Abstract

Selecting neuronal cell lines for resistance against oxidative stress might recapitulate some adaptive processes in neurodegenerative diseases where oxidative stress is involved like Parkinson's disease. We recently reported that in hippocampal HT22 cells selected for resistance against oxidative glutamate toxicity, the cystine/glutamate antiporter system xc−, which imports cystine for synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione, and its specific subunit, xCT, are upregulated. (Lewerenz et al., J Neurochem 98(3):916–25). Here, we show that in these glutamate-resistant HT22 cells upregulation of xCT mediates glutamate resistance, and xCT expression is induced by upregulation of the transcription factor ATF4. The mechanism of ATF4 upregulation consists of a 13 bp deletion in the upstream open reading frame (uORF2) overlapping the ATF4 open reading frame. The resulting uORF2–ATF4 fusion protein is efficiently translated even at a low phosphorylation levels of the translation initiation factor eIF2α, a condition under which ATF4 translation is normally suppressed. A similar ATF4 mutation associated with prominent upregulation of xCT expression was identified in PC12 cells selected for resistance against amyloid β-peptide. Our data indicate that ATF4 has a central role in regulating xCT expression and resistance against oxidative stress. ATF4 mutations might have broader significance as upregulation of xCT is found in tumor cells and associated with anticancer drug resistance.

Keywords: ATF4, xCT, glutathione, oxidative stress, glutamate

The antioxidant glutathione (GSH) is an important defense against oxidative stress (for reviews see Schulz et al.1; Hayes et al.2) Moreover, conjugation to GSH by GSH S-transferases is the major mechanism for neutralization of some anticancer drugs.3 The ratio of GSH to oxidized GSH (GSSG) represents the overall intracellular redox potential, which when more reduced has been linked to proliferation whereas a more oxidized environment favours cellular differentiation.4 However, accumulation of reactive oxygen species, a state called oxidative stress, leads to the damage of biomolecules including proteins, lipids and DNA, and subsequently cell death.5 Oxidative stress is relevant to many neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's dementia (AD) and Parkinson's disease.1 Probably, the surviving CNS cells adapt to the oxidative stress during the course of these diseases. A similar adaptation occurs in tumors where the micromilieu is also very pro-oxidant.6

Selecting neuronal cell lines for resistance against in vitro paradigms of cell death induced by oxidative stress can be used as an in vitro model for the adaptive processes present in diseases with chronic oxidative stress.7, 8, 9 This approach identified increased signaling via hypoxia-induced factor 1 and upregulated glycolysis as a protective response against Aβ toxicity,10 both of which have also been observed as an antioxidant response in tumor cells.11 This suggests common pathways to defend and survive chronic oxidative stress during neurodegeneration and tumor progression.

Oxidative glutamate toxicity is an in vitro paradigm for neuronal cell death in response to oxidative stress wherein GSH depletion is brought about by glutamate-mediated inhibition of cystine uptake throught the cystine/glutamate antiporter system xc− (reviewed in Albrecht et al.12). We previously reported that murine hippocampal HT22 cells selected for resistance against oxidative glutamate toxicity (HT22-R) show prominent compensatory upregulation of system xc−.9 System xc− imports cystine into the cells in a 1 : 1 exchange with glutamate.13 It thus provides the cysteine, the rate-limiting substrate for GSH synthesis.1 System xc− is composed of the specific subunit xCT and a heavy chain, 4F2hc.14 xCT expression is increased adjacent to cerebral Aβ deposits in a mouse model of AD,15 overexpressed in malignant glioblastomas16 and xCT expression positively correlates with resistance against chemotherapeutics in cancer cells.17

The nuclear factor ATF4 activates system xc− by inducing xCT18, 19 as well as 4F2hc expression.20 ATF4 is a member of the ATF/CREB group of the bZIP transcription factor family.21 ATF4 activates transcription when bound to the amino-acid response element (AARE) in promoter regions.22 The 5′ end of the ATF4 mRNA contains two additional upstream open reading frames (uORFs), one of which partially overlaps the ATF4 ORF.23 Whereas translation of uORF1 positively regulates both uORF2 and ATF4 translation, translation of uORF2 inhibits translation of the ATF4 ORF. This suppression is relieved under the conditions where phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α at serine-51 is induced. eIF2α phosphorylation delays the ability to reinitiate translation of ribosomes scanning from 5′ to 3′ along the ATF4 mRNA after uORF1 has been translated and thus favors the initiation of translation at the more 3′ start codon of ATF4.23 Both ATF4 protein and eIF2α phosphorylation are upregulated in AD brains19 as well as in diverse tumors including malignant glioblastomas.24 High ATF4 levels were also found in cancer cell lines resistant to anticancer drugs.25

Here, we report the expression of an atypical ATF4 protein resulting from deletions in the uORF2 of the ATF4 mRNA in glutamate-resistant HT22 cells and in Aβ-resistant PC12 cells. This altered ATF4 leads to constitutive upregulation of system xc and subsequently cellular GSH.

Results

Upregulation of system xc− mediates the resistant phenotype in glutamate-resistant HT22 cells

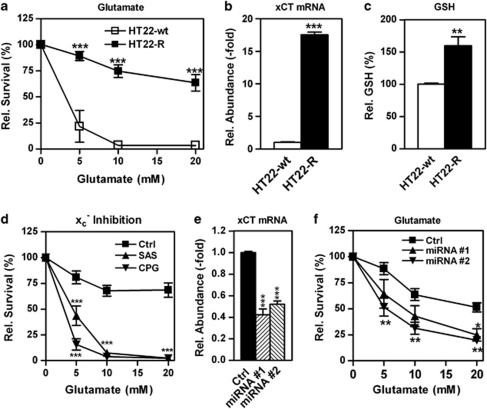

As reported previously,9 xCT mRNA is highly upregulated in hippocampal HT22 cells selected for resistance against oxidative glutamate toxicity (HT22-R; Figures 1a and b). As a result, total GSH in HT22-R cells is significantly upregulated as well (Figure 1c). To support the hypothesis that the upregulation of xCT is essential for the glutamate-resistant phenotype, we employed several different strategies. First, addition of the structurally unrelated system xc− inhibitors sulfasalazine or (S)-4-carboxyphenylglycine dramatically sensitized HT22-R cells to glutamate (Figure 1d). In addition, knockdown of xCT mRNA expression by transient transfection with vectors leading to the expression of two different microRNAs (miRNAs) specific for xCT (Figure 1e) also increased the sensitivity of HT22-R cells to oxidative glutamate toxicity (Figure 1f). Transient transfection with two different xCT siRNAs had a similar effect (Supplementary Figure 1). Thus, xCT upregulation is indeed an essential mediator of glutamate resistance in HT22-R cells.

Figure 1.

Upregulation of xCT mediates glutamate resistance in HT22-R cells. (a) HT22-wt and –R cells were exposed to glutamate at the indicated concentrations, and survival was measured by the MTT assay after 24 h. The graph represents the mean of four experiments with the viability at 0 mM glutamate normalized to 100% as mean±S.E.M. (b) xCT mRNA in HT22-wt and –R cells was quantified by qPCR and normalized to the expression of the housekeeping genes HRPT and β-actin. The results of two independent experiments, each performed in triplicate, are shown as mean±S.E.M. with the expression in HT22-wt cells normalized to 1. (c) Total GSH in HT22-wt and –R cells was quantified enzymatically and normalized to cellular protein. The graph shows the mean±S.E.M. of three independent experiments each performed in duplicate with the GSH in HT22-wt cells normalized to 100%. (d) HT22-R cells were exposed to glutamate at the indicated concentrations in the presence of 50 μM sulfasalazine (SAS), 25 μM (S)-4-carboxyphenylglycine (CPG) or vehicle (Ctrl). After 24 h viability was quantified by the MTT assay and the viability of cells treated with the system xc− inhibitor or vehicle alone was normalized to 100%. The graph shows the mean of three independent experiments as mean±S.E.M. (e and f) HT22-R cells were transiently transfected with the control vector (Ctrl) or vectors expressing two different xCT-specific miRNAs (#1, #2). xCT mRNA was quantified by qPCR (e) and transfected cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of glutamate (f). Viability was assessed by the MTT assay and viability of cells exposed to 0 mM glutamate normalized to 100%. The graph shows the results of four experiments each performed in triplicate (e) and the mean of six experiments (f) as mean±S.E.M. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (a, d, f), one-way ANOVA (e) with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons post test or two-sided unpaired t-test (b and c). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

Upregulation of an ATF4 isoform with a higher apparent molecular weight upregulates system xc− activity in HT22-R cells and mediates resistance against oxidative glutamate toxicity

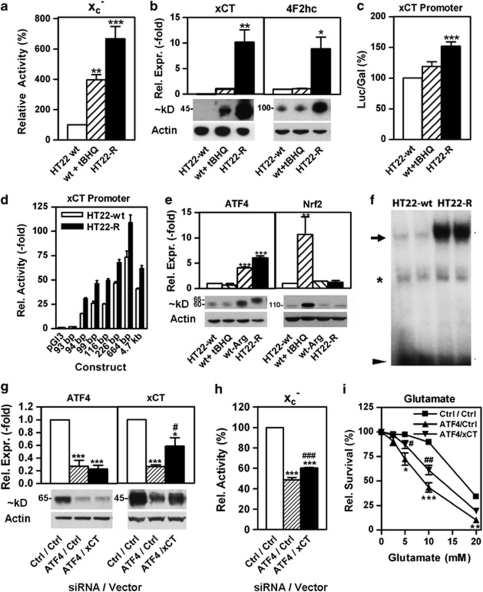

As the transcription factor Nrf2 is an important activator of xCT expression,26, 27 we began our investigation to clarify the mechanism of system xc− upregulation in HT22-R cells by comparing the effects of a classical Nrf2 inducer, tert-butylhydroquinone (tBHQ), on system xc− activity and xCT levels in HT22-wt cells to the basal levels of system xc− activity and xCT in HT22-R cells. Treatment of HT22-wt cells with tBHQ increased system xc− activity approximately fourfold as compared with the more than sixfold higher activity in untreated HT22-R cells (Figure 2a). Similarly, xCT protein levels were much lower in HT22-wt cells after tBHQ treatment as compared with untreated HT22-R cells (Figure 2b, left panel). Furthermore, although expression of the system xc− heavy chain, 4F2hc, was not induced by tBHQ in HT22-wt cells, it was markedly upregulated in untreated HT22-R cells (Figure 2b, right panel). Thus, a mechanism other than Nrf2 is involved in system xc− upregulation in the HT22-R cells.

Figure 2.

An ATF4 isoform with an apparent molecular weight ∼5 kD higher than regular ATF4 mediates the upregulation of xCT and glutamate resistance in HT22-R cells. (a) System xc− activity is upregulated in glutamate-resistant HT22 cells and HT22 cells treated with tBHQ. Glutamate-sensitive sodium-independent 35S-cystine uptake was measured in wild-type HT22 cells (HT22-wt), wild-type HT22 cells treated for 24 h with 25 μM tBHQ (wt + tBHQ) and glutamate-resistant HT22 cells (HT22-R). Individual experiments were performed in triplicate. The graph represents the mean of four (tBHQ) and five (HT22-R) independent experiments with the mean uptake in wild-type HT22 cells for each experiment normalized to 100% as mean±S.E.M. (b) Left panel: xCT protein is upregulated by tBHQ treatment in HT22-wt cells and in HT22-R cells. Equal amounts of purified membrane protein from HT22-wt cells, tBHQ-treated HT22-wt cells and HT22-R cells were analyzed by western blotting using an anti-xCT antibody. Actin served as loading control. The graph represents densitometric data of four independent protein preparations with xCT expression after tBHQ treatment normalized to 1 as mean±S.E.M. xCT was undetectable in HT22-wt without treatment. A representative blot is shown below. Right panel: 4F2hc is upregulated in HT22-R cells but not by tBHQ in HT22-wt cells. Western blots were hybridized with an anti-4F2hc antibody. The graph shows quantitative data of two independent protein preparations as mean±S.E.M. (c) xCT is transcriptionally upregulated. HT22-wt cells and HT22-R cells were co-transfected with a 4700 bp-xCT promoter luciferase construct or pGl3 and pSV-β-Gal vector. tBHQ (25 μM) was added to HT22-wt cells after transfection. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activity was measured after 24 h and normalized to pGL3 transfection. The luciferase induction in HT22-wt cells was normalized to 100%. The graph represents data from four independent experiments as mean±S.E.M. (d) Increased activity of the xCT promoter in HT22-R cells originates from the proximal AARE. HT22-wt and HT22-R cells were co-transfected with xCT promoter–luciferase constructs of the indicated lengths and the pSV-β-Gal vector. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activity were measured after 24 h. Luciferase/β-galactosidase ratio of HT22-wt cells co-transfected with pGL3 was normalized to 1. Deletion of the most proximal base pair (−94) of the proximal AARE abolishes the difference between HT22-wt and HT22-R cells. The graph represents data from four independent experiments as mean±S.E.M. xCT promoter activity in HT22-R cells was significantly higher (P<0.01) in all constructs >93 bp. (e) ATF4, but not Nrf2, is upregulated in HT22-R cells. Western blots of nuclear extracts of HT22-wt cells or HT22-R cells were hybridized with antibodies against ATF4 and Nrf2. Blots were probed with an anti-actin antibody as a loading control. Graphs represent quantitative data from five independent protein preparations and western blots for HT22-wt and -R as mean±S.E.M. To ensure specificity of the antisera, cells treated with 25 μM tBHQ (wt+tBHQ) or arginine-free medium (wt-Arg) for 24 h were included in some experiments (wt+ tBHQ: anti-ATF4 in two, anti-Nrf2 in four, wt-arg in two). Representative western blots are shown below the graphs. Note the higher molecular weight of ATF4 in HT22-R cells. (f) EMSA shows increased binding of nuclear proteins from HT22-R cells to the AARE present in the xCT promoter. Nuclear extracts from HT22-wt and -R cells were allowed to bind to the radiolabeled AARE and separated by PAGE. The arrow indicates ATF4-specific binding, the asterisk non-specific binding and the arrowhead free unbound probe. (g–i) HT22-R cells were co-transfected with siRNA against ATF4 or control siRNA together with either pcDNA3 (Ctrl) or pcDNA3-xCT (xCT) vector. After 24 h, cells were replated for protein analysis, system xc− activity measurement and oxidative glutamate toxicity. (g) Western blot analysis of transfected HT22-R cells. Nuclear extracts were evaluated by western blot for expression of ATF4 (ATF4) and membrane fractions were evaluated for xCT expression (xCT). Actin served as a loading control. (h) System xc− activity in co-transfected HT22-R cells was measured as glutamate-sensitive 35S-cystine uptake. (i) Survival in response to oxidative glutamate toxicity in co-transfected HT22-R cells. Cells in 96-well plates were treated with the indicated concentrations of glutamate for 24 h and survival measured by the MTT assay. (g–i) All graphs represent data of the same four consecutive transfections as mean±S.E.M. Representative western blots are shown in (g). Results obtained by transfection with both control siRNA and control vector were normalized to 1 in (g) or 100% in (h). Viability of cells not treated with glutamate was normalized to 100% in (i). Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA (a–c, e, g, h) or two-way ANOVA (i) with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons post test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with HT22-wt (a–e). (g–i) *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with HT22-R cells transfected with control siRNA and control vector, #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 compared with cells transfected with ATF4 siRNA and control vector

The upregulation of xCT mRNA in the HT22-R cells (Figure 1b) suggested that xCT is induced in these cells by increased transcription. This is supported by reporter luciferase assays with a 4700 bp xCT-promoter luciferase construct26 that gave a pattern of relative luciferase to β-galactosidase activity ratios in HT22-wt, tBHQ-treated HT22-wt cells and HT22-R cells similar to that for system xc− activity and xCT expression (Figure 2c). Next, we transfected HT22-wt and HT22-R cells with xCT promoter luciferase constructs consisting of fragments of different lengths. The difference in promoter activity between HT22-R and HT22-wt cells was already maximal with the 94-bp xCT promoter luciferase construct, whereas no activity was seen with the 93-bp promoter construct (Figure 2d). This one base pair deletion disrupts an ATF4-binding AARE in the xCT promoter stretching from −94 to −86 bp.18 Thus, we examined ATF4 and Nrf2 expression in HT22-wt and -R using antibodies the specificity of which we demonstrated using mouse embryonic fibroblasts derived from ATF4 and Nrf2 knock out mice (Supplementary Figure 2A). Indeed, ATF4 levels in the HT22-R cells were sixfold higher as compared with the HT22-wt cells. Of note, ATF4 in the HT22-R cells showed a ∼5 kD higher apparent molecular weight compared with the HT22-wt cells (Figure 2e, left panel). In contrast, Nrf2 expression was not increased in the HT22-R cells (Figure 2e, right panel) nor was the expression of the downstream target of Nrf2, heme oxygenase-1 (Supplementary Figure 2B). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) showed markedly increased binding of nuclear protein complexes to the AARE of the xCT promoter in the HT22-R cells as compared with the HT22-wt cells (Figure 2f), which was supershifted and reduced in the presence of an ATF4 antibody (Supplementary Figure 2C).

To confirm that the slightly higher molecular weight band really represents ATF4 and that ATF4-dependent xCT expression mediates the resistant phenotype in HT22-R cells, we transfected HT22-R cells with siRNA against ATF4 together with either empty vector or a vector expressing xCT. The ATF4 siRNA effectively downregulated high molecular weight ATF4 protein (Figure 2g, left panel). Moreover, it led to an ∼70% downregulation of xCT protein, which was partially (∼44%) but significantly reversed by co-transfection with xCT (Figure 2g, right panel). The ATF4 siRNA-induced reduction of system xc− activity was rescued by ∼23% by transient overexpression of xCT (Figure 3h). Thus, ATF4 is involved in the induction of system xc− in HT22-R cells. As the effect of ATF4 downregulation can be partially overcome by xCT transfection, xCT expression is limiting for system xc− activity under these conditions. However, as transient overexpression of xCT protein only increased system xc− activity with a 53% efficacy, reduced 4F2hc levels might contribute to the reduction of system xc− activity upon ATF4 knockdown by siRNA. Moreover, ATF4 siRNA significantly increased the sensitivity of the HT22-R cells to glutamate (Figure 2i). Again, transfection with xCT partially reversed the effect of the ATF4 siRNA. Similar effects on ATF4 protein levels, xCT expression, system xc− activity and glutamate sensitivity were obtained with a second independent siRNA (Supplementary Figure 3), supporting the specificity of the observed effect. Thus, ATF4 is involved in the upregulation of xCT in HT22R cells and this pathway modulates glutamate sensitivity of the HT22-R cells.

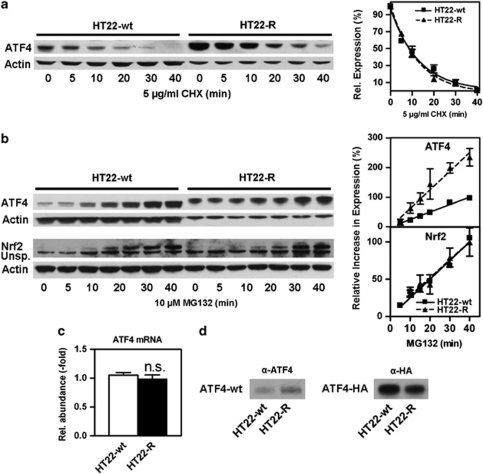

Figure 3.

ATF4 in HT22-R cells has the same half-life and a higher synthesis rate as ATF4 in HT22-wt cells, and the higher molecular weight is not due to post-translational modification. (a) HT22-wt and HT22-R cells were treated with 5 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed by western blotting with an antibody against ATF4. Actin served as a loading control. Samples of HT22-R cells were diluted 1 : 3 to adjust for higher ATF4 expression. A representative western blot is shown. The graph represents pooled data from three independent protein preparations with the ATF4/actin ratio without protein synthesis inhibition normalized to 100% as mean±S.E.M. Non-linear regression was performed using one phase exponential decay. (b) HT22-wt and HT22-R cells were treated with 10 μM MG132 for the indicated times and whole-cell extracts were analyzed for ATF4 and Nrf2 expression. For ATF4, HT22-R samples were diluted 1 : 3 to adjust for higher basal ATF4 levels. An unspecific band obtained with the Nrf2 antibody is indicated (Unsp.). The graphs represent three and seven independent experiments for ATF4 and Nrf2, respectively. ATF4 expression was normalized to actin and the relative increase in ATF4 protein was calculated by subtraction of the baseline ATF4/actin ratio at 0 min. ATF4 or Nrf2 to actin ratios obtained in HT22wt cells at 40 min were normalized to 100% for every single experiment and the graphs show the mean±S.E.M. of pooled and normalized data. Statistical analysis was performed by linear regression. (c) qPCR on HT22-wt and HT22-R cDNA shows equal expression of ATF4 mRNA in both the cell lines. The graph represents the mean±S.E.M. of three independent experiments. (d) Recombinant ATF4 does not have a higher molecular weight in HT22-R cells. HT22-wt and HT22-R cells were transfected with wild-type-ATF4 in the pRK7 vector (ATF4-wt) or ATF4-HA. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed by western blotting using antibodies against ATF4 (α-ATF4) or HA (α-HA). For detection of overexpressed ATF4-wt only, samples of HT22-wt and HT22-R cells were diluted 1 : 80 and 1 : 20, respectively, until endogenous ATF4 was undetectable in mock-transfected control cells (not shown). The experiment was done three times with identical results

Increased ATF4 protein production mediates ATF4 upregulation in HT22-R cells

For the most part, ATF4 expression is regulated at the level of translation.23 However, modulation of ATF4 protein degradation by post-translational modifications has also been described.28, 29 To test whether the high molecular weight ATF4 is upregulated by reduced degradation, we treated HT22-wt and HT22-R cells with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, and evaluated the decay of ATF4 protein levels over time (Figure 3a). Quantitative evaluation normalized to actin protein levels showed a single exponential decay of ATF4 protein levels with an identical half-life in HT22-wt and HT22-R cells of 9.0 min (95% CI: 6.5–14.4) and 8.7 min (95% CI: 7.2–11.1), respectively. We next investigated whether ATF4 protein production is increased in the HT22-R cells by blocking proteasomal degradation29 with 10 μM MG132 and analyzing ATF4 protein levels compared with actin by western blotting (Figure 3b). Quantitative evaluation showed that the relative increase of ATF4 was ∼2.5-fold higher in the HT22-R cells as compared with the HT22-wt cells (95% CI: HT22-R 4.4–8.1%/min, HT22-wt 2.2–2.8%/min). For control purposes, we analyzed Nrf2 protein accumulation, which showed no difference between the two cell lines (Figure 3b, lower panel). However, quantitative real-time PCR showed equal expression of ATF4 mRNA in both the cell lines (Figure 3c). Next, we transiently transfected HT22-wt and HT22-R cells with plasmids encoding wild-type ATF4 (ATF4-wt) or HA-tagged ATF4 (ATF4-HA). Both the recombinant proteins showed an identical apparent molecular weight when expressed in both HT22-R and HT22-wt cells (Figure 3d). Thus, post-translational modifications do not result in the increased molecular weight of ATF4 in HT22-R cells.

The large ATF4 isoform in HT22-R is regulated differently from ATF4 in HT22-wt cells

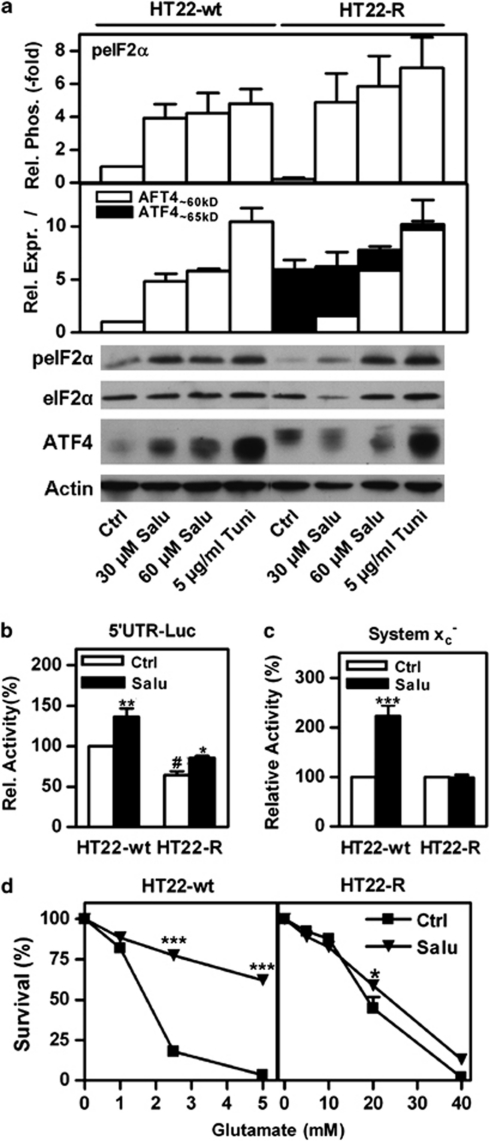

Phosphorylation of eIF2α at serine51 increases ATF4 protein levels via a translational mechanism.23 Interestingly, basal levels of eIF2α phosphorylation tended to be lower in the HT22-R cells as compared with the HT22-wt cells, but eIF2α phosphorylation was readily stimulated by salubrinal, a specific inhibitor of eIF2α dephosphorylation30 or the ER stress inducer tunicamycin in both the cell lines (Figure 4a, upper panel). As expected, ATF4 protein levels in the HT22-wt cells were increased by both salubrinal and tunicamycin. In contrast, both compounds downregulated high molecular weight ATF4 while inducing ‘classical' ATF4 protein in HT22-R cells (Figure 4a, lower panel). As a consequence, the total ATF4 protein levels in HT22-R cells were relatively unchanged upon induction of eIF2α phosphorylation.

Figure 4.

The high molecular weight and ‘classical' ATF4 isoforms are inversely regulated by eIF2α phosphorylation. (a) Whole-cells extracts of HT22-wt and HT22-R cells treated with either vehicle (Ctrl) or salubrinal (Salu) at the indicated concentrations for 24 h or 5 μg/ml tunicamycin (Tuni) for 2 h were analyzed for eIF2α phosphorylation (peIF2α) relative to eIF2α expression and expression of the ‘classical' and high molecular weight ATF4 isoforms (ATF4∼60 kD and ATF4∼65 kD, respectively) relative to actin. Relative eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression were normalized to those in HT22-wt cells treated with vehicle. (b) HT22-wt and HT22-R cells were co-transfected with a luciferase construct fused to the ATF4 5′UTR and the pSV-β-GAL vector. Cells were treated either with vehicle (Ctrl) or 60 μM salubrinal (Salu). The luciferase/β-galactosidase ratio of untreated HT22-wt cells was normalized to 100%. (c and d) HT22-wt or HT22-R cells were treated with 30 μM Salubrinal (Salu) or vehicle (Ctrl) for 24 h. (c) System xc− activity was measured as HCA-sensitive sodium-independent 3H-glutamate uptake. Uptake in vehicle-treated cells was normalized to 100%. (d) Cells in 96-well plates were treated with glutamate at the indicated concentrations for 24 h in quadruplicate. Viability was measured by the MTT assay and relative survival calculated by normalizing to the MTT value of cells not treated with glutamate. The graphs show data from three (a and d) or four (b and c) independent experiments as mean±S.E.M. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post test, *P<0.05. **P<0.01,***P<0.001 compared with control cells, #P<0.05, HT22-R cells compared with HT22-wt without salubrinal. Representative blots are shown below the graphs in (a)

To substantiate our finding that ATF4 translation via eIF2α phosphorylation is reduced in the HT22-R cells, we transfected HT22-wt and HT22-R cells with a luciferase construct fused to the 5′UTR of ATF4.31 Relative luciferase/β-galactosidase ratios were significantly lower in the HT22-R cells as compared with the HT22-wt cells but similarly increased by salubrinal treatment (Figure 4b).

eIF2α phosphorylation modulates system xc− expression in HT22-wt but not in HT22-R cells

To provide further evidence that ATF4 levels are crucial determinants for expression of system xc− and subsequent resistance against oxidative stress and that the observed differential regulation of the two ATF4 isoforms is functionally important, we treated HT22-wt and HT22-R cells with 30 μM salubrinal for 24 h and measured system xc− activity and sensitivity to glutamate (Figure 4d). In HT22-wt cells, salubrinal increased system xc− activity to ∼220% of vehicle-treated cells, whereas system xc− activity was unchanged by the identical treatment in HT22-R cells. Moreover, in HT22-wt cells, salubrinal increased the EC50 of glutamate ∼9.2-fold, whereas in the HT22-R cells the EC50 of glutamate was increased only ∼1.2-fold. Thus, the differential ability of salubrinal to modulate total ATF4 protein levels and system xc− in both the cell lines corresponds to the salubrinal-induced changes in the resistance against oxidative glutamate toxicity.

High molecular weight ATF4 is a consequence of a 13-bp deletion in one allele of the ATF4 gene resulting in a uORF2–ATF4 fusion protein

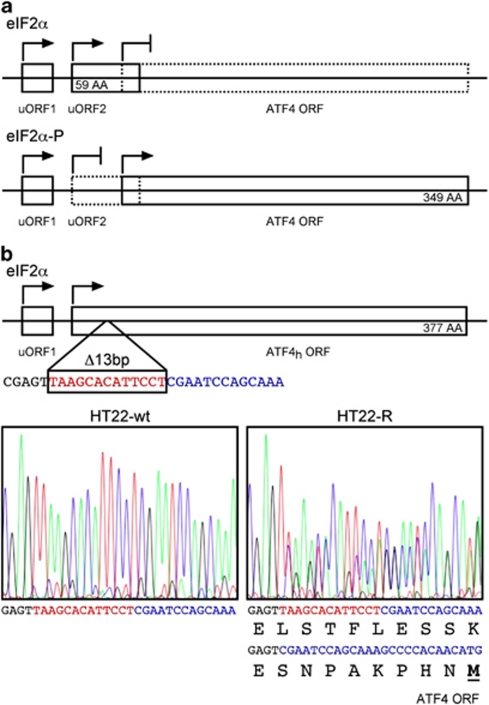

To understand the molecular basis of the high molecular weight ATF4, we amplified and sequenced full-length ATF4 cDNA including the uORF1, uORF2 and ATF4 ORF (Figure 5a) derived from HT22-wt and HT22-R cells. This revealed a 13-bp deletion of nucleotides 560–573 according to the NCBI reference sequence (GenBank accession #NM_009716.2) in ∼50% of the cDNA of the HT22-R cells, indicating a heterozygous state of the mutation (Figure 5b). This mutation causes a frame shift leading to an open reading frame encoding the first 20 amino acids (AAs) of uORF2, eight aberrant AAs and the full length ATF4 protein, which increases the size of the ATF4 protein from 349 to 377 AAs consistent with the observed increase in size on western blots.

Figure 5.

High molecular weight ATF4 is the result of a 13-bp deletion within uORF2 in one allele of the ATF4 gene. (a) Scheme of ATF4 mRNA with uORF1, uORF2 and the ATF4 ORF. When eIF2α phosphorylation is low, uORF2 is preferentially translated (upper), whereas the ATF4 ORF is preferentially translated in the presence of high eIF2α phosphorylation. (b) A 13 bp deletion (red) in uORF2 leads to fusion of uORF2 and the ATF4 ORF. The high molecular weight ATF4 (ATF4h) ORF encodes a 377 AA protein. The eight new AAs that are encoded by uORF2 due to the frame shift are shown in green. The color reproduction of this figure is available at the Cell Death and Differentiation journal online

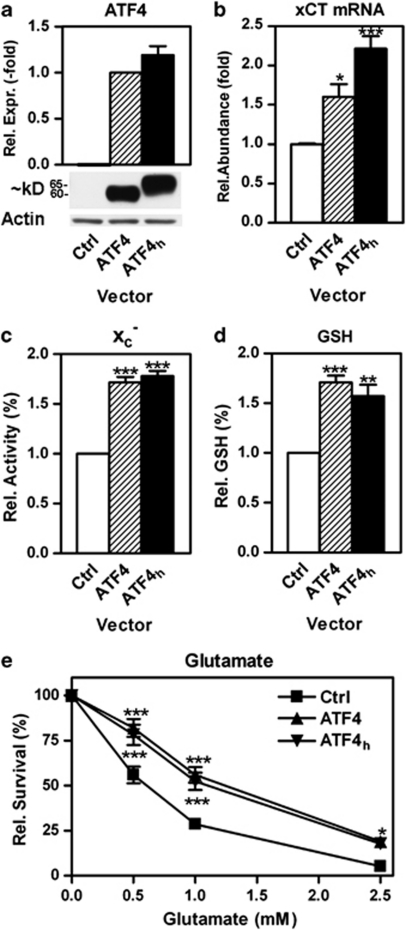

Mutant and ATF4-wt equally induce system xc− activity, increase GSH and protect against oxidative glutamate toxicity

Transient overexpression of ATF4 in HT22 cells increases system xc− activity and GSH levels and protects against oxidative glutamate toxicity.19 To prove that the 13 bp deletion leads to the expression of the high molecular weight ATF4 and that this protein has similar properties as regular ATF4, we transiently overexpressed either ATF4-wt or high molecular weight ATF4 in HT22-wt cells. Indeed, overexpression of the mutated sequence led to the expression of a ∼65 kD protein recognized by the ATF4 antibody (Figure 6a) and increased xCT mRNA, system xc− activity and GSH levels and protected against glutamate similarly to ATF4-wt (Figures 6b–e).

Figure 6.

Wild-type and high molecular weight ATF4 equally induce system xc− activity, elevate cellular GSH levels and protect HT22 cells against oxidative glutamate toxicity. HT22-wt cells were transiently transfected with a vector encoding ATF4-wt (ATF4), high molecular weight ATF4 (ATF4h) or empty pRK7 vector (Ctrl). (a) Western blotting shows similar expression of ATF4 and ATF4h upon transfection. ATF4 and ATF4h increase (b) xCT mRNA expression when quantified by qPCR and (c) system xc− activity measured as HCA-sensitive uptake of radiolabeled glutamate. Overexpression of ATF4 and ATF4h increase (d) total GSH and (e) resistance against oxidative glutamate toxicity. (e) At 24 h after plating, HT22-wt cells transfected with empty vector (Ctrl), ATF4-wt (ATF4) or high molecular weight ATF4 (ATF4h) were exposed to the indicated concentrations of glutamate and viability was quantified by the MTT assay 24 h later. Graphs show the results of (b) two experiments each performed in triplicate or three (a, c, e) or five (d) independent experiments. (a) ATF4h expression was normalized to ATF4 expression after correction for actin expression as a loading control. (b and c) xCT mRNA was corrected for HRPT and actin β expression, system xc− activity and GSH were corrected for total protein and results were normalized to HT22-wt cells transfected with empty pRK7. (e) Viability at 0 mM glutamate was normalized to 100%. Statistical analysis was performed by (b and c) one-way ANOVA or (e) two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons post test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with HT22-wt transfected with empty vector

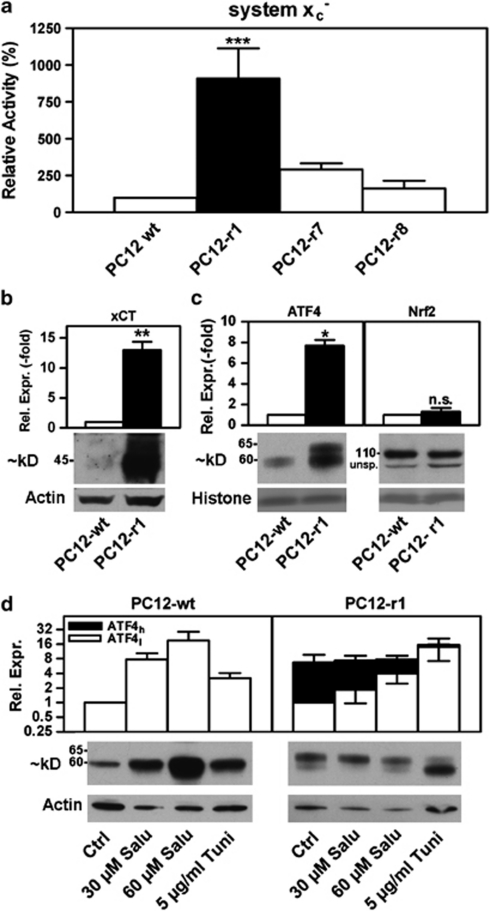

High molecular weight ATF4 due to a 1bp deletion is expressed in clonal Aβ-resistant PC12 cells that show a prominent upregulation of system xc− activity

We then investigated whether similar changes could be observed in the more disease-related paradigm of resistance against Aβ. Aβ is one of the key factors in the pathogenesis of AD and induces oxidative stress.7 The characteristics of the three sublines PC12 cells selected for resistance against Aβ toxicity were reported previously.7, 8 Among the three sublines, PC12-r1, PC12-r7 and PC12-r8, PC12-r1 cells showed the most prominent upregulation of system xc− activity with an approximately ninefold increase in system xc− activity (Figure 7a). The prominent upregulation of system xc− activity in the PC12-r1 cells is consistent with an ∼13-fold upregulation of xCT protein expression (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

System xc− activity, xCT protein and a high molecular weight ATF4 isoform with similar properties as in HT22-R are upregulated in clonal PC12 cells selected for resistance against amyloid-β peptide. (a) Wild-type PC12 (PC12-wt) and clones 1, 7 and 8 of Aβ-resistant PC12 cells (PC12r1, PC12r7, PC12r8) were plated in 24-well dishes and system xc− activity was measured as glutamate-sensitive 35S-cystine uptake. Uptake was normalized to PC12-wt cells. The graph represents five independent experiments, two of which included PC12-r8, as mean±S.E.M. (b and c) PC12-wt and PC12-r1 cells were fractionated and (b) membrane protein analyzed for xCT expression and (c) nuclear extracts analyzed for ATF4 and Nrf2 expression by western blotting. Western blotting against actin (b) or the histone band visualized by Poinceau S-staining (c) served as loading controls. Nrf2 runs at ∼110 kD. An unspecific band is indicated (unsp.). The graphs represent the results of three (b) and four (c) independent protein preparations with the relative expression in PC12-wt cells normalized to 1 as mean±S.E.M. Statistical analysis was performed by (a) one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons post tests (PC12-r1 compared with -wt, -r7 and -r8 ) or (b and c) one sample sample t test compared with 1, *P<0.05, **P<0.01,***P<0.001, n.s.=not significant. (d) PC12-wt and PC12-r1 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and treated as for HT22 cells in Figure 4. Nuclei were analyzed by western blotting for ATF4 expression. Actin served as a loading control. Expression levels of low (clear boxes, ATF4l) and high (black boxes, ATF4h) molecular weight ATF4 isoforms were analyzed by densitometry. ATF4l expression in control cultures was normalized to 1 for both the cell lines, and ATF4h levels in PC12r1 are given relative to ATF4l expression in controls. The graph represents five (PC12-wt) and seven (PC12-r1) independent experiments. Representative western blots are shown below

Western blotting of nuclear extracts of PC12-r1 cells revealed not only an approximately eightfold increase of ATF4 protein compared with PC12-wt cells but also a second, larger band similar to the high molecular weight ATF4 in HT22-R cells, whereas Nrf2 levels were not different from wild-type cells (Figure 7c). Treatment with tunicamycin and salubrinal resulted in a similar pattern of high molecular weight ATF4 regulation in PC12-r1 cells as in HT22-R cells (Figure 7d). Sequence analysis of the region of the PC12-wt and -R1 ATF4 cDNA showed a 1-bp deletion in a stretch of five guanosines in 50% of the amplified PC12-r1 cDNA in the region where uORF2 and the ATF4 ORF overlap (Figure 8a). This resulting frame shift leads to a predicted fusion protein consisting of the 58 N-terminal AA of uORF2 followed by the ATF4 peptide lacking the first 26 AAs with a total length of 379 AAs (Figure 8b).

Figure 8.

A 1-bp deletion in the uORF2 leads to the high molecular weight ATF4 in PC12r1 cells. A 1-bp deletion (red) in the region where uORF2 and the ATF4 ORF overlap leads to fusion of uORF2 and the ATF4 ORF. The high molecular weight ATF4 (ATF4h) ORF encodes a 379 AA protein consisting of the 58 N-terminal AAs of uORF2 and the ATF4 ORF lacking the first 26 AAs. The color reproduction of this figure is available at the Cell Death and Differentiation journal online

Discussion

Insight into the regulation of system xc− expression might be crucial to understanding the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases associated with oxidative stress as well as the invasive growth of tumors and their sensitivity to anticancer drugs. We therefore investigated the mechanism of the previously reported prominent upregulation of system xc− in glutamate-resistant HT22 cells.9 Herein, we show convincingly that upregulation of xCT mediates the resistant phenotype as knockdown of xCT by miRNA and siRNA, as well as pharmacological inhibition of system xc− greatly weakens the resistant phenotype of HT22-R cells. Importantly, upregulation of system xc− is not specific for HT22-R cells, as we demonstrate that clonal PC12 cells selected for resistance against Aβ toxicity, which induces oxidative stress via production of hydrogen peroxide,7 show a similar upregulation of xCT protein and system xc− activity (this report and Lewerenz and Maher19). Resistance against oxidative glutamate and Aβ toxicity was found to be associated with reciprocal cross-resistance,32 and transient overexpression of xCT induces resistance against oxidative glutamate toxicity and hydrogen peroxide.9 Thus, distinct selection pressures appear to favor the growth of cells with similar over-activation of more broadly protective pathways. In line with this hypothesis that upregulation of system xc− is a more general cytoprotective phenomenon, system xc− expression levels inversely correlate with the sensitivity of tumor cells to anticancer drugs.17

Activation of Nrf2 regulates xCT expression in response to treatment with classical Nrf2 inducers26, 27 and is therefore considered to be the main regulator of xCT levels in cells. However, in our hands neither HT22-R cells nor Aβ-resistant PC12 cells showed higher levels of Nrf2 expression. Instead, multiple lines of evidence indicate that ATF4 is the key factor for xCT and system xc− upregulation in the HT22-R cells, and that this change is critical for protection from oxidative stress. First, xCT and 4F2hc, both of which are known to be induced by ATF4,18, 20 are simultaneously upregulated in the HT22-R cells. Second, over-activity of the xCT promoter in HT22-R cells as compared with HT22-wt cells relies on the integrity of the proximal AARE to which ATF4 is known to bind.18 Third, EMSAs demonstrated increased binding of ATF4 to this AARE in HT22-R cells. Fourth, nuclear ATF4 protein levels are sixfold higher in HT22-R cells. Fifth, siRNA-mediated knockdown of ATF4 in the HT22-R cells downregulates xCT expression and system xc− activity, and increases sensitivity to oxidative glutamate toxicity which is partially reversed by xCT overexpression. We showed previously that ATF4 increases system xc− activity, and resistance against oxidative glutamate and Aβ toxicity.19 Furthermore, fibroblasts derived from ATF4 knock-out mice were shown to be uniquely sensitive to oxidative stress.20 Conversely, high ATF4 levels were found in cancer cell lines resistant to anticancer drugs.25 Taken together, these results suggest that ATF4 might be a more general survival factor, particularly, through its effects on system xc−.

Both the cell lines with a prominent upregulation of system xc− activity, HT22-R and PC12r1 cells, show an upregulation of an ATF4 protein with an ∼5 kD higher apparent molecular weight. The molecular basis of the atypical ATF4 protein is mutations in the region encoding uORF2 that lead to a frame shift of −1 bp and subsequently uORF2/ATF4 fusion proteins. The N-terminal sequence encoded by uORF2 not only explains the shift in molecular weight but also the fact that both the proteins are upregulated under basal conditions, which favor reinitiation at uORF2, and downregulated by eIF2α phosphorylation, which decreases translation reinitiation at uORF2.23 We show that both the proteins, ATF4-wt and high molecular weight ATF4, have similar properties with respect to the induction of system xc− activity, increasing cellular GSH levels and protecting against oxidative glutamate toxicity. ATF4 expression actively decreases eIF2α phosphorylation via a feed-back loop inducing expression of GADD34, the stress-induced eIF2α phosphatase subunit.33 So, mutant ATF4 might suppress expression of ‘classical' ATF4 by the non-mutated allele by decreasing translation of the ATF4 ORF as indicated by our luciferase reporter constructs with the 5′ end of the ATF4 mRNA linked to luciferase.

ATF4 has been described as protective20, 34, 35 as well as pro-apoptotic.34, 35, 36 Our observation that two different forms of oxidative stress-based selection pressure in cells from two different species result in similarly mutated ATF4 substantiate the hypothesis that ATF4 is an important regulator of oxidative stress resistance. As the mutations described herein uncouple the expression of ATF4 from increased eIF2α phosphorylation, our data demonstrate that ATF4 can be a protective protein acting independently of eIF2α phosphorylation. We hypothesize that similar mutations might occur in cancer cells either as an adaptive mechanism to the pro-oxidant tumor microenvironment6 or underlie GSH-mediated chemoresistance associated with xCT upregulation.17 Of note, a similar but not identical ATF4 mutation within the region where uORF2 and the ATF4 ORF overlap to those reported by us was found in a mouse teratoma cell line.37 Interestingly, mutations in Nrf2, the other nuclear factor that upregulates xCT, have been described recently in ∼10% of patients with lung cancer.38 This underscores that hypothesis that somatic mutations that boost GSH synthesis support cancer growth and progression. Further studies will explore whether ATF4 mutations similar to those described here are relevant in cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and viability assays

HT22 cells (HT22-wt) were cultivated at 37 °C in a 10% CO2 atmosphere and DMEM containing 10% FCS (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), 2 mM glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were passaged by dissociation with 0.05% trypsin and 0.2% EDTA every other day. For viability assays, 2500 cells were seeded in 100 μl into 96-well plates. To induce cell death, glutamate was added 24 h after plating for 24 h. Salubrinal (Axxora, San Diego, CA, USA) was added during plating. Cell survival was judged by phase contrast microscopy and assayed by the MTT method as described previously9 in at least three independent experiments. Glutamate-resistant HT22 (HT22-R) cells were identical to those described previously9 and were maintained by passage in a medium supplemented with 10 mM glutamate. For experiments, HT22-R cells were plated without glutamate.

Aβ-resistant clonal PC12 cells, PC12r1, PC12r7 and PC12r8 were described previously.7, 8, 10 Wild-type and Aβ-resistant PC12 cells were grown in high-glucose DMEM with 10% horse serum (Hyclone) and 5% fetal calf serum (Hyclone). Cells were split once a week after dislodgement by repeated pipetting.

Measurement of system xc− activity

HT22 or PC12 cells (3 × 104 cells/well) were plated in 24-well dishes and grown for 24 or 48 h, as indicated. In some experiments, HT22 cells were treated with 25 μM tBHQ, 30 μM salubrinal or vehicle. Cells were washed three times with sodium-free Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS). Uptake was performed in triplicate with 25 μM 35S-cystine (Perkin Elmer NEN, Waltham, MA, USA) for 20 min at 37 °C. To specifically measure system xc− activity, 10 mM glutamate was added to parallel wells in triplicate. Cells were washed three times with ice-cold sodium-free HBSS and lysed in 0.2 N NaOH. Radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation counting. Radioactivity was normalized to protein measured by the Bradford assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). As 35S-cystine became unavailable during the course of these experiments, system xc− activity in HT22 cells treated with salubrinal was measured as sodium-insensitive homocysteic acid (HCA)-sensitive uptake of 3H-glutamate (Perkin Elmer NEN). Cells in triplicate wells were incubated in 10 μM glutamate (3H-glutamate/cold glutamate 1 : 1000) with or without 1 mM HCA adjusted to pH 7.4 in sodium-free HBSS.

Enzymatic measurement of total GSH

For measurement of GSH, 1.65 × 105 HT22-wt and -R cells were plated in 60-mm dishes. After 24 h, cells were scraped into ice-cold PBS, and 10% sulfosalicylic acid was added at a final concentration of 3.3%. GSH was assayed as described39 and normalized to protein recovered from the acid-precipitated pellet by treatment with 0.2 N NaOH at 37 °C overnight and measured by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce).

Protein preparation

For western blotting, either whole-cell extracts of HT22 cells or purified membranes and nuclear fractions of HT22 or PC12 cells were used. For cell fractionation, 4.4 × 105 HT22-wt and HT22-R cells or 1.2 × 106 wild-type PC12 cells and 6 × 105 PC12r1 cells per 100 mm dish grown for 48 h were used. Where indicated, HT22-wt cells were treated with 25 μM tBHQ for 24 h. Cystosolic, membrane and nuclear fractions were obtained as described previously.40 Protein in the different fractions was quantified by the BCA assay (Pierce) and adjusted to equal concentrations. 5 × Western blot sample buffer (74 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 6.25% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol) was added to a final concentration of 2.5 × , and samples were boiled for 5 min.

For whole-cell extracts, HT22-wt and HT22-R cell were plated in 60-mm dishes at a density of 3.3 × 105 cells/well and grown for 24 h. Cells were treated with salubrinal or tunicamycin at the indicated concentrations for the indicated times and then rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS and scraped into lysis buffer consisting of 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 × protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Cells were sonicated on ice and centrifuged. The protein concentrations of the supernatants were measured by the BCA assay and equal amounts were boiled for 5 min in 2.5 × western blot sample buffer. Cells treated with 10 μM MG132 or 5 μg/ml cycloheximide were directly lysed into 2.5 × western blot sample buffer and boiled.

Western blotting

SDS-PAGE and western blotting was performed as previously described.19 The primary antibodies used were: rabbit anti-phospho-51Ser-eIF2α (#9721, 1/1000) and rabbit anti-eIF2α (#9722, 1/500) from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA), rabbit anti-ATF4 (#sc-200, 1/500), rabbit anti-Nrf2, (#SC13032, 1/1000) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA), mouse anti-actin, (#A5441, 1/200,000) from Sigma-Aldrich, rabbit anti-heme oxygenase-1 (#SPA-896, 1/5000) from Stressgen (Victoria, Canada) and rabbit anti-xCT (1/1000, a generous gift from Sylvia Smith, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta). For relative eIF2α phosphorylation, parallel blots were performed. For all other antibodies, the same membrane was reprobed for actin. Poinceau S-stained membranes and autoradiographs were scanned using a BioRad GS800 scanner (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Band density was measured using the manufacturer's software. Relative eIF2α phosphorylation was calculated as the ratio of band densities obtained by the phospho- and the pan-eIF2α antibodies. Relative expression of the other proteins was normalized to actin band density with the exception of the comparison between wild-type and resistant PC12 cells, which express highly different amounts of non-membrane-associated actin41 that sediments with the nuclear fraction using our technique. Here, relative expression was normalized to histone band density obtained by scanning the Poinceau S-stained membranes. Each western blot was repeated at least three times with independent protein samples.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

The EMSAs were performed as reported previously.42 Cells in 60-mm dishes from the same density cultures as used for the cell death assays were washed twice in cold Tris-buffered saline and nuclei prepared. The nuclei were extracted by 15 min vigorous shaking at 4 °C in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT and 1 mM PMSF, the supernatant was collected following centrifugation and stored at −70 °C. EMSA analysis was performed using a kit from Promega (Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, equal amounts of protein (5–10 μg) were pre-incubated for 10 min at room temperature in gel shift binding buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 4% glycerol, 0.05 mg/ml poly(dI-dC) poly and then 1 μl of 32P-labeled AARE probe (5′-GTGGCTGATGCAAACCTG-3′, nt −99 to −82, from Bioneer (Alameda, CA, USA); labeled to 2000 c.p.m./femtomole) was added for 20 min. The complexes were analyzed by electrophoresis through a Novex 6% DNA retardation gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and autoradiography. In some experiments, either unlabeled AARE probe or antibodies to ATF4 (Santa Cruz; sc-200 × , 1/5-1/10) were included in the pre-incubation mix.

Transfection and luciferase reporter assays

For transfection with xCT siRNA, Dharmafect 2 (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA) was used. Cells in 6-well plates were transfected with 100 pmol siRNA. The sequences for the two different siRNAs were: xCT siRNA #1: 5′-UAUGCUUGUACCUAAUUCUUU-3′, siRNA #2: 5′-UAGCUCCAGGGCGUAUUACUU-3′. siRNA and Dharmafect 2 in a ratio of 1 : 25 were diluted separately in Optimem, combined after 5 min incubation time and incubated for another 10 min to allow complex formation. The solution was diluted 1 : 5 in antibiotic-free medium and exchanged for the growth medium. Cells were monitored for gene expression and used for further experiments 48 h post transfection. For transfection with vectors expressing miRNAs specific for xCT the BLOCK-iT Pol II miR RNAi Expression Vector Kit (Invitrogen) was used according to the manual. The target sequences for xCT were: miRNA #1, 5′-TATGCATATGCTGGCTGGTTT-3′ and miRNA #2: 5′-ACTCCTCTGCCAGCTGTTATT-3′. The control plasmid provided by the manufacturer, which contains an insert that can form a hairpin structure that is processed into mature miRNA, but is predicted not to target any known vertebrate gene, was used as control.

For promoter assays, HT22 cells were plated at a density of 1.65 × 105 cells/well in 60-mm dishes and grown for 24 h. Medium was exchanged by 2.5 ml fresh growth medium and cells were transfected with 2 μg pSV-β-Gal (Promega), 2 μg xCT promoter luciferase construct18 and 2.5 μl lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 6 h. To measure translational activity of the ATF4 5′UTR, luciferase reporter promoter constructs were replaced by a vector containing the ATF4 5′ UTR and AUG fused to luciferase by the TK promoter in a pGL3 backbone (a generous gift from David Ron, Skirball Institute for Biomolecular Medicine, New York). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were lysed in 1 × reporter lysis buffer (Promega) and enzyme activities were measured by luminescence using the Beta Glo and Luciferase Assay Systems, respectively (Promega) on a luminometer from Molecular Devices (Madison, WI, USA). The luciferase/β-galactosidase ratio for each condition and cell line was normalized to the ratio obtained by transfection with pGL3 and pSV-β-Gal for the same condition and cell line.

For co-transfection with ATF4 siRNA and xCT, HT22-R cells were plated at a density of 4.4 × 105 cells/100 mm dish and grown for 24 h. Medium was exchanged by 5 ml fresh growth medium and cells were transfected with 4 μg pcDNA3pciNeo or pcDNA3pciNeo-xCT vector,9 80 pmol ATF4 siRNA (#sc-35113) or control siRNA (#sc-37007), both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and 5 μl lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 6 h. After 24 h, cells were replated for three different assays performed in parallel: 8.8 × 105 cells in 100-mm dishes for protein preparation, 3 × 104 cells/well in 24-well plates for 35S-cystine uptake and 2.5 × 103 cells/well in 96-well plates for oxidative glutamate toxicity, respectively. Cells were harvested or glutamate was added 24 h after replating. For comparison of siRNAs, cells were also transfected with an ATF4-specific siRNA from Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA) (#SI00905905).

Transient overexpression of ATF4 was performed as reported previously.19 The plasmid encoding an ATF4-HA was a generous gift from Florence Margottin-Goguet, Institut Cochin de Génétique Moléculaire, Paris, France. Mutant and ATF4-wt was amplified from HT22-R and –wt cell cDNA by PCR using the forward primer 5′-GCAGCAGCACCAGGCTCT-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-TTTTATTAAACTTTCTGGGAGATGG-3′, which amplify a 590 bp product in HT22-R and a 577 bp product in HT22-wt cells, which include the 5′ UTR. After subcloning into pGEM T-easy (Promega), fragments of this amplification product were excised with HindIII/MfeI and cloned into the pRK7-ATF4 vector that was described before.19

Reverse transcription, PCR, sequencing and qPCR

Total RNA from HT22-wt and -R and PC12-wt and -r1 cells was prepared using the RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was performed using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's manual. Mouse full-length ATF4 cDNA including uORF1 and uORF2 was amplified by PCR using Platinum Taq High Fidelity (forward primer: 5′-AGGCTATAAAGGGCGGGTTT-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CAAGCACAAAGCACCTGACT-3′). For the design of rat ATF4 primers, the 5′ end of the NCBI rattus norvegicus ATF4 mRNA reference sequence (GenBank accession #:NM_024403.1) was used for BLAST search (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) for rat ESTs, which yielded an EST (GenBank accession #:DN933785.1) that extended the ATF4 sequence 195 bp more 5′. The sequence containing uORF2 and the 5′ end of the ATF4 ORF overlapping uORF2 was amplified by PCR (forward primer: 5′-GGCGTATTAGAGGCAGCAGA-3′, reverse primer: 5′- CATCCATAGCCAGCCATTCT-3′). Sequencing from both the sides using the primers used for PCR was performed by Eton Biosciences, Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed using Taqman technology with Fam/Dark-quencher probes from the universal Probelibrary (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) or individually designed Fam/Tamra probes (MWG, Ebersberg, Germany) on an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System using the thermocycling conditions proposed by the manufacturer (ABI, Weiterstadt, Germany). Real-time PCR reactions were carried out at a final concentration of 300 nM for forward and reverse primers, and 250 nM for the Taqman probes. Each reaction contained 2 μl containing about 60 ng of cDNA, 12.5 μl of the TaqMan universal PCR Master Mix (ABI) in an individual reaction volume of 20 μl. β-Actin and HPRT served as endogenous control genes and showed no differential expression in HT22-wt and HT22-R cells. Primers and probes for mouse cDNA were as follows: HPRT: forward 5′-GTTGCAAGCTTGCTGGTGAA-3′, reverse 5′-GATTCAAATCCCTGAAGTACTCA-3′, probe FAM-CCTCTCGAAGTGTTGGATACAGGGCA-TAMRA; β-Actin: forward: 5′-CTAAGGCCAACCGTGAAAAG-3′, reverse: 5′-ACCAGAGGCATACAGGGACA-3′, probe 64 (universal ProbeLibrary). ATF4: forward 5′-CGGGTGTCCCTTTCCTCT-3′, reverse 5′-CAGGCACTGCTGCCTCTAAT-3′, probe 49 (universal ProbeLibrary). OAS1: forward 5′-GCATCAGGAGGTGGAGTTTG-3′, reverse 5′-GGCTTCTTATTGATACTACCATGACC, probe 11 (universal ProbeLibrary). OAS2: forward 5′-TCCTATTGGTCAAGCACTGGT-3′, reverse 5′-CTGAGGTGGGGGTGTTTTC-3′, probe 2 (universal ProbeLibrary).

Statistical analysis

Data from independent experiments were normalized to control conditions, pooled and analyzed using the Graph Pad Prism 4 software (La Jolla, CA, USA) followed by appropriate statistical tests.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG stipend LE 1846/2-1 to J.L.), the Fritz-Thyssen-Stiftung (Az10.08.1.174 to J.L. and A.M.) and Alzheimer's Association (IRG-07-58874 to P.M.).

Glossary

- AA

amino acid

- AARE

amino-acid response element

- AD

Alzheimer's dementia

- ATF4-HA

HA-tagged ATF4

- ATF4-wt

wild-type ATF4

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

- HBSS

Hank's balanced salt solution

- HCA

homocysteic acid

- miRNAs

microRNAs

- (S)-4-CPG

(S)-4-carboxyphenylglycine

- tBHQ

tert-butylhydroquinone

- uORF2

upstream open reading frame

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by L Greene

Supplementary Material

References

- Schulz JB, Lindenau J, Seyfried J, Dichgans J. Glutathione, oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:4904–4911. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JD, McLellan LI. Glutathione and glutathione-dependent enzymes represent a co-ordinately regulated defence against oxidative stress. Free Radic Res. 1999;31:273–300. doi: 10.1080/10715769900300851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YH, Di YM, Zhou ZW, Mo SL, Zhou SF. Multidrug resistance-associated proteins and implications in drug development. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37:115–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer FQ, Buettner GR. Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:1191–1212. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. Cellular response to oxidative stress: signaling for suicide and survival. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192:1–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pani G, Galeotti T, Chiarugi P. Metastasis: cancer cell's escape from oxidative stress. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:351–378. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behl C, Davis JB, Lesley R, Schubert D. Hydrogen peroxide mediates amyloid beta protein toxicity. Cell. 1994;77:817–827. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagara Y, Dargusch R, Klier FG, Schubert D, Behl C. Increased antioxidant enzyme activity in amyloid beta protein-resistant cells. J Neurosci. 1996;16:497–505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00497.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewerenz J, Klein M, Methner A. Cooperative action of glutamate transporters and cystine/glutamate antiporter system xc− protects from oxidative glutamate toxicity. J Neurochem. 2006;98:916–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucek T, Cumming R, Dargusch R, Maher P, Schubert D. The regulation of glucose metabolism by HIF-1 mediates a neuroprotective response to amyloid beta peptide. Neuron. 2003;39:43–56. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denko NC. Hypoxia, HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:705–713. doi: 10.1038/nrc2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht P, Lewerenz J, Dittmer S, Noack R, Maher P, Methner A. Mechanisms of oxidative glutamate toxicity: the glutamate/cystine antiporter system x(c)- as a neuroprotective drug target. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9:373–382. doi: 10.2174/187152710791292567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannai S. Exchange of cystine and glutamate across plasma membrane of human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:2256–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Tamba M, Ishii T, Bannai S. Cloning and expression of a plasma membrane cystine/glutamate exchange transporter composed of two distinct proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11455–11458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S, Colin C, Hinners I, Gervais A, Cheret C, Mallat M. System Xc- and apolipoprotein E expressed by microglia have opposite effects on the neurotoxicity of amyloid-beta peptide 1-40. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3345–3356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5186-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaskan NE, Heckel A, Hahnen E, Engelhorn T, Doerfler A, Ganslandt O, et al. Small interfering RNA-mediated xCT silencing in gliomas inhibits neurodegeneration and alleviates brain edema. Nat Med. 2008;14:629–632. doi: 10.1038/nm1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z, Huang Y, Sadee W, Blower P. Chemoinformatics analysis identifies cytotoxic compounds susceptible to chemoresistance mediated by glutathione and cystine/glutamate transport system xc. J Med Chem. 2007;50:1896–1906. doi: 10.1021/jm060960h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Nomura S, Maebara K, Sato K, Tamba M, Bannai S. Transcriptional control of cystine/glutamate transporter gene by amino acid deprivation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewerenz J, Maher P. Basal levels of eIF2alpha phosphorylation determine cellular antioxidant status by regulating ATF4 and xCT expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1106–1115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807325200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Novoa I, Lu PD, Calfon M, et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell. 2003;11:619–633. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameri K, Harris AL. Activating transcription factor 4. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu F, Bain PJ, LeBlanc-Chaffin R, Chen H, Kilberg MS. ATF4 is a mediator of the nutrient-sensing response pathway that activates the human asparagine synthetase gene. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24120–24127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vattem KM, Wek RC. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11269–11274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400541101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi M, Naczki C, Koritzinsky M, Fels D, Blais J, Hu N, et al. ER stress-regulated translation increases tolerance to extreme hypoxia and promotes tumor growth. Embo J. 2005;24:3470–3481. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi T, Izumi H, Uchiumi T, Nishio K, Arao T, Tanabe M, et al. Clock and ATF4 transcription system regulates drug resistance in human cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2007;26:4749–4760. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Sato H, Kuriyama-Matsumura K, Sato K, Maebara K, Wang H, et al. Electrophile response element-mediated induction of the cystine/glutamate exchange transporter gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44765–44771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih AY, Johnson DA, Wong G, Kraft AD, Jiang L, Erb H, et al. Coordinate regulation of glutathione biosynthesis and release by Nrf2-expressing glia potently protects neurons from oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3394–3406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03394.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassot I, Estrabaud E, Emiliani S, Benkirane M, Benarous R, Margottin-Goguet F. p300 modulates ATF4 stability and transcriptional activity independently of its acetyltransferase domain. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41537–41545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505294200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassot I, Segeral E, Berlioz-Torrent C, Durand H, Groussin L, Hai T, et al. ATF4 degradation relies on a phosphorylation-dependent interaction with the SCF(betaTrCP) ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2192–2202. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.2192-2202.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce M, Bryant KF, Jousse C, Long K, Harding HP, Scheuner D, et al. A selective inhibitor of eIF2alpha dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science. 2005;307:935–939. doi: 10.1126/science.1101902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu PD, Harding HP, Ron D. Translation reinitiation at alternative open reading frames regulates gene expression in an integrated stress response. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:27–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargusch R, Schubert D. Specificity of resistance to oxidative stress. J Neurochem. 2002;81:1394–1400. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoa I, Zeng H, Harding HP, Ron D. Feedback inhibition of the unfolded protein response by GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2alpha. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1011–1022. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange PS, Chavez JC, Pinto JT, Coppola G, Sun CW, Townes TM, et al. ATF4 is an oxidative stress-inducible, prodeath transcription factor in neurons in vitro and in vivo. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1227–1242. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galehdar Z, Swan P, Fuerth B, Callaghan SM, Park DS, Cregan SP. Neuronal apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress is regulated by ATF4-CHOP-mediated induction of the Bcl-2 homology 3-only member PUMA. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16938–16948. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ord D, Meerits K, Ord T. TRB3 protects cells against the growth inhibitory and cytotoxic effect of ATF4. Exp cell res. 2007;313:3556–3567. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielnicki LM, Hughes RG, Chevray PM, Pruitt SC. Mutated Atf4 suppresses c-Ha-ras oncogene transcript levels and cellular transformation in NIH3T3 fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228:586–595. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JD, McMahon M. NRF2 and KEAP1 mutations: permanent activation of an adaptive response in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher P, Lewerenz J, Lozano C, Torres JL. A novel approach to enhancing cellular glutathione levels. J Neurochem. 2008;107:690–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05620.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordey M, Pike CJ. Conventional protein kinase C isoforms mediate neuroprotection induced by phorbol ester and estrogen. J Neurochem. 2006;96:204–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming RC, Dargusch R, Fischer WH, Schubert D. Increase in expression levels and resistance to sulfhydryl oxidation of peroxiredoxin isoforms in amyloid beta-resistant nerve cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30523–30534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher P. Proteasome inhibitors prevent oxidative stress-induced nerve cell death by a novel mechanism. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:1994–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.