Background: Homocysteinylated heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein E1 (hnRNP-E1) orchestrates a posttranscriptional RNA operon during folate deficiency.

Results: Folate deficiency induced homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 to bind HPV16 RNA, reduced both viral capsid proteins, promoted HPV16 DNA integration into genomic DNA, and rapidly transformed HPV16-organotypic rafts implanted in immunodeficient mice to cancer.

Conclusion: A likely molecular link between folate nutrition and HPV16 is established.

Significance: Folate/vitamin-B12 deficiency can promote HPV16 DNA integration and carcinogenesis.

Keywords: Cancer Prevention, Folate, Homocysteine, Papillomavirus, RNA-binding Protein, RNA-Protein Interaction, Viral Protein, Posttranscriptional RNA Operon, hnRNP-E1/PCBP1, Viral Integration

Abstract

Although HPV16 transforms infected epithelial tissues to cancer in the presence of several co-factors, there is insufficient molecular evidence that poor nutrition has any such role. Because physiological folate deficiency led to the intracellular homocysteinylation of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein E1 (hnRNP-E1) and activated a nutrition-sensitive (homocysteine-responsive) posttranscriptional RNA operon that included interaction with HPV16 L2 mRNA, we investigated the functional consequences of folate deficiency on HPV16 in immortalized HPV16-harboring human (BC-1-Ep/SL) keratinocytes and HPV16-organotypic rafts. Although homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 interacted with HPV16 L2 mRNA cis-element, it also specifically bound another HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(U)-rich cis-element in the early polyadenylation element (upstream of L2̂L1 genes) with greater affinity. Together, these interactions led to a profound reduction of both L1 and L2 mRNA and proteins without effects on HPV16 E6 and E7 in vitro, and in cultured keratinocyte monolayers and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts developed in physiological low folate medium. In addition, HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts contained fewer HPV16 viral particles, a similar HPV16 DNA viral load, and a much greater extent of integration of HPV16 DNA into genomic DNA when compared with HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts. Subcutaneous implantation of 18-day old HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts into folate-replete immunodeficient mice transformed this benign keratinocyte-derived raft tissue into an aggressive HPV16-induced cancer within 12 weeks. Collectively, these studies establish a likely molecular linkage between poor folate nutrition and HPV16 and predict that nutritional folate and/or vitamin-B12 deficiency, which are both common worldwide, will alter the natural history of HPV16 infections and also warrant serious consideration as reversible co-factors in oncogenic transformation of HPV16-infected tissues to cancer.

Introduction

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs),3 which infect suprabasal keratinocytes and persist in differentiating epithelial cells of cutaneous, mucosal, and genital tissues, are causally implicated in several cancers as well as venereal and other skin warts (1–4). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/hpv/cancer.html) estimates that HPV causes almost all cervical cancer and links HPV to about 50% of vulvar cancers, 65% of vaginal cancers, 35% of penile cancers, 95% of anal cancer, and up to 60% of oropharyngeal cancers. The prevalence of latent HPV infection is ∼40% worldwide, and whereas 5–10% of infected women will develop squamous intraepithelial lesions, less than 1% will develop cervical cancer (5). Among the various oncogenic HPV types, HPV16 is the commonest agent that is responsible for an estimated one-half of all HPV-associated cancers worldwide. There are established co-factors that accelerate HPV-induced transformation of tissues to cancer. Among these co-factors (early age at first intercourse, multiple partners, smoking, oral contraceptives, and reduced immunity with HIV/AIDS), the role of poor folate nutrition has been suspected for 3 decades, but no molecular linkage with HPV has been identified. Nevertheless, because of limited non-surgical options for eradication of established HPV infection in cervical and other epithelial tissues, identification of any reversible cofactor (such as a nutritional deficiency) that can modulate the expression of HPV is eminently worthy of study.

Following epithelial cell division, HPV-infected daughter cells migrate superficially from the basal region and begin differentiation. Upon terminal differentiation in the granulosa and cornified layers of infected epithelia, vegetative viral DNA replication or amplification is induced followed by activation of viral late gene expression, encoding HPV viral capsid proteins L1 and L2 at a 20:1 ratio, respectively, with subsequent assembly and encapsidation of HPV DNA into infectious HPV virions (3, 6). Although a comprehensive understanding of the precise molecular basis for the expression of L2 and L1 in differentiating cells is still incomplete, it has been known for over a decade that cellular hnRNP-E1 can interact with the 3′-coding region of HPV16 L2 mRNA (7). Furthermore, by engineering HeLa cells to express L2, Collier et al. (7) showed that transfection of hnRNP-E1 reduces expression of L2. However, it not clear if this interaction involves direct reduction of L2 mRNA translation and/or reduced stability of the mRNA-protein complex or another mechanism and if this occurs in cultured keratinocytes that can actively express all HPV genes. Moreover, the pathophysiologic context wherein hnRNP-E1 interacts with HPV16 RNA has also remained obscure.

Earlier we had determined that up-regulation of folate receptors in cervical cancer cells during folate deficiency involves the binding of hnRNP-E1 to an 18-base cis-element in the 5′-untranslated region of folate receptor-α mRNA, which triggers an increase in folate receptor biosynthesis at the translational level (8, 9). Because this RNA-protein interaction was stimulated by homocysteine, which accumulates intracellularly during folate deficiency, this work established a link between perturbed folate metabolism and coordinated translational regulation of folate receptors (10). Using purified components, we recently determined that the molecular mechanism of this posttranscriptional up-regulation of folate receptors during folate deficiency involves a concentration-dependent homocysteinylation of various cysteine residues within the (mRNA-binding) K-homology domains of hnRNP-E1, which probably leads to the sequential disruption of critical cysteine-S-S-cysteine bonds by the formation of multiple homocysteine-S-S-cysteine mixed disulfide bonds in hnRNP-E1 (11). This leads to a gradual unmasking of an underlying RNA-binding pocket in homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 that progressively increases its affinity for folate receptor-α mRNA cis-element preparatory to folate receptor up-regulation. These data incriminated hnRNP-E1 as a physiologically relevant and sensitive candidate sensor of folate deficiency within cells (11), and because diverse mRNAs (including rabbit 15-lipoxygenase, murine tyrosine hydroxylase and intermediate neurofilament-middle molecular mass, and HPV16 L2 mRNA) also interacted with this RNA-binding domain (7, 8), we proposed that homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 was well positioned to orchestrate a nutrition-sensitive (homocysteine-responsive) posttranscriptional RNA operon in folate-deficient cells.

Because this research had uncovered unexpected connections between folate deficiency, homocysteine, hnRNP-E1, and HPV16 (7, 10, 11), we determined the functional physiological consequence of folate deficiency to HPV16 viral capsid protein expression using a model of HPV16-harboring human keratinocytes ((HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL cells) that expressed the full complement of HPV16 RNA when propagated as monolayers. Further extension of these studies to HPV16-organotypic rafts and additional animal studies suggests that folate deficiency is a likely (reversible) co-factor in HPV16-induced malignancies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Adaptation of (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL Keratinocytes to Growth in High Folate and Low Folate F Medium in Absence of Feeder Layers

BC-1-Ep/SL cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). BC-1-Ep/SL cells that were stably transfected with HPV16 (12) (referred to as (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL cells) were a generous gift from Professor Paul Lambert (University of Wisconsin). These cells grow in the presence of NIH 3T3 cell feeder layers in F-medium that was composed of 1 part of DMEM and 3 parts of Ham's F-12 medium (HyQ DME/high glucose, and HyQ Ham's F-12, respectively) (HyClone, Logan, UT), and supplemented with the following components: 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), adenine (24 μg/ml), cholera toxin (8.4 ng/ml), epidermal growth factor (10 ng/ml), hydrocortisone (2.4 μg/ml), and insulin (5 μg/ml). The cells were first adapted to stable growth in the absence of feeder layers in high folate F-medium (F-HF) that contained a final folate concentration of 4.5 μm pteroylglutamic acid plus 6.8 nm 5-methyltetrahydrofolate; these cells are referred to hereafter as (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells. Another aliquot of these cells were adapted stepwise over several weeks to stable growth in low folate F-medium (F-LF) which was similar in all other respects to supplemented F-HF except that it contained a final physiological low folate concentration of 6.8 nm 5-methyltetrahydrofolate that was contributed from 5% FBS; these cells are referred to hereafter as (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells. There was no significant difference in doubling time between (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL cells stably propagated in either F-HF (29.5 h) or F-LF (30 h).

Effect of Homocysteine on Interaction of HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(U)-rich cis-Element with Purified Recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1

The HPV16 57-nucleotide cis-element (13) in the early polyadenylation element of the HPV16 genome was first cloned into the pSPT19 vector with EcoRI on the 5′-end and HindIII on the 3′-end. The two oligonucleotides (5′-AAT TCT TTT TTC TTT TTT ATT TTC ATA TAT AAT TTT TTT TTT TGT TTG TTT GTT TGT TTT TTG-3′ and 5′-AGC TTA AAA AAC AAA CAA ACA AAC AAA AAA AAA AAT TAT ATA TGA AAA TAA AAA AGA AAA AAA-3′) were annealed and subcloned into the pSPT19 vector that was linearized with EcoRI and HindIII. The new plasmid pYS57 was verified by restriction enzyme digestion. To prepare 32P-labeled HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(U)-rich cis-element, pYS57 was linearized by HindIII, and then [α-32P]UTP was included in the transcription reaction using the SP6/T7 Transcription Kit (Roche Applied Science), followed by purifying RNA transcripts with NucTrap Probe Purification Columns and a Push Column Beta Shield Device (Stratagene). RNA-protein binding assays were carried out using 1 μg of dialyzed, purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 (11) and 1 × 105 cpm of [32P]HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(U)-rich cis-element in binding buffer containing increasing concentrations of l-homocysteine (0–100 μm) in a final volume of 15 μl. After incubation at 4 °C for 30 min, 1 μl of heparin solution (100 mg/ml) was added, and incubation continued for 15 min. Electrophoresis of RNA-protein complexes was carried out using 6% native PAGE (60:1), and dried gels were autoradiographed overnight.

Comparison of Dissociation Constant (KD) of RNA-Protein Interactions

[35S]HPV16 L2 RNA or [35S]HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element RNA fragments were prepared using the SP6 transcription kit (Roche Applied Science) in the presence of 250 μCi of [α-35S]CTP or [α-35S]TTP and 5 μg of pSPT3′L2/EcoRI or 5 μg of pYS57/HindIII. After transcription, template DNAs were digested with DNase I (RNase-free), and RNA transcripts were purified with Quick-Spin G-25 columns. Binding of the [35S]HPV16 L2 RNA or [35S]HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element to purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 at 25 μm l-homocysteine was then tested. Each level was measured in triplicate. Briefly, except for the addition of l-homocysteine, all KD experiments were carried out in the absence of added reducing agents. The binding assays between 0.1 μg of purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 and [35S]HPV16 L2 RNA or [35S]HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element (0.02, 0.05, 0.13, 0.32, 0.8, 2, 5, and 12.5 nm) were carried out in a final volume of 500 μl of binding buffer with 25 μm l-homocysteine at 4 °C for 0.5 h. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) (0.1 μg) was used as a control in place of hnRNP-E1 for background determination. The mixture was then filtered through a Microcon YM-30 column by centrifugation at 12,000 × g followed by three consecutive washes, each with 500 μl of binding buffer. The retentate containing RNA-protein complexes (150 μl) was counted in a β-scintillation counter. Counts from samples containing hnRNP-E1 were recorded as total binding, whereas counts from samples containing BSA reflected nonspecific binding. The specific binding for each concentration of radioligand was determined by subtracting the nonspecific binding from the results of total binding. The KD value was calculated from a Scatchard plot (14) using GraphPad Prism 4 from GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA).

Effect of RNA Interference of hnRNP-E1 mRNA on HPV16 L1 and L2 mRNA

Before the day of siRNA transfection, (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells were trypsinized, counted, and plated in 6-well plates at 1.4 × 105 cells/well in 2.5 ml of F-LF medium, so that cells were 35–45% confluent after overnight culture. Cells were transfected with either 10 nm predesigned Stealth RNA (siRNA-hnRNP-E1/PCBP1) (15) or 10 nm scrambled negative stealth RNAi control (Invitrogen) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent, as described (11). Cells were trypsinized and harvested at 1, 2, and 3 days after transfection for qRT-PCR analysis of hnRNP-E1, hnRNP-E2, and HPV L1, L2, E6, and E7 mRNA levels. In addition, the rate of biosynthesis of newly synthesized hnRNP-E1 was also determined in transfected cells (11).

HPV16-Organotypic Raft Cultures

Before development of HPV16-organotypic raft cultures, (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL cells were adapted to either high folate F-medium (F-HF) or physiologically low folate F-medium (F-LF) containing 10% FBS, which contributed 13.6 nm 5-methyltetrahydrofolate to the F-LF medium, for over 25 weeks. NIH 3T3 cells were likewise adapted to modified F-HF or F-LF medium for over 10 weeks to ensure stable intracellular folate levels (10). Before being placed on the raft, (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells were cultured on mitomycin C-treated F-HF or F-LF NIH3T3 feeder layers, respectively.

To construct HPV16-organotypic rafts, rat tail type 1 collagen (3.71 mg/ml) (BD Biosciences) was used to coat BD BioCoat inserts (6-well plates; 3-μm pore size). The remaining collagen was impregnated with either F-HF- or F-LF-adapted NIH3T3 (4.5 × 105 cells/ml) and plated on collagen-coated inserts, following which the collagen was allowed to contract in 10% FBS-containing F-HF or F-LF medium, respectively, for 5 days at 37 °C in a continuous CO2 (5%) incubator. Then 50 μl of 1.4 × 106 cells/ml (7 × 104 cells) in keratinocyte-plating medium (consisting of F-HF or F-LF medium containing 0.5% FBS, insulin (5 mg/ml), cholera toxin (8.4 ng/ml), adenine (24 mg/ml), and hydrocortisone (0.4 mg/ml)) were plated onto the collagen rafts. Four days after plating keratinocytes, the rafts were placed on two 1-inch2 cotton pads (VWR Scientific, Media, PA) in a BD BioCoat Deep Well 6-well plate (BD Biosciences Labware) to lift to the air-liquid interface. The rafts were fed from below the insert with cornification medium (consisting of F-HF or F-LF medium (containing 1.88 mm Ca2+) supplemented with 10% FBS, insulin (5 mg/ml), cholera toxin (8.4 ng/ml), adenine (24 mg/ml), and hydrocortisone (0.4 mg/ml)) every other day. Fourteen days after being lifted to the air-liquid interface, one part of the rafts was fixed in 4% formalin, embedded in 2% agar in 1% formalin followed by paraffin and cut into 4-μm-thick cross-sections; other parts of the rafts were used for RNA and DNA isolation or electron microscopic analysis.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) for HPV16 Viral Load and Integration

To prepare HPV16-organotypic raft total DNA for analysis of the HPV16 viral load by qPCR, four 18-day-old HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts as well as four HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts were separately ground in 5 ml of Dulbecco's PBS with autoclaved sea sand (EMD Chemicals Inc.) using a mortar and pestle (Fisher). The resulting paste was clarified by centrifugation for 10 min at 4000 rpm in a refrigerated Beckman GPR centrifuge. After discarding the pellets, raft total DNA (including genomic and viral DNA) was extracted from the suspension using the NucleoSpin® blood kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co.). Briefly, the supernatant was incubated at 70 °C for 15 min in lysis buffer containing proteinase K, and after binding to the silica column and washing, the DNA was eluted in 100 μl of elution buffer. The DNA was stored at −20 °C until used for qPCR.

DNA copy numbers of HPV16 E6, E7, and E2 and GAPDH in 50 ng of raft total DNA were measured by qPCR in triplicate using the Platinum Quantitative PCR SuperMix-UDG kit (Invitrogen) and the ABI 7900 HT detection system (Applied Biosystems). Sequence-specific primers for GAPDH and HPV16 E6 and E7 were designed using the Invitrogen customer primer design online system; these sequences are shown in the supplemental data (under “Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), Primers, and Validation”). The oligonucleotide primers used in the measurement of HPV16 DNA integration into genomic DNA were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The assay for integration evaluated the ratio between HPV16 E2 DNA and HPV16 E6 DNA (16). An altered E2/E6 ratio is an established parameter that reflects integration into cellular DNA. The principle is that a unique region of the E2 open reading frame is most often deleted during HPV16 integration. This is targeted by one set of PCR primers and a probe, and another set targets the E6 open reading frame. In episomal form, both targets should be equivalent, whereas in integrated forms, the copy numbers of E2 would be less than those of E6. The primers for E2 were as follows: probe, 5′-6-FAM/CAC CCC GCC/ZEN/GCG ACC CAT A/3IABkFQ/-3′; forward primer, 5′-AAC GAA GTA TCC TCT CCT GAA ATT ATT AG-3′; and reverse primer, 5′-CCA AGG CGA CGG CTT TG-3′ (where 6-FAM represents 6-carboxyfluorescein; ZEN, an internal quencher 9 bases from the 5′ fluorophore, is an undisclosed proprietary agent; and IABkFQ is Dark Quencher Iowa Black® FQ). The primers for E6 were as follows: probe, 5′-6-FAM/CAG GAG CGA/ZEN/CCC AGA AAG TTA CCA CAG T/3IABkFQ/-3′; forward primer, 5′-GAG AAC TGC AAT GTT TCA GGA CC-3′; and reverse primer, 5′-TGT ATA GTT GTT TGC AGC TCT GTG C-3′. The probe/primer ratio in these experiments was 1:2.

Standard curves of HPV16 E6, E7, and E2 were generated for measurement of viral DNA copies, and standard curves of GAPDH were generated for normalizing the input DNA content. Briefly, standard curves were generated using 10-fold dilutions of HPV16 plasmid or amplified GAPDH DNA (from 101 to 107 copies). Amplifications were carried out using the ABI HT7900 sequence detection system; the cycle conditions for qPCR were 50 °C for 2 min and 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. The actual copy numbers of HPV E6, E7, and E2 and GAPDH were determined by qPCR using 50 ng of raft total DNA and were then normalized by the copy numbers of GAPDH.

The viral load was calculated by dividing the normalized copy number of HPV16 E6 DNA by 50 ng of raft total DNA and expressed as copies of HPV16 E6 DNA per ng of raft total DNA, according to the formula by Carcopino et al. (17), with the exception that we used the “ng of raft total DNA” in place of “cells” in that formula. The amount of integrated HPV16 E6 DNA was calculated by subtracting the copy number of HPV16 E2 episomal DNA from the total copy number of HPV16 E6 DNA (episomal and integrated). The percentage of HPV16 DNA that was integrated into genomic DNA was then determined by dividing the integrated HPV16 E6 DNA copy number by total HPV16 E6 DNA copy number, and the result was multiplied by 100.

Model for Implantation of HPV16-organotypic Rafts in Mice

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis. Four female mice from each of three strains (supplemental Table S1), beige nude XID (Hsd:NIHS-Lystbg Foxn1nuBtkxid), athymic nude (Hsd:athymic nude-Foxn1nu), and SHrNTM SCID (NOD.Cg-prkdcscidHrhr/NCrHsd), 4–6 weeks old and weighing 16–18 g, were obtained from Harlan Sprague-Dawley Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and acclimatized for 1 week at the Laboratory Animal Resource Center at the Indiana University School of Medicine.

Previous methods used to implant fragments of HPV-infected human foreskins under the skin of mice (18, 19) were modified for implantation of either HPV16-high folate- or HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts in all three species of immunodeficient mice. Briefly, 18-day-old HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts were washed with sterile Dulbecco's PBS, cut into 5 × 5 × 1-mm pieces, and transported in Petri dishes at 4 °C to the animal facility in either serum-free F-HF or F-LF medium, respectively. All mice remained deeply anesthetized before and throughout the surgical procedure. Under sterile conditions, a 1-cm midflank skin incision was made perpendicular to the spine below the costophrenic angle with scissors, and a subcutaneous pocket was created using a blunt forceps. A fragment from either an HPV16-high folate- or an HPV16-low folate-organotypic raft was then inserted subcutaneously and repositioned in a top-to-bottom orientation to facilitate angiogenesis of the raft from below, and the incision was closed with a surgical clip. After postoperative recovery from anesthesia, the mouse was transferred to a regular cage. The surgical clips were removed 1 week after surgery without anesthesia. The mice were then observed twice a week for tumor growth. Once tumors were established, measurements were taken on a regular basis (18, 19). Quantification of tumor growth was made using the formula described recently (20).

Following the transformation of an HPV16-low folate-organotypic raft into an aggressive tumor in a beige nude XID mouse, fragments (3 × 3 × 2 mm) from this primary tumor were transplanted into other immunodeficient mice. Following growth of these secondary tumors, additional immunodeficient mice were transplanted with fragments from these secondary tumors, and the subsequent growth of tertiary tumors was also monitored.

See supplemental data for details on preparation of unlabeled l-homocysteine and purified recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)-hnRNP-E1 fusion protein; determination of whether the RNA-protein interaction between the 3′-coding region of L2 mRNA and hnRNP-E1 is responsive to homocysteine; in vitro transcription-translation of HPV16 L2 mRNA; determination of whether HPV16 L2 single-stranded DNA binds to hnRNP-E1 in the presence of various concentrations of homocysteine; qRT-PCR, primers, and validation; measurement of intracellular homocysteine in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL cells; transient transfection of wild-type hnRNP-E1 into (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL cells; determination of whether HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(T)-rich single-stranded DNA binds hnRNP-E1; interaction of endogenous homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 with the HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(U)-rich cis-element within cells and effects on downstream CAT reporter signal; specific binding between hnRNP-E1 and various mutations of HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element; effects of l-homocysteine on various CAT reporter constructs transfected into (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells; analysis of the rates of biosynthesis and degradation of HPV16 L2 and L1 mRNA transcripts in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells by qRT-PCR; analysis of the rate of protein biosynthesis and degradation of HPV16 L2, L1, hnRNP-E1, and GAPDH in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells or (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells; source of antibodies; and tissue histology, immunohistochemistry, fluorescence microscopy, Western blot analysis, and electron microscopy.

RESULTS

Homocysteine Responsiveness of Interaction of HPV16 L2 mRNA and Purified Recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 in Vitro

Because incubation of l-homocysteine with purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 led to a covalent interaction with the protein (11), we tested the effect of homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 in binding to HPV16 L2 mRNA and in altering its translation in vitro. Fig. 1A demonstrates a dose-dependent increase in generation of HPV16 L2 RNA-bound GST-hnRNP-E1 protein complexes with increasing physiologically relevant concentrations of l-homocysteine that achieved saturability and that exhibited a supershift only with specific anti-hnRNP-E1 antiserum (9) on gel shift assays. Because HPV16 L2 single-stranded sense DNA did not interact with l-homocysteine-derivatized GST-hnRNP-E1 (Fig. 1B), the locus for interaction between homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 and HPV16 L2 was at the level of an RNA-protein interaction. As noted earlier for the binding interaction of hnRNP-E1 and folate receptor-α mRNA cis-element, there was a progressive increase in binding affinity between purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 and HPV16 L2 RNA cis-element as the concentration of l-homocysteine increased in the reaction mixture; thus, there was a reduction in KD from basal values of 1.6–0.5 nm at 50 μm l-homocysteine.

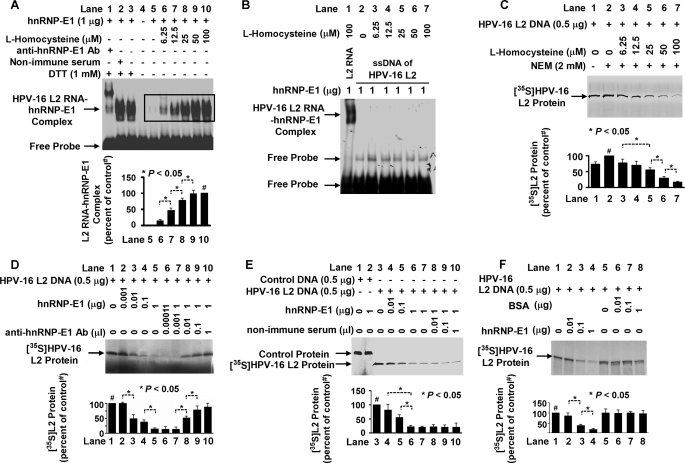

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of RNA-protein interactions involving purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 protein and HPV16 L2 RNA cis-element in the presence of increasing concentrations of l-homocysteine, leading to the translation of HPV16 L2 protein in vitro. A, gel shift analysis of the interaction of HPV16 L2 RNA cis-element (1 × 105 cpm) and GST-hnRNP-E1 protein in the absence or presence of various concentrations of l-homocysteine and the influence of nonimmune or anti-hnRNP-E1 antiserum on RNA-protein complex formation using 6% native PAGE and autoradiography. The pooled densitometric scanned data of RNA-protein complexes formed with increasing concentrations of l-homocysteine from three independent gel shift experiments are shown as a bar graph below one representative gel; these data are presented as the mean ± S.D. (error bars). The scanned area reflecting the L2 RNA-hnRNP-E1 protein signals formed with increasing concentrations of l-homocysteine is marked by a rectangle in the gel from lanes 5–10 and compared with the signal formed in the presence of 100 μm l-homocysteine in lane 10 (# signifies the 100% value). B, interaction between the single-stranded sense DNA (ssDNA) of HPV16 L2 and homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1. Lane 1 contains a positive control using HPV16 L2 RNA. C–F, in vitro translation of [35S]HPV16 L2 protein under various experimental conditions. In each of the following panels, the pooled densitometric scanned data of [35S]HPV16 L2 protein synthesized from three independent experiments are shown as a bar graph below one representative gel; these data are presented as the mean ± S.D. # in C, D, E, and F signifies the 100% value. C, effect of the addition of physiological concentrations of l-homocysteine on the biosynthesis of HPV16 L2 protein during in vitro translation. NEM, N-ethyl maleimide. D, effect of the addition of purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 during in vitro biosynthesis of HPV16 L2 (lanes 2–5) and effect of increasing concentrations of anti-hnRNP-E1 antiserum (anti-hnRNP-E1 Ab) in quenching the inhibitory effect of GST-hnRNP-E1 on HPV16 L2. E, effect of increasing concentrations of nonimmune serum on the translation of HPV16 L2 in the presence of purified recombinant GST-hnNP-E1. F, comparison of the effect of the addition of purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 versus BSA on HPV16 L2 protein synthesis.

Endogenous hnRNP-E1 is found in small quantities in the reticulocyte lysate of the translation reaction mixture (9, 11), so after quenching the excess (4.1 mm) β-mercaptoethanol extant in the commercial translation kit by 2 mm N-ethyl maleimide, the addition of increasing physiologically relevant concentrations of l-homocysteine led to a dose-dependent quenching of HPV16 L2 protein synthesis (Fig. 1C, lanes 3–7); these inhibitory effects were not due to premature degradation of HPV16 L2 mRNA during in vitro translation (supplemental Fig. S2). In addition, the in vitro translation of HPV16 L2 was mediated by hnRNP-E1 because there was a dose-dependent reduction in [35S]HPV16 L2 protein (Fig. 1D, lanes 2–5) upon the addition of increasing concentration of purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1, which was reversed in a dose-dependent manner by the addition of increasing concentrations of anti-hnRNP-E1 antiserum to the reaction mixture (Fig. 1D, lanes 6–10). By contrast, increasing concentrations of non-immune serum (Fig. 1E, lanes 8–10) had no effect in reversing the inhibitory effect of purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 on HPV16 L2 synthesis. Moreover, an unrelated protein like bovine serum albumin (Fig. 1F, lanes 6–8) had no such effect in reducing the translation of [35S]HPV16 L2 protein in vivo. Collectively, these in vitro translation studies suggested that the enhanced binding between the cis-element in the 3′ coding region of HPV16 L2 mRNA and hnRNP-E1 that was induced by l-homocysteine (Fig. 1C) led to the inhibition of HPV16 L2 viral capsid protein synthesis.

Determination of Thiol Content of (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF Cells and Effects on RNA-Protein Interaction

(HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL cells propagated long term in F-HF and F-LF media had comparable cell doubling times of 29.5 and 30 h, respectively. Simultaneous measurements of various intracellular thiols in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells that were shifted to F-LF medium over 12 weeks confirmed a progressive increase in only homocysteine to nearly 3 times more than base line, from 7 to ∼20 μm by 12 weeks (Fig. 2, A–D). This suggested that the low folate environment, which led to the accumulation of more homocysteine, could influence the interaction of HPV16 L2 RNA cis-element and endogenous hnRNP-E1. Because (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF expressed the full complement of HPV16 RNA (supplemental Fig. S1, discussed below), we compared the expression of HPV16 RNA between (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells.

FIGURE 2.

Determination of the extent of accumulation of intracellular thiols in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells as a function of time following transfer to low folate medium (A–D) and comparison of the expression of HPV16 RNA and protein in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells under various experimental conditions (E–H). Unless otherwise specified, the results are presented as the mean ± S.D. (error bars) from three independent sets of experiments (n = 3) with each data point performed in triplicate. A–D, concentration of intracellular homocysteine, cysteine, methionine, and cystathionine in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells transferred to low folate (F-LF) medium over 12 weeks. Due to prohibitive costs, this longitudinal experiment was carried out once; the results from each data point were derived from the mean of three samples. The curve-fitting analyses were determined by linear regression. E–H, comparison of expression of HPV16 RNA and proteins (L1, L2, E6, and E7) in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells (HPV16 HF and HPV16 LF cells, respectively) using qRT-PCR (E), Western blot analysis (F), following transfection of hnRNP-E1 (using a plasmid, phnRNP-E1) in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells or a pCAT (control) plasmid (G), and the effect of increasing concentrations of extracellular l-homocysteine on HPV16 L1 and L2 RNA levels in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells (H).

Measurement of Various HPV16 RNA in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF Cells

In order to validate the qRT-PCR method that was used to measure small quantities of HPV16 RNA in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells, we determined individual standard curves between target RNA (HPV16 L2, L1, E6, and E7 as well as human folate receptor-α, hnRNP-E1, and reference RNA (GAPDH), which demonstrated comparable high efficiency of amplification of the target RNA and the reference RNA. Supplemental Fig. S1 demonstrates qRT-PCR profiles with the standard curve of HPV16 L1 and GAPDH (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B) as well as HPV16 L2 and GAPDH (supplemental Fig. S1, C and D). Both uninfected BC-1-Ep/SL (supplemental Fig. S1E) and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells (supplemental Fig. S1F) expressed folate receptor-α and hnRNP-E1; however, only (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells expressed both HPV16 L1 and L2 as well as HPV16 E6 and E7 RNA. Thus, qRT-PCR easily discriminated between cells that did and did not contain the HPV16 genome. Next, the RNA expression of HPV16 L2, L1, E6, and E7 in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells was compared.

Fig. 2E demonstrates a much lower amount of HPV16 L2 RNA in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF than (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells, with no difference in the amplification plots of GAPDH; surprisingly, however, comparable data were also obtained with HPV16 L1 RNA (Fig. 2E). Thus, when compared with control (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells, the RNA expression of both HPV16 L2 and L1 in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells was significantly decreased (97 and 90%, respectively) (Fig. 2E). By contrast, analysis of HPV16 E6 and E7 RNA did not show significant differences in expression in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells. Fig. 2F also confirmed a greater inhibition in the expression of L2 and L1 proteins (98 and 90%, respectively) in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells when compared with (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells. The observed reduction of HPV16 L2 and L1 was not due to up-regulation of hnRNP-E1 in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells because hnRNP-E1 protein expression was only 80% of that found in high folate cells (Fig. 2F). Nevertheless, hnRNP-E1 was incriminated in reducing HPV16 L1 and L2 mRNA expression because (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells that were transiently transfected with a plasmid containing hnRNP-E1 exhibited ∼65% inhibition of expression of HPV16 L2 RNA and ∼45% inhibition of expression of HPV16 L1 RNA when compared with values obtained with pCAT (control) plasmid (Fig. 2G). However, because there was no interaction between hnRNP-E1 and single-stranded HPV16 L2 DNA (Fig. 1B), this suggested that the reduction in HPV16 L2 RNA (and HPV16 L1 RNA), following either stable propagation of cells in low folate medium (Fig. 2E) or following transfection of hnRNP-E1 (Fig. 2G), was through effects on a putative locus that was distinct from HPV16 L2 RNA. Moreover, the greater reduction of HPV16 L1 and L2 in low folate cells (Fig. 2, E and F) suggested that this locus was responsive to homocysteine-derivatized hnRNP-E1.

Because extracellular l-homocysteine can enter cultured human cells by an active cysteine transporter system (21), we determined if abruptly increasing the concentration of l-homocysteine in medium led to acute changes (over 2 h) in HPV16 L1 and L2 in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells. Fig. 2H confirmed a dose-dependent reduction in intracellular HPV16 L1 and L2 RNA when (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of l-homocysteine. Because effects were also noted at 12.5 and 25 μm l-homocysteine, this suggested that the interaction of endogenous hnRNP-E1 and HPV16 RNA occurred within cells at physiologically appropriate concentrations of homocysteine that would be found even in mild folate deficiency.

Interaction of hnRNP-E1 with HPV16 57-nucleotide Poly(U)-rich cis-Element

A potential candidate locus to mediate the profound dual reduction of HPV16 L2 and L1 expression in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells was a 57-nucleotide RNA domain in the early polyadenylation element of the HPV16 genome (Fig. 3A). This domain, which is located upstream of L2̂L1 genes, can control the expression of L2 and L1 genes (13) and is also known to bind other members of the hnRNP family (13). Fig. 3B shows that the addition of increasing concentrations of l-homocysteine to a mixture of purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 and this putative HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element led to progressively greater RNA-protein complex signals in a dose-dependent, saturable manner. There was a supershift of the RNA protein signal with anti-hnRNP-E1 antibody (Fig. 3B, lane 9) with no supershift with non-immune serum (not shown), which confirmed the presence of hnRNP-E1 within the RNA-protein complexes. By contrast, there was no interaction between homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 and HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(T)-rich single-stranded sense DNA (Fig. 3C), confirming that the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA domain only interacted with homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1.

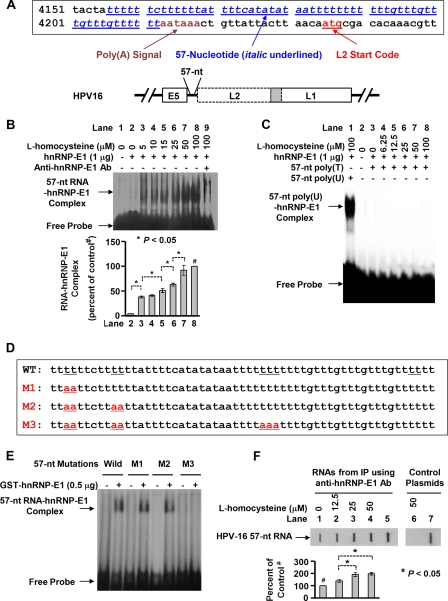

FIGURE 3.

Analysis of the specificity of interaction of the HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(U)-rich RNA cis-element with purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 using gel shift assays, mutation studies in vitro, and slot blot hybridization analysis to detect enrichment of similar intracellular RNA-protein complexes following exposure of (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells to increasing physiologically relevant concentrations of l-homocysteine. A, DNA sequence of the HPV16 57-nucleotide cis-element in the early polyadenylation element upstream of L2̂L1 genes (in italic type and underlined in blue) in the HPV16 genome in the upper panel; the position of the poly(A) signal is shown in brown type, and the L2 start code is indicated in red type. The lower panel shows the location of the 57-nucleotide sequence (57-nt) upstream of the HPV16 L2/L1 genes; the overlapping sequence between L2 and L1 is shown in the shaded portion. B, gel shift assays of the interaction of the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element (57-nt RNA) with hnRNP-E1 in the presence of increasing concentrations of l-homocysteine (0–100 μm; lanes 2–9). The pooled densitometric scanned data of RNA-protein complexes formed with increasing concentrations of l-homocysteine from three independent gel shift experiments are shown as a bar graph below one representative gel; these data are presented as the mean ± S.D. All densitometric signals were compared with the control (lane 8), reflecting maximal signal obtained with 100 μm l-homocysteine (marked by # in the bar graph). There was a supershift of the RNA-protein complex signal with anti-hnRNP-E1 antibody in lane 9. C, gel shift assay of the interaction between HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(T)-rich single-stranded sense DNA (57nt poly(T)) and purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 in the presence of increasing concentrations of l-homocysteine (lanes 3–8) compared with positive control employing HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(U) cis-element (lane 1). This gel is representative of three separate experiments that yielded comparable results. D, wild-type HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element and various mutations (M1–M3) within this sequence that are marked in red and underlined. E, gel shift analysis of the interaction of hnRNP-E1 with either wild type [α-32P]HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element (pWT) or various mutations of [α-32P]HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element (M1–M3) in the presence of 50 μm l-homocysteine. This gel is representative of three separate experiments that yielded comparable results. F, slot blot hybridization analysis to detect intracellular RNA-protein complexes of HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element bound to hnRNP-E1 within 2 h after the exposure of (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells to increasing physiologically relevant concentrations of l-homocysteine (see “Experimental Procedures” for methodological details). Intracellular RNA-protein complexes were cross-linked and immunoprecipitated with anti-hnRNP-E1 antiserum, and, following RNase treatment and proteolysis of the immunoprecipitate, equal concentrations of the released small RNA fragments (RNAs from IP) were tested for the presence of HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element using a 35S-labeled antisense probe to the 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element (lanes 1–5) or a control 35S-labeled sense probe (lanes 6 and 7). Denatured pYS57 plasmid DNA used as additional positive controls (lanes 5 and 7) were also tested for hybridization with this antisense or sense probe. The hybridization signals in response to l-homocysteine are compared with base-line values (denoted as 100% detected with no addition of l-homocysteine). The result of densitometric scans of the signals is shown below the slot blot and is presented as the mean ± S.D. (error bars) from three independent sets of experiments (n = 3). The 100% control value is indicated by # in lane 1. IP, immunoprecipitation.

To further evaluate the specificity of the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element for binding purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 in the presence of l-homocysteine, we induced specific mutations within the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element (Fig. 3D). As shown in Fig. 3E, although there was interaction between purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 and some mutations (pM1 and pM2) similar to wild-type (pWT) HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element in the presence of 50 μm l-homocysteine, there was no interaction when an additional mutation (pM3) was introduced, confirming the specificity of this RNA-protein interaction.

To determine if there was physiological interaction of hnRNP-E1 with this HPV16 57-nucleotide cis-element within cells in response to homocysteine, we captured these RNA-protein complexes in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells as a function of the addition of physiologically relevant concentrations of l-homocysteine, as described recently (11). This was achieved by first cross-linking the endogenous RNA-protein complexes with UV light, followed by specific immunoprecipitation using anti-hnRNP-E1 antiserum. Then after cleaving unprotected RNA that was not in close apposition to the immunoprecipitated hnRNP-E1 protein, the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element (as well as other RNA cis-elements) that remained cross-linked to hnRNP-E1 were released by proteolysis of hnRNP-E1. Following this step, equivalent amounts of the remaining RNA were tested for the capacity to hybridize under stringent conditions with 35S-labeled antisense probe to the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element using slot blot hybridization analysis. As shown in Fig. 3F, lanes 2–4, there was an l-homocysteine-induced dose-dependent increase in signal from hybridization with HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element antisense probe when compared with control samples to which l-homocysteine was not added (Fig. 3F, lane 1). Moreover, the specificity of this hybridization was shown by the lack of hybridization signal (Fig. 3F, lane 6) using the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element sense probe. The positive controls using denatured pYS57 (Fig. 3F, lanes 5 and 7) confirmed signals of hybridization with both 35S-labeled antisense and 35S-labeled sense 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element probes. Collectively, these results reflected the capture of HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element-bound hnRNP-E1 protein complexes within (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells as a function of increasing intracellular l-homocysteine concentrations.

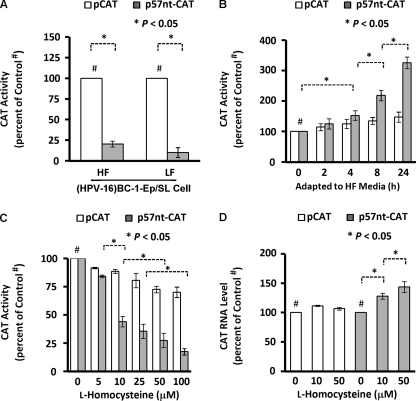

Next, we sought to define the functional significance of the interaction between endogenous homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 and the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element in cells. Transfecting a plasmid containing this HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element placed proximal to a CAT reporter, p57nt+CAT, into (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells resulted in p57nt+CAT signals of 20 and 10%, respectively, when compared with pCAT controls (Fig. 4A). This suggested that the greater interaction of endogenous homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 with p57nt+CAT reporter plasmids in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells, which contained nearly 3-fold more intracellular homocysteine than (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells (Fig. 2A), resulted in a functional effect. (The basis for a significant reduction in p57nt+CAT signals even in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells when compared with pCAT control is addressed in experiments leading to Table 1; see below). Earlier, we showed that abruptly exposing HeLa-IU1-LF cells (that were stably propagated in low folate medium) to high folate medium (containing over 250-fold more folate) progressively lowered the intracellular homocysteine toward basal values by 24 h (10). When (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells were similarly exposed to high folate medium (Fig. 4B), the p57nt+CAT reporter signals progressively increased as a function of time to over 3-fold more than basal values by 24 h, but pCAT controls increased only marginally. This suggested that upon folate repletion, the reduced intracellular homocysteine led to a disinhibition of CAT signals compared with base-line controls, reflecting a reduced interaction of endogenous hnRNP-E1 with p57nt+CAT reporters. Next, we determined if increasing the concentration of l-homocysteine in medium led to acute changes (by 2 h) in p57nt+CAT reporter signals in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells. Fig. 4C confirmed that p57nt+CAT reporter signals progressively decreased with increasing physiologically relevant concentrations of l-homocysteine, whereas pCAT controls were not as affected. This was not because of any reduction in the level of p57nt+CAT mRNA in these cells. In fact, as shown in Fig. 4D, the measured mRNA levels of pCAT control were not significantly changed, whereas the mRNA levels of p57nt+CAT were slightly increased (up to 1.5-fold) with the addition of 0, 10, and 50 μm l-homocysteine. These data supported the likelihood that the observed inhibitory effects of l-homocysteine on the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element-CAT construct-related CAT activity (Fig. 4C) were at a translational level.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of CAT activity following the transfection of the HPV16 57-nucleotide cis-element-driven CAT reporter constructs into (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells and after the acute modulation of the intracellular homocysteine concentrations by altered culture conditions. The results are presented as the mean ± S.D. (error bars) from three independent sets of experiments (n = 3) with each data point performed in triplicate. A, CAT reporter activity following transfection of (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells (HF) and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells (LF) with either control plasmids (pCAT; open bars) or plasmids in which the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element was placed proximal to CAT reporter (p57nt-pCAT; shaded bars). pSV-β-gal was used as an internal control, and the chemiluminescent assay for quantitative determination of β-galactosidase activity in transfected cells was employed to monitor transfection efficiency (10). All data were normalized by internal standard and protein content of each treatment. B, CAT activity from (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells that were transfected with either pCAT or p57nt+CAT plasmids, following which cells were abruptly transferred to high folate medium, and CAT activity was determined as a function of time. C, CAT activity from (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells transfected with either pCAT or p57nt+CAT plasmid DNA. After a 48-h incubation in high folate medium, cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of l-homocysteine for 2 h and then assessed for CAT activity. D, expression of CAT mRNA in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells that were transfected with either pCAT or p57nt+CAT plasmid DNA and then exposed to increasing concentrations of l-homocysteine.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the binding affinity between purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 and HPV16 L2 RNA cis-element and HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element at equimolar concentrations of l-homocysteine and l-cysteine, and evidence of a lower dissociation constant (KD) with l-homocysteine than l-cysteine for the RNA-protein interaction involving the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element

The results are presented as the mean ± S.D. from three independent sets of experiments with each data point performed in triplicate.

| Thiol amino acids | [35S]RNA | KD | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| nm | |||

| l-Homocysteine (25 μm) | [35S]HPV16 L2 | 0.517 ± 0.039 | |

| l-Homocysteine (25 μm) | [35S]HPV16 57 nt | 0.223 ± 0.021 | 0.031 |

| l-Cysteine (15 μm) | [35S]HPV16 57 nt | 1.098 ± 0.207 | |

| l-Homocysteine (15 μm) | [35S]HPV16 57 nt | 0.404 ± 0.123 | 0.001 |

Taken together, these results suggested that interaction of endogenous homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 with the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells inhibited downstream genes and could explain, in part, the observed reduction in levels of HPV16 L2 and L1 mRNA and protein (Fig. 2, E and F).

Comparison of Dissociation Constants of Interaction between Homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 and HPV16 L2 mRNA cis-element versus HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-Element

Because there were two distinct loci in HPV16 RNA that interacted with homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1, we compared the binding affinity of these two RNA-protein interactions under physiological conditions of l-homocysteine. Formal dissociation constant studies using purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 at physiological folate-deficient conditions (25 μm l-homocysteine) revealed a consistently lower KD in the interaction of homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 with [35S]HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element (KD = 0.22 nm) when compared with [35S]HPV16 L2 RNA (KD = 0.52 nm) (Table 1). These studies suggest that the binding affinity of homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 with the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element domain was greater under physiological conditions of folate deficiency and therefore more likely to contribute to the net reduction of HPV16 L1 and L2 mRNA and proteins when compared with the interaction of homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 with HPV16 L2 mRNA.

Because of comparably high basal concentrations of cysteine and homocysteine in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells (Fig. 2, A and B), we determined if there were subtle differences in binding affinity between the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element and purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 protein at equimolar (15 μm) concentrations of l-cysteine and l-homocysteine. Table 1 shows that binding affinity was significantly greater in the presence of l-homocysteine (KD = 0.40 nm) than l-cysteine (KD = 1.1 nm). These data predicted that l-homocysteine had a greater capacity to stimulate interaction of endogenous hnRNP-E1 with the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element than l-cysteine in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells. Parenthetically, these results can also explain, in part, why transient transfection of p57nt+CAT into (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells (which contained an estimated 16 μm cysteine and 7 μm homocysteine) reduced CAT-signals to 20% of controls (Fig. 4A).

Effect of RNA Interference of hnRNP-E1 mRNA on HPV16 L1 and L2 mRNA in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF Cells

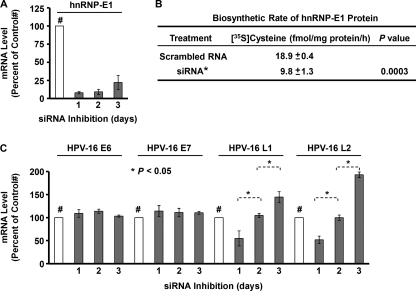

RNA interference (RNAi) revealed that siRNA elicited maximal effect in reducing hnRNP-E1 mRNA by over 90% within 1 day, which persisted over the ensuing 3 days (Fig. 5A). This siRNA had no effect on the closely related hnRNP-E2 mRNA (11). Evaluation of the biosynthetic rate of newly synthesized hnRNP-E1 protein 48 h after RNAi of hnRNP-E1 mRNA revealed a significant reduction when compared with controls using scrambled RNA (Fig. 5B). This predicted that RNAi of hnRNP-E1 mRNA could affect the level of HPV16 L2 and L1 in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells. As shown in Fig. 5C, there was no change in HPV16 E6 and E7 mRNA over the subsequent 3 days in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells following RNAi of hnRNP-E1 mRNA; this was consistent with a lack of effect of homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 on E6 and E7 mRNA and protein (Fig. 2). By contrast, there was a significant time-dependent increase in levels of HPV16 L2 and L1 mRNA over the subsequent 3 days (Fig. 5C). This reflected an escape from the inhibitory effects of interaction of HPV16 RNA with homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 protein and confirmed the specificity of effects of hnRNP-E1 on HPV16 L1 and L2.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of RNA interference against hnRNP-E1 mRNA on the mRNA level of hnRNP-E1 (A), the biosynthetic rate of newly synthesized hnRNP-E1 protein (B), and levels of HPV16 E6, E7, L1, and L2 RNAs in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells that were stably propagated in low folate medium (C). The results are presented as the mean ± S.D. (error bars) from three independent sets of experiments (n = 3) with each data point performed in triplicate. A, (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells were transfected with either scrambled control RNA (open bar) or siRNA against hnRNP-E1 mRNA (shaded bars) and harvested at 1, 2, and 3 days after transfection for RNA purification and qRT-PCR to determine the mRNA level of hnRNP-E1 (A) and HPV16 E6, E7, L1, and L2 (C). The data using scrambled RNA are expressed as 100% and were unchanged over 3 days, and data on inhibited hnRNP-E1 mRNA or other HPV related RNA are expressed as a percentage of control values. #, the 100% control value. The maximum inhibition of hnRNP-E1 mRNA on the first day was consistently confirmed on four independent occasions.

Comparison of Rates of Biosynthesis and Degradation of HPV L1 and L2 mRNAs and HPV16 L1 and L2 Proteins in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF Cells

As shown in Table 2, the rates of biosynthesis of L2 and L1 RNA transcripts were significantly decreased in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF when compared with (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells. Table 2 also shows that the rate of degradation of L2 and L1 RNA in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells was significantly increased when compared with (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells. Together, these data were consistent with a conclusion that the binding of homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 to the HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(U)-rich cis-element led to a reduction in the rate of biosynthesis of both L2 and L1 mRNA as well as an increase in degradation of these mRNA transcripts, and these events probably contributed to the net reduction in L2 and L1 RNA levels in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells (Fig. 2). (Because there was no interaction between homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 and single stranded HPV16 DNA, the term “biosynthesis of RNA” used here refers to the rate of formation of mature HPV16 L2 and L1 RNA.)

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the biosynthetic and degradation rates of HPV16 L2 and L1 mRNAs in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL cells that were stably propagated as monolayers in either HF or LF medium

The results are presented as the mean ± S.D. from three independent sets of experiments with each data point performed in triplicate.

| Cell type | Total RNA | p value |

|---|---|---|

| fmol/ng/h | ||

| Biosynthetic rate of HPV16 L2 mRNA | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 8.49 ± 0.38 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 4.95 ± 0.27 | 0.0002 |

| Biosynthetic Rate of HPV16 L1 mRNA | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 13.33 ± 0.82 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 7.07 ± 0.36 | 0.0003 |

| Degradation Rate of HPV16 L2 mRNA | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 0.34 ± 0.03 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 0.74 ± 0.04 | 0.0002 |

| Degradation Rate of HPV16 L1 mRNA | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 0.42 ± 0.03 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 0.0023 |

The protein biosynthetic rates of GAPDH and L1 were comparable in both (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells (Table 3). However, the rate of protein biosynthesis of L2 in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells was about one-half the value obtained with (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells. These data are compatible with Fig. 1, where the independent interaction of L2 mRNA and homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 led to reduction in synthesis of L2 in vitro. In addition, the rate of biosynthesis of hnRNP-E1 was lower in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells (Table 3). Thus, although the biosynthetic rate of hnRNP-E1 in low folate media was lower (consistent with a lower net amount of hnRNP-E1, as noted in Fig. 2F), the accumulation of nearly 3-fold more intracellular homocysteine could result in the homocysteinylation of endogenous hnRNP-E1, leading to efficient reduction in HPV16 L1 and L2 via effects on the HPV16 57-nucleotide cis-element and the L2 mRNA cis-element.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the protein biosynthetic rates of HPV16 L2, HPV16 L1, hnRNP-E1, and GAPDH proteins in HPV16 -harboring human keratinocytes that were stably propagated as monolayers in either high folate medium ((HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF) or low folate medium ((HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF)

The results are presented as the mean ± S.D. from three independent sets of experiments with each data point performed in triplicate.

| Cell type | [35S]Cysteine | p value |

|---|---|---|

| fmol/mg protein/h | ||

| Biosynthetic rate of HPV16 L2 protein | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 108.45 ± 5.08 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 54.99 ± 0.27 | 0.0001 |

| Biosynthetic rate of HPV16 L1 protein | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 85.71 ± 1.46 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 84.29 ± 1.89 | 0.3618 |

| Biosynthetic rate of hnRNP-E1 protein | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 94.77 ± 3.88 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 49.29 ± 4.45 | 0.0002 |

| Biosynthetic rate of GAPDH protein | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 77.85 ± 4.12 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 80.22 ± 3.52 | 0.4921 |

The rates of protein degradation of hnRNP-E1 and GAPDH were comparably unchanged in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF and (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells (Table 4). However, the rate of degradation of HPV16 L1 protein was 1.7-fold higher, whereas that of HPV16 L2 protein was 2.4-fold higher in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells when compared with (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells. Thus, the increased degradation of HPV16 L2 and L1 protein that was independent of effects on HPV16 L2 and L1 RNA degradation could be yet another contributor to the net reduction in L2 and L1 in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of the protein degradation rates of HPV16 L2, HPV16 L1, hnRNP-E1, and GAPDH proteins in HPV16 -harboring human keratinocytes that were stably propagated as monolayers in either high folate medium ((HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF) or low folate medium ((HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF)

The results are presented as the mean ± S.D. from three independent sets of experiments with each data point performed in triplicate.

| Cell type | [35S]Cysteine | p value |

|---|---|---|

| fmol/mg protein/h | ||

| Degradation rate of HPV16 L2 protein | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 0.543 ± 0.082 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 1.291 ± 0.129 | 0.001 |

| Degradation rate of HPV16 L1 protein | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 0.945 ± 0.034 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 1.555 ± 0.205 | 0.007 |

| Degradation rate of hnRNP-E1 protein | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 0.633 ± 0.032 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 0.624 ± 0.027 | 0.723 |

| Degradation rate of GAPDH protein | ||

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF | 0.637 ± 0.025 | |

| (HPV-16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF | 0.702 ± 0.042 | 0.081 |

Collectively, these biosynthesis and degradation studies at the mRNA and protein level (Tables 2–4) demonstrated that (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells exhibited (i) reduced rates of biosynthesis of both HPV16 L1 and L2 RNA, (ii) increased degradation rates of both HPV16 L1 and L2 RNA, (iii) reduced rates of biosynthesis of HPV16 L2 protein, and (iv) increased rates of degradation of both HPV16 L1 and L2 proteins when compared with (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells. Taken together, the combination of these changes can explain the basis for the profound reduction of HPV16 L1 and L2 in folate-deficient (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells.

Comparison of HPV16 Viral Capsid Proteins, Viral Load, Viral Particles, and Viral Integration in HPV16-organotypic Rafts Developed in either Low Folate or High Folate Medium

In order to define the physiological consequences of the HPV16 RNA-hnRNP-E1 interaction, we switched studies from the use of (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL keratinocytes propagated as monolayers to (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL keratinocyte-derived HPV16-organotypic rafts (12). In this model, HPV16-harboring keratinocytes were stimulated to differentiate so that the HPV16 life cycle would be operative (3, 6); HPV16 L1 and L2 would be generated late in the HPV16 life cycle within (superficial) differentiated layers of these HPV16-organotypic rafts; and complete 55-nm HPV16 viral particles would be found in the topmost layers of these rafts. Accordingly, (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF and -LF cells were developed into HPV16-high folate- and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts, respectively. The use of a slightly higher concentration of folate (13.6 nm 5-methyltetrahydrofolate) in HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts (as opposed to the 6.8 nm 5-methyl-tetrathydrofolate that was used for (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF monolayers) allowed for better quality rafts to be generated that did not compromise the capacity for differentiation (supplemental Fig. S3). Differentiation in HPV16-high folate- and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts was confirmed using histology (supplemental Fig. S3, A and B); immunofluorescence (supplemental Fig. S3, C and D) with filaggrin, a filament-associated protein that binds to keratin fibers in epithelial cells and is a bona fide differentiation marker (22); immunohistochemistry (supplemental Fig. S3, F, G, I, and J); and Western blots (supplemental Fig. S3, E and H) to measure keratin 10 and filaggrin. Although there were subtle architectural abnormalities arising from disordered proliferation in the basal layers of HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts when compared with HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts, this was comparable with that seen in folate-deficient murine fetal epithelial tissues (23), where differentiation of keratinocytes in the skin was also retained.

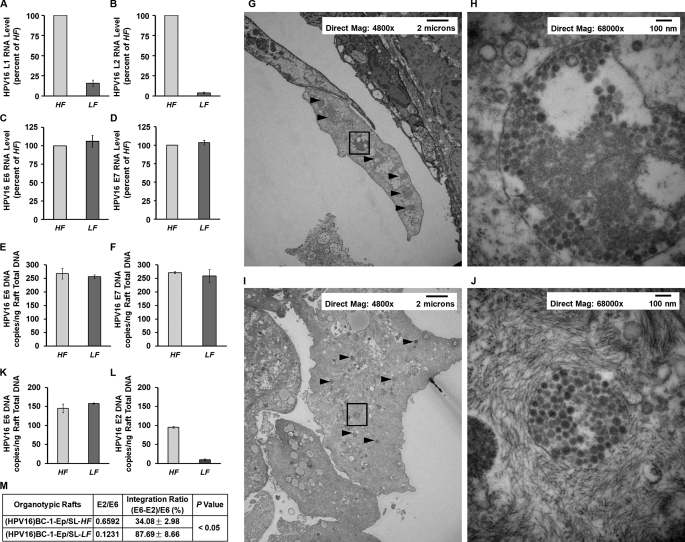

As noted with monolayers of HPV16-harboring keratinocytes in low folate medium (Fig. 2), there was a marked reduction of HPV16 L1 and L2 mRNA in HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts (Fig. 6, A and B) without changes in HPV16 E6 or E7 RNA (Fig. 6, C and D) when compared with HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts. In addition, there were no differences in HPV16 DNA viral load when comparing HPV16-high folate- and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts (Fig. 6, E and F), indicating no perturbation of the amplification step in the HPV16 life cycle of these rafts. The inability of HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts to generate HPV16 L1 and L2 viral capsid proteins despite a large amount of amplified HPV DNA predicted a net reduction in the number of HPV16 55-nm viral particles when compared with HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts. This was confirmed by electron microscopy of the topmost differentiated layers of HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts (Fig. 6, G and H) and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts (Fig. 6, I and J). The arrowheads point to several large clumps of viral particles in the ×4,800 magnification panel of HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts (Fig. 6G), and a higher magnification of ×68,000 of a boxed square from this panel is shown in Fig. 6H, where an abundance of 55 nm HPV16 viruses were seen. This sharply contrasts with comparable magnification views from HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts, which exhibited a marked reduction of clumps of viruses (arrowheads in the ×4,800 magnification panel; Fig. 6I). A boxed square from Fig. 6I that was magnified in Fig. 6J revealed 55-nm viruses, confirming that differentiation of HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts was not compromised; however, the net number of these viral particles was less than that in HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts (Fig. 6, compare I and G).

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of HPV16 RNA (A–F), HPV16 viral load (E and F), HPV16 viral particles (G–J), and HPV16 DNA integration into genomic DNA (K–M) in HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts (HF) and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts (LF). Unless otherwise specified, the results are presented as the mean ± S.D. from three independent sets of experiments (n = 3) with each data point performed in triplicate. A–D, expression of HPV16 L1 RNA (A), HPV16 L2 RNA (B), HPV16 E6 RNA (C), and HPV16 E7 RNA (D) from HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts (light shaded bars) and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts (dark shaded bars). E and F, determination of HPV16 E6 DNA (E) and HPV16 E7 DNA (F) viral load from HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts (light shaded bars) and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts (dark shaded bars). G–J, photomicrographs of electron microscopy frames from the uppermost layer of HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts (G and H) and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts (I and J) at lower magnification of ×4,800 (G and I) and higher magnification of ×68,000 (H and J). Clumps of HPV16 viral particles are identified by arrowheads in G and I; one of these clumps in G and I identified by a boxed square is shown at a higher magnification of ×68,000 in H and J, respectively. The magnification and scale in each of these frames are shown in the top. Note that HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts contained smaller clumps of HPV16 viruses and overall lesser numbers of 55-nm HPV16 viruses per clump in higher magnification frames. K–M, comparison of HPV16 E6 and E2 DNA ratios as a reflection of the extent of integration of HPV16 DNA into the genomic DNA of rafts in HPV16-high folate-oganotypic rafts and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts (K and L). The amount of integrated HPV16 E6 DNA was calculated by subtracting the copy number of HPV16 E2 episomal DNA from the total copy number of HPV16 E6 DNA (episomal and integrated). The percentage of HPV16 DNA that was integrated into genomic DNA was then determined by dividing the integrated HPV16 E6 DNA copy number by total HPV16 E6 DNA copy number, and the result was multiplied by 100 (M).

Because of this significant discordance between HPV16 DNA viral load and the number of actual HPV16 viral particles observed on electron microscopy in HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts, we investigated if there was a greater degree of integration of these apparently “capsid-less” HPV16 DNA into genomic DNA. The method to determine the extent of integration of HPV16 DNA into genomic DNA was based on comparative measurement of the absolute values of the HPV16 E2 and E6 open reading frames in DNA samples from HPV16-high folate- and HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts. In episomal form, the ratio of E2 to E6 is 1. However, ratios of E2 to E6 of less than 1 indicate the presence of both integrated and episomal forms. This is because the E2 primers and probe locations were selected to recognize the E2 hinge region, which is the part of the E2 open reading frame that is most often deleted upon HPV16 viral integration into cellular DNA (16, 24). Fig. 6K depicts the data on HPV16 E6 DNA copies/ng of raft total DNA, whereas Fig. 6L shows HPV16 E2 DNA copies/ng of raft total DNA. When compared with HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts, the HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts exhibited a very low E2/E6 ratio. Thus, low folate rafts contained ∼88% HPV16 DNA integration into genomic DNA when compared with ∼34% in high folate rafts (Fig. 6M). (The basal value of 34% integration in the host DNA of HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts may have arisen during earlier immortalization of keratinocytes by HPV16 (12).)

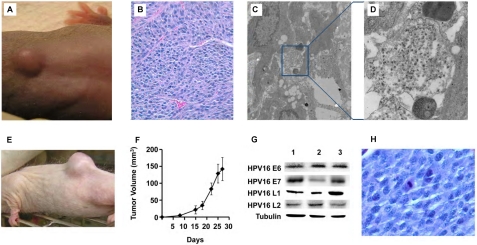

Evaluation of Potential for Malignant Transformation of HPV16-High Folate- or HPV16-Low Folate-organotypic Rafts Implanted Subcutaneously in Different Species of Immunodeficient Mice

To define the consequences of high level integration of HPV16 into the genomic DNA of HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts, we tested the hypothesis that this degree of integration was a potentially dangerous implant in a susceptible immunodeficient host. Among the three species of mice with varying degrees of immunodeficiency studied (supplemental Table S1), athymic nude mice have no T cells, but they do have B cells as well as natural killer cells; SHrNTM SCID mice have no B or T cells but do have some (albeit impaired) natural killer cell activity (the immunodeficiency is “leaky” because mice can develop some immunoglobulins as they age (19)); and, finally, beige nude XID mice appear to have no B, T, or natural killer cells and are the most immunodeficient. Accordingly, we evaluated the growth potential of a small fragment of either HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts or HPV16-low folate-organotypic rafts that was subcutaneously implanted in either folate-replete athymic nude or SHrNTM SCID or beige nude XID mice (2 mice per raft variable). By the 12th week, a small subcutaneous tumor (Fig. 7A) developed in one of the two beige nude XID mice implanted with a fragment of an HPV16-low folate-organotypic raft (which contained 88% HPV16 DNA integration into cellular DNA). This tumor grew steadily over the next 2 weeks to 2 cm3 but then rapidly increased in size over the next 10 days to 10 cm3, which mandated euthanasia. On light microscopy, histological evaluation of cells revealed a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio with an open chromatin, mitotic figures, and significant angiogenesis (Fig. 7B). We could also identify viral particles within the tumor on electron microscopy (Fig. 7, C and D). By contrast, there was no growth in HPV16-high folate-organotypic rafts implanted subcutaneously in two other beige nude XID mice; nor was there growth of HPV16-organotypic rafts propagated in either low folate or high folate among the other two species of athymic nude or SHrNTM SCID mice. We then tested whether subcutaneous transplantation of a small fragment of the HPV16-low folate-organotypic raft-derived primary tumor could grow in other folate-replete immunodeficient mice. The results revealed that rapidly growing secondary tumors developed in all three beige nude mice and in one of one athymic nude mouse within 2 weeks. Furthermore, a fragment from a secondary tumor from a beige nude XID mouse also developed into a tertiary tumor within 2 weeks when implanted in SHrNTM SCID mice. One example is shown in Fig. 7E, and the growth profile of four such tumors in SHrNTM SCID mice is shown in Fig. 7F. Of additional significance, all tumors expressed HPV16 E6 and E7 as well as L1 and L2 proteins, as noted in the original tumor (Fig. 7G, lane 1) and in secondary tumors that developed in beige nude XID and athymic nude mice (Fig. 7G, lanes 2 and 3, respectively), thereby pointing to the HPV16 origin of the tumors. Histological evaluation of tertiary tumors revealed a monotonous population of cells with a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio and several mitotic figures (Fig. 7H). Thus, the growth characteristics of this tumor fulfilled all criteria for an aggressive HPV16-derived cancer in that it could be transplanted and retransplanted over two generations of mice and also retained expression of HPV16 oncogenes. Therefore, these studies showed that an 18-day-old HPV16-low folate-organotypic raft had the capacity to be transformed into a high grade malignant cancer within only 12 weeks, provided the host was severely immunodeficient. Taken together, these findings are consistent with the probability that folate deficiency functioned as a co-factor in HPV16-induced carcinogenesis.

FIGURE 7.

Transformation of an 18-day-old HPV16-low folate-organotypic raft into a malignant tumor within 12 weeks after subcutaneous implantation in a folate-replete beige nude XID mouse (A–D) and demonstration of highly aggressive growth characteristics and HPV16-derived protein expression in retransplanted tumors in immunodeficient mice (E–H). Due to prohibitive costs, this long term experiment involving the use of three species of mice with varying extents of immunodeficiency was conducted once; see “Experimental Procedures” and “Results” for details. A, photograph of a beige nude XID mouse at 12 weeks following the subcutaneous implantation of a fragment obtained from an HPV16-low folate-organotypic raft. After steadily increasing to 2 cm3 by the 14th week, the tumor rapidly enlarged to 10 cm3 in the ensuring 10 days, mandating euthanasia. There was no growth of HPV16-organotypic rafts propagated in either low folate or high folate among the other two species of athymic nude or SHrNTM SCID mice. B, histological section of the primary tumor from A stained with hematoxylin-eosin that highlights significant angiogenesis within a population of cells with a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, suggesting an underlying malignancy. Magnification was ×44. C and D, clumps of HPV16 viral particles within the primary tumor (C); the area in the blue square is further magnified to demonstrate the presence of 55-nm HPV16 viral particles (D). E, photograph of an aggressive tertiary tumor that developed within 2 weeks in an SHrNTM SCID mouse following the subcutaneous implantation of a small fragment from a secondary tumor that developed in an athymic nude mouse, which was earlier implanted with a fragment of the primary tumor in the beige nude XID mouse in A. F, determination of growth pattern of four tertiary tumors that developed in SHrNTM SCID mice. The data are plotted as tumor volume as a function of time following subcutaneous implantation. Error bars, S.D. G, Western blots to determine the presence of HPV16-specific proteins within the primary tumor in the beige nude XID mouse (lane 1) as well as from secondary tumors from another beige nude XID mouse (lane 2) and an athymic nude mouse (lane 3). Note the presence of HPV16 E6, E7, L1, and L2 proteins in all tumors. There was no signal using an unrelated antiserum (data not shown). H, histological section of a tertiary tumor stained with hematoxylin-eosin that highlights a monotonous population of malignant cells that exhibited a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, open chromatin, and several cells captured at various stages of replication. Magnification was ×100.

DISCUSSION

This report provides mechanistic insight into the functional consequences of linkage involving folate deficiency, homocysteine, hnRNP-E1, HPV16 RNA, HPV16 DNA integration into genomic DNA, and HPV16-induced cancer in mice. Although homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 bound to HPV16 L2 mRNA and decreased its translation in vitro (Fig. 1), this interaction could not entirely explain the observation of a very significant co-reduction of HPV16 L1 mRNA and protein that was identified in HPV16-harboring BC-1-Ep/SL-LF keratinocytes, which were stably propagated as monolayers in physiologically low folate medium (Fig. 2). However, the interaction of homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 with the HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(U)-rich cis-element in the upstream early polyadenylation element of the HPV16 genome (13) was an attractive possibility to explain this observation for three reasons. (i) Deletion of this domain, which is upstream of overlapping L2̂L1 genes in the HPV16 genome, reduced utilization of the HPV16 early polyadenylation signal, resulting in read-through into the HPV16 late region and increased production of L1 and L2 mRNAs (13); therefore, we reasoned that the binding of hnRNP-E1 to this region could reduce L2 and L1. (ii) This domain binds other members of the hnRNP family, including hFip1, CstF-64, hnRNP C1/C2, and polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (13). (iii) Earlier, we purified hnRNP-E1 using poly(U)-Sepharose affinity chromatography (9), suggesting that hnRNP-E1 would bind the HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(U)-rich cis-element. Subsequent studies on the binding of purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 to HPV16 57-nucleotide poly(U)-rich cis-element in the presence of physiological concentrations of l-homocysteine, as well as mutation studies involving this cis-element, indicated the specificity and importance of this interaction (Fig. 3). Subsequent CAT reporter studies (Fig. 4) predicted that a reduction in translation of the downstream sequences of HPV16 L2̂L1 mRNA following the interaction of HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element with homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 would negatively impact net protein levels in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells, which contain more homocysteine; this was experimentally demonstrated (Tables 2–4). Taken together, the dual interaction of homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 with HPV16 L2 mRNA and the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element was probably responsible for the reduced levels of HPV16 L2 and L1 mRNA and protein in (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-LF cells when compared with (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells (Fig. 2). Because there was a greater affinity of purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 for the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element than for HPV16 L2 mRNA, as well as a greater affinity of purified recombinant GST-hnRNP-E1 for the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element in the presence of l-homocysteine when compared with equimolar concentrations of l-cysteine (Table 1), it appears that the interaction of homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 with the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element in the upstream early polyadenylation element may be the more important physiological interaction within HPV16-harboring keratinocytes. The direct link involving l-homocysteine in inducing the binding of hnRNP-E1 to the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element was demonstrated by capture of these intracellular RNA-protein complexes as a function of the concentration of l-homocysteine added to (HPV16)BC-1-Ep/SL-HF cells (Fig. 3F). These studies required us to separate these complexes from other complexes that could also arise following the interaction of homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 with other mRNA cis-elements that share common poly(rC)- or poly(U)-rich sequence signatures, which also allows them to also bind to hnRNP-E1 under these conditions (7, 10, 25–34). Because hnRNP-E1 may have cross-linked some of these other mRNA (in addition to HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element) in cells containing higher than basal concentrations of l-homocysteine, we employed a similar strategy that was recently employed to detect folate receptor-α mRNA cis-element·hnRNP-E1 complexes (11). Accordingly, we tested equal amounts of small RNA fragments that were released from endogenous (immunoprecipitated) homocysteinylated hnRNP-E1 for the capacity to hybridize under stringent conditions with antisense probe to the HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element. Our results, which revealed progressively increased hybridization signals, clearly reflected the capture of HPV16 57-nucleotide RNA cis-element-bound hnRNP-E1 protein complexes within cells as a function of increasing intracellular l-homocysteine concentrations that mimicked various grades of physiological folate deficiency (Fig. 3F).