Data reproducibility is a central tenet of the scientific process, but the culture of confirmation and re-confirmation risks falling by the wayside in competitive, fast-paced research environments where scientists tend to focus on their next publication. In fact, the independent confirmation of results can take years, as confirmatory or refuting data are hard to publish and often not taken into account by funders and search committees.

In reality, the systematic, independent confirmation of key advances is an unrealistic expectation but the publication of novel findings should at least be supported by evidence of reproducibility. Certainly, error bars adorn most data in reputable journals, but these statistics are not always informative and can lead to an over-emphasis of the significance of findings. For one, the statistics are sometimes not described in sufficient detail. Although many journals now require that authors state the number of independent repeats of an experiment, n, and the statistical tests applied, descriptions often remain too vague. Also, the statistical analysis applied is all-too-often inappropriate.

An opinion on this topic by David Vaux and colleagues appears in this issue of EMBO reports on p291 [1]. The article highlights the fact that all too often papers report the statistics of replicates, rather than independent repeats of an experiment—sometimes referred to as ‘pipetting error’ the measured variation is owing to the quality of the experimental setup, not the biological system. Worse, replicates are sometimes mixed with repeats: the experiment is repeated independently twice in triplicate and n is described as six, not two. As Vaux states, given the complex experimental procedures of molecular cell biology, replicates are essential to verify the quality of the experiment—in particular when reporting new methods—but they must not be reported in a way that misleads readers. As such, Vaux and colleagues recommend not reporting replicates at all. In our view, replicates can provide important information to readers, but they must be explicitly labelled in the figure legend to avoid readers incorrectly assuming that the statistics test the validity of the biological hypothesis.

In a complex biological system, it is essential to formulate conclusions based on reproducible, significant observations from independent experiments. However, we must acknowledge that scientists are often faced with constraints—be they financial, practical or ethical—that limit the number of times they can repeat an experiment. As such, it is essential to be as detailed as possible in defining n and the degree of independence between experiments (mouse littermates are caged together and exposed to the same food, diseases, light cycle and temperature, for example). One key part of an experiment that cannot be foregone to save resources is carefully designed controls, taking into account that the control group is also subject to variation.

In molecular cell biology, multiple independent experimental approaches—such as loss of function by siRNA, antisense, knockout or pharmacological inhibition—can often support robust conclusions despite a low number of independent repeats. Experience and intuition are essential to interpret complex and inherently noisy biological data. The scientific literature provides ample evidence that conclusions usually stand the test of time, even if the formal statistical relevance of much of the data is limited. However, under high publication pressure, it is undoubtedly hard to dispassionately test one's hypothesis and to consider other explanations. As Vaux and colleagues point out, one sensitive issue is disregarding ‘outlier’ data without good reason.

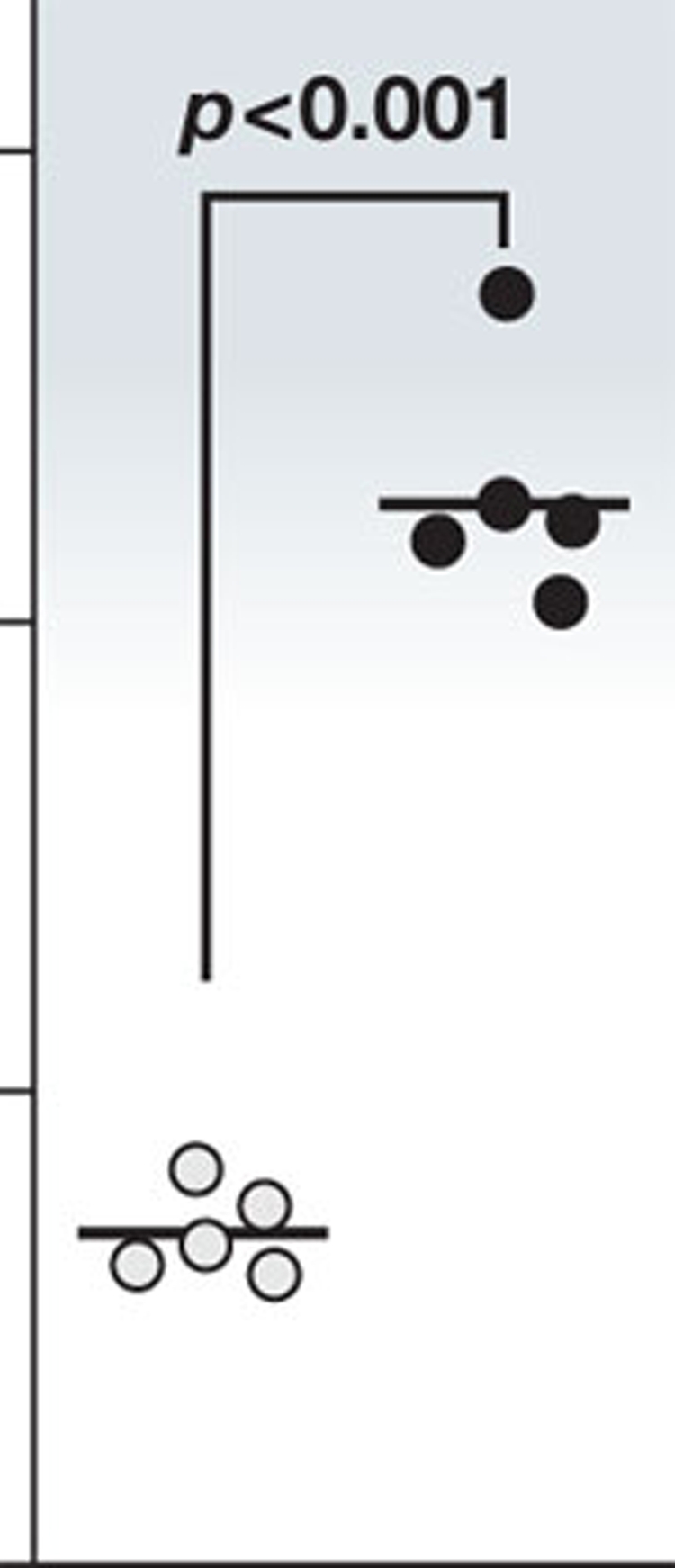

In our view, it is meaningful to apply statistical analysis to data even with few independent repeats, although care must be taken that the test applied is appropriate for values of n that can be counted on one hand; plot individual data points in these cases (see illustration). If transparent and accurate descriptions are provided, the expert reader knows how to interpret the data accurately; scientific progress should not be dampened through statistical over-evaluation. On the other hand, it is essential to apply formal statistical analysis where necessary; especially for high-throughput analyses such as microarrays and large-scale clinical trials, including multiple testing correction and informed threshold setting. We aim to involve expert statistics referees in such cases.

The EMBO scientific publications have explicit policies as part of their data transparency initiative to address the unavoidable limitations of the statistical analysis of some molecular-cell-biological data: (i) statistical information has to be accurately described; specify n in the figure panel or legend; (ii) when n is small, the actual measurements should be displayed instead of, or alongside, the mean and error bars in figure panels (see illustration); (iii) we strongly encourage authors to provide source data alongside figure panels to allow re-analysis of the primary data; (iv) ‘representative data’ and ‘data not shown’ are discouraged—the supplementary information section should be used to display such data.

We will evolve our policies to ensure the literature is robust and serves scientific progress.

References

- Vaux DL, Fidler F, Cumming G (2012) EMBO Rep 4: 291–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]