Abstract

Previous studies of North American isolates of West Nile virus (WNV) during 1999–2005 suggested that the virus had reached genetic homeostasis in North America. However, genomic sequencing of WNV isolates from Harris County, Texas, during 2002–2009 suggests that this is not the case. Three new genetic groups have been identified in Texas since 2005. Spread of the southwestern US genotype (SW/WN03) from the Arizona/Colorado/northern Mexico region to California, Illinois, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, and the Texas Gulf Coast demonstrates continued evolution of WNV. Thus, WNV continues to evolve in North America, as demonstrated by selection of this new genotype. Continued surveillance of the virus is essential as it continues to evolve in the New World.

Keywords: West Nile virus, viruses, North America, evolution, genotype, genomic sequences, research

West Nile virus (WNV) is a mosquito-borne flavivirus belonging to the Japanese encephalitis serogroup and maintained in an enzootic cycle between mosquitoes (primarily Culex spp.) and birds. Mammals such as horses and humans act as dead-end hosts. Most human infections are asymptomatic; West Nile fever develops in ≈20% of infected patients and neuroinvasive disease develops in <1% (1).

WNV was first isolated in Uganda in 1937 and was generally associated with sporadic outbreaks of mild, febrile illness until the 1990s, when several epidemics of neuroinvasive disease were reported in northern Africa, eastern Europe, and Russia (2–4). In 1999, WNV was first isolated in North America from human and bird samples during an outbreak of encephalitic disease in New York. After this outbreak, WNV rapidly spread across the United States north to Canada and south to the Caribbean region, Mexico, and Central and South America.

By 2002, the original WNV genotype isolated in New York, known as NY99, was displaced by a new genotype, designated the North American (NA) or WN02 genotype (hereafter termed NA/WN02 genotype) (5,6). This genotype is characterized by 13 conserved nt changes, 1 of which results in an amino acid substitution, V159A, in the envelope (E) protein. The NA/WN02 genotype is believed to have become dominant in North America because of its ability to more efficiently disseminate in mosquitoes than the original NY99 virus genotype (6–8).

Beasley et al. (9) first identified the NA/WN02 genotype in Texas in 2002, and further studies showed that this genotype had spread throughout the Upper Texas Gulf Coast and to other regions in the United States (5). Additional studies examined phenotypic changes in WNV isolates from the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region during 2003 and identified co-circulation of small-plaque, temperature-sensitive, mouse-attenuated and large-plaque, non–temperature-sensitive, mouse-virulent strains (10–12). Subsequent studies of the E gene of viruses isolated through 2006 suggested that since the emergence of the NA/WN02 genotype, WNV in North America is either genetically homeostatic (13) or its growth rate is decreasing (14).

We examined genetic variation in selected WNV strains since 2005 from the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region, in particular, Harris County, Texas, USA (Houston metropolitan area). We report the isolation of genetic variants that demonstrate the continuing evolution of WNV in North America. We also show that the southwestern US genotype first identified in Arizona, Colorado, and northern Mexico in 2003 (termed SW/WN03 genotype) has now spread to the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region.

Materials and Methods

Virus Isolates

Virus isolates were obtained from the World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) in Galveston, Texas. All new isolates used in this study were originally made from mosquito pools or the brains of naturally infected birds cultured in Vero cells at UTMB. Each isolate was given a second passage in Vero cells to generate a working stock and stored at –80°C.

Reverse Transcription–PCR

Viral RNA was extracted from 140 μL of infected Vero cell supernatant by using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) per the manufacturer’s directions. Full-genome sequencing was performed by consensus overlapping sequencing of PCR products with primers based on the published sequence of WNV NY-99 flamingo 382–99 (GenBank accession no. AF196835). Reverse transcription–PCR was performed by using the Titan One Tube RT-PCR Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) (primers and PCR conditions are available by request). PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and purified by using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN).

Sequencing and Analysis

Purified PCR products were sequenced in both directions by using the Protein Chemistry or Molecular Genomics Core Laboratories at UTMB. Sequences were edited and assembled by using ContigExpress in the VectorNTI program suite (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Full-length coding sequences were aligned with all published full-length North American WNV isolate sequences available in GenBank (as of November 2010) and isolate WNV IS-98 STD by using MUSCLE in Seaview version 4 (15). The final open reading frame (ORF) alignment contained 244 sequences of 10,299 nt (3,433 aa residues). A second alignment was made by using MUSCLE; this aligment contained 33 sequences from the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region. This alignment contained 11,030 nt and contained the entire ORF and portions of the 3′ and 5′ untranslated region (UTR).

Phylogenetic trees were inferred using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method in the Phylip package (16) and the maximum-likelihood (ML) method by using PhyML (17). MODELTEST, in conjunction with PAUP, was used to identify generalized time reversible + I + Γ4 as the best-fit nucleotide substitution model to be used in phylogenetic analyses (18,19). To assess robustness of the phylogenetic methods used, we used the NJ method and 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The ML method used 100 bootstrap replicates for the entire North American alignment and 1,000 bootstrap replicates for the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region alignment. IS-98 STD was used as outgroup for the entire North American WNV alignment, and NY99 was used as outgroup for the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region alignment.

Recombination Detection and Selection Analysis

Screening for recombination was performed on the first 9,999 nt of the North American WNV ORF alignment by using single-break point analysis on the Datamonkey server (20–22). This screening verified absence of recombination in sequences before running the selection analyses. The first 9,999 nt were selected because of constraints on sequence length by the programs used.

Using the ratio of nonsynonymous (dN) to synonymous (dS) nucleotide substitutions, we examined the genome for sites of positive selection. Positive selection was defined as dN>dS and a p value <1.0. Using the Datamonkey web server (21,22), we used 3 methods to detect site specific nonneutral selection: single-likelihood counting (SLAC), fixed effects likelihood (FEL), and internal FEL (IFEL) (23,24). BioEdit was used to create datasets for the first 9,999 nt of the ORF and for each gene (capsid [C], premembrane [prM], E, nonstructural protein 1 [NS1], NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) for these analyses (25).

Results

Viral Isolates

Viruses used in this study were isolated during 2005–2009 from mosquitoes or dead birds collected in Harris County. There were 111 isolates: 14 from 2005, 11 from 2006, 36 from 2007, one from 2008, and 49 from 2009. The genomic sequences of 17 geotemporally representative isolates were determined and compared with other WNV strains from the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region (Harris, Jefferson, and Montgomery Counties) isolated during 2002–2005 and sequenced in our laboratory (Table 1) (5,10,12).

Table 1. West Nile viruses from the Upper Texas Gulf Coast, USA, used to study genotype evolution, 2002–2009.

| Strain | Source | County | Collection year | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TX2002–1 | Human | Unknown | 2002 | DQ164198 |

| TX2002–2 | Human | Unknown | 2002 | DQ164205 |

| TVP8533 | Human | Jefferson | 2002 | AY218294 |

| Bird 114 | Blue jay | Harris | 2002 | GU827998 |

| Bird1153 | Mourning dove | Harris | 2003 | AY712945 |

| Bird1171 | Great-tailed grackle | Harris | 2003 | AY712946 |

| v4095 | Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito | Harris | 2003 | GU828002 |

| v4380 | Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito | Harris | 2003 | GU828001 |

| Bird1881 | Mourning dove | Jefferson | 2003 | GU828003 |

| Bird1519 | Blue jay | Montgomery | 2003 | GU828004 |

| Bird1576 | Blue jay | Montgomery | 2003 | GU827999 |

| Bird1175 | Blue jay | Harris | 2003 | GU828000 |

| Bird1461 | Blue jay | Harris | 2003 | AY712947 |

| v4369 | Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito | Harris | 2003 | AY712948 |

| Bird3588 | Blue jay | Harris | 2004 | DQ164206 |

| TX5058 | Blue jay | Harris | 2005 | JF415929 |

| M12214 | Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito | Harris | 2005 | JF415915 |

| TX5810 | Common grackle | Harris | 2006 | JF415916 |

| M6019 | Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito | Harris | 2006 | JF415930 |

| TX6276 | Northern mockingbird | Harris | 2006 | JF415916 |

| TX6647 | Blue jay | Harris | 2007 | JF415917 |

| TX6747 | Blue jay | Harris | 2007 | JF415918 |

| M19433 | Aedes albopictus mosquito | Harris | 2007 | JF415919 |

| TX7191 | Blue jay | Harris | 2007 | JF415920 |

| TX7558 | Blue jay | Harris | 2008 | JF415921 |

| M37012 | Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito | Harris | 2009 | JF415922 |

| M37906 | Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito | Harris | 2009 | JF415923 |

| TX7827 | Blue jay | Harris | 2009 | JF415924 |

| M38488 | Ae. albopictus mosquito | Harris | 2009 | JF415925 |

| M20140 | Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito | Harris | 2009 | JF415926 |

| M20141 | Ae. albopictus mosquito | Harris | 2009 | JF415927 |

| M20122 | Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito | Harris | 2009 | JF415928 |

Harris County Isolates, 2005–2009

Nucleotide Changes

The genome of WNV is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA molecule; the NY99 strain contains 11,029 nt. The genome encodes a 5′ UTR (genomic nt 1–96) and a 3′ UTR (genomic nt 10,396–11,029). The UTRs flank a single ORF that encodes 10 proteins; 3 structural proteins (C, prM/M, and E) and 7 nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5).

When compared with NY99, the prototype WNV strain for North America, the 17 WNV isolates we analyzed in this study had 38–60 nt (0.35%–0.54%) differences; most changes were synonymous. Nine of the 13 conserved nt changes characteristic of the NA/WN02 genotype were found in all newly sequenced isolates (Table 2). One 2006 isolate (TX6276), two 2007 isolates (TX6747 and TX7191), and six of seven 2009 isolates (M37012, M37906, M39488, M20140, M20141, and M20122) encoded a C at nt 660 and 6238, which was identical to that in the NY99 strain. Two isolates (M12214 from 2005 and M19433 from 2007) encoded a C at nt 6426, and 2 isolates (TX5810 and M6019, both from 2006) encoded a U at nt 9352, again identical to the NY99 strain. One 2005 isolate (TX5058) contained a 6-nt (nt 10471–10476) deletion in the 3′ UTR, and one 2007 isolate (TX7191) and two 2009 isolates (M37906 and TX7827) contained a 1-nt deletion at nt position 49/50 in the 5′ UTR.

Table 2. Nucleotide sequence changes in West Nile virus NA/WN02 genotype, Upper Texas Gulf Coast, USA*.

| Strain | Year | prM |

E |

NS2A |

NS3 |

NS4B |

NS5 |

3′ UTR |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 660 | 1442 | 2466 | 3774 | 4146 | 4803 | 6138 | 6238 | 6426 | 6996 | 7938 | 9352 | 10851 | ||||||||

| NY99 | 1999 | C | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | C | C | U | C | A | ||||||

| Bird 114 | 2002 | U | C† | U | U | G | U | U | U | U | U | C | U | G | ||||||

| M12214 | 2005 | U | C | U | U | G | U | U | U | · | U | C | U | G | ||||||

| TX5058 | U | C | U | U | G | U | U | U | U | U | C | U | G | |||||||

| TX5810 | 2006 | U | C | U | U | G | U | U | U | U | U | C | · | G | ||||||

| M6019 | U | C | U | U | G | U | U | U | U | U | C | · | G | |||||||

| TX 6276 | · | C | U | U | G | U | U | · | U | U | C | U | G | |||||||

| TX 6647 | 2007 | U | C | U | U | G | U | U | U | U | U | C | U | G | ||||||

| TX6747 | · | C | U | U | G | U | U | · | U | U | C | U | G | |||||||

| M19433 | U | C | U | U | G | U | U | U | · | U | C | U | G | |||||||

| TX7191 | · | C | U | U | G | U | U | · | U | U | C | U | G | |||||||

| TX 7558 | 2008 | U | C | U | U | G | U | U | U | U | U | C | U | G | ||||||

| M 37012 | 2009 | · | C | U | U | G | U | U | · | U | U | C | U | G | ||||||

| M 37906 | · | C | U | U | G | U | U | · | U | U | C | U | G | |||||||

| TX 7827 | U | C | U | U | G | U | U | U | U | U | C | U | G | |||||||

| M 39488 | · | C | U | U | G | U | U | · | U | U | C | U | G | |||||||

| M 20140 | · | C | U | U | G | U | U | · | U | U | C | U | G | |||||||

| M 20141 | · | C | U | U | G | U | U | · | U | U | C | U | G | |||||||

| M20122 | · | C | U | U | G | U | U | · | U | U | C | U | G | |||||||

*PrM, premembrane; E, envelope; NS, nonstructural; UTR, untranslated region. Values indicate nucleotide position within each gene. Dots indicate no change from NY99 isolate. †Encodes for amino acid substitution E-V159A.

Amino Acid Substitutions

Deduced amino acid sequences were compared and substitutions were identified for 41 residues (2 in C, 4 in prM/M, 6 in E, 0 in NS1, 6 in NS2A, 2 in NS2B, 8 in NS3, 2 in NS4A, 4 in NS4B, and 7 in NS5); each isolate contained 3–7 substitutions (Table A1). Eight (C-T109I, E- T70I, E-V159A, E-I460M/L, NS2A-R98G, NS2A-A137V, NS4A-A85T, and NS4B-I240M) of the 41 substitutions were found in >1 isolate. All isolates contained the E-V159A substitution present in the NA/WN02 genotype.

Upper Texas Gulf Coast Region Isolates, 2002–2009

WNV was first detected in the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region in 2002 (9). During 2002–2004, isolates from the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region were divided genetically into 3 groups (groups 1–3) (12) and showed 0.30%–0.40% divergence compared with NY99. Isolates from 2005–2009 (groups 4–6; see below for their definitions) have significantly greater divergence (0.40%–0.70%; p<9.4 × 10–9) from NY99 (Table 3). When compared with isolates from 2002–2004 (groups 1–3), we found that recent Upper Texas Gulf Coast isolates from 2005–2009 (groups 4–6) have nucleotide divergence rates ranging from 0.50% to 0.80%. Because of the high number of synonymous nucleotide mutations, the deduced amino acid sequences of all isolates exhibited a higher level of conservation; divergence rates ranged from 0.10% to 0.30% compared with NY99.

Table 3. Percentage nucleotide and amino acid sequence divergence of West Nile virus isolates, Upper Texas Gulf Coast, USA, 2002–2009*.

| Group† | NY99 | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | Group 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NY99 | 0.1–0.2 | 0.1–0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1–0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2–0.3 | |

| Group 1 | 0.3–0.4 | 0.1–0.3 | 0.1–0.3 | 0.1–0.3 | 0.2–0.3 | 0.2–0.4 | |

| Group 2 | 0.3 | 0.3–0.4 | 0.1–0.2 | 0.2–0.3 | 0.2–0.3 | 0.2–0.3 | |

| Group 3 | 0.3 | 0.1–0.4 | 0.2–0.3 | 0.1–0.3 | 0.2–0.3 | 0.2–0.3 | |

| Group 4 | 0.5–0.6 | 0.5–0.7 | 0.5–0.6 | 0.5–0.6 | 0.2–0.3 | 0.2–0.3 | |

| Group 5 | 0.5–0.7 | 0.5–0.8 | 0.4–0.7 | 0.4–0.7 | 0.7–1.0 | 0.3 | |

| Group 6 | 0.4–0.5 | 0.4–0.6 | 0.4–0.5 | 0.4–0.5 | 0.7–0.8 | 0.6–0.8 |

*Amino acid sequence divergence is shown above the diagonal, and nucleotide sequence divergence is shown in below the diagonal. †Group 1: bird 114 (2002), bird 1171 (2003), bird 1153 (2003); group 2: bird 1519 (2003), v4369 (2003), v4095 (2003), bird 1881 (2003), v4380 (2003); group 3: bird 1576 (2003), bird 1175 (2003), TX2003; group 4: TX6376 (2006), M20141 (2009), M20140 (2009), M37906 (2009), M39488 (2009), M20122 (2009), M37102 (2009); group 5: M12214 (2005), M19433 (2007), TX6647 (2007), TX7558 (2008); group 6: M6019 (2006), TX5810 (2006).

With the exception of conserved nucleotide mutations in the NA/WN02 genotype, there were a few nucleotide changes or deduced amino acid substitutions that were shared by >1 isolate from 2002–2004 and 1 of the newly sequenced isolates from 2005–2009. Nucleotide changes at 11 positions were shared between >1 isolate from 2002–2004 and the newly sequenced isolates from 2005–2009, with only 1 aa substitution, NS4B-I240M, found in >1 isolate from both groups.

Phylogenetic Analysis

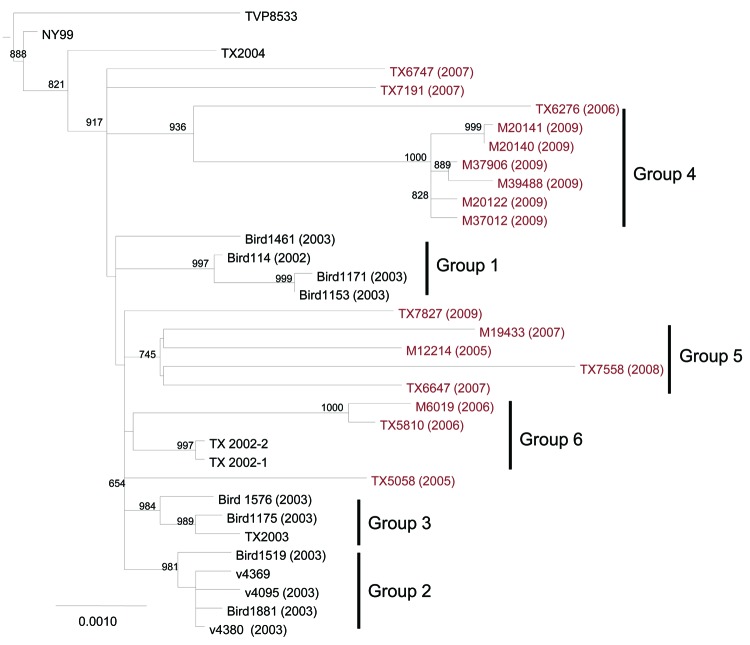

Phylogenetic trees were generated by NJ and ML analyses by using only the polyprotein sequence of 34 isolates: the 17 newly sequenced isolates, 16 published sequences of isolates from the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region, and NY99 (Figure 1). Both methods produced trees with similar topology. In addition to groups 1, 2, and 3 identified in Upper Texas Gulf Coast region isolates obtained in 2002–2003 (12), we identified 3 other phylogenetic groups in this study.

Figure 1.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of Upper Texas Gulf Coast, USA, West Nile virus isolates, 2002–2009. The tree was inferred from open reading frame sequences of 33 Upper Texas Gulf Coast isolates and NY99 by using PhyML (17) and rooted with IS-98 STD. The outgroup has been removed. Bootstrap values are for 1,000 replicates and only values >500 are shown. Groups 1–3 were previously identified by May et al. (12). Red, isolates sequenced in this study. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site.

Group 4 is composed of 6 of 7 isolates from 2009 and 1 isolate from 2006 (TX6276). Group 5 is composed of 4 isolates: 1 from 2005 (M12214), 2 from 2007 (M19433 and TX6647), and 1 from 2008 (TX7558). Group 6 is composed of 2 isolates from 2006 (M6019 and TX5810) and 2 sequenced isolates from 2002. Groups 4 and 5 are supported by high bootstrap values; group 6 has a lower bootstrap value. Within group 4, all 2009 isolates contained an E-I460E substitution. All group 5 isolates contain the amino acid substitution NS4B-A85T, and all isolates in groups 4 and 6 contain the NS4B-I240M substitution. Four isolates did not fall into these 6 groups: TX5058 (2005), TX6747 and TX7191 (2007), and TX7827 (2009).

The TX7828 2009 isolate, which did not fall into group 4 with the other 2009 isolates, is the only 2009 isolate sequenced in this study that was isolated from a bird (blue jay). However, we had only 1 isolate from 2008, and WNV activity was low in Harris County in 2008 (R. Bueno and R. Tesh, unpub. data). This finding may have been caused by Hurricane Ike, which hit the Upper Texas Gulf Coast in September 2008.

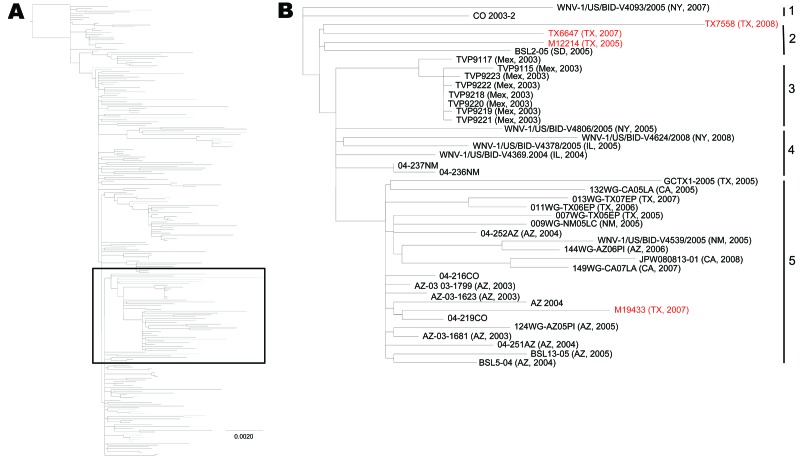

A second phylogenetic analysis was undertaken that used isolates from this study and all published full-length WNV sequences from North America available on GenBank (Figure 2). NJ and ML methods produced trees with similar topology. Within the larger tree, there were analogous groupings of previously and newly sequenced Harris County isolates, as shown in Figure 1. Three of the Harris County groups form distinct clusters of isolates within the NA/WN02 genotype and may represent formation of new genotypes or clusters. Group 1 Harris County isolates (2002–2003) cluster with a grouping of isolates from California from 2003–2008, and group 4 isolates (2006–2009) cluster with several isolates from New York (2008) and 1 isolate from Illinois (2006). Group 5 isolates from Harris County cluster with isolates from the southwestern United States and northern Mexico (called the SW/WN03 genotype because the first isolates were identified in Arizona and Colorado in 2003).

Figure 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree showing all published, full open reading frame North American West Nile virus isolates, 2002–2009 (A), and enlargement showing SW/WN03 genotype (B). Red, isolates sequenced in this study. Scale bar in panel A indicates nucleotide substitutions per site. Numbers on the right in panel B indicate groups.

SW/WN03 Genotype

This genotype is composed of 5 groups on the basis of nucleotide and amino acid sequences and phylogenetic analysis. SW Group 1 is composed of 2 isolates: WNV-1/US/BID-V4093/2007 from New York and CO2003–2 from Colorado. SW Group 2 is composed of 4 isolates, 3 from Texas that were sequenced in this study: M12214 (2005), TX6647 (2007), TX7558 (2008), and BSL2–05 from South Dakota in 2005. SW Group 3 is composed of 6 isolates: 2 from Illinois (WNV-1/US/BID-V4369/2004 and WNV-1/US/BID-V4378/2005), 2 from New York (WNV-1/US/BID-V4806/2005 and WNV-1/US/BID-V4624/2008), and 2 from New Mexico (04–237NM and 04–238NM). SW Group 4 is composed of 8 isolates from Mexico in 2003 (TVP9115, TVP9118–TVP9222). SW Group 5 is the largest and is composed of 22 isolates: 10 from Arizona (2003–2006), 2 from New Mexico (2005), 2 from Colorado (2004), 3 from California (2005, 2007–2008), and 5 from Texas (M19433, which was sequenced in this study, and 4 isolates from west Texas).

Further examination of sequences within the SW/WN03 genotype showed that they share some or all of a signature of 13 nt changes (different from those of the NA/WN02 genotype), including 2 aa substitutions, NS4B-A85T and NS5-K314R (Table A2). Isolates in SW group 1 contain 4 of the 13 changes (nt positions 6238, 6721, 7269, and 9264). SW group 2 isolates contain 5 changes (nt positions 6238, 6721, 8550, 9264, and 9660). SW group 3 isolates have 7 changes (nt positions 1320, 6238, 6721, 8550, 8621, 9264, and 9660). SW group 4 isolates have 6 changes (nt positions 1320, 6238, 6721, 8550, 8621, and 9660). SW group 5 isolates have all 13 nt changes (nt positions 1320, 1974, 3399, 6238, 6721, 6765, 6936, 7269, 8550, 8621, 9264, 9660, and 10062). Isolates in SW groups 1 and 2 contain only 1 (NS4B-A85T) of the 2 aa substitutions, and isolates in SW groups 3, 4, and 5 contain both amino acid substitutions.

Selection Pressures

Recombination analysis using single-break point analysis was performed on the first 3,333 codons of the ORF of the North American WNV alignment to rule out recombination before performing selection pressure analysis. As expected, no evidence of recombination was detected.

Selection pressures on the WNV genome were examined by using 3 methods: SLAC, FEL, and IFEL (Table 4). These methods estimated the ratio of nonsynonymous (dN) to synonymous (dS) amino acid substitutions in 10 datasets representing the first 9,999 nt (3,333 aa residues) of the ORF and each protein (C, prM/E, NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) for the complete North American WNV alignment of 244 genomes. On examination of the ORF, 3 residues were identified for positive selection in >2 of the 3 methods. E-V431I (codon position 721 in ORF) was identified by FEL (p = 0.057) and IFEL (p = 0.072), NS2A-A224V/T (codon position 1367 in ORF) was identified by SLAC (p = 0.087) and FEL (p = 0.096), and NS4A-A85T (codon position 2209 in ORF) was identified by SLAC (p = 0.087), FEL (p = 0.011), and IFEL (p = 0.067). When selection analysis was performed on each gene, only E-V431I was identified for positive selection (FEL, p = 0.059 and IFEL, p = 0.065). An additional residue, NS5-K314R, was also identified for positive selection by FEL (p = 0.042) and IFEL (p = 0.042).

Table 4. Positive and negative selection results for West Nile virus isolates, Upper Texas Gulf Coast, USA, 2002–2009*.

| Protein | Amino acid residues relative to ORF | Length of protein, aa | Overall dN/dS | Single-likelihood ancestor counting† |

|

Fixed effects

likelihood† |

|

Internal fixed effects likelihood† |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive selection | Negative selection | Positive selection | Negative selection | Positive selection | Negative selection | ||||||

| ORF | 1–3,333‡ | 3,333 | 0.110 | 2 | 246 | 8 | 619 | 16 | 25 | ||

| C | 1–123 | 123 | 0.270 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 2 | ||

| prM | 124–290 | 166 | 0.134 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 25 | 1 | 3 | ||

| E | 291–791 | 500 | 0.119 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 72 | 1 | 3 | ||

| NS1 | 792–1143 | 351 | 0.134 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 48 | 4 | 4 | ||

| NS2A | 1144–1374 | 230 | 0.130 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 48 | 1 | 3 | ||

| NS2B | 1375–1505 | 130 | 0.118 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 1 | ||

| NS3 | 1506–2124 | 618 | 0.083 | 0 | 42 | 0 | 101 | 0 | 6 | ||

| NS4A | 2125–2273 | 148 | 0.135 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 22 | 0 | 3 | ||

| NS4B | 2274–2522 | 248 | 0.112 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 49 | 0 | 8 | ||

| NS5 | 2529–3433 | 904 | 0.098 | 0 | 61 | 2 | 148 | 4 | 10 | ||

*ORF, open reading frame; dN, nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions; dS, synonymous nucleotide substitutions; C, capsid; prM, premembrane; E, envelope; NS, nonstructural. †No. sites where p<0.1. ‡Only the first 3,333 aa residues of the ORF were used for these analyses because of program constraints on alignment size.

NS4A-A85T and NS5-K314R are the 2 aa residues that identify the SW/WN03 genotype described. Residue E-V431I is found in a California cluster (California isolates 2003–2008). Substitutions at NS2A-224 (codon position 1367 in ORF) are found in 5 NY99 genotype isolates (A224T) and 4 SW/NA03 genotype isolates (A224V).

Discussion

To date, most genetic and phylogenetic studies of WNV have focused on partial genome sequencing, primarily of the E protein gene. Although studies of the E protein gene are helpful in understanding the evolution of WNV in North America, they provide few phylogenetically informative sites; analysis of genomic sequences is more informative (5,26–32). Similarly, although many studies have examined the evolutionary dynamics of WNV soon after its introduction into North America, only 1 published study has examined isolates since 2006 (33). To our knowledge, none have been published that examined isolates from 2007 or more recently. For these reasons, we examined evolution of WNV by using genomic sequences from 1999–2009. We focused on the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region because of availability of multiple isolates from the same localities each year since the first detection of the virus in Texas in 2002. These isolates were obtained as part of an ongoing surveillance program of WNV activity in Harris County.

The isolates sequenced in this study demonstrate that the NA/WN02 genotype has been maintained during 2002–2009 in Harris County. All 17 isolates sequenced contained 9 of 13 nt changes associated with the NA/WN02 genotype reported by Davis et al. (5), including the amino acid substitution E-V159A. However, since 2005, reversion to the NY99 genotype was seen at 4 nt positions. Nine isolates contained a C at nt positions 660 and 6238, three isolates had a U at nt position 6426, and two isolates had a C at nt position 9352.

Although isolates sequenced in our study display a high degree of similarity, they have major differences. It appears that >3 genetic groups of isolates were co-circulating in Harris County over the study period. Thus, there is continued genetic diversity of WNV over time, at least in the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region, rather than the genetic homeostasis in North America, which was proposed on the basis of using E gene sequences of viruses isolated through 2005 (13). One group, group 4, contains isolates from 2006 and 2009. A second group, group 5, contains isolates from 2005, 2007, and 2008. A third group, group 6, contains isolates from 2006 plus 2 sequenced isolates from 2002. All other 2002–2005 isolates sequenced previously fall into other groups (groups 1–3) (12). Four isolates, TX5058 from 2005, TX6747 and TX7191 from 2007, and TX7827 from 2009, did not fall into any of the 6 groups and may represent single isolates that did not have any advantage and thus became extinct.

When compared with all North American WNV isolates, we found 3 distinctive clusters of isolates within the NA/WN02 genotype. Each cluster contained several isolates from the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region, in addition to other isolates. The first cluster contains group 4 isolates, in addition to four 2008 isolates from New York and one 2006 isolate from Illinois. The second cluster is composed primarily of isolates from California, in addition to group 1 Upper Texas Gulf Coast isolates and 3 additional isolates from Colorado, Connecticut, and Illinois. Group 5 isolates from Harris County cluster with isolates from the southwestern United States (Arizona and Colorado) and from northern Mexico, which were first identified in 2003. This SW/WN03 genotype shares some or all of 13 nt changes, which encode for 2 aa substitutions.

Our data indicate that this genotype is spreading into new areas. It has been identified in California, Illinois, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, and Texas since 2003. Two of these clusters, the California cluster and the cluster we have called the SW/WN03 genotype, are further supported by using selection analysis. This analysis has shown that there is potential for positive selection at E-V431I in the California cluster and at both of the amino acid substitutions (NS4A-A85T, NS5-K314R) in the SW/WN03 genotype. This finding further provides evidence of the potential role of this emerging genotype.

Potential roles of single amino acid substitutions within the WNV genome should also be noted. The single amino acid change, E-V159A, which occurred in the NA/WN02 genotype, was shown to decrease the extrinsic incubation period of the virus in mosquitoes, which enabled that genotype to displace the NY99 genotype (6). Brault et al. (34) reported that the NS3-T249P substitution increased virulence in American crows. The NS3-T249P substitution has undergone positive selection but the E-V159A change has not, yet both cause phenotypic changes. We speculate that positive selection of NS4A-A85T and NS5-K314R induces a phenotypic change in WNV.

Previous studies in our laboratory that focused on the E protein gene concluded that WNV is experiencing a genetic stasis or decrease in its growth rate after establishment of the NA/WN02 genotype (13). However, none of these studies have phylogenetically examined the entire genome of WNV. This study of genomic sequences demonstrates evolution of WNV, at least in the Upper Texas Gulf Coast region, and potential emergence of a new genotype in the southwestern United States (SW/WN03 genotype). Further experiments are needed to investigate potential phenotypic changes that occur in conjunction with the noted genotype changes and to determine if the SW/WN03 genotype will replace the current dominant NA/WN02 genotype.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant AI 067847 and contract HHSN272201000040I/HHSN27200004/DO4 to A.D.T.B. and NIH contracts N01-AI 25489 and N01-AI30027 to R.B.T. A.R.M. is supported by NIH T32 training grant AI 07526.

Biography

Ms McMullen is a predoctoral student at the University of Texas Medical Branch. Her research interests include the pathogenesis and molecular epidemiology of flaviviruses.

Table A1. Deduced amino acid substitutions for West Nile virus isolates, Upper Texas Gulf Coast, USA*.

| Gene | Position | 1999 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NY99 | M12214 | TX5058 | TX5810 | M6019 | TX6276 | TX6647 | TX6747 | M19433 | TX7191 | TX7558 | M37012 | M37906 | TX7827 | M38488 | M20140 | M20141 | M20122 | |||||||

| C |

39* | D | · | · | · | N | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | |||||

| 109 |

T |

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

I |

I |

·

|

|

| PrM/M |

88 | R | · | · | · | K | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | |||||

| 122 | V | · | · | · | · | · | I | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 140 | V | · | · | · | · | · | · | I | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 156 |

V |

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

I |

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

| E |

49 | E | · | · | · | · | K | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | |||||

| 70 | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | I | · | I | · | · | · | ||||||

| 159 | V | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | ||||||

| 431 | V | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | F | ||||||

| 460 | I | · | · | · | · | M | · | · | · | · | · | L | L | · | L | L | L | L | ||||||

| 475 |

N |

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

S |

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

| NS2A |

90 | M | · | · | · | · | · | V | · | · | · | · | · | · | V | · | · | · | · | |||||

| 98 | R | · | · | G | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 118 | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | H | ||||||

| 124 | I | V | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 137 | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | V | V | · | ||||||

| 224 |

A |

|

V |

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

| NS2B |

41 | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | V | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | |||||

| 99 |

M |

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

T |

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

| NS3 |

106 | V | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | |||||

| 160 | S | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 162 | I | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | M | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 213 | I | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | M | · | · | · | ||||||

| 355 | Y | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | H | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 365 | S | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | |||||||

| 486 | F | · | L | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 562 |

R |

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

K |

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

| NS4A |

65 | M | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | |||||

| 85 |

A |

|

T |

·

|

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

T |

·

|

T |

·

|

|

T |

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

| NS4B |

33 | L | · | · | · | F | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | |||||

| 116 | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 176 | I | · | · | · | · | V | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 240 |

I |

|

·

|

·

|

|

M |

M |

M |

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

·

|

|

·

|

|

M |

M |

·

|

M |

M |

M |

M |

|

| NS5 | 21 | K | · | · | · | · | · | R | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | |||||

| 91 | M | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | V | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 314 | K | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | R | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 395 | M | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | I | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 422 | R | · | K | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 640 | L | · | · | P | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 661 | S | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

| 860 | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | ||||||

*C, capsid; PrM/M, premembrane/membrane; E, envelope, NS nonstructural. Dot indicates no change from NY99 isolate.

Table A2. Genotype nucleotide changes in SW/WN03 isolate of West Nile virus, Upper Texas Gulf Coast, USA*.

| Strain |

State |

Year |

Group |

E |

|

NS1 |

|

NS3 |

|

NS4A |

|

NS4B |

|

NS5 |

|

3′ UTR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1320 |

1974 |

3399 |

6238 |

6721† |

6765 |

6936 |

7269 |

8550 |

8621‡ |

9264 |

9660 |

10062 |

||||||||||

| NY99 | NY | 1999 | A | C | U | C | G | U | U | U | C | A | U | C | U | |||||||

| CO 2003–2 | CO | 2003 | 1 | · | · | · | U§ | A | · | · | C | · | · | C | · | · | ||||||

| HM488201 | NY | 2007 | · | · | · | U | A | · | · | C | · | · | C | · | · | |||||||

| M12214 | TX | 2005 | 2 | · | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | · | C | U | · | ||||||

| BSL2–05 | SD | 2005 | · | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | · | C | U | · | |||||||

| TX 6647 | TX | 2007 | · | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | · | C | U | · | |||||||

| TX 7558 | TX | 2008 | · | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | · | C | U | · | |||||||

| HM488191 | IL | 2004 | 3 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | C | U | · | ||||||

| 04–237NM | NM | 2004 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | C | U | · | |||||||

| 04–236NM | NM | 2004 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | C | U | · | |||||||

| HM488198 | IL | 2005 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | C | U | · | |||||||

| HM756675 | NY | 2005 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | C | U | · | |||||||

| HM488239 | NY | 2008 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | C | U | · | |||||||

| TVP9117 | MEX | 2003 | 4 | G | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | U | G | · | U | · | ||||||

| TVP9223 | MEX | 2003 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | · | U | · | |||||||

| TVP9115 | MEX | 2003 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | · | U | · | |||||||

| TVP9222 | MEX | 2003 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | · | U | · | |||||||

| TVP9218 | MEX | 2003 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | · | U | · | |||||||

| TVP9220 | MEX | 2003 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | · | U | · | |||||||

| TVP9219 | MEX | 2003 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | · | U | · | |||||||

| TVP9221 | MEX | 2003 | G | · | · | U | A | · | · | · | U | G | · | U | · | |||||||

| AZ-03–1623 | AZ | 2003 | 5 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | ||||||

| AZ-03 03–1799 | AZ | 2003 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| AZ-03–1681 | AZ | 2003 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| BSL5–04 | AZ | 2004 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| 04–252AZ | AZ | 2004 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| 04–251AZ | AZ | 2004 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| AZ2004 | AZ | 2004 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| 04–216CO | CO | 2004 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| 04–219CO | CO | 2004 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| BSL13–05 | AZ | 2005 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| 142WG-AZ05PI | AZ | 2005 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| 132WG-CA05LA | CA | 2005 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | · | C | |||||||

| HM756677 | NM | 2005 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| 009WG-NM05LC | NM | 2005 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| GCTX1–2005 | TX | 2005 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | · | · | C | |||||||

| 007WG-TX05EP | TX | 2005 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| 144WG-AZ06PI | AZ | 2006 | G | U | C | U | A | C | · | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| 011WG-TX06EP | TX | 2006 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| 194WG-CA07LA | CA | 2007 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| 013WG-TX07EP | TX | 2007 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| M19433 | TX | 2007 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

| JPW080814–01 | CA | 2008 | G | U | C | U | A | C | C | C | U | G | C | U | C | |||||||

*E, envelope; NS, nonstructural; UTR, untranslated region; NY, New York; CO, Colorado; TX, Texas; SD, South Dakota; IL, Illinois, NM, New Mexico; MEX, Mexico, AZ, Arizona; CA, California. Dots indicate no change from NY99 isolate. Isolates in boldface were sequenced in this study. †NS4A-A85T. ‡NS5-K314R. §Nucleotide changes compared with NY99 isolate.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: McMullen AR, May FJ, Li L, Guzman H, Bueno R Jr, Dennett JA, et al. Evolution of new genotype of West Nile virus in North America. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2011 May [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1705.101707

References

- 1.Hayes EB, Gubler DJ. West Nile virus: epidemiology and clinical features of an emerging epidemic in the United States. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:181–94. 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Guenno B, Bougermouh A, Azzam T, Bouakaz R. West Nile: a deadly virus? Lancet. 1996;348:1315. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)65799-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lvov DK, Butenko AM, Gromashevsky VL, Larichev VP, Gaidamovich SY, Vyshemirsky OI, et al. Isolation of two strains of West Nile virus during an outbreak in southern Russia, 1999. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:373–6. 10.3201/eid0604.000408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai TF, Popovici F, Cernescu C, Campbell GL, Nedelcu NI. West Nile encephalitis epidemic in southeastern Romania. Lancet. 1998;352:767–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03538-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis CT, Ebel GD, Lanciotti RS, Brault AC, Guzman H, Siirin M, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of North American West Nile virus isolates, 2001–2004: evidence for the emergence of a dominant genotype. Virology. 2005;342:252–65. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebel GD, Carricaburu J, Young D, Bernard KA, Kramer LD. Genetic and phenotypic variation of West Nile virus in New York, 2000–2003. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moudy RM, Meola MA, Morin LL, Ebel GD, Kramer LD. A newly emergent genotype of West Nile virus is transmitted earlier and more efficiently by Culex mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:365–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Klingler KA, Galbraith SE, Barrett ADT, Higgs S. Comparison of oral infectious dose of West Nile virus isolates representing three distinct genotypes in Culex quinquefasciatus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:951–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beasley DW, Davis CT, Guzman H, Vanlandingham DL, Travassos da Rosa AP, Parsons RE, et al. Limited evolution of West Nile virus has occurred during its southwesterly spread in the United States. Virology. 2003;309:190–5. 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00150-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis CT, Beasley DW, Guzman H, Siirin M, Parsons RE, Tesh RB, et al. Emergence of attenuated West Nile virus variants in Texas, 2003. Virology. 2004;330:342–50. 10.1016/j.virol.2004.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis CT, Galbraith SE, Zhang S, Whiteman MC, Li L, Kinney RM, et al. A combination of naturally occurring mutations in North American West Nile virus nonstructural protein genes and in the 3′ untranslated region alters virus phenotype. J Virol. 2007;81:6111–6. 10.1128/JVI.02387-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.May FJ, Li L, Davis CT, Galbraith SE, Barrett ADT. Multiple pathways to the attenuation of West Nile virus in south-east Texas in 2003. Virology. 2010;405:8–14. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis CT, Li L, May FJ, Bueno R Jr, Dennett JA, Bala AA, et al. Genetic stasis of dominant West Nile virus genotype, Houston, Texas. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:601–4. 10.3201/eid1304.061473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snapinn KW, Holmes EC, Young DS, Bernard KA, Kramer LD, Ebel GD. Declining growth rate of West Nile virus in North America. J Virol. 2007;81:2531–4. 10.1128/JVI.02169-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O. SeaView Version 4: A multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:221–4. 10.1093/molbev/msp259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP–Phylogeny Inference Package (Version 3.2). Cladistics. 1989;5:164–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. 10.1080/10635150390235520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–8. 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swofford DL. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (and other methods). Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Posada D, Gravenor MB, Woelk CH, Frost SD. Automated phylogenetic detection of recombination using a genetic algorithm. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1891–901. 10.1093/molbev/msl051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delport W, Poon AFY, Frost SD, Kosakovsky Pond SL. Datamonkey 2010: a suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2455–7. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pond SLK, Frost SDW. Datamonkey: rapid detection of selective pressure on individual sites of codon alignments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2531–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Frost SD. Not so different after all: a comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1208–22. 10.1093/molbev/msi105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poon AF, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Bennett P, Richman DD, Leigh Brown AJ, Frost SDW. Adaptation to human populations is revealed by within-host polymorphisms in HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e45. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series. 1999;41:95–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grinev A, Daniel S, Stramer S, Rossmann S, Caglioti S, Rios M. Genetic variability of West Nile virus in US blood donors, 2002–2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:436–44. 10.3201/eid1403.070463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herring BL, Bernardin F, Caglioti S, Stramer S, Tobler L, Andrews W, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of WNV in North American blood donors during the 2003–2004 epidemic seasons. Virology. 2007;363:220–8. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deardorff E, Estrada-Franco J, Brault AC, Navarro-Lopez R, Campomanes-Cortes A, Paz-Ramirez P, et al. Introductions of West Nile virus strains to Mexico. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:314–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang Y, Liu B, Hapip CA, Xu D, Fang CT. Genetic analysis of West Nile virus isolates from US blood donors during 2002–2005. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:292–7. 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanciotti RS, Ebel GD, Deubel V, Kerst AJ, Murri S, Meyer R, et al. Complete genome sequences and phylogenetic analysis of West Nile virus strains isolated from the United States, Europe, and the Middle East. Virology. 2002;298:96–105. 10.1006/viro.2002.1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertolotti L, Kitron U, Goldberg TL. Diversity and evolution of West Nile virus in Illinois and the United States, 2002–2005. Virology. 2007;360:143–9. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertolotti L, Kitron UD, Walker ED, Ruiz MO, Brawn JD, Loss SR, et al. Fine-scale genetic variation and evolution of West Nile virus in a transmission “hot spot” in suburban Chicago, USA. Virology. 2008;374:381–9. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amore G, Bertolotti L, Hamer GL, Kitron UD, Walker ED, Ruiz MO, et al. Multi-year evolutionary dynamics of West Nile virus in suburban Chicago, USA, 2005–2007. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:1871–8. 10.1098/rstb.2010.0054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brault AC, Huang CY, Langevin SA, Kinney RM, Bowen RA, Ramey WN, et al. A single positively selected West Nile viral mutation confers increased virogenesis in American crows. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1162–6. 10.1038/ng2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]