots (left). B, nocodazole (200 ng/ml for 16 h)-treated U2OS cells were collected by mitotic shake-off and released into fresh media. C, HeLa cells were treated with the indicated concentration of roscovitine for 3 h before cell harvest and were analyzed by immunoblot. D, HeLa cells were transfected with 0, 1, 2, and 4 μg of the indicated DNA constructs followed by incubation for 48 h, and the indicated proteins were analyzed by immunoblot.

Thr-116 and Thr-226 of ORC2 are within a TPXK consensus sequence for CDK (31), which are conserved in other eukaryotes (Fig. 1B). The CDK inhibitor roscovitine reduced phosphorylation at Thr-116 and Thr-226 (Fig. 2C). Overexpression of cyclin A, a major cyclin associated with CDK2 during the S phase (32), enhanced phosphorylation at Thr-116 and Thr-226 (Fig. 2D). In contrast, overexpression of cyclin E, which activates CDK2 in the G1 phase (32), did not significantly increase phosphorylation. Immunoprecipitation of ORC2 with an anti-ORC2 antibody co-precipitated cyclin A and CDK2 in the S and G2 phases (supplemental Fig. 2A). In addition, GST-ORC2 protein was phosphorylated by the cyclin A immunoprecipitate in vitro, but the phosphorylation was dramatically decreased on phosphodefective GST-ORC2-AA, in which Thr-116 and Thr-226 were mutated to Ala (supplemental Fig. 2B). These results suggest that cyclin A-CDK2 phosphorylates ORC2 at Thr-116 and Thr-226 in the S phase.

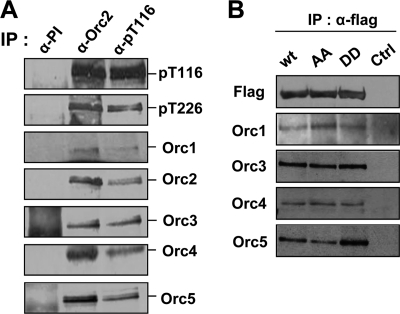

Phosphorylation of ORC2 Does Not Affect Formation of ORC Complex

We first examined whether phosphorylation of ORC2 affected ORC assembly. Immunoprecipitation of ORC2 by an anti-ORC2 antibody or by α-pT116 co-precipitated ORC1, -3, -4, and -5 subunits (Fig. 3A). In addition, the ORC2 precipitated by α-pT116 was also phosphorylated at Thr-226. The relative levels of other ORC subunits that co-precipitated with phosphorylated ORC2 appear to be similar to those co-precipitated with ORC2 by an anti-ORC2 antibody. To support the co-precipitation data, we utilized phosphodefective (AA) and phosphomimetic (DD) mutant forms of FLAG-ORC2 with substitution of both Thr-116 and Thr-226 with Ala or Asp, respectively (Fig. 3B). Immunoprecipitation of the phosphodefective and phosphomimetic mutant FLAG-ORC2 by an anti-FLAG antibody co-precipitated similar levels of the ORC1, -3, -4, and -5 subunits compared with the corresponding wild type protein. These results suggest that the phosphorylation of ORC2 does not affect complex formation of the ORC.

FIGURE 3.

ORC assembly is not affected by ORC2 phosphorylation. A, HeLa G2/M extracts were prepared by 8-h release from double thymidine block, and immunoprecipitation (IP) was then performed using anti-rabbit preimmune serum (α-PI), anti-ORC2 (α-ORC2), or α-pT116 antibody. B, HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG-ORC2 (wt), FLAG-ORC2-T116A/226A (AA), or FLAG-ORC2-T116D/226D (DD) expressing DNA empty vector (Ctrl) and were harvested after 48 h. Each lysate was incubated with anti-FLAG antibody for 3 h, and immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted using the corresponding antibody.

Phosphorylation of ORC2 Dissociates ORC from Chromatin

To investigate the effect of phosphorylation of ORC2, chromatin fractionation was performed on cell extracts prepared from synchronized cells in the G1 phase or in different stages of the S phase (Fig. 4A). Phosphorylated ORC2 was easily dephosphorylated during cell lysis and chromatin fractionation, and calyculin A, which is an inhibitor of protein phosphatases (33), prevented this dephosphorylation. Therefore, calyculin A was included during cell lysis and chromatin fractionation. Both 0.1 and 0.25 m NaCl eluates of chromatin from G1 phase cells contained similar levels of the ORC2–5 subunits, which form a stable subcomplex (13, 14, 34) (Fig. 4A and supplemental Fig. 3A). However, overexposure of phospho-Thr-116 and phospho-Thr-226 immunoblots revealed that the phosphorylated ORC2 proteins distributed to the 0.1 m NaCl eluate rather than to the 0.25 m NaCl eluate, suggesting that phosphorylated ORC2 proteins are released from chromatin at a lower NaCl concentration than non-phosphorylated ORC2 proteins. As the S phase progressed, the cell fractions contained more phospho-Thr-116 and phospho-Thr-226 of ORC2. The soluble fractions and 0.1 m NaCl eluates contained higher amounts of ORC2–5 than the 0.25 m NaCl eluates. In addition, co-immunoprecipitated ORC2 of G2/M cells using anti-ORC4 antibody showed that the soluble fraction contained more phospho-Thr-116 and phospho-Thr-226 of ORC2 than the 0.25 m NaCl fraction (Supplemental Fig. 3B). The cell cycle progression to the S/G2 phase decreased the ORC1 amount as previously reported, but the elution patterns of ORC1 and ORC6 appeared not to be altered (17, 18).

FIGURE 4.

Phosphorylation of ORC2 in the S phase dissociates the ORC from chromatin. A, HeLa cells arrested with nocodazole were released for 4 h for G1 phase cells. For S- and G2/M phase cells, the cells arrested with double thymidine block were released for 4 and 8 h, respectively. The FACS profiles of harvested cells are shown in the top panel. The chromatin fractionations of harvested cells were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The indicated proteins were detected by immunoblot analysis. S, soluble fraction; ppt, precipitate after 0.45 m NaCl elution. B, 10 nm calyculin A, as the final concentration, was added to synchronously growing S or G1 phase HeLa cell cultures 30 min prior to cell harvest and during chromatin fractionation (+) or not at all (−). The FACS profiles of each cell sample are shown in the bottom panel.

To avoid dephosphorylation of ORC2, we fractionated the chromatin in the presence of calyculin A for 30 min prior to cell harvest of S phase cells and during fractionation (Fig. 4B). The presence of calyculin A, which preserves more phosphorylated ORC2, shifted ORC2–5 to eluates obtained at lower NaCl concentrations. On the other hand, the addition of calyculin A to G1 phase cells did not significantly increase the phosphorylation of ORC2 or alter the fractionation pattern of ORC2–5. The calyculin A treatment reduced the ORC1 amounts of both S and G1 phase but did not affect the elution pattern of ORC2–5 in the G1 phase. These results, along with the finding that phosphorylation of ORC2 had no effect on ORC formation (Fig. 3), suggest that phosphorylation of ORC2 during the S phase reduces the affinity of the ORC2–5 for chromatin and that dephosphorylation increases the affinity.

To further demonstrate that reduction in ORC chromatin binding was a result of ORC2 phosphorylation at Thr-116 and Thr-226, we utilized phosphodefective and phosphomimetic mutant forms of ORC2. Each FLAG-ORC2 gene was inserted into a doxycycline-inducible vector, transfected into a HeLa Tet-On cell line, and then selected in the presence of hygromycin for 2 weeks. The addition of doxycycline to cells induced expression of the corresponding protein (supplemental Fig. 3A and Fig. 5A). Pre-extraction of cells with detergent removed soluble non-chromatin-associated proteins from the nucleus (35). Unlike the wild type or phosphodefective protein, pre-extraction removed the phosphomimetic ORC2 mutant protein from the nucleus. In addition, the phosphomimetic ORC2 protein decreased in the chromatin-enriched fraction but increased in the soluble fraction, unlike the wild type or phosphodefective protein (Fig. 5B). These results show that phosphorylation of ORC2 reduced the association of the ORC with chromatin.

Phosphorylation of ORC2 Dissociates ORC from Origin of Replication

Cell cycle-dependent association of the FLAG-ORC2 protein with chromatin was examined. Cell cycle progression and amounts of each protein induced after the addition of doxycycline were similar among the cells (supplemental Fig. 4, B and C). Wild type FLAG-ORC2 began to dissociate from chromatin in the early S phase, 3 h after release from a double-thymidine block, and association was minimal at 9 h, when the majority of cells were in the G2 and M phases (Fig. 5C). Then the wild type protein was associated with chromatin in the G1 phase of the following cell cycle. This pattern of dissociation and association in the cell cycle correlated with the cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation pattern of endogenous ORC2 shown in Fig. 2, A and B. In contrast, the phosphomimetic ORC2 did not exhibit dissociation from chromatin, and association of the phosphodefective protein was greatly reduced without cell cycle dependence. These results support the hypothesis that phosphorylation of ORC2 dissociates the ORC from chromatin in a cell cycle-dependent manner.

Using the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay, we examined binding of the ORC to the human origins of replication located in the lamin B2 region (oriLB2) and in the upstream promoter region of Mcm4 (oriMcm4) (29) (Fig. 5D). LB2C1 and EX7 adjacent to oriLB2 and oriMcm4, respectively, were used as control regions for ChIP assays. FLAG-ORC2 wild type and phosphodefective proteins bound to both origins of replication, but phosphomimetic protein did not do so. The FLAG-ORC2 proteins exhibited no significant difference in the binding to LB2C1 or EX7 control region. Then cell cycle-dependent binding of the ORC to the human origins of replication was examined (Fig. 5E). As shown previously with endogenous ORC2 (19), the FLAG-ORC2 wild type protein bound to both origins of replication in G1/S phase cells but did not do so in G2/M phase cells. Although the phosphodefective protein bound to the origins of replication in cells in all phases, the phosphomimetic protein exhibited inefficiency in binding. The persistent binding of the phosphodefective protein suggests that dissociation of the ORC from origins of replication requires phosphorylation of ORC2. The defective binding of the phosphomimetic protein to chromatin and the replication origins suggests that phosphorylation of ORC2 prevents the ORC from binding to newly replicated DNA during the S phase.

DISCUSSION

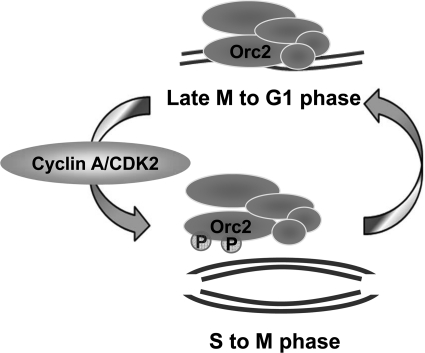

This report has demonstrated that Thr-116 and Thr-226 of human ORC2 are phosphorylated by CDK during the S phase (summarized in Fig. 6). Phosphorylation did not affect assembly of the ORC but led the ORC2–5 to dissociate from chromatin. ORC containing the wild type ORC2 protein bound to the origin of replication during the G1 phase and dissociated during the G2/M phase, but ORC containing phosphodefective ORC2 showed persistent binding throughout those phases of the cell cycle. ORC containing the phosphomimetic form of ORC2 exhibited defective binding in both the G1 and G2/M phase. These results indicate that phosphorylation of ORC2 reduces the affinity of ORC for the replication origins, thereby releasing the ORC from the origins. In addition, the inability of the ORC containing the phosphomimetic ORC2 to bind to the origins of replication suggests that phosphorylation prevents the ORC from binding to newly replicated DNA until phosphorylated ORC2 becomes dephosphorylated. Because ORC precedes other proteins in the initiation of chromosome replication, dissociating ORC from chromatin by cell cycle stage-specific phosphorylation of ORC2 will contribute to the regulation of chromosome replication initiation.

FIGURE 6.

ORC2 phosphorylation regulates the association of the ORC with chromatin and the replication origin.

In mammalian cells, ORC2–5 form a stable complex, and ORC1 and ORC6 are relatively weakly associated with ORC2–5 (12–14, 34). Although amounts of ORC2–5 subunits are constant throughout the cell cycle, ORC1 starts to accumulate in mid-G1 phase and to be degraded in early S phase (18). Also, chromatin-bound ORC1 decreases from S phase (12, 36, 37). The association of ORC1 with ORC2–5 is essential for chromatin binding of ORC2–5 and DNA replication (12, 36). The defective binding of phosphomimetic ORC2 to chromatin and replication origins (Fig. 5) suggests that the ORC2–5 binding requires the non-phosphorylated state of ORC2 in addition to ORC1. Phosphodefective ORC2 was not able to be dissociated from chromatin and replication origins (Fig. 5). Although calyculin A treatment decreased the amount of ORC1 bound to the G1 phase chromatin, ORC2–5 binding was not affected (Fig. 4B), suggesting that dissociation of ORC1 did not lead to dissociation of ORC2–5. These results imply that the dissociation of ORC2–5 depends upon ORC2 phosphophorylation at Thr-116 and Thr-226.

Results from immunofluorescence staining and chromatin fractionation have suggested that the human ORC becomes dissociated from chromatin as replication progresses to the S phase (15, 16). Origin trapping experiments have shown that the human ORC dissociates from the replication origins during the S phase and later in the cell cycle (19). The ORC2-GFP, which is diffusely distributed in nuclear area during early mitosis, binds rapidly to anaphase chromatin in Drosophila embryos (38). In the Xenopus egg extract system, cyclin A-CDK dissociates the ORC, Cdc6, and Mcm2–7 from chromatin (20, 39). In S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, ORC2 is phosphorylated by CDK (25, 40). Mutations of CDK phosphorylation sites cause defective cell cycle progression and/or rereplication (23–25). In addition to the mutations of CDK phosphorylation sites at ORC2 and ORC6, deregulation of both Cdc6 and Mcm2–7 was necessary for reinintiation of DNA replication in S. cerevisae (25). Although the yeast ORC has been shown to bind to ARS throughout the cell cycle, recent reports have suggested that ORC binding is dynamic (19, 38, 41). These results may suggest that ORC phosphorylation in other organisms is also involved in dissociation of the ORC from origins of replication.

CDKs control DNA replication as well as cell cycle progression of eukaryote cells. In particular, cyclin A-CDK, a major CDK for cell cycle progression during the S phase of mammalian cells, plays a critical role in the regulation of pre-RC proteins (5). The phosphorylation of Cdt1 by cyclin A-CDK2 induces the ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic degradation of Cdt1 via interaction with the F-box protein Skp2 (42). Cyclin A-CDK2 aids in the translocation of Cdc6 during transition from the S to G2 phase (43, 44). In addition, Mcm4/6/7 helicase activity is inhibited by Mcm4 phosphorylation by cyclin A-CDK2 (45). In vitro CDK phosphorylation of Drosophila melanogaster ORC1 and ORC2 inhibits DNA binding and ATPase activity of ORC (22). In yeast, S phase CDKs negatively regulate ORC2, Cdc6, Cdt1, and Mcm2–7, probably as a way to inhibit de novo assembly of pre-RC in the S phase (8, 46). Our study suggests that the phosphorylation of ORC2 by CDK caused dissociation of the ORC from chromatin and the origin of replication in the S phase of human cells. Therefore, CDK plays a central role in inactivating pre-RC proteins in the S phase.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Anindya Dutta for careful reading of the manuscript and for providing anti-ORC3 and -ORC5 antibodies.

This work was supported by National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry for Health and Welfare, Grant 1120180; Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant 2011-0008014 NRF; and Nuclear R&D Program of National Research Foundation of Korea Grant 2009-0078699.

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–4.

- pre-RC

- prereplicative complex

- α-pT116

- anti-phospho-Thr-116 ORC2 antibody

- α-pT226

- anti-phospho-Thr-226 ORC2 antibody

- CDK

- cyclin-dependent kinase

- ORC

- origin recognition complex

- ORC2–5

- ORC2, -3, -4, and -5 subunits.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bell S. P., Dutta A. (2002) DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 333–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Diffley J. F. (2004) Regulation of early events in chromosome replication. Curr. Biol. 14, R778–R786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sclafani R. A., Holzen T. M. (2007) Annu. Rev. Genet. 41, 237–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blow J. J., Dutta A. (2005) Preventing re-replication of chromosomal DNA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 476–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DePamphilis M. L., Blow J. J., Ghosh S., Saha T., Noguchi K., Vassilev A. (2006) Regulating the licensing of DNA replication origins in metazoa. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tsakraklides V., Bell S. P. (2010) Dynamics of prereplicative complex assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9437–9443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Evrin C., Clarke P., Zech J., Lurz R., Sun J., Uhle S., Li H., Stillman B., Speck C. (2009) A double-hexameric MCM2–7 complex is loaded onto origin DNA during licensing of eukaryotic DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 20240–20245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen S., Bell S. P. (2011) CDK prevents Mcm2–7 helicase loading by inhibiting Cdt1 interaction with Orc6. Genes Dev. 25, 363–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bell S. P., Stillman B. (1992) ATP-dependent recognition of eukaryotic origins of DNA replication by a multiprotein complex. Nature 357, 128–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dutta A., Bell S. P. (1997) Initiation of DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13, 293–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vashee S., Cvetic C., Lu W., Simancek P., Kelly T. J., Walter J. C. (2003) Sequence-independent DNA binding and replication initiation by the human origin recognition complex. Genes Dev. 17, 1894–1908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giordano-Coltart J., Ying C. Y., Gautier J., Hurwitz J. (2005) Studies of the properties of human origin recognition complex and its Walker A motif mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 69–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ranjan A., Gossen M. (2006) A structural role for ATP in the formation and stability of the human origin recognition complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4864–4869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dhar S. K., Yoshida K., Machida Y., Khaira P., Chaudhuri B., Wohlschlegel J. A., Leffak M., Yates J., Dutta A. (2001) Replication from oriP of Epstein-Barr virus requires human ORC and is inhibited by geminin. Cell 106, 287–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kreitz S., Ritzi M., Baack M., Knippers R. (2001) The human origin recognition complex protein 1 dissociates from chromatin during S phase in HeLa cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 6337–6342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Siddiqui K., Stillman B. (2007) ATP-dependent assembly of the human origin recognition complex. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 32370–32383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Méndez J., Zou-Yang X. H., Kim S. Y., Hidaka M., Tansey W. P., Stillman B. (2002) Human origin recognition complex large subunit is degraded by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis after initiation of DNA replication. Mol. Cell 9, 481–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tatsumi Y., Ohta S., Kimura H., Tsurimoto T., Obuse C. (2003) The ORC1 cycle in human cells. I. Cell cycle-regulated oscillation of human ORC1. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41528–41534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gerhardt J., Jafar S., Spindler M. P., Ott E., Schepers A. (2006) Identification of new human origins of DNA replication by an origin-trapping assay. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 7731–7746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Findeisen M., El-Denary M., Kapitza T., Graf R., Strausfeld U. (1999) Cyclin A-dependent kinase activity affects chromatin binding of ORC, Cdc6, and MCM in egg extracts of Xenopus laevis. Eur. J. Biochem. 264, 415–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laman H., Peters G., Jones N. (2001) Cyclin-mediated export of human Orc1. Exp. Cell Res. 271, 230–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Remus D., Blanchette M., Rio D. C., Botchan M. R. (2005) CDK phosphorylation inhibits the DNA-binding and ATP-hydrolysis activities of the Drosophila origin recognition complex. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 39740–39751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vas A., Mok W., Leatherwood J. (2001) Control of DNA rereplication via Cdc2 phosphorylation sites in the origin recognition complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 5767–5777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Makise M., Takehara M., Kuniyasu A., Matsui N., Nakayama H., Mizushima T. (2009) Linkage between phosphorylation of the origin recognition complex and its ATP binding activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3396–3407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nguyen V. Q., Co C., Li J. J. (2001) Cyclin-dependent kinases prevent DNA re-replication through multiple mechanisms. Nature 411, 1068–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li C. J., Vassilev A., DePamphilis M. L. (2004) Role for Cdk1 (Cdc2)/cyclin A in preventing the mammalian origin recognition complex's largest subunit (Orc1) from binding to chromatin during mitosis. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 5875–5886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Braunstein M., Rose A. B., Holmes S. G., Allis C. D., Broach J. R. (1993) Transcriptional silencing in yeast is associated with reduced nucleosome acetylation. Genes Dev. 7, 592–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen H., Lin R. J., Xie W., Wilpitz D., Evans R. M. (1999) Regulation of hormone-induced histone hyperacetylation and gene activation via acetylation of an acetylase. Cell 98, 675–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ladenburger E. M., Keller C., Knippers R. (2002) Identification of a binding region for human origin recognition complex proteins 1 and 2 that coincides with an origin of DNA replication. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 1036–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Geley S., Kramer E., Gieffers C., Gannon J., Peters J. M., Hunt T. (2001) Anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome-dependent proteolysis of human cyclin A starts at the beginning of mitosis and is not subject to the spindle assembly checkpoint. J. Cell Biol. 153, 137–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ubersax J. A., Ferrell J. E., Jr. (2007) Mechanisms of specificity in protein phosphorylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 530–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Malumbres M., Barbacid M. (2009) Cell cycle, CDKs, and cancer. A changing paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Woetmann A., Nielsen M., Christensen S. T., Brockdorff J., Kaltoft K., Engel A. M., Skov S., Brender C., Geisler C., Svejgaard A., Rygaard J., Leick V., Odum N. (1999) Inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A induces serine/threonine phosphorylation, subcellular redistribution, and functional inhibition of STAT3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10620–10625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vashee S., Simancek P., Challberg M. D., Kelly T. J. (2001) Assembly of the human origin recognition complex. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26666–26673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Prasanth S. G., Prasanth K. V., Siddiqui K., Spector D. L., Stillman B. (2004) Human Orc2 localizes to centrosomes, centromeres and heterochromatin during chromosome inheritance. EMBO J. 23, 2651–2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ohta S., Tatsumi Y., Fujita M., Tsurimoto T., Obuse C. (2003) The ORC1 cycle in human cells. II. Dynamic changes in the human ORC complex during the cell cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41535–41540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Noguchi K., Vassilev A., Ghosh S., Yates J. L., DePamphilis M. L. (2006) The BAH domain facilitates the ability of human Orc1 protein to activate replication origins in vivo. EMBO J. 25, 5372–5382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baldinger T., Gossen M. (2009) Binding of Drosophila ORC proteins to anaphase chromosomes requires cessation of mitotic cyclin-dependent kinase activity. Mol. Cell Biol. 29, 140–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sun W. H., Coleman T. R., DePamphilis M. L. (2002) Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the association between origin recognition proteins and somatic cell chromatin. EMBO J. 21, 1437–1446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lygerou Z., Nurse P. (1999) The fission yeast origin recognition complex is constitutively associated with chromatin and is differentially modified through the cell cycle. J. Cell Sci. 112, 3703–3712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. DePamphilis M. L. (2005) Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the origin recognition complex. Cell Cycle 4, 70–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sugimoto N., Tatsumi Y., Tsurumi T., Matsukage A., Kiyono T., Nishitani H., Fujita M. (2004) Cdt1 phosphorylation by cyclin A-dependent kinases negatively regulates its function without affecting geminin binding. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19691–19697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saha P., Chen J., Thome K. C., Lawlis S. J., Hou Z. H., Hendricks M., Parvin J. D., Dutta A. (1998) Human CDC6/Cdc18 associates with Orc1 and cyclin-Cdk and is selectively eliminated from the nucleus at the onset of S phase. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 2758–2767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Delmolino L. M., Saha P., Dutta A. (2001) Multiple mechanisms regulate subcellular localization of human CDC6. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26947–26954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ishimi Y., Komamura-Kohno Y., You Z., Omori A., Kitagawa M. (2000) Inhibition of Mcm4,6,7 helicase activity by phosphorylation with cyclin A/Cdk2. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 16235–16241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Arias E. E., Walter J. C. (2007) Strength in numbers. Preventing rereplication via multiple mechanisms in eukaryotic cells. Genes Dev. 21, 497–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.