Abstract

Studies have suggested that enzootic strains of Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) subtype ID in the Amazon region, Peru, may be less pathogenic to humans than are epizootic variants. Deaths of 2 persons with evidence of acute VEE virus infection indicate that fatal VEEV infection in Peru is likely. Cases may remain underreported.

Keywords: Venezuelan equine encephalitis, VEE, encephalitis, neurological disease, Panama/Peru genotype, Amazon Basin, viruses, zoonoses, Peru, dispatch

Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) is an emerging zoonotic disease in the Amazon region of Peru. After dengue, it is considered the second most important arboviral disease in Peru. Most human infections with VEE virus (VEEV) are caused by subtype ID (1–5), and within subtype ID, 6 genotypes have been described (6). In Peru, the Colombia/Venezuela, Panama/Peru, and Peru/Bolivia genotypes have been identified among VEEV subtype ID isolates (1,5,7). Epidemiologic investigations have failed to detect neurologic disease or deaths among >200 VEE cases in this country (T.J. Kochel, unpub. data). Only 2 fatal cases with VEEV subtype ID have been reported, both in Panama (6,8). In contrast, fatal cases with neurologic complications (estimated mortality rate 0.7%) have been described regularly for human outbreaks caused by VEEV subtypes IAB and IC (9–12). On the basis of these reports, it has been suggested that enzootic VEEV strains in Peru may be less pathogenic to humans than the epizootic variants (13). However, only 200 cases identified in Peru may not be enough to make such an assertion.

We recently described a severe infection in a 3-year-old boy who had VEEV subtype ID (14). Here we describe 2 fatal infections in persons with evidence of acute VEEV infection in Peru. One patient had confirmed subtype ID.

The Study

In 2000, the Naval Medical Research Center Detachment (NMRCD) and the Ministry of Health of Peru established a passive surveillance study to determine arboviral causes of febrile illness (protocol NMRCD.2000.0006). Patients with acute, undifferentiated febrile illness of <7 days were invited to enroll, and demographic and clinical information was obtained at the time of enrollment. Blood samples were obtained and assayed by virus isolation, and convalescent-phase samples were obtained 10 days to 4 weeks later for serologic studies.

Patient 1 was a 7-year-old girl from San Benito, a rural community near Yurimaguas city (Figure 1), who on June 19, 2006, was noted to have nasal congestion, sneezing, chills, malaise, myalgia, abdominal pain, and fever followed by several episodes of watery, nonbloody feces, and vomiting. Her condition rapidly worsened, and she began having tonic–clonic seizures. The next day the involuntary movement and vomiting stopped; however, other signs worsened and she became somnolent and prostrate. Later that day she was admitted to the Hospital Santa Gema of Yurimaguas with fever, dehydration, stupor, and signs of respiratory distress along with tonic–clonic seizures. Temperature was 40°C (104°F), blood pressure 90/50 mm Hg, respiratory rate markedly increased, and heart rate 132 beats/min. Distal cyanosis, nasal flaring, rhonchi without crackles, and supraclavicular and intercostal retractions were noted, but no jaundice, lymphadenopathy or conjunctival hemorrhage were observed. Hepatomegaly (liver 4 cm under the costal border), stupor, and neck stiffness were also noted. Laboratory test results showed a left shift in the leukocyte count and renal failure (Table 1). Blood smears were negative for malaria parasites. Preliminary diagnoses were sepsis, convulsive status, and respiratory distress. Later that day the patient was considered to have a complicated, febrile, neurologic illness, and a blood sample was sent for advanced analysis at the NMRCD in Lima, Peru, and the National Institute of Health of Peru.

Figure 1.

Selected sites in Peru of passive surveillance study to determine arboviral causes of febrile illness in Peru, established in 2000 by Naval Medical Research Center Detachment and the Ministry of Health of Peru (protocol NMRCD.2000.0006). Sites shown include those of 2 patients with evidence of acute Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus infection. Shaded area is Titicaca Lake.

Table 1. Laboratory test results for 2 patients infected with Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, Peru*.

| Testing | Patient no. 1 | Patient no. 2 | Reference range | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date blood collected | 2006 Jun 20 | 2005 Feb 28 | 2005 Mar 1 | ||

| Hematocrit, % | 36 | 36 | 22 | 38–44 | |

| Thromocytes, cells/mm3 |

233,000 |

|

143,750 |

NM |

150,000–450,000 |

| Leukocytes | |||||

| Total, cells/mm3 | 21,450 | 3,900 | NM | 4,500–10,000 | |

| Bands, % | 7 | 4 | NM | 3–5 | |

| Segmented cells, % | 84 | 72 | NM | 55–65 | |

| Eosinophils, % | 0 | 0 | NM | 0.5–4.0 | |

| Monocytes, % | 0 | 14 | NM | 3–8 | |

| Lymphocytes, % |

9 |

|

10 |

NM |

25–35 |

| ESR, mm/h | 41 | NM | NM | 1–15 | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 2.1 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 0.8–1.4 | |

| Urea, mg/dL | 115 | 206 | 238 | 20–45 | |

*NM, not measured; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

The girl was given supportive therapy with broad spectrum antibiotics, intravenous hydration, oxygen, and anticonvulsive medications (diazepam, phenytoin). On June 21, seizures persisted, and the patient became comatose and later died of respiratory arrest. Arterial blood gasses and electrolytes could not be measured because of the limited capacity of the hospital laboratory. The girl’s parents did not consent to lumbar puncture or autopsy.

Examination of the girl’s serum in Vero cells identified VEEV, and sequencing and phylogenetic analyses using previously described methods further identified it as subtype ID Panama/Peru genotype (Figure 2) (15). On the day the serum was collected (1 day after onset of signs), viremia titer was 1.8 ×104 PFU/mL, similar to titers from other VEEV-infected study patients who did not have neurologic complications (Table 2). The National Institute of Health reported the sample to be negative for leptospiral and rickettsial organisms, according to ELISA immunoglobulin (Ig) M and indirect immunofluorescent assays, respectively. Blood and cerebrospinal fluid cultures for bacteria were not attempted.

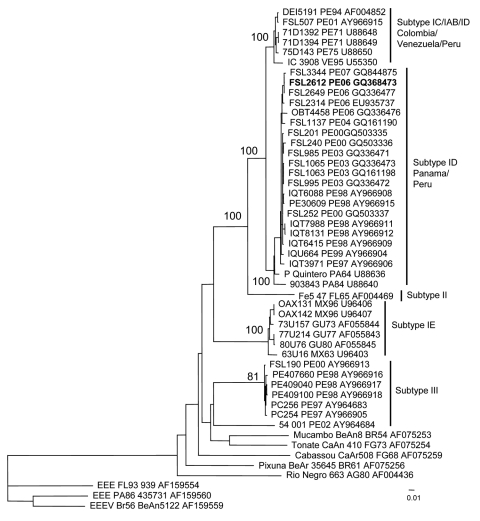

Figure 2.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) complex based on partial sequence of the PE2 segment (nucleotide positions ≈8385–9190 of the VEEV genome). The tree was rooted by using an outgroup of 3 major lineages of Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV). The strain isolated from a 7-year-old girl who died from acute VEEV infection in Peru, June 21, 2006, is in boldface. Viruses are labeled by code designation, abbreviated location name, year of isolation (last 2 digits of year only), and GenBank accession numbers of the corresponding sequences. PA, Panama; GU, Guatemala; MX, Mexico; FG, French Guiana; VE, Venezuela; BR, Brazil; AG, Argentina; PE, Peru; FL, Florida. Numbers indicate bootstrap values. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site.

Table 2. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus titers in 10 patients, Peru.

| Patient code | Age, y/sex | Location | Date of symptom onset | Date of blood collection | Serum titer, PFU/mL | Signs and symptoms |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | Bleed* | Fever | Seizure | GI† | Resp‡ | Aches§ | ||||||

| Patient 1 FSL2612 | 7/F | Yurimaguas, Loreto | 2006 Jun 19 | 2006 Jun 20 | 1.8 × 104 | + | – | + | + | + | + | + |

| FSL2649 | 32/M | Yurimaguas, Loreto | 2006 Aug 7 | 2006 Aug 8 | 3.4 × 104 | – | – | + | – | + | + | + |

| IQE1149 | 14/F | Iquitos, Loreto | 2005 Apr 14 | 2005 Apr 15 | 1.0 × 103 | – | – | + | – | – | – | + |

| IQE831 | 8/F | Iquitos, Loreto | 2005 Mar 13 | 2005 Mar 14 | 3.0 × 102 | – | – | + | – | – | – | + |

| IQE3605 | 6/M | Iquitos, Loreto | 2006 Apr 3 | 2006 Apr 4 | 1.0 × 102 | – | – | + | – | + | – | + |

| IQE3741 | 10/F | Iquitos, Loreto | 2006 Apr 21 | 2006 Apr 24 | 5.0 × 102 | – | – | + | – | + | – | + |

| IQE5023 | 7/M | Iquitos, Loreto | 2007 Feb 27 | 2007 Feb 28 | 1.3 × 104 | – | – | + | – | + | – | + |

| FMD1737 | 18/M | Puerto Maldonado, Madre de Dios | 2007 Dec 17 | 2007 Dec 19 | 5.0 × 102 | – | – | + | – | – | – | + |

| FMD1905 | 21/F | Puerto Maldonado, Madre de Dios | 2008 Feb 9 | 2008 Feb 12 | 3.0 × 103 | – | – | + | – | + | – | + |

| Patient 2¶ | 25/M | Puerto Maldonado, Madre de Dios | 2005 Feb 24 | 2005 Feb 28 | NM | + | + | + | – | + | – | + |

*Epistaxis, bleeding gums, ecchymosis, purpura, hematochezia, or melena. †Gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain). ‡Respiratory (cough, dyspnea, or cyanosis). §Arthralgia, myalgia, bone pain, malaise, or prostration. ¶Virus isolation attempts unsuccessful; ELISA immunoglobulin M results positive for Venezuelan equine encephalitis. NM, not measured.

Patient 2 was a 25-year-old man from Puerto Maldonado, a city in the department of Madre de Dios (Figure 1). On February 24, 2005, he reported fever, headache, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Because he was from an outlying rural area, he was taken to the local health center where he received intravenous rehydration and partially recovered. The patient stayed at home, but his signs and symptoms persisted. On February 27, jaundice and epistaxis developed, and the local health center referred him to the Santa Rosa Hospital in Puerto Maldonado, where he was admitted on February 28. The patient’s status deteriorated quickly; hematuria and hematemesis were followed by liver and renal failure (Table 1), and the patient died on March 1. Postmortem examination found multiple hemorrhages in his lungs, kidneys, and stomach. A serum sample collected at the time of admission was positive for VEEV antibodies, according to ELISA IgM (titer 6,400) (2,3). The case was presumed to be VEE, although virus isolation attempts were unsuccessful. Serologic assays produced negative results for leptospiral and arboviral diseases, including dengue, Mayaro, yellow fever, Oropouche, and Eastern equine encephalitis.

Conclusions

Patient 1 had no previous history of neurologic disease or poor health. VEEV subtype ID infection (Panama/Peru genotype) was confirmed. Because her viremia titer was similar to titers of other patients who did not have neurologic complications and survived VEEV infection, viremia levels alone may not account for the difference in disease outcome. Although VEEV was isolated from the patient’s serum and she met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s diagnostic criteria for confirmed VEE (www.cdc.gov/ncphi/disss/nndss/casedef/arboviral_current.htm), we cannot rule out concomitant bacterial meningitis in this patient, who had meningismus and leukocytosis. The limited extent of our diagnostic procedures prevent us from concluding with certainty that VEEV infection was the main cause of death.

Patient 2 had severe hemorrhagic complications. Although an uncommon manifestation of VEEV infection, these complications have been reported elsewhere (6,8,14). To date, only VEEV subtype ID has been isolated in and around Puerto Maldonado (5); thus, this patient was probably also infected with this subtype. However, we cannot unequivocally state that the patient died from VEEV infection.

Both fatal cases described in this report were clinically similar to previously reported enzootic and epidemic VEE cases (1,6,8,9,11,14). Initially, both patients had fever, body aches, vomiting, and diarrhea (Table 1) (1, 6,8,9,11), which are also caused by other tropical diseases like dengue. Only some patients, such as patient 1 from Yurimaguas, had neurologic complications (Table 1), which are more commonly observed in children<15 years of age (6,8,9,11).

Our surveillance activities were limited to only 8 surveillance sites in Peru (Figure 1), so VEE cases in other areas may remain undiagnosed. Because of the lack of surveillance activities and proper diagnostic capabilities, fatal VEEV infection in Peru is likely; many cases may remain underreported in isolated rural locations where the disease is most common. Additional studies are needed to fully measure the extent and effects of VEE in Peru.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carolina Guevara, Zonia Rios, Roxana Caceda, Vidal Felices, Cristhopher Cruz, Connie Fernandez, Aydee Cruz, and Javier Ignacio Effio for invaluable support in the execution of the study. We also thank the personnel of the Hospital de Apoyo Yurimaguas for supporting our febrile illness surveillance study.

This study was funded by the US Department of Defense Global Emerging Infections Systems Research Program, Work Unit no. 847705.82000.25GB.B0016. The study protocol for Surveillance and Etiology of Acute Febrile Illnesses in Peru was approved by the Naval Medical Research Center Institutional Review Board (protocol NMRCD.2000.0006) in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects.

Biography

Dr Vilcarromero is a physician who participates in the Surveillance and Etiology of Febrile Acute Diseases in Peru project, conducted by the NMRCD, Peruvian Ministry of Health, and Cayetano Heredia and San Marcos Universities in Lima. He is responsible for the project in an extensive area in the jungle of Peru, and his work is now based in the city of Iquitos.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Vilcarromero S, Aguilar PV, Halsey ES, Laguna-Torres VA, Razuri H, Perez J, et al. Venezuelan equine encephalitis and 2 human deaths, Peru. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2010 Mar [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1603.090970

References

- 1.Aguilar PV, Greene IP, Coffey LL, Medina G, Moncayo AC, Anishchenko M, et al. Endemic Venezuelan equine encephalitis in northern Peru. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:880–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watts DM, Callahan J, Rossi C, Oberste MS, Roehrig JT, Wooster MT, et al. Venezuelan equine encephalitis febrile cases among humans in the Peruvian Amazon River region. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watts DM, Lavera V, Callahan J, Rossi C, Oberste MS, Roehrig JT, et al. Venezuelan equine encephalitis and Oropouche virus infections among Peruvian army troops in the Amazon region of Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:661–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison AC, Forshey BM, Notyce D, Astete H, Lopez V, Rocha C, et al. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus in Iquitos, Peru: urban transmission of a sylvatic strain. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e349. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguilar PV, Adams AP, Suarez V, Beingolea L, Vargas J, Manock S, et al. Genetic characterization of Venezuelan encephalitis virus from Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru: identification of a new subtype ID lineage. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e514. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quiroz E, Aguilar PV, Cisneros J, Tesh RB, Weaver SC. Venezuelan equine encephalitis in Panama: fatal endemic disease and genetic diversity of etiologic viral strains. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e472. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberste MS, Weaver SC, Watts DM, Smith JF. Identification and genetic analysis of Panama-genotype Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus subtype ID in Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:41–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson KM, Shelokov A, Peralta PH, Dammin GJ, Young NA. Recovery of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus in Panama. A fatal case in man. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1968;17:432–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivas F, Diaz LA, Cardenas VM, Daza E, Bruzon L, Alcala A, et al. Epidemic Venezuelan equine encephalitis in La Guajira, Colombia, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:828–32. 10.1086/513978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weaver SC, Salas R, Rico-Hesse R, Ludwig GV, Oberste MS, Boshell J, et al. Re-emergence of epidemic Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis in South America. VEE Study Group. Lancet. 1996;348:436–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)02275-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowen GS, Fashinell TR, Dean PB, Gregg MB. Clinical aspects of human Venezuelan equine encephalitis in Texas. Bull Pan Am Health Organ. 1976;10:46–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venezuelan equine encephalitis–Colombia, 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:721–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weaver SC, Ferro C, Barrera R, Boshell J, Navarro JC. Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Annu Rev Entomol. 2004;49:141–74. 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vilcarromero S, Laguna-Torres VA, Fernandez C, Gotuzzo E, Suarez L, Cespedes M, et al. Venezuelan equine encephalitis and upper gastrointestinal bleeding in child. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:323–5. 10.3201/eid1502.081018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moncayo AC, Medina GM, Kalvatchev Z, Brault AC, Barrera R, Boshell J, et al. Genetic diversity and relationships among Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus field isolates from Colombia and Venezuela. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:738–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]