Abstract

Background

This study was undertaken to assess the association between adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms and high-risk sexual behavior.

Methods

This cross-sectional study interviewed 462 low-income women aged 18–30 years. We used the 18-item Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) Symptom Checklist to assess ADHD symptoms. Risky sexual behaviors included sex before 15 years of age, risky sex partners in lifetime, number of sex partners in the last 12 months, condom use in the last 12 months, alcohol use before sex in the last 12 months, traded sex in lifetime, and diagnosed with sexually transmitted infection (STI) in lifetime.

Results

Mean ADHD symptom score was 19.8 (SD±12.9), and summary index of all risky sexual behavior was 1.77 (SD±1.37). Using unadjusted odds ratios (OR), women who endorsed more ADHD symptoms reported engaging in more risky sexual behaviors of all types. However, when multivariable logistic regression was applied adjusting for various sociodemographic covariates, the adjusted ORs remained significant for having risky sex partners and having ≥3 sex partners in the prior 12 months. We observed some differences in risky sexual behavior between two domains of ADHD.

Conclusions

The ADHD symptom score appears to be associated with some risky sexual behaviors and deserves further attention. A brief ADHD screening can identify this high-risk group for timely evaluation and safe sex counseling.

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is known to affect a small but significant proportion of children. It also affects a significant proportion of adults: 1%–6% meet the DSM-IV threshold for a diagnosis of adult ADHD.1–3 Those affected in childhood or as adults are at increased risk of a number of adverse outcomes, including unemployment, low income, poor academic performance, and strained family and peer relationships.4–6

An additional adverse outcome associated with ADHD may be poor sexual health. Limited data are available describing the relationship between this disorder and sexual health in adults, as the majority of research has focused on young children's behaviors or outcomes.7,8 Results of studies on sexual behavior from longitudinal studies following children to their adulthood are inconsistent. One study reported that men who had childhood ADHD were more likely than men without ADHD to report casual sex, infrequent condom use, and multiple sex partners.9 Other studies conducted on both men and women indicated that ADHD was linked with early sexual debut or failure to use condoms.10–12 In contrast, many studies have not found an association between hyperactivity and risky sexual behavior,13,14 possibly because the studies were based on highly selected samples and focused on a narrow range of risky sexual behaviors.

Most ADHD studies have focused on male participants, leading to calls for studies of ADHD-related outcomes among women.15 The purpose of this study was to fill this gap in the literature by examining the relationship between adult ADHD symptoms and risky sexual behavior among young women.

Materials and Methods

Study design and sampling

The data used in the current analysis are based on initial interviews of an ongoing longitudinal study that was approved by the University of Texas Medical Branch's (UTMB) Institutional Review Board. This study includes a sample of nonpregnant women 18–30 years of age from family planning clinics in southeast Texas between December 1, 2006, and November 30, 2010. These clinics predominantly serve women who live in small towns and have lower educational backgrounds, with lower average incomes. Participating women were reimbursed (US$30) for their time and travel.

At recruitment, bilingual trained research coordinators explained the study purpose and obtained informed oral and written consent. All study materials were available in English or Spanish. A total of 885 eligible women were interviewed at baseline, and 834 answered all questions related to ADHD symptoms. We later excluded women with drug abuse/dependence and alcohol abuse/dependence (both based on DSM-IV), as they highly correlated with other psychiatric disorders, such as conduct disorder or antisocial behavior, which display some similar symptoms to an ADHD diagnosis. Thus, our final analysis included 462 participants without a diagnosis of drug and alcohol abuse/dependence. More than half of them were African American (56%), and less than a quarter were white (22%), with a mean age of ∼24 years and an annual household income of just over US$ 6000. The sociodemographic characteristics of the 51 participants who did not answer all items of the ADHD symptom checklist were not significantly different in terms of race (p=0.08), age (p=0.14), education, (p=0.45), marital status (p=0.06), or employment (p=0.87) from those who did.

Measurements

ADHD symptoms

We used the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) Symptom Checklist developed with support from the World Health Organization (WHO).16 This tool contains 18 questions and is based on DSM-IV Criterion-A symptoms of adult ADHD.16 The questionnaire asks participants to rate how often a symptom of inattention or hyperactivity has occurred during the past 6 months on a 0 (never) to 4 (very often) scale. The 18 items can be summed to produce a full scale; the score can range from 0 to72.

Risky sexual behavior

We adapted the Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment Schedule (SERBAS) to obtain detailed information on high-risk sexual behavior for this study.17 All study participants were asked about their age at first intercourse. Participants were also asked how many different male sex partners they had in the past 12 months. In addition, participants were asked how often they used condoms in the past 12 months and had sexual intercourse under the influence of alcohol in the past 12 months. Having a risky sex partner was defined as ever having a male partner who satisfied any one of the following five criteria: (1) was HIV positive or diagnosed with AIDS, (2) had a history of using injected drugs, (3) had symptoms of a sexually transmitted infection (STI), (4) had sex with another partner during the same time as their current relationship, or (5) had sex with another man. Further, the participants were asked to report whether they had ever traded sex and whether they had ever been diagnosed with an STI, such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, human papillomavirus (HPV), syphilis, genital warts, genital herpes simplex, or HIV.

Statistical analysis

Initial univariate analyses were conducted to describe the sample characteristics. Risky sexual behavior was categorized based on common cutoff points used in other studies.9,11,12 The mean differences of the ADHD 18-item symptom score by risky sexual behavior were examined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). In a similar fashion, we compared the mean differences of inattentive (symptoms 1–9) and hyperactive/ impulsive (symptoms 10–18) ADHD domains by risky sexual behavior. Because of a small per unit change in the symptom score in logistic regression, we further divided the ADHD symptom score by 5. Thus, the odds ratios (ORs) in the ensuing logistic regression indicated each odds reflecting per 5 unit change of the symptom score. Using multivariable logistic regression, adjusted ORs were calculated to examine the relationship between various high-risk sexual behaviors and ADHD symptom scores as well as its two domains (inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive), each containing 9 items, after controlling for significant covariates. Two-tailed tests were used, and statistical significance was evaluated with a p value of <0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of our sample are shown in Table 1. The mean ADHD symptom score was 19.8±12.9 standard deviation (SD) and, after dividing by 5, was 3.96 2.57. The most prevalent risky sexual behaviors in this sample were inconsistent condom use (63%), STI diagnosis (38.3%), and having a risky sex partner (34.9%) (Table 2). One in six (17.8%) participants in our sample experienced having sex before their 15th birthday, and one in eight (11.9%) participants had ≥3 sex partners in the last 12 months. Few participants had ever traded sex (2.8%). The mean number of risky sexual behavior (summary index) that our participants were engaged in was 1.77 (SD±1.37).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Sample (n=462)

| Overall n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 103 (22.3) |

| African American | 258 (55.8) |

| Hispanic | 98 (21.2) |

| Missing | 03 (0.7) |

| Age in years | |

| Mean (SD) | 23.9 (3.7) |

| Years of schooling | |

| Mean (SD) | 11.3 (2.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Married or cohabiting | 182 (39.4) |

| Unmarried | 277 (60.0) |

| Missing | 03 (0.7) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time/Part-time | 187 (40.5) |

| Unemployed | 263 (56.9) |

| Missing | 12 (2.6) |

| Annual household income (US$) | |

| Mean (SD) | 6,260 (12,363) |

| Smoking | |

| Never | 187 (40.5) |

| Ever | 256 (55.4) |

| Missing | 19 (4.1) |

| Alcohol | |

| Never | 58 (12.6) |

| Ever | 385 (83.3) |

| Missing | 19 (4.1) |

| Adult ADHD symptom score | |

| Mean (SD) | 19.8 (12.9) |

SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

High-Risk Sexual Behavior of Study Sample (n=462)

| Total (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex before 15 years of age | |

| No | 367 (79.4) |

| Yes | 82 (17.8) |

| Missing | 13 (2.8) |

| Risky sex partners in lifetime | |

| No | 256 (55.4) |

| Yes | 161 (34.9) |

| Missing | 45 (9.7) |

| Number of sex partners in last 12 months | |

| 0–2 | 407 (88.1) |

| ≥3 | 55 (11.9) |

| Condom use in last 12 monthsa | |

| Consistent use (100%) | 66 (18.5) |

| Inconsistent use | 291 (81.5) |

| Alcohol use before sex in last 12 monthsa | |

| <50% times | 312 (87.4) |

| ≥50% times | 39 (10.9) |

| Missing | 06 (1.7) |

| Traded sex in lifetime | |

| No | 448 (97.0) |

| Yes | 13 (2.8) |

| Missing | 01 (0.2) |

| Diagnosed with STI in lifetime | |

| No | 281 (60.8) |

| Yes | 177 (38.3) |

| Missing | 04 (0.9) |

| Risky sexual behavior | |

| Summary index (SD) | 1.77 (1.37) |

Where number of sex partner in last 12 months is at least one.

STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Significantly higher mean ADHD symptom scores were observed among women with every risky sexual behavior except for those who practiced inconsistent condom use in the last 12 months and had ever traded sex (Table 3). When separated by domains, the same pattern was observed for inattentive participants but not for hyperactive/impulsive participants.

Table 3.

Mean Differences in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Symptom Score by High-Risk Sexual Behavior (n=462)

| Mean (SD) ADHD-18 score | p value | Mean (SD) of inattentive domain score | p value | Mean (SD) of hyperactive domain score | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 3.96 (2.57) | – | 1.99 (1.41) | – | 1.99 (1.38) | – |

| Sex before 15 years of age | ||||||

| No | 3.85 (2.53) | 1.92 (1.36) | 1.98 (1.37) | |||

| Yes | 4.56 (2.70) | 0.02 | 2.38 (1.58) | 0.008 | 2.26 (1.41) | 0.06 |

| Risky sex partners in lifetime | ||||||

| No | 3.24 (2.56) | 1.65 (1.39) | 1.61 (1.36) | |||

| Yes | 4.84 (2.12) | <0.0001 | 2.41 (1.23) | <0.0001 | 2.46 (1.22) | <0.0001 |

| Number of sex partners in last 12 months | ||||||

| 0–2 | 3.83 (2.59) | 1.93 (1.43) | 1.92 (1.39) | |||

| ≥3 | 4.90 (2.23) | 0.004 | 2.44 (1.16) | 0.01 | 2.50 (1.31) | 0.004 |

| Condom use in last 12 months | ||||||

| Consistent use (100%) | 4.06 (2.50) | 1.95 (1.30) | 2.11 (1.38) | |||

| Inconsistent use | 4.33 (2.40) | 0.41 | 2.19 (1.34) | 0.18 | 2.27 (1.32) | 0.72 |

| Alcohol use before sex in last 12 months | ||||||

| <50% times | 4.13 (2.41) | 2.07 (1.36) | 2.09 (1.32) | |||

| ≥50% times | 5.21 (2.35) | 0.009 | 2.69 (1.20) | 0.007 | 2.58 (1.36) | 0.03 |

| Traded sex in lifetime | ||||||

| No | 3.94 (2.56) | 1.97 (1.40) | 1.99 (1.38) | |||

| Yes | 4.83 (2.98) | 0.22 | 2.71 (1.71) | 0.07 | 2.30 (1.62) | 0.44 |

| Diagnosed with STI in lifetime | ||||||

| No | 3.70 (2.64) | 1.87 (1.44) | 1.83 (1.38) | |||

| Yes | 4.36 (2.40) | 0.009 | 2.17 (1.33) | 0.03 | 2.23 (1.36) | 0.003 |

ADHD 18-item symptom scores were divided by 5; items 1–9 from Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) Symptom Checklist16 considered as inattentive and items 10–18 considered as hyperactive/impulsive.

Unadjusted ORs revealed that women with higher ADHD symptom scores were more likely to engage in various risky sexual behaviors (Table 4). However, multivariate logistic regression adjusted for sociodemographic covariates showed that the adjusted ORs remained significant only for having risky sex partners and having ≥3 sex partners in the last 12 months. Whereas the same pattern of association was observed in hyperactive/impulsive domain, the inattentive domain showed a small difference, with higher ADHD symptom scores associated with having risky sex partners and using alcohol before sex (≥50 times) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Association of High-Risk Sexual Behavior by Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Symptom Score (n=462)

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex before 15 years of age | ||

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.11 (1.01-1.21)* | 1.06 (0.95-1.18) |

| Risky sex partners in lifetime | ||

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.31 (1.20-1.43)*** | 1.23 (1.11-1.37)*** |

| Number of sex partners in last 12 months | ||

| 0–2 | Reference | Reference |

| ≥3 | 1.17 (1.05-1.30)** | 1.15 (1.01-1.30)* |

| Condom use in last 12 months | ||

| Consistent use (100%) | Reference | Reference |

| Inconsistent use | 1.05 (0.94-1.17) | 1.03 (0.91-1.16) |

| Alcohol use before sex in last 12 months | ||

| <50% times | Reference | Reference |

| ≥50% times | 1.20 (1.04-1.36)** | 1.17 (0.99-1.38) |

| Traded sex in lifetime | ||

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.13 (0.93-1.39) | 1.16 (0.91-1.47) |

| Diagnosed with STI in lifetime | ||

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.10 (1.02-1.19)** | 1.03 (0.94-1.13) |

| Risky sexual behavior | ||

| summary index | 1.29 (1.16-1.43)*** | 1.18 (1.04-1.34)* |

ADHD 18-item symptom scores were divided by 5.

Adjusted for sociodemographic variables.

p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.0001.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Table 5.

Association of High-Risk Sexual Behavior by Two Domains of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Symptom Score (n=462)

| |

Inattentive |

Hyperactive/impulsive |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | |

| Sex before 15 years of age | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.25 (1.06-1.47)** | 1.12 (0.93-1.36) | 1.18 (0.99-1.40) | 1.09 (0.88-1.34) |

| Risky sex partners in lifetime | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.51 (1.29-1.76) | 1.40 (1.17-1.67)*** | 1.61 (1.38-1.89)*** | 1.43 (1.19-1.73)*** |

| Number of sex partners in last 12 months | ||||

| 0–2 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| ≥3 | 1.27 (1.05-1.54)* | 1.19 (0.95-1.48) | 1.34 (1.10-1.64)** | 1.37 (1.08-1.73)* |

| Condom use in last 12 months | ||||

| Consistent use (100%) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Inconsistent use | 1.15 (0.93-1.42) | 1.14 (0.91-1.43) | 1.04 (0.85-1.27) | 0.97 (0.77-1.22) |

| Alcohol use before sex in last 12 months | ||||

| <50% times | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| ≥50% times | 1.37 (1.09-1.74)** | 1.38 (1.02-1.85)* | 1.31 (1.03-1.68)* | 1.38 (0.92-1.64) |

| Traded sex in lifetime | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.39 (0.97-1.97) | 1.34 (0.90-2.00) | 1.17 (0.78-1.75) | 1.33 (0.81-2.20) |

| Diagnosed with STI in lifetime | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.16 (1.02-1.33)* | 1.03 (0.87-1.21) | 1.23 (1.07-1.41) | 1.10 (0.93-1.31) |

| Risky sexual behavior | ||||

| Summary index | 1.55 (1.27-1.88)* | 1.33 (1.06-1.67)* | 1.53 (1.27-1.86)* | 1.33 (1.05-1.68)* |

ADHD 18-item symptom checklist's items 1–9 from Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) Symptom Checklist16 considered as inattentive and items 10–18 considered as hyperactive/impulsive, and the scores were divided by 5.

Adjusted for sociodemographic variables.

p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.0001.

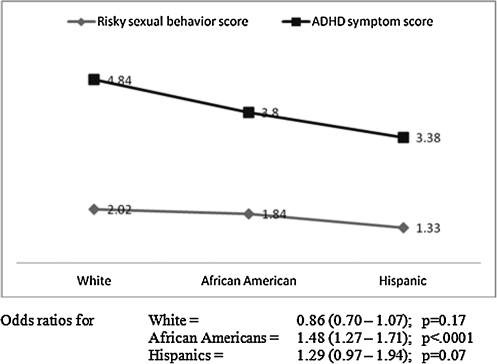

Figure 1 shows that the ADHD symptom score was highest among white women and lowest among Hispanic women, and the same pattern was observed for the summary index for risky sexual behavior. Logistic regression shows that the association was significant among African Americans (p<0.0001) and marginally significant among Hispanics (p=0.07). Furthermore, the correlations (r) between risky sexual behavior summary index and ADHD symptom score (18-item) (r=0.30, p=<0.0001), inattentive domain score (r=0.28, p=<0.0001), and hyperactivity/ impulsivity domain score (r=0.29, p=<0.0001) were all significant.

FIG 1.

Summary score for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms and risky sexual behavior by race/ethnicity.

Discussion

We found that the ADHD symptom score were associated with an increased likelihood of multiple sex partners (≥3) and risky sex partners. This is consistent with previously reported associations between ADHD and high-risk sexual behavior that were conducted on males.9,11,14 However, domain-specific ORs indicated that in the inattentive domain, higher symptom scores were associated with increased alcohol use before sex but not with multiple sex partners.

To our knowledge, this is the first study addressing a wide range of risky sexual behaviors. Previous studies either were based on selective clinical samples or focused on a narrow range of risky sexual behaviors.9,14 The higher likelihood of selecting risky sex partners suggests that women with a higher ADHD symptom score were unable to learn about their potential partner's behavior before entering into sexual relationships.18 This finding provides clear evidence of a positive association between ADHD symptom score and risky sexual behavior in women and corroborates the findings of Flory et al.9 in a study conducted on men. A higher ADHD symptom score also predicted having multiple sex partners in the last 12 months, suggesting that women with elevated levels of ADHD symptom score may have greater difficulty maintaining long-term, stable relationships. This supports results from previous studies showing higher rates of divorce and separation among women with ADHD.5,19

The null relationship between condom use and ADHD symptom score appears to reflect a complex phenomenon of condom use in young women. Studies have shown that this relationship is usually associated with the manner in which the ADHD patients evaluate the risk of contracting STI/HIV, as higher perceived risk is usually associated with higher likelihood of condom use.20 The nonsignificant relationship between ADHD symptom score and sexual debut stands in contrast to some previous findings demonstrating that involvement with delinquent peers, a poor relationship with parents, and antisocial behavior and personality disorder may initiate early sexual debut.14 In addition, among ADHD patients, other situational and contextual factors that are associated with condom use and sexual debut warrant further in-depth qualitative studies.

The significant relationship between consuming alcohol before sex and ADHD symptom score in the attentive domain is a concern. Alcohol consumption before sex may impair one's ability to make sound judgments because of mood elevation and reduction of inhibition about sexual behaviors, leading to an increased likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behaviors.21,22 Unlike the study by Ramrakha et al.,14 we found that the hyperactive/impulsivity domain was associated with two high-risk sexual behaviors. There is some evidence that the hyperactivity/impulsivity characteristics of ADHD, which have been described as an inability to stop and think before acting, may make affected individuals more vulnerable to high-risk sexual behavior as well as antisocial behavior and deviant peer affiliation.23 Further research is needed to investigate the reasons for this observed link between hyperactive/impulsivity and risky sexual behavior.

It is well known that impulsivity is an integral part of ADHD, and people with impulse control problems frequently suffer from deficits in their self-regulatory behavioral systems. Consequently, they are more likely to give in to the urge to engage in some risky sexual behaviors.24 If impulsivity is the etiologic factor, however, questions might arise as to why participants with higher inattentive domain ADHD symptom scores were also seemingly engaging in risky sexual behaviors? Additionally, it is unclear why hyperactive individuals adopted different risky sexual behaviors from those of inattentive individuals. Although we do not have definitive answer to these questions, the existing literature suggests that risky sexual behaviors adopted by hyperactive individuals are different from those adopted by inattentive individuals.14 This difference could be attributed to the inherent differences in their behaviors, attitudes, and recklessness.

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution. First, we used symptom scores, which are only an approximation of an accurate diagnosis. Second, it is a cross-sectional study, so temporal direction could not be ascertained. Third, the retrospective nature of our assessment of risky sex is vulnerable to faulty memory, and women may not know the diagnostic status of all their sex partners. Fourth, our sample was collected from young, low-income women from small cities. This selection bias may threat external validity, as these results may not be generalizable to all women. Lastly, it is not unlikely that those with the most severe ADHD problems may have dropped out, leading to underestimation of the ADHD symptom score. It is worth mentioning that we could not control for comorbid conduct disorder, antisocial behavior, personality disorder, and other factors in this analysis, although they are associated with ADHD and risky sexual behaviors.25 Further studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Conclusions

Our results, although preliminary, set the foundation for further examination of the contextual and temporal patterns of adult ADHD symptom score in relation to high-risk sexual behaviors, which pose a clear threat to public health. Our study findings suggest that it is important for health professionals to be aware that ADHD is not uncommon in this population, and underestimation of ADHD may lead to undertreatment. ADHD symptoms appear to be associated with some high-risk sexual behaviors that deserve further attention. A brief ADHD screening can identify this high-risk group for timely evaluation and safe sex counseling. Untreated ADHD individuals have higher rates of substance abuse/dependence than those with ADHD who are receiving treatment. Consequently, untreated ADHD subjects are more prone to adopt various risky sexual behaviors.26 If our findings are confirmed in subsequent investigations, brief ADHD symptom screening can be introduced in similar settings to address this public health issue.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIDA grants R01 DA020053 and K01 DA021814 awarded to Z.H.W. The first author, G.M.M.H., is supported by an NRSA training grant (T32HD055163) from NIH/NICH. A.B.B. is supported by NICHD grant K24HD043659. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institute of Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Wilens TE. The nature of the relationship between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance use. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 11):4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fayyad J. De Graaf R. Kessler R, et al. Cross-national prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:402–409. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC. Adler L. Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:716–723. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison JR. Childhood hyperactivity in an adult psychiatric population: Social factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 1980;41:40–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy K. Barkley RA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder adults: Comorbidities and adaptive impairments. Compr Psychiatry. 1996;37:393–401. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinn PO. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and its comorbidities in women and girls: An evolving picture. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10:419–423. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biederman J. Petty CR. Monuteaux MC, et al. The longitudinal course of comorbid oppositional defiant disorder in girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Findings from a controlled 5-year prospective longitudinal follow-up study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29:501–507. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318190b290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bukstein O. Substance use disorders in adolescents with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2008;19:242–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flory K. Molina BS. Pelham WE., Jr Gnagy E. Smith B. Childhood ADHD predicts risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35:571–577. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barkley RA. Fischer M. Smallish L. Fletcher K. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: Adaptive functioning in major life activities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:192–202. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000189134.97436.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown LK. Hadley W. Stewart A, et al. Psychiatric disorders and sexual risk among adolescents in mental health treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:590–597. doi: 10.1037/a0019632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galéra C. Messiah A. Melchior M, et al. Disruptive behaviors and early sexual intercourse: The GAZEL Youth Study. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177:361–363. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monuteaux MC. Faraone SV. Gross LM. Biederman J. Predictors, clinical characteristics, and outcome of conduct disorder in girls with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1731–1741. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramrakha S. Bell ML. Paul C. Dickson N. Moffitt TE. Caspi A. Childhood behavior problems linked to sexual risk taking in young adulthood: A birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1272–1279. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180f6340e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barkley RA. Major life activity and health outcomes associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(Suppl 12):10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC. Adler L. Ames M, et al. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): A short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35:245–256. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer-Bahlburg H. Ehrhardt A. Exner TM. Gruen RS. Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment Schedule-Adult-Armory Interview. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenberg JB. Childhood sexual abuse and sexually transmitted diseases in adults: A review of and implications for STD/HIV programmes. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;1(2):77–83. doi: 10.1258/0956462011924380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biederman J. Faraone SV. Spencer TJ. Mick E. Monuteaux MC. Aleardi M. Functional impairments in adults with self-reports of diagnosed ADHD: A controlled study of 1001 adults in the community. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:524–540. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosengard C. Anderson BJ. Stein MD. Correlates of condom use and reasons for condom non-use among drug users. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:637–644. doi: 10.1080/00952990600919047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sansone RA. Wiederman MW. Muennich E. Barnes J. Alcohol and drug problems and their relationship to sexual impulsivity among female internal medicine outpatients. Prim Care Companion. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10:167–168. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v10n0213h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staton M. Leukefeld C. Logan TK, et al. Risky sex behavior and substance use among young adults. Health Soc Work. 1999;24:147–154. doi: 10.1093/hsw/24.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moss SB. Nair R. Vallarino A. Wang S. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Prim Care. 2007;34:445–473. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winters KC. Botzet AM. Fahnhorst T. Baumel L. Lee S. Impulsivity and its relationship to risky sexual behaviors and drug abuse. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2009;18:43–56. doi: 10.1080/15470650802541095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mannuzza S. Klein RG. Bessler A. Malloy P. LaPadula M. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys. Educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:565–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820190067007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannuzza S. Klein RG. Truong NL, et al. Age of methylphenidate treatment initiation in children with ADHD and later substance abuse: Prospective follow-up into adulthood. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:604–609. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07091465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]