Abstract

Both females and individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) have been found to be at increased risk for a range of smoking outcomes, and recent empirical findings have suggested that women with ADHD may be particularly vulnerable to nicotine dependence. On a neurobiological level, the dopamine reward processing system may be implicated in the potentially unique interaction of nicotine with sex and with ADHD status. Specifically, nicotine appears to mitigate core ADHD symptoms through interaction with the dopamine reward processing system, and ovarian hormones have been found to interact with nicotine within the dopamine reward processing system to affect neurotransmitter release and functioning.

This article synthesizes data from research examining smoking in women and in individuals with ADHD to build an integrative model through which unique risk for cigarette smoking in women with ADHD can be systematically explored. Based upon this model, the following hypotheses are proposed at the intersection of each of the three variables of sex, ADHD, and smoking: 1) Individuals with ADHD have altered functioning of the dopamine reward system, which diminishes their ability to efficiently form conditioned associations based on environmental contingencies; these deficits are partially ameliorated by nicotine; 2) Nicotine interacts with estrogen and the dopamine reward system to increase the positive and negative reinforcement value of smoking in female smokers; 3) In adult females with ADHD, ovarian hormones interact with the dopamine reward system to exacerbate ADHD-related deficits in the capacity to form conditioned associations; and 4) During different phases of the menstrual cycle, nicotine and ovarian hormones may interact differentially with the dopamine reward processing system to affect the type and value of reinforcement smoking provides for women with ADHD.

Understanding the bio-behavioral mechanisms underlying cigarette addiction in specific populations will be critical to developing effectively tailored smoking prevention and cessation programs for these groups. Overall, the goal of this paper is to examine the interaction of sex, smoking, and ADHD status within the context of the dopamine reward processing system not only to elucidate potential mechanisms specific to female smokers with ADHD, but also to stimulate consideration of how the examination of such individual differences can inform our understanding of smoking more broadly.

Purpose and Organization

Despite extensive anti-smoking public health campaigns and the well-known adverse health effects of smoking, a substantial proportion of the population smokes cigarettes regularly [1]. Females and individuals with psychiatric illness are two subgroups of the population that are at increased risk for a range of smoking outcomes. For example, in developed countries such as the U.S., Canada, and the U.K., the number of female smoking-related deaths continues to rise rapidly despite a general decrease in smoking overall [2]; and data from the National Comorbidity Study indicated that odds ratios of current or past month smoking in individuals with mental illnesses is 2.7 when compared to those without mental illness [3]. In particular, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a risk factor for smoking [4–8]; even among non-clinical samples, ADHD symptoms are associated with cigarette smoking [9]. If public health efforts are to continue to be successful in reducing cigarette smoking, research must address those subgroups at highest risk including women and those with psychiatric illness.

The diverse actions of nicotine in the brain suggest that smoking may affect the symptoms of different mental illnesses through a variety of mechanisms [10, 11]. With respect to ADHD, nicotine appears to mitigate core symptoms through interaction with the dopamine reward processing system [12–16]. For women the relationship between ADHD and smoking may be unique, because ovarian hormones have been found to interact with nicotine within the reward processing system to affect dopamine release and functioning [17–22]. As such, sex and ADHD status may interact within the dopamine reward processing system to affect vulnerability to nicotine dependence.

This article will synthesize data from research examining smoking in women and individuals with ADHD to develop an integrative model through which unique risk for cigarette smoking in women with ADHD can be systematically explored. First, a working model based on the interaction of nicotine and ovarian hormones within the dopamine reward processing system will be presented. Then, supporting evidence for the model will be drawn from several areas of research including the behavioral and biological bases of ADHD and nicotine dependence, and the effects of ovarian hormones on drug use and reward-related associative learning. Because limited direct empirical data exists on the interaction of sex and ADHD on smoking outcomes, preliminary data from our laboratory will be presented. Finally, the paper will conclude with a more detailed representation of the following specific, model-driven hypotheses:

-

1)

With respect to ADHD and smoking: Individuals with ADHD have altered functioning of the dopamine reward system, which diminishes their ability to efficiently form conditioned associations based on environmental contingencies. These deficits are partially ameliorated by nicotine.

-

2)

With respect to sex and smoking: Nicotine interacts with estrogen and the dopamine reward system to increase the positive and negative reinforcement value of smoking in female smokers.

-

3)

With respect to sex and ADHD: In adult females with ADHD, ovarian hormones interact with the dopamine reward system to exacerbate ADHD-related deficits in the capacity to form conditioned associations.

-

4)

With respect to sex, ADHD, and smoking: During different phases of the menstrual cycle, nicotine and ovarian hormones may interact differentially with the dopamine reward processing system to affect the type and value of reinforcement smoking provides for women with ADHD.

Overall, the goal of this paper is to examine the interaction of sex, smoking, and ADHD status within the context of the dopamine reward processing system not only to elucidate potential mechanisms specific to female smokers with ADHD, but also to stimulate consideration of how the examination of such individual differences can inform our understanding of smoking more broadly.

The Interaction of Gender and ADHD on Addiction to Cigarettes: Introduction of the Integrative Model

The meso-limbic dopaminergic reward processing system is a key neural system in reward-processing and conditioned associative learning. It is central to the development of dependence on drugs including nicotine [23–26], and it has been extensively implicated in the pathophysiology of ADHD [27]. Accordingly, there is significant evidence to suggest that this system may underlie the high comorbidity of ADHD and nicotine dependence [9, 11, 12]. For example, diminished sensitivity to delayed reward and to changes in reward-related contingencies have been found to be associated with learning and motivational problems in ADHD [28, 29], and both nicotine and the stimulant medications used to treat ADHD act upon the dopamine system in ways that mitigate these problems [14, 27, 30].

For women, ovarian hormones play a major role in physical, social, and emotional development across the life span, and hormones are known to specifically influence the expression of psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, ADHD, and substance abuse including nicotine dependence [31–34]. Specific to ADHD, during prenatal development testosterone may interact with dopaminergic circuitry to delay maturation in brain areas related to cognitive control and reward processing, which, in turn, may contribute to the 3:1 ratio of males to females in childhood ADHD [34]. Upon sexual maturity, however, these sex differences in rates of ADHD equalize [35] and animal research suggests that in adulthood estrogen interacts with dopaminergic systems to more specifically impair conditioned learning in females with ADHD [36, 37].

With respect to smoking, a growing body of research in rats and non-human primates suggests that ovarian hormones play an important role in sex differences in nicotine dependence through their direct and indirect interactions with the dopamine reward processing system. For example, ovarian hormones modulate nicotine-induced dopamine release in the striatum, a key structure within this system [18]. In humans, there is evidence that cyclical changes in ovarian hormones over the course of the menstrual cycle alter sensitivity to the reinforcing effects of nicotine and other stimulants, also through complex interactions with this dopamine reward system [22, 31, 33, 38]. Taken together, these data suggest that the functioning of a dopamine reward processing system known to underlie critical learning and motivational deficits in ADHD is also affected by ovarian hormones. As such, nicotine may interact with ovarian hormones within the context of this dopamine system in ways that could uniquely impact the vulnerability of women with ADHD to nicotine dependence.

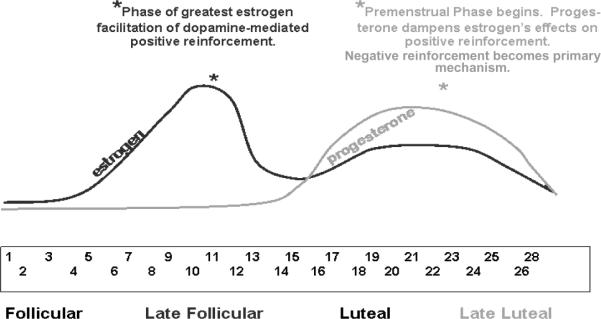

The model proposed here is based upon two mechanisms of the interaction of nicotine and ovarian hormones within the dopamine reward system in women with ADHD, each of which is hypothesized to become primary and to have specific effects at different phases of the menstrual cycle. As is pictorially depicted in Figure 1, during the pre-ovulatory or follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, estrogen is hypothesized to interact with nicotine in the context of the dopamine reward system in ways that improve reward-related learning, thereby ameliorating some of ADHD's key motivational/learning deficits. During this phase, estrogen and nicotine interact to enhance the positive reinforcement obtained from smoking in women with ADHD. During the pre-menstrual or luteal phase, negative reinforcement is hypothesized to become the primary mechanism maintaining cigarette addiction in women with ADHD. During this phase, progesterone levels rise, blocking the effects of estrogen on reward-related learning. As a result, nicotine exerts it primary effects by diminishing symptoms of cigarette withdrawal such as concentration difficulties, agitation, and mood lability. Because these symptoms may be indistinguishable (and possibility synergistic with) ADHD symptoms and nicotine withdrawal, the negative reinforcing effects of smoking is likely to be enhanced in female smokers with ADHD during this menstrual cycle phase.

Figure 1. Positive and Negative Reinforcement of Smoking During the Menstrual Cycle.

During the follicular phase, increasing estrogen levels facilitate dopamine-mediated positive reinforcement. During this stage, it is predicted that female smokers with ADHD will report the greatest positive reinforcement from smoking. During the late luteal/pre-menstrual phase, the effects of estrogen on positive reinforcement are dampened by progesterone, and withdrawal symptoms are difficult to distinguish from ADHD and premenstrual symptoms. During this stage, it is predicted that female smokers with ADHD will report the greatest negative reinforcement from smoking.

To support this model of how ovarian hormones during different stages of the menstrual cycle, nicotine, and ADHD status may interact to affect individual differences in smoking-related reinforcement, in the next section we will turn to a review of the relevant published literature. First, we will examine the basics of the dopamine reward processing system, specifically discussing its role in learning and its basic biological mechanisms. Second, we will examine the ways in which this dopaminergic system underlies positive and negative reinforcement in ADHD and smoking. Finally, we will discuss the interaction of ovarian hormones and nicotine within the dopamine reward system.

Review of Background Literature

The Functioning of the Dopamine Reward Processing System

The dopamine system and learning

Central to the proposed model is the mesolimbic reward processing system, a dopaminergic circuit that involves cortical and subcortical brain structures underlying detection, processing, and responding to rewarding stimuli [27, 39–52]. Alterations in the functioning of this system are associated with motivational and learning deficits in ADHD, as well as in the development and maintenance of addiction to nicotine and other drugs [27, 53, 54].

Dopamine's action within this circuit underlies the process of developing conditioned associations, or learning the connection between specific stimuli and contingent outcomes. The efficient development of conditioned associations between environmental stimuli and rewarding outcomes is fundamental to both learning and motivation. All purposeful behavior is directed toward maximizing reward and minimizing punishment, and learning which stimuli and actions are associated with pleasurable outcomes is the basis of behavior to improve the chances of obtaining reward [46].

In ADHD, the functioning of the dopamine reward system is disrupted such that there is diminished sensitivity to delayed rewarding contingencies and to contingency changes over time. As a result, individuals with ADHD have particular difficulty learning associations between behavior and the potential for longer-term reward [27–29, 55]. The unique actions of nicotine are hypothesized to normalize some of the deficiencies in associative learning in ADHD, thus making smoking particularly reinforcing to individuals with the disorder [9, 11, 27].

The basic biological mechanisms of the dopamine reward system

Brain structures involved in mesolimbic reward processing system include the ventral tegmental area (VTA), striatum, nucleus accumbens, anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). Dopamine cell bodies concentrated in the VTA project throughout this circuit [45, 46].

Within the mesolimbic dopamine reward processing system, dopamine neurons normally fire at a low, tonic rate. Changes in the rate and activation level of dopamine firing result in conditioned associations [44–46, 56]. This process takes place through at least three interacting mechanisms.

First, in the presence of unexpected or larger-than-expected reward, dopamine cells switch from their baseline tonic firing rate to a phasic rate of firing. In this way, phasic firing of dopamine acts as an “alerting signal” for the presence of potential reward. After an organism learns to expect a reward in association with a particular stimulus, phasic dopamine release shifts and begins firing in association with the first stimulus predicting delivery of the reward. In other words, the dopamine signal changes from a “reward alerting signal” to a “reward predicting signal” [41–47, 51, 57–59]. Thus, dopamine firing rates within the mesolimbic reward processing circuit underlie the mechanism by which an organism associates specific stimuli with the presence and value of potential reward or reinforcement.

A second mechanism by which dopamine facilitates the development of stimulus - reward associations is by modulating neuronal plasticity and enhancing long term potentiation (LTP) in the striatum, thereby increasing the chances that learning will take place. Specifically, if dopamine is released in the striatum coincidentally with synaptic firing in response to environmental stimuli, then the environmental stimuli will have a higher likelihood becoming associated. However, if the timing of dopamine release in the striatum is not synchronized with the presentation of contingent stimuli, no such association will be made [44, 49, 60–63].

A third mechanism by which dopamine is related to conditioned associations is through dopaminergic projections from the VTA to the cortex that also facilitate cortical remodeling: stimulation of the VTA in the presence of a stimulus increases cortical activity and selectivity in brain areas relevant to that stimulus, while simultaneously dampening cortical activity in brain areas associated with other similar but irrelevant stimuli [56]. Dopamine release is also depressed in this area by the absence of an expected reward, suggesting that the dopamine signal is similarly involved in suppressing associations when an anticipated reward is not forthcoming [45, 46]. Thus, dopamine is central not only in the formation of conditioned associations in general, but it is also critical to learning the conditions in which a potential reward will or will not be available.

In summary, phasic dopamine release within the dopaminergic reward processing system underlies a fundamental component of reinforcement-based learning by providing a critical alerting signal to the presence of appetitive motivational stimuli, and by enhancing synaptic plasticity and cortical restructuring in ways that allow for specificity in the association of environmental contingencies [45, 46, 49, 56, 58, 62, 63].

The Dopamine Reward System: Positive and Negative Reinforcement in ADHD and Smoking

In ADHD, the functioning of key brain structures within the dopamine reward system have been found to be underactive during reward-related learning tasks [29, 55, 64–77]. This suggests that suboptimal dopaminergic signaling may underlie specific deficits in motivation and learning of conditioned associations in ADHD. As a result, individuals with ADHD may require larger, more immediate, and more salient rewards in order to sufficiently activate the dopamine reward system to enable the formation of relevant conditioned associations [28, 29]. Consistent with this, adults with ADHD are more responsive to immediate rewards when compared to adults without ADHD [78].

The standard of care for ADHD is stimulant medication, and methylphenidate has been found to normalize contingency-based responding in individuals with ADHD [30, 79]. It is believed that methylphenidate and other stimulant medications address ADHD symptoms by altering phasic dopamine release [48, 55, 80, 81]. Nicotine, like stimulants, increases the saliency of natural stimuli by altering dopamine release and reuptake in the mesolimbic dopaminergic reward system [23–25, 82–89]. As a result, individuals with ADHD may be particularly vulnerable to nicotine addiction because its stimulant properties operate via mechanisms similar to those of the medications used to treat ADHD [11, 12, 90, 91]. In fact, there is significant evidence that nicotine is effective in ameliorating not only cognitive and behavioral symptoms associated with ADHD, but that it may also be a potential therapeutic agent in the treatment of other dopamine-related neuro-cognitive disorders such as Parkinson's Disease [10, 14, 15].

As discussed above, evidence suggests that individuals with ADHD may be less sensitive to delayed rewarding contingencies than those without the disorder. Abstinent smokers may also be broadly less sensitive to reinforcement, and there is some evidence that smokers may use nicotine to enhance the incentive value of environmental stimuli [89, 92–94]. Testing an “incentive motivational model” of smoking based on the assumption of impaired mesocorticolimbic functioning during smoking abstinence, researchers examined the performance of abstinent smokers, satiated smokers, and non-smokers on an incentivized card-sorting task wherein participants could earn money for quick and accurate sorting. Results demonstrated that abstinent smokers had diminished performance for monetary reinforcement when compared to both satiated smokers and to non-smokers. However, when no monetary incentive was available, abstinent smokers, satiated smokers, and non-smokers performed equally. This suggests that during abstinence smokers perform less efficiently only in situations of potential reward, and that these differences in reward-related performance disappear with nicotine administration. The findings based on self-report measures of state-dependent hedonic tone mirrored these behavioral findings: Abstinent smokers reported diminished expectation of enjoyment on a range of non-drug related pleasurable events that paralleled their diminished performance on the incentivized card-sorting task [89]. Researchers concluded that craving may involve two distinct components – one (negatively reinforced) facet related to nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and one (positively reinforced) facet related to a more “positive, appetitive state” ([89] p. 160). The findings also suggest that, at least during abstinence, smokers objectively demonstrate less motivation to earn a reinforcer and subjectively assess natural reinforcers as having less value than satiated smokers or nonsmokers.

The behavioral evidence that smoking is associated with alterations to mesolimbocortical dopamine reward processing is supported by imaging research: Administration of nicotine/smoking is associated with increased neuronal activity in reward-related brain regions including the ventral tegmentum, nucleus accumbens, and ventral striatum [92, 94]. Further, compared to non-smokers, smokers have been found to demonstrate greater increases in brain metabolism when presented with smoking (vs. neutral) cues in areas associated with reward-processing, including the orbitofrontal cortex and the ventral striatum [93, 95]. Thus, like individuals with ADHD, smokers may experience increased saliency of naturally rewarding stimuli upon self-administration of nicotine.

The Dopamine System, Ovarian Hormones, and Nicotine

Ovarian hormones interact with almost every system in the body, including the mesolimbic dopamine system [17, 18, 96–101]. Throughout development, ovarian hormones influence dopamine function in a variety of ways, including dopamine release, receptor density, and transporter number, and the regulation of nicotinic receptors with chronic nicotine administration [18–20, 96, 102]. There is significant evidence that estrogen-induced increases in dopamine activity serve to enhance the reinforcing value of environmental stimuli and to facilitate the development of conditioned associations, and that progesterone dampens estrogen's effects [18, 21, 33, 96–111]. Such hormonal regulation of dopamine function takes place within a complex and dynamic system. For example, estrogen receptors exert differential effects on dopamine function across the menstrual cycle [22, 38, 96, 102, 103].

The action of ovarian hormones within the dopamine reward system may be particularly relevant in the case of nicotine dependence [18, 22, 31, 38, 108]. Specifically, ovarian hormones are known to effect the regulation of nicotinic receptors with chronic nicotine administration, to increase nicotinic receptors in the dorsal raphe nucleus and the locus coeruleus, and to facilitate dopamine receptor binding and dopamine release [17–20, 112]. In sum, ovarian hormones directly and indirectly interact with the mesolimbic dopaminergic reward system to powerfully influence the reinforcing effects of smoking.

Menstrual cycle effects on smoking: The follicular and luteal phases

During the human menstrual cycle, estrogen levels peak twice. The highest estrogen peak is during the follicular phase; a second, smaller peak occurs during the luteal phase. Progesterone levels, on the other hand, remain low throughout the follicular phase and peak during the luteal phase [31, 113]. The majority of research examining the effects of menstrual phase on smoking behavior in humans has compared withdrawal symptoms and smoking cessation attempts between the follicular and luteal phases [114–123]. For the most part, findings suggest that women report greater symptoms of withdrawal, more negative affect, and have more difficulty quitting smoking during the luteal phase than during the follicular phase, and that nicotine replacement is more effective in reducing craving during the luteal phase [31].

However, several recent studies found that during ad libitum smoking women reported greater craving upon awakening [124] but had lower rates of smoking during the day [125] in the follicular than in the luteal/menstrual phases. Further, some studies have found that the majority of women who attempted to quit during the follicular phase were less successful than those attempting to quit during the luteal phase [114, 126], though women who smoked more during the luteal phase were marginally more likely to relapse during that phase [127]. These inconsistent findings with respect to craving, withdrawal, and quit attempts during the follicular and luteal phases may suggest that different mechanisms are at work in maintaining smoking over the course of the menstrual cycle [128]. Drawing upon the stimulant literature, some investigators have suggested that for many women higher levels of estrogen during the follicular phase may serve to improve mood generally, and to enhance the subjective value of nicotine specifically. During the luteal phase, however, premenstrual symptoms and symptoms of nicotine withdrawal are difficult to distinguish [31, 115], and therefore women who rely more on nicotine to cope with premenstrual symptomatology may be particularly challenged during that phase of their cycle [127, 128].

Positive reinforcement and the follicular phase

Although there is limited human subjects research designed to disentangle the effects of estrogen and progesterone on cigarette self-administration or on subjective smoking reinforcement, research with cocaine and amphetamine in humans has found that the women report greater positive subjective effects of both substances during the follicular than the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle [129]. Moreover, men report greater positive subjective effects of stimulants compared to women who are in the luteal phase, though these gender differences disappear during the follicular phase [104, 130, 131]. Some [130, 131] but not all [132] research has found plasma or salivary estrogen levels to be associated positively with subjective response to amphetamine, and one study found that exogenously administered estrogen enhanced the discriminative stimulus effects of low doses of amphetamine [106]. Exogenously administered progesterone, on the other hand, has been found to attenuate the subjective response to cocaine in women but not in men [105], and to attenuate the subjective response to nicotine in both genders [133]. Taken together, these data suggest that during the follicular phase when estrogen levels are high and progesterone levels are relatively low, stimulants including nicotine may be experienced as more rewarding and therefore as a more powerful positive reinforcer of smoking.

Though there is limited research regarding gender differences in ADHD in adults (Barkley, Murphy, & Fischer, 2008), animal models suggest that hormonally-related sex differences may be particularly relevant to the potentially positive reinforcing effects of nicotine in adult females with ADHD during the follicular phase. Most research examining mechanisms in sex differences in adults with ADHD has been undertaken using the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR), an established animal model of ADHD [36, 37, 74, 75, 134, 135]. Findings have provided some provocative evidence of neurobiological mechanisms of sex-differences in the disorder. Specifically, sexually mature females SHR rats appear to demonstrate greater behavioral problems and more impulsivity than do male SHR rats [136]. Also, mature female SHR rats have greater difficulty with extinction learning [135]; have more difficulty learning conditioned associations; and require more trials to learn to respond to a discriminative stimulus [37] than mature male SHR rats. Interestingly, one study found that estrogen impairs conditioned associations in male and female adult SHR rats but not in the actively normal control strain of Wistar rats [36, 37].

Though limitations to the SHR model of ADHD temper the conclusions that can be drawn from these studies [137], the findings suggest that, at least after puberty, females with ADHD are more likely to demonstrate impairment with respect to conditioned learning and extinction than males with the disorder, and that this may be associated with the presence of ovarian hormones. Because nicotine affects neurobiological mechanisms that facilitate conditioned learning, it may be that sex-specific impairments in ADHD interact with nicotine's biological effects to make women with the disorder particularly vulnerable to cigarette addiction.

Negative reinforcement and luteal phase

The majority of smoking cessation research has examined the effects of withdrawal from nicotine during quit attempts. As such, the focus has been primarily on the negative reinforcement of smoking that comes from the amelioration of nicotine withdrawal [138–140]. Based on this research, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) has become a primary approach to smoking cessation treatment.

In individuals with ADHD, negative reinforcement is likely to play a particularly salient role in maintaining smoking. First, nicotine withdrawal symptoms and ADHD symptoms overlap in that both are characterized by problems with concentration, agitation, mood lability, and irritability. When a smoker with ADHD experiences smoking withdrawal, the symptoms are likely to be particularly impairing if they are compounding pre-existing symptoms of the disorder. In fact, smokers with ADHD have been found to demonstrate even greater decrements in attentional functioning during smoking abstinence than smokers without ADHD [141, 142]. Second, nicotine has been found to improve attentional functioning in non-smokers with and without ADHD [14, 15], and nicotine has even been considered as an alternative treatment to methylphenidate and other stimulant medications in the treatment of the disorder [14]. If individuals with ADHD are using nicotine to treat symptoms of the disorder, then during acute smoking abstinence they will not only experience cognitive effects from nicotine withdrawal, but they will also feel the full impact of their original ADHD symptoms. In addition, the full impact of these ADHD symptoms will remain beyond the period of acute abstinence if they do not receive alternative treatment, leaving ADHD smokers more vulnerable to relapse.

Further, during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, women experience premenstrual symptoms that mirror symptoms of nicotine withdrawal and symptoms of ADHD, including mood lability, depressed mood, irritability, restlessness, and increased appetite. Several studies have demonstrated that women: 1) experienced greater nicotine withdrawal and premenstrual symptoms during the luteal phase; 2) had difficulty distinguishing premenstrual from nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and; 3) had less favorable outcomes when attempting to quit smoking during the luteal phase than during the follicular phase [21, 31, 114, 117, 119, 121, 127, 143]. As such, women with ADHD may be vulnerable to a “triple threat” when trying to quit smoking during the luteal phase, in that they would experience the combination of premenstrual symptoms, nicotine withdrawal, and increased symptomatology of ADHD. Taken together, this suggests that smoking to obtain the negative reinforcement of relief from the symptoms may be particularly compelling to women with ADHD during the luteal phase.

In sum, the effect of smoking may vary in women with ADHD as a function of ovarian hormone exposure during different phases of the menstrual cycle. In the next section, we will present some empirical support for the proposed model based on preliminary data collected in our laboratory.

Preliminary Empirical Support for the Integrative Model

Our interest in potential hormonal mechanisms underlying an association among sex, ADHD, and nicotine dependence was stimulated by unexpected but robust findings of interaction effects between gender and ADHD status on smoking outcomes across several of our own studies [144–146]. Our laboratory investigates differences between smokers with and without ADHD on a number of smoking-related variables and smoking outcomes. We have consistently found that smokers with ADHD report greater cognitive and affective benefit from smoking, and have worse outcomes in efforts to stop smoking, than non-ADHD smokers. Until recently, however, we had no a priori expectation that sex differences would significantly impact on our findings.

Our first evidence that sex might moderate group differences were findings from a small, preliminary investigation of differences in cognitive and other variables between smokers with and without ADHD. As we predicted, we observed that after short term smoking abstinence smokers with ADHD showed greater decrements in measures of attention and response inhibition than did smokers without ADHD. However, we also found that the female smokers with ADHD showed significantly greater abstinence-induced deficits on these variables than any of the other groups, including males with ADHD. In fact, to our surprise it appeared that the group differences between ADHD and non-ADHD smokers were driven almost entirely by the female ADHD smokers [141].

These findings led us to more carefully examine sex effects in follow-up studies. In a study of 22 smokers with and 22 smokers without ADHD, we found that at baseline women with ADHD reported the highest level of smoking-related ratings of “improved concentration” and “reduced irritability” among all of the groups. They also reported significantly greater craving at baseline and throughout 12-days of abstinence than did non-ADHD females, ADHD-males, and non-ADHD males [144]. Finally, in two large-scale (N=390) smoking cessation trials where self-reports of ADHD symptoms were examined at baseline, chi-square analyses revealed that female smokers with high levels of self-reported ADHD symptoms lapsed significantly faster than females with low levels of ADHD symptoms, males with high levels of ADHD symptoms, or males with low levels of ADHD symptoms [146]. Taken together, these data led us to hypothesize that female smokers with ADHD may be distinguishable from male smokers with and without ADHD, and from female non-ADHD smokers, across a variety of smoking outcomes. Specifically, the data support the proposed integrative model because they suggest that compared to men with ADHD, women with ADHD may be uniquely vulnerable to both the positive reinforcing effects of smoking (in that they reported greater smoking-related improvements in concentration and mood even during baseline) and the negative reinforcing effects of smoking (because they experience greater deficits in attention and response inhibition, greater craving, and faster relapse during smoking abstinence). These findings were observed even though menstrual cycle phase was uncontrolled; the proposed model would predict that the effects would be even more pronounced were cycle phase taken into account.

Conclusion and Restatement of Hypotheses

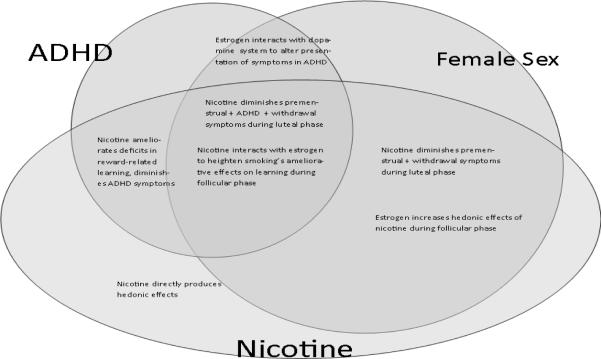

Figure 2 summaries key concepts form previous sections, and presents a pictorial representation of the originally-stated hypotheses. First, the overlapping ovals of ADHD and nicotine represent Hypothesis 1, reflecting that both people with ADHD and nicotine dependent individuals have diminished sensitivity to delayed environmental contingencies secondary to altered functioning of the mesolimbic dopaminergic reward system, and that nicotine administration ameliorates these deficits in both groups [10, 13, 14, 23, 54, 83, 147–150]. Second, Hypothesis 2 is represented by the overlapping ovals of female sex and nicotine, reflecting that nicotine may have unique affects in adult females by interacting with estrogen and the dopamine reward system in ways that increase both the positive and the negative reinforcement afforded by smoking [21, 31, 104, 106, 114, 117, 119, 121, 129–132, 143]. Third, the overlapping ovals of female sex and ADHD represent Hypothesis 3, indicating that ovarian hormones may act within the dopamine reward system to exacerbate deficits in the capacity to form conditioned associations, thereby worsening attentional and response inhibition deficits of ADHD [36, 37, 135, 136]. Finally, all three ovals overlap to represent Hypothesis 4, reflecting the two hypothesized mechanisms by which sex, ADHD, and nicotine may interact over the course of the menstrual cycle: 1) during the follicular phase, estrogen may interact with nicotine within the dopamine reward system to ameliorate ADHD-related conditioned learning deficits that are particularly pronounced with females with the disorder; and 2) during the luteal phase, nicotine may diminish the compounded discomfort of premenstrual symptoms, nicotine withdrawal, and ADHD symptoms. As such, women with ADHD may be particularly vulnerable to addiction to nicotine via mechanisms unique both to their sex and to their ADHD status.

Figure 2.

Summary of the interaction of ADHD, Female Sex, and Nicotine

Limitations and Future Research Implications

The model presented here offers a heuristic organization of the overlapping research in ADHD, gender, and nicotine dependence, and provides a possible explanation for the observations of the robust gender effects in our studies evaluating the association between ADHD and smoking outcomes. It is important to keep in mind that this is a working integrative model, open to alterations and adjustments as the relationship between ADHD and gender in nicotine dependence is explored in greater depth. The overlaps of any two of the three elements of ADHD status, sex, and nicotine effects are far from being thoroughly understood, and the impact of gender and hormones on ADHD outcomes is particularly unclear [34]. More research is warranted on how ovarian hormones interact with the neurobiological mechanisms of ADHD to affect the rate and presentation of inattentive and hyperactive symptoms in females in both childhood and adulthood. Though there is a clear association between nicotine dependence and ADHD diagnosis, the mechanisms of this relationship are still poorly understood and effective interventions for individuals with this comorbidity are still lacking. Finally, the impact of ovarian hormones on sensitivity to cigarette reinforcement in women has received little research attention. This is a particularly important area for future research given that an understanding of the neurobehavioral mechanisms of gender differences in smoking outcomes is critical to the development of targeted interventions for female smokers both with and without comorbid psychopathology.

From a broader perspective, however, an understanding of the interaction of ADHD with nicotine dependence in women can both draw from and contribute to the exploration of other forms of psychopathology and gender in smoking. For example, recent research has suggested that sex and depression may interact to impact smoking outcomes in women [151, 152]. Given that the dopamine system is thought to interact with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system to produce gender effects on depression outcomes and smoking [124, 153], researchers interested in the interaction of psychopathology and cigarette addiction in women more generally may benefit from a broader model through which to communicate and compare their findings.

The model presented in this review suggests potentially fruitful empirical studies of treatment applications for women with ADHD who are trying to quit smoking. As with men, tapered nicotine replacement therapy will continue to be a key component of any smoking cessation program. However, the model would also suggest that women with ADHD might be more successful quitting smoking if they were to begin their cessation attempts during the follicular phase, and if the positively reinforcing, ameliorative effects of smoking on their ADHD symptoms were replaced by the use of stimulant medication. Finally, the model suggests that during the luteal phase, women would benefit from not only careful attention to the need for nicotine replacement, but also from specific attention to the treatment of premenstrual symptomatology as well.

In conclusion, this examination of the intersection of nicotine dependence, ADHD, and gender has suggested that seeking to understand the complex relationship among these variables may hold possibilities for benefitting women with comorbid ADHD and cigarette addiction, as well as for more broadly contributing to knowledge of the neurobehavioral underpinnings of comorbid nicotine dependence and psychopathology. It is hoped that this discussion will stimulate further targeted research toward improving smoking outcomes for those who continue to struggle with this significant public health problem.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by the “Office of Research and Development Clinical Science and by the Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs”. This work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health 1R03DA029752 to EEV; K24DA023464 and R21DA020806 to SHK; K23DA017261 to FJM; and 5K24DA016388, 5R01MH062482, 5R01CA081595 to JCB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cigarette package health warnings and interest in quitting smoking --- 14 countries, 2008--2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011:645–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field C. Examining factors that influence the uptake of smoking in women. Br J Nurs. 2008;17(15):980–5. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.15.30703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lasser K, et al. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2606–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuemmeler BF, Kollins SH, McClernon FJ. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms predict nicotine dependence and progression to regular smoking from adolescence to young adulthood. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(10):1203–13. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClernon FJ, et al. Interactions between genotype and retrospective ADHD symptoms predict lifetime smoking risk in a sample of young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(1):117–27. doi: 10.1080/14622200701704913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milberger S, et al. ADHD is associated with early initiation of cigarette smoking in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(1):37–44. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199701000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pomerleau CS, et al. Smoking patterns and abstinence effects in smokers with no ADHD, childhood ADHD, and adult ADHD symptomatology. Addict Behav. 2003;28(6):1149–57. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilens TE, et al. Cigarette smoking associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr. 2008;153(3):414–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kollins SH, McClernon FJ, Fuemmeler BF. Association between smoking and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in a population-based sample of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1142–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin ED, McClernon FJ, Rezvani AH. Nicotinic effects on cognitive function: behavioral characterization, pharmacological specification, and anatomic localization. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184(3–4):523–39. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClernon FJ, Kollins SH. ADHD and smoking: from genes to brain to behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141:131–47. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gehricke JG, et al. The reinforcing effects of nicotine and stimulant medication in the everyday lives of adult smokers with ADHD: A preliminary examination. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(1):37–47. doi: 10.1080/14622200500431619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin ED, et al. Transdermal nicotine effects on attention. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;140(2):135–41. doi: 10.1007/s002130050750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levin ED, et al. Nicotine effects on adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;123(1):55–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02246281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poltavski DV, Petros T. Effects of transdermal nicotine on attention in adult non-smokers with and without attentional deficits. Physiol Behav. 2006;87(3):614–24. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potter AS, Newhouse PA. Acute nicotine improves cognitive deficits in young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;88(4):407–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centeno ML, et al. Estradiol increases alpha7 nicotinic receptor in serotonergic dorsal raphe and noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons of macaques. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497(3):489–501. doi: 10.1002/cne.21026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dluzen DE, Anderson LI. Estrogen differentially modulates nicotine-evoked dopamine release from the striatum of male and female rats. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;230:140–142. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00487-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koylu E, et al. Sex difference in up-regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat brain. Life Sci. 1997;61(12):PL 185–90. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00665-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mochizuki T, et al. Nicotine induced up-regulation of nicotinic receptors in CD-1 mice demonstrated with an in vivo radiotracer: gender differences. Synapse. 1998;30(1):116–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199809)30:1<116::AID-SYN15>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pauly JR. Gender differences in tobacco smoking dynamics and the neuropharmacological actions of nicotine. Front Biosci. 2008;13:505–16. doi: 10.2741/2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pogun S, Yararbas G. Sex differences in nicotine action. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;(192):261–91. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balfour DJ. The neurobiology of tobacco dependence: a preclinical perspective on the role of the dopamine projections to the nucleus accumbens [corrected] Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(6):899–912. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331324965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balfour DJ, et al. The putative role of extra-synaptic mesolimbic dopamine in the neurobiology of nicotine dependence. Behav Brain Res. 2000;113(1–2):73–83. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fehr C, et al. Association of low striatal dopamine d2 receptor availability with nicotine dependence similar to that seen with other drugs of abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):507–14. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nestler EJ. Is there a common molecular pathway for addiction? Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1445–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volkow ND, et al. Evaluating dopamine reward pathway in ADHD: clinical implications. JAMA. 2009;302(10):1084–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luman M, Oosterlaan J, Sergeant JA. The impact of reinforcement contingencies on AD/HD: a review and theoretical appraisal. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(2):183–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luman M, Tripp G, Scheres A. Identifying the neurobiology of altered reinforcement sensitivity in ADHD: A review and research agenda. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray LK, Kollins SH. Effects of methylphenidate on sensitivity to reinforcement in children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: an application of the matching law. J Appl Behav Anal. 2000;33(4):573–91. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carpenter MJ, et al. Menstrual cycle phase effects on nicotine withdrawal and cigarette craving: a review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(5):627–38. doi: 10.1080/14622200600910793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensvold MF, Halbreich U, Hamilton JA, editors. Psychopharmacology and Women: Sex, Gender, and Hormones. American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; Washington, D.C.: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynch WJ. Sex differences in vulnerability to drug self-administration. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14(1):34–41. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martel MM, et al. Potential hormonal mechanisms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder: A new perspective. Horm Behav. 2009;55(4):465–79. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Fischer M. ADHD In Adults: What the Science Says. The Guilford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bucci DJ, et al. Effects of sex hormones on associative learning in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Physiol Behav. 2008;93(3):651–7. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bucci DJ, et al. Sex differences in learning and inhibition in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187(1):27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perkins KA, Donny E, Caggiula AR. Sex differences in nicotine effects and self-administration: review of human and animal evidence. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(4):301–15. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berridge KC, Robinson TE. What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;28(3):309–69. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frank MJ, et al. Genetic triple dissociation reveals multiple roles for dopamine in reinforcement learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(41):16311–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706111104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haber SN, et al. Reward-related cortical inputs define a large striatal region in primates that interface with associative cortical connections, providing a substrate for incentive-based learning. J Neurosci. 2006;26(32):8368–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0271-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pessiglione M, et al. Dopamine-dependent prediction errors underpin reward-seeking behaviour in humans. Nature. 2006;442(7106):1042–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Neurobehavioural mechanisms of reward and motivation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6(2):228–36. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schonberg T, et al. Reinforcement learning signals in the human striatum distinguish learners from nonlearners during reward-based decision making. J Neurosci. 2007;27(47):12860–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2496-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schultz W. Getting formal with dopamine and reward. Neuron. 2002;36(2):241–63. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schultz W. Behavioral theories and the neurophysiology of reward. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:87–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275(5306):1593–9. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Volkow ND, et al. Evidence that methylphenidate enhances the saliency of a mathematical task by increasing dopamine in the human brain. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(7):1173–80. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wickens JR, et al. Striatal contributions to reward and decision making: making sense of regional variations in a reiterated processing matrix. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1104:192–212. doi: 10.1196/annals.1390.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wickens JR, Reynolds JN, Hyland BI. Neural mechanisms of reward-related motor learning. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13(6):685–90. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wightman RM, Robinson DL. Transient changes in mesolimbic dopamine and their association with 'reward'. J Neurochem. 2002;82(4):721–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yacubian J, et al. Dissociable systems for gain- and loss-related value predictions and errors of prediction in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2006;26(37):9530–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2915-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Drug addiction: bad habits add up. Nature. 1999;398(6728):567–70. doi: 10.1038/19208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sagvolden T, et al. A dynamic developmental theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) predominantly hyperactive/impulsive and combined subtypes. Behav Brain Sci. 2005;28(3):397–419. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000075. discussion 419–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Solanto MV. Dopamine dysfunction in AD/HD: integrating clinical and basic neuroscience research. Behav Brain Res. 2002;130(1–2):65–71. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bao S, Chan VT, Merzenich MM. Cortical remodelling induced by activity of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons. Nature. 2001;412(6842):79–83. doi: 10.1038/35083586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hikosaka O, et al. New insights on the subcortical representation of reward. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18(2):203–8. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knutson B, Gibbs SE. Linking nucleus accumbens dopamine and blood oxygenation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191(3):813–22. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0686-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roesch MR, Calu DJ, Schoenbaum G. Dopamine neurons encode the better option in rats deciding between differently delayed or sized rewards. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(12):1615–24. doi: 10.1038/nn2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Calabresi P, et al. Dopamine-mediated regulation of corticostriatal synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(5):211–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wickens JR. Synaptic plasticity in the basal ganglia. Behav Brain Res. 2009;199(1):119–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reynolds JN, Wickens JR. Dopamine-dependent plasticity of corticostriatal synapses. Neural Netw. 2002;15(4–6):507–21. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(02)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arbuthnott GW, Ingham CA, Wickens JR. Dopamine and synaptic plasticity in the neostriatum. J Anat. 2000;196(Pt 4):587–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19640587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Booth JR, et al. Larger deficits in brain networks for response inhibition than for visual selective attention in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(1):94–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bush G, et al. Anterior cingulate cortex dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder revealed by fMRI and the Counting Stroop. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45(12):1542–52. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bush G, Valera EM, Seidman LJ. Functional neuroimaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review and suggested future directions. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1273–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Casey BJ, et al. Frontostriatal connectivity and its role in cognitive control in parent-child dyads with ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1729–36. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Castellanos FX, et al. Cingulate-precuneus interactions: a new locus of dysfunction in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(3):332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dickstein SG, et al. The neural correlates of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: an ALE meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(10):1051–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Durston S, et al. Dopamine transporter genotype conveys familial risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder through striatal activation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):61–7. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a5f17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Durston S, et al. Activation in ventral prefrontal cortex is sensitive to genetic vulnerability for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(10):1062–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Durston S, et al. Differential patterns of striatal activation in young children with and without ADHD. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(10):871–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01904-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ernst M, et al. Neural substrates of decision making in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1061–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Russell V, et al. Altered dopaminergic function in the prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens and caudate-putamen of an animal model of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder--the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Brain Res. 1995;676(2):343–51. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00135-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Russell VA. Hypodopaminergic and hypernoradrenergic activity in prefrontal cortex slices of an animal model for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder--the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Behav Brain Res. 2002;130(1–2):191–6. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scheres A, et al. Ventral striatal hyporesponsiveness during reward anticipation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(5):720–4. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tripp G, Wickens JR. Research review: dopamine transfer deficit: a neurobiological theory of altered reinforcement mechanisms in ADHD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(7):691–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mitchell JT, et al. An evaluation of behavioral approach in adult ADHD. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tripp G, Alsop B. Sensitivity to reward frequency in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28(3):366–75. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Volkow ND, et al. Role of dopamine in the therapeutic and reinforcing effects of methylphenidate in humans: results from imaging studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;12(6):557–66. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Volkow ND, et al. Mechanism of action of methylphenidate: insights from PET imaging studies. J Atten Disord. 2002;6(Suppl 1):S31–43. doi: 10.1177/070674370200601s05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Raiff BR, Dallery J. The generality of nicotine as a reinforcer enhancer in rats: Effects on responding maintained by primary and conditioned reinforcers and resistance to extinction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;201:304–314. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Corrigall WA, Coen KM, Adamson KL. Self-administered nicotine activates the mesolimbic dopamine system through the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res. 1994;653(1–2):278–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Emdad R, Sondergaard HP. Visuoconstructional ability in PTSD patients compared to a control group with the same ethnic background. Stress and Health. 2006;22:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Exley R, et al. alpha6-Containing Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Dominate the Nicotine Control of Dopamine Neurotransmission in Nucleus Accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(9):2158–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Exley R, Cragg SJ. Presynaptic nicotinic receptors: a dynamic and diverse cholinergic filter of striatal dopamine neurotransmission. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S283–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mansvelder HD, et al. Cholinergic modulation of dopaminergic reward areas: upstream and downstream targets of nicotine addiction. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;480(1–3):117–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pich EM, et al. Common neural substrates for the addictive properties of nicotine and cocaine. Science. 1997;275(5296):83–6. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Powell J, Dawkins L, Davis RE. Smoking, reward responsiveness, and response inhibition: Tests of an incentive motivational model. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:151–163. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gehricke JG, et al. Smoking to self-medicate attentional and emotional dysfunctions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(Suppl 4):S523–36. doi: 10.1080/14622200701685039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Reichel CM, Linkugel JD, Bevins RA. Nicotine as a conditioned stimulus: impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15(5):501–9. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brody AL. Functional brain imaging of tobacco use and dependence. Journal of Psychiatry Research. 2006;40:404–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McClernon FJ, et al. Abstinence-induced changes in self-report craving correlate with event-related FMRI responses to smoking cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(10):1940–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stein EA, et al. Nicotine-induced limbic cortical activation in the human brain: A functional MRI study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(8):1009–1015. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brody AL, et al. Brain metabolic changes during cigarette craving. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1162–1172. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Farage MA, Osborn TW, MacLean AB. Cognitive, sensory, and emotional changes associated with the menstrual cycle: a review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278(4):299–307. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0708-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lynch WJ, Roth ME, Carroll ME. Biological basis of sex differences in drug abuse: preclinical and clinical studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;164(2):121–37. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sanders G, Sjodin M, de Chastelaine M. On the elusive nature of sex differences in cognition: hormonal influences contributing to within-sex variation. Arch Sex Behav. 2002;31(1):145–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1014095521499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sherwin BB. Estrogen and cognitive functioning in women. Endocr Rev. 2003;24(2):133–51. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Taylor GT, Maloney S. Gender differences and the role of estrogen in cognitive enhancements with nicotine in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;95(2):139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Roy EJ, Buyer DR, Licari VA. Estradiol in the striatum: effects on behavior and dopamine receptors but no evidence for membrane steroid receptors. Brain Res Bull. 1990;25(2):221–7. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Roth ME, Cosgrove KP, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the vulnerability to drug abuse: a review of preclinical studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28(6):533–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Carroll ME, et al. Sex and estrogen influence drug abuse. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25(5):273–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Evans SM. The role of estradiol and progesterone in modulating the subjective effects of stimulants in humans. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15(5):418–26. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Evans SM, Foltin RW. Exogenous progesterone attenuates the subjective effects of smoked cocaine in women, but not in men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(3):659–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lile JA, et al. Evaluation of estradiol administration on the discriminative-stimulus and subject-rated effects of d-amphetamine in healthy pre-menopausal women. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;87(2):258–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lynch WJ. Acquisition and maintenance of cocaine self-administration in adolescent rats: effects of sex and gonadal hormones. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197(2):237–46. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lynch WJ. Sex and ovarian hormones influence vulnerability and motivation for nicotine during adolescence in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;94(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sofuoglu M, et al. Sex and menstrual cycle differences in the subjective effects from smoked cocaine in humans. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7(3):274–83. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fox HC, Sinha R. Sex differences in drug-related stress-system changes: implications for treatment in substance-abusing women. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17(2):103–19. doi: 10.1080/10673220902899680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Phillips SM, Sherwin BB. Variations in memory function and sex steroid hormones across the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17(5):497–506. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90008-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Becker JB, Hu M. Sex differences in drug abuse. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29(1):36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cole LA, Ladner DG, Byrn FW. The normal variabilities of the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(2):522–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Allen SS, et al. Menstrual phase effects on smoking relapse. Addiction. 2008;103(5):809–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Allen SS, et al. Effects of transdermal nicotine on craving, withdrawal and premenstrual symptomatology in short-term smoking abstinence during different phases of the menstrual cycle. Nicotine Tob Res. 2000;2(3):231–41. doi: 10.1080/14622200050147493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Allen SS, et al. Symptomatology and energy intake during the menstrual cycle in smoking women. J Subst Abuse. 1996;8(3):303–19. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Allen SS, et al. Withdrawal and pre-menstrual symptomatology during the menstrual cycle in short-term smoking abstinence: effects of menstrual cycle on smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(2):129–42. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Franklin TR, et al. Retrospective study: influence of menstrual cycle on cue-induced cigarette craving. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(1):171–5. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.O'Hara P, Portser SA, Anderson BP. The influence of menstrual cycle changes on the tobacco withdrawal syndrome in women. Addict Behav. 1989;14(6):595–600. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Perkins KA, et al. Tobacco withdrawal in women and menstrual cycle phase. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(1):176–80. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pomerleau CS, et al. The effects of menstrual phase and nicotine abstinence on nicotine intake and on biochemical and subjective measures in women smokers: a preliminary report. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17(6):627–38. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Pomerleau CS, et al. Effects of menstrual phase and smoking abstinence in smokers with and without a history of major depressive disorder. Addict Behav. 2000;25(4):483–97. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Snively TA, et al. Smoking behavior, dysphoric states and the menstrual cycle: results from single smoking sessions and the natural environment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25(7):677–91. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Allen AM, et al. Patterns of cortisol and craving by menstrual phase in women attempting to quit smoking. Addict Behav. 2009;34(8):632–5. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Allen AM, et al. Circadian patterns of ad libitum smoking by menstrual phase. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(6):503–6. doi: 10.1002/hup.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Allen SS, et al. Patterns of self-selected smoking cessation attempts and relapse by menstrual phase. Addict Behav. 2009;34(11):928–31. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Allen SS, Allen AM, Pomerleau CS. Influence of phase-related variability in premenstrual symptomatology, mood, smoking withdrawal, and smoking behavior during ad libitum smoking, on smoking cessation outcome. Addict Behav. 2009;34(1):107–11. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Franklin TR, Allen SS. Influence of menstrual cycle phase on smoking cessation treatment outcome: a hypothesis regarding the discordant findings in the literature. Addiction. 2009;104(11):1941–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02758.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Terner JM, de Wit H. Menstrual cycle phase and responses to drugs of abuse in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Justice AJ, de Wit H. Acute effects of d-amphetamine during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle in women. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;145(1):67–75. doi: 10.1007/s002130051033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.White TL, Justice AJ, de Wit H. Differential subjective effects of D-amphetamine by gender, hormone levels and menstrual cycle phase. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73(4):729–41. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00818-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Justice AJ, De Wit H. Acute effects of d-amphetamine during the early and late follicular phases of the menstrual cycle in women. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66(3):509–15. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sofuoglu M, Mitchell E, Mooney M. Progesterone effects on subjective and physiological responses to intravenous nicotine in male and female smokers. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 2009;24(7):559–564. doi: 10.1002/hup.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sagvolden T. The spontaneously hypertensive rat as a model of ADHD. In: Solanto MV, Arnsten AF, Castellanos FX, editors. Stimulant Drugs and ADHD: Basic and Clinical Neuroscience. Oxford University Press, Inc.; New York: 2001. pp. 221–237. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Berger DF, Sagvolden T. Sex differences in operant discrimination behaviour in an animal model of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav Brain Res. 1998;94(1):73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sagvolden T, Berger DF. An animal model of attention deficit disorder: The female shows more behavioral problems and is more impulsive than the male. European Psychologist. 1996;1(2):113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Alsop B. Problems with spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) as a model of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (AD/HD) J Neurosci Methods. 2007;162(1–2):42–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rose JE. Nicotine and nonnicotine factors in cigarette addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:274–285. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Rose JE, et al. Dissociating nicotine and nonnicotine components of cigarette smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67(1):71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Rose JE, Levin ED. Inter-relationships between conditioned and primary reinforcement in the maintenance of cigarette smoking. Br J Addict. 1991;86(5):605–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.McClernon FJ, et al. Effects of smoking abstinence on adult smokers with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: results of a preliminary study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197(1):95–105. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Kollins SH, McClernon FJ, Epstein JN. Effects of smoking abstinence on reaction time variability in smokers with and without ADHD: an ex-Gaussian analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100(1–2):169–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.DeBon M, Klesges RC, Klesges LM. Symptomatology across the menstrual cycle in smoking and nonsmoking women. Addict Behav. 1995;20(3):335–43. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00070-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.McClernon FJ, et al. Smoking Withdrawal Symptoms Are More Severe Among Smokers With ADHD and Independent of ADHD Symptom Change: Results From a 12-Day Contingency-Managed Abstinence Trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Van Voorhees E, et al. An examination of differences in variables maintaining smoking behavior in adult smokers with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Addiction Research and Theory. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Van Voorhees EE, Kollins SH. College on Problems of Drug Dependence. Reno, NV: 2009. Sex effects of nicotine withdrawal in smokers with and without ADHD. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Aklin WM, et al. Early tobacco smoking in adolescents with externalizing disorders: inferences for reward function. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(6):750–5. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Baker F, Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in current and never-before cigarette smokers: similarities and differences across commodity, sign, and magnitude. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(3):382–92. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kollins SH, Lane SD, Shapiro SK. Experimental analysis of childhood psychopathology: a laboratory matching analysis of the behavior of children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) The Psychological Record. 1997;47:25–44. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Sonuga-Barke EJ. The dual pathway model of AD/HD: an elaboration of neuro-developmental characteristics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27(7):593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Husky MM, et al. Gender differences in the comorbidity of smoking behavior and major depression. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93(1–2):176–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Pomerleau OF, et al. Nicotine dependence, depression, and gender: characterizing phenotypes based on withdrawal discomfort, response to smoking, and ability to abstain. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(1):91–102. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Rao U, et al. Contribution of Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Activity and Environmental Stress to Vulnerability for Smoking in Adolescents. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009 doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]