Abstract

Increasing evidences show that immune response affects the reparative mechanisms in injured brain. Recently, we have demonstrated that CD4+T cells serve as negative modulators in neurogenesis after stroke, but the mechanistic detail remains unclear. Glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor (GITR), a multifaceted regulator of immunity belonging to the TNF receptor superfamily, is expressed on activated CD4+T cells. Herein, we show, by using a murine model of cortical infarction, that GITR triggering on CD4+T cells increases poststroke inflammation and decreases the number of neural stem/progenitor cells induced by ischemia (iNSPCs). CD4+GITR+T cells were preferentially accumulated at the postischemic cortex, and mice treated with GITR-stimulating antibody augmented poststroke inflammatory responses with enhanced apoptosis of iNSPCs. In contrast, blocking the GITR–GITR ligand (GITRL) interaction by GITR–Fc fusion protein abrogated inflammation and suppressed apoptosis of iNSPCs. Moreover, GITR-stimulated T cells caused apoptosis of the iNSPCs, and administration of GITR-stimulated T cells to poststroke severe combined immunodeficient mice significantly reduced iNSPC number compared with that of non-stimulated T cells. These observations indicate that among the CD4+T cells, GITR+CD4+T cells are major deteriorating modulators of poststroke neurogenesis. This suggests that blockade of the GITR–GITRL interaction may be a novel immune-based therapy in stroke.

Keywords: GITR, Fas, T-cell, neural stem cell, ischemia

Brain injury induces acute inflammation, thereby exacerbating poststroke neuronal damage.1, 2, 3, 4 Although central nervous system (CNS) is known for its limited reparative capacity, inflammation is a strong stimulus for reparative mechanisms including activation of neurogenesis. However, the latter results in low survival of newly generated neural stem cells.5 These findings indicate the relevance of endogenous regulatory and/or environmental factors for survival and differentiation of neural stem cells.

In a murine model of cerebral ischemia, we have detected neural stem/progenitor cells induced by ischemia (ischemia-induced neural stem/progenitor cells; iNSPCs) in the poststroke cerebral cortex.6 More recently, we have observed spontaneous accelerated repair in severe combined immunodeficient mice (SCID) compared with immunocompetent wild-type controls,7 and have demonstrated that CD4+T cells serve as negative regulators in the survival of iNSPCs.8 Together with previous reports supporting the importance of the role of T cells in regulating poststroke inflammation1, 2, 9 and functional recovery,1, 10, 11 these findings emphasize on the link between CD4+T cells and survival of iNSPCs. However, the mechanistic details and the subpopulation of CD4+T cells responsible for acting as negative regulators in CNS repair remain unclear.

Glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor (GITR)-related protein that was originally cloned in a glucocorticoid-treated hybridoma T-cell line12 is a protein belonging to the TNF receptor superfamily. It is expressed at basal levels in responder resting T cells, with CD4+T cells including CD4+CD25+T cells (regulatory T cell, Treg) having a higher GITR expression than CD8+T cells.13 When the T cells are activated, GITR is strongly upregulated in responder CD4+T cells. In this situation, the stimulatory effect of responder T cells was more activated13, 14 and the suppressing effect of Treg was completely abrogated,13 leading to a more enhanced immune/inflammatory response.15 In the CNS, it has been reported that blocking of the GITR–GITR ligand (GITRL) interaction protected spinal cord injury from the inflammatory response,16 whereas GITR triggering worsened experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis while stimulating autoreactive CD4+T cells.17 These observations lead us to hypothesize that GITR triggering on T cells may serve as a negative regulator for CNS repair after cerebral infarction.

In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that GITR triggering on T cells following ischemic stroke enhanced poststroke inflammation and cell death of iNSPCs. Administration of GITR–Fc fusion protein markedly suppressed these responses. In addition, GITR-triggered T cells directly induced apoptosis of iNSPCs in vitro. Our current results show that activated GITR+T cells acted as negative modulators for CNS restoration, indicating that blockade of the GITR–GITRL interaction can be a novel strategy for treating ischemic stroke.

Results

Infiltration of CD4+GITR+T cells into the ischemic cortex after stroke

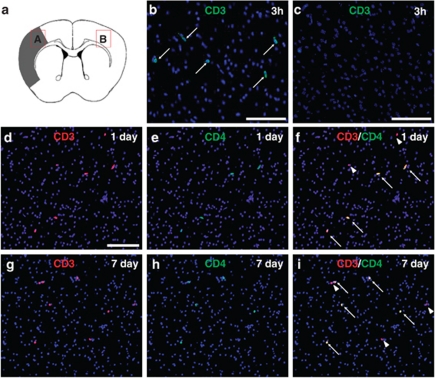

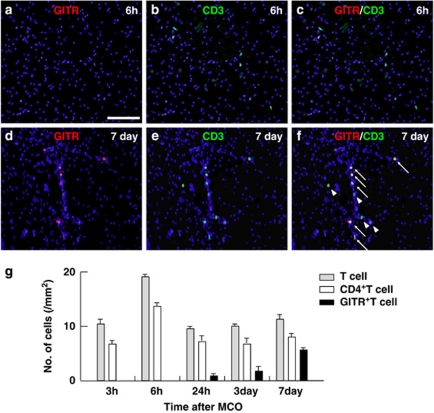

Immunohistochemistry (Figures 1a–c) revealed that CD3+ cells (T cells) appeared to infiltrate the ischemic region as early as 3 h after stroke (Figure 1b) and were observed continuously during the poststroke period (Figures 1d and g). The T cells were rarely observed at nonischemic ipsilateral or contralateral cortex (Figure 1c). Most T cells in the ischemic region (∼70% of T cells) were CD4 positive (Figures 1d–i), indicating that CD4+T cells predominantly infiltrate the poststroke cortex. However, GITR-positive cells were not found in the ischemic region at 6 h after stroke (Figure 2a), whereas a number of T cells were detected at the same region (Figures 2b and c). This indicates that GITR was not expressed in the infiltrated T cells at early poststroke period. GITR-expressing cells started to appear at 24 h after stroke and gradually increased in number. At 7 days post stroke, a number of CD3+T cells co-express GITR (Figures 2d–f). Calculating the number of infiltrated T cells in serial brain sections revealed that ∼65% of CD4+T cells were GITR positive, indicating that GITR+T cells predominantly occupied the subset of CD4+T cells at the late poststroke period. Semiquantitative analysis for the number of CD4+T or GITR+ cells in the ischemic region is shown in Figure 2g.

Figure 1.

T-cell infiltration into the ischemic area of the poststroke brain. Immunohistochemistry for CD3+ cells (T cells; (a) B: ischemic area and C: contralateral cortex) and CD4+T cells (d–i) infiltrated into the postischemic cortex 3 h (b and c), 1 day (d) and 7 days (g) after stroke. CD3+ T cells were positive for CD4 1 day and 7 days (arrows, d and g: CD3; e and h: CD4; f and i: merged, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI) after stroke. Arrowheads indicate CD4− T cells (f and i). (b–i) Scale bar: 100 μm

Figure 2.

GITR-positive T-cell infiltration into the ischemic area of the poststroke brain. Immunohistochemistry for GITR+T (a–f) cells infiltrated into the postischemic cortex 6 h (a–c) and 7 days (d–f) after stroke. The T cells were negative for GITR at 6 h (a: GITR; b: CD3; c: merged), but appeared to be positive for GITR at 7 days (arrows, d: GITR; e: CD3; f: merged). Arrowheads indicate GITR− T cells (f). (a) Scale bar: 100 μm. (g) Cells expressing CD3 (gray bars), CD4 (white bars) or GITR (black bars) 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 3 days or 7 days after stroke were quantified. Results displayed are representative of three repetitions of the experimental protocol

Predominant accumulation of CD4+GITR+T cells at the ischemic cortex after stroke

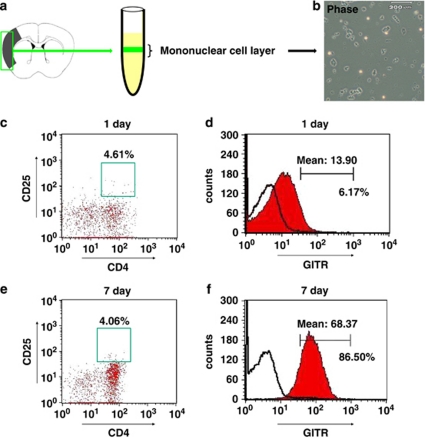

To confirm the enhanced expression of GITR on CD4+T cells, we assessed the subset of T cells by FACS analysis using the cells extracted from the ischemic cortex18 (Figures 3a and b). Consistent with the previous report, the brain extract contained substantial amount of mononuclear cells (Figure 3b) and FACS analysis detected a distinct subset of lymphocytes that had infiltrated the ischemic cortex (Figures 3c–f). We detected about 20% CD4+T cells extracted from the infarcted brain tissue. We at first gated CD3+ cells and then analyzed CD25 to characterize the corresponding CD4+T cells. GITR was analyzed on CD3+CD4+ cells. No significant upregulation of CD25 on T cells was observed at days 1 and 7 after stroke (Figures 3c and e: 4.61% at day 1 and 4.06% at day 7). However, the percentage of GITR+T cells was increased from 6.17 to 86.50%, and the surface expression of GITR on CD4+T cells at day 7 was significantly increased compared with that at day 1 (from 13.90 to 68.37 in mean channel value; Figures 3d and f), indicating enhanced expression of GITR as an activation marker for CD4+T cells.

Figure 3.

The analysis for the subpopulation of infiltrated cells in the ischemic area with FACS. (a) The ischemic tissue of the brain 7 days or 1 day after stroke was isolated and pressed through a cell strainer, and was separated by Ficoll-paque plus centrifugation. The extract contains lymphocyte-like mononuclear cells, which were observed under phase-contrast microscope. (b) FACS analysis for the subset of T cells that infiltrated the ischemic cortex was performed. The acquired lymphocytes were analyzed for CD4+ and CD25+ on CD3+ cells 1 day (c) and 7 days (e), and for GITR on CD3+CD4+ cells 1 day (d) or 7 days (f) after stroke. The percentage of CD25+ cells was evaluated in the total T cells (CD3+ cells), and that of GITR+ cells was evaluated in CD4+ T (CD3+CD4+) cells extracted from the infarcted brain tissue. The mean channel values were displayed for GITR in the CD3+CD4+ cells. (d and f) Filled histogram represents GITR expression and open histogram represents isotype control

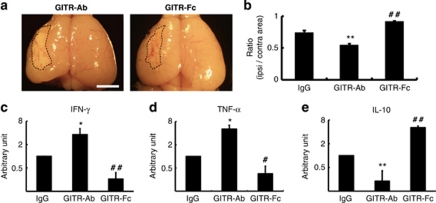

Effects of GITR triggering on cerebral infarction

Given that GITR triggering was involved in cerebral ischemic injury, we decided to examine whether stimulation or inhibition of GITR triggering affects cerebral infarction by using the same stroke model. Mice were treated with anti-GITR agonistic antibody (GITR–Ab:DTA-1), GITR–Fc fusion protein (blocking the GITR–GITRL interaction) or control IgG at 3 h and 3 days after stroke. The brain was then removed 30 days after stroke. The size of infarction in mice treated with GITR–Ab was apparently larger than that of mice treated with GITR–Fc (Figure 4a). Further analysis of the volume of each hemisphere based on brain sections demonstrated a significant decrease in the poststroke brain volume in GITR–Ab mice, and a significant increase in that of GITR–Fc mice, compared with control mice (Figure 4b). These findings indicated that ischemic injury was enhanced by GITR triggering, while ameliorated by its blocking.

Figure 4.

Effects of GITR triggering on the poststroke brain volume and cytokine expression. (a) On day 30 after stroke, brains of mice treated with either GITR–Ab or GITR–Fc were evaluated grossly. Areas of hatched line indicate infarct area. (b) Ipsilateral and contralateral cerebral hemisphere volume was calculated by integrating coronally oriented ipsilateral and contralateral cerebral hemisphere area. Involution of ipsilateral cerebral hemisphere volume calculated as (ipsilateral/contralateral cerebral hemisphere volume) confirmed a significant difference in brain volume in the poststroke hemisphere comparing the groups. (b) n=5 for each experimental group. (a) Scale bar: 2 mm. The expression of IFN-γ (c), TNF-α (d) and IL-10 (e) in the ischemic tissue on day 7 after stroke was detected by quantitative real-time PCR. The relative expression of mRNAs was represented as arbitrary unit, which was set at the level of the expression of the gene equal to 1 in the IgG-treated group using a logarithmic scale. The significance among the treatments was calculated from the relative level of mRNA expression. (c–e) n=4 for each experimental group. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, GITR–Ab-treated mice versus control IgG-treated mice; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01, GITR–Fc-treated mice versus control IgG-treated mice

Effects of GITR triggering on poststroke inflammation

We had until then attempted to determine how the triggering of GITR could affect poststroke inflammation. As several studies have reported that multiple cytokines modulate CNS inflammation,2, 3, 19 the levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-10 were analyzed using quantitative real-time PCR in mice 7 days after stroke. The alteration of mRNA levels of these cytokines within the ischemic region was confirmed (Figure 4c–e). GITR–Ab treatment resulted in a significant elevation of IFN-γ (P<0.05) and TNF-α (P<0.05) levels, and a significant decrease in the IL-10 level (P<0.01) compared with the control IgG treatment. In contrast, treatment with GITR–Fc showed a significant decrease in IFN-γ (P<0.01) and TNF-α levels (P<0.05), and a significant increase in IL-10 level (P<0.01) compared with the control. These data indicated that GITR triggering largely affected cerebral ischemic injury by changing the level of poststroke inflammation (enhancing proinflammatory cytokines and suppressing anti-inflammatory cytokines).

Effects of GITR triggering on survival/death of neural stem/progenitor cells

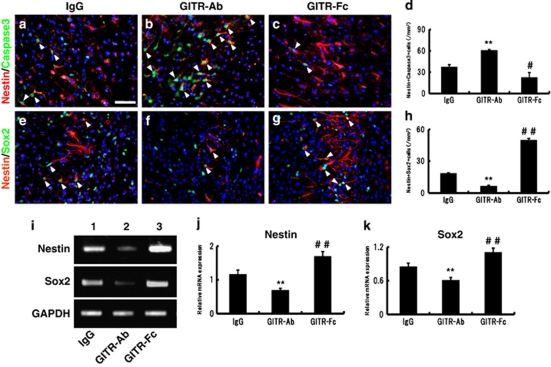

Inflammation is known not only as a deteriorated factor of cerebral injury but also as a strong stimulator of neurogenesis. As the current study has proved that GITR triggering can regulate the inflammatory response,15, 17 we assessed the GITR–GITRL interaction, which may contribute to neurogenesis in the infarction area. Because we had previously showed that iNSPCs could contribute to poststroke neurogenesis and that cortical neurogenesis is related to the development of the iNSPCs,8, 20, 21 the effects of GITR–Ab or GITR–Fc on survival/death of iNSPCs were investigated by using immunohistochemistry for nestin and active caspase-3 on the ischemic brain sections. The nestin-positive iNSPCs were observed at the border of the infarction as well as in the ischemic core 7 days after stroke (see Supplementary Figure 1B, red, nestin) as described.6, 8, 20 Control IgG-treated mice appeared to have abundant nestin and active caspase-3 double-positive cells (Figure 5a, red, nestin; green, caspase-3). The administration of GITR–Ab increased the number of nestin/caspase-3 cells (Figure 5b), whereas that of GITR–Fc decreased it (Figure 5c). The number of activated caspase-3-positive iNSPCs was significantly different among the three groups (Figure 5d; **P<0.01, GITR–Ab versus control IgG; #P<0.05, GITR–Fc versus control IgG). These findings indicate that GITR triggering induced, whereas its blocking suppressed, apoptosis of iNSPCs.

Figure 5.

Effects of GITR–Ab or GITR–Fc on survival/death of neural stem/progenitor cells. (a–d) Co-expression of nestin (red) and active caspase-3 (green; arrowheads) was investigated 3 days after stroke at the border of the infarction. Compared with the control IgG-treated mice (a), GITR–Ab-treated mice showed an increased number of nestin/caspase-3-positive cells (b), whereas GITR–Fc-treated mice showed fewer co-expressing cells (c). (e–h) Co-expression of nestin (red) and Sox2 (green; arrowheads) was investigated 7 days after stroke. Few cells co-expressing nestin and Sox2 were observed in GITR–Ab-treated mice (f), whereas a number of nestin/Sox2-co-expressing cells were observed in GITR–Fc-treated mice (g). The number of nestin/caspase-3 cells (d) and nestin/Sox2 cells (h) at each period was significantly different on comparing the groups. (d) n=3 and (h) n=4 for each experimental group. (i–k) Expression of nestin or Sox2 was detected by conventional RT-PCR in the ischemic tissue on day 7 (i). Compared with the control IgG-treated mice (first lane), GITR-treated mice showed decreased expression of nestin or Sox2 (second lane), whereas GITR–Fc-treated mice showed increased expression (third lane). The relative expression was significantly different on comparing the groups (j: nestin; k: Sox2). (j) n=4 and (k) n=5 for each experimental group. (a) Scale bar: 100 μm. **P<0.01, GITR–Ab-treated mice versus control IgG-treated mice; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01, GITR–Fc-treated mice versus control IgG-treated mice

To provide further support for our hypothesis that GITR triggering participates in iNSPC-death/survival, expressions of nestin and Sox2 (SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 2), neural stem cells markers,22 were assessed by immunohistochemistry (Figures 5e–h). Seven days after stroke, a number of nestin-positive cells express Sox2, especially at the border of infarction (Supplementary Figures 1A–D). The administration of GITR–Ab significantly decreased the number of nestin/Sox2 double-positive cells (Figures 5f and h; P<0.01 versus control IgG), whereas the administration of GITR–Fc increased them (Figures 5g and h; P<0.01 versus control IgG). These findings were confirmed by conventional reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (Figures 5i–k) using mRNA extracted from the infarcted cortex (Figure 5i). Relative expressions of nestin and Sox2 were attenuated by GITR–Ab treatment, and enhanced by GITR–Fc treatment (Figures 5j and k; P<0.01, among the three groups).

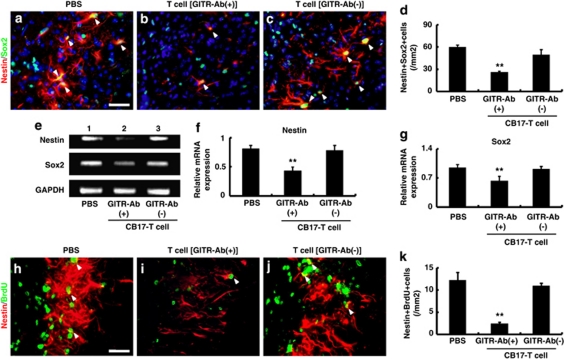

Effects of GITR-stimulated T cells on survival/death of neural stem/progenitor cells

As the ischemic insult enhanced the expression of GITR on infiltrated CD4+T cells (Figures 1, 2, 3) and GITR triggering disrupted iNSPCs in poststroke mice (Figure 5), we next investigated whether GITR-triggered, activated CD4+T cells could affect survival/death of iNSPCs. Activation of CD4+T cells by ligation of GITR has been reported previously,17 and we also confirmed enhanced expression of GITR on CD4+T cells by GITR–Ab (DTA-1; see Figure 8d; lanes 3, 4). Initially, to confirm infiltration of the administered T cells into the ischemic area, T cells extracted from the green fluorescence protein-transgenic (GFP-Tg) mice were injected into SCID mice 2 days after stroke as described previously.7, 20 Five days after administering, the GFP-positive T cells migrated selectively into the infarction area of the poststroke brain (Supplementary Figure 2). Next, we injected T cells of CB-17 mice (either stimulated or non-stimulated by GITR–Ab) as described above, and examined the expressions of nestin/Sox2 double-labeled cells 5 days after injection by immunohistochemistry (Figures 6a–d). In accordance with our previous report,8 poststroke SCID mice with PBS injection (control) expressed a greater number of nestin/Sox2-positive iNSPCs than CB-17 mice (compare Figure 6d with Figure 5h). The administration of GITR-stimulated T cells significantly decreased the number of nestin/Sox2 cells (Figures 6b and d; P<0.01), whereas non-stimulated T cells had no significant effect (Figures 6c and d). These findings were confirmed by conventional RT-PCR analysis (Figure 6e). Relative expressions of both nestin and Sox2 were attenuated by administration of GITR-stimulated T cells but not by non-stimulated T cells (Figures 6f and g). The proliferation of iNSPCs was also evaluated by labeling of nestin-positive cells with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), as per a previous report.8 GITR-stimulated T cells significantly decreased the number of BrdU-labeled nestin-positive cells compared with PBS treatment as a control (Figures 6i and k; P<0.01), whereas non-stimulated T cells had no significant effect (Figures 6j and k). These findings indicate that GITR-triggered, activated CD4+T cells, but not non-stimulated T cells, affect survival/death of iNSPCs after stroke.

Figure 6.

Effects of administration of T cells triggered by GITR on survival/death of neural stem/progenitor cells. (a–d) Co-expression of nestin (red) and Sox2 (green; arrowheads) was investigated 7 days after stroke in SCID mice, which were injected with T cells. Compared with the PBS-injected control mice (a), mice treated with GITR-stimulated T cells showed significantly less nestin/Sox2-positive cells (b), whereas mice treated with non-stimulated (control-IgG stimulated) T cells showed no difference compared with the control (c). (d) n=6, 3 and 3 for PBS-, GITR-stimulated T cell and non-stimulated T cell-treated groups, respectively. Expression of nestin or Sox2 detected by conventional RT-PCR in the ischemic tissue on day 7 (e) was significantly decreased after treatment with GITR-stimulated T cells (e: second lane) compared with control (PBS; e: first lane) or non-stimulated T-cell treatment (e: third lane; f: nestin; g: Sox2). (f and g) n=5 for each experimental group. (h–k) The number of proliferated neural stem/progenitor cells evaluated with anti-nestin (red) and anti-BrdU (green) antibodies (arrowheads) on day 7 was significantly decreased after treatment with GITR-stimulated T cells (i), compared with control (h) or non-stimulated T cell-treatment (j). Quantitative analysis confirmed the decreased number of nestin/BrdU-positive cells in GITR-stimulated T-cell-treated mice, compared with the other two groups (k; n=5 for each experimental group). **P<0.01 versus PBS- or non-stimulated T cell-treated (GITR–Ab(−)/CB-17 T cell) mice. (a and h) Scale bar: 50 μm

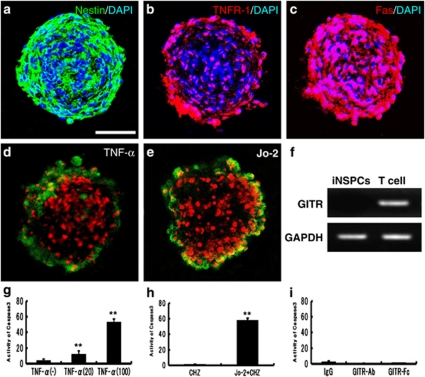

In vitro effects of TNF-α and Fas ligand on apoptosis of neural stem/progenitor cells

To determine how activated CD4+T cells ligated by GITR affect survival/death of iNSPCs, a cell death assay was performed using cultured neurospheres consisting of iNSPCs (Figure 7a). It is well known that some neural stem/progenitor cells undergo apoptosis, with expression of multiple cell death signals such as TNF receptor-1 (TNFR-1)23 and Fas.8 Consistent with these studies, we confirmed expression of TNFR-1 (Figure 7b) and Fas (Figure 7c) on iNSPC neurospheres. The neurospheres were incubated with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing TNF-α or agonistic Fas antibody (Jo-2) for 24 h, and their apoptosis was analyzed by Annexin V staining and active caspase-3 assay. As expected, TNF-α induced apoptosis of neurosphere cells (Figure 7d; green: Annexin V, red: PE). The activity of caspase-3 in the apoptotic neurosphere was increased dose dependently by TNF-α (Figure 7g). Jo-2 also induced apoptosis of neurospheres (Figure 7e), with a significant increase in caspase-3 activity (Figure 7h). Because iNSPCs neurosphere do not express GITR (Figure 7f), it is not likely that GITR signaling regulates death-receptor-induced apoptosis directly in iNSPCs. Accordingly, neither GITR–Ab nor GITR–Fc activated caspase-3 on the neurospheres (Figure 7i). These findings suggest that the death signaling pathway may be stimulated either directly or indirectly by activated CD4+T cells ligated by GITR. Moreover, these results also prove that the triggering of GITR directly have no effect on apoptosis of iNSPCs.

Figure 7.

Involvement of death factors in apoptosis of iNSPCs neurospheres. In neurospheres obtained from the ischemic areas of poststroke mice, nestin (green; a), TNFR-1 (red; b) and Fas (red; c) were virtually observed (DAPI, blue). Incubation with TNF-α (d) or Jo-2 (e) induced collapse of cell clusters with expression of a marker of apoptotic cell death, anionic phosphatidylserine visualized with Annexin V staining (green). (f) GITR was not expressed on iNSPCs neurosphere. (g) Incubation with TNF-α increased the activity of caspase-3 in neurospheres in a dose-dependent manner. Jo-2 also increased the activity (h), but neither GITR–Ab (DTA-1) nor GITR–Fc activated caspase-3 on the neurospheres (i). (a and d) Scale bar: 100 μm. (g–i) n=3 for each experimental group. **P<0.01 versus control groups (g: without TNF-α; h: CHZ without Jo-2). No significant difference was found among the groups (i)

Effect of GITR-stimulated Gld-T cells on survival/death of neural stem/progenitor cells

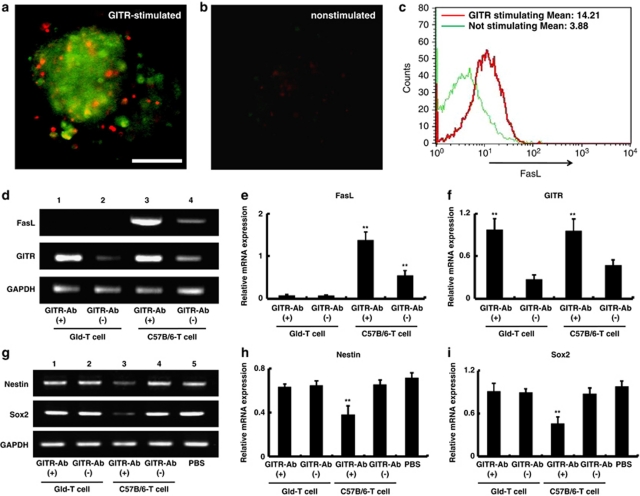

To assess the action of activated T cells, neurospheres were incubated with T cells (either GITR stimulated or non-stimulated) for 24 h (Figures 8a and b). Consistent with previous studies,16, 24 T cells stimulated by GITR–Ab showed upregulation of Fas ligand (FasL) expression (Figures 8c and d; lanes 3 and 4) as well as GITR expression (Figure 8d; lanes 3 and 4). Annexin V staining showed that neurospheres coincubated with GITR-stimulated T cells underwent apoptosis (Figure 8a), but those with non-stimulated T cells did not (Figure 8b). This result strongly suggested a role of FasL expressed on T cells in the iNSPCs apoptosis. Because nestin-positive iNSPCs were frequently observed in close association with endothelial cells20, 21 and CD4+T cells (Supplementary Figure 3) in the poststroke brain, it is highly possible that activated T cells induce apoptosis of iNSPCs by cell to cell interactions.

Figure 8.

Involvement of Fas ligand expressed on the surface of T cells in survival/death of neural stem/progenitor cells. Incubation with GITR-stimulated T cells induced apoptotic cell death on neurospheres determined by Annexin V staining (a: green), whereas no cell death was observed in the presence of non-stimulated T cells (b). The upregulated FasL expressed on GITR-stimulated T cells was confirmed by FACS analysis (c: red line indicates the FasL expression on GITR-stimulated T cells, and green line on non-stimulated T cells in CD4+ T cells). The mean channel values were displayed for FasL in the CD4+ T cells. Conventional RT-PCR showed that T cells obtained from Gld mice (Gld-T cell) never expressed Fas ligand even after GITR stimulation (d: lanes 1 and 2; e), whereas T cells of wild C57/B6 mice expressed it (d: lanes 3 and 4; e). GITR stimulation upregulated GITR on T cells regardless of the presence of FasL (d: lanes 1 and 3; f). The group of GITR-stimulated T cells from C57B/6 only significantly upregulated FasL (d and e). (a) Scale bar: 100 μm. (e and f) n=5 for each experimental group. **P<0.01 versus Gld-T cell groups or non-stimulated T (GITR–Ab(−)/C57B/6-T) cell group. Expression of nestin or Sox2 detected by conventional RT-PCR in the ischemic cortex of SCID mice 7 days after stroke was not affected by administration of Gld-T cells stimulated by GITR–Ab (g: first versus second lanes; h and i), although it was significantly decreased after treatment with wild-type (C57B/6) T cells stimulated by GITR-Ab (g: third versus fourth lanes; h and i). The relative expression of nestin or Sox2 was significantly suppressed only in the case of mice administered with FasL-expressed T cells stimulated by GITR–Ab. (h and i) n=5 for each experimental group. **P<0.01 versus Gld-T cell groups, GITR(−)/C57B/6-T-cell group or PBS group. No significant difference was found among the other groups

To confirm this hypothesis in vivo, we administered T cells from the FasL-deficient (generalized lymphoproliferative disorder=spontaneous mutation in the Fas ligand gene; gld) mice,25 stimulated by GITR–Ab, to poststroke SCID mice and analyzed the expression of nestin and Sox2 in the postischemic area by conventional RT-PCR. As gld-T cells stimulated by GITR–Ab showed enhanced GITR expression compared with non-stimulated gld-T cells similar to T cells from wild-type mice (Figure 8d; lanes 1 and 2, Figure 8f), the injected T cells were considered to be activated without expression of FasL (Figure 8e). Although administration of GITR-stimulated T cells from wild mice (C57/B6) significantly attenuated nestin and Sox2 expression (Figure 8g; lanes 3 and 4), administration of GITR-stimulated gld-T cells had no significant effect (Figure 8g; lanes 1 and 2). Relative expressions of nestin and Sox2 were attenuated only by GITR-stimulated wild-type T cells from wild mice, but not by GITR-stimulated gld-T cells or non-stimulated T cells (Figures 8h and i; P<0.01, among the five groups). These findings indicate that GITR-triggered activated CD4+T cells directly induce Fas-mediated apoptosis of iNSPCs through possible cell to cell interactions.

Discussion

This study clearly demonstrated a key role of GITR triggering in regulation of neurogenesis after stroke, thereby delineating the contribution of activated T cells expressing GITR to the survival of neural stem/progenitor cells in the poststroke cortex. Because a subset of CD4+T cells mainly expresses GITR after stroke, it is likely that activated CD4+T cells triggered by GITR are harmful to the new-born cells. The current study also suggests possible mechanisms involving FasL- and TNF-α-induced cell death signals, suggesting interactions between iNSPCs and GITR-triggered T cells, with the latter serving as negative regulators for CNS repair after cerebral infarction.

GITR was originally cloned from a glucocorticoid-treated hybridoma T-cell line as a TNF-receptor-like molecule induced by glucocorticoid-sensitive T cells.12 GITR is now considered to be upregulated in T cells by T-cell receptor (TCR)-mediated activation.26 As GITR-expressing T cells are resistant to glucocorticoid-induced cell death, it has been proposed that GITR, in conjunction with other TCR-induced factors, protects T cells from apoptosis.26 In fact, GITR can be upregulated by viral infection27 or acute lung inflammation.15 In the present study, we have demonstrated for the first time that GITR is upregulated in T cells by ischemic insult to the brain, although previous reports have shown the role of GITR in ischemic damage on the kidney or the intestine.28, 29

Consistent with our previous study,8 CD4+T cells predominantly migrated to the infarcted brain after stroke. The high number of GITR+CD4+T cells suggested that activated T-cell proliferation contributed to the poststroke inflammatory response. GITR has been reported to enhance the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, from GITR+T cells.30 In contrast, GITR triggering on CD4+CD25+Treg completely abrogates the suppressing effect of Treg,13 which normally secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10.31 Thus, we suggest that upregulation of the GITR expression in the brain can aggravate T-cell-mediated poststroke inflammation. The present study demonstrated that GITR triggering in poststroke mice enhanced, and its blocking ameliorated the poststroke inflammatory response as indicated by modulation of cytokines, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-10. These data suggest that T-cell-mediated poststroke inflammation can be modulated by the immune response deriving from GITR–GITRL interaction.

It is well known that cerebral injury induces a disturbance of the normally well-balanced interplay between the immune system and the CNS.32 This process results in homeostatic signals being sent to various sites in the body through pathways of neuroimmunomodulation, including hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Activation of the HPA axis results in the production of glucocorticoid hormones. Although glucocorticoid does prevent inflammation by suppressing production of many proinflammatory mediators, including cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α, it also induces apoptosis in immature and mature T lymphocytes.33 The latter may in turn lead to secondary immunodeficiency.32 Alternatively, surviving T cells that are resistant to glucocorticoid stress express GITR and may contribute to the aggravation of inflammation.

Inflammation in neural tissue has long been suspected to have a role in stroke. Immune influence on adult neural stem cell regulation and function has also received much attention. Although the details of immune signaling in the CNS are not known, the impact of inflammatory signaling on adult neurogenesis is known to be focused on the activation of microglia as a source of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β. We and others34 have proved that neural stem cells undergo apoptosis by TNF-α in vitro, suggesting that TNF-α has a negative effect on poststroke neurogenesis. Recent publication has revealed that GITR and GITRL are functionally expressed on brain microglia, and that the stimulation of GITRL can induce inflammatory activation of microglia.35 However, as iNSPCs never expressed GITR, it is more likely that microglia contribute to iNSPC cell death indirectly via TNF-α, which is secreted from the activated microglia. We also propose that IFN-γ produced by activated GITR+T cells stimulates microglia production of high levels of TNF-α to induce apoptosis of iNSPCs through TNFR-1. It also has been reported that TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) has an important role in developing CNS injury, and that anti-TRAIL treatment prevents GITR expression induced by spinal cord injury.36 As GITR-deficient mice showed attenuated TRAIL expression after SCI, blocking the GITR–GITRL interaction by GITR–Fc protein may protect from the inflammatory response via TRAIL-activated pathways.

In addition to cytokine effects on neurogenesis, we also proposed the Fas-mediated pathway that affects poststroke neurogenesis, as another target of immune signaling. Our previous study8 had shown that Fas-positive iNSPCs underwent apoptosis in the poststroke cortex. The current study confirmed that GITR+T cells expressing FasL triggered apoptosis of iNSPC in vitro and reduced the expression of nestin and Sox2 in the poststroke brain. These findings suggest that activated T cells act on Fas-expressing iNSPCs via cell to cell interactions in the poststroke brain, although it is very difficult to prove the functional contact between iNSPCs and Fas-expressing T cells in vivo. As nestin-positive iNSPCs are in close association with endothelial cells20, 21 where CD4+T cells are infiltrated (Supplementary Figure 3), it is possible that activated T cells are in contact with neural stem/progenitor cells when the endothelial cells are damaged by ischemic insult. Although another system that activates neurogenesis through soluble FasL and Fas receptor in conventional neurogenic regions has been previously reported,37 the current study may prove that the membrane-bound FasL expressed on T cells is essential for Fas-induced apoptosis.38

Recent study has proposed the contribution of Tregs in prevention of secondary infarct growth.2, 4 Because IL-10 signaling was mainly produced by CD4+CD25+Tregs and proinflammatory cytokines were downregulated in brains of IL-10 transgenic mice, Tregs apparently contribute to the anti-inflammatory system after stroke. Although GITR+T cells are known to belong to Tregs, a recent study has emphasized that GITR is a marker for activated effector T cells.39 The CD4+CD25− T-cell-derivedGITR+ cells (GITR+ non-Treg) are also known to activate self-reactive T cells by attenuating the function of Tregs,13 indicating that they may harm the living cells by eliciting autoimmunity.13, 24 We demonstrated in the current study that blocking the GITR–GITRL interaction by GITR–Fc protein increased IL-10 expression in the poststroke cortex, suggesting that blocking such interactions enhanced Treg function as well as inhibition of effector T cell function. On the basis of these findings, the present study suggests that the novel therapies for stroke may ultimately include GITR-targeted manipulation of immune signaling.

Materials and Methods

All procedures were carried out under auspices of the Animal Care Committee of Hyogo College of Medicine, and were in accordance with the criteria outlined in the ‘Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals' prepared by the National Academy of Science. Quantitative analyses were conducted by investigators who were blinded to the experimental protocol and identity of the samples under study.

Induction of focal cerebral ischemia

Male, 5- to 7-week-old, CB17/Icr +/+ Jcl mice (CB-17 mice; Clea Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and CB-17/Icrscid/scid Jcl mice (SCID mice; CLEA Japan Inc.) were subjected to cerebral ischemia. Permanent focal cerebral ischemia was produced by ligation and disconnection of the distal portion of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA), as described in a previous study. In brief, the left MCA was isolated, electrocauterized and disconnected just distal to its crossing of the olfactory tract (distal M1 portion) under halothane inhalation. The infarcted area in mice of this background has been shown to be highly reproducible and limited to the ipsilateral cerebral cortex. Permanent MCA occlusion (MCO) is achieved by coagulating the vessel. In sham-operated mice, arteries were visualized but not coagulated.

Immunohistochemistry

To histochemically analyze the infarcted cortex, mice were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were then removed, and coronal sections (14 μm) were stained with mouse antibodies against nestin (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA; 1/100), Sox2 (Millipore; 1/100), NeuN (Millipore; 1/200), rabbit antibodies against caspase-3 active (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA; 1/100), CD3 (AnaSpec, San Jose, CA, USA; 1/100), CD31 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; 1/100), rat antibody against CD4 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA; 1/100) and GITR (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA; 1/100). As secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse, -rabbit or -rat IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; 1/500) was used. Cell nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole ( DAPI, Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD, USA; 1/500). The number of nestin and Sox2 double-positive cells at the border of infarctions, including the infarcted and peri-infarcted areas (0.5 mm in width), was counted under a laser microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

To perform quantitative analysis of T cells, all CD3–, CD4– or CD3–GITR-double-positive cells within the infarcted area were counted in the brain sections obtained from CB-17 mice at 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 3 days and 7 days after stroke. Furthermore, active caspase-3 and nestin double-positive cells within the infarcted area were counted in the brain sections at 3 days after stroke. To investigate cell proliferation at 7 days after stroke, BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO, USA; 50 mg/kg) was administered 6 h before fixation. Tissue was pretreated with 2N HCl for 30 min at 37°C and 0.1 M boric acid (pH 8.5) for 10 min at room temperature, and then stained with antibody against BrdU. Next, the number of positive cells for each marker was determined using modified Image J (National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) as per a previous report.8 Results were expressed as the number of cells/mm2.

The expression of Fas and TNFR-1 for neurosphere

To study the expression of Fas and TNFR-1in the neurosphere in vitro, immunochemistry was performed with rabbit antibody against Fas (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan; 1/100) or TNFR-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1/100). As secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen; 1/500) was used. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories; 1/500).

Measurement of involution of the ipsilateral cerebral hemisphere volume

Thirty days after stroke, mice were perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde, brains were removed and coronal sections (14 μm) were stained with mouse antibodies against NeuN, followed by reaction with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA; 1/500), ABC Elite reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and DAB (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation) as chromogen. The area of the ipsilateral and contralateral cerebral hemisphere occupied by the neuronal markers, NeuN and MAP2, was calculated using Image J.8 The ipsilateral and contralateral cerebral hemisphere volume was calculated by integrating the coronally oriented ipsilateral and contralateral cerebral hemisphere area as described previously.8 Involution of the ipsilateral cerebral hemisphere volume was calculated as (ipsilateral/contralateral cerebral hemisphere volume).

FACS analysis of infiltrated lymphocytes into the ischemic brain

Animals were killed 1 or 7 days after MCO. The ischemic area of the brain was isolated. Tissues from the four operated mice were incubated with RPMI1640 (Invitrogen), containing 1 mg/ml collagenase (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) and 0.1 mg/ml DNAse I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and pressed through a 40-μm cell strainer18 (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The mononuclear cells were separated by Ficoll-paque plus (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) centrifugation, and labeled with antibody cocktails (PerCP-CD3 (BD Biosciences), FITC-CD4 (eBioscience), PE-GITR (BD Biosciences) and APC-CD25 (eBioscience)). Rat IgG2a (eBioscience) was used as control isotype staining. The analysis of cells was performed by four-color flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) using CELLQuest Software (BD Biosciences).

RNA isolation and PCR reaction

Total RNA was isolated from the cerebral cortex of the infarcted area using ISOGEN (Nippon gene, Tokyo, Japan), and was treated using Turbo DNA-free kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol.

Quantity and quality of the isolated RNA was tested by using a Nanodrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays and the ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) with Real-time PCR Master Mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). Three replicates were run for each sample in a 384-well format plate. TaqMan Gene Expression Assays IDs were described as follows. IFN-γ: Mm01168134_m1, TNF-γ: Mm00443258_m1, IL-10: Mm01288386_m1 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH): Mm99999915_g1.

Conventional RT-PCR was performed using a PC-708 (Astec, Fukuoka, Japan) with Super Script III One step (Invitrogen). cDNA was amplified under the following conditions: 15 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C and 1 min at 68°C (35 cycles). PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis using Mupid (Advance, Tokyo, Japan). The band intensity was determined with a LAS-1000 densitometer (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan). Primer sequences were as follows:

nestin, forward 5′-CACTAGAAAGCAGGAACCAG-3′ and reverse 5′-AGATGGTTCACAATCCTCTG-3′

Sox2, forward 5′-TTGGGAGGGGTGCAAAAAGA-3′ and reverse 5′-CCTGCGAAGCGCCTAACGTA-3′

GITR, forward 5′-CCACTGCCCACTGAGCAATAC-3′ and reverse 5′-GTAAAACTGCGGTAAGTGAGGG-3′

FasL, forward 5′-CTTGGGCTCCTCCAGGGTCAGT-3′ and reverse 5′-TCTCCTCCATTAGCACCAGATCC-3′ and

GAPDH, forward 5′-GGAAACCCAGAGGCATTGAC-3′ and reverse 5′-TCAGGATCTGGCCCTTGAAC-3′.

For normalization of real-time data, GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Preparation of induced neural stem/progenitor cells

As described previously,6 tissue from the ischemic cortex was mechanically dissociated by passage through 23- and 27-gauge needles to prepare a single-cell suspension. The resulting cell suspensions were incubated in a medium promoting formation of neurosphere-like clusters. Cells were incubated in tissue culture dishes (60 mm) with DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) containing epidermal growth factor (EGF; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA; 20 ng/ml) and fibroblast growth factor-basic (FGF-2; Peprotech; 20 ng/ml). On day 7 after incubation, neurosphere-like cell clusters (primary spheres) were formed and were reseeded at a density of 10–15 neurospheres/well in 12-well low-binding plates.

Induction of apoptosis of neural stem/progenitor cells

To study the effect of TNF-α- or Fas-mediated signaling in vitro, neurospheres were incubated with TNF-α (R&D systems; 20 mg/ml and 100 mg/ml) or agonistic anti-Fas (Jo-2; BD Biosciences; 1 μg/ml) containing cycloheximide (CHZ; Sigma-Aldrich Corporation; 1 mg/ml),40 agonistic anti-GITR (DTA-1; 10 μg/ml) or GITR–Fc fusion protein (6.25 μg/ml, Alexis Corporation, Lausen, Switzerland) in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) for 24 h. Next, the activity of caspase-3 was examined using a caspase-3 assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, neurospheres were homogenized in lysis buffer and centrifuged at 20 000 g for 15 min. Supernatants were mixed with assay buffer and caspase-3 substrate. Absorbance at 405 nm was measured, and caspase-3 activity was calculated (n=3, in each group) using a spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA). Caspase-3 activity was correlated with the protein concentration, which was determined by the DC protein assay (Lowry method; Bio-rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). To confirm the cells undergoing apoptosis, neurospheres incubated with these reagents were stained with Annexin V (BD Biosciences), and were observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss International, Jena, Germany).

To examine the apoptotic activity of T cells in vitro, T cells were obtained from the spleens of mice (several strains) involving CB-17 and gld (FasL deficient) and their C57/B6 backgrounds,25 by using a nylon fiber column (Wako Pure Chemical Industries). T cells also were obtained from normal male C57BL/6 (Japan SLC, Shizuoka, Japan) or C57BL/6-Tg (CAG-EGFP) C14-Y01-FM131Osb transgenic mice (purchased from RIKEN BRC, Tsukuba, Japan). The T cells were stimulated with solid phase of anti-CD3ɛ antibody (BD Bioscience): T cells were incubated with GITR–Ab (DTA-1: 10 μg/ml) or control rat IgG (eBioscience) for 48 h in RPMI1640 (Invitrogen) in culture plate coated with 10 μg/ml of anti-CD3e antibody. Expression of FasL on GITR-stimulated T cells or non-stimulated T cells was analyzed with FACS. Each sample was labeled with antibody cocktails (PerCP-CD3, FITC-CD4 and PE-FasL (BD Biosciences)) The analysis of cells was performed by three-color flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur using CELLQuest Software. Then, 1 × 106 T cells were coincubated with neurospheres in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) for 24 h (10–15 neurospheres/well in 12-well low-binding plates). These neurospheres were stained with Annexin V and observed with a microscope, as mentioned above. GFP-Tg mice were purchased from CLEA Japan Inc.

Administration of GITR–Ab or GITR–Fc

GITR–Ab (100 μg/mice, DTA-1; eBioscience), GITR–Fc fusion protein (6.25 μg/mice)16 or rat IgG isotype control (100 μg/mice, eBioscience) was intraperitoneally administered to mice at 3 h and 3 days after stroke.

Administration of T cells into poststroke SCID mice

T cells (1 × 106 cells/100 μl in PBS) obtained from several strains of mice (stimulated or non-stimulated by GITR-Ab), including CB-17, GFP-Tg, Gld- or C57/B6 mice, were injected intravenously into SCID mice at 48 h after stroke. Mice were subjected to histological examination after stroke. In another experiment, their brains were utilized for PCR analysis of nestin and Sox2.

Statistical analysis

Results were reported as the mean standard deviation. Statistical comparisons among groups were determined using one-way analysis of variance. Where indicated, individual comparisons were performed using Student's t-test. The groups with P<0.01 or, in some cases, P<0.05 differences were considered significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (21590473), and Hyogo Science and Technology Association. We thank Y Okinaka and Y Tanaka for technical assistance, and Dr. H Yamamoto for helpful discussion.

Glossary

- BrdU

5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- CNS

central nervous system

- DAPI

4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- FasL

Fas ligand

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GITR

glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor

- GITRL

GITR ligand

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- gld

generalized lymphoproliferative disorder=spontaneous mutation in the Fas ligand gene

- iNSPC

ischemia-induced neural stem/progenitor cell

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficient

- Sox2

SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 2

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- Treg

regulatory T cell

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by JA Cidlowski

Supplementary Material

References

- Hurn P, Subramanian S, Parker S, Afentoulis M, Kaler L, Vandenbark A, et al. T- and B-cell-deficient mice with experimental stroke have reduced lesion size and inflammation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1798–1805. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesz A, Suri-Payer E, Veltkamp C, Doerr H, Sommer C, Rivest S, et al. Regulatory T cells are key cerebroprotective immunomodulators in acute experimental stroke. Nat Med. 2009;15:192–199. doi: 10.1038/nm.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambertsen K, Gregersen R, Meldgaard M, Clausen B, Heibøl E, Ladeby R, et al. A role for interferon-gamma in focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:942–955. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.9.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bilbao F, Arsenijevic D, Moll T, Garcia-Gabay I, Vallet P, Langhans W, et al. In vivo over-expression of interleukin-10 increases resistance to focal brain ischemia in mice. J Neurochem. 2009;110:12–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson A, Collin T, Kirik D, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Neuronal replacement from endogenous precursors in the adult brain after stroke. Nat Med. 2002;8:963–970. doi: 10.1038/nm747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagomi T, Taguchi A, Fujimori Y, Saino O, Nakano-Doi A, Kubo S, et al. Isolation and characterization of neural stem/progenitor cells from post-stroke cerebral cortex in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:1842–1852. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi A, Soma T, Tanaka H, Kanda T, Nishimura H, Yoshikawa H, et al. Administration of CD34+ cells after stroke enhances neurogenesis via angiogenesis in a mouse model. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:330–338. doi: 10.1172/JCI20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saino O, Taguchi A, Nakagomi T, Nakano-Doi A, Kashiwamura S, Doe N, et al. Immunodeficiency reduces neural stem/progenitor cell apoptosis and enhances neurogenesis in the cerebral cortex after stroke. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:2385–2397. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschnitz C, Schwab N, Kraft P, Hagedorn I, Dreykluft A, Schwarz T, et al. Early detrimental T-cell effects in experimental cerebral ischemia are neither related to adaptive immunity nor thrombus formation. Blood. 2010;115:3835–3842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz G, Arumugam T, Stokes K, Granger D. Role of T lymphocytes and interferon-gamma in ischemic stroke. Circulation. 2006;113:2105–2112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.593046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovich PG, Longbrake EE. Can the immune system be harnessed to repair the CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:481–493. doi: 10.1038/nrn2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini G, Giunchi L, Ronchetti S, Krausz L, Bartoli A, Moraca R, et al. A new member of the tumor necrosis factor/nerve growth factor receptor family inhibits T cell receptor-induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6216–6221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Takahashi T, Ishida Y, Sakaguchi S. Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:135–142. doi: 10.1038/ni759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon B, Yu KY, Ni J, Yu GL, Jang IK, Kim YJ, et al. Identification of a novel activation-inducible protein of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily and its ligand. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6056–6061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Nocentini G, Di Paola R, Agostini M, Mazzon E, Ronchetti S, et al. Proinflammatory role of glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor-related gene in acute lung inflammation. J Immunol. 2006;177:631–641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini G, Cuzzocrea S, Genovese T, Bianchini R, Mazzon E, Ronchetti S, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor-related (GITR)-Fc fusion protein inhibits GITR triggering and protects from the inflammatory response after spinal cord injury. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1610–1621. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.044354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohm A, Williams J, Miller S. Cutting edge: ligation of the glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor enhances autoreactive CD4+ T cell activation and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2004;172:4686–4690. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelderblom M, Leypoldt F, Steinbach K, Behrens D, Choe C, Siler D, et al. Temporal and spatial dynamics of cerebral immune cell accumulation in stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:1849–1857. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.534503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen BH, Lambertsen KL, Babcock AA, Holm TH, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Finsen B. Interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are expressed by different subsets of microglia and macrophages after ischemic stroke in mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:46. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano-Doi A, Nakagomi T, Fujikawa M, Nakagomi N, Kubo S, Lu S, et al. Bone Marrow mononuclear cells promote proliferation of endogenous neural stem cells through vascular niches after cerebral infarction. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1292–1302. doi: 10.1002/stem.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagomi N, Nakagomi T, Kubo S, Nakano-Doi A, Saino O, Takata M, et al. Endothelial cells support survival, proliferation, and neuronal differentiation of transplanted adult ischemia-induced neural stem/progenitor cells after cerebral infarction. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2185–2195. doi: 10.1002/stem.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abematsu M, Tsujimura K, Yamano M, Saito M, Kohno K, Kohyama J, et al. Neurons derived from transplanted neural stem cells restore disrupted neuronal circuitry in a mouse model of spinal cord injury. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3255–3266. doi: 10.1172/JCI42957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iosif R, Ekdahl C, Ahlenius H, Pronk C, Bonde S, Kokaia Z, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 is a negative regulator of progenitor proliferation in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9703–9712. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2723-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muriglan SJ, Ramirez-Montagut T, Alpdogan O, Van Huystee TW, Eng JM, Hubbard VM, et al. GITR activation induces an opposite effect on alloreactive CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells in graft-versus-host disease. J Exp Med. 2004;200:149–157. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E, Moreau G, Arnould A, Vasseur F, Khodabaccus N, Dy M, et al. Increased fetal and extramedullary hematopoiesis in Fas-deficient C57BL/6-lpr/lpr mice. Blood. 1999;94:2613–2621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y, Funda DP, Every AL, Fundova P, Purton JF, Liddicoat DR, et al. TCR-mediated activation promotes GITR upregulation in T cells and resistance to glucocorticoid-induced death. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1315–1321. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvas S, Kim B, Sarangi PP, Tone M, Waldmann H, Rouse BT. In vivo kinetics of GITR and GITR ligand expression and their functional significance in regulating viral immunopathology. J Virol. 2005;79:11935–11942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11935-11942.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro RM, Camara NO, Rodrigues MM, Tzelepis F, Damião MJ, Cenedeze MA, et al. A role for regulatory T cells in renal acute kidney injury. Transpl Immunol. 2009;21:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Nocentini G, Di Paola R, Mazzon E, Ronchetti S, Genovese T, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor family gene (GITR) knockout mice exhibit a resistance to splanchnic artery occlusion (SAO) shock. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:933–940. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronchetti S, Zollo O, Bruscoli S, Agostini M, Bianchini R, Nocentini G, et al. GITR, a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, is costimulatory to mouse T lymphocyte subpopulations. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:613–622. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Garra A, Vieira P. Regulatory T cells and mechanisms of immune system control. Nat Med. 2004;10:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nm0804-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel C, Schwab JM, Prass K, Meisel A, Dirnagl U. Central nervous system injury-induced immune deficiency syndrome. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:775–786. doi: 10.1038/nrn1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharchuk CM, Meræep M, Chakraborti PK, Simons SS, Ashwell JD. Programmed T lymphocyte death. Cell activation- and steroid-induced pathways are mutually antagonistic. J Immunol. 1990;145:4037–4045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iosif R, Ahlenius H, Ekdahl C, Darsalia V, Thored P, Jovinge S, et al. Suppression of stroke-induced progenitor proliferation in adult subventricular zone by tumor necrosis factor receptor 1. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1574–1587. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H, Lee S, Lee W, Lee H, Suk K. Stimulation of glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor family-related protein ligand (GITRL) induces inflammatory activation of microglia in culture. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:2188–2196. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarella G, Di Benedetto G, Scollo M, Paterniti I, Cuzzocrea S, Bosco P, et al. Neutralization of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand reduces spinal cord injury damage in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1302–1314. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsini NS, Sancho-Martinez I, Laudenklos S, Glagow D, Kumar S, Letellier E, et al. The death receptor CD95 activates adult neural stem cells for working memory formation and brain repair. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:178–190. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O' Reilly LA, Tai L, Lee L, Kruse EA, Grabow S, Fairlie WD, et al. Membrane-bound Fas ligand only is essential for Fas-induced apoptosis. Nature. 2009;461:659–663. doi: 10.1038/nature08402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini G, Ronchetti S, Cuzzocrea S, Riccardi C. GITR/GITRL: more than an effector T cell co-stimulatory system. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1165–1169. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y, Hirabayashi Y, Matsuzaki Y, Musette P, Ishii A, Nakauchi H, et al. In vivo analysis of Fas antigen-mediated apoptosis: effects of agonistic anti-mouse Fas mAb on thymus, spleen and liver. Int Immunol. 1997;9:307–316. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.