Abstract

In the gut of patients with Crohn's disease (CD), high Smad7 blocks the immune-suppressive activity of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, thereby contributing to amplify inflammatory signals. In vivo in mice, knockdown of Smad7 with a Smad7 antisense oligonucleotide (GED0301) attenuates experimental colitis. Here, we provide results of a phase 1 clinical, open-label, dose-escalation study of GED0301 in patients with active, steroid-dependent/resistant CD, aimed at assessing the safety and tolerability of the drug. Patients were allocated to three treatment groups receiving oral GED0301 once daily for 7 days at doses of 40, 80, or 160 mg. A total of 15 patients were enrolled. No serious adverse event was registered. GED0301 was well tolerated and no patient dropped out during the study. Twenty-five adverse events were documented in 11 patients, the majority of whom were judged to be of mild intensity and unrelated to treatment. GED0301 treatment reduced the percentage of inflammatory cytokine-expressing CCR9-positive T cells in the blood. The study shows for the first time that GED0301 is safe and well tolerated in patients with active CD.

Introduction

Crohn's disease (CD), a serious and chronic illness that primarily affects the small intestine and colon, is characterized by segmental, transmural inflammation, and tissue damage.1 Since the cause of CD is unknown, medical management of CD patients is largely symptom-based.2,3 Immunosuppressive drugs and antitumor necrosis factor α antibodies promote mucosal healing4 but more than one-third of patients do not respond to these therapies, efficacy may wane with time and the use of these drugs can increase the risk of opportunistic infections and malignancies.5,6,7 Therefore, there is great interest in identifying new molecules/pathways that can be therapeutically targeted in CD.

Novel therapeutic compounds have been predicated on the hypothesis that CD results from an exaggerated immune response, occurring in genetically susceptible individuals, and directed against components of the bacterial flora.8 Such hyperimmune reactivity is in part dependent on the inability of the mucosal immune system to mount an effective counter-regulatory response.9,10 For example, in CD, there is a defective activity of the suppressive cytokine transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, due to high levels of Smad7, an intracellular protein that binds to the TGF-β1 receptor and prevents TGF-β1-driven signalling.11,12 Both T cells and non-T cells express high levels of Smad7 in CD tissue, and knockdown of Smad7 with a specific antisense oligonucleotide restores TGF-β1 activity, with the downstream effect of inhibiting inflammatory cytokine production.11

To inhibit Smad7 in the gut, we developed an antisense oligonucleotide-containing pharmaceutical compound, herein termed GED0301. Details of the Smad7 antisense oligonucleotide have been previously described.11 Briefly, GED0301 is a synthetic single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide in which the internucleotide linkages are modified to O,O-linked phosphorothioates to increase oligonucleotide stability. The oligonucleotide antisense matches the region 107–128 of the human Smad7 complementary DNA sequence and contains two CpG motifs which are chemically modified to avoid immunostimulatory effects. GED0301 is formulated as a solid oral dosage form. The formulation is protected by an external tablet coating made of pH (6.6–7.2)-dependent metacrylic acid polymers, which allow the antisense to transit through the stomach and proximal small intestine, and to be released only in the lumen of the terminal ileum and right colon. Preclinical studies confirmed that orally administered GED0301 reaches the gut, where it is taken up by epithelial and lamina propria cells and that a single administration of the oligonucleotide antisense reduced the mucosal expression of Smad7, enhanced TGF-β1-associated Smad2/3 phosphorylation and attenuated experimental colitis(ref. 13 and data not shown). Altogether, these data support the concept that Smad7 constitutes a molecular target for direct therapeutic interventions in CD.

Here, we provide results of a phase 1 clinical, open-label, dose-escalation study of GED0301 in patients with active CD, aimed at assessing the safety and tolerability of the drug.

Results

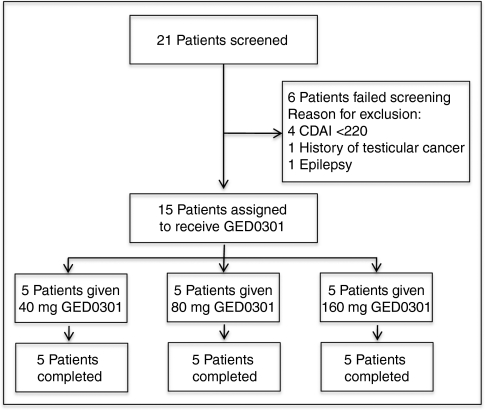

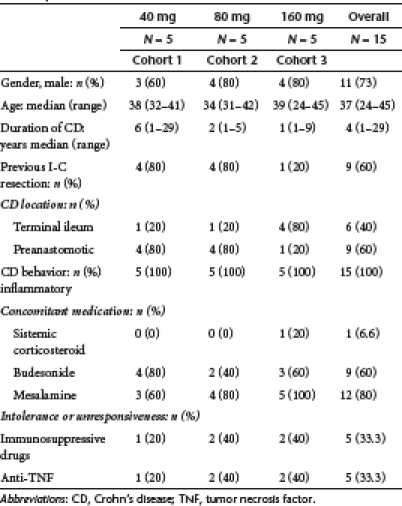

Figure 1 shows the trial profile. A total of 15 patients were enrolled into the trial. The demographic and clinical characteristic of patients are shown in Table 1. There was no significant differences among cohorts. However, patients of cohort 1 had a longer disease duration as compared with the other two cohorts, as well as history of intestinal resection was more frequent in patients of cohorts 1 and 2 as compared to patients of cohort 3. All 15 patients completed the 7-day treatment and the 84-day follow-up period.

Figure 1.

Trial profile. CDAI, Crohn's disease activity index.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristic of the 15 Crohn's disease patients.

Safety and pharmacokinetics

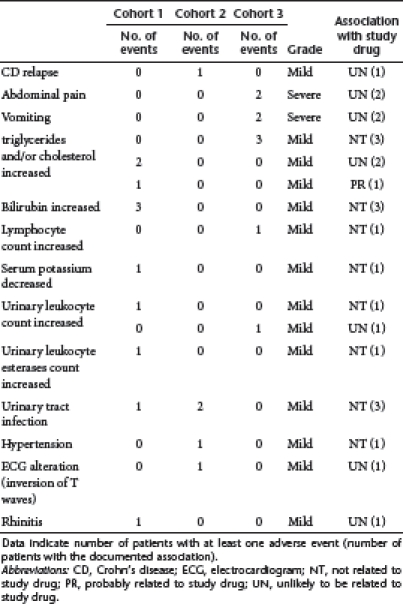

No serious adverse event was registered. Twenty-five adverse events (AE) were registered in 11 patients, with the most common events reported as mild (Table 2). Investigators rated AE as not related to treatment in 14 (56%) cases. Eleven out of these 14 AE, including laboratory abnormalities, were registered in 8 patients before drug administration. AE were considered unlikely to be related to study drug in 12 (48%) of cases and probably related to study drug in one case (4%). This was an increase in the serum triglycerides count during the administration of the study drug. There was no apparent dose–response relationship in treatment-emergent AE. One patient of cohort 2 had a mild relapse of the disease on day 84, while another one of the cohort 3 experienced two severe episodes of abdominal pain and vomiting which required a daily treatment with steroids. One patient treated with 80 mg/day experienced high diastolic pressure on day 1, just few minutes after GED0301 administration and T wave inversion (in precordial leads) on day 84. After carefully examination by cardiologists, both these AE were considered as secondary to the budesonide treatment received by the patient over the last months. An episode of allergic rhinitis was registered in one patient, with a history of allergic disease, on day 31. This AE resolved very quickly after a single administration of an antihistaminic compound.

Table 2. Adverse events registered during the study.

There were no consistent laboratory abnormalities or changes in vital signs noted in any patient during the study. No significant increase in the serum levels of complement factors was documented.

All the samples in the three cohorts yielded values below the lower limit of quantification, except one sample of a single patient from cohort 1 (patient 5, day 7, 6 hours), which gave a result of 11.2 ng/ml GED0301.

Changes in circulating cytokine-secreting T cells following GED0301 treatment

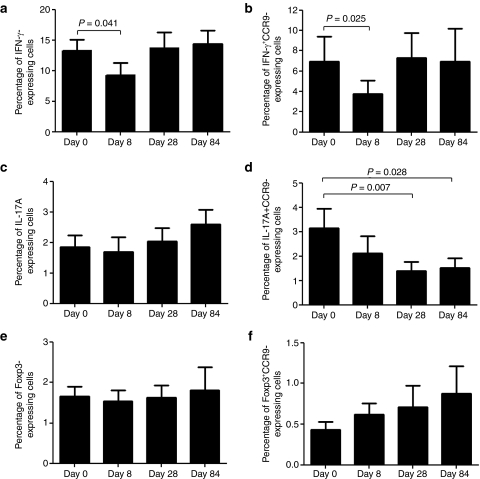

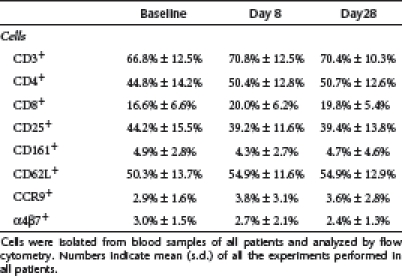

We next examined whether GED0301 treatment associates with changes in the fraction of inflammatory/counter-regulatory lymphocytes. We were not allowed to perform colonoscopy and collect biopsies from patients enrolled into this trial by the Ethics Committee. So, we restricted our analysis to blood cells and focused on various subsets of T cells. GED0301 treatment did not alter significantly the percentage of circulating CD3−, CD4−, CD8−, CD25−, CD161−, CD62L−, α4β7−, and CCR9+ cells (Table 3). Moreover, no significant change in the fraction of interleukin (IL)-17A+, IL-10+, and FoxP3+ cells was seen following GED0301 treatment (Figure 2 and data not shown). Similarly, no significant change in the percentages of interferon (IFN)-γ- and IL-17A-expressing α4β7+ cells and FoxP3-expressing CD103+ cells was seen after GED0301 administration (data not shown). In contrast, on day 8, GED0301 treatment associated with a significant reduction in the fraction of both IFN-γ-expressing cells and IFN-γ+ CCR9-expressing cells (Figure 2a,b). A significant decrease in the fraction of IL-17A+ CCR9-expressing cells was seen following GED0301 treatment but it was significant only at day 28 and 84 (Figure 2c,d). A slight but not significant increase in the fraction of FoxP3+ CCR9-expressing cells was seen at days 8 and 28 following GED0301 treatment (Figure 2e,f).

Table 3. Percentages of positive cells for the indicated markers at baseline and day 8 and day 28 after GED0301 treatment.

Figure 2.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from the 15 patients enrolled for the study at the indicated time points, stimulated as indicated in methods and then analyzed for the expression of (a) (IFN)-γ, (c) IL-17A, and (e) Foxp3 by flow cytometry. Additionally cells were costained with CCR9 antibody and (b) IFN- γ, (d) IL-17A, and (e) Foxp3. Data indicate mean ± SD of all experiments. IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin.

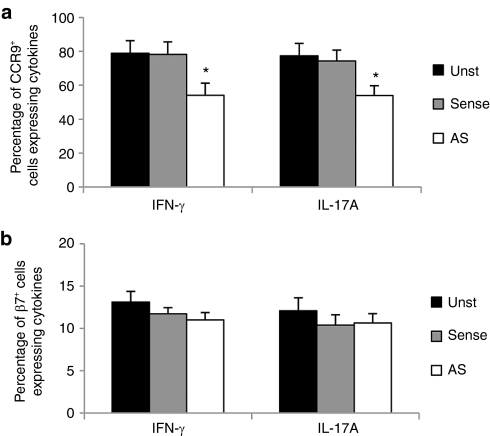

To determine whether GED0301 directly inhibits the expression of inflammatory cytokines in CCR9-positive cells, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) isolated from CD patients were cultured with GED0301 or control oligonucleotide and the fractions of cytokine-expressing CCR9-positive and β7-positive cells were then evaluated by flow cytometry. Treatment of CD PBMC with GED0301 (Smad7 antisense) significantly reduced the percentages of IFN- γ and IL-17A-expressing CCR9-positive cells (Figure 3a), while the fraction of cytokine-expressing β7-positive cells remained unchanged (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from five patients with active Crohn's disease (CD) who were not enrolled for the study and cultured with medium (unstimulated = Unst) or Smad7 sense or antisense (AS = GED0301). After 48 hours, the percentages of (a) CCR9± and (b) β7± cells expressing interferon 4(IFN)-γ or IL-17A were evaluated by flow cytometry. Data indicate mean ± SD of all experiments. *P ≤ 0.03. IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin.

Clinical response

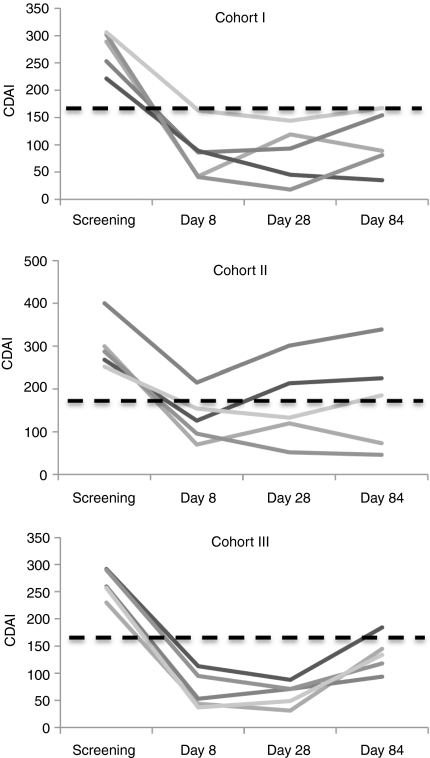

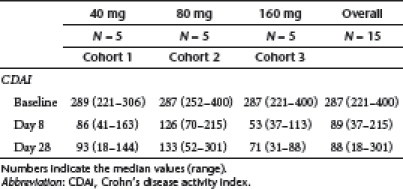

At enrolment, the median Crohn's disease activity index (CDAI) score of all patients was 287 (221–400) (Table 4). The median CDAI score was 289 (range 221–306) for patients of cohort 1, 287 (range 252–400) for patients of cohort 2 and 287 (range 221–400) for patients of cohort 3. At day 8, all 15 patients experienced a clinical response, as defined by a decrease in CDAI score >70 points (Table 4 and Figure 4). To obtain preliminary evidence of efficacy, a pooled analysis of all dose cohorts was initially performed. A significant decrease in CDAI score was seen from baseline to day 8 (P < 0.0001) (Table 4). At the same time point, clinical remission was registered in 12/15 (80%) of patients. In particular, 4/5 patients of cohort 1, 3/5 patients of cohort 2 and 5/5 patients of cohort 3 had a CDAI score <150 (Figure 4). At day 28, clinical response was evident in all 15 patients (Table 4 and Figure 4) and there was a significant decrease of CDAI score from baseline (P < 0.0001). Clinical remission was registered in 13/15 patients (86%) (5/5 of cohort 1, 3/5 of cohort 2 and 5/5 of cohort 3) (Figure 4). At day 84, the total CDAI score was significantly lower than that measured at baseline (Table 4, P < 0.0001) and 9/15 (60%) patients were still in remission. In particular, this was seen in 3 patients of cohort 1, 2 patients of cohort 2, and 4 patients of cohort 3 (Figure 4). A significant decrease of CDAI score from baseline to day 8, 28 and 84 was seen even when analysis was performed in each cohort (Table 4).

Table 4. CDAI values of patients in the three cohorts at baseline, and day 8, 28, and 84 after GED0301 treatment.

Figure 4.

Crohn's disease activity index (CDAI) values of Crohn's disease (CD) patients before (screening) and after (day 8, 28, and 84) GED0301 treatment. CDAI values are shown for each patient enrolled in the three separate cohorts. Dotted line indicates the CDAI value discriminating patients with active disease (>150) from those with inactive disease (<150).

Discussion

In recent years, the advent of tumor necrosis factor blockers has brought remarkable improvement in the management of moderate-to-severe, steroid-dependent/resistant CD. However, partial or non-clinical response to these compounds remains a significant issue, suggesting the necessity of novel therapeutic strategies. In previous studies we have shown that in CD there is a defective activity of TGF-β1 due to the abundance of Smad7, an inhibitor Smad.11,12 In vivo in mice, oral administration of Smad7 antisense oligonucleotide inhibits intestinal mucosal Smad7 expression, restores TGF-β1 signalling and dampens CD-like experimental colitis,13 thus suggesting that Smad7 is a tractable target in CD.

This is the first clinical trial to directly target Smad7 in humans. Data suggest that oral administration of Smad7 antisense oligonucleotide to patients with active CD is safe and well-tolerated. A diminished percentage of circulating inflammatory cytokine-secreting T cells with gut homing properties was also seen following GED0301 treatment.

GED0301 was well-tolerated as no serious adverse event was registered. The majority of AE were considered as mild and the only severe AE registered in 1 patient was considered as unrelated to study drug, because these AE occurred nearly 3 months later the end of the treatment. GED0301 has the same nucleotide sequence of the antisense oligonucleotide used in our preclinical studies in mice and monkeys (ref. 13 and data not shown), because Smad7 is homologous across species. Results of the present study confirm our previous data showing that at therapeutic doses GED0301 is not toxic.13

Oral administration of GED0301 associated with a significant decrease in the percentages of circulating IFN-γ – and IL-17A-expressing CCR9+ T cells and an increase, though not significant, of the fraction of Foxp3-expressing CCR9+ T cells. CCR9-expressing T cells are increased in the blood and intestinal lamina propria of CD patients, express an activated phenotype and produce elevated levels of IFN- γ and IL-17A following in vitro stimulation with anti-CD3 or IL-12/IL-18, thus supporting their proinflammatory nature.14,15 CCR9-expressing T cells are primed in secondary lymphoid organs, such as the gut-associated lymphoid tissue, one of the sites where the intestinal immune system recognizes, interacts and respond to luminal antigens.16 In these lymphoid districts, antigen-activated T cells acquire tissue specific homing receptors, such as CCR9, which allow them to migrate to various nonlymphoid tissue sites (i.e., small intestinal lamina propria). CCR9 binds CCL25, a chemokine highly produced in the CD small intestine; so interactions between CCR9 and CCL25 promote a selective recruitment of activated T cells from the blood to the small intestine.14,17,18 GED0301 was barely detectable in the plasma of only one patient, suggesting that the drug is not probably absorbed following oral administration. Thus, it is conceivable that the regulatory effect of GED0301 on CCR9-expressing T cells occurs not systemically but in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue, where the abundance of Smad7 could interfere with the ability of TGF-β1 to enhance CCR9 on T cells and shift the T cell balance toward the mucosal tissue-homing of regulatory T cells.19 We also show that in vitro treatment of CD PBMC with GED0301 significantly reduced the percentages of CCR9+ cells expressing IFN-γ and IL-17A, suggesting that changes in the fraction of these cells in vivo in CD patients are due to a direct effect of GED0301 on these cell types rather than reflecting fluctuations in disease activity.

Since this study was aimed at assessing safety and tolerability of GED0301 in man, it was designed without placebo. Despite this limitation, we think it is fair to point out the clinical benefit documented in patients taking GED0301. Indeed, the percentages of patients reaching clinical response (100%) and remission (86%) in our study were markedly higher than those expected to be obtained with placebo treatment (≤30%).20,21 Clinical benefit induced by 7-day treatment persisted over the time and some patients were still in remission at day 84. We do not yet known how long the oligonucleotide can persist in the human inflamed intestine, but data generated in mice indicate that the orally administered Smad7 antisense oligonucleotide disappears very quickly from the gut.13 It is thus unlikely that maintenance of remission seen at day 84 is due to a persistent activity of GED0301. In this context, it is noteworthy that our results are consistent with previous studies showing that remission induced in CD patients with traditional and biological drugs can be maintained for a long period of time after the cessation of the treatment.2,3,4 We cannot exclude the possibility that the hospitalization and care of each patient, including a 24-hour assistance by a dedicated nurse, repeated clinical and hematochemical assessments, and improved medication compliance could have influenced the general well-being of patients and the CDAI score.

The doses of GED0301 used in this study were selected taking into account our previous work showing that a single dose of 125 µg/mouse Smad7 antisense oligonucleotide is safe and therapeutic in colitic mice.13 The group sizes of the present study were too small to appreciate any dose response. However, a greater response in terms of CDAI decrease was seen in the high-dose cohort. Baseline variables of patients in the three cohorts did not differ significantly, thus excluding the possibility that patients of cohort 3 had a less severe disease. By contrast, 4/5 patients of cohort 3 had previously received no surgical resection likely due to their shorter duration of the disease. It is thus tempting to speculate that patients with early onset CD might have the better response to GED0301.

In conclusion, the results of this exploratory phase 1, testing a novel compound for active CD, are encouraging in terms of safe and tolerability. Although GED0301 treatment associates with reduction of signs and symptoms of CD, the ultimate efficacy profile of this approach will require confirmation in appropriately designed placebo-controlled clinical trials. Similarly, further work is needed to evaluate whether long-term therapy with GED0301 can enhance the risk of fibrosis as TGF-β1 is one of the most powerful inducer of fibrogenesis in many organs.22,23

Materials and Methods

Participants. Patients aged 18–45 years with a confirmed diagnosis of CD based on standard radiologic, endoscopic, and histologic criteria were eligible for enrolment. Enrolment criteria included moderate-to-severe active disease at screening, which was defined as CDAI >220.24 CDAI score is used for serially quantifying degree of sickness in clinical trials of CD. It is based on eight clinical variables (i.e., number of liquid stools/day, abdominal pain, general well-being, occurrence of extraintestinal manifestations, use of antidiarrheal drugs, presence of abdominal masses, hematocrit, and body weight), each of whom is coded so that 0 corresponds to good health and increasing positive values correspond to greater degrees of sickness. CDAI values ≤150 generally indicate quiescent disease and those ≥450 generally reflect extremely severe disease.

Patients had an inflammatory phenotype and were steroid-dependent and/or resistant. Definition of steroid dependence and resistance was described elsewhere.14 Concomitant steroid therapy was maintained during the 7-day treatment period. Patients were receiving no treatment with antitumor necrosis factor -α, other biologics, immunosuppressive drugs (e.g., azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate) in the 90 days prior the enrolment. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, smokers, had CD involving the stomach and/or the proximal small intestine and/or the transverse and/or left colon. Patients were also excluded if they had local complications (e.g., abscesses, strictures, and fistulae) or had received proctocolectomy. Evidence of any active or recent infections or a history of malignancy were also exclusion criteria. Further exclusion criteria included any of the following alterations: partial thromboplastin time >1.5 upper limit of normality; platelet count ≤100,000/mm3; serum creatinine >1.5 ULN; total bilirubin >1.5 ULN (except Gilbert syndrome); transaminases >1.5 ULN; QTc interval >450 msec for males and >470 msec for females. Female of childbearing potential used appropriate contraception. The study was conducted at the Tor Vergata University Hospital (Rome, Italy).

All patients gave written and informed consent at the time of enrolment. The protocol was approved by ethics committees at local centre and at the Istituto Superore di Sanità (Rome, Italy) and notified to the appropriate local regulatory authority. The study was done in accordance with the International Conference on harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice and with the Helsinki Declaration.

End points and assessments. This study was aimed at assessing the safety and tolerability of GED0301 in patients with active CD. The trial was a phase 1 clinical, open-label, dose-escalation study with three treatment arms of 40 mg (N = 5 patients, cohort 1), 80 mg (N = 5 patients, cohort 2), or 160 mg (N = 5 patients, cohort 3) GED0301 given orally once a day for 7 consecutive days. Upon meeting entry criteria, patients were hospitalized and the day after they received the first dose of GED0301 at 8 before breakfast. Hospitalization was required to accurately monitor the safety profile of the study drug. Patients had no specific dietary restriction.

Safety assessments were performed daily and included analysis of AE, changes in vital signs, standard laboratory tests. An enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay was used to monitor complement activation (i.e., analysis of Bb, C5a, and C3a). All the above laboratory determinations were performed by the local laboratory. One patient per time was hospitalized, and during and at the end of the treatment (day 8), safety data were reviewed by a formally constituted safety assessment committee before enrol and treat the subsequent patient.

Patients were excluded from the study at any time after enrolment if they experienced a significant increase in CD symptoms. Additional reasons for study discontinuation included a serious adverse event or a severe AE or toxicity requiring discontinuation of GED0301 treatment.

For pharmacokinetic analysis, plasma samples were collected on day 1 and 7 at 0, 2, 6, 12, 24-hours postdosing and stored at – 20 °C. GED0301 was measured in plasma samples by Charles River (Edinburgh, UK) using a validated in-house method, which involves a hybridization/ligation reaction between complementary oligonucleotides. The lower limit of quantification was 7.5 ng/ml.

Changes in CDAI score were also registered to obtain preliminary evidence of efficacy of GED0301. To this end, clinical response was defined as decrease from baseline CDAI score of >70 points, while remission was defined as CDAI score <150.

Patients were discharged from hospital on day 8, and they returned for clinic visit and blood sample collection at days 28 and 84. Patients were requested to contact the referral center if any AE or clinical relapse occurred before the scheduled visits.

Cell cultures flow-cytometry analysis. All the reagents were from Sigma (Milan, Italy) unless specified. Peripheral blood was obtained from all 15 CD patients after informed consent was provided. Samples were harvested into heparinized tubes and processed immediately. PBMC were obtained by density-gradient centrifugation, washed three times in cold phosphate-buffered saline, and either used to assess cell surface markers by flow cytometry or cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) (complete medium) (Life Technologies-GibcoCRL, Milan, Italy). PBMC, isolated from further five active steroid-dependent CD patients, who were not enrolled into the trial, were resuspended in X-vivo serum-free culture medium (Lonza, Verviers, Belgium), supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 U/ml), and cultured in the presence or absence of Smad7 antisense (GED0301) or sense oligonucleotide (2 µg/ml) for 48 hours. Both Smad7 antisense and sense oligonucleotides were combined with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For flow-cytometry analysis, PBMC were stained with the following antibodies: anti-CD4-PerCP (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), anti-CD3-PerCP (BD Biosciences), anti-CD8-allophycocyanin (BD Biosciences), anti-CD103-allophycocyanin (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), anti-CD161-APC (BD Biosciences), anti-CD-62L-APC (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), anti-CD25-PE (eBioscience), anti-β7-PE (BD Biosciences), anti-CCR9-APC (BD Biosciences). To assess the intracellular expression of FoxP3, PBMC were permeabilized with 0.5% saponin in 1% bovine serum albumin FACS buffer and stained intracellullarly with anti-FoxP3-PE (eBioscience). To examine cytokine-expressing cells, PBMC were cultured in complete medium with Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (10 ng/ml), ionomycin (1 µg/ml), and brefeldin A (10 µg/ml; eBioscience) for 5 hours, and then assessed by flow cytometry. All antibodies were used at 1:50 final dilution. Appropriate isotype-matched controls from BD Biosciences were included in all of the experiments. Cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur cytometer and Cell-QuestPro software.

Statistical analysis. Differences between groups were compared using the Student's t-test, Wilcoxon test or the Mann–Whitney U test. This study is registered with the EudraCT Number: 2009-012465-66 (http://eudract.emea.europa.eu/index.html).

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Giuliani SpA, Mila, Italy, and in part by a grant (G.M.) from the Broad Medical Research Foundation (IBD-0301R). The study was sponsored and coordinated by Giuliani Spa (Milan, Italy). The principal investigator and co-investigators obtained patients data for the study and the sponsor was responsible for data collection and analysis. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data and takes full responsibility for the veracity of the data and statistical analysis. G.M. has filed a patent related to the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases with Smad7 antisense oligonucleotides, while the remaining authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Kaser A, Zeissig S., and, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:573–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R, IBD Section of the British Society of Gastroenterology et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571–607. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger D., and, Travis S. Conventional medical management of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1827–1837.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, SONIC Study Group et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Deltenre P, de Suray N, Branche J, Sandborn WJ., and, Colombel JF. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn's disease: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:644–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Irving PM, Marinaki AM., and, Sanderson JD. Review article: malignancy on thiopurine treatment with special reference to inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:119–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Horin S., and, Chowers Y. Review article: loss of response to anti-TNF treatments in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:987–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier RJ., and, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald TT., and, Monteleone G. Immunity, inflammation, and allergy in the gut. Science. 2005;307:1920–1925. doi: 10.1126/science.1106442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloy KJ., and, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nature10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone G, Kumberova A, Croft NM, McKenzie C, Steer HW., and, MacDonald TT. Blocking Smad7 restores TGF-beta1 signaling in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:601–609. doi: 10.1172/JCI12821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone G, Boirivant M, Pallone F., and, MacDonald TT. TGF-beta1 and Smad7 in the regulation of IBD. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1 Suppl 1:S50–S53. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boirivant M, Pallone F, Di Giacinto C, Fina D, Monteleone I, Marinaro M.et al. (2006Inhibition of Smad7 with a specific antisense oligonucleotide facilitates TGF-beta1-mediated suppression of colitis Gastroenterology 1311786–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis KA, Prehn J, Moreno ST, Cheng L, Kouroumalis EA, Deem R.et al. (2001CCR9-positive lymphocytes and thymus-expressed chemokine distinguish small bowel from colonic Crohn's disease Gastroenterology 121246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saruta M, Yu QT, Avanesyan A, Fleshner PR, Targan SR., and, Papadakis KA. Phenotype and effector function of CC chemokine receptor 9-expressing lymphocytes in small intestinal Crohn's disease. J Immunol. 2007;178:3293–3300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TT., and, Monteleone G. IL-12 and Th1 immune responses in human Peyer's patches. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:244–247. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01892-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agace WW. T-cell recruitment to the intestinal mucosa. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:514–522. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora JR., and, von Andrian UH. T-cell homing specificity and plasticity: new concepts and future challenges. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SG, Lim HW, Andrisani OM, Broxmeyer HE., and, Kim CH. Vitamin A metabolites induce gut-homing FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:3724–3733. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su C, Lichtenstein GR, Krok K, Brensinger CM., and, Lewis JD. A meta-analysis of the placebo rates of remission and response in clinical trials of active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1257–1269. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renna S, Cammà C, Modesto I, Cabibbo G, Scimeca D, Civitavecchia G.et al. (2008Meta-analysis of the placebo rates of clinical relapse and severe endoscopic recurrence in postoperative Crohn's disease Gastroenterology 1351500–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawinkels LJ., and, Ten Dijke P. Exploring anti-TGF-ß therapies in cancer and fibrosis. Growth Factors. 2011;29:140–152. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2011.595411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santibañez JF, Quintanilla M., and, Bernabeu C. TGF-ß/TGF-ß receptor system and its role in physiological and pathological conditions. Clin Sci. 2011;121:233–251. doi: 10.1042/CS20110086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW., and, Kern F., Jr Development of a Crohn's disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]