Abstract

Notch signaling in the cardiovascular system is important during embryonic development, vascular repair of injury, and vascular pathology in humans. The vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) expresses multiple Notch receptors throughout its life cycle, and responds to Notch ligands as a regulatory mechanism of differentiation, recruitment to growing vessels, and maturation. The goal of this review is to provide an overview of the current understanding of the molecular basis for Notch regulation of VSMC phenotype. Further, we will explore Notch interaction with other signaling pathways important in VSMC.

Keywords: Notch, vascular smooth muscle, signaling

Introduction

Notch receptors are type-1 transmembrane proteins that regulate cell differentiation during embryogenesis and tissue injury and repair. Notch receptors are activated through tightly controlled juxtacrine interactions with transmembrane proteins of the Jagged (Jag) or Delta-like (Dll) families of ligands (Figure 1). In mammals, expression of the four Notch receptors (Notch1, Notch2, Notch3, and Notch4) and five ligands (Jag-1, Jag-2, Dll-1, Dll-3, and Dll-4) varies significantly among cell types and changes in response to environmental cues within the surrounding tissue (Andersson et al., 2011; de la Pompa and Epstein, 2012). After translation, Notch precursor proteins traverse the Golgi apparatus where they undergo S1 cleavage by a furin-like convertase in the trans-Golgi network (Lake et al., 2009). This maturation step creates a heterodimer consisting of a large extracellular domain (ECD) comprised mainly of repeating EGF-like repeats linked through non-covalent bonds to a smaller domain consisting of the transmembrane and intracellular portion of the receptor, aptly referred to as the Notch extracellular truncation (NEXT; Mumm et al., 2000). The Notch proteins may be subjected to N-linked glycosylation by fringe enzymes (Lunatic, manic, radical) before being presented as a mature receptor on the cell surface. The interaction of Notch receptors with Jag or Dll ligands results in a conformational change in the ECD of the receptor that exposes a cleavage site for the metalloprotease ADAM17 to initiate S2 cleavage; thereby liberating the ECD from the cell surface. Endocytosis of the ligand/ECD complex occurs in the ligand-presenting cell and the mechanism and importance of this event is currently the subject of much debate.

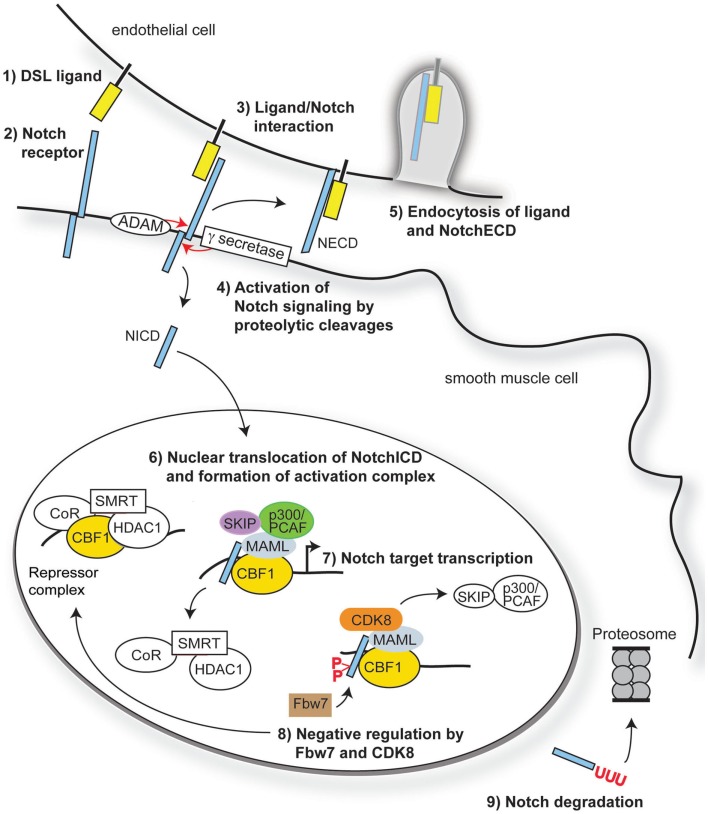

Figure 1.

Overview of Notch signaling. Notch signaling is activated when a transmembrane ligand of the Delta–Serrate Lag (DSL) family (1) interacts with the EGF-like repeats of the extracellular domain of Notch receptors (2) on an adjacent cell. Ligand/receptor interactions induce a conformational change in the receptor, exposing critical sites for ADAM17 (S2) and γ-secretase (S3) cleavage of the Notch receptor (3). Cleavage of Notch receptors results in liberation and translocation of the intracellular domain (ICD) to the nucleus (4) while the extracellular domain (ECD) is endocytosed by the ligand-bearing cell (5). In the nucleus, the RAM domain of NotchICD binds to transcriptional repressor CBF1, causing displacement of associated co-repressors and recruitment of Mastermind-like (MAML) and other co-activators (6) to initiate transcription of Notch/CBF1 regulated downstream genes (7). Turning off Notch signaling begins with recruitment of CDK8 by MAML to the active complex, thereby causing phosphorylation of NotchICD within its PEST domain. Phosphorylation causes recruitment of E3 ubiquitin ligase Fbw7 for ubiquitination (8) and proteosome degradation of (9) of NotchICD, thereby destabilizing the activator complex and allowing CBF1 to re-associate with co-repressors.

Full activation of Notch receptors is achieved upon S3 cleavage of NEXT by presenilin, the proteolytic subunit of the γ-secretase complex (De Strooper et al., 1999), to liberate the intracellular domain (ICD). Once released from the plasma membrane, the ICD translocates into the nucleus where it binds to the transcriptional repressor RBP-J (CBF1) the mammalian homolog of suppressor of hairless (SuH) in Drosophila (Tanigaki and Honjo, 2010). The transcriptional repressor activity of CBF1 is alleviated through the formation of a multi-protein complex involving NotchICD, CBF1, and proteins of the Mastermind-like family (MAML; Nam et al., 2007; Kovall, 2008). Formation of the ternary complex causes displacement of the CBF1 associated co-repressor SMRT and histone deacetylases (HDAC; Kao et al., 1998), while simultaneously binding to Ski-interacting protein SKIP (Zhou et al., 2000), histone acetyltransferases p300 and PCAF (Wallberg et al., 2002), and elongation factor CyclinT1:CDK9 (Chopra et al., 2009) to assist with transcriptional initiation. The NotchICD-containing activator complex goes on to promote transcription of downstream gene targets including Hairy enhancer-of-split (HES) and Hairy/enhancer-of-split related with YRPW motif (HEY, also called HRT, HERP, HESR; Iso et al., 2003) through CBF1 binding to CGTGGGAA motifs in the promoter regions of these genes (Tun et al., 1994). Turning off Notch signaling begins with degradation of the active transcriptional complex through recruitment of CyclinC:CDK8 by MAML. CyclinC:CDK8 recruitment to the complex promotes hyperphosphorylation of NotchICD within its PEST domain and targets the protein for Fbw7/Sel10 E3 ubiquitin ligase-dependent degradation (Fryer et al., 2004). Other kinases that promote NotchICD turnover through phosphorylation include the Wnt pathway associated enzyme glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β; Espinosa et al., 2003) and the ubiquitously expressed casein kinase 2 (Ranganathan et al., 2011). Figure 1 provides an overview of the canonical Notch signaling pathway.

Notch Signaling in Cardiovascular Development

During cardiovascular development, perturbations in the expression of Notch pathway components result in profound vascular malformations, and this has been extensively addressed using mouse genetic models (Table 1). Targeted deletion of Notch1, Notch2, Notch3, Jag-1, Dll-1, and Dll-4 all lead to a variety of vascular defects. Both Notch2 and Notch3 mutations lead to defects in vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) development, showing their requirement for expansion and maturation of the mural cell population. Although endothelial cell Notch ligands are important activators of VSMC development (Xue et al., 1999; High et al., 2008), VSMC also signal homotypically through Notch. Deletion of Jag-1 in smooth muscle cells using SM22α regulatory elements leads to loss of VSMC differentiation and patent ductus arteriosus (Figure 2). In these mice, the ductus arteriosus and descending aorta had fewer mural cells that could be molecularly identified as VSMC, suggesting a defect in propagation of the Jag-1/Notch signal throughout the medial vascular wall (Feng et al., 2010).

Table 1.

Notch cardiovascular phenotypes in mouse models.

| Gene | Normal cardiovascular expression | Genetic mouse model and cardiovascular phenotype | Survival | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notch1 | Arterial endothelium Vascular smooth muscle |

Global null: collapsed aorta and cardinal vein, reduced sprouting angiogenesis, abnormal yolk sac vasculature, and vascular remodeling | Lethal at E9.0–9.5 | Krebs et al. (2000, 2010) |

| Endocardium Atrioventricular canal |

EC gain of function: enlarged heart and reduced vessel diameter, abnormal remodeling of yolk sac vasculature, hemorrhaging | Lethal at E9.5 | ||

| Notch2 | Cardiac neural crest-derived VSMC | Global null: reduced pulmonary artery and aortic VSMC proliferation, defects in eye vasculature | Lethal at E11.5 | Krebs et al. (2000), Varadkar et al. (2008) |

| Endothelium | ||||

| Notch3 | Vascular smooth muscle | VSMC null: decreased VSMC differentiation, dilated aorta, and disorganized elastic lamina | Viable | Ruchoux et al. (2003), Domenga et al. (2004) |

| Pericytes | R169C mutation: Notch3ECD domain aggregates and GOM deposits in brain vessels, reduced caliber of brain arteries, and cerebral blood flow | |||

| Notch4 | Endothelium Endocardium Atrioventricular canal |

Global null: mainly undetectable vascular malformations, with enhanced vascular abnormalities when to crossed with Notch1 null mice compared to Notch1 null alone | Viable | Krebs et al. (2000) |

| Jag-1 | Endothelium VSMC Heart |

Global null: reduced VSMC maturation, abnormal yolk sac and embryonic vascular remodeling, cranial hemorrhaging | Lethal at E11.5–12 | Xue et al. (1999) |

| Dll-1 | Arterial endothelium late in development VSMC, adult EC |

Global null: hemorrhaging, increased venous EC markers, reduced arterial EC markers, impaired recovery of blood flow after hindlimb ischemia | Lethal at E12 | Hrabe de Angelis et al. (1997), Limbourg et al. (2007) |

| Dll-4 | Endothelium | Global null: defective arterial branching, aortic atresia, arterial regression, large artery stenosis, abnormal yolk sac vasculature | Lethal at E9.5 | Gale et al. (2004), Krebs et al. (2004), Trindade et al. (2008) |

| Endocardium | EC gain of function: enlarged dorsal aorta, reduced vascular sprouting, proliferation, migration, and sensitivity to VEGF | Lethal at E10 |

Gene targeting mutations in the Jag-2 and Dll-3 genes lead to developmental abnormalities, but no cardiovascular phenotypes have been reported. EC, endothelial cell; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

Figure 2.

Neonatal mice with smooth muscle-specific Jag-1 gene deletion exhibit patent ductus arteriosus. A conditional, Cre-responsive Jag-1 allele was crossed to the SM22α-Cre strain (TagIn-Cre) as described (Feng et al., 2010). To visualize the outflow tract and ductus arteriosus, the left ventricles of control littermate (A) and Jag-1 smooth muscle deletion (B) neonatal mice were injected with silicone rubber injection compound (tinted yellow). While the ductus arteriosus closed normally in the control mouse, it remained patent (open) in the Jag-1 smooth muscle deletion mouse. Associated defects in VSMC differentiation were also observed. DA, ductus arteriosus; LC, left carotid artery; LSC, left subclavian artery; RC, right carotid artery; RSC, right subclavian artery.

Several signaling pathways and transcription factors are important in dictating the phenotypic state (i.e., proliferative versus contractile) of VSMC, some of which include: serum response factor (SRF)/myocardin (Manabe and Owens, 2001; Camoretti-Mercado et al., 2003; Miano et al., 2007), PDGF (Marmur et al., 1992; Thommes et al., 1996), TGF-β (Ikedo et al., 2003; Tang et al., 2010), GATA-6 (Wada et al., 2000), IGF-I (Thommes et al., 1996), FGF-2 (Segev et al., 2002), endothelin-1 (Hahn et al., 1992), and nitric oxide (Grange et al., 2001). In the last decade or so, a great deal of evidence has emerged supporting a pivotal role for Notch receptors/ligands in mediating endothelial cell to smooth muscle cell communication, and influencing the phenotypic state of VSMC (Campos et al., 2002; Doi et al., 2006; Anderson and Gibbons, 2007; High et al., 2008; Tang et al., 2008; Boucher et al., 2011). Studies investigating the function of Notch signaling in VSMC have yielded conflicting results, describing both anti-differentiation (Morrow et al., 2005; Proweller et al., 2005) and pro-differentiation functions for Notch (Domenga et al., 2004; Tang et al., 2008; Boucher et al., 2011). These discrepancies have been speculated to be a result of the highly context-dependent nature and tight spatio-temporal regulation of Notch pathway components during development, in the adult vasculature, and in response to physiological changes in vivo. Mutations in the Notch pathway leading to human pathology have recently been extensively reviewed (Fouillade et al., 2012).

Phenotypic Flexibility of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells

Many of the somatic cells that comprise an organism exist in a terminally differentiated state, thereby maintaining steady state expression of proteins that enable their mature function. The primary function of mature VSMC is to maintain vascular tone and regulate blood pressure through constriction or dilation of the vessel (Rensen et al., 2007). Quiescent VSMC are fully differentiated, non-proliferative cells that express high levels of a subset of genes required for their contractile functions. The central component of the contractile apparatus in VSMC is comprised of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SM-MHC) isoforms and α-smooth muscle actin (SM-actin; Owens et al., 2004). The contractile filament smoothelin B is exclusively expressed in mature VSMC and represents a late stage differentiation marker (Christen et al., 1999). Smoothelin B is often rapidly down regulated in proliferating VSMC cultures. Other well-characterized markers of mature VSMC include actin cross-linking protein transgelin (SM22α), and the calcium binding protein and inhibitor of SM-MHC intrinsic ATPase activity, calponin. Leiomodin-1, a gene target of SRF/myocardin dependent transcription, was recently described as a novel marker of contractile VSMC (Nanda and Miano, 2012). Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and contractile machinery of VSMC by SRF has previously been reviewed (Miano et al., 2007). Events such as disruption of the endothelial monolayer, exposure to growth factors (PDGF-BB, FGF), aberrant interactions with the extracellular matrix, injury/wound healing, and vascular remodeling can initiate cascades in VSMC leading to a rapid down regulation of contractile proteins and acquisition of a highly proliferative and migratory phenotype. While markers of the proliferative VSMC phenotype are less well defined than contractile markers, the expression of tropomyosin 4 and myosin heavy chain embryonic are observed during the proliferative state of VSMC (Sung et al., 2005). Although Notch is appreciated as one regulator of VSMC phenotype, there are conflicting data describing its role in smooth muscle differentiation. The following sections will discuss the current known mechanisms by which Notch signaling affects VSMC phenotypic modulation.

Molecular Mechanisms of Notch Signaling in VSMC

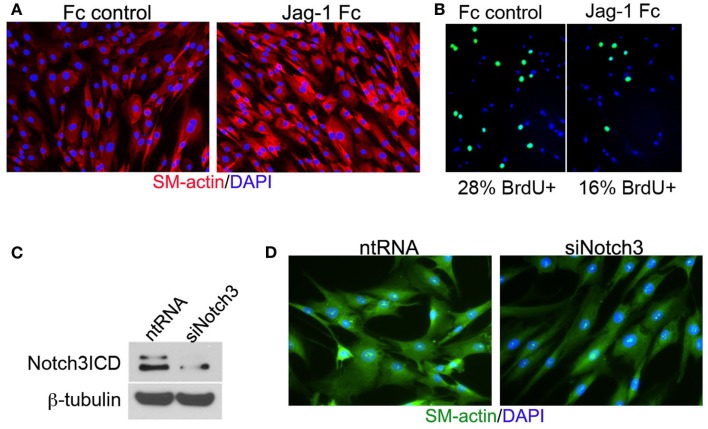

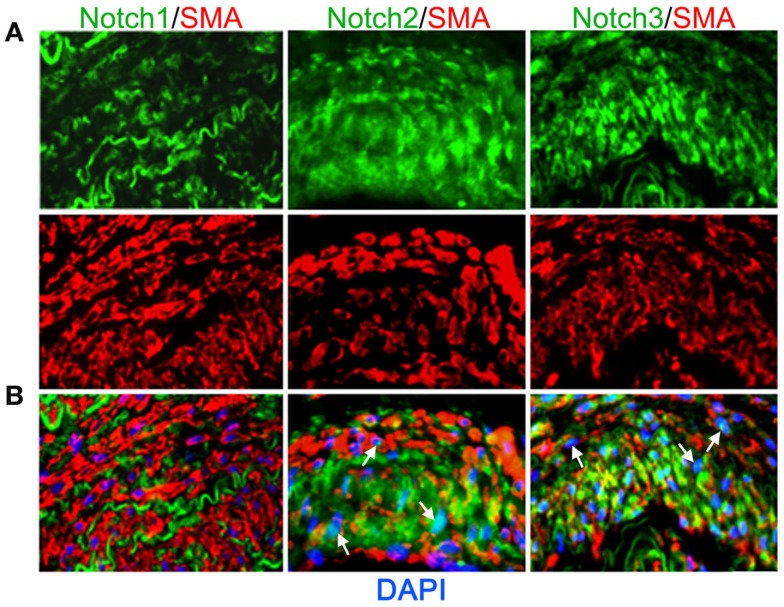

Vascular smooth muscle cell express Notch1, Notch2, and Notch3 receptors while endothelial cells express Jag-1, Dll-4, and to some extent in remodeling vasculature, Dll-1 (Table 1). Changes in the levels of Notch receptors in VSMC and ligand expression patterns by adjacent endothelial cells provide a means by which vascular cells can communicate and respond appropriately to physiological stimuli. In addition to Notch receptor activation by endothelial-expressed ligands, VSMC expressed Jag-1 activates Notch1 on endothelial cells to promote proliferation (Yang and Proweller, 2011), and thereby represents the importance of heterotypic cell signaling between vascular cells via Notch. A variety of mechanisms have been proposed to explain the discrepant phenotypes in VSMC upon activation of Notch signaling. For example, it is well documented that endothelial expression of Jag-1 is required for activation of Notch3 on VSMC and maintenance of VSMC maturation and contraction (High et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009), while others have shown a variety of mechanisms by which active Notch signaling inhibits VSMC differentiation and the contractile phenotype (Havrda et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009a). Work from our laboratory supports the former finding in that activation of Notch receptors in human primary VSMC using immobilized Jag-1 promotes upregulation of contractile proteins (Boucher et al., 2011; Figure 3A). Jag-1-mediated activation of VSMC markers corresponded to a robust inhibition of proliferation (Figure 3B), supporting a pro-differentiation effect for Jag-1/Notch signaling in human VSMC. In addition, suppression of endogenous Notch3 receptors using siRNA significantly reduces endogenous levels of SM-actin (Figures 3C,D), showing that basal Notch signaling promotes the contractile phenotype. Although the precise mechanism(s) of Jag-1/Notch-induced maturation is still poorly understood, a number of studies have systematically investigated the molecular pathways leading to the pro-differentiation and pro-proliferative effects of Notch signaling in VSMC. Further studies are required to additionally determine whether Jag-1 signaling through other Notch receptors regulate the differentiated phenotype. We have observed strong expression of both Notch2 and Notch3 receptors in the tunica media of large arteries derived from normal human lung biopsies, while Notch1 was undetectable (Figure 4). Thus, further defining Notch receptor expression and function during normal and pathological settings will enhance our understanding of the signals required for maintaining vascular homeostasis.

Figure 3.

Jag-1/Notch3 signaling modulates VSMC plasticity toward maturation and contraction. Human aortic VSMC were plated on immobilized recombinant rat Jag-1 Fc or Fc control for 48 h to activate Notch receptors. Immunostaining reveals a significant increase in the expression of the contractile protein SM-actin in response to active Notch signaling (A). BrdU incorporation into the nuclei of Jag-1 Fc stimulated cells was significantly reduced in comparison to Fc control plated cells (B). (Green = BrdU positive nuclei, Blue = DAPI for total cell count, n = 15, p < 0.01). Reduction of Notch3 levels via siRNA-mediated knockdown (C) reveals a distinct reduction in endogenous SM-actin levels after 72 h as compared to VSMC receiving a non-targeting control probe (D).

Figure 4.

Expression of Notch receptors in human arteries. Human lung biopsies were used for immunohistochemical analysis of Notch receptors expressed by medial VSMC cells. (A) Representative images of Notch receptors (green) and SM-actin positive cells (red) for Notch1 (left), Notch2 (middle), and Notch3 (right). (B) Images were overlaid with DAPI staining to show distribution and localization of Notch receptors within SM-actin positive cells. The elastic laminae display some autofluorescence.

Contractile genes in VSMC may be directly activated by transcription factors promoting differentiation. The best characterized is the SRF/myocardin complex, which is capable of potent transcriptional activation of VSMC marker genes through binding to highly conserved [CC(A/T)6GG] sequences, termed CArG boxes, in their promoters (Treisman and Ammerer, 1992; McDonald et al., 2006; Miano et al., 2007). Likewise, Notch signaling leads to the regulation of hundreds of genes, some of which control VSMC phenotype (Borggrefe and Liefke, 2012). Notch-responsive CBF1 cis-elements are present in the promoters of the SM-MHC (Doi et al., 2006) and SM-actin genes (Noseda et al., 2006), and both are direct transcriptional targets of Notch. It remains unclear whether CBF1/Notch requires higher order complex assembly with SRF/myocardin at the promoter to activate transcription or whether it can act independently. Our studies suggest that Notch may be dependent on SRF activity to upregulate some target genes (SM-actin, SM-MHC), whereas it can independently activate other targets (miR-143/145). In differentiation models of 10T1/2 mesenchymal cells toward the VSMC lineage, Jag-1/Notch signaling up regulates de novo SM-MHC protein synthesis in a CBF1-dependent manner (Doi et al., 2006), while chemical inhibition of the γ-secretase complex (prevention of S3 cleavage and NICD translocation to the nucleus) abrogates the Jag-1/Notch specific induction of SM-MHC. Importantly, a requirement of SRF/myocardin at the promoter was necessary for Notch-induced synergistic activation. We observed a similar finding in that over expression of a constitutively active Notch1ICD robustly induces SM-actin expression in VSMC; however knockdown of SRF was sufficient to block this induction (Boucher et al., 2011). It seems likely that communication between SRF/myocardin and CBF1/Notch at contractile gene promoters may act in parallel, or synergistically, to activate expression of VSMC markers.

Aside from direct transcriptional activation of VSMC specific gene promoters by Notch signaling, recent evidence from our laboratory shows transcriptional regulation of specific microRNAs (miR) that are involved in acquisition of the contractile phenotype in VSMC (Boucher et al., 2011). miR are short (∼22 nt) RNA molecules that are involved post-transcriptional regulation of protein expression through mRNA destabilization and/or translational blockade (Baek et al., 2008). One intergenic miR cluster (controlled by its own promoter) important in modulation of VSMC plasticity encodes miR-143 and miR-145 (miR-143/145; Xin et al., 2009). The miR-143/145 cluster plays an important role in modulation of VSMC phenotype through translational repression of proliferative machinery (KLF4/5, Elk1; Boettger et al., 2009; Elia et al., 2009; Xin et al., 2009). Although miR-143/145 is a known transcriptional target of SRF/myocardin; Xin et al., 2009), we also found that the miR-143/145 gene is a direct transcriptional target of Notch signaling. Transcriptional activation of miR-143/145 by Notch is CBF1-dependent, and independent of SRF/myocardin in human VSMC (Boucher et al., 2011). Thus, Jag-1/Notch signaling can activate miR-143/145 even with a mutant CArG box in the promoter, but is reliant on binding of NICD/CBF1 complexes to intact CBF1 consensus binding sites for its activation. Induction of miR-143/145 by Jag-1/Notch signaling in human VSMC is required for Notch-induced acquisition of the contractile phenotype. These findings demonstrate that in addition to transcriptional regulation of contractile gene promoters themselves, Notch signaling controls expression of genes indirectly associated with VSMC maturation.

Notch Promotes Differentiation in Cooperation with Other Pathways

In addition to the shared functions of Notch and the SRF/myocardin pathways, Notch cooperates with other signaling mediators of VSMC differentiation. A recent study investigating Notch signaling in murine epicardial development established a connection with transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling (Grieskamp et al., 2011). In this report, using aTbx18cre driver to specifically delete CBF1 in the pro-epicardium, progenitor cells failed to differentiate into coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Additionally, conditional activation of Notch1ICD forced the premature differentiation of epicardium cells into the smooth muscle lineage. One potential mechanism they observed was a lack of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) expression in CBF1-deficient cells, and the authors proposed that TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3 ligands induced by active Notch signaling led to co-activation of contractile genes to induce smooth muscle differentiation from epicardium-derived cells. Our lab observed a similar interaction in studies of co-activation of the Notch and the TGF-β pathways in human VSMC (Tang et al., 2010). We found that CBF1 interacts with phosphorylated SMAD2/3, and this corresponds to increased phosphorylated SMAD2/3 activation of the genes encoding SM-actin, calponin1, and SM22α. Other studies have also provided evidence supporting crosstalk between Notch and TGF-β through their downstream effectors CBF1 and SMAD2/3, respectively (Blokzijl et al., 2003; Zavadil et al., 2004).

Notch Signaling is Upstream of Regulators of VSMC Contraction and Tone

Juxtaglomerular cells (also referred to as granular cells) represent a highly specialized smooth muscle-like cell type that surrounds the afferent arteriole leading to the kidney glomeruli. The primary function of these cells is to synthesize and secrete the enzyme renin into the blood stream (Schweda and Kurtz, 2012). In the circulation, renin converts the serum α2 globulin protein angiotensinogen into angiotensin I. Angiotensin I is then further processed in the lung by angiotensin converting enzyme to produce angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor that can play a role in the onset of hypertension (Crowley et al., 2006; Gwathmey et al., 2012). Interestingly, the human, rat, and mouse promoter/enhancer region of the Renin gene has a conserved binding motif for CBF1. Signaling through Notch1ICD and CBF1 are sufficient to activate a promoter reporter construct in Cos-7 cells in which multiple copies of the CBF1 motif in the rat Renin promoter have been fused together (Pan and Gross, 2005). In addition, electrophoretic mobility shift assays revealed the presence of CBF1 protein bound to the Renin promoter in As4.1 cells (Pan and Gross, 2005). Further investigation of the regulation of RENIN expression by Notch signaling could provide a better understanding of the factors contributing to excessive angiotensin II production and the development of hypertension in humans.

Notch signaling also appears to play a direct role in regulating renal vascular tone. A recent study tested effects of the vasoconstrictors norepinephrine or angiotensin II on renal vascular tone and resistance on a wild type or Notch3 null background (Boulos et al., 2011). Unlike the predicted increase in renal vascular resistance in wild type mice, the renal vasculature in Notch3 null mice showed negligible changes in resistance. Isolation of the afferent arteriole from Notch3 null mice revealed structural and functional differences compared to wild type arterioles, including reduced vessel wall thickness, and an aberrant contractile response in response to angiotensin II. Notch3 null mice also were more resistant to increased blood pressure after angiotensin II infusion, although they were susceptible to heart failure. These observations emphasize the importance of Notch signaling at a systemic level in influencing and mediating the body’s response to endocrine pathways.

Positive Feedback of the Notch Pathway

A positive feedback loop that potentiates Notch3 expression and VSMC differentiation has recently been identified (Liu et al., 2009). Endothelial-expressed Jag-1 was shown to activate Notch3 expression in mural cells and ultimately lead to increased expression of Notch3 and Jag-1 through a positive feedback loop as well as induction of smooth muscle markers. Physical separation of human dermal fibroblasts from the endothelium, blockade of the S3 cleavage using γ-secretase inhibitor or inhibition of ternary complex formation using a dominant negative mastermind were all sufficient at inhibiting Notch3 positive regulation. The authors were the first to identify a mechanism by which Notch3 signaling potentiates its own expression and the expression of its ligand. Furthermore, a recent report has described a CBF1 cis-element within the second intron of the Jag-1 locus that is responsive to exogenous Jag-1 stimulation in primary VSMC isolated from murine aortic arches (Manderfield et al., 2012). The authors report a requirement for Notch induction of Jag-1 in cardiac neural crest cell differentiation to VSMC in the developing aortic arches. These findings shed light on the importance of Notch signaling in not only potentiating VSMC development from mesenchymal progenitor cells, but also the requirement of Notch-induced positive feedback loops for proper vessel maturation and expansion of the VSMC layer in the aorta through lateral communication.

Negative Feedback Pathways of VSMC Differentiation

The Notch pathway has a variety of molecular regulators that repress its function, leading to the tight spatial regulation of expression of Notch target genes (Cave, 2011). Repression of differentiation by HEY represents a pivotal way in which Notch signaling can inhibit the contractile phenotype. An elaborate study by Proweller et al. (2005) showed the induction of Notch signaling by Jag-1 or over expression of a constitutively active Notch1ICD in C3H10T1/2 cells robustly inhibited myocardin dependent expression of contractile gene expression through HEY2. HEY2 mediated repression required the basic DNA binding domain and C-terminal sequence. These findings may help explain why HEY2 null mice display decreased neointimal formation in response to vascular injury (Sakata et al., 2004). Shortly after, it was shown that HEY2 expression antagonizes SRF/myocardin binding to the CArG box of contractile gene promoters both in vitro and in vivo through a physical interaction with SRF (Doi et al., 2005). Our laboratory showed that HEY expression antagonizes the activity of NotchICD to induce SM-actin gene expression (Tang et al., 2008). Using chromatin immunoprecipitation, we found that HEY2 disrupted NotchICD/CBF1 increase in SM-actin protein by interfering with NotchICD/CBF1 binding to the promoter region of the gene. This study provides a novel mechanism by which Notch is capable of initially promoting a contractile phenotype in VSMC before the onset of a negative feedback loop to antagonize the effect. Presumably, such feedback mechanisms may help explain the context-dependent nature of Notch signaling and the endogenous means by which Notch receptor activation moderates its own downstream effects. Thus, one function of HEY may be to antagonize Notch signaling as its levels accumulate in the cell, acting to both propagate the Notch signal downstream, as well as prevent further sustained signaling upstream from the receptor. We also found that HEY expression was equally effective in suppressing TGFβ1 induction of VSMC contractile genes. Therefore, HEY factors appear to have a conserved function of inhibiting VSMC differentiation via multiple pathways of SRF, Notch, and TGFβ activation.

Notch Receptors and Ligands Have Non-Redundant Functions

Although unique signaling pathways downstream of each Notch ligand and receptor are not well defined, it is clear that each has some non-overlapping functions. This is highlighted by the diverse phenotypes obtained from targeted mutations or transgenic activation of these genes (Table 1). In addition, direct comparison of ligand or receptor activity has suggested unique downstream functions. For example, in osteoclastogenesis, Jag-1 and Dll-1 appear to be either inhibitory or stimulatory signals, respectively (Sekine et al., 2012). These opposing functions could partially be attributed to a model where Jag-1 interacts with Notch1 and Dll-1 interacts with Notch2 in the monocyte lineage to exert opposite cues for osteoclastogenesis. Differences in ligand and receptor activity have also been reported in regulation of the hematopoietic lineage (Jaleco et al., 2001; de La Coste and Freitas, 2006; Van de Walle et al., 2011). Recent data suggest that this selectivity regulates Notch functions in the cardiovascular system. During angiogenesis, Jag-1 and Dll-4 can have opposing activities with Jagged1/Notch cues acting as pro-angiogenic signals, while activation of the Dll/Notch pathway has anti-angiogenic consequences (Dufraine et al., 2008). It will be of interest to determine how ligand-specificity and selective Notch activation may regulate the differentiated phenotype of VSMC. This is especially crucial in situations of vascular disease and remodeling, where changes in Notch ligand and receptor expression occur (Lindner et al., 2001).

Additionally, NotchICD can selectively associate with CBF1 at separate and distinct cis-elements within the promoters of Notch target genes. PDGFR has been identified as a downstream gene target of Notch signaling in VSMC followed by over expression of Notch1ICD or Notch3ICD (Jin et al., 2008). In VSMC, platelet derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB signaling through the PDGF-BB receptor-β (PDGFR) on VSMC represents a potent migratory and proliferative signaling axis via the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade (Inui et al., 1994; Graf et al., 1997). Activation of Notch in VSMC results in increased phosphorylation and activation of PDGFR and AKT. Global Notch3 knockout mice display a marked reduction in the arterial expression of PDGFR. An intriguing observation in this report indicated that Notch1 and Notch3 regulate the PDGFR promoter through distinct CBF1 binding sites (Jin et al., 2008). Mutational analysis of CBF1 consensus sites within a 1.5-kB PDGFR promoter element fused to the luciferase gene, researchers found that Notch1ICD/CBF1 binds to the consensus motif at −256 to −249 upstream of the transcriptional start site. In contrast, Notch3ICD/CBF1 regulates the promoter through a consensus motif not located within the PDGFR 1.5 kB promoter region. These findings present the possibility of distinct regulatory functions downstream of Notch receptors, and stress the importance of changes to receptor expression during diseased and normal vascular states. Determining the exact means by which receptor specificity is obtained will present a great challenge moving forward. Many potential mechanisms are already being considered, including the aforementioned changes in the expression pattern of Notch ligands and receptors, the specificity of ligands to the four Notch receptors, and formation of distinct NotchICD-containing transcriptional complexes at unique cis-elements. Additional levels of regulation are expected to be the turnover of NotchICD proteins, the recruitment of different histone acetyltransferases or deacetylases to the transcriptional complex, regulation of non-canonical Notch signaling, and the post-translational modifications of Notch (i.e., glycosylation).

Notch Signaling Mediates VSMC Proliferation and Neointimal Lesion Formation

Support for the involvement of Notch in mediating VSMC proliferation and neointimal formation comes from a study in which carotid artery ligations were used to induce the formation of a neointima in mice harboring one of the following genotypes: a general heterozygous deletion of Notch1 (Notch1+/−), a VSMC specific heterozygous deletion of Notch1 (VSMC–Notch1+/−), or a homozygous general deletion of Notch3 (Notch3−/−; Li et al., 2009a). In this report, researchers show negligible differences in neointimal formation between wild type and Notch3−/−, while Notch1+/− and VSMC–Notch1+/− resulted in post-carotid ligation decrease in neointimal lesion formation by 70%. The pro-migratory and pro-proliferative effects of Notch1ICD over expression could be attenuated in HEY2 deficient VSMC in vitro. Interestingly, while Notch2 and Notch3 receptor expression remained constant in both medial and neointimal VSMC, a transient expression of Notch1 was observed in neointimal VSMC (Li et al., 2009a). Another recent report shows that expression of soluble Jag-1, which acts as an inhibitor of Notch signaling, is sufficient to reduce VSMC proliferation and migration after balloon injury of rat carotid arteries, which correlates to reduced neointimal lesion formation. This effect was suggested to be via attenuation of the Notch/HEY1 pathway (Caolo et al., 2011).

It is now known that certain chemicals can influence Notch1 expression levels and VSMC proliferation and migration. For example, moderate alcohol intake has cardiovascular protective effects mediated through Notch signaling in VSMC (Morrow et al., 2010). In this report, human coronary artery VSMC were treated with 25 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH) daily for 7 days, which led to a significant decrease in cell proliferation. EtOH treatment caused a decrease in Notch1 mRNA and ICD protein and HEY1/2 expression while having negligible effects on Notch3. The inhibition on VSMC proliferation by EtOH treatment could be rescued upon over expression of Notch1ICD or HEY1. Lastly, feeding EtOH to mice subjected to a partial ligation of the carotid artery prevented the injury-induced induction of Notch1 and reduced medial, intimal, and adventitial volume significantly from injured mice not supplemented with alcohol. This study is unique in that it provides a sound mechanistic link to Notch signaling in mediating the cardioprotective effects associated with light to moderate daily alcohol consumption (O’Keefe et al., 2007). The same group also found that moderate alcohol consumption stimulated endothelial cell proliferation and migration (pro-angiogenic) in vitro through activation of canonical Notch signaling, leading to increased expression of angiopoietin and its receptor Tie2 (Morrow et al., 2008). Such studies emphasize the crucial role Notch signaling plays in vessel homeostasis and the environmental factors that contribute to its function in the cardiovascular system.

Finally, a requirement for Notch2 in promoting the expansion of cardiac neural crest-derived VSMC around the developing outflow tracks has been reported (Varadkar et al., 2008). While the mechanism supporting the observed phenotype is still unclear, it emphasizes the spatio-temporal nature of Notch signaling during VSMC development and its requirement for proper vessel maturation. Collectively, it appears that transient changes in Notch receptor expression are sufficient to promote a pathological phenotype characterized by increased migration and proliferation of VSMC in the neointima of injured arteries. Although there may be some overlap of Notch receptor signaling, emerging evidence provides insight into the possibility of receptor-specific pathways and selective activation of downstream targets during normal and pathological states. Transient expression of Notch1 may act as a primary mediator of VSMC proliferation/migration during pathological states. Additional questions remain including the causes of changes in Notch receptor expression during disease states, whether Notch receptors exert differential functions in a developing versus mature vessel, and the downstream factors that specify the VSMC response to a specific Notch receptor.

Notch Signaling Affects VSMC Interaction with the Basement Membrane and Matrix Remodeling Enzymes

Besides the contractile proteins themselves, the composition of extracellular matrix (ECM) components and engagement with distinct adhesion receptors on the cell surface play a distinct role not only in regulating blood vessel development and the normal and tumor angiogenic response (Silva et al., 2008; Astrof and Hynes, 2009), but also in regulating the contractility of VSMC (Ichii et al., 2001). VSMC secrete elastin, chondroitin sulfate, and collagen types I, III, and V (Underwood et al., 1998). The makeup of the ECM, as well as its degradation and synthesis by endothelial cells and VSMC is essential for proper development and remodeling of the vasculature. Perturbations in the rate of ECM turnover, synthesis and secretion can lead to vascular pathology. For example, disruption of vessel homeostasis can cause excessive ECM deposition and generally correlates with a reduction in contractile proteins and increased VSMC proliferation and migration. A recent investigation studied Notch regulation of VSMC adhesion to the hemostasis-associated protein von Willebrand factor (Scheppke et al., 2012). Mouse retinal vasculature models were used to show that endothelial cell derived Jag-1 is required for proper recruitment of VSMC to the developing vessel, and downstream induction of αVβ3 in VSMC enhanced adhesion to the von Willebrand factor in the endothelial cell basement membrane, leading to proper vessel maturation. Thus, Jag-1/Notch signaling can increase VSMC maturation by regulating their adhesion properties during vessel development and maturation. This finding builds upon previous studies indicating a role for endothelial cell secreted soluble Jag-1, which lacks a transmembrane domain and acts as a dominant negative inhibitor of Notch signaling, in robustly decreasing NIH3T3 cell adhesion in migration (Lindner et al., 2001).

Degradation of the ECM via matrix metalloprotease (MMP) activity is a critical step leading to VSMC migration, proliferation, and neointima formation in injured arteries (Newby, 2006). Thus, factors that regulate the expression and activation of MMPs likely contribute to VSMC phenotype changes. Notch signaling has been identified as a key regulator of MMPs in other systems including regulation of MMP-9 in endothelial cells and their response to VEGF (Funahashi et al., 2011), upregulation of MMP-13 in chondrocytes (Blaise et al., 2009), and upregulation of MMP-9 in pancreatic cancer cells (Wang et al., 2006). It is not surprising that Notch signaling can affect VSMC proliferation and migration through the regulation of MMPs. It has also been reported that Notch can suppress MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity (Delbosc et al., 2008), while the loss of the downstream Notch effector HEY2 in VSMC alleviates repression of the MMP-10 promoter (Wu et al., 2011). Interestingly, in other cell types, ectopic expression of membrane type-1 MMPs induces the cleavage of Dll-1 and reduces Notch signaling (Jin et al., 2011). Thus, MMP activity may be responsive to Notch signals and also serve as a potential negative feedback loop to suppress Notch signaling.

Notch Signaling is Involved in Vascular Pathology

Atherogenesis is a pathological process in which damage to the endothelium initiates changes in vessel wall homeostasis that lead to monocyte extravasation and secretion of inflammatory cytokines capable of promoting VSMC proliferation and migration. The high rate of synthesis of ECM components by proliferating VSMC enables formation of a necrotic core and protective fibrous cap within the intima, resulting in propagation of the atherosclerotic lesion. Notch signaling has been shown to modulate inflammatory pathways via repression of NF-κB (Oswald et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2001), and Notch regulation of inflammation in atherogenesis has been addressed (Clement et al., 2007). Notch activation by Delta-like-1 Fc chimeric proteins was sufficient to down regulate the secretion of phospholipase A2 and prostaglandin E2 in response to Interleukin (IL)-1β, and thus had an anti-inflammatory effect. In addition, IL-1β treatment, via NF-κB activation, down regulates Notch3, Jag-1, HEY1, HEY2, and HES1 mRNA, and prevented NF-κB activation. Interestingly, there was an observed increase in Notch1 mRNA. These results provide evidence that Notch and inflammatory pathways interact during disease, and describe novel anti-inflammatory and pro-quiescence functions for Notch in VSMC.

Vascular calcification is the abnormal transformation of VSMC leading to mineral deposition within the vascular wall (Vattikuti and Towler, 2004). This condition may contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, hypercholesterolemia, end stage renal disease, and diabetes. Unlike the apparent protective effects during atherogenesis, Notch signaling mediates the activation of osteogenesis-associated genes and induces VSMC calcification (Shimizu et al., 2009). Co-culture of VSMC with Jag-1 or Dll-4 expressing endothelial cells, or over expression of Notch1ICD in human aortic VSMC resulted in a CBF1-dependent up regulation of MSX-1, and a concomitant increase in matrix mineralization. Expression of Notch1ICD can also enhance BMP-2 activation of MSX-2 by forming a complex with SMAD1 at the promoter (Shimizu et al., 2011). On the other hand, Notch1 signaling appears to prevent the osteoblastic-like pathways in VSMC and protect against aortic valve calcification through repression of BMP-2 (Nigam and Srivastava, 2009). In line with this, HEY1 was found to physically interact with the osteoblast lineage-associated transcription factor Runx2 and repress its transcriptional activity (Garg et al., 2005). Notch1 mutations abrogated this effect, thus increasing the likelihood of calcium deposition. These studies demonstrate that the specific function of a single Notch receptor must be defined on a case-by-case basis, and that its function can vary significantly across the cardiovascular system during the onset of disease.

Notch signaling has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). PAH is characterized by narrowing of the small arteries of the lung, and increased pressure in the lung vasculature, which leads to multi-symptomatic clinical presentation that may result in heart valve disease, pulmonary embolism, or congestive heart failure. Excessive VSMC proliferation in the pulmonary arteries serves as a major factor in the occlusion of luminal space and increase in pulmonary vascular resistance. Recent reports indicate Notch3 as a marker and predictor of the severity of PAH (Li et al., 2009b). In this report, Li and colleagues show higher than normal levels of Notch3 and downstream target HES5 in lung VSMC derived from PAH patients. Lung VSMC proliferation was shown to be dependent on the Notch3–HES5 signaling axis. Notch3 null mice are resistant to pulmonary hypertension, and blockade of Notch signaling is sufficient to reverse PAH. Additionally, constitutive activation of the Notch3 pathway in VSMC lines inhibits contact-dependent growth inhibition and decreases p27kip levels (Havrda et al., 2006). Gamma secretase inhibitors have been proposed as a potential therapy to decrease Notch3 signaling in lung VSMC. However, since gamma secretase has numerous substrates (Haapasalo and Kovacs, 2011), this strategy is likely to have undesired side effects, such as toxicity to cell populations that rely on active Notch signaling (Riccio et al., 2008). As our knowledge of Notch signaling increases, therapies targeting specific receptors or pathways are likely to have strategic advantages (Wu et al., 2010).

Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is associated with Notch3 mutations. CADASIL patients have non-atherosclerotic, non-arteriosclerotic lesions in the small arteries of the cerebral and systemic vasculature. Symptoms in humans include susceptibility to ischemic attacks, migraines, subcortical dementia with pseudobulbar palsy, mood disorders, stroke, and ultimately early death (Chabriat et al., 1995). Genetic analysis performed in two unrelated families linked the disease to chromosome 19q12 (Tournier-Lasserve et al., 1993), which falls within the human NOTCH3 gene. The Notch3ECD contains 34 EGF encoded by exons 2–24, however mutations in exons 3 or 4 account for approximately 70% diagnosed with a CADASIL mutation (Joutel et al., 1997). Abnormal accumulation of Notch3ECD was observed in cerebral microvasculature of CADASIL patients close to granular osmiophilic material (GOM; Joutel et al., 2000). Others have reported that Notch3ECD is a major component of GOM deposits in the dermal vasculature of CADASIL patients (Ishiko et al., 2006). These observations bring up the questions of how Notch3 mutations may contribute to the formation of GOM deposits and the progressive loss of VSMC. There is evidence that impaired glycosylation of Notch receptor by Fringe enzymes occurs in mutant Notch3 receptors in CADASIL (Arboleda-Velasquez et al., 2005), and this may affect ligand interactions or trafficking. Lastly, it is noteworthy that not all human mutations in Notch3 resulting in CADASIL can be recapitulated in mouse models. For example, mutation of arginine 141 to cysteine in Notch3 represents a common human mutation associated with CADASIL. However, genetic alteration of the homologous arginine in the mouse gene yielded no CADASIL manifestations (Lundkvist et al., 2005). The activities of the Notch3 mutant proteins will require further study to determine how impaired signaling yields the VSMC defects in CADASIL.

Alagille syndrome (also referred to arteriohepatic dysplasia) represents an autosomal dominant disorder in humans that can result in profoundly negative systemic effects on the development of the liver, kidney, eye, vertebrae, and cardiovascular system (Oda et al., 1997). For the purposes of this review, we will focus on the cardiovascular malformations associated with this syndrome. Unlike CADASIL, which involves a mutation to Notch3 receptors, Alagille syndrome is the result of a mutation within the extracellular or transmembrane encoding domain of JAG-1 at 20p12 locus in humans (Li et al., 1997; Oda et al., 1997). Specific mutations can cause aberrant glycosylation of Jagged1, resulting in dysfunctional trafficking to the cell surface (Morrissette et al., 2001) and premature termination codons in the Jagged1 transcript, leading to nonsense mediated decay. Truncated Jagged1 proteins may also act as dominant negative signaling molecules (Boyer et al., 2005). While most diagnosed cases of Alagille syndrome are linked to null mutations in JAG-1 (Spinner et al., 2001), hypomorphic mutations in NOTCH2 have been identified in a subset of patients (McDaniell et al., 2006). Interestingly, Jag-1+/− mice develop defects only in the eye (Xue et al., 1999) and do not serve as adequate models for Alagille syndrome. On the other hand, combining both a JAG-1 null allele and a Notch2 hypomorphic allele recapitulates symptoms of Alagille syndrome (McCright et al., 2002). Although the vascular phenotypes associated with Alagille syndrome can vary, it most commonly results in peripheral pulmonary stenosis. Of the known cardiovascular manifestations, complex congenital heart disease and intracranial bleeding contributed most significantly to increased mortality. Although still under investigation, it is feasible that abnormal Jagged1 interaction with Notch2 has adverse effects on the development of VSMC and the observed cardiovascular pathologies.

Concluding Remarks

Notch signaling has profound effects on VSMC development, proliferation, migration, and quiescence, and contributes to proliferative vascular diseases and inflammatory conditions such as atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis, and angiogenesis. Multiple ligands and Notch receptors are expressed in the vessel wall, both developmentally and pathologically. While some clear molecular pathways have been identified that link specific ligands, receptors, and transcriptional output, there are still many outstanding questions. It is unclear how activation of VSMC Notch receptors with Jag versus Dll ligands regulates the VSMC contractile phenotype. In addition, potential unique or overlapping functions of Notch1, Notch2, and Notch3 signaling need further clarification. Also, since VSMC are derived from a variety of sources embryonically and mature in all tissues, they maintain a heterogeneity that affects their responsiveness to Notch signaling. Finally, the role of Notch as a critical component of an integrated microenvironment needs to take into account interactions with cytokines, ECM, and other VSMC transcriptional regulators. Answering these questions in the VSMC lineage will contribute to our understanding of more global questions related to Notch and cardiovascular homeostasis and disease.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks Robert Ackroyd, P.A. and the Maine Medical Center Tissue Bank for providing human tissue samples. J. Boucher was supported by fellowships from The Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at University of Maine, Orono, and by a predoctoral fellowship from The Founders Affiliate of the American Heart Association (10PRE3680003). This work was also supported by R01 HL070865 to Lucy Liaw, and March of Dimes grant FY10-496 and R01 HD034883 to Thomas Gridley.

References

- Anderson L. M., Gibbons G. H. (2007). Notch: a mastermind of vascular morphogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 299–302 10.1172/JCI31288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson E. R., Sandberg R., Lendahl U. (2011). Notch signaling: simplicity in design, versatility in function. Development 138, 3593–3612 10.1242/dev.058693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arboleda-Velasquez J. F., Rampal R., Fung E., Darland D. C., Liu M., Martinez M. C., Donahue C. P., Navarro-Gonzalez M. F., Libby P., D’Amore P. A., Aikawa M., Haltiwanger R. S., Kosik K. S. (2005). CADASIL mutations impair Notch3 glycosylation by Fringe. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 1631–1639 10.1093/hmg/ddi171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrof S., Hynes R. O. (2009). Fibronectins in vascular morphogenesis. Angiogenesis 12, 165–175 10.1007/s10456-009-9136-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek D., Villen J., Shin C., Camargo F. D., Gygi S. P., Bartel D. P. (2008). The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 455, 64–71 10.1038/nature07242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaise R., Mahjoub M., Salvat C., Barbe U., Brou C., Corvol M. T., Savouret J. F., Rannou F., Berenbaum F., Bausero P. (2009). Involvement of the Notch pathway in the regulation of matrix metalloproteinase 13 and the dedifferentiation of articular chondrocytes in murine cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 60, 428–439 10.1002/art.24250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokzijl A., Dahlqvist C., Reissmann E., Falk A., Moliner A., Lendahl U., Ibanez C. F. (2003). Cross-talk between the Notch and TGF-beta signaling pathways mediated by interaction of the Notch intracellular domain with Smad3. J. Cell Biol. 163, 723–728 10.1083/jcb.200305112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettger T., Beetz N., Kostin S., Schneider J., Kruger M., Hein L., Braun T. (2009). Acquisition of the contractile phenotype by murine arterial smooth muscle cells depends on the Mir143/145 gene cluster. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 2634–2647 10.1172/JCI38864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borggrefe T., Liefke R. (2012). Fine-tuning of the intracellular canonical Notch signaling pathway. Cell Cycle 11, 264–276 10.4161/cc.11.2.18995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher J. M., Peterson S. M., Urs S., Zhang C., Liaw L. (2011). The miR-143/145 cluster is a novel transcriptional target of Jagged-1/Notch signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 28312–28321 10.1074/jbc.M111.221945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulos N., Helle F., Dussaule J. C., Placier S., Milliez P., Djudjaj S., Guerrot D., Joutel A., Ronco P., Boffa J. J., Chatziantoniou C. (2011). Notch3 is essential for regulation of the renal vascular tone. Hypertension 57, 1176–1182 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.170746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer J., Crosnier C., Driancourt C., Raynaud N., Gonzales M., Hadchouel M., Meunier-Rotival M. (2005). Expression of mutant JAGGED1 alleles in patients with Alagille syndrome. Hum. Genet. 116, 445–453 10.1007/s00439-005-1262-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camoretti-Mercado B., Dulin N. O., Solway J. (2003). Serum response factor function and dysfunction in smooth muscle. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 137, 223–235 10.1016/S1569-9048(03)00149-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos A. H., Wang W., Pollman M. J., Gibbons G. H. (2002). Determinants of Notch-3 receptor expression and signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells: implications in cell-cycle regulation. Circ. Res. 91, 999–1006 10.1161/01.RES.0000044944.99984.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caolo V., Schulten H. M., Zhuang Z. W., Murakami M., Wagenaar A., Verbruggen S., Molin D. G., Post M. J. (2011). Soluble Jagged-1 inhibits neointima formation by attenuating Notch-Herp2 signaling. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31, 1059–1065 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.217935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cave J. W. (2011). Selective repression of Notch pathway target gene transcription. Dev. Biol. 360, 123–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabriat H., Tournier-Lasserve E., Vahedi K., Leys D., Joutel A., Nibbio A., Escaillas J. P., Iba-Zizen M. T., Bracard S., Tehindrazanarivelo A., Gastaut J. L., Bousser M. G. (1995). Autosomal dominant migraine with MRI white-matter abnormalities mapping to the CADASIL locus. Neurology 45, 1086–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra V. S., Hong J. W., Levine M. (2009). Regulation of Hox gene activity by transcriptional elongation in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 19, 688–693 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen T., Bochaton-Piallat M. L., Neuville P., Rensen S., Redard M., van Eys G., Gabbiani G. (1999). Cultured porcine coronary artery smooth muscle cells. A new model with advanced differentiation. Circ. Res. 85, 99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement N., Gueguen M., Glorian M., Blaise R., Andreani M., Brou C., Bausero P., Limon I. (2007). Notch3 and IL-1beta exert opposing effects on a vascular smooth muscle cell inflammatory pathway in which NF-kappaB drives crosstalk. J. Cell. Sci. 120, 3352–3361 10.1242/jcs.03340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley S. D., Gurley S. B., Herrera M. J., Ruiz P., Griffiths R., Kumar A. P., Kim H. S., Smithies O., Le T. H., Coffman T. M. (2006). Angiotensin II causes hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy through its receptors in the kidney. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 17985–17990 10.1073/pnas.0605545103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de La Coste A., Freitas A. A. (2006). Notch signaling: distinct ligands induce specific signals during lymphocyte development and maturation. Immunol. Lett. 102, 1–9 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Pompa J. L., Epstein J. A. (2012). Coordinating tissue interactions: notch signaling in cardiac development and disease. Dev. Cell 22, 244–254 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B., Annaert W., Cupers P., Saftig P., Craessaerts K., Mumm J. S., Schroeter E. H., Schrijvers V., Wolfe M. S., Ray W. J., Goate A., Kopan R. (1999). A presenilin-1-dependent gamma-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature 398, 518–522 10.1038/19083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbosc S., Glorian M., Le Port A. S., Bereziat G., Andreani M., Limon I. (2008). The benefit of docosahexanoic acid on the migration of vascular smooth muscle cells is partially dependent on Notch regulation of MMP-2/-9. Am. J. Pathol. 172, 1430–1440 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi H., Iso T., Sato H., Yamazaki M., Matsui H., Tanaka T., Manabe I., Arai M., Nagai R., Kurabayashi M. (2006). Jagged1-selective notch signaling induces smooth muscle differentiation via a RBP-Jkappa-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 28555–28564 10.1074/jbc.M602749200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi H., Iso T., Yamazaki M., Akiyama H., Kanai H., Sato H., Kawai-Kowase K., Tanaka T., Maeno T., Okamoto E., Arai M., Kedes L., Kurabayashi M. (2005). HERP1 inhibits myocardin-induced vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation by interfering with SRF binding to CArG box. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 2328–2334 10.1161/01.ATV.0000185829.47163.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenga V., Fardoux P., Lacombe P., Monet M., Maciazek J., Krebs L. T., Klonjkowski B., Berrou E., Mericskay M., Li Z., Tournier-Lasserve E., Gridley T., Joutel A. (2004). Notch3 is required for arterial identity and maturation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Genes Dev. 18, 2730–2735 10.1101/gad.308904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufraine J., Funahashi Y., Kitajewski J. (2008). Notch signaling regulates tumor angiogenesis by diverse mechanisms. Oncogene 27, 5132–5137 10.1038/onc.2008.227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elia L., Quintavalle M., Zhang J., Contu R., Cossu L., Latronico M. V., Peterson K. L., Indolfi C., Catalucci D., Chen J., Courtneidge S. A., Condorelli G. (2009). The knockout of miR-143 and -145 alters smooth muscle cell maintenance and vascular homeostasis in mice: correlates with human disease. Cell Death Differ. 16, 1590–1598 10.1038/cdd.2009.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa L., Ingles-Esteve J., Aguilera C., Bigas A. (2003). Phosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta down-regulates Notch activity, a link for Notch and Wnt pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 32227–32235 10.1074/jbc.M304001200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Krebs L. T., Gridley T. (2010). Patent ductus arteriosus in mice with smooth muscle-specific Jag1 deletion. Development 137, 4191–4199 10.1242/dev.052043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouillade C., Monet-Lepretre M., Baron-Menguy C., Joutel A. (2012). Notch signaling in smooth muscle cells during development and disease. Cardiovasc. Res. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1093/cvr/cus019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer C. J., White J. B., Jones K. A. (2004). Mastermind recruits CycC:CDK8 to phosphorylate the Notch ICD and coordinate activation with turnover. Mol. Cell 16, 509–520 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi Y., Shawber C. J., Sharma A., Kanamaru E., Choi Y. K., Kitajewski J. (2011). Notch modulates VEGF action in endothelial cells by inducing Matrix Metalloprotease activity. Vasc. Cell 3, 2. 10.1186/2045-824X-3-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale N. W., Dominguez M. G., Noguera I., Pan L., Hughes V., Valenzuela D. M., Murphy A. J., Adams N. C., Lin H. C., Holash J., Thurston G., Yancopoulos G. D. (2004). Haploinsufficiency of delta-like 4 ligand results in embryonic lethality due to major defects in arterial and vascular development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 15949–15954 10.1073/pnas.0407290101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg V., Muth A. N., Ransom J. F., Schluterman M. K., Barnes R., King I. N., Grossfeld P. D., Srivastava D. (2005). Mutations in NOTCH1 cause aortic valve disease. Nature 437, 270–274 10.1038/nature03940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf K., Xi X. P., Yang D., Fleck E., Hsueh W. A., Law R. E. (1997). Mitogen-activated protein kinase activation is involved in platelet-derived growth factor-directed migration by vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension 29, 334–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grange R. W., Isotani E., Lau K. S., Kamm K. E., Huang P. L., Stull J. T. (2001). Nitric oxide contributes to vascular smooth muscle relaxation in contracting fast-twitch muscles. Physiol. Genomics 5, 35–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieskamp T., Rudat C., Ludtke T. H., Norden J., Kispert A. (2011). Notch signaling regulates smooth muscle differentiation of epicardium-derived cells. Circ. Res. 108, 813–823 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.228809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey T. M., Alzayadneh E. M., Pendergrass K. D., Chappell M. C. (2012). Review: novel roles of nuclear angiotensin receptors and signaling mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 302, R518–R530 10.1152/ajpregu.00525.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapasalo A., Kovacs D. M. (2011). The many substrates of presenilin/gamma-secretase. J. Alzheimers Dis. 25, 3–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn A. W., Resink T. J., Kern F., Buhler F. R. (1992). Effects of endothelin-1 on vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic differentiation. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 20(Suppl. 12), S33–S36 10.1097/00005344-199204002-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havrda M. C., Johnson M. J., O’Neill C. F., Liaw L. (2006). A novel mechanism of transcriptional repression of p27kip1 through Notch/HRT2 signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Thromb. Haemost. 96, 361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High F. A., Lu M. M., Pear W. S., Loomes K. M., Kaestner K. H., Epstein J. A. (2008). Endothelial expression of the Notch ligand Jagged1 is required for vascular smooth muscle development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1955–1959 10.1073/pnas.0709663105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrabe de Angelis M., McIntyre J., II, Gossler A. (1997). Maintenance of somite borders in mice requires the Delta homologue DII1. Nature 386, 717–721 10.1038/386717a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichii T., Koyama H., Tanaka S., Kim S., Shioi A., Okuno Y., Raines E. W., Iwao H., Otani S., Nishizawa Y. (2001). Fibrillar collagen specifically regulates human vascular smooth muscle cell genes involved in cellular responses and the pericellular matrix environment. Circ. Res. 88, 460–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikedo H., Tamaki K., Ueda S., Kato S., Fujii M., Ten Dijke P., Okuda S. (2003). Smad protein and TGF-beta signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 11, 645–650 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui H., Kitami Y., Tani M., Kondo T., Inagami T. (1994). Differences in signal transduction between platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) alpha and beta receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells. PDGF-BB is a potent mitogen, but PDGF-AA promotes only protein synthesis without activation of DNA synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 30546–30552 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiko A., Shimizu A., Nagata E., Takahashi K., Tabira T., Suzuki N. (2006). Notch3 ectodomain is a major component of granular osmiophilic material (GOM) in CADASIL. Acta Neuropathol. 112, 333–339 10.1007/s00401-006-0116-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iso T., Kedes L., Hamamori Y. (2003). HES and HERP families: multiple effectors of the Notch signaling pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 194, 237–255 10.1002/jcp.10208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaleco A. C., Neves H., Hooijberg E., Gameiro P., Clode N., Haury M., Henrique D., Parreira L. (2001) Differential effects of Notch ligands delta-1 and Jagged-1 in human lymphoid differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 194, 991–1002 10.1084/jem.194.7.991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin G., Zhang F., Chan K. M., Xavier Wong H. L., Liu B., Cheah K. S., Liu X., Mauch C., Liu D., Zhou Z. (2011). MT1-MMP cleaves Dll1 to negatively regulate Notch signalling to maintain normal B-cell development. EMBO J. 30, 2281–2293 10.1038/emboj.2011.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S., Hansson E. M., Tikka S., Lanner F., Sahlgren C., Farnebo F., Baumann M., Kalimo H., Lendahl U. (2008). Notch signaling regulates platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 102, 1483–1491 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.168237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutel A., Andreux F., Gaulis S., Domenga V., Cecillon M., Battail N., Piga N., Chapon F., Godfrain C., Tournier-Lasserve E. (2000) The ectodomain of the Notch3 receptor accumulates within the cerebrovasculature of CADASIL patients [see comments]. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 597–605 10.1172/JCI8047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutel A., Corpechot C., Ducros A., Vahedi K., Chabriat H., Mouton P., Alamowitch S., Domenga V., Cecillion M., Marechal E., Maciazek J., Vayssiere C., Cruaud C., Cabanis E. A., Ruchoux M. M., Weissenbach J., Bach J. F., Bousser M. G., Tournier-Lasserve E. (1997) Notch3 mutations in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), a Mendelian condition causing stroke and vascular dementia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 826, 213–217 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48472.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao H. Y., Ordentlich P., Koyano-Nakagawa N., Tang Z., Downes M., Kintner C. R., Evans R. M., Kadesch T. (1998). A histone deacetylase corepressor complex regulates the Notch signal transduction pathway. Genes Dev. 12, 2269–2277 10.1101/gad.12.15.2269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovall R. A. (2008). More complicated than it looks: assembly of Notch pathway transcription complexes. Oncogene 27, 5099–5109 10.1038/onc.2008.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs L. T., Shutter J. R., Tanigaki K., Honjo T., Stark K. L., Gridley T. (2004). Haploinsufficient lethality and formation of arteriovenous malformations in Notch pathway mutants. Genes Dev. 18, 2469–2473 10.1101/gad.1239204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs L. T., Starling C., Chervonsky A. V., Gridley T. (2010). Notch1 activation in mice causes arteriovenous malformations phenocopied by ephrinB2 and EphB4 mutants. Genesis 48, 146–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs L. T., Xue Y., Norton C. R., Shutter J. R., Maguire M., Sundberg J. P., Gallahan D., Closson V., Kitajewski J., Callahan R., Smith G. H., Stark K. L., Gridley T. (2000). Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 14, 1343–1352 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake R. J., Grimm L. M., Veraksa A., Banos A., Artavanis-Tsakonas S. (2009) In vivo analysis of the Notch receptor S1 cleavage. PLoS ONE 4, e6728. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Krantz I. D., Deng Y., Genin A., Banta A. B., Collins C. C., Qi M., Trask B. J., Kuo W. L., Cochran J., Costa T., Pierpont M. E., Rand E. B., Piccoli D. A., Hood L., Spinner N. B. (1997). Alagille syndrome is caused by mutations in human Jagged1, which encodes a ligand for Notch1. Nat. Genet. 16, 243–251 10.1038/ng0797-243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Takeshita K., Liu P. Y., Satoh M., Oyama N., Mukai Y., Chin M. T., Krebs L., Kotlikoff M. I., Radtke F., Gridley T., Liao J. K. (2009a). Smooth muscle Notch1 mediates neointimal formation after vascular injury. Circulation 119, 2686–2692 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.783340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhang X., Leathers R., Makino A., Huang C., Parsa P., Macias J., Yuan J. X., Jamieson S. W., Thistlethwaite P. A. (2009b). Notch3 signaling promotes the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat. Med. 15, 1289–1297 10.1038/nm.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limbourg A., Ploom M., Elligsen D., Sorensen I., Ziegelhoeffer T., Gossler A., Drexler H., Limbourg F. P. (2007). Notch ligand delta-like 1 is essential for postnatal arteriogenesis. Circ. Res. 100, 363–371 10.1161/01.RES.0000258174.77370.2c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner V., Booth C., Prudovsky I., Small D., Maciag T., Liaw L. (2001). Members of the Jagged/Notch gene families are expressed in injured arteries and regulate cell phenotype via alterations in cell matrix and cell-cell interaction. Am. J. Pathol. 159, 875–883 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61763-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Kennard S., Lilly B. (2009). NOTCH3 expression is induced in mural cells through an autoregulatory loop that requires endothelial-expressed JAGGED1. Circ. Res. 104, 466–475 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundkvist J., Zhu S., Hansson E. M., Schweinhardt P., Miao Q., Beatus P., Dannaeus K., Karlstrom H., Johansson C. B., Viitanen M., Rozell B., Spenger C., Mohammed A., Kalimo H., Lendahl U. (2005). Mice carrying a R142C Notch 3 knock-in mutation do not develop a CADASIL-like phenotype. Genesis 41, 13–22 10.1002/gene.20091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe I., Owens G. K. (2001). CArG elements control smooth muscle subtype-specific expression of smooth muscle myosin in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 107, 823–834 10.1172/JCI11385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manderfield L. J., High F. A., Engleka K. A., Liu F., Li L., Rentschler S., Epstein J. A. (2012). Notch activation of JAGGED1 contributes to the assembly of the arterial wall. Circulation 125, 314–323 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmur J. D., Poon M., Rossikhina M., Taubman M. B. (1992). Induction of PDGF-responsive genes in vascular smooth muscle. Implications for the early response to vessel injury. Circulation 86, III53–III60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCright B., Lozier J., Gridley T. (2002). A mouse model of Alagille syndrome: Notch2 as a genetic modifier of Jag1 haploinsufficiency. Development 129, 1075–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniell R., Warthen D. M., Sanchez-Lara P. A., Pai A., Krantz I. D., Piccoli D. A., Spinner N. B. (2006). NOTCH2 mutations cause Alagille syndrome, a heterogeneous disorder of the notch signaling pathway. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79, 169–173 10.1086/505332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald O. G., Wamhoff B. R., Hoofnagle M. H., Owens G. K. (2006). Control of SRF binding to CArG box chromatin regulates smooth muscle gene expression in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 36–48 10.1172/JCI26505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miano J. M., Long X., Fujiwara K. (2007). Serum response factor: master regulator of the actin cytoskeleton and contractile apparatus. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, C70–C81 10.1152/ajpcell.00386.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissette J. D., Colliton R. P., Spinner N. B. (2001). Defective intracellular transport and processing of JAG1 missense mutations in Alagille syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 405–413 10.1093/hmg/10.4.405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow D., Cullen J. P., Cahill P. A., Redmond E. M. (2008). Ethanol stimulates endothelial cell angiogenic activity via a Notch- and angiopoietin-1-dependent pathway. Cardiovasc. Res. 79, 313–321 10.1093/cvr/cvn108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow D., Cullen J. P., Liu W., Cahill P. A., Redmond E. M. (2010). Alcohol inhibits smooth muscle cell proliferation via regulation of the Notch signaling pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 2597–2603 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.215681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow D., Scheller A., Birney Y. A., Sweeney C., Guha S., Cummins P. M., Murphy R., Walls D., Redmond E. M., Cahill P. A. (2005). Notch-mediated CBF-1/RBP-J{kappa}-dependent regulation of human vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 289, C1188–C1196 10.1152/ajpcell.00198.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumm J. S., Schroeter E. H., Saxena M. T., Griesemer A., Tian X., Pan D. J., Ray W. J., Kopan R. (2000). A ligand-induced extracellular cleavage regulates gamma-secretase-like proteolytic activation of Notch1. Mol. Cell 5, 197–206 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80416-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam Y., Sliz P., Pear W. S., Aster J. C., Blacklow S. C. (2007). Cooperative assembly of higher-order Notch complexes functions as a switch to induce transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 2103–2108 10.1073/pnas.0611092104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda V., Miano J. M. (2012). Leiomodin 1, a new serum response factor-dependent target gene expressed preferentially in differentiated smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 2459–2467 10.1074/jbc.M111.302224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby A. C. (2006). Matrix metalloproteinases regulate migration, proliferation, and death of vascular smooth muscle cells by degrading matrix and non-matrix substrates. Cardiovasc. Res. 69, 614–624 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigam V., Srivastava D. (2009). Notch1 represses osteogenic pathways in aortic valve cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 47, 828–834 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noseda M., Fu Y., Niessen K., Wong F., Chang L., McLean G., Karsan A. (2006). Smooth muscle alpha-actin is a direct target of Notch/CSL. Circ. Res. 98, 1468–1470 10.1161/01.RES.0000229683.81357.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda T., Elkahloun A. G., Pike B. L., Okajima K., Krantz I. D., Genin A., Piccoli D. A., Meltzer P. S., Spinner N. B., Collins F. S., Chandrasekharappa S. C. (1997). Mutations in the human Jagged1 gene are responsible for Alagille syndrome. Nat. Genet. 16, 235–242 10.1038/ng0797-235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J. H., Bybee K. A., Lavie C. J. (2007). Alcohol and cardiovascular health: the razor-sharp double-edged sword. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 50, 1009–1014 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F., Liptay S., Adler G., Schmid R. M. (1998). NF-kappaB2 is a putative target gene of activated Notch-1 via RBP-Jkappa. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 2077–2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens G. K., Kumar M. S., Wamhoff B. R. (2004). Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol. Rev. 84, 767–801 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L., Gross K. W. (2005). Transcriptional regulation of renin: an update. Hypertension 45, 3–8 10.1161/01.HYP.0000151886.26341.4b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proweller A., Pear W. S., Parmacek M. S. (2005). Notch signaling represses myocardin-induced smooth muscle cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8994–9004 10.1074/jbc.M413316200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan P., Vasquez-Del Carpio R., Kaplan F. M., Wang H., Gupta A., VanWye J. D., Capobianco A. J. (2011). Hierarchical phosphorylation within the ankyrin repeat domain defines a phosphoregulatory loop that regulates Notch transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 28844–28857 10.1074/jbc.M111.265413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensen S. S., Doevendans P. A., van Eys G. J. (2007). Regulation and characteristics of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic diversity. Neth. Heart J. 15, 100–108 10.1007/BF03085963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio O., van Gijn M. E., Bezdek A. C., Pellegrinet L., van Es J. H., Zimber-Strobl U., Strobl L. J., Honjo T., Clevers H., Radtke F. (2008). Loss of intestinal crypt progenitor cells owing to inactivation of both Notch1 and Notch2 is accompanied by derepression of CDK inhibitors p27Kip1 and p57Kip2. EMBO Rep. 9, 377–383 10.1038/embor.2008.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchoux M. M., Domenga V., Brulin P., Maciazek J., Limol S., Tournier-Lasserve E., Joutel A. (2003). Transgenic mice expressing mutant Notch3 develop vascular alterations characteristic of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 162, 329–342 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63824-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata Y., Xiang F., Chen Z., Kiriyama Y., Kamei C. N., Simon D. I., Chin M. T. (2004). Transcription factor CHF1/Hey2 regulates neointimal formation in vivo and vascular smooth muscle proliferation and migration in vitro. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 2069–2074 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143936.77094.a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheppke L., Murphy E. A., Zarpellon A., Hofmann J. J., Merkulova A., Shields D. J., Weis S. M., Byzova T. V., Ruggeri Z. M., Iruela-Arispe M. L., Cheresh D. A. (2012). Notch promotes vascular maturation by inducing integrin-mediated smooth muscle cell adhesion to the endothelial basement membrane. Blood 119, 2149–2158 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweda F., Kurtz A. (2012). Regulation of renin release by local and systemic factors. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 161, 1–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]