Abstract

A case of human intraocular dirofilariasis is reported from northern Brazil. The nematode was morphologically and phylogenetically related to Dirofilaria immitis but distinct from reference sequences, including those of D. immitis infesting dogs in the same area. A zoonotic Dirofilaria species infesting wild mammals in Brazil and its implications are discussed.

Keywords: Dirofilaria sp., nematode, intraocular filariasis, zoonosis, human, eye, parasites, Brazil, dispatch

Zoonotic filariases are caused by nematodes of the superfamily Filarioidea and are transmitted by blood-feeding arthropods. Within this taxonomic group, nematodes of the genus Dirofilaria are among the most common agents infecting humans (1–5). The 2 main species of zoonotic concern are Dirofilaria immitis, which causes canine cardiopulmonary disease, and D. repens, which is usually found in subcutaneous tissues. In addition, zoonotic subcutaneous infections with D. tenuis in raccoons and D. ursi in bears have been reported less frequently in North America (3). Dirofilaria spp. infections in humans have been detected mostly in subcutaneous tissue and lungs (3), and 1 intraocular case of infection with D. repens was reported from Russia (1). D. immitis and D. repens are the main causes of human dirofilariasis in the Americas (4,6) and Old World (2,5), respectively.

Morphologic identification of Dirofilaria spp. is based on the body cuticle, which is smooth in D. immitis (subgenus Dirofilaria) and has external longitudinal ridges in D. repens and other species of the subgenus Nochtiella. However, in many reported cases of zoonotic dirofilariasis, specific identification was not adequately addressed (5). Twenty-eight cases of human dirofilariasis in the Old World attributed to D. immitis have been reviewed recently and attributed to D. repens (5). On the basis of this information, the suggestion was made that D. immitis populations have different infective capabilities for humans in the Old and New Worlds (5). However, this hypothesis was not supported by recent genetic comparisons of specimens from the Old World (Italy and Japan) and New World (United States and Cuba) (7; M. Casiraghi, unpub. data).

We report a case of human intraocular dirofilariasis in which a live male Dirofilaria sp. worm was recovered from the anterior chamber of a patient’s eye. Morphologic and molecular studies suggested that this zoonotic case of dirofilariasis was caused by a Dirofilaria sp. closely related to D. immitis.

The Study

On September 16, 2008, a 16-year-old boy came to the Clínica de Olhos do Pará in Pará, Brazil, with low visual acuity (0.54 m), an intraocular pressure of 44 mm Hg, and pain in the left eye. Ophthalmologic examination showed a nematode (Video) in the anterior chamber of the left eye. The patient reported no travel history in recent months preceding the onset of symptoms. Corneal edema (Figure 1, panel A) and episcleral hyperemia in the left eye were observed, and surgery for removal of the nematode was recommended. After peribulbar anesthesia, the eye was clipped and the cornea was incised with a crescent Beaver corneal knife, and the nematode was extracted with forceps and Fukasacu hook (Video). A live filarial nematode was removed from the anterior eye chamber. The patient recovered without complications after surgery.

Video.

Surgical removal of a Dirofilaria sp. nematode from the left eye of a 16-year-old boy, Brazil. VA, visual acuity; CF, count fingers; IOP, intraocular pressure. A portion of the material in this video was previously published in the journal Parasites and Vectors (http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/pdf/1756-3305-4-41.pdf).

Direct Link: http://streaming.cdc.gov/vod.php?id=b35b57a52f8e7b3e41b59328391c90b020110426172643263

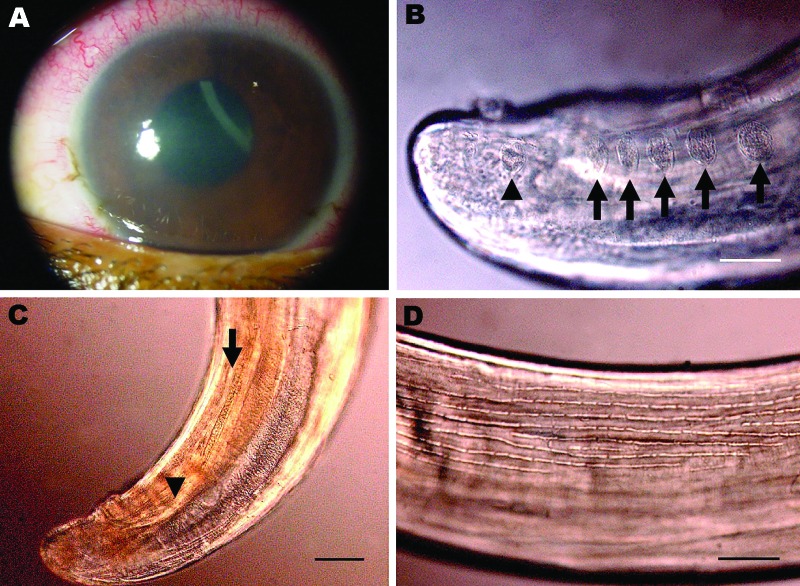

Figure 1.

Corneal edema and episcleral hyperemia in the left eye of a 16-year-old boy from Brazil and a free-swimming filarid in the anterior chamber. A) Macroscopic view. B) Five pairs of ovoid pre-cloacal papillae (arrows) and 1 postcloacal caudal papillae (arrowhead). Scale bar = 50 µm. C) Small (arrowhead) and large (arrow) spicules. Scale bar = 40 µm. D) Longitudinal ridges of the area rugosa. Scale bar = 50 µm.

The parasite (deposited at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Parasitologie Comparée, Paris, France; accession no. 143 YU) was a male filarial nematode (length 106 mm, width 400 µm). It had large caudal alae, several pairs of pedunculated papillae (Figure 1, panel B), unequal spicules, a short and thick tail, and an esophagus with a wider glandular region.

Narrow hypodermal lateral chords and the 2 lateral internal cuticular crests are typical for Dirofilaria spp (8). The specimen was not D. repens or a Nochtiella species because of the smooth body cuticle. The left spicule (length 378 µm), with a handle and lamina of equal length, was similar to that of D. immitis (Figure 1, panel C). Other measurements were similar to those of D. immitis (esophagus length 1,200 µm; right spicule length 170 µm; tail length 110 µm; width at the anus 110 µm) (8).

To confirm morphologic identification, a DNA barcoding approach was used (7). A small piece (≈3 mm) of the nematode was used for DNA extraction and amplification of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) and 12S rDNA gene fragments as described (9). Sequences were deposited in the European Molecular Biology Laboratory Nucleotide Sequence Database (accessions nos. HQ540423 and HQ540424). In accordance with morphologic identification, BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) analysis of both genes showed overall highest nucleotide similarity with those of D. immitis available in GenBank (12S rDNA, accession nos. AM779770 and AM779771; cox1, accession nos. AM749226 and AM749229).

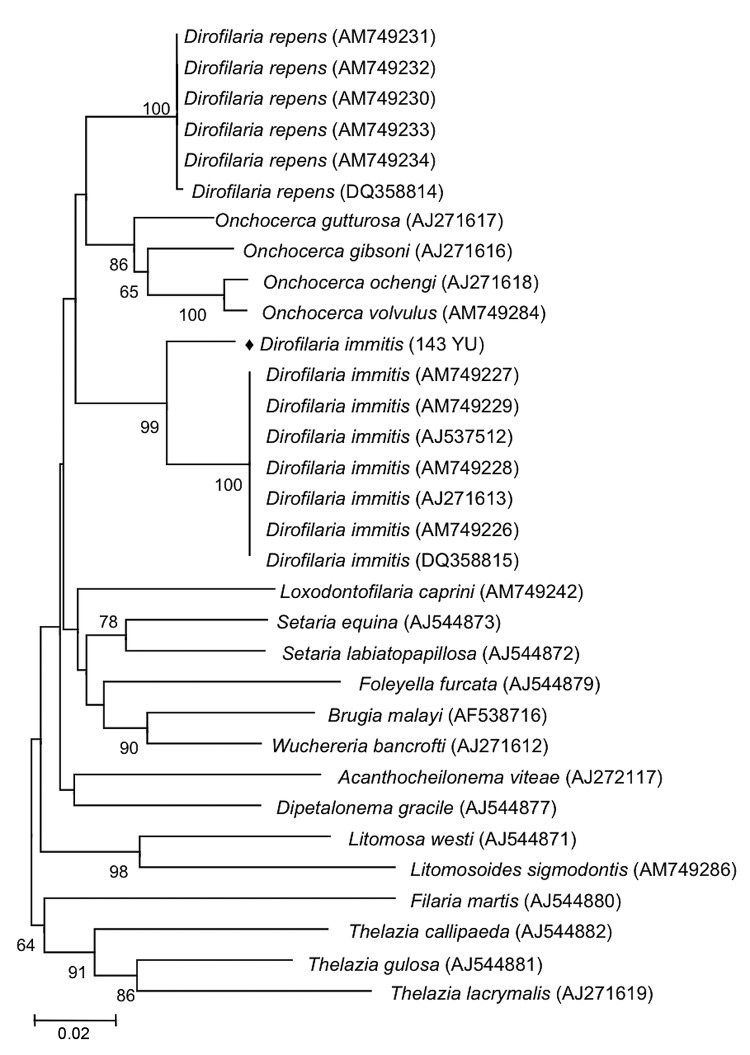

Phylogenetic analysis using cox1 sequences by MEGA 4.0 (www.megasoftware.net), a neighbor-joining algorithm, and Kimura 2-parameter correction confirmed that 143 YU clustered with D. immitis from different countries, including Australia (GenBank accession no. DQ358815) and Italy (other sequences in Figure 2). The cox1 sequence of D. immitis from a dog in Pará, Brazil, was identical with those of the same species in GenBank. Topology of 12S rDNA sequences was identical with that of cox1 sequences. However, comparison of nematode sequences with those in GenBank showed large differences in nucleotide similarities (5% and 6% for 12S rDNA and cox1, respectively).

Figure 2.

Phylogeny of filarial nematodes based on cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene sequences. Thelazia spp. species were used as outgroup. Bootstrap confidence values (100 replicates) are shown at the nodes only for values >50%. Solid diamond indicates nematode isolated in this study. Numbers in parentheses are GenBank accession numbers. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site.

Morphologic comparison with male worms isolated from dogs (1 from People’s Republic of China and 1 from Japan, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle accession nos. 63 SE and 169 YU) showed that the area rugosa (ventral ornamentation of the posterior region) was similar among all specimens examined and was composed of ≈8 longitudinal crests, each containing aligned segments (length 15–30 µm) extending 1–8 mm from the tail tip (Figure 1, panel D). Arrangement and number of caudal papillae were also similar (10). The preesophageal cuticular ring was present in D. immitis reference specimens but was not present in the specimen from Brazil. In addition, the deirids were more anterior in the worm from Brazil than in reference specimens. This finding might be caused by less growth of the nematode found in the patient from Brazil.

Similar morphologic features (small size and anterior deirids) have been reported in a D. immitis male worm from a dog in Cayenne, French Guiana (11). However, a D. spectans worm from an otter in Brazil had a similar body size and location of deirids as the worm 143 YU but a different pattern of juxtacloacal papillae.

Conclusions

In Brazil, human pulmonary dirofilariasis caused by D. immitis has been reported sporadically (12), mainly in southeastern Brazil, where the prevalence of heartworm in dogs ranges from 2.2% to 52.5% (13). The patient in this study came from a region in Brazil where canine dirofilariasis caused by D. immitis is endemic and in which the prevalence of microfilaremic dogs is <32.5% (14). Morphologic features and overall high identity of 12S rDNA and cox1 gene sequences compared with the reference DNA sequences confirmed that the worm recovered was similar to D. immitis. However, nucleotide similarity differences in comparison with other sequences of D. immitis available in GenBank (including 1 from Brazil) were 5% and 6% for 12S rDNA and cox1 genes, respectively, which are higher than the range of intraspecific variation (<0.8%) reported for D. immitis originating from the United States, Italy, and Japan (7). Such variation (>5%) has not been reported for a Dirofilaria species. Therefore, existence of a closely related species (e.g., D. spectans from otters, but also reported from a human in Brazil) (15) should be considered. Further investigations of filarial nematodes from dogs and wild mammals in Brazil are required to elucidate the identity of this Dirofilaria species and its primary hosts and vectors.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Testini, R.P. Lia, M. Barbuto, and A. Galimberti for assistance with laboratory work and data analysis and S. Uni for providing specimens of D. immitis from Japan.

This work is dedicated to Silvio Pampiglione, who enthusiastically conducted several studies in the field of human parasitology, including dirofilariasis. His exchange of ideas with D.O. and O.B. contributed to discussions in the conclusions of this report.

The Annual Meeting Program Committee awarded the video presented in this report “Best of Show” for the 2010 Joint Meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Middle East Africa Council of Ophthalmology, Chicago, Illinois, USA, October 16–19, 2010.

Biography

Dr Otranto is a professor in the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Bari, Bari, Italy. His research interests include biology and control of arthropod vector-borne diseases of animals and humans.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Otranto D, Diniz DG, Dantas-Torres F, Casiraghi M, de Almeida INF, de Almeida LNF, et al. Human intraocular filariasis caused by Dirofilaria sp. nematode, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2011 May [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1705.100916

References

- 1.Beaver PC. Intraocular filariasis: A brief review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pampiglione S, Canestri Trotti G, Rivasi F. Human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens in Italy: a review of word literature. Parassitologia. 1995;37:149–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orihel TC, Eberhard ML. Zoonotic filariasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:366–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCall JW, Genchi C, Kramer LH, Guerrero J, Venco L. Heartworm disease in animals and humans. Adv Parasitol. 2008;66:193–285. 10.1016/S0065-308X(08)00204-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pampiglione S, Rivasi F, Gustinelli A. Dirofilarial human cases in the Old World, attributed to Dirofilaria immitis: a critical analysis. Histopathology. 2009;54:192–204. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03197_a.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orihel TC, Ash LR. Parasites in human tissues. Chicago: American Society of Clinical Pathology Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferri E, Barbuto M, Bain O, Galimberti A, Uni S, Guerrero R, et al. Integrated taxonomy: traditional approach and DNA barcoding for the identification of filarioid worms and related parasites (Nematoda). Front Zool. 2009;6:1. 10.1186/1742-9994-6-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson RC, Bain O. Diplotriaenoidea, Aproctoidea and Filarioidea. In: Anderson RC, Chabaud AG, Willmott S, editors. Keys to the nematode parasites of vertebrates. Farnham Royal (UK): Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux; 1976. p. 59–116. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casiraghi M, Bazzocchi C, Mortarino M, Ottina E, Genchi C. A simple molecular method for discriminating common filarial nematodes of dogs (Canis familiaris). Vet Parasitol. 2006;141:368–72. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuelleborn F. Zur morphologie der Dirofilaria immitis Leydi (sic) 1856. Zentralbl Bakt Parasitenk Orig. 1912;65:341–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desportes C. Nouvelle description de l’extrémité céphalique de l’adulte de Dirofilaria immitis (Leidy 1856). Ann Parasitol. 1940;17:405–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodrigues-Silva R, Moura H, Dreyer G, Rey L. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis: a review. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1995;37:523–30. 10.1590/S0036-46651995000600009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Labarthe N, Guerrero J. Epidemiology of heartworm: what is happening in South America and Mexico? Vet Parasitol. 2005;133:149–56. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furtado AP, Do Carmo ES, Giese EG, Vallinoto AC, Lanfredi RM, Santos JN. Detection of dog filariasis in Marajo Island, Brazil by classical and molecular methods. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:1509–15. 10.1007/s00436-009-1584-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vicente JJ, Rodrigues HO, Gomes DC, Pinto RM. Nematóides do Brasil. Parte V: nematóides de mamíferos. Rev Bras Zool. 1997;14(Suppl 1):1–452. 10.1590/S0101-81751997000500001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]