Abstract

Borrelia burdorferi genotype in the northeastern United States is associated with Lyme borreliosis severity. Analysis of DNA sequences of the outer surface protein C gene and rrs-rrlA intergenic spacer from extracts of Ixodes spp. ticks in 3 US regions showed linkage disequilibrium between the 2 loci within a region but not consistently between regions.

Keywords: Lyme disease, Lyme borreliosis, Ixodes scapularis, Ixodes pacificus, Borrelia burgdorferi, genotype, ospC, bacteria, vector-borne infections, dispatch

Most bacterial pathogens comprise a variety of strains in various proportions. For Borrelia burgdorferi, an agent of Lyme borreliosis, strains differ in their reservoir host preferences (1), propensities to disseminate in humans (2,3), and prevalences in ticks by geographic area (4,5). Strain identification of B. burgdorferi now is predominantly based on DNA sequences of either of 2 genetic loci: 1) the plasmid-borne, highly polymorphic ospC gene, which encodes outer surface protein C (6,7), or 2) the intergenic spacer (IGS) between the rrs and rrlA rDNA, here called IGS1. Other loci for genotyping are the plasmid-borne ospA gene (7) and the rrfA-rrlB rDNA intergenic spacer, here called IGS2 (8). The apparent clonality of B. burgdorferi was justification for inferring strain identity from a single locus (9,10), but the extent of genomewide genetic exchange in this species may have been underestimated (6).

Given reports of an association between disease severity and B. burgdorferi genotype (2,3), prediction of a strain’s virulence potential from its genotype has clinical, diagnostic, and epidemiologic relevance. But is a single locus sufficient for this assessment?

The Study

To investigate this issue, we determined sequences of ospC and IGS1 loci, and in selected cases the ospA and IGS2 loci, in 1,522 DNA extracts from B. burgdorferi–infected Ixodes scapularis nymphs collected from the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and north-central United States during the summers of 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2007, as described (4,11). We also included results from 214 infected I. pacificus nymphs collected in Mendocino County, California (5); 20 infected I. pacificus adults from Contra Costa County, California (J. Bunikis and A.G. Barbour, unpub. data); and 10 B. burgdorferi genomes (strains B31, ZS7, 156a, 64b, 72a, 118a, WI91-23, 94a, 29805, and CA-11.2a), for which sequences are publicly available (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST), based on 8 chromosomal housekeeping genes, had been carried out for several strains represented in the extracts (Table) (4,12). The corresponding MLST types of the 10 genome sequences were assigned by reference to a B. burgdorferi MLST database (http://borrelia.mlst.net) (12). For this study, we also determined the MLST type of strain CA8.

The methods for 1) DNA extraction from ticks (11), 2) PCR amplification of ospC, ospA, and IGS1 (7), 3) amplification of IGS2 (8), and 4) amplification of 8 chromosomal loci for MLST (12) have been described. Sequences for both strands were determined from either PCR products or cloned fragments with custom primers (7). We followed the basic nomenclature of Wang et al. (13) until, after exhausting the alphabet, we assigned both a letter and, arbitrarily, the number 3 (e.g., C3) when a new nucleotide sequence differed by >8% from known ospC alleles. We distinguished ospC variants with <1% sequence difference by adding a lowercase letter, e.g., Da and Db. Except for ospC D3 and Oa, novel polymorphisms were confirmed in at least 1 other sample. To simplify IGS1 nomenclature, we numbered types sequentially, beginning with the original 9 types (7); ospA alleles (7) and IGS2 loci were likewise sequentially numbered. The Table A1 provides accession numbers for all sequences, as well as original and revised names for IGS1 sequences.

For 741 Ixodes ticks from northeastern and north-central United States or from northern California, 1 ospC allele was identified and sequenced. In the remaining samples, we found a mixture of strains or evidence of >2 ospC and/or >2 IGS sequences (9). In 678 (91%) of the 741 samples with a single ospC, the allele could be matched with particular IGS1 (Table). We identified 9 unique ospC sequences: Fc, Ob, Ub, A3, B3, C3, D3, E3, and F3, all from the north-central United States. Alleles H3 and I3 of California were recently reported by Girard et al. (5). Of 32 codon-aligned ospC sequences, 6 pairs and 1 trio (Fa, Fb, and Fc) differed in sequence by <1% (Figure, panel A). Nine novel IGS1 sequences, numbered 24–31 and 33, were discovered in samples from which ospC alleles were determined.

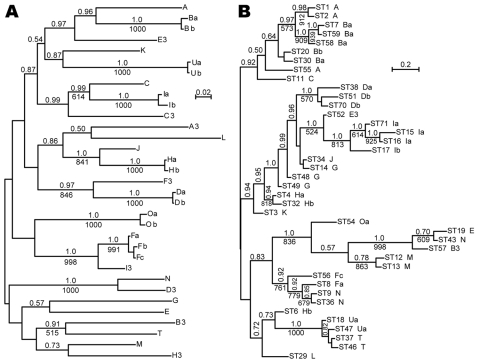

Figure.

A) Bayesian and maximum-likelihood phylogenetic inference of outer surface protein C (ospC) gene sequences and B) concatenated multilocus sequence typing (MLST) sequences of Borrelia burgdorferi. Sequences were aligned by codon. Labels at the tips refer to ospC alleles (A) or MLST (ST) and linked ospC alleles (B; Table). Consensus phylograms were the output of the MrBayes version 3.1.2 algorithm (http://mrbayes.csit.fsu.edu). There were 500,000 generations with the first 1,000 discarded. Nodes with posterior probabilities of >0.5 are indicated by values above the branches. Below the branches are integer values for nodes with support of >500 of 1,000 bootstrap iterations of the maximum-likelihood method, as carried out with the PhyML 3.0 algorithm (www.atgc-montpellier.fr/phyml). For both data sets and both algorithms, the models were general time reversible with empirical estimations of the proportions of invariant sites and gamma shape parameters. Scale bars indicate genetic distance. GenBank accession numbers for sequences are given in the Table A1.

When we confined analysis to samples from northeastern states, we confirmed linkage disequilibrium between ospC and IGS1 loci (7,10,14). However, when results from north-central states and California were included, a different picture emerged (Table, Figure, panel B). Most of the ospC alleles showed concordance with the chromosomal loci; monophyletic MLST showed either the same ospC allele or a minor variant of it. However, in several instances, the ospC alleles were linked to different IGS1 sequences, different ospA sequences, and/or different MLST with internal nodes in common. We observed this linkage for ospC alleles A, G, Hb, and N. In the case of ospC Hb, the shared internal node was deep.

We applied the Simpson index of diversity, as implemented by Hunter and Gaston (15), to the data in the Table to compare the discriminatory power (DP) of genotyping on the basis of a combination of ospC and IGS1 sequences with genotyping by 8-locus MLST (12). For double-locus typing, there were 43 types were found for 678 strains; DP value was 0.96. For MLST in this data set, 36 types were shown for 554 strains; DP was 0.95. In the study of Hoen et al. in which selection was made for geographic isolation, 37 types were distributed among 78 strains; DP was 0.97 (4).

Conclusions

Dependence on a single locus for typing may falsely identify different lineages as the same, especially when the samples come from different regions. Other loci may be as informative as ospC or IGS1, but the abundance of extant sequences for these loci justifies their continued use. Uncertainties about the linkage of ospC and IGS1 usually can be resolved by sequencing the ospA allele (Table). IGS2 provided little additional information in this study.

One interpretation of these findings is that lateral gene transfer of all or nearly all of an ospC gene has occurred between different genetic lineages. We previously had not detected recombination at the IGS1 locus on the chromosome (7), but there may be recombination at other chromosomal loci, as well as plasmid loci (6). Besides extending the understanding of the geographic structuring of the B. burgdorferi population, the results indicate that the ospC allele does not fully represent the complexity of B. burgdorferi lineages; thus, inferring phenotypes on the basis of this single locus should be made with caution.

Acknowledgment

We thank Robert S. Lane for providing strain CA8.

This research was supported by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cooperative Agreement CI 00171-01 and National Institutes of Health grant AI065359.

Biography

Ms Travinsky is a senior research associate in the Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, University of California, Irvine. Her research interests include the genetic diversity and phylogeography of Borrelia species.

Table A1. GenBank accession numbers of sequences of Borrelia burgdorferi in this study*.

*Boldface indicates new accession number from this study. †IGS1, rrs-rrlA intergenic spacer region. ‡IGS2, rrf-rrlB intergenic spacer.

Table. Linkages between ospC alleles and other loci in Borrelia burgdorferi strains*.

| ospC | IGS1 | Geographic region* | Representative cultured isolate or tick sample† | IGS1-ospC associations‡ | ospA | IGS2 | MLST§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 1, 2 | B31 | 45/52 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A | 11 | 2 | 2206617 | 4/4 | 22 | 1 | 55 |

| A | 10 | 3 | CA4, CA6 | 14/18 | 23 | 1 | 2 |

| Ba | 3 | 1 | 64b, B373 | 39/41 | 3 | 1 | 7,58,59 |

| Ba | 6 | 2 | 51405UT | 7/9 | 14 | 1 | 30 |

| Bb | 16 | 4 | ZS7 | – | 28 | – | 20 |

| C | 24 | 1 | JD1, BL515 | 10/10 | 8 | 5 | 11 |

| Da | 5 | 1 | 516113 | 13/14 | 5 | 4 | 38 |

| Db | 5 | 2 | 424404 | 13/15 | 18 | 7 | 51 |

| Db | 19 | 3 | CA11.2A | 16/16 | 27 | 4 | 70 |

| E | 9 | 1, 2 | N40, B348 | 17/19 | 9 | 1 | 19 |

| Fa | 17 | 1, 2, 3 | B156 | 61/64 | 3 | 4 | 8 |

| Fb | 18 | 2 | MI407 | 14/19 | 8 | 6 | – |

| Fc | 18 | 2 | 1469205 | 7/8 | 13 | 6 | 56 |

| G | 26 | 1 | 72a, MR616 | 10/11 | 9 | 4 | 14 |

| G | 22 | 2, 3 | 1468503 | 9/10 | 21 | 4 | 48,49 |

| Ha/Hb | 12 | 1 | B509/156a | 13/13 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Hb | 12 | 2 | 519014UT | 56/65 | 11 | 2 | 32 |

| Hb | 13 | 3 | CA92-0953 | 20/20 | 23 | 2 | 6 |

| Ia | 7 | 1 | B500, B331 | 12/16 | 7 | 4 | 15,16 |

| Ia | 7 | 2 | WI91-23 | 5/5 | 11 | 4 | 71 |

| Ib | 7 | 3 | CA92-1096 | – | 30 | 4 | 17 |

| J | 20 | 1, 2 | 118a | 3/5 | 8 | 4 | 34 |

| K | 2 | 1 | 297 | 67/68 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| K | 14 | 2 | 149901 | 7/10 | 31 | 2 | – |

| L | 14 | 2 | 47703UT | 23/25 | 8 | 2 | 29 |

| M | 6 | 1 | 29805 | 4/4 | 2 | 3 | 12 |

| M | 6 | 2, 3 | CA92-1337 | 16/16 | 17 | 3 | 13 |

| N | 4 | 1 | MR661, 500203 | 41/41 | 4 | 10 | 9,36 |

| N | 23 | 2 | 51108 | 8/10 | 2 | 1 | 43 |

| Oa | 27 | 1 | 501427 | 1/1 | – | – | 54 |

| Ob | 6 | 2 | 2207807 | 6/7 | 2 | – | – |

| T | 28 | 1 | 23509 | 16/16 | 8 | 4 | 37 |

| T | 29 | 2 | 1476702 | 10/11 | 20 | 4 | 46 |

| Ua | 8 | 1 | 94a, B485 | 19/19 | 8 | 4 | 18 |

| Ua | 8 | 2 | 48802 | 4/4 | 16 | 4 | 47 |

| Ua | 17 | 2 | 2207116 | 4/4 | 12 | 10 | – |

| Ub | 30 | 2 | 426905 | 3/3 | 8 | 9 | – |

| A3 | 14 | 2 | 2206613 | 6/6 | 19 | 2 | – |

| B3 | 23 | 1, 2 | 2250201 | 3/3 | 17 | 1 | 57 |

| C3 | 17 | 2 | 50202 | 6/9 | 15 | 5 | – |

| D3 | 31 | 2 | 2150902 | 1/1 | – | – | – |

| E3 | 20 | 2 | 2127701 | 4/4 | 8 | 8 | 52 |

| E3 | 21 | 3 | HRT25 | 12/12 | 24 | – | – |

| E3 | 5 | 3 | LMR28 | 12/12 | 25 | – | – |

| F3 | 5 | 2 | 1456802 | 8/12 | 8 | 4 | – |

| H3 | 25 | 3 | CA8 | 37/40 | 26 | 4 | (72) |

| I3 | 17 | 3 | CA11, CA12 | 5/5 | 27 | 4 | – |

*Regions: 1, northeastern United States; 2, north-central United States; 3, northern California; 4, western Europe; osp, outer surface protein; IGS, intergenic spacer; MLST, multilocus sequence typing; –, MLST not determined. †Tick samples (4) are indicated by italics; strains with genome sequences are indicated in boldface. ‡Number of tick extracts with the listed IGS1 locus (numerator)/number of extracts with the listed ospC allele (denominator). §MLST from (4,12) or this study (in parentheses).

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Travinsky T, Bunikis J, Barbour AG. Geographic differences in genetic locus linkages for Borrelia burgdorferi. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2010 Jul [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1607.091452

References

- 1.Brisson D, Dykhuizen DE. ospC diversity in Borrelia burgdorferi: different hosts are different niches. Genetics. 2004;168:713–22. 10.1534/genetics.104.028738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wormser GP, Brisson D, Liveris D, Hanincova K, Sandigursky S, Nowakowski J, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi genotype predicts the capacity for hematogenous dissemination during early Lyme disease. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1358–64. 10.1086/592279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dykhuizen DE, Brisson D, Sandigursky S, Wormser GP, Nowakowski J, Nadelman RB, et al. The propensity of different Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto genotypes to cause disseminated infections in humans. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:806–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoen AG, Margos G, Bent SJ, Diuk-Wasser MA, Barbour AG, Kurtenbach K, et al. Phylogeography of Borrelia burgdorferi in the eastern United States reflects multiple independent Lyme disease emergence events. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15013–8. 10.1073/pnas.0903810106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girard YA, Travinsky B, Schotthoefer A, Federova N, Eisen RJ, Eisen L, et al. Population structure of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi in the western black-legged tick (Ixodes pacificus) in northern California. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7243–52. 10.1128/AEM.01704-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu WG, Schutzer SE, Bruno JF, Attie O, Xu Y, Dunn JJ, et al. Genetic exchange and plasmid transfers in Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto revealed by three-way genome comparisons and multilocus sequence typing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14150–5. 10.1073/pnas.0402745101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunikis J, Garpmo U, Tsao J, Berglund J, Fish D, Barbour AG. Sequence typing reveals extensive strain diversity of the Lyme borreliosis agents Borrelia burgdorferi in North America and Borrelia afzelii in Europe. Microbiology. 2004;150:1741–55. 10.1099/mic.0.26944-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derdakova M, Beati L, Pet'ko B, Stanko M, Fish D. Genetic variability within Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies established by PCR-single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis of the rrfA-rrlB intergenic spacer in Ixodes ricinus ticks from the Czech Republic. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:509–16. 10.1128/AEM.69.1.509-516.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu WG, Dykhuizen DE, Acosta MS, Luft BJ. Geographic uniformity of the Lyme disease spirochete (Borrelia burgdorferi) and its shared history with tick vector (Ixodes scapularis) in the northeastern United States. Genetics. 2002;160:833–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanincova K, Liveris D, Sandigursky S, Wormser GP, Schwartz I. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto is clonal in patients with early Lyme borreliosis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5008–14. 10.1128/AEM.00479-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbour AG, Bunikis J, Travinsky B, Hoen AG, Diuk-Wasser MA, Fish D, et al. Niche partitioning of Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia miyamotoi in the same tick vector and mammalian reservoir species. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:1120–31. 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.09-0208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margos G, Gatewood AG, Aanensen DM, Hanincova K, Terekhova D, Vollmer SA, et al. MLST of housekeeping genes captures geographic population structure and suggests a European origin of Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8730–5. 10.1073/pnas.0800323105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang IN, Dykhuizen DE, Qiu W, Dunn JJ, Bosler EM, Luft BJ. Genetic diversity of ospC in a local population of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Genetics. 1999;151:15–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attie O, Bruno JF, Xu Y, Qiu D, Luft BJ, Qiu WG. Co-evolution of the outer surface protein C gene (ospC) and intraspecific lineages of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in the northeastern United States. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7:1–12. 10.1016/j.meegid.2006.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter PR, Gaston MA. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2465–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]