Abstract

An intrafamilial outbreak in West Bengal, India, involving 5 deaths and person-to-person transmission was attributed to Nipah virus. Full-genome sequence of Nipah virus (18,252 nt) amplified from lung tissue showed 99.2% nt and 99.8% aa identity with the Bangladesh-2004 isolate, suggesting a common source of the virus.

Keywords: Nipah virus, viruses, full genome sequence, India, intrafamilial spread, zoonoses, dispatch

Nipah virus (NiV) causes encephalitis or respiratory signs and symptoms in humans, with high death rates (1–4). NiV outbreaks have been reported from Malaysia, Bangladesh, Singapore, and India (1,5–13). Cases in humans have been attributed to zoonotic transmission from pigs and bats (1,14). We describe a full genome sequence of NiV from an outbreak in India.

The Study

During April 9–28, 2007, five persons became ill and died within a few days at village Belechuapara, Nadia district, West Bengal, India, which borders Bangladesh. The index case-patient (case-patient 1) was a 35-year-old male farmer addicted to country liquor derived from palm juice. Hundreds of bats were observed hanging from the trees around his residence, which strongly suggested association with the infection of the index case-patient and possibility of contamination of the liquor with bat excreta or secretions.

Three patients were close relatives of case-patient 1: his 25-year-old brother (case-patient 2), his 30-year-old wife (case-patient 3), and his 39-year-old brother-in-law (case-patient 4). They became ill 12, 14, and 14 days, respectively, after contact with case-patient 1. In another person, a 28-year-old man (case-patient 5) who collected blood samples from and performed a computed tomography scan of the brain of case-patient 1, symptoms developed 12 days after contact.

No samples were available from the first 2 case-patients. Brain and lung tissues from case-patient 3, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from case-patient 4, and urine and CSF from case-patient 5 were collected. Blood samples were obtained from case-patients 4 and 5 and from 34 asymptomatic contacts from the village. Serum samples from these persons were tested for immunoglobulin (Ig) M and IgG antibodies to NiV (IgM/IgG anti-NiV) with ELISA by using reagents provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA, USA). To detect NiV RNA, urine (250 µL), CSF (100 μL), or autopsied brain or lung tissue (100 mg) were used, and RNA was extracted by using TRIzol LS and TRIzol reagents (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Nested reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) was conducted by using nucleocapsid (N) gene–based primers (8).

Attempts to isolate NiV in Vero E6 cell lines or infant mice were unsuccessful. The full-length genomic sequence was obtained from the lung of case-patient 3 by using 36 sets of primers (Table A1), Superscript II RNase reverse transcriptase for reverse transcription (Invitrogen), and Pfx polymerase for amplification (Invitrogen). The PCR products of predicted molecular size were gel eluted (QIAquick PCR Purification Kit; QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and sequenced by using BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and an automatic Sequencer (ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer; Applied Biosystems). PCR products were sequenced in both directions. To determine the genotypic status, phylogenetic analysis was conducted by using partial N gene and full NiV genome sequences with the Kimura 2-parameter distance model and neighbor-joining method available in MEGA version 3.1 software (www.megasoftware.net). The reliability of phylogenetic groupings was evaluated by the bootstrap test with 1,000 bootstrap replications.

Patients’ signs and symptoms included high fever (103°F–105°F [39.4°C–49.6°C]) with and without chills, severe occipital headache, nausea, vomiting, respiratory distress, pain in calf muscles, slurred speech, twitching of facial muscles, altered sensorium, (focal) convulsions, unconsciousness, coma, and death. The first 3 case-patients died within 2–3 days after symptom onset; case-patients 4 and 5 died after 5 and 6 days, respectively. Clinical investigations could be conducted for case-patients 4 and 5. Results of serologic tests for malaria parasite, typhoid, anti-dengue IgM, HIV, and hepatitis B surface antigen were negative. Peripheral blood profiles were within reference limits. Alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, creatine phosphokinase, and C-reactive protein were elevated. Blood gas analysis in case-patient 4 (case-patient 5 values in parentheses) showed oxygen saturation 49.4% (71%), pO2 36.1 mm Hg (44.8 mm Hg), pCO2 44.4mm Hg (44.1 mm Hg), HCO3 15.7 mmol/L (19.1 mmol/L), and pH 7.166 (7.255). Lumbar puncture of case-patient 5 showed opening pressure within reference range (1 drop/second), 2 cells/cm; all cells observed were lymphocytes. Chest radiograph indicated pulmonary edema, which suggested acute respiratory distress syndrome. At the time of admission, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans of the brain showed no abnormality.

Serum samples from case-patients 4 and 5 were positive for IgM anti-NiV. Of the clinical samples screened, brain and lung tissues of case-patient 3, CSF of case-patient 4, and urine of case-patient 5 were NiV RNA positive. Of the 34 asymptomatic contacts, 1 was positive for IgG anti-NiV and negative for IgM anti-NiV and did not report any major illness in the past. This positivity may reflect a previous subclinical infection or cross-reactivity in ELISA needing further follow-up.

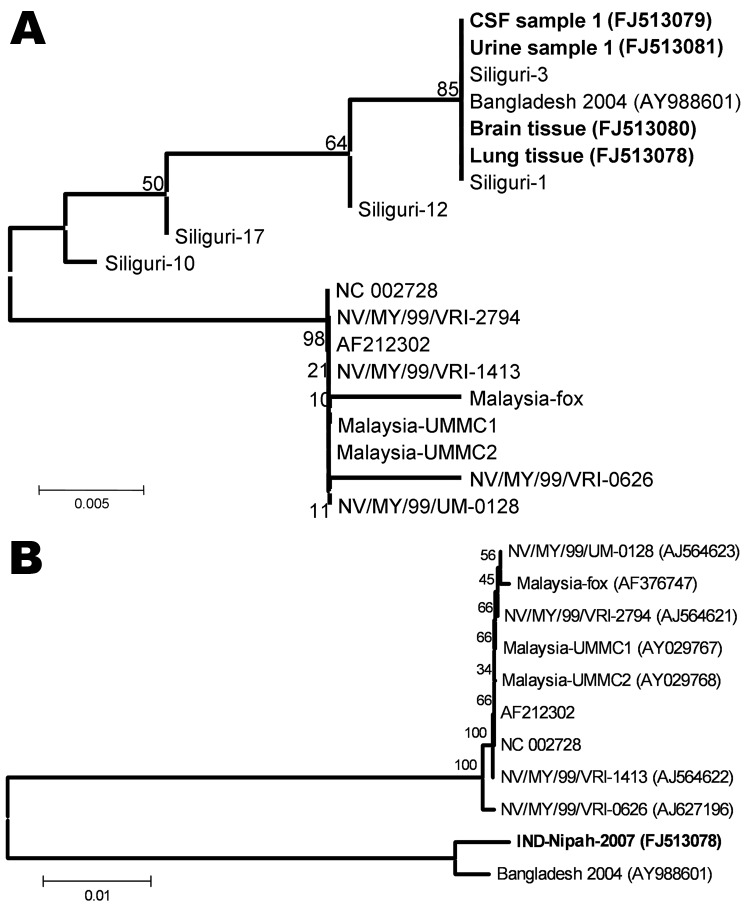

Before this report, similar cases had not been reported from the village or the surrounding area. Partial N gene sequences confirmed NiV in the clinical specimens from all 3 case-patients. Phylogenetic analysis showed that similar to findings from the 2001 outbreak study (8), viruses from Bangladesh and India clustered and diverged from the viruses from Malaysia. (Figure, panel A). The length of the full genome of the isolate from India was 18,252 nt. The sequence of this virus (INDNipah-07–1, GenBank accession no. FJ513078) was closer to the virus from Bangladesh (Figure, panel B), with 99.2% (151 nt substitutions) and 99.80% (17 aa substitutions) identity at nucleotide and amino acid levels respectively. Of the 151 nt substitutions, 9 occurred in the N open reading frame (ORF),11 in the phosphoprotein ORF, 8 in the matrix ORF, 11 in the fusion glycoprotein ORF, 7 in the attachment protein ORF, and 47 in the large polymerase ORF. Fifty-eight substitutions occurred in nontranslated regions at the beginning and the end of each ORF. The intergenic sequences between gene boundaries were highly conserved in the isolate from India, compared with the isolate from Bangladesh, which showed 1 change (GAA to UAA) between the attachment protein and large polymerase genes. No change was observed in the leader and the trailer sequences.

Figure.

A) Phylogenetic analysis based on partial nucleocapsid (N) gene nucleotide sequences (159 nt, according to Nipah virus [NiV] Bangladesh sequence, GenBank accession no. AY988601, 168–327 nt) of the 4 NiVs sequenced during this study (boldface). Five sequences of the viruses from Siliguri (8) and from representative NiV sequences obtained from GenBank indicated by the respective accession numbers. Values at different nodes denote bootstrap support. B) Full genome–based phylogenetic analysis of the NiV sequenced from the lung tissue of a patient (boldface). Representative NiV sequences obtained from GenBank are indicated by the respective accession numbers. Values at different nodes denote bootstrap support. Scale bars indicate nucleotide substitutions per site.

The Table compares amino acid substitutions in the different regions of the genome of the isolate from India with those of the viruses from Bangladesh and Malaysia. Of the 17 aa substitutions, 7 were unique to the isolate from India, and 10 were similar to the isolates from Malaysia. Overall, however, the isolate from India was closer to the isolate from Bangladesh, although distinct differences were observed.

Table. Regionwise amino acid substitutions in the Nipah virus genome*.

| Region and amino acid position | India | Bangladesh | Malaysia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphoprotein | |||

| 228 | K | R | R |

| 276 | S | G | G |

| 285 | R | H | R |

| 310 |

R

|

G |

G |

| Nucleocapsid protein | |||

| 188 | E | D | E |

| 211 |

R

|

Q |

Q |

| Matrix protein | |||

| 13 |

I

|

M |

M |

| Fusion protein | |||

| 19 | I | M | M |

| 207 | L | S | L |

| 252 |

D |

G |

D |

| Attachment protein | |||

| 304 |

V

|

I |

I |

| Large polymerase protein | |||

| 94 | I | T | I |

| 112 | K | R | K |

| 632 | N | S | N |

| 639 | N | D | N |

| 665 | T | I | T |

| 1748 | I | V | I |

To our knowledge, this is the second report of an NiV outbreak in India, identified within 1 week of the investigation. The first outbreak affected mainly hospital staff or persons visiting hospitalized patients; the 74% case-fatality rate strongly suggested person-to-person transmission (8). Both outbreaks (2001 and 2007) occurred in the state of West Bengal bordering Bangladesh wherein several outbreaks of the disease have been reported (7,9–13). However, fruit bats from West Bengal have not been screened for evidence of NiV infection. This state needs to create awareness about NiV and obligatory testing of suspected case-patients.

Conclusions

NiV caused an intrafamilial outbreak with a 100% case-fatality rate, which confirmed person-to-person transmission. The NiV strains from India and Bangladesh were closer than the Malaysian viruses. Although the outbreaks occurred in neighboring geographic areas, NiV outbreaks in Bangladesh and India were not caused by the same virus strain or by spillover.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support by Krishnangshu Ray and the cooperation of the officials of the Department of Health and Family Welfare, Government of West Bengal. We thank the staff of the Department of Virology, Microbiology and Tropical Medicine, School of Tropical Medicine, Kolkata. We also thank the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for providing ELISA reagents.

The Indian Council of Medical Research, Delhi, India, and Government of West Bengal provided financial assistance.

Biography

Dr Arankalle is a scientist at the National Institute of Virology in Pune, India. Her current research interests include hepatitis and emerging and reemerging viruses, such as chandipuravirus, chikungunya virus, avian influenza virus, Nipah virus, pandemic influenza (H1N1) 2009 virus, and undiagnosed viruses causing epidemics in India

Table A1. Primers used for full genome amplification and sequencing of Nipah virus in an interfamilial outbreak, West Bengal, India, 2007.

| Region | Forward primer, 5′ → 3′ | Reverse primer, 5′ → 3′ |

|---|---|---|

| Leader sequence and nucleocapsid protein |

F1 1–ACCAAACAAGGGAAAATATGGAT-23 | R1 287-CTCGGCTGCACTCGGAGATCTGAT-310 |

| F2 17–TATG GATACGTTAA AATATAT-37 | R2 590-TGATAACTGCAGAGACCAGAGT-611 | |

| F3 507–TCAA GACTGCTCGG GACAGCAG-528 | R3 1115-TCAATAGTAGTAGCCACACCCAT-1137 | |

| F4 999–GC TTGATGCTAC TCTACAGAG-1019 | R4 1595-TGATTGCTGGGTCATCTGTTGCATT-1619 | |

| F5 1479-T GACAGTGTGC CGAGCAGTTCTGT-1503 | R5 2115-TAAGAGGTATTGTATACTCCAGT-2137 |

|

| F6 1999-CA CACTACACTC TAATAAAGAT-2020 | ||

| Phosphoprotein |

F7 2551-TGCAGTGCAC CAGTGGAGAA TCT-2573 | R6 2594-CACCTCCATCATCCTTAGAC-2613 |

| F8 3017-TTCT CCTGTGATTG CTGAACACT-3039 | R7 3081-TCCAAATTGACATTTCTGTTAGT-3103 | |

| F9 3528-GAT AAGACTGAGATCACCAGCGA T-3551 | R8 3627-CAGATGGATATTTCTCGTCTGT-3648 | |

| F10 4054-CTTGAGTC TATTGACAGG GTTCT-4075 | R9 4176-TCACTGGTTTAAGCTCAGGATT-4197 | |

| F11 4576-TCTTC TACATGTAGA CAGTAG-4596 |

R10 4692-TCATGCTACATACACTTCAAT-4712 |

|

| Matrix protein |

F12 5125-GAGCAT TTCAAGTGAG TCT-5143 | R11 5181-TTATCAAGATACCCACCATTCT-5202 |

| F13 5586-TTGAT CAGATACAGC TCGAC-5605 | R12 5662-TAGTTCGTGGAATCATGTAGATT-5684 | |

| F14 6091-GCCTTCTGTT CCGAGAGAGT T-6111 |

R13 6123-TGTATTGTCAATGAAGACATCAT-6145 |

|

| Fusion protein |

F15 6621-GTTGGTAGAC CTATCAATCA TAT-6643 | R14 6713-CACTGCACTCCGAGATCATC-6732 |

| F16 7105-GCAGCA TAGAATCAAC TAATG-7125 | R15 7161-GCGGTCAGTACATAGACTGT-7180 | |

| F17 7522-TCCAACAGG CCTATATCCA AG-7542 | R16 7570-TGCTGATCCATTCTGAATTGT-7590 | |

| F18 8078-GCT CAACGACTCCTTGATACTGT T-8110 | R17 8130-TACAGTATGATCATAGACAACAT-8152 |

|

| F19 8638-TGTACTTGCAATT ATACATTGT-8659 | ||

| Attachment protein |

F20 9121-GATCCATTGT AATCATAGTG-9140 | R18 8723-TATCCAATGAGTTATGGACCT-8743 |

| F21 9630-T ACTTTGCATA TAGCCACCTG-9650 | R19 9202-TGCTGGATACTCTGCAATGCAT-9223 | |

| F22 10099-TC GCAGAGTGTC AATACAGCAA ACCT-10124 | R20 9698-TGTCTAGTACCTCTCCAACTCCT-9720 | |

| F23 10531-GCAACCAGAC CGCAGAGAAT CCT-10553 | R21 10149-TATAATGACTGTTTGGTCTAAT-10170 | |

| F24 11062-TCAGAGTTA ACAGTCTATA CAT-11083 |

R22 10561-TACTTCATTATCTTTGAATACAG-10583 | |

| R23 11104-CATTGATTGTCATCACTATGC-11124 | ||

| Large polymerase protein |

F25 11668-TGC ATATTGCGTA CCCTGAATGT-11690 | R24 11724-TGTTATCAAGTTTGCTAGTCAT-11745 |

| F26 12151-GGATGATGAT GGAGACAACA AT-12172 | R25 12200-GAGGGCATTGGACCTCGAGATT-12221 | |

| F27 12681-GCACATGCAT CTAAGCATAT-12700 | R26 12738-TTCCCAGTTCTTGACACAATCATC-12761 | |

| F28 13221-TCAGTTCCTC GTGGAAACAG TC-13241 | R27 13252-TATATTATTGATGGATTGAGGAT-13274 | |

| F29 13776-GATGA TATATTCATT CATTATCCT-13779 | R28 13859-TCTCATAGGCACTCAAGAAT13878 | |

| F30 14244-TCAAGGA ATGTCGGCTA TTGTAT-14266 | R29 14287-TCAGTTGATATAAGGAGTTGCT-14308 | |

| F31 14728-TAG CTAGCTTCCT GATGGACAGG-14750 | R30 14770-TTGTCCAGTATCTCATGAGCGG-14791 | |

| F32 15241-GTACAGATGA GAGATCAGAT AT-15262 | R31 15304-TACTGTCGCAATCCTGATAGCAG-15326 | |

| F33 15791-TGATCCAGAT CCTGTTTCAG-15810 | R32 15872-TGAAGCTCCTCAGTTGACCAT-15892 | |

| F34 16381-CTGTGATTAA CCTACGAGAG GATAT-16405 | R33 16461-TTCAGATCTATTATCCAAGGAGG-16483 | |

| F35 17038-CAGGTCAGAGAGA ACTGAAGCT-17059 | R34 17064-TCAGCAATCGAGTATTCGGATGG-17086 | |

| F36 17371-TCTCAAGATT ATTTAACATG T-17391 | R35 17429-TAGAATCTGGGTTGCTATACACT-17451 |

|

| F37 17831-TTCACATCAT TTGGAACCGT AT-17852 | ||

| Trailer sequence | R36 18230-ACCGAACAAGGGTAAAGAAGAAT-18252 |

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Arankalle VA, Bandyopadhyay BT, Ramdasi AY, Jadi R, Patil DR, Rahman M, et al. Genomic characterization of Nipah virus, West Bengal, India. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2011 May [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1705.100968

References

- 1.Chua KB, Bellini WJ, Rota PA, Harcourt BH, Tamin A, Lam SK, et al. Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Science. 2000;288:1432–5. 10.1126/science.288.5470.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaton BT, Broder CC, Middleton D, Wang LF. Hendra and Nipah viruses: different and dangerous. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:23–35. 10.1038/nrmicro1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chong HT, Tan CT. Relapsed and late-onset Nipah encephalitis, a report of three cases. Neurological Journal of Southeast Asia. 2003;8:109–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hossain MJ, Gurley ES, Montgomery JM, Bell M, Carroll DS, Hsu VP, et al. Clinical presentation of Nipah virus infection in Bangladesh. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:977–84. 10.1086/529147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paton NI, Leo YS, Zaki SR, Auchus AP, Lee KE, Ling AE, et al. Outbreak of Nipah-virus infection among abattoir workers in Singapore. Lancet. 1999;354:1253–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04379-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chua KB, Goh KJ, Wong KT, Kamarulzaman A, Tan PSK, Ksiazek TG, et al. Fatal encephalitis due to Nipah virus among pig farmers in Malaysia. Lancet. 1999;354:1257–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04299-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurley ES, Montgomery JM, Hossain MJ, Bell M, Azad AK, Islam MR, et al. Person-to-person transmission of Nipah virus in a Bangladeshi community. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1031–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L, Rota PA, Rollin PE, Bellini WJ, et al. Nipah virus–associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:235–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luby SP, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Blum LS, Husain MM, Gurley E, et al. Foodborne transmission of Nipah virus, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1888–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD, Ali MM, Ksiazek TG, Kuzmin I, et al. Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:2082–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Nipah virus outbreak(s) in Bangladesh. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2004;79:168–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research. Bangladesh. Nipah encephalitis outbreak over wide area of western Bangladesh. Health Science Bulletin. 2004;2:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research. Bangladesh. Person to person transmission of Nipah virus during outbreak in Faridpur District. Health Science Bulletin. 2004;2:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luby SP, Hossain MJ, Gurley ES, Ahmed B, Banu S, Khan SU, et al. Recurrent zoonotic transmission of Nipah virus into humans, Bangladesh, 2001–2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1229–35. 10.3201/eid1508.081237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]