Abstract

Reprogramming somatic cells into an embryonic stem (ES) cell-like state, or induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, has emerged as a promising new venue for customized cell therapies. In this study, we performed directed differentiation to assess the ability of murine iPS cells to differentiate into bone, cartilage and fat in vitro and to maintain an osteoblast phenotype on a scaffold in vitro and in vivo. Embryoid bodies derived from murine iPS cells were cultured in differentiation medium for eight to twelve weeks. Differentiation was assessed by lineage specific morphology, gene expression, histological stain and immunostaining to detect matrix deposition. After 12 weeks of expansion, iPS derived osteoblasts were seeded in a gelfoam matrix followed by subcutaneous implantation in syngenic ICR mice. Implants were harvested at 12 weeks, and histological analyses of cell, mineral and matrix content were performed. Differentiation of iPS cells into mesenchymal lineages of bone, cartilage and fat was confirmed by morphology, and expression of lineage specific genes. Isolated implants of iPS cell derived osteoblasts expressed matrices characteristic of bone, including osteocalcin and bone sialoprotein. Implants were also stained with alizarin red and von Kossa, demonstrating mineralization and persistence of an osteoblast phenotype. Recruitment of vasculature and microvascularization of the implant was also detected. Taken together, these data demonstrate functional osteoblast differentiation from iPS cells both in vitro and in vivo and reveal a source of cells which merit evaluation for their potential uses in orthopaedic medicine and understanding of molecular mechanisms of orthopaedic disease.

Keywords: iPS cells, differentiation, osteoblasts, mesenchymal lineages

INTRODUCTION

Mouse and human fibroblasts can be reprogrammed into an embryonic stem (ES) cell-like state by transduction with a combination of transcription factors (Oct 3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc, or alternatively Oct3/4, Sox2, Nanog and Lin28) (1–5). The induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells resulting from this manipulation function in a manner indistinguishable from mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells. For example, iPS cells are capable of differentiating into cell types characteristic of the three germ layers in vitro and in vivo, they express many of the markers associated with pluripotent cells, and they have an epigenetic status similar to that of ES cells (1–5). Although the differentiation potential of iPS cell lines compared to that of ES cell lines varies between similar to less potent depending on the lines tested and the directed differentiation analyses performed (6), the accessibility and therapeutic potential of patient’s own iPS cells provides a powerful tool for cell based regenerative medicine, including bone reconstructive surgery and other orthopaedic procedures.

Though bone exhibits a remarkable regenerative capacity; aging, disease or injury often results in significant bone loss, preventing natural replacement of this tissue in the organism. While bone autograft provides the best clinical outcome for bone replacement therapy (7), it is associated with severe pain at the site of removal and high morbidity (8). In turn, allogeneic transplants carry not only the risk of immunological rejection but also the transmission of disease from donor to recipient (9). Autologous mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from bone marrow offer a promising source of cells for musculoskeletal regeneration because of their potential to differentiate into bone, cartilage and fat, as well as their potent paracrine anti-inflammatory properties (10, 11). However, the use of MSCs in orthopaedic reconstructive therapy may be restricted by their proliferative potential which significantly decreases with age (12). Due to their self-renewal capacity, patient-specific iPS cells would address this limitation by providing an unlimited source of MSCs. Recently Marion et al. demonstrated that iPS cells generated from both young and aged individuals have elongated telomeres and their telomers acquire the characteristics of ES cells (13). Agarwal et al. showed the importance of telomerase in the maintenance of iPS self-renewal (14). The MSC potential of iPS was described by Lian et al (11). The iPS cell derived mesenchymal cells were able to attenuate the injury associated with hindlimb ischemia in a rodent model and to contribute to tissue regeneration to a greater degree than bone marrow derived MSCs (BM-MSCs); however anti-inflammatory properties of these iPS cell derived MSCs remained undefined in this study. Additional studies have also shown that iPS cells can be differentiated into skeletal muscle, adipocytes and vascular lineages in vitro (15–19). Thus, similar to BM-MSCs, iPS cell derived MSCs may be used as an autologous graft in situations of fracture nonunion, osteoarthritis and intraoral defects to repair bone and cartilage and potentially reduce inflammation. Significant progress has recently been made with regard to iPS cells in musculoskeletal regenerative medicine, however the in vivo regenerative potential of these iPS cell derived lineages has not been addressed.

Several obstacles still have to be overcome before iPS cells can be studied as a potential therapy for orthopaedic medicine. Importantly, the persistence of differentiated phenotypes in vivo must be demonstrated. Given the potential of pluripotent stem cells to be expanded and differentiate into multiple lineages similar to ES cells, we hypothesized that clonal iPS cells capable of generating mesenchymal tissues could differentiate to a functional osteoblast lineage which when cultured on a scaffold would give rise to ectopic mineralized tissue nodules in vivo. Toward this hypothesis, we performed directed differentiation of iPS cells to mesenchymal cells and subsequently to the osteoblast lineage in vitro. These osteoblasts were seeded on gelatin scaffolds and studied in vitro and in vivo using syngenic mice. The osteogenic scaffolds were evaluated for stability of the osteoblast phenotype, proliferation and osteogenic matrix production.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Generation of iPS cells

Mouse iPS cells were generated by transducing freshly isolated ICR mouse dermal fibroblasts (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) with 4 retroviruses encoding murine Oct3/4, Klf4, Sox-2 and c-Myc as originally reported by Shinya Yamanaka (2). Mouse Oct3/4, Klf4 and Sox2 pMxs retroviral vectors were obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA), while the c-Myc construct was generated by cloning mouse c-Myc cDNA into a MSCV-ires-GFP vector (pMIG, Addgene). Viruses were prepared by transient transfection of Phoenix-E cells together with the pCL-Eco packaging vector. Two days post-transduction, the transduced fibroblasts were plated onto a mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder cells treated with mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and cultured in ES cell medium containing KnockOut Dulbecco’s modified Eagles medium (KO-DMEM) supplemented with 2 mM GlutaMAX-I, 0.1 mM MEM NEAA, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 15% ESC tested fetal bovine serum (FBS, Tissue Culture Biologicals, Seal Beach, CA) and 1,000 U/ml LIF (ESGRO, Millipore, Billerica, MA) and in the presence of 0.5mM Valproic Acid (20)(Chemicals purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated) until the ES cell-like looking colonies appeared in about two weeks.

Teratoma Formation

Mouse iPS cells (5 × 105 cells) were injected subcutaneously into the flank of 6 week-old Foxn1nu nude mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). The animals were monitored for 1 month for tumor formation.

Differentiation of iPS cells into mesenchymal tissues

Based on a modified protocol for embryoid body (EB) formation (21–23) mouse iPS cells were detached from a feeder layer and formed on a Petri dish in ES cell medium without LIF. After two days, EB were cultured in ES cell medium in the presence of 10−7M all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) for two days. After two days the EB were collected, cells dissociated via brief trypsinazation and analyzed by flow cytometry or replated for one day on gelatin coated plates to promote commitment toward the mesenchymal osteoblast, chondrocyte and adipogenic lineages (3 days total) (21–24). This medium was replaced with lineage differentiation medium for 3–4 weeks. In the case of adipocyte and osteoblast differentiation, EB outgrowths were used in for differentiation studies whereas the remaining three dimensional structures were washed from the culture when the differentiation medium was applied. To promote adipocyte differentiation, cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum supplemented with 500 μM isobutylmethylxanthine, 1 μM dexamethasone and 100 U/ml Humulin (human recombinant insulin). Thereafter the cells were refed every 48 hours with this media supplemented with 1 μM troglitazone for 4 weeks at which time distinct lipid droplets were observed by microscopy. Chondrocyte differentation was performed by trypsinizing EB to a single cell suspension, diluting cells to a final concentration of 2.5×105 cells/mL and forming micromass pellets by centrifugation. Micromass were cultured as nonadherent spheres in 15ml conical tubes for 4 weeks. Media was changed every 2 days. Differentiation media consisted of high glucose (4.5 g/L) DMEM as base medium and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM dexamethasone, 17 mM ascorbate-2-phosphate, 35 mM L-proline,1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1x insulin-transferrin-selenium and 10 ng/mL TGF-β3 (R&D Systems) (25). iPS cell derived EB were differentiated to the osteoblast linage by culturing cells to high density (90% confluence) followed by incubating with differentiation medium consisting of DMEM low glucose (Invitrogen), 10%FBS, 5% Pen/Strep, 1mM dexamethasone, 0.1M ascorbic acid, 1M glycerol 2 phosphate. Media was changed every 2 days and 14–17 days later and the differentiation documented by Alizarian red and Von Kossa staining. Differentiation was analyzed after 1, 4 and 8 weeks.

Lineage Phenotyping

Histochemical stains were performed as follows: Hematoxylin stain (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) was applied directly on sections for 30 seconds followed by a 10 second rinse in water. Sections were then counterstained with eosin Y (Thermo Scientific) as per standard techniques. Alizarian red staining: Cells were first fixed in 10% formalin for 5 minutes, washed twice with water, incubated with alizarian red solution for 10 minutes, then rinsed several times in water and allowed to dry. The von Kossa staining cells were rinsed in water and stained with silver nitrate for 30 minutes under a UV light. Cells were then rinsed in water and allowed to dry. Alcian blue: Chondrocyte micromass was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Micromass were then sectioned and slides were incubated with 1% alcian blue solution for 30 minutes. Slides were then washed with 0.1N HCl and allowed to dry.

Immunostaining of iPS cells: Cells were fixed in cold methanol (−20°C) for 5 minutes and saturated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were then incubated with anti-Nanog (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) antibody overnight at 4°C and secondary Alexa-conjugated fluorochromes 594 anti-rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 1 hour at room temperature.

Tissues and micromass chondrocyte cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin and sectioned. For immunofluorescence analysis, antigens were retrieved by boiling sections in 10mM sodium citrate for 10 minutes. The prepared sections were then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C and secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature, and mounted with hard set mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The primary antibodies used were against keratin 14, Krt14 (26), cytokeratin Endo-A (TROMA-1), adult skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain (A4.1025) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA) and aggrecan (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Implants were isolated as described, embedded in OCT and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen sections were cut at 25uM followed by fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies (bone sialoprotein #WVID1(9C5) and osteocalcin clone M-15 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for 12 hours, followed by a three hour incubation with fluorescently labeled secondary antibody. The secondary antibody conjugates used were Alexa-conjugated fluorochromes 594 or 488 anti-guinea pig, anti-rat and anti-mouse (Molecular Probes). Coverslips were mounted using Vectashied and nuclei identified with DAPI (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA).

Flow cytometry was performed to detect mesenchymal markers CD 90, 73, 105, 106, 133 and lack of the hematopoietic markers CD45 and c-kit as previously described (27) using a Beckman Coulter Cyan ADP. Laser lines and emission filters included 488 to detect FITC using the 530/40 filter; PE using 575/25 filter and 635nm laser line to detect APC using the 665/20 filter. Gating strategy included FSC/SCC, doublet discrimination, live dead using DAPI, and single color analysis to detect each marker. Negative gates were set to an unstained control and compensation performed using beads (BD Pharmingen).

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from fibroblasts, mouse CJ7 ES cells, iPS cells, EB and differentiated cells using RNeasy kit (Qiagen) per manufacturers protocol. Reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA followed the manufactures protocol (Invitrogen). Semi-quantitative PCR reactions were conducted using Taq Gold (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with 1μl of cDNA for 30 cycles. Primers used to detect the expression of endogenous nanog, oct3/4, and sox2 were previously published (2). Gapdh was detected using the following oligos: 5′-CGTCCCGTAGACAAAATGGT-3′ and 5′-TCTCCATGGTGGTGAAGACA. For qPCR detection of Col1a1 (mm00801666_g1), spp1 (mm01204014_m1), runx2 (mm00501584), sox9 (mn00448840_m1), and acan (mn00545807_m1), flt-1 (mm01210866_ml), pecam/CD31 (mm01242584_m1) (Applied Biosystems), 50ng of cDNA was analyzed in triplicate under using the Light Cycler 480 System (Roche Diagnostics). Levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) abundance (Applied Biosystems).

Three Dimensional Culture and in vivo Analyses of Osteoblast Phenotype

Seeding of the scaffold: Gelfoam surgical sponges (Pfizer Pharmaceuticals) were cut into one centimeter squares using sterile technique. The sponges were impregnated with bone differentiation medium. Differentiated osteoblasts at 8 weeks were trypsinized to obtain a single cell suspension. 8×106 cells were suspended in differentiation medium and sponges added. Cells were allowed to adhere for 12 hours under routine culture conditions. Sponges were then placed in a conical tube containing fresh bone differentiation medium. Medium was replaced every other day until the time of harvest.

Subcutaneous implantation of the scaffold: 12 week old ICR mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories and housed in the University of Colorado Denver central vivarium under pathogen free conditions. All procedures were performed according to the Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines at the University of Colorado Denver. Mice were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane and hair shaved off the back of the recipient mouse to minimize infection. Using aseptic technique a longitudinal 0.5 cm incision was made in the back of the mouse, the skin separated from the underlying muscle with forceps and the Gelfoam/cell implant placed in this subcutaneous pouch. The skin was closed with 3-0 nylon suture and tissue glue applied over the suture to seal. One such pocket was made in each mouse (using 15 mice). Animals were singly housed for 7 days following implant then housed in groups of 2–3 for the remaining 12 weeks of the experiment. Undifferentiated iPS cells produce teratomas therefore we did not include a control group of undifferentiated cells. The groups were performed with gelfoam controls (minus cells) or gelfoam seeded with osteoblasts 24 hours prior.

RESULTS

Generation of iPS cells

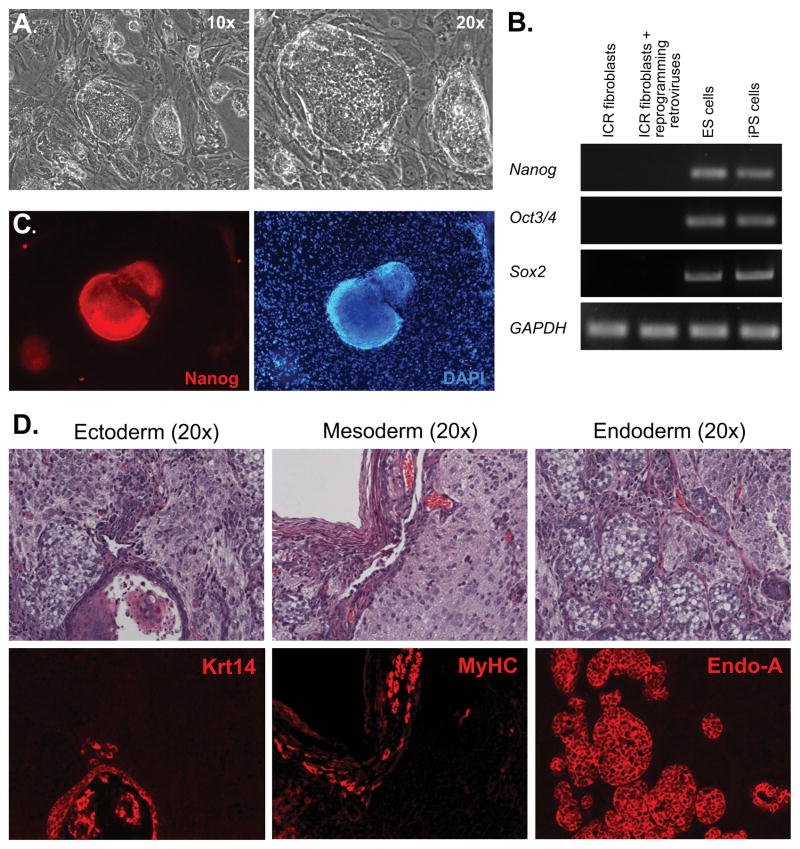

We generated iPS cells by transducing primary mouse fibroblasts with retroviral vectors encoding four reprogramming factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) (2). Similar to the observation originally made by Shinya Yamanaka (2), our iPS cells exhibited an ES cell-like morphology (Figure 1A) and reactivated expression of endogenous Oct3/4, Sox2 and Nanog, genes normally expressed in mouse ES cells and silenced in somatic cells, as determined by RT-PCR (Figure 1B). The reactivation of Nanog expression in our iPS cell clones was further confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis (Figure 1C). The generated iPS cells formed teratomas following subcutaneous injection into nude mice. Tissues from all three germ layers were present in these tumors as detected by immunofluorescence analysis (Figure 1D), thus confirming the pluripotency of our iPS cell lines. We used Krt14 as a marker for ectoderm, heavy chain myosin from skeletal muscles (MyHC) – for mesoderm and cytokeratin EndoA – for endoderm.

Figure 1. Generation of Mouse iPS Cells.

(A): Skin fibroblasts from newborn ICR mice were transduced with retroviruses expressing reprogramming factors and cultured under ES cell conditions. After two weeks in culture, colonies exhibiting an ES cell morphology under phase-contrast microscopy emerged. (B): RT-PCR analysis with primers specific to endogenous mouse Nanog, Oct3/4 and Sox2, as well as GAPDH as a control, was performed with total RNA extracted from: Lane 1: primary ICR fibroblasts; Lane 2: ICR fibroblasts transduced with four retroviral vectors and cultured for five days; Lane 3: mouse ES cells; Lane 4: mouse iPS cells. (C): iPS cell colonies were positive for Nanog, as determined by immunofluorescence analysis (red, left panel). The feeder cells used to maintain iPS cells served as a negative control for Nanog immunofluorescence (DAPl, right panel). (D): Teratomas were formed when iPS cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice. Top panels: H & E staining. Bottom panels were consecutive sections labeled with various antibodies representing three germ layers: Ectoderm (Krt14); Mesoderm (Myosin heavy chain from skeletal muscles (MyHC)); Endoderm (cytokeratin Endo-A). All images were taken with 20x objectives.

Differentiation of iPS cells into mesenchymal cell phenotypes

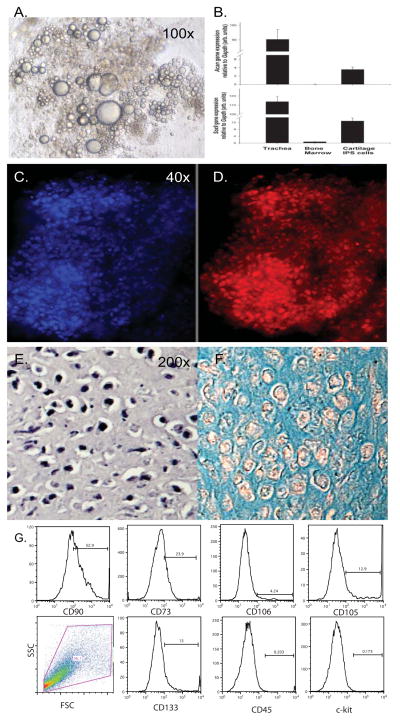

To determine the potential of a clonal iPS cell line to differentiate into the mesenchymal lineages of bone, cartilage and fat we employed differentiation protocols previously formulated for ES cells. EB differentiated from iPS cells were treated with retinoic acid in suspension culture to induce cell commitment toward mesoderm, plated on gelatin followed by culture in lineage specific differentiation medium according to Kawaguchi with slight modifications (21, 22). Fat differentiation was evident after 4 weeks by visualization of lipid droplet accumulation (Figure 2A). Cartilage differentiation was performed by culturing embryoid bodies as non-adherent cell spheres or micromass in chondrogenic medium. Analysis of mRNA extracted from iPS cells after 5 weeks of differentiation in chondrogenic medium showed expression of the chondrogenic differentiation factor, Sox-9 and the chondrocyte matrix protein Acan (Aggrecan; Figure 2B). Further investigation demonstrated immunohistological staining for aggrecan (Figure 2C&D). Differentiation into a chondrocyte phenotype was demonstrated by staining with hematoxylin and eosin and alcian blue, a cationic stain that highlights an extracellular matrix rich in polyanionic glycosaminoglycans (Figure 2E&F). We also performed flow cytometric analysis on cells obtained from 200 dissociated EB following the three day ATRA treatment to analyze for cell-surface expression of markers indicative of a mesenchymal cell. We found that the cells express varying levels of the mesenchymal markers CD 90, 73, 105, 106, 133 and lack the hematopoietic markers CD45 and ckit (Figure 2G). Lung MSC were used as a positive control (not shown).

Figure 2. Differentiation of the Mesenchymal Adipocyte and Chondrocyte Lineages from iPS cells.

Murine EB derived from iPS cells were treated with ATRA for 3 days to induce mesoderm followed by the treatment with adiopgenic or chondrogenic differentiation medium for an additional 4 weeks. Lipid droplets were visualized in adipocytes using phase-contrast microscopy 10x objective (A). Chondrogenesis was performed in micromass cultures and documented by qRT-PCR detection of Sox9 and Aggrecan (B) and by Aggrecan immunostaining 4x objective (D) with DAPI nuclear stain (C). The phenotype of chondrocytes was documented in paraffin sections by H&E (E) and alcian blue histochemical stains and photographs taken with the 20x objective (F). (G). Analysis of mesenchymal marker expression by dissociated iPS derived embryoid bodies following 3 day treatment with ATRA.

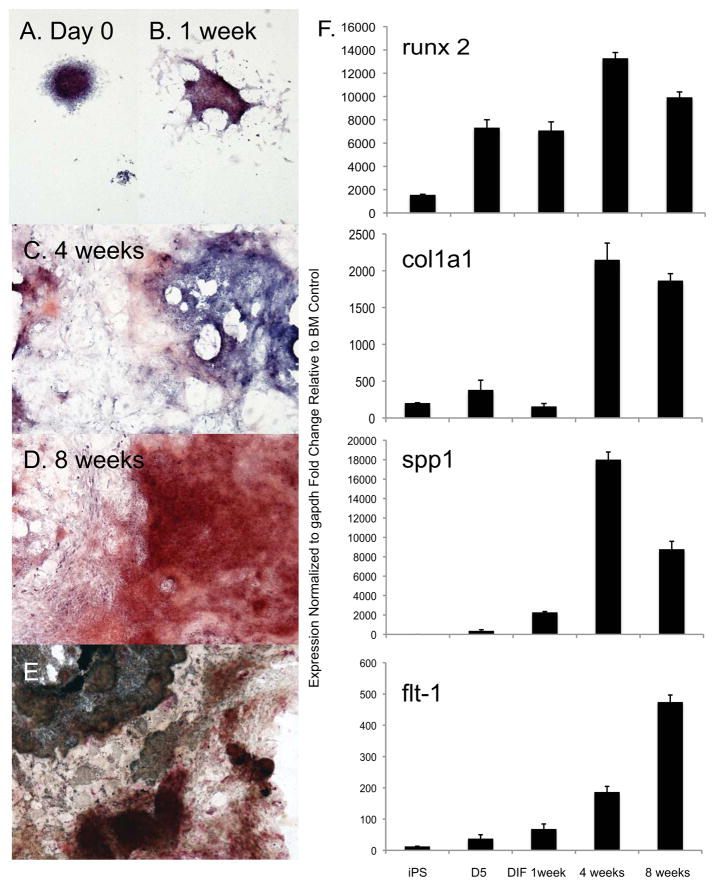

The differentiation of iPS cells into osteoblasts was performed by culturing meseodermal induced iPS in osteogenic medium for up to 8 weeks. Differentiation of iPS cells to an osteoblast phenotype from day 0 (following retinoic acid treatment) to 8 weeks was shown by histochemical staining using alizarin red to indicate sites undergoing calcium deposition and mineralization (Figure 3A–D). Additionally, von Kossa silver stain and alkaline phosphatase stain were performed at 8 weeks on the differentiated cells to demonstrate phosphate deposition and alkaline phosphatase activity (Figure 3E). Both phosphate and alkaline phosphatase activity were present in the culture. 3T3E1 pre-osteocyte cells were cultured in basal media or osteogenic differentiation media and used to demonstrate the specificity of histochemical staining (Supplemental figure 1). Analysis of mRNA extracted from iPS cells after 0, 1, 4 and 8 weeks of differentiation in osteogenic medium showed induction of the osteoblast markers, the transcription factor runx2 (cbfa1), extracellular matrix and structural proteins col1a1 (Collagen type I pro alpha I), spp1 (bone sialoprotein or osteopontin (BSP/OPN) and flt-1 (VEGF receptor 1 (28); Figure 3F). Controls for qRT-PCR primers included a bone marrow as a negative and 3T3 E1 cells cultured using osteogenic differentiation medium (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 3. Functional osteoblasts can be induced from iPS cells in vitro by the presence of dexamethasone and ascorbic acid.

(A–D): Murine EB derived from iPS cells were treated with ATRA for 3 days followed by osteoblast differentiation medium. Commitment to the osteoblast lineage was documented by four and eight weeks, as demonstrated by alizarin red stain, identified the increase in calcific deposit by osteoblasts (red), and nuclei were visualized with a hematoxylin counterstain (blue). (E): Von Kossa stain (black) and alkaline phosphatase colorimetric detection (red) were performed to characterize a differentiated osteoblast lineage. All images were taken with a 4x objective. (F,G): A temporal increase in expression of runx2, col1a1 and spp1 genes was confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis. BM= bone marrow.

These data suggest the possibility of using approaches developed for ES cell differentiation to create and expand mesenchymal lineages such as osteoblasts and chondrocytes from our iPS cell lines in vitro.

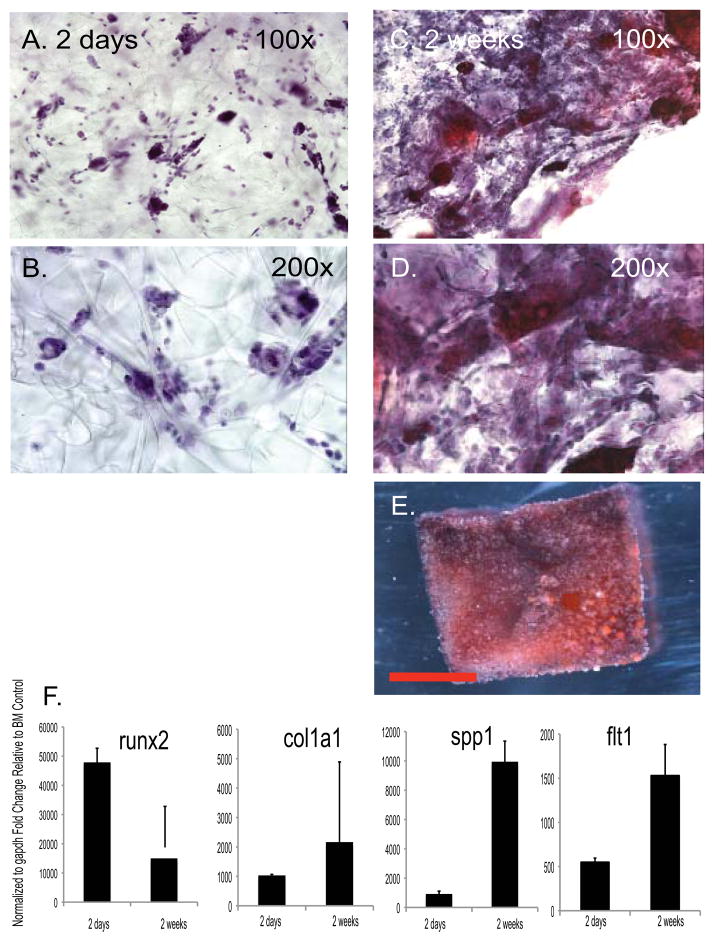

iPS cell derived osteoblasts maintain their phenotype in a scaffold in vitro and in vivo

The next step in the evaluation of iPS cell differentiation to a bone-like phenotype was the ability to maintain a differentiated osteoblast phenotype when passaged and seeded into a three-dimensional scaffold both in vitro and in vivo. After 4 weeks the osteoblast cultures had reached confluence and expressed high levels of runx2, col1a1 and spp1 (Figure 3). At that time gelfoam carriers, a biodegradable gelatin matrix, were seeded with 8 ×106 iPS cell derived osteoblasts after 8 weeks of differentiation culture and maintained in differentiation media. Implanted sponges were analyzed in vitro after 48 hours and 2 weeks of culture to confirm the presence of cells using hematoxylin staining (Figure 4A&B). After 2 weeks, sponges stained with hematoxylin and alizarin red with a hematoxylin counterstain demonstrated an increase in cell number and secreted matrix respectively (Figure 4C–E). Sponges seeded with iPS cell derived osteoblasts maintained the expression of osteoblasts markers runx2, col1a1 and spp1 after 48 hours with higher levels of col1a1 and spp1 2 weeks of differentiation in osteogenic medium (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. iPS cell derived osteoblasts maintain their phenotype and deposit bone extracellular matrix on a scaffold in vitro.

One-centimeter cubes of gelfoam sponge were seeded with iPS cell derived osteoblasts following 8 weeks of differentiation culture. (A, B): After 48 hours, the gelfoam scaffolds were stained with hematoxylin to confirm the presence of cells. Images were taken with 10x and 20x objective. (C,D): After 2 weeks, the scaffolds were stained with alizarin red and hematoxylin counterstain, which indicated an increase in the cells present within the scaffold, as well as matrix deposition by the osteoblasts. Images were taken with a 10x and 20x objective. (E): Nodules positive for alizarin red were detectable on gelfoam cubes in vitro after seeding with iPS cell derived osteoblasts cultured in differentiation medium for two weeks. A representative phase-contrast micrograph is presented. Scale bar = 5mm. (F): Maintenance or increased expression of runx2, col1a1 and spp1 genes was documented using qRT-PCR analysis. BM= bone marrow.

Following passage osteoblast cells continue to express matrix and react to alizarin red however take another week to increase the gene expression of more differentiated osteoblasts as demonstrated by analysis of seeding on sponges presented in Figure 4. Therefore we waited until 8 weeks when the osteoblasts had expanded in numbers before seeding gelfoam for in vivo studies.

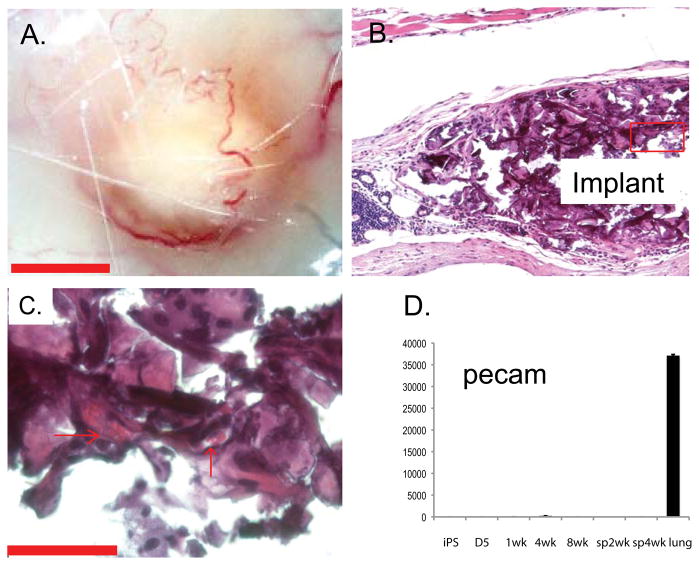

For in vivo analysis, 24 hours after seeding 8 ×106 iPS cell derived osteoblasts on gelfoam cubes, the sponges were subcutaneously implanted on the dorsal surface of immunocompetent ICR mice. After 12 weeks, no tumor formation was detected and the implants were extracted and analyzed for phenotypic markers of osteogenic cells and mineralization. Implants containing osteoblasts were isolated from 8 of 15 mice. Grossly, the implants were identifiable between the cutaneous and peritoneal muscular layers and appeared to recruit vasculature (Figure 5A). Paraffin sectioned implants (six micron thickness) stained with hematoxylin and eosin demonstrate vascularization of the implant discernable by the presence of red blood cells in the lumens of microvessels (Figure 5B&C). Additional implants were flash frozen in OCT and frozen sectioned to 25-micron thickness to maintain tissue integrity and antigenicity for immunofluorescence. To determine the presumptive origin of the microcirculation we performed qRT-PCR analysis of to detect gene expression indicative of vascular endothelial differentiation. Using the marker pecam1/CD31, which is expressed by both progenitors and differentiated endothelium, we found no evidence of vasculature in the osteoblast cultures or in vitro sponges (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Subcutaneous implantation of osteoblast seeded scaffolds recruited vasculature in vivo.

After 12 weeks, implants were identifiable (A) as surrounded by vasculature. Paraffin sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin demonstrated the subcutaneous localization of the implant (B) and the vascular supply within the implant, as evidenced by the presence of red blood cells in the lumens of microvessels (C, arrows) using phase-contrast microscopy. Scale bar = 50μM.

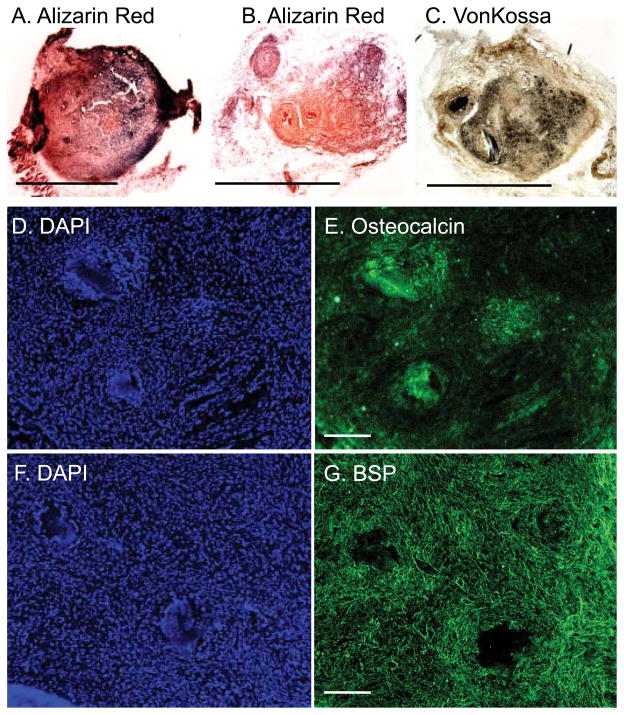

Alizarin red and von Kossa stains localized osteoblasts secreted matrix and calcium in the implants (Figure 6A–C). Fluorescent immunostaining demonstrated the presence of osteoblast markers osteocalcin and bone sialoprotein in serial sections (Figure 6D–G, Supplemental figure 3). Thus, we demonstrate that osteoblasts differentiated from iPS cells maintained their lineage-specific phenotype after passage onto scaffold both in vitro and in vivo. The phenotype of these osteoblast derived iPS appears stable at both 4 and 8 weeks following directed differentiation. In vivo formation of mineralized nodules using a mouse model suggests the persistence of a differentiated phenotype and highlights the potential for these cells to be used in graft development and cell-based therapy for musculoskeletal repair.

Figure 6. Osteoblast seeded scaffolds maintain their phenotype and deposit bone extracellular matrix in vivo.

After 12 weeks, gelfoam scaffolds were embedded in OCT, frozen and 25mM sections analyzed. Histochemical alizarin red (A&B) and von Kossa (C) staining confirmed the presence of matrix and calcium within the nodules and hematoxylin the presence of osteoblasts. (D–G): Consecutive sections were immunoreactive to osteocalcin and bone sialoprotein. DAPI was used to label nuclei. Scale bar= 2.5mm.

DISCUSSION

Cell based therapy for repair of bone and cartilage offers a promising treatment for both degenerative and genetic musculoskeletal diseases. However, engineered grafts are far from being a standard of treatment for bone and cartilage repair. BM-MSC, ES cells and more recently iPS cells have been demonstrated as having the potential to differentiate to bone and cartilage, as well as other mesenchymal lineages. Each cell type offers its own challenges. While BM-MSC may function as an autologous graft, also suited for gene therapy, and demonstrate anti-inflammatory properties; when obtained from aged donors they may demonstrate a limited ability to proliferate (11, 29, 30). While ES cells are pluripotent and exhibit high differentiation and proliferation potential, their origin is the topic of ethical debate since they must be derived from fertilized embryos. In addition, the repair of tissues with ES-derived cells may result in immune rejection, since these cells are allogeneic. Data on immunological properties of human and murine ES cells and their differentiated derivatives are still controversial, ranging from those claiming unique immune-privileged properties for ES cells (31, 32) to those which refute these conclusions (33, 34). iPS cells are the most recent addition to this cast and they offer benefits of the aforementioned cell types yet they are the least well characterized. Nevertheless, it has been shown that iPS cells function in a manner similar to ES cells: they are capable of forming multiple cell types in vitro and in vivo, they express most (but not all) of the markers associated with pluripotent cells, they have an epigenetic and telomere status similar to that of ES cells, and they can be used to make fertile mice (13, 35). The immunological properties of iPS are not well characterized.

Here we have assessed the ability of murine iPS cells to be directionally differentiated to multipotent mesenchymal cells and subsequently the osteoblast lineage in vitro. The multipotent mesenchymal cell stage was demonstrated by differentiation of iPS cell derived mesenchymal cells into three characteristic mesenchymal lineages including osteoblast, adipocyte and chondrocytes. Lian et al recently demonstrated the ability of human iPS cells to give rise to mesenchymal cells with a cell surface phenotype and differentiation potential similar to those of BM-MSC (11) using clinically compliant culture techniques optimized for ES cells (36) adapted from ES differentiation to MSC using OP9 feeder cells (37). While we also employed a differentiation strategy optimized for ES cells, however, the two strategies differ significantly. The differentiation strategy we chose to evaluate was based on the premise that ATRA treatment would increase osteoblast and chrondrocyte lineage commitment of iPS derived EB outgrowths through runx 2 induction (21–24). ATRA is known to increase neural crest markers by ES cells which provide an origin for mesenchymal elements (22). Runx 2 is expressed in neural crest derived mesenchyme by precursors to bones, teeth and chondrocytes (38). Runx 2 deficiency or downregulation results in a shift toward adipogenesis (39). We made EB from iPS cells over 2 days using a hanging drop method followed by plating on gelatin coated dishes in ES medium with ATRA for 3 days. After 3 days the medium was changed to lineage specific differentiation medium and outgrowth evaluated for expression of lineage appropriate genes. Conversely Lian et al. cultured dissociated iPS cells, without an EB and ATRA treatment stage, in medium to support MSC outgrowth containing defined factors such as basic fibroblast growth factor, platelet derived growth factor AB and epidermal growth factor (36, 37). These culture conditions required one week to detect a MSC phenotype confirmed by flow cytometric analysis to detect cell surface molecules including CD73, CD105, CD133 and the lack of hematopoietic markers CD 45 and CD34 (11). Lineage specific differentiation for both studies was 3 – 4 weeks. Following a 3 day treatment with ATRA we confirmed expression of the mesenchymal markers CD 90 (50%), lower levels of CD 73, 105, 106, 133 and lack of hematopoietic markers CD45 and ckit.

The differences between iPS cell derived mesenchymal cells and BM-MSCs provide a compelling argument for the use of iPS cell engineered cells. Lian et al. demonstrated that iPS cell derived mesenchymal cells could proliferate to 120 population doublings while maintaining a normal karyotype, had a 10-fold greater level of telomerase activity and had more of a protective effect in a rodent model of hind-limb ischemia than BM-MSCs(11). The difference between cell types was attributed to the increased ability of iPS derived mesenchymal cells to survive, engraft and promote de novo vasculogenesis and muscle differentiation. Independent groups have also demonstrated successful directed differentiation of iPS cells into adipocyte, vascular and skeletal muscle with efficiencies similar to those of ES cells (16–19).

We demonstrate for the first time iPS cells could be terminally differentiated into functional osteoblasts that would maintain their phenotype on a three-dimensional gelatin scaffold in vitro and in vivo. Since iPS cells are somatic cells manipulated to become pluripotent stem cells, it is vital that their potential to terminally differentiate and maintain a lineage specific differentiated phenotype, including bone, is documented in vivo otherwise tumorigenesis may become an issue. The osteoblasts lineage was defined by increased expression of the characteristic genes runx2, collagen typeIaI, and bone sialoprotein/osteopontin. As anticipated runx 2 expression increased with ATRA treatment while the expression of flt-1, col1a1 and spp1 genes increased with differentiation and was maintained over time in vitro (17, 24). Flt-1 is a marker of both osteoblasts and osteoclasts (28). When the osteoblasts were passaged and seeded on the gelatin scaffold the early gene runx2 initially increased and was followed after two weeks by increased expression of matrix genes collagen I and bone sialoprotein in vitro. The osteoblasts production of collagen may enhance further differentiation and secretion of more mature osteogenic matrix (40). Researchers have shown that to engineer cell-based bone grafts, in vitro commitment or differentiation of the cells used is absolutely necessary (41, 42). Duan et al. showed that enamel matrix derivatives increased runx 2 expression and may be useful in periodontal tissue regeneration (43). Osteogenic matrix production was confirmed by alizarin red stain and von Kossa to detect mineralization. Isolated implant structures demonstrated the presence of a microcirculation, which is necessary to support complete osteoblastic cell differentiation and functional bone tissue generation. The cells present in the implant formed a matrix which consisted in part of bone sialoprotein and osteocalcin. Additionally remodeling occured in the implant. Following implantation the osteoblasts were initially spread apart on the sponge – like scaffold. Histological analysis of the tissue revealed the iPS derived osteoblasts were densely packed with detectable microvasculature and circulation. Because the iPS derived osteoblast cultures lacked the endothelial marker pecam/CD31 the circulation was likely host derived. The iPS cell derived osteoblasts did not form tumors in syngenic, or non-immunocompromised, mice which indicates a stable phenotype and no reversion to an embryonic stage of differentiation. These results are in direct contrast to the implantation of undifferentiated iPS or mixtures of undifferentiated iPS and differentiated iPS derived cells which under all circumstances when subcutaneously implated formed teratomas.

This study presents evidence that iPS cells can serve as a potential source of osteoblasts. These iPS cell derived osteoblasts increase their expression of bone specific genes and osteogenic matrix when seeded on a gelatin scaffold in vitro and in vivo, demonstrating their potential use in cell-based therapy. However, future studies are necessary to extend and confirm these conclusions using additional criteria. First, in addition to in vitro commitment or differentiation of the cells used to engineer a bone graft - the environmental conditions in vivo must promote and support osteogenesis (41, 42). Additional factors may be impregnated into the scaffold which would enhance bona fide bone formation. Second, the differentiation of ES cells to osteoblasts is affected or enhanced in culture with various scaffolds, including nanofiber (44, 45). Ideal scaffold properties that support terminal differentiation in vivo must be defined. Lastly, the issue of reproducibility of engineered tissues using human cells still exists. To date most studies have been performed using human ES cells and BM-MSC. With multiple cell types available the most ideal selection markers for cells used to seed grafts capable of inducing stable bone must be identified (46). Additionally human iPS cells must be evaluated for the same potential. The use of integrating virus in human cells poses problems and risks however Somers et al. recently described the generation of human iPS from various disease populations using a polycistronic construct which can be removed form the host genome (47).

In summary, we performed directed differentiation of iPS cells to mesenchymal cells and subsequently the osteoblast lineage in vitro. These osteoblasts were seeded on gelatin scaffolds where they demonstrated stability of the osteoblast phenotype, proliferation and osteogenic matrix production both in vitro and in vivo. The maintenance of a stable osteoblast phenotype by iPS cell derived osteoblasts in vivo spotlights these cells as a viable source for further study, in combination with ES and MSCs, for clinical cell-based therapy to treat musculoskeletal diseases. Additionally, the expansion and differentiation potential of patient specific iPS cells also provides the scientific community with a valuable tool to study the cell-based mechanisms of bone and cartilage diseases. Taken together, a better understanding of these processes promise to offer new therapeutic avenues in the long term.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Acknowledgments: This work was funded by R03HL096382-01, 1R01 HL091105-01 to SM; NIH grants AR052263 and AR50252 to DRR; a research grant from the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association (DebRA) International from DebRA Austria to GB and DRR. Additional support was provided by DK NIDDK R01-078966.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

Each author’s contribution(s) to the manuscript:

Ganna Bilousova: conception and design, collection and/or assembly of data, provision of study material or patients data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing; Du Hyun Jun: conception and design, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation; Karen B. King: Provision of study material or patients, data analysis and interpretation, Final approval of manuscript; Stijn De Langhe: Collection and/or assembly of data; Wallace S Chick: Conception and design; Enrique C Torchia: Collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation; Kelsey Chow: Collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation; Dwight Klemm: Collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation; Dennis Roop: Financial support, provision of study material or patients Susan M Majka: Conception and design, financial support, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

References

- 1.Takahashi K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wernig M, et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448(7151):318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamanaka S. Strategies and new developments in the generation of patient-specific pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(1):39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318(5858):1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel G. Reprogrammed Cells Come Up Short, for Now. Science. 2010;327(5970):1191. doi: 10.1126/science.327.5970.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damien CJ, Parsons JR. Bone graft and bone graft substitutes: a review of current technology and applications. J Appl Biomater. 1991;2(3):187–208. doi: 10.1002/jab.770020307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arrington ED, Smith WJ, Chambers HG, Bucknell AL, Davino NA. Complications of iliac crest bone graft harvesting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(329):300–309. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kainer MA, et al. Clostridium infections associated with musculoskeletal-tissue allografts. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(25):2564–2571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa023222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granero-Molto F, Weis JA, Longobardi L, Spagnoli A. Role of mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative medicine: application to bone and cartilage repair. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2008;8(3):255–268. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lian Q, et al. Functional Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived From Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Attenuate Limb Ischemia in Mice. Circulation. 2010;121(9):1113–1123. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.898312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stenderup K, Justesen J, Clausen C, Kassem M. Aging is associated with decreased maximal life span and accelerated senescence of bone marrow stromal cells. Bone. 2003;33(6):919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marion RM, et al. Telomeres Acquire Embryonic Stem Cell Characteristics in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. 2009;4(2):141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal S, et al. Telomere elongation in induced pluripotent stem cells from dyskeratosis congenita patients. Nature. 2010;464(7286):292–296. doi: 10.1038/nature08792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li F, Bronson S, Niyibizi C. Derivation of murine induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) and assessment of their differentiation toward osteogenic lineage. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2010;109(4):643–652. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizuno Y, et al. Generation of skeletal muscle stem/progenitor cells from murine induced pluripotent stem cells. FASEB J. 2010;24(7):2245–2253. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-137174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tashiro K, et al. Efficient Adipocyte and Osteoblast Differentiation from Mouse Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells by Adenoviral Transduction. Stem Cells. 2009;27(8):1802–1811. doi: 10.1002/stem.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taura D, et al. Adipogenic differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells: comparison with that of human embryonic stem cells. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(6):1029–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taura D, et al. Induction and Isolation of Vascular Cells From Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells--Brief Report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(7):1100–1103. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huangfu D, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from primary human fibroblasts with only Oct4 and Sox2. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(11):1269–1275. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawaguchi J. Generation of osteoblasts and chondrocytes from embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;330:135–148. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-036-7:135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawaguchi J, Mee PJ, Smith AG. Osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of embryonic stem cells in response to specific growth factors. Osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of embryonic stem cells in response to specific growth factors. 2005;36(5):758–769. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dani C, Smith AG, Dessolin S, Leroy P, Staccini L, Villageois P, Darimont C, Ailhaud G. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells into adipocytes in vitro. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1279–1285. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.11.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiper-Bergeron N, St-Louis C, Lee JM. CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein {beta} Abrogates Retinoic Acid-Induced Osteoblast Differentiation via Repression of Runx2 Transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(9):2124–2135. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Haaften T, et al. Airway Delivery of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Prevents Arrested Alveolar Growth in Neonatal Lung Injury in Rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(11):1131–1142. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200902-0179OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuspa SH, Kilkenny AE, Steinert PM, Roop DR. Expression of murine epidermal differentiation markers is tightly regulated by restricted extracellular calcium concentrations in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1989;109(3):1207–1217. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.3.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin J, et al. Adult lung side population cells have mesenchymal stem cell potential. Cytotherapy. 2008;10(2):140–151. doi: 10.1080/14653240801895296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maes CaCG. Madame Curie Bioscience Database. 2008. VEGF in Development: Vascular and Nonvascular Roles of VEGF in Bone Development. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noh Hye Bin H-JA, Lee Woo-Jung, Kwack KyuBum, Kwon Young Do. The molecular signature of in vitro senescence in human mesenchymal stem cells. Genes & Genomics. 2010;32(1):87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roobrouck VD, Ulloa-Montoya F, Verfaillie CM. Self-renewal and differentiation capacity of young and aged stem cells. Experimental Cell Research. 2008;314(9):1937–1944. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zavazava N. Embryonic stem cells and potency to induce transplantation tolerance. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2003;3(1):5–13. doi: 10.1517/14712598.3.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koch CA, Geraldes P, Platt JL. Immunosuppression by embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26(1):89–98. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grinnemo KH, et al. Human embryonic stem cells are immunogenic in allogeneic and xenogeneic settings. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;13(5):712–724. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swijnenburg RJ, et al. Embryonic stem cell immunogenicity increases upon differentiation after transplantation into ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 2005;112(9 Suppl):I166–172. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.525824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448(7151):313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lian Q, et al. Derivation of Clinically Compliant MSCs from CD105+, CD24 Differentiated Human ESCs. Stem Cells. 2007;25(2):425–436. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barberi T, Willis LM, Socci ND, Studer L. Derivation of Multipotent Mesenchymal Precursors from Human Embryonic Stem Cells. PLoS Med. 2005;2(6):e161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.James MJ, Järvinen E, Wang XP, Thesleff I. Different Roles of Runx2 During Early Neural Crest–Derived Bone and Tooth Development. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2006;21(7):1034–1044. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enomoto H, et al. Runx2 deficiency in chondrocytes causes adipogenic changes in vitro. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(3):417–425. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao G, Wang D, Benson MD, Karsenty G, Franceschi RT. Role of the ±2-Integrin in Osteoblast-specific Gene Expression and Activation of the Osf2 Transcription Factor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(49):32988–32994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Müller A, Mehrkens A, Schäfer DJ, Jaquiery C, Güven S, Lehmicke M, Martinetti R, Farhadi I, Jakob M, Scherberich A, Martin I. Towards an intraoperative engineering of osteogenic and vasculogenic grafts from the stromal vascular fraction of human adipose tissue. Eur Cell Mater. 2010;3(19):127–135. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v019a13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tremoleda J, Forsyth NR, Khan NS, Wojtacha D, Christodoulou I, Tye BJ, Racey SN, Collishaw S, Sottile V, Thomson AJ, Simpson AH, Noble BS, McWhir J. Bone tissue formation from human embryonic stem cells in vivo. Cloning Stem Cells. 2008;10(1):119–132. doi: 10.1089/clo.2007.0R36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan X, et al. Application of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells in periodontal tissue regeneration. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jcp.22316. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naujoks C, Langenbach F, Berr K, Depprich R, Kübler N, Meyer U, Handschel J, Kögler G. Biocompatibility of Osteogenic Predifferentiated Human Cord Blood Stem Cells with Biomaterials and the Influence of the Biomaterial on the Process of Differentiation. J Biomater Appl. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0885328209358631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith LA, Liu X, Hu J, Ma PX. The Enhancement of human embryonic stem cell osteogenic differentiation with nano-fibrous scaffolding. Biomaterials. 2010;31(21):5526–5535. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pelttari K, Wixmerten A, Martin I. Do we really need cartilage tissue engineering? Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139(41–42):602–609. doi: 10.4414/smw.2009.12742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Somers A, et al. Generation of Transgene-Free Lung Disease-Specific Human iPS Cells Using a Single Excisable Lentiviral Stem Cell Cassette. Stem Cells. 2010 doi: 10.1002/stem.495. N/A-N/A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.