Abstract

Mounting evidence suggests that the blueprint of chronic renal disease is established during early development by environmental cues that dictate alterations in differentiation programming. Here we show that aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), a lig-and-activated basic helix-loop-helix-PAS homology domain transcription factor, disrupts murine renal differentiation by interfering with Wilms tumor suppressor gene (WT1) signaling in the developing kidney. Embryonic kidneys of C57BL/6J Ahr−/− mice at gestation d (GD) 14 showed reduced condensation in the nephrogenic zone and decreased numbers of differentiated structures compared with wild-type mice. These deficits correlated with increased expression of the (+) 17aa Wt1 splice variant, decreased mRNA levels of Igf-1 rec., Wnt-4 and E-cadherin, and reduced levels of 52 kDa WT1 protein. AHR knockdown in wild-type embryonic kidney cells mimicked these alterations with notable increases in (+) 17aa Wt1 mRNA, reduced levels of 52 kDa WT1 protein, and increased (+) 17aa 40-kDa protein. AHR downregulation also reduced Igf-1 rec., Wnt-4, secreted frizzled receptor binding protein-1 (sfrbp-1) and E-cadherin mRNAs. In the case of Igf-1 rec. and Wnt-4, genetic disruption was fully reversed upon restoration of cellular Wt1 protein levels, confirming that functional interactions between AHR and Wt1 represent a likely molecular target for renal developmental interference.

INTRODUCTION

The fetal basis of adult renal disease in humans first was suggested by Barker and colleagues in studies showing that intrauterine growth restriction has a negative influence on the development of the cardiovascular system, and favors the occurrence of hypertension, insulin resistance, hypercholesterolemia and hyperuricemia later in life (1). These findings have been confirmed in experimental animal models of human disease (2,3), indicating that highly conserved signaling pathways exist that control differentiation programming through interaction with environmental cues that define complex genetic interactions at the cellular level. The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH)-PAS superfamily is a highly conserved group of proteins involved in mammalian development and the adaptive response to environmental stress (4). AHR (aryl hydrocarbon receptor) is the only member of the superfamily that is conditionally regulated by ligand binding to the PAS domain. In cultured metanephric kidneys, sustained activation of AHR by exogenous ligands is followed by proteasomal degradation of the receptor and inhibition of epithelialization and nephrogenesis (5). An essential role of AHR in spatiotemporal regulation of metanephric development is suggested by the notable deficits in mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) seen in cultured metanephric kidneys isolated from Ahr−/− mice. The developmental functions of Ahr may be mediated by physiological ligands generated by aspartate aminotransferase, an enzyme that is highly enriched in kidney (6).

WT1 has long been recognized as a critical regulator of nephrogenesis (7). Wt1 encodes a 52 kDa zinc finger transcription factor involved in renal and gonad development, with exons 1–6 encoding domains involved in transcriptional regulation, dimerization and RNA recognition and exons 7–10 encoding the four zinc fingers within the DNA-binding domain. Multiple protein isoforms are synthesized due to: (a) alternative splicing regions corresponding to the whole of exon 5 (17 amino acids) and to the three last codons of exon 9 (KTS); (b) a site of RNA editing at codon 281 in exon 6 where a C to T transition produces a leucine to proline substitution; (c) a non-AUG initiation codon resulting in Wt1 proteins with a higher molecular weight; and (d) an internal AUG resulting in Wt1 proteins with a lower molecular weight of approximately 40 kDa (8). In the kidney, WT1 mRNA species exhibit combinatorial patterns that primarily include variants resulting from exon 5 splicing (+17 and −17 amino acids), or +KTS and −KTS alternative splice variants from splicing of exon 9. Biochemical and genetic evidence indicates that different Wt1 isoforms support different cellular functions, with ±KTS-regulating Wt-1 DNA binding specificity (8). Changes in exon 5 splice variants also are associated with deficits in renal differentiation (9). Addition of 17 amino acids in exon 5 creates an mRNA isoform that regulates transactivation (10). N-terminal residues 1–182 encode a dimerization region implicated in the regulatory mechanism exerted by dominant negative mutants (11). The (−) KTS behaves as a transcription factor that regulates genes expressed during kidney development in vitro, including Igf-2, Pdgfα, Egfr, Pax-2 and Wt1 itself, while the (+) KTS isoform regulates the splicing machinery of mammalian cells (12). Hammes (13) generated mouse strains that specifically lack the (−) KTS or (+) KTS Wt1 splice variants and showed that the (+) KTS isoform is important for maintenance of podocyte function. In fact, mice lacking the (+) KTS Wt1 variant are characterized by development of renal insufficiency with focal and segmental glomerular sclerosis and male-to-female sex reversal, similar to the human Frasier syndrome (14). Only preliminary results have been obtained regarding functional consequences of the presence or absence of the 17 amino acids encoded by exon 5 and containing a protein:protein interaction (15). At the cellular level, the balance between (±) exon 5 isoforms may be involved in regulation of proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis and prevention of tumor formation (16).

A functional link between AHR and WT1 was suggested by the previous finding that activation of AHR by benzo(a)pyrene, a hydrocarbon ligand of the receptor, induces the (−) KTS Wt1 isoform in cultured metanephric kidneys of Ahr+/+ but not Ahr−/− mice (5). Evidence is presented that AHR functions as a regulator of renal cell differentiation through mechanisms that involve changes in the relative abundance of WT1 splice variants and deregulation of downstream WT-1 signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals/Metanephros Harvest

C57bL/6J wild type or Ahr knockout mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, MN, USA) and placed under standard housing conditions. The care, breeding and handling of animals were conducted in accord with NIH guidelines. At d 14 of gestation, mouse embryos were resected from C57bL/6J wild-type or Ahr knockout pregnant dams; the developing kidneys were harvested and processed for further analysis in vivo as described before (5).

Morphometric Analysis

Embryonic kidneys were fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slides (5-μm sections) were examined by bright-field light microscopy. Computer-assisted analysis was performed on six to eight histological sections from embryonic developing kidneys of wild-type or Ahr−/− mice, respectively. Measurements were taken from serial sections of embryonic kidneys from three or more dams. The values shown represent the composite of serial sections with variance expressed as the difference between values for each kidney per mouse strain. Images were captured using an Olympus Vanox research microscope equipped with a 3-CCD Camera (Model Del-750) and analyzed with the “NIH-Image” v1.60 public domain program developed at the National Institutes of Health and available at http://zippy.nimh.nih.gov/pub/nih-image. The high quality of the sections used allowed for direct visualization and quantification of intermediate stages and also glomerulotubular structures of developing kidney throughout the entire length of the section.

Cell Cultures/siRNA Transfection

The mK3 and mK4 cells were kindly provided by Stephen Potter (Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA). Cells were seeded in 12-well plates and cultured Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. At approximately 50% confluence, siRNA duplexes were transfected into the cells with siPORT Lipid (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). 6 μL of a 20 μmol/Lstock solution of siRNA targets was transfected in each well to achieve a final concentration of 120 nmol/L. Total protein was harvested 36 to 48 h after transfection using M-PE Extraction Reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). The double stranded RNA (siRNA) used to target Ahr was: Sense: 5′-GGGCCAAGAG CUUCUUUGAtt-3′; and Antisense: 5′-UCAAAGAAGCUCUUGGCCCtc-3′. A silencing scrambled siRNA negative control (Ambion) was used in all experiments. In rescue experiments, mK4 cells were transfected with 2 μg of CB6+-Wt1 (−/ −) plasmid encoding for 52 kDa Wt1 protein or empty vector 24 h after transfection with siRNA. After 48 h, protein and RNA were harvested for further analysis.

Protein Harvesting

Metanephroi were washed with PBS and homogenized in T-PER Tissue Extraction Reagent (Pierce Biotechnology). Total protein or diffractionated proteins (cytoplasmic and nuclear) were harvested using M-PER and NE-PER Extraction Reagents (Pierce Biotechnology), respectively, as described by the manufacturer. Protein concentration was measured by the method of Bradford. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were separated using NE-PER (Pierce Biotechnology) as per manufacturer’s instructions with the addition of HALT protease inhibitor (Pierce Biotechnology). Protein concentrations were determined by Brad-ford using albumin standards created with the CERI and NER reagents.

Western Analysis

Protein samples were boiled for 2 min and applied to 4% to 12 % NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Twenty micrograms of protein were loaded onto a 4% to 12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and run in MOPS buffer under reduced conditions.

After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to PDVF membranes and probed with three different Wt1 antibodies (Wt1 N-[180]: sc-846, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA]; C19 [Santa Cruz Biotechnology] and H2-F6 [Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA] or Ahr antibody [BioMOL Research Laboratories Inc., Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA]). Signals were visualized with horseradish per-oxidase conjugated secondary antibody. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and probed for the nuclear transcription factor Oct1 (SC-232) or the cytoplasmic protein HSP90α/β (SC-13119) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Signals were visualized with a corresponding secondary antibody and chemilumenescence detection using ECL+ (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Membranes were developed using the enhanced chemiluminescent (SuperSignal West Dura) Western blotting system (Pierce Biotechnology). Three to five independent experiments were performed in all instances.

RNA Isolation

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA) according to manufacturer’s specifications.

RT-PCR

Reverse transcription was performed with MuLV Reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and OligoDTs according to manufacturer’s specifications. PCR was performed using DNA Taq Polymerase (Applied Biosystems) using specific primers and PCR thermoprofile sets for each gene. Primer sequences and PCR conditions for Cyp1a1 and E-cadherin were as published by Reiners et al. (17) and Hosono et al. (18). Primers used to detect specific sequences in the 5′ UTR region of Wt1 upstream of both AUGs are listed in Table 1. Owing to the high G-C rich content of the Wt1 5′ UTR region, PCR was performed using Advantage-GC 2 Polymerase (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s specifications. PCR reaction was carried out at 94°C for 3 min, 68°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 3 min for 35 cycles and the reaction incubated at 72°C for 5 min.

Table 1.

PCR primers.

| Gene | Forward primer 5′-3′ | Reverse primer 5′-3′ | Size | Annealing temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18S | CGTCTGCCCTATCAACTTTCG | GCCTGCTGCCTTCCTTGG | 130 bp | 55ºC |

| Cyp1a1 | TCGTGTCAGTAGCCAATGTC | GCATCCAGGGAAGAGTTAGG | 178 bp | 55ºC |

| E-cadherin | CGACCCTGCCTCTGAATCC | CTTTGTTTCTTTGTCCCTGTTGG | 175 bp | 55ºC |

| Epidermal growth factor receptor | GAGGAGGAGAGGAGAACTG | GGTGGGCAGGTGTCTTTG | 196 bp | 55ºC |

| Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor | GTCCCTCAGGCTTCATCC | GAGCAGAAGTCACCGAATC | 126 bp | 55ºC |

| Insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor | AGTATGTGAACGGCTCTG | TCTGTGATTGTCTGGATAGG | 184 bp | 55ºC |

| Lim homeobox protein 1 | ACCTAAGCAACAACTACAATC | AACACGGGAGTAGAAAGC | 167 bp | 55ºC |

| Paired box gene 2 | AGGTTTACATCTGGTCTGG | TAGGAAGGACGCTCAAAG | 162 bp | 55ºC |

| Retinoic acid receptor α | CCCAGAAGACTAAAGTTGAC | TGGCAGGTAGTTGTGATG | 152 bp | 55ºC |

| Secreted frizzled-related sequence protein 1 | GCAGTTCTTCGGCTTCTA | ATGGAGGACACACGGTTG | 134 bp | 55ºC |

| Syndecan 1 | GAGAACAAGACTTCACCTTTG | GCACTTCCTTCCTGTCC | 139 bp | 55ºC |

| Taurine transporter | CATCCATCGTCATTGTGTC | AAGTTGGCAGTGCTAAGG | 196 bp | 55ºC |

| Wingless-related MMTV-integration site 4 | GTAGCCTTCTCACAGTCCTTTG | GGTACAGCACGCCAGCAC | 188 bp | 55ºC |

| Wilms tumor suppressor 17aa | CCTGAGGACGCCCTACAGC | CTGTGCCGTGGTTGCTCTGC | 161 bp | 55ºC |

| Wilms tumor suppressor +KTS | AGCTCAAAAGACACCAAAGGAG | GAAGGGCTTTTCACTTGTTTTAC | 137 bp | 55ºC |

| Wilms tumor suppressor −KTS | AGCTCAAAAGACACCAAAGGAG | GGGCTTTTCACCTGTATGAG | 125 bp | 55ºC |

Real-Time PCR Amplification

Reverse transcription of RNA was carried out using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA). Real-time PCR amplification was performed using the iCycler Detection System (BIO-RAD). For each run, 25 μL of 2 × SYBR Supermix (BIO-RAD) and 300 nmol/L for both forward and reverse primers in a total volume of 50 μL were mixed. The thermal cycling conditions comprised an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, 50 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 65°C for 1 min. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Primer sequences for mice Wnt-4, Igf-1 rec. and sfrp-1 are also listed in Table 1. 18S rRNA was used as an internal control for all measurements. Quantification was performed using comparative (ΔCT) method as described by Peinnequin et al. (19).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by LSD post hoc tests at the P < 0.05 level.

RESULTS

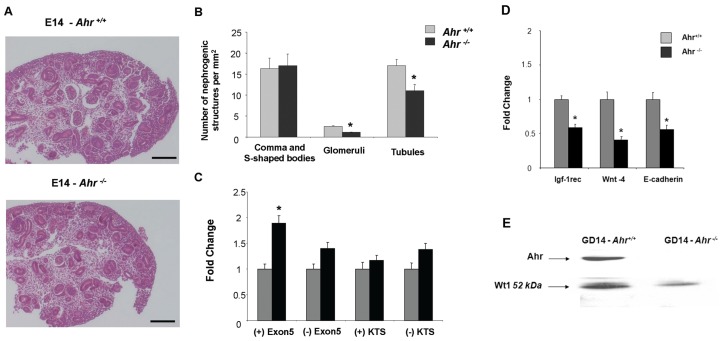

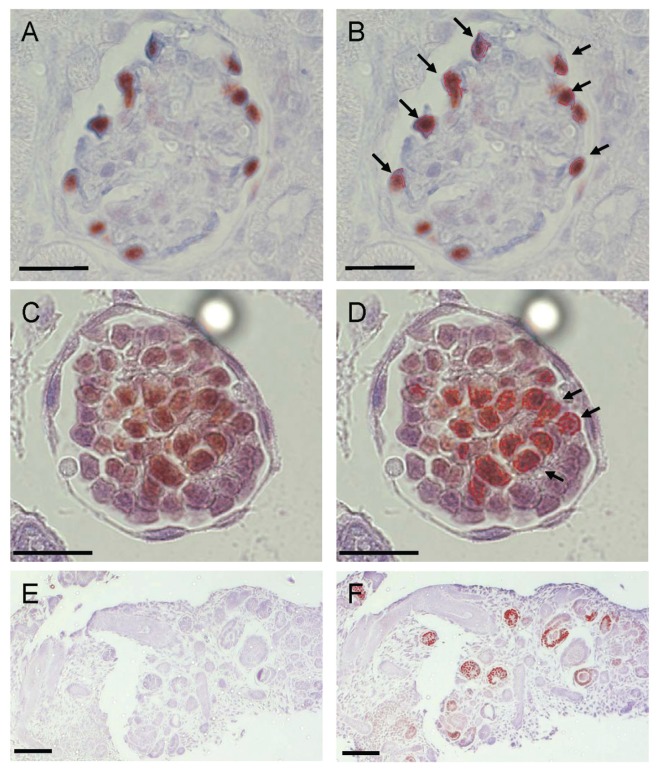

To examine the role of AHR during nephrogenesis in vivo, renal cell differentiation was monitored in GD:14 embryos of Ahr+/+ and Ahr−/− mice. Renal blastema in the proliferation zone was less condensed in developing kidneys from Ahr−/− embryos (Figure 1A). Morphometric analysis revealed decreased numbers of glomeruli and tubuloepithelial structures in Ahr −/− mice after normalization by area, with equal numbers of comma and S-shaped bodies (Figure 1B). The embryonic kidneys of Ahr−/− mice expressed higher levels of the (+) 17aa Wt1 splice variant (Figure 1C), a change that correlated with lower levels of Igf-1 rec., Wnt-4 and E-cadherin mRNAs and reduced levels of 52 kDa Wt1 protein (Figures 1D, E). Immunological detection experiments established colocalization of the Wt1 and Ahr proteins in developing metanephric glomeruli, as well as in the adult glomeruli (Figures 2A–F).

Figure 1.

Deficits in renal differentiation and Wt1 expression in embryonic kidneys from Ahr−/− mice. Kidneys were harvested from mouse embryos at GD:14 and fixed in situ for morphological examination as described. (A) Renal blastema in the proliferation zone was less condensed in developing kidneys from Ahr knockout embryos relative to wild-type counterparts (compare panels 1 and 2). Magnification in both panels was 289X. Similar findings were made in 10 mice from multiple litters. (B) Morphometric analyses of kidney sections showed decreased numbers of glomeruli and tubulo-epithelial structures (P < 0.05), despite equal numbers of comma and S-shaped bodies in Ahr knockout compared with wild-type mice. Data are presented as the average number of structures ± SD for multiple sections. Measurements were taken from serial sections from 6 to 8 embryonic kidneys isolated from three or more dams. The values shown represent the composite of serial sections with variance expressed as the difference between values for each kidney per mouse strain. (C) PCR analyses of Wt1 splice variants in embryonic kidneys of Ahr −/− compared with wild-type mice. (D) PCR analysis of various markers of renal cell differentiation (Igf-1 rec, Wnt4 and E-cadherin) in embryonic kidneys from Ahr−/− and Ahr+/+ mice. (E) Western blot analysis of Ahr and Wt1 in kidneys of Ahr−/− and Ahr+/+ mice. One representative experiment out of two is shown. Equal protein loadings were confirmed based on the signal obtained with the same antibody for a nonspecific band (80 kDa).

Figure 2.

Ahr and Wt1 colocalize in the developing and adult kidney. Dual immunohisto-chemical analyses of Ahr and Wt1 proteins visualized using 3, 3′, 5, 5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) and NovaRED, respectively (Vector Laboratories Burlingame, CA, USA). Panels A and C are representative images taken of glomeruli from adult C57BL/6J mouse kidneys or GD 11 cultured metanephros cross sections. In panel B, maximal Ahr signal (blue color) was set to threshold in serial sections processed for Ahr alone using Zeiss Axiovision Rel 4.3 image analysis. The thresholded filter was applied to dual-stained sections resulting in a red-outlined area of positive maximal Ahr signal. Ahr-Wt1 colocalization was defined by a positive nuclear Wt1 signal in proximity to the outlined maximal Ahr signal, as denoted by arrows. Because of the diffuse Ahr signal throughout metanephric glomerular cells, in panel D, Ahr-Wt1 colocalization was determined by thresholding for color resulting from both Ahr and Wt1 signals and compared with control serial sections stained for each antibody alone. The analysis showed Ahr-Wt1 colocalization outlined in red and only 10% errant signal detected in control sections. Panels E and F are serial cross sections of C57BL/6J GD 11 cultured metanephros analyzed for Ahr alone or Ahr-WT1 colocalization as described above. In panels A-D the scale represents 25 μm, while in panels E and F the scale represents 100 μm.

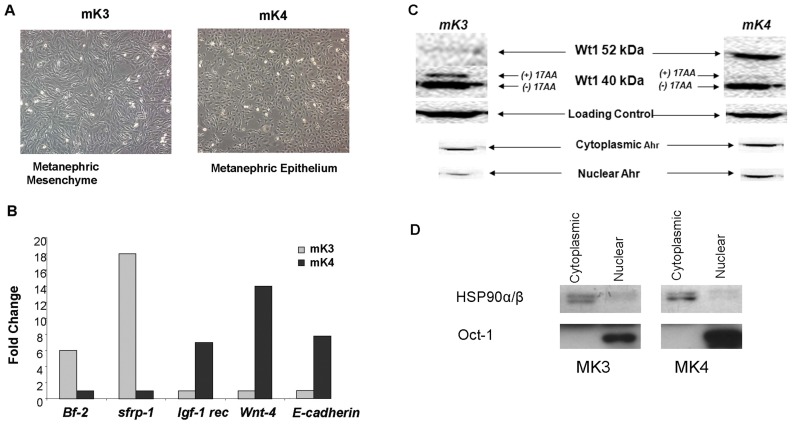

A gene knockdown approach was employed to examine the role of AHR in genetic programming and MET in embryonic mK3 and mK4 cell lines, models of early uninduced and later-induced murine metanephric mesenchyme, respectively (20). The mK3 cells exhibited spindle-shaped morphologies with irregular cytoplasmic projections, while mK4 cells exhibited cobblestone morphologies and polygonal shapes (Figure 3A). The degree of cellular differentiation in these lines was monitored based on the expression of genes involved in MET. mK4 cells expressed higher levels of Igf-1 rec., Wnt-4 and E-cadherin mRNAs compared with mK3 cells, while transcript levels for Bf-2 and secreted sFrp-1 were higher in mK3 cells (Figure 3B). The pattern of Wt1 protein expression in these cell lines was striking, with the 52 kDa Wt1 protein isoform detected predominantly in mK4 cells; but higher levels of the two lower 40 kDa isoforms corresponding to the (±) exon 5 variants predominantly the (+) 17 AA 40 kDa were noted in mK3 cells (Figure 3C). The specificity of the Wt1 40 kDa signal in Western blot experiments was verified using a H2-F6 Wt1 antibody that selectively recognizes the larger 52 and 62 kDa isoforms of Wt1 protein. The mK4 cells expressed higher cytoplasmic and nuclear levels of Ahr protein than mK3 cells (see Figure 3C), suggesting that expression of both Ahr and Wt1 proteins correlates with the degree of renal cell differentiation. The purity of fractions was confirmed using HSP90α/β and Oct1 as markers of cytoplasmic and nuclear identity, respectively (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Differentiation and epithelialization status in mK3 and mK4 embryonic kidney cell lines. The expression of renal cell differentiation and epithelialization marker genes was examined by PCR or Western blot analysis. (A) The mK3 cells exhibited a spindle-shape morphology with irregular cytoplasmic projections, while mK4 cells displayed polygonal shapes indicative of later stage differentiation during the course of MET. (B) Real time or RT-PCR analyses showed that mK4 cells expressed higher level of E-cadherin, Wnt-4 and Igf-1 rec. compared with mK3 cells. In contrast Bf-2 and secreted frizzled receptor binding protein-1 (sfrp-1) transcripts were higher in mK3 cells. Similar results were seen in three different experiments. (C) Western blot analysis showed that mK4 cells possess higher levels of Ahr and 52 kDa Wt1 protein compared with mK3 cells. Similar results were seen in four separate experiments. (D) The quality of cellular fractions was confirmed by Western blotting using HSP90α/β and Oct1 as markers of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins, respectively. Images shown are representative of triplicate samples from multiple gels. Equal protein loadings were confirmed based on the signal obtained with the same antibody for a nonspecific band (80 kDa). Notably, embryonic kidney cell lines also expressed 40 kDa variants of ± exon 5. The abundance of (+) 17 AA variant inversely correlated with the degree of renal cell differentiation as shown by decreases in Bf-2 and sfrp-1 mRNAs and increases in Igf-1 rec, Wnt-4 and E-cadherin mRNAs.

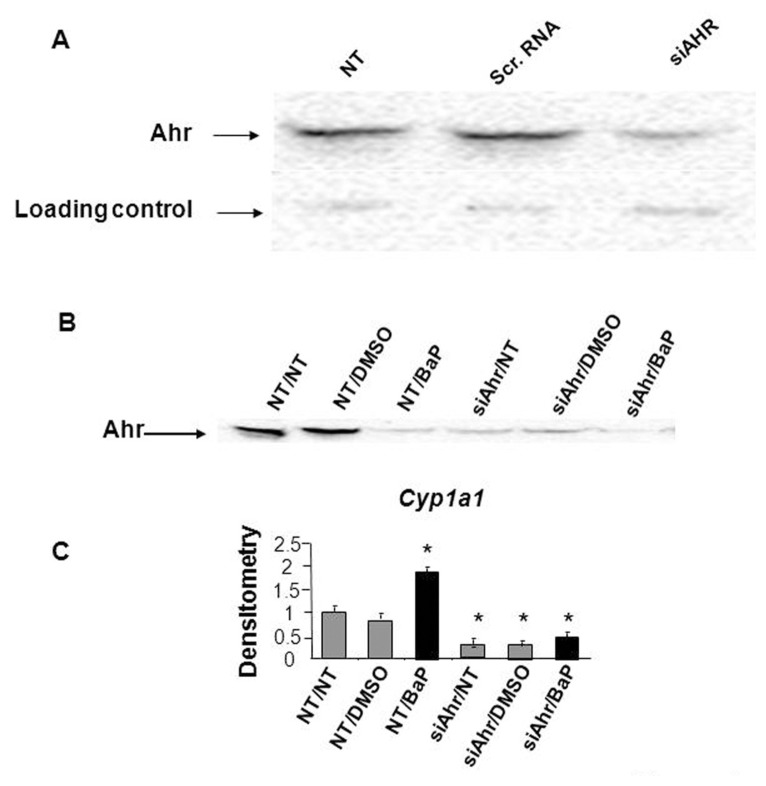

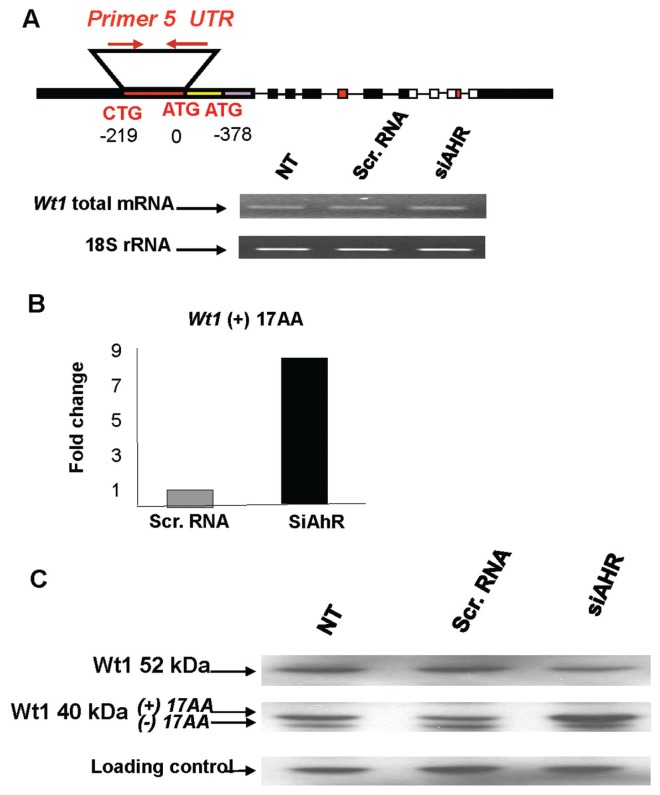

Ahr protein levels decreased by 50% to 70% in mK4 cells transfected with Ahr siRNA, and remained unchanged in cells treated with scrambled RNA (Figure 4A). The efficiency of the Ahr knockdown was examined in mK4 cells treated for 16 h with benzo(a)pyrene, a hydrocarbon ligand of Ahr that activates Cyp1a1 via transcriptional mechanisms (21). Cyp1a1 mRNA levels increased two-fold in benzo(a)pyrene-treated cells, and knockdown of Ahr protein abolished this effect (Figure 4B, C). The influence of AHR on Wt1 mRNA was examined next by RT-PCR using a primer set that hybridizes to the 5′ UTR region upstream of both the 52 and 40 kDa isoform translation start sites, and that recognizes all major Wt1 variants. No alterations in total mRNA levels were observed following Ahr knockdown (Figure 5A). Next, the expression of Wt1 splice variants generated by both exon 5 and 9 splicing was examined by real time PCR. Four different set of primers were used to specifically recognize each of the splice variants including, (+) 17AA, (−) 17AA, (+) KTS, and (−) KTS. We conclude that the primer set used to amplify (+) 17AA only recognizes this splice variant and discriminates between (+) and (−) 17AA variants. Ahr knockdown caused a pronounced increase in the (+) 17aa splice variant in mK4 cells (Figure 5B), while other Wt1 splice variants did not change. A reduction of cellular Ahr protein levels caused a significant reduction in 52 kDa Wt1 protein levels, while the levels of (+) 17aa 40 kDa isoform increased which is consistent with the increases in the mRNA level for this Wt1 splice variant (Figure 5C). These finding were consistent with morphological shifts of mK4 cells toward the lesser differentiated mK3 phenotype (not shown). Together, these data implicate Ahr in posttranscriptional regulation of Wt1 in embryonic kidney cells.

Figure 4.

Downregulation of Ahr by siRNA in the mK4 embryonic kidney cell line. (A) Ahr protein levels decreased in mK4 cells transfected with siRNA directed at the AhR, while protein levels remain unchanged in cells treated with scrambled (scr) RNA as a nonspecific negative siRNA control. NT = no treatment. One representative experiment from a total of ten is shown. Equal protein loadings were confirmed based on the signal obtained with the same antibody for a nonspecific band (25 kDa). (B) Hydrocarbon inducibility of Cyp1a1 is abolished in mK4 cells following Ahr siRNA transfection. (C) RT-PCR for Cyp1a1 shows that only siRNA against Ahr inhibits Cyp1a1 inducibility by BaP. One representative experiment out of three is shown. Densitometry is shown in arbitrary units. * denotes statistical differences from respective NT controls.

Figure 5.

Regulation of Wt1 by Ahr. Expression profiles of Wt1 mRNA or protein were examined in mK4 cells following siRNA Ahr knockdown. (A) RT-PCR was performed using a primer set that hybridizes to the Wt1 5′ UTR region upstream of the translation start sites for the 52 and 40 kDa isoforms. Ahr knockdown did not alter total Wt1 mRNA levels. The signal for 18S rRNA is shown as a normalization control. (B) Real time PCR was performed using primer sets specific for the (±) KTS and (±) 17 AA Wt1 splice variants. Scr = scrambled. AhR knockdown caused a pronounced increase in (+) 17 AA Wt1 expressions in mK4 cells. (C) Western blot analysis showed that Ahr knockdown caused selective decreases in 52 kDa Wt1 protein isoform and corresponding increases in 40 kDa isoforms. A nonspecific ~80-kDa protein recognized by the Wt1 antibody was used as a loading control. Similar results were seen in four different experiments.

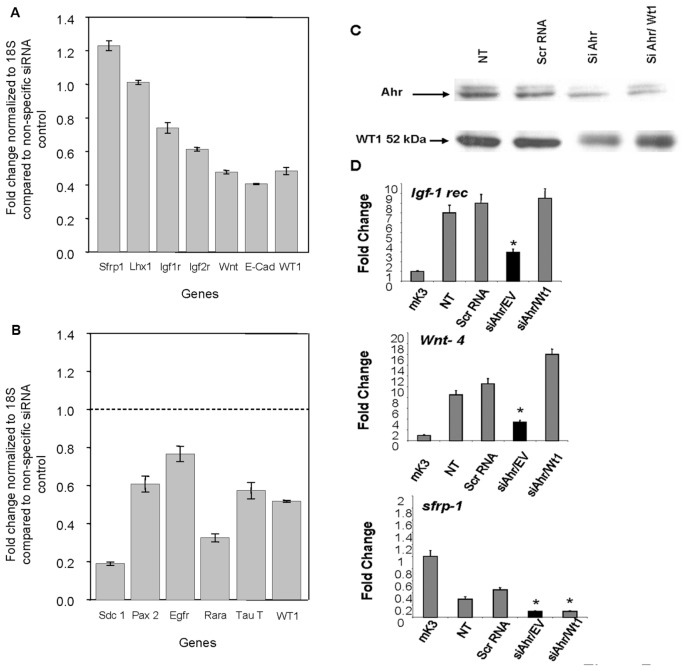

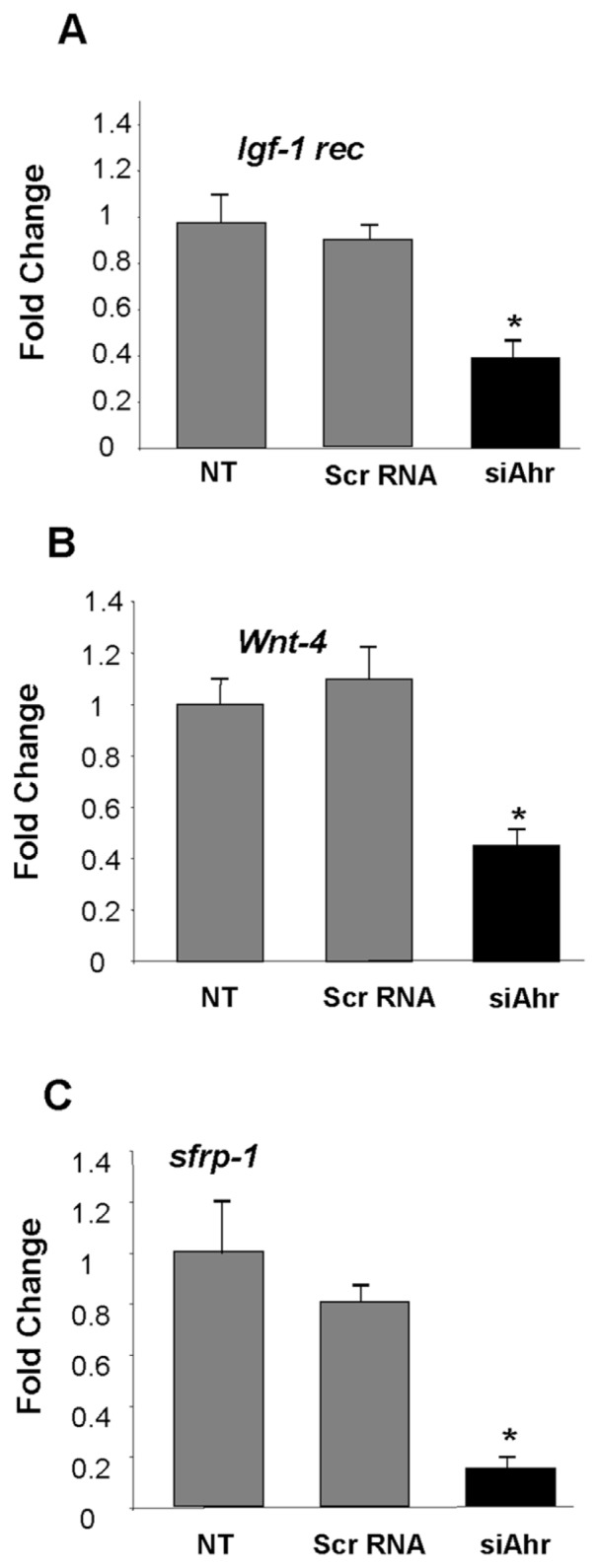

To determine if posttranscriptional deregulation of Wt1 by AHR is of functional consequence during the course of renal cell differentiation, the expression of downstream effector genes in nephro-genesis was examined by RT-PCR. Marked decreases in Igfr-1 rec., Wnt-4 and sFrp-1 were observed following Ahr knockdown in mK4 cells (Figure 6). To confirm the role of WT1 in the regulation of the downstream targets, siRNA degradation of WT1 was examined. siRNA-induced degradation of Wt1 downregulated markers of epithelial identity (Igf-1 rec, Igf-2 rec, Wnt-4 and E-cadherin), and either enhanced markers of mesenchymal identity such as sfrp1 (Figure 7A). No changes in Lhx1, a marker of renal vesicle and nephron progenitors, were observed with this treatment. Importantly, Wt1 silencing downregulated direct targets of Wt1 transcriptional control, confirming the usefulness of these markers to examine the differentiation state of developing kidneys (Figure 7B). To determine if these genes are regulated as a direct result of AHR-mediated interference with Wt1, mK4 cells were transfected for 24 h with CB6-Wt1, a plasmid encoding (−) 17aa/(−) KTS 52 kDa Wt1 protein, or empty vector, after downregulation of Ahr. Reduced Wt1 protein levels following Ahr knockdown were restored in mK4 cells transfected with Wt1 cDNA compared with empty vector, as determined by Western blot analysis (Figure 7C). Importantly, decreased Igf-1 rec. and Wnt-4 mRNA levels following Ahr knockdown were restored by the Wt1 cDNA, indicating that deregulation of these targets lies downstream of Ahr and is mediated by posttranscriptional deregulation of Wt1. Wt1 did not restore sfrp-1 mRNA levels, indicating that regulation of this target is not directly mediated by Ahr:Wt1 interactions, at least under the experimental conditions examined (Figure 7D).

Figure 6.

Ahr plays a regulatory role in programming of MET and differentiation of mK4 cells. Real time PCR was performed using specific primers for various molecular targets to determine the expression of effector genes essential in nephrogenesis. Ahr knockdown in mK4 caused a significant decreases in mRNA levels for Igf-1 rec. (A), Wnt-4 (B), and sfrp-1 (C) (* P < 0.05). One representative experiment out of three is shown. NT = no treatment; Scr = scrambled.

Figure 7.

Interactions between Ahr and Wt1 during the course of renal cell differentiation. (A) Downregulation of markers of differentiation by Wt1 siRNA. mK4 cells were cultured in the presence of Wt1 siRNA for 3 d. qRT-PCR values were calculated to represent fold change normalized to 18S compared with nonspecific siRNA control. sfrp-1 and lim 1 homeobox gene were used as markers of mesenchymal identity, while Igf-1 rec, Igf-2 rec, Wnt4, and E-cadherin were used as markers of epithelial identity. (B) Deregulation of Wt1 targets by Wt1 siRNA. mK4 cells were cultured in the presence of Wt1 siRNA for 3 d. qRT-PCR values were calculated to represent fold change normalized to 18S compared with nonspecific siRNA control. Syndecan1, paired box protein 2, EGF rec, retinoic acid receptor alpha, taurine transporter, and Wilms tumor transcription factor. (C) The mK4 cells were transfected for 24 h with the CB6-Wt1 (−) exon 5/(−) exon 9 plasmid encoding for 52 kDa Wt1 protein or empty vector after transfection with Ahr siRNA. Reduced Wt1 protein levels following Ahr knockdown were rescued in cells transfected with Wt1 cDNA compared with empty vector. (D) Real time PCR shows decreased mRNA levels for Igf-1 rec. and Wnt-4 following Ahr knockdown and effective rescue in cells transfected with Wt1 cDNA; however, decreases in sFrp-1 mRNA following Ahr knockdown were not restored in cells transfected with Wt1 cDNA. One representative experiment out of three is shown. NT = no treatment.

DISCUSSION

A developmentally-regulated pattern of Ahr expression in the kidney was first reported by Abbott et al. (22) who demonstrated that levels of Ahr protein are significantly higher in renal epithelial cells compared with mesenchymal cells, and downregulated by Ahr ligands. Bryant et al. (23) later showed that Ahr mRNA increases in metanephric tubules from GD:12–14, with continued expression throughout the life of the mouse. A casual link between Ahr and nephrogenesis was established in experiments showing that renal development is delayed in metanephric organ cultures of embryonic kidneys from Ahr−/− mice, or following ligand-induced downregulation of Ahr protein (5). Here we show that Ahr is involved in the regulation of developmentally-specific patterns of gene expression during MET in the kidney. Specifically, evidence is presented that: a) Ahr−/− embryos exhibit delayed epithelialization compared with wild-type counterparts; b) AHR and WT1 protein levels correlate with the degree of cellular differentiation in mK3 and mK4 cell lines; c) downregulation of Ahr protein disrupts gene expression profiles and differentiation programs in embryonic kidney cells lines.

The essential role of Wt1 in kidney development was unequivocally established in studies showing that homozygous Wt1 knockout mice fail to develop metanephric kidneys and die in utero (7). In homozygous Wt1 knockout mice, the ureteric bud fails to grow out of the mesonephric duct and metanephric mesenchyme dies. Wt1 is expressed selectively in metanephric blastema, S-shaped bodies and glomerular epithelium during kidney development, and confined to the podocyte layer of the mature nephrons (24). Wt1 is mutated in a proportion of nephroblastomas, embryonic kidney tumors characterized histologically by incomplete epithelialization of the condensing renal mesenchyme. The evidence presented here indicates that Ahr plays a regulatory role during nephrogenesis and that this function is linked to regulation of the Wt1 signaling. The observed reduction in numbers of glomeruli in Ahr null mice may be explained by developmental delay and/or direct interference with metanephric epithelialization in Ahr null mice. It is interesting to note that although the molecular and cellular phenotypes elicited by BaP in the developing kidney are largely mediated by protea-some-mediated downregulation of AHR (25), BaP arrested metanephric differentiation at an earlier point than AHR null mice. These settled differences likely reflect the complexity of the biological response since disruption of metanephric differentiation by the carcinogen is known to involve AHR-dependent reactivation of repetitive sequences within the embryonic kidney genome (26,27).

Recent studies in this laboratory have shown that a coisogenic mouse strain expressing a functionally inactive D2N Ahrd allele exhibits a 0.5- to 1-d delay in nephrogenesis compared with wild-type mice (25). Of note is that subtle renal deficits in renal cell differentiation associated with genetic loss of Ahr do not involve gross deficits in renal function, and only translate into reduced renal reserve capacity in Ahr null mice. Given that Ahr−/− embryos are viable at term, and do not exhibit overt deficits of renal structure, the pathogenetic consequences of delayed nephrogenesis seen in the absence of Ahr protein are likely coupled to deficits in renal function as mice continue to develop. Of note are reports showing that Ahr−/− mice exhibit cardiac hyperplasia and hypertrophy (28); pathobiological processes involving altered Wt1 functions.

RNA interference provided a complementary approach to gene ablation in vivo for the study of regulatory interactions between Ahr and Wt1 during the course of nephrogenesis. These experiments helped to differentiate renal developmental deficits that are associated directly with loss of Ahr protein from changes that are secondary to long-term adaptation. The efficiency of the siRNA knockdown approach was confirmed by the loss of Cyp1a1 inducibility in response to AHR activation by a hydrocarbon ligand in siRNA-treated cells. The downregulation of Ahr by siRNA altered the expression of (+) 17aa isoform in mK4 cells, suggesting that regulation of Wt1 by Ahr is mediated at the posttranscriptional level. This interpretation is in keeping with the finding that interference with Ahr signaling was without effect on total Wt1 mRNA levels. It should be noted that reciprocal interactions between Wt1 and Ahr may not be directly linked to phenotypic outcomes, and instead, impact nephrogenesis indirectly through the regulation of differentiation status. Interestingly, Ahr knockdown in mK3 cells, a line that exhibits a lesser degree of metanephric differentiation, did not affect the ratio of (±) exon 5 splice variants, and instead caused a shift in KTS splice variants toward the (−) KTS phenotype (not shown). This finding is consistent with previous observations that downregulation of Ahr protein following extended hydrocarbon ligand treatment in metanephric cultures shifted the (±) KTS ratio toward the (−) KTS phenotype in an Ahr-dependent manner (5).

The loss of Ahr protein in vivo correlated with decreased levels of 52 kDa Wt1 protein. Furthermore, expression of the 40 kDa Wt1 isoforms was correlated inversely with the degree of renal cell differentiation. A mechanistic link between Wt1 isoforms and Ahr is consistent with the finding that downregulation of Ahr protein in mK4 cells shifted the pattern of Wt1 expression from the mature 52 kDa isoform to the lower molecular weight isoforms. These findings suggest that these Wt1 isoforms support different cellular functions, an interpretation that is consistent with shifts in Wt1 protein expression profiles in mK3 cells compared with mK4 cells. Whether regulation of Wt1 splicing is a result of direct interactions of Ahr with the cellular splicing machinery, or involves exon skipping, or changes in mRNA stability is not known.

The relevance of functional Ahr/Wt1 interactions was monitored based on the expression of Bf-2, srrp-1, Igf-1rec. and Wnt-4. These genes play essential roles during MET in nephrogenesis, with Igf-1 rec., Wnt-4 and E-cadherin recognized as downstream targets of Wt1 during the course of renal cell differentiation and nephrogenesis (29,30). A role for Igf-1 rec. in renal cell differentiation is well documented, with ubiquitous expression found to be developmentally regulated during metanephric maturation, and enhanced during tubulogenesis (31). Wnt-4 is a mesenchymal signal for epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney, and is expressed in pre-tubular mesenchymal cells shortly before aggregation and transformation into epithelial tubules (32). Wnt signaling is initiated by interaction of the Wnt protein with frizzled receptors (33). In addition to the membrane-bound forms of frizzled, several genes encoding soluble homologous proteins have been identified (34). These secreted frizzled-related proteins bind Wnt in the developing metanephros and function as modulators of Wnt signaling. E-cadherin is recognized as a Wt1 target gene (18), and a regulator of the epithelial phenotype. In keeping with their unique functions during the course of renal cell differentiation, mK4 cells were found to express higher levels of Igf-1 rec., Wnt-4 and E-cadherin than the lesser differentiated mK3 cells. In contrast, the expression of Bf-2 and sFrp-1 was higher in mK3 than mK4 cells. Both AHR and WT1 increased as a function of renal cell differentiation status in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that these proteins are functionally linked in the regulation of MET.

AHR functions as a transregulator of gene expression during the course of mammalian cell differentiation (35). A role for AHR in posttranscriptional control of gene expression has not been recognized previously. Thus, the influence of AHR on developmentally-regulated expression of Wt1 splice variants during renal differentiation is intriguing. The relevance of these findings is emphasized by reports that differential splicing of exon 5 occurs in human kidneys and in Wilms tumor samples (9). While the ±KTS sequence is conserved throughout the species, and necessary for renal development, exon 5 is only present in placental mammals and is not required for nephrogenesis, implantation or lactation (36). Evidence for participation of exon 5 in transcriptional repression or Par4 binding suggests a possible role of this variant in the regulation of Wt1 expression in differentiated cells such as podocytes (37,15). Thus, future studies should investigate the role of AHR and exon 5 variants of Wt1 in the regulation of renal cell differentiation. The involvement of AHR in the regulation of murine nephrogenesis raises important questions about its role in human kidney development and the linkage between prenatal exposures to AHR ligands and deficits in renal developmental programming (13,14,22,23,38).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NIH Grants ES04917, ES012542 and ES014443. The authors wish to thank Steven Potter (Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA) for providing the mK3 and mK4 cell lines, Aart G Jochemsen (Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands) for Wt1 cDNA plasmids and Vilius Stribinskis for helpful discussions. The assistance of Marlene Steffen and Diego Montoya is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Online address: http://www.molmed.org

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that they have no competing interests as defined by Molecular Medicine, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and discussion reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barker DJ, Winter PD, Osmond C, Margetts B, Simmonds SJ. Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet. 1989;2:577–80. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90710-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim K, Armitage JA, Stefanidis A, Oldfield BJ, Black MJ. Intrauterine growth restriction in the absence of postnatal ‘catch-up’ growth leads to improved whole body insulin sensitivity in rat offspring. Pediatr Res. 2011 doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31822a65a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menendez-Castro C, et al. Early and late postnatal myocardial and vascular changes in a protein restriction rat model of intrauterine growth restriction. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nanez A, Ramos KS. Introduction and Overview of Receptor Systems. In: McQueen CA, editor. Comprehensive Toxicology. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Elsevier; San Diego: 2010. pp. 71–80. editor in chief. Available at: http://www.knovel.com/web/portal/browse/display?_EXT_KNOVEL_DISPLAY_bookid=3459&VerticalID=0. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falahatpisheh MH, Ramos KS. Ligand-activated Ahr signaling leads to disruption of nephrogenesis and altered Wilms’ tumor suppressor mRNA splicing. Oncogene. 2003;22:2160–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bittinger MA, Nguyen LP, Bradfield CA. Aspartate aminotransferase generates proagonists of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:550–6. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreidberg JA, et al. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell. 1993;74:679–91. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90515-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menke AL, van der Eb AJ, Jochemsen AG. The Wilms’ tumor 1 gene: oncogene or tumor suppressor gene? Int Rev Cytol. 1998;181:151–212. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iben S, Royer-Pokora B. Analysis of native WT1 protein from frozen human kidney and Wilms’ tumors. Oncogene. 1999;18:2533–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang ZY, Qiu QQ, Gurrieri M, Huang J, Deuel TF. Wt1, the Wilm’s tumor suppressor gene product, represses transcription through an interactive nuclear protein. Oncogene. 1995;10:1243–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Englert C, et al. Truncated wt1 mutants alter the subnuclear localization of the wild-type protein. PNAS. 1995;92:11960–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.11960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner KD, Wagner N, Schedl A. The complex life of WT1. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1653–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammes A, et al. Two splice variants of the Wilms’ tumor 1 gene have distinct functions during sex determination and nephron formation. Cell. 2001;106:319–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00453-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbaux S, et al. Donor splice-site mutations in WT1 are responsible for Frasier syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;17:467–70. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richard DJ, Schumacher V, Royer-Pokora B, Roberts SGE. Par4 is a coactivator for a splice isoform-specific transcriptional activation domain in WT1. Genes Dev. 2001;15:328–39. doi: 10.1101/gad.185901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renshaw J, King-Underwood L, Pritchard-Jones K. Differential splicing of exon 5 of the Wilms tumour (WT1) gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1997;19:256–66. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199708)19:4<256::aid-gcc8>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reiners JJ, Jr, Jones CL, Hong N, Myrand SP. Differential induction of Cyp1a1, Cyp1b1, Ahd4, and Nmo1 in murine skin tumors and adjacent normal epidermis by ligands of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Mol Carcinog. 1998;21:135–46. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199802)21:2<135::aid-mc8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosono S, et al. E-cadherin is a WT1 target gene. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10943–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peinnequin A, et al. Rat pro-inflammatory cytokine and cytokine related mRNA quantification by real-time polymerase chain reaction using SYBR green. BMC Immunol. 2004;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valerius MT, Patterson LT, Witte DP, Potter SS. Microarray analysis of novel cell lines representing two stages of metanephric mesenchyme differentiation. Mech Dev. 2002;112:219–32. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitlock JP., Jr Induction of cytochrome P4501A1. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;39:103–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbott BD, Perdew GH, Buckalew AR, Birnbaum LS. Interactive regulation of Ah and glucocorticoid receptors in the synergistic induction of cleft palate by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and hydrocortisone. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1994;128:138. doi: 10.1006/taap.1994.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bryant PL, Clark GC, Probst MR, Abbott BD. Effects of TCDD on Ah receptor, ARNT, EGF, and TGF-alpha expression in embryonic mouse urinary tract. Teratology. 1997;55:326–37. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199705)55:5<326::AID-TERA5>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pritchard-Jones K, et al. The candidate Wilms’ tumour gene is involved in genitourinary development. Nature. 1990;346:194–7. doi: 10.1038/346194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nanez A, Ramos IN, Ramos KS. A mutant AHR allele protects the embryonic kidney from hydrocarbon-induced deficits in fetal programming. Environ Health Perspect. 2011 2011 Jul 29; doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103692. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teneng I, Stribinskis V, Ramos KS. Context specific regulation of LINE-1. Genes Cells. 2007;12:1101–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramos KS, Montoya-Durango DE, Teneng I, Nanez A, Stribinskis V. Epigenetic control of embryonic renal cell differentiation by L1 retrotransposon. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:693–702. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thackaberry EA, et al. Insulin regulation in AhR-null mice: embryonic cardiac enlargement, neonatal macrosomia, and altered insulin regulation and response in pregnant and aging AhR-null females. Toxicol Sci. 2003;76:407–17. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sim EUH, et al. Wnt-4 regulation by the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene, WT1. Oncogene. 2002;21:2948–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werner H, Roberts CT, Jr, Rauscher FJ, 3rd, LeRoith D. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor I receptor gene expression by the Wilms’ tumor suppressor WT1. J Mol Neurosci. 1996;7:111–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02736791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duong Van, Huyen JP, et al. Spatiotemporal distribution of insulin-like growth factor receptors during nephrogenesis in fetuses from normal and diabetic rats. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314:367–79. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0803-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stark K, Vainio S, Vassileva G, McMahon AP. Epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney regulated by Wnt-4. Nature. 1994;372:679. doi: 10.1038/372679a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vincan E. Frizzled/WNT signalling: the insidious promoter of tumour growth and progression. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1023–34. doi: 10.2741/1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshino K, et al. Secreted Frizzled-related proteins can regulate metanephric development. Mech Dev. 2001;102:45. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chesire DR, Dunn TA, Ewing CM, Luo J, Isaacs WB. Identification of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor as a putative Wnt/{beta}-Catenin pathway target gene in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2523–33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Natoli TA, et al. A mutant form of the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene WT1 observed in Denys-Drash Syndrome interferes with glomerular capillary development. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2058–67. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000022420.48110.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hewitt SM, Saunders GF. Differentially spliced exon 5 of the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 modifies gene function. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:621–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reiner J, Jones C, Jr, Hong N, Myrand S. Differential induction of cyp1A1, cyp1B1, ahd4, and nmo1 in murine skin tumors and adjacent normal epidermis by ligands of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Mol Carcinog. 1994;21:135–46. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199802)21:2<135::aid-mc8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]