Abstract

Formation of trans-acting small interfering RNAs (ta-siRNAs) from the TAS3 precursor is triggered by the AGO7/miR390 complex, which primes TAS3 for conversion into double-stranded RNA by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase RDR6 and SGS3. These ta-siRNAs control several aspects of plant development. The mechanism routing AGO7-cleaved TAS3 precursor to RDR6/SGS3 and its subcellular organization are unknown. We show that AGO7 accumulates together with SGS3 and RDR6 in cytoplasmic siRNA bodies that are distinct from P-bodies. siRNA bodies colocalize with a membrane-associated viral protein and become positive for stress-granule markers upon stress-induced translational repression, this suggests that siRNA bodies are membrane-associated sites of accumulation of mRNA stalled during translation. AGO7 congregates with miR390 and SGS3 in membranes and its targeting to the nucleus prevents its accumulation in siRNA bodies and ta-siRNA formation. AGO7 is therefore required in the cytoplasm and membranous siRNA bodies for TAS3 processing, revealing a hitherto unknown role for membrane-associated ribonucleoparticles in ta-siRNA biogenesis and AGO action in plants.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, ARGONAUTE, membrane, trans-acting siRNA

Introduction

Trans-acting small interfering RNAs (ta-siRNAs) are plant-specific endogenous small regulatory RNAs that are produced from non-coding TAS genes and guide the cleavage of specific mRNA targets. ta-siRNA biogenesis requires an initial micro RNA (miRNA)-mediated cut and the conversion of one of the two cleavage products into a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) by the cellular RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE 6 (RDR6) and the SGS3 RNA-binding protein (Peragine et al, 2004; Vazquez et al, 2004; Allen et al, 2005). The resulting dsRNA is then processed into 21 nt ta-siRNAs by DICER-LIKE 4 (DCL4) (Dunoyer et al, 2005; Gasciolli et al, 2005; Hiraguri et al, 2005; Xie et al, 2005; Yoshikawa et al, 2005). ta-siRNAs have the ability to act non-cell autonomously (Chitwood et al, 2009; Schwab et al, 2009) and regulate the abundance of a diverse set of genes (Allen et al, 2005; Williams et al, 2005; Yoshikawa et al, 2005; Fahlgren et al, 2006; Hunter et al, 2006; Rajagopalan et al, 2006; Howell et al, 2007). An essential and yet enigmatic feature of ta-siRNA biogenesis is the specific routing of the miRNA-cleaved TAS precursors to RDR, different from most miRNA-guided mRNA cleavage products, which enter the 5′ → 3′ or 3′ → 5′ RNA degradation pathways because they lack either a 5′ Cap or a 3′ polyA tail.

ta-siRNAs produced from the TAS3 precursors target mRNA coding for the AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 3 (ARF3) and ARF4, which encode transcription factors mediating the effects of the phytohormone auxin (Williams et al, 2005; Fahlgren et al, 2006; Hunter et al, 2006). By way of this regulation, the TAS3 pathway controls the developmental timing of the transition between juvenile and adult leaves, contributes to the specification of leaves ad/abaxial polarity and controls the growth of lateral roots (Adenot et al, 2006; Fahlgren et al, 2006; Garcia et al, 2006; Hunter et al, 2006; Marin et al, 2010; Yoon et al, 2010). This pathway is one of the most ancient small RNA pathway and is conserved both mechanistically and functionally across all land plants (Axtell et al, 2006; Talmor-Neiman et al, 2006; Nogueira et al, 2007, 2009; Douglas et al, 2010). The TAS3 precursor is transcribed by RNA polymerase II as a long primary RNA and recognized by a complex of miR390 and AGO7 (Allen et al, 2005; Axtell et al, 2006; Montgomery et al, 2008). The TAS3 mRNA contains two sites complementary to miR390. Whereas the 3′ site is competent for cleavage (Allen et al, 2005; Axtell et al, 2006), the second 5′ site exhibits mismatches at positions 9–11, which prevent RNA cleavage (Axtell et al, 2006). Although miR390-mediated cleavage at the 3′ site does not exclusively rely on AGO7, ta-siRNA biogenesis requires AGO7 at the 5′ site (Montgomery et al, 2008; Cuperus et al, 2010a). This suggests that the miR390/AGO7 complex directs TAS3 precursors to the siRNA pathway.

Priming of other TAS precursors by a 22-nt miRNA associated with AGO1, but not by a 21-nt miRNA associated with AGO1, was recently shown to be instrumental for the routing of 3′ cleavage products to RDR6 (Chen et al, 2010; Cuperus et al, 2010b). However, another mechanism must be at play for TAS3 because miR390 is 21 nt long and routes a 5′ cleavage product to RDR6. As the miR390–AGO7 complex is specific to TAS3 processing, a careful analysis of its role might uncover an essential step in ta-siRNA biogenesis and further clarify the relationships between miRNA and siRNA pathways.

In plant and animal cells, certain AGO proteins have been shown to accumulate in cytoplasmic foci called P-bodies, sites at which numerous RNA decay enzymes are concentrated (Liu et al, 2005; Pillai et al, 2005; Sen and Blau, 2005; Zhang et al, 2006; Pomeranz et al, 2010). In most eukaryotes, a second set of ribonucleoprotein granules exists, the so-called stress granules. They represent cytoplasmic aggregates of non-translated mRNPs and have been suggested to serve as sorting sites, where mRNAs are targeted for storage, reinitiation or degradation by transfer to P-bodies (Anderson and Kedersha, 2009; Erickson and Lykke-Andersen, 2011). Their formation is triggered by the massive disassembly of polysomes as it occurs under stress conditions such as heat, oxidative or UV stress. Whereas P-bodies contain components of the mRNA decay machinery, stress granules contain components of the translation initiation machinery.

Very little is known about the subcellular compartments involved in ta-siRNA biogenesis. Whereas miRNAs are generated in the nucleus and exported into the cytoplasm, the key determinants of siRNA biogenesis, RDR6 and SGS3, accumulate in the cytoplasm (Glick et al, 2008; Elmayan et al, 2009; Kumakura et al, 2009). This raises the question of whether the miR390–AGO7-mediated priming of the TAS3 precursor occurs in the nucleus or in the cytoplasm.

Here, we show that a functional GFP-tagged version of AGO7 accumulates together with SGS3 and RDR6 in cytoplasmic foci. These foci, herein referred to as siRNA bodies, are distinct from P-bodies. Upon stress-induced translational repression, siRNA bodies become positive for stress-granules markers, suggesting that these bodies may accumulate stalled mRNAs. We also show that AGO7 colocalizes with the membrane-associated protein VP6 of the Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV), suggesting that AGO7 might interact with membranes. Furthermore, AGO7, together with miR390 and SGS3 associates tightly with the microsomal fraction, suggesting a link between AGO function and membrane-associated ribonucleoproteins. By modifying the subcellular localization of AGO7, we demonstrate that accumulation of AGO7 in the cytoplasm and the siRNA bodies is necessary for TAS3 processing.

Results

AGO7 localizes in cytoplasmic foci

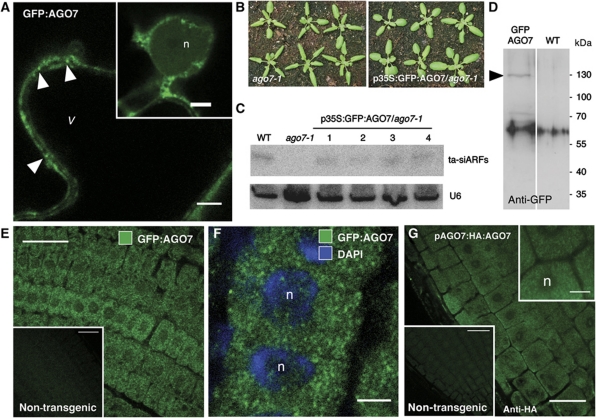

To determine the subcellular localization of AGO7, we generated an N-terminal translational fusion with GFP and transiently expressed the fusion protein from the constitutive p35S promoter in tobacco leaves and Arabidopsis protoplasts. In both systems, GFP–AGO7 signal was detected diffusely in the cytoplasm and in discrete foci (Figure 1A; Supplementary Figure S1, arrowheads). In tobacco cells, these foci were highly mobile and never observed in the nucleus. We also determined the localization of the GFP–AGO7 fusion after transformation of the ago7-1 mutant. Expression of the p35S:GFP–AGO7 construct complemented the typical zippy phenotype caused by loss of AGO7 function (narrow leaves, precocious appearance of trichome on the abaxial side of leaves; Hunter et al, 2003), indicating the functionality of the GFP–AGO7 fusion protein. However, because the T-DNA of the ago7-1 mutant causes partial transcriptional silencing of p35S-driven transgenes (Daxinger et al, 2008), the p35S:GFP–AGO7 construct was partially silenced, and the restoration of TAS3-derived ta-siRNA synthesis was below that of wild-type plants (Figure 1B and C). Moreover, we could not directly detect the fluorescence emitted by GFP–AGO7, even if a protein of the expected molecular weight was detected by western blot using an anti-GFP antibody (Figure 1D). We thus revealed GFP–AGO7 localization by immunofluorescence using an anti-GFP antibody on root meristem cells. We observed GFP–AGO7 signal in discrete cytoplasmic foci (Figure 1E and F); in the same conditions, no signal was detected in non-transgenic plants. These foci were of similar aspect as the ones observed in tobacco and Arabidopsis protoplast cells.

Figure 1.

AGO7 accumulates in cytoplasmic foci. (A) Confocal section of a Nicotiana tabacum leaves expressing GFP–AGO7. Cytoplasmic AGO7 foci are indicated by arrowheads. The cytoplasm appears as a thin peripheral layer, while the vacuole (v) fills most of the cell volume. Inset: GFP–AGO7 is not detected in the nucleus (n). (B) Morphology of 3-week-old ago7-1 or p35S:GFP:AGO7/ago7-1 Arabidopsis plants. ago7-1 plants display the typical zippy phenotype (narrow pointed leaves). (C) RNA gel blot analysis of 15 μg of total RNA from 7-day-old wild-type (WT), ago7-1 mutant or four independent p35S:GFP:AGO7/ago7-1 plants. The blot was probed with DNA complementary to ta-siARFs. U6 snRNA served as a loading control. (D) Western blot analysis of 7-day-old p35S:GFP:AGO7/ago7-1 plants. The blot was probed with an anti-GFP. The arrowhead indicates the position of the GFP–AGO7 band (127 kDa). (E) Indirect immunofluorescence detection of GFP–AGO7 in epidermal cells of the root meristem in 7-day-old p35S:GFP:AGO7/ago7-1 plants using an anti-GFP antibody. In meristem cells, the vacuole is not yet formed. The inset represents a non-transgenic plant processed and imaged in the same conditions. (F) Same as in (E) but counterstained with DAPI to mark nuclei (n). (G) Indirect immunofluorescence detection of HA–AGO7 in epidermal cells of the root meristem in 7-day-old pAGO7:HA:AGO7/zip-1 plants using an anti-HA antibody. The lower left inset represents a non-transgenic plant processed and imaged in the same conditions, whereas the upper right one is a higher magnification view. Scale bars: (A, F and G inset) 5 μm; (E, G) 25 μm. Figure source data can be found in Supplementary data.

To rule out the possibility that the foci observed for the GFP–AGO7 fusion expressed under the control of the p35S promoter are due to mislocalization induced by overexpression of the protein, we examined the subcellular localization of AGO7 fused to another tag (HA), and expressed at physiological levels from the native AGO7 promoter. The pAGO7:HA-AGO7 construct, herein abbreviated HA–AGO7, reverted both macroscopically and molecularly the ago7 (zip-1) mutant phenotype (Montgomery et al, 2008). In these plants, immunolocalization of AGO7 using an anti-HA antibody revealed accumulation of AGO7 in cytoplasmic granules comparable to the ones detected with the p35S:GFP-AGO7 (Figure 1G). These results indicate that AGO7 accumulates in cytoplasmic foci and that these foci very likely represent the physiological localization of AGO7 in plant cells.

AGO7 colocalizes with RDR6 and SGS3 in cytoplasmic siRNA bodies

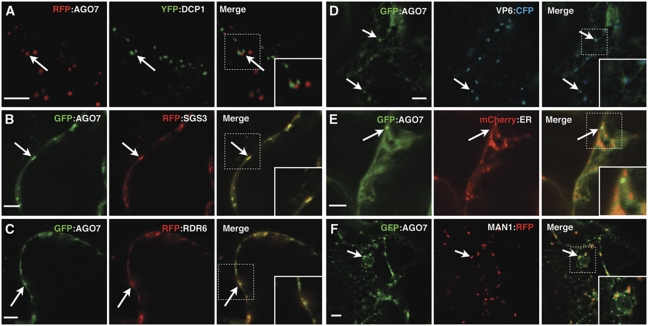

To identify the nature of the cytoplasmic foci in which AGO7 accumulates, we performed colocalization experiments using protein markers of specific subcellular compartments in tobacco leaves. We first tested whether the AGO7 foci are P-bodies by co-expression of p35S:RFP–AGO7 with p35S:YFP-DCP1. As previously described (Xu et al, 2006; Iwasaki et al, 2007; Xu and Chua, 2009), the YFP-DCP1 signal was exclusively cytoplasmic and consisted of small discrete foci, yet none of these foci colocalized with RFP–AGO7 (n=24 DCP1-positive bodies) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

AGO7 accumulates in membrane-linked cytoplasmic siRNA bodies. (A–F) Confocal sections of Nicotiana tabacum leaves expressing the indicated fluorescent fusion proteins. For each condition, the signals of the individual fluorophores are presented in the first two images whereas the signals are merged in the last image. The arrows indicate the AGO7/siRNA bodies. The dotted squares depict the location of the higher magnification insets. Scale bars: 5 μm.

During ta-siRNA biogenesis, AGO7 acts in conjunction with RDR6 and SGS3, two proteins that accumulate in specific cytoplasmic bodies (Glick et al, 2008; Elmayan et al, 2009; Kumakura et al, 2009), hereafter called siRNA bodies. To test whether AGO7 colocalizes with RDR6 and/or SGS3, we expressed GFP–AGO7 together with RFP–SGS3 or RFP–RDR6. GFP–AGO7 foci colocalized with both RFP–SGS3 and RFP–RDR6 foci (∼90% colocalization, n=50 foci) (Figure 2B and C).

Plant viruses induce a significant reorganization of the endomembrane system and induce the formation of replication bodies that differ from P-bodies and partially overlap with membrane-linked hot spots for initiation of viral replication complex formation (Laliberté and Sanfaçon, 2010). The TEV 6 kDa protein (VP6) is a membrane-associated protein required for viral replication (Restrepo-Hartwig and Carrington, 1994) and formation of viral replication complexes from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Schaad et al, 1997). In tobacco cells, VP6 accumulates in cytoplasmic foci marking an intermediary compartment between the ER and the cis-Golgi (Schaad et al, 1997; Lerich et al, 2011). Because AGO7, RDR6 and SGS3 have been implicated in plant defense against virus (Mourrain et al, 2000; Qu et al, 2008), we investigated whether siRNAs bodies and VP6 colocalized. We expressed GFP–AGO7 together with VP6–CFP and observed that the AGO7 signal partially overlapped with VP6 (∼60% colocalization, n=25 foci) (Figure 2D). We then looked at the relationships between siRNA bodies, the ER and cis-Golgi. For this, we co-expressed in tobacco leaves GFP–AGO7 and either a resident ER marker (p35S:ER-mCherry; Nelson et al, 2007) or the cis-Golgi marker p35S::MAN1–RFP (Lerich et al, 2011). Although no overlap between GFP–AGO7 and the ER could be observed (Figure 2E), we noticed that MAN1 and AGO7 signals tend to be adjacent to one another (Figure 2F), reminiscent of the relative disposition of VP6 and MAN1 (Lerich et al, 2011). Taken together, these results indicate that AGO7, RDR6 and SGS3 accumulate in cytoplasmic siRNA bodies.

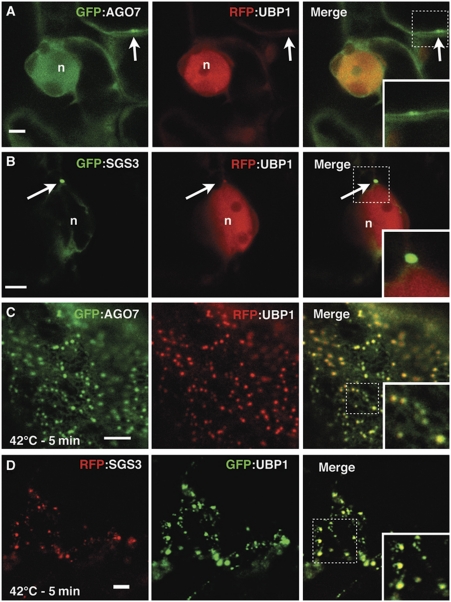

Cytoplasmic siRNA bodies form stress granules under heat-shock conditions

In plant cells under stress conditions, the pre-mRNA splicing factor UBP1 and the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) are markers of stress granules (Weber et al, 2008). Under normal growth conditions, UBP1 accumulates in the nucleus, whereas eIF4E is detected diffusely in the cytoplasm. When co-expressed with either SGS3 or AGO7 and observed under normal growth conditions, neither UBP1 nor eIF4E accumulated in the siRNA bodies (Figure 3A and B; Supplementary Figure S2). However, under conditions triggering the formation of stress granules (42°C for 5 min), siRNA bodies (as marked by SGS3 and AGO7) increased dramatically in number and showed perfect colocalization with UBP1 and eIF4E (Figure 3C and D; Supplementary Figure S2). This result shows that under stress conditions siRNA bodies become positive for markers of stress granules.

Figure 3.

siRNA bodies colocalize with stress granules after heat shock. (A–D) Confocal sections of Nicotiana tabacum leaves expressing the indicated fluorescent fusion proteins. For each condition, the green and red signals of the same plane are presented in two first images whereas the signals are merged in the last image. The arrows indicate the AGO7/siRNA bodies. The dotted squares depict the location of the higher magnification insets. Images in (C) and (D) were taken tangentially to the cytoplasm surface; n: nucleus. Scale bars: 5 μm.

siRNA bodies associate with a membrane-containing fraction

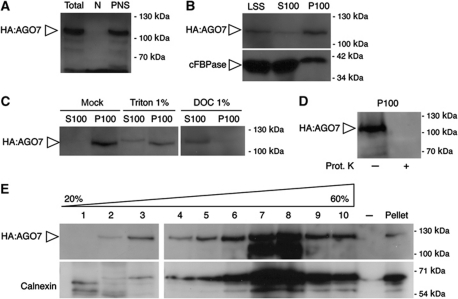

To further characterize the intracellular distribution of siRNA bodies and their association with membranes, we performed subcellular fractionations. HA–AGO7 seedlings were homogenized, large cellular debris and intact cells were removed by a first centrifugation and the supernatant was further centrifuged in presence of detergent (0.5% Triton) to generate a nuclei pellet (N) and a post-nuclear supernatant (PNS). The partition of AGO7 in these two fractions was tested by western blot using a monoclonal anti-HA antibody. AGO7 accumulated exclusively in the PNS (Figure 4A). The PNS association was confirmed in the p35S:GFP-AGO7/ago7-1 background (using an anti-GFP antibody) and in wild-type Arabidopsis plants using an anti-AGO7 antibody (Supplementary Figure S3). Therefore under physiological conditions, AGO7 accumulates in the cytoplasm.

Figure 4.

AGO7 copurifies with a membranous fraction. (A–E) Western blot analysis of 7-day-old pAGO7:HA-AGO7/zip-1 plants. Unless indicated otherwise, the blots were probed with an anti-HA antibody (HA–AGO7: 113 kDa). (A) Analysis of 75 μg of protein from the total, nuclear (N) and post-nuclear (PNS) fractions. (B) Analysis of 75 μg of protein from the low speed supernatant (LSS), soluble fraction (S100) and microsomal fraction (P100). The blot was probed with anti-HA (upper panel) and an antibody against the cytosolic fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (cFBPase, lower panel). (C) Resolubilization of the microsomal fraction by treatment with detergents (DOC: deoxycholate). In all, 75 μg of protein was analysed. (D) Analysis of 75 μg of protein from the resuspended microsomal fraction treated (+) or not (−) by the proteinase K (Prot. K) before recentrifugation at 100 000 g. (E) Analysis of the different fractions after separation of the resuspended microsomal fraction on a continuous (20–60% w/v) sucrose gradient. The blot was probed with anti-HA (upper panel) and an antibody against calnexin (lower panel). Figure source data can be found in Supplementary data.

In animal cells, select AGO proteins (human AGO2, Drosophila AGO1) associate with membranous compartments (Gibbings et al, 2009; Lee et al, 2009). To further investigate if AGO7 associates with membrane-containing compartments, we centrifuged homogenized HA–AGO7 seedlings to generate a low speed soluble fraction supernatant (LSS) and a pellet containing dense organelles (nuclei, plastids and mitochondria). The LSS was then centrifuged at 100 000 g, resulting in a microsomal pellet (P100) and a supernatant containing soluble proteins (S100). The bulk of AGO7 was retrieved in the microsomal pellet (P100; Figure 4B). In the same conditions, the soluble protein fructose 6 bisphosphatase remained mainly in the soluble fraction (S100; Figure 4B).

To analyse whether other markers of the siRNA bodies also accumulated in the microsomal fraction, we analysed the presence of SGS3 in the P100 fraction of wild-type Arabidopsis seedlings by western blot. Anti-SGS3 signal was detected in the P100 (Supplementary Figure S4), confirming that at physiological levels, AGO7 and SGS3 reside in subcellular fractions with similar properties.

The microsomal fraction consists of dense particles and membranous material (membranes and vesicles). To test if AGO7 is associated with a membranous compartment, we treated the P100 fraction with various detergents (1% Triton X-100 and 1% deoxycholate) before recentrifugation for 30 min at 100 000 g. Whereas treatment of the microsomal fraction with the non-ionic detergent Triton X-100 resolubilized partially AGO7, the ionic detergent deoxycholate solubilized most of AGO7 (Figure 4C). This resolubilization of AGO7 upon detergent treatment further reinforces an association with membranes. We then tested whether AGO7 was located within vesicles. For this, the P100 fraction was treated, in absence of any detergent, with proteinase K and then recentrifuged for 30 min at 100 000 g. The AGO7 signal was lost upon proteinase K treatment, indicating that AGO7 did not localize in a compartment protected from the protease action such as the lumen of vesicles (Figure 4D).

To further characterize the nature of the membranous compartment associated with AGO7, we resolved the resolubilized P100 fraction over a continuous sucrose gradient. HA–AGO7 signal peaked in fractions of a density of 40–45% sucrose (w/v) (Figure 4E, fractions 7–8); the resident ER protein calnexin was detected in the same fractions (Figure 4E).

Taken together, these results indicate that AGO7 resides on the cytoplasmic side of subcellular compartments with membrane-like properties.

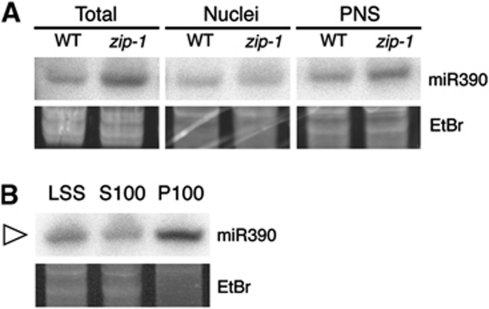

AGO7 and miR390 form an exclusive complex (Montgomery et al, 2008). To investigate where miR390 resides, we performed subcellular fractionation. We extracted small RNA from nuclear and post-nuclear fractions as well as from LSS, S100 and P100 fractions, and analysed by northern blot the presence of miR390 in these fractions. We could detect miR390 in both the nuclear and post-nuclear fractions (Figure 5A) and the P100 fraction (Figure 5B). In addition, miR390 partition in the post-nuclear and P100 fractions was not dependent on AGO7, as miR390 accumulated to a similar degree in zip-1 mutant and wild-type backgrounds (Figure 5A; Supplementary Figure S5).

Figure 5.

miR390 co-fractionates with AGO7. RNA gel blot analysis of 15 μg (A) or 30 μg (B) of RNA from 7-day-old plants. (A) Analysis of miR390 accumulation in the nuclear and post-nuclear fractions of wild-type and zip-1 plants. (B) Analysis of miR390 accumulation in low speed supernatant (LSS), soluble fraction (S100) and microsomal fraction (P100) of wild-type plants. Ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining served as a loading control. Figure source data can be found in Supplementary data.

Nuclear localization impairs AGO7 function in ta-siRNA biogenesis

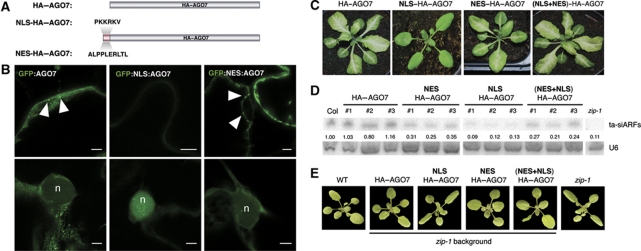

To test the functional relevance of AGO7 accumulation in cytoplasmic siRNA bodies, we engineered versions of AGO7 with a modified subcellular localization. For this, we added to AGO7 a nuclear localization signal (NLS: PKKKRKV) to force its localization to the nucleus. The NLS sequence was added at the N-terminal end of AGO7, a position where sequences such as trimerized HA tags or GFP can be added without compromising the function of the protein (Figure 6A). The effect of the NLS motif on AGO7 subcellular localization was tested by transiently expressing the NLS-AGO7 allele as a GFP fusion in tobacco leaves. Addition of the NLS motif led to strong decrease in the cytoplasmic localization with no remaining signal in the siRNA bodies, and the concomitant appearance of NLS-AGO7 signal in the nucleus (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Nuclear localization impairs AGO7 function in ta-siRNA biogenesis. (A) Schematic representation of AGO7 and the NLS and NES alleles used. (B) Confocal sections of Nicotiana tabacum leaves expressing the indicated fluorescent fusion proteins. On the upper panels are views of the cytoplasm and on the lower panels of the nuclei (n). The arrowheads indicate the AGO7 siRNA bodies. Scale bars: 5 μm. (C) Morphology of 3-week-old syntasi-PDS/zip-1 Arabidopsis plants expressing the indicated construct from the AGO7 promoter. Bleached plants harbour white sectors radiating from the veins. (D) RNA gel blot analysis of 30 μg of total RNA from zip-1 inflorescence expressing the indicated construct from the AGO7 promoter. Each lane represents independent primary transformants (three for each allele). The blot was probed with DNA complementary to ta-siARFs. U6 snRNA served as a loading control and numbers indicate normalized intensities. (E) Morphology of 3-week-old wild-type and zip-1 Arabidopsis plants expressing the indicated construct from the AGO7 promoter. Figure source data can be found in Supplementary data.

We then tested the ability of this variant protein to functionally replace AGO7 in triggering formation of ta-siRNA when expressed at physiological levels. For this, we took advantage of a synthetic TAS3 gene in which ta-siARFs were replaced by ta-siRNA targeting the PDS involved in β-carotenoid formation (Montgomery et al, 2008). In a wild-type background, the syntasi-PDS plants leaves are photobleached around the veins, whereas in absence of AGO7 function, in the syntasi-PDS/zip-1 background, the leaves remain green (Montgomery et al, 2008). We expressed in syntasi-PDS/zip-1 plants HA-tagged versions of AGO7 and NLS-HA–AGO7 from the native AGO7 promoter, and scored for bleached plants among the primary transformants retrieved. About 50% of pAGO7:HA-AGO7 primary transformants displayed a bleached phenotype (Figure 6C) whereas none could be retrieved for the pAGO7:NLS-HA-AGO7 transformation (Figure 6C). This was not due to a change in protein stability, as we could detect the full-length protein by western blot (Supplementary Figure S6). This result suggested that accumulation of AGO7 in the nucleus impaired its function. To ascertain this result and to rule out that addition of the NLS inactivated AGO7 activity as a whole, we added a nuclear export signal (NES: ALPPLERLTL) to either HA–AGO7 or NLS-HA–AGO7. When expressed from the AGO7 promoter and transformed into syntasi-PDS/zip-1 plants both the NES-HA-AGO7 and (NES+NLS)-HA-AGO7 alleles restored the bleaching phenotype (Figure 6C). This suggested that accumulation of AGO7 in cytoplasmic siRNA bodies is crucial for its function and targeting to these bodies only occurs outside of the nucleus.

This result was further confirmed by expressing the HA–AGO7, NLS-HA–AGO7 and (NES+NLS)-HA–AGO7 from the AGO7 promoter in Arabidopsis zip-1 mutants and scoring for reversion of the zippy phenotype both macroscopically (elongated leaves, precocious appearance of adult leaves) and molecularly (formation of ta-siRNAs). Similarly to the results obtained in the syntasi-PDS/zip-1 line, NLS-HA–AGO7 failed to complement the zip-1 phenotype, whereas HA–AGO7 and (NES+NLS)-HA–AGO7 did (Figure 6E). The zip-1 mutant plants accumulate much reduced levels of ta-siARFs (Figure 6D). Accumulation of ta-siARFs was restored upon expression of NES-HA–AGO7 and (NES+NLS)-HA–AGO7 but not of NLS-HA–AGO7 (Figure 6D). However, the ta-siARFs levels were reduced for NES-HA–AGO7 and (NES+NLS)-HA–AGO7 compared with expression of HA–AGO7, indicating that although able to revert the zip-1 phenotype, these alleles yield proteins less efficient than AGO7 (Figure 6D). Taken together, these results strongly argue that the presence of AGO7 in cytoplasmic siRNA bodies is essential for the formation of ta-siRNAs.

Discussion

In this paper, we show that in plant cells, cytoplasmic AGO7 accumulates in membrane-associated SGS3/RDR6-containing siRNA bodies. We establish the functional relevance of this localization by showing that nuclear relocalization of AGO7 impairs ta-siRNA biogenesis.

Our results establish that biogenesis of TAS3-derived ta-siRNA requires the addressing of AGO7 to a specialized cellular compartment in the cytoplasm. The presence in siRNA bodies of the key components of ta-siRNA formation and their co-purification with membranes suggest a model in which, upon accumulation of the ternary complex miR390/AGO7/TAS3 in siRNA bodies, the product of TAS3 miR390-mediated cleavage would be passed on to RDR6 and SGS3 for conversion into a dsRNA. In agreement with previous reports (Hiraguri et al, 2005; Kumakura et al, 2009; Hoffer et al, 2011), we could not detect DCL4 outside of the nucleus (data not shown), suggesting that further processing occurs outside of the siRNA bodies. Further work is required to test whether accumulation in the siRNA bodies occurs pre- or post-miRNA cleavage, and if this accumulation is cause or consequence of AGO7 recruitment onto the TAS3 precursor.

Viruses are known to highjack the early secretory system to trigger the formation of viral replication complexes (Laliberté and Sanfaçon, 2010). The colocalization observed between AGO7 and the membrane-linked VP6 protein suggests that siRNA bodies contain membranes. This is paralleled by the similar biochemical properties of AGO7 and VP6: retrieval from the microsomal fraction, resolubilization by detergent and light density on sucrose gradient (Schaad et al, 1997). In addition, SGS3 is also retrieved in the microsomal fraction (Supplementary Figure S4). The nature and mechanism of AGO7 association with membranes are unknown. Accumulation of AGO7 in the P100 fraction is unaffected in sgs3 or rdr6 mutants (Supplementary Figure S7), indicating that RDR6 and SGS3 are not required for AGO7 targeting. Several post-translational modifications of animal AGO proteins have been reported (for review, see Johnston and Hutvagner, 2011). Among those, prolyl-hydroxylation (Qi, et al 2008) might control accumulation of human AGO2 in multi-vesicular bodies (MVB). It may be that post-translational modification of AGO7 and/or association with a yet unknown cofactor is required for membrane targeting.

Association of AGO proteins with the endomembrane system has been reported in animal cells Arabidopsis, MVB mature from the trans-Golgi network/early endosome whereas VP6 defines an intermediary compartment between ER and cis-Golgi (Gibbings and Voinnet, 2010; Lerich et al, 2011). In particular in Drosophila and mammalian cells, AGO proteins associate with MVB, and this contributes to AGO recycling (Gibbings et al, 2009; Lee et al, 2009). Although plant cells possess MVB, we consider it unlikely that the association of AGO7 with membranes reflects its localization in MVB. Indeed, in Arabidopsis, MVB mature from the trans-Golgi network/early endosome whereas VP6 defines an intermediary compartment between ER and cis-Golgi (Lerich et al, 2011).

The congregation of siRNA bodies, containing RDR6 and SGS3 both of which are essential for plant defense against virus, and VP6, a viral protein required for virus replication, suggest that siRNA bodies are a point of convergence between viral replication and the host defense mechanisms. In turn, endogenous small RNA pathways such as the miR390/TAS3 pathway, making use of the siRNA-production machinery, accumulate into the siRNA bodies.

Previous work has suggested that products of miRNA-mediated cleavage of TAS precursors transfer from P-bodies to the siRNA bodies for conversion into dsRNA (Kumakura et al, 2009). However, we never observed AGO7 in P-bodies marked with DCP1. This further reinforces the important differences between the mechanisms of ta-siRNA formation from TAS1/2 (dependent on 22 nt miRNA and AGO1) and from TAS3 (dependent on 21 nt miRNA and AGO7). The presence and still elusive role of the non-cleavable miR390 site in TAS3 (Montgomery et al, 2008) could be linked to the specific targeting of the miR390/AGO7/TAS3 complex to the siRNA bodies. It is possible that 22 nt miRNA-loaded AGO1 also accumulate in siRNA bodies.

A hallmark of mRNA targeted to processing by RDR6/SGS3 is their poor ability to be translated. This is either due to a very poor coding potential, as in the case of TAS3 (Ben Amor et al, 2009), or because, as a consequence of miRNA-mediated cleavage, these mRNAs lack the canonical marks (5′ CAP and 3′ polyA tail) required for efficient translation. Because siRNA bodies, unlike stress granules, are readily detected under normal growth conditions, this suggests that siRNA bodies could represent a microscopic aggregate of mRNAs stalled in translation. Upon stress-induced shut down of translation, siRNA bodies may serve as seeds for the formation of numerous stress granules. This is supported by the observation that upon massive shut down of translation induced by stress, siRNA bodies increase dramatically in number and accumulate canonical markers of mRNAs stalled at the translation initiation stage (as eIF4E, UBP1). The dynamic nature of siRNA bodies suggests that they are sites of mRNA triage, wherein mRNA could be sorted for degradation by P-bodies or enter the siRNA pathway.

Taken together, our results reveal a hitherto unknown role for specific cytoplasmic membrane-associated ribonucleoparticles in ta-siRNA biogenesis and AGO action in plants.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

All Arabidopsis thaliana lines used are in the Columbia ecotype (Col-0) background. The following mutants were described previously: ago7-1 (SALK_037458; Adenot et al, 2006), zip-1 (CS24281; Hunter et al, 2003), and tas3a-1 (GABI_621G08; Adenot et al, 2006). The pAGO7:HA:AGO7/zip-1 and p35S:TAS3aPDS-1/zip-1 lines were described in Montgomery et al (2008). For in-vitro conditions, plants were grown on sterile 0.5 × Murashige and Skoog (MS)/0.8% agar (1/2 MS agar) plates in a growth chamber under controlled conditions (150 mmol photon, 16 h light and 23°C temperature). For soil conditions, plants were grown in a growth room (150 mmol photon, 16 h light and 23°C temperature).

Subcellular fractionations

Nuclear/PNS fractionation was performed according to Park et al (2005). Briefly, plant material was ground and cell wall-disrupting buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM b-mercaptoethanol, 1 M hexylene glycerol) was added. The sample was filtered through Miracloth and centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and recentrifuged at 13 000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant of this second centrifugation corresponds to the PNS. The first pellet was washed with nuclei preparation buffer (NPB) (10 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM b-mercaptoethanol, 1 M hexylene glycerol, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100) and centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed with NPB. Washing and centrifugation were repeated four to five times, and the final pellet was stored as the nuclear fraction.

Microsomal fractions were obtained as follow. Plant material was ground to fine powder under liquid nitrogen. In all, 2 × volume of homogenization buffer (Sorbitol 0.5 M, EDTA 10 mM, PVP 40 0.5%, Protease inhibitor cocktail) was added. The sample was filtered through Miracloth. The filter extract was centrifuged for 15 min at 8000 g at 4°C. The supernatant (low speed supernatant—LSS) was then centrifuged at 100 000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant corresponds to the S100 and the pellet to the P100. For resolubilization test, the P100 fraction was resuspended in 5 × volume of the same buffer supplemented with detergent, incubated for 30 min on ice and centrifuged at 100 000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant corresponds to the S100 and the pellet to the P100. The S100 fraction was precipitated (see below) before analysis.

Proteins extraction and immunoblot

Proteins were extracted as follow, 100 mg of plant material finely ground was mixed with 300 μl of extraction buffer (0.7 M Sucrose; 0.5 M Tris–HCl pH 8; 5 mM EDTA; 0.1 M NaCl; 2% b-mercaptoethanol; protease inhibitor (Roche)). The same volume of phenol (pH 8) was added. The sample was mixed 20 min at room temperature and then centrifuged at 13 000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The phenolic phase was precipitated with five volumes of ammonium acetate (0.1 M) in absolute methanol at −20°C. The proteins were pelleted at 5000 g for 5 min at 4°C, washed with 80% acetone and finally resuspended in 300 μl of resuspension solution (3% SDS; 62.5 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8; 10% glycerol). The samples were incubated at 65°C for 10 min, centrifuged at 13 000 g for 5 min and the supernatant was kept for quantification and analysis. Protein concentration was quantified using a detergent compatible BCA kit (Bio-Rad) and 75 μg of protein was loaded on gel.

The protein extracts were separated by SDS–PAGE (8%), and proteins were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Hybond ECL). The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies and subsequent HRP-coupled secondary IgGs. Antigens were detected using chemiluminescence for HRP immunoblot (Amersham ECL Plus). The antibodies used were anti-HA (12CA5, 1/1000e dilution; Roche); anti-GFP (sc-8334, 1/1000e dilution; Santa Cruz); anti-SGS3 (sc-14068, 1/200e dilution; Santa Cruz); anti-mouse HRP-coupled (NA931, 1/2500e dilution; GE Healthcare), anti-rabbit HRP-coupled (NA934, 1/2500e dilution; GE Healthcare), and anti-goat HRP-coupled (611620, 1/5000e dilution; Invitrogen).

Whole-mount immunofluorescence

Whole-mount immunofluorescence was performed on 7-day-old roots according to Sauer et al (2006) with slight modifications. See Supplementary data for detailed protocol. The antibodies used were anti-HA (12CA5, 1/100e dilution; Roche); anti-GFP (sc-8334, 1/100e dilution; Santa Cruz); anti-mouse coupled to Alexa488 (A11017, 1/1000e dilution; Invitrogen) and anti-rabbit coupled to Alexa488 (A11070, 1/1000e dilution; Invitrogen).

Imaging

For confocal imaging, tobacco leaves were mounted in 15% glycerol and directly imaged on a Leica TCS SP5 (Leica Microsystems) with 488/543 nm excitation, 488/543 beamsplitter filter and 495–530 nm (green channel) and 550–700 nm (red channel) detection windows. All images were acquired with similar gain adjustments.

Arabidopsis plants were imaged after immunofluorescence on a Leica TCS SP5 (Leica Microsystems) with 488 nm excitation, 488 beamsplitter filter and 495–530 nm (green channel) detection window. For DAPI detection, a 364-nm UV laser (no beamsplitter filter set, detection window of 415–550 nm) was used.

Plasmid and cloning

See Supplementary data for details on the plasmids used and cloning procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J Carrington for the HA–AGO7 and TAS3-PDS lines; M Fauth for the eIF4E and UBP1 constructs; G Hinz for help with the subcellular fractionation; A Lerich and DG Robinson for the VP6 and MAN1 constructs; and K Schumacher for the anti-cFBPase and anti-calnexin antibodies. We thank A Leibfried, K Schumacher and G Stoecklin for their comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Land Baden-Württemberg, the Chica und Heinz Schaller Stiftung and the CellNetworks cluster of excellence (to AM); The Agence Nationale de la Recherche ANR-08-BLAN-0082 (to AM) and ANR-10-BLAN-1707 (to HV); The ministry for higher education and research (to VJ).

Author contributions: ABM generated materials and contributed to the colocalization studies. TE realized the biochemical analysis of SGS3. VJ performed all other experiments and helped writing the paper. AM, with the help of MC and HV, wrote the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adenot X, Elmayan T, Lauressergues D, Boutet S, Bouche N, Gasciolli V, Vaucheret H (2006) DRB4-dependent TAS3 trans-acting siRNAs control leaf morphology through AGO7. Curr Biol 16: 927–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen E, Xie Z, Gustafson AM, Carrington JC (2005) microRNA-directed phasing during trans-acting siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell 121: 207–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kedersha N (2009) RNA granules: post-transcriptional and epigenetic modulators of gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 430–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell MJ, Jan C, Rajagopalan R, Bartel DP (2006) A two-hit trigger for siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell 127: 565–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Amor B, Wirth S, Merchan F, Laporte P, d'Aubenton-Carafa Y, Hirsch J, Maizel A, Mallory A, Lucas A, Deragon JM, Vaucheret H, Thermes C, Crespi M (2009) Novel long non-protein coding RNAs involved in Arabidopsis differentiation and stress responses. Genome Res 19: 57–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HM, Chen LT, Patel K, Li YH, Baulcombe DC, Wu SH (2010) 22-nucleotide RNAs trigger secondary siRNA biogenesis in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 15269–15274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood DH, Nogueira FT, Howell MD, Montgomery TA, Carrington JC, Timmermans MC (2009) Pattern formation via small RNA mobility. Genes Dev 23: 549–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuperus JT, Carbonell A, Fahlgren N, Garcia-Ruiz H, Burke RT, Takeda A, Sullivan CM, Gilbert SD, Montgomery TA, Carrington JC (2010a) Unique functionality of 22-nt miRNAs in triggering RDR6-dependent siRNA biogenesis from target transcripts in Arabidopsis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 997–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuperus JT, Montgomery TA, Fahlgren N, Burke RT, Townsend T, Sullivan CM, Carrington JC (2010b) Identification of MIR390a precursor processing-defective mutants in Arabidopsis by direct genome sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 466–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daxinger L, Hunter B, Sheikh M, Jauvion V, Gasciolli V, Vaucheret H, Matzke M, Furner I (2008) Unexpected silencing effects from T-DNA tags in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci 13: 4–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RN, Wiley D, Sarkar A, Springer N, Timmermans MC, Scanlon MJ (2010) Ragged seedling2 encodes an ARGONAUTE7-like protein required for mediolateral expansion, but not dorsiventrality, of maize leaves. Plant Cell 22: 1441–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunoyer P, Himber C, Voinnet O (2005) DICER-LIKE 4 is required for RNA interference and produces the 21-nucleotide small interfering RNA component of the plant cell-to-cell silencing signal. Nat Genet 37: 1356–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmayan T, Adenot X, Gissot L, Lauressergues D, Gy I, Vaucheret H (2009) A neomorphic sgs3 allele stabilizing miRNA cleavage products reveals that SGS3 acts as a homodimer. FEBS J 276: 835–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson SL, Lykke-Andersen J (2011) Cytoplasmic mRNP granules at a glance. J Cell Sci 124: 293–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlgren N, Montgomery TA, Howell MD, Allen E, Dvorak SK, Alexander AL, Carrington JC (2006) Regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR3 by TAS3 ta-siRNA affects developmental timing and patterning in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 16: 939–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D, Collier SA, Byrne ME, Martienssen RA (2006) Specification of leaf polarity in Arabidopsis via the trans-acting siRNA pathway. Curr Biol 16: 933–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasciolli V, Mallory AC, Bartel DP, Vaucheret H (2005) Partially redundant functions of Arabidopsis DICER-like enzymes and a role for DCL4 in producing trans-acting siRNAs. Curr Biol 15: 1494–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbings D, Voinnet O (2010) Control of RNA silencing and localization by endolysosomes. Trends Cell Biol 20: 491–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbings DJ, Ciaudo C, Erhardt M, Voinnet O (2009) Multivesicular bodies associate with components of miRNA effector complexes and modulate miRNA activity. Nat Cell Biol 11: 1143–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick E, Zrachya A, Levy Y, Mett A, Gidoni D, Belausov E, Citovsky V, Gafni Y (2008) Interaction with host SGS3 is required for suppression of RNA silencing by tomato yellow leaf curl virus V2 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 157–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraguri A, Itoh R, Kondo N, Nomura Y, Aizawa D, Murai Y, Koiwa H, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Fukuhara T (2005) Specific interactions between Dicer-like proteins and HYL1/DRB-family dsRNA-binding proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 57: 173–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer P, Ivashuta S, Pontes O, Vitins A, Pikaard C, Mroczka A, Wagner N, Voelker T (2011) Posttranscriptional gene silencing in nuclei. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 409–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell MD, Fahlgren N, Chapman EJ, Cumbie JS, Sullivan CM, Givan SA, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC (2007) Genome-wide analysis of the RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE6/DICER-LIKE4 pathway in Arabidopsis reveals dependency on miRNA- and tasiRNA-directed targeting. Plant Cell 19: 926–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C, Sun H, Poethig RS (2003) The Arabidopsis heterochronic gene ZIPPY is an ARGONAUTE family member. Curr Biol 13: 1734–1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C, Willmann MR, Wu G, Yoshikawa M, de la Luz Gutiérrez-Nava M, Poethig SR (2006) Trans-acting siRNA-mediated repression of ETTIN and ARF4 regulates heteroblasty in Arabidopsis. Development 133: 2973–2981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki S, Takeda A, Motose H, Watanabe Y (2007) Characterization of Arabidopsis decapping proteins AtDCP1 and AtDCP2, which are essential for post-embryonic development. FEBS Lett 581: 2455–2459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M, Hutvagner G (2011) Posttranslational modification of Argonautes and their role in small RNA-mediated gene regulation. Silence 2: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumakura N, Takeda A, Fujioka Y, Motose H, Takano R, Watanabe Y (2009) SGS3 and RDR6 interact and colocalize in cytoplasmic SGS3/RDR6-bodies. FEBS Lett 583: 1261–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laliberté JF, Sanfaçon H (2010) Cellular remodeling during plant virus infection. Annu Rev Phytopathol 48: 69–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Pressman S, Andress AP, Kim K, White JL, Cassidy JJ, Li X, Lubell K, Lim do H, Cho IS, Nakahara K, Preall JB, Bellare P, Sontheimer EJ, Carthew RW (2009) Silencing by small RNAs is linked to endosomal trafficking. Nat Cell Biol 11: 1150–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerich A, Langhans M, Sturm S, Robinson DG (2011) Is the 6 kDa tobacco etch viral protein a bona fide ERES marker? J Exp Bot 62: 5013–5023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Hannon GJ, Parker R (2005) MicroRNA-dependent localization of targeted mRNAs to mammalian P-bodies. Nat Cell Biol 7: 719–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin E, Jouannet V, Herz A, Lokerse AS, Weijers D, Vaucheret H, Nussaume L, Crespi MD, Maizel A (2010) miR390, Arabidopsis TAS3 tasiRNAs, and their AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR targets define an autoregulatory network quantitatively regulating lateral root growth. Plant Cell 22: 1104–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery TA, Howell MD, Cuperus JT, Li D, Hansen JE, Alexander AL, Chapman EJ, Fahlgren N, Allen E, Carrington JC (2008) Specificity of ARGONAUTE7-miR390 interaction and dual functionality in TAS3 trans-acting siRNA formation. Cell 133: 128–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourrain P, Béclin C, Elmayan T, Feuerbach F, Godon C, Morel JB, Jouette D, Lacombe AM, Nikic S, Picault N, Rémoué K, Sanial M, Vo TA, Vaucheret H (2000) Arabidopsis SGS2 and SGS3 genes are required for posttranscriptional gene silencing and natural virus resistance. Cell 101: 533–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BK, Cai X, Nebenführ A (2007) A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J 51: 1126–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira FT, Chitwood DH, Madi S, Ohtsu K, Schnable PS, Scanlon MJ, Timmermans MC (2009) Regulation of small RNA accumulation in the maize shoot apex. PLoS Genet 5: e1000320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira FT, Madi S, Chitwood DH, Juarez MT, Timmermans MC (2007) Two small regulatory RNAs establish opposing fates of a developmental axis. Genes Dev 21: 750–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MY, Wu G, Gonzalez-Sulser A, Vaucheret H, Poethig RS (2005) Nuclear processing and export of microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 3691–3696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peragine A, Yoshikawa M, Wu G, Albrecht HL, Poethig RS (2004) SGS3 and SGS2/SDE1/RDR6 are required for juvenile development and the production of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 18: 2368–2379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai RS, Bhattacharyya SN, Artus CG, Zoller T, Cougot N, Basyuk E, Bertrand E, Filipowicz W (2005) Inhibition of translational initiation by Let-7 MicroRNA in human cells. Science 309: 1573–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeranz MC, Hah C, Lin PC, Kang SG, Finer JJ, Blackshear PJ, Jang JC (2010) The Arabidopsis tandem zinc finger protein AtTZF1 traffics between the nucleus and cytoplasmic foci and binds both DNA and RNA. Plant Physiol 152: 151–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi HH, Ongusaha PP, Myllyharju J, Cheng D, Pakkanen O, Shi Y, Lee SW, Peng J, Shi Y (2008) Prolyl 4-hydroxylation regulates Argonaute 2 stability. Nature 455: 421–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu F, Ye X, Morris TJ (2008) Arabidopsis DRB4, AGO1, AGO7, and RDR6 participate in a DCL4-initiated antiviral RNA silencing pathway negatively regulated by DCL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 14732–14737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan R, Vaucheret H, Trejo J, Bartel DP (2006) A diverse and evolutionarily fluid set of microRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev 20: 3407–3425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo-Hartwig MA, Carrington JC (1994) The tobacco etch potyvirus 6-kilodalton protein is membrane associated and involved in viral replication. J Virol 68: 2388–2397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer M, Jakob A, Nordheim A, Hochholdinger F (2006) Proteomic analysis of shoot-borne root initiation in maize (Zea mays L.). Proteomics 6: 2530–2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaad MC, Jensen PE, Carrington JC (1997) Formation of plant RNA virus replication complexes on membranes: role of an endoplasmic reticulum-targeted viral protein. EMBO J 16: 4049–4059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab R, Maizel A, Ruiz-Ferrer V, Garcia D, Bayer M, Crespi M, Voinnet O, Martienssen RA (2009) Endogenous TasiRNAs mediate non-cell autonomous effects on gene regulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One 4: e5980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen GL, Blau HM (2005) Argonaute 2/RISC resides in sites of mammalian mRNA decay known as cytoplasmic bodies. Nat Cell Biol 7: 633–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmor-Neiman M, Stav R, Klipcan L, Buxdorf K, Baulcombe DC, Arazi T (2006) Identification of trans-acting siRNAs in moss and an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase required for their biogenesis. Plant J 48: 511–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez F, Vaucheret H, Rajagopalan R, Lepers C, Gasciolli V, Mallory AC, Hilbert JL, Bartel DP, Crété P (2004) Endogenous trans-acting siRNAs regulate the accumulation of Arabidopsis mRNAs. Mol Cell 16: 69–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber C, Nover L, Fauth M (2008) Plant stress granules and mRNA processing bodies are distinct from heat stress granules. Plant J 56: 517–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L, Carles CC, Osmont KS, Fletcher JC (2005) A database analysis method identifies an endogenous trans-acting short-interfering RNA that targets the Arabidopsis ARF2, ARF3, and ARF4 genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 9703–9708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Allen E, Wilken A, Carrington JC (2005) DICER-LIKE 4 functions in trans-acting small interfering RNA biogenesis and vegetative phase change in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 12984–12989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Chua NH (2009) Arabidopsis decapping 5 is required for mRNA decapping, P-body formation, and translational repression during postembryonic development. Plant Cell 21: 3270–3279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Yang JY, Niu QW, Chua NH (2006) Arabidopsis DCP2, DCP1, and VARICOSE form a decapping complex required for postembryonic development. Plant Cell 18: 3386–3398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon EK, Yang JH, Lim J, Kim SH, Kim SK, Lee WS (2010) Auxin regulation of the microRNA390-dependent transacting small interfering RNA pathway in Arabidopsis lateral root development. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 1382–1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa M, Peragine A, Park MY, Poethig RS (2005) A pathway for the biogenesis of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 19: 2164–2175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Yuan YR, Pei Y, Lin SS, Tuschl T, Patel DJ, Chua NH (2006) Cucumber mosaic virus-encoded 2b suppressor inhibits Arabidopsis Argonaute1 cleavage activity to counter plant defense. Genes Dev 20: 3255–3268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.