Background: A GABRB3 mutation has been associated with childhood absence epilepsy and β3 subunit hyperglycosylation.

Results: The mutation altered subunit expression and reduced GABAA receptor function independent of N-glycosylation.

Conclusion: The mutation introduced a charged residue predicted to alter subunit interactions.

Significance: The distal N terminus of GABAA receptor subunits may play an unexpected role in receptor assembly and channel gating.

Keywords: Electrophysiology, Epilepsy, GABA Receptors, Glycosylation, Homology Modeling, Mutant

Abstract

A GABAA receptor β3 subunit mutation, G32R, has been associated with childhood absence epilepsy. We evaluated the possibility that this mutation, which is located adjacent to the most N-terminal of three β3 subunit N-glycosylation sites, might reduce GABAergic inhibition by increasing glycosylation of β3 subunits. The mutation had three major effects on GABAA receptors. First, coexpression of β3(G32R) subunits with α1 or α3 and γ2L subunits in HEK293T cells reduced surface expression of γ2L subunits and increased surface expression of β3 subunits, suggesting a partial shift from ternary αβ3γ2L receptors to binary αβ3 and homomeric β3 receptors. Second, β3(G32R) subunits were more likely than β3 subunits to be N-glycosylated at Asn-33, but increases in glycosylation were not responsible for changes in subunit surface expression. Rather, both phenomena could be attributed to the presence of a basic residue at position 32. Finally, α1β3(G32R)γ2L receptors had significantly reduced macroscopic current density. This reduction could not be explained fully by changes in subunit expression levels (because γ2L levels decreased only slightly) or glycosylation (because reduction persisted in the absence of glycosylation at Asn-33). Single channel recording revealed that α1β3(G32R)γ2L receptors had impaired gating with shorter mean open time. Homology modeling indicated that the mutation altered salt bridges at subunit interfaces, including regions important for subunit oligomerization. Our results suggest both a mechanism for mutation-induced hyperexcitability and a novel role for the β3 subunit N-terminal α-helix in receptor assembly and gating.

Introduction

Childhood absence epilepsy (CAE)2 is characterized by frequent absence seizures, during which patients manifest brief losses of consciousness and generalized synchronous 3-Hz spike-and-wave discharges on EEG. The seizures typically begin at age 3–8 years, continue through adolescence, last 3–10 s, and occur up to 200 times per day. CAE is highly genetic, and 16–45% of patients have a positive family history (1). Mutations, polymorphisms, and variants associated with CAE have been identified in several genes encoding ion channels, including T-type calcium (2–5), chloride (6), and GABAA receptor (7–9) channels.

GABAA receptors are pentameric, ligand-gated chloride channels that mediate the majority of fast inhibitory neurotransmission in the brain. They assemble from an array of 19 homologous subunits from eight subunit families as follows: α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ϵ, π, θ, and ρ1–3 (10). The predominant receptor isoforms in vivo likely contain two α, two β, and one γ or δ subunit (Fig. 1) (11–13); however, some subunits (notably β3 subunits) may assemble less discriminately, forming homopentamers as well as heteropentamers (14).

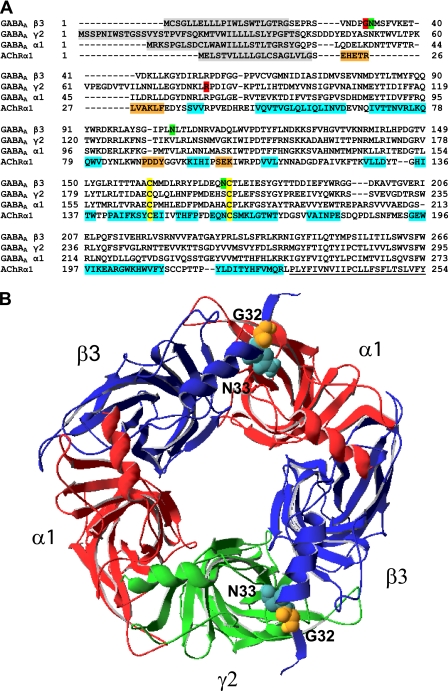

FIGURE 1.

G32R mutation was predicted to be adjacent to the first of three putative glycosylation sites in β3 subunits and to lie at subunit interfaces in assembled GABAA receptors. A, sequences of human α1, β3, and γ2L GABAA receptor subunits were aligned with the sequence of the human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α1 subunit (AChRα1). In the AChRα1 sequence, α-helices are highlighted in orange; β-sheets are highlighted in blue, and the first transmembrane domain is underlined. In the GABAA receptor β3 subunit sequence, putative N-glycosylation sites are highlighted in green. In all sequences, signal peptides are highlighted in gray, and the cysteines forming the Cys-loop are highlighted in yellow. Sites of epilepsy-associated mutations in GABAA receptor subunits (β3(G32R) and γ2(R82Q)) are highlighted in red. B, model of the α1β3γ2L GABAA receptor, as viewed from the synaptic cleft, is presented. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α1 subunit crystal structure (2qc1) was used to generate homology models of individual GABAA receptor subunits, which were threaded onto the L. stagnalis acetylcholine-binding protein crystal structure in the order γ2L-β3-α1-β3-α1. The α1, β3, and γ2L subunits are colored red, blue, and green, respectively. Glycine 32 and asparagine 33 are presented as orange and cyan space-filling models, respectively.

Three separate CAE-associated mutations were recently identified in GABAA receptor β3 subunits: GABRB3(P11S), GABRB3(S15F), and GABRB3(G32R) (15). Mutant subunit-containing receptors exhibited reduced current density. Moreover, the mutant proteins all appeared to be “hyperglycosylated,” because they migrated at higher molecular masses than wild type β3 subunits unless digested with an enzyme that removed all N-glycans. The investigators consequently hypothesized that hyperglycosylation might be responsible for the reduced current density, which might in turn lead to neuronal hyperexcitability and, ultimately, to the abnormal EEG patterns of absence seizures.

Approximately half of all eukaryotic proteins carry N-linked glycans (16). The process of N-linked glycosylation begins in the endoplasmic reticulum lumen, where standard “core” glycans are attached to the side chain nitrogen of asparagines located in the glycosylation consensus sequon, Asn-Xaa-(Ser/Thr) (Xaa ≠ Pro) (17, 18). Sequons containing threonine residues have higher glycan occupancy than sequons containing serine residues (19). N-Linked glycosylation serves several functions in the biogenesis of multimeric proteins. First, addition of glycans facilitates monomer folding and multimer assembly, thus preventing aggregation and degradation of newly synthesized subunits (20, 21). Furthermore, glycan conjugation may favor assembly of certain subunits, thereby determining subunit stoichiometry (22). Finally, N-linked glycosylation can affect functional properties of ion channels once they reach the cell surface (23). Perhaps unsurprisingly, most congenital disorders of glycosylation cause severe pathology, often with significant neurological involvement (24). However, these disorders generally impair rather than enhance glycan attachment and processing. In this study, we evaluated the possibility that the β3(G32R) subunit mutation, which is located adjacent to the first of three β3 subunit N-glycosylation sites (Fig. 1), might reduce GABAergic inhibition by aberrantly increasing glycosylation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Biology

Complementary DNAs (cDNAs) encoding individual human GABAA receptor subunits (α1, NM_000806.5; α3, NM_000808.3; β3 variant 2, NM_021912.4; and γ2L, NM_000816.3) were cloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) vector. The hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag (YPYDVPDYA) was inserted between amino acids 4 and 5 of the mature γ2L subunit protein. Point mutations were introduced using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). All constructs were sequenced by the Vanderbilt DNA core facility prior to use. Note that all amino acids are numbered according to the immature peptide sequence.

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK293T cell culture methods have been described previously (25). For immunoblotting, 1.2 × 106 cells were plated onto 100-mm diameter culture dishes; for flow cytometry, 4 × 105 cells were plated onto 60-mm diameter culture dishes; and for electrophysiology, 1 × 105 cells were plated onto 30-mm diameter culture dishes.

Twenty four hours after plating, cells were transfected with GABAA receptor subunit cDNAs using 3 μl of FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science) per 1 μg of subunit cDNA. For immunoblotting, 3 μg of each subunit cDNA was transfected (i.e. 9 μg of cDNA altogether); for other experiments, cDNA amounts were scaled proportionally to the number of cells plated. For “wild type” or “homozygous” subunit expression flow cytometry experiments, 60-mm culture dishes were transfected with 1 μg each α1 (or α3) and γ2LHA subunit cDNAs and 1.0 μg of β3 or β3(G32R) subunit cDNAs, respectively. For “heterozygous” expression flow cytometry experiments, 60-mm culture dishes were transfected with 1 μg each of α1 (or α3) and γ2LHA subunit cDNAs and 0.5 μg each of β3 and β3(G32R) subunit cDNAs. The terms wild type, heterozygous, and homozygous are used as a shorthand designation for the subunit expression conditions and are not meant to imply any genetic condition.

Surface Biotinylation

Biotinylation protocols have been described previously (25). Briefly, culture plates were washed, incubated with 1 mg/ml NHS-SS-biotin (Pierce) diluted in Dulbecco's PBS, and lysed with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (RIPA buffer; 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.1% Triton X-100, 250 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA) containing protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 15 min and subsequently incubated overnight with high capacity NeutrAvidin-agarose resin (Pierce). After overnight incubation, protein was eluted and subjected to immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting

Proteins in sample buffer were separated on 4–12% BisTris NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to Odyssey PVDF membranes (Li-Cor). A monoclonal antibody raised against intracellular residues 370–433 of the GABAA receptor β3 subunit (4 μg/ml, clone N87/25, UC Davis/NIH NeuroMab Facility) was used to detect β3 subunit protein, and anti-Na+/K+-ATPase antibody (0.2 μg/ml, clone 464.6, ab7671, Abcam) was used as a loading control. Anti-mouse IRdye conjugated secondary antibodies (Li-Cor) were used in all cases. Membranes were scanned using the Li-Cor Odyssey system, and integrated intensities of bands were determined using Odyssey software.

Glycosidase Digestion

Biotinylated protein was simultaneously eluted from NeutrAvidin resin and denatured by incubation in 1× glycoprotein denaturing buffer (New England Biolabs) containing 50 mm dithiothreitol for 30 min at 50 °C. Eluates were divided into 15-μl aliquots and digested with 1 unit of endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase H (endo H) or peptide-N-glycosidase F in manufacturer-supplied buffers (New England Biolabs) at 37 °C for 2 h.

Flow Cytometry

Staining protocols for flow cytometry have been described previously (25). GABAA receptor subunits were detected with antibodies to human α1 subunits (N terminus, clone BD24, Millipore; 2.5 μg/ml), human α3 subunits (N-terminal residues 29–43, polyclonal, Alomone; 1.5 μg/ml), or the HA epitope tag (clone 16B12, Covance; 2.5 μg/ml). The Molecular Probes monoclonal antibody labeling kit (Invitrogen), used per manufacturer's instructions, was previously used to directly conjugate Alexa647 fluorophores to anti-α1 subunit and anti-HA tag antibodies. Following antibody incubation, cells were washed three times with FACS buffer and either fixed with 2% w/v paraformaldehyde, 1 mm EDTA diluted in PBS (anti-α1, anti-HA) or incubated with anti-mouse IgG1 secondary antibody conjugated to the Alexa647 fluorophore (Invitrogen; anti-α3) before additional washing and fixation.

For total cellular protein detection, cells were permeabilized for 15 min with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) and washed twice with 1× PermWash (BD Biosciences) before antibody incubation. For these experiments, all antibodies were diluted to 2.5 μg/ml in PermWash. After antibody incubation, cells were washed four times in PermWash and twice in FACS buffer before fixation with 2% w/v paraformaldehyde, 1 mm EDTA diluted in PBS.

Fluorescence intensity (FI) of all samples was determined using an LSR II 5-laser flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed off line with FlowJo 7.5 (Tree Star). For each sample, 50,000 total events were acquired; nonviable cell populations, determined in control experiments by staining with 7-amino-actinomycin D, were excluded from analysis. For all experiments, the net FI of samples was determined by subtracting the mean FI of cells transfected with blank pcDNA(3.1+) vector from the mean FI of cells expressing GABAA receptor subunits. The relative fluorescence intensity (“relative FI”) for each condition was calculated by normalizing the net FI of each experimental condition to the net FI of cells expressing wild type β3 subunits.

Whole Cell Electrophysiology

Whole cell voltage clamp recordings were performed at room temperature on lifted HEK293T cells 24–72 h after transfection with GABAA receptor subunits as described previously (7). Briefly, cells were bathed in an external solution containing 142 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 8 mm KCl, 6 mm MgCl2, 10 mm glucose, and 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4 (∼325 mosm), and recording electrodes were filled with an internal solution containing 153 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES, 5 mm EGTA, 2 mm Mg2+-ATP, pH 7.3 (∼300 mosm). All patch electrodes had a resistance of 1–2 megaohms. Cells were voltage-clamped at −20 mV using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). A rapid exchange system (open tip exchange times ∼400 μs), composed of a four-barrel square pipette attached to a perfusion fast step (Warner Instruments Corp., Hamden, CT) and controlled by Clampex 9.0 (Axon Instruments), was used to apply GABA to lifted whole cells. All currents were low pass filtered at 2 kHz, digitized at 5–10 kHz, and analyzed using the pCLAMP 9 software suite.

Single Channel Electrophysiology

Cell-attached single channel recording was performed as described previously (7). Briefly, HEK293T cells expressing GABAA receptor subunits were bathed in an external solution containing 140 mm NaCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm glucose, and 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4. Recording electrodes were filled with an internal solution containing 1 mm GABA, 120 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm CaCl2, 5 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm glucose, and 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, and electrode potential was held at +80 mV. The electrodes were polished to a resistance of 10–20 megohms.

Single channel currents were amplified and low pass filtered at 2 kHz using an Axopatch 200B amplifier, digitized at 20 kHz using Digidata 1322A, and saved using pCLAMP 9 software (Axon Instruments). Data were analyzed using TAC 4.2, and open time and amplitude histograms were generated using TACFit (Bruxton Corp., Seattle, WA) as described previously (10). The number of components required to fit the duration histograms was increased until an additional component did not significantly improve the fit (26). Single channel openings occurred as bursts of one or more openings or clusters of bursts. Bursts were defined as one or more consecutive openings that were separated by closed times that were shorter than a specified critical duration (tcrit) prior to and following the openings (27). A tcrit of 5 ms was used in this study. Clusters were defined as a series of bursts preceded and followed by closed intervals longer than a specific critical duration (tcluster). A tcluster of 10 ms was used in this study.

Homology Modeling

Multiple sequence alignments of human GABAA receptor α1, β3, and γ2L subunits and the human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) α1 subunit were performed using ClustalW (European Bioinformatics Institute, Hinxton, UK). Structural models of GABAA receptor N-terminal domains were generated with SWISS-MODEL (28), using the crystal structure of the nAChR α1 subunit (Protein Data Bank code 2qc1) (29) as a template. Point mutations were introduced into the β3 subunit sequence using DeepView/Swiss-PdbViewer 4.02 (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Lausanne, Switzerland), and SWISS-MODEL project files containing the mutated target sequence and the superposed template structure were submitted. For heteropentamers, subunits were threaded in the order γ2L-β3-α1-β3-α1 onto the Lymnaea stagnalis acetylcholine-binding protein crystal structure (Protein Data Bank code 1i9b) (30) used as a template. All models were energy-optimized using GROMOS96 in default settings within DeepView/Swiss-PdbViewer, and the most likely conformations were presented here.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism version 5.04 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Student's two-tailed t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's and/or Bonferroni's post-tests was used as appropriate to determine statistical significance among transfection conditions. Levels of significance were indicated in figure legends, and all data were expressed as mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

Cotransfection of Mutant β3(G32R) Subunit with α1 or α3 and γ2LHA Subunits Was Associated with Increased β3 Subunit and Decreased γ2LHA Subunit Surface Expression

Because the β3(G32R) mutation was reported to reduce the current density of heterologously expressed α1β3γ2L receptors (15), we sought to determine whether the mutation reduced surface expression of the GABAA receptor subunits under similar conditions. First, we transiently coexpressed α1, γ2LHA, and either wild type β3 or mutant β3(G32R) subunit cDNAs at a 1:1:1 ratio in HEK293T cells and assessed surface expression of all subunits using surface biotinylation and Western blotting.

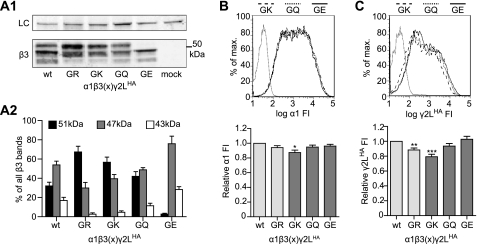

Immunoblotting revealed two major differences between β3 and β3(G32R) subunit proteins (Fig. 2A). First, although both wild type and mutant subunits migrated as three bands with molecular masses of ∼51, 47, and 43 kDa, the distribution of protein among those bands differed considerably (Fig. 2A1). Specifically, a larger fraction of mutant subunits migrated at the higher molecular masses. Second, surprisingly mutant β3(G32R) subunit surface levels were increased significantly (154 ± 15% of wild type, n = 17, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2A2).

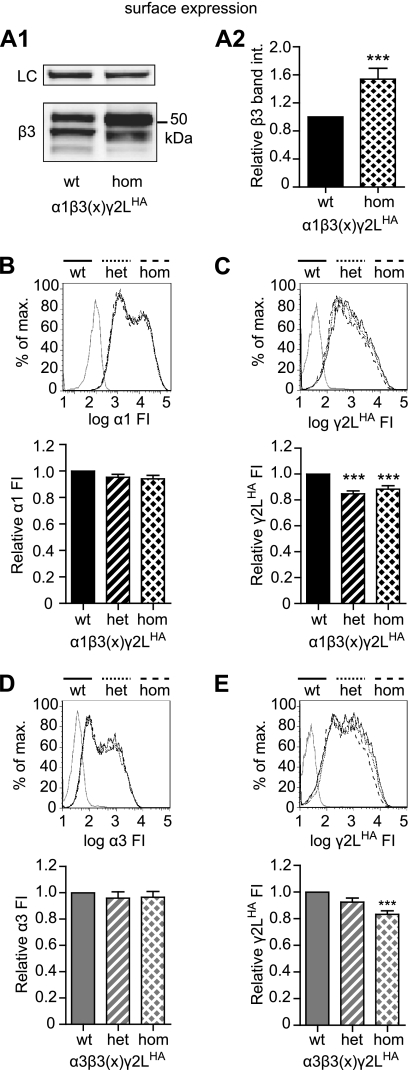

FIGURE 2.

Cells expressing α1 or α3, β3(G32R), and γ2LHA subunits had higher surface levels of β3 subunits and lower surface levels of γ2LHA subunits compared with cells expressing α1 or α3, β3(WT), and γ2LHA subunits. A1, surface protein was isolated from HEK293T cells transfected with equimolar amounts of α1, γ2LHA, and either wild type (wt) or G32R mutant (hom) β3 GABAA receptor subunit cDNA, separated by SDS-PAGE, and evaluated using Western blots. The upper panel presents staining for Na+/K+-ATPase as a loading control (LC), and the lower panel presents staining for β3 subunits (see under “Experimental Procedures” for antibody descriptions). A2, surface protein levels of β3 subunits were quantified in HEK293T cells transfected with equimolar amounts of α1, γ2LHA, and either wild type (wt) or G32R mutant (hom) β3 GABAA receptor subunits. Integrated band intensities of all β3 subunits were determined, summed, and normalized to integrated band intensities of Na+/K+-ATPase for the same sample. The normalized intensities of β3 subunits were then expressed as proportions of wild type β3 subunit intensities. Statistical significance was determined using Student's two-tailed paired t test. B and C, flow cytometry was used to evaluate surface protein levels of α1 (B) and γ2LHA (C) subunits in HEK293T cells transfected with α1, γ2LHA, and wild type and/or G32R mutant β3 GABAA receptor subunit cDNA. Wild type and homozygous mutant (hom) expression were modeled by transfecting 1 μg each of α1, γ2LHA, and either wild type or G32R mutant (hom) β3 subunit cDNA. Heterozygous mutant expression (het) was modeled by transfecting 1 μg each of α1 and γ2LHA cDNA together with 0.5 μg each of β3 and β3(G32R) subunit cDNA. Upper panels present fluorescence intensity histograms; the abscissa indicates FI in arbitrary units plotted on a logarithmic scale, and the ordinate indicates percentage of maximum cell count (% of max). Histograms for cells transfected with blank vector (solid gray line), or WT (solid black line), heterozygous (dotted black line), and homozygous (dashed black line) subunit combinations are overlaid. Lower panels present normalized fluorescence intensities for each expression condition. Mean fluorescence intensities from cells transfected with blank vector alone (mock) were subtracted from mean fluorescence intensities of WT, heterozygous, and homozygous expression conditions. All mock-subtracted fluorescence intensities were normalized to the mock-subtracted fluorescence intensity of the WT expression condition. D–E, flow cytometry was used to evaluate surface protein levels of α3 (D) and γ2LHA (E) subunits in HEK293T cells transfected with α3, γ2LHA, and wild type and/or G32R mutant β3 subunit cDNA. All panels are presented as described in B and C, but in all cases α3 subunit cDNA was substituted for α1 subunit cDNA. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test. *** indicates p < 0.001 compared with WT.

Because it would be highly unusual for a mutation to cause both an increase in surface receptor number and a reduction in current density, we first addressed the differences in wild type and mutant subunit expression levels. Increases in β3 subunit surface expression could reflect either a change in receptor subunit composition, including production of α1β3 receptors and/or β3 subunit homomers, or an overall increase in surface α1β3γ2L receptor number. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we first examined the differences in wild type and mutant partnering subunit expression levels. Immunoblotting for surface levels of partnering subunits suggested that α1 subunit levels did not change but γ2LHA subunit levels decreased when coexpressed with β3(G32R) rather than β3 subunits (data not shown), indicating a potential change in receptor subunit composition. Because the reduction of γ2LHA surface levels was subtle, we employed flow cytometry to confirm and quantify changes in subunit expression levels. In these experiments, we also included a condition modeling heterozygous expression of β3(G32R) subunits, in which an equimolar mixture of both β3 and β3(G32R) subunit cDNA was cotransfected with α1 and γ2LHA subunit cDNAs (see under “Experimental Procedures” for exact subunit cDNA ratios and concentrations). Consistent with the prior immunoblotting data, α1 subunit surface levels did not differ significantly in the heterozygous or homozygous mutant conditions (Fig. 2B), but γ2LHA subunit surface levels were decreased slightly in both heterozygous (84.8 ± 2.2% of wild type, n = 10, p < 0.001) and homozygous mutant (87.1 ± 2.4% of wild type, n = 16, p < 0.001) conditions (Fig. 2C).

We chose to coexpress α1 and γ2 subunits because they are the most widely expressed subunits of their respective families in whole brain; however, subunit expression patterns vary widely among brain regions. Several studies have indicated that absence seizures frequently involve dysfunction in the thalamic reticular nucleus, where the α3 subunit subtype predominates, and β3 subunit expression is also high (31). Consequently, we also examined changes in partnering subunit expression levels using α3 rather than α1 subunit cDNA. Results resembled those obtained using α1 subunits, i.e. α3 subunit surface levels did not differ significantly among wild type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant receptors (Fig. 2D), but γ2LHA subunit surface levels decreased in both heterozygous and homozygous mutant conditions, although the reduction was significant only in the homozygous mutant condition (Fig. 2E).

Changes in subunit surface expression could reflect alterations in subunit production, subunit stability, or receptor trafficking. Therefore, we also assessed total cellular subunit levels (Fig. 3) in the same conditions used to study surface expression (Fig. 2). Interestingly, coexpressing α1, β3(G32R), and γ2LHA subunits yielded no significant changes in β3 (Fig. 3, A1 and A2), α1 (Fig. 3B), or γ2LHA (Fig. 3C) subunit total cellular expression among wild type and heterozygous and homozygous mutant transfections. Likewise, coexpressing α3, β3(G32R) and γ2LHA subunits yielded no significant changes in α3 (Fig. 3D) or γ2LHA (Fig. 3E) subunit total cellular expression.

FIGURE 3.

β3(G32R) mutation did not significantly affect total cellular levels of GABAA receptor subunits in cells expressing α1 or α3, β3, and γ2LHA subunits. A1, total cell lysates (40 μg) were obtained from HEK293T cells transfected with equimolar amounts of α1, γ2LHA, and either wild type or G32R mutant (hom) β3 subunit cDNA, separated by SDS-PAGE, and evaluated using Western blots. The upper panel presents staining for Na+/K+-ATPase as a loading control (LC), and the lower panel presents staining for β3 subunits (see under “Experimental Procedures” for antibody descriptions). A2, total cellular levels of β3 subunits were quantified in HEK293T cells transfected with equimolar amounts of α1, γ2LHA, and either wild type or G32R mutant (hom) β3 GABAA receptor subunits. Integrated band intensities of all β3 subunit populations were determined, summed, and normalized to integrated band intensities of Na+/K+-ATPase for the same sample. The normalized intensities of β3 subunits were then expressed as proportions of wild type β3 subunit intensities. Statistical significance was determined using Student's two-tailed paired t test. B and C, flow cytometry was used to evaluate total cellular levels of α1 (B) and γ2LHA (C) subunits in HEK293T cells transfected with α1, γ2LHA, and wild type and/or G32R mutant β3 subunit cDNA and permeabilized before staining with fluorescently conjugated antibodies. Wild type (wt), heterozygous (het), and homozygous (hom) expression patterns were modeled as described for Fig. 1. Upper panels present fluorescence intensity histograms; the abscissa indicates FI in arbitrary units plotted on a logarithmic scale, and the ordinate indicates percentage of maximum cell count (% of max). Histograms for cells transfected with blank vector (solid gray line), or WT (solid black line), heterozygous (dotted black line), and homozygous (dashed black line) subunit combinations are overlaid. Lower panels present normalized fluorescence intensities for each expression condition. Mean fluorescence intensities from cells transfected with blank vector alone (mock) were subtracted from mean fluorescence intensities of WT, homozygous, and homozygous expression conditions. All mock-subtracted fluorescence intensities were normalized to the mock-subtracted fluorescence intensity of the WT expression condition. D and E, flow cytometry was used to evaluate total cellular levels of α3 (D) and γ2LHA (E) subunits in HEK293T cells transfected with α1, γ2LHA, and wild type and/or G32R mutant β3 GABAA receptor subunit cDNA and permeabilized before staining with fluorescently conjugated antibodies. All panels are presented as described in B and C, but in all cases α3 subunit cDNA was substituted for α1 subunit cDNA. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test.

β3 Subunit Mutation, G32R, Affected Subunit Surface Expression Independent of Glycosylation

To this point, we observed two principal effects of the β3 subunit mutation, G32R. First, mutant and wild type receptors had different surface expression patterns (specifically, a small decrease in γ2L subunit levels and a large increase in β3 subunit levels); these changes suggested a partial replacement of α1β3γ2L receptors by α1β3 receptors and β3 subunit homopentamers. Second, β3(G32R) subunits were more likely than β3 subunits to migrate at the highest of three distinct molecular mass populations. However, it remained unclear if there was a causal relationship between these two phenomena.

Because the mutant subunit had been reported to be hyperglycosylated, we hypothesized that the multiple β3 subunit bands represented differently glycosylated protein populations, where individual sequons may or may not be occupied by a glycan, occupancy patterns may or may not be uniform within a protein population (e.g. among all β3(G32R) subunits), and the glycans themselves may contain different combinations of monosaccharides. To determine whether the multiple β3 subunit bands represented differently glycosylated protein populations and to characterize β3 subunit N-glycans, we isolated surface protein from HEK293T cells expressing α1, γ2LHA, and either β3 or β3(G32R) subunits and compared the migration patterns of β3 and β3(G32R) subunits that were undigested; digested with endo H, which cleaves only high mannose, unprocessed glycans; or digested with peptide-N-glycosidase F, which removes all N-glycans regardless of modification (Fig. 4A). After digestion with peptide-N-glycosidase F, both β3 and β3(G32R) subunits migrated as one 43-kDa band, indicating that the G32R mutation did indeed increase N-glycosylation of at least one of the three β3 subunit sequons (Fig. 4A, 3rd and 6th lanes). Interestingly, β3 and β3(G32R) subunits also displayed different endo H digestion patterns; after endo H digestion, a substantial population of β3 subunits migrated at 43 kDa and thus were fully endo H-sensitive, but virtually none of the β3(G32R) subunits migrated at 43 kDa and thus were endo H-resistant. Therefore, the G32R mutation increased the efficiency of both addition and processing of N-glycans.

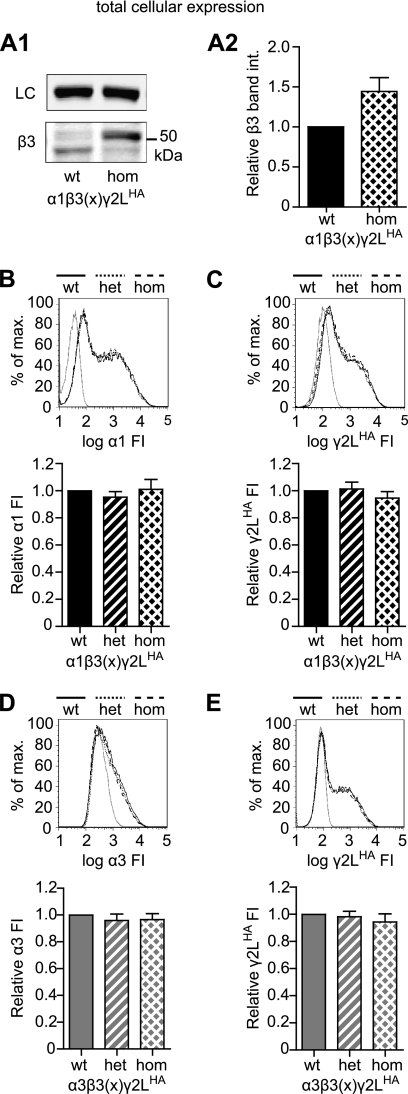

FIGURE 4.

β3(G32R) mutation increased glycosylation of Asn-33 and reduced γ2LHA subunit surface expression independent of glycosylation at Asn-33. A, surface protein was isolated from HEK293T cells expressing equimolar amounts of α1, γ2LHA, and either β3 or β3(G32R) subunits and left undigested (U) or digested with endoglycosidase H (H) or peptide N-glycosidase F (F). B, surface protein was isolated from HEK293T cells expressing equimolar amounts of α1 and either β3 or β3(G32R) subunits and left undigested (U) or digested with endoglycosidase H (H) or peptide N-glycosidase F (F). C, surface protein was isolated from HEK293T cells expressing equimolar amounts of either β3 or β3(G32R) subunits and left undigested (U) or digested with endoglycosidase H (H) or peptide N-glycosidase F (F). D and E, surface (D) or total cellular (E) protein was isolated from HEK293T cells expressing equimolar amounts of α1, γ2LHA, and different β3 subunits. The β3 subunit cDNA constructs were modified to inactivate (with an Asn to Gln mutation) or enhance (with a Ser to Thr mutation) the putative N-glycosylation sites of β3 subunits. In lane 1, the β3 subunit had no mutations (wt), and in lane 2, the β3 subunit had the G32R mutation only (GR). The three glycosylation sites (Asn-33, Asn-105, and Asn-174) were inactivated individually in the absence (lane 3, 1Q; lane 5, 2Q; and lane 7, 3Q) or the presence (lane 4, GR/1Q; lane 6, GR/2Q; lane 8, GR/3Q) of the G32R mutation. The first glycosylation site was also enhanced in either the absence (lane 9, ST) or the presence (lane 10, GR/ST) of the G32R point mutation. The upper panel presents staining for Na+/K+-ATPase as a loading control (LC), and the lower panel presents staining for β3 subunits. F and G, surface levels of α1 (F) and γ2LHA (G) subunits in cells expressing α1, γ2LHA, and glycosylation sequon mutant β3 subunits were determined using flow cytometry. The β3 subunit transfected in each condition is labeled as described in D and E. Upper panels present fluorescence intensity histograms in which the abscissa denotes fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units graphed on a logarithmic scale (log FI) and the ordinate denotes percentage of maximum cell count (% of max). Fluorescence intensity histograms from mock-transfected cells (solid gray line) are overlaid with histograms from cells expressing α1, γ2LHA, and β3 subunits that either lacked (solid black line) or contained (dashed black line) the G32R point mutation. In the left panels, either β3 (wt, solid) or β3(G32R) (GR, dashed) subunit cDNAs were transfected; in the middle panels, either β3(N33Q) (1Q, solid) or β3(G32R/N33Q) (GR/1Q, dashed) subunit cDNAs were transfected; and in the right panels, either β3(S35T) (ST, solid) or β3(G32R/S35T) (GR/ST, dashed) subunit cDNAs were transfected. The lower panels present normalized fluorescence intensities for each expression condition. Mean fluorescence intensities from cells transfected with blank vector alone (mock) were subtracted from mean fluorescence intensities of cells transfected with α1, γ2LHA, and the indicated β3 subunits. All mock-subtracted fluorescence intensities were normalized to the mock-subtracted fluorescence intensity of the cells expressing β3 subunits. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post-test was used to compare normalized fluorescence intensities of each glycosylation sequon pair (i.e. WT versus GR, 1Q versus GR/1Q, and ST versus GR/ST). **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

We recently established that partnering subunit incorporation could alter glycosylation patterns of β2 subunits (25). Thus, it was possible that the increased endo H-resistant population of β3(G32R) subunits reflected increased formation of α1β3 and/or β3 receptor isoforms. To assess this possibility, we studied the digestion pattern of wild type β3 and mutant β3(G32R) subunits after transfecting α1 and β3 (Fig. 4B) or only β3 (Fig. 4C) subunit cDNA. We found that the increased glycosylation and glycan processing of β3(G32R) mutant subunits compared with β3 subunits persisted in the absence of α1 and/or γ2L partnering subunits. Interestingly, the proportion of endo H-sensitive β3 subunits did decrease with the number of subunits expressed, i.e. endo H sensitivity was greatest in α1β3γ2LHA receptors, lower in α1β3 receptors, and lowest in β3 receptors.

These results demonstrating altered glycosylation of β3(G32R) subunits contradicted in silico analysis. We used NetNGlyc 1.0 to establish that the G32R mutation did not change the occupancy potential of Asn-105 (0.7904) or Asn-174 (0.6229), but it slightly reduced the occupancy potential of Asn-33 (β3 0.5947, β3(G32R) 0.5239) (data not shown). Similarly, meta-analyses have concluded that sequons with Arg at the −1 position are considerably less likely to be glycosylated than sequons with Gly at the −1 position (32). Finally, although hypoglycosylation disorders frequently cause severe pathology (24), to our knowledge there are no reports of increased glycosylation adversely affecting function or trafficking of other receptors.

After confirming that β3 and β3(G32R) subunits had different glycosylation patterns, we sought to determine whether the increased glycosylation and glycan processing of β3(G32R) mutant subunits were indeed responsible for changes in subunit surface trafficking. To identify the occupancy of a particular sequon for both wild type and mutant receptors, we mutated each potentially glycosylated asparagine residue (N-glycosylation sites Asn-33, Asn-105, and Asn-174) individually to glutamine in wild type β3 and mutant β3(G32R) subunits, thereby creating glycosylation-defective subunits (23, 25, 33, 34). We could not eliminate the possibility that these point mutations themselves could alter receptor assembly or function; however, we compared the characteristics of glycosylation-defective subunits bearing or lacking the G32R mutation. Furthermore, in a previous study we addressed several concerns regarding this method (25).

Consistent with previous results, β3 and β3(G32R) subunits displayed clear differences in molecular mass distribution when all three glycosylation sites remained intact. If this difference reflected increased glycosylation of β3(G32R) subunits at one specific site (i.e. Asn-33, Asn-105, or Asn-174), inactivating that site with an Asn to Gln mutation (“NQ mutation”) should yield proteins with identical molecular mass distributions. Moreover, the 51-kDa band, which presumably represented triply glycosylated proteins, should disappear in any subunit bearing an NQ mutation. Therefore, we coexpressed α1 and γ2LHA subunits with each wild type/glycosylation-deficient β3 subunit (N33Q, N105Q, and N174Q; labeled as 1Q, 2Q, and 3Q, respectively) and each mutant/glycosylation-deficient β3 subunit (G32R/N33Q, G32R/N105Q, and G32R/N174Q; labeled as GR/1Q, GR/2Q, and GR/3Q, respectively) (Fig. 4, D and E). Immunoblotting for wild type β3 subunit surface and total protein yielded several interesting results. Most strikingly, inactivating the second or third glycosylation site (2Q or 3Q) drastically reduced expression of wild type β3 subunits; indeed, expression of β3(2Q) subunits was nearly abolished. Although intriguing, these deficits in protein expression made it impossible to compare the glycosylation patterns of these second and third glycosylation site mutants in the presence or absence of the G32R mutation and thus to determine conclusively if the molecular mass shifts in glycosylation-competent β3(G32R) subunits were due to increased occupancy of the second or third glycosylation sites. Nonetheless, these data indirectly suggest that glycosylation of Asn-105 or Asn-174 was not responsible for the molecular mass shift; given that disruption of these sites so drastically reduced protein expression, it seems likely that both sites are usually glycosylated and therefore could not have their occupancy increased by the G32R mutation.

Inactivating the first glycosylation site (1Q) produced remarkably different effects (Fig. 4, D and E). First, β3(N33Q) subunit expression levels were not significantly reduced compared with wild type β3 subunit levels. Conversely, combining the G32R and N33Q mutations (GR/1Q) significantly reduced surface and total β3 subunit levels relative to both β3 and β3(N33Q) subunit levels. Despite the difference in overall β3 subunit levels, β3(N33Q) and β3(G32R/N33Q) subunits had similar molecular mass distributions, suggesting that the G32R mutation may indeed have facilitated Asn-33 glycosylation.

The β3 subunit constructs with NQ mutations allowed us to examine the effects of the G32R mutation in the absence of N-glycosylation at specific sequons. However, when all glycosylation sites were intact, the G32R mutation appeared to increase β3 subunit glycosylation; therefore, it was valuable to examine the effects of the mutation when both wild type β3 and mutant β3(G32R) subunits had increased glycosylation. It is not possible to force glycosylation of individual sequons, but it is well known that NXT sequons are much more likely than NXS sequons to accept N-glycans. As described above, expression of glycosylation-deficient constructs indicated that the Asn-33 site (sequon NMS) was more likely to be occupied in the presence of the G32R mutation. Therefore, we hypothesized that β3 subunits in which Ser-35 was mutated to Thr (β3(S35T) subunits; ST) would exhibit a glycosylation pattern similar to that of β3(G32R) subunits. As shown in Fig. 4, D and E, the S35T mutation did increase glycosylation of β3 subunits, but the G32R mutation did not increase glycosylation further, i.e. β3(S35T) and β3(G32R/S35T) subunits exhibited similar molecular mass distributions. Taken together, these results indicated that the G32R mutation increased β3 subunit N-glycosylation at Asn-33.

However, it remained unclear whether glycosylation at Asn-33 was responsible for decreased γ2LHA subunit surface incorporation. We therefore evaluated levels of partnering subunits when coexpressed with β3(N33Q), β3(G32R/N33Q), β3(S35T), or β3(G32R/S35T) subunits. Surface levels of α1 subunits remained similar regardless of the coexpressed β3 subunit construct (Fig. 4F). Conversely, γ2LHA subunit surface levels decreased whenever the coexpressed β3 subunit contained the G32R mutation, but without regard to glycosylation site inactivation or strengthening (Fig. 4G). Thus, these data suggested that glycosylation was not the mechanism by which the G32R mutation reduced γ2L subunit incorporation and, potentially, GABAA receptor function.

Presence of a Basic Residue at Position 32 Reduced Surface Expression Levels of γ2L Subunits and Increased Glycosylation at Asn-33

If the change in glycosylation was not responsible for altered subunit expression patterns seen with mutant β3(G32R) subunits, some other property of the point mutation itself, such as charge, must have been causative. To investigate the effects of charge at residue 32, we mutated the β3 subunit residue Gly-32 to lysine, glutamine, or glutamate (G32K, G32Q, and G32E, respectively). We coexpressed each of these β3 subunits individually with α1 and γ2L subunits and evaluated glycosylation patterns of β3 subunits and surface levels of all subunits (Fig. 5). Interestingly, our results suggested that glycosylation of Asn-33 clearly depended upon the charge of residue 32. Thus, 32.0 ± 3.9% of all wild type β3 subunit surface protein was fully glycosylated (i.e. migrated at 51 kDa), compared with 67.4 ± 5.9% of β3(G32R) and 56.7 ± 5.4% of β3(G32K) subunit proteins (Fig. 5, A1 and A2). In contrast, 42.0 ± 4.9% of β3(G32Q) subunit surface protein and only 2.8 ± 0.9% of β3(G32E) subunit surface protein were fully glycosylated.

FIGURE 5.

Presence of a basic residue at position 32 of β3 subunits increased β3 subunit glycosylation at Asn-33 and reduced γ2LHA subunit incorporation into surface a1β3γ2LHA GABAA receptors. A1, surface proteins were isolated from HEK293T cells expressing equimolar amounts of α1, γ2LHA, and different β3 subunits. In lane 1, the β3 subunit was not mutated (wt), and in lane 2, the β3 subunit contained the G32R mutation (GR). In lanes 3, 4, and 5, Gly-32 was mutated to lysine (GK), glutamine (GQ), or glutamate (GE), respectively. The upper panel presents staining for Na+/K+-ATPase as a loading control (LC), and the lower panel presents staining for β3 subunits. The β3 subunits migrated as three populations, with bands seen at ∼51, 47, and 43 kDa. A2, integrated intensity was calculated for all β3 subunit bands and normalized to the integrated band intensity of the Na+/K+-ATPase. The normalized integrated intensities for each β3 subunit band were summed, and the proportions of β3 protein migrating at 51 kDa (black), 47 kDa (gray), and 43 kDa (white) were calculated. B and C, surface levels of α1 (B) and γ2LHA (C) subunits in cells expressing α1, γ2LHA, and Gly-32 mutant β3 subunits were determined using flow cytometry. Upper panels present fluorescence intensity histograms in which the abscissa denotes fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units graphed on a logarithmic scale (FI), and the ordinate denotes percentage of maximum cell count (% of max). Fluorescence intensity histograms from mock-transfected cells (solid gray line) are overlaid with histograms from cells expressing α1, γ2LHA, and either β3(G32K) (dashed black line), β3(G32Q) (dotted black line), or β3(G32E) (solid black line) subunits. Lower panels present normalized fluorescence intensities for each condition. Mean fluorescence intensities from cells transfected with blank vector alone (mock) were subtracted from mean fluorescence intensities of cells transfected with α1, γ2LHA, and the indicated β3 subunits. All mock-subtracted fluorescence intensities were normalized to the mock-subtracted fluorescence intensity of the cells expressing β3 subunits. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared with wild type.

As in previous experiments, α1 subunit surface levels changed minimally when coexpressed with any β3 subunit (Fig. 5B). Surprisingly, however, α1 subunit surface levels did decrease significantly when coexpressed with β3(G32K) subunits (87.4 ± 3.4 of wild type; p < 0.05). Conversely, γ2LHA subunit surface levels were correlated with charge at β3 subunit residue 32. Specifically, γ2LHA subunit surface levels decreased significantly when the coexpressed β3 subunit had a positively charged residue (arginine or lysine) at position 32 (GK, 79.2 ± 3.3% of wild type, n = 12, p < 0.001), but γ2LHA subunit surface levels decreased only slightly when the coexpressed β3 subunit had an uncharged residue at the same position (GQ, 93.5 ± 3.4% of wild type, n = 12) and did not change when the coexpressed β3 subunit had a negatively charged residue (GE, 102.7 ± 4.0% of wild type, n = 11). Taken together, these data (Figs. 4 and 5) indicated that the positive charge introduced by the G32R mutation was responsible both for increasing Asn-33 glycosylation and for decreasing γ2LHA subunit incorporation; however, these two phenomena were not causally related to one another.

G32R Mutation Reduced Current Density Independent of Glycosylation

Up to now, we observed that the G32R mutation caused glycosylation-independent changes in subunit expression patterns that could reduce the function of αβγ GABAA receptors; however, those changes were not large enough to account for the reduction in current amplitude that was previously reported (15). This discrepancy suggested that expression of β3(G32R) subunits might also affect receptor gating. Furthermore, although subunit expression patterns depended upon charge at residue 32 rather than glycosylation at residue 33, any such changes in gating might still be glycosylation-dependent.

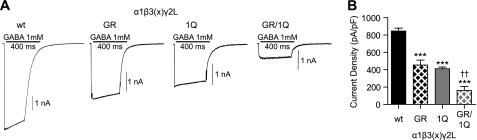

To determine how mutant β3(G32R) subunits affected GABAA receptor function, we used a rapid exchange system to apply 1 mm GABA for 400 ms to lifted HEK293T cells coexpressing α1, γ2L, and β3, β3(G32R), β3(N33Q), or β3(G32R/N33Q) subunits (Fig. 6A). Wild type receptors displayed a current density of 845.8 ± 33.93 pA/pF (n = 34), nearly 50% higher than current density of receptors containing mutant β3(G32R) subunits (454.3 ± 57.46 pA/pF, n = 32, p < 0.001 compared with wild type) (Fig. 6, A and B); this difference was consistent with previously reported data (15). When Asn-33 glycosylation was abolished by introducing the β3(N33Q) subunit mutation alone, current density also decreased (411.7 ± 19.61 pA/pF, n = 21, p < 0.001 compared with wild type). However, when the G32R mutation was introduced together with the N33Q mutation, current density decreased further (160.4 ± 46.99 pA/pF, n = 13, p < 0.001 compared with wild type and p < 0.01 compared with the β3(N33Q) subunit alone). These results suggested that although eliminating Asn-33 glycosylation by introducing the N33Q mutation itself reduced current density (because of either the absence of the glycan or the presence of the point mutation), the CAE-associated β3(G32R) subunit mutation also impaired receptor function independent of Asn-33 glycosylation.

FIGURE 6.

β3(G32R) mutation reduced current density from α1β3γ2L receptors even if the first glycosylation site was inactivated. A, currents were recorded from lifted whole HEK293T cells transfected with equimolar amounts of α1, γ2L, and either β3(WT), β3(G32R), β3(N33Q), or β3(G32R/N33Q) subunit cDNAs (wt, GR, 1Q, and GR/1Q, respectively). Cells were voltage-clamped at −20 mV and subjected to a 400-ms pulse of 1 mm GABA. Subunit identity and length of GABA application (black line) are indicated above the current traces. Scale bar = 1 nA. B, mean current densities (pA/pF) from cells expressing α1, γ2L, and either β3(WT), β3(G32R), β3(N33Q), or β3(G32R/N33Q) subunits were calculated. *** indicates p < 0.001 compared with WT; †† indicates p < 0.01, compared with NQ.

In summary, both β3(G32R) and β3(N33Q) point mutations significantly reduced current densities of α1β3γ2L receptors. However, the effects of these mutations were additive, indicating that the G32R point mutation reduced current density even when Asn-33 was not glycosylated. Taken together, these data suggest that the G32R mutation reduced current density by a mechanism that was independent of increasing Asn-33 glycosylation and furthermore that this region of the N-terminal α-helix could play a role in channel gating.

Presence of Charged Residue at Position 32 of the β3 Subunit Reduced Current Density of α1β3γ2L Receptors

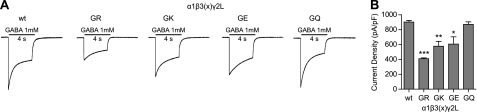

To this point, we demonstrated that the G32R mutation increased glycosylation at β3 subunit residue Asn-33, altered GABAA receptor assembly, and reduced current density. Contrary to previous hypotheses, the changes in subunit expression and receptor function were not due to increased β3 subunit glycosylation; the changes in subunit expression instead could be attributed to introduction of a positive charge at residue 32. Therefore, we investigated whether or not the charge of residue 32 was also responsible in part for the lower current densities observed in α1β3(G32R)γ2L receptors. We applied 1 mm GABA for 4 s to lifted HEK293T cells coexpressing α1, γ2L, and either β3, β3(G32R), β3(G32K), β3(G32E), or β3(G32Q) subunits and determined current densities (Fig. 7A). As expected, α1β3(G32R)γ2L receptor current densities were lower (p < 0.001) (GR, 409 ± 11 pA/pF, n = 8) than those of α1β3γ2L receptors (WT, 903 ± 22 pA/pF, n = 8) (Fig. 7B). When residue 32 was mutated to another basic residue (i.e. G32K), α1β3(G32K)γ2L receptor current densities were also significantly reduced (GK, 577 ± 66 pA/pF, n = 13, p < 0.01). Interestingly, current densities were also reduced in α1β3(G32E)γ2L receptors, i.e. when residue 32 was mutated to an acidic amino acid (GE, 606 ± 98 pA/pF, n = 10, p < 0.05). However, when residue 32 was mutated to a large but neutral amino acid (i.e. G32Q), receptor current density did not differ significantly from that of wild type receptors (GQ, 870 ± 35 pA/pF, n = 10). Thus, receptor function was altered due to introduction of a charged residue at this position. It is possible that the charged residues can form new salt bridges that altered channel function (this hypothesis is further addressed below).

FIGURE 7.

Introduction of a charged residue at position 32 reduced current amplitudes in α1β3γ2L GABAA receptors. A, currents were recorded from lifted whole HEK293T cells transfected with equimolar amounts of α1, γ2L, and either β3, β3(G32R), β3(G32K), β3(G32E), or β3(G32Q) subunit cDNAs (wt, GR, GK, GE, and GQ, respectively). Cells were voltage-clamped at −20 mV and subjected to a 4-s pulse of 1 mm GABA. Subunit identity and length of GABA application (black line) are indicated above the current traces. Scale bar = 1 nA. B, mean current density (pA/pF) from cells expressing α1, γ2L, and either β3, β3(G32R), β3(G32K), β3(G32E), or β3(G32Q) subunits were calculated. All data are presented as mean ± S.E., and significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post test. *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively, compared with wild type.

α1β3(G32R)γ2L Receptors Were More Likely to Enter Short Open States and Had Reduced Mean Open Times

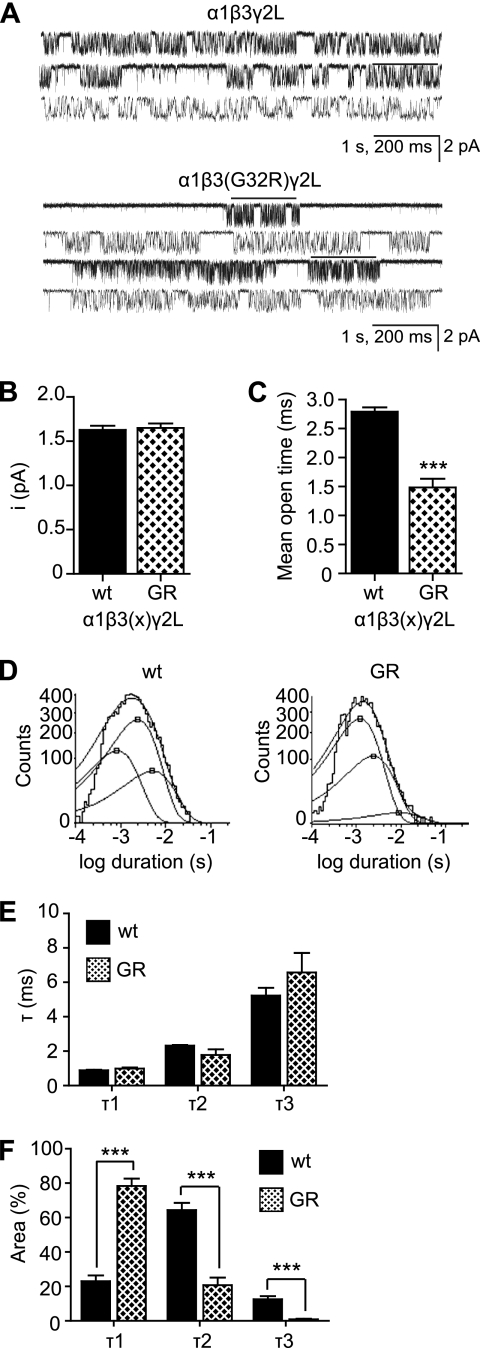

The α1β3(G32R)γ2LHA receptors displayed many macroscopic kinetic changes (slightly slower activation, faster desensitization, and faster deactivation) that were consistent with reduced charge transfer; however, most of these changes were not significant and could not explain the nearly 50% reduction of current density in mutant compared with wild type receptors. Consequently, we employed cell-attached single channel recording to examine the microscopic kinetic properties of α1β3γ2L receptors containing β3 or β3(G32R) subunits (Fig. 8A). Wild type and mutant receptors had identical single channel amplitudes (Fig. 8B), but mutant receptors had significantly reduced mean open times (Fig. 8C). The reduction was not due to alterations of open time constants themselves, because the open duration histograms of wild type and mutant receptors (Fig. 8D) both were fitted best by three time constants whose mean durations did not change (Fig. 8E). However, the relative contributions of the time constants did change (Fig. 8F); specifically, the relative proportion of the shortest open state was significantly increased in mutant receptors (α1β3γ2L receptors τ1% = 23.1 ± 3.3%; α1β3(G32R)γ2L receptors τ1% = 78.4 ± 4.2%; n = 4, p < 0.001). Therefore, the G32R mutation reduced GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition both by introducing a positive charge that discouraged formation of high functioning α1β3γ2L receptors in favor of low functioning α1β3 receptors and β3 homopentameric receptors and by inducing those α1β3γ2L receptors to enter shorter open states, thereby reducing mean single channel open time.

FIGURE 8.

G32R mutation reduced mean single channel open time of α1β3γ2L GABAA receptors by promoting occupancy of shorter lived open states. A, single channel currents were recorded from HEK293T cells expressing α1, γ2L, and either β3 (upper panel) or β3(G32R) (lower panel) subunits. Recording was conducted in the cell-attached configuration, with cells voltage-clamped at +80 mV and 1 mm GABA present in the recording electrode. B, single channel conductance (pA) was calculated for α1β3γ2L and α1β3(G32R)γ2L GABAA receptors. C, mean open time (ms) was calculated for α1β3γ2L and α1β3(G32R)γ2L GABAA receptors. D, frequency histograms of channel open durations were best fitted with three exponential functions. The left panel presents histograms for α1β3γ2L receptors, and the right panel presents histograms for α1β3(G32R)γ2L receptors. E, means of the three open durations (ms) were calculated. F, relative contribution (%) of each open state was calculated. All data are expressed as mean ± S.E., and significance was calculated using two-tailed Student's t test. *** indicates p < 0.001 compared with WT.

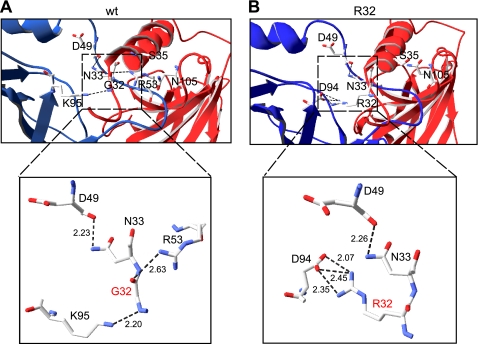

β3(G32R) Mutation Was Predicted to Alter Salt Bridges and Conformation at β3-γ2 and β3-β3 Subunit Interfaces

To gain insight into the mechanism by which the β3(G32R) mutation affected receptor assembly and channel gating, we performed homology modeling of wild type and mutant receptors using the nAChR α1 subunit extracellular domain structure (Protein Data Bank code 2qc1) (29) as a template (Fig. 10). In α1β3γ2L receptor isoforms, the major structural changes induced by the β3(G32R) mutation occurred at the interface between the principal (+) side of the γ2L subunit and the complementary (−) side of the β3 subunit (γ2-β3 interface). In both α1β3γ2L (Fig. 9A) and α1β3(G32R)γ2L (Fig. 9B) receptors, all subunits were predicted to begin with a random coil leading into an α-helix. However, the G32R mutation induced a conformational change in the β3 subunit α-helix, causing the random coil to project in a slightly different direction. Moreover, the side chain of Arg-32 extended across the γ2-β3 subunit interface, forming a salt bridge with γ2 subunit residue Asp-123, which lies in a motif previously established to be necessary for γ2-β3 subunit interaction (35).

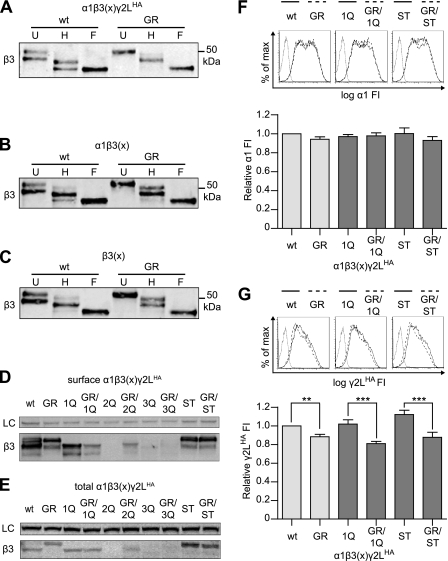

FIGURE 10.

β3(G32R) mutation changed salt bridge formation at the β3-β3 interface of homopentameric receptors. Three-dimensional models of β3 homopentamers were constructed as described in Fig. 10. A, upper panel, illustrates a portion of the interface between two wild type β3 subunits. Although the two subunits are identical, one is presented in red and one in blue for clarity. The lower panel presents a magnification of the area boxed in the upper panel. B, upper panel illustrates a portion of the interface between two β3(G32R) subunits, and the lower panel presents a magnification of the area boxed in the upper panel.

FIGURE 9.

β3(Gly-32) mutations changed conformation and salt bridge formation at the γ2-β3 interface of heteropentameric α1β3γ2L receptors. Three-dimensional models of α1, β3, and γ2 subunit extracellular domains were created (see under “Experimental Procedures”) and threaded onto the L. stagnalis acetylcholine-binding protein structure in the order γ2-β3-α1-β3-α1 to model ternary heteropentameric α1β3γ2L receptors. Point mutations were introduced into β3 subunit structures and the resulting energy-minimized models were examined for structural changes. A, portion of the interface between the γ2 subunit (yellow) and the wild type β3 subunit (blue) is presented. The perspective is from outside the receptor, such that the synaptic cleft would be located at the top of the figure. Residues discussed in the text, including the mutated Gly-32, the first glycosylation sequon residues Asn-33 and Ser-35, and the second glycosylation site Asn-105, are labeled, and predicted salt bridges are indicated by dotted lines. Adjacent numbers indicate the distance in angstroms between the two atoms forming the salt bridge. Two γ2 subunit residues are also identified: Arg-125, which is predicted to form a salt bridge with β3 (Asn-33); and Arg-82, which was mutated to Q in a family with GEFS+. Side chains are colored in the CPK scheme; carbon atoms are gray, oxygen atoms are red, and nitrogen atoms are blue. B–D, views of the γ2-β3 interface in α1β3(G32R)γ2L (B), α1β3(G32K)γ2L (C), and α1β3(G32E)γ2L (D) receptors are presented as in A. Salt bridges longer than 3.5 Å are indicated by gray dotted lines, and salt bridges shorter than 3.5 Å are indicated by black dotted lines.

Because both α1β3(G32K)γ2L and α1β3(G32E)γ2L receptors also displayed reduced current densities, we performed homology modeling of these isoforms as well. These mutations also induced structural changes primarily at the γ2-β3 subunit interface. Interestingly, the side chain of the β3 subunit residue Lys-32 angled toward the cell membrane and formed a salt bridge with the γ2 subunit residue Glu-217, which participates in a salt bridge network disrupted by the epilepsy-associated γ2(R82Q) mutation (Fig. 9C) (36). The side chain of the β3 subunit residue Glu-32, conversely, extended toward the γ2 subunit but did not come within 4 Å of any γ2 subunit atoms (Fig. 9D).

We demonstrated that β3(G32R) subunits were expressed on the cell surface at much higher levels than β3 subunits, suggesting that mutant subunits might assemble into homopentamers. Consequently, we also created homology models of β3 and β3(G32R) homopentameric receptors. Unsurprisingly, structural changes occurred at subunit interfaces. Strong salt bridges existed at the interface of wild type β3 subunits (Fig. 10A), but when Arg-32 was introduced (Fig. 10B), its side chain formed three new salt bridges with Asp-94 of the adjacent β3(G32R) subunit. In summary, homology modeling provided a potential explanation for the changes in subunit surface expression associated with the β3 subunit G32R mutation. All structural changes occurred at subunit interfaces, suggesting that the point mutation could perturb subunit oligomerization.

DISCUSSION

N-terminal α-Helix, New Roles in Receptor Assembly and Gating?

A large body of work exists documenting the GABAA receptor subunit domains that are responsible for receptor assembly and trafficking, GABA binding, and coupling of agonist binding to channel gating (37). However, the distal N-terminal domain, which includes a random coil followed by an α-helix, has not been demonstrated to be important for these processes. In fact, the helix was entirely absent in recently discovered prokaryotic nAChR homologs (38, 39). Helical integrity was shown to be necessary for proper biogenesis of nAChR α7 subunits, but most residues could be mutated without affecting subunit expression (40). In our experiments, multiple point mutations of Gly-32 and Asn-33 residues in the distal α-helix of β3 subunits caused changes in assembly as well as gating that were not attributable fully to the glycosylation changes induced by the mutations. Our results suggest that unexpectedly the N-terminal α1-helix may be important for assembly and function of GABAA receptors containing β3 subunits.

β3 Subunit G32R Mutation and Receptor Heterogeneity

Our data suggested that the G32R mutation promoted formation of binary α1β3 receptors and β3 homopentamers and decreased formation of ternary α1β3γ2L receptors. Wild type β3 subunits are known to assemble more promiscuously than most other GABAA receptor subunits in heterologous systems; β3 subunits reached the cell surface when expressed alone, and both β3 and γ2L subunits were detected on the cell surface when coexpressed together without an α subunit (14). We obtained similar results when β3 subunits were coexpressed with β, δ, ϵ, or θ subunits (data not shown). In contrast, β2 subunits are retained intracellularly and degraded in the absence of coexpressed α subunits even though β2 and β3 subunits have very similar sequences. In previous studies, four amino acid residues (Gly-171, Lys-173, Glu-179, and Arg-180) conferred the ability to form β3 subunit homopentamers (14). According to our model, these residues are also predicted to lie on the (−)-face of β3 subunits, but are much closer to the cell membrane than the Gly-32 residue. Thus, we may have uncovered a previously unknown role for the N-terminal α-helix in regulating β3 homopentamer assembly.

β3 Subunit Glycosylation, Patterns, and Their Dependence on Receptor Subunit Composition

Although we have shown that hyperglycosylation ultimately was not responsible for the effects of the β3(G32R) mutation on receptor assembly and function, our studies elucidate the characteristics and importance of β3 subunit N-glycosylation. We demonstrated that all three N-glycosylation sites on wild type β3 subunits could be glycosylated in HEK293T cells, although many β3 subunits were not glycosylated at Asn-33. Importantly, other investigators have observed similar β3 subunit glycosylation patterns in mouse cortical neurons.3 Interestingly, we also showed that β3 subunits retain some unprocessed high mannose glycans despite being assembled into receptors and trafficked to the cell surface. This occurred in all tested receptor isoforms (i.e. β3, α1β3, and α1β3γ2L); however, the proportion of β3 subunits containing endo H-sensitive glycans was correlated with the number of different subunits expressed. We recently observed a similar phenomenon in β2 subunits. In heterologous systems, all β2 subunit bands were endo H-resistant when only α1 and β2 subunits were coexpressed, but an endo H-sensitive population appeared if γ2 subunits were added. Furthermore, β2 subunits from heterozygous γ2 subunit knock-out mice, which may form α1β2 receptors due to γ2 subunit deficiency, had a larger endo H-resistant population than β2 subunits from wild type mice.4 Taken together, these findings suggest that incorporation of non-β subunits might alter β subunits such that their glycans become accessible for modification in the Golgi apparatus. It will be interesting to determine whether glycan structure contributes to the characteristic current properties of binary and ternary receptors.

Although the G32R mutation appeared to promote increased assembly of binary α1β3 and homopentameric β3 receptors, and those isoforms promoted glycan maturation, the G32R mutation also affected glycan processing independent of receptor stoichiometry. All wild type receptors (i.e. β3, α1β3, and α1β3γ2L) contained at least a small population of β3 subunits that were fully endo H-sensitive. However, that population virtually disappeared in the corresponding mutant receptor isoforms. It may be worthwhile to investigate whether microheterogeneity (i.e. sugar composition) as well as macroheterogeneity (i.e. sequon occupancy) of N-glycans can affect receptor function.

Altered Salt Bridge Formation and Receptor Conformation May Be Responsible for Changes in Assembly, Glycosylation, and Gating, Leading to Reduced GABAA Receptor-mediated Inhibition

Because GABAA receptors have not been crystallized, homology models are limited to nAChR (29, 41) and AChBP (30, 42) templates, many of which have poor resolution in their N-terminal domains. Therefore, although homology models of GABAA receptors are necessarily speculative, they nonetheless provide valuable insight regarding potential interactions. In our models, mutating the Gly-32 residue to Arg-32 induced formation of new salt bridges at the γ2-β3 and β3-β3 interfaces in ternary and homopentameric receptors, respectively. The β3-β3 salt bridges were particularly strong and would likely increase the affinity of homodimer formation. This, in turn, could promote formation of isoforms containing a β3-β3 interface. Such interfaces are not predicted to exist in ternary receptors, which are thought to have a γ-β-α-β-α orientation (anticlockwise as viewed from the synaptic cleft) (12, 13). However, in binary receptors, the γ2 subunit presumably is replaced by either an α1 or a β3 subunit; the latter would introduce a β3-β3 interface. It is possible that the salt bridges introduced by the G32R mutation promote β3(G32R) subunit homodimerization, which in turn could “seed” the formation of (α1)2(β3)3 and β3 receptor isoforms, thereby increasing β3 subunit surface expression. It is somewhat less clear how salt bridge formation between Arg-32 and γ2(Asp-123) could discourage incorporation of γ2 subunits; however, it is important to note that salt bridges can be destabilizing (43) and that γ2 subunit (122–129) integrity was essential for γ2-β3 subunit interaction (35). It is also worth mentioning that the epilepsy-associated mutation γ2(R82Q), which has been shown to disrupt receptor assembly (36, 44), is located in the γ2 subunit loop closest to the N-terminal domain of the β3 subunit α-helix. Indeed, point mutations throughout this loop impaired γ2 subunit incorporation. Thus, it is possible that any structural changes in this area, whether on γ2 or β3 subunits, could disturb an important assembly domain and result in preferential expression of low efficacy binary αβ3 receptors and homopentameric β3 receptors instead of high efficacy ternary αβ3γ2 receptors, thereby causing disinhibition.

How Might the β3(G32R) Mutation Contribute to Epileptogenesis?

The electroencephalographic signature of an absence seizure involves generalized, synchronous spike-wave activity, reflecting oscillations in thalamocortical circuits. The location of the seizure discharge origin within these circuits remains a subject of debate (45), making it difficult to predict how changes in the function of a particular ion channel could initiate seizures. However, it is known that both thalamic reticular nucleus and cortex (particularly somatosensory cortex) participate in synchronized activity. Importantly, the β3 subunit subtype predominates in the reticular nucleus throughout life and in the cortex during development (31, 46, 47).

It was recently demonstrated that tonic GABAergic current is paradoxically increased in thalamocortical neurons from two rat models of absence epilepsy (48), although we discovered many changes wrought by the G32R mutation that decreased mutant receptor function. This could indicate that the G32R mutation might primarily promote hyperexcitability through cortical and/or postsynaptic (i.e. phasic current-mediating) GABAA receptors. If so, this could suggest a reason for this mutation being associated with childhood absence epilepsy, because cortical β3 subunit expression declines throughout childhood. Thus, it is possible that deficits in GABAA receptors containing β3 subunits could affect children more significantly because a larger proportion of their cortical receptors contain β3 subunits and that associated epilepsy syndromes might remit as β2 subunits displace β3 subunits in adulthood.

M. J. Gallagher, private communication.

W. Y. Lo, A. H. Lagrange, C. C. Hernandez, K. N. Gurba, and R. L. Macdonald, in preparation.

- CAE

- childhood absence epilepsy

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- FI

- fluorescence intensity

- GABAA

- γ-aminobutyric acid, type A

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- pF

- picofarad

- endo H

- endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase H

- nAChR

- nicotinic acetylcholine receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Crunelli V., Leresche N. (2002) Childhood absence epilepsy. Genes, channels, neurons, and networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 371–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen Y., Lu J., Pan H., Zhang Y., Wu H., Xu K., Liu X., Jiang Y., Bao X., Yao Z., Ding K., Lo W. H., Qiang B., Chan P., Shen Y., Wu X. (2003) Association between genetic variation of CACNA1H and childhood absence epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 54, 239–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lü J. J., Zhang Y. H., Chen Y. C., Pan H., Wang J. L., Zhang L., Wu H. S., Xu K. M., Liu X. Y., Tao L. D., Shen Y., Wu X. R. (2005) T-type calcium channel gene CACNA1H is a susceptibility gene to childhood absence epilepsy. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 43, 133–136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liang J., Zhang Y., Chen Y., Wang J., Pan H., Wu H., Xu K., Liu X., Jiang Y., Shen Y., Wu X. (2007) Common polymorphisms in the CACNA1H gene associated with childhood absence epilepsy in Chinese Han population. Ann. Hum. Genet. 71, 325–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Everett K. V., Chioza B., Aicardi J., Aschauer H., Brouwer O., Callenbach P., Covanis A., Dulac O., Eeg-Olofsson O., Feucht M., Friis M., Goutieres F., Guerrini R., Heils A., Kjeldsen M., Lehesjoki A. E., Makoff A., Nabbout R., Olsson I., Sander T., Sirén A., McKeigue P., Robinson R., Taske N., Rees M., Gardiner M. (2007) Linkage and association analysis of CACNG3 in childhood absence epilepsy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 15, 463–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Everett K., Chioza B., Aicardi J., Aschauer H., Brouwer O., Callenbach P., Covanis A., Dooley J., Dulac O., Durner M., Eeg-Olofsson O., Feucht M., Friis M., Guerrini R., Heils A., Kjeldsen M., Nabbout R., Sander T., Wirrell E., McKeigue P., Robinson R., Taske N., Gardiner M. (2007) Linkage and mutational analysis of CLCN2 in childhood absence epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 75, 145–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hernandez C. C., Gurba K. N., Hu N., Macdonald R. L. (2011) The GABRA6 mutation, R46W, associated with childhood absence epilepsy, alters 6β22 and 6β2 GABA(A) receptor channel gating and expression. J. Physiol. 589, 5857–5878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kang J. Q., Shen W., Macdonald R. L. (2009) The GABRG2 mutation, Q351X, associated with generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus, has both loss of function and dominant-negative suppression. J. Neurosci. 29, 2845–2856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kananura C., Haug K., Sander T., Runge U., Gu W., Hallmann K., Rebstock J., Heils A., Steinlein O. K. (2002) A splice-site mutation in GABRG2 associated with childhood absence epilepsy and febrile convulsions. Arch. Neurol. 59, 1137–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Olsen R. W., Sieghart W. (2008) International Union of Pharmacology. LXX. Subtypes of γ-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors. Classification on the basis of subunit composition, pharmacology, and function. Update. Pharmacol. Rev. 60, 243–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tretter V., Ehya N., Fuchs K., Sieghart W. (1997) Stoichiometry and assembly of a recombinant GABAA receptor subtype. J. Neurosci. 17, 2728–2737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baumann S. W., Baur R., Sigel E. (2001) Subunit arrangement of γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36275–36280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baumann S. W., Baur R., Sigel E. (2002) Forced subunit assembly in α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors. Insight into the absolute arrangement. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46020–46025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taylor P. M., Thomas P., Gorrie G. H., Connolly C. N., Smart T. G., Moss S. J. (1999) Identification of amino acid residues within GABAA receptor β subunits that mediate both homomeric and heteromeric receptor expression. J. Neurosci. 19, 6360–6371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tanaka M., Olsen R. W., Medina M. T., Schwartz E., Alonso M. E., Duron R. M., Castro-Ortega R., Martinez-Juarez I. E., Pascual-Castroviejo I., Machado-Salas J., Silva R., Bailey J. N., Bai D., Ochoa A., Jara-Prado A., Pineda G., Macdonald R. L., Delgado-Escueta A. V. (2008) Hyperglycosylation and reduced GABA currents of mutated GABRB3 polypeptide in remitting childhood absence epilepsy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82, 1249–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Helenius A., Aebi M. (2004) Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 1019–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bause E. (1983) Structural requirements of N-glycosylation of proteins. Studies with proline peptides as conformational probes. Biochem. J. 209, 331–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Imperiali B., Shannon K. L. (1991) Differences between Asn-Xaa-Thr-containing peptides. A comparison of solution conformation and substrate behavior with oligosaccharyltransferase. Biochemistry 30, 4374–4380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaplan H. A., Welply J. K., Lennarz W. J. (1987) Oligosaccharyltransferase. The central enzyme in the pathway of glycoprotein assembly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 906, 161–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Molinari M. (2007) N-Glycan structure dictates extension of protein folding or onset of disposal. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 313–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glozman R., Okiyoneda T., Mulvihill C. M., Rini J. M., Barriere H., Lukacs G. L. (2009) N-Glycans are direct determinants of CFTR folding and stability in secretory and endocytic membrane traffic. J. Cell Biol. 184, 847–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Antenos M., Stemler M., Boime I., Woodruff T. K. (2007) N-Linked oligosaccharides direct the differential assembly and secretion of inhibin α- and βA-subunit dimers. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 1670–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Buller A. L., Hastings G. A., Kirkness E. F., Fraser C. M. (1994) Site-directed mutagenesis of N-linked glycosylation sites on the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor α1 subunit. Mol. Pharmacol. 46, 858–865 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jaeken J. (2010) Congenital disorders of glycosylation. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1214, 190–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lo W. Y., Lagrange A. H., Hernandez C. C., Harrison R., Dell A., Haslam S. M., Sheehan J. H., Macdonald R. L. (2010) Glycosylation of β2 subunits regulates GABAA receptor biogenesis and channel gating. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 31348–31361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fisher J. L., Macdonald R. L. (1997) Single channel properties of recombinant GABAA receptors containing γ2 or δ subtypes expressed with α and β3 subtypes in mouse L929 cells. J. Physiol. 505, Pt. 2, 283–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Twyman R. E., Rogers C. J., Macdonald R. L. (1990) Intraburst kinetic properties of the GABAA receptor main conductance state of mouse spinal cord neurones in culture. J. Physiol. 423, 193–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schwede T., Kopp J., Guex N., Peitsch M. C. (2003) SWISS-MODEL. An automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3381–3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dellisanti C. D., Yao Y., Stroud J. C., Wang Z. Z., Chen L. (2007) Crystal structure of the extracellular domain of nAChR α1 bound to α-bungarotoxin at 1.94 Å resolution. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 953–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brejc K., van Dijk W. J., Klaassen R. V., Schuurmans M., van Der Oost J., Smit A. B., Sixma T. K. (2001) Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature 411, 269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sieghart W., Sperk G. (2002) Subunit composition, distribution, and function of GABAA receptor subtypes. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2, 795–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bañó-Polo M., Baldin F., Tamborero S., Marti-Renom M. A., Mingarro I. (2011) N-Glycosylation efficiency is determined by the distance to the C terminus and the amino acid preceding an Asn-Ser-Thr sequon. Protein Sci. 20, 179–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sutachan J. J., Watanabe I., Zhu J., Gottschalk A., Recio-Pinto E., Thornhill W. B. (2005) Effects of Kv1.1 channel glycosylation on C-type inactivation and simulated action potentials. Brain Res. 1058, 30–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kamei N., Fukui R., Suzuki Y., Kajihara Y., Kinoshita M., Kakehi K., Hojo H., Tezuka K., Tsuji T. (2010) Definitive evidence that a single N-glycan among three glycans on inducible costimulator is required for proper protein trafficking and ligand binding. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 557–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klausberger T., Fuchs K., Mayer B., Ehya N., Sieghart W. (2000) GABAA receptor assembly. Identification and structure of γ2 sequences forming the intersubunit contacts with α1 and β3 subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8921–8928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Frugier G., Coussen F., Giraud M. F., Odessa M. F., Emerit M. B., Boué-Grabot E., Garret M. (2007) A γ2(R43Q) mutation, linked to epilepsy in humans, alters GABAA receptor assembly and modifies subunit composition on the cell surface. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3819–3828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kash T. L., Trudell J. R., Harrison N. L. (2004) Structural elements involved in activation of the γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32, 540–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bocquet N., Nury H., Baaden M., Le Poupon C., Changeux J. P., Delarue M., Corringer P. J. (2009) X-ray structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel in an apparently open conformation. Nature 457, 111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hilf R. J., Dutzler R. (2008) X-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature 452, 375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Castillo M., Mulet J., Aldea M., Gerber S., Sala S., Sala F., Criado M. (2009) Role of the N-terminal α-helix in biogenesis of α7 nicotinic receptors. J. Neurochem. 108, 1399–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Unwin N. (2005) Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 346, 967–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smit A. B., Brejc K., Syed N., Sixma T. K. (2003) Structure and function of AChBP, homologue of the ligand-binding domain of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 998, 81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hendsch Z. S., Tidor B. (1994) Do salt bridges stabilize proteins? A continuum electrostatic analysis. Protein Sci. 3, 211–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hales T. G., Tang H., Bollan K. A., Johnson S. J., King D. P., McDonald N. A., Cheng A., Connolly C. N. (2005) The epilepsy mutation, γ2(R43Q) disrupts a highly conserved intersubunit contact site, perturbing the biogenesis of GABAA receptors. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 29, 120–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Meeren H., van Luijtelaar G., Lopes da Silva F., Coenen A. (2005) Evolving concepts on the pathophysiology of absence seizures. The cortical focus theory. Arch. Neurol. 62, 371–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]