Abstract

Paenibacillus larvae causes American foulbrood in honey bees. We describe P. larvae bacteremia in 5 injection drug users who had self-injected honey-prepared methadone proven to contain P. larvae spores. That such preparations may be contaminated with spores of this organism is not well known among pharmacists, physicians, and addicts.

Keywords: Paenibacillus larvae, bacteremia, bacteria, intravenous drug abuse, honey, methadone substitution, American foulbrood, dispatch

As a consequence of needle sharing and repeated parenteral administration of nonsterile material, injection drug users risk becoming ill from a variety of infections, including HIV, hepatitis C, endocarditis, and skin and soft tissue infections (1). Febrile episodes in injection drug users are common, yet distinguishing between febrile reactions caused by toxins or impurities in the injected substance and true infections may be difficult (2,3). Methadone hydrochloride, which is widely used for opioid substitution, can be mixed with viscous substances such as syrup to yield a solution that is not suitable for misuse through self-injection. Methadone syrup is intended to be taken only as an oral medication. Some pharmacies use honey instead of syrup to prepare such a solution.

Paenibacillus larvae is a spore-forming gram-positive microorganism known for its ability to cause American foulbrood, a severe and notifiable disease of honey bees (Apis mellifera) (4) (Figure). P. larvae is endemic to bee colonies worldwide. The organism can be cultured from <10% of honey samples from Germany but from >90% of samples from honeys imported from other countries (5). P. larvae spores are highly resilient and can survive in honey for years (6,7). We describe P. larvae bacteremia in 5 patients who had a history of intravenous drug abuse and were in a program of opioid substitution that used methadone.

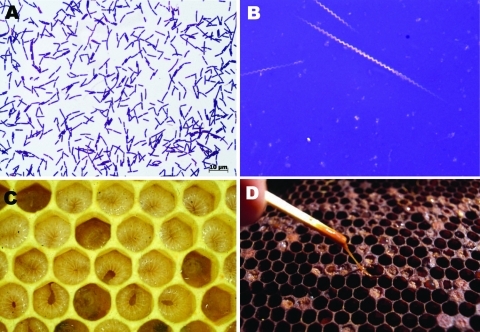

Figure.

Paenibacillus larvae gram-positive, spore-forming, rod-shaped bacteria (A) (Gram stain, original magnification ×1,000) with the ability to form giant whips upon sporulation (B) (nigrosine stain, original magnification ×1,000). In American foulbrood (AFB), newly hatched honey bee larvae become infected through ingestion of brood honey containing P. larvae spores. After germination and multiplication, infected bee larvae die within a few days and are decomposed to a ropy mass, which releases millions of infective spores after desiccation. C) AFB-diseased larvae are beige or brown in color and have diminished segmentation (healthy and AFB-diseased larvae). D) Clinical diagnosis of AFB can be made by a matchstick test, demonstrating the viscous, glue-like larval remains adhering to the cell wall.

The Study

All patients sought treatment for fever ranging from 37.8°C to 39.8°C and admitted to continuing to inject illicit drugs or methadone. Information about patient characteristics, clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory and micobiologic investigations, and treatment details are summarized in the Table. P. larvae was identified in blood cultures (BacT/ALERT 3D-System; bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) of each patient described. The clinical course of P. larvae bacteremia was benign in 3 patients, and complications developed in 2 patients. Patient 1 had relapsing disease and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; patient 4 had pulmonary embolism without definite evidence of septic embolism. Patients 2 and 3 recovered without specific antimicrobial drug treatment; for patients 4 and 5, defervescence and negative follow-up blood cultures were observed after they received treatment with β-lactam agents (imipenem or cefuroxime). The recurrent P. larvae infection observed in patient 1 was probably the consequence of repeated injection of contaminated methadone rather than an inadequate response to antimicrobial drug therapy.

Table. Patient characteristics, clinical presentation, treatment, and laboratory and microbiologic results of 5 patients with Paenibacillus larvae bacteremia*.

| Characteristic | Patient no. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Age, y/sex | 28/F | 32/M | 20/M | 35/M | 27/F |

| Date evaluated | 2003 Jul | 2003 Sep | 2003 Oct | 2004 Feb | 2008 May |

| Clinical samples with identification of P. larvae† | Culture of ascites (2003 Jul), blood culture (2003 Aug) | Blood culture | Blood culture | Blood culture | Blood culture |

| CRP, mg/L | 43 | 17 | 11 | 37 | 40 |

| Leukocyte count, × 109/L | 23.0 | 13.0 | 9.3 | 11.8 | 19.2 |

| Medical history | IVDA, hepatitis C, Child B liver cirrhosis with refractory ascites | IVDA, hepatitis C, hepatitis B | IVDA, hepatitis C | IVDA, hepatitis C, history of hepatitis A | IVDA, hepatitis C, alcohol abuse |

| Clinical signs and symptoms | Decompensated liver cirrhosis, ascites, fever (39.2°C) | Persistent weakness and malaise, fever (39.2°C) | Somnolence, fever (38.2°C) | Tachypnoe, right-sided pleuritic chest pain, fever (37.8°C) | Severe anemia, spontaneous mucosal bleeding, fever (39.8°C) |

| Clinical conditions other than bacteremia | Bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS placement | Acute hepatitis B diagnosed 1 mo before bacteremia, eosinophilia | Methadone/ diazepam overdose | Pulmonary embolism, infarction pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis | Subsequently diagnosed with ITP, Paracoccus yeei and Micrococcus luteus bacteremia |

| Treatment (duration) | Meropenem (7 d) followed by ampicillin IV (2 d), then meropenem (7 d) followed by penicillin G (14 d) | None | None | Cefuroxim IV (7 d) | Imipenem (21 d) |

*CRP, C-reactive protein (reference range <5 mg/L); IVDA, intravenous drug abuse; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; ITP, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; IV, intravenous. †P. larvae identified after culture using 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

In 2 cases, culture of the honey used to prepare methadone or of honey-containing ready-to-use methadone also yielded P. larvae. Honey and methadone samples were diluted in sterile phosphate-buffered saline and cultured with or without heat pretreatment (90°C, 10 min) under aerobic and anaerobic conditions at 37°C for 3–4 days by using Columbia blood agar and MYPGD (Mueller-Hinton broth, yeast extract, potassium phosphate, glucose, pyruvate) agar. Colonies from positive blood or honey or methadone cultures with an appropriate macroscopic appearance and gram-stain morphology as well as negative catalase reaction were further identified by PCR amplification and 16S rRNA gene sequencing according to published protocols (8). Obtained sequences were analyzed by using the BLAST algorithm (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Conclusions

We detected P. larvae in sterile compartments of 5 patients with clinical and laboratory evidence of infection. Given the fact that all patients were injection drug users, the mode of infection was thought to be intravenous administration of contaminated methadone, resulting in P. larvae bacteremia. Our hypothesis is supported by the isolation of P. larvae from honey or honey-containing methadone provided to 2 patients.

Recently, several Paenibacillus species have been reported to cause bacteremic infections in humans. Among these are P. thiaminolyticus (bacteremia in a patient undergoing hemodialysis) (9), P. konsidensis (bacteremia in a febrile patient with hematemesis) (10), P. alvei (prosthetic joint infection with bacteremia) (11), and P. polymyxa (bacteremia in a patient with cerebral infarction) (12). Furthermore, the novel species P. massiliensis, P. sanguinis, and P. timonensis were isolated from blood cultures of patients with carcinoma, interstitial nephropathy, and leukemia, respectively (13). Pseudobacteremia of P. hongkongensis and P. macerans has been reported (14,15).

Several aspects provide strong evidence for a genuine P. larvae bacteremia in the cases described here. First, the present cases were observed over a period of several years, and detection of P. larvae thus occurred in different charges of blood culture bottles, which argues against pseudobacteremia. Second, isolation of P. larvae was reported independently by 2 microbiology laboratories, making contamination highly unlikely. Third, in patient 1 isolation succeeded at different times and in samples of different compartments. Moreover, the detection of P. larvae in honey-prepared methadone and honey strongly suggests genuine bacteremia as a consequence of injection of contaminated material.

Biochemical and molecular identification of P. larvae may be difficult and time-consuming. Misinterpretation of blood culture results because of incomplete differentiation or confusion with other gram-positive spore forming-bacteria (e.g., Bacillus species) has to be taken into consideration. Underestimation of the frequency of true P. larvae bacteremia therefore cannot be excluded. Thus, infectious disease physicians, microbiologists, and pharmacists need to be aware that injection of material contaminated with P. larvae, such as honey-prepared methadone, may cause bacteremic infection.

Biography

Dr Rieg is an infectious diseases fellow at the University Medical Center in Freiburg, Germany. His research interests focus on innate defense antimicrobial peptides and Staphylococcus aureus infections.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Rieg S, Bauer TM, Peyerl-Hoffmann G, Held J, Ritter W, Wagner D, et al. Paenibacillus larvae bacteremia in injection drug users. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2010 March [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1603.091457

References

- 1.Irish C, Maxwell R, Dancox M, Brown P, Trotter C, Verne J, et al. Skin and soft tissue infections and vascular disease among drug users, England. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1510–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopper JA, Shafi T. Management of the hospitalized injection drug user. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002;16:571–87. 10.1016/S0891-5520(02)00009-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine DP, Brown PD. Infections in injection drug users. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 6th ed. New York: Elsevier 2005. p. 3462–76. [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Graaf DC, Alippi AM, Brown M, Evans JD, Feldlaufer M, Gregorc A, et al. Diagnosis of American foulbrood in honey bees: a synthesis and proposed analytical protocols. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2006;43:583–90. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.02057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritter W. Early detection of American foulbrood by honey and wax analysis. Apiacta. 2003;38:125–30. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Von der Ohe W, Dustmann JH. Efficient prophylactic measures against American foulbrood by bacterial analysis of honey for spore contamination. Am Bee J. 1997;8:603–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasemann L. How long can spores of American foulbrood live? Am Bee J. 1961;101:298–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sander A, Ruess M, Bereswill S, Schuppler M, Steinbrueckner B. Comparison of different DNA fingerprinting techniques for molecular typing of Bartonella henselae isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2973–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ouyang J, Pei Z, Lutwick L, Dalal S, Yang L, Cassai N, et al. Case report: Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus: a new cause of human infection, inducing bacteremia in a patient on hemodialysis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2008;38:393–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko KS, Kim YS, Lee MY, Shin SY, Jung DS, Peck KR, et al. Paenibacillus konsidensis sp. nov., isolated from a patient. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58:2164–8. 10.1099/ijs.0.65534-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reboli AC, Bryan CS, Farrar WE. Bacteremia and infection of a hip prosthesis caused by Bacillus alvei. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1395–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasu Y, Nosaka Y, Otsuka Y, Tsuruga T, Nakajima M, Watanabe Y, et al. A case of Paenibacillus polymyxa bacteremia in a patient with cerebral infarction. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 2003;77:844–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roux V, Raoult D. Paenibacillus massiliensis sp. nov., Paenibacillus sanguinis sp. nov. and Paenibacillus timonensis sp. nov., isolated from blood cultures. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:1049–54. 10.1099/ijs.0.02954-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noskin GA, Suriano T, Collins S, Sesler S, Peterson LR. Paenibacillus macerans pseudobacteremia resulting from contaminated blood culture bottles in a neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control. 2001;29:126–9. 10.1067/mic.2001.111535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teng JL, Woo PC, Leung KW, Lau SK, Wong MK, Yuen KY. Pseudobacteraemia in a patient with neutropenic fever caused by a novel paenibacillus species: Paenibacillus hongkongensis sp. nov. Mol Pathol. 2003;56:29–35. 10.1136/mp.56.1.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]